Enhancing Thermal Uniformity and Ventilation Air Methane Conversion in Pilot-Scale Regenerative Catalytic Oxidizers via CFD-Guided Structural Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalytic Reaction Kinetics

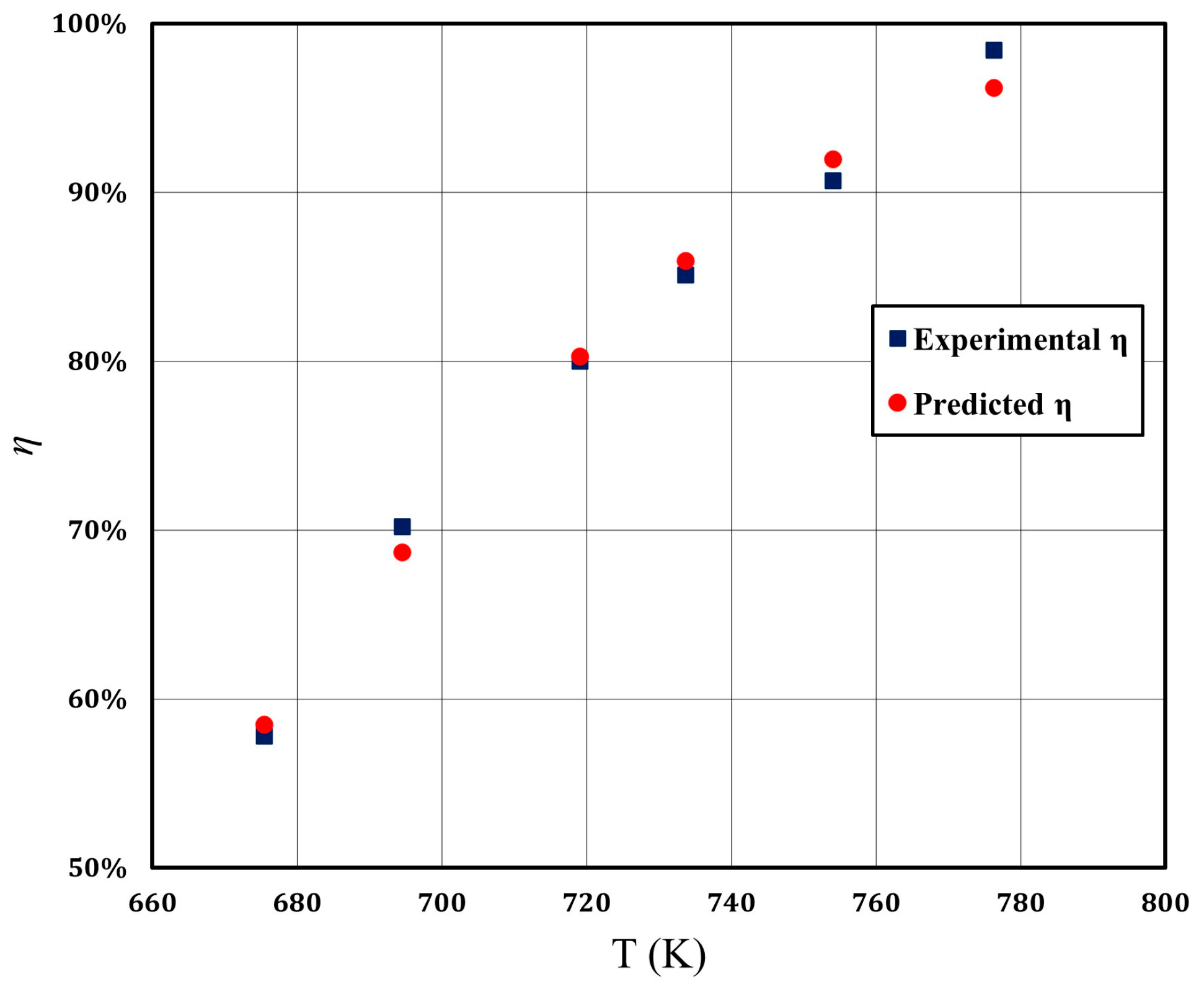

2.2. Validation of the Coupled Model

2.3. Structural Optimization of the Pilot-Scale RCO System

2.3.1. Increasing the Number and Adjusting the Position of Heating Rods

2.3.2. Introducing a Gas Distribution Plate

2.4. Structural Modification of the Pilot-Scale RCO System

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Setup of Catalytic Reaction Kinetics

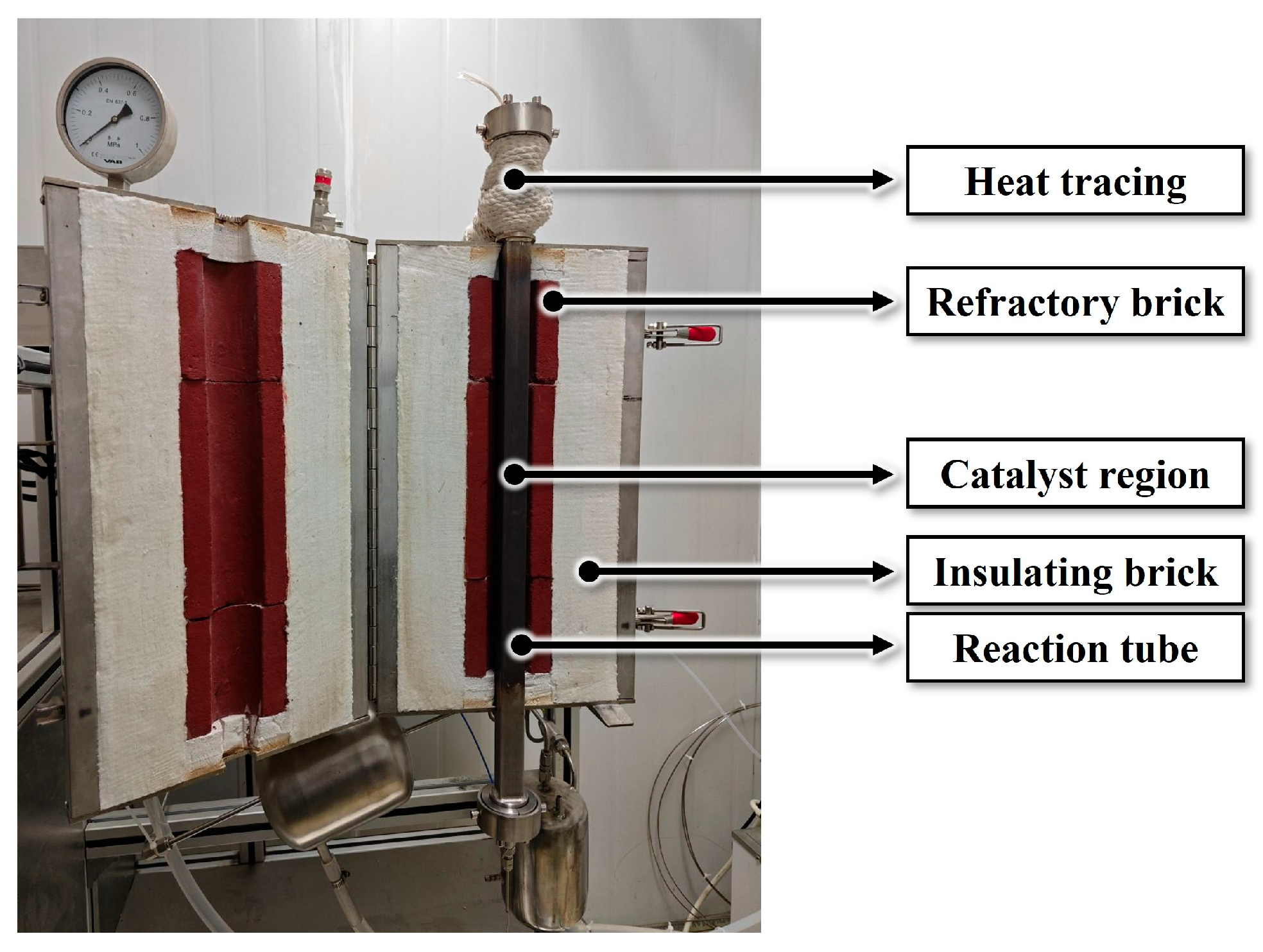

3.2. Experimental Setup of Pilot-Scale RCO

3.3. Simulation Setup

4. Conclusions

- 1.

- Heating rod reconfiguration: The orientation of the heating rods was changed from parallel to perpendicular relative to the airflow direction. This adjustment enhanced the interaction between the incoming air and the heat source, resulting in more uniform preheating across the cross-section. Consequently, the temperature uniformity index improved from 0.5462 to 0.8304.

- 2.

- Introduction of a gas distribution plate: To further enhance mixing, a flow distribution plate was installed upstream of the catalyst bed. This modification significantly increased turbulence intensity, promoting better mixing of hot and cold air streams. As a result, the temperature field became even more homogeneous, with the uniformity index rising to 0.9785.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VAM | Ventilation air methane |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| RCO | Regenerative catalytic oxidizer |

| RTO | Regenerative thermal oxidizer |

| GHSV | Gas hourly space velocity |

References

- World Meteorological Organization. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 52, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Karakurt, I.; Aydin, G.; Aydiner, K. Mine ventilation air methane as a sustainable energy source. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Lu, B.; Qi, J.; Li, Z.; Han, J.; Yan, Y. Self-supporting characteristics in hierarchical monolith catalyst with highly accessible active sites for boosting lean methane catalytic oxidation. Fuel 2026, 405, 136576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, X.; Han, J.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y. Trend model and key technologies of coal mine methane emission reduction aiming for the carbon neutralit. J. China Coal Soc. 2022, 47, 470–479. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Dai, E.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F. Methane fugitive emissions from coal mining and post-mining activities in China. Res. Sci. 2020, 42, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Chen, H.; Teakle, P.; Xue, S. Characteristics of coal mine ventilation air flows. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiruvenkatachari, R.; Su, S.; Yu, X. Carbon fibre composite for ventilation air methane (VAM) capture. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Beath, A.; Guo, H.; Mallett, C. An assessment of mine methane mitigation and utilisation technologies. Prog. Energ. Combust. Sci. 2005, 31, 123–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yang, K.; Zhu, Q.; Li, J.; Qi, J.; Wang, H. Lattice distortion in Co3O4/Mn3O4-guided synthesis via carbon nanotubes for efficient lean methane combustion. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, R.; Yang, L.; Ge, J.; Hu, F.; Zhang, T.; Lu, F.; Wang, H.; Qi, J. In situ growth of Mn-Co3O4 on mesoporous ZSM-5 zeolite for boosting lean methane catalytic oxidation. Catalysts 2024, 14, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qiu, R.; Li, C.; Zhong, R.; Wang, H.; Qi, J. Advancing catalytic oxidation of lean methane over cobalt-manganese oxide via a phaseengineered amorphous/crystalline interface. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 8896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Ye, F.; Zhang, N.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Dai, S.; Zhan, W. Synergistic effect of bimetallic RuPt/TiO2 catalyst in methane combustion. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Z.; Yang, K.; Zhong, R.; Wang, H.; Qi, J. Deep understanding the formation of MnCoOx in-situ grown on foam nickel towards efficient lean methane catalytic oxidation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 694, 134145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wei, R.; Zhu, Q.; Fu, Z.; Zhong, R.; Wang, H.; Qi, J. ZIF-67-derived hollow dodecahedral Mn/Co3O4 nanocages with enrichment effect and good mass transfer for boosting low temperature catalytic oxidation of lean methane. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Fan, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W. Experimental study on ultra-low concentration methane regenerative thermal oxidation. Energies 2024, 17, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, P.; Vega, A.; Díez, F.; Ordóñez, S. Control of regenerative catalytic oxidizers used in coal mine ventilation air methane exploitation. Process Saf. Environ. 2020, 134, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X. Improvement and application of regenerative thermal oxidizer. J. Environ. Eng. 2011, 5, 1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, K.; Fujita, S.; Iijima, S.; Nishimura, I.; Shimota, H.; Katagiri, T. Combustion and decomposition of VOCs from shell moulds by regenerative thermal oxidiser. Int. J. Cast Metal. Res. 2008, 21, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lin, J.; Branch, T. Analysis on feasibility of treating coated organic waste gas with regenerative thermal oxidizer. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2016, 41, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, G.; Kaisare, N.; Pushpavanam, S.; Ramanathan, K. Modeling the effect of flow mal-distribution on the performance of a catalytic converter. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 71, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pan, W.; Dai, G. A CFD–based design scheme for the perforated distributor with the control of radial flow. AIChE J. 2020, 66, e16901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, N. Experiment on the effect of Pt-catalyst on the characteristics of a small heat-regenerative CH4–air premixed combustor. Appl. Energ. 2010, 87, 3409–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, T.; Guo, C.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, S.; Guo, C. Thermal analysis and optimization of high-power beam deposition target cooling heat sink for accelerator radioisotopes application. Heat Transf. Res. 2021, 52, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Liang, C. Heat transfer characteristics of R134a vapor flow in a rectangular channel under vibration conditions. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2025, 39, 2929–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cao, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Ge, X.; Luo, J. Simulation analysis of gas–liquid flow and mass transfer in a shaking triethylene glycol dewatering absorber. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2024, 11, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, N.; Kanniche, M.; Neveux, T.; Potier, O. Numerical simulation of hydrodynamics in wet cooling tower packings. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 153, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Jalali, P. Solid-solid drag for continuum models using CFD-DEM simulations in gas fluidized beds of bidisperse mixtures. Powder Technol. 2025, 469, 121785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yuan, X.; Wang, P.; Xu, S.; Zhao, H.; Xue, J.; Li, Q. CFD and machine learning-based multi-objective optimization for structured packing design. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 320, 122483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, D.; Mao, M.; Chen, S.; Zheng, B.; Meng, J. Numerical simulation and optimization of diversion system in a preheating catalytic monolithic reactor. J. China Coal Soc. 2013, 38, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Numerical simulation of a regenerative thermal oxidizer for volatile organic compounds treatment. Environ. Eng. Res. 2018, 23, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlaczyk, A.; Gosiewski, K. Simplified kinetic model for thermal combustion of lean methane–air mixtures in a wide range of temperatures. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2013, 11, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlaczyk, A.; Gosiewski, K. Combustion of lean methane–air mixtures in monolith beds: Kinetic studies in low and high temperatures. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 282, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature (°C) | Conversion Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| 402.3 | 57.8 |

| 421.4 | 70.2 |

| 445.9 | 80.0 |

| 460.5 | 85.1 |

| 480.9 | 90.7 |

| 503.1 | 98.4 |

| Catalytic Layer A | Catalytic Layer B | Switchover Duration | Input Concentration | Output Concentration | Conversion Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 413 °C | 408 °C | 120 s | 0.26% | 0.05% | 81% |

| 328 °C | 512 °C | 120 s | 0.26% | 0.04% | 85% |

| 451 °C | 624 °C | 120 s | 0.26% | 0.03% | 88% |

| 587 °C | 674 °C | 120 s | 0.26% | 0.02% | 95% |

| Porous Region | Density [kg/m3] | Specific Heat Capacity [J/(kg·K)] | Thermal Conductivity [W/(m·K)] | Porosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | 2500 | 850 | 1.3 | 62% |

| Ceramic regenerator | 2150 | 1050 | 1.75 | 40% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Qi, J. Enhancing Thermal Uniformity and Ventilation Air Methane Conversion in Pilot-Scale Regenerative Catalytic Oxidizers via CFD-Guided Structural Optimization. Catalysts 2026, 16, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010038

Xu X, Liu W, Wang Y, Cheng Q, Wang Q, Li Z, Qi J. Enhancing Thermal Uniformity and Ventilation Air Methane Conversion in Pilot-Scale Regenerative Catalytic Oxidizers via CFD-Guided Structural Optimization. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xin, Wenge Liu, Yong Wang, Quanzhong Cheng, Qingxiang Wang, Zhi Li, and Jian Qi. 2026. "Enhancing Thermal Uniformity and Ventilation Air Methane Conversion in Pilot-Scale Regenerative Catalytic Oxidizers via CFD-Guided Structural Optimization" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010038

APA StyleXu, X., Liu, W., Wang, Y., Cheng, Q., Wang, Q., Li, Z., & Qi, J. (2026). Enhancing Thermal Uniformity and Ventilation Air Methane Conversion in Pilot-Scale Regenerative Catalytic Oxidizers via CFD-Guided Structural Optimization. Catalysts, 16(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010038