Abstract

UiO-67(Zr), as a member of Zr-based metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), has attracted much attention owing to its merits, involving large surface area, high pore volume, and good structural stability. However, it is generally inactive in many catalytic reactions due to a lack of active sites. In this work, we report a new strategy, combining vapor-assisted synthesis with acid treatment to create abundant active sites in UiO-67(Zr), resulting from defects. The effects of some synthetic parameters were systematically investigated. As a result, an optimized material named UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H, obtained by acid-treating UiO-67(Zr) and prepared with the addition of 0.5 mL formic acid via a vapor-assisted method, exhibited outstanding catalytic performance in the oxidation of dibenzothiophene (DBT), which can completely oxidize DBT in 9 min at 30 °C using H2O2 as the oxidant. The calculated turnover frequency reached 150.4 h−1, surpassing those of most reported Zr-MOFs catalysts. In addition, it is demonstrated that UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H is a heterogeneous catalyst and can be reused without obvious activity loss.

1. Introduction

Desulfurization of fuel oil is one of the most important research subjects for the production of clean energy [1,2,3]. Various desulfurization technologies have been developed to meet increasingly stringent sulfur content standards. Hydrodesulfurization (HDS) is the most commonly used desulfurization method in industry. However, it is difficult to remove the refractory aromatic sulfur compounds like dimethyldibenzothiophene (DMDBT) in fuel oil using the HDS method due to the steric hindrance effect from alkyl groups on the aromatic rings. Oxidative desulfurization (ODS) has emerged as a promising strategy for eliminating those sulfur compounds under mild conditions without hydrogen consumption [4,5,6]. Therefore, developing highly efficient ODS catalysts has been of great interest [7,8,9,10,11].

Recently, zirconium-based metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have received much attention owing to their good structural stability, high specific surface area, and rich metal centers [12,13,14,15,16]. For this, Zr-MOFs like UiO-66(Zr) have been explored as heterogeneous catalysts for the catalytic ODS of fuel oil [17,18,19]. The studies indicated that the defects in Zr-MOFs could serve as catalytically active sites in ODS reactions. Thus, how to create more defects in Zr-MOFs has been a hot research topic. As a member of Zr-MOFs, UiO-67(Zr), with a high specific surface area and large pore size, built from Zr6O4(OH)4 clusters and biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate linkers, has been widely investigated [20,21,22]. Some work has been done to manufacture defects in the structure of UiO-67(Zr). For example, Liu et al. reported that the addition of benzoic acid during the synthesis of UiO-67(Zr), and the resulting defective UiO-67(Zr) was used to adsorb dimethyl phthalate and phthalic acid [23]. Dong et al. used acetic acid to modify defects in UiO-67(Zr) for the efficient removal of tetracycline hydrochloride from aqueous solutions [24]. Zhao et al. used acetic acid to prepare defective UiO-67(Zr) for carbonic anhydrase immobilization to improve the ability of CO2 capture and conversion [25]. Although the defects resulting from partial ligand losses were produced by the above-mentioned modes, the added monodentate acids would remain in the structure of UiO-67(Zr) by coordination with Zr sites. Obviously, those Zr sites combined with monodenate acids are not beneficial in forming active intermediates in catalytic reactions.

In this work, UiO-67(Zr) materials were prepared in the absence and presence of formic acid first using the vapor-assisted method. Then, hydrochloric acid was used to treat them to create defects in UiO-67(Zr). In the meantime, the effect of some synthesis parameters was investigated. In addition, the catalytic performance of the obtained materials was evaluated, mainly by the oxidation reaction of DBT. A systematic study on the optimized catalyst was carried out. Based on the experimental results, a plausible reaction mechanism was proposed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Characterization and Properties of UiO-67(Zr) Materials

In the beginning, some parameters related to the vapor-assisted synthesis of UiO-67(Zr) were examined. Based on the results from XRD and nitrogen adsorption, the optimized conditions were determined to be a crystallization temperature of 130 °C and a crystallization time of 12 h, because UiO-67(Zr) prepared under such conditions exhibited good crystal structure and high specific surface area (See Figures S1–S4 and Table 1). For clear comparison with UiO-67(Zr)-S, the optimized sample was named UiO-67(Zr)-V.

Table 1.

The nitrogen sorption data of various samples.

