Abstract

Anion exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFCs) are the most feasible choice of catalyst due to their high efficiency and scale of commercialization. However, the challenge posed by the sluggish kinetics of AEMFCs can only be countered by an effective electrocatalyst that enhances the reaction kinetics and, thereby, the fuel cell performance. The Pd-Co/C cathode catalyst is a promising choice of electrocatalyst, with the phenomenon of alloying playing a key role at appropriate temperatures and residence time distributions of annealing due to the influence of the lattice parameter, electrochemically active surface area (ECSA), and particle size. After completing the synthesis of 20 wt.% Pd-Co/C, the catalyst was treated under various annealing and loading conditions. This was subsequently followed by a series of physicochemical and electrochemical characterizations that verified the successful synthesis of the catalyst material, paving a path to optimizing the annealing temperature, annealing residence time, and catalyst loading. Further, proceeding with the fuel cell test runs with multiple profiles of the above parameters resulted in the optimization of the annealing temperature, residence time of annealing, and catalyst loading, and it was subsequently concluded that the best performance of the fuel cell was achieved when the Pd-Co/C catalyst was annealed at 500 °C for a duration of 1 h and loaded at 0.25 mg/cm2, which resulted in an impeccable power density of 724 mW/cm2.

1. Introduction

The demand for energy in the 21st century, an era where energy is globally at the forefront of development, is evident along with the threats of global warming and climatic change. The widespread environmental awareness among scientists and industrialists has pushed forward the requirement for green and sustainable energy sources with maximum thrust, especially in recent years [1,2]. Most of the world nations have emphasized their focus on green energy in order to reduce their dependence on non-renewable sources of energy, favoring a march towards a sustainable environment and carbon reduction [3,4]. However, this has not been simple, and tough challenges are posed by renewable and environment-friendly energy sources, the so-called green energy solutions, in terms of techno-economics and demand–supply imbalance [5,6]. The recent developments and promising progress in hydrogen fuel cells have made them frontrunners compared to other green energy sources. This is due to their higher efficiency over others and residual-free energy conversion [7]. Among the existing fuel cell technologies, proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) and anion exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFCs) have become prominent players in terms of their efficiency and commercialization [8,9]. They are not only potential sources of green energy but also could play a major role in the mission of net-zero carbon emission by 2050, which is a prospect for the majority of countries around the globe [10]. While PEMFCs face a backlash due to the use of precious metals like platinum for electrocatalyst synthesis, which are prone to corrosion in the acidic environment, AEMFCs prove to be advantageous, being flexible with the use of non-precious metals in an alkaline environment, ensuring higher stability and strong durability at a lower cost. This is due to the chemical nature of AEMFCs in facilitating oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), thus making it feasible not only to utilize nonprecious metal-based electrocatalysts but also to prevent potential threats of corrosion, cementing these fuel cells as a cost-effective technology [11,12]. The corresponding electrochemical reaction shown by an AEMFC using hydrogen as fuel and oxygen as oxidant is as follows [13]:

Anode reaction 2H2 + 4OH− → 4H2O + 4e−, E°298K = −0.83V

Cathode reaction O2 + 2H2O + 4e− → 4OH−, E°298K = 0.4V

Total reaction 2H2 + O2 → 2H2O, E°298K = 1.23V

Despite the several advantages, the slow kinetics of the hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR) still represent one of the most critical challenges, necessitating the use of a highly active electrocatalyst to enhance the fuel cell performance [13]. Slow kinetics leads to significant voltage loss and inferior anodic catalysis in AEMFCs compared to that of PEMFCs where the HOR kinetics is rapid [14,15]. Water is required for higher conductivity and greater ion mobility, but higher water content may increase the resistance and decrease the mechanical stability of the membrane, charge density, and ion flow [16]. A low hydrogen binding energy (HBE) at the surface of the catalyst is necessary for easier dissociation of hydrogen, which ensures improved fuel cell efficiency [17]. Previous studies reported that the exchange current density decreases by two times in the presence of the carbon-supported platinum electrode as the pH value increases from 0 to 13 for the HOR [18]. Palladium (Pd) has been the most preferred choice as an alternative to platinum due to its superior electrochemical activity towards ORR and HOR [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. However, in order to match the catalytic activity of platinum, there is a necessity to alloy palladium with other metals to alter its lattice constant and improve the electrochemical activity, which is lower than that of platinum despite its cheaper cost [28,29,30]. Nano palladium has proven to promote ORR efficiency due to multi-electron transfer pathways [31]. Palladium–cobalt alloys demonstrated enhanced ORR activity due to electronic stabilization of palladium [32]. Dekel and Gottesfeld studied the metal–metal interaction of Ni and Pd, which resulted in a favorable interaction leading to an improved HOR activity of AEMFC over monometallic Pd with the same loading [28]. The Pd-Co bimetallic catalysts showed excellent selectivity and activity, making them the best choice for improving the HOR and ethanol oxidation reaction (EOR) [33]. Alloying with Co also reduces the poisoning caused by the intermediates on the catalyst surface, which enhances electrocatalytic activity. The optimized composition and structure of Pd-Co/C alloy has shown better electrochemical performance and has the potential to replace the Pt/C alloy [34,35,36]. Therefore, Pd-Co/C was selected as the choice of catalyst for investigation to explore its catalytic behavior in the electrochemical reactions of the fuel cell.

The development of efficient cathode catalysts remains a critical factor in enhancing the overall performance of fuel cells, as the slow rate of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) often limits the cell efficiency. Pd-based alloys, particularly Pd-Co systems, have emerged as promising alternatives to Pt-based materials due to their high intrinsic ORR activity, improved durability in alkaline environments, and lower cost. The incorporation of cobalt into the Pd lattice induces significant electronic and geometric modifications that enhance the oxygen adsorption and facilitate the cleavage of the O-O bond. Carbon-supported Pd-Co alloy exhibited enhanced electrocatalytic activity for both reactions as compared to monometallic Pd and Co catalysts [37]. The strong interactions between the Pd-Co alloy and the nitrogen-doped carbon support significantly enhance the electrocatalytic performance, as compared to its monometallic Pd counterpart. This enhancement arises from the electronic modulation of Pd induced by Co alloying, which optimizes the adsorption–desorption behavior of reaction intermediates, coupled with the high surface area and excellent electrical conductivity provided by the nitrogen-doped carbon support [38]. Overall, these studies collectively demonstrate that Pd-Co based nanostructures exhibit superior ORR activity due to synergistic electronic effects, structural stability, and strong metal–support interactions. The combination of alloying strategies and carbon-based supports has thus been identified as a key design principle for next-generation Pd-based cathode catalysts in alkaline and low-temperature fuel cell applications. In this study, we report the successful synthesis of a Pd-Co/C electrocatalyst, followed by a series of structural and elemental analyses to confirm the uniform morphology and homogenous elemental distribution. The electrochemical characterizations were then carried to investigate the effects of thermal annealing temperatures and residual time distribution profiles on the catalyst performance. These parameters enable us to identify the appropriate working parameters for the optimal fuel cell performance.

2. Results

2.1. Physicochemical Characterizations

2.1.1. FTIR of the 20 wt.% Pd-Co/C Cathode Catalyst

The functional groups of carbon black (XC-72R) were analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy. FTIR spectrum showed the characteristic peaks with the wavenumbers of 1013, 1200, 1554, 1730, 2765, and 3600–3900 cm−1 corresponding to alkyl (C-H), ether (C=O), alkenyl (C=C), carbonyl (C=O), amine (NH), and phenol (OH) groups, onto the surface of carbon black before modification as shown in Figure S1. In contrast, the post surface modification showed two additional alkyl (C-H) groups at 856 cm−1 and 1362 cm−1, and several characteristic peaks in the range of 2000–2350 cm−1. The surface modification increases the polar functional groups, which increases the metal binding sites and promotes the catalytic activity of carbon black.

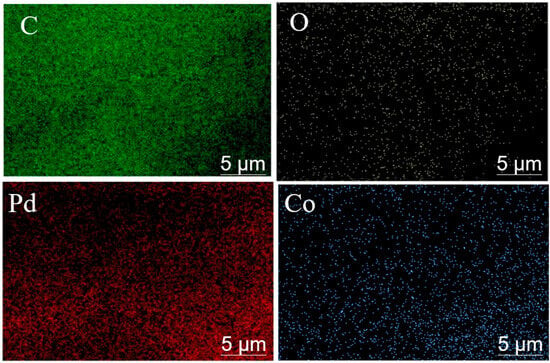

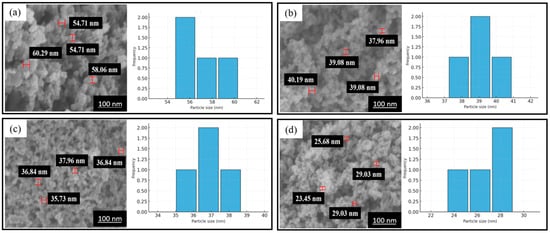

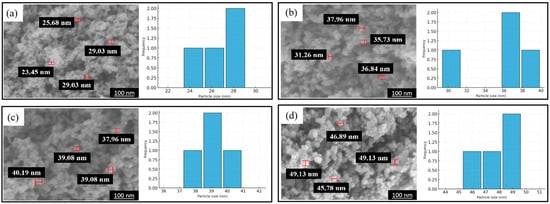

2.1.2. SEM and EDS Analysis

In Figure 1 and Table 1, SEM-EDS analysis was performed to verify the successful attachment and uniform elemental distribution of Pd and Co over the carbon black support. The elemental mappings confirm the uniform dispersion of Pd and Co at the surface of the carbon black support. EDS images showed the uniform distribution of Pd (red), Co (blue), O (white), and C (green) and successful synthesis of an efficient catalyst (Figure 1). Additionally, the weight percentage of carbon, palladium, cobalt, and oxygen are 72.97, 15.64, 4.01, and 7.38%, respectively (Table 1). SEM analysis helps in concluding and establishing a proportional relation between annealing temperature and residence time to the particle size. In Figure 2 and Table 2, the average particle size without annealing is 26.8 nm, while the average particle sizes with annealing at 400, 500, and 600 °C are 36.8, 39.1, and 56.9 nm, respectively. The average particles size gets bigger with the increase in annealing temperature. In Figure 3 and Table 3, the average particle size is 65.4, 39.1, 47.7, and 26.8 nm with the different annealing time of 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 h, respectively, at a temperature of 500 °C.

Figure 1.

Pd-Co/C elemental mapping diagram; carbon (as green dots), oxygen (as white dots), palladium (as red dots), and cobalt (as blue dots).

Table 1.

Elemental analysis of weight percentage and atomic percentage of Pd-Co/C.

Figure 2.

Pd-Co/C SEM images and particle size distribution at annealing temperatures of (a) 600 °C, (b) 500 °C, and (c) 400 °C and (d) without annealing.

Table 2.

Average particle size distributions at different annealing temperatures.

Figure 3.

Pd-Co/C SEM images and particle size distribution at residence time of annealing of (a) 600 °C, (b) 500 °C, and (c) 400 °C and (d) without annealing.

Table 3.

Average particle size distributions at different residence time of annealing.

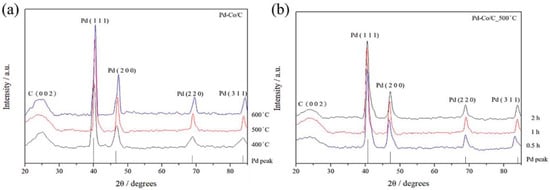

2.1.3. XRD Analysis of Pd-Co/C

The XRD analysis was performed to study the structure and phase purity of the Pd-Co/C cathode catalyst. The XRD planes and corresponding scattering angles 2θ are as shown in Figure 4. The XRD confirms face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice structural characteristics. The diffraction peak at the (002) plane confirms the hexagonal lattice structure of the XC-72R carbon black support. The incorporation of Co into the FCC structure of Pd induces a measurable lattice contraction. The (111) and (200) reflections of the Pd-Co/C samples showed the slight shifting of the diffraction peaks, which indicates that Co is incorporated into the Pd lattice. Using Vegard’s law, the estimated Co content in the Pd-Co alloy phase corresponds well with the approximate Pd2Co stoichiometry obtained from the SEM-EDS results. This structural and compositional consistency confirms that Co atoms are successfully incorporated into the Pd lattice and formation of the Pd-Co/C catalyst.

Figure 4.

XRD analysis of Pd-Co/C (a) at various annealing temperatures and (b) at different residence time distribution profiles for an annealing temperature of 500 °C.

Table 4 and Table 5 show the variation in lattice constant and particle size with annealing temperature and residence time for annealing, respectively. A lower lattice constant means that the atoms are more densely packed, making the bonding between atoms stronger, the lattice contraction stronger, and the alloying degree between Co and Pd is higher [39], which in turn influences the electronic structure and conductivity of the material, thereby improving the catalytic activity. Moreover, materials with low lattice constants usually have more grain boundaries and surface area, which can increase the surface activity of the material and facilitate surface adsorption. The lattice constant is found to be lowest at an annealing temperature of 500 °C and a residence time of 1 h. Temperature was found to have drastically influenced the particle size between the transition of 500 to 600 °C, compared to that of 400 to 500 °C, signifying the sensitivity of particle size towards higher operating temperatures, while it is steady with the increasing duration of residence time of annealing at a fixed annealing temperature.

Table 4.

Variation in lattice constant and particle size with annealing temperature.

Table 5.

Variation in lattice constant and particle size with residence time of annealing at 500 °C.

2.2. Electrochemical Characterization of Pd-Co/C Catalyst

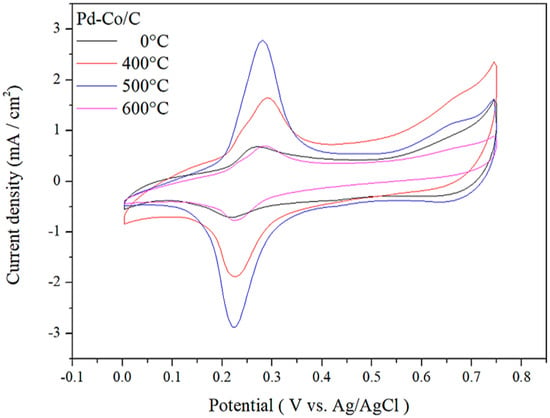

In Figure 5 and Figure 6, the cyclic voltammetry test was carried out to obtain electrochemical characterization of the catalyst with Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode. Using the 1 M KOH solution, the Pd-Co/C catalyst was coated on the working electrode. By scanning back and forth in the potential range of 0 to 0.75 V at a scanning rate of 50 mV/s, the electrochemical cyclic voltammogram was obtained.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammograms of Pd-Co/C catalyst at various annealing temperature profiles.

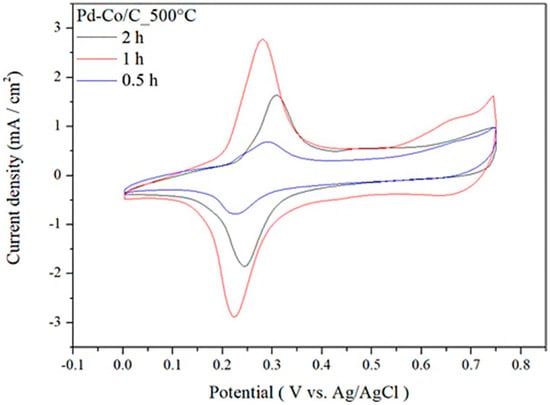

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of Pd-Co/C catalyst at annealing temperature of 500 °C under annealing residence time of 0.5, 1, and 2 h.

It can clearly be seen that during the scan from negative potential to positive potential, a distinct oxidation peak appeared at 0.28 V for the catalyst, when the annealing temperature was 500 °C, while in reverse scanning from positive potential to negative potential, an obvious reduction peak appeared at 0.22 V. The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) is a major factor that directly reflects the electrochemical activity of any material, and it is calculated by the following expression [40]:

QH is the charge measured during the hydrogen adsorption and desorption processes, QHref is the standard hydrogen adsorption charge per unit surface area, and m is the weight of the catalyst loaded on the glassy carbon electrode. The calculation results are shown in Table 6. The catalytic activity was found to increase significantly as the annealing temperature rose from 400 to 500 °C, which can be attributed to the enhanced degree of alloying and the resulting Co-Pd electronic interactions that optimize the electronic structure for ORR. This improvement is consistent with the observed increase in ECSA and lattice contraction at 500 °C, indicating a stronger metal–metal coupling effect. However, a further increase in temperature to 600 °C led to a decline in catalytic activity, likely due to particle growth and reduced active surface area, causing performance to be reduced to below that of the non-annealed catalyst.

Table 6.

ECSA for various annealing temperature profiles.

The ECSA calculation results indicate that the electrochemically active surface area is larger when the annealing temperature is 500 °C, thus favoring enhanced electrochemical activity. After the optimization of annealing temperature of the Pd-Co/C catalyst, the effect of annealing time was investigated and optimized, which showed a steady increase in ECSA upon increasing annealing residence time from 0.5 to 1 h, followed by a noticeable decrease when time further increases up to 2 h, indicating the maximum ECSA at annealing temperature of 500 °C and annealing residence time of 1 h, as shown in Figure 6 and Table 7.

Table 7.

ECSA for various annealing residence time profiles at annealing temperature of 500 °C.

2.3. AEMFC Single-Cell Test

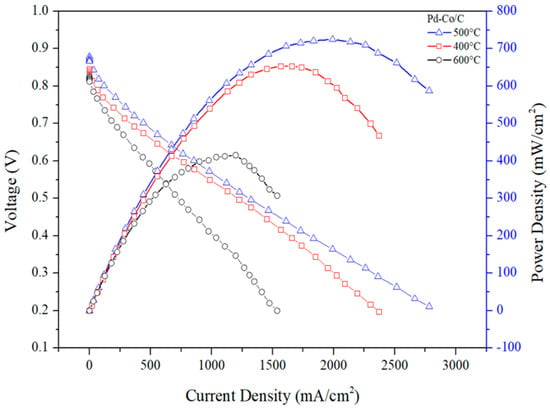

In Figure 7 and Table 8, the anode catalyst (Pt/C) loading was fixed to 0.8 mg/cm2 and that of the cathode was set to 0.25 mg/cm2 of Pd-Co/C annealed at different temperatures initially, and a fuel cell test was performed to investigate the effect of annealing temperature on fuel cell performance. The results demonstrate that the catalyst annealed at 500 °C showed up an impressive power density of 724 mW/cm2 and a corresponding cell voltage of 0.364 V. Proceeding further, to optimize the residual time for annealing, the fuel cell test was carried out under the same conditions with the Pd-Co/C catalyst being annealed at 500 °C at different residence time of annealing.

Figure 7.

Power density diagram at annealing temperatures of 400 °C, 500 °C, and 600 °C.

Table 8.

Power density performance at annealing temperatures of 400, 500, and 600 °C.

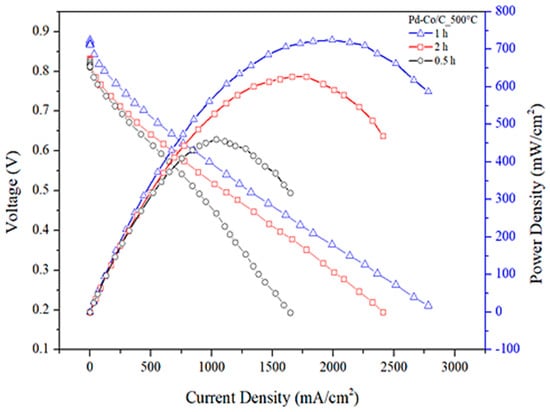

The AEMFC tests are shown in Figure 8 and Table 9. The Pd-Co/C cathode catalyst annealed at a temperature of 500 °C, for a duration of 1 h with a loading of 0.25 mg/cm2, yielded the optimal performance of the fuel cell with an impressive power density of 724 mW/cm2. This performance is significant and cost-effective in comparison with previous research works provided in the literature, as shown in Table 10.

Figure 8.

Power density diagram at annealing time of 0.5, 1, and 2 h.

Table 9.

Fuel cell output parameters at various annealing residence time distributions.

A comparison with commercial Pt/C catalysts has been conducted to benchmark the activity of the developed catalysts against the current state-of-the-art systems. As summarized in Table 10, Pt/C remains the most common reference catalyst in anion exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFCs), serving as both anode and cathode in various studies [42]. Li et al. reported that Pt and Pt-Ru catalysts exhibit comparable hydrogen oxidation activity in alkaline polymer electrolyte fuel cells operating at 80 °C, confirming the suitability of Pt-based materials as reliable standards for performance comparison [43]. Similarly, Su et al. demonstrated that Pt/C and Ag/C cathodes using commercial X37-50RT membranes achieved peak power densities in the range of 623 to 912 mW cm−2, which provides a practical benchmark for evaluating newly developed catalyst systems [42,44]. In addition, Yin et al. highlighted that alloying and heterostructure formation can further enhance oxygen reduction activity beyond conventional Pt/C, reinforcing the relevance of comparative studies against commercial benchmarks [45].

Table 10.

Anion exchange membrane fuel cell comparison.

Table 10.

Anion exchange membrane fuel cell comparison.

| Anode Catalyst | Cathode Catalyst | Anode Catalyst Loading (mg/cm2) | Cathode Catalyst Loading (mg/cm2) | Temperature (°C) | Membrane | Peak Power Density (mW cm−2) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt/C | Pt/C | 0.8 | 0.8 | 70 | X37-50RT | 703 | [42] |

| PtRu/C | Pt/C | 912 | |||||

| Pt/C | Ag/C | 0.8 | 1 | 70 | X37-50RT | 623 | [44] |

| Pt/C | Pt/C | 0.4 | 0.4 | 60 | QAPPT | 1070 | [43] |

| 80 | 1700 | ||||||

| Pt-Ru/C | Pd3Co | 0.4 | 0.04 | 80 | QAPPT | 1060 | [45] |

| Pt/C | Pd-Co/C | 0.8 | 0.25 | 80 | X37-50RT | 724 | This work |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

The gas diffusion layer (GDL 340) was purchased from CeTech, Taichung City, Taiwan. Carbon black (Vulcan XC-72R) was bought from Cabot Corporation, Boston, MA, USA. The 40 wt.% Pt/C was bought from Johnson Matthey, Taipei, Taiwan. Anion Exchange Membranes (Sustainion® X37-50RT) and ionomer (Sustainion® XB-7 Anion Exchange Dispersion 5% in ethanol) were purchased from Dioxide Materials, Bryan, TX, USA. Isopropyl alcohol (IPA) was purchased from Macron Fine Chemicals, Radnor, PA, USA. Chemicals, including potassium tetrachloropalladate, cobalt chloride hexahydrate, potassium hydroxide, sodium hydroxide, and ethylene glycol, were bought from Shen Chiu Enterprise Corporation, Tainan City, Taiwan. Argon (Ar) and hydrogen gases (H2) were bought from Air Products San Fu Co., Ltd., Taipei City, Taiwan.

3.2. Preparation of the Pd-Co/C Catalyst

The gas diffusion layer (GDL 340) of 3.65 × 3.65 cm2 in size was used for the fuel cell test. The Pd-Co/C catalyst, upon successful synthesis under various thermal annealing temperature profiles and residual time distribution, was tested with the appropriate optimal load test conditions.

3.2.1. Carbon Black Modification

Carbon black XC-72R plays a key role in the preparation of the catalyst slurry. Conductive carbon black’s microstructure is extremely porous, with a significant number of micropores and mesopores. The large surface area provided by this porous structure aids in the catalyst’s fixation and dispersion [46]. Higher electrical conductivity offered by carbon black highly favors the effective transfer of electrons, thus not only promoting the rate and kinetics of the redox reactions but also improving the performance of the fuel cell. Furthermore, its mechanical strength, chemical stability, and corrosion resistance making it an ideal choice of carrier material for the preparation of catalyst slurry. The modification of carbon black becomes essential to ensure appropriate surface morphology and the presence of desirable functional groups on its surface. The process begins with the addition of 20% Nitric acid to the XC-72R, followed by heat treatment at 110 °C for a duration of 12 h. Then, the modified carbon black particles are filtered using a vacuum filter and then washed with deionized water to neutralize the acidity. Finally, the collected carbon black particles are dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h, which provides us with the modified carbon black.

3.2.2. Preparation of the 40 wt.% Pt/C Anode Catalyst

The commercial 40 wt.% Pt/C (6.65 mg) was added to 300 mg of DI water and 300 mg of IPA subsequently to homogenize and ensure a uniform dispersion of catalyst particles. It is then added to 133.25 mg of 5% ionomer solution and ultrasonicated for 1 h leading to the successful synthesis of the Pt/C anode catalyst.

3.2.3. Preparation of the 20 wt.% Pd-Co/C Cathode Catalyst

In the preparation of 20 wt.% Pd-Co/C cathode catalyst, 102 mg of potassium tetrachloropalladate and 67.2 mg of cobalt chloride hexahydrate were added to 100 mL of ethylene glycol and mixed well for 30 min. After homogenization, 158 mg of the modified carbon black was added along with sodium hydroxide, pH between 11 and 12 was ensured, and it was heated at 100 °C, with constant stirring for 6 h. After the completion of the reaction, the slurry was filtered and washed with DI water for neutralization and then dried at 60 °C in the oven for 12 h. After drying, the product was annealed at the required temperature profiles and annealing residence time distributions. Finally, upon annealing the catalyst, it is cooled down in the Ar gas environment. The 8, 16.65, and 33.3 mg samples of the synthesized 20 wt.% Pd-Co/C were homogenized with 300 mg of DI water and subsequently with 300 mg of IPA, and finally, 40, 83.25, and 166.5 mg of the 5% ionomer solution was added and ultrasonicated for 1 h. The prepared slurries of cathode catalyst with the loadings of 0.12, 0.25, and 0.5 mg/cm2, were used for the fuel cell performance tests. The ionomer solution used was XB-7, which promotes the transfer of ions between the catalyst layer and the electrolyte membrane, to enhance the efficiency and performance of the fuel cell. DI water and IPA are used as dispersants to evenly disperse the catalyst powder.

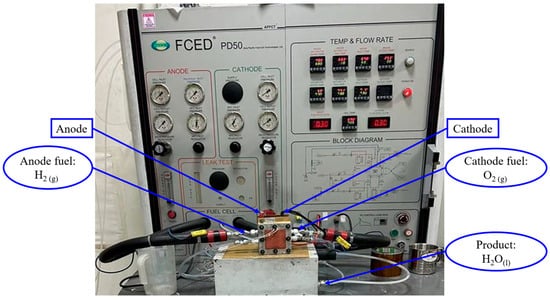

3.3. AEMFC Assembly and Optimal Loading Test

For the AEMFC test, anode catalyst loading was fixed at 0.8 mg/cm2, while the cathode catalyst was tested with three different profiles, using the 20 wt.% Pd-Co/C catalyst that was synthesized: 0.12, 0.25, and 0.5 mg/cm2. The 4 × 4 cm2 commercial AEM Sustainion® X37-50RT was pretreated by immersion in 1 M KOH for 8 h to separate the membrane from the transparent pad. Subsequently, the membrane was immersed in 1 M KOH for 48 h (with KOH solution being replaced every 24 h) to complete the OH− treatment. The microporous layer (MPL) is prepared using a mixture of a hydrophobic polymer (such as polytetrafluoroethylene, PTFE) and carbon black or carbon powder [46]. The microporous layer favors gas diffusion and improves the electrical conductivity, ensuring a uniform transfer of hydrogen and pure oxygen to the cathode and anode, respectively [47]. Moving further to the preparation of the gas diffusion electrode, the GDL 340 is first heated at 80 °C using a hot plate, upon which the homogenized anode and cathode catalyst slurries are coated, then immersed in 1 M KOH solution for 48 h (with the solution being replaced every 24 h), thus providing us with the gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs) to proceed with the fuel cell testing. The parameters for the fuel cell testing are shown in Figure 9 and Table 11.

Figure 9.

Schematic of AEMFC test.

Table 11.

Fuel cell test parameters.

