One-Pot Direct Synthesis of b-Axis-Oriented and Al-Rich ZSM-5 Catalyst via NH4NO3-Mediated Crystallization for CO2 Hydrogenation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Catalyst Preparation

2.2.1. Metal Catalyst

2.2.2. ZSM-5 Catalyst

2.3. Characterization Methods

2.4. Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

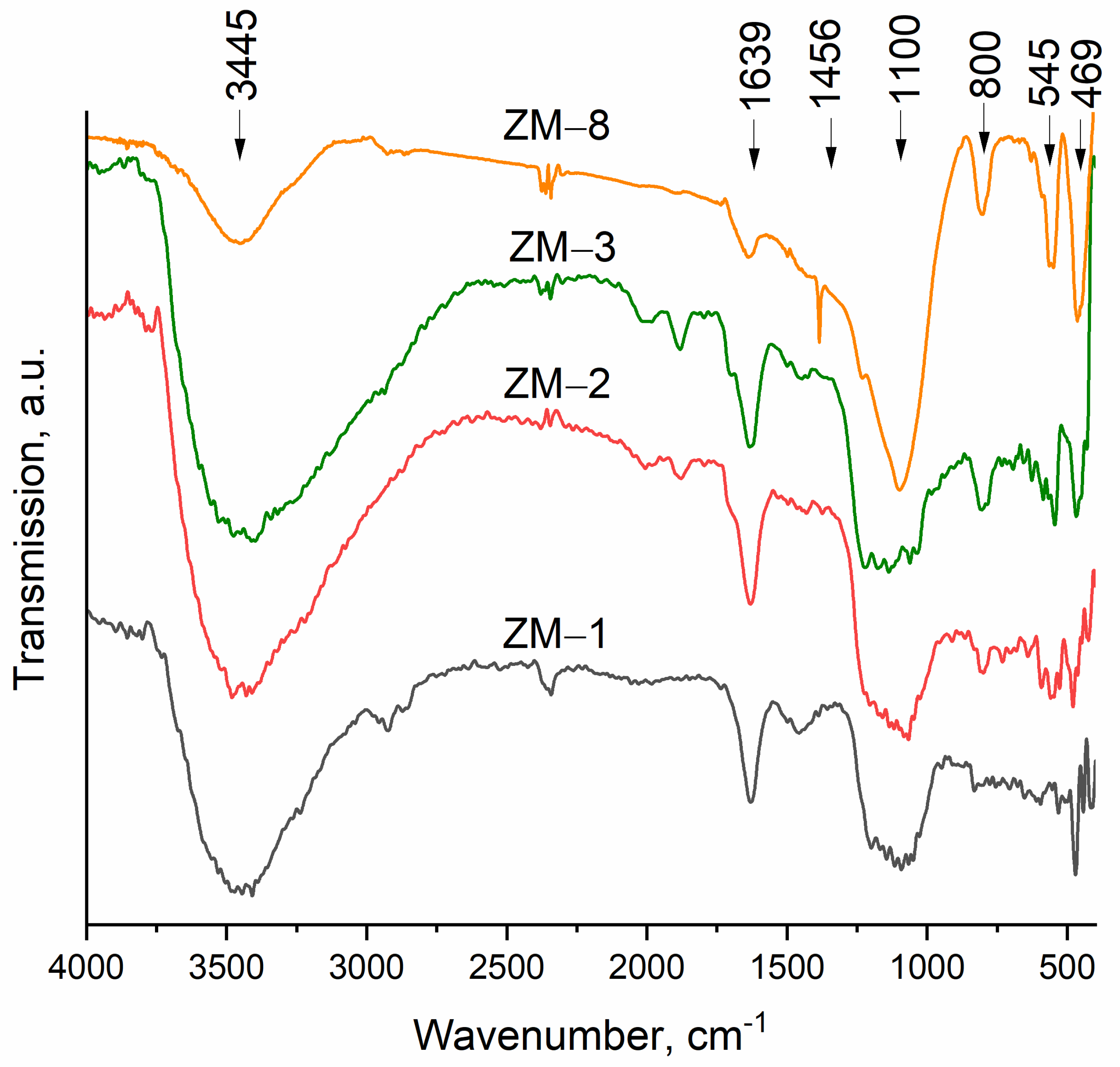

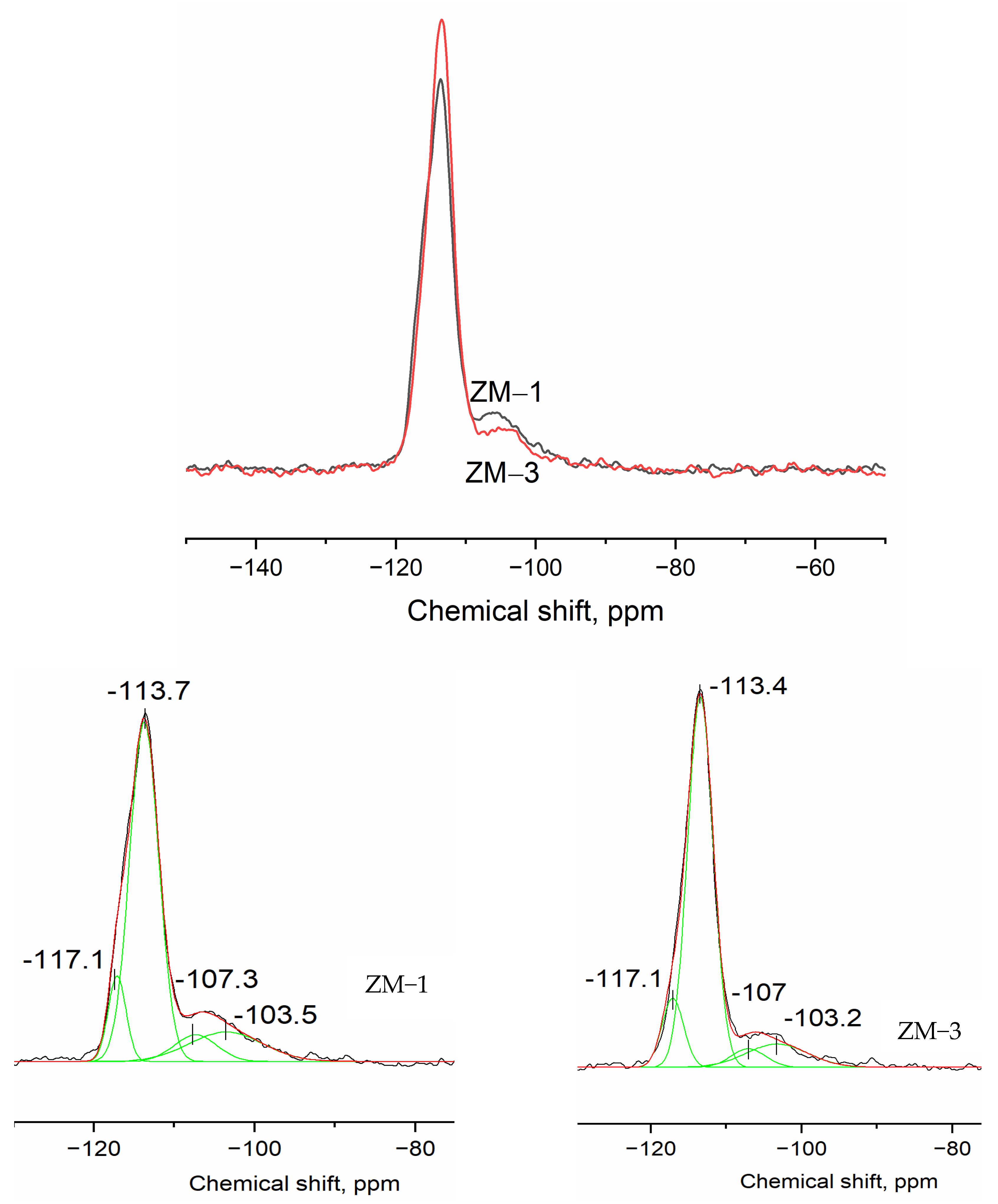

3.1. Characterization

| Catalyst | Crystallite Size 1, nm | Relative Crystallinity, % | Straight Channel 2, % | Sinusoidal Channel 3, % | (Si/Al)bulk 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZM-1 | 0.95 | 84 | 79.59 | 20.41 | 8.2 |

| ZM-2 | 1.58 | 72 | 84.82 | 15.18 | 5.0 |

| ZM-3 | 1.65 | 100 | 87.35 | 12.65 | 7.6 |

| ZM-8 | 1.59 | 85 | 90.50 | 9.50 | 8.0 |

3.2. Effect of H2O/Si Ratio

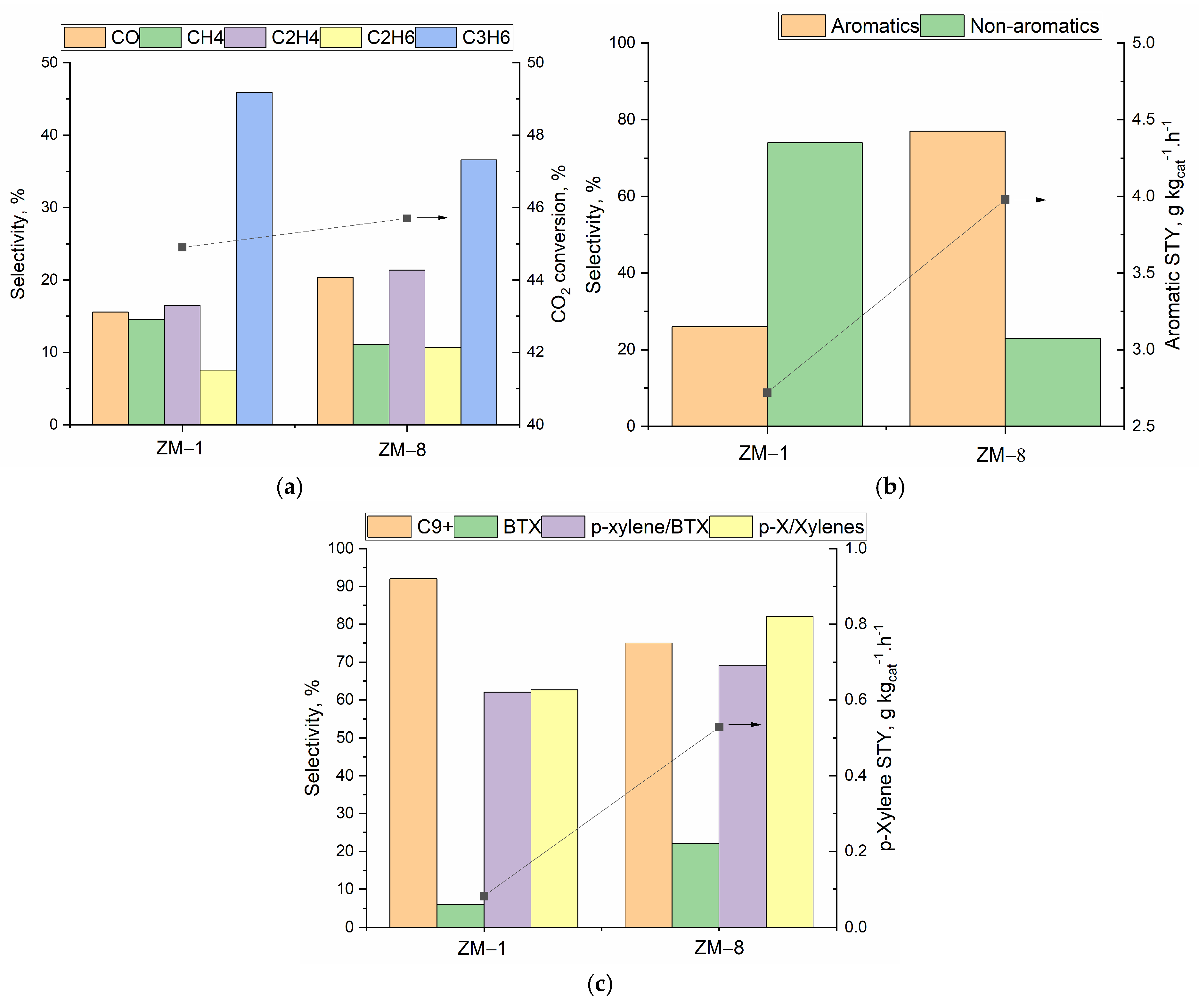

3.3. Catalytic Tests

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dalirian, F.; Rostamizadeh, M.; Alizadeh, R. High-efficient hierarchical [B]-ZSM-5 catalyst by simultaneously using of CTAB surfactant and boron promoter for methanol to olefins reaction. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2021, 47, 3201–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biriaei, R.; Madadi, S.; Kaliaguine, S. Mesostructured Zn/ZSM-5 Zeolite as Catalyst for Furan Deoxygenation. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, S.; Rostamizadeh, M.; Kahforoushan, D. Efficient sulfated high silica ZSM-5 nanocatalyst for esterification of oleic acid with methanol. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 294, 109845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamizadeh, M.; Tran, C.C.; Babar, N.E.A.; Do, T.O.; Dubois, J.L.; Kaliaguine, S. 5 Catalyst development for hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to aromatic hydrocarbons: A review. In Industrial Green Chemistry; Serge, K., Jean-Luc, D., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, T.; Wang, Y.M.; He, M.-Y. Facile synthesis of nano-sized NH4-ZSM-5 zeolites. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 156, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, D.; Milestone, N.; Aldridge, L. NH4+-tetraalkyl ammonium systems in the synthesis of zeolites. Nature 1980, 285, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Yu, G.; Zhang, K.; Qiu, M.; Xue, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y. Morphology-Controlled Synthesis of H-type MFI Zeolites with Unique Stacked Structures through a One-Pot Solvent-Free Strategy. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3871–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Yan, X.; Hu, X.; Wu, J.; Yan, Z. Direct synthesis of b-axis oriented H-form ZSM-5 zeolites with an enhanced performance in the methanol to propylene reaction. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 302, 110246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.-Y.; Sand, L.B.; Thompson, R.W. Nucleation and growth of NH4-ZSM-5 zeolites. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; Volume 28, pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nahari, S.; Dib, E.; Cammarano, C.; Saint-Germes, E.; Massiot, D.; Sarou-Kanian, V.; Alonso, B. Impact of Mineralizing Agents on Aluminum Distribution and Acidity of ZSM-5 Zeolites. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202217992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Vidal-Moya, A.; Miguel, P.J.; Dedecek, J.; Boronat, M.; Corma, A. Selective introduction of acid sites in different confined positions in ZSM-5 and its catalytic implications. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7688–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, M.; Faisal, A.; Öhrman, O.G.; Zhou, M.; Signorile, M.; Crocellà, V.; Nabavi, M.S.; Hedlund, J. Small ZSM-5 crystals with low defect density as an effective catalyst for conversion of methanol to hydrocarbons. Catal. Today 2020, 345, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, G.; Gu, Q.; Chen, J.; Ma, L.; Li, X.; He, Q.; et al. Maximizing sinusoidal channels of HZSM-5 for high shape-selectivity to p-xylene. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Toyoda, H.; Li, Q.; Sun, Y.; Samya, B.; Gies, H.; Yokoi, T. Impact of anionic species on the crystallization and aluminum localization in the zeolite framework. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 384, 113456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gu, W.; Kong, D.; Guo, H. The significant effects of the alkali-metal cations on ZSM-5 zeolite synthesis: From mechanism to morphology. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 183, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xiao, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Fan, X.; Kong, L.; et al. Facile Synthesis of Nanosheet-Stacked Hierarchical ZSM-5 Zeolite for Efficient Catalytic Cracking of n-Octane to Produce Light Olefins. Catalysts 2022, 12, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamami, M.; Sand, L. Synthesis and crystal growth of zeolite (NH4, TPA)-ZSM-5. Zeolites 1983, 3, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ren, X.; Mezari, B.; Liu, Y.; Pornsetmetakul, P.; Liutkova, A.; Kosinov, N.; Hensen, E.J. Direct synthesis of Al-rich ZSM-5 nanocrystals with improved catalytic performance in aromatics formation from methane and methanol. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 351, 112485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Grieken, R.; Sotelo, J.L.; Menéndez, J.M.; Melero, J.A. Anomalous crystallization mechanism in the synthesis of nanocrystalline ZSM-5. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2000, 39, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Gao, Q.; Wang, B.; Li, G.; Yan, L.; Suo, J. Some new features on synthesis of titanium silicalite-1 in a non-TPAOH inorganic reactant synthetic system. J. Porous Mater. 2005, 12, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, T.M.; Toyoda, H.; Sawada, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Yokoi, T. Aluminum Distribution on the Microporous and Hierarchical ZSM-5 Intracrystalline and Its Impact on the Catalytic Performance. Chem. Bio Eng. 2024, 1, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Jia, X.; Wang, S.; Fan, S.; He, S.; Wang, P.; Qin, Z.; Dong, M.; Fan, W.; Wang, J. Regulating the distribution of acid sites in ZSM-11 zeolite with different halogen anions to enhance its catalytic performance in the conversion of methanol to olefins. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 341, 112051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashkova, V.; Klein, P.; Dedecek, J.; Tokarová, V.; Wichterlová, B. Incorporation of Al at ZSM-5 hydrothermal synthesis. Tuning of Al pairs in the framework. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 202, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio, J.R.; Li, S.; Jones, C.B.; Nimlos, C.T.; Wang, Y.; Kunkes, E.; Vattipalli, V.; Prasad, S.; Moini, A.; Schneider, W.F. Cooperative and competitive occlusion of organic and inorganic structure-directing agents within chabazite zeolites influences their aluminum arrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4807–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Yang, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, C.; Teng, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Z. A diffusion anisotropy descriptor links morphology effects of H-ZSM-5 zeolites to their catalytic cracking performance. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Xiang, W.; Ye, Z.; Wu, L.; Xia, W.; Huang, H.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, G.; et al. Direct Synthesis of para-Xylene from CO2 Hydrogenation with a Record-High Space-Time Yield. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 24442–24450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.; Pinard, L.; Benghalem, M.A.; Daou, T.J.; Melinte, G.; Ersen, O.; Asahina, S.; Gilson, J.-P.; Valtchev, V. Preparation of Single-Crystal “House-of-Cards”-like ZSM-5 and Their Performance in Ethanol-to-Hydrocarbon Conversion. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 4639–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarneau, A.; Villemot, F.; Rodriguez, J.; Fajula, F.; Coasne, B. Validity of the t-plot Method to Assess Microporosity in Hierarchical Micro/Mesoporous Materials. Langmuir 2014, 30, 13266–13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, A.M.G.; Souza, M.J.; Melo, D.M.; Araujo, A.S. Cobalt and nickel supported on HY zeolite: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic properties. Mater. Res. Bull. 2006, 41, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, B.A.; Wang, H.; Norbeck, J.M.; Yan, Y. Controlling size and yield of zeolite Y nanocrystals using tetramethylammonium bromide. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 59, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkova, V.; Drenchev, N.; Ivanova, E.; Mihaylov, M.; Hadjiivanov, K. Surprising Coordination Chemistry of Cu+ Cations in Zeolites: FTIR Study of Adsorption and Coadsorption of CO, NO, N2, and H2O on Cu–ZSM-5. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 15292–15302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Liu, X.; Cheng, F.; Zhao, W.; Wen, S.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yu, N.; Yin, D. Selective hydrogenolysis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to produce biofuel 2, 5-dimethylfuran over Ni/ZSM-5 catalysts. Fuel 2020, 274, 117853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.M.S. Cerium modified MCM-41 nanocomposite materials via a nonhydrothermal direct method at room temperature. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 315, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creci, S.; Wang, X.; Carlsson, P.-A.; Skoglundh, M. Tuned Acidity for Catalytic Reactions: Synthesis and Characterization of Fe- and Al-MFI Zeotypes. Top. Catal. 2019, 62, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianfar, E. Ethylene to propylene conversion over Ni-W/ZSM-5 catalyst. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2019, 92, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, J.; Beato, P.; Lundegaard, L.F.; Skibsted, J. Distribution of Aluminum over the Tetrahedral Sites in ZSM-5 Zeolites and Their Evolution after Steam Treatment. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 15595–15613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Luo, W.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H. Hierarchical ZSM-5 nanosheets for production of light olefins and aromatics by catalytic cracking of oleic acid. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.R.; Sushkevich, V.L.; van Bokhoven, J.A. Factors Affecting the Generation and Catalytic Activity of Extra-Framework Aluminum Lewis Acid Sites in Aluminum-Exchanged Zeolites. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Pidko, E.A. The nature and catalytic function of cation sites in zeolites: A computational perspective. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, A.; Su, Y.; Fang, H.; Shen, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, L.; Deng, F. Extra-framework aluminium species in hydrated faujasite zeolite as investigated by two-dimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy and theoretical calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, S.M.; Mezari, B.; Filonenko, G.A.; Magusin, P.C.; Rigutto, M.S.; Pidko, E.A.; Hensen, E.J. Influence of extraframework aluminum on the brønsted acidity and catalytic reactivity of faujasite zeolite. ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallmoser, S.; Ikuno, T.; Wagenhofer, M.; Kolvenbach, R.; Haller, G.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Lercher, J. Impact of the local environment of Brønsted acid sites in ZSM-5 on the catalytic activity in n-pentane cracking. J. Catal. 2014, 316, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Bao, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, X. A high-resolution solid-state NMR study on nano-structured HZSM-5 zeolite. Catal. Lett. 1999, 60, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goursot, A.; Berthomieu, D. Calculations of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Parameters in Zeolites. In Calculation of NMR and EPR Parameters: Theory and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, W.J.; Gil, B.; Tarach, K.A.; Góra-Marek, K. Top-down engineering of zeolite porosity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 7484–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C.; Siozios, V.; Mück-Lichtenfeld, C.; Hunger, M.; Hansen, M.R.; Koller, H. Hydrogen bond formation of Brønsted acid sites in zeolites. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyraghi, S.; Rostamizadeh, M.; Alizadeh, R. Dual-templated synthesis of Si-rich [B]-ZSM-5 for high selective light olefins production from methanol. Polyolefins J. 2021, 8, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Weitz, E. Modification of acid sites in ZSM-5 by ion-exchange: An in-situ FTIR study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 316, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Du, K.; Pan, D.; Li, H.; Ding, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y. Distinguishing and unraveling classical and non-classical pathways in MFI zeolite crystallization: Insights into their contributions and impact on the final product. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 4048–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, S.; Peng, P.; Liu, Z.; Chowdhury, A.D.; Liu, G. Selectivity control by zeolites during methanol-mediated CO2 hydrogenation processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 2726–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, C.-C.; Kaliaguine, S. Rhodium-doped iron oxides promoted by sodium for highly selective hydrogenation of CO2 to ethanol and C2+ hydrocarbons. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X. Preparation of a hollow b-oriented ZSM-5 zeolite-supported zinc catalyst with enhanced catalytic properties via desilication–recrystallization for methane co-aromatization with propane. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 7870–7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, A.; Guo, X.; Song, C. MFI nanosheets: A rising star in zeolite materials. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, A.; Gawande, K.; Li, G.; Shang, S.; Dai, C.; Fan, W.; Han, Y.; Song, C.; Ren, L.; et al. b-Axis-Oriented ZSM-5 Nanosheets for Efficient Alkylation of Benzene with Methanol: Synergy of Acid Sites and Diffusion. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 3794–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Yao, R.; Ge, Q.; Xu, D.; Fang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, J. Precisely regulating Brønsted acid sites to promote the synthesis of light aromatics via CO2 hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 283, 119648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Willhammar, T.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Sun, Q.; Meng, X.; Carrillo-Cabrera, W.; Zou, X.; Xiao, F.-S. ZSM-5 zeolite single crystals with b-axis-aligned mesoporous channels as an efficient catalyst for conversion of bulky organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4557–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Jang, J.; Kim, T.; Shim, S.E.; Baeck, S.-H. Selective hydrodealkylation of C9+ aromatics to benzene, toluene, and xylenes (BTX) over a Pt/H-ZSM-5 catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 407, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Yang, J.; Qian, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, D. Exploring the Reaction Paths in the Consecutive Fe-Based FT Catalyst–Zeolite Process for Syngas Conversion. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3797–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murciano, R.; Serra, J.M.; Martínez, A. Direct hydrogenation of CO2 to aromatics via Fischer-Tropsch route over tandem K-Fe/Al2O3+H-ZSM-5 catalysts: Influence of zeolite properties. Catal. Today 2024, 427, 114404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, B. Identifying the key steps determining the selectivity of toluene methylation with methanol over HZSM-5. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Catalyst | Al Source | Template | NH4+ Source | H2O/SiO2 | x (NH4+/Al) | y (Na+/Al) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZM-1 | NaAlO2 | TPABr | NH4NO3 | 150 | 1 | 1 |

| ZM-2 | NaAlO2 | TPABr | NH4NO3 | 150 | 2 | 1 |

| ZM-3 | Al(O-i-Pr)3 | TPABr | NH4NO3 | 150 | 1 | 0 |

| ZM-4 | NaAlO2 | TPABr | - | 150 | 0 | 2 |

| ZM-5 | NaAlO2 | TPABr | - | 150 | 0 | 1 |

| ZM-6 | NaAlO2 | TPAOH | - | 150 | 0 | 1 |

| ZM-7 | NaAlO2 | TPABr | NH4OH | 150 | 1 | 1 |

| ZM-8 | NaAlO2 | TPABr | NH4NO3 | 75 | 1 | 1 |

| ZM-9 | NaAlO2 | TPABr | NH4NO3 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Catalyst | SBET (m2 g−1) | Sexternal (m2 g−1) | Vtotal (cc g−1) | Vmicro (cc g−1) | Vmeso (cc g−1) | DFT Pore (nm) | HF * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZM-1 | 368 | 144 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 1.1 | 0.18 |

| ZM-2 | 114 | 51 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 3.1 | 0.17 |

| ZM-3 | 258 | 99 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 2.8 | 0.12 |

| ZM-8 | 306 | 83 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 3.5 | 0.15 |

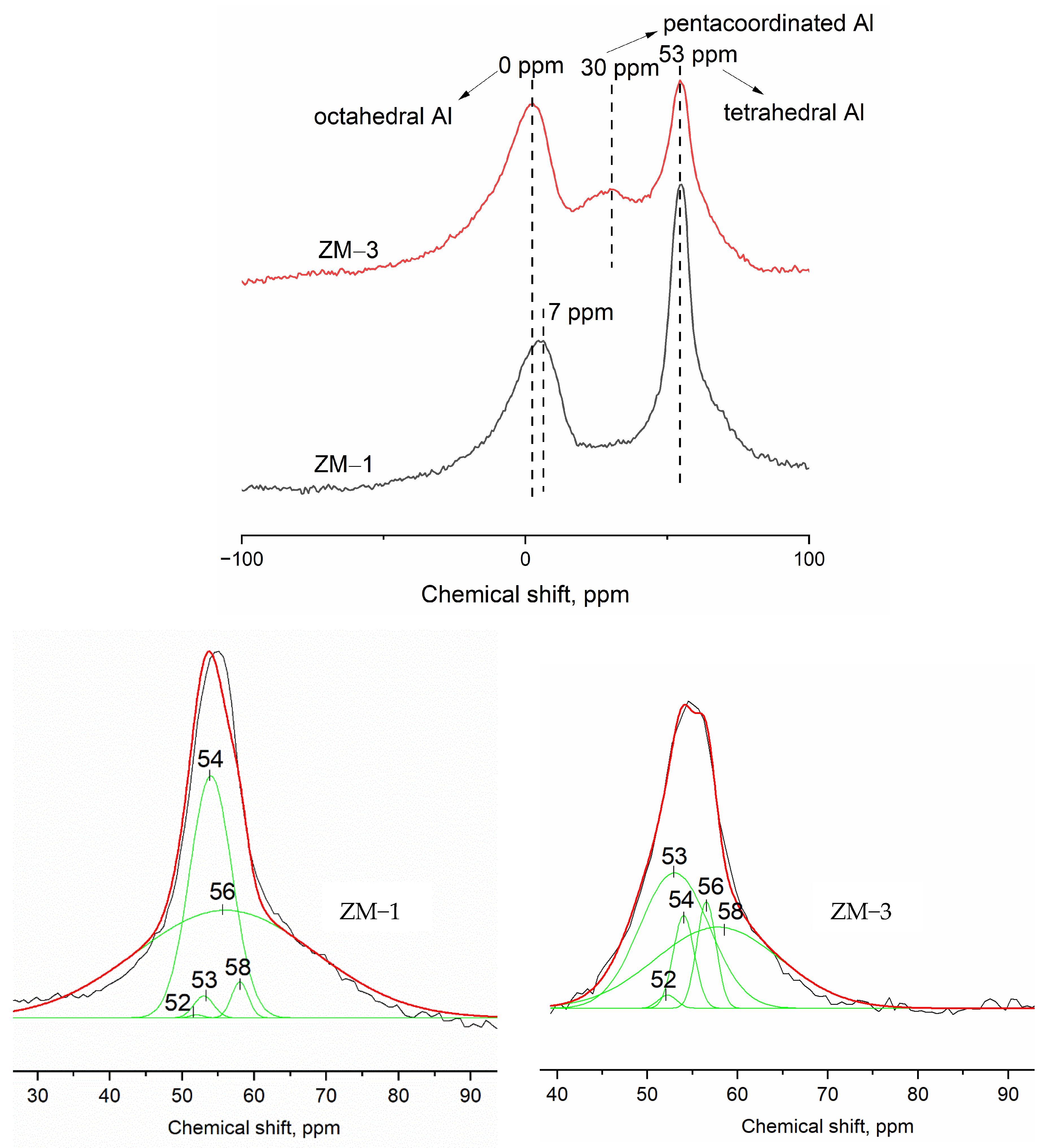

| Catalyst | Chemical Shift (ppm) Assignment of Al Sites and Relative Peak Areas, % | 56 + 54, % | 54/56 | (Si/Al)framework * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52 | 53 | 54 | 56 | 58 | ||||

| ZM-1 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 33.3 | 63.0 | 2.0 | 96.3 | 0.5 | 12.8 |

| ZM-3 | 1.0 | 39.5 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 42.5 | 16.8 | 0.9 | 20.4 |