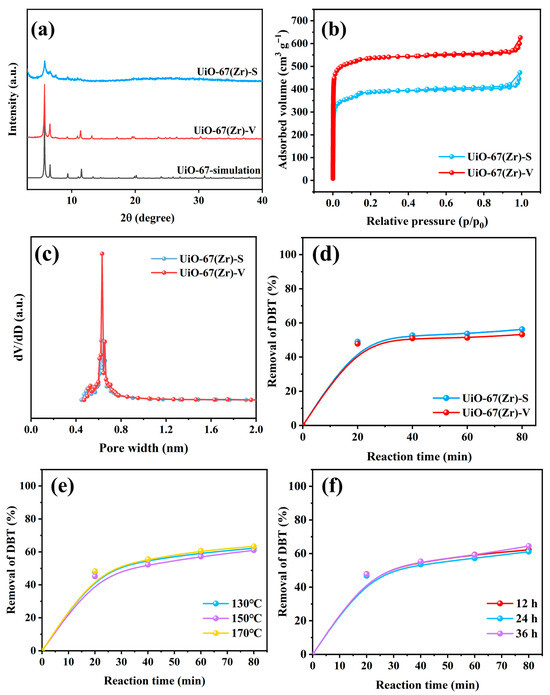

As shown in Figure 1a, UiO-67(Zr)-V and UiO-67(Zr)-S exhibited the well-resolved diffraction peaks of 2θ = 5.7°, 6.6°, and 11.5°corresponding to (111), (200), and (220) crystal planes of the UiO-67(Zr) crystal structure, respectively, which indicated the successful synthesis of UiO-67(Zr) [20,26]. Seemingly, UiO-67(Zr)-V possessed higher crystallinity than UiO-67(Zr)-S, suggesting the vapor-assisted method is beneficial for the crystallization of UiO-67(Zr). The sorption data (Figure 1b) showed that UiO-67(Zr)-V (2109 m2 g−1) had a higher BET specific surface area than UiO-67(Zr)-S (1705 m2 g−1), which is in agreement with the XRD results. The pore size distribution curves of both samples showed a dominant pore diameter of ~0.7 nm (Figure 1c). Moreover, it can be seen from the SEM results that both samples had different morphologies (Figure S5a,b). UiO-67(Zr)-S consisted of irregular and aggregated particles. Comparatively, UiO-67(Zr)-V exhibited uniform and well-dispersed octahedra morphology [27]. Further, both samples were almost inactive in the ODS reaction of DBT (Figure 1d). These results revealed that the active sites in both samples were limited, which might be related to the formation of fewer defect sites in the structure of UiO-67(Zr) [22,28]. Moreover, the influence of crystallization temperature and time on the catalytic ODS performance of UiO-67(Zr)-V was investigated. As shown in Figure 1e,f, these samples exhibited similar catalytic performance. To save the synthesis time and energy, the synthetic conditions of 130 °C and 12 h were chosen for the following studies.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD patterns, (b) N2 sorption isotherms, (c) pore size distribution and (d) catalytic ODS performance of UiO-67(Zr)-S and UiO-67(Zr)-V, the effect of (e) crystallization temperature and (f) crystallization time on catalytic ODS performance of UiO-67(Zr)-V (Reacion conditions: 40 mg catalyst, 10 mL model fuel, 500 ppm DBT, 5 mL acetonitrile, H2O2 as oxidant, O/S molar ratio of 6, and a reaction temperature of 30 °C).

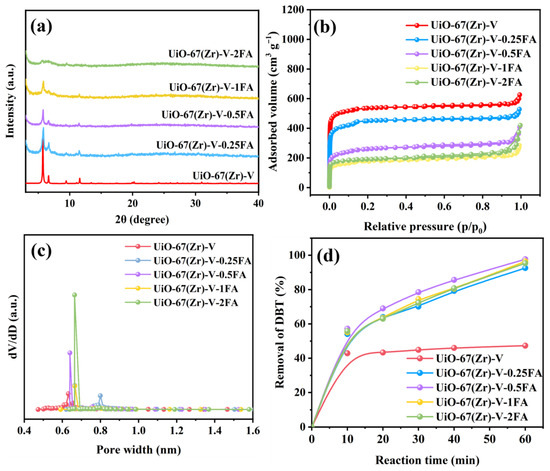

In earlier reports, it is shown that the addition of a ligand modulator is an efficient route to make defects in MOFs [19,29,30]. Thus, in this work, formic acid was added to the synthesis of UiO-67(Zr) for the formation of defects. Meanwhile, the effect of the HCOOH addition amount was studied. As shown in Figure 2a, a low addition amount of HCOOH, from 0.25 to 1 mL, would not influence the formation of UiO-67(Zr). However, if the addition amount increased to 2 mL, the crystallization of UiO-67(Zr) would be greatly inhibited. The results from N2 sorption isotherms (Figure 2b) revealed that the surface areas decreased with increasing formic acid concentration, which might be attributed to the restricted framework assembly resulting from the competitive coordination between HCOOH and H2BPDC. Figure 2c shows their pore size distribution curves. As seen, the average pore diameter was slightly influenced by the addition of HCOOH. Furthermore, the catalytic results (Figure 2d) indicated that UiO-67(Zr)-V-xFA samples exhibited enhanced catalytic ODS performance, suggesting that the addition of HCOOH during vapor-assisted synthesis possibly formed some active sites in the structure of UiO-67(Zr).

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns, (b) N2 sorption isotherms, (c) pore size distribution, and (d) catalytic performance of UiO-67(Zr)-V-xFA samples prepared by different amounts of HCOOH (Reaction conditions: 40 mg catalyst, 10 mL model fuel, 500 ppm DBT, 5 mL acetonitrile, H2O2 as oxidant, O/S molar ratio of 6, and a reaction temperature of 30 °C).

2.2. Catalytic Performance of UiO-67(Zr) Materials After the Treatment of HCl

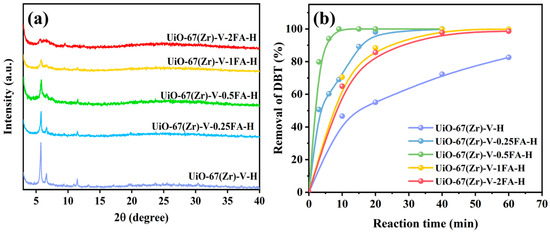

Considering that the Zr sites coordinated with formic acid could be inactive, HCl treatment was carried out to create more active Zr sites by removing the formate anions in the structure of UiO-67(Zr). As shown in Figure 3a, these materials, after HCl treatment, could still maintain the original structure. However, the intensity of their XRD patterns turned weak, indicating that the structure was locally destroyed to some extent. Apparently, their catalytic ODS performance was greatly enhanced after HCl treatments (Figure 3b). Among them, UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H showed the best catalytic activity, completing the conversion of DBT in 9 min. Such catalytic performance is outstanding compared with some reported Zr-MOFs (Table 2).

Figure 3.

(a) XRD patterns and (b) catalytic performance of various catalysts (Reaction conditions: 40 mg catalyst, 10 mL model fuel, 500 ppm DBT, 5 mL acetonitrile, H2O2 as oxidant, O/S molar ratio of 6, and a reaction temperature of 30 °C).

Table 2.

Comparison of catalytic performance with some Zr-MOFs in the ODS reaction of DBT.

