A Comparative Electrochemical Study of Pt and Ni–Oxide Cathodes: Performance and Economic Viability for Scale-Up Microbial Fuel Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

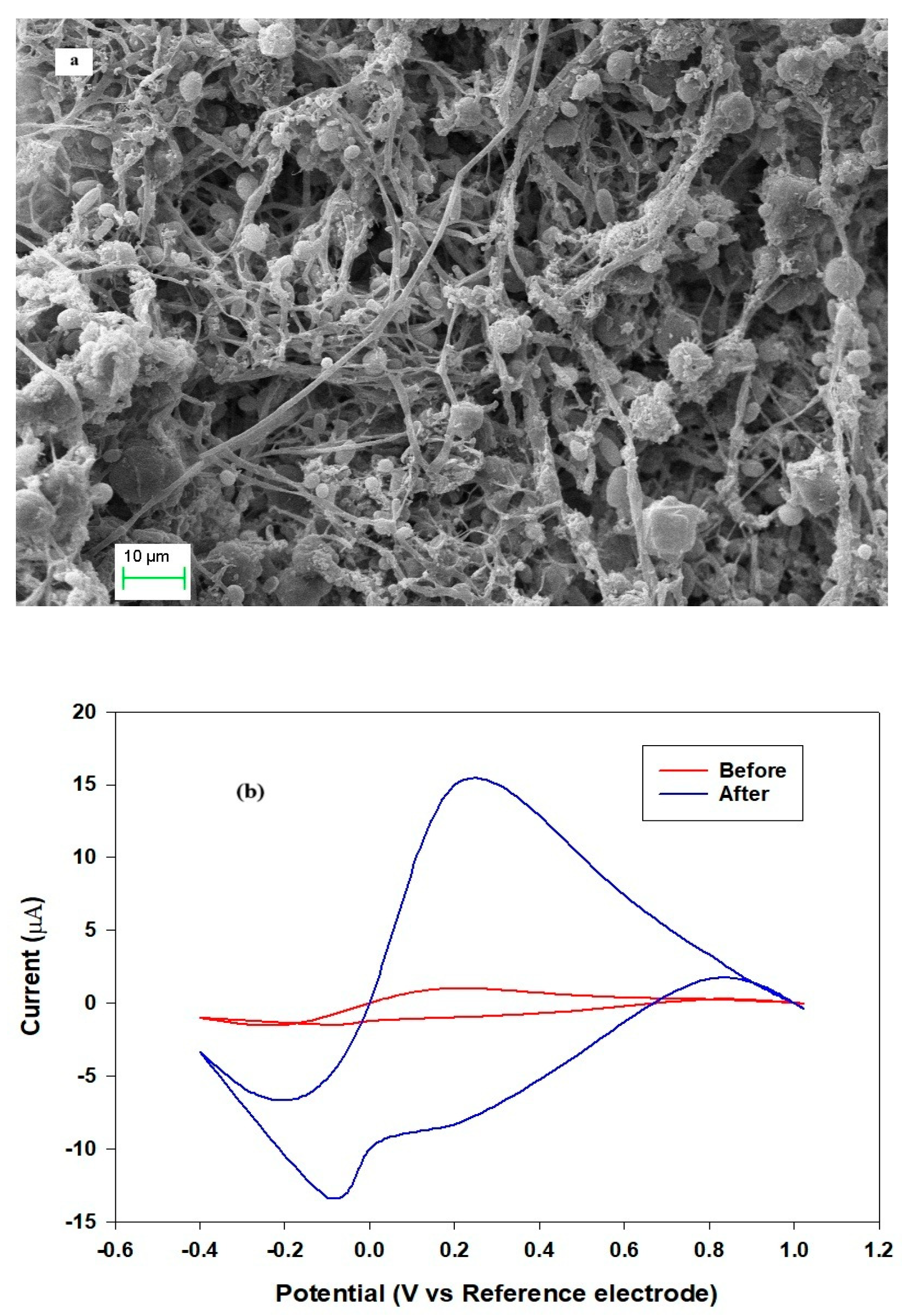

