Abstract

This study presents a systematic approach for converting low-grade carbon derived from mining waste into functional carbon–zeolite composites with enhanced adsorption performance. To promote carbon deposition within and around zeolite frameworks, four industrially relevant zeolites, including zeolite socony mobil-5 (ZSM-5), Faujasite-type zeolite (Zeolite-Y), beta zeolite (Zeolite-β), and mordenite (MOR), were mechanically mixed with low-grade carbon under controlled stirring conditions (24 h at 250 rpm) and subsequently pyrolyzed at 800 °C. These treatments enabled a detailed assessment of structural stability and carbon–zeolite interactions. Scanning electron microscopy revealed pronounced modifications in surface morphology and carbon distribution after carbon treatment, while X-ray diffraction confirmed that the crystalline zeolite frameworks remained structurally intact despite the deposition of amorphous carbon. The adsorption performance of the resulting composites was evaluated through CO2 adsorption measurements under controlled temperature and pressure conditions, demonstrating a clear enhancement relative to the pristine zeolites. Overall, this work highlights an effective strategy for valorizing low-grade carbon waste into high-performance carbon–zeolite hybrid adsorbents and provides new mechanistic insights into framework stability, selective atom removal, and carbon–zeolite interactions in high-temperature and acidic environments.

1. Introduction

The ability of mesoporous zeolites to adsorb carbon dioxide (CO2) is largely dependent on their pore size, especially when these materials are loaded with subpar carbon sources. Growing concern about atmospheric CO2 levels and climate change has made advanced adsorbents with adjustable porosity essential for efficient gas collection and division applications [1,2]. Zeolites are prominent options for CO2 collection due to their high thermal stability, adaptable surface chemistry, and flexible pore design, particularly when their pore characteristics are tailored to target gas molecules [3,4,5]. According to experimental research, the relationship between pore diameter, the kinetic diameter of CO2 molecules (~3.3 Å), and the synergy of chemisorption through pore walls is important for CO2 adsorption mechanisms in zeolites. Small-pore zeolites provide improved adsorption capacity and increased kinetic selectivity because their crevices are appropriately matched to this dimension. The voids in mesopores and micropores may withstand the diffusion and maintain the active sites’ greater accessibility for mass transfer limitations. Furthermore, carbon loading mutates the pore shape and surface chemistry, which often increases overall capacity and improves the reliability and cost-effectiveness of CO2 capture materials [6,7,8]. Inaccurate or poorly calibrated pore size may result in ineffective CO2 adsorption or reduced selectivity. While too-small holes limit access and lower overall capacity, larger pores may promote diffusion but sacrifice surface interaction for adsorption. Low-grade carbon-loaded mesoporous zeolites have successfully tailored pore architectures and increased CO2 uptake by up to 22% when the unmodified form is modified by acid activation and the addition of carbonaceous precursors [9,10]. The importance of these findings is highlighted by emerging solutions that seek to balance mesopore accessibility and micropore volume to achieve optimal performance. This work shows that it is possible to combine low-grade carbon, which is a leftover waste material, with a zeolite framework to make a working hybrid CO2 adsorbent. The main point is that this process makes better use of a resource that is not being used enough. The resulting adsorption capacities are similar to those of the parent zeolite. The synthesis turns waste carbon into an active part without degrading the adsorbent’s core performance. This shows that eco-friendly material upcycling is possible. So, the study puts a circular economy approach, where recovering resources and making them useful again are important, along with traditional performance metrics, at the top of the list. In view of these considerations, the experimental study reported in this paper investigates the effect of various pore size profiles on the efficiency of CO2 adsorption in low-grade carbon-loaded mesoporous zeolites [11,12]. Four different types of zeolites, like Zeolite Socony Mobil-5 (ZSM-5), Faujasite-type Zeolite (Y), Beta Zeolite (β), and mordenite (MOR), have been selected as they follow green chemistry and act as tailored materials as they can react with both acid or base according to their requirement and pH factors. The chosen zeolites (ZSM-5, Y, β, MOR) for catalytic use have low Si/Al ratios to increase the amount of framework aluminum, which in turn gives them a high density of Brønsted acid sites. This strong acidity is necessary for the acid-catalyzed reactions being studied, like cracking and alkylation, which are in line with established principles for designing catalysts in refining and petrochemistry. So, the selection puts catalytic function ahead of adsorbent properties. By reviewing previous experimental and mechanistic studies, this study aims to offer new insights into material design methodologies that could support sustainable solutions for atmospheric CO2 mitigation [13].