4. Conclusions

This study was successful in establishing the significance and impact of the Pd-Co cathode electrocatalyst in catalyzing the redox reactions, thereby enhancing the performance of the fuel cells. Beginning with understanding the chemical nature of Pd and Co, and thus finding their alloy to be a feasible choice of electrocatalyst, the 20 wt.% Pd-Co/C was synthesized at appropriate reaction conditions and surface modification of the carbon black carrier. The thermal annealing temperature is a key player in this study as it influences the particle size and lattice parameter. Proceeding further with the necessity to optimize the catalyst loading, thermal annealing temperature, and annealing residence time for enhanced performance, a series of physicochemical and electrochemical characterizations were carried out. Beginning with the surface modification of carbon black, the Pd-Co/C cathode electrocatalysts were carefully synthesized with appropriate reaction and annealing conditions. The FTIR analysis ensured the successful surface modification of the carbon black. While the XRD analysis sorted the variation in lattice parameter and particle size with annealing temperature and residence time distributions of annealing. SEM-EDS verified the elemental composition and the uniformity of distribution over the catalyst surface through elemental mapping. The cyclic voltammetry provided some valuable insights on the electrochemical activity of the Pd-Co/C catalyst. This includes the ECSA study of Pd-Co/C, which suggested a better catalytic activity when annealed at 500 °C for 1 h. The fuel cell test was performed with the Pt/C anode catalyst fixed at a loading of 0.8 mg/cm2. The synthesized Pd-Co/C catalyst was treated at the required annealing temperature profiles at a loading of 0.25 mg/cm2, which provided that 500 °C is the favorable temperature of annealing for better fuel cell performance. Furthermore, the catalyst material was annealed at 500 °C at various residence time of annealing, which resulted in the better performance of the catalyst when annealed for 1 h. Then, the fuel cell test was conducted under the optimized conditions of annealing temperature, residence time with different cathode catalyst loadings, and constant operating conditions as earlier, resulting in a better performance when the loading was 0.25 mg/cm2, to achieve the maximum power density of 724 mW/cm2 and a current density of 1990 mA/cm2. This study highlights the importance of bimetallic catalyst supported on carbon black enhances the techno-economic feasibility and replaces platinum group metals. In future work, we will incorporate BET surface area analysis together with CO stripping experiments to more comprehensively establish the relationship between the physicochemical surface area and the electrochemical activity of the Pd-Co/C catalysts. Beyond these electrochemical validation methods, the future scope will also aim to address broader prospects, including enhancing environmentally sustainable alternatives to carbon black supports, and investigating catalyst materials beyond precious metals such as Pt and Pd. Additional efforts may involve simulation through COMSOL Multiphysics and subsequent validation using machine learning techniques, which could not only optimize the parametric conditions of emerging catalyst systems but also strengthen the reliability and predictive capability of future experimental studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121157/s1, Figure S1: FTIR spectra depicting the effect of surface modification of the carbon black carrier.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V. and P.-H.C.; methodology, P.V. and P.-H.C.; validation, H.Y.; formal analysis, P.-H.C.; investigation, P.V. and P.-H.C.; resources, H.Y. and P.P.; data curation, P.-H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.V.; writing—review and editing, P.V., F.-C.S., and M.J.I.; visualization, F.-C.S. and M.J.I.; supervision, H.Y. and P.P.; project administration, H.Y. and P.P.; funding acquisition, H.Y. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan, grant number “NTSC 113-2221-E-005-077-MY3” and “NSTC 113-2634-F-005-002”—project Smart Sustainable New Agriculture Research Center (SMARTer), and supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, under the Higher Education Sprout Project.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all the authors and the students participated in Taiwan Education Experience Program (TEEP), supported by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, who joined the research team and assisted in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martins, F.; Felgueiras, C.; Smitkova, M.; Caetano, N. Analysis of fossil fuel energy consumption and environmental impacts in European countries. Energies 2019, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, P.; Shabbir, M.S.; Siddiqi, A.F.; Wang, X. Current status and future prospects of renewable energy: A case study. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2020, 42, 2698–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascaris, A.S.; Schelly, C.; Burnham, L.; Pearce, J.M. Integrating solar energy with agriculture: Industry perspectives on the market, community, and socio-political dimensions of agrivoltaics. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, D. A review of multiphase energy conversion in wind power generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, C.; Bhowmik, S.; Ray, A.; Pandey, K.M. Optimal green energy planning for sustainable development: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 796–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.M. Green energies and the environment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 1789–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Shi, Z.; Glass, N.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Song, D.; Liu, Z.-S.; Wang, H.; Shen, J. A review of PEM hydrogen fuel cell contamination: Impacts, mechanisms, and mitigation. J. Power Sources 2007, 165, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Long, W.; Wang, L.; Yuan, R.; Ignaszak, A.; Fang, B.; Wilkinson, D.P. Unlocking the door to highly active ORR catalysts for PEMFC applications: Polyhedron-engineered Pt-based nanocrystals. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, G.; Wessling, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Anion exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 377, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.; Setzler, B.P.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, T.; Gottesfeld, S.; Yan, Y. Low-temperature direct ammonia fuel cells: Recent developments and remaining challenges. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2020, 21, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, D.; Du, C.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xia, B.; Yang, H.; Akins, D.L. Carbon-supported Pd-Co bimetallic nanoparticles as electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Power Sources 2007, 167, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Bao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, G.; Luo, W. Enhanced HOR catalytic activity of PGM-free catalysts in alkaline media: The electronic effect induced by different heteroatom doped carbon supports. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 10936–10941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustain, W.E. Understanding how high-performance anion exchange membrane fuel cells were achieved: Component, interfacial, and cell-level factors. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 12, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyerlin, K.; Gu, W.; Jorne, J.; Gasteiger, H.A. Study of the exchange current density for the hydrogen oxidation and evolution reactions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, B631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Gasteiger, H.A.; Shao-Horn, Y. Hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction kinetics on platinum: Acid vs alkaline electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, B1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yang, W. Measurements of water uptake and transport properties in anion-exchange membranes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 5656–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Sheng, W.; Zhuang, Z.; Xu, B.; Yan, Y. Universal dependence of hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction activity of platinum-group metals on pH and hydrogen binding energy. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, J.; Siebel, A.; Simon, C.; Hasché, F.; Herranz, J.; Gasteiger, H. New insights into the electrochemical hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction mechanism. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2255–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Qiao, S.; Vasileff, A. Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Solution: From Theory, Single Crystal Models, to Practical Electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. 2017, 130, 7690–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Shen, X.; Su, D.; Lu, G.; Zhu, X.; Yao, J.; Guo, J.; Huang, X. Surface engineering of hierarchical platinum-cobalt nanowires for efficient electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Chen, W. “Naked” Pd nanoparticles supported on carbon nanodots as efficient anode catalysts for methanol oxidation in alkaline fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2012, 204, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, Q.; Yang, W.; Han, K.; Wang, Z.M.; Zhu, H. Graphene–CeO2 hybrid support for Pt nanoparticles as potential electrocatalyst for direct methanol fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 94, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Roling, L.; Wang, X.; Vara, M.; Chi, M.; Liu, J.; Choi, S.-I.; Park, J.; Herron, J.; Xie, Z.; et al. NANOCATALYSTS. Platinum-based nanocages with subnanometer-thick walls and well-defined, controllable facets. Science 2015, 349, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Kang, X.; Xu, C.; Zhou, J.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, S. 2D PdAg Alloy Nanodendrites for Enhanced Ethanol Electroxidation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Yang, W.; Wu, E.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J. PdAg alloy nanotubes with porous walls for enhanced electrocatalytic activity towards ethanol electrooxidation in alkaline media. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 698, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xin, L.; Sun, K.; Li, W. Pd–Ni electrocatalysts for efficient ethanol oxidation reaction in alkaline electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 12686–12697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guo, H.; Fujita, T.; Hirata, A.; Zhang, W.; Inoue, A.; Chen, M. Nanoporous PdNi Bimetallic Catalyst with Enhanced Electrocatalytic Performances for Electro-oxidation and Oxygen Reduction Reactions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 4364–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, D.R. Review of cell performance in anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2018, 375, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M. Palladium-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Zhuang, Z.; Gao, M.; Zheng, J.; Chen, J.G.; Yan, Y. Correlating hydrogen oxidation and evolution activity on platinum at different pH with measured hydrogen binding energy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-Hernández, J.; Ezeta-Mejía, A.; Reza-San Germán, C.; Citalán-Cigarroa, S.; Arce-Estrada, E. Electrochemical activity towards ORR of mechanically alloyed PdCo supported on Vulcan carbon and carbon nanospheres. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2014, 44, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadogo, O.; Lee, K.; Oishi, K.; Mitsushima, S.; Kamiya, N.; Ota, K.-I. New palladium alloys catalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction in an acid medium. Electrochem. Commun. 2004, 6, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, S.; Anilkumar, G.M.; Tamaki, T.; Yamaguchi, T. Cobalt-modified palladium bimetallic catalyst: A multifunctional electrocatalyst with enhanced efficiency and stability toward the oxidation of ethanol and formate in alkaline medium. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 4140–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.L.; Walsh, D.A.; Bard, A.J. Thermodynamic guidelines for the design of bimetallic catalysts for oxygen electroreduction and rapid screening by scanning electrochemical microscopy. M−Co (M: Pd, Ag, Au). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, J.L.; Raghuveer, V.; Manthiram, A.; Bard, A.J. Pd− Ti and Pd− Co− Au electrocatalysts as a replacement for platinum for oxygen reduction in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13100–13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-López, V.F.; Mason, T.; Shearing, P.R.; Brett, D.J. Carbon monoxide poisoning and mitigation strategies for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells—A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 79, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modibedi, M.; Masombuka, T.; Mathe, M. Carbon supported Pd-Sn and Pd-Ru-Sn nanocatalysts for ethanol electro-oxidation in alkaline medium. Fuel Energy Abstr. 2011, 36, 4664–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Dong, S.; Ouyang, Y. Pd(3)Co(1) Alloy Nanocluster on the MWCNT Catalyst for Efficient Formic Acid Electro-Oxidation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Lee, K.; Zhang, J. Effect of synthetic reducing agents on morphology and ORR activity of carbon-supported nano-Pd–Co alloy electrocatalysts. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 7964–7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, S.; Sun, G. Enhanced activity and stability of a Au decorated Pt/PdCo/C electrocatalyst toward oxygen reduction reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 77, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Chandran, P.; Ramaprabhu, S. Palladium-nitrogen coordinated cobalt alloy towards hydrogen oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions with high catalytic activity in renewable energy generations of proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.-C.; Yu, H.-H.; Yang, H. Anion-Exchange Membranes’ Characteristics and Catalysts for Alkaline Anion-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Membranes 2024, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Peng, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Lu, J.; Zhuang, L. The Comparability of Pt to Pt-Ru in Catalyzing the Hydrogen Oxidation Reaction for Alkaline Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells Operated at 80 °C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1442–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, F.-C.; Yu Chu, G.; Yang, H. Silver nano-particles modification used as cathode catalysts to enhance anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 534, 146544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Ma, S.; Ying, J.; Lu, Z.; Niu, X.; Feng, J.; Xu, F.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, W.; Cao, X. MOF–Derived N–Doped C @ CoO/MoC Heterojunction Composite for Efficient Oxygen Reduction Reaction and Long-Life Zn–Air Battery. Batteries 2023, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, S.; Pastor, E.; Lázaro, M. Electrochemical behavior of the carbon black Vulcan XC-72R: Influence of the surface chemistry. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 7911–7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostick, J.T.; Fowler, M.W.; Ioannidis, M.A.; Pritzker, M.D.; Volfkovich, Y.M.; Sakars, A. Capillary pressure and hydrophilic porosity in gas diffusion layers for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2006, 156, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).