Abstract

CO2 methanation offers a promising technology to convert CO2 into methane, a valuable fuel that can be integrated into existing gas infrastructure. However, developing cost-effective, highly active, and stable catalysts remains a key challenge. In this paper, a series of La/NiAl-LDO catalysts were synthesized via a coprecipitation–impregnation method for catalytic CO2 hydrogenation. Among the prepared catalysts, 6La/NiAl-LDO exhibited the highest CO2 conversion (85.6%) with nearly 100% CH4 selectivity at 300 °C and 2 MPa. The catalyst also demonstrated excellent stability over a 100 h durability test. Moreover, the kinetics of CO2 hydrogenation over a 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst were studied in a fixed-bed reactor at a catalyst particle size of 20–40 mesh, space velocity of 8000 mL/(g·h)), and temperatures ranging from 260 to 300 °C. The overall positive reaction followed approximately first-order kinetics, with an apparent activation energy of 89.4 kJ/mol. This work contributes to broader efforts in CO2 capture and conversion to synthetic natural gas.

1. Introduction

Rising global energy demand, coupled with the combustion of vast fossil fuel resources, has led to excessive emissions of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, causing environmental pollution, climate change, global warming, and energy shortages [1,2]. As a major global carbon-emitting country, we should take active measures to achieve the “Dual Carbon” goals—peaking carbon emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060—in response to global climate change [3]. Therefore, the urgent need to address the global climate crisis requires both reducing CO2 emissions and finding ways to reuse CO2. For carbon emission reduction, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) has gained widespread attention. Building upon this, the concept of resource utilization has been introduced, leading to Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS). This approach involves channeling captured CO2 into value-added chemicals such as methane or methanol for recycling and reuse, thereby achieving CO2 resource utilization [4]. Among the different methods used, CO2 methanation offers a promising solution by converting CO2 into methane, which is a high-energy fuel that can be integrated into existing gas infrastructure [5,6]. This approach supports clean and efficient carbon utilization, stores renewable energy, and contributes to a circular carbon economy, demonstrating significant potential for industrial application [7,8].

The CO2 methanation reaction is highly exothermic (ΔH(298K) = −164 kJ/mol) and while thermodynamically favorable at low temperatures, it requires efficient catalysts to overcome its kinetic limitations and enhance the reaction rate [9]. It is thus imperative to develop catalysts that exhibit high activity, selectivity, and stability under operational conditions. Both ruthenium (Ru) and nickel (Ni) serve as prominent active components in catalysts [10,11]. Ru catalysts show exceptional low-temperature activity but are excessively costly for industrial scaling [12,13]. On contrary, Ni-based catalysts have attracted considerable interest for their favorable combination of low cost, high activity, good selectivity, and easily controllable reaction conditions. However, they are limited by poor low-temperature performance and deactivation at high temperatures [14]. Takenaka et al. prepared Ni-based catalysts using MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, TiO2, and ZrO2 as supports and evaluated their methanation performance. The results indicated that Ni/ZrO2 exhibited best methanation performance. While after high-temperature calcination, it readily forms NiAl2O4 spinel, which reduces the reducibility of nickel and lead to the catalyst becoming inactive due to carbon deposition [15]. In order to overcome these difficulties, the incorporation of other metal additives improves the reducibility of metals and thereby boosts catalyst performance. These metal additives are generally alkaline earth metal oxides, such as Na2O [16], CaO [17], K2O [18], MgO [19], and La2O3 [20], which improve the dispersion of Ni, thereby increasing surface oxygen vacancies, enhancing the strength and population of medium-strength basic sites, and ultimately lowering the reduction temperature of Ni. Tang et al. used a Ce-Metal–Organic Framework (Ce-MOF) precursor to create a Ni/CeO2 catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation to methane through a one-pot impregnation method; their results showed that under the optimal test conditions such as 0.2 g catalyst, 350 °C, 0.1 MPa, CO2:H2 molar ratio of 1:4, total gas flow of 150 mL·min−1, and a space velocity of 45,000 mL/(gcat·h), the CO2 conversion reached 82%, with nearly 100% selectivity for CH4 [21]. Especially, La doping has been identified as a simple way to conform uniform to increase the stability of the conventional Ni-based catalysts, thereby enhancing the CO2 methanation efficiency at low–intermediate temperatures [22]. Hu et al. investigated La-doped Ni/ZrO2 catalysts for CO2 methanation. According to H2-TPR characterization, the Ni-La/ZrO2 catalyst showed a low-temperature reduction peak at about 350 °C, corresponding to NiO. This improvement in reducibility allowed the catalyst to achieve high CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity at low temperatures [23].

Conventional supports for CO2 methanation catalysts include metal oxides (e.g., Al2O3, SiO2, ZrO2, TiO2, and CeO2), along with zeolites, layered double oxide (LDO) nanosheets, and MOFs [24,25]. Amongst them, LDOs, derived from the calcination of layered double hydroxides (LDHs), have emerged as a cost-effective, high-specific-surface-area supports for catalyst active components or catalysts [26,27]. Generally, the LDH chemical formula is represented as [(M2+)1−x (M3+)x(OH)2](An−)x/n·mH2O, where M is a metal and A is an anion. The divalent cations M2+ can be Ni2+ and/or another one, while the trivalent cation M3+ can be Al3+ and/or something else [28]. The mole ratio of M2+/M3+ typically ranges from 1:1 to 4:1. Minh Nguyen-Quang prepared a NiMgAl-LDO catalyst via the co-precipitation and impregnation method for CO2 hydrogenation; the CO2 conversion reached 83% with a syngas selectivity of 99%, at a temperature of 573 K and atmospheric pressure [29].