2. Results

2.1. Powdered X-Ray Diffraction

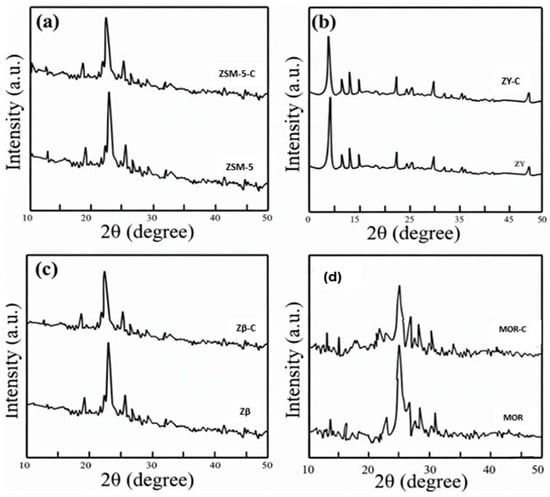

Zeolite-MFI samples were examined for phase purity using a Ni-filtered Rigaku powdered X-ray diffractometer with a 2θ scanning array of stuck between 5 to 60°. The XRD patterns of the delaminated zeolites ZSM-C, ZY-C, Zβ-C, and MOR-C are shown in Figure 1. Powder X-ray diffraction was used to evaluate the structural changes in the crystalline phase of zeolite frameworks (ZSM-5, Y, β, and MOR) both prior to and following treatment with low-grade carbonaceous waste. The treated samples are indicated by the suffix “-C” (ZSM-5-C, ZY-C, Zβ-C, MOR-C), and the representative diffractograms are shown in Figure 1a–d. Since all pristine samples exhibit the characteristic reflection pattern expected for their framework topologies, phase-pure zeolites were the starting materials.

Figure 1.

X-ray powder diffraction patterns of pristine and carbon-treated zeolites. (a) ZSM-5 and ZSM-5-C, (b) ZY and ZY-C, (c) Zβ and Zβ-C, (d) MOR and MOR-C.

The main framework reflections show that after carbon treatment, the parent framework identity is always maintained. However, the baseline, widths, and intensities of the diffractograms show systematic changes after treatment. The pristine MFI sample displays the distinctive MFI diffraction fingerprint, which includes the sharper multiplet in the 2θ ≈ 22–25° region and the low-angle reflections that characterize the MFI framework [14]. In line with the FAU topology, ZY (FAU) exhibits its characteristic intense low-angle reflections along with a wider range of peaks in the 2θ ≈ 6–12° and 23–25° regions [15].

Similarly, at the locations commonly reported for the BEA and MOR structures, the pristine β and MOR samples exhibit their respective framework-specific peak patterns. Prior to final submission, the peak positions and d-spacings were cross-validated against the corresponding ICDD/JCPDS reference cards and IZA structure files to ensure accurate phase identification. All observed reflections were compared to standard JCPDS/ICDD data (Table 1) and IZA structural parameters for the MFI, FAU, BEA, and MOR frameworks to identify peaks. All four zeolites maintain their distinctive framework reflections following carbon treatment, and no new crystalline phases emerge, indicating the integrity of the parent structures. The treated samples, however, exhibit three recurring alterations. The peak intensities are found to be decreased in all the framework reflections of MOR-C, Zβ-C, ZY-C, and finally ZSM-5-C. Improved contrast between the zeolite framework and the deposited carbon phase is suggested by this intensity enhancement, which is probably the result of either localized pore cleaning, partial removal of surface defects, or enhanced scattering contrast brought on by carbon occupying particular pore environments rather than uniformly blocking them. Second, all treated samples show a slight peak broadening (higher FWHM), which is indicative of decreased coherent domain size and/or micro strain brought on by thermal or chemical interactions during carbon modification. Third, the characteristic carbon (002) band near 26.5° (Cu Kα) partially overlaps with a broad low-intensity hump in the 20–30° 2θ range, which is most noticeable in ZSM-5-C and corresponds to amorphous carbon.

Table 1.

Reference XRD data, JCPDS cards, and lattice parameters for the zeolites studied.

With no indication of framework collapse or the formation of new crystalline carbon/oxide phases, these combined features confirm that the treatment introduces primarily non-crystalline carbon on the external surface or within the pore network while maintaining the MFI, FAU, BEA, and MOR lattice structures as reflected in Table 1. All zeolites maintain their distinctive framework reflections following treatment. All treated samples, however, show a diffuse hump in the 20–30° region that is consistent with amorphous carbon deposition along with systematic increases in peak intensity and moderate peak broadening. Mordenite experiences the highest degree of carbon incorporation or pore surface coverage, as indicated by the order of the degree of attenuation: MOR-C > Zβ-C > ZY-C > ZSM-5-C. These alterations are a result of low-grade carbon deposition-induced partial pore blocking, increased micro strain, and decreased diffracting volume [16].

2.2. Mechanistic Implications for CO2 Adsorption

Our materials fall into the same general category as many carbon-modified zeolite systems documented in the literature [17]. According to the XRD results (intact zeolite frameworks plus amorphous-carbon background/hump), the framework stays crystalline while carbonaceous deposits create a broad 20–30° feature and change peak intensities/widths. By adding complementary carbon microporosity and adjusting surface chemistry (oxygen/N-containing groups), thin, microporous, or templated carbon coatings on zeolites can improve CO2 uptake and stability without destroying the zeolite structure, according to previous studies [14]. For instance, microporous carbon-coated zeolite 13X materials demonstrated improved uptake and preserved framework order after controlled pyrolysis. In related work, zeolite-templated carbons (ZTC) made by CVD/templating exhibit strong CO2 physisorption linked to the carbon microporosity while retaining zeolite-derived porosity.