2.1. Microorganism Attachment

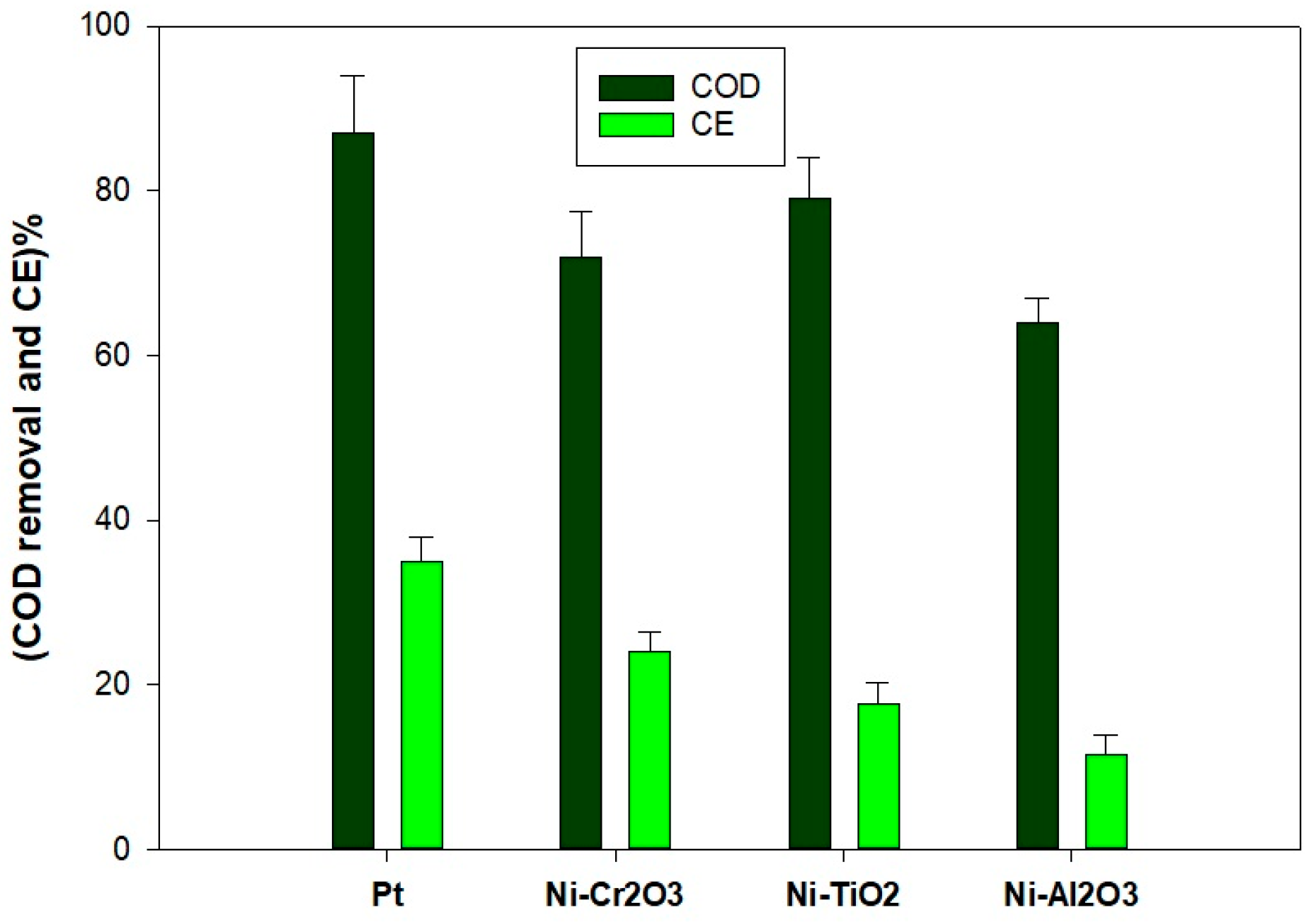

2.2. Power Density and COD Removal

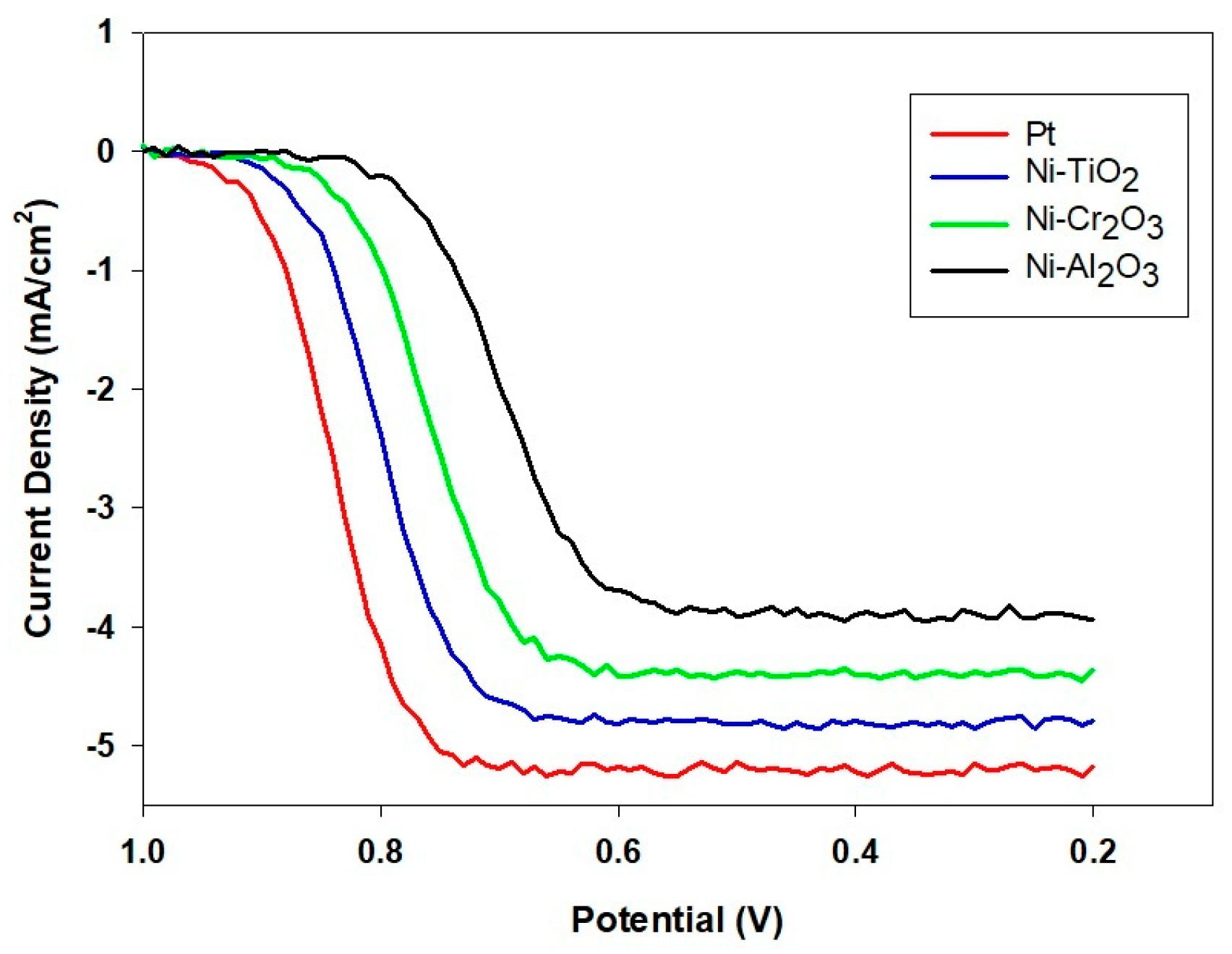

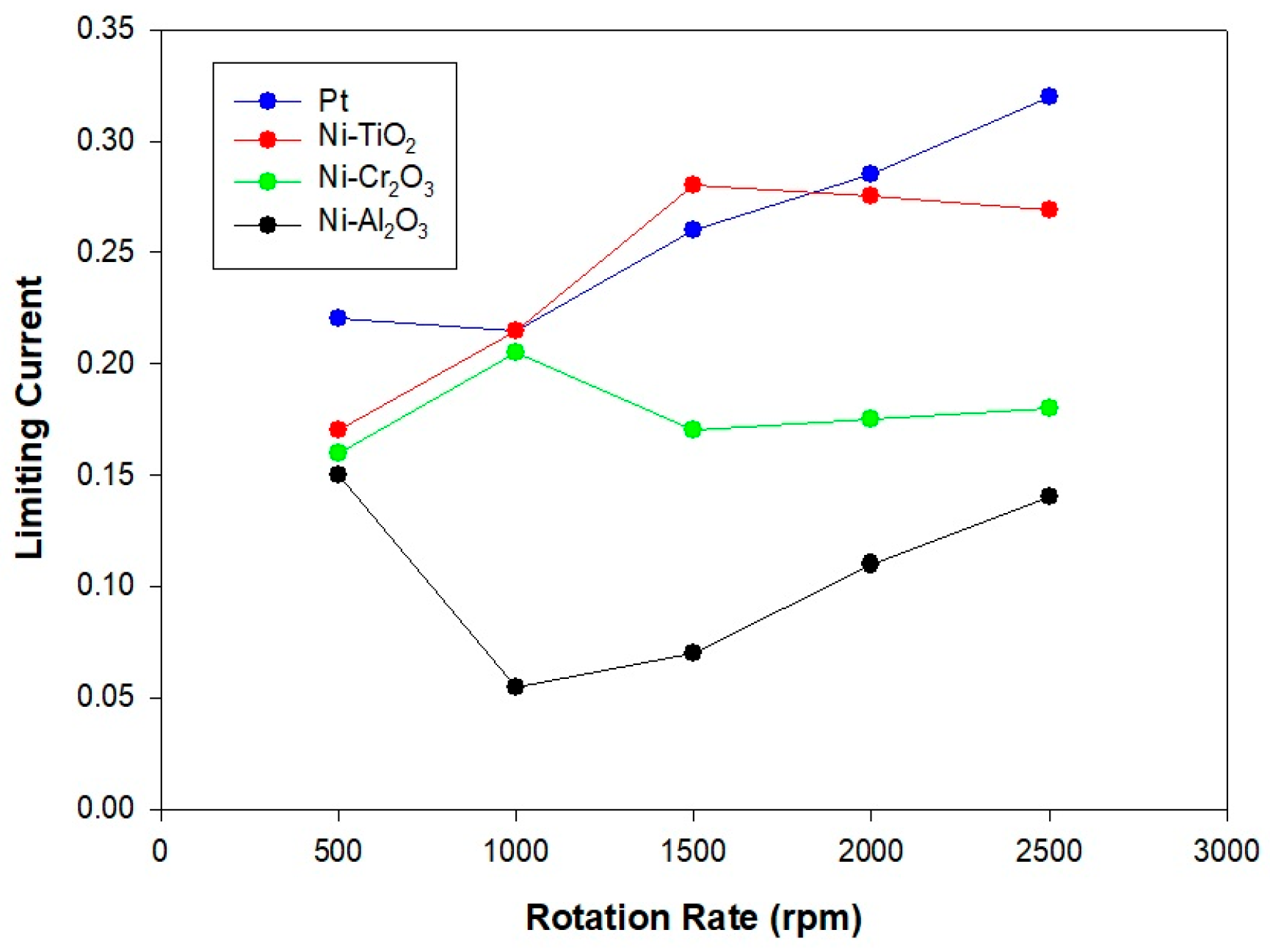

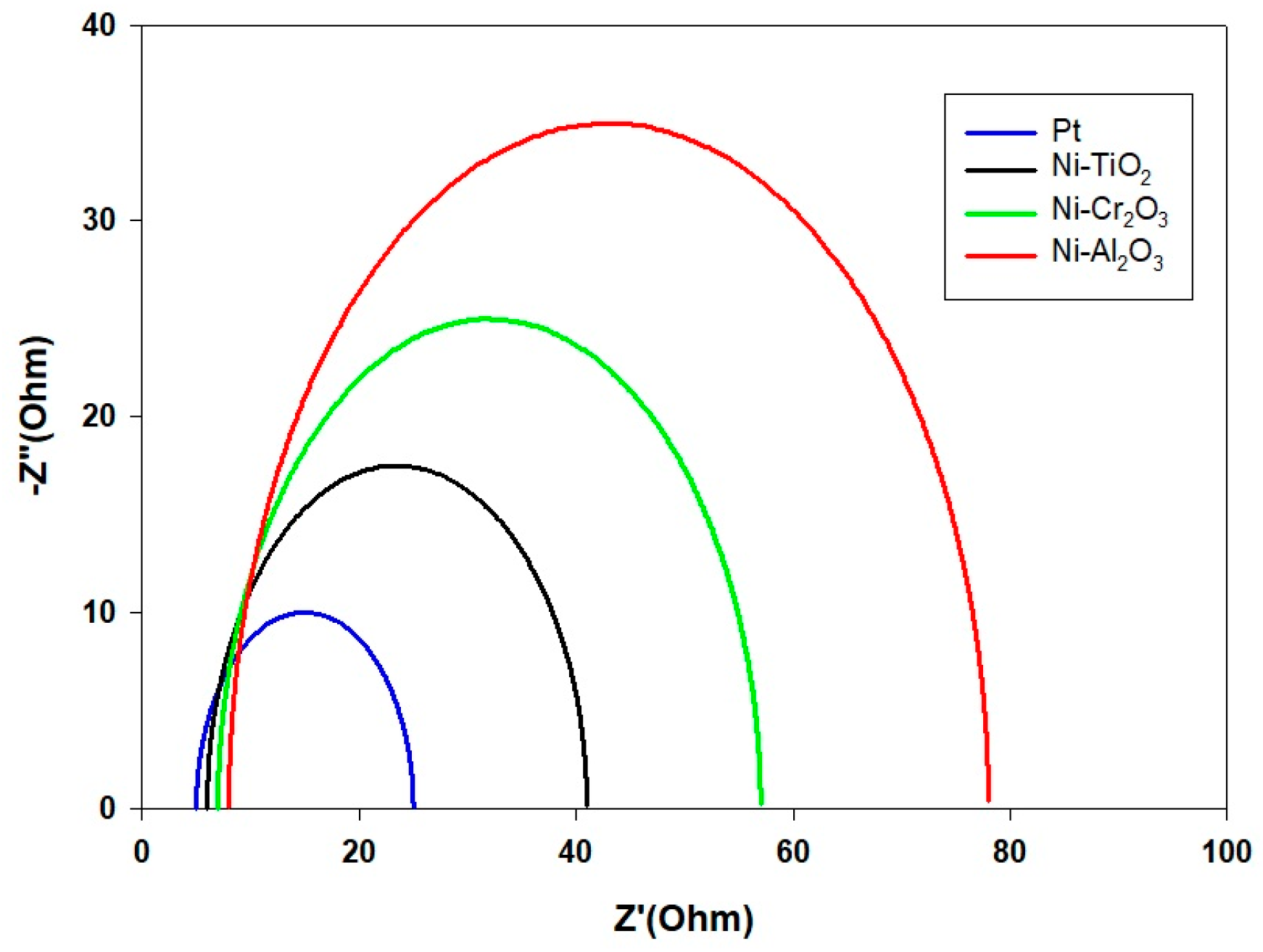