2.3. Further Evaluation on the Catalytic Performance of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H

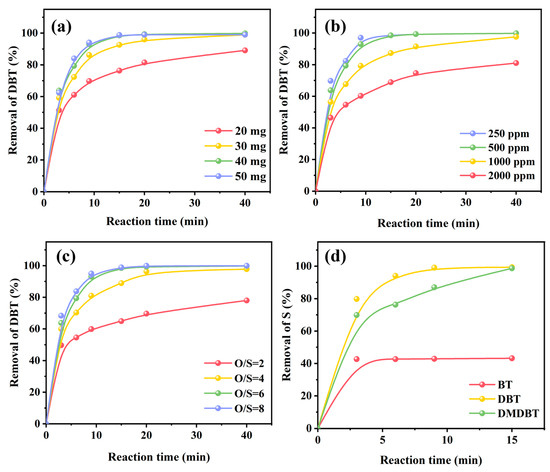

Based on the fact that UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H gave the best catalytic ODS activity among these studied catalysts, the effects of reaction conditions, including catalyst dosage, substrate concentration, O/S molar ratio, and reaction temperature, on its catalytic performance were examined. As shown in Figure 4a, as the amount of catalyst increased from 20 mg to 40 mg, the removal rate of DBT improved. When the catalyst amount was 50 mg, no obvious improvement in catalytic activity was observed, indicating that the number of active sites might be excessive for the removal of DBT under the reaction conditions. Figure 4b shows the effect of sulfur concentration. The conversion rate decreased with the increase in sulfur concentration. However, even if the DBT concentration was 1000 ppm, the removal rate of DBT could still reach above 96% in 40 min. The effect of O/S molar ratio is shown in Figure 4c. As seen, increasing the O/S molar ratio from 2 to 6 improved the removal rate of DBT from 72% to 100% in 40 min. However, further increasing the O/S molar ratio to 8 did not accelerate the removal of DBT, which is possibly related to the decomposition of excess hydrogen peroxide during the reaction. Figure 4d displays the effect of sulfur substrate. Strangely, UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H was inactive for the oxidation of BT. At present, the reason is unclear. Comparatively, DMDBT can be completely oxidized in 15 min. According to the electrophilic addition mechanism, high electron density around the sulfur atom may accelerate the oxidation process. It is known that the electron cloud density around S centers in these sulfur compounds is in the order of BT < DBT < DMDBT [34,35,36,37]. Although DMDBT had the highest electron cloud density, the methyl groups at positions 4 and 6 introduced steric hindrance that partly counterbalanced this advantage, resulting in a similar or slightly lower removal rate than DBT.

Figure 4.

Effect of reaction conditions on the catalytic ODS performance of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H at 30 °C: (a) catalyst dosage, (b) initial sulfur content, (c) O/S molar ratio, and (d) sulfur substrate.

Moreover, a series of control experiments was carried out to clarify the catalytic effect in the oxidation of DBT. As shown in Figure S6, if no oxidant or catalyst was added to the catalytic system, only about a 40% extraction rate was observed without the conversion of DBT. If acetonitrile was not used, UiO-67(Zr)-V-xFA-H gave a very low catalytic activity, perhaps because it is difficult for a catalyst with surface oleophobicity to come into contact with DBT in the oil phase. The addition of acetonitrile may extract DBT from the oil phase into the CH3CN phase. Then, the catalyst can have a good interaction with DBT in the CH3CN phase. Notably, the initial extraction rate had no significant influence on the overall sulfur removal because it has been demonstrated that DBT in both CH3CN and oil phases was completely converted into DBTO2.

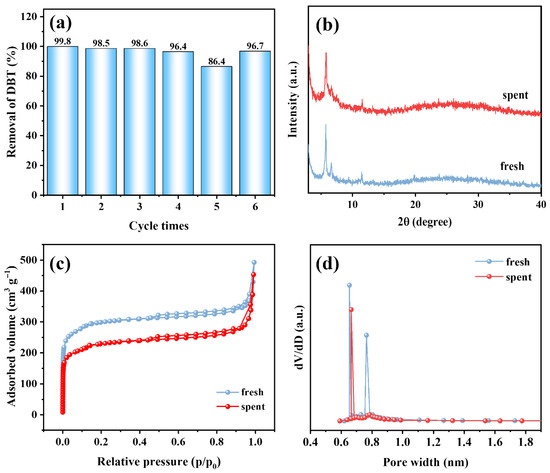

The reusability of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H was shown in Figure 5a. As seen, the removal rate of DBT decreases with increasing cycle times. However, it can still reach a removal rate of 86.4% after five cycles. The decrease in DBT removal content might be mainly attributed to the loss of active sites resulting from the adsorbed sulfones on the catalyst’s surface. To testify to this point, the spent catalyst was washed with acetonitrile after five cycles and dried. The catalytic performance of regenerated UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H was evaluated again. Notably, a 96.7% removal rate of DBT was obtained at the sixth cycle, indicating that the washing step is efficient for recovering the catalytic performance. The XRD results revealed that the spent catalyst still maintained the crystal structure of UiO-67(Zr) (Figure 5b). Furthermore, the spent catalyst exhibited similar type I sorption isotherms and pore size distribution to the fresh one (Figure 5c,d). A slight decrease in specific surface area might be attributed to partial pore blocking from adsorbed impurities. These results demonstrated that UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H possessed good structural stability and could be reused.

Figure 5.

(a) Reusability of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H, (b) XRD patterns, (c) N2 sorption isotherms, (d) pore size distribution curves of fresh and spent UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H.