In this study, we successfully constructed a series of xLa/NiAl-LDO catalysts by the coprecipitation–impregnation method for CO2 hydrogenation. The influence of the mole ratio of Ni to Al La content on the catalyst structure, morphology, surface properties, and CO2 hydrogenation performances were discussed. Then a series of CO2 methanation activity tests were performed to establish the intrinsic kinetics of the catalysts by determining key parameters such as the reaction order, apparent activation energy, and pre-exponential factor. Finally, the methanation rate expression was established. These findings will provide data support for collecting CO2 and converting it into natural gas.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. XRD Analysis

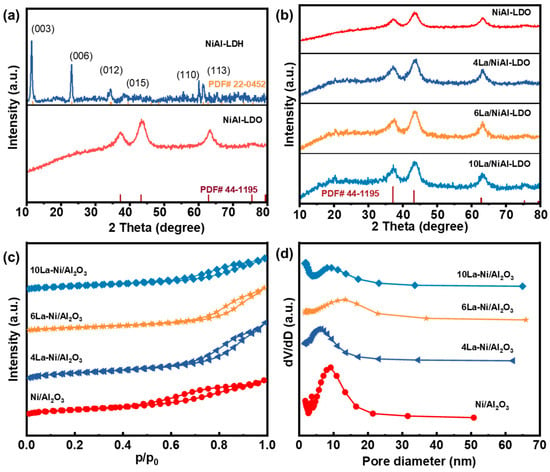

The XRD patterns of all catalyst materials are illustrated in Figure 1a,b. As depicted in Figure 1a, the 2θ angles at 11.7°, 23.6°, 34.3°, 35.16°, 39.6°, 60.3°, and 61.4° are attributed to the (003), (006), (012), (015), (110), and (113) planes of the hydrotalcite-like NiAl-LDH phase, respectively (PDF# 22-0450) [30]. After calcination, the diffraction peaks at 37.25°, 43.29°, 62.8°, and 75.4° correspond to the (101), (012), (104), and (113) crystal phase of NiO (PDF# 44-1159) [31]. In addition, the absence of any Al2O3 diffraction peak suggests Al2O3’s amorphous nature after calcination at 450 °C [32]. These findings indicate the successful preparation of NiAl-LDO. After impregnating with different concentrations of La (4 wt.%, 6 wt.%, and 10 wt.%), no diffraction peaks belonging to La were found for as-prepared 4La/NiAl-LDO, 6La/NiAl-LDO, or 10La/NiAl-LDO (Figure 1b). This is related to the high dispersion of La2O3 nanoparticles on the surface of NiAl-LDO.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns for (a) NiAl-LDA, NiAl-LDO and their PDF#, (b) samples, (c) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and (d) pore size distribution of NiAl-LDO, 4La/NiAl-LDO, 6La/NiAl-LDO, and 10La/NiAl-LDO.

2.2. N2 Adsorption

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of NiAl-LDO, 4La/NiAl-LDO, 6La/NiAl-LDO, and 10La/NiAl-LDO are shown in Figure 1c. As depicted in Figure 1c, all four catalytic materials exhibit Type IV isotherms with a H3 hysteresis loop in the high p/p0 region according to the IUPAQ classification, suggesting the presence of a typical mesoporous structure in the catalytic materials with an average aperture range less than 20 nm (Figure 1d). Moreover, Table 1 exhibits the specific surface area (SBET) and pore size distribution of all catalytic materials; with an increase in La loading amount, the specific surface area of the XLa/NiAl-LDO catalyst slightly decreases to 86.6 m2/g. This is mainly due to the fact that La2O3 is loaded on the surface of NiAl-LDO, blocking some of the pores. Meanwhile, total pore volume and average pore size also follow the same trend.

Table 1.

Specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size of catalysts.

2.3. SEM and TEM Analyses

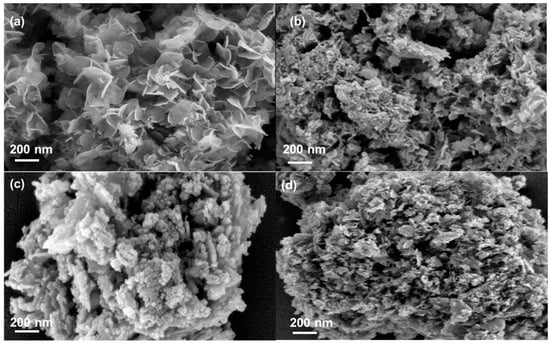

Figure 2 presents the SEM images of the catalyst samples. NiAl-LDH (Figure 2a) shows a sheet-like structure. After calcination, the sheet-like structure of NiAl-LDH collapses, and the metallic oxide structure of NiAl-LDO hardly shows a typical layered structure (Figure S1). As seen in Figure 2b–d, as the La loading increased, the surface of synthesized 4La/NiAl-LDO, 6La/NiAl-LDO, and 10La/NiAl-LDO catalysts exhibited considerable aggregation.

Figure 2.

SEM images of (a) NiAl-LDH, (b) 4La/NiAl-LDO, (c) 6La/NiAl-LDO, and (d) 10La/NiAl-LDO.

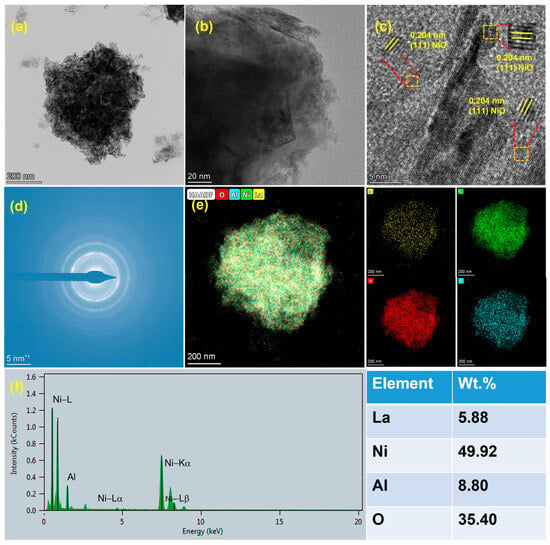

As depicted in Figure 3a,b, the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst precursor presents a layered structure. The HRTEM image of Figure 3c shows lattice fringes with a spacing of 0.240 nm, corresponding to the (111) plane of NiO, which is consistent with Figure 3d [33]. As seen in Figure 3e,f, the HAADF-STEM image and corresponding elemental mapping images of 6La/NiAl-LDO demonstrate the good distribution of Ni, O, Al, and La elements.

Figure 3.

(a,b) TEM, (c) HRTEM, (d) selected area electron diffraction pattern, (e) HAADF-STEM image and (f) corresponding elemental mapping images of the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst precursor.

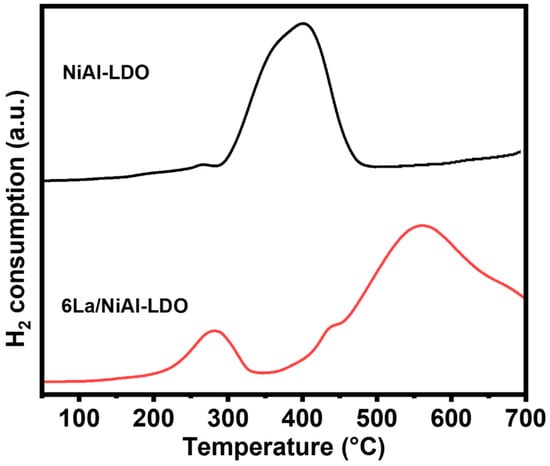

2.4. H2-TPR and XPS Analyses

Temperature-programmed reduction (TPR) was employed to further demonstrate the reducibility of catalysts and electronic interactions between the oxide and metal components; the results are shown in Figure 4. The calcined NiAl-LDO and 6La/NiAl-LDO samples show distinct reduction behaviors. The catalyst precursor 6La/NiAl-LDO shows two reduction peaks, a low-temperature peak centered around 280 °C, corresponding to the reduction in the surface NiO species, which is lower than that of NiAl-LDO (centered at 360 °C) [34], and a high-temperature peak located around 540 °C in 6La/NiAl-LDO, suggesting the presence of multiple nickel oxide species with strong interaction between La on the surface of NiAl-LDO [35].

Figure 4.

H2-TPR profiles of NiAl-LDO and 6La/NiAl-LDO.

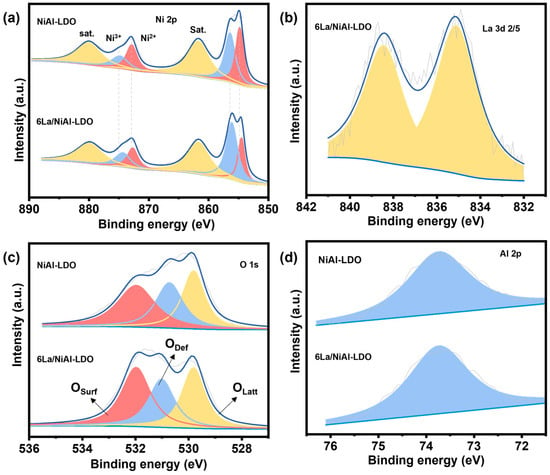

XPS analysis was performed to elucidate the chemical valence states and element composition of as-synthesized catalysts. Figure S2 exhibits the XPS survey spectra of NiAl-LDO and 6La/NiAl-LDO. These results suggest that NiAl-LDO consists of Ni, O, and Al, whereas 6La/NiAl-LDO comprises Ni, La, O, and Al. As presented in Figure 5a, the Ni 2p component of both Ni-based catalysts is fitted into six peaks; the peaks at 854.8 eV and 872.9 eV are attributed to Ni2+ [36], while the peaks at 856.4 eV and 879.2 eV are attributed to Ni3+, respectively [37]. The peaks at 861.7 eV and 880.1 eV are two satellite peaks. Additionally, the peak at about 856.4 eV is mainly caused by the presence of Ni-Al-layered oxides [38]. In the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst precursor, the Ni 2p peaks shift to lower binding energies compared to the pristine NiAl-LDO, suggesting the existence of an interaction force between La and Ni. Figure 5b illustrates the La 3D spectra of the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst precursor. As depicted in Figure 5b, the La 3D spectra located at 835.1 eV and 838.4 eV belong to La 3 d5/2. The O 1s spectrum of NiAl-LDO (Figure 5c) is fitted into three peaks at 529.8 eV, 530.7 eV, and 531.98 eV, corresponding to the lattice oxygen of metal oxides (OLatt), defected O2 (ODef), and surface-adsorbed oxygen species (OSurf). Among them, ODef plays a crucial role in activating adsorbed CO2, thereby promoting its conversion to CH4. Here, the percentage of ODef in NiAl-LDO is 27.9%, whereas the percentage of ODef in 0.6La/NiAl-LDO is 30.2%.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra of (a) Ni 2p, (b) La 3d, (c) O 1s, and (d) Al 2p of the NiAl-LDO and 6La/NiAl-LDO as-synthesized catalysts.

2.5. Catalytic Hydrogenation of CO2

Various catalysts such as NiAl-LDO, 4La/NiAl-LDO, 6La/NiAl-LDO, and 10La/NiAl-LDO were reduced by H2 at 450 °C for 3 h. The catalytic activity in terms of CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity for all the investigated catalysts is reported.

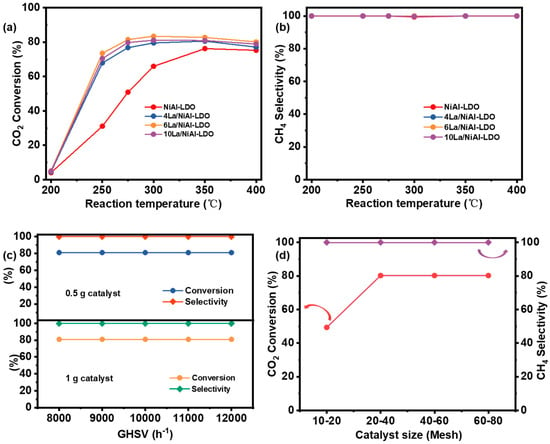

The effect of Ni content in NiAl-LDO catalysts on CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity was first evaluated under the conditions of 300 °C, 2 MPa, a weight hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 10,000 h−1, and a H2/CO2 ratio of 4:1. According to Figure 6a,b, 40NiAl-LDO (NiAl-LDO) exhibited superior performance among all tested catalytical materials. Consequently, 40NiAl-LDO (NiAL-LDO) was selected as the optimal material for subsequent condition screening. Internal diffusion limitations of catalysts arise from the porous structure of the catalyst materials, where significant internal resistance can lower the transport efficiency of reactants into the particle interior, thereby reducing the reaction rate. External diffusion, in contrast, pertains to the mass transfer of reactants from the bulk fluid to the catalyst surface; high external resistance impedes effective reactant access to active sites, likewise diminishing the reaction rate. To assess the influence of external diffusion over NiAL-LDO, methanation tests were conducted under conditions such as 20–40 mesh, 350 °C, and 1 MPa by loading the reactor with two different catalyst masses (0.5 g and 1.0 g), thereby varying the weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) within 8000–12,000 h−1. As depicted in Figure 6c, the CO2 conversion remains nearly identical for both catalyst loadings at WHSV values exceeding 8000 h−1. This consistency indicates that external diffusion limitations are negligible within this range. Similarly, the influence of the NiAL-LDO catalyst’s particle size (internal diffusion) was evaluated under the following conditions: 350 °C, 1 MPa, 8000 h−1, and a catalyst loading of 1 g. The CO2 methanation performance was tested using particle size fractions of 10–20, 20–40, 40–60, and 60–80 mesh. As presented in Figure 6d, reducing the particle size from the 20–40 to the 60–80 mesh range did not lead to a significant change in CO2 conversion. This observation indicates that internal diffusion limitations are negligible for catalyst particles sized 20–40 mesh. In addition, the reactor has a relatively small diameter (10 mm), and the catalyst bed is only 8 mm thick, with no temperature gradient. Therefore, heat transfer is not taken into account.

Figure 6.

(a,b) 1 CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity of various Ni contents in NiAl-LDO; CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity of (c) 2 GHSV; (d) 3 catalyst size. Note: Reaction Conditions: 1. 1 g catalyst, 20–40 mesh, 300 °C, 2 MPa, GHSV of 10,000 h−1, and a H2/CO2 mole ratio of 4:1; 2. 20–40 mesh, 300 °C, 2 MPa, H2/CO2 mole ratio of 4:1; 3. 350 °C, 1 MPa, 8000 h−1, 1 g NiAL-LDO catalyst.

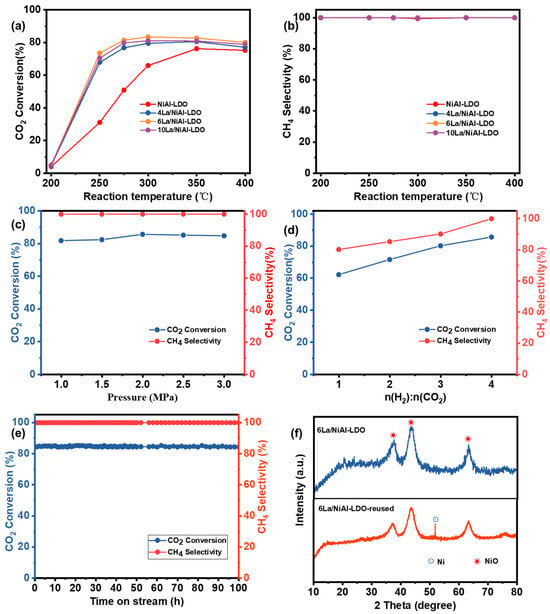

The effect of various catalysts such as NiAl-LDO, 4La/NiAl-LDO, 6La/NiAl-LDO, and 10La/NiAl-LDO on CO2 methanation were evaluated under conditions such as 1 g catalyst, 20–40 mesh, 2 MPa, GHSV of 10,000 h−1, and a H2/CO2 mole ratio of 4:1; the results are illustrated in Figure 7a,b. As depicted in Figure 7a,b, the conversion of CO2 increased significantly with the rise in reaction temperature, until it reached the thermodynamic equilibrium conversion rate over all four catalytic materials, and CH4 selectivity remained at 99.9%. Among them, 6La/NiAl-LDO exhibited the highest CO2 conversion compared to the other three catalysts with 85.6% CO2 conversion and 99.9% CH4 selectivity at 300 °C. The key of this issue lies in the synergistic effect between Ni and La in the catalyst. Nickel serves as the primary active center, and its concentration (Ni/Al ratio) directly determines the number of active sites. Lanthanum acts as a critical promoter, enhancing the surface basicity of the catalyst to facilitate CO2 adsorption and activation. The optimal ratio of 6La/NiAl-LDO achieves a balance among high active site density, excellent CO2 activation capability, and structural stability. All catalysts displayed poor CO2 conversion at 200 °C because of insufficient activation energy. With temperature elevation (≥240 °C), the CO2 conversion markedly increased for four catalytical materials until it reached around 85%. Interestingly, no other C-containing products were detected, suggesting no carbon deposition during the hydrogenation. Therefore, optimal 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst and reaction temperature of 300 °C were selected for the screening of other conditions. The effect of reaction pressure was evaluated under conditions such as 1 g 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst, 20–40 mesh, reaction temperature of 300 °C, H2/CO2 mole ratio of 4:1, and GHSV of 10,000 h−1; the results are shown in Figure 7c. As illustrated in Figure 7c, with an increase in the total pressure of the mixture gas (H2, N2, and CO2), CO2 conversion firstly increased and then reached 85.6% of the thermodynamic equilibrium at 2 Mpa, and CH4 selectivity remained constant at 99.9%. Therefore, the optimal reaction pressure is 2 Mpa. Then the effect of H2/CO2 mole ratio was evaluated under conditions such as 1 g 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst, reaction temperature of 300 °C, reaction pressure of 2 MPa, and GHSV of 10,000 h−1; the results are shown in Figure 7d. As depicted in Figure 7d, an increase in the H2/CO2 molar ratio led to a concurrent rise in both CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity. When H2/CO2 molar ratios were lower than 4, CO and carbon deposition emerged as the dominant by-products, with possible traces of methanol. Therefore, the selectivity is relatively low when H2/CO2 molar ratios are lower than 4. Figure 7e and Figure S3 show the durability test results of La/NiAl-LDO and NiAl-LDO under 300 °C, 2 MPa, and a H2/CO2 mole ratio of 4:1. The 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst showed stable performance throughout 100 h of CO2 methanation. CO2 conversion remained at 84.5% and 79.9%, respectively, with almost 99.0% CH4 selectivity. Moreover, as depicted in Figure 7f, after the 50 h durability test, an XRD diffraction peak of Ni0 was detected in 6La/NiAl-LDO-used. Compared to 6La/NiAl-LDO, the 6La/NiAl-LDO-used catalyst had undergone in situ partial reduction at 420 °C under 10% H2/N2 flow for 3 h, and there were Ni0 with active sites. Finally, the performance of the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst was compared with the previous literature, and the results are shown in Table S1. As depicted in Table S1, for single-metal catalysts, the NiAl-LDO catalyst shows higher CO2 conversion at 80.3% and higher STY (CH4) at 1692 mmol/(gcat·h). This CO2 conversion remains inadequate for industrial production. After incorporation of other metal additives, Ni–N3 catalysts reach 92.5% CO2 conversion, while STY (CH4) is at 1350 mmol/(gcat·h). Compared with Ni–N3 catalysts under a 350 °C hydrogenation temperature, 6La/NiAl-LDO shows 1804 of STY (CH4) in the lower reaction temperature (300 °C). These results demonstrate the superior efficiency and atomic economy of the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst.

Figure 7.

(a) CO2 conversion and (b) CH4 selectivity of reaction temperature over NiAl-LDO, 4La/NiAl-LDO, 6La/NiAl-LDO, and 10La/NiAl-LDO; CO2 conversion, and CH4 selectivity of (c) reaction pressure, (d) mole ratio of n (H2) to n (CO2) over 6La/NiAl-LDO, (e) long-term stability evaluation in the CO2 methanation over 6La/NiAl-LDO, and (f) XRD patterns of 6La/NiAl-LDO and 6La/NiAl-LDO-used.

3. Reaction Kinetics

A series of CO2 methanation activity tests were performed to establish the intrinsic kinetics of the catalyst by determining key parameters such as the reaction order, apparent activation energy, and pre-exponential factor. Prior to testing, the catalyst was ground, sieved to collect the 20–40 mesh fraction, and then uniformly mixed with an equal volume of SiO2 particles before being packed into the isothermal zone of the reactor. In situ reduction of the catalyst was conducted at 400 °C for 2 h under a H2 flow of 50 mL/min before the reaction.

Given that the CO2 methanation at low temperatures (<350 °C) exhibits high selectivity towards methane (99.9% for CH4 in this study) with minimal side reactions, the kinetic analysis was simplified by neglecting competing reaction pathways (Equation (1)).

3.1. Determination of Reaction Orders

The CO2 methanation over Ni-based catalysts is a heterogeneous catalytic reaction that proceeds through multiple steps, including external/internal diffusion, adsorption/desorption on the catalyst surface, and the surface chemical reaction. As shown in Figure 6c,d, external diffusion limitations are negligible at WHSV within 8000–12,000 h−1, and internal diffusion limitations are negligible for 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst particles sized 20–40 mesh.

Duyar et al. indicated that reaction orders with respect to CH4 and H2O were determined as −0.11 and −0.23, respectively. These values, obtained under relevant partial pressure ranges (CH4: 1–25 kPa; H2O: 3–20 kPa) and over a wide span of CO2 conversions (25–89%), showed a slight inhibitory effect of both products on the methanation rate, which was not expected to significantly limit the reaction even at high conversions [39]. Thus, the reaction rate of CO2 conversion can be expressed as given in Equation (2):

Here, r represents CO2 conversion, mol/(g·h);

k represents the rate constant of the reaction;

is the partial pressure of H2, kPa;

is the partial pressure of CO2, kPa.

Despite its simplicity, Equation (2) offers practical utility by providing a general estimate of the parameters necessary for reactor modeling. The power-law coefficients of the reactants also yield a rough indication of the potential rate-determining step.

The reaction orders were determined first under the following conditions: reaction temperature, 265 °C; gas hourly space velocity, 8000 mL/(g·h); total gas flow rate, 133 mL/min; and catalyst mass, 1 g. The concentrations of H2 or CO2 were varied by adjusting the flow rates of CO2, H2, and N2. The H2 content was varied between 60% and 80% for determining the H2 reaction order, while the CO2 content was varied from 10% to 20% for the CO2 reaction order.

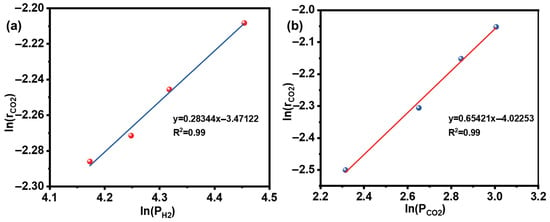

The CO2 conversion was measured at different concentrations of H2 or CO2, and the corresponding reaction rates were calculated using Equation (2). The relationship between the logarithm of the reaction rate and the logarithm of the partial pressure of CO2 or H2 is shown in Figure 8. When the partial pressure is fixed and the partial pressure is changed, the slope in Figure 8a is reaction order x of H2. Similarly, when the partial pressure is fixed and the partial pressure is changed, the slope in Figure 8b is reaction order y of CO2. The sum of the positive reaction orders for H2 and CO2 is (x + y). The slopes of the linear fits to the data points give the reaction orders with respect to each reactant. The sum of the positive reaction orders for H2 and CO2 (x + y) was found to be 0.93, approximately equal to 1, indicating that the positive reaction follows first-order kinetics.

Figure 8.

CO2 reaction rate as a function of partial pressure: (a) H2; (b) CO2.

Here, rCO2 represents the CO2 conversion rate;

FCO2,in is the inlet flow rate of CO2, mol/h;

mcat is the mass of the catalyst, g.

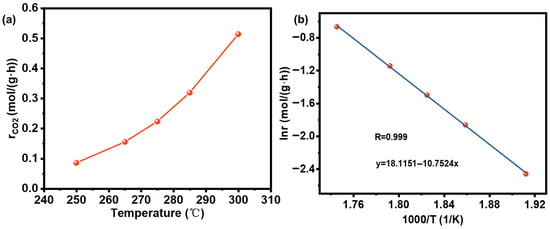

3.2. Apparent Activation Energy

Under atmospheric pressure and at temperatures ranging from 250 to 300 °C, with a feed gas composition of H2:CO2 = 4:1, a space velocity of 8000 mL/(g·h), and a total gas flow rate of 133 mL/min, CO2 conversion rates were measured by varying m/F, and the results are shown in Table S2.

The relationship between the rate constant and temperature is quantitatively described by the Arrhenius equation. Its indefinite integral form is given by Equation (4):

where:

k is the reaction rate constant, in concentration units;

is the pre-exponential factor, in the same units as k;

Ea is the apparent activation energy, kJ/mol;

R is the universal gas constant, J/(mol·K);

T is the absolute temperature, K.

