Abstract

In recent years, biomass utilization has attracted extensive attention. Herein, hexagonal/cubic ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) heterojunction catalysts were synthesized via a solvothermal method for the selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) to 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF). The results demonstrated that the constructed heterojunctions effectively promoted carrier separation. The optimal catalyst achieved an HMF conversion rate of 88.8% and a DFF yield of 86.6% within 1 h in the open air. X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) characterizations confirmed the successful fabrication of the composite phase structure and revealed a porous spherical morphology. Equivalent circuit fitting of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data indicated that the hexagonal/cubic heterojunctions possessed the lowest charge transfer resistance (Rct = 5825 Ω), which effectively reduced interfacial charge transfer resistance and accelerated the transport of photoinduced carriers. Radical quenching experiments and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy identified superoxide radicals (·O2−) as the primary reactive species. Meanwhile, density functional theory (DFT) calculations elucidated the formation of the built-in electric field and the charge transfer mechanism. This work’s construction of Type-II ZIS heterojunctions effectively addressed the issue of rapid carrier recombination in pristine ZIS materials, providing a feasible strategy for biomass valorization.

1. Introduction

The excessive consumption of fossil resources has resulted in serious energy crises and environmental pollution, driving extensive research into renewable alternatives [1,2,3]. As one of the most abundant and sustainable carbon sources, biomass has attracted considerable attention as a promising substitute for fossil feedstocks [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Its efficient conversion into high-value-added chemicals is essential to mitigate energy dependency and achieve carbon neutrality. Among various biomass-derived platform molecules, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) stands out as a key intermediate due to its versatile functional groups [11]-furan ring, hydroxyl, and aldehyde-which enable its transformation into a range of valuable products [12], including but not limited to 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF), 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (HMFCA), 5-formyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (FFCA), as well as 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) [13,14,15,16,17]. In particular, DFF has garnered significant interest for its broad applications in pharmaceuticals, polymeric materials, fine chemicals, and functional materials such as Schiff bases and antimicrobial agents [18]. However, conventional strategies for HMF oxidation-especially thermocatalytic methods-often rely on noble metal catalysts or strong oxidants under energy-intensive conditions (e.g., elevated temperature and high pressure) [19], leading to high costs, environmental concerns, and limited sustainability [20,21]. In response, there is a growing emphasis on developing efficient, eco-friendly, and economically viable catalytic systems. In this context, photocatalysis has emerged as an attractive alternative, offering a mild, energy-saving, and selective approach for the oxidation of HMF toward DFF and other value-added chemicals, holding great potential for enabling sustainable biomass upgrading [22,23].

As a ternary metal sulfide semiconductor [24,25], ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) has garnered much attention in oxidative photocatalysis owing to its strong visible-light absorption (band gap ~2.3–2.6 eV), suitable band edge positions [26,27,28], and intrinsic mild oxidation capability that hardly leading to over-oxidation. It exists generally in two crystalline phases: hexagonal and cubic forms [29]. The hexagonal phase exhibits a layered two-dimensional (2D) structure with a larger specific surface area and more exposed active sites, that facilitates charge carrier separation and reactant adsorption. In contrast, the cubic phase often shows higher crystallinity and electronic conductivity but offers fewer accessible surface sites and a reduced specific surface area, limiting its photocatalytic performance [30]. Despite these advantages, ZIS still suffers from rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, low efficiency in carrier utilization, and insufficient surface active sites [31]. Particularly, the saturated terminal S atoms usually exhibited poor activation ability for oxygen molecules, hindering the generation of the essential superoxide radicals (·O2−) for selective oxidation. To overcome these limitations, recent strategies have focused on structural modification and co-catalyst integration [32]. For instance, constructing heterostructures by combining ZIS with organic semiconductors such as self-assembled perylene diimide (SA-PDI) supermolecules can enhance interfacial charge transfer [33,34], promote oxygen reduction, and tailor the energy band alignment. Furthermore, defect engineering (e.g., introducing S and Zn vacancies or dopants like O or single-atom Ni) has been employed to optimize the electronic structure [35,36,37,38], promote carrier separation [39,40], and create highly selective active sites for HMF oxidation. Such modifications not only improve photocatalytic efficiency and DFF selectivity, but also enable simultaneous H2 evolution [41,42,43], demonstrating great potential for efficient and sustainable biomass valorization. Compared with the above-mentioned strategies, the heterojunctions constructed by ZIS itself feature simpler preparation, stronger compatibility, and more stable interfacial combination. Therefore, taking advantage of the intrinsic difference in the band positions between cubic and hexagonal ZIS, it is promising to construct heterojunctions between hexagonal and cubic ZIS phases. Importantly, the critical issues of low charge separation efficiency and poor photocatalytic performance of single-phase ZIS would be simultaneously addressed in the protocatalytic oxidation processes.

In this study, constructing a heterojunction between the hexagonal and cubic phases of ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) effectively integrates the advantages of both crystalline structures. The formation of such a heterojunction generates an internal electric field at the interface, which greatly promotes the separation and migration of photogenerated carriers. This strategy is characterized by three key innovations: (1) Expanding the research focus of ZIS-based catalysts from sole dye degradation (e.g., Rhodamine B) to renewable resource valorization; (2) Constructing a Type-II heterojunction by combining hexagonal and cubic ZIS with optimized mass ratios, which effectively addresses the issue of rapid carrier recombination in pristine ZIS materials; (3) Elucidating that the reaction is mediated by superoxide radicals (·O2−) and confirming the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) through mechanistic investigations. Eventually, our study achieves an HMF conversion rate of 88.8% and a DFF selectivity of 95.7% under mild conditions. Compared with existing studies (Table S5), the photocatalytic performance for the selective oxidation of HMF to DFF is significantly enhanced. Overall, this work provides a promising strategy for the development of efficient photocatalytic systems for biomass valorization.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphology and Structure Characterization of the Catalysts

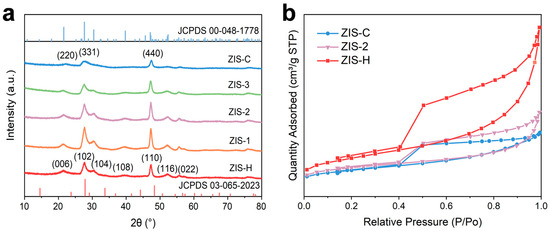

In the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern (Figure 1a), hexagonal ZnIn2S4 (ZIS-H) displayed characteristic diffraction peaks assigned to the (006), (102), (104), (108), and (110) crystal planes, respectively, which aligned well with the standard diffraction data for hexagonal ZnIn2S4 (JCPDS No. 03-065-2023). Conversely, cubic ZnIn2S4 (ZIS-C) exhibited typical cubic-phase diffraction peaks (e.g., (220), (331), (440)), consistent with the reference data for cubic ZnIn2S4 (JCPDS No. 00-048-1778). For the composite samples (ZIS-1, ZIS-2, ZIS-3) synthesized with the variation in ZIS-H/ZIS-C ratios, a distinct gradual evolution in diffraction behavior was observed. As the proportion of cubic ZIS-C in the composite increases, the intensity of hexagonal-phase characteristic peaks (e.g., (006), (108)) corresponding to ZIS-H gradually diminished, accompanied by peak broadening (indicating reduced crystallinity), while the cubic-phase characteristic peaks (e.g., (331), (440)) progressively intensify and became prominent. This result not only confirmed that ZIS-1–ZIS-3 were hexagonal/cubic ZnIn2S4 composite-phase structures (free of impurity phases), but also demonstrated that tuning the composite ratio enables directional regulation of the samples’ crystal phase composition, preferential crystal plane exposure, and crystallinity. Figure 1b presented the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of ZIS-H, ZIS-C and ZIS-2 catalysts. All samples exhibited type IV isotherms with H3-type hysteresis loops; combined with the pore size data (Table S2), these catalysts could be identified as mesoporous materials. The specific surface area and pore volume of ZIS-2 were 44.84 m2/g and 0.09 cm3/g, respectively, which were higher than those of ZIS-C (38.88 m2/g and 0.06 cm3/g). These results clearly confirmed that the heterojunction formed by ZIS-C and ZIS-H effectively increased the specific surface area and pore volume of the material, thereby providing abundant active sites for the catalytic reaction.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD patterns of ZIS-C, ZIS-H, and ZIS composites. (b) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of ZIS-H, ZIS-C, and ZIS-2.

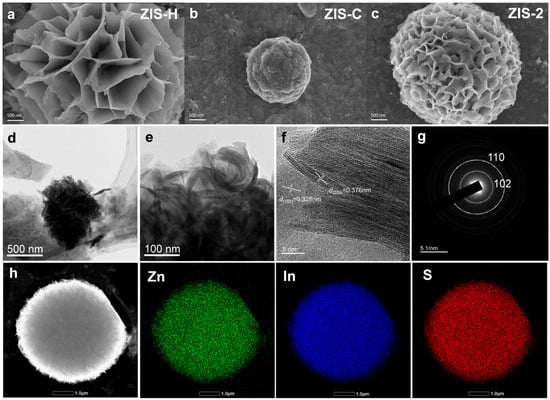

Figure 2a–c and Figure S5 presented the scanning electron microscope (SEM) characterization of the catalysts. ZIS-H exhibited a layered and wrinkled flower-like architecture, constructed by the stacking of numerous thin sheets, which featured distinct lamellar structures. In contrast, ZIS-C appeared as dense spherical aggregates, with their surfaces formed by the irregular accumulation of fine particles and no obvious lamellar characteristics. For the composite sample ZIS-2, its morphology demonstrated a synergistic combination of both components: it not only retained the lamellar units inherited from ZIS-H, but also formed a porous spherical structure via the curling and assembly of these lamellae, showing a more prominent hierarchical architecture with abundant surface pores. As shown in Figure S5g–i, the average particle sizes of ZIS-H, ZIS-C, and ZIS-2 were approximately 6.91, 6.48, and 7.54 μm, respectively. Figure 2d,e displayed the TEM images of the catalyst. Particularly, lattice fringes can be clearly observed via high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (Figure 2f). The interplanar spacings of 0.325 nm and 0.376 nm correspond to the (102) plane of ZIS-H and the (220) plane of ZIS-C, respectively, further confirmed the existence of the hexagonal/cubic heterojunction. Furthermore, the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of ZIS-2 also clearly reflected the (102) and (110) crystal planes (Figure 2g), which is consistent with the XRD results. The element mapping analysis revealed that Zn, In, and S elements were uniformly dispersed in the ZIS-2 composite (Figure 2h).

Figure 2.

SEM images of (a) ZIS-H, (b) ZIS-C, and (c) ZIS-2. (d,e) TEM image, (f) HRTEM image, (g) SAED pattern and (h) elemental mapping of ZIS-2.

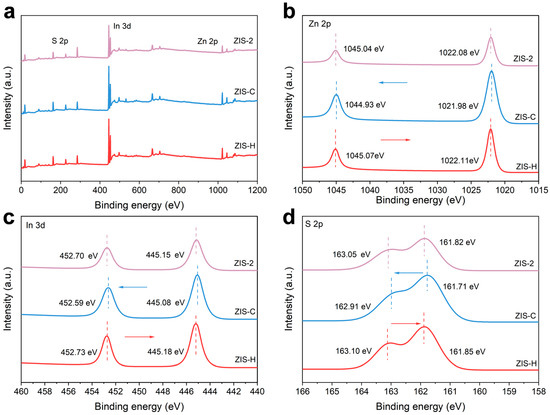

To determine the elemental composition and surface chemical states of the heterojunction, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed. The XPS survey spectrum presented in Figure 3a confirmed the presence of Zn, In and S in the sample. In Figure 3b, the characteristic double peaks of ZIS-H at 1045.07 eV and 1022.11 eV were assigned to Zn 2p1/2 and Zn 2p3/2, respectively. As shown in the high-resolution XPS spectrum of Figure 3c, the peaks at 452.73 eV and 445.18 eV were attribu ted to In 3d3/2 and In 3d5/2, respectively. In contrast, the peaks at 163.10 eV and 161.85 eV corresponded to S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2, respectively (Figure 3d). Compared with ZIS-H and ZIS-C, the characteristic peaks of Zn 2p, In 3d, and S 2p for ZIS-2 shifted toward lower and higher binding energies, respectively. Since binding energy reflects the electron density, these shifts indicated that the electron concentration of ZIS-2 increased and decreased relative to that of ZIS-H and ZIS-C, respectively. Therefore, the variations in binding energy were attributed to the directional electron transfer from ZIS-H to ZIS-C, which was induced by the formation of the hexagonal/cubic heterojunction.

Figure 3.

(a) XPS survey spectra and the high resolution XPS spectra of (b) Zn 2p, (c) In 3d, and (d) S 2p (The arrow and dotted line represent the changing trend and peak position, respectively).

2.2. Optical Properties and Photocatalytic Performances of the Catalysts

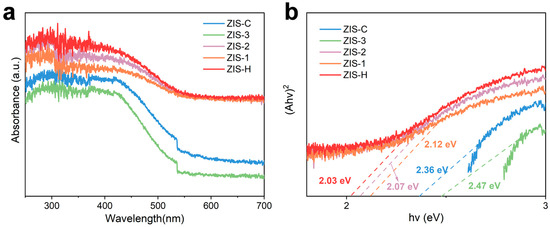

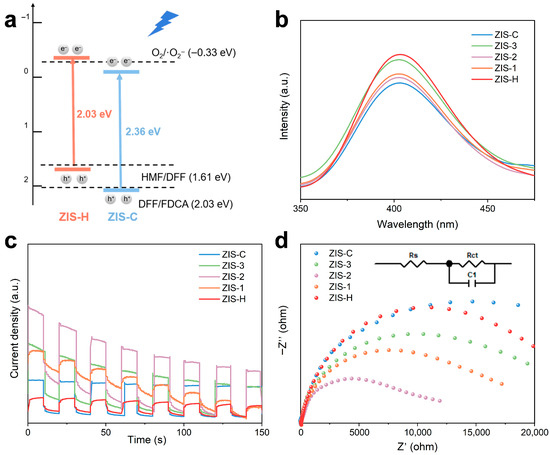

Figure 4a shows the UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-Vis DRS) spectra of ZIS. All samples exhibited strong light absorption in the 300–500 nm range, corresponding to the intrinsic light absorption of ZIS; the absorption intensity of ZIS-2 was enhanced compared to that of ZIS-H after compounding. In addition, the optical band gap (Eg) of the materials was determined via Tauc plot analysis based on UV-Vis DRS data. As shown in Figure 4b, the band gap of hexagonal ZIS-H was 2.03 eV, while that of cubic ZIS-C is 2.36 eV. The band gap difference between them originated from the distinct crystal structures, which also served as the basis for constructing the heterostructure between ZIS-H and ZIS-C. In addition, the optical band gaps of ZIS-1, ZIS-2, and ZIS-3 were also determined, with values of 2.07 eV, 2.12 eV, and 2.47 eV, respectively. Among them, ZIS-2 exhibited a moderate band gap, which not only retained the redox capability of the photocatalyst, but also enhanced its visible-light absorption efficiency (Figure 4b). The Mott-Schottky curves (Figures S6 and S7) were used to determine the flat-band potential. The potential of ZIS-H was −0.17 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), and that of ZIS-C was −0.09 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). The positive slope indicated that they were n-type semiconductors. The conduction band (CB) position was generally 0.20 V more negative than the flat-band potential; thus, the CB positions of ZIS-H and ZIS-C were calculated as −0.37 V and −0.29 V, respectively. Combined with the band gap data, the valence band (VB) positions of these materials were derived as 1.66 V and 2.07 V, respectively, which allowed the clarification of the band alignment at the heterostructure interface (Figure 5a).

Figure 4.

(a) UV–Vis spectra of ZIS-H, ZIS-C and ZIS composites. (b) Band gap of ZIS-H, ZIS-C and ZIS composites by Tauc plot.

Figure 5.

(a) Band structures of ZIS-2. (b) PL spectra, (c) Transient photocurrent responses, and (d) EIS spectra of ZIS-H, ZIS-C and ZIS composites.

Figure 5b depicted the photoluminescence (PL) spectra of ZIS-based materials, where the characteristic emission peak was centered around 400 nm, corresponding to the intrinsic radiative recombination signal of photoinduced electron-hole pairs in the materials. The PL peak intensity served as a critical indicator of carrier recombination efficiency. A lower peak intensity implied a reduced probability of radiative recombination and a higher separation efficiency of photoinduced carriers. As observed from the spectra, the pure-phase sample ZIS-H exhibited a relatively high PL peak intensity, suggesting severe recombination of its photoinduced carriers. In contrast, the PL peak intensities of the composite samples (ZIS-1, ZIS-2, ZIS-3) derived from ZIS-H and ZIS-C were significantly diminished, with ZIS-2 showing the lowest peak intensity, indicated that crystal phase hybridization can effectively suppress the radiative recombination process of carriers. Figure 5c presented the transient photocurrent response curves of ZIS, which reflected the separation and migration efficiency of photoinduced carriers: a higher photocurrent density and better response stability indicated superior carrier separation/transport performance. As observed from the figure, the pure-phase samples ZIS-H and ZIS-C exhibited significantly lower photocurrent densities with large response fluctuations, suggesting that their photoinduced carriers tend to recombine and poor separation efficiency. In contrast, the composite samples of ZIS-H and ZIS-C showed a noticeable enhancement in photocurrent density, with a gradient variation regulated by the composite ratio. Among them, ZIS-2 demonstrated the optimal photocurrent response. Figure 5d showed the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots of ZIS-based materials. The pure-phase samples ZIS-H and ZIS-C exhibited significantly larger semicircle radii, indicating severe hindrance in their interfacial charge transfer processes. Meanwhile, an R-C equivalent circuit model was adopted for fitting to quantify the charge transfer resistance (Rct). The fitted Rct values of ZIS-H and ZIS-C were 14,518 Ω and 13,816 Ω, respectively, while that of the ZIS-2 composite was significantly reduced to 5825 Ω (Table S4). A lower Rct value indicated a more efficient charge transfer process, which was consistent with the characterization findings from transient photocurrent and PL spectroscopy, further confirming that heterostructure could effectively reduce interfacial charge transfer resistance and accelerate the interfacial transport of photoinduced carriers.

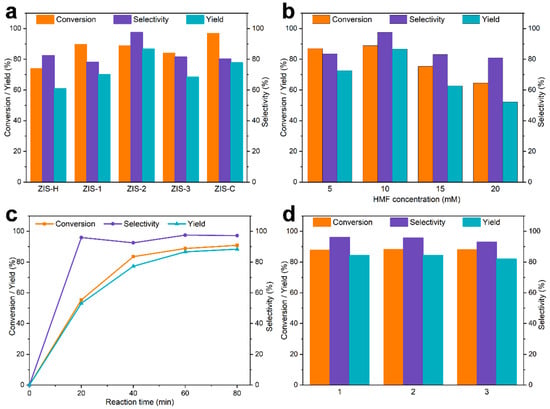

As shown in Figure 6a, different ZIS materials exhibited distinct activities toward the photocatalytic oxidation of HMF. ZIS-C delivered the highest HMF conversion efficiency but with poor selectivity, whereas ZIS-H showed higher selectivity than ZIS-C but lower conversion efficiency. After heterojunction construction, a balance between selectivity and conversion was achieved, with ZIS-2 exhibiting the optimal catalytic performance. As shown in Figure S9, the catalytic performance improved with an increase in catalyst loading. When the loading exceeded 8 g/L, a further increase in catalyst loading only slightly enhanced the HMF conversion, while the DFF selectivity decreased. Therefore, appropriately increasing the catalyst dosage can increase the number of active sites in the reaction system and enhance the reaction performance; however, an excess of the catalyst will shield a large number of available active sites. The influence of solvents was investigated in Figure S10, where the best results were obtained in acetonitrile (ACN), mainly attributed to its weaker electron-withdrawing ability compared with water. Subsequently, various light sources were evaluated (Figure S11), and blue LED light was verified as the most effective one. In addition, Figure 6b shows that the DFF yield decreased with either the increase or decrease in HMF concentration. This decline could be ascribed to the limitation of oxygen mass transfer, which triggered the occurrence of side reactions [35]. The time-course curves in Figure 6c indicated that the reaction achieved a high conversion rate of 88.8% and DFF selectivity of 97.5% within 60 min, and the yield was only slightly improved with the extension of reaction time. By fitting the oxidation reaction data of HMF to a pseudo-first-order kinetic model, the apparent rate constant (Kapp) was calculated [44]. Figure S13 shows that the apparent rate constant (k = −ln(C/C0)) of ZIS-2 is 0.0377 min−1. In the absence of a catalyst or light irradiation, the reaction activity was negligible. Under a nitrogen atmosphere, the catalyst cannot generate sufficient reactive oxygen species, and the oxidation reaction was solely driven by photogenerated holes, thus leading to a decrease in both HMF conversion and DFF selectivity (Table S1). As presented in Figure 6d, the catalytic activity of the as-prepared catalyst exhibited almost no change after multiple reaction cycles. In addition, the stability of the photocatalyst was further investigated via XRD and SEM analysis (Figures S16 and S17). There was no significant difference in the XRD patterns before and after the reaction. Additionally, the SEM morphology also remained unchanged. Therefore, the catalyst demonstrated excellent structural stability and reusability.

Figure 6.

Influence of (a) catalysts [HMF (10 mM, 5 mL), catalyst (40 mg), time (1 h), air, and LED light (10 W)], (b) HMF concentration [HMF (5 mL), catalyst (ZIS-2, 40 mg), time (1 h), air, and LED light (10 W)], and (c) reaction time [HMF (10 mM, 5 mL), catalyst (ZIS-2, 40 mg), air, and LED light (10 W)]. (d) Recyclability of ZIS-2 [HMF (10 mM, 5 mL), catalyst (ZIS-2, 40 mg), time (1 h), air, and LED light (10 W)].

2.3. Photocatalytic Mechanism

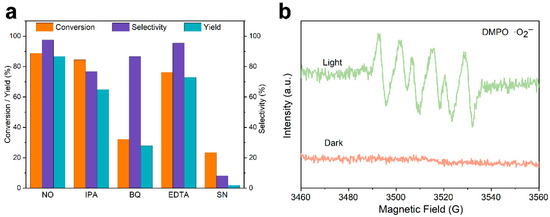

Figure 7a presented the active species trapping experiment, where isopropyl alcohol (IPA), benzoquinone (BQ), ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), and silver nitrate (SN) were introduced as quenchers for hydroxyl radicals (·OH), superoxide radicals (·O2−), holes (h+), and electrons (e−), respectively. It can be concluded that the addition of the superoxide radical quencher led to a significant decrease in conversion and yield, indicating that superoxide radicals are the core species of the reaction. Holes and hydroxyl radicals also caused a certain degree of reduction, suggesting their participation in the reaction process. Electrons functioned to reduce oxygen to superoxide radicals; thus, electron quenching also resulted in a decline in performance.

Figure 7.

(a) Active species trapping experiments. (b) EPR spectra of DMPO-O2− adduct.

The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spin-trapping experiment (Figure 7b) was conducted to detect reactive oxygen species generated during photocatalysis (the target species here is the superoxide radical (·O2−), with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as the trapping agent). As shown in the figure, no obvious characteristic signal was observed in the dark, while the characteristic six-line signal of DMPO–·O2− appeared under light irradiation, indicating that the ZIS heterostructure could effectively activate oxygen to generate superoxide radicals in the presence of light.

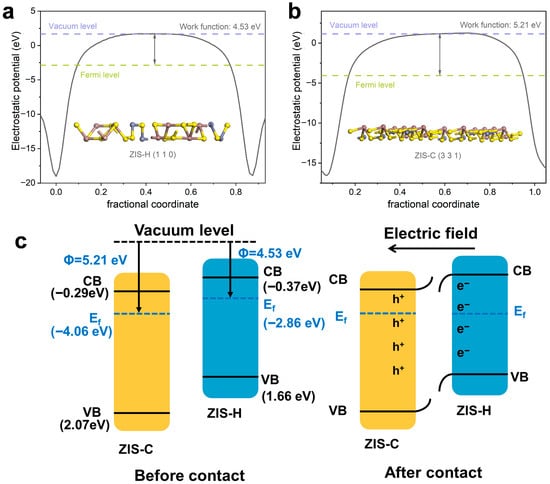

The surface work functions of ZIS-H and ZIS-C were calculated to be 4.53 eV and 5.21 eV, respectively, with the aid of density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Figure 8a,b). The charge transfer direction was from ZIS-H to ZIS-C, since charge migration followed the principle of transferring from materials with lower work functions to those with higher work functions until the Fermi levels reach equilibrium. As shown in Figure 8c, when ZIS-H came into contact with ZIS-C, the energy bands of ZIS-H bent downward while those of ZIS-C bent upward under the effect of the built-in electric field, a phenomenon that facilitated spatial charge separation and the construction of active sites [37].

Figure 8.

The surface work function of ZIS-H (a) and ZIS-C (b). (c) The electric field and ZIS-H and ZIS-C before and after contact.

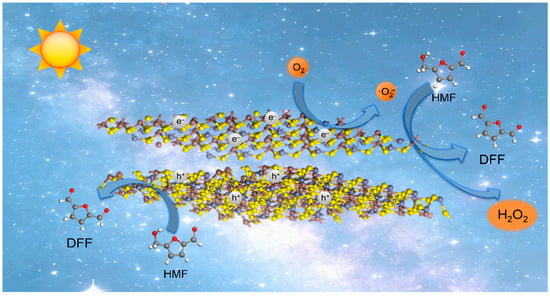

Based on the above-mentioned results, a mechanism was illustrated in Figure 9. Specifically, the band structures of ZIS-H and ZIS-C formed a Type-II heterojunction, which facilitated the transfer of electrons to the cubic phase and holes to the hexagonal phase under visible light irradiation. The photogenerated electrons reduced oxygen to produce superoxide radicals (·O2−), and the generated ·O2− reacted with HMF to generate DFF with the formation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, Figure S14).

Figure 9.

Proposed mechanism for the photocatalytic oxidation of HMF to DFF by ZIS-H/ZIS-C.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Cadmium nitrate tetrahydrate (Zn(NO3)2⋅6H2O, 99%), indium nitrate tetrahydrate (In(NO3)3⋅4H2O, 99.9%), zinc chloride (ZnCl2, 99%), indium chloride tetrahydrate (InCl3·4H2O, 99%), and thioacetamide (TAA, 99%) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF, 99%), 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF, 98%) and acetonitrile (CH3CN, 99%) were supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China.

3.2. Synthesis of Photocatalysts

For the preparation of ZIS-C, Zn(NO3)2⋅6H2O (0.30 g), In(NO3)3⋅4H2O (0.60 g), and TAA (0.45 g) were sequentially added into 50 mL of ethanol–water solution (volume ratio 1:1). After stirring for 30 min, the resulting mixture was transferred into a 100 mL Teflon lined stainless steel autoclave, heated to 160 °C, and maintained for 10 h. After cooling to room temperature, the product was washed several times with ethanol and dried at 60 °C overnight. The obtained sample was denoted as ZIS-C.

For the preparation of ZIS-H, ZnCl2 (0.14 g), InCl3·4H2O (0.59 g), and TAA (0.45 g) were added into 50 mL of ethanol–water solution (volume ratio 1:1) and stirred for 30 min. The mixture was then transferred into a 100 mL Teflon lined stainless steel autoclave, heated to 160 °C for 10 h, cooled to room temperature, washed repeatedly with ethanol, and dried at 60 °C overnight. The resulting sample was labeled as ZIS-H.

For the synthesis of ZIS-1, ZIS-2, and ZIS-3, ZnCl2 (0.14 g), InCl3·4H2O (0.59 g), TAA (0.45 g), and a certain amount of ZIS-C were dispersed in 50 mL of ethanol–water solution (volume ratio 1:1), followed by stirring for 30 min. The mixture was transferred into a 100 mL Teflon lined stainless steel autoclave, heated to 160 °C for 10 h, then cooled, washed with ethanol, and dried at 60 °C overnight. The samples obtained with hexagonal/cubic mass ratios of 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 were designated as ZIS-1, ZIS-2, and ZIS-3, respectively (as illustrated in Scheme S1).

3.3. Characterization of Photocatalysts

Multiple complementary analytical techniques were employed to conduct a thorough characterization of the catalysts in terms of their structural and physicochemical properties. XRD measurements, performed on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany)with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), were employed to analyze the crystal phase composition of the samples across a 2θ scanning range of 10–80°. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption measurements were performed on a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA) to evaluate the specific surface area and porosity of the catalysts. The BET method was applied for specific surface area calculation, and the BJH model was used to analyze the pore structure parameters. Both the surface morphology and crystal structure of the samples were comprehensively characterized via a Hitachi SU8010 SEM (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and a JEOL JEM-2100F TEM (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). A Thermo Scientific Nexsa XPS (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), equipped with Al Kα excitation source, was utilized to investigate the chemical states of the catalyst surface. To assess the light absorption capacity and charge carrier recombination tendency of the as-synthesized catalysts separately, UV-Vis DRS measurements were carried out on a Shimadzu UV-2600 (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) spectrophotometer, while PL spectroscopy analyses were performed using a Hitachi F-4600 (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) fluorescence spectrophotometer. A CHI760E electrochemical workstation manufactured by Chenhua Instruments (Shanghai, China) was adopted to perform a series of photoelectrochemical characterizations, namely photocurrent response and EIS tests, all operated under a standard three-electrode configuration. Reactive oxygen species formed during photocatalysis were identified via EPR spectroscopy on a Bruker E500-9.5/12 (Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) X-band system, with DMPO employed as the spin-trapping agent throughout the testing process.

3.4. Photocatalytic Activity Measurement

The photocatalytic oxidation reactions were carried out in a quartz photoreaction tube using an RLH-18 parallel photoreactor (Beijing Nuozhi Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), with irradiation provided by a blue LED light (10 W, 455 nm). In a typical run, adding 5 mL of 10 mM HMF solution to form a homogeneous solution through stirring. Subsequently, 40 mg of catalyst was added to the solution, the resulting mixture was sonicated for 10 min and then stirred in the dark for 30 min at the speed of 600 rpm to satisfy thermodynamic equilibrium. The system was proceeded under stirring at 25 °C for an indicated reaction time. After the reaction was completed, the suspension was subjected to centrifugation. Afterward, the reactants and products were analyzed on a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, LC-20AD, Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a diode array detector. The resulting compounds were separated by a C18AQ column with a mobile phase consisting of 70% acetonitrile and 30% ultra-pure water at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The conversion of HMF, the selectivity, and the yield of DFF were calculated according to the following Equations (1)–(3):

where is the initial concentration of HMF, and and are the concentrations of HMF and DFF, respectively, after the reaction.