2.4. Relationship Between Catalytic Performance and Structure

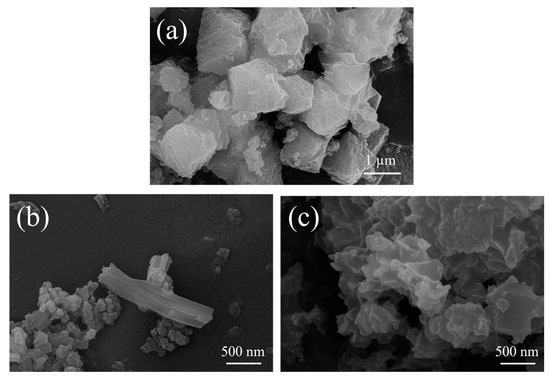

To ascertain the reason why the catalytic performance was enhanced, three representative samples (UiO-67(Zr)-V, UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA, and UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H) were selected for further comparison. As mentioned above, all three samples possessed the crystal structure of UiO-67(Zr). Differently, the order of surface area is UiO-67(Zr)-V > UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H > UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA. However, the order of catalytic efficiency is UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H > UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA > UiO-67(Zr)-V. Obviously, the catalytic performance had no clear relationship with their surface area. The SEM image of UiO-67(Zr)-V showed an octahedral morphology (Figure 6a). With the addition of formic acid, a rod-like shape with a smooth surface was observed (Figure 6b). After acid treatment, UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H exhibited a flower-like agglomeration state (Figure 6c). Such a change might be due to the dissolution–reprecipitation process in the acid treatment process. In the process, the original crystal structure was destroyed and entered the solution in the form of ions or small molecular fragments [38]. These results suggested that it was feasible to detach the formate anions from the structure of UiO-67(Zr) using an acid treatment strategy.

Figure 6.

SEM images of (a) UiO-67(Zr)-V, (b) UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA and (c) UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H.

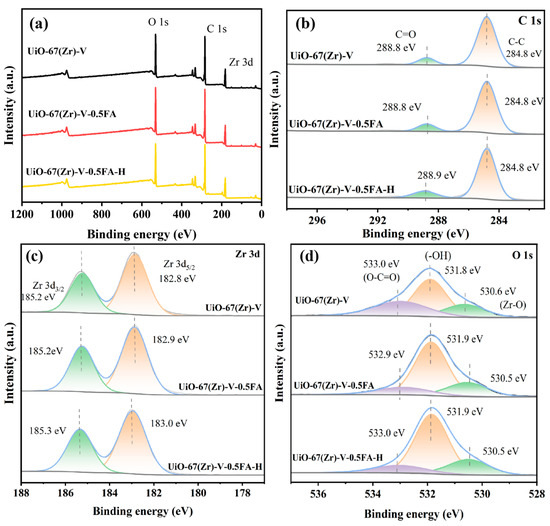

Figure 7 shows the XPS results of the three samples. The survey spectrum presented the regional peaks corresponding to Zr 3d, C 1s, and O 1s for all samples (Figure 7a). The C 1s spectrum showed two peaks corresponding to C–C and O–C=O (Figure 7b) [39]. As shown in Figure 7c, the Zr 3d spectrum exhibited two characteristic peaks assigned to Zr 3d5/2 (182.8 eV) and Zr 3d3/2 (185.2 eV) [39,40], which are indicative of Zr4+ coordinated via Zr–O bonds. For UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA, an upshift in Zr 3d5/2 binding energy was observed (182.9 eV), which could be attributed to partial replacement of BPDC ligands by formate anions. After acid treatment, the binding energy of Zr 3d3/2 further increased, indicating that the coordination number of Zr decreased and the electron cloud density dropped. This also demonstrates the formation of defects. As displayed in Figure 7d, the O 1s XPS spectra of the three samples can be deconvoluted into three characteristic peaks, assigned to O–C=O (533.0 eV), –OH (531.8 eV), and Zr–O (530.6 eV) bonds, respectively [41,42]. Based on the relative contents of different oxygen-containing species derived from the XPS O 1s spectrum (Table S2), some changes were observed after acid treatment. Specifically, the proportion of Zr–OH species increased from 60.3% in UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA to 66.4% in UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H. Correspondingly, the relative content of Zr–O species (originating from Zr–O–C bonds formed by the coordination of Zr atoms with formate ions or BPDC ligands) decreased from 24.9% (UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA) to 20.7% (UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H). These results suggest that the acid treatment caused the removal of formate ions, which in turn resulted in the exposure of more coordinatively unsaturated Zr sites.

Figure 7.

XPS spectra of various samples (a) survey; (b) C 1s, (c) Zr 3d, and (d) O 1s.

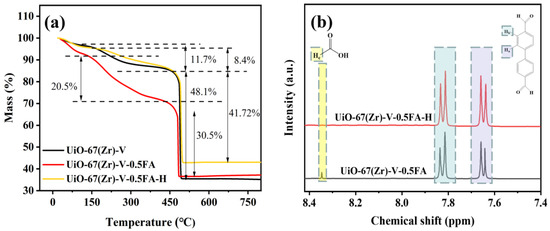

TGA curves of the three samples are shown in Figure 8a. The mass loss process included three stages, which is consistent with the results reported in the literature [43,44]. As seen, they displayed similar mass-loss profiles below 150 °C, which can be attributed to the desorption of residual solvent from the pores. The second loss between 150 and 450 °C originated from the removal of weakly coordinated formate anions. It needs to be noted that the existence of formate anions in UiO-67(Zr)-V could come from the decomposition of DMF during the synthesis. Obviously, the amount of their second mass loss was different. UiO-67(Zr)-V gave a mass loss of 11.7%. With the addition of formic acid, UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA showed a 22.5% mass loss, indicating that more formate anions should be introduced into the structure of UiO-67(Zr). After HCl treatment, the mass loss was reduced to 8.4%, revealing that these formate anions may be efficiently detached by acid treatment. This means that more defects in the structure of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H should be created.

Figure 8.

(a) TGA curves and (b) 1H NMR spectra of various samples.

