Abstract

Furfural (FAL), an important biomass-derived platform molecule, plays a vital role in bridging biorefineries and the production of high-value chemicals through its selective hydrogenation to furfuryl alcohol (FOL). In this work, a series of Cu-based bimetallic catalysts (Cu5Nix/SiO2) were prepared by a simple impregnation method and exhibited outstanding catalytic performance for the hydrogenation of furfural under the mild conditions. When the loading of Ni was 2 wt%, the optimal catalytic activity was obtained at 150 °C and 1 MPa H2, achieving a furfural conversion of 97.3%. This catalyst also showed excellent stability, maintaining high activity and selectivity toward FOL after five consecutive reaction cycles. Structural characterizations using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Hydrogen temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed strong electronic interactions between Cu and Ni species. The introduction of Ni promoted the reduction of Ni2+ and improved the dispersion of Cu, which in turn increased the number of accessible active sites and facilitated the hydrogenation process. This synergistic effect between Cu and Ni provides an efficient and low-cost strategy for the selective hydrogenation of biomass-derived furfural to high-valued chemicals.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of the global population and the acceleration of industrialization, the global demand for energy continues to increase. Over the past century, carbon-based fossil fuels and fossil resources such as coal, oil and gas have served as the dominant sources of transportation fuel and chemical production, driving global economic growth [1,2]. However, the excessive consumption of these non-renewable resources has resulted in massive greenhouse gas emissions, causing severe environmental problems including the greenhouse effect, acid rain, and air pollution [3,4]. It is estimated that the average surface temperature of the Earth has increased by approximately 0.6 °C over the past 100 years due to fossil fuel combustion, and it is expected to rise by an additional 0.2 °C per decade in the coming decades. Furthermore, deforestation and land-use changes contribute to nearly 15% of global carbon emissions annually, amplifying the impact of climate.

Change by more than fourfold between 1980 and 2010 [5]. According to the United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs statement, global population growth is predicted to surge exponentially annually and will reach 9.7 billion in 2025 [6], and fossil fuels still accounted for over 84% of global energy consumption at their 2019 peak. Nowadays, as energy demand continues to grow, ensuring energy security while reducing carbon emissions has become a critical global challenge.

To address this issue, increasing attention has been directed toward the development of sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative energy sources. