Sequential Multilayer Design with SnO2-Layer Decoration for Inhibiting Photocorrosion of Cu2O Photocathode

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

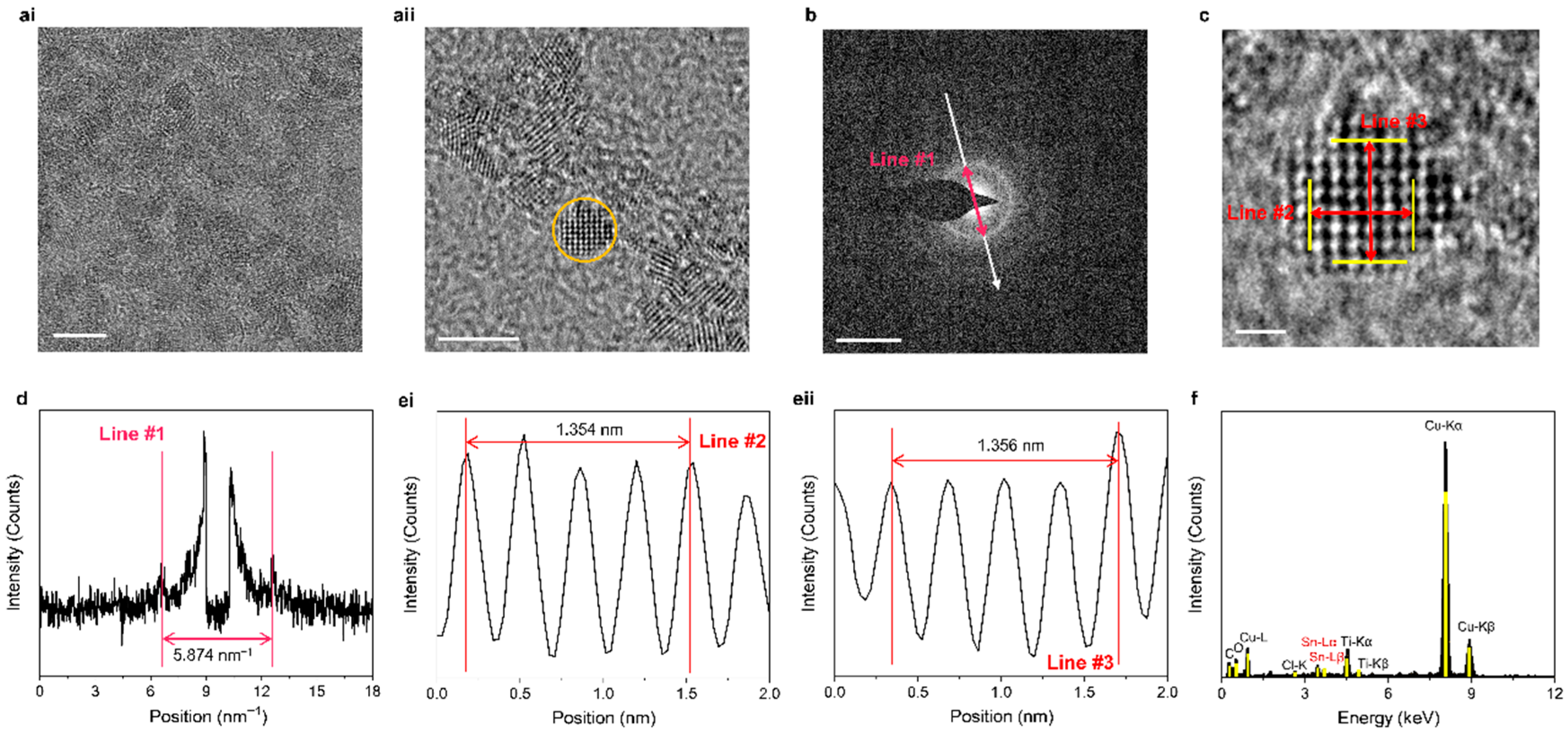

2.1. Observation of SnO2 QDs

2.2. Determination of Multilayer Design

2.3. Functions of SnO2 Layer Decoration

3. Experimental Procedures

3.1. Preparation of Samples

3.2. Characterizations

3.3. Photoelectrochemical Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Almeida, J.C.; Wang, Y.; Rodrigues, T.A.; Nunes, P.H.H.; de Mendonça, V.R.; Falsetti, P.H.E.; Savazi, L.V.; He, T.; Bardakova, A.V.; Rudakova, A.V.; et al. Copper-based materials for photo and electrocatalytic process: Advancing renewable energy and environmental applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2502901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Delaunay, J.-J. Earth-abundant Cu-based metal oxide photocathodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3269–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal, I.V.; Chodankar, N.R.; Hassan, M.A.; Waseem, A.; Johar, M.A.; Kim, D.-H.; Ryu, S.-W. Cu2O as an emerging photocathode for solar water splitting—A status review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 21351–21378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, M.K.; Kim, J. Revolutionary advancements in carbon dioxide valorization via metal-organic framework-based strategies. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rej, S.; Bisetto, M.; Naldoni, A.; Fornasiero, P. Well-defined Cu2O photocatalysts for solar fuels and chemicals. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 5915–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitopi, S.; Bertheussen, E.; Scott, S.B.; Liu, X.; Engstfeld, A.K.; Horch, S.; Seger, B.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Chan, K.; Hahn, C.; et al. Progress and perspectives of electrochemical CO2 reduction on copper in aqueous electrolyte. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 7610–7672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B.K.; Polity, A.; Reppin, D.; Becker, M.; Hering, P.; Klar, P.J.; Sander, T.; Reindl, C.; Benz, J.; Eickhoff, M.; et al. Binary copper oxide semiconductors: From materials towards devices. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 2012, 249, 1487–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.-K. Key strategies on Cu2O photocathodes toward practical photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselman, K.P.; Marin, A.; Schmidt-Mende, L.; MacManus-Driscoll, J.L. Incompatible length scales in nanostructured Cu2O solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 2202–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paracchino, A.; Brauer, J.C.; Moser, J.-E.; Thimsen, E.; Graetzel, M. Synthesis and characterization of high-photoactivity electrodeposited Cu2O solar absorber by photoelectrochemistry and ultrafast spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 7341–7350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.-K.; Pan, L.; Mayer, M.T.; Hagfeldt, A.; Grätzel, M.; Luo, J. Structural and compositional investigations on the stability of cuprous oxide nanowire photocathodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 55080–55091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, L.-W. Thermodynamic oxidation and reduction potentials of photocatalytic semiconductors in aqueous solution. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 3659–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, S.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Ruan, W.; Chen, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Liu, H.; et al. Rapid Charge Extraction via Hole and Electron Transfer Layers on Cu2O Photocathode for Stable and Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Reduction. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e09030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T.; Miyata, T.; Nishi, Y. Cu2O-based heterojunction solar cells with an Al-doped ZnO/oxide semiconductor/thermally oxidized Cu2O sheet structure. Sol. Energy 2014, 105, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paracchino, A.; Laporte, V.; Sivula, K.; Grätzel, M.; Thimsen, E. Highly active oxide photocathode for photoelectrochemical water reduction. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendula, P.; Mayer, M.T.; Luo, J.; Grätzel, M. Elucidation of photovoltage origin and charge transport in Cu2O heterojunctions for solar energy conversion. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 2633–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hisatomi, T.; Watanabe, O.; Nakabayashi, M.; Shibata, N.; Domen, K.; Delaunay, J.-J. Positive onset potential and stability of Cu2O-based photocathodes in water splitting by atomic layer deposition of a Ga2O3 buffer layer. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripala, W.; Ivanovskaya, A.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Baeck, S.-H.; McFarland, E.W. A Cu2O/TiO2 heterojunction thin film cathode for photoelectrocatalysis. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2003, 77, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shi, H.; Chen, R.; Ji, M.; Li, K.; Wang, H.; Jiang, X.; Lu, C. The Construction of p/n-Cu2O Heterojunction Catalysts for Efficient CO2 Photoelectric Reduction. Catalysts 2023, 13, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.; Tilley, S.D. Photovoltaic and photoelectrochemical solar energy conversion with Cu2O. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 26243–26257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, M.; Song, Y. Band alignment at the Cu2O/ZnO heterojunction. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 50, 51002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wi, D.H.; Lumley, M.A.; Xi, Z.; Liu, M.; Choi, K.-S. Investigation of electron extraction and protection layers on Cu2O photocathodes. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 4385–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Kim, J.H.; Mayer, M.T.; Son, M.-K.; Ummadisingu, A.; Lee, J.S.; Hagfeldt, A.; Luo, J.; Grätzel, M. Boosting the performance of Cu2O photocathodes for unassisted solar water splitting devices. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, S.D.; Schreier, M.; Azevedo, J.; Stefik, M.; Graetzel, M. Ruthenium oxide hydrogen evolution catalysis on composite cuprous oxide water-splitting photocathodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Kim, Y.B.; Choi, J.H.; Suh, H.W.; Lee, H.H.; Lee, K.W.; Jung, S.H.; Kim, J.J.; Deshpande, N.G.; Cho, H.K. Toward simultaneous achievement of outstanding durability and photoelectrochemical reaction in Cu2O photocathodes via electrochemically designed resistive switching. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Kumar, R.; Sun, J. Cu2O/ZnO p–n junction decorated with NiOx as a protective layer and cocatalyst for enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 10408–10414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanur, S.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Seo, H. Enhanced and stable photoelectrochemical H2 production using a engineered nano multijunction with Cu2O photocathode. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 26, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Su, K.; Liu, M.; Gao, J.; He, J.; Feng, D. Constructing p–n interfaces to accelerate carrier separation in a Cu2O photocathode through an in situ thermal oxidation method for highly active photoelectrochemical properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 6610–6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.; Ananthoju, B.; Dhara, A.K.; Aslam, M.; Sarkar, S.K.; Balasubramaniam, K.R. Electron-selective TiO2/CVD-graphene layers for photocorrosion inhibition in Cu2O photocathodes. Adv. Mater. Inter. 2017, 4, 1700271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbovskii, D.S.; Kapitanova, O.; Xu, X.; Panin, G.N.; Baranov, A.N. Cu2O photocathodes modified by graphene oxide and ZnO nanoparticles with improved photocatalytic properties. Langmuir 2023, 39, 18509–18517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Guio, C.G.; Liardet, L.; Mayer, M.T.; Tilley, S.D.; Grätzel, M.; Hu, X. Photoelectrochemical hydrogen production in alkaline solutions using Cu2O coated with earth-abundant hydrogen evolution catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 664–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamal, S.; Maity, A.; Satpati, A.K.; Bhattacharya, C. Amplification of PEC hydrogen production through synergistic modification of Cu2O using cadmium as buffer layer and dopant. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 246, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Z. FeOOH as hole transfer layer to retard the photocorrosion of Cu2O for enhanced photoelctrochemical performance. Appl. Catal. B 2020, 260, 118213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Qin, C.; Lou, Z.-R.; Lu, Y.-F.; Zhu, L.-P. Cu2O photocathodes for unassisted solar water-splitting devices enabled by noble-metal cocatalysts simultaneously as hydrogen evolution catalysts and protection layers. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 495407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinke, M.; Kuzminykh, Y.; Hoffmann, P. Surface reaction kinetics of titanium isopropoxide and water in atomic layer deposition. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 4337–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paracchino, A.; Mathews, N.; Hisatomi, T.; Stefik, M.; Tilley, S.D.; Grätzel, M. Ultrathin films on copper(i) oxide water splitting photocathodes: A study on performance and stability. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Chen, Q.; Li, L. Modification engineering in SnO2 electron transport layer toward perovskite solar cells: Efficiency and stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, T.; Li, J.; Zheng, F.; Chen, W.; Wen, X.; Ku, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhong, J.; Cheng, Y.-B.; Huang, F. Universal passivation strategy to slot-die printed SnO2 for hysteresis-free efficient flexible perovskite solar module. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; He, Z.; Zeng, K.; Liu, A.; Jiang, F.; Ma, T. Ultralow-temperature SnO2 electron transport layers fabricated by intermediate-controlled chemical bath deposition for highly efficient perovskite solar cells. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202300765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Xia, Y.; Ran, X.; Li, P.; Zhong, Q.; Song, L.; Müller-Buschbaum, P.; et al. Manipulating SnO2 growth for efficient electron transport in perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. Inter. 2021, 8, 2100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.; Tilley, S.D.; Schreier, M.; Stefik, M.; Sousa, C.; Araújo, J.P.; Mendes, A.; Grätzel, M.; Mayer, M.T. Tin oxide as stable protective layer for composite cuprous oxide water-splitting photocathodes. Nano Energy 2016, 24, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jeong, J.; Lu, H.; Lee, T.K.; Eickemeyer, F.T.; Liu, Y.; Choi, I.W.; Choi, S.J.; Jo, Y.; Kim, H.