Abstract

Methylbutynol (MB) is a typical propargylic alcohol with both alkynyl and hydroxyl groups, featuring excellent modifiability and broad applications. Currently, it is produced through the reaction of alkaline metallic acetylides and acetone, requiring expensive raw material and harsh reaction conditions. Herein, a novel method was proposed by replacing the metallic acetylide with calcium carbide (CaC2) as a low-cost industrial acetylide reagent. The effects of solvent, activator, and proton donor on the ball mill reaction, and the defoaming performance of the resultant MB and its oxidative coupling product (2,7-dimethyl-3,5-octadiyn-2,7-diol), were studied. Nucleophilic reactivity of CaC2 with acetone can be regulated by the activating effect of the ball mill, an appropriate activator, and a proton donor. High yield of MB (~94%) was obtained under synergistic action of TBAF·3H2O and acetylene, which represents a facile synthesis process of MB under mild conditions. MB exhibits good defoaming performance, and 2,7-dimethyl-3,5-octadiyn-2,7-diol is more promising, being an excellent non-ionic defoamer. The result is of great significance for exploring new chemical reactions of CaC2 and its high-value utilizations.

1. Introduction

Propargylic alcohols are typical multifunctional chemicals with terminal alkynyl and hydroxyl groups, showing good reactivity, chemical modifiability, and broad applications for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals and other functional materials. They are excellent non-ionic surfactant and steel corrosion inhibitor due to their amphiphilicity, good wetting, and defoaming properties [1,2]. Methylbutynol (MB) is an intermediate for the synthesis of isoprene, a monomer of synthetic rubber. Propargylic alcohols are currently produced via alkynylation of carbonyl compounds by metal acetylides, Grignard reagents or acetylene under basic conditions of liquid ammonia or KOH and low temperatures [3], which requires a higher raw material cost and is not suitable for large-scale production. The nucleophilic reaction of calcium carbide (CaC2) with aldehydes/ketones has ever been explored [4]. As early as 1952, Ray et al. [5] reported the reaction of CaC2 with acetone in KOH-diethyl ether solvent, yielding 33% of 2,5-dimethyl-3-hexyn-2,5-diol after a 33 h reaction at low temperatures (0–10 °C). Abolfazl et al. [6] used tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) to catalyze the reaction of CaC2 with some aldehydes/ketones, except acetone, in DMSO to synthesize propargylic alcohols (Scheme 1a). For ketones without active hydrogens, the aldol condensation can be suppressed. For example, when CaC2 and KOH were ball milled 30 min for activation, and then co-milled with benzophenone for 3 h, a yield of 41% propargyl diol and 25% propargylic alcohol was obtained (Scheme 1b) [7].

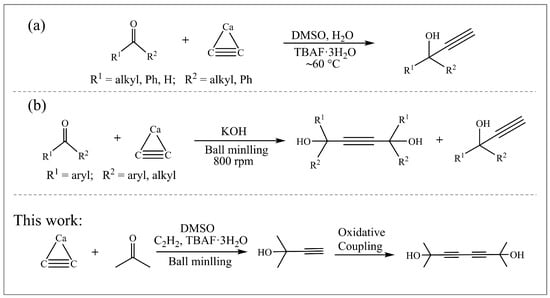

Scheme 1.

Synthesis pathways of propargylic alcohols using CaC2 as an acetylene source. (a) catalytic reaction of CaC2 by TBAF; (b) ball mill activation of CaC2 by KOH.

CaC2 is an important coal chemical product with an annual production of ca. 30 million tons. Furthermore, its manufacture from bio-coke is a greener process [8,9], which makes it a potential low-carbon chemical. Currently, CaC2 is primarily used as a source of acetylene for the production of various chemical products, such as vinyl chloride [10], acrylonitrile, acetylene black, and vinyl ethers [11,12,13]. The reactivity of its carbide anion (C22−) has received little attention and is worthy of further exploration. Therefore, developing new applications of CaC2 in organic synthesis and manufacturing its high-value derivatives is of great significance. Theoretically, CaC2 is an important industrial source of carbon anions and the cheapest metallic acetylide reagent, and its reaction potential with various reactants can be expected from a thermodynamic perspective [14]. Production of methylbutynol using CaC2 is more viable from techno-economic points of view, compared to that using expensive sodium acetylide or acetylene with minimal reactivity. However, the strong lattice energy of CaC2 makes it insoluble in all organic solvents, which greatly limits its availability and reactivity. Meanwhile, as a conjugated base of acetylene, its carbanion is of super-strong Lewis basicity, which may suppress its nucleophilic reactivity and give rise to an elimination reaction of the electrophiles. For instance, acetone condensation occurs easily at room temperature in the presence of CaC2, yielding various condensation products like isophorone and methyl-substituted aromatics, where CaC2 is functioned as a strong base and dehydrating agent rather than a nucleophilic reagent [15,16,17]. The aim of the present work is to investigate the nucleophilic reaction of CaC2 with acetone to produce MB, focused on its basicity regulation, solvent effects, and process intensification of the heterogeneous reaction. This work not only provides a facile synthesis method of MB but also provides insights for the development of new reactions of CaC2 toward its high-value applications.

2. Results

The reactivity of CaC2 is greatly limited by its insolubility, while mechanical grinding helps to destroy its crystallinity, and increase its chemical potential, interface mass transfer, availability of the acetylide anion and the reaction rate [18,19]. Its mechanochemical reaction has been used to prepare various CaC2-derived carbon materials [20,21,22,23]. Suitable solvents and additives can facilitate the dissolution of CaC2 and regulate its basicity and nucleophilic reactivity; thus, they are studied separately in the following sections.

2.1. Solvent Effect of the Reaction

Solvent has a profound influence on a reaction due to its regulation on the acidity/basicity of the reactants and the activation energy of the reaction via specific intermolecular interaction. And a suitable solvent is crucial for the nucleophilic reactivity of CaC2. Due to its super-strong basicity, CaC2 is apt to be protonated by protic solvents like water, methanol, and glycerol, forming acetylene in situ with little reactivity [20]. In contrast, polar aprotic solvents are suitable for nucleophilic reactions due to their strong solvation ability for CaC2 and chemical stability. Thus, aprotic polar solvents were studied here, i.e., dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), acetonitrile (CH3CN), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), and so on. As shown in Table 1, a nucleophilic reaction occurred in all solvents, and the highest yield was obtained in DMSO (31.8%), followed by Dimethylacetamide (DMAC) (25.9%), THF (Tetrahydrofuran) (22.4%), acetonitrile (19.0%), and DMF (16.2%). Thus, DMSO is chosen as a appropriate solvent for the reaction.

Table 1.

Effect of solvent on the reaction yield a.

The solvent effect arises from its interaction with reactants, products, catalysts, and transition states via H-bonding, complexation, electron transfer, and so on, affecting the reaction mechanism, activation energy, reaction rate, and selectivity. For the polar aprotic solvents, their positive charge is shielded inside the molecules, which decreased their electrostatic interaction with the carbanion and enhanced its nucleophilic reactivity. The high polarity helps to stabilize the charged transition states, lower the activation energy, and increase the reaction rate. Chen et al. studied the interaction of CaC2 with various solvents and its solvation energies using a SMD implicit solvent model. It was found that polar aprotic solvents show a stronger solvation effect and a weaker deprotonation ability, and DMSO has the greatest impact on the negative electrostatic potential of C22− [24]. Thus, DMSO can better modulate the basicity of the acetylide anion, stabilize the transition state, and lower the activation energy, which is consistent with the experimental observation.