Liquid-phase 1H NMR analysis was used to demonstrate this point. As seen in Figure 8b, UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA and UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H displayed the characteristic signals of biphenyl dicarboxylic acid in the range of δ 7.85–7.83 and δ 7.68–7.64, corresponding to aromatic protons on the benzene ring [23,30]. Differently, UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA displayed an obvious characteristic peak at δ = 8.35 assigned to formic acid protons [19]. After acid treatment, this peak was almost invisible. These results further demonstrate that formate anions can be removed by HCl treatment, and more defects in the structure of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H should be formed. This may be the main reason why the catalytic performance of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA can be greatly enhanced after HCl treatment. The number of missing ligands in three materials was calculated based on the TGA data (Table S3). The results show that the ligand defects in UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA and UiO-67(Zr)-V are 3.81 and 2.28, respectively, indicating that formate ions have successfully replaced partial BPDC ligands. However, such calculated defects included the case of formate coordination. When combined, the values of 2.32 for UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA and 2.82 for UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H, respectively, showed a close relationship with catalytic performance.

2.5. Proposed Reaction Mechanism

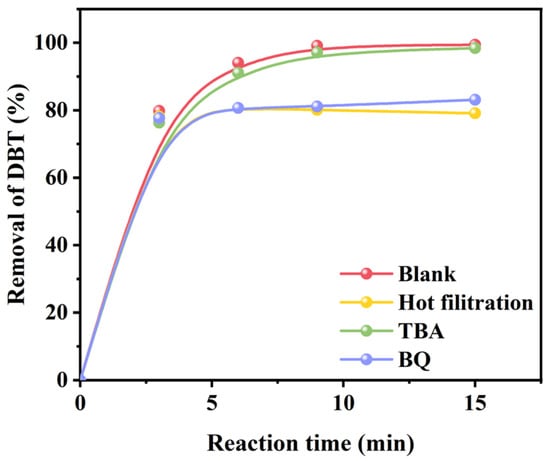

A hot filtration test over UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H was performed to demonstrate its heterogeneous nature. As shown in Figure 9, the removal of DBT ceased when the catalyst was separated from the reaction system after a reaction time of 3 min, revealing that UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H is really a heterogeneous catalyst. To study the reaction mechanism, TBA and BQ were employed as scavengers for OH and ·O2− radicals, respectively [45,46]. As seen, the addition of TBA had no obvious effect on the removal rate of DBT. However, the removal of DBT would be greatly inhibited if BQ were added. These results suggested that superoxide anion (·O2−) should be the predominant reactive species in the ODS reaction of DBT.

Figure 9.

Leaching and quenching experiments over UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H in the ODS.

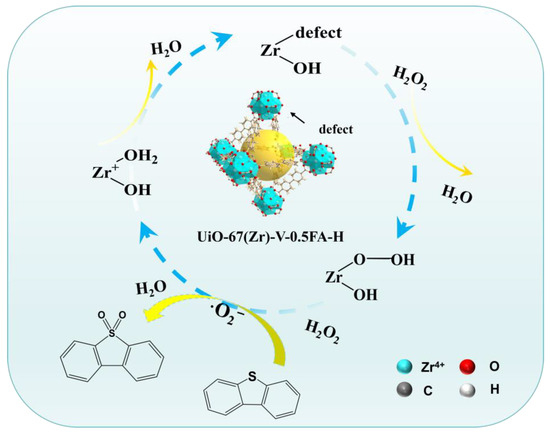

Based on the quenching experiments, a possible reaction pathway over UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H was proposed in the ODS reaction of DBT (Figure 10). In this catalytic cycle, DBT was first extracted from model oil into the CH3CN phase and adsorbed on the catalyst’s surface by the open Zr sites in the structure of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H. Next, the active Zr centers interacted with H2O2 to promote the formation of Zr-O-O-H via a nucleophilic reaction. Then, the intermediate can further react with H2O2 (as a proton donor) that underwent O–O bond heterolysis to generate·O2− radicals. Finally, the·O2− radicals oxidized DBT into DBTO2. Meanwhile, the active Zr centers were recovered for the next catalytic cycle.

Figure 10.

Proposed reaction mechanism over UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H in the ODS of DBT.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Zirconium oxychloride octahydrate (ZrOCl2∙8H2O), zirconium chloride (ZrCl4), 1,4-biphenyl-dicarboxylic acid (H2BPDC), dibenzothiophene (DBT), benzothiophene (BT), and 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene (DMDBT) were purchased from Beijing InnoChem Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Tertiary butanol (TBA), p-benzoquinone (BQ), ethanol, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30 wt%), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), formic acid (FA), n-octane, and acetonitrile were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were analytically pure and used without further purification.

3.2. Solvothermal Synthesis of UiO-67(Zr)

UiO-67(Zr) was prepared according to a previously reported method [20,47]. A mixture of 0.233 g ZrCl4 (1 mmol) and 0.242 g H2BPDC (1 mmol) was dissolved in 50 mL DMF and sonicated for 25 min. The resulting solution was transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 120 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solid product was collected, washed with DMF and ethanol, and dried at 60 °C for 6 h. Finally, the material was activated at 150 °C under vacuum for 12 h to remove residual solvent and impurities. The final product was named UiO-67(Zr)-S, where “S” denotes solvothermal synthesis.