-B.; et al. Conformal quantum dot-SnO2 layers as electron transporters for efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 2022, 375, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, C.; Yao, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Ma, J.; Lei, H.; Qin, P.; Xiong, L.; et al. Effective carrier-concentration tuning of SnO2 quantum dot electron-selective layers for high-performance planar perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1706023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Ye, F.; Ma, J.; Zheng, X.; Gui, P.; Xiong, L.; Wen, J.; Fang, G. A facile room temperature solution synthesis of SnO2 quantum dots for perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 10636–10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Moehl, T.; Adams, P.; Zhang, X.; Lefèvre, R.; Cruz, A.M.; Zeng, P.; Kunze, K.; Yang, W.; Tilley, S.D. Crystal orientation-dependent etching and trapping in thermally-oxidised Cu2O photocathodes for water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Tsui, L.; Swami, N.; Zangari, G. Photoelectrochemical stability of electrodeposited Cu2O films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 11551–11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Dai, L.; Burton, O.J.; Chen, L.; Andrei, V.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, D.; Cheng, J.; Wu, L.; Frohna, K.; et al. High carrier mobility along the [111] orientation in Cu2O photoelectrodes. Nature 2024, 628, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Wang, C.; Gu, C.; Li, C.; Yin, H.; Yan, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, S.X.-A. An electrochemically responsive B-O dynamic bond to switch photoluminescence of boron-nitrogen-doped polyaromatics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Lee, D.; Choi, K.-S. Electrochemical synthesis of highly rriented, transparent, and pinhole-free ZnO and Al-Doped ZnO films and their use in heterojunction solar cells. Langmuir 2016, 32, 10459–10466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illy, B.N.; Cruickshank, A.C.; Schumann, S.; Da Campo, R.; Jones, T.S.; Heutz, S.; McLachlan, M.A.; McComb, D.W.; Riley, D.J.; Ryan, M.P. Electrodeposition of ZnO layers for photovoltaic applications: Controlling film thickness and orientation. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 12949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ichimura, M. Improvement of electrochemically deposited Cu2O/ZnO heterojunction solar cells by modulation of deposition current. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 51, 10NC39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Pan, L.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, J.; Mensi, M.; Sivula, K.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Ren, D.; Grätzel, M. Efficient Cu2O photocathodes for aqueous photoelectrochemical CO2 reduction to formate and syngas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 27939–27949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, B.; Hui, W.; Su, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.-H.; Gao, X.; et al. Oxygen vacancy mediation in SnO2 electron transport layers enables efficient, stable, and scalable perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 19108–19117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, J.; Takagi, K.; Wei, Z.; Motodate, M.; Chi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Terashima, C.; Shangguan, W.; Fujishima, A. Sequential Multilayer Design with SnO2-Layer Decoration for Inhibiting Photocorrosion of Cu2O Photocathode. Catalysts 2026, 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010037

Yan J, Takagi K, Wei Z, Motodate M, Chi J, Zhu Y, Terashima C, Shangguan W, Fujishima A. Sequential Multilayer Design with SnO2-Layer Decoration for Inhibiting Photocorrosion of Cu2O Photocathode. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Jiawei, Kai Takagi, Zhidong Wei, Masaya Motodate, Jiasheng Chi, Yong Zhu, Chiaki Terashima, Wenfeng Shangguan, and Akira Fujishima. 2026. "Sequential Multilayer Design with SnO2-Layer Decoration for Inhibiting Photocorrosion of Cu2O Photocathode" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010037

APA StyleYan, J., Takagi, K., Wei, Z., Motodate, M., Chi, J., Zhu, Y., Terashima, C., Shangguan, W., & Fujishima, A. (2026). Sequential Multilayer Design with SnO2-Layer Decoration for Inhibiting Photocorrosion of Cu2O Photocathode. Catalysts, 16(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010037