2.2. Activation and Basicity Regulation of CaC2

Generally, CaC2 hardly reacts with organic compounds due to its high lattice energy and insolubility. Additionally, as a conjugated base of acetylene, C22− is of super basicity, which severely inhibits its nucleophilic reactivity. Benzophenone does not react with CaC2, but a high yield of propargylic alcohols can be obtained when they are ball milled with solid KOH [22]. This may be attributed to the partial protonation of CaC2 by KOH, resulting in a disrupted lattice structure and formation of monovalent anion of HC≡C−, which has lower basicity and better nucleophilic reactivity than the bivalent anion of C22−.

To adjust the reactivity of CaC2, the effect of some activators was studied, including those with active hydrogen (acetylene, water, TBAF·3H2O), Lewis acidity (MgCl2), and inorganic fluorides/carbonates (TBAF·3H2O, CsF, Et3N·HF, KF, Cs2CO3). As such, the basicity of CaC2 may be reduced by its partial protonation or Lewis acid–base pairing, and its nucleophilicity may be liberated indirectly via the strong affinity between calcium and the F−/CO32− ions. As shown in Table 2, both water and acetylene can make CaC2 protonated, forming corresponding propargylic alcohol. Water has a poor activation effect with only 3.2% of product yield. Acetylene, as a weaker proton donor, showed a better activation effect, and higher product yield (5.8%) was obtained when the reactants were ball milled for 4 h in acetylene-saturated DMSO solution. This is because the protonation of C22− by acetylene can be exactly controlled to C2H− via proton transfer reaction, i.e., CaC2 + C2H2 → Ca(C2H)2, without worry of over-protonation in water and some alcohols. Anhydrous MgCl2 can activate CaC2, yielding 9% propargylic alcohol. This may be ascribed to their Lewis acid–base interaction, forming a Grignard-like reagent via Schlenk Equilibrium [23,25], CaC2 + 2MgCl2→ClMgC≡CMgCl + CaCl2, thereby lowering the basicity of the acetylide anion and enhancing its nucleophilicity. Among the inorganic salts (CsF, KF, Cs2CO3) tested, only CsF showed a slight activation effect with 5.1% of product yield, which may be ascribed to its higher solubility in DMSO and a specific complexing effect with the carbonyl group of acetone [24]. The complexation of the cesium with the carbonyl oxygen increases the positive charge of the carbonyl carbon and its electrophilic reactivity. KF and Cs2CO3 showed little activation effect, likely due to their minimal solubility in DMSO and metathesis with CaC2 to form alkali metal carbides and corresponding CaF2 and CaCO3. The driving force of the metathesis reactions is the strong electrostatic affinity between calcium and fluoride/carbonate ions and the high formation energy of CaF2 and CaCO3. Among the activators studied, TBAF·3H2O is the best one, yielding 37.8% of propargylic alcohol, which may be attributed to its high solubility and the synergistic activation effects of the fluoride ion and crystal water. Quantum chemical calculations indicate that trace water can react with calcium carbide on its interface, forming ethynyl calcium hydroxide HOCaC≡CH, which significantly increases the solubility of the acetylide ion in DMSO and enhances its reactivity [26,27]. However, excessive water may cause rapid hydrolysis of calcium carbide, generating acetylene gas with little nucleophilicity.

Table 2.

Effect of activators on the reaction yield.