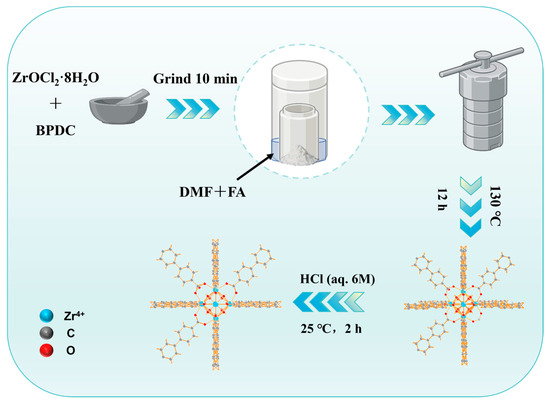

3.3. Vapor-Assisted Synthesis of UiO-67(Zr)

A total of 0.323 g of ZrOCl2·8H2O (1 mmol) and 0.242 g of H2BPDC (1 mmol) were ground in an agate mortar for 10 min. The mixture was transferred to a small Teflon liner (25 mL) placed inside a larger autoclave (100 mL). The outer vessel was charged with (14 − x) mL DMF and x mL formic acid (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0). Then, the autoclave was sealed and heated at 130 °C for 12 h. After cooling, the product was collected by centrifugation, washed alternately with DMF and ethanol, dried at 60 °C for 6 h, and activated under vacuum at 150 °C for 12 h. The final materials were named UiO-67(Zr)-V-xFA, where “V”, “FA”, and ‘x’ represent vapor-assisted synthesis, formic acid, and the volume of formic acid added, respectively. The sample prepared without the addition of formic acid was named UiO-67(Zr)-V.

3.4. Synthesis of Defective UiO-67(Zr)

Briefly, UiO-67(Zr)-S/V-xFA (0.2 g) was dispersed in 30 mL of C2H5OH. Then, 10 mL of 6 M hydrochloric acid was added to the above solution. The resultant solution was stirred in a 25 °C water bath for 2 h. The obtained solid was recovered by centrifugation, washed with ethanol until the pH of the wash solution became neutral. The sample was then dried at 60 °C for 6 h and activated under vacuum at 150 °C for 12 h. The final materials were named UiO-67(Zr)-/V-xFA-H, where “H” denotes HCl treatment. The general preparation process is shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of the preparation process of defective UiO-67(Zr).

3.5. Catalytic ODS Reaction

Prior to each experiment, the catalyst was degassed at 150 °C under vacuum for 2 h Sulfur-containing model compounds (BT, DBT, and DMDBT) were individually dissolved in n-octane to prepare 500 ppm S model fuels. In a typical process, 40 mg of activated catalyst, 10 mL of model fuel, and 5 mL of acetonitrile (extractant) were placed in a 25 mL screw-cap vial. The vial was immersed in a water bath at 30 °C and stirred at 700 rpm for 5 min. The ODS reaction was initiated by adding 30 wt % H2O2. After reaction, the liquid in the n-octane phase was removed and analyzed using an Agilent 7890 A gas chromatograph (GC), equipped with an FID detector and a 30 m packed HP-5 column. The removal content of sulfur compounds was calculated according to the equation R = (1 − Ct/C0) × 100%, where C0 and Ct stand for the initial concentration and the reaction concentration of sulfur compounds in the n-octane phase after t minutes, respectively.

The reusability of UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H was tested through the ODS of DBT at 30 °C. After each cycle, the upper layer (model fuel) was removed with a dropper. Then, 10 mL of fresh model fuel (500 ppm DBT) and 134 μL of H2O2 were added and used in a new catalytic cycle under the same reaction conditions. The catalyst was recovered by centrifugation, washed with acetonitrile, and dried at 60 °C for 2 h for the next cycle.

3.6. Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Billerica, MA, USA) in Bragg–Brentano geometry, equipped with a Ge-focusing primary monochromator (Cu-Kα radiation, λ = 0.15406 nm) at 40 kV and 40 mA. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained using a SUPRA 55 instrument (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with an acceleration voltage of 15 kV. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms were obtained at 77 K on a BSD-PS1 Static Volumetric Specific Surface and Aperture Analyzer (BeiShiDe, Beijing, China). The samples are normally degassed at 423 K under vacuum until a final pressure of 1 × 10−3 Torr is reached prior to measurement and held for 2 h. The specific surface area was calculated via the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) equation. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on a HITACHI TGDTA7300 (Hitachi Limited, Tokyo, Japan) with a heating rate of 10 K/min under O2. Liquid 1H NMR spectra were obtained with a German Bruker Plus 600 MHz Spectrometer. The samples were digested using 1 M NaOH in D2O as a medium. X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS) was used to analyze chemical composition of all the samples on the Thermo Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4. Conclusions

