Abstract

In this study, MIL-88A(Fe)-X (X = 300, 500, 600) was successfully synthesized via electron beam irradiation and employed to activate periodate (PI) for tetracycline (TC) degradation. Experimental results indicated that the optimal irradiation dosage was 300 kGy for MIL-88A(Fe)-X. And 99.0% of TC could be degraded under the optimum reaction conditions (catalyst dosage of 20 mg, PI concentration of 1.0 mM, initial TC concentration of 10 mg/L, pH = 6.8, and temperature of 25 °C) in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system. Furthermore, quenching experiments were conducted to investigate the degradation mechanism, revealing IO3· and IO4· radicals played predominant roles in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system. The system exhibited excellent stability and recyclability, maintaining a degradation efficiency of over 90% after three consecutive cycles. This study demonstrated that the MIL-88A(Fe)/PI system achieved rapid degradation and high reproducibility for TC removal. The proposed method could effectively reduce antibiotic residues in the environment, offering a promising strategy for addressing antibiotic pollution. Future work can be conducted to assess its practical application performance under various environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

The extensive application of antibiotics in medical treatment, such as animal husbandry and aquaculture, enable their continuous accumulation in water environment, posing a serious threat to ecosystems and human health. Generally, antibiotics are difficult to decompose naturally; their long-term presence in the environment not only disrupts the balance of the microbial community, but also induces the generation and spread of drug-resistant strains [1,2]. At present, the treatment methods of antibiotics mainly include membrane separation, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) technologies, electrocoagulation, ion exchange and biological method [3,4,5]. AOPs have garnered significant attention due to their exceptional performance in the removal of persistent organic pollutants [6,7]. In particular, the rapid development of periodate-based AOPs (PI-AOPs) is attributed to their high efficiency in the degradation of organic contaminants, coupled with strong resistance to interference from coexisting ions. As a typical non-selective advanced oxidant, PI exhibits high chemical stability compared to liquid oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide [8]. Its solid form offers enhanced safety and convenience in storage and transportation, thereby facilitating easier handling and operation. Under normal conditions, PI remains relatively stable and is not prone to spontaneous decomposition or explosion [9]. Furthermore, the use of PI does not generate solid sludge during the degradation of pollutants, making it an economically and environmentally attractive option.

However, the inherent oxidative capacity of PI is limited, with a redox potential of only 1.6 V, and it reacts relatively slow with organic contaminants [10]. Therefore, various activation methods are required to activate PI to generate reactive species (RS) with strong oxidizing ability for efficient removal of organic pollutants. Researchers have explored various methods to activate PI, including direct photoactivation [11] (using UV or visible light), thermal activation [12], photocatalysis [13], and activation by transition metals and their compounds [14,15]. However, a key limitation of these approaches is their external energy inputs, hindering wider application. This challenge has driven the exploration of both homogeneous and heterogeneous transition metal-based catalysts, which are promising for PI activation owing to their efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline porous materials which are formed by metal ions or metal clusters bridged by organic ligands [16,17]. They not only have adsorption and catalytic properties, but also feature abundant unsaturated sites, high structural adjustability, and easy functionalization of organic ligands and metal ions [18,19]. One of the most crucial roles that MOF plays in material synthesis is to construct composite materials that combine MOF with another type of material, such as metal oxides. Among them, the MIL-Fe series of MOFs have performed outstandingly in the treatment of organic pollutants due to the high stability, low toxicity and visible light response characteristics of Fe-based coordination [20]. As one of the most abundant transition metals in the crust of earth, Fe boasts high reactivity, relatively low cost, and favorable environmental characteristics. In recent years, some research teams have attempted to use Fe-based MOFs (Fe-MOFs) materials in combination with PI to treat pollutants [21]. For instance, in dye wastewater treatment, this system efficiently degrades contaminants and can be reused repeatedly [22].

Traditional synthesis methods for MOFs, such as hydrothermal and solvothermal approaches, are energy-intensive due to their requirements for long reaction times, high temperatures, elevated autogenous pressure, and closed systems [23,24]. The advanced synthesis of MOFs has formed a diversified technical system. The hard template method regulates the crystal morphology and pore structure through sacrificial and non-sacrificial templates, significantly increasing the specific surface area and exposure of active sites [25]. Non-traditional synthetic techniques (such as mechanochemical and irradiation synthesis, etc.) achieve efficient and large-scale preparation, addressing the pain points of traditional solvothermal methods. In contrast, irradiation techniques have emerged as a powerful alternative for MOFs synthesis and modification, enabling tailored modulation of their physicochemical properties [26]. As a promising strategy, irradiation offers notable fast and environmental advantages in MOFs processing [27]. After the irradiation treatment, significant alterations can occur in the physicochemical characteristics of MOFs, including changes in particle size, specific surface area, morphology, and stability [28].

In this study, MIL-88A(Fe), as a typical Fe-MOF, was successfully prepared by electron beam irradiation technology. The prepared MIL-88A(Fe) was characterized and applied to activate PI to evaluate its catalytic performance using TC as the target pollutant. The mechanism for TC degradation by MIL-88A(Fe)/PI was also explored. Meanwhile, the degradation pathway of TC and the reusability of MIL-88A(Fe) were studied. Based on the experimental results, we proposed three possible degradation pathways, providing a strong basis for a deeper understanding of the TC degradation mechanism of this system. This research provides new ideas and methods for the treatment of antibiotic contamination.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of MIL-88A(Fe)

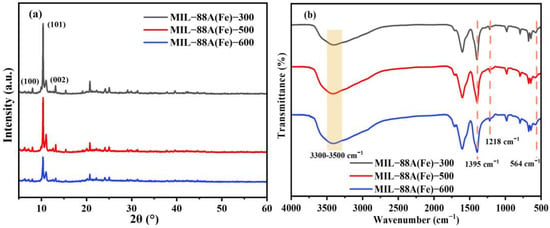

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of MIL-88A(Fe)-X (X mean the irradiation dose of 300, 500 and 600 kGy) are displayed in Figure 1a. As shown in Figure 1a, all the prepared MIL-88A(Fe)-X exhibit diffraction peaks at 2θ = 7.4°, 2θ = 10.2°, and 2θ = 13.0°, which belong to the (100), (101), and (002) planes of MIL-88A(Fe), respectively. This result agrees with the previous study [29], indicating electron beam irradiation technology can successful synthesize MIL-88A(Fe) with the irradiation dose range from 300 to 600 KGy. The diffraction peaks are sharp, and no distinct impurity peaks are observable, confirming that the product has good crystallinity and no obvious impurity phase. To conduct a detailed examination of the functional groups of MIL-88A(Fe), the Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR) spectra of MIL-88A(Fe)-X prepared at different irradiation doses are shown in Figure 1b. Obviously, MIL-88A(Fe)-X shares similar absorption peaks. The characteristic absorption peak at 564 cm−1 belongs to the Fe-O bond, and the characteristic peak at 1395 cm−1 originates from the symmetrical stretching vibration of the carboxyl group (-COOH) in MIL-88A(Fe)-X. The wide absorption band that occurs in the 3300–3500 cm−1 band corresponds to the stretching vibration of O-H in water molecules. This peak is a typical feature of water molecules in MOF materials and is closely related to the pore structure and adsorption performance of MIL-88A(Fe). In addition, the characteristic peak at 1218 cm−1 belongs to the C-O asymmetric stretching vibration of the organic linker. The above characteristic peaks are similar to those of MIL-88A(Fe) reported in previous studies, further indicating all MIL-88A(Fe)-X samples are successfully synthesized [30,31,32].

Figure 1.

XRD patterns (a) and FT-IR spectra (b) of MIL-88A(Fe)-X (X = 300, 500 and 600).

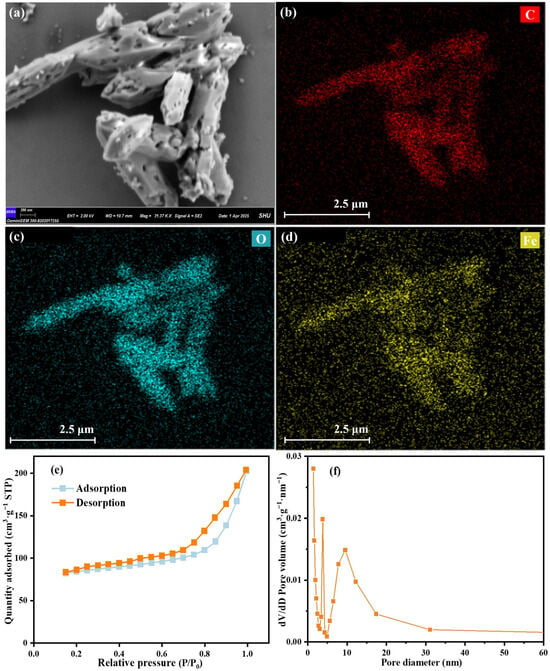

The morphology of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 is characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As displayed in Figure 2a, MIL-88A(Fe)-300 exhibits the morphology of spindle-like, which is the same as the hydrothermal synthesized one [33]. However, compared with the hydrothermal synthesized MIL-88A(Fe), there are a large number of pore structures on the surface of the irradiated MIL-88A(Fe)-300. The results of energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) surface scanning (Figure 2b–d) shows that C, O and Fe elements are uniformly distributed on the surface of MIL-88A(Fe)-300, suggesting that the synthesis of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 is successful and the element distribution is uniform, further confirming its structural stability.

Figure 2.

SEM image (a), EDS patterns (b–d), N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm (e) and pore size distribution (f) of MIL-88A(Fe)-300.

As shown in Figure 2e, the adsorption–desorption isotherm of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 belongs to type IV isotherm with a H3-type hysteresis loop, which confirms the mesoporous structure of MIL-88A(Fe)-300, in line with its the pore size distribution in Figure 2f. The specific surface area of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 is 204 m2/g, which is much higher than the one prepared by solvothermal approach [34]. In addition, MIL-88A(Fe)-300 shows the total pore volume of 0.32 cm3/g and the average pore diameter of 4.8 nm (Table S1). The high specific surface area of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 is conducive to have more active sites, which promotes the reaction of TC degradation.

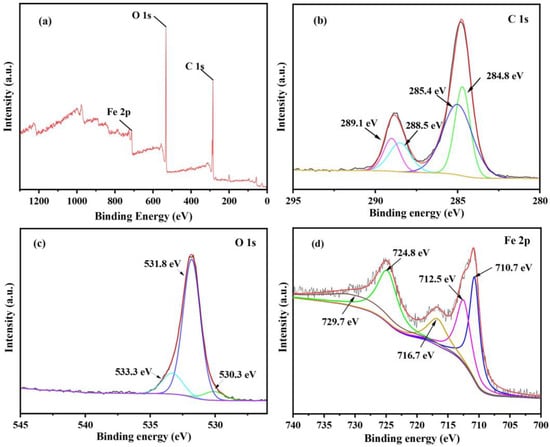

Figure 3a shows the survey X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum of MIL-88A(Fe)-300, indicating that C, O, and Fe elements coexist in MIL-88A(Fe)-300, which is consistent with the EDS results. As shown in Figure 3b, the C 1s spectrum of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 shows four characteristic peaks at 284.8, 285.4, 288.5 and 289.1 eV, attributing to C-C/C=C, C-O, C=O and O-C=O, respectively, aligning with the FT-IR results. The O 1s spectrum can be divided into three main peaks at 530.3, 531.8 and 533.3 eV, ascribing to the lattice oxygen, adsorbed oxygen and carboxylic acid groups, respectively (Figure 3c). MIL-88A(Fe)-300 shows a lower lattice oxygen content than adsorbed oxygen content, illustrating a higher oxygen defect content [35]. As shown in Figure 3d, the Fe 2p spectrum exhibits the peaks at 712.5 eV (Fe 2p3/2), 729.7 eV (Fe 2p1/2) and 716.7 eV (satellite peak), attributing to the presence of Fe3+ species. In addition, two peaks are observed at 710.7 eV (Fe 2p3/2) and 724.8 eV (Fe 2p1/2), corresponding to Fe2+ species. The result shows that both Fe2+ and Fe3+ exist in MIL-88A(Fe)-300, which is beneficial for the redox recycling between them, thereby efficiently activating PI to produce active species and degrading TC [36].

Figure 3.

XPS spectrum of MIL-88A(Fe)-300: Survey (a), C 1s (b), O 1s (c) and Fe 2p (d).

2.2. Catalytic Performance of MIL-88A(Fe)-X

2.2.1. Effect of Different Catalysts and Reaction Conditions

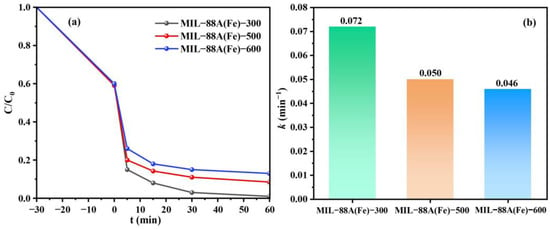

The catalytic performance of MIL-88A(Fe)-X to activate PI for TC degradation is evaluated and illustrated in Figure 4a. The MIL-88A(Fe)-X prepared by electron beam irradiation technology can activate PI to degrade TC effectively. Among the MIL-88A(Fe)-X, MIL-88A(Fe)-300 shows the best catalytic performance. The TC decomposition rate is 99.0%, 91.5% and 87.0% in the MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI, MIL-88A(Fe)-500/PI and MIL-88A(Fe)-600/PI systems, respectively, demonstrating that high irradiation dose is negative for the catalytic activities of MIL-88A(Fe)-X. The results can be attributed to the structure of MIL-88A(Fe)-X, which can be damaged during the preparation under high irradiation dose, thus reducing its catalytic performance for TC degradation. The reaction rate constant (k) is a physical quantity that measures the speed of a chemical reaction. The pseudo-first-order kinetic model can visually evaluate catalytic activity and quantitatively compare catalytic efficiency under different experimental conditions. The k of TC degradation for MIL-88A(Fe)-300, MIL-88A(Fe)-500 and MIL-88A(Fe)-600 is 0.072, 0.050 and 0.046 min−1, respectively (Figure 4b). Obviously, MIL-88A(Fe)-300 possesses the highest k value.

Figure 4.

TC degradation rates (a) and the k values (b) in MIL-88A(Fe)-X/PI systems (TC = 10 mg/L, PI = 1.0 mM, catalyst = 20 mg, pH = 6.8, Temperature = 25 °C).

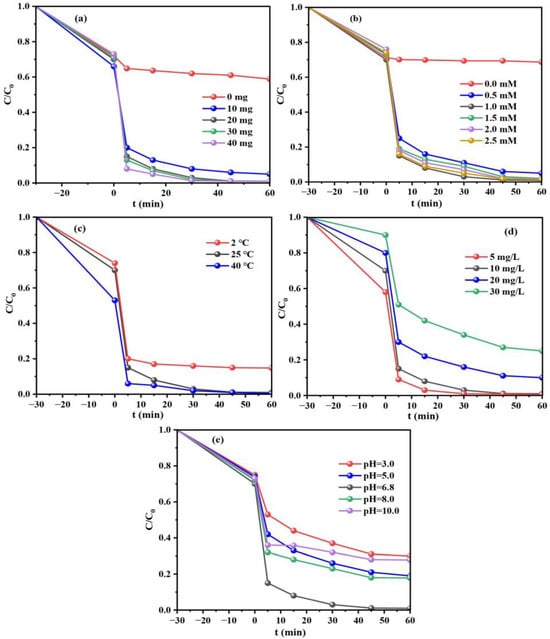

The influences of reaction conditions are further studied to evaluate the TC degradation in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system (catalyst dosage, PI concentration, Temperature, TC concentration and initial pH). As shown in Figure 5a, the degradation rate of TC rises from 95.0% to 99.0% when the catalyst dosage increases from 10 to 20 mg. However, further increase in catalyst dosage can only lead to a slight enhancement of TC degradation rate. An increase in catalyst dosage can promote the collision between reactants and improve the reaction rate [37], whereas excessive catalyst may lead to their aggregation, limiting the utilization of active sits and the degradation of TC. As a result, the catalyst dosage of 20 mg is the most appropriate dosage in the experiment. It can be seen in Figure 5b that the degradation rate of TC improves from 95.0% to 99.0% by increasing the PI concentration from 0.5 to 1.0 mM, and then it decreases slightly to 98.6% when PI concentration further increases to 2.5 mM. This is mainly because superfluous PI can compete with TC for reactive radicals to consume hydroxyl radical (·OH), etc. species, resulting in the reduce of TC degradation rate (Equation (1)) [38]. In addition, an increase in temperature causes the cleavage of the I-O bond, thereby producing more reactive species (Figure 5c). Figure 5d shows that the degradation rate of TC significantly reduces from 99.5% to 75.0% as its initial concentration increases (from 5 to 30 mg/L). It is known that pH is crucial for the catalytic efficiency, as it influences the characteristics of both the catalyst and the substrate, and also correlates to the generation of active species [39]. As presented in Figure 5e, TC shows the highest degradation efficiency of 99.0% under neutral condition (pH = 6.8). This may be because the structure of the catalyst is easily damaged in acid condition and limits its activity. In addition, the state of iodate species is different in vary pH conditions. IO4− mainly exists in the system when pH is less than 8.0, while the dimer (H3IO62−) dominates in the system when pH is greater than 8.0. The lower reduction potential of H3IO62−/IO3− (+0.686 V), compared with IO4−/IO3− (+1.298 V), may result in the lower TC degradation rate [40].

Figure 5.

TC degradation rates in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system under different reaction conditions: Catalyst dosage (a), PI concentration (b), Temperature (c), TC concentration (d) and pH (e).

2.2.2. Effect of Coexistence Substances

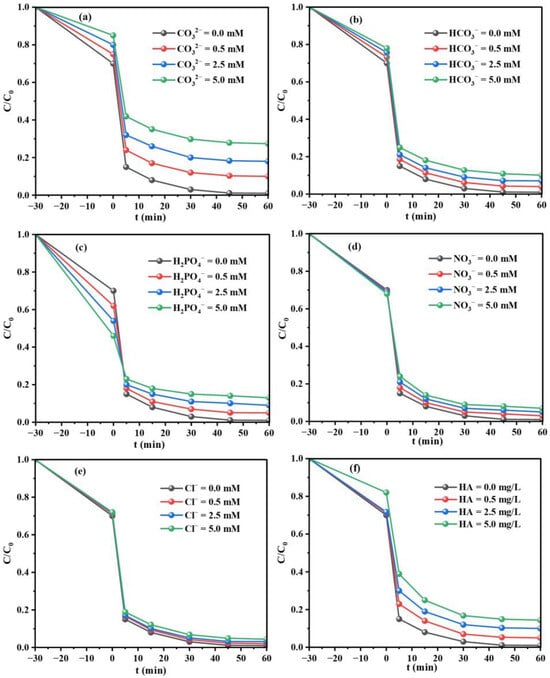

There are a variety of inorganic salts and natural organic matters such as Cl−, HCO3−, NO3−, H2PO4−, CO32− and humic acid (HA), which exist in actual aqueous matrices. As a result, the influence of coexistence substances under different concentrations (0.0–5.0 mM) on TC degradation are investigated. In the presence of CO32−, the degradation rate of TC is notably hindered from 99.0% to 72.6% (Figure 6a). CO32− can efficiently quench ·OH and produce carbonate radicals (CO3·−) that possess a lower redox potential than ·OH (Equation (2)) [41]. HCO3−, H2PO4− and NO3− can also interact with radicals to form low-activity CO3·−, H2PO4∙ and NO3∙ (Equations (3)–(5)). However, their negative influences toward TC degradation are smaller than that of CO32− (Figure 6b–d), attributing to the relatively weak ability to capture ∙OH [42]. A shown in Figure 6e, Cl− has a neglective effect on the inhibition of TC degradation, and the removal efficiency remains above 95%, indicating that the MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system has a strong resistance to the interference of Cl−. This phenomenon can be attributed to the reaction inertness between Cl− and the active species, which not only reduces the risk of toxic chlorinated intermediates, but also enhances the stability of the system. Additionally, the degradation rate of TC also decreases after the introduction of HA (Figure 6f). This is primarily due to the electrostatic interaction between HA and TC that hinders the adsorption of TC on catalyst, and the benzene ring in HA can also engage in π-π interaction with TC [43].

Figure 6.

Effects of different inorganic anions and natural organic compound on TC degradation in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system: CO32− (a), HCO3− (b), H2PO4− (c), NO3− (d), Cl− (e) and HA (f) (TC = 10 mg/L, PI = 1.0 mM, catalyst = 20 mg, pH = 6.8, Temperature = 25 °C).

2.2.3. The Stability and Recyclability of Catalyst

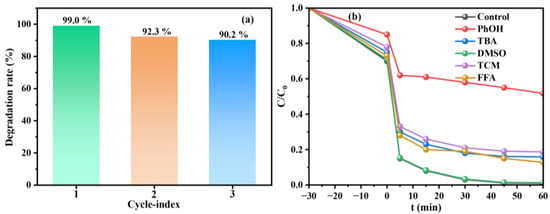

XRD and FT-IR characterizations of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 before and after the reaction are compared to further investigate its stability. XRD patterns (Figure S1a) show that the main diffraction peaks (2θ = 7.4° (100), 2θ = 10.2° (101), and 2θ = 13.0° (002)) of the used catalyst are consistent with the fresh one with only a slight decline in their intensities, which may be attributed to the coverage of the degradation intermediates of TC. Similarly, FT-IR spectrum (Figure S1b) of the used catalyst also maintains the characteristic peaks of the fresh sample. The peak at ~950 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of Fe-O bonds, which is the core active site for activating periodate, and the increased peak intensity after reaction confirms the participation of active sites in electron transfer or intermediate adsorption [44,45]. The changes in carboxyl vibration peaks at ~1400 and ~1600 cm−1 reflect the adjustment of carboxyl coordination environment caused by the valence fluctuation of Fe3+ without framework collapse [46,47]. Cyclic experiments are performed to assess the recyclability of the material. As shown in Figure 7a, the degradation rate of TC is 99.0%, 92.3% and 90.2% after the first, second and third cycling, respectively. The slight decrease is likely due to the blockage of active sites over time and the inevitable loss of catalyst during each run [48,49]. Therefore, MIL-88A(Fe)-300 shows promising recyclability and stability in TC degradation.

Figure 7.

Cyclic results (a) and quenching experiments (b) of TC degradation in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system.

