Abstract

In recent years, high-entropy materials (HEMs) have emerged as a promising multifunctional material system, garnering significant interest in the field of photocatalysis due to their tunable microstructures, diverse compositions, and unique electronic properties. Owing to their multi-element synergistic effects and abundant active sites, high-entropy photocatalysts enable precise regulation over the separation efficiency of photo-generated charge carriers and surface reaction pathways, thereby significantly enhancing photocatalytic activity and selectivity. The high configurational entropy of these materials also imparts exceptional structural stability, allowing the catalysts to maintain long-term durability under harsh conditions, such as intense light irradiation, extreme pH levels, or redox environments. This provides a potential alternative to common issues faced by traditional photocatalysts, such as rapid deactivation and short lifespans. This review highlights recent advancements in the preparations and applications of HEMs in various photocatalytic processes, including the degradation of organic pollutants, hydrogen production, CO2 reduction and methanation, H2O2 production, and N2 fixation. The emergence of high-entropy photocatalysts has paved the way for new opportunities in environmental remediation and energy conversion.

1. Introduction

As industrialization and urbanization accelerate worldwide, environmental pollution and energy shortage have become increasingly severe issues, particularly the management of toxic and hazardous pollutants in water bodies and the atmosphere, posing significant challenges [1,2,3]. Among various environmental remediation and energy conversion treatments, photocatalysis has garnered considerable attention due to its eco-friendly characteristics, low energy consumption, and broad applicability [4,5,6]. Such technology originated in 1972, when Fujishima and Honda first demonstrated that UV-illuminated TiO2 electrodes could split water without external bias [7]. The fundamental mechanism involves the generation of electron–hole pairs in semiconductors under light irradiation, which subsequently initiate redox reactions to break down pollutants or convert them into high-value-added products [8].

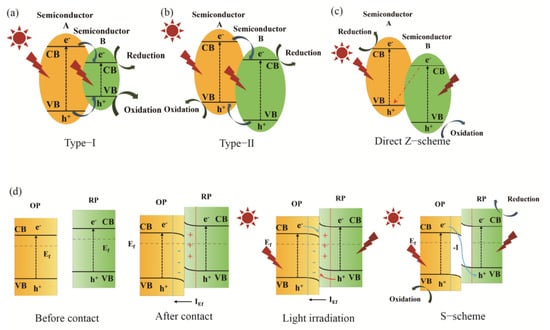

However, the practical efficiency of photocatalytic technology remains significantly constrained by a fundamental challenge: the rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers. During photocatalytic processes, the separation efficiency and migration pathways of photo-generated electrons and holes created when semiconductors absorb photons with energies exceeding their band gap serve as the primary driving force for redox reactions. These factors fundamentally determine the quantum efficiency of catalytic systems [9]. To address this issue, the construction of heterojunctions has emerged as a cornerstone strategy for optimizing charge separation behavior [10,11]. However, the quick recombination of charge carriers in single-phase semiconductors generally leads to low efficiency, making the establishment of heterojunctions essential for optimizing charge transfer pathways [12]. In a Type-I heterojunction, both the conduction band minimum (CB) and valence band maximum (VB) of semiconductor A are positioned at higher energy levels than those of semiconductor B [13]. Upon illumination, the produced electrons migrate from the CB of A to the lower-energy CB of B. Similarly, holes move from the VB of A to the VB of B. This results in the spatial confinement of both electrons and holes within semiconductor B, as shown in Figure 1a. Although this configuration facilitates charge separation, it coincidentally locates the sites for oxidation and reduction reactions in the same region, increasing the likelihood of charge recombination. Therefore, Type-I heterojunctions are primarily employed in optoelectronic devices such as photodetectors and light-emitting diodes, where focusing energy in a single material is beneficial. In a Type-II heterojunction, both the CB and VB potentials of semiconductor A are higher than those of semiconductor B, but band edges are staggered [14]. Driven by the built-in electric field, photogenerated electrons move from the higher-energy CB of A to the lower-energy CB of B, while holes migrate from the lower VB of B to the higher VB of A. This results in the accumulation of electrons on B and holes on A, facilitating efficient spatial separation of charge carriers, as shown in Figure 1b. This configuration effectively suppresses charge recombination and provides spatially distinct active sites for redox reactions. A notable drawback, however, is the consumption of a portion of the photogenerated potential (energy offset) during charge transfer, which consequently reduces the overall redox capability of the system. The Z-scheme heterojunctions were developed to overcome the reduced redox capability of Type-II systems while maintaining efficient charge separation and enhancing redox power [15]. Following this, the direct Z-Scheme heterojunction was proposed. This type of photocatalyst consists solely of two semiconductors in direct contact at the interface, eliminating the need for additional electron or hole mediators, as shown in Figure 1c. Compared to earlier Z-scheme systems, direct Z-scheme photocatalysts significantly reduce construction costs. Furthermore, this structure effectively eliminates the potential light-shielding effects associated with metal-based mediators, thereby enhancing light utilization efficiency [16]. As a result, the highly reductive electrons in A and the highly oxidative holes in B are preserved, enabling a charge transfer pathway that mimics the Z-shaped route of natural photosynthesis [17,18].

Figure 1.

Traditional generation and transfer of charge carriers in heterojunctions: (a) Type-I, (b) Type-II, (c) direct Z-scheme, (d) S-scheme.

The S-scheme heterojunction represents a recent conceptual advancement in refining the description of charge transfer in mediator-free heterojunctions [19]. It consists of a reduction-type semiconductor (RP, typically n-type) and an oxidation-type semiconductor (OP, typically p-type) in intimate contact. Fermi-level alignment at the interface results in the formation of a built-in electric field (IEf) that is directed from the OP to the RP, along with band bending. Under illumination, this IEf promotes the directed recombination and annihilation of electrons from the RP and holes from the OP at the interface [20]. Consequently, the remaining electrons in the CB of the RP and holes in the VB of the OP, respectively, participate in reduction and oxidation reactions, as shown in Figure 1d. The S-scheme not only achieves strong redox power but also ensures efficient charge separation, with its concept emphasizing a “stepwise” charge recombination mechanism at the interface [21]. Constructing efficient S-scheme heterojunctions requires specific criteria regarding the work function, band structure, and semiconductor type (n-type vs. p-type), which somewhat restricts the selection of compatible materials. The mechanism relies on the selective recombination of charge carriers at the interface, making it essential to precisely tune the interfacial properties. This tuning must facilitate the beneficial recombination (i.e., quenching useless carriers) without hindering the cross-interface transfer of desired carriers. Furthermore, elucidating the S-scheme mechanism necessitates correlative evidence from multiple experimental techniques to distinguish it from the conventional Type-II mechanism, thus demanding more sophisticated experimental design [22]. Despite significant advances, heterojunction systems still face inherent constraints in material compatibility, interface engineering, and complicated mechanisms, driving the need for new material paradigms. In this context, HEMs present a compelling candidate due to their unique multi-component nature and highly tailorable electronic structure. They have demonstrated remarkable potential across various fields, including energy conversion and environmental remediation. As an emerging class of photocatalysts, HEMs benefit from their unique “cocktail effect” and tunable electronic structures, which confer excellent compatibility with multiple components [23]. This characteristic makes them especially well-suited for constructing complex heterojunction systems. HEMs hold great promise for further development within the S-scheme framework, offering the potential to optimize interfacial charge transfer pathways through multi-component synergy. This could open new avenues for the design of next-generation high-efficiency photocatalysts. The introduction of HEMs is anticipated to overcome the limitations of material selection and interface control, advancing photocatalytic technology toward improved efficiency and stability.

A deeper understanding of the potential of HEMs in photocatalysis necessitates a clear grasp of their basic principles and unique characteristics. These materials consist of five or more primary elements in equimolar or near-equimolar ratios, and their high configurational entropy (ΔS ≥ 1.5 R) stabilizes the formation of distinctive solid-solution structures [24]. The four core effects of HEMs—the high-entropy effect, the lattice distortion effect, the sluggish diffusion effect, and the ‘cocktail effect’—endow them with numerous advantages, including broad-spectrum light absorption, efficient charge separation (with lattice distortion suppressing recombination), and exceptional stability (resistance to corrosion and oxidation). In photocatalysis, HEMs have been successfully applied in the degradation of organic pollutants [25], H2 generation [26], and CO2 reduction [27]. Notably, incorporating rare-earth elements or constructing heterojunctions can further optimize their photocatalytic performance [28]. However, despite these advantages, the large-scale application of HEMs in photocatalysis faces several critical challenges. On one hand, due to their multi-component nature and high melting points, current synthetic methods are often costly and involve complex processes, making it difficult to achieve precise control over morphology and composition, which hinders scalable production [29]. On the other hand, the intricate composition and microstructure of HEMs complicate the understanding of the structure-activity relationships, particularly in identifying active sites, modulating electron structure, and elucidating the principles of multi-site synergy [30]. Therefore, systematically summarizing the design strategies, performance advantages, and mechanisms of HEMs in photocatalysis holds significant scientific and engineering value for advancing the field from laboratory research to practical applications.

This paper aims to review the research advancements of the past three years, analyze the current key scientific challenges, and propose the future directions for the development of high-performance HEM-based photocatalytic materials.

2. High-Entropy Materials

2.1. Concept

A fundamental understanding of entropy in HEMs requires a clear conceptualization of mixing entropy in multicomponent systems. From a thermodynamic viewpoint, entropy serves as a crucial state function that quantifies the degree of disorder in the arrangement of microscopic particles. Higher entropy values correspond to greater randomness and configurational disorder within the system [31]:

where k is the Boltzmann constant (1.38 × 10−23 J/K), and ω represents the thermodynamic probability, defined as the total number of accessible microstates in the system. In an alloy system with n constituent elements, the total mixing entropy is influenced by multiple factors, with the configurational entropy (∆Sconf) being the dominant contribution. The configurational entropy of such a system can be calculated using the following expression [31]:

where R is the universal gas constant, and ci represents the molar concentration of component i in the alloy, with 0 < ci < 0.35 for typical HEMs. Based on their configurational entropy (∆Sconf) values, alloys can be classified into three categories: systems with no more than two principal elements are considered low-entropy alloys (∆Sconf ≤ 0.69R); alloys with 3–4 principal elements fall into the medium-entropy alloy category (0.69R < ∆Sconf < 1.61R); alloys with five or more elements, and the configurational entropy exceeding 1.61R, belong to HEMs [32].

HEMs represent a novel class of metallic materials consisting of at least five principal elements, with each element contributing an atomic percentage between 5% and 35%. In these alloys, the conventional distinction between solvent and solute elements becomes irrelevant [33]. The most distinctive feature of HEMs is their exceptionally high mixing entropy, where multiple principal elements adopt disordered atomic arrangements, resulting in structurally simple solid solution phases.

From a thermodynamic perspective, entropy is a critical parameter for quantifying the degree of disorder within a system [34]. In solid solutions, the random distribution of different atomic species across lattice sites significantly enhances the system’s total entropy, a phenomenon known as the mixing entropy effect. For alloys containing multiple principal elements, the entropy calculation primarily focuses on the configurational entropy arising from atomic arrangements. Research has demonstrated that the mixing entropy increases markedly as the number of constituent elements grows.

This high mixing entropy characteristic of HEMs thermodynamically favors the formation of simple solid solution structures rather than complex intermetallic compounds. Notably, when the configurational entropy exceeds 1.5R, this high-entropy effect becomes particularly pronounced, serving as one of the fundamental distinctions between HEMs and conventional alloys. The enhanced entropy stabilization effect significantly suppresses the formation of intermetallic phases, even in systems with a positive enthalpy of mixing, thus enabling the formation of single-phase solid solutions [35], which would be unattainable in traditional alloy systems.

HEMs encompass a broad category of multicomponent systems, typically characterized by the near-equimolar incorporation of multiple principal elements. In refining their definition, the classical concept developed for high-entropy alloys (HEAs) can be extended to compound systems. Similar to factoring out a common term in algebra, the relatively fixed and non-interchangeable nonmetallic elements (such as the anionic frameworks of O, S, P, etc.) can be treated as constant components within the material’s structure. Therefore, the classification of high-entropy compounds is determined by the types and amounts of metal cations that can be equivalently substituted. Accordingly, HEMs can be categorized based on their chemical composition and structural characteristics into several groups, including HEAs, high-entropy oxides (HEOs), high-entropy sulfides (HESs), high-entropy phosphides (inorganic compounds consisting of five or more metal cations uniformly distributed within a phosphorus-based anionic framework), high-entropy selenides, high-entropy hydroxides, high-entropy oxynitrides, bismuth-based high-entropy materials, high-entropy metal–organic frameworks, and lithium niobate high-entropy variants, among others. Notably, within each category of high-entropy compounds, these “common factor” nonmetallic elements typically maintain a fixed stoichiometric ratio. To date, HEOs, HEAs, and HESs have garnered the most extensive research interest and have shown significant potential for practical applications.

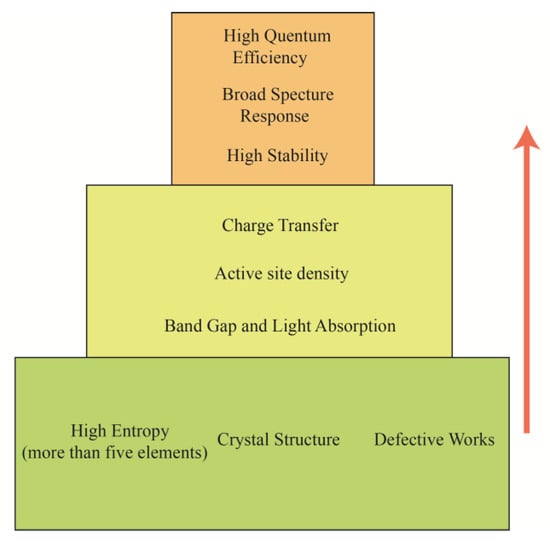

The exceptional photocatalytic performance of HEMs stems from two synergistic effects linked to their multi-principal-element nature: continuously tunable band structures and stable defect engineering, as shown in Figure 2. First, at the electronic structure level, the diverse d- or p-orbitals of different metal ions undergo continuous hybridization within the shared lattice, resulting in broadened and continuous energy bands. This unique electronic configuration allows researchers to precisely tune the positions of the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum—much like “tailoring” a garment—by adjusting the types and ratios of constituent elements, thereby customizing the optical absorption edge. Concurrently, the intrinsic absorption edges of different elements are integrated into a single material, significantly broadening the light-response range and enhancing the efficient utilization of the solar spectrum. Second, at the atomic structure level, differences in atomic radii and electronegativities induce substantial local lattice distortion, disrupting the perfect crystallographic periodicity and creating internal potential fluctuations. This not only effectively suppresses bulk recombination of photogenerated carriers but also creates favorable conditions for introducing high-density, stable defects. These defects serve as efficient charge-trapping centers and catalytically active sites, optimizing the adsorption and activation of reactants. Crucially, the inherent “sluggish diffusion effect” in high-entropy systems impedes the migration and annihilation of these defects, thereby ensuring structural stability and sustained catalytic activity during prolonged reactions.

Figure 2.

Multidimensional design space and performance targets of HEM photocatalysts.

2.2. Configuration Entropy

The progression of material systems has advanced from simple single-element and binary alloys to the groundbreaking concept of HEAs. Early materials, such as copper, iron, and bronze, were characterized by low-entropy compositions and well-defined structures. However, their properties were inherently limited due to the constrained combinations of elements.

With advancements in metallurgical techniques, the materials science community began exploring more intricate ternary and multicomponent alloys [36]. Alloys such as stainless steel and aluminum alloys showcased how introducing additional principal elements, coupled with precise microstructural control, could improve mechanical strength, enhance corrosion resistance, and optimize lightweight properties. These medium-entropy systems marked an important transition in alloy design philosophy.

The true breakthrough came with the advent of HEAs, which revolutionized traditional materials engineering approaches [29]. This innovative design strategy enables the creation of exceptional combinations of properties that are rarely seen in conventional alloys, such as a simultaneous balance of high strength and toughness, remarkable stability under extreme conditions, and unique functional characteristics. The emergence of high-entropy alloys has not only expanded the boundaries of metallic materials but has also paved the way for entirely new categories of high-entropy ceramics, semiconductors, and hybrid systems, reshaping the landscape of modern materials science [37].

2.3. Four Core Effects

2.3.1. High Entropy Effect

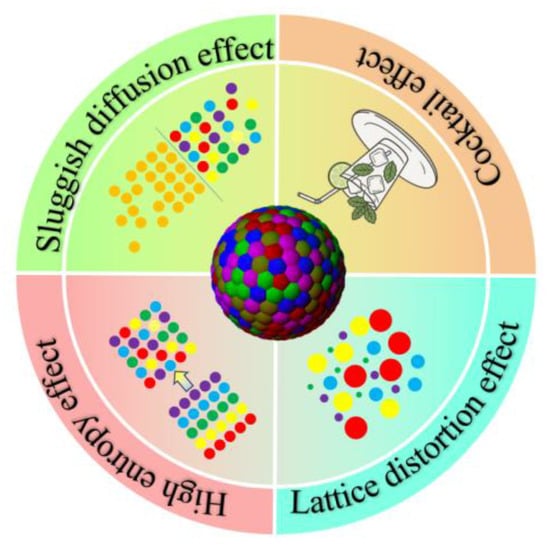

HEM systems can typically form solid solution phases, intermetallic compounds, amorphous phases, or hybrid microstructures [32,33,38]. What sets these alloys apart from conventional ones is their dramatically enhanced mixing entropy, which allows entropy effects to predominantly govern the phase formation processes, as depicted in Figure 3. According to traditional physical metallurgy principles and binary/ternary phase diagrams, such multi-principal-element systems are expected to form numerous complex phases and intermetallic compounds, making microstructure analysis and design particularly challenging. However, experimental observations reveal that HEMs tend to preferentially form relatively simple solid solution phases [39].

Figure 3.

Four core effects of HEMs.

This unexpected behavior primarily originates from the substantial reduction in Gibbs free energy due to high configurational entropy, which effectively suppresses the formation of intermetallic compounds. Research has demonstrated that when the configurational entropy exceeds 1.5R, the high-entropy effect drives the system toward single-phase solid solution structures [40]. This can be explained by the following equation:

where T represents the absolute temperature, ∆Hmix denotes the mixing enthalpy, and ∆Smix corresponds to the mixing entropy. In the case of HEMs, the dramatically enhanced mixing entropy causes the entropic contribution (T∆Smix) to dominate over enthalpic effects (∆Hmix) in determining the total free energy of the system. This entropy-driven mechanism produces two critical effects: a substantial reduction in the overall free energy of the system and an increase in the mutual solubility of the constituent elements. The resulting thermodynamic stabilization favors the formation of structurally simple solid solution phases rather than complex intermetallic compounds. This fundamental characteristic offers distinct advantages for alloy design and practical applications, including simplified phase prediction and control, reduced sensitivity to compositional fluctuations, and enhanced microstructure stability at elevated temperatures. Particularly noteworthy is that when ∆Smix exceeds 1.5R, the entropy effect is strong enough to stabilize single-phase solid solutions, even in systems with positive ∆Hmix values [41,42,43].

2.3.2. Sluggish Diffusion Effect

The multi-principal-element nature of HEMs induces significant lattice distortion effects due to the random occupation of crystallographic sites by dissimilar atoms [44,45,46]. A study by Pramote et al. on TiNbHfTaZr HEMs provided direct experimental evidence of the correlation between lattice distortion and atomic-size mismatch [47]. Their work systematically demonstrated that the extent of lattice distortion is linearly with the atomic size disparity parameter. The distortion mechanism operated through the generation of localized strain fields, and the resulting heterogeneous strain distribution affected mechanical behavior through pinning dislocations, modifying slip systems, and enhancing work hardening. Yeh et al. investigated CuNiAlCoCrFeSi HEMs and revealed that lattice distortion could be distinctly observed in X-ray diffraction patterns through two key effects: (1) significant peak broadening and (2) reduced diffraction intensity, both resulting from the increased X-ray diffuse scattering [44]. These experimental observations were directly correlated with the underlying atomic-scale disorder of the alloy, where the random occupation of lattice sites by dissimilar atoms generated localized strain fields that altered the energy landscape for dislocation motion.

2.3.3. Lattice Distortion Effect

The lattice distortion effect in high-entropy materials is manifested by significantly lower diffusion rates of each component atom in multi-principal-element systems compared to conventional single-principal-element alloys [48]. This effect originates from the complex local atomic environment: the random occupation of lattice positions by multiple principal elements means that diffusing atoms constantly encounter changing neighboring atomic configurations during migration. The variation in bonding strength between different atoms creates energy fluctuations within the potential field distribution of each lattice site [49]. As a result, atoms moving to lower-energy lattice sites become captured and stabilized, whereas those encountering higher-energy sites tend to revert to their original positions. These local energy fluctuations significantly raise the energy barrier for effective diffusion, thereby reducing the net mobility of atoms. Research has confirmed that the extent of diffusion delay is closely related to parameters such as atomic size differences and mixing enthalpy, which directly influence the high-temperature microstructure stability and precipitation kinetics of the alloy. In high-entropy materials systems like CoCrFeMnNi, this effect can reduce the diffusion coefficient of elements by 1–2 orders of magnitude [48]. Dabowa et al. found through tracer diffusion experiments that the delayed diffusion effect not only occurred in CoCrFeMnNi HEMs, but also in binary alloy systems with high Mn content [50,51]. This indicates that the presence of the Mn element may be the main cause of diffusion hysteresis, rather than an inherent, universal characteristic of HEMs themselves.

2.3.4. Cocktail Effect

Ranganathan introduced the “cocktail effect” to describe the unique synergistic interactions among multiple components in HEMs [52]. In alloy systems with five or more equimolar (or near-equimolar) elements, the resulting properties are not merely linear combinations of the individual components’ characteristics. Instead, they arise from complex interatomic interactions that produce synergistic effects beyond what would be predicted by linear summations. Specifically, this effect is manifested in three aspects: (1) the deliberate addition of specific elements can modify alloy properties, such as Al reducing density, while Cr or Si enhance high-temperature oxidation resistance; (2) precise control over component types and concentrations can induce the formation of protective surface oxide layers; (3) this multicomponent synergy significantly improves the alloy’s resistance to hot corrosion. Experimental evidence demonstrates that effectively harnessing this effect can achieve performance levels that traditional alloys cannot match, providing crucial pathways for developing novel high-performance materials. For instance, adding aluminum, an element with a relatively low melting point and hardness, to CoCrCuFeNi HEMs significantly increases the overall hardness. This phenomenon stems from the strong chemical bonding interactions between Al and other elements (such as Co, Cr), which induce phase structure transformation in the alloy [53]. As the Al content increases, the alloy’s phase structure undergoes the following sequential evolution: (1) an initial single-phase face-centered cubic (FCC) structure; (2) a transition to a dual-phase FCC+ body-centered cubic (BCC) structure; and (3) when the Al content exceeds a critical threshold, the alloy ultimately forms a single BCC or B2 ordered structure [54].

2.4. HEMs Synthesis for Photocatalysis

The thermodynamic formation mechanism of HEMs can be elucidated using the Gibbs free energy equation:

where the mixing enthalpy (∆Hmix) and mixing entropy (∆Smix) collectively determine the phase stability of the material system. When the system possesses sufficiently high mixing entropy, typically contributed by five or more principal elements, the entropy effect can counterbalance the unfavorable enthalpy changes between elements, thereby promoting the formation of single-phase solid solutions [55]. However, due to the vast differences in the physical and chemical properties of the constituent elements, which result in a wide range of ∆Hmix values, the spontaneous formation of single-phase HEMs is inherently challenging. Consequently, the successful synthesis of HEMs requires a delicate balance between thermodynamic constraints and kinetic facilitation [56]. This balance is achieved by selecting appropriate synthesis methods, such as rapid solidification, mechanical alloying, or physical vapor deposition, along with precise control over processing parameters to promote homogeneous mixing and suppress phase separation, thus enabling the formation of single-phase HEMs.

The synthetic methods for HEMs vary significantly depending on their constituent elements. When focusing on nanomaterial fabrication, the selection of the synthetic route is primarily governed by the chemical characteristics of the elements involved [57]. In this section, the main synthetic methods for HEMs will be discussed and categorized into two steps: mechanical method and heating method. By combining and arranging these two steps, almost all synthesis schemes are covered.

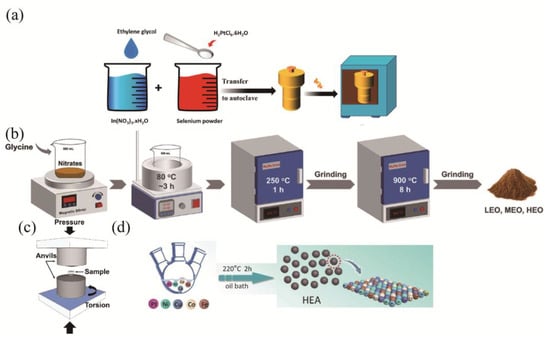

2.4.1. Mechanical Procedure

Mechanical processing techniques are generally divided into two main methodologies in Figure 4c: ball milling and high-pressure torsion (HPT). Ball milling operates through cyclic high-energy impacts, which induce repeated cold welding and fracturing of powder particles, facilitating atomic-scale mixing and nanostructure formation [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. The process involves three concurrent mechanisms: (i) progressive refinement of particles to nanoscale dimensions through plastic deformation and fracture, (ii) a crystalline-to-amorphous transformation induced by accumulated lattice strain, and (iii) solid-state diffusion that enables the homogenization of immiscible elements. This technique proves particularly effective for synthesizing HEMs by overcoming positive mixing enthalpies and forming metastable solid solutions beyond equilibrium solubility limits.

HPT employs simultaneous gigapascal-range hydrostatic pressure and torsional shear strain to induce extreme plastic deformation in bulky materials [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. This process generates unique microstructural features, including (i) grain refinement to nanocrystalline scales, (ii) the formation of high-angle grain boundaries with non-equilibrium configurations, and (iii) the introduction of controlled defect densities surpassing those achieved by conventional processing methods. When applied to high-entropy systems, HPT demonstrates remarkable capability in achieving complete elemental homogenization while creating stabilized nanostructures unattainable through thermal processing alone [72]. Both techniques leverage severe mechanical deformation to access non-equilibrium material states, though they differ fundamentally in their product forms (powders versus bulk solids) and specific microstructural outcomes, offering complementary approaches for advanced material synthesis [73].

Furthermore, microwave and ultrasonic methods can also be considered as mechanical procedures. However, there have been no recent reports on the synthesis of photocatalysts using these techniques. Therefore, we believe these methods hold potential for future applications in photocatalyst synthesis.

2.4.2. Heating Processes

Thermal processes utilize external thermal energy to activate atoms, providing them with sufficient kinetic energy for diffusion, which facilitates mixing and alloying. Among the most widely established methods are arc melting and induction melting, which involve completely melting the constituent metals at high temperatures, followed by cooling them to form ingots. While these techniques are straightforward and effective, they suffer from relatively slow cooling rates, which can lead to elemental segregation due to differences in density and melting points [81]. To address this issue, atomization techniques have been developed. These methods disintegrate a stream of molten metal into fine droplets that rapidly solidify, yielding spherical powders with a homogeneous composition. These powders serve as the basis for powder metallurgy and are also critical feedstock for additive manufacturing. For solid-state densification, sintering techniques such as spark plasma sintering and hot isostatic pressing are prominent. They consolidate powder compacts into dense bulk materials through a combination of heat and pressure. Flash sintering, an extreme form of rapid sintering, uses an intense electric field to achieve densification in milliseconds. The exceptionally high heating and cooling rates in flash sintering effectively suppress segregation and grain growth, resulting in unique nanostructures [82].

Figure 4.

Synthetic diagrams of HEMs: (a) Hydrothermal calcination method [83]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. (b) Wolution combustion method [84]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (c) High-pressure torsion method [85]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. (d) Oil bath method [86]. Copyright 2023, CCC.

High-entropy materials can also be fabricated in the solution phase via heating. The hydrothermal method in Figure 4a employs high-temperature and high-pressure aqueous environments and is particularly suitable for producing oxide nanomaterials. Solution combustion synthesis in Figure 4b is a more vigorous process that relies on self-sustaining redox reactions between metal nitrates and organic fuels in a solution. This approach facilitates molecular-level mixing and rapidly produces nanoporous powders within seconds. In contrast, the oil bath method in Figure 4d offers a gentler and more controlled approach by providing a uniform, low-temperature heating environment via a hot oil medium, making it ideal for synthesizing nanomaterial precursors. Beyond conventional heating, specialized energy fields have also emerged. Microwave sintering takes advantage of the dielectric loss of materials to achieve volumetric heating from within, offering high efficiency and reduced thermal gradients. Laser-based methods represent the pinnacle of energy density. Techniques such as selective laser melting (SLM) or laser cladding use a laser beam that acts as a mobile heat source to create a localized melt pool, which then solidifies at an extremely high cooling rate. This approach not only enables the fabrication of complex geometries but can also generate ultra-fine-grained or even amorphous structures, showcasing the capacities of digital manufacturing.

3. Applications of HEMs in Photocatalysis

3.1. Carbon Dioxide Reduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction technology offers a range of environmental benefits, primarily manifesting through direct greenhouse gas mitigation, enhanced air pollution control, ecological restoration, the development of sustainable materials, and the promotion of a circular economy [87,88,89]. Catalytic conversion processes transform CO2 emitted from industrial sources into valuable fuels and chemicals, achieving two key objectives: reducing atmospheric carbon concentrations and replacing carbon-intensive industrial processes. This technology also enables integrated treatment of industrial exhaust streams, simultaneously degrading organic pollutants while reducing CO2 emissions.

In terms of ecological remediation, CO2 reduction helps alleviate ocean acidification and transforms waste streams into valuable resources. Additionally, environmentally benign materials synthesized from CO2 significantly reduce petroleum consumption, exhibiting superior ecological profiles compared to conventional petrochemical products. The technology also plays a pivotal role in carbon trading markets and supports the development of closed-loop carbon-neutral systems.

In recent years, a series of studies have significantly enhanced the photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of HEMs through ingenious material design, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the up-to-date HEM photocatalysts for CO2 reduction.

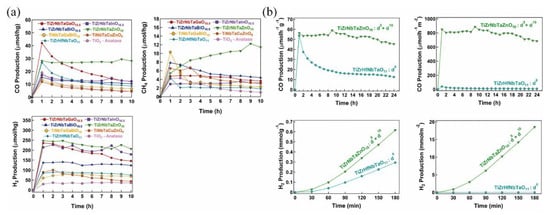

First of all, the essence of modulating composition and electronic structure lies in leveraging effects inherent in high-entropy systems. This is exemplified in a study by Hidalgo-Jiménez’s group [92], where precise tuning of the zinc content was shown to effectively optimize the electronic structure of a high-entropy oxide, leading to a notable enhancement in methane selectivity in Figure 5a. In addition, the introduction of Zn2+ ions with a d10 electronic configuration in Figure 5b, which formed a mixed coordination structure with cations possessing a d0 configuration, effectively enhanced the light absorption and inhibited the recombination of charge carriers [80]. This synergistic modulation ultimately boosted both hydrogen evolution and CO2 reduction capacities.

Figure 5.

(a) Increasing the methanation tendency in high-entropy oxides with a hybrid d0 + d10 orbital configuration for photocatalytic applications [92]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. (b) Enhanced photocatalytic CH4, CO, and H2 production on high-entropy oxide TiZrNbTaZnO10 compared to binary oxides mixed by HPT [80]. Copyright 2024, CC.

Secondly, constructing efficient heterojunction interfaces is paramount, as heterojunction engineering plays a key role in promoting the spatial separation of photo-generated charge carriers. Hasanvandian et al. demonstrated this by compositing high-entropy sulfide nanoparticles with ultrathin g-C3N4, where spatial charge separation at the interface enabled highly efficient solar-driven CO2 reduction, leading to a notably high syngas production rate [90]. Zhang et al. further revealed that the introduction of metal co-catalysts (e.g., Cu) is critical for optimizing heterojunction quality. Their innovative “direct introduction” method resulted in a more uniform distribution of nanoparticles and more intimate interfacial contact, significantly enhancing both CH4 selectivity and production rate [95]. Additionally, direct evidence of an S-scheme charge transfer pathway within an IES/ZIS composite system was provided [94]. This mechanism effectively preserves strong redox potentials while enabling highly efficient charge separation.

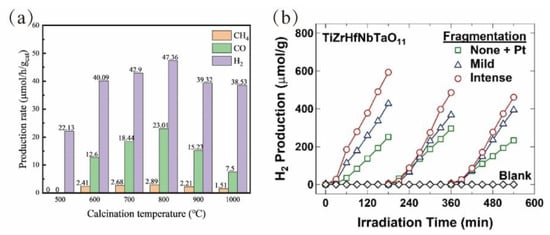

Third, optimizing synthesis and post-processing protocols is essential, as these approaches directly govern the final microstructure and properties of the resulting materials. Jiang et al. demonstrated this by synthesizing high-entropy oxides with enhanced activity and stability through precise control of the calcination temperature [91], as shown in Figure 6a. Furthermore, Pourmand Tehrani et al. reported that laser fragmentation, a novel post-processing technique, effectively reduced particle size and enhanced the light absorption capacity of high-entropy oxides [85], as depicted in Figure 6b. These optimizations resulted in excellent CO2 reduction performance without relying on noble metal co-catalysts.

Figure 6.

(a) Photocatalytic activities of samples calcined at different temperatures for CO2 reduction with water vapor and stability [91]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (b) H2 production from photocatalytic water splitting for three cycles versus irradiation time using high-entropy oxide TiZrHfNbTaO11 before and after fragmentation by laser treatment under mild and intense conditions [85]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier.

In addition, a statistical analysis of the literature from the past three years in Table 1 reveals that research on high-entropy materials for CO2 reduction is currently dominated by HEOs (with five reported cases), while HESs (three cases) and HEAs (one case) are comparatively less explored. In terms of reported performance metrics, HEOs clearly demonstrate significant advantages. However, a noteworthy trend emerging from the limited studies of HEAs is their unique potential to achieve CO2 reduction under solar-driven conditions. Unlike other systems, which typically require an external power source and currently dominate high-entropy oxide research, this solar-driven approach holds considerable appeal due to its potential to reduce energy consumption, simplify system architecture, and improve overall economic feasibility. Consequently, although HEOs currently exhibit superior performance, we argue that from a long-term, application-oriented perspective, the development of efficient photocatalytic systems based on high-entropy alloys represents a more sustainable and economically promising research direction.

3.2. H2 Evolution

The development of highly efficient hydrogen evolution technologies is of strategic significance for achieving a clean energy transition [97,98,99]. Hydrogen, with its high energy density and zero-carbon emissions (water being the sole combustion product), represents an ideal energy carrier and offers a sustainable solution to both the fossil fuel crisis and the urgent need for carbon emission reduction [100]. The photocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction has emerged as one of the most promising methods for green hydrogen production, directly utilizing solar energy to split water molecules. HEMs have introduced a groundbreaking advancement in photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, supplying unique advantages that overcome the limitations of conventional photocatalysts. It is evident that HEMs have demonstrated substantial progress within the domain of photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the up-to-date HEM photocatalysts for H2 evolution.

Table 2 reveals that HEAs occupy a notable proportion of the reported studies. However, a key characteristic is that the vast majority of these studies focus on HEAs in composite materials. This is primarily because, in typical hydrogen production systems, the bandgap structure of HEAs alone is often insufficient for efficient light absorption and charge excitation independently. Their main advantage lies in their role as excellent cocatalysts when coupled with suitable semiconductors. In this configuration, HEAs effectively separate and transfer photogenerated electrons through the formation of Schottky junctions, significantly lowering the overpotential for proton reduction. In contrast, HESs and HEOs are more frequently designed as the primary light-absorbing materials. To further enhance their hydrogen evolution performance, future research may focus on several improvement strategies. For high-entropy sulfides, the emphasis should be on adjusting their elemental composition to optimize the bandgap, improve their spectral response alignment with the solar spectrum, and enhance their photochemical stability in aqueous environments. For HEOs, efforts should focus on enhancing their relatively low conduction band position and charge carrier mobility to enhance reducibility and reaction kinetics, possibly through doping or heterojunction engineering.

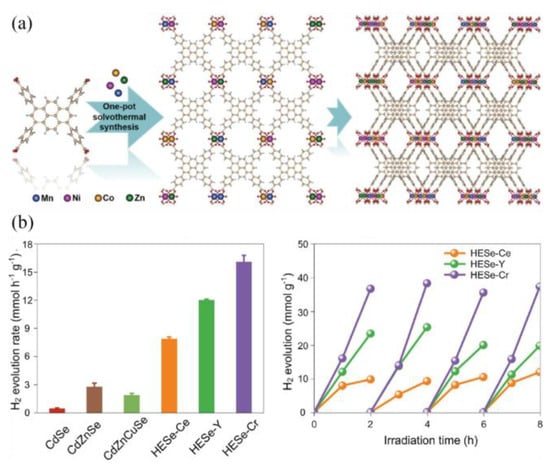

The high-entropy strategy offers an effective pathway for optimizing the intrinsic activity of emerging catalytic materials. Qi et al. reported the first synthesis of a p-type high-entropy metal–organic framework in Figure 7a, demonstrating that its nanosheet derivative achieved a visible-light-driven hydrogen evolution rate of 132.4 μmol·h−1. This performance was 48 times higher than that of its bulky single-crystal counterpart, a significant enhancement attributed to the reduced dimensionality, which facilitated charge migration and exposed a greater number of active sites [101]. In a separate study, Wang et al. synthesized two-dimensional high-entropy selenides using a facile microwave-assisted hydrothermal method [102]. The optimal composition, Cd0.9Zn1.2Mn0.4Cu1.8Cr1.2Se4.5, exhibited an exceptionally high hydrogen evolution rate of 16.08 mmol·h−1·g−1 in Figure 7b. Theoretical calculations indicated that the multiple principal elements acted synergistically to modulate the electronic density of the Cd active sites, thereby optimizing the adsorption of intermediates.

Figure 7.

(a) Synthesis and schematic structures of the HE-MOF-SC [101]. Copyright 2024, Wiley. (b) Comparison of photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of Se-based catalysts and recycling photocatalytic performance of HESe-Ce, HESe-Y, and HESe-Cr [102]. Copyright 2024, ACS.

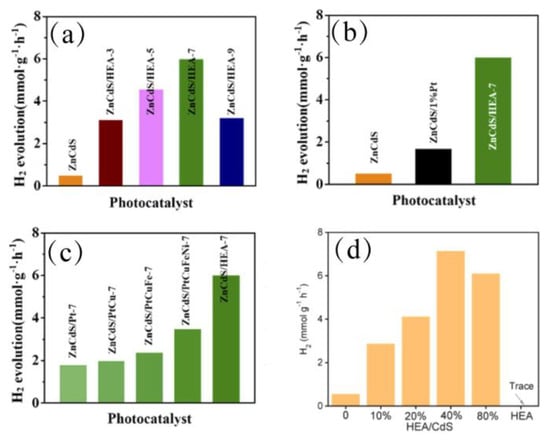

Using HEMs as co-catalysts or for constructing heterojunctions represents an effective strategy for enhancing the capability of conventional catalysts. TiO2-supported Pd@high-entropy alloy core–shell nanocrystals were prepared by Lin et al. [103]. The higher work function of the HEA shell optimized the Schottky junction, resulting in an extended charge carrier’s lifetime of 4 milliseconds, far surpassing that of pure TiO2. Guided by theoretical screening of d-band center and hydrogen adsorption free energy, Wang et al. constructed a ZnCdS/PtFeCuCoNi HEA composite, which exhibited an 11.7-fold enhancement in hydrogen evolution rate in Figure 8a–c, highlighting the advantage of HEAs in providing active sites and optimizing reaction kinetics [106]. Furthermore, Xiang et al. realized the synergistic coupling of hydrogen evolution with the selective oxidation of cinnamyl alcohol using an HEA/CdS heterojunction in Figure 8d, illustrating the potential of HEMs in multi-reaction coupling systems [107].

Figure 8.

(a–c) Photocatalytic H2 evolution performance of relevant samples [106]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. (d) The H2-production rate of x%HEA/CdS (x = 0, 10, 20, 40, 80) and HEA [107]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier.

The diverse functionality of HEOs has made them a prominent focus of research. Chang et al. introduced ferroelectricity into an HEO, revealing that its piezo-polarization and oxygen vacancy concentration could synergistically modulate the depletion region width, thereby promoting the separation of charge carriers. As a result, the hydrogen production yield for the polarized sample was 163% higher than that of its non-polarized counterpart [104]. In another separate study, Güler et al. developed a novel mesoporous HEO (TiZrNdHfTaOx) that enabled stable hydrogen production without the need for noble metal co-catalysts, offering a promising pathway for designing low-cost photocatalytic systems [109].

The high-entropy concept is continuously being extended to novel material systems. Guo et al. made a significant contribution by introducing high-entropy metal phosphides into photocatalysis for the first time. By constructing a direct Z-scheme heterojunction with ZnIn2S4, they achieved a hydrogen evolution rate of 4630.21 μmol·h−1·g−1, pioneering the exploration of high-entropy metal phosphides in the photocatalytic domain [108].

In summary, HEMs, benefiting from the “cocktail effect” arising from their multi-component nature, provide diverse and innovative strategies for photocatalytic hydrogen production. These strategies span from tuning intrinsic activity and engineering interfaces to exploring entirely new material systems. Future research should focus on uncovering the synergistic mechanisms at multi-element active centers and developing more cost-effective and environmentally friendly, scalable synthetic methods to accelerate their practical applications.

3.3. Organic Contaminants Degradation

Photocatalytic degradation technology is undergoing transformative breakthroughs, with its forthcoming development poised to fundamentally reshape environmental governance frameworks [110,111,112]. In recent years, extensive investigations have been conducted on persistent organic pollutants within aquatic environments, particularly focusing on the bio-refractory contaminants that are resistant to conventional treatment methods, which are summarized in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Summary of the up-to-date HEM photocatalysts for organic contaminants degradation.

Table 3 indicates that HEOs dominate current studies, while composite systems based on HEAs remain relatively scarce. Several factors may explain this distribution. First, strong oxidative capability is crucial for pollutant degradation, particularly in photocatalytic oxidation processes. HEOs typically have more positive valence band positions and can form highly oxidative holes (h+) or ·OH radicals, giving them an inherent advantage in breaking down organic pollutants. Second, HEOs may inherently exhibit Fenton-like activity, allowing them to combine photocatalysis with chemical oxidation, thereby further enhancing degradation efficiency. In contrast, HEOs are primarily reduction-oriented catalysts. When combined with semiconductors, their main role is to serve as electron acceptors that facilitate charge separation—a function that contributes indirectly to hole-driven oxidation reactions. Consequently, researchers may prefer HEOs for their more well-defined and effective oxidative properties.

Among the various emerging materials, HEAs stand out for their remarkable potential in addressing these critical environmental challenges. HEAs have demonstrated exceptional effectiveness in photocatalytic degradation. For instance, the nanostructured FeCrCoZrLa HEA achieved a degradation efficiency of approximately 89.76% for methylene blue [119]. Zhang et al. developed an amorphous HEA ribbon ((Fe0.5Co0.5)70B21Ta4Ti5) that completely decolorized Eosin Y within 29 min, a performance attributed to its unique surface self-renewal mechanism [124]. Furthermore, HEA nanoparticles MnFeCoNiCu synthesized by Das et al. efficiently degraded various antibiotics (e.g., ~95% for sulfamethoxazole) under visible light, with the added benefits of easy recovery and no secondary pollution, underscoring their potential for practical applications [65].

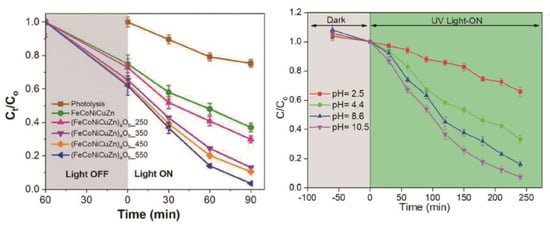

Beyond alloy systems, their oxide counterparts, HEOs, also demonstrate equally impressive performance in the degradation of organic pollutants. For instance, Das et al. synthesized (FeCoNiCuZn)aOb HEO nanoparticles that achieved a degradation efficiency of up to 97% for sulfamethoxazole in Figure 9a, surpassing the performance of their corresponding HEAs. This superior activity is attributed to the activation of lattice oxygen by multivalent metal cations [116]. In another study, Anandkumar et al. reported that (CeGdHfPrY)O2 nanoparticles exhibited outstanding degradation efficiency for methylene blue under optimized conditions in Figure 9b, emphasizing the critical importance of reaction parameters, such as pH values and catalyst loading, in fully realizing the potential of HEOs [118].

Figure 9.

(a) Visible light-induced photocatalytic degradation of sulfamethoxazole [116]. Copyright 2024, RSC; (b) Effect of pH values on the photocatalytic reactions [118]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier.

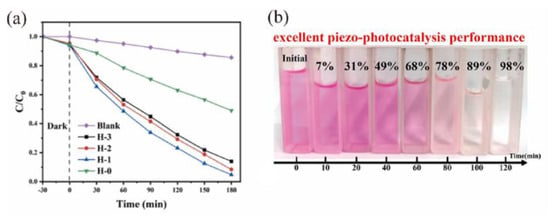

Achieving such exceptional properties necessitates precise control over the material’s composition to enhance photocatalytic performance under the tested conditions. The study by Jia et al. systematically explored the regulatory effect of Fe content on the crystal structure, band structure, and defect states of (La0.2Ce0.2Gd0.2Zr0.2Fex)O2−δ HEOs. The candidate with a moderate Fe content (x = 0.05) exhibited the optimal performance in tetracycline degradation (95.4%) in Figure 10a, underscoring the importance of a synergistic combination of moderate defect states and an appropriate band structure for promoting charge separation [115]. Similarly, the high-entropy perovskite oxide (BNBKL) synthesized by Fu et al. demonstrated three high-entropy-induced synergistic effects: an increased number of active sites, enhanced lattice distortion, and a narrowed band gap. These factors collectively contributed to its high degradation rate constant, as shown in Figure 10b [122].

Figure 10.

(a) Results of photocatalytic degradation of TCH by different samples [114]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier; (b) the piezo-photocatalytic performance of BNBKL [122]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier.

Building on mechanistic insights, more sophisticated structural designs, such as the creation of heterojunctions, have been proven to significantly enhance catalytic efficiency. The construction of heterojunctions based on high-entropy materials has proven to be particularly effective. For instance, Yu et al. successfully developed a Z-scheme heterojunction NAO/HEA(Ti), which not only facilitated the effective separation of electron–hole pairs but also stabilized charges with strong redox capabilities, resulting in the excellent degradation and mineralization of tetracycline (TC) [60]. In another study, Liu et al. induced the precipitation of ZnO phase within a (FeNiCuZnCo)O HEO by precisely tuning the zinc content, forming a well-integrated heterojunction. The best sample HEO-1.5 achieved a degradation rate of 99.45% for Rhodamine B (RhB), largely due to the highly efficient charge transfer across the heterojunction interface [123]. Furthermore, Dang et al. synthesized a HEO composite TiO2/(FeCoGaCrAl)2O3, achieving a significant reduction in the ecological toxicity of the treated solution, as confirmed by biotoxicity assays following oxytetracycline (OTC) degradation. This finding underscores the environmental safety of this material for remediation applications [114].

The applicability of high-entropy materials extends beyond conventional photocatalysis and has been successfully demonstrated in advanced oxidation processes, such as heterogeneous Fenton-like reactions. Sembiring et al. confirmed that the AlCrFeCoNi refractory high-entropy alloy could effectively accelerate the generation of hydroxyl radicals (·OH), thereby boosting the degradation efficiency of RhB [62]. He et al. synthesized high-entropy oxide-based MFO composites, which achieved efficient tetracycline degradation in a photo-Fenton system. This was due to the synergistic effects of a large specific surface area, enhanced light absorption, and abundant oxygen vacancies [117]. Additionally, Yu et al. developed a high-entropy spinel oxide capable of activating peroxymonosulfate (PMS), continuously generating both radical and non-radical active species, which enabled highly efficient removal of antibiotics [113].

In summary, HEMs, with their unique composition and structure, exhibit photocatalytic performance for organic pollutant degradation that surpasses that of conventional materials. The research trajectory has evolved from initially validating their fundamental activity to a deeper focus on maximizing their efficacy through compositional adjustments, structural design (such as the construction of heterojunctions), and integration into heterogeneous catalytic systems. Future research should prioritize gaining a deeper understanding of the micro-mechanisms behind the high-entropy effect, designing materials tailored for specific reactions, and evaluating their long-term stability in complex, real-world water environments to facilitate their transition toward scalable applications.

3.4. Others

The exceptional performance of high-entropy materials extends beyond the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Recent research has expanded their application boundaries to innovative areas such as sustainable chemical synthesis and highly sensitive biosensing. For instance, Ling et al. synthesized TVCNMWCA-HEO composites, which demonstrated outstanding performance in photocatalytic H2O2 production, maintaining both high efficiency and remarkable stability under diverse operational conditions [126]. The combination of these properties made these HEOs catalysts particularly promising for industrial-scale H2O2 production, where the performance consistency and long-term durability are essential. These findings mark a significant advancement in developing practical photocatalytic systems for sustainable chemical synthesis.

Xu et al. innovatively developed a split-type photoelectrochemical (PEC) biosensor for the detection of myoglobin (Myo) [127]. The biosensor was fabricated by first synthesizing PtCoFeRuMo HEO nanowires (HEANWs) with peroxidase-like activity using a solvothermal method. The catalytic properties of the HEANWs were confirmed through TMB oxidation reactions. Simultaneously, a Z-scheme heterojunction WO3/ZnIn2S4, with superior optical and photoactive properties, was prepared via a hydrothermal method to serve as the photoanode material. The photo-generated electron transfer mechanism was elucidated through diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and photocurrent response measurements. To enhance the signal, a catalytic precipitation strategy triggered by HEANWs was employed and integrated with the Z-scheme heterojunction photoanode, ultimately resulting in a high-performance PEC biosensor. The sensor provided outstanding detection performance for Myo, exhibiting a wide linear range (1.0 × 102 to 1.0 × 105 μg mL−1), a low detection limit (0.96 μg mL−1, S/N = 3), and excellent selectivity, stability, and reproducibility.

The experimental study conducted by Anandkum et al. investigated the use of HEO nanoparticles as catalysts for Cr(VI) reduction [126]. By systematically adjusting the fuel-to-oxidizer ratio during syntheses, the researchers achieved a remarkable increase in reduction efficiency from approximately 5% to 99.14%. The study also included comprehensive evaluations of the catalyst’s stability, recyclability, and regeneration capacity. The results demonstrated that these HEO photocatalysts exhibited exceptional potential for efficient hexavalent chromium reduction, with promising applications in wastewater treatment and environmental remediation. This research provided valuable insights into the design and optimization of advanced photocatalytic materials for heavy metal removal.

Nitrogen is a fundamental element for life and modern agriculture [128]. However, dinitrogen (N2), which constitutes the majority of the atmosphere, is extremely inert due to its strong triple bond, making it challenging to utilize directly [129]. While the current industrial ammonia synthesis via the Haber-Bosch process meets global demand for nitrogen fertilizers, it is an energy-intensive and results in significant carbon emissions, underscoring the urgent need for novel nitrogen fixation technologies that operate under mild conditions. The study designed and validated a novel class of HEO photocatalysts. The key innovation lies in the simultaneous incorporation of both d0 and d10 transition metal cation configurations [130]. Performance evaluations demonstrated that these new materials significantly surpassed conventional binary oxide counterparts in photocatalytic nitrogen fixation for ammonia production. Further investigation revealed that the enhancement stems not from a simple combination of d0 and d10 characteristics, but rather from a synergistic interaction between them. This synergy likely optimized the adsorption and activation of N2 and improves the separation and utilization efficiency of photogenerated charge carriers. A critical distinction from traditional nitrogen fixation pathways is the exceptional selectivity of this catalytic system for the reduction pathway. Ammonia is generated as the primary product, with negligible formation of nitrate ions. This precise control over the reaction trajectory not only indicates superior catalytic performance but also mitigates the environmental risk of secondary nitrate pollution, emphasizing the system’s green and sustainable advantage.

In others, the refractive index is a critical parameter that governs the performance of photocatalytic materials, as it directly influences their light absorption, scattering, and confinement behaviors. This parameter is affected by multiple factors, including material composition, crystalline structure, pressure, temperature, and doping conditions. Rational design and modulation of refractive index can significantly enhance the overall efficiency of photocatalytic systems. Strategies such as nanostructuring, heterojunction engineering, and photoluminescence enhancement have been employed to improve charge separation efficiency and light-harvesting capability. Additionally, tuning the refractive index facilitates the extension of the optical absorption edge into the visible range, strengthens light–matter interactions, and reduces reflective losses at surfaces, thereby boosting photocatalytic performance [131].

4. Structure–Activity Relationship

HEMs are broadly defined as a class of multi-component solid solutions stabilized primarily by the high-entropy effect. To establish a focused and in-depth investigation, this study narrows its scope to three well-established and representative systems: HEAs, HEOs, and HESs, while excluding less common material categories. This focused approach aims to facilitate a deeper understanding of the fundamental mechanisms common to HEMs. For each material category, we will specifically differentiate and examine the two distinct functional modes: their use as standalone materials and their synergistic cooperation in composites with other semiconductors. This comparative approach is pivotal to deciphering the structure-property relationships and mapping the application landscape.

This study reveals that the exceptional catalytic performance of HEAs as standalone functional units stems from the synergistic interplay of three core mechanisms. Firstly, at the electronic level, synergistic modulation occurs. The multi-principal-element nature induces a pronounced “cocktail effect,” which optimizes the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates by modulating the d-band center [65]. Concurrently, the alloy matrix itself acts as an efficient electron reservoir and transport pathway, significantly enhancing charge separation and transfer. Second, defect engineering at the structural level plays a critical role. Intrinsic lattice distortion, coupled with abundant defects such as nanocrystals and twins, creates a high density of active sites for catalytic reactions. Finally, compositional advantages are evident both in terms of economy and functionality. The multi-component system not only enhances the surface adsorption of reactants but also, through the prevalent use of non-precious metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni), ensures high performance and demonstrates promising potential for large-scale application [65,71,93].

A series of experiments provided insights into the design flexibility and performance origins of HEMs from multiple perspectives. (1) The photothermal conversion capability of these materials, achieved through mechanisms like d-d transition for broad-spectrum absorption and localized heating, was shown to synergistically drive both dye degradation and antibacterial processes [58,119,124]. (2) Additionally, strategies like introducing rare-earth elements (e.g., La) to modulate the band structure and defect concentration (e.g., oxygen vacancies), or constructing amorphous–crystalline heterointerfaces and nanotwins, were shown to establish a “self-stabilizing” catalytic cycle, thereby significantly enhancing intrinsic activity and stability [71]. (3) These materials can also be engineered as n-type narrow-bandgap semiconductors, where the generated superoxide anion radicals (·O2−) effectively degrade pollutants, and their intrinsic magnetism facilitates material recovery [65,124]. (4) Most notably, HEAs function as ideal electron reservoirs. When integrated with semiconductors to form Schottky junctions, they enable highly efficient charge separation. DFT calculations confirm that the electronic synergy among their surface multi-components significantly promotes multi-electron reactions, such as CO2 reduction. Collectively, these findings delineate a clear “composition-structure-property” relationship for HEAs.

When integrated with semiconductors, HEAs not only retain their advantageous intrinsic properties as standalone catalysts—such as high-density active sites and electron modulation capability—but also exhibit the crucial characteristic of synergistic catalysis. A representative example from this work is the HEA/CdS composite, which successfully coupled the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution (the reduction half-reaction) with the selective oxidation of cinnamyl alcohol to cinnamaldehyde (the oxidation half-reaction) within a single and unified system [106,107]. The underlying mechanism involved the precisely tailored valence band position of the CdS quantum dots, which provided sufficient oxidative power to drive the conversion of cinnamyl alcohol, while strategically avoiding the over-oxidation of cinnamaldehyde to cinnamic acid, thereby achieving high selectivity. This tandem reaction process effectively showcases the significant potential of composites for designing and implementing sophisticated, highly efficient photocatalytic reaction systems. In composite with In4Se3, the band structure, optical properties, and crystalline phases of such materials exhibit a high degree of sensitivity to the stoichiometric ratio between the chalcogen element and indium [83]. Precise control over this ratio allows for effective tuning of the optical absorption range, charge carrier concentration, and even the type of electrical conductivity. This tunability provides a crucial dimension for compositional engineering in designing high-performance optoelectronic and catalysts.

Our investigation into HEA/carbon-based composites revealed that their superior performance originated from complex synergistic effects at the interface. XPS analysis confirms the diversity of elemental valence states at the interface (e.g., the coexistence of Cu2+ and Pt0), which not only facilitates multiple pathways for redox reactions but also leads to the formation of a built-in electric field at the heterojunction through band engineering [60]. This interfacial field significantly enhances visible-light harvesting and accelerates the separation and migration efficiency of photogenerated charge carriers.

When HESs are coupled with other semiconductors, their performance-enhancing mechanisms can be categorized into two representative strategies, depending on the nature of coupled materials. The first strategy leverages the plasmonic effect of noble metal components. In certain systems, the localized surface plasmon resonance generated by Ag nanoparticles significantly enhances interfacial light absorption and carrier generation [96,125]. However, this advantage stems from specific material combinations. The second, more widely applicable strategy involves the use of non-noble metal cocatalysts. For example, transition metal sulfides are commonly employed to boost the hydrogen evolution performance of photocatalysts, owing to their low cost and excellent electrical conductivity. This strategy provides a functional complement to noble metal cocatalysts and offers a cost-effective alternative [90,94].

When employed as standalone catalysts, HEOs not only embody the material universality but also demonstrate multifaceted performance advantages due to their unique compositional tunability. First, the incorporation of magnetic HEOs provides additional benefits to the photocatalytic process. Their inherent magnetism may enhance light absorption by influencing electron spin states and may directly participate in the reaction pathway, accelerating the decomposition and reduction of key intermediates. Second, the intrinsic structural distortions of the high-entropy system (e.g., lattice strain and charge disorder), combined with macroscopic structural control achieved through strategies like micro-spheroidization, collectively generate a high density of active sites [92,115,118,122]. This leads to a significant enhancement in catalytic activity while preserving the material’s excellent thermal stability and mechanical robustness. Ultimately, these coordinated micro- and macro-structural modifications work synergistically to optimize the intrinsic optoelectronic properties of HEOs. This enables precise tuning of their band structure for efficient alignment with the solar spectrum, thereby substantially improving the efficiency of visible-light-driven catalytic reactions.