On the other hand, a number of reports caution [18] that non-porous or excessive carbon/coke can significantly reduce accessible zeolitic micropore volume and consequently lower CO2 capacity; in complementary BET/adsorption data, these samples frequently exhibit attenuated framework peaks and little beneficial carbon microporosity. The overall impact of carbon modification is highly sensitive to (i) carbon loading, (ii) carbon microstructure (amorphous vs. microporous/graphitic), and (iii) the spatial location of deposits (external surface vs. internal channels), according to broad reviews of zeolite modification for CO2 capture.

While pore-blocking coke decreases performance, optimized thin/porous carbon layers or templated carbons usually increase capacity or selectivity, as shown in Table 2 [19]. Applying those conclusions to our XRD, the carbon is probably disordered and present as a coating/infilling rather than crystalline graphite because the parent frameworks are still intact and the XRD displays a broad amorphous hump rather than a sharp graphite (002) peak. The observed sample-dependent intensity increase (MOR-C > Zβ-C > ZY-C > ZSM-5-C) indicates that carbon distribution and contrast vary among frameworks; for example, ZSM-5 exhibits the least change, whereas MOR and β may have acquired heavier or more scattering carbon deposits (or carbon in positions that enhance scattering contrast).

Table 2.

Comparison of XRD peak positions and intensities for pristine and carbon-treated zeolites.

Research indicates that while lower loadings or templated carbon inside channels can improve uptake, heavier, non-porous carbon coverage on some zeolite topologies can result in pore blocking and decreased CO2 capacity. Therefore, based solely on XRD, our samples may fall into a middle ground moderate, mostly amorphous carbon coverage that could either decrease uptake if the carbon is primarily pore-blocking or preserve or slightly improve CO2 uptake if the carbon is microporous.

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis

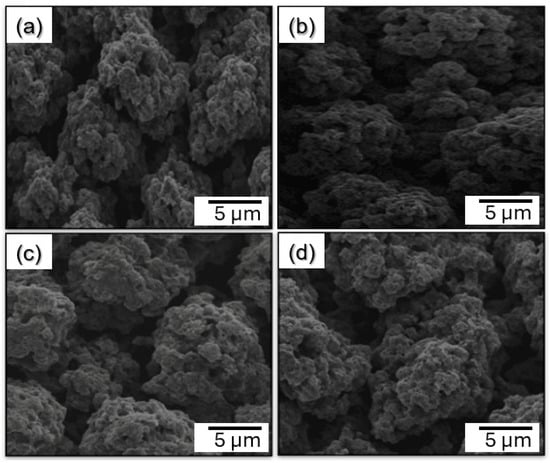

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is a way to take pictures with a lot of detail by scanning the surface of a solid sample with a focused beam of electrons. When the electron beam hits the sample, it sends out different signals, such as secondary electrons. These signals are picked up to create a detailed, three-dimensional-like picture of the surface structure at the micro- to nanoscale. Many people use SEM to look at the size, shape, texture, porosity, and surface structure of particles. SEM was used to examine the surface morphology and textural structure of the zeolite samples ZSM-C, ZY-C, Zβ-C, and MOR-C. Each sample’s representative SEM micrograph is shown in Figure 2, displaying unique morphological characteristics related to the frameworks and synthesis circumstances of each sample. ZSM-C’s SEM micrograph (Figure 2a) shows an aggregated structure made up of closely spaced, asymmetrical crystallites with a coarse surface texture. Because there are many exterior facets and microchannels, this microstructural compactness probably leads to a relatively tiny average pore size, which correlates with increased surface area. A feature perfect for tiny pore zeolites, the densely packed domains imply reduced macroporosity but well-developed micropores due to the minimal interparticle spaces.

Figure 2.

SEM images showing the morphology and texture of zeolites after carbon treatment, (a) ZSM-C, (b) ZY-C, (c) ZB-C, and (d) MOR-C.

Figure 2b shows that ZY-C has larger, loosely organized crystallites with noticeable interstitial spaces between aggregates as compared to ZSM-C. Increased mesoporosity or macroporosity is indicated by a slightly smoother and less fractured particle surface. These textural characteristics enable better molecular diffusion and accessibility in large pore zeolites intended for CO2 adsorption with greater capacity. Zβ-C shows well-formed, spherical aggregates with significant surface roughness and moderate porosity, as shown in Figure 2c. The interconnectedness of the particles and the presence of both large and tiny cavities on the exterior surface suggest a mixed mesoporous–macroporous structure. Because of its shape, which encourages a balance between surface area and straightforward gas transport routes, Zβ-C is ideal for applications aiming for quick adsorption kinetics. MOR-C’s granular shape and less obvious aggregation led to more isolated crystallites and relatively smoother surfaces, as can be seen in Figure 2d. Medium pore zeolites, which have developed intra-particle channels but little microporosity, are typified by this microstructure. The described properties might result in moderate surface area and pore volume, which would be consistent with the intermediate adsorption performance typically seen for frameworks of the ferrierite type. The SEM analyses typically validate textural characteristics inferred from physico-chemical measurements (surface area, pore volume, and average pore size). ZSM-C’s compact crystallite dispersion sustains its classification as a tiny-pore zeolite. FER-C’s intermediate particle separation indicates its status as a medium pore zeolite, whereas ZY-C and Zβ-C’s larger and more open structures correspond to large pore architectures. These morphologies highlight how important pore size and particle connectivity are in adjusting zeolite-based materials’ adsorption characteristics for CO2 capture.