2.3. Reaction Mechanisms

2.3.1. Identification of Reactive Species

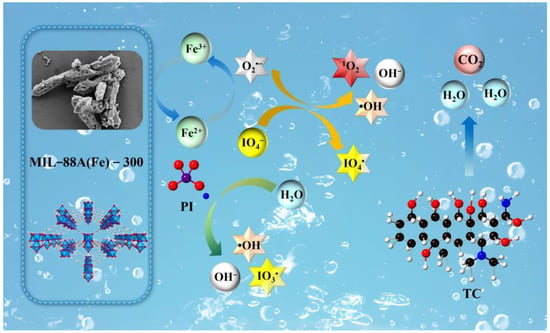

Quenching experiments are conducted to identify the reactive species present in the MIL-88A(Fe)/PI system (Figure 7b). Tert-butanol (TBA), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), trichloromethane (TCM), and furfuryl alcohol (FFA) are used as selective quenchers to investigate the effects of ·OH, Fe(IV), O2·−, and 1O2 during the degradation process of TC. Moreover, phenol (PhOH) is used to simultaneously quench IO3·and IO4· [32]. When PhOH is added, the degradation of TC in the MIL-88A(Fe)/PI system that is most significantly inhibited compares with the control group (from 99.0% to 48.2%), indicating that IO3· and IO4· contribute the most to the degradation process. After the addition of TBA, TCM, and FFA, the degradation rate of TC decreases to 84.1% (14.9% of decrease), 81.3% (17.7% decrease), and 87.2% (11.8% decrease), respectively. This indicates that ·OH, O2·−, and 1O2 also exhibit certain inhibitory effects [50]. However, the addition of DMSO does not affect the TC degradation, indicating that high-valent iron (Fe(IV)) is not present as reactive species [51]. In summary, the results reveal that IO3· and IO4· are the dominant reactive species contributing to TC degradation in MIL-88A(Fe)/PI system, while ·OH, O2·−, and 1O2 also played secondary roles. In contrast, Fe(IV) played no significant role in the reaction.

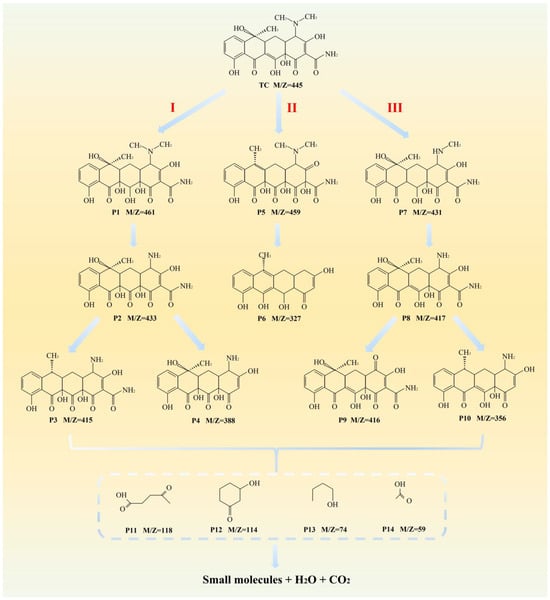

2.3.2. Degradation Pathways of TC

The TC degradation by-products in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system are analyzed by HPLC-MS, which identified 14 intermediates as detailed in Table S2. The results suggest three possible degradation pathways (Figure 8). In Pathway I, TC initially undergoes hydroxylation to form intermediate P1 (m/z = 461), followed by demethylation to generate P2 (m/z = 433). P2 can further degrade via two distinct branches: one involves dehydration reaction to form P3 (m/z = 415), and the other proceeds via a deamidation to yield P4 (m/z = 388). During these transformations, reactive species are likely involved in attacking C-C and C-O bonds, facilitating molecular cleavage and degradation. In Pathway II, TC is firstly oxidated into P5 (m/z = 459), then degrades through the loss of amino, hydroxyl, and dimethyl amino groups, yielding P6 (m/z = 327) [52]. In Pathway III, TC experiences two successive demethylation reactions to form P7 (m/z = 431) and P8 (m/z = 417). P8 is further converted to P9 (m/z = 416) via oxidation, or alternatively transformed into P10 (m/z = 356) through deamidation and dehydration reactions. With continued reaction progression, these intermediates are gradually decomposed into low-molecular-weight products, including P11 (m/z = 118), P12 (m/z = 114), P13 (m/z = 74) and P14 (m/z = 59), and are ultimately mineralized into CO2 and H2O [53]. These pathways demonstrate highly oxidative characteristics, indicating that reactive species in the reaction system induce deep molecular cleavage of TC, which leads to the formation of smaller organic fragments.

Figure 8.

Possible TC degradation pathways in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system.

2.3.3. Possible Mechanism

Based on the above experimental results and the analysis of TC degradation pathways, the proposed degradation mechanism of TC in the MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system is illustrated in Figure 9. Initially, PI molecules are adsorbed onto the surface of MIL-88A(Fe)-300, whose porous structure and high surface area can provide abundant active sites. Under reaction conditions, Fe3+/Fe2+ within the framework of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 participate in cyclic electron transfer, promoting the activation of PI and generating a large number of reactive species, including IO3· and IO4·, ·OH, O2·−, and 1O2. Quenching experiments identify IO3· and IO4· as the primary active species for TC degradation, while ·OH, O2·−, and 1O2 also make secondary contributions. Reactive species attack critical structural moieties of TC, such as the benzene ring, hydroxyl, methyl and amino groups, resulting in cleavage of the molecular backbone and ultimately mineralizing to CO2 and H2O [36,37]. Overall, the MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system facilitates the stepwise degradation and mineralization of TC through the synergistic effects of surface adsorption, Fe3+/Fe2+ redox cycling, and PI-activated reactive species generation.

Figure 9.

Mechanism of TC degradation in MIL-88A(Fe)-300/PI system.

3. Experimental Section

All chemicals are of analytical grade and can be used without further purification. The sources of all the chemicals used in the experiment are shown in Text S1.