5. Summary and Outlook

A thorough understanding of the origins of HEMs’ exceptional performance necessitates an exploration of the underlying mechanisms. HEMs display remarkable synergistic effects and catalytic benefits while reducing reliance on costly and hazardous elements. Compared to other metal-based compounds, HEMs possess a range of superior characteristics, including high configurational entropy, lattice distortion, cocktail effects, sluggish diffusion kinetics, and exceptional mechanical/chemical stability. Additionally, they demonstrate outstanding thermal and electrical conductivity, as well as corrosion resistance. Due to their unique multi-element synergistic effects, HEMs hold extraordinary potential in photocatalysis, as they simultaneously enhance light absorption, charge separation, and surface reactivity, while minimizing dependence on scarce noble metals.

HEMs inherently exhibit low thermal conductivity, which leads to pronounced localized heating under the xenon lamp irradiation. This thermal effect significantly contributes to catalytic processes by enhancing atomic mobility and accelerating reaction kinetics [132]. For instance, during photocatalytic antibacterial testing, time-resolved measurements of metal ion leaching, particularly Cu2+ release, revealed the dominant role of this element in microbial inactivation. This demonstrates how selective element incorporation can optimize the functionality of HEM for specific applications [58]. The dynamic surface chemistry of these alloys further amplified their catalytic potential. Chromium-containing formulations rapidly form hybrid metal–oxide interfaces under reaction conditions, with XPS analyses confirming the coexistence of metallic (active sites) and semiconducting (redox-active) phases. Although this dual-phase configuration is also observed in conventional catalysts, it achieves exceptional stability in HEMs due to their inherent configurational entropy. Spectroscopic studies of compositionally tuned HEMs reveal programmable light absorption characteristics: Ti/Cu-rich variants show strengthened UV response, while V/Cr-dominated compositions exhibit superior visible-light activity. This tenability, driven by the synergistic interplay of d-electron configurations across multiple principal elements, allows for precise matching of HEM properties with target reaction energetics. The system’s adaptability suggests promising potential for developing reaction-specific catalytic platforms, although further investigation is needed to assess long-term stability under continuous irradiation.

However, the successful translation of these design concepts into tangible materials depends on the development of precise and controllable synthetic strategies. The controllable synthesis of HEMs requires systematic process control strategies that involve the careful regulation of multiple critical parameters. First, the temperature range during heat treatment must be strictly controlled, including optimization of heating and cooling rates, as well as precise regulation of dwell time at target temperatures. Second, the processing atmosphere must be carefully engineered by selecting appropriate gas conditions (reducing, oxidizing, or inert), controlling gas composition and partial pressures, and regulating gas flow dynamics. Additionally, compositional tuning is achieved through precise stoichiometric control of precursor mixtures, real-time monitoring of phase formation, and verification of uniform elemental distribution. These controlled synthetic protocols collectively enable the rational design of HEMs with tailored characteristics, such as phase purity, microstructural features, defect engineering, and functional performance, while establishing a foundation for reproducible and large-scale production. Future efforts should focus on in situ monitoring techniques and machine learning-assisted process optimization to further enhance synthesis precision and efficiency for a wide range of advanced applications.

Overcoming this critical challenge hinges on the development of sophisticated theoretical methods and computational capabilities. Given the intrinsic atomic randomness of HEMs, the creation of comprehensive theoretical methodologies is essential. This requires the establishment of accurate thermodynamic and kinetic models. By integrating multi-scale computational approaches, such as first-principles calculations, molecular dynamics simulations, and statistical mechanics, we can build a solid theoretical foundation for predicting and identifying active catalytic sites in high-entropy systems. To accelerate the rational design of these complex catalysts, three critical computational advancements must be pursued: refining theoretical calculation systems to handle compositional complexity, establishing extensive high-throughput property databases, and developing robust machine learning models trained on sufficiently large datasets. These integrated computational tools will enable efficient screening of potential catalysts, identification of superior active structures, and prediction of key structure-property relationships, while significantly reducing reliance on traditional trial-and-error approaches. The synergy between these advanced computational methods and experimental validation will propel the development of HEMs for diverse catalytic applications. Future research should focus on improving model accuracy and expanding its applicability to broader classes of high-entropy systems.

The advantages of HEMs can be summarized in three key aspects:

- Diversity of High-Entropy Material Categories

The family of HEMs extends well beyond the well-established high-entropy alloys and oxides. Emerging members, including high-entropy selenides, bismuthides, oxynitrides, phosphides, sulfides, hydroxides, anion-regulated materials, and metal–organic frameworks, have significantly broadened the scope of this field and reinvigorated its research. To fully unlock the potential of these materials, it is essential to employ theoretical calculations to predict their intrinsic properties in advance. This guided approach enables the rational selection and design of HEMs that are best suited for specific applications, ensuring they perform optimally in their respective domains.

- 2.

- Diversity of Synthesis Methodologies

The synthesis of HEMs generally falls into two main categories: thermal processes and mechanical methods. Innovation within these pathways is key to advancing the field. For instance, thermal processes can be revolutionized by employing novel energy sources, such as laser or electromagnetic heating. Xie et al. has successfully synthesized a five-component HEA employing a CO2 laser under atmospheric conditions to fulfill highly effective and cost-effective electrocatalysts for seawater splitting [133]. These methods offer extremely high heating/cooling rates and provide unique non-equilibrium processing conditions, which are essential for achieving the desired phase purity and microstructures.

- 3.

- Diversity of Application Prospects

While this review highlights applications in CO2 reduction, hydrogen evolution, and organic pollutant degradation, it also explores promising areas such as Cr(VI) reduction and H2O2 production. Future exploration should focus on integrating these processes to create synergistic catalytic systems. For example, in situ produced H2O2 from a reduction reaction could be immediately utilized in a Fenton-like reaction for advanced oxidation processes. By precisely controlling the in situ generation rate of H2O2, the overall catalytic efficiency could be optimized. Furthermore, the recovery and reduction of valuable metals from industrial wastewater represent another significant avenue for practical applications.

In addition, the vast compositional space of HEMs presents a fundamental challenge for their rational design. When considering only metallic elements, the number of possible five-component combinations selected from approximately 80 elements is enormous, approximately 24 million (C(80, 5) ≈ 24,040,016). This combinatorial space becomes even more astronomical when incorporating concentration gradients, higher component numbers, and synthesis parameters, rendering traditional trial-and-error approaches completely inadequate. As a result, the development of efficient high-throughput screening methods is crucial for accelerating the discovery of high-performance HEMs. In this context, machine learning offers a highly promising solution.

The key to this approach lies in building a data-driven predictive model. Important descriptors related to phase formation ability and properties, such as mixing entropy, atomic size difference, and elemental property statistics, are first extracted from experimental or computational databases as inputs for the model. Supervised learning algorithms, including Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Machines, are then employed to train the model, enabling it to capture the complex relationships between these descriptors and target properties (e.g., hardness, formation energy, phase stability). Once trained, the model can rapidly screen tens of millions of virtual compositional combinations, narrowing the focus to a few highly promising candidates for subsequent experimental validations.

Despite the significant potential demonstrated by HEMs in photocatalysis, their translation toward practical applications faces several critical challenges. First, issues related to material stability and reaction standardization must be addressed [134]. For instance, nanoparticle agglomeration during reactions, deactivation due to photothermal effects under prolonged illumination, and the sensitivity of photocatalytic rates to incident light wavelength and intensity are often oversimplified or overlooked in fundamental studies [135,136,137,138]. However, these factors significantly constrain performance in real-world environments and the feasibility of large-scale implementation. Second, there is substantial room for further exploration of the underlying mechanisms. Future research should prioritize systematic investigation of the dielectric Mie resonance effects in HEM systems. Understanding how resonance modes, supported by high-entropy compositions, interact with their inherent high configurational entropy through electromagnetic field localization will be crucial for unraveling the origin of enhanced photocatalytic activity and guiding the rational design of the next-generation and high-performance photocatalysts.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, investigation, W.B.; supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing, F.C.; investigation, K.L.; investigation, Y.K.; Conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, W.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant number 2024YFE0211700).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, G.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, J.; Jiang, D. Renewable Energy in China’s Abandoned Mines. Science 2023, 380, 699–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhu, R.; Snaith, H.J. Unlocking Interfaces in Photovoltaics. Science 2024, 384, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rode, A.; Carleton, T.; Delgado, M.; Greenstone, M.; Houser, T.; Hsiang, S.; Hultgren, A.; Jina, A.; Kopp, R.E.; McCusker, K.E.; et al. Estimating a Social Cost of Carbon for Global Energy Consumption. Nature 2021, 598, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenderich, K.; Mul, G. Methods, Mechanism, and Applications of Photodeposition in Photocatalysis: A Review. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14587–14619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatkhande, D.S.; Pangarkar, V.G.; Beenackers, A.A.C.M. Photocatalytic Degradation for Environmental Applications—A Review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2002, 77, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]