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of Pore Size in Molecular Sieves

The physical properties of both commercial and modified microporous zeolite samples are compiled in Table 3. Modified zeolites show a notable decrease in pore volume and surface area as the Si/Al ratio rises (Si/Al = 5, Si/Al = 3, Si/Al = 4, Si/Al = 15). In this case, they might be very significant, particularly those with high surface area and porosity in zeolite channels.

Table 3.

Physical Properties of Zeolites.

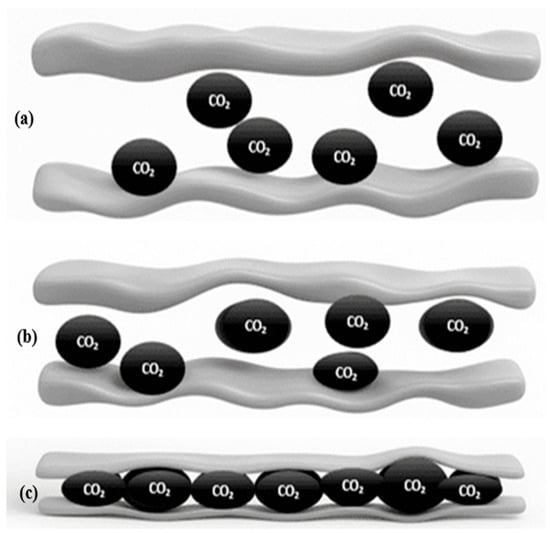

Crystallinity is stable and affected by low-grade carbon, as it increases adsorption capacity, as shown in Figure 3. Their high adsorption capacity, highly repeatable adsorption behavior, stability in a variety of conditions, commercial availability, and ease of regeneration are the reasons for this. They may be excellent options for high-pressure storage applications due to their large adsorption capacity, even though they have a relatively low affinity for CO2. The adsorption behavior of CO2 molecules in zeolite pores of various sizes is depicted in Figure 3. Large pores allow CO2 molecules to be less confined, resulting in weaker interactions with the pore walls. Medium-sized pores allow for better adsorption through closer contact and supply a better balance between confinement and space. Small pores exhibit the highest degree of confinement because CO2 molecules pack more densely and interact strongly with the internal surface, increasing adsorption capacity. This comparison shows that pore size and CO2 uptake efficiency are directly related [20].

Figure 3.

Representation of CO2 adsorption in zeolite pores of varying dimensions: (a) large pores, (b) medium pores, and (c) small pores, showing the effect of pore size on molecule confinement and adsorption capacity.

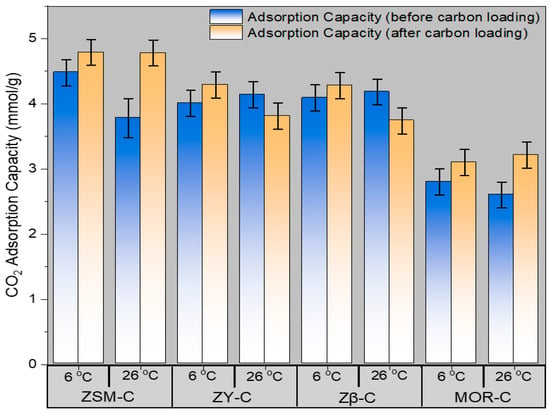

3.2. CO2 Adsorption Capacity Analysis

The CO2 adsorption capacities of four zeolite types (ZSM-C, ZY-C, ZB-C, and MOR-C) before and after carbon loading measured at 6 °C and 26 °C are given in Table 4. The reported values represent the average of three independent measurements. The findings point to a few important trends that are relevant to the development of CO2 capture systems based on zeolites. As shown in Figure 4, the CO2 absorption capacity of all zeolites increases with carbon addition, with the effect being particularly pronounced at the lower temperature of 6 °C. ZSM-C (HZSM-5-C) increases noticeably from 4.48 mmol/g (before) to 4.79 mmol/g (after) at 6 °C, and from 3.78 mmol/g to 4.78 mmol/g at 26 °C; the increase is even more pronounced. Similar improvements are seen in ZB-C (Zeolite Beta β) and MOR-C, where higher uptake results from post-modification. From 2.60 mmol/g to 3.21 mmol/g at 26 °C and from 2.80 mmol/g to 3.10 mmol/g at 6 °C, MOR-C shows a notable improvement at both temperatures. The results for ZY-C (Zeolite-Y) are more complicated, as it has been seen that the capacity rises at 6 °C (from 4.01 mmol/g to 4.29 mmol/g) but falls at 26 °C (from 4.14 mmol/g to 3.81 mmol/g) after carbon is loaded. This implies that for certain large-pore zeolites, pore accessibility and the best adsorbate interaction at high temperatures may be compromised.