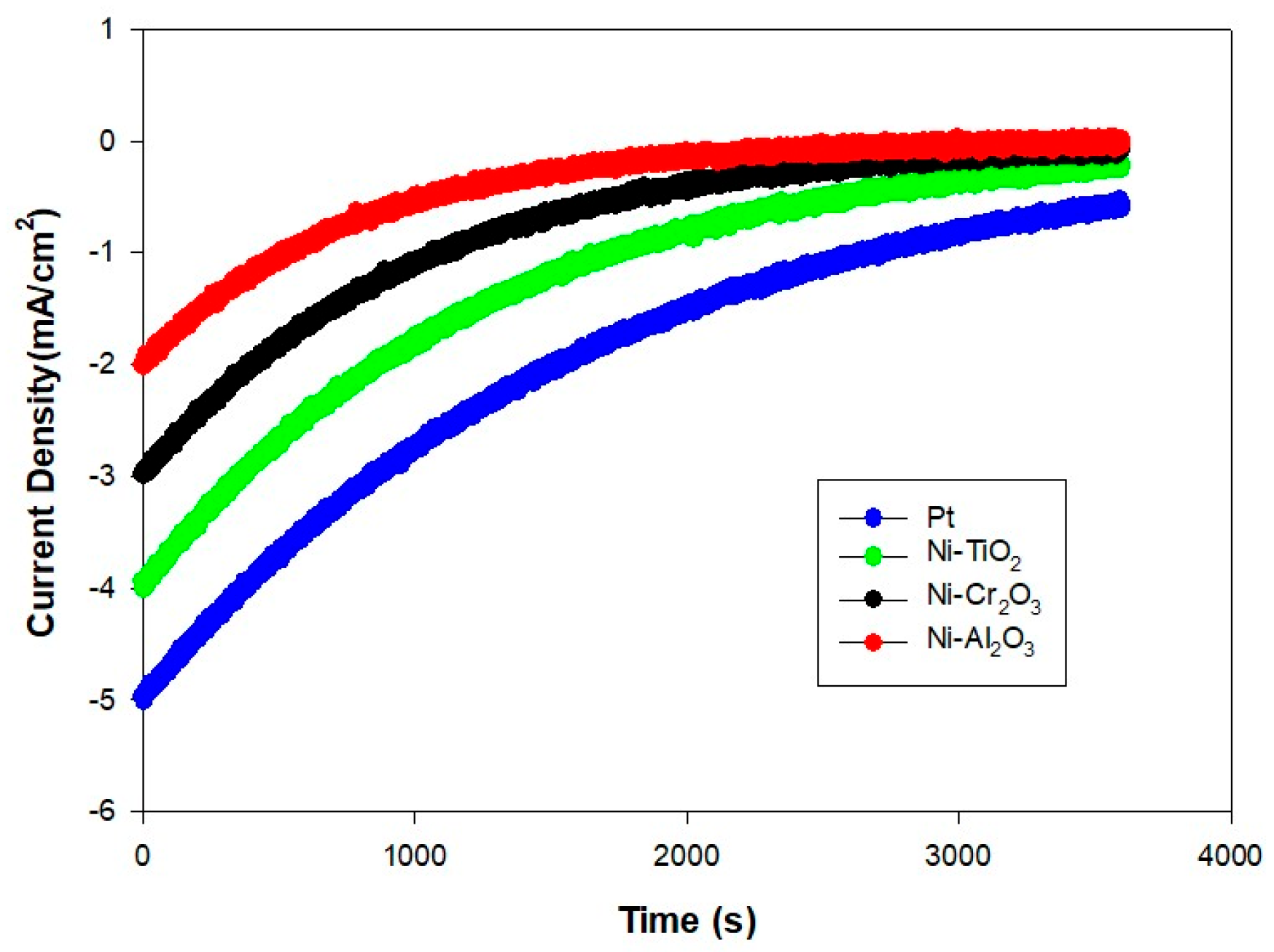

2.3. LSV and EIS Analysis

2.4. Techno-Economic Evaluation: A Performance-Normalized Cost Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Nickel Nanocomposite Preparation

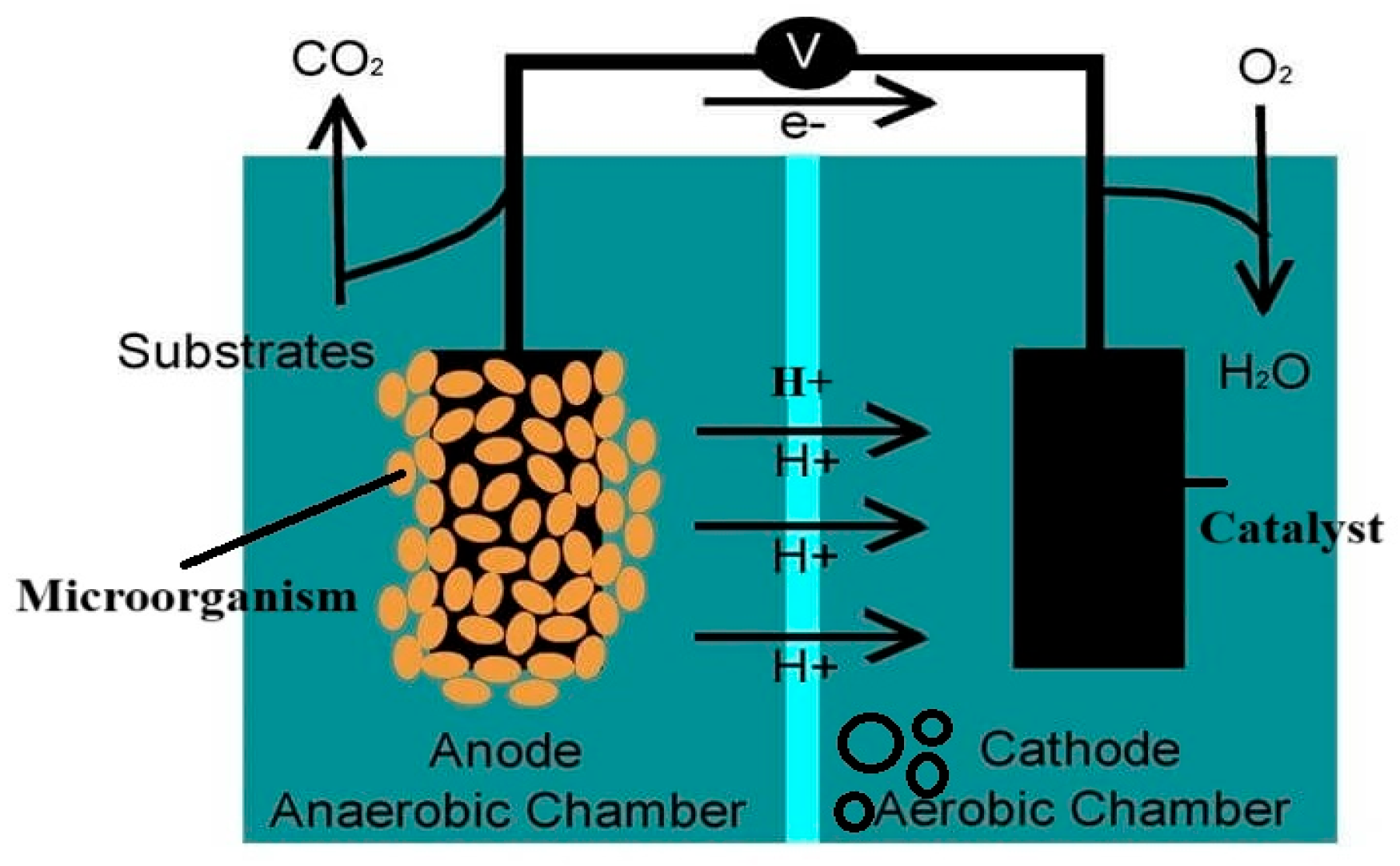

3.2. MFC Configuration

3.3. Media

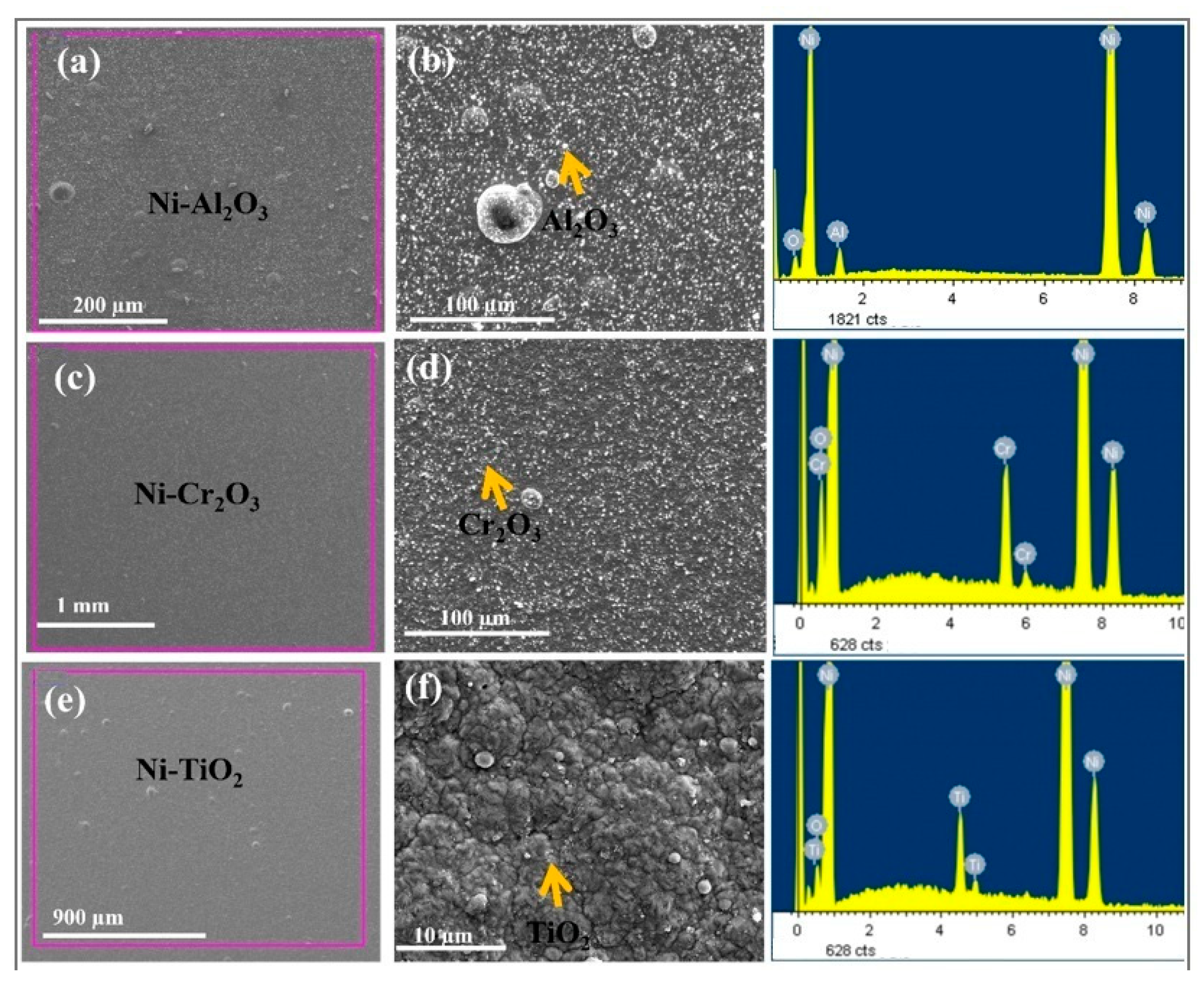

3.4. Surface Microstructure with EDS Results

3.5. Analysis and Calculations

3.6. Electrochemical Characterization

3.6.1. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

3.6.2. Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) and Rotating Disk Electrode (RDE)

3.6.3. Electrochemical Active Surface Area (ECSA)

3.6.4. Chronoamperometry (CA)

4. Conclusions

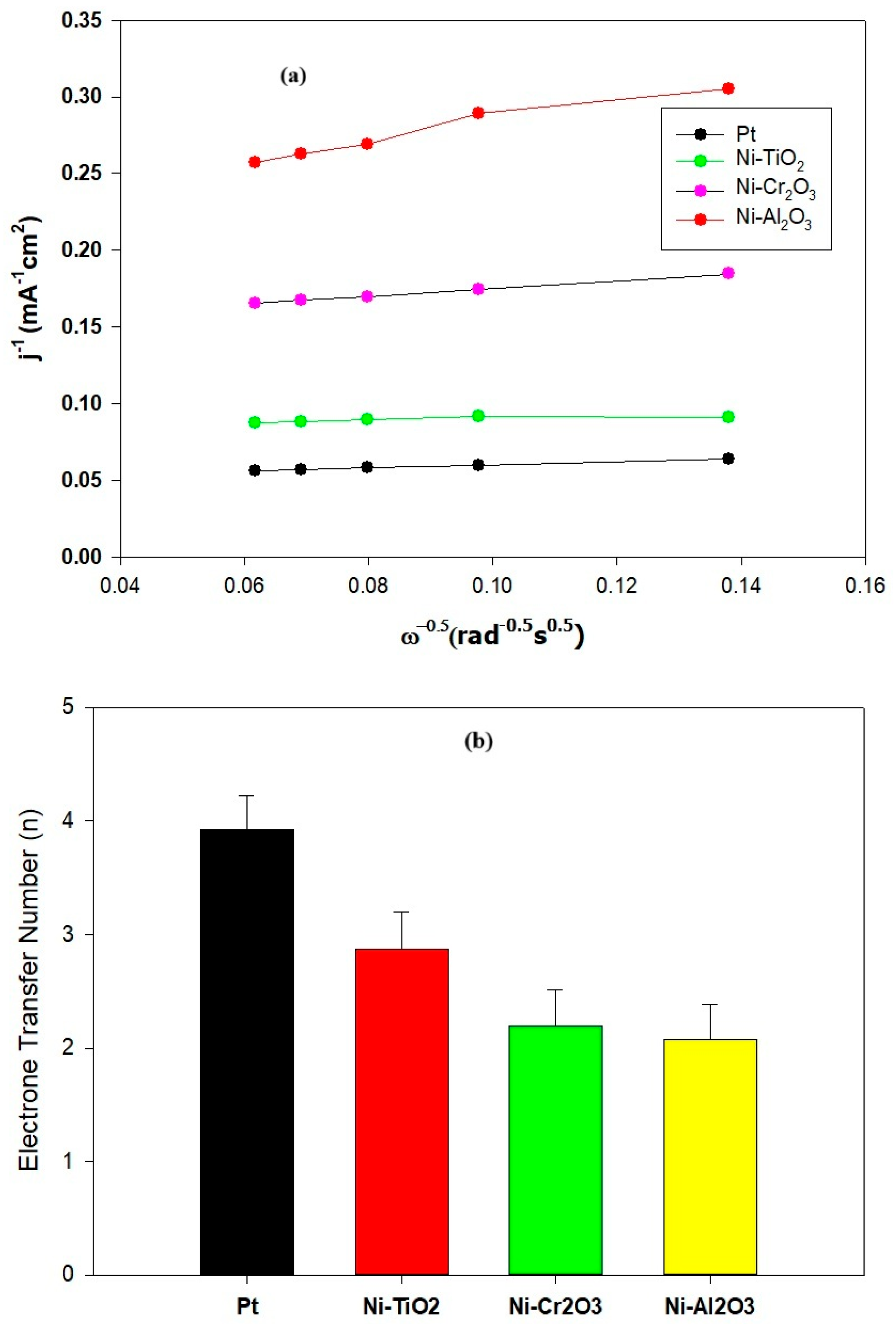

- (a)

- Pt demonstrated the overall best performance, achieving the highest power density (275 mW/m2) and COD removal rate (87%), underscoring its exceptional catalytic activity for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). Among the nickel-based materials, Ni-TiO2 exhibited the most notable performance (224 mW/m2, 79% COD removal), benefiting from its capacity to facilitate electron transfer through its semiconductor properties. Ni-Cr2O3 presented moderate performance (162 mW/m2, 72% COD removal), attributed to its enhanced conductivity and presence of oxygen adsorption sites, whereas Ni-Al2O3 showed the least effectiveness (134 mW/m2, 64% COD removal, CE 11.6%) due to its insulating characteristics, which hindered electron flow and catalytic activity.

- (b)

- From an economic perspective, the performance-normalized cost analysis (Table 1) highlights the substantial financial advantage of Ni-based catalysts relative to Pt. Although Pt achieves the highest electrochemical activity, its extremely high material cost leads to a performance-normalized cost of approximately USD 636/W, compared with USD 3.35/W for Ni–TiO2, USD 3.70/W for Ni–Cr2O3, and USD 2.99/W for Ni–Al2O3. This means that Ni–TiO2 delivers comparable power density at less than 1% of the cost of Pt, making it the most cost-effective option among the tested materials. These findings demonstrate that, when cost considerations are incorporated, Ni-oxide catalysts, particularly Ni–TiO2, offer a far more practical route for future MFC development than Pt-based cathodes.

- (c)

- Koutecký–Levich analysis illustrated the fundamental reasons behind this performance ranking. Pt enabled the ideal 4-electron transfer route (O2 + 4H+ + 4e− → 2H2O), while the Ni-based composites predominantly utilized a less effective 2-electron pathway (O2 + 2H+ + 2e− → H2O2). Significantly, Ni-TiO2’s slightly higher electron transfer number (n ≈ 2.8) compared to Ni-Cr2O3 and Ni-Al2O3 (n ≈ 2.3) indicates that its semiconductor characteristics foster more favorable ORR kinetics than the insulating oxide counterparts.

- (d)

- From an economic perspective, Ni-based catalysts are significantly more affordable than Pt, suggesting potential advantages for future large-scale studies. Although Ni-Al2O3 has the lowest cost per gram, its subpar performance and inefficient 2-electron pathway render it impractical. Ni-TiO2 offers the most advantageous balance between cost and electrochemical efficacy.

- (e)

- Consequently, considering both technical performance and the associated reaction kinetics, Ni-TiO2 shows promising performance among the Ni-oxide cathodes. However, it should be noted that it’s CE is still in the medium level. And it is an essential obstacle which should be addressed in the future developments. Its ability to partially facilitate a more efficient 4-electron pathway, along with its balanced performance and cost-effectiveness, suggests that Ni-TiO2 could become a practical alternative to Pt after further durability optimisation. It is important to note that the present durability testing was limited to 3600 s and long-term stability in real wastewater has not yet been demonstrated; therefore, the scalability claim remains preliminary.

- (f)

- The novelty of this work lies in offering a unified electrochemical and economic comparison of three Ni–oxide supports under identical MFC conditions, enabling clearer structure–performance correlations than previously reported studies. These insights may inform future cathode optimization efforts, although further research is required to establish comprehensive design guidelines.

- (g)

- Future research should concentrate on methods to enhance the electron transfer number of Ni-based catalysts, such as through doping, the incorporation of heteroatoms, or the creation of heterojunctions with more conductive supports, to improve their performance towards achieving the desired 4-electron limit.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MFC | Microbial Fuel Cell |

| ORR | Oxygen Reduction Reaction |

| Pt | Platinum |

| Ni | Nickel |

| Ni–TiO2 | Nickel–Titanium Dioxide |

| Ni–Cr2O3 | Nickel–Chromium(III) Oxide |

| Ni–Al2O3 | Nickel–Aluminum Oxide |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CE | Coulombic Efficiency |

| LSV | Linear Sweep Voltammetry |

| CV | Cyclic Voltammetry |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| Rs | Solution Resistance |

| Rct | Charge-Transfer Resistance |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy |

| CA | Chronoamperometry |

References

- Khan, M.J.; Das, S.; Vinayak, V.; Pant, D.; Ghangrekar, M. Live diatoms as potential biocatalyst in a microbial fuel cell for harvesting continuous diafuel, carotenoids and bioelectricity. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, A.; Swaminathan, J.; Mangal, A.; Ghoroi, C.; Lens, P.N. Comparing efficacy of anodic and cathodic chambers in a low-cost algae-assisted microbial fuel cell for textile wastewater remediation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 187, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.K.; Manangath, S.P.; Gajalakshmi, S. Innovative pilot-scale constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell system for enhanced wastewater treatment and bioelectricity production. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.H.; Gomaa, O.M.; Hassan, R.Y. Bio-electrochemical frameworks governing microbial fuel cell performance: Technical bottlenecks and proposed solutions. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 5749–5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moqsud, M.A.; Akamatsu, F. Integrating plant microbial fuel cells into green infrastructure: Tackling heat islands and powering sensors. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 32, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M.; Ahmad, A.; Das, S.; Ghangrekar, M. Metal organic frameworks as emergent oxygen-reducing cathode catalysts for microbial fuel cells: A review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 11539–11560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lu, M.; Wang, F.; Hou, Y. Improving power output in microbial fuel cells with free-standing CoCx/Co@CC composite anodes. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 469, 143290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douma, M.N.K.; Ondel, O.; Tsafack, P.; Mieyeville, F.; Kengnou, N.A. Microbial fuel cell: Investigation of the electrical power production of cow dung and human faeces using 3D-printed reactors. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 29, 102036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ieropoulos, I.A. Enhancing microbial fuel cell performance using ceramic additive as biomedia. Renew. Energy 2025, 244, 122738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, B.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. Digestate derived porous biochar through thermochemical nitrogen self-doping as an efficient cathode catalyst for microbial fuel cells. Renew. Energy 2025, 247, 123033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Sodric, O.; Baeza, J.A.; Guisasola, A. Enhancing bioelectrochemical hydrogen production from industrial wastewater using Ni-foam cathodes in a microbial electrolysis cell pilot plant. Water Res. 2024, 256, 121616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharti, H.; Hitar, M.E.H.; Touach, N.; Lotfi, E.M.; El Mahi, M.; Mouhir, L.; Fekhaoui, M.; Benzaouak, A. Generating sustainable bioenergy from wastewater with Ni2V2O7 as a potential cathode catalyst in single-chamber microbial fuel cells. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, S.; Song, L.; Dong, J.; Pan, X. Insight into the promoting effect of support pretreatment with sulfate acid on selective catalytic reduction performance of CeO2/ZrO2 catalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 608, 2718–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Chen, D.; He, Z.; Ma, H.-H.; Wang, L.-Q. Experimental study on detonation propagation characteristics of hydrogen-nitrous oxide at stoichiometric and fuel-lean conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 25795–25807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, G.D.; Chakraborty, I.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Mitra, A. TiO2/Activated carbon photo cathode catalyst exposed to ultraviolet radiation to enhance the efficacy of integrated microbial fuel cell-membrane bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Chhabra, M. Performance of photo-microbial fuel cell with Dunaliella salina at the saline cathode. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 19, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, S.; Chen, D.; Dong, S.; Li, N.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, J. Hollow Zn/multi-heteroatom carbon polyhedra derived from ZIF-8 as efficient cathode catalysts for microbial fuel cells. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 320, 122495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellatur, C.S.; Vinothkumar, V.; Kuppam, P.K.R.; Oh, J.; Kim, T.H. Methanol-Tolerant Pd-Co Alloy Nanoparticles on Reduced Graphene Oxide as Cathode Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction in Fuel Cells. Catalysts 2025, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Gundepuri, I.S.; Ghangrekar, M.M. High specific surface area graphene-like biochar for green microbial electrosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide and Bisphenol A oxidation at neutral pH. Environ. Res. 2025, 275, 121374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, N.; Dhakal, H.N.; Tjong, J.; Jaffer, S.; Yang, W.; Sain, M. Recent advances and future perspectives of carbon materials for fuel cell. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Jin, Z.; Yang, H.; Tu, C.; Che, F.; Russel, M.; Song, X.; Huang, W. Study on the management efficiency of lanthanum/iron co-modified attapulgite on sediment phosphorus load. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, S.; Li, C. Metal-based cathode catalysts for electrocatalytic ORR in microbial fuel cells: A review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, M.; Santoro, C.; Serov, A.; Kabir, S.; Artyushkova, K.; Matanovic, I.; Atanassov, P. Air breathing cathodes for microbial fuel cell using Mn-, Fe-, Co-and Ni-containing platinum group metal-free catalysts. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 231, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, D.Z.; Amin, R.; Zhran, M.; Abd El-Aziz, Z.K.; Mahmoud, M.; Hassan, H.M.; El-Khatib, K. The enhancement of microbial fuel cell performance by anodic bacterial community adaptation and cathodic mixed nickel–copper oxides on a graphene electrocatalyst. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, J.; Han, D.; Chang, S.; Yang, R.; An, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, F. Potential of core-shell NiFe layered double hydroxide@ Co3O4 nanostructures as cathode catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction in microbial fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2020, 453, 227877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Chen, Y.; Wen, Q.; Lin, C.; Gao, H.; Qiu, Z.; Yang, L. Synergistic effect of bimetallic bioelectrocatalysis and endogenous soluble electron mediators for functional regulation of electroactive biofilms. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 491, 144789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Vijay, A. Unlocking the potential of microbial fuel cells: A comprehensive review of substrates, emerging applications, and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 31, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, J.; Liu, L.-y.; Wang, F.; Kong, Z.; Wang, Y. Defect spinel oxides for electrocatalytic reduction reactions. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 3547–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Siddiqui, V.U.; Rehman, W.U.; Akram, M.K.; Siddiqi, W.A.; Alosaimi, A.M.; Hussein, M.A.; Rafatullah, M. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using Acorus calamus leaf extract and evaluating its photocatalytic and in vitro antimicrobial activity. Catalysts 2022, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharan, Z.; Naji, L.; Madanipour, K.; Dabirian, A. Complex electrochemical study of reduced graphene oxide/Pt produced by Nd:YAG pulsed laser reduction as photo-anode in polymer solar cells. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 880, 114927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Y.; Raj, R.; Ghangrekar, M.; Nema, A.K.; Das, S. Critical assessment of advanced oxidation processes and bio-electrochemical integrated systems for removing emerging contaminants from wastewater. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 1912–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.B.; Gonçalves, L.F.; Claudio, F.L.; Souza, J.A.; Júnior, G.C.; Alves, E.M.; Paim, T.D.P. Sustainable Production of Maize with Grass and Pigeon Pea Intercropping. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1246, Correction in Agriculture 2024, 14, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.A.; Shayesteh Zadeh, A.; Peters, B. Ethylene Polymerization Activity vs. Grafting Affinity Trade-off Revealed by Importance Learning Analysis of In Silico Phillips Catalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 19166–19181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiljanić, M.; Srejić, I.; Georgijević, J.P.; Maksić, A.; Bele, M.; Hodnik, N. Recent progress in the development of advanced support materials for electrocatalysis. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1304063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Wei, Z. Coating layer-free synthesis of sub-4 nm ordered intermetallic L10-PtCo catalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 27116–27123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tao, Z.; Xie, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Xiao, H.; Wang, L. Facial construction of defected NiO/TiO2 with Z-scheme charge transfer for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Catal. Today 2019, 335, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Climent, R.; Giménez, S.; García-Tecedor, M. The role of oxygen vacancies in water splitting photoanodes. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 5916–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, D.-N.; Gong, L.; Zhang, A.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.-J.; Mu, Y.; Yu, H.-Q. Defective titanium dioxide single crystals exposed by high-energy {001} facets for efficient oxygen reduction. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-Y.; Liu, X.-J.; Guo, R.-T.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.-S.; Pan, W.-G. Constructing Cu defect band within TiO2 and supporting NiOx nanoparticles for efficient CO2 photoreduction. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 4088–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Ni, M.; Cen, K.; Zhang, Y. Oxygen-vacancy-anchoring NixOy loading towards efficient hydrogen evolution via photo-thermal coupling reaction. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 61, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadarrama-Pérez, O.; Guadarrama-Pérez, V.H.; Bustos-Terrones, V.; Guillén-Garcés, R.A.; Treviño-Quintanilla, L.G.; Estrada-Arriaga, E.B.; Moeller-Chávez, G.E. Bioelectrochemical performance on constructed wetland-microbial fuel cells operated under diffuse and direct solar radiation using root exudates as endogenous substrate to feed an electroactive biofilm. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 507, 145116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S. Theoretical investigation on the Ni atom-pair supported by N-doped graphene for the oxygen reduction reaction. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2022, 1209, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Long, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Meng, H.; Jiang, C.; Dong, W.; Lu, N. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy applied to microbial fuel cells: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 973501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.M.; Shehata, A.G.; Al-Anazi, A.; Khairy, M.; Newair, E.F. A template-assisted method for synthesizing TiO2 nanoparticles and Ni/TiO2 nanocomposites for urea electrooxidation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 316, 129112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Dhanda, A.; Dubey, B.K.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Enhancing electrokinetics and desalination efficiency through catalysts and electrode modifications in microbial desalination cells. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Jin, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Li, P.; Luo, X.; Gong, W.; Xu, D.; Dewil, R. Catalytic membrane with dual-layer structure for ultrafast degradation of emerging contaminants in surface water treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, N.A.; Almasri, R.A.; Irfan, O.M. Cost-effective sewage-powered microbial fuel cells with nitrogen-doped cobalt carbon nanofiber cathodes and biomass-derived graphitized anodes. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 48, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Lin, C.; Gao, H.; Qiu, Z.; Pan, X. Capacitive bio–electrocatalyst Mxene@ CoMo–ZIF sulfide heterostructure for boosted biofilm electroactivity to enhance renewable energy conversion. Renew. Energy 2025, 243, 122545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmath, S.; Kwon, H.-J.; Peera, S.G.; Lee, T.G. Solid-state synthesis of cobalt/NCS electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction in dual chamber microbial fuel cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, Y. Progress on Platinum-Free Catalysts for Fuel Cells. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences, Pretoria, South Africa, 27–30 October 2025; p. 01022. [Google Scholar]

