Abstract

Nowadays, due to strategic reasons such as the importance of energy and environmental protection, the demand for alternatives to fossil fuels has surged. Hydrogen is considered a suitable and potential alternative energy source, promoting the development of various production technologies. However, conventional technologies for hydrogen production generate a large amount of CO2 greenhouse gases, contributing to serious environmental issues. In recent decades, TiO2 nanotubes have emerged as effective photocatalysts for electrode reactions involving water splitting, resulting in hydrogen production. These photocatalysts utilize readily available resources: water as the raw material and sunlight as the energy source. Despite their potential, TiO2 nanotubes face substantial challenges, including a large energy gap resulting in very low electrical conductivity, along with the recombination of electrons and electron holes during the water splitting reaction. These issues present considerable obstacles to the integration of these materials into the industrial cycle of new energy production, particularly hydrogen generation. Currently, the challenges and potential solutions associated with TiO2 have made it one of the most extensively researched materials worldwide. In this review, the status of photocatalysts based on TiO2 nanotubes is examined, highlighting the main challenges in this field and the proposed solutions to address these obstacles.

1. Introduction

Today, one of the most pressing issues facing mankind draws the attention of scientists in the field of energy. The excessive growth of the population, global industrialization, increasing energy demand, and depleting fossil fuel resources—along with the challenges of climate change and global warming—have led to a rise in human-driven CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use and industrial processes, accelerating environmental degradation. To combat this issue, it is essential to reduce pollution caused by burning fossil fuels through carbon dioxide reduction reactions using catalytic and photocatalytic processes [1]. Additionally, transitioning to renewable energy sources is crucial for addressing energy concerns. The extensive reliance on non-renewable energy by major powers has intensified the energy crisis and resulted in severe environmental problems, making the transition to clean and renewable alternative fuels essential [2,3]. Hydrogen, known as the simplest, lightest, and most abundant element in the universe, has gained significant attention as a promising energy carrier. Its potential for facilitating the shift from limited non-renewable energy sources to unlimited renewable ones is significant. Currently, approximately 15% of hydrogen production comes from fossil fuels, which releases substantial amounts of greenhouse gases [4,5]. To achieve cleaner hydrogen production and reduce air pollution, hydrogen can be generated using renewable sources such as water and solar energy. Photocatalytic hydrogen production from water is one of the most effective and cost-efficient methods for several reasons. This technology utilizes photon energy, a clean energy source, while water, the feedstock for the process, is renewable. Furthermore, this approach is entirely environmentally friendly, producing no harmful or polluting by-products [6,7]. Hydrogen production from solar water-splitting processes can generally be classified into three categories: thermochemical splitting, photobiological splitting, and the photocatalytic splitting of water [8]. If solar energy can be directly harnessed for hydrogen production without consuming electrical energy, a higher energy conversion efficiency is expected. The semiconductors used for water-splitting photoelectrodes must align effectively in terms of their conduction and valence band positions to achieve the oxidation and reduction potentials of water [9]. Since pure water cannot absorb light radiation, the water-splitting reaction requires an optical semiconductor material capable of absorbing light to generate electrons and holes. These generated carriers can then be utilized to convert absorbed water molecules on photocatalysts into their reduced and oxidized forms [6,7].

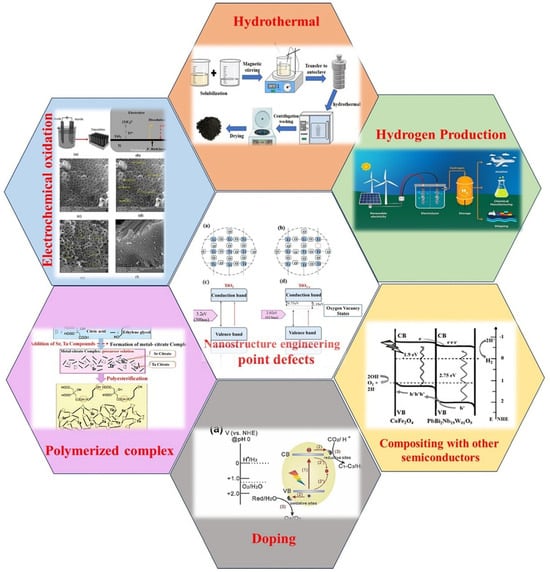

Due to its strong photocatalytic activity, high chemical stability, and the long lifespan of electron–hole pairs, titanium dioxide is one of the most widely used semiconductors for water-splitting photocatalysis. However, various characteristics of titania, including structural defects, crystal phases, particle size, rapid recombination of electron–hole pairs, low surface area, susceptibility to reverse reactions, and the production of water and band gaps, limit its suitability for visible light applications in the water-splitting process [10,11,12,13]. To address these challenges and enhance the efficiency of TiO2, several methods have been explored in recent years. These include loading noble metals such as gold [14], palladium [15], copper [16], and platinum [17], combining TiO2 with other semiconductors [18], modifying the surface of TiO2 particles with absorbers [19], adding colors and contaminating with non-metallic elements [20,21,22], and regenerating of nanotubes [23,24]. Despite these efforts, the challenge of hydrogen production using TiO2-based photoanodes, particularly through structural modification of this material, remains significant for researchers in this field. Recognizing this importance, the present review focuses on some of the most critical topics related to hydrogen production via the water-splitting method using the TiO2 photocatalyst. Figure 1 schematically shows all the topics discussed in this article.

Figure 1.

Overview of key topics in synthesis methods of TiO2 nanotubes used in the photocatalytic reaction of water splitting and hydrogen production.

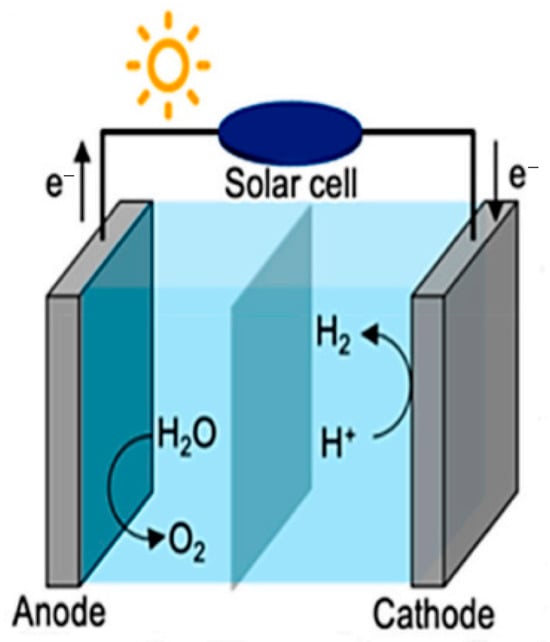

2. Photocatalysis

Photocatalysis refers to a light-driven reaction that uses a catalyst. It is recognized as a promising technology for various applications in environmental systems, including air and water purification, hazardous waste treatment, water disinfection, self-cleaning surfaces, and most importantly, energy production [25,26,27,28,29]. The primary goal of photocatalysis research is to foster a better understanding of the complex heterogeneous photochemical processes involving metal oxide systems in different environments [30,31,32]. A significant advancement in this field is the photoelectrolysis of water using TiO2 [33,34,35]. In 1972, Honda and Fujishima [33], made a significant breakthrough in photocatalysis research when they discovered that photoelectrolysis of water could take place in a two-electrode electrochemical assembly involving a platinum electrode and TiO2 under UV irradiation [36]. Figure 2 shows a schematic of the experimental setup used for photoelectrochemical water splitting [37]. In this configuration, the TiO2 electrode (anode, oxidation reaction site) absorbs ultraviolet light, exciting and transferring electrons to the platinum electrode (cathode, reduction reaction site), resulting in hydrogen production at the cathode. This finding represented one of the first demonstrations of hydrogen production from a cost-effective and clean energy source, contrasting sharply with the traditional hydrogen production methods that typically involve degassing and reforming of natural gas [36]. Fujishima and Honda’s findings paved the way for further advancements in photocatalysis. Subsequently, Nozick discovered that incorporating noble metals into the photocatalytic process could eliminate the need for an external potential and enhance photoactivity [38].

Figure 2.

An experimental setup for photoelectrochemical water splitting [37].

3. Mechanism of Photocatalysis

Semiconductors, particularly metal oxides, are widely recognized as the most effective photocatalysts due to their distinct properties. The band gap refers to the energy difference between the conduction band (CB) and the valence band (VB) of electrons. Specifically, it indicates the minimum energy required to excite an electron from a state in the VB to a state in the CB. The size and presence of this band gap classify materials as insulators, semiconductors, or conductors. For instance, conventional semiconductors like silicon (Si) have a band gap of 1.2 eV, whereas wide-band-gap semiconductors have band gaps ranging from 2 to 4 eV [39,40,41,42]. The mechanism of photocatalysis has been summarized into three steps as follows [43,44,45]:

- Light Absorption and Electron Excitation

When a semiconductor like TiO2 absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap, an electron is excited from the VB to the CB, resulting in a hole in the VB:

: Electron in the CB

: Positive hole (electron hole) in the VB

- 2.

- Separation and transport of carriers

Electrons and holes must separate before recombination and travel to the TiO2 surface to catalyze chemical reactions. If these carriers recombine, the energy is wasted as heat and the photocatalytic reaction cannot proceed.

- 3.

- Surface reactions (oxidation and reduction)

- -

- Reactions of pores (oxidation): pores (h+) are strongly oxidizing and accept electrons from adsorbed molecules (e.g., water or hydroxide ions). The most important oxidation reaction is the production of the hydroxyl radical (OH.):

H2O + h+ → H+ + OH.

or

Hydroxyl radical is one of the strongest oxidants in the environment that can oxidize organic compounds and convert them into carbon dioxide and water.

- -

- Electron Reactions (Reduction): electrons in the CB can reduce oxygen molecules adsorbed on the TiO2 surface to superoxide radicals :

The superoxide radical can also oxidize pollutant compounds directly or through the production of other radicals.

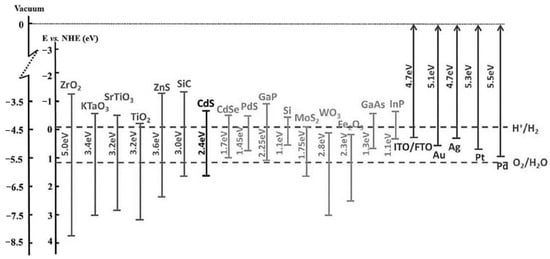

Figure 3 presents the band gap energies of the most commonly used semiconductors in photocatalysis applications.

Figure 3.

VB, CB and band gap energies of various semiconductor-based photocatalysts in relation to the splitting potentials for water into hydrogen and oxygen. CB: conduction band, VB: valence band normal, NHE: normal hydrogen electrode [46].

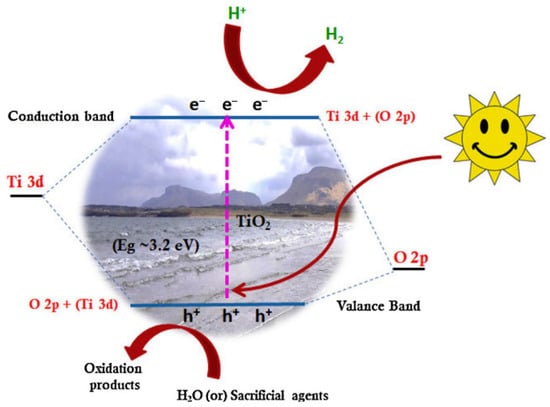

4. Photocatalytic Evolution of Hydrogen

The process of forming electron–hole pairs through light is called excitation. When an electron is excited, it can recombine with a hole, releasing the energy from the excitation in the form of heat [47,48]. The recombination of electron–hole pairs is a non-productive process that runs parallel to the main reaction pathway. This phenomenon causes a significant portion of the absorbed light energy to be converted into heat or light, making it unavailable for chemical reactions, thus decreasing the overall efficiency. Therefore, the development of effective photocatalysts often focuses on extending the lifetime of the generated charges and enhancing the separation of electron–hole pairs through various methods based on structural, physical, and surface properties. Additionally, the generated electron–hole pairs can drive reduction and oxidation reactions, acting as a catalyst for electrochemical processes such as hydrogen and oxygen evolution. Photocatalytic reactions are generally classified into two types-heterogeneous and homogeneous photocatalysis- based on the phases of the photocatalyst and the reactants. Homogeneous photocatalysis occurs when the photocatalyst and reactants are in the same phase, with photofenton systems being the most common homogeneous photocatalysts. In contrast, heterogeneous photocatalysis involves a catalyst that exists in a different phase from the reactants. This type of photocatalysis encompasses a range of reactions, including total or mild oxidation, hydrogen production, dehydrogenation, removal of gaseous pollutants, deuterium-alkane isotope exchange, water detoxification, and metal precipitation. The discussions and results presented in this paper are related to heterogeneous photocatalysis reactions, in which the semiconductor (TiO2) is in the solid phase and the reactants are in the liquid phase [49,50,51].

4.1. Photoelectrolysis of Water

Methane reforming serves as the primary method for the mass production of hydrogen; however, various attempts have been made to develop eco-friendly and cost-effective alternatives for H2 production via water electrolysis, as follows [52,53,54,55]:

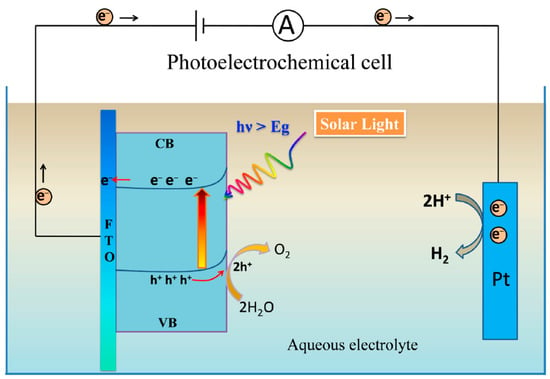

The Gibbs free energy for the water-splitting reaction is equal to 273 kJ.mol−1, categorizing it as a non-spontaneous reaction. Photoelectrolysis of water, which uses a semiconductor photocatalyst to produce oxygen and hydrogen, is a promising method for converting solar energy into carbon-free, clean H2 fuel. Typically, photoelectrocatalysis involves three main steps: (1) light absorption by a semiconductor, resulting in the formation of holes in the VB and electrons in the CB; (2) charge separation and migration to the surface; and (3) evolution of O2 or H2 at the electrodes. The efficiency of photoelectrolysis depends on the kinetics of these steps and the thermodynamic equilibrium [52,53,54,55]. In a typical photoelectrocatalytic assembly, photons with sufficient energy (hν ≥ band gap, Eg) can excite electron–hole pairs capable of overcoming the activation energy required for photoelectrolysis. It should be noted that the band gap energy is the minimum energy required to excite an electron from the VB to the CB. This energy directly determines the portion of the light spectrum a semiconductor can utilize [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Key processes in photoelectrolysis include light absorption, production of electron–hole pairs, surface reactions, surface oxidation and reduction, and charge transfer, where holes (h+) move to the surface of the photoanode and electrons flow to the auxiliary electrode (see Figure 4) [61].

Figure 4.

A schematic diagram of an n-type semiconductor used in photoelectrochemical water splitting; h+: hole, e−: electron, CB: conduction band, VB: valence band, h: Planck constant, : photon frequency, and Eg: Band gap energy [61].

The essential requirements for photoelectrodes generally include high chemical stability, low production cost, a low recombination rate of generated electron–hole pairs, high conductivity, and efficient charge transfer at the surface. In addition, a photoelectrode material requires a more positive valence band edge than the oxidation reaction potential (typically that of oxygen evolution) and a more negative CB edge than the reduction reaction potential to effectively produce H2 from water. Given the use of sunlight for the photoelectrochemical splitting of water, it is crucial for the semiconductor to absorb a significant portion of visible light. Figure 3 illustrates the most common semiconductor band energies and band edge positions for various materials (such as silicon, germanium, cadmium selenide, and silicon carbide) that have been proposed for photoelectrolysis [62]. However, these proposed semiconductors are prone to severe photocorrosion and chemical instability in aqueous electrolytes. In contrast, transition metal oxide photoelectrodes, such as titania, offer an appropriate band edge potentials for both the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), along with enhanced photoelectrochemical and chemical stability [62].

4.2. Electroless Photocatalytic Generation of Hydrogen

Electroless refers to an electrochemical reaction that occurs without the application of external electricity, and it is well known in various fields of electrochemistry. In this paper, electroless H2 evolution specifically denotes the photocatalytic reaction that takes place without an external current or voltage, during which both oxidation reactions and H2 emission occur on the same semiconductor surface. The sacrificial electroless emission method is widely used in academic research because it allows researchers to evaluate the true efficiency and kinetic potential of a new photocatalyst for the HER, without being limited by the very slow OER. This type of photocatalytic reaction is commonly observed in suspended particles within an aqueous base photoreactor [63,64,65,66].

5. Titanium Dioxide (TiO2)

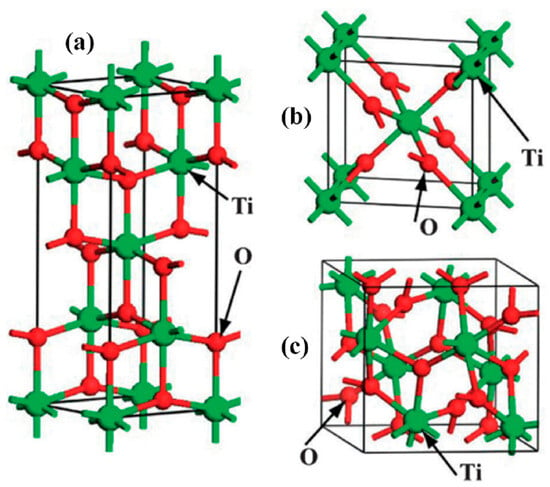

Titanium dioxide with the chemical formula TiO2, is a non-toxic, environmentally friendly, and corrosion-resistant material that has been utilized as a white pigment, as well as in sensors, solar cells, photocatalysts, and drug delivery since the early 20th century [67,68]. In the 1960s, titania was discovered to be sensitive to the ultraviolet range of sunlight. However, it was the groundbreaking work of Fujishima and Honda [67] on water splitting using TiO2 that popularized its application as a photocatalyst. This phenomenon, in which TiO2 can produce electron–hole pairs under light irradiation, facilitates the splitting of water into oxygen and hydrogen. It is recognized as a highly promising energy generator for addressing future energy crises [68]. Since then, titanium dioxide has become one of the studied compounds in materials science. This substance commonly exists in three crystal forms: anatase (tetragonal), rutile (tetragonal), and brookite (orthorhombic) (Figure 5) [69].

Figure 5.

Three common crystalline forms of TiO2: (a) anatase, (b) rutile, (c) brookite [70].

Among the various crystalline forms of TiO2, rutile is the most thermodynamically stable [71]. However, both anatase and rutile play significant roles in various applications. Table 1 summarizes the physical and chemical properties of these three phases [72,73,74]. For instance, anatase exhibits better charge transfer than other TiO2 polymorphs, making it the preferred phase for photocatalytic and electrocatalytic applications [75,76]. However, the performance of these polymorphs could be significantly impacted by contamination with various elements. For instance, boron-doped TiO2 (TiO2-B) has shown improved charge transport, making it more suitable for batteries compared to anatase, rutile, and other forms of amorphous TiO2 [77,78]. The transition from amorphous TiO2 to anatase, influenced by factors such as structural strain, impurities, and particle size, occurs around 300–400 °C, while the transition from anatase to rutile occurs at 500–700 °C [72,78]. Although rutile is the most stable form of TiO2, with a lower energy gap than other TiO2 polymorphs, it is not a suitable candidate for photocatalytic performance [79]. Anatase, with a band gap energy of 2.3 eV, is unstable up to 600–1000 °C. Despite being less stable than rutile, anatase is primarily studied in photocatalytic fields [77]. This is because the large energy gap of anatase is only activated under UV light. Thermodynamically, excited electrons in anatase (E° = −0.66 V compared to SHE) can reduce H+ to hydrogen, while electron holes (E° = 2.54 V compared to SHE) can oxidize water to oxygen or reduce organic pollutants [72].

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of anatase, rutile and brookite [72].

6. Nanostructures

Since the discovery of carbon nanotubes by Lijima in 1991 [73], many efforts have been made in nanotechnology, particularly in the field of chemistry, physics, biomedicine, and materials science. Nanostructures exhibit significant changes in their chemical and physical properties compared to their bulk state, often showcasing unique characteristics [53,80,81,82,83]. A “nanomaterial” is defined as a material that measures less than 100 nm in at least one dimension. Based on this definition, the common structural features of zero-dimensional (D0), one-dimensional (D1), two-dimensional (D2), and three-dimensional (D3) nanomaterials are illustrated [84]. The most notable advantage of nanomaterials is their increased specific surface area.

Although researchers have predominantly focused on carbon and carbon-based nanomaterials, transition metal oxide nanomaterials have gained significant attention over the past 20 years. Among them, TiO2-based nanomaterials stand out due to their distinct functional characteristics. They have been explored in various fields, including electrochromic devices, self-cleaning technology, sensors, biomedical coatings, photovoltaics, water splitting, supercapacitors, batteries, and CO2 recovery.

Among TiO2 nanostructures, anatase and rutile are widely used in photocatalytic and electrocatalytic applications. Studies indicate that anatase is a more efficient reaction catalyst under sunlight compared to rutile, thanks to its light absorption capacity and lower production cost, even though it has a wider energy gap, as shown in Table 1. The catalytic activity of TiO2 is influenced by several parameters, including specific surface area, crystallinity, and morphology. However, the large band gap and low conductivity pose challenges for electron transport, limiting the potential applications of TiO2. To address these issues, various strategies have been employed to modify TiO2, aiming to reduce its energy gap and enhance conductivity. Research indicates that the energy gap of TiO2 can be effectively reduced by decorating it with noble metals like palladium, platinum, gold, and copper [62]. Additionally, introducing point defects in TiO2-such as (a) interstitial titanium (Ti), (b) oxygen vacancies (VO), which are responsible for the electrical conductivity of TiO2, or (c) interstitial hydrogen (H), and (d) substitutional impurities, can generate free electrons in the system, thereby increasing electrical conductivity [81,82,83]. Notably, the formation of oxygen vacancies is often accompanied by the creation of interstitial titanium and the migration of titanium atoms to nearby interstitial sites, which can occur on the surface, subsurface, or core of TiO2 nanocrystals [72]. Naldoni et al. [85] demonstrated that the substantial creation of oxygen vacancies, along with the formation of Ti3+ sites, yields unique electronic properties. Chen et al. [75] reported a notable increase in electrical conductivity with increased oxygen deficiency in TiO2. Similarly, MohajerNia et al. [76] also showed that the optimal formation of point defects in the structure of TiO2 nanotubes reduces electrical resistance compared to pure TiO2 nanotubes (TNTs) [77]. These findings suggest that the configuration of the nanotubes significantly influences their conductivity. In this context, the likelihood of recombination of electron–hole pairs is higher in nanoparticles due to the random electron transfer paths [83,86]; in contrast, one-dimensional structures, such as nanotubes, demonstrate superior performance. Research on the structure of TNTs suggests that a one-dimensional configuration leads to high mobility, increased performance, a high specific surface area (high surface-to-volume ratio), improved carrier collection efficiency, and enhanced mechanical strength [83,86,87,88,89,90].

7. Formation Mechanism of TNTs

So far, TNTs have been produced using various methods, including hydrothermal [78], sol–gel [91], chemical vapor deposition [92], atomic layer deposition [93], and electrochemical oxidation [94,95]. Table 2 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

Table 2.

Comparison of three methods in making TNTs [96].

7.1. Hydrothermal Method

In the hydrothermal method, TiO2 or its raw materials are first dissolved in concentrated soda, as the raw materials must be used in solution form within the autoclave. After the hydrothermal process at temperatures between 110–150 °C, the raw materials are converted into nano-sized titanates. The next step involves washing the prepared nanotubes with dilute acid or water. While this method appears straightforward and quick, several factors significantly influence the process. For TiO2 raw materials, these factors include temperature, reactant concentration, and hydrothermal time. In the washing step, factors such as washing time, acid concentration, and the sequence of washing with acid and other solutions also play a significant role in determining the morphology and the physical and chemical characteristics of the final nanotubes [96].

7.2. Using the Template Method

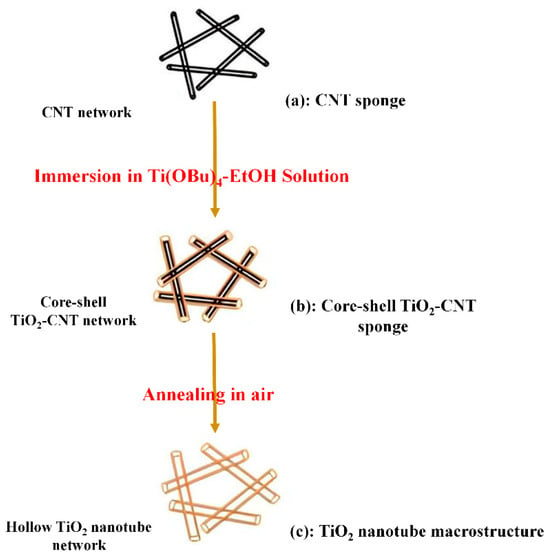

The preparation of titanium dioxide nanotube structures using a template takes place in three stages (Figure 6):

First step: a porous hydrophobic carbon nanotube (CNT), produced by the CVD method, is immersed in an ethanol solution containing tetrabutyl titanate C16H36O4Ti or TiC4H9O as a reactant. The sponge CNTs, which have a porosity of 99%, allow for the rapid and efficient penetration of reactive TiO2 into the cavities.

Second step: the sponge CNTs containing TiO2 are placed in water. During this process, amorphous reactive TiO2 forms and covers the surface of CNTs, resulting in the formation of a TiO2-CNT porous core and shell.

Third step: the TiO2-CNT porous structure is calcined at 450 °C for 2 h to eliminate the CNT background, leading to the formation of macro-sized TiO2 nanotubes. The porous structure remains unchanged during the transformation from TiO2-CNT to the TiO2 structure [97].

Figure 6.

Steps of forming porous nanotubes using a mold, CNTs: carbon nanotubes.

7.3. Atomic Layer Deposition Method

This method is a gas-phase thin film deposition technique that employs self-healing surface reactions. In recent years, it has attracted significant interest from scientists for its ability to produce high-quality thin films and precisely controlled molecular structures. The atomic layer deposition (ALD) process involves successive surface reactions, with each stage resulting in the formation of a single layer at each stage. Thanks to its inherent sequential nature and self-limiting surface reactions, the ALD method effectively regulates the atomic layer growth, allowing for coherent films with high order and controllable thickness [93].

7.4. Sol–Gel Method

In this method, TNTs were synthesized through the polymerization of titanium tetraiso-propoxide (C12H28O4Ti) or (Ti(OC3H7)4) using a gel formed with the compound di-benzo-30-crown-10, which has a cholesterol substitution, as a binding template. The rate of hydrolysis and density of (Ti (OC3H7)4) is significantly higher than that of silicon alkoxides, which complicates the control of connectivity and morphology in the synthesis of TiO2 organic-inorganic hybrids. In this study, the TiO2 structure was synthesized based on the growth of organic-mineral hybrids in 1-butanol through the hydrolysis of (Ti (OC3H7)4) in a humid atmosphere. The dibenzo-30-crown-10 compound with cholesterol substitution can gel organic solvents such as acetic acid, acetonitrile, acetone, ethanol, 1-butanol, 1-hexanol, dimethyl sulfoxide, and dimethylformamide, even at concentrations below 0.1% of the gelling agent. These results clearly indicate that the compound acts as an effective gelling agent [98].

7.5. Electrochemical Oxidation Method

7.5.1. Principles, History and Mechanism

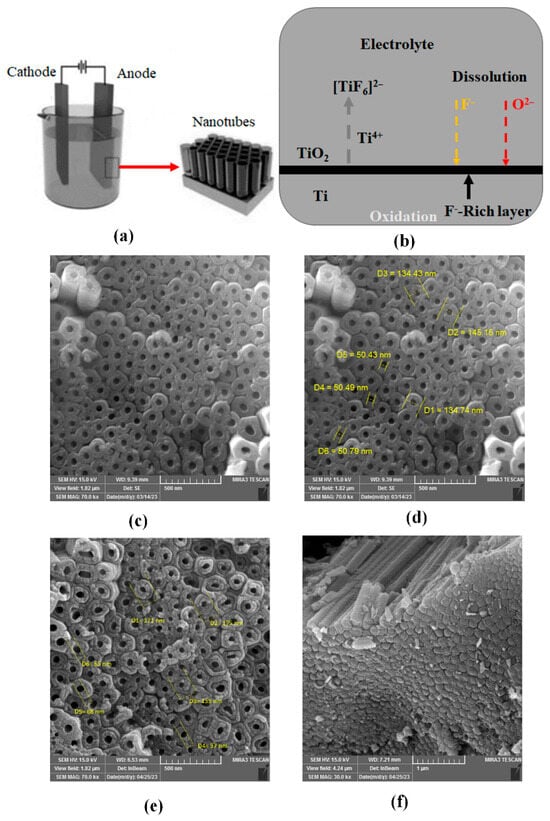

Among the various manufacturing methods, electrochemical oxidation has emerged as a simple and efficient approach for producing highly regular and parallel nanotube arrays with controllable lengths and diameters, all while maintaining full connectivity to the bitumen layer. This method is also more cost-effective in terms of time and price compared to other methods [99]. Electrochemical oxidation, also known as anodic oxidation, is an electrochemical process that forms a protective oxide film on the surface of a metal. In this process, the metal being electrochemically oxidized is connected to the positive terminal of a DC power supply, classifying it as the anode. By creating optimal conditions and ensuring the presence of necessary ions in the electrolyte, such as those found in baths containing fluoride ions, TiO2 nanotubes with highly regular and uniform structures can be produced. The dimensions of the resulting nanotubes can be easily and accurately controlled (as shown in Figure 7) [100] a capability that other methods lack [53].

Figure 7.

(a) Electrochemical oxidation process and conventional anode structures formed on metal, (b) schematic of electrochemical oxidation, (c–e) formation of TiO2 in the presence of fluoride ions in the electrolyte and (f) decoration on TNTs [100].

After several years of research on the electrochemical oxidation of aluminum and its optimization for creating alumina nanotubes [101,102,103,104], Asifpour Dezfuli [80] reported the first instance of self-organized TiO2 nanotube formation in 1984. Later, in 1999, Zwilling et al. [81] observed the self-organization of porous TiO2 through the electrochemical oxidation of a titanium-based alloy in an acidic fluoride-based electrolyte. Subsequently, in 2001, Gang et al. [82] successfully produced an array of titanium oxide nanotubes exceeding 500 nm in length by electrochemical oxidation of titanium in aqueous electrolytes containing HF.

Over time, research on TiO2 nanotubes has increased. Kai et al. [105] adjusted the pH of aqueous electrolytes using KF and NaF, which reduced the chemical dissolution of the oxide and resulted in nanotubes with several microns in length. Additionally, Paulose et al. [106] synthesized TiO2 nanotubes exceeding 1000 microns in length by employing organic electrolytes such as ethylene glycol, diethylene glycol, formamide, and dimethyl sulfoxide, along with NH4F, NaF, KF, HF, and Bu4NF to provide fluoride ions. Researchers have also reported the formation of titanium oxide nanotube arrays through the electrochemical oxidation of titanium in fluoride-free solutions, such as HCl combined with H2O2. The ongoing development of regular TiO2 nanotubes, with lengths reaching hundreds of micrometers in organic and fluoride electrolytes like ethylene glycol and HF, has inspired research into their various applications [84]. Based on other studies [77,78,79,93,95,96,97,107], the steps involved in forming an array of smooth, and toothless titanium oxide nanotubes can be summarized as follows:

1—The growth of the oxide layer on the metal surface occurs through the interaction of the metal with and ions. After the initial oxide layer is formed, these anions migrate from the oxide layer and react with the metal at the metal/oxide interface.

2—Ti4+ metal ions mitigate from the metal at the metal/oxide interface. Under the influence of an existing electric field, Ti4+ cations are removed from this interface and move towards the oxide/electrolyte interface.

3—Dissolution occurs in the presence of an oxide field at the oxide/electrolyte interface. The applied electric field causes the Ti-O bond to become bipolar, weakening it and leading to the dissolution of metal cations. Dissolved Ti4+ cations in the electrolyte and free anions penetrate to the metal/oxide interface, as described in step 1, to react with the metal.

4—Chemical dissolution of the metal or oxide by the electrolyte results in the dissolution of the metal or oxide formed within the electrolyte.

Thus, the growth of the anodic oxide layer is accompanied by the ion production/transfer process, facilitated by a strong electric field. The formation of oxide at either the oxide/electrolyte interface or the oxide/metal interface depends on the speed of ion migration (Ti4+ moving outward and moving inward). In fact, oxide can grow on either the internal or external surface. However, in the case of TiO2, the oxide primarily grows at the oxide/metal interface.

With the onset of electrochemical oxidation, the mutual reaction between surface Ti4+ ions and ions leads to the formation of the primary oxide layer in the electrolyte. In the electrochemical oxidation of the metal, Ti4+ ions and electrons are generated, as described below:

Hydrogen gas will be emitted at the cathode.

The complete formation of oxides takes place according to:

In the presence of F−, fluorine ions attack the oxide layer. When an electric field is applied, it drives the ions to move within the anodic layer, where they react with various species as below:

Figure 8 illustrates the growth stages of titanium oxide nanotubes during the electrochemical oxidation process at a constant voltage. At the beginning of this process, the relatively strong electric field causes dissolution under the field to dominate over chemical dissolution (Figure 8a). Subsequently, small holes form due to the local dissolution of the oxide layer (Figure 8b), which then serve as centers for porosity formation. After the holes are converted into porosity, the porosity density increases. Porosity growth results from the internal movement of the oxide layer at the end of the barrier layer (Figure 8c,d). Ti4+ ions migrate from the metal to the electrolyte/oxide interface, dissolving in the electrolyte. The rate of oxide growth at the metal/oxide interface equals the rate of oxide dissolution at the electrolyte/porous end interface, causing the layer thickness to remain unchanged. However, as the depth of the porosity increases, the barrier layer penetrates deeper into the metal, creating small holes between the pores, which ultimately lead to the separation of the pores and the formation of nanotubes (Figure 8e) [108].

Figure 8.

Schematic of the arrangement of nanotubes during constant voltage electrochemical oxidation: (a) formation of the oxide layer, (b) creation of holes in the oxide layer, (c) growth of these holes into the pores, (d) presence of metallic parts between the pores and dissolution of the matrix, and (e) the expanded arrangement of nanotubes from the top view [108].

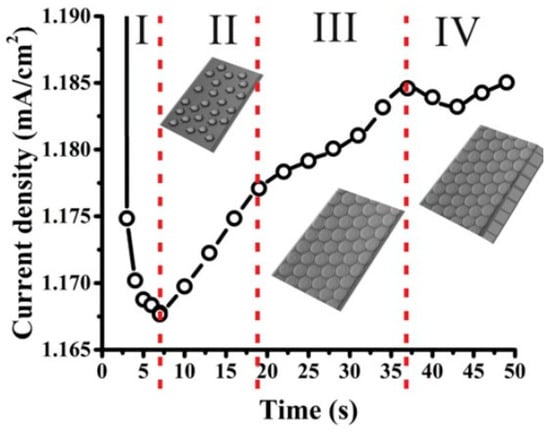

The current–time curve of the electrochemical oxidation process of TNTs is shown in Figure 9. This curve, characteristic of nanotube formation, is a typical current–time curve that can be divided into distinct stages.

Figure 9.

Current–time curve recorded during the electrochemical oxidation process [109].

In the initial stage (I), a compact oxide layer of a certain thickness forms, leading to a drop in the electric field and, consequently, the current.

In the next stage (II, III), F− ions attack the thin TiO2 layer on the oxide surface, resulting in the formation of irregular nanopores. During this stage, the current increases due to the formation of a reactive region.

In the final stage (IV), the current decreases once more as the nanopores develop. The oxide layer becomes thicker, restricting electrolyte penetration, and causing a subsequent decline in the electric field [74,94].

After the formation and dissolution of the oxide layer and reaching equilibrium, TNTs or nanopores can continuously grow under specific conditions, including voltage, temperature, and concentration. The transition from nanopores to nanotubes is a consequence of the presence of a water-soluble TiF6 layer. Thus, water is a key factor in the formation of self-organized nanotubes, serving not only as an oxygen source for oxide growth but also aiding in dissolving the cell walls in the electrolyte during electrochemical oxidation. For instance, in an electrolyte with very low water content, TiO2 nanopores are formed instead of nanotubes because the chemical dissolution of the fluoride-rich layer cannot occur.

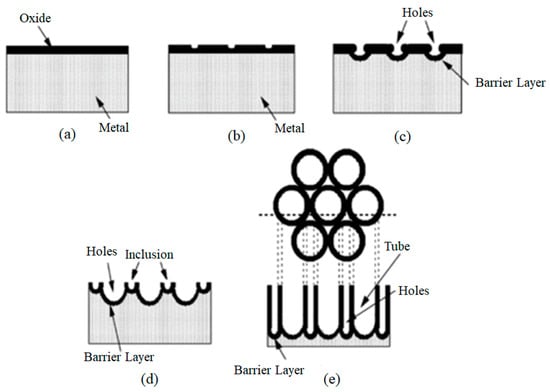

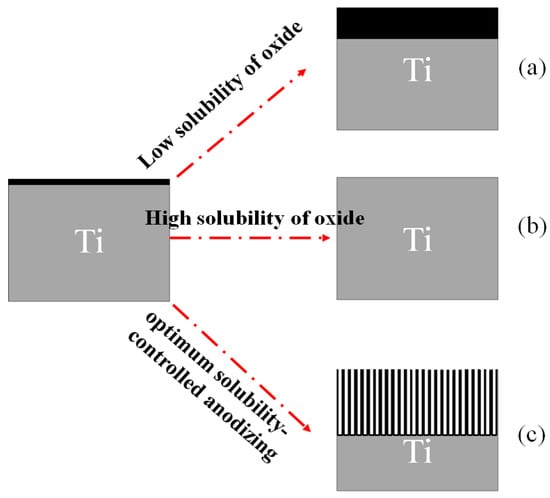

In general, applying a positive voltage (the anodic potential) to the Ti electrode can result in three different reactions:

If the formed oxide layer is completely insoluble in the electrolyte (e.g., H2SO4 and H3PO4), a thin, compact oxide layer grows on the Ti surface, (Figure 10a).

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of possible anodic structures of TiO2 [88]. (a) a thin, compact oxide layer grows on the Ti surface; (b) no oxide is formed on the metal surface; (c), a porous or tubular TiO2 layer is formed.

If the formed oxide layer is completely soluble in the electrolyte (e.g., pure HF), electropolishing occurs. In this case, the layer dissolves simultaneously, and no oxide is formed on the metal surface, (Figure 10b).

If the oxide is partially soluble in the electrolyte (e.g., an organic electrolyte based on F-containing materials), a porous or tubular TiO2 layer is formed once dissolution reaches a stable state. (Figure 10c) [88].

7.5.2. Effects of Parameters in Electrochemical Oxidation Method

Considerable focus has been devoted to studying the growth of nanotubes, as this process is significantly influenced by conditions including the electrolyte’s concentration and acidity (pH), the applied anodization voltage, the reaction time, and the operating temperature. Hence, the following section delivers an in-depth analysis of how these key parameters govern the synthesis and morphology of TNTs [110].

Effect of Electrolytes

The electrolyte plays a crucial role in the growth and formation of TNTs, since its nature, concentration, and pH directly affect the electric field intensity, the oxide layer dissolution rate, and ultimately the size and uniformity of the nanostructure. Under identical conditions, different electrolytes can generate varying electric field strengths, leading to differences in nanotube diameter or packing density. Fluoride-containing electrolytes such as NH4F/CH3COOH, H2SO4/HF, and Na2HPO4/NaF are among the most common types, significantly influencing the length and diameter of TNTs. In general, two categories of electrolytic media are used for TNT synthesis:

- Aqueous (acidic) electrolytes—characterized by high water and oxygen content, resulting in greater current densities and faster oxide dissolution.

- Organic or neutral electrolytes—with higher viscosity and lower water content, enabling better control over growth, more uniform structures, and longer tube layers.

In organic electrolytes such as (NH4)2SO4/NH4F, longer and more self-organized nanotube arrays are typically obtained because the oxide dissolution at the tube top is inhibited. Increasing HF concentration up to about 0.15 M leads to an optimal porous structure, whereas concentrations below or above this value hinder proper nanotube formation. The pH effect is also significant; acidic electrolytes produce thinner oxide layers due to higher dissolution rates. Studies have shown that electrolytes like malonic acid or H2SO4 yield well-ordered nanotubes with tunable diameters. Furthermore, the use of fluoride-free electrolytes, such as chlorine- or perchlorate-containing solutions, has recently enabled ultrafast TNTs growth for instance, formation in chlorine-based solutions takes less than 10 min compared to roughly 17 h in fluorinated media [110,111,112,113,114,115,116].

Another noteworthy finding is that reusing the electrolyte from a previous anodization run enhances its conductivity and results in nanotubes with larger pore diameters and thinner walls. This is attributed to dissolved titanium ions that increase ionic mobility and accelerate the reaction process during subsequent anodization. In summary, the chemical and physical characteristics of the electrolyte—including its type, pH, fluoride concentration, water content, and whether it is fresh or reused—play a decisive role in defining the diameter, length, order, and overall quality of titanium dioxide nanotubes [117].

Effect of Electrolyte pH

The pH of the electrolyte is the key to achieving growth of the high-aspect ratio nanotubes and it can affect the self-organization behavior of TNTs. The difference in the pH leads to significant variations in the pore diameter. The differences in thickness are attributed to the pH-dependence of the oxide dissolution rate, i.e., the dissolution rate at low pH is much greater than at high pH. Therefore, the pH alters the thickness and diameter of the pores. It has been reported that a mixture of 1 M Sodium hydrogen sulfate monohydrate and 0.1 M KF with 0.2 M Sodium citrate tribasic dehydrate electrolyte shows the variation in the nanotube length from 380 nm to 6 µm and tube diameters from 30 to 110 nm, which is due to the electrolyte pH and anodization potential several other reasons. The formation of hydrolysis product at the working electrode leads to a decreases in pH; thus, the local acidification is established. Tailoring the local acidification could promote the TiO2 dissolution, thereby providing more protective environment against the dissolution along the tube mouth, thus, longer tubes were obtained. Hydrogen evolution and OH− species formation take place at the counter electrode [118,119,120].

Effect of Applied Voltage

The applied voltage is a dominant factor that dictates the architecture of TiO2 nanotube arrays, governing their pore diameter, inter-pore spacing, and overall film thickness across a broad spectrum. Both the voltage level and the anodization duration significantly shape the resultant morphology. At low applied voltages, the resulting structures are relatively short, measuring a few hundred nanometers in length and tens of nanometers in diameter. During short anodization times, the nascent tubes remain interconnected by rings along their sidewalls. Conversely, prolonged anodization leads to the dissolution of these connecting rings, resulting in individual, separated tubes. Optimal structural regularity is generally achieved around an applied voltage of 20 V. Films fabricated at potentials below 20 V form a nanoporous structure that is notably thinner, as the relatively low current density is insufficient to support further thickening of the oxide layer. When the voltage is set between 22 V and 30 V, the resulting porous structure is tubular but tends to be irregular. Potentials exceeding 30 V often trigger breakdown events at the film/substrate interface, leading to the formation of large, cracked regions of porous oxide, sometimes reaching micrometer-scale diameters. The structural progression with increasing voltage is as follows: at low voltages, the morphology resembles porous alumina; as voltage rises, the surface transitions to a particulate or nodular appearance. Further increases cause this particulate nature to vanish, yielding discrete, hollow, cylindrical tube features. Beyond 40 V, the defined nanotube structure is entirely lost, and a random, sponge-like porous architecture is established. Chemical dissolution of the TiO2 layer is inseparable from TNT formation. As previously noted, the dissolution rate is highly pH-dependent. Because the formation of the hexafluorotitanate complex creates an acidic environment (low pH) at the base of the tubes, growth proceeds preferentially downwards into the metal foil, which is essential for forming the tubular geometry. When organic electrolytes are utilized, a higher anodizing potential imposes a greater driving force for dissolution by F− ions, consequently leading to larger pore sizes and greater tube lengths. Conversely, in acidic electrolytes, the already high dissolution rate (due to local acidification at the tube bottom) means that applying excessive potential pushes the dissolution rate too high, resulting in the complete erosion of the oxide layer with no tube formation observed. Therefore, a pragmatic approach dictates using lower voltages for acidic electrolytes and higher voltages for organic electrolytes [121,122,123,124].

Effect of Electrolyte Temperature

The temperature of the electrolyte plays a critical role in the successful formation and stability of self-organized TNTs when using a glycerol-based solution. Temperatures above 40 °C are detrimental, yielding only unstable aggregates of tubes on the titanium surface, precluding the creation of a regular and mechanically robust nanotubular architecture. Analysis of SEM imagery across a temperature gradient (specifically at 5, 10, 15, and 20 °C) reveals a strong temperature-dependent transition in morphology:

- At 5 °C, the result is a thick, porous oxide layer.

- At 10 °C, the pores are visible but exhibit irregular ordering instead of the characteristic well-defined pattern.

- A significant improvement is seen at 15 °C, where regular pores are achieved, with diameters typically between 45 nm and 50 nm. Interestingly, at this temperature, secondary, smaller pores (two to three) are sometimes observed nucleating inside the primary pores.

- When the temperature is raised further, the resulting pores are highly ordered and exhibit a larger diameter of approximately 84 nm.

This data clearly indicates that pore formation and ordering scale positively with increasing electrolyte temperature. This phenomenon is likely due to the reduction in electrolyte viscosity at higher temperatures, which facilitates a faster etching rate. Rapid etching dissolves the oxide layer more quickly, promoting pore formation. Conversely, at lower temperatures, the mobility of fluoride ions is restricted, resulting in a slower etching rate. This slow etching kinetics at the lower end of the spectrum prevents the formation of regularly ordered pore structures [125,126,127].

Effect of Current Density

Current density is a pivotal parameter in dictating the pore characteristics of TNTs, as it directly modulates the electrochemical etching rate. Elevated current densities lead to a cascade of effects: an increase in the electrochemical etching rate, a surge in power, and intensification of the electric field. This combined influence promotes the widening of initial pits before channel formation, thereby yielding discrete, individual pores. Augmenting the current density applied to the titanium foil results in a corresponding increase in the pore size of the TNTs. Therefore, carefully controlling the current density offers a means of precisely engineering tube diameter. Monitoring current density at a fixed voltage in fluoride-containing solutions provides insights into the progression of TNTs layer formation. Electrolytes containing fluoride exhibit a higher current density compared to their fluoride-free counterparts, with the current density increasing proportionally to the fluoride concentration within the range of 0–2 wt. %. This underscores the significant role of fluoride ions in the electrochemistry of TNTs formation. The fluoride ion concentration in the electrolyte is a key parameter. The aqueous electrolyte typically displays a higher current value than organic electrolytes.

The increase in current density, followed by a broad current maximum, signals distinct events: the initial event suggests the localized breakdown of a compact oxide layer, while the current maximum indicates the commencement of nanotube structure development [128,129].

Effect of Anodization Time

Anodization time exerts a profound influence on the mechanism governing (TNTs) formation. Insufficient anodization duration will entirely preclude the formation of TNT structures. Reports indicate a minimum time threshold for TNTs development. Reports established that at least 15 min are required for TNTs to appear, with longer durations promoting the creation of highly ordered arrays. Similarly, in another reserchs observed that only a nanoporous structure resulted from a 5 min anodization, with the distinct nanotubular structure only becoming clearly visible after 10 to 20 min. Very short growth periods (e.g., 5 min) yield TNTs that are both short and slender. However, exceptionally fast growth rates are possible under specific conditions. A study demonstrated the growth of highly ordered TNTs reaching a thickness of 7 μm in just 25 s by incorporating lactic acid into the electrolyte. They found that lactic Acid acts to inhibit localized dielectric breakdown of the anodic oxide at higher anodization voltages. This allows for significantly higher ion transport across the oxide film, resulting in exceptionally rapid tube elongation while preserving the functional integrity of the tubes. As a general rule, extending the anodization time directly correlates with an increase in TNT length. Nevertheless, there is an upper limit; anodization times extending beyond one hour can lead to the partial collapse of the tubes, which is attributed to excessive etching of the tube tops by fluoride ions [130,131,132].

Effect of Electrodes

The selection of the counter electrode (CE) material is another critical factor influencing the final aspect ratio of the TiO2 nanotubes (TNTs). Studies comparing various CE materials have compared various CE materials, including iron, carbon, stainless steel, and aluminum. According to reports, CEs including Ni, Pd, Pt, Fe, Co, Cu, Ta, W, C, and Sn were used for the development of TNTs. Their results indicated that the nature of the cathode material plays a vital role in the appearance of surface precipitate. The over potential of the cathode is a critical factor, which affects the dissolution kinetics of the Ti anode, in turn controlling the activity of the electrolyte and morphology of the formed TNTs. The more Ti dissolved in the electrolyte, the higher the electrolyte conductivity, which helps prevent debris formation. It appears that the different cathode materials led to the fabrication of different morphologies due to differences in their overvoltage within the test electrolyte. Hence, the arrangement of the cathode materials according to their stability in aqueous electrolytes is in the following order [133,134]:

Pt = Pd > C > Ta > A > Sn > Cu > Co > Fe > Ni > W

- Stainless Steel (SS): Produced short TNTs with thin (5–10 nm), non-uniform wall thickness, and inconsistent diameters between the top and bottom, leading to conical structures that easily collapse.

- Yielded an aspect ratio similar to carbon, but the top surface re-sembled that from the SS cathode, resulting in bases that were stable but tops prone to collapse. Al-formed TNTs were notably less robust than those from a carbon CE.

- Iron (Fe): Formed well-organized TNTs with high aspect ratios, though these were still less durable than those formed with carbon.

- Carbon (C): Consistently produced TNTs exhibiting the highest aspect ratios, largest diameters, and greatest lengths compared to other tested materials. The quality was comparable to that of a platinum (Pt) cathode, but carbon offers a significant cost advantage.

Furthermore, the nature of the cathode material impacts surface precipitation, with the cathode’s overpotential influencing Ti dissolution kinetics, which in turn dictates the electrolyte activity and morphology of TNTs. Increased Ti dissolution enhances electrolyte conductivity, which helps suppress debris formation. Finally, the spacing between the working electrode (WE) and the CE also governs the TNTs architecture.

- Decreasing the inter-electrode distance (e.g., from 4.5 to 0.5 cm) enhances electrolyte conductivity and titanium concentration. This results in TNTs with enlarged pore diameters, thicker walls, and wider inter-tubular spacing. The increased field strength and altered electrolyte properties are believed to drive the self-enlargement and separation of the nanotubes, leading to discrete, well-separated structures.

- Conversely, increasing the separation between electrodes causes the field strength at the anode to drop (due to higher IR), resulting in a significant decrease in pore size and a higher density of TNTs. The overall growth rate of the TNTs also diminishes with greater electrode separation.

Based on the above discussion, Table 3 briefly presents the comparative effects of morphology, synthesis method, and crystalline phase of titanium dioxide on the band gap.

Table 3.

A comparison between the amount of band gap energy, morphology and phase structure of TiO2 achieved with different syntheses methods.

8. Applications of TiO2 Nanotubes

As mentioned earlier, TNTs have found a wide range of applications in various industries due to their unique properties. In this section, several of these applications will be reviewed.

8.1. Development of Gas Sensors

Today, considering the advancements in technology and a focus on human safety and health, gas detection sensors have become essential, particularly in critical sectors like the oil and gas industry and nuclear power plants, where the sensitivity is vital for safe operations. Other significant applications are found in the medical field and disease diagnosis. Moreover, data from the US Energy Agency indicates that extracting oil from about two-thirds of US oil wells is not economically feasible. In harsh underground environments characterized by high temperatures and pressures, traditional electrical and electronic sensors often prove unreliable. This unreliability poses challenges for oil extraction companies in obtaining the precise and sensitive information necessary for effective extraction of oil from reservoirs. The detection power and sensitivity of sensors largely depend on their specific surface area in contact with the gas. Technological advancements have led to methods that enhance the contact area between sensors and gas, notably through the development of nanostructured coatings. These coatings, due to their exceptionally high specific surface area, are highly sensitive, able to detect even minimal concentrations of target gases compared to other coatings. Furthermore, modifying the energy gap of the TiO2 semiconductor coating, these gas sensors can identify various types of gases that cause changes in the energy gap of TiO2. TNTs exhibit superior photocatalytic properties compared to other forms of this oxide, enabling the significant reduction of pollution caused by ultraviolet radiation, which allows the sensors to maintain their original sensitivity to hydrogen [89].

8.2. Production of Hydrogen Gas

In recent decades, hydrogen gas has emerged as a significant focus in the renewable energy sector, particularly for use in combustion engines and battery-powered electric vehicles. However, because hydrogen is a gas at room temperature and pressure, it presents challenges for transportation and storage compared to liquid fuels. Existing methods for hydrogen storage include compressed hydrogen, liquid hydrogen, and chemical bonding between hydrogen, as well as storage materials, such as metal hydrides. Although a suitable transport and distribution system for hydrogen has yet to be developed, the ability to produce this fuel from a diverse range of clean sources makes it a viable alternative fuel. It is important to note that hydrogen fuel is not composed solely of pure hydrogen gas; it also contains small amounts of oxygen and other substances. Sources for hydrogen fuel production include natural gas, coal, gasoline, and methanol. Methods for hydrogen production include photosynthesis in bacteria and electrolysis of water using electric current or direct sunlight. For instance, by absorbing ultraviolet light, TiO2 in aqueous solution can decompose water into oxygen and hydrogen [142]. These reactions can be represented as follows:

Excitation of charge carriers in TiO2 semiconductor by light absorption:

TiO2 + 2hʋ → 2e− + 2hole+

At the TiO2 electrode surface:

H2O + 2hole+ → (1/2) O2 + 2H+

At the platinum electrode surface:

2H+ + 2e− → H2

The overall reaction is:

H2O + 2hʋ → (1/2) O2 + H2

The low efficiency of hydrogen production relying on the photocatalytic properties of TiO2, is primarily due to the fact that only a portion of sunlight-specifically, the ultraviolet region-can effectively excite this material to generate electrons and electron holes [142].

8.3. Treatment of Water and Industrial Wastewater

Today, human health and the environment face significant threats from various pollutants. With advancements in technology, we encounter toxic substances such as car exhaust, formaldehyde, benzene, and various types of fungi in our daily lives. Statistics indicate that in China alone, over one hundred thousand people die annually due to indoor pollution. Consequently, finding solutions to purify the environment has become a key objective for scientists worldwide. In this context, a new technology called photocatalysis has received significant attention. The most effective way to clean polluted water is through the use of a catalyst capable of addressing a wide range of pollutants. In this regard, metal oxides such as TiO2, ZnO, and WO3 are emerging as the best options. Following the discovery of the photoanodic capabilities of TiO2 in 1972, it was established that this material possesses strong oxidizing properties. As a result, TiO2 has drawn attention for its applications in environmental phenomena such as sterilization, disinfection, and pollutant removal [90].

8.4. Application as an Electrode

The use of TNTs as an electrode has numerous advantages:

- TNTs provide a high active surface area, which is crucial for catalytic applications.

- They remain stable in both acidic and basic environments.

- TNTs offer a direct charging path compared to powder-based electrodes [143].

9. Challenges of TiO2 as an Ideal Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Production

An appropriate photocatalyst for hydrogen production in hydroxide solutions must possess several key properties to efficiently promote the hydrogen production reaction during photocatalysis. These properties are outlined below, followed by a detailed discussion on why TiO2 is not a suitable electrocatalyst for this specific purpose [105,106,107,142,143,144].

(a) High catalytic activity: The electrocatalyst should exhibit significant intrinsic catalytic activity for the hydrogen production reaction, facilitating the rapid decomposition of water molecules into hydrogen ions (H+) and electrons (e−).

(b) Low overpotential: Overpotential refers to the additional voltage required to derive a reaction relative to its standard thermodynamic potential. An effective electrocatalyst should have a low overpotential for the hydrogen production reaction, indicating that it can initiate the process at a lower voltage, thereby enhancing efficiency.

(c) Stability: The photocatalyst must maintain stability under the electrochemical conditions of the hydrogen production reaction, which includes varying acidic and basic environments as well as exposure to high current densities.

(d) High surface area: A larger surface area provides more active sites for the catalytic reaction, increasing the overall efficiency of the process.

(e) High corrosion resistance: The photocatalyst must resist corrosion and degradation over extended periods, ensuring long-term performance.

(f) Availability and cost: It is preferable for the photocatalyst to consist of abundant and inexpensive elements to make large-scale hydrogen production economical.

Several of the factors mentioned above pose major challenges for TiO2, the most important of which are:

(i) Low catalytic activity: TiO2 exhibits relatively low intrinsic catalytic activity for the hydrogen production reaction.

(g) High overpotential: Due to its limited catalytic activity, TiO2 requires a higher overpotential to facilitate the hydrogen production reaction, necessitating a higher voltage to produce the same amount of hydrogen.

(k) Insufficient conductivity: TiO2 has relatively low electronic and ionic conductivity, which limits the flow of charge carriers (electrons and ions) to and from the catalytic sites. Efficient charge transport is crucial to ensure high rates of catalytic reactions in photocatalytic processes.

(l) Stability concerns: Although TiO2 is stable in many environments, it may not remain stable under conditions of varying pH or high current densities encountered during photolysis for hydrogen production.

To overcome these shortcomings, numerous improvement strategies have been proposed, which can be categorized into seven general groups. Given the similarities in the prerequisites for electrocatalytic, photoelectrocatalytic, and photocatalytic applications, these strategies have been successfully implemented in one or more of these fields.

10. Modification of TiO2 Nanotubes for Hydrogen Production

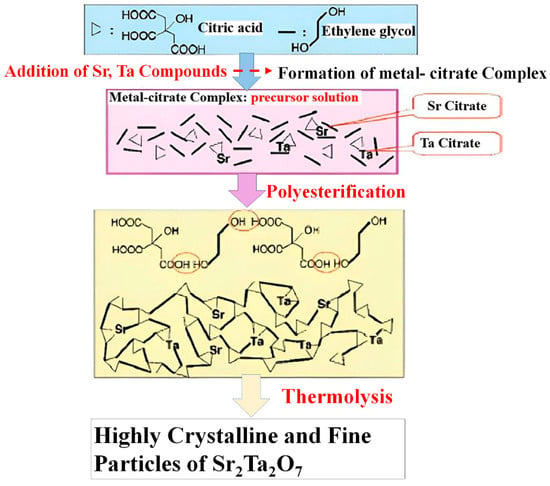

10.1. Polymerized Complex

A recent advancement in synthesis techniques is the polymerized complex method, as shown in Figure 11. This powerful and convenient approach enables the synthesis of complex crystalline metal oxides, even at low temperatures. The method consists of two basic steps: (1) the incorporation of an inorganic precursor into a polymer resin with dispersion at the molecular level, and (2) the subsequent calcination to remove the polymer and yield a crystalline metal oxide. The particle size produced by this method can be varied by controlling the calcination temperature [144].

Figure 11.

Schematic illustrating the synthesis steps of the metal oxide photocatalyst of Sr2Ta2O7 [144].

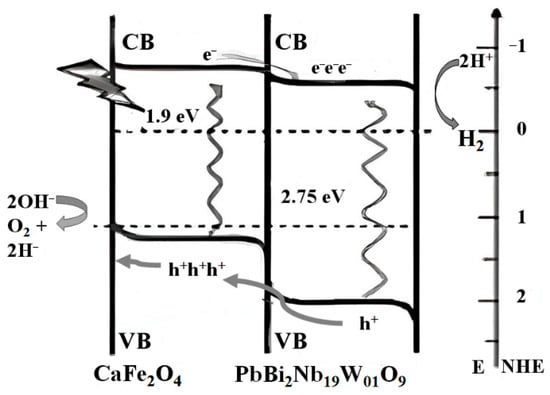

10.2. Compositing Titanium Dioxide with Other Semiconductors

The concept of using n-p composite semiconductors originated with the invention of the diode. The theory behind this idea is based on the creation of an internal electric field at the interface between two distinct semiconductors as illustrated in Figure 12. This internal electric field helps to prevent electron-hole recombination, thereby increasing photocatalytic efficiency [144].

Figure 12.

A schematic of composites made from n-type and p-type semiconductors; h+: hole, e−: electron, CB: conduction band, VB: valence band [144].

10.3. Surface Modification of TiO2

The surface of a photocatalyst is critical for hosting active sites that facilitate oxidation-reduction reactions and charge transfer. Therefore, surface modification is essential for achieving specific desired properties or functions. One of the most common approaches to surface modification is cocatalyst loading, which promotes surface redox reactions. For instance, Fujihara et al. [145] reported that water oxidation under visible light irradiation on WO3 in an aqueous solution containing Fe3+ as an electron acceptor could be enhanced by coating WO3 particles with a thin TiO2 layer. Their study indicated that the TiO2 layer provided adsorption sites for Fe3+ rather than Fe2+, allowing for more efficient O2 generation in the presence of Fe3+ ions. Similarly, Tabata et al. [146] used rutile TiO2 nanoparticles as a modifier on Ta3N5 to obtain a photocatalyst for O2 evolution in a two-step water splitting system that utilized the shuttle redox mediator IO3−/I− under visible light (>420 nm) in conjunction with Pt.

10.4. Composite Engineering

Controlling the morphology of TNTs through the production of composite materials is very effective in improving and tuning crystalline phases, crystallinity, and defects within the network. In addition, composite structures and the formation of heterogeneous junctions between TiO2 and other materials can alter the charge migration and the absorption spectrum. This occurs by creating and adjusting midband electronic states, resulting in the absorption of visible light by added materials. Studies have demonstrated that defects serving as preferential electron sites can suppress the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, and their stability can be enhanced through composite formation. Figure 13 illustrates a general model for photocatalysis on TiO2, where light absorption generates an electron–hole pair. The migration of the photo-excited electron and hole to the surface can provide favorable conditions for the reduction of protons (H+) to hydrogen gas [147]. Charge separation can be further enhanced by introducing features such as surface defects, where electrons and holes are trapped to prevent recombination. A structure with a narrower band gap can utilize visible light to generate electron–hole pairs, allowing the electron to migrate to TiO2, while the hole is trapped in the second material. The reduction reactions occur at separate levels, effectively reducing the probability of charge recombination [143,148,149,150].

Figure 13.

A general model of photocatalysis on TiO2, including the absorption of photons, the generation of electron–hole pairs, and the subsequent charge separation and migration to the surface; h+: hole, e−: electron, CB: conduction band, VB: valence band, Eg: Band gap energy [147].

10.5. Nanostructure Engineering

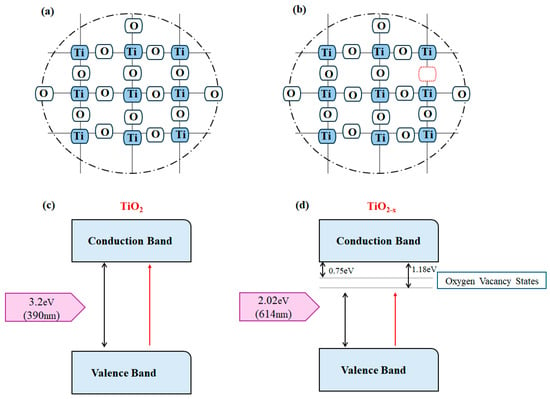

According to Figure 14, introducing defects through processes such as reduction in hydrogen environments has been shown to significantly enhance the conductivity of TiO2. The presence of point defects, including oxygen vacancies (VO) and interstitial cations (Ti3+), generates mid-gap energy states near the conduction and valence bands, resulting in a reduced energy gap. This narrowing allows for extended light absorption into the visible spectrum, making a notable improvement in the photocatalytic properties of the material [76]. Furthermore, these point defects provide active sites that facilitate catalytic activity [143,148,149,150]. TNTs are particularly effective as electrodes in applications such as water splitting, fuel cells, CO2 reduction, lithium-ion batteries, and supercapacitors. In addition to exploring point defects, extensive research has focused on modifying the chemical composition of TiO2 for electrode applications. For instance, Chen et al. [151], first synthesized black TiO2, which contains point defects, from white TiO2, which is nearly defect-free, using a hydrogenation process intended for improving hydrogen production. Their findings indicate that black TiO2 has a broader optical absorption range than white TiO2, leading to higher photocatalytic efficiency. This advancement is pivotal for utilizing TiO2 in photocatalytic water splitting. Consequently, numerous research groups are actively pursuing strategies to enhance the catalytic activity of TiO2 by employing various structural modifications to increase the hydrogen production rate [152].

Figure 14.

Schematic of crystal lattice of TiO2 (a) without defects and (b) with oxygen vacancy defects, along with possible band-gap electronic structure TiO2 (The red box indicates oxygen vacancies), (c) without defects, and (d) including oxygen vacancy, showing band Gap narrowing in the presence of oxygen vacancy in the oxygen-deficient TiO2−X. Not: The big black arrows indicate the band gap and the red arrow indicates the direction of electron transfer. The small black arrow also indicates the amount of band gap reduction due to the creation of oxygen vacancies.

10.6. Doping

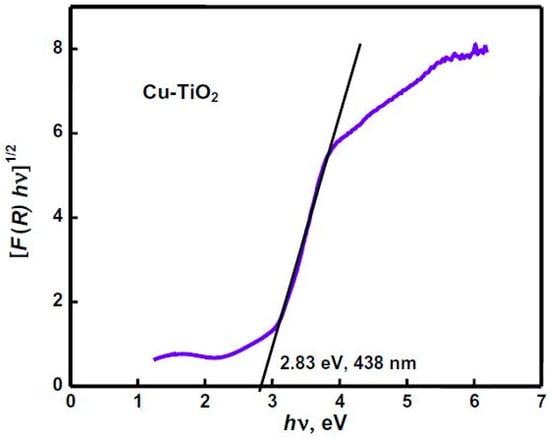

The energy gap of TiO2 and other semiconductors can be determined by analyzing the absorption or reflection percentage as a function of wavelength, using the Koblenz-Kommanek equation [153]:

α = F(R) = (1 − R)/2R

To convert wavelength (nm) to energy (eV), the below equation can be employed:

hʋ = 1240/λ

Here, α represents the absorption coefficient near the absorption edge, where the absorption decreases from its maximum value, R is the reflection rate from the sample surface, λ is the wavelength in nanometers (nm), and hʋ is the energy in electron volts (eV). These relations can be combined:

αhʋ = C1(hʋ − Eg)2

The band gap can be determined by drawing a tangent line to the graph of (F(R) hʋ)1/2 as a function of hʋ. The point where this tangent line intersects the horizontal axis, shows the band gap (Figure 15). Knowing the band gap of semiconductors allows one to identify the spectrum region in which the semiconductor can effectively absorb light. For TiO2, with a band gap of approximately 2.3–3 eV, this range falls within the ultraviolet spectrum. It is important to note that ultraviolet light constitutes only 4–5% of the solar spectrum. To enhance visible light absorption, one potential solution is to dope TiO2 with metallic or non-metallic elements as listed in Table 4. As indicated for comparison in Table 5, metallic elements can effectively reduce the energy gap. In addition, TiO2 can be modified with metal ions through various techniques, including ion implantation, sputtering, and chemical processes like sol–gel. The introduction of metal ions into the TiO2 structure leads to the formation of intermediate phases. Consequently, when light interacts with metal ion-modified TiO2, the surface electrons at these intermediate positions are excited. This excitation supplies the electrons with enough energy to absorb additional light and transfer electrons to the TiO2 surface. This process further enhances the generation of additional electrons upon light exposure, thereby facilitating redox reactions [154]. Common modifications involve transition metals, noble metals, non-metals, and rare earth elements (Table 4) [154,155].

Figure 15.

Cu-TiO2 band gap diagram [156].

Table 4.

Some doping elements in TNTs, their preparation methods, and their effects on the energy gap and photocatalytic activity of TNTs [59].

Table 5.

A comparison between band gap energy amount of the TiO2 doped with different elements.

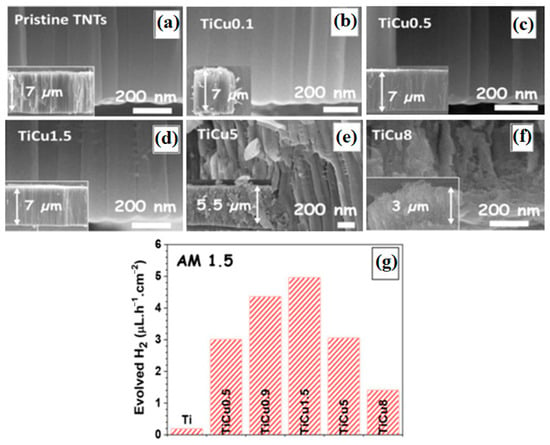

Doping TiO2 with transition and noble metals enhances charge carrier trapping, addressing challenges such as increasing the conductivity of TiO2 and improving the efficiency of water-splitting. For instance, using copper as a dopant allows Cu2+ to incorporate into the TiO2 lattice by substituting Ti4+, which boosts the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 [94]. The mechanism of H2 production in the presence of various copper species, including metallic copper and different oxidation states, has been comprehensively studied, revealing a beneficial impact [69,71,74]. Modifying TiO2 with noble and transition metals effectively creates visible light-active photocatalysts and reduces electron–hole pair recombination [165,166,167]. The first investigation into noble metal doping of TiO2 was conducted by Tauster et al. in 1978 [95]. Since then, numerous studies have been reported on the modification of TiO2 with nano-noble metals, including gold, silver, platinum, palladium, and other species [168,169], which serve as co-catalysts to facilitate electron transfer from the CB of TiO2 to the surrounding environment, thereby increasing the rate of H2 production [76]. The incorporation of noble metals onto the TiO2 surface enhances photocatalytic activity through the formation of a Schottky barrier at the titanium dioxide/metal junctions. In general, the Schottky barrier mechanism is used to better understand the role of the noble metal doped on TiO2. This barrier, established at the metal/titania interface, acts as an electron trap, delaying surface charge transfer and preventing the recombination of charge carriers during photocatalytic processes. The photocatalytic performance of titania with noble metals is significantly influenced by the quantum size effect of the noble metal [170]. Recent studies on titanium-copper binary alloys have demonstrated the potential to grow TiO2 nanotubes with intrinsic copper doping through electrochemical oxidation under controlled conditions. The results, shown in Figure 16, indicate that Ti-xCu alloys with a low concentration of copper (1.5 at. %) can produce TiO2 nanotubes decorated with copper nanoparticles. However, as the copper concentration in the alloy increases, the resulting nanotubes exhibit reduced order and size [74]. The findings indicate that higher copper concentrations hinder the growth of TiO2 nanotubes due to the formation of intermetallic phases. Additionally, the rate of hydrogen gas release from the produced nanotubes suggests that those decorated with copper nanoparticles can generate greater amounts of hydrogen (see Figure 16).

Figure 16.

SEM images of TiO2 nanotubes on various substrates: (a) pure Ti, (b) TiCu0.1, (c) TiCu0.5, (d) TiCu1.5, (e) TiCu5, (f) TiCu8, and (g) H2 production rates for different samples measured using a solar simulator at a power of 100 mW/cm2 [171].

In a separate study, titania doped with gold nanoparticles, each measuring 1.87 nm in diameter, demonstrated the highest photocatalytic activity for water splitting. Notably, noble metal nanoparticles can also enhance the absorption of visible light [100]. A selection of recent research in this area, primarily from the last decade and reflecting a growing trend, is summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of studies focused on reducing the energy band.

According to the above discussion, the overall goal is to prepare an effective TiO2-based semiconductor electrode for hydrogen gas production. All the measures taken are effective when they produce more hydrogen gas. Some of the studies conducted are given in Table 7 for comparison.

Table 7.

A summary of efficiency of TiO2-based materials for hydrogen production through water splitting.

11. Conclusions

Based on extensive previous research, studies have explored various types of photocatalysts and their applications across various fields. With the growing demand for renewable energies like hydrogen, and the need to utilize renewable resources such as water and sunlight for its production, both environmental and economic considerations are becoming increasingly important. Since water alone does not have the ability to absorb sunlight effectively for water splitting, employing photocatalyst materials is a promising solution to this challenge. Among the different types of photocatalysts, TiO2 has received the most research interest due to its strong photocatalytic activity, high chemical stability, and long lifespan of electron–hole pairs. Various synthesis methods for TiO2 have been introduced, with the anodic oxidation receiving particular attention for its advantages. This method is capable of producing TiO2 nanotubes with high specific surface areas and various dimensions (length and diameter). However, despite these benefits, the industrial application of TiO2 nanotubes faces several limitations, including requiring high overvoltage for hydrogen production, insufficient absorption of the visible spectrum of sunlight, and the recombination of electrons and holes during photocatalytic reactions. Researchers have proposed multiple strategies to overcome these challenges, including coupling TiO2 nanotubes with other semiconductors, controlling their size, polymerizing complexes, doping with noble metals, and engineering or modifying the surface of TiO2 nanotubes. Existing reports indicate that these approaches have effectively enhanced the photocatalytic efficiency of TiO2 nanotubes. In addition, future perspectives for TiO2 Nanotubes in Photocatalysis is important and includes:

- Extension of light-absorption into the visible and solar-spectrum range

While TiO2 nanotubes have excellent UV-driven photocatalytic properties, their wide band-gap (~3.2 eV for anatase) limits them to only ~4–5% of the solar spectrum. Future research should focus on band-gap engineering via doping (non-metal or metal), defect engineering (oxygen vacancies, Ti3+ states), sensitization with dyes or quantum dots, and coupling with narrow-band semiconductors to harvest visible light more effectively. For example, carbon-modified TiO2 nanotubes have shown enhanced H2 evolution under UV and extended response.

- 2.

- Improved charge carrier separation, transport and lifetime

A major challenge is the fast recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, which reduces quantum efficiency. To address this, strategies such as ordered nanotube arrays, hierarchical structuring, internal junctions, cocatalyst loading (noble-metals, metal oxides), and intimate heterojunctions are vital. For example, site-specific doping or embedding co-catalysts in nanotube walls can tailor transport of charges and spatial separation of reaction sites. Combining modeling (DFT, machine learning) and in situ characterization to understand carrier dynamics will further help optimize TNTs for hydrogen evolution and pollutant conversion.

- 3.

- Architectural and morphological optimization for high surface-area and accessibility

The anodic oxidation method that produces TNTs gives control over length, diameter, wall thickness and ordering, which influences surface area, light-absorption path length (via reflection within tubes), and mass transport. Future work should further refine hierarchical structures (e.g., branching nanotubes, spaced arrays) that combine rapid charge transport with large reactive interface and efficient photon capture. Some studies already show ordered spaced TNTs yield higher H2 generation.

- 4.

- Scalable, stable and cost-effective fabrication and integration into devices

While TNTs show promise in lab-scale tests, translation to large-scale, industrial systems for water splitting or pollutant treatment remains limited. Important future directions include:

- ○

- Developing low-cost, high-throughput anodization or alternative synthesis methods with uniform, reproducible tubes.

- ○

- Ensuring long-term stability under real sunlight, in real water or wastewater conditions (with fouling, ions, pH variation).

- ○

- Integrating TNTs into photoelectrochemical cells, solar reactors or membranes, with minimal auxiliary energy input.

- ○

- Designing systems that minimize noble-metal use, recovery or recycling of catalysts, and enabling modular deployment.

One review emphasizes that moving toward practical application requires combining theoretical understanding (charge-capture mechanisms) with experimental scale-up.

- 5.

- Multi-functional applications beyond hydrogen generation

Although hydrogen production via water-splitting remains a key target, TNTs can play roles in broader applications:

- ○

- Photocatalytic CO2 reduction to value-added fuels or chemicals via engineered TNT composites.

- ○

- Degradation of emerging contaminants (antibiotics, microplastics), disinfection, self-cleaning surfaces, and coupling photocatalysis with electrocatalysis. For example, TNTs have been applied in antibiotic-resistance-gene degradation in sludge.

- ○

- Coupled systems where solar energy is used simultaneously for pollutant removal and fuel generation, enhancing overall system economics and sustainability.

- 6.

- Mechanistic insight, modeling and smart material design.

Future progress will benefit from deeper mechanistic understanding of processes at the nanoscale: precise localization of reaction centers on the tubes, mapping the position of cocatalysts/dopants, understanding surface-adsorption/desorption kinetics, and reaction pathways for hydrogen, CO2 or pollutant conversion. As one recent review puts it: “future research should focus on theoretical (DFT, machine-learning predictions) and experimental studies based on the electron capture mechanism to achieve higher photocatalytic efficiency and extend the lifetime of photoexcited electrons and holes in TiO2.

- 7.

- Hybrid and tandem systems for full solar spectrum utilization