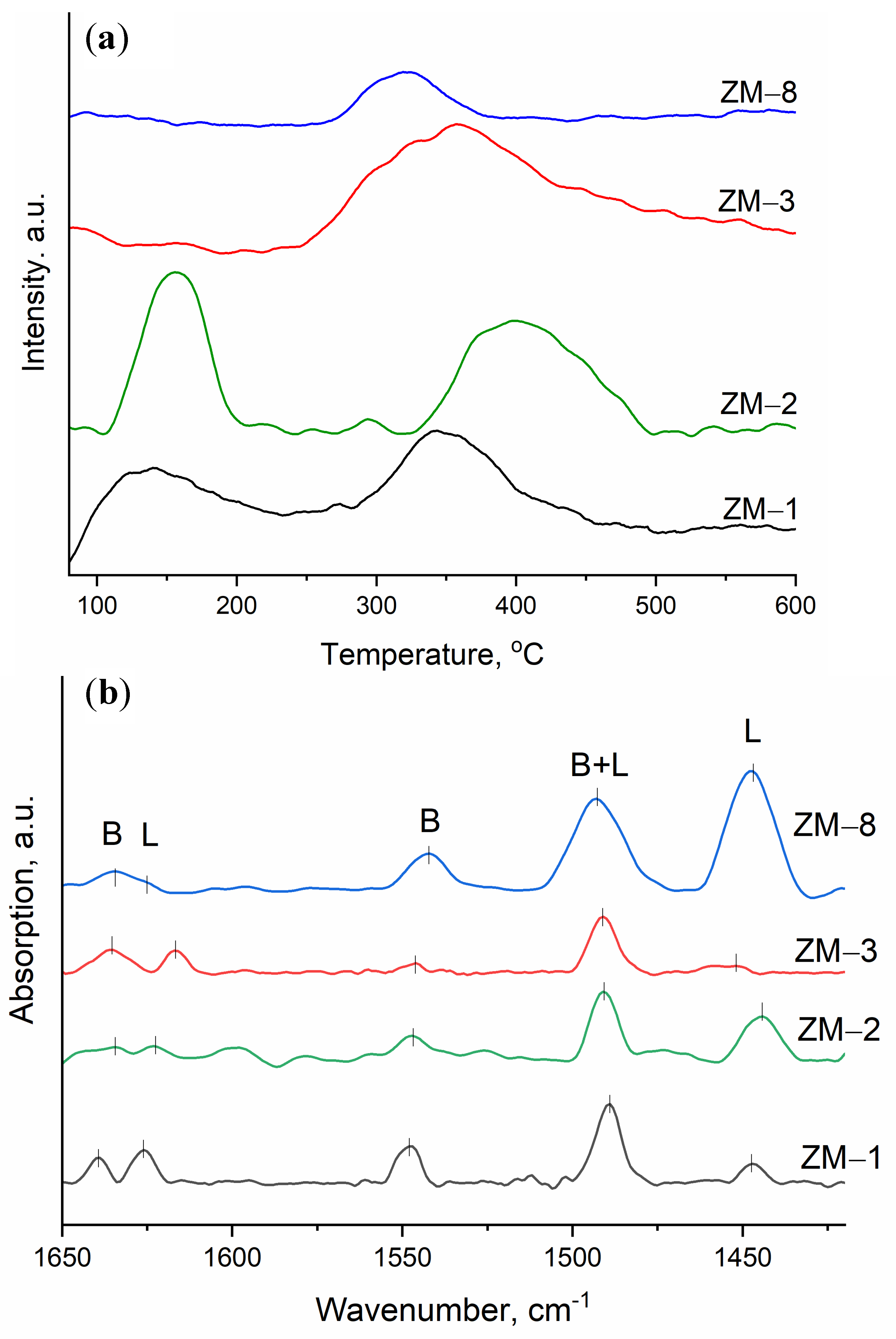

| Catalyst | Acidity, μmol NH3 g−1 | Peak Temperature, °C | Py-FTIR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weak | Strong | Total | TP1 | TP2 | Brønsted | Lewis | Brønsted/Lewis | |

| ZM-1 | 7.2 | 12.5 | 19.7 | 141 | 341 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 2.03 |

| ZM-2 | 16.0 | 20.8 | 36.8 | 152 | 374 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.41 |

| ZM-3 | 0.6 | 25.0 | 25.6 | 158 | 357 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.91 |

| ZM-8 | 0.20 | 3.72 | 3.92 | 173 | 322 | 0.52 | 2.23 | 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rostamizadeh, M.; Tran, C.-C.; Do, T.-O.; Kaliaguine, S. One-Pot Direct Synthesis of b-Axis-Oriented and Al-Rich ZSM-5 Catalyst via NH4NO3-Mediated Crystallization for CO2 Hydrogenation. Catalysts 2026, 16, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010047

Rostamizadeh M, Tran C-C, Do T-O, Kaliaguine S. One-Pot Direct Synthesis of b-Axis-Oriented and Al-Rich ZSM-5 Catalyst via NH4NO3-Mediated Crystallization for CO2 Hydrogenation. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleRostamizadeh, Mohammad, Chi-Cong Tran, Trong-On Do, and Serge Kaliaguine. 2026. "One-Pot Direct Synthesis of b-Axis-Oriented and Al-Rich ZSM-5 Catalyst via NH4NO3-Mediated Crystallization for CO2 Hydrogenation" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010047

APA StyleRostamizadeh, M., Tran, C.-C., Do, T.-O., & Kaliaguine, S. (2026). One-Pot Direct Synthesis of b-Axis-Oriented and Al-Rich ZSM-5 Catalyst via NH4NO3-Mediated Crystallization for CO2 Hydrogenation. Catalysts, 16(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010047