3.1. Preparation of Catalysts

Typically, 1.352 g of FeCl3·6H2O (5 mmol) and 0.58 g of fumaric acid (C4H4O4, 5 mmol) are dissolved into deionized water (25 mL), and the mixture is evenly mixed by magnetic stirring for 30 min. Subsequently, the solution is transferred into a radiolysis-resistant container and exposed in the electron beam irradiation under different radiation dosages (300 kGy, 500 kGy, and 600 kGy) by using an electron beam irradiator. After irradiation, the suspension is centrifuge at 5000 rpm to collect the orange solid, washed successively by deionized water and ethanol, and dried in the oven at 65 °C for 12 h to obtain the catalyst, marked as MIL-88A(Fe)-X (X represents the radiation dosage, X = 300, 500, 600, respectively). The details on the electron beam irradiation are provided in Text S2.

3.2. Characterization

The catalysts are characterized using XRD, FT-IR, SEM, EDS, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and XPS. All the instruments and details are shown in Text S3.

3.3. Experimental Procedure

To investigate the performance of the catalyst, various parameters are systematically examined. Typically, the catalyst (20 mg) and PI (1.0 mM) are introduced into TC solution (10 mg/L). At designated time intervals, 1.5 mL samples are withdrawn from the reaction system and filtered by a 0.22 µm polyether sulfone filter, followed by mixing with 0.2 mL of Na2S2O3 (2.0 M) to quench the degradation reaction; then, the remaining concentration of TC is measured. Furthermore, the effects of catalyst dosage, PI concentration, temperature, TC concentration, pH, coexistence inorganic anions (Cl−, HCO3−, NO3−, H2PO4−, CO32−) and natural organic matter (humic acid, HA) on TC degradation are evaluated. In cycling experiments, the reacted catalyst is recovered through filtration, washing, drying, and grinding for reuse in subsequent cycles.

3.4. Analytic Methods

The concentration of TC is monitored by using an ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (UV-vis, UV-2600, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), and the detailed test procedure is presented in Texts S4. Quenching experiments are adopted to reveal the dominant active species in the TC degradation process. PhOH, TBA, DMSO, TCM and FFA are used as scavengers for IO3· and IO4·, ·OH, Fe(IV), O2·−, and 1O2, respectively. The decomposition products of TC are identified and quantified by a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer (LC-MS, 6545 Q-TOF LC/MS, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) system.

4. Conclusions

In summation, MIL-88A(Fe)-X (X = 300, 500, 600) was successfully synthesized via electron beam irradiation approach and applied as an efficient catalyst for PI activation to degrade TC. The catalyst prepared at 300 kGy of electron beam irradiation (MIL-88A(Fe)-300) exhibited excellent catalytic activity. Under optimal conditions (20 mg catalyst, 1.0 mM PI, 10 mg/L TC, pH 6.8, 25 °C), a high TC removal rate of 99.0% was achieved within 60 min. The system also demonstrated strong environmental adaptability, maintaining high performance over a wide pH range and in the presence of coexistence substances. Quenching experiments and mechanistic studies revealed that IO3· and IO4· played the dominant role in TC degradation, while ·OH, O2·−, and 1O2 made secondary contributions. The catalyst also showed excellent stability and reusability. This work provides a facile irradiation-assisted synthesis strategy for Fe-MOFs and elucidates the underlying periodate activation mechanism. It offers a practical and efficient catalytic system for antibiotic wastewater treatment and has great potential in industrial applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16010036/s1, Text S1: Chemicals; Text S2: Experimental operation of electron beam irradiation; Text S3: Characterizations of the catalysts; Text S4: TC concentration determination; Figure S1: XRD patterns (a) and FT-IR spectra (b) of MIL-88A(Fe)-300 before and after the reaction; Table S1: The specific surface area, total pore volume and average pore diameter of MIL-88A(Fe)-300; Table S2: Information of TC intermediates [54,55,56,57].

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, H.L. (Huanhuan Liang); conceptualization, investigation, J.W.; software, validation, H.L. (Hongying Lu); data curation, visualization, J.X.; formal analysis, resources, T.H.; writing—review and editing, funding acquisition and project administration, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was supported by the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2021-03-147), Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R & D Program (No. QKHZC-2024-152), Open Fund Program of Key Laboratory of Songliao Aquatic Environment, Ministry of Education, Jilin Jianzhu University (No. JLJUSLKF042024002) and State Key Laboratory of Water Pollution Control and Green Resource Recycling (No. PCRRF25049).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gao, M.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, H. Adsorption Behavior and Mechanism of Modified Fe-Based Metal–Organic Framework for Different Kinds of Arsenic Pollutants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 654, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.-T.; Bui, T.-T.-U.; Phan, A.-T.; Pham, T.-B. Boosting Tetracycline Degradation by Integrating MIL-88A (Fe) with CoFe2O4 Persulfate Activators. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, I.; Khanday, W.A. Recent Advances in Antibiotic Removal Methods from Wastewater: A Comprehensive Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 381, 135478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.-L.; Song, C.; He, L.-Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, F.-Z.; Zhang, M.; Ying, G.-G. Antibiotics in Soil and Water: Occurrence, Fate, and Risk. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 32, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Dai, W.; Quan, G.; Lei, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L. Three-Dimensional MIL-88A(Fe)-Derived α-Fe2O3 and Graphene Composite for Efficient Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Ciprofloxacin. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 111063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Tao, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Chen, Z.; He, X.; Luo, Y.; Yang, L. Fe-Mn Bimetallic Loaded Sludge Biochar as a Novel Periodate Activator for Sulfamethoxazole Removal: The Combination of Radical and Non-Radical Mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Guo, S.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Quan, G.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalysis of Ibuprofen by NH2 Modified MIL-53(Fe) Graphene Aerogel: Performance, Mechanism, Pathway and Toxicity Assessment. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 726, 137769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhuo, Y.; Huang, X.; Qin, T.; Peng, H.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Y. Applications of Periodate Activation for Emerging Contaminants Treatment in Water: Activation Methods, Reaction Parameters and Mechanism. Environ. Res. 2025, 271, 121088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, T.; Chen, H. Exploration of Low-Dose Ozone-Activated Periodate (O3/IO4−) for Rapid Degradation of the β-Blocker Pindolol: Efficiency and Radical Mechanism. Water Res. 2025, 285, 124116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhatskiy, Y.; Shepida, M.; Sozanskyi, M.; Znak, Z.; Gogate, P.R. Periodate-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 304, 122305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shao, Y.; Ji, W.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, D. Surface-Mediated Periodate Activation by Nano Zero-Valent Iron for the Enhanced Abatement of Organic Contaminants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendjama, H.; Merouani, S.; Hamdaoui, O.; Bouhelassa, M. Efficient Degradation Method of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Marine Environment Using UV/Periodate Process: Case of Chlorazol Black. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 126, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, R.; Ye, Y.; Ma, R.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Ni, B.-J. Sulfur-Decorated Fe/C Composite Synthesized from MIL-88A(Fe) for Peroxymonosulfate Activation towards Tetracycline Degradation: Multiple Active Sites and Non-Radical Pathway Dominated Mechanism. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Ding, Y.; Tang, Q.; Lian, F.; Bai, C.; Xie, R.; Xie, H.; Zhao, X. Plasmonic Ag Nanoparticles Decorated MIL-101(Fe) for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol A with Peroxymonosulfate under Visible-Light Irradiation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Ma, Y.; Han, T.; Quan, G.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. Treatment of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) Using Periodate-Based Advanced Oxidation Technology: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. In Situ Electronic Modulation of G-C3N4/UiO66 Composites via N Species Functionalized Ligands for Enhanced Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Feng, X.; Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; et al. Unveiling the Influence Mechanism of Impurity Gases on Cl-Containing Byproducts Formation during VOC Catalytic Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15526–15537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhou, D.; Tang, K.; Ma, Y.; Han, T.; Lei, J.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L.; et al. Electron Beam- Induced Defect Engineering Construction in MIL-68(In) for Enhanced CO2 Photoreduction: Unravelling Organic Framework Defects. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 702, 138990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Cui, H.; Tang, K.; Crawshaw, D.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L.; Liu, N. Highly Selective CO2 Conversion to CH4 by a N-Doped HTiNbO5/NH2-UiO-66 Photocatalyst without a Sacrificial Electron Donor. JACS Au 2025, 5, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channab, B.-E.; Ouardi, M.E.; Layachi, O.A.; Marrane, S.E.; Idrissi, A.E.; BaQais, A.; Ahsaine, H.A. Recent Trends on MIL-Fe Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis Approaches, Structural Insights, and Applications in Organic Pollutant Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 2957–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Lin, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, X.; Feng, M. Ferrate(VI)/Periodate System: Synergistic and Rapid Oxidation of Micropollutants via Periodate/Iodate-Modulated Fe(IV)/Fe(V) Intermediates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7051–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamedi, A.; Zarandi, M.B.; Nateghi, M.R. Highly Efficient Removal of Dye Pollutants by MIL-101(Fe) Metal-Organic Framework Loaded Magnetic Particles Mediated by Poly L-Dopa. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, P.A.; Mottillo, C.; Friščić, T. Metal–Organic Frameworks Meet Scalable and Sustainable Synthesis. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2729–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Martinez, M.; Avci-Camur, C.; Thornton, A.W.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D.; Hill, M.R. New Synthetic Routes towards MOF Production at Scale. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3453–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doustkhah, E.; Hassandoost, R.; Khataee, A.; Luque, R.; Assadi, M.H.N. Hard-Templated Metal–Organic Frameworks for Advanced Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2927–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamalzadeh, M.; Sobkowicz, M.J. Review of the Effects of Irradiation Treatments on Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 206, 110191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, J. Scalable Upgrading Metal–Organic Frameworks through Ambient and Controllable Electron-Beam Irradiation for CO2 Capture and Conversion. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 363, 132270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Li, F.; Tang, Z.; Wang, S.; Weng, K.; Liu, D.; Lu, S.; Liu, W.; Fu, Z.; Li, W.; et al. Crosslinking-Induced Patterning of MOFs by Direct Photo- and Electron-Beam Lithography. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Song, X.-X.; Wu, L.; Zhao, C.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.-C. Room-Temperature Preparation of MIL-88A as a Heterogeneous Photo-Fenton Catalyst for Degradation of Rhodamine B and Bisphenol a under Visible Light. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 125, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Zou, X.; Chen, D.; Chu, Z.; Hu, J.; Bentel, M.J.; Hao, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Hexagonal Prism-like Fe1−xS@SC Nanorod Derived from MIL-88A (Fe) as Peroxydisulfate Activator for Tetracycline Degradation: Performance and Mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 335, 125962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yang, J.; Luan, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, C. MIL-88A(Fe) Modified Carriers Induced Iron Autotrophic Denitrification in Intermittently-Aerated MBBR for Low C/N Wastewater Treatment. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2025, 198, 106009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Zhang, S.; Xu, K.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X. Synergistic Effects of Adsorption and Photocatalysis in MIL-88A(Fe) Catalyst for Remediation of Phenanthrene-Contaminated Saline-Alkaline Soils. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2025, 689, 120010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Tang, K.; Wang, D.; Fei, F.; Cui, H.; Li, F.; Lei, J.; Crawshaw, D.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L. Enhanced Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Integrating an Iron Based Metal-Organic Framework and a Photosensitizer. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 332, 125873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, L.; Tang, M.; Ge, M. Activation of Peroxydisulfate by MIL-88A(Fe) under Visible Light toward Tetracycline Degradation: Effect of Synthesis Temperature on Catalytic Performance. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 323, 124051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Jiang, H.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X. LaFeO3 Anchoring on ZIF-67 for the Activation of Peroxymonosulfate toward Ofloxacin Degradation: Radical and Non-Radical Reaction Pathways. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Chen, Q.; Qiu, J.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Yu, J.C.; Wu, L. Cu Mediated Defect Manipulation in MIL-88A(Fe) for Boosting Photocatalytic N2 Fixation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 692, 137504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, S.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, M. Enhanced Tetracycline Elimination through Periodate Activation via Biochar-Loaded Crystallographic Manganese Dioxide –Electron Transfer Mechanism Facilitated by Oxygen Vacancies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L. Structure–Activity Relationship in Periodate Activation by Fe-MOFs: Why MIL-101(Fe) Outperforms Other MIL-Series in Antibiotic Degradation. Green Energy Environ. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiao, G.; Sheng, G.; Lin, N.; Yang, B.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Microwave-Assisted PMS Activation Ti3C2/LaFe0.5Cu0.5O3-P Catalysts for Efficient Degradation of CIP: Enhancement of Catalytic Performance by Phosphoric Acid Etching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Sun, Y.; Dong, H.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y.; Ao, Z.; Guan, X. Understanding the Importance of Periodate Species in the pH-Dependent Degradation of Organic Contaminants in the H2O2/Periodate Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10372–10380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, W.; Jiao, G.; Wang, J.; Gong, Y.; Yin, Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X. Boosting Catalytic Activity of Fe-Based Perovskite by Compositing with Co Oxyhydroxide for Peroxymonosulfate Activation and Ofloxacin Degradation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 705, 135706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H. Natural Fe-Bearing Manganese Ore Facilitating Bioelectro-Activation of Peroxymonosulfate for Bisphenol A Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 1120–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Ren, X.; Yang, M.; Guo, W. Facet-Controlled Activation of Persulfate by Magnetite Nanoparticles for the Degradation of Tetracycline. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 258, 118014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Li, K.; Huo, W.; Wei, H.; Jiang, H.-Y. 2,3-Pyridinedicarboxylic Acid-Modified MIL-88A(Fe) for Enhanced Peroxymonosulfate Activation to Degrade Organic Contaminants. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 65, 105779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; Zeng, H.; Shi, Z.; Wu, H.; Deng, L. Novel Sulfur Vacancies Featured MIL-88A(Fe)@CuS Rods Activated Peroxymonosulfate for Coumarin Degradation: Different Reactive Oxygen Species Generation Routes under Acidic and Alkaline pH. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 166, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Du, L.; Jin, J.; Meng, H.; Mi, J. In Situ Growth of MIL-88A into Polyacrylate and Its Application in Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Water. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 564, 150404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, C.; Chunrui, Z.; Li, T.; Jiang, J.; Han, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sun, H.; Dong, S. Citric Acid-Modified MIL-88A(Fe) for Enhanced Photo-Fenton Oxidation in Water Decontamination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 308, 122945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumeh, G.; Babak, K.; Mehdi, A.; Minoo, A. Photocatalytic Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by TiO2 Anchored on Cupper Ferrite (TiO2@CuFe2O4) into 2,4-D Degradation: Process Feasibility, Mechanism and Pathway. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 359, 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin Simsek, E.; Tuna, Ö. Unravelling the Synergy of Ce Dopant and Surface Oxygen Vacancies Confined in FeTiO3 Perovskite for Peroxymonosulfate Activated Degradation of Wide Range of Pollutants. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 176, 111276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Cui, L.; Xu, H.; Gong, C. Selective Dissolution of A-Site Cations of La0.6Sr0.4Co0.8Fe0.2O3 Perovskite Catalysts to Enhance the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 529, 147165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Zhou, Z.; He, M.; Ouyang, W. Catalytic Oxidation of Contaminants by Fe0 Activated Peroxymonosulfate Process: Fe(IV) Involvement, Degradation Intermediates and Toxicity Evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 123013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Su, J.; Huang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. Biocrystal-Encased Manganese Ferrite Coupling with Peroxydisulfate: Synergistic Mechanism of Adsorption and Catalysis towards Tetracycline Removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Qian, J.; Xue, B.; Du, H.; Hao, D.; Ji, Y.; Li, Q. Ti3C2-Assisted Construction of Z-Scheme MIL-88A(Fe)/Ti3C2/RF Heterojunction: Multifunctional Photocatalysis-in-Situ-Self-Fenton Catalyst. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 190, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, H.; Xie, J.; Teng, G.; He, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, C. A Photocatalyst Combined of Copper Doped ZnO and Graphdiyne (Cu/ZnO@GDY) for Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline: Mechanism and Application. Water Res. 2025, 278, 123345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Yang, S.; Guo, C.; DuBois, D.; Chen, S.; Meng, F. Bubble-Triggered Piezocatalytic Generation of Hydrogen Peroxide by Copper Nanosheets-Modified Polyvinylidene Fluoride Films for Organic Pollutant Degradation and Water Disinfection. Water Res. 2025, 283, 123865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.D.; Wang, J.H.; Feng, Y.J.; Feng, K.M.; Yang, J.J.; Liao, J.L.; Yang, Y.Y.; Liu, N. The Effect of Electron Irradiation and Post-Irradiation Annealing on α-Al2O3 Coating Prepared by MOD Method. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2017, 406, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazirov, R.A.; Shkuro, A.E.; Buryndin, V.G.; Zakharov, P.S.; Shishlov, O.F.; Vazirova, E.N. The Effect of High-Energy Electron Beam Irradiation on the Physicochemical Properties of PET Material. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 227, 112392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.