- Nisa, K.U.; da Silva Freitas, W.; D’Epifanio, A.; Mecheri, B. Design and optimization of critical-raw-material-free electrodes towards the performance enhancement of microbial fuel cells. Catalysts 2024, 14, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huya-Kouadio, J.; James, B. Fuel cell cost and performance analysis. In Proceedings of the Presentation at in 2023 Annual Merit Review and Peer Evaluation Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 5–8 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Ullah, A.; Ullah, I.; Zhang, S.; Song, G. Thermally grown oxide formation on Ni2Al3 aluminide coating: The effect of nanocrystalline nickel film on oxide scale adhesion. Vacuum 2022, 197, 110843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ullah, I.; Shah, S.; Aziz, T.; Zhang, S.; Song, G. Effect of Cr nanoparticle dispersions with various contents on the oxidation and phase transformation of alumina scale formation on Ni2Al3 coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 438, 128397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Dong, Z.; Peng, X. Accelerated phase transformation of thermally grown alumina on Ni2Al3: Effect of dispersion of hcp-oxides with various content and particle size and chemistry. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 394, 125861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Huang, Y.-C.; Dong, Z.-H.; Peng, X. Effect of Cr2O3 nanoparticle dispersions on oxidation kinetics and phase transformation of thermally grown alumina on a nickel aluminide coating. Corros. Sci. 2019, 150, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ullah, I.; Ullah, A.; Shah, S.; Zhang, S.; Song, G. The effect of grain refinement on the oxidation and phase transformation of alumina scale on Ni2Al3 coating. Intermetallics 2022, 146, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Rauf, A.; Ullah, S.; Jan, H.U.; Aziz, T.; Zhang, S.; Song, G. ZrO2-nanoparticle assisted phase transformation and oxidation kinetics of thermally grown alumina on nickel aluminide coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 470, 129852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznowicz, M.; Jędrzak, A.; Rębiś, T.; Jesionowski, T. Biomimetic magnetite/polydopamine/β-cyclodextrins nanocomposite for long-term glucose measurements. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 174, 108127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Peng, X.; Chen, X.-Q. TiO2 nanoparticles-assisted α-Al2O3 direct thermal growth on nickel aluminide intermetallics: Template effect of the oxide with the hexagonal oxygen sublattice. Corros. Sci. 2019, 153, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, H.; Ghasemi, M. Experimental validation of optimized performance of microbial fuel cell-based horned lizard algorithm and artificial intelligence. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 21519–21544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazani, M.R.C.; Ghasemi, M.; Asadi, H. Optimising the power regeneration and chemical oxygen demand removal in microbial fuel cell systems using integrated soft computing methods and multiple-objective optimisation. Renew. Energy 2025, 256, 124188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, T.T.; Kathmann, S.M.; Schenter, G.K.; Mundy, C.J. Toward a first-principles framework for predicting collective properties of electrolytes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2833–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Catalyst Material | Raw Material Cost (USD/g) | [Source] | Catalyst Loading (g/m2) | Max. Power Density (W/m2) | Calculated Cost Per Watt (USD/W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt (on Carbon) | USD 35.00 | [48] | 5.0 | 0.275 | USD 636.36 |

| Ni-TiO2 | USD 0.15 | [49] | 5.0 | 0.224 | USD 3.35 |

| Ni-Cr2O3 | USD 0.12 | [49] | 5.0 | 0.162 | USD 3.70 |

| Ni-Al2O3 | USD 0.08 | [49] | 5.0 | 0.134 | USD 2.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, A.; Rostami, K.; Sedighi, M.; Khan, S.; Ghasemi, M. A Comparative Electrochemical Study of Pt and Ni–Oxide Cathodes: Performance and Economic Viability for Scale-Up Microbial Fuel Cells. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121153

Khan A, Rostami K, Sedighi M, Khan S, Ghasemi M. A Comparative Electrochemical Study of Pt and Ni–Oxide Cathodes: Performance and Economic Viability for Scale-Up Microbial Fuel Cells. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121153

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Azim, Kimia Rostami, Mehdi Sedighi, Sulaiman Khan, and Mostafa Ghasemi. 2025. "A Comparative Electrochemical Study of Pt and Ni–Oxide Cathodes: Performance and Economic Viability for Scale-Up Microbial Fuel Cells" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121153

APA StyleKhan, A., Rostami, K., Sedighi, M., Khan, S., & Ghasemi, M. (2025). A Comparative Electrochemical Study of Pt and Ni–Oxide Cathodes: Performance and Economic Viability for Scale-Up Microbial Fuel Cells. Catalysts, 15(12), 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121153