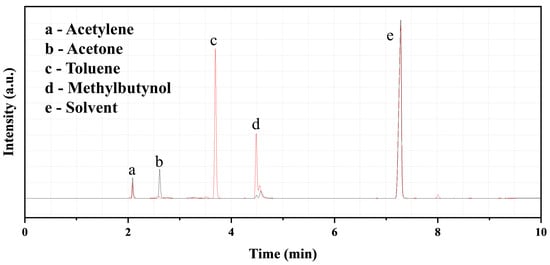

2.3. Effect of Reaction Time and Rotation Speed

The effect of reaction time on the product yield was explored under different conditions. As shown in Table 3, extending reaction time is conducive to the product yield. For example, the reaction with neat KF was very slow at the beginning with only 5.1% of MB yield in 3 h, but the yield rapidly increased to 35.4% at 6 h. This indicates that the reaction is controlled by mass transfer, and there exists an induction period. The slower initial rate is related to the larger particle size of CaC2 and the limited reactive interface and activation degree. TBAF·3H2O, with the dual effect of water and fluoride ions, showed a faster reaction rate, and the propargylic alcohol yield was increased from 31.8% to 56.0% as the reaction time prolonged from 3 h to 6 h and then levelled off. This is because, in the late stage, the concentration of CaC2 is low, and its surface was covered by the insoluble calcium alkoxide that further hinders its reaction. The product yield was 18.8% after a 9 h reaction in the presence of C2H2. When acetylene and TBAF·3H2O were used together, the effect was more significant, indicating their synergistic activation on CaC2. After a 3 h reaction in acetylene-saturated DMSO, the product yield was over 80.1%, which is much higher than the yields from using either TBAF·3H2O (31.8%) or acetylene (13.8%) alone. The low activity of the water in TBAF·3H2O helps to control the protonation degree of CaC2, along with the activation effect of its fluoride ions [6]. Additionally, CaC2 can be partially protonated by acetylene, forming calcium acetylide (CaC≡CH) with lower basicity and higher nucleophilicity. The compositions of the solution before and after the reaction in the presence of acetylene and TBAF·3H2O are compared in Figure 1. Obviously, acetone was converted almost completely after a 9 h reaction, and MB was formed with high selectivity (~100%). The influence of rotation speed on the reaction was also investigated under fixed other conditions (CaC2 20 mmol, acetone 10 mmol, C2H2-saturated DMSO 30 mL, TBAF·3H2O 20 mmol, ball mill 3 h). The MB yield at 150, 270, and 400 rpm was 74%, 80%, and 75%, respectively. Thus, the rotation speed has little influence on the reaction within the range of 150–400 rpm, and 270 rpm was used hereinafter.

Table 3.

Reactivity of CaC2 with acetone under different activators and reaction time.

Figure 1.

GC analysis for the liquid samples (Black—before reaction, Red—after reaction; Toluene serves as an internal standard).

2.4. Reaction Mechanism of CaC2 with Acetone

Acetylene (C2H2) is not only a H-donator, its nucleophilic addition with acetone is also possible under basic conditions to form methylbutynol. Herein, CaC2 and the companying CaO may be functioned as a strong base for deprotonation of acetylene, forming monovalent acetylide anion and then reacting with acetone. To explore this possibility, the reactions of acetylene with acetone in DMSO catalyzed by TBAF, CsF, CsOH, and CaO were investigated. As seen from Table 4, The reaction does not occur in the absence of a catalyst or in the presence of CsF only [28]. When TBAF or CaO were used alone, the product yield was 44.4% and 40.1%, respectively; when they were used together, the yield was enhanced to 55.2%. When industrial-grade calcium carbide (75% CaC2–25% CaO) and TBAF were used together, the yield was increased drastically to 84.4% (see Table 3 entry 15) after a 5 h reaction, which may be ascribed to the stronger basicity and deprotonation capacity of CaC2 than CaO for acetylene. Additionally, CsOH also showed a good catalytic effect, yielding 51.6% of MB products.

Table 4.

Effect of different additives on the reaction of acetylene with acetone and product yield a.