4. Conclusions

In this study, hexagonal microsphere/cubic particle ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) catalysts with different mass ratios were prepared for the photocatalytic oxidation of HMF to DFF. Characterizations including PL spectroscopy, transient photocurrent response measurements, and EIS confirmed that the heterojunctions constructed by combining hexagonal and cubic ZIS effectively promoted the separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. Under mild reaction conditions (air atmosphere and irradiation with a 10 W blue LED at 455 nm), the optimal catalyst with a hexagonal/cubic ZIS mass ratio of 1:1 achieved an HMF conversion rate of 88.8% and a DFF selectivity of 97.5%, which outperformed most reported catalytic systems for HMF oxidation. Radical trapping experiments and EPR spectroscopy elucidated that superoxide radicals (·O2−) were responsible for the oxidative reaction. Combined with the charge transfer mechanism revealed by DFT calculations, the underlying reaction mechanism was clarified. This work successfully constructed a Type-II ZIS heterojunction, providing valuable insights for the expansion of hexagonal/cubic ZIS heterojunctions into the field of photocatalytic biomass valorization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16010069/s1, Scheme S1: Illustration of the preparation of ZIS composite; Figure S1: HPLC analysis of HMF and DFF; Figure S2: Standard curve of HMF; Figure S3: Standard curve of DFF; Figure S4: Pore size distribution plots of ZIS-H, ZIS-C, and ZIS-2; Figure S5: Different magnification SEM images of ZIS-H (a and d), ZIS-C (b and e), and ZIS-2 (c and f). Size distribution of the ZIS-H (g), ZIS-C (h), and ZIS-2 (i); Figure S6: Mott-Schottky curves of ZIS-H; Figure S7: Mott-Schottky curves of ZIS-C; Figure S8: Dark reaction of different catalysts; Figure S9: Influence of catalyst loading on photocatalytic oxidation of HMF; Figure S10: Influence of solvents on photocatalytic oxidation of HMF [HMF (10 mM, 5 mL), catalyst (ZIS-2, 40 mg), time (1 h), air, and LED light (10 W)]; Figure S11: Influence of wavelengths on photocatalytic oxidation of HMF [HMF (10 mM, 5 mL), catalyst (ZIS-2, 40 mg), time (1 h), air, and LED light (10 W)]; Figure S12: The point of zero charge (PZC) of ZIS-2; Figure S13: Apparent rate constants of the reaction; Figure S14: (a) UV–Vis spectra of H2O2 production. (b) The H2O2 production of different catalysts; Figure S15: (a) XPS survey spectra and the high resolution XPS spectra of (b) Zn 2p, (c) In 3d, (d) S 2p of ZIS-2 after the cyclic reaction; Figure S16: XRD diffraction patterns of ZIS-2 before and after the cyclic; Figure S17: SEM of ZIS-2 after the reaction; Figure S18: (a) Top view of photoreactor. (b) The distance from the light source to the bottom of the reaction tube. (c) Photo of the under blue LED. (d) Photo of the reaction tube; Table S1: Conversion of HMF to DFF using ZIS-2 catalyst under varied conditions; Table S2: Specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size of ZIS-H, ZIS-C and ZIS-2; Table S3: Technical specifications of the RLH-18 parallel photoreactor; Table S4: Equivalent circuit fitting parameters of ZIS-H, ZIS-C, and ZIS composites; Table S5: Comparative of photocatalytic HMF-to-DFF conversion in recent studies. Refs. [45,46,47,48,49,50] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-Y.J. and Z.-L.S.; methodology, Z.-L.S., W.-Y.L. and J.-B.Y.; software, B.T. and L.X.; validation, F.W., J.-B.Y. and K.-L.C.; formal analysis, W.-Y.L.; investigation, Z.-L.S. and W.-Y.L.; resources, L.-Y.J. and S.-S.L.; data curation, F.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.-L.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.-L.S., L.-Y.J. and S.-S.L.; visualization, Z.-L.S.; supervision, L.-Y.J. and S.-S.L.; project administration, L.-Y.J. and B.T.; funding acquisition, L.-Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC: 22279102) and Xi’an Science and Technology Plan Project (Academic and Research Institution Personnel Servicing Enterprises Project) (25GXKJRC00076).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the Supplementary Information.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC: 22279102) and Xi’an Science and Technology Plan Project (Academic and Research Institution Personnel Servicing Enterprises Project) (25GXKJRC00076) for their financial support. In addition, numerical computations were performed on computing center in Xi’an.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aramendia, E.; Brockway, P.E.; Taylor, P.G.; Norman, J.B.; Heun, M.K.; Marshall, Z. Estimation of useful-stage energy returns on investment for fossil fuels and implications for renewable energy systems. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Park, H.; Lee, C.W.; Kim, H.; Jeong, J.H.; Yun, J.I.; Bang, S.-U.; Heo, J.; Ahn, K.H.; Cha, G.D.; et al. Polymeric stabilization at the gas–liquid interface for durable solar hydrogen production from plastic waste. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarczyk, J.K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Polavarapu, L.; Feldmann, J. Challenges and Prospects in Solar Water Splitting and CO2 Reduction with Inorganic and Hybrid Nanostructures. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 3602–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouri, S.; Stylianou, K.C. Dual-Functional Photocatalysis for Simultaneous Hydrogen Production and Oxidation of Organic Substances. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 4247–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, P.; Fang, N.; Ding, S.; Ling, W.; Zhang, Q.; Chu, Y.; Ding, L. In-situ encapsulated CeO2 and doped Al in meso-ZSM-5 for efficient catalytic combustion of o-dichlorobenzene. App. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 358, 124412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Jiang, W.; Cao, Y.; Lei, J.; Ma, X.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, C.; Chen, H.; Lu, Z.; et al. Self-Adaptive Partially Oxidised W-Based Quantum Dots With Asymmetric BiS1O4 as Axial Polarisation Center for Enhanced Photocatalysis. cMat 2025, 2, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, D.; Long, R.; Xiong, Y. Highly efficient electrocatalytic biomass valorization over a perovskite-derived nickel phosphide catalyst. Nanoscale Horiz. 2023, 8, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Dong, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Jiao, L. Ionic Liquids Controlled Switchable Synthesis of Diverse Bio-Based N-Heterocycles via Tandem Dehydrogenative Cyclization. Acta Chim. Sin. 2025, 83, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, W.-Y.; Dong, W.; Wang, C.; Jiao, L.-Y. A supported Fe/Ru catalyzed three-component relay reaction through hydrogen borrowing strategy: Conversion of crude α-hydroxy acids into valuable N-heterocycles. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 2293–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Jiao, L.-Y. Ionic Liquid–Catalyzed Annulation of Biomass-Derived Alkyl Lactates: Time-Dependent Tunable Synthesis of Bioactive Dihydroquinoxalines and Quinoxalines. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 16661–16670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Duan, H. Opportunities and future directions for photocatalytic biomass conversion to value-added chemicals. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Guo, X.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, X. One-pot conversion of cellulose to HMF under mild conditions through decrystallization and dehydration in dimethyl sulfoxide/tetraethylammonium chloride. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Qiu, W.; Ayaz, S.; Long, J.; Guo, W.; Zhao, L.; Xi, Z. Aerobic Oxidation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural to 2.;5-Furandicarboxylic Acid over a Bi-Promoted Pt/Al2O3 Catalyst. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-N.; Li, Q.; Yan, Y.; Shi, J.-W.; Zhou, J.; Lu, M.; Zhang, M.; Ding, H.-M.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.-L.; et al. Covalent-Bonding Oxidation Group and Titanium Cluster to Synthesize a Porous Crystalline Catalyst for Selective Photo-Oxidation Biomass Valorization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202209289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, R.; Zhang, J.; Mao, J.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Synergistic Modulation of the Separation of Photo-Generated Carriers via Engineering of Dual Atomic Sites for Promoting Photocatalytic Performance. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Huang, Y.; Bai, H.; Li, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Fan, W.; Shi, W. Adsorption–Activation Bifunctional Center of Al/Co-Base Catalyst for Boosting 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Oxidation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2402789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Luo, L.; Chen, T.; Deng, L.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Shen, L.; Yang, M.-Q. Visible-light-driven anaerobic oxidative upgrading of biomass-derived HMF for co-production of DFF and H2 over a 1D Cd0.7Zn0.3S/NiSe2 Schottky junction. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2745–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Hou, L.; Gosset, J.; Wang, H.; Leng, S.; Boumghar, Y.; Barghi, S.; Xu, C. Recent advances in processes and technologies for production of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and 2,5-furandicarboylic acid from carbohydrates. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Deng, T.; Chen, C.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, X. Graphene Oxide: A Convenient Metal-Free Carbocatalyst for Facilitating Aerobic Oxidation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-Diformylfuran. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5636–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Akdim, O.; Douthwaite, M.; Wang, K.; Zhao, L.; Lewis, R.J.; Pattisson, S.; Daniel, I.T.; Miedziak, P.J.; Shaw, G.; et al. Au–Pd separation enhances bimetallic catalysis of alcohol oxidation. Nature 2022, 603, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Dong, C.-L.; Huang, Y.-C.; Zou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; He, N.; Shi, J.; Wang, S. Identifying the Geometric Site Dependence of Spinel Oxides for the Electrooxidation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 19215–19221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-L.; Qi, M.-Y.; Tang, Z.-R.; Xu, Y.-J. Cocatalyst decorated ZnIn2S4 composites for cooperative alcohol conversion and H2 evolution. App. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2021, 298, 120541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Huang, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; He, C.; Ren, X.; Zhang, P.; Mi, H. Suppressing Defects-Induced Non-Radiative Recombination for Activating the Near-Infrared Photoactivity of Red Polymeric Carbon Nitride. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2305935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, C.; Yang, S. Facile Synthesis of Ni3S2/ZnIn2S4 Photocatalysts for Benzyl Alcohol Splitting: A Pathway to Sustainable Hydrogen and Benzaldehyde. Catalysts 2025, 15, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Sun, Q.; Yu, L. Design and Preparation of ZnIn2S4/g-C3N4 Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Enhanced Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Catalysts 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, L.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Guan, R.; Zeng, G. Recent advances in synthesis, modification and photocatalytic applications of micro/nano-structured zinc indium sulfide. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, J.; Huang, Z.; Pan, G.; Xie, B.; Ni, Z.; Xia, S. Construction dual vacancies to regulate the energy band structure of ZnIn2S4 for enhanced visible light-driven photodegradation of 4-NP. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Ye, X.; Meng, S.; Fu, X.; Chen, S. Effect of different solvent on the photocatalytic activity of ZnIn2S4 for selective oxidation of aromatic alcohols to aromatic aldehydes under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 384, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, S.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; Ding, H.; Chen, D.; Ao, W. A review: Synthesis, modification and photocatalytic applications of ZnIn2S4. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 78, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, W.; Tian, G.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, H.; Fu, H. Cubic quantum dot/hexagonal microsphere ZnIn2S4 heterophase junctions for exceptional visible-light-driven photocatalytic H2 evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017, 5, 8451–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, X.; Li, H. A Review and Recent Developments in Full-Spectrum Photocatalysis using ZnIn2S4-Based Photocatalysts. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, W.; Ye, J.; Zhang, R.; Shao, Y.; Rangappa, A.P.; Zhao, J. In-situ self-assembly of ZnIn2S4/CuO heterojunctions for efficient photocatalytic oxidation of HMF to DFF in aqueous media. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Pan, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, C.; Yu, F.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, Y. Perylene imide supermolecule promote oxygen to superoxide radical for ultrafast photo-oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. App. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 340, 123217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; He, C.; Li, N.; Yang, S.; Du, Y.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Pan, X. Regio- and sequence-controlled conjugated topological oligomers and polymers via boronate-tag assisted solution-phase strategy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, W.; Chowdhury, A.; Putta, R.A.; Zhao, J. S-vacancy regulation over ultra-thin ZnIn2S4 for enhanced photocatalytic valorization of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Deng, W.; Tan, Y.; Shi, J.; Wu, J.; Lu, W.; Jia, J.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y. In Situ Topochemical Transformation of ZnIn2S4 for Efficient Photocatalytic Oxidation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-Diformylfuran. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, Y.; Wen, Y.; He, Y.; Sudarsanam, P.; Yang, S.; Li, H. Cooperative α-C–H activation enabled quantitative and partial photooxidation of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Green Energy Environ. 2025, 10, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Yin, X.; Gao, X.; Dong, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, C. Enhanced photocatalytic NO removal and toxic NO2 production inhibition over ZIF-8-derived ZnO nanoparticles with controllable amount of oxygen vacancies. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Bai, Y.; An, Q.; Xu, H.; Wu, F.; et al. Co-Construction of Sulfur Vacancies and Heterojunctions in Tungsten Disulfide to Induce Fast Electronic/Ionic Diffusion Kinetics for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2005802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-Y.; Luo, W.-Y.; Wen, F.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, Z.-L.; Ma, X.; Ding, M.; Jiao, L.-Y. Surface oxygen vacancies-engineered spherical bismuth molybdate: Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity for selective oxidation of benzylalcohol under ambient conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kong, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, F.; Lei, X. A Z-scheme ZnIn2S4/Nb2O5 nanocomposite: Constructed and used as an efficient bifunctional photocatalyst for H2 evolution and oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, L.; Xu, P.; Chang, Y.; Wu, C.; Fan, Z.; et al. Visible light driven highly selective oxidation of HMF coupled with H2 evolution via bimetal-doped synergism on ZnIn2S4 nanosheets. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 526, 171353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Meng, S.; Zhang, H.; Puente-Santiago, A.R.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Muñoz-Batista, M.J.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Weng, B. Tailoring Redox Active Sites with Dual-Interfacial Electric Fields for Concurrent Photocatalytic Biomass Valorization and H2 Production. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025; e13682, early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.; Remmani, R.; Bavasso, I.; Bracciale, M.P.; Palma, L.D. Biochar supported Fe–TiO2 composite for wastewater treatment: Solid-state synthesis and mechanistic insights. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 317, 122076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivtsov, I.; García-López, E.I.; Marcì, G.; Palmisano, L.; Amghouz, Z.; García, J.R.; Ordóñez, S.; Díaz, E. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural to 2,5-furandicarboxyaldehyde in aqueous suspension of g-C3N4. App. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 204, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Srivastava, R. Rose-like Bi2WO6 Nanostructure for Visible-Light-Assisted Oxidation of Lignocellulose-Derived 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and Vanillyl Alcohol. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 9080–9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Jin, Y.H.; Burgess, R.A.; Dickenson, N.E.; Cao, X.M.; Sun, Y. Visible-Light-Driven Valorization of Biomass Intermediates Integrated with H2 Production Catalyzed by Ultrathin Ni/CdS Nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15584–15587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Z.; Xue, Z.; Mu, T. Deep eutectic solvothermal NiS2/CdS synthesis for the visible-light-driven valorization of the biomass intermediate 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) integrated with H2 production. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2620–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Goepel, M.; Kubas, A.; Łomot, D.; Lisowski, W.; Lisovytskiy, D.; Nowicka, A.; Colmenares, J.C.; Gläser, R. Selective Oxidation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-Diformylfuran by Visible Light-Driven Photocatalysis over In Situ Substrate-Sensitized Titania. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, S.; Zhao, H.; Xiao, X.; Shen, Z. Development of multifunctional Co3O4-modified ZnIn2S4 photocatalyst for the selective oxidation of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 109, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.