In summary, UiO-67(Zr) materials were synthesized with and without the addition of HCOOH using the vapor-assisted method. The effect of some synthetic parameters on the structure and properties of UiO-67(Zr) was investigated. The optimized crystallization temperature and time are 130 °C and 12 h, respectively. The results from TG and NMR analysis indicate that HCl treatment is an efficient strategy for creating defects in the structure of UiO-67(Zr). The catalytic results revealed that the catalytic ODS performance of UiO-67(Zr) can be greatly enhanced after HCl treatment. An optimized material (UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H) exhibited superior catalytic performance in the ODS reaction of DBT, which can complete the conversion of DBT in 9 min at 30 °C. The calculated turnover frequency reached 150.4 h−1, surpassing those of most reported Zr-MOFs catalysts. The leaching and quenching experiments demonstrated that UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H was a heterogeneous catalyst, and that the ·O2− radicals were the dominant active species. In addition, the recycling test indicated that UiO-67(Zr)-V-0.5FA-H can be reused several times.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16010070/s1, Figure S1: (a) XRD patterns and (b) N2 sorption isotherms of UiO-67(Zr) materials prepared at different crystallization temperatures by vapor-assisted method; Figure S2. SEM images of UiO-67(Zr) materials prepared at different crystallization temperatures by vapor-assisted method: (a) 150 °C, (b) 170 °C; Figure S3. (a) XRD patterns and (b) N2 sorption isotherms of UiO-67(Zr) materials prepared at different crystallization time by vapor-assisted method; Figure S4. SEM images of UiO-67(Zr) materials prepared at different crystallization time by vapor-assisted method: (a) 24 h, (b) 36 h; Figure S5. SEM images of (a) UiO-67(Zr)-S and (b) UiO-67(Zr)-V; Figure S6. Removal rate of DBT under different reaction conditions (40 mg catalyst (UiO-67(Zr)-V-xFA-H), 5 mL acetonitrile, 10 mL model fuel oil, an O/S molar ratio of 6, a reaction temperature of 30 °C); Table S1. The nitrogen sorption data of samples prepared by different addition amount of HCOOH; Table S2. Relative content of different oxygen atoms obtained from O 1s; Table S3. The calculated number of ligand loss per Zr6 formula unit on different samples by TG analysis. References [36,48,49] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Writing—Original Draft, Experiments, Methodology, Investigation, Y.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, Data Curation, X.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, Resources, J.F.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.Z.; Writing—Review and Editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, supervision, Y.S. and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22172042).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural 15 Science Foundation of China (No. 22172042).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, L.; Bai, L.; Wei, D.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Chen, H. MoOx Nanoclusters Decorated on Spinel-Type Transition Metal Oxide Porous Nanosheets for Aerobic Oxidative Desulfurization of Fuels. Fuel 2023, 334, 126753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.-X.; Tan, P.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.-Q.; He, Q.-X.; Sun, L.-B. Functionalization of Metal–Organic Frameworks with Cuprous Sites Using Vapor-Induced Selective Reduction: Efficient Adsorbents for Deep Desulfurization. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3210–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.S.; Fnais, M.; Giannadaki, D.; Pozzer, A. The Contribution of Outdoor Air Pollution Sources to Premature Mortality on a Global Scale. Nature 2015, 525, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chu, L.; Yang, H.; Huang, Z.; Yang, M.; Wang, G. Amphiphilic Halloysite Nanotube Enclosing Molybdenum Oxide as Nanoreactor for Efficient Desulfurization of Model Fuels. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yin, J.; Xun, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; He, M.; Wu, P.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Constructing Interface Chemical Coupling S-Scheme Heterojunction MoO3−x@PPy for Enhancing Photocatalytic Oxidative Desulfurization Performance: Adjusting LSPR Effect via Oxygen Vacancy Engineering. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 355, 124155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.-Q.; Zeng, Y.-N.; Chen, J.; Lin, R.-G.; Zhuang, W.-E.; Cao, R.; Lin, Z.-J. Zr-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks with Intrinsic Peroxidase-Like Activity for Ultradeep Oxidative Desulfurization: Mechanism of H2O2 Decomposition. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 6983–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeStefano, M.R.; Islamoglu, T.; Garibay, S.J.; Hupp, J.T.; Farha, O.K. Room-Temperature Synthesis of UiO-66 and Thermal Modulation of Densities of Defect Sites. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, S.; Jin, Q.; Zhao, J. Review on Oxidative Desulfurization of Fuel by Supported Heteropolyacid Catalysts. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 82, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granadeiro, C.M.; Nogueira, L.S.; Julião, D.; Mirante, F.; Ananias, D.; Balula, S.S.; Cunha-Silva, L. Influence of a Porous MOF Support on the Catalytic Performance of Eu-Polyoxometalate Based Materials: Desulfurization of a Model Diesel. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Lin, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, C. Molybdenum Dioxide Nanoparticles Anchored on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanotubes as Oxidative Desulfurization Catalysts: Role of Electron Transfer in Activity and Reusability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Prins, R. Hydrodesulfurization of 4,6-Dimethyldibenzothiophene over Noble Metals Supported on Mesoporous Zeolites. Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 8606–8609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayder, T.M.; Bensalah, A.T.; Li, B.; Byers, J.A.; Tsung, C.-K. Engineering Second Sphere Interactions in a Host–Guest Multicomponent Catalyst System for the Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Chang, G.; Su, Y.; Xing, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ren, Q.; Bao, Z.; Chen, B. A Metal–Organic Framework with Immobilized Ag(I) for Highly Efficient Desulfurization of Liquid Fuels. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12205–12207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochtermann, J.; Huber, M.; Korth, W.; Albert, J.; Jess, A. Extraction-Coupled Oxidative Desulfurization (ECODS) of n -Tetradecane as Model Oil under Moderate Conditions Using Molecular Oxygen. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 9452–9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Fu, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, W.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; Li, H. Bifunctional Pyridinium-Based Brønsted Acidic Porous Ionic Liquid for Deep Oxidative Desulfurization. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 152349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Hurlock, M.J.; Li, X.; Ding, G.; Kriegsman, K.W.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q. Efficient Oxidative Desulfurization Using a Mesoporous Zr-Based MOF. Catal. Today 2020, 350, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Qi, H.; Li, X.; Leng, K.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W. Enhancement of Oxidative Desulfurization Performance over UiO-66(Zr) by Titanium Ion Exchange. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 1903–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Kong, Y.; Fu, J.; Shaban, A.K.F.; Sun, Y.; Li, D. Solvent-Free Synthesis of Ce-Doped UiO-66(Zr) and Its Catalytic Performance in the Oxidative Desulfurization of Dibenzothiophene. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202500721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Yang, M.; Wang, G. Post-Synthetic Acid Treatment of Aqueous Synthesized Bimetallic Ce/Zr MOF-801 Enables Efficient Oxidative Desulfurization of Model Fuels. Fuel 2025, 401, 135846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavka, J.H.; Jakobsen, S.; Olsbye, U.; Guillou, N.; Lamberti, C.; Bordiga, S.; Lillerud, K.P. A New Zirconium Inorganic Building Brick Forming Metal Organic Frameworks with Exceptional Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13850–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Dai, E.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Y. Synthesis and Properties of Ferrocene Confined within UiO-67 MOFs. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 264, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazari, R.; Esrafili, L.; Morsali, A.; Wu, Y.; Gao, J. PMo12@UiO-67 Nanocomposite as a Novel Non-Leaching Catalyst with Enhanced Performance Durability for Sulfur Removal from Liquid Fuels with Exceptionally Diluted Oxidant. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 283, 119582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ye, J.; Han, Y.; Wang, P.; Fei, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Cui, M.; Qiao, X. Defective UiO-67 for Enhanced Adsorption of Dimethyl Phthalate and Phthalic Acid. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 321, 114477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, L.; Wang, L. Defect-Regulated and Amino-Functionalized UiO-67 for Efficient Removal of Tetracycline Hydrochloride from Aqueous Solutions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 193, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yang, W.; Yang, P.; Cao, Y.; Wang, F. Preparation of Defective UiO-67 for CA Immobilization to Improve the Ability of CO2 Capture and Conversion. Biochem. Eng. J. 2025, 216, 109661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; He, X.; Yang, W.; Luo, X.; Yu, Y.; Tang, W.; Yue, T.; Li, Z. Ratiometric Fluorescent Sensing Carbendazim in Fruits and Vegetables via Its Innate Fluorescence Coupling with UiO-67. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaate, A.; Roy, P.; Godt, A.; Lippke, J.; Waltz, F.; Wiebcke, M.; Behrens, P. Modulated Synthesis of Zr-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks: From Nano to Single Crystals. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 6643–6651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.-F.; Luo, D.; Li, D. A Size-Matched POM@MOF Composite Catalyst for Highly Efficient and Recyclable Ultra-Deep Oxidative Fuel Desulfurization. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Yang, M.; Wang, G. Defective Hierarchical Porous Ce-UiO-66 Excites Phosphotungstic Acid for Superior Low-Temperature Oxidative Desulfurization. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Xu, W.; Sun, Y. Enhancement of Catalytic Performance over MOF-808(Zr) by Acid Treatment for Oxidative Desulfurization of Dibenzothiophene. Catal. Today 2021, 377, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granadeiro, C.M.; Ribeiro, S.O.; Karmaoui, M.; Valença, R.; Ribeiro, J.C.; De Castro, B.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Balula, S.S. Production of Ultra-Deep Sulfur-Free Diesels Using a Sustainable Catalytic System Based on UiO-66(Zr). Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 13818–13821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Leng, K.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W.; Ma, S. Boosting Catalytic Performance of Metal–Organic Framework by Increasing the Defects via a Facile and Green Approach. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 34937–34943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Wan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhou, J.; Wu, L.; Zeng, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Boosting Catalytic Performance of MOF-808(Zr) by Direct Generation of Rich Defective Zr Nodes via a Solvent-Free Approach. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 4248–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhu, W.; Chang, Y.; Chao, Y.; Yin, S.; Liu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, H. Ionic Liquid Extraction and Catalytic Oxidative Desulfurization of Fuels Using Dialkylpiperidinium Tetrachloroferrates Catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 250, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooneh-Farahani, S.; Anbia, M. A Review of Advanced Methods for Ultra-Deep Desulfurization under Mild Conditions and the Absence of Hydrogen. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 108997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, B.N.; Jhung, S.H. Oxidative Desulfurization and Denitrogenation of Fuels Using Metal-Organic Framework-Based/-Derived Catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 259, 118021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, B.N.; Song, J.Y.; Khan, N.A.; Jhung, S.H. TiO2-Containing Carbon Derived from a Metal-Organic Framework Composite: A Highly Active Catalyst for Oxidative Desulfurization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 31192–31202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Chou, L.-Y.; Long, L.; Si, X.; Lo, W.-S.; Tsung, C.-K.; Li, T. Structural Control of Uniform MOF-74 Microcrystals for the Study of Adsorption Kinetics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 35820–35826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, M.; Song, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Huo, P. Tailored Linker Defects in UiO-67 with High Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer toward Efficient Photoreduction of CO2. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 1765–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Shi, J.-W.; Sun, G.; Ma, D.; He, C.; Pu, Z.; Song, K.; Cheng, Y. Au Nanodots@thiol-UiO66@ZnIn2S4 Nanosheets with Significantly Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic H2 Evolution: The Effect of Different Au Positions on the Transfer of Electron-Hole Pairs. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 282, 119550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Cheng, Z.; Klomkliang, N.; Koo-amornpattana, W.; Verpoort, F.; Chaemchuen, S. Hydro-Modulator Induced Defective Structure and Hieratical Pores in UiO-66 for Efficient Adsorption and Catalysis. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 42, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Chang, Y.H.; Lee, H.L. Crystallization Process Development of Metal–Organic Frameworks by Linking Secondary Building Units, Lattice Nucleation and Luminescence: Insight into Reproducibility. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Lv, Q.; Li, P.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J. Screening of Hierarchical Porous UiO-67 for Efficient Removal of Glyphosate from Aqueous Solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Du, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, J.; Bi, F.; Shi, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of Regulator Ratio and Guest Molecule Diffusion on VOCs Adsorption by Defective UiO-67: Experimental and Theoretical Insights. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 134510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Mao, C.; Li, Q.; Sun, H.; Fan, H.; Lv, Y. Preparation of P-Doped Spherical Bimetallic Oxides by Co-Immobilization of Acids for Sustainable Oxidative Desulfurization. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 174, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Mo-MOF-Based Ionanofluids for Highly Efficient Extraction Coupled Catalytic Oxidative Desulfurization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoste, J.B.; Peterson, G.W.; Jasuja, H.; Glover, T.G.; Huang, Y.; Walton, K.S. Stability and Degradation Mechanisms of Metal–Organic Frameworks Containing the Zr6O4(OH)4 Secondary Building Unit. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Bi, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, N. Defects Controlled by Acid-Modulators and Water Molecules Enabled UiO-67 for Exceptional Toluene Uptakes: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, G.C.; Chavan, S.; Bordiga, S.; Svelle, S.; Olsbye, U.; Lillerud, K.P. Defect Engineering: Tuning the Porosity and Composition of the Metal–Organic Framework UiO-66 via Modulated Synthesis. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 3749–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.