After substituting Equation (4) into Equation (2), plotting lnr against 1/T yields a linear relationship, from which the apparent activation energy Ea can be derived.

To determine the relationship between CO2 reaction rate and temperature, catalytic activity tests were conducted under the following conditions: atmospheric pressure, a temperature range of 250–300 °C, H2:CO2 = 4:1, a space velocity of 8000 mL/(g·h), a total flow rate of 133 mL/min, and a catalyst mass of 1 g. By adjusting the CO2 reaction temperature, the results are shown in Table S2 and Figure 9. The resulting data were fitted linearly, and the slope of the fitted line corresponds to activation energy −Ea/R; the activation energy for CO2 hydrogenation over 6La/NiAl-LDO is calculated by equals 89.4 kJ/(g·mol), and k is 7.3 × 105 L·h/mol. Therefore, the reaction kinetics equation is as follows:

Figure 9.

(a) Reaction rates at different temperatures. (b) Arrhenius plot for CO2 hydrogenation. T = 250–300 °C.

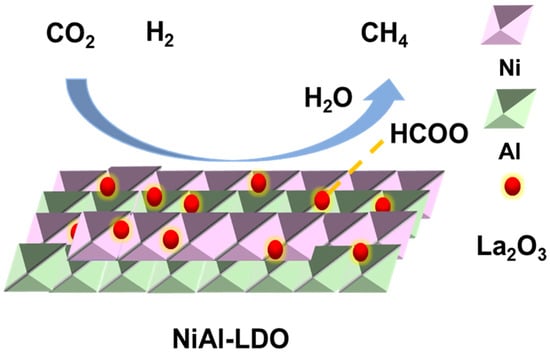

3.3. Proposed Mechanism for CO2 Methanation

Given that the CO2 methanation at low temperatures (<350 °C) exhibits high selectivity towards methane (99.9% for CH4 in this study) with minimal side reactions, a possible reaction mechanism for the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst was proposed, and the results are illustrated in Figure 10. Firstly, CO2 adsorbs on the NiAl-LDO carrier to form carbonate, and the addition of basic La2O3 promotes the adsorption of CO2. Ni0 serves as an active site; H2 adsorbs on the Ni0 site and dissociates H2 to an active hydrogen atom. Then, the active hydrogen atom overflows to the carrier and reacts with carbonate or bicarbonate to produce formate, which is further hydrogenated to ultimately produce methane.

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism for CO2 methanation over 6La/NiAl-LDO.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, >99.0 wt.%), lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O, >99.0 wt.%), and aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3·9H2O, >99.5 wt.%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, >99.8 wt.%), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, >99.5 wt.%), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, >96 wt.%) were obtained from Nanjing Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). N2 (99.999%) and H2 (99.999%) came from Nanjing Chuangda Special Gases (Nanjing, China). Deionized water without carbon dioxide was used in all the experimental processes. All the chemicals were used directly in this work.

4.2. Preparation of NiAl-LDH

The co-precipitation synthesis of NiAl-LDH involved the separate preparation of two solutions. Typically, 2.908 g (0.01 mol) Ni(NO3)2·6H2O and 3.7513 g Al(NO3)3·9H2O (0.01 mol) were dissolved in 50 mL deionized water to form solution A, and 2.56 g NaOH was dissolved in 50 mL deionized water to form solution B. Then, the two solutions were simultaneously dropped into a four-necked flask by peristaltic pumps, maintaining a pH of 10–11 at 60 °C. Following aging at 25 °C for 24 h, the resulting precipitation was collected by centrifugation and washed with deionized water and alcohol. Finally, the powder was dried to obtain 50NiAl-LDH (50 refers to the mole percentage of Ni in Ni + Al). The NiAl-LDH was subsequently calcined in a muffle furnace at 450 °C for 4 h with a heating rate of 10 °C/min to prepared 50NiAl-LDO. Similarly, 40NiAl-LDO, 30NiAl-LDO, and 20NiAl-LDO were prepared by altering the mole ratio of Ni to Al.

4.3. Preparation of xLa/40NiAl-LDO

The xLa/40NiAl-LDO catalysts (where x represents the mass loading capacity of La) were prepared by the impregnation method. In a typical procedure for preparing 4La/40NiAl-LDO (4La/NiAl-LDO), 2 g of the pre-synthesized 40NiAl-LDH was impregnated with an aqueous solution containing 0.25 g of La(NO3)3·6H2O in 50 mL deionized water. The mixture was magnetically stirred at 60 °C for 24 h, followed by drying at 100 °C for 24 h. The resulting solid was subsequently calcined in a muffle furnace at 450 °C for 4 h with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Similarly, 6La/NiAl-LDO, and 10La/NiAl-LDO were prepared through the adjustment of the mass ratio between La and 40NiAl-LDH.

4.4. Catalyst Characterization

The X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker D8, Ettlingen, Germany) was used to analyze the crystal structure of the samples with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at 40 kV and 40 mA. The surface area and pore size were assessed by N2 adsorption–desorption on an analyzer (Quantachrome, NOVA 3200e, Beijing, China), and the specific surface area was calculated according to the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, whereas the pore size and pore volume were derived from the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model. The sample morphology was acquired using a Gemini SEM 360 field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Gemini SEM 360, Aubergen, Germany). Surface composition and chemical states were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) on a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with an Al Kα source (1486.6 eV), using the C 1s peak of adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV for binding energy calibration.

4.5. Catalyst Evaluation

The catalytic performance was evaluated in a stainless tube fixed-bed reactor equipped with a 10 mm inner diameter and 50 cm length. Four thermocouples were inserted into the furnace chamber for precise temperature control (in the center, as well as at the top, middle, and bottom of the reactor’s outer wall). The temperature difference between the top and the bottom of the catalytic bed was 20 °C in order to keep a constant temperature in the catalyst bed (Figure S4). In a typical test, 1.0 g of the catalyst (20–40 mesh) was loaded, forming a bed with a height of approximately 8 mm. The catalyst bed was sandwiched between two layers of SiO2, each 24 cm in height. Prior to the reaction, the catalyst was firstly reduced in situ at 420 °C under 10% H2/N2 flow at a total flow rate of 133 mL/min for 3 h. Following cooling to room temperature, a gas mixture comprising CO2, H2, and N2 in a molar ratio of 18:72:10 (N2 as internal standard) was fed into the fixed-bed reactor and operated at a WHSV of 15,000 mL/(g·h) and 2 MPa. These carefully selected reaction conditions were confirmed to effectively eliminate the limitations of both internal and external mass diffusion. The reaction was allowed to stabilize for 1 h, after which the effluent gas was analyzed by an online Micro GC8670M (Dongchen, Nanjing, China) equipped with a TCD of TDX-01 chromatographic columns (Figure S5). The CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity were calculated according to Equations (5) and (6), respectively.

where and represent the mole flow rate of CO2 at the inlet and outlet of the reactor at standard temperature and pressure (STP), mL/min.

5. Conclusions

In this work, a NiAl layered double oxide (NiAl-LDO) series with varying Ni contents were prepared by co-precipitation. Rare-earth metal La was subsequently loaded onto the NiAl-LDO support via impregnation to obtain various La/NiAl-LDO catalyst precursors. H2-TPR results revealed a strong interaction between La and NiAl-LDO. CO2 methanation performance tests showed that the 6La/NiAl-LDO catalyst exhibited optimal catalytic performance, achieving 85.6% CO2 conversion with 99.9% CH4 selectivity at 300 °C and 2 MPa. The catalyst also demonstrated remarkable stability during a 100 h continuous test. Kinetic analysis revealed that the positive methanation reaction followed approximately first-order kinetics, with an apparent activation energy of 89.4 kJ/mol. The rate equation was established as:

These findings highlight the effectiveness of La doping in enhancing the activity and stability of NiAl-LDO catalysts, providing a feasible route for the design of high-performance CO2 methanation catalysts toward practical carbon utilization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal16010028/s1, Figure S1: SEM images of the NiAl-LDO; Figure S2: XPS survey spectra of NiAl-LDO, 6La/ NiAl-LDO; Figure S3: long-term stability evaluation in the CO2 methanation over NiAl-LDO; Figure S4: Diagram of catalyst performance evaluation device; Figure S5: Product analysis chromatogram; Table S1: Comparison of catalysts performance of CO2 methanation over different catalysts; Table S2: Conversion and reaction rate r over various reaction temperature and m/F. References [40,41,42,43] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.R., J.L., Y.C. and F.C.; methodology, W.L. and B.W.; validation, X.R.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, X.R. and W.L.; resources and funding acquisition, J.L.; data curation, W.L. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z. and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; supervision, X.R.; project administration, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jiangsu Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number (BK20231259). The APC was funded by Jinhua Liang.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Shi yan jia Lab (www.shiyanjia.com) for the XPS, SEM, and TEM analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

Shenghua Zhu and Fuchang Cheng are employed at CIMC Enric Holdings Limited; the remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Inoue, M.; Noda, R.; Shiga, R.; Fujiki, J.; Nakagawa, N. Derivation of a Kinetic Rate Expression and Parameters for CO2 Methanation over Ni/Na/γ-Al2O3 in a Dual Functional Material System. Fuel 2026, 406, 137026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cui, G. Influence of Spectral Characteristics of the Earth’s Surface Radiation on the Greenhouse Effect: Principles and Mechanisms. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 244, 117908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, H.; Li, S.; Yang, E.; Ding, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Y. Accurate Gas extraction (AGE) under the Dual-Carbon Background: Green Low-Carbon Development Pathway and Prospect. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budinis, S.; Krevor, S.; Dowell, N.M.; Brandon, N.; Hawkes, A. An Assessment of CCS Costs, Barriers and Potential. Energy Strategy Rev. 2018, 22, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, P.; Jin, S.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H. Ca-Ni-Based Dual-Function Materials for Integrated CO2 Capture and in-Situ Methanation with CO and HC Synergistic Purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 135151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, A.; Renda, S.; Di Stasi, C.; Truda, L.; Palma, V. Effective H2 Conversion to Substitute Natural Gas on Ni-Based Catalysts: Role of Promoters and Synthesis Method. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, G.A.; Bakare, A.I.; Sanhoob, M.A.; Kopyscinski, J. CO2 Methanation over BEA Zeolite Catalysts: Effect of MgO and in-Situ Ni Incorporation. Catal. Today 2026, 462, 115572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Technological and Economic Prospects for CO2 Utilization and Removal. Nature 2019, 575, 87–97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gac, W.; Zawadzki, W.; Słowik, G.; Kuśmierz, M.; Dzwigaj, S. The State of BEA Zeolite Supported Nickel Catalysts in CO2 Methanation Reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 564, 150421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, L.; Tong, Y.; Fang, X.; Xu, J.; Jiang, D.; Wang, X. Facile Cr3+-Doping Strategy Dramatically Promoting Ru/CeO2 for Low-Temperature CO2 Methanation: Unraveling the Roles of Surface Oxygen Vacancies and Hydroxyl Groups. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 5762–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Jiang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, G. In-Situ Encapsulation Synthesis of Ni-Ce/SBA-15 by EISA for Promoting CO2 Methanation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynkowski, J.M.; Paryjczak, T.; Lewicki, A.; Szynkowska, M.I.; Maniecki, T.P.; Jóźwiak, W.K. Characterization of Ru/CeO2-Al2O3 Catalysts and Their Performance in CO2 Methanation. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2000, 71, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Kuwahara, Y.; Kusu, K.; Bian, Z.; Yamashita, H. Ru/HxMoO3-y with Plasmonic Effect for Boosting Photothermal Catalytic CO2 Methanation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 317, 121734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, N.L.; Turner, S.J.; Stewart, J.A.; Vandegehuchte, B.D.; van der Hoeven, J.E.S.; de Jongh, P.E. Direct Observation of Ni Nanoparticle Growth in Carbon-Supported Nickel under Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation Atmosphere. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 14963–14973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, S.; Shimizu, T.; Otsuka, K. Complete Removal of Carbon Monoxide in Hydrogen-Rich Gas Stream through Methanation over Supported Metal Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2004, 29, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-López, A.; Pereda-Ayo, B.; Onrubia-Calvo, J.A.; González-Marcos, J.A.; González-Velasco, J.R. Boosting Dual Function Material Ni-Na/Al2O3 in the CO2 Adsorption and Hydrogenation to CH4: Joint Presence of Na/Ca and Ru Incorporation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, A.; Matarrese, R.; Visconti, C.G.; Castoldi, L.; Lietti, L. Storage Material Effects on the Performance of Ru-Based CO2 Capture and Methanation Dual Functioning Materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 6706–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promotion of Ru or Ni on Alumina Catalysts with a Basic Metal for CO2 Hydrogenation: Effect of the Type of Metal (Na, K, Ba). Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1052. [CrossRef]