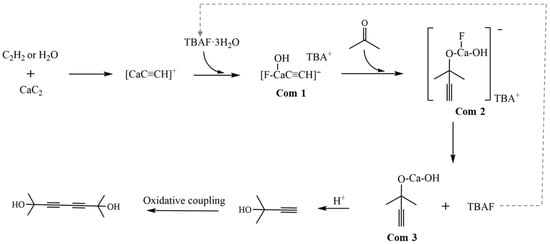

Based on the above analysis, the reaction mechanism of CaC2 with acetone was proposed, as shown in Scheme 2. Herein, CaC2 was protonated partially by C2H2 and/or H2O to form [CaC2H]+, which was further activated by TBAF·3H2O, forming TBA+[HOCaFC≡CH]− (Com 1) [29,30,31]. These processes significantly reduced the surface basicity of CaC2 (from C22− to C2H−), suppressed the condensation of acetone, and enhanced the nucleophilic reactivity of the acetylide ions. The acetylide ion of TBA+[HOCaF(C≡CH)]− reacted with acetone to yield Com 2, a calcium propargyl alcoholate complex. Upon rearrangement of Com 2, calcium propargyl alcoholate (Com 3) was formed along with the release of TBAF [6]. Calcium propargyl alcoholate was finally converted to MB via hydrolysis.

Scheme 2.

The catalysis of acetylene and TBAF·3H2O in reaction of CaC2 with acetone.

2.5. Scale-Up Experiment

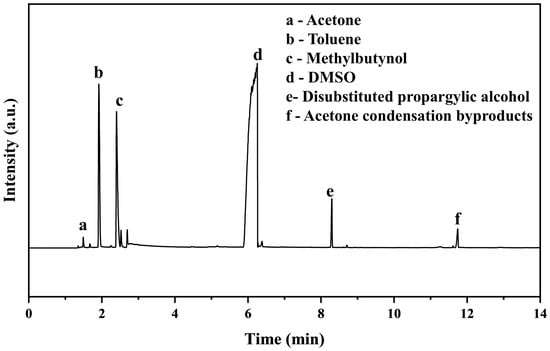

To examine the reproducibility of the reaction results, scale-up experiments were conducted in a stirred ball mill with larger amounts of reactants and solvent. To a 2 L stirred ball mill jar, 6 g of calcium carbide, 15 mL of acetone, 150 mL of acetylene-saturated DMSO, and 18 g of TBAF·3H2O were added sequentially and milled at 270 rpm for 4 h. The resulting slurry was treated with centrifugation, the supernatant was analyzed by GC, and the yield of MB was 94.3%. This indicates the reproducibility of the ball mill reaction and its viability for massive synthesis. When the ball milled reaction was conducted at 270 rpm for 9 h under the same other conditions, the acetone conversion and MB yield was 97.2% and 91.9%, respectively. The GC result for the solution sample after a 9 h reaction under the synergistic action of TBAF·3H2O and acetylene is presented in Figure 2. Obviously, acetone was virtually completely converted to the main products of MB and disubstituted propargylic alcohol, along with minor byproducts of acetone condensation.

Figure 2.

GC-MS analysis for the reaction at optimal conditions in presence of TBAF·3H2O and C2H2.

2.6. Defoaming Performance of Propargylic Alcohols

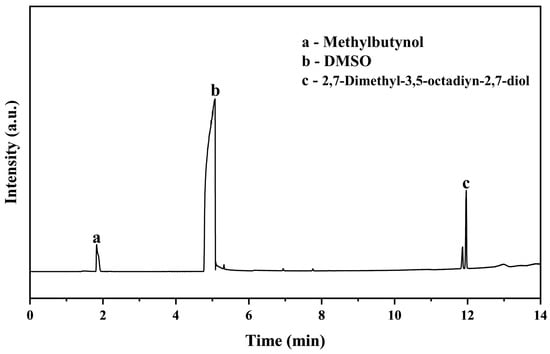

Alkynediols are widely used non-ionic defoamer, while the main product here is a mono-substituted methylbutynol, which was further converted to 2,7-dimethyl-3,5-octadiyn-2,7-diol via its oxidative coupling. For this, 4 mmol of methylbutynol, 60 mg of cuprous oxide, and 10 mL of DMSO were added to a stirred glass vial and reacted at 80 °C for 8 h under oxygen pressure of 0.03 MPa. The resulting solution was analyzed by GC. As shown in Figure 3, most of methylbutynol (1.83 min) was converted to 2,7-dimethyl-3,5-octadiyn-2,7-diol (11.9 min).