Table 4.

Adsorption Capacities of Zeolites at 6 °C and 26 °C.

Figure 4.

Provisional study showing measured values for ZSM-C, ZY-C, ZB-C, and MOR-C zeolite catalysts at 6 °C and 26 °C, analyzing temperature-dependent performance differences. The error bars represent the standard deviation calculated from three independent experimental measurements.

Overall, the pattern indicates that CO2 adsorption is consistently improved by increased surface area and pore volume following carbon loading, particularly at lower temperatures when physisorption predominates the adsorption mechanism. This phenomenon is caused by improved CO2 molecule packing as well as improved active site dispersion and accessibility within the zeolite framework. The variations in zeolite types show how pore size and structure impact adsorption effectiveness, emphasizing the necessity of tailoring pore architecture to optimize CO2 capture. These findings corroborate the theory that rational pore engineering by carbon loading is a successful method of boosting CO2 adsorption capacity in mesoporous zeolites, with the best outcomes coming from choosing the right zeolite type and operating temperature. The observed order of CO2 adsorption capacity (ZSM-5 > β > Y > MOR) can be primarily attributed to the interaction of effective micropore volume accessible to CO2, framework density, and acid site density/distribution, rather than total surface area alone. The variation in CO2 adsorption capacity among carbon-zeolite hybrids is influenced by the interplay of accessible micropore architecture, site density, and the effects of carbon confinement, rather than solely by total surface area. ZSM-5 has the highest capacity because it has 3D intersecting channels and a high acid-site density from a low Si/Al ratio, which makes it easy for CO2 to get in and out and makes strong interactions possible.

Zβ has a 3D 12-ring system that makes it well connected and big, but the way the sites are spread out might not be as good. ZY has big supercages, but its capacity is lower than expected. This is probably because the carbon phase fills some of the pores, which affects larger cavities more than smaller ones. Lastly, MOR has the lowest capacity because its 1D channel system is very likely to get blocked by carbon buildup, which makes it very hard for CO2 to diffuse and for sites to be reached. So, the hierarchy shows a balance between the geometry of the framework and the way that integrated carbon changes how well the pores are used. The 3D interconnected micropores in ZSM-5 and Zβ stay open even after carbon modification, which is good for them. However, the larger-pore Y and especially the 1D-pore MOR have more trouble with diffusional limitations or pore filling by the carbon phase, which lowers their ability to adsorb CO2.

3.3. Principle of CO2 Adsorption on Carbon-Modified Zeolites (ZSM-C, ZY-C, Zβ-C, MOR-C)

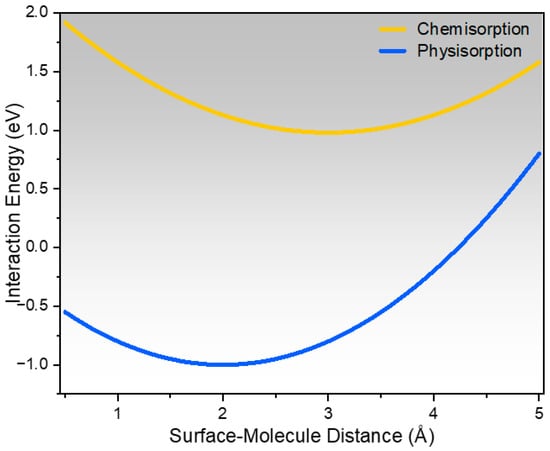

The CO2 adsorption mechanism on carbon-modified zeolites through a theoretical interaction energy profile is illustrated in Figure 5. The graph compares the energy wells related to physisorption and chemisorption as a function of the surface-molecule distance. Weak, reversible interactions that are primarily governed by van der Waals forces and micropore confinement are indicated by a shallow minimum in the physisorption curve. This characteristic is demonstrated by the intrinsic zeolite framework, which allows CO2 to be contained inside uniform micropores with little to no electronic rearrangement. Conversely, the chemisorption curve exhibits a deeper energy well, indicating a more robust interaction between CO2 molecules and the basic surface functions resulting from carbon alteration. Lewis’s acid-base interactions enable weak chemisorptive binding with acidic CO2 due to the increased density of oxygenated functional groups and π-electron-rich sites found in low-grade carbon deposits. This deep energy minimum reflects the increased adsorption potential observed in samples treated with carbon in experiments. The difference between the two curves clearly indicates the synergistic adsorption mechanism in carbon-treated zeolites. The zeolite micropores enable size-selective physisorption, and the carbon deposited on the surface introduces more basic sites that are better able to stabilize CO2. This dual interaction enhances the overall adsorption efficacy, which is consistent with the higher CO2 uptake observed in ZSM-C, ZY-C, Zβ-C, and MOR-C. Thus, this concept graph confirms the experimental result that carbon modification increases the intensity and affinity of CO2 adsorption by introducing stronger interaction sites while preserving the microporous characteristics of the zeolite framework. The CO2 adsorption capacity is substantially enhanced after carbon loading owing to the introduction of supplementary basic and electron-rich surface functional groups, which interact strongly with the acidic CO2 molecules through acid-base and electrostatic forces. CO2 binding strength upgrades as the modified surface facilitates improved adsorption affinity by creating π-electron domains. As a result, carbon-modified zeolites display higher uptake and better selectivity toward CO2 compared to unmodified zeolites.

Figure 5.

Interaction energy (eV) versus surface–molecule distance (Å) for CO2, comparing physisorption and chemisorption on carbon-treated zeolite surfaces.

A comparative analysis of the CO2 adsorption capacity provides additional context for the performance of the waste-derived carbon-zeolite hybrid. If the temperature is 25 °C and the pressure is 1 bar, the hybrid can hold 2.8–3.2 mmol/g. This is on par with traditional adsorbents like zeolite 13X (3.0–3.5 mmol/g) [21] and better than activated carbons (2.0–2.5 mmol/g) [22]. It also fits in with the mid-range performance of more synthetically complex amine-modified composites [23]. The key discovery is not a record capacity, but the ability to turn a low-value carbon waste into a useful hybrid material that works as well as established engineered adsorbents. This makes the synthesis a long-term way to make useful CO2 capture materials that follow the principles of a circular economy while still working well. The developed carbon–zeolite composites are promising for CO2 capture–assisted catalytic processes, particularly in applications requiring CO2 adsorption and activation prior to catalytic conversion, such as dry reforming, methanation, and carbon capture and utilization (CCU) systems, where strong chemisorption and high surface accessibility are essential.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemical Used

Unmodified forms of the commercial zeolites ZSM-5, Y, β, and MOR, with Si/Al ratios of 5, 3, 4, and 15, respectively, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, New Delhi, India. Low-grade carbon was obtained from the Central Mine Planning and Design Institute Ltd, Ranchi, India. The adsorption tests were conducted using analytical-grade CO2 (99.9%) and N2 (99.99%).

4.2. Infusion of Low-Grade Carbon into Zeolite Framework

ZSM-5 (small pore), MOR (middle pore), Zeolite-Y, and Zeolite-β (large pore) were commercially obtained with Si/Al ratios ranging from 3 to 15. Each zeolite was impregnated with low-grade carbon using a hydrothermal impregnation technique to guarantee that pre-adsorbed species were eliminated in compliance with established protocols [24]. By combining heat, pressure, and an aqueous medium, this technique effectively removes any pre-adsorbed species from the surface and guarantees consistent carbon distribution throughout the 3-dimensional voids of zeolite. The pre-weighed zeolite powder of 2 g was thoroughly combined with 1 g of low-grade carbon (mining waste) in distilled water and loaded in an autoclave. The resultant suspension was moved to a stainless-steel autoclave lined with Teflon to ensure a tight seal and sustain autogenous pressure. According to established literature [25], the mixture was hydrothermally treated for 24 h at 140 °C. The resulting solution was filtered with sumptuous, deionized water to remove the impurities. The resulting cake was dried at 120 °C for 12 h before the calcination process of 550 °C for 3 h, which modified the physicochemical properties of zeolites.

This methodology results in a composite material where the zeolite framework retains its structural integrity while being integrated with a dispersed carbon phase. The outcome is a tailored pore architecture with significant surface area and improved molecular accessibility, all of which are critical factors for enhancing CO2 adsorption capacity. Furthermore, this approach allowed for repeatable and controlled carbon loading.

4.3. Structural Analysis

The surface and cross-sections of carbon-loaded zeolites were observed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) (JSM-IT800SHL, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The structure of the zeolites, including pore volume, diameter, and surface area, was measured both before and after carbon injections as part of the physicochemical characterization process. Nitrogen physisorption was used for these evaluations, and XRD patterns were measured for all the samples. Adsorption capacity was measured at 6 °C and 26 °C using a gravimetric analyzer at equilibrium pressures of 81–96 kPa for CO2 adsorption studies, which involved packing 3 mg of each zeolite into a stainless-steel column. To quantify the impact of pore structure modifications on adsorption efficiency, the amount of CO2 adsorbed was measured both before and after carbon modification.

4.4. Surface Area

Quantification of the surface area of the material is very important for any study on nanoporous materials, as it directly influences the reactivity and adsorption properties. The zeolites were analyzed using a Sorptomatic 1990 Thermo Finnigan (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to determine Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area, employing nitrogen adsorption at liquid-nitrogen temperature (77 K) for adsorption experiments. Prior to adsorption investigations, the samples were outgassed for 15 h at 473 K using helium as the carrier gas and a TCD detector. The surface area from the N2 adsorption isotherm was computed using the built-in software of the Sorptomatic 1990 instrument.

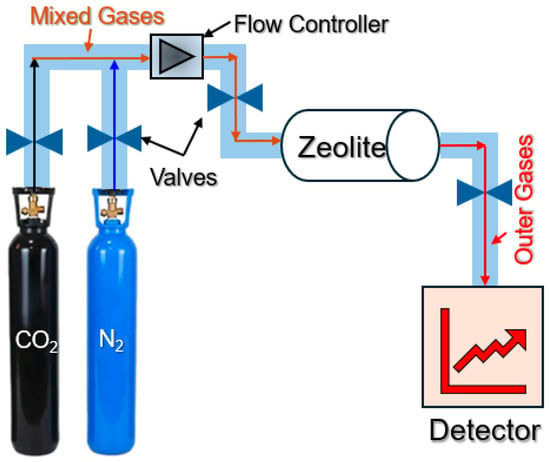

4.5. Adsorption Studies Using Calorimetric Analysis

Gas–solid interactions were investigated using tubular microreactors, as displayed in Figure 6. The adsorption experiments for CO2 gases at 6 °C and 26 °C are carried out to quantitatively screen the adsorption properties of the gases. The insulated polymeric material is used to achieve stability in the experiment and allow the temperature to remain constant for optimizing the adsorption rate. Before the adsorption studies, all the zeolite catalysts were outgassed for 24 h at 350 °C under a 5 μm Hg vacuum. The zeolites are outgassed prior to each experiment while being heated from 26 °C to 270 °C with a ramping rate of 1 °C per minute. After the sample reached 270 °C for 5 h, it was cooled to room temperature at a rate of 1 °C per minute. To prevent the catalyst flush out by gas flow and pressure, 3 mg of zeolite is placed in the center of a tubular reactor with quartz wool supporting it on both sides, as demonstrated in the experiment setup. After being combined with CO2 and N2, the tubular reactor input flow is passed through treated zeolite. The full amount of gas adsorbed is used to calculate the zeolite adsorption rate. The product gas stream was analyzed by online gas chromatography (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a 60/80 carboxen EN 1000 molecular sieve column.

Figure 6.

The microreactor setup for CO2 adsorption.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a direct correlation between zeolite pore size and CO2 adsorption behavior, suggesting that molecular confinement is a critical factor regulating uptake efficiency. Loading of low-grade carbon intensified the adsorption performance of zeolite by altering surface chemistry and enriching pore architecture. The resulting composite showed improved CO2 affinity, higher uptake, and better stability, justifying the potential for efficient post-combustion separation and applied environmental usage. Structural characterization using XRD confirmed that all zeolite frameworks (MFI, FAU, BEA, and MOR) remained intact following carbon treatment, despite SEM images showing surface texture changes and the presence of amorphous carbon deposits affecting pore accessibility. Large pores showed limited confinement and weaker CO2 surface interactions, whereas medium pores provided an optimal balance of space and interaction strength, enhancing adsorption. High confinement in small microporous channels demonstrated the best performance, enabling stronger van der Waals interactions and dense CO2 packing. These findings show that careful pore size adjustment and structural integrity preservation are necessary to produce high-performance zeolite-based CO2 adsorbents suitable for practical carbon-capture applications. The study highlights that optimizing pore size is crucial for increasing CO2 absorption across carbon-loaded mesoporous zeolites. Larger, more interconnected pores promote rapid CO2 diffusion and stable adsorption, which greatly boosts capture capacity. These results demonstrate how engineered zeolitic materials can be used as cost-effective adsorbents to lower greenhouse gas emissions. The development of scalable adsorption modules for use in industrial settings, hierarchical pore tailoring, and active-site modification should be the main focus of future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.B. and S.K.T.; methodology, N.G.S.R.; software, M.I. and H.J.B.; validation, S.K.T., J.K. and M.I.; formal analysis, S.K.T.; investigation, N.G.S.R. and A.G.B.; resources, S.K.T.; data curation, S.K.T., J.K. and M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J.B., M.I., N.G.S.R. and A.G.B.; writing—review and editing, N.G.S.R.; visualization, A.G.B. and N.G.S.R.; supervision, A.G.B.; project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00338965).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The Authors thank SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Delhi NCR Campus, Ghaziabad, for the research assistance to carry out this work. One of the authors, Sweta Kumari Tripathy, would like to thank A. Geetha Bhavani and her team for providing the laboratory and analytical instrument facilities that enabled the completion of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| ZTC | Zeolite-templated Carbon |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

References

- Schneider, M.; da Costa, D.G.S.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Guerrero-Pérez, M.O.; Hotza, D.; De Noni, A.; Moreira, R.d.F.P.M. Influence of Curing Temperature on the Synthesis of a Phosphate-Waste-Based Geopolymer for CO2 Capture and Separation. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 8004–8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecilia, J.A.; Vilarrasa-García, E.; Cavalcante, C.L.; Azevedo, D.C.S.; Franco, F.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E. Evaluation of Two Fibrous Clay Minerals (Sepiolite and Palygorskite) for CO2 Capture. J. Env. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4573–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavani, A.G.; Reddy, N.S.; Joshi, B.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, P. Enhancing the Adsorption Capacity of CO2 over Modified Microporous Nano-Crystalline Zeolite Structure. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 64, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Ullah, S.; Zhou, K.; Li, X.Y.; Li, S.; Mao, S.; Thonhauser, T.; Tan, K.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Carbon Dioxide Capture by a Hydrothermally Synthesized Water-Resistant Zinc-Oxalate-Aminotriazolate Framework. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 16504–16513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khotina, I.A.; Naumkin, A.V.; Pastukhov, A.V.; Kovaleva, M.A.; Kupriyanova, D.V.; Revizorova, N.S.; Lubimov, S.E.; Kovalev, A.I.; Mezhuev, Y.O. Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide by Functional Carbon Materials Obtained by Pyrolysis of Polyphenylenepyridines. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.C.; Silva Junior, M.M.; Felix, C.S.A.; da Silva, D.L.F.; Santos, A.S.; Santos Neto, J.H.; de Souza, C.T.; Cruz Junior, R.A.; Souza, A.S. Multivariate Optimization Techniques in Food Analysis–A Review. Food Chem. 2019, 273, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Hong, S.B. Effect of Framework Si/Al Ratio on the Mechanism of CO2 Adsorption on the Small-Pore Zeolite Gismondine. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.H.; Li, P.; Yuan, H.; Huang, W.; Hu, Z.; Yang, R.T. CO2 Capture by ZSM-5 with Varied Si/Al Molar Ratios: Isothermal Adsorption Capacity of CO2 vs Dynamic CO2 Adsorption Capacity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoa, V.T.M.; Khang, N.M.; Duy, B.N.N.; Phuong, N.T.T.; Duong, N.T.H.; Long, N.Q. Enhancing CO2 Adsorption via Metal Cation Exchange of GIS and GIS–FAU Zeolites. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2025, 19, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megías-Sayago, C.; Bingre, R.; Huang, L.; Lutzweiler, G.; Wang, Q.; Louis, B. CO2 Adsorption Capacities in Zeolites and Layered Double Hydroxide Materials. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 466568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Gong, C.; Chen, M.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, J.; Shi, J.; Liu, H.; Teng, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y. Application of Synchrotron Radiation Based X-Ray Diffraction in Zeolite Research: Advanced Analysis from Atomic Structure to Dynamic Behavior. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e15141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.T.; Kim, J.; Ahn, W.S. CO2 Adsorption over Ion-Exchanged Zeolite Beta with Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metal Ions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 135, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwana, K.P.; Malek, N.I.; Kailasa, S.K. Colloidal Perovskite Nanomaterials: New Insights on Synthetic Routes, Properties and Sensing Applications. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2025, 344, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, Z.; Lu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, D.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, H.; Alhassawi, H.; Feng, Z. Transformation in Ring Topology of Beta Zeolite Induced by Chelation: Implications for CO2 and Toluene Adsorption under Humid Conditions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, R.; Kaneko, H. Development of a Model for Predicting the Adsorption Performance of Zeolites and Designing New Zeolites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 10353–10359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Yu, J.; Chai, B.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.X.; Sun, D.; Lei, Y. Tailored Gas–Solid Interfacial Selectivity of Porous Polyionic Liquid Monoliths for High-Efficiency PM Interception and Accurate CO2 Sieving. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 34396–34408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhao, H.; Fan, X.; Li, G.; Meng, H.; Liu, H. Organic-Free Preparation of Beta with Hierarchical Pores via a Potassium Carbonate-Assisted Method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 17507–17513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaing, E.M.; Puyathorn, N.; Yodsin, N.; Phonarwut, N.; Thammasut, W.; Rojviriya, C.; Pichayakorn, W.; Phattarateera, S.; Phaechamud, T. Development and Evaluation of Cellulosic Esters Solvent Removal-Induced In Situ Matrices for Loading Antibiotic Drug for Periodontitis Treatment. Polymers 2025, 17, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basri, E.S.H.; Krisnandi, Y.K.; Ekananda, R.; Saragi, I.R. Bangka Kaolin and Bayat Zeolite-Based ZSM-5 Zeolite as Heterogeneous Catalyst for Hexadecane Cracking Reaction. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 763, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Synthesis of Hierarchical High-Silica Beta Zeolites in NaF Media–RSC Advances (RSC Publishing). Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2019/ra/c8ra09347d (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Chatti, R.; Bansiwal, A.K.; Thote, J.A.; Kumar, V.; Jadhav, P.; Lokhande, S.K.; Biniwale, R.B.; Labhsetwar, N.K.; Rayalu, S.S. Amine Loaded Zeolites for Carbon Dioxide Capture: Amine Loading and Adsorption Studies. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 121, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Albero, J.; Wahby, A.; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A.; Martínez-Escandell, M.; Kaneko, K.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Ultrahigh CO2 Adsorption Capacity on Carbon Molecular Sieves at Room Temperature. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6840–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutka, H.; Sjostrom, S.; Starns, T.; Dillon, M.; Silverman, R. Post-Combustion CO2 Capture Using Solid Sorbents: 1 MWe Pilot Evaluation. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yan, C.; Alshameri, A.; Qiu, X.; Zhou, C.; Li, D. Synthesis and Characterization of 13X Zeolite from Low-Grade Natural Kaolin. Adv. Powder Technol. 2014, 25, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Luo, X.; Chen, X. Insights into the Synthesis of Spiral Beta Zeolite with Enhanced Catalytic Performance in VOC Abatement. Molecules 2024, 29, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.