- Highly Active Ce- and Mg-Promoted Ni Catalysts Supported on Cellulose-Derived Carbon for Low-Temperature CO2 Methanation. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 17212–17224. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsumichi, T.; Okuno, R.; Hashimoto, H.; Namiki, N.; Maeno, Z. Direct Capture of Low-Concentration CO2 and Selective Hydrogenation to CH4 over Al2O3-Supported Ni–La Dual Functional Materials. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 10842–10850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Ullah, N.; Hui, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Z. Enhanced CO2 Methanation Activity over Ni/CeO2 Catalyst by One-Pot Method. Mol. Catal. 2021, 508, 111602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onrubia-Calvo, J.A.; Pereda-Ayo, B.; González-Marcos, J.A.; González-Velasco, J.R. Lanthanum Partial Substitution by Basic Cations in LaNiO3/CeO2 Precursors to Raise DFM Performance for Integrated CO2 Capture and Methanation. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 81, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Urakawa, A. Continuous CO2 Capture and Reduction in One Process: CO2 Methanation over Unpromoted and Promoted Ni/ZrO2. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 25, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Song, C. A Short Review of Recent Advances in CO2 Hydrogenation to Hydrocarbons over Heterogeneous Catalysts. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 7651–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.Z.; Alias, H.; Shamjuddin, A.; Yusof, M.S.M.; Fan, W.K. Fundamentals and Advances in Photothermal CO2 Hydrogenation to Renewable Fuels over MOF-Hybrid Catalysts: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Kosari, M.; Jiang, Z.; Xi, S.; Xia, L.; Shao, Y.; He, C.; Zeng, H.C. Boosting CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol via Enriching the Cu-ZnO Interface on Layered Double Oxides. Small 2025, 21, 2412786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, W.; Yang, T.; Peng, C.; Liu, B.; Chen, K.; Sun, Q.; Wang, B.; Fang, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. In-Situ Constructing AlTiZn/CN Heterojunction via Memory Effect for Effective Degradation of Naphthalene under UV Irradiation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 193, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, M.; Poupin, C.; Labaki, M.; Aouad, S.; Delattre, F.; Gupta, S.; Lucette Tidahy, H.; Younis, A.; Ben Romdhane, F.; Gaigneaux, E.M.; et al. CO2 Methanation over LDH Derived NiMgAl and NiMgAlFe Oxides: Improving Activity at Lower Temperatures via an Ultrasound-Assisted Preparation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Quang, M.; Azzolina-Jury, F.; Samojeden, B.; Motak, M.; Da Costa, P. On the Influence of the Preparation Routes of NiMgAl-Mixed Oxides Derived from Hydrotalcite on Their CO2 Methanation Catalytic Activities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 37783–37791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fan, G.; Wang, H.; Li, F. Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Performance of Highly Dispersed Supported Nickel Catalysts from Ni–Al Layered Double Hydroxides. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 13717–13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yuan, H.; Li, J.; Bing, W.; Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wei, C.; Zhou, L.; Fang, S. Effects of Preparation Parameters of NiAl Oxide-Supported Au Catalysts on Nitro Compounds Chemoselective Hydrogenation. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 7011–7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yu, F.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Shi, Y.; Dai, B.; Guo, X. Two-Dimensional NiAl Layered Double Oxides as Non-Noble Metal Catalysts for Enhanced CO Methanation Performance at Low Temperature. Fuel 2019, 255, 115770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, C.; Ye, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Lim, K.H.; Wang, Y.; Arandiyan, H.; Xue, Q.; Chirawatkul, P.; et al. Tri-Synergistic Catalytic Mechanism of La-Doped Ternary Hydrotalcite for Low-Temperature CO2 Hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. B 2026, 382, 125909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quindimil, A.; De-La-Torre, U.; Pereda-Ayo, B.; González-Marcos, J.A.; González-Velasco, J.R. Ni Catalysts with La as Promoter Supported over Y- and BETA- Zeolites for CO2 Methanation. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 238, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Liu, D.; Fu, J.; Yao, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, J.; Yan, P.; Xiao, Z.; An, Q.; Huang, J. La2O2CO3-Supported Ni Nanoparticles with Enhanced Metal–Support Interactions for Selective Hydrogenation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, A.; Selvakumar, K.; Kang, M. Hydrogen Production via Water Splitting and Photocatalytic Cr(VI) Reduction Using Cadmium Sulfide-Integrated Ni–Co–Mn Layered Double Hydroxide. Fuel 2026, 406, 136949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Ma, Q.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Fan, S.; Zhao, T. Promotion of Al2O3 to Ni/In2O3 in the Low-Temperature CO2 + H2 Reaction to Methanol. Fuel 2026, 405, 136814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Xia, Y.; He, J.; Cai, D.; Bian, J.; Zhan, G. Design of Intermetallic PdZn Catalysts Supported on ZnAl Layered Double Oxides for Enhanced CO2 Thermal Hydrogenation to Methanol. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyar, M.S.; Ramachandran, A.; Wang, C.; Farrauto, R.J. Kinetics of CO2 Methanation over Ru/γ-Al2O3 and Implications for Renewable Energy Storage Applications. J. CO2 Util. 2015, 12, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam Abir, M.; Phillips, R.E.; Klug, J.; Monte, G.; Harrah, J.; Schreiber, K.; Ball, M.R. Gadolinium-Modified Nickel Catalysts for Enhanced CO2 Methanation. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 20472–20484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrola, M.; Miró, R.; Vicente, I.; Gual, A. Ni-Based Catalysts Coupled with SERP for Efficient Power-to-X Conversion. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, Z.; Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Ahmed, S.M.; Ullah, I.; Lou, H.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z. Engineering a Pyridinic N–Ni Single-Atom Catalyst for Efficient Low-Temperature CO2 Methanation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 20837–20845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, F.; Huang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Xing, W. Insights on the effect of Si-Al interaction on Ni/Al2O3/SiC monolithic catalysts for CO2 methanation. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 87, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.