Figure 3.

GC chromograph of methylbutynol after 8 h oxygen oxidation at 80 °C in DMSO.

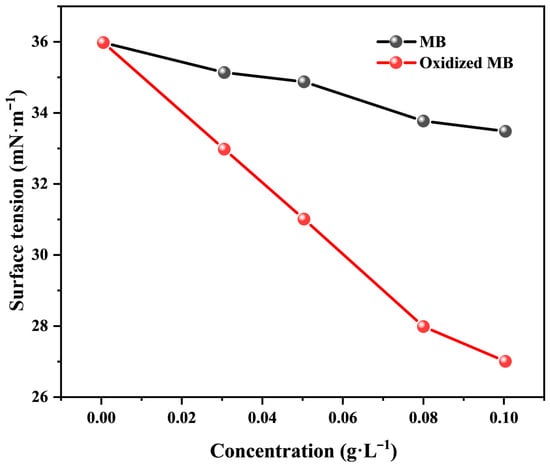

The defoaming rate of MB decreases significantly with its decreased usage from 10% to 3 wt%, as shown in Table 5. The defoaming performance of 2,7-dimethyl-3,5-octadiyn-2,7-diol is much better than that of MB, and complete deforming can be realized at 3% usage, which may be ascribed to its superhigh surface activity. For illustration, the surface tension of 0.5 wt% aqueous solution of sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (C12H25SO3Na) with varying content of MB or its oxidized product (0~0.1 g·L−1) was determined. As shown in Figure 4, MB can slightly reduce the surface tension of the C12H25SO3Na solution. In contrast, the surface activity of its oxidative coupling product is enhanced greatly, as shown from the drastically decreased surface tension from 36 to 27 mN·m−1 as its usage increased to 10%. This may be ascribed to the doubled length of the carbon chain and the number of alkynyl and hydroxyl groups of the oxidative coupling product of MB. The strong hydrophobicity and rigidity of the two alkynyl bonds impart a stronger hydrophobic–hydrophilic balance to the surface active molecule, making it more easily adsorbed at the gas–liquid interface, forming a closely packed monolayer. The synergistic effect of the longer carbon chain and multiple alkyne bonds further enhances its hydrophobicity.

Table 5.

Defoaming rate of methylbutynol and its oxidative coupling product at different usages.

Figure 4.

Surface tension of C12H25SO3Na solution (0.5 wt%) at different content of methylbutynol and its oxidized product.

3. Materials and Methods

The main instruments used in the experiments include planetary ball mill (QXQM-2, Tianchuang, Changsha, China), gas chromatograph (GC-2010, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (GC-MS, Agilent 7890A-5975C, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), precision electronic balance (ME204E, METTLER TOLEDO, Zurich, Switzerland), crusher (ZN-04BL, Zknc, Beijing, China), and nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (NMR, AV600, Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany).

The main chemicals used include calcium carbide (CaC2, 75%), cesium fluoride (CsF, 99%), tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF, 99%), triethylamine trihydrofluoride (TEA-3HF, 97%), and anhydrous magnesium chloride (MgCl2, 99.9%), purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, and acetylene (99.9999%) from Beijing Haipu Gas (Beijing, China). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.8%, water content 0.03%) and methylbutynol (98%) were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China) and used as received.

For the synthesis of MB, a certain amount of 400-mesh CaC2 powder, TBAF, acetone, and DMSO saturated with acetylene were added to the ball mill jar. The admixture was ball milled at room temperature and 270 rpm for a period of time and acidified to neutral by formic acid. The as-treated reaction slurry was separated via centrifugation, and the supernatant was sampled using a syringe with a microfiltration head and analyzed by GC. The GC analysis was made using an FFAP (30 × 0.53 × 1.0) column under the following conditions: high-purity nitrogen as carrier gas at 27.7 kPa with flow rate of 100 mL/min, split injection mode with split ratio 16.8:1, injection temperature 300 °C, oven initial temperature 60 °C, temperature held at 60 °C for 0.5 min and ramped at 20 °C/min to 240 °C, and FID detector at 300 °C. When the set temperature was reached and stabilized, 1 μL of the sample was injected and analyzed via internal standard method. The analysis was repeated three times, and the average value was taken as the experimental result.

4. Conclusions

The activation effect of solvent, activator, and ball milling on the reactivity of calcium carbide with acetone was studied for the preparation of propargylic alcohols, a non-ionic surfactant and deformer. Additives like CsF, TBAF, MgCl2, CsOH, water, and acetylene show certain activation effects on calcium carbide, but the propargylic alcohol yield is relatively low when they are used separately. However, 94.0% of product yield can be obtained when TBAF·3H2O and acetylene are used together. Their synergistic activation effect may be attributed to the protonation of calcium carbide by acetylene and crystal water of TBAF·3H2O, as well as the strong affinity between calcium and the fluoride ion of TBAF, forming fluoride-activated terminal acetylide intermediates with reduced basicity and enhanced nucleophilicity. Propargylic alcohol is a good defoamer, and its oxidative coupling product is better. This study is of great significance for the development of new reactions of calcium carbide and its high-value utilization.

Author Contributions

Z.Z.: conceptualization, investigation, data curation; H.X.: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; H.C.: formal analysis; H.M.: original draft; H.F.: writing—review and editing; Y.L.: funding acquisition, project administration; C.L.: funding acquisition, project administration, methodology, supervision; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22338002) and State Key Laboratory of Chemistry and Utilization of Carbon Based Energy Resources (Grant No. KFKT2022003).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MB | Methylbutynol |

| CaC2 | Calcium carbide |

| TBAF | Tetrabutylammonium fluoride |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| CH3CN | Acetonitrile |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| DMAC | Dimethylacetamide |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| GC | Gas chromatograph |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer |

| C12H25SO3Na | Sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate |

| CsF | Cesium fluoride |

| KF | Potassium fluoride |

| Cs2CO3 | Cesium carbonate |

| MgCl2 | Magnesium chloride |

References

- Li, G.L.; Fang, Y.H.; Wu, C.D.; Shao, Y.Z.; Guo, Y.Q.; Ma, X.X. Study on the development and performance of a new concrete antifoaming agent. Key Eng. Mater. 2021, 871, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainier, F.B.; da Silva, T.T.; de Araujo, F.P. Performance of propargyl alcohol as corrosion inhibitor for electroless nickel-phosphorus (NiP) coating in hydrochloric acid solution. J. New Mater. Electrochem. Syst. 2021, 24, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. Study on the synthesis and corrosion inhibition application of methylbutynol. Chem. World 1997, 05, 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sum, Y.N.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Y. Synthesis of acetylenic alcohols with calcium carbide as the acetylene source. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 2718–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, F.; Sawicki, E.; Borum, O. Correction. Diels-Alder reactions of maleimide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Seidel, D.; Miska, A.; Schreiner, P.R. Fluoride-assisted activation of calcium carbide: A simple method for the ethynylation of aldehydes and ketones. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2808–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardila-Fierro, K.J.; Bolm, C.; Hernández, J.G. Mechanosynthesis of odd-numbered tetraaryl [n] cumulenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12945–12949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Yu, D.; Sum, Y.N.; Zhang, Y. Synthesis of functional acetylene derivatives from calcium carbide. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.C.; Li, C.; Wu, W. Production of calcium carbide from fine biochars. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 122, 8658–8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Lu, Y.; Liang, X.; Li, C. The catalytic mechanism of [Bmim]Cl-transition metal catalysts for hydrochlorination of acetylene. Catalysts 2024, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, Y.; Gao, B.; Wu, W.; Jiang, H. Calcium carbide as the acetylide source: Transition-metal-free synthesis of substituted pyrazoles via [1,5]-sigmatropic rearrangements. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 6445–6449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schobert, H. Production of acetylene and acetylene-based chemicals from coal. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1743–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodygin, K.S.; Vikenteva, Y.A.; Ananikov, V.P. Calcium-based sustainable chemical technologies for total carbon recycling. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1483–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, F.B.; Montonna, R.E. The free energies of reactions of calcium carbide. J. Phys. Chem. 1941, 45, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q. One-pot synthesis of methyl-substituted benzenes and methyl-substituted naphthalenes from acetone and calcium carbide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 6226–6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Meng, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, C. Aldol condensation of refluxing acetone on CaC2 achieves efficient production of diacetone-alcohol, mesityl oxide and isophorone. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 30610–30615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Meng, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, C. Efficient catalysis of calcium carbide for the synthesis of isophorone from acetone. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 5257–5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.N.; Cheng, L.; Xu, X.B.; Meng, H.; Lu, Y.Z.; Li, C.X. Greatly enhanced reactivity of CaC2 with perchloro-hydrocarbons in a stirring ball mill for the manufacture of alkynyl carbon materials. Chem. Eng. Process 2018, 124, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zang, X.; Lu, Y.; Meng, H.; Li, C. Synthesis of propiolic and butynedioic acids via carboxylation of CaC2 by CO2 under mild conditions. Catalysts 2024, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Meng, H.; Li, C. Efficient destruction of hexachlorobenzene by calcium carbide through mechanochemical reaction in a planetary ball mill. Chemosphere 2017, 166, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Lu, Y.; Li, C. Preparation of C-MOx nanocomposite for efficient adsorption of heavy metal ions via mechanochemical reaction of CaC2 and transitional metal oxides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 393, 122487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiang, B.; Xu, S.; Gu, J.; He, X.; Li, C. Green synthesis of oxygenic graphyne with high electrochemical performance from efficient mechanochemical degradation of hazardous decabromodiphenyl ether. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 6190–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Meng, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, C. Mechanochemical synthesis of oxygenated alkynyl carbon materials with excellent Hg(II) adsorption performance from CaC2 and carbonates. Green Energy Environ. 2023, 8, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Song, H.; Xu, X.; Meng, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, C. Greener production process of anhydrous acetylene and calcium diglycerode via mechanical ball mill of calcium carbide and glycerol. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 9560–9565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, R.M.; Eisenstein, O.; Nova, A.; Cascella, M. How solvent dynamics controls the Schlenk equilibrium of Grignard reagents: A computational study of CH3MgCl in tetrahydrofuran. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 4226–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, H.; Zang, X.; Meng, H.; Fan, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, C. Experimental and molecular insights on the regulatory effects of solvent on CaC2 reaction activity. AIChE J. 2024, 70, e18511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Schreiner, P.R. Direct exploitation of the ethynyl moiety in calcium carbide through sealed ball milling. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 28, 4339–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Meng, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, C. Synthesis of 1-cyclohexenylacetonitrile using cyclohexanone and acetonitrile under synergetic activation of CaC2 and CsF. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2019, 38, 4971–4977. [Google Scholar]

- Hainer, A.S.; Lanterna, A.E.; Scaiano, J.C. Beyond acetylene: Exploring solvent stabilization of calcium carbide-derived acetylide intermediates and their significance in small organic molecule synthesis. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202400501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Sum, Y.N.; Ean, A.C.C.; Chin, M.P.; Zhang, Y. Acetylide ion (C22−) as a synthon to link electrophiles and nucleophiles: A simple method for enaminone synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5125–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polynski, M.V.; Sapova, M.D.; Ananikov, V.P. Understanding the solubilization of Ca acetylide with a new computational model for ionic pairs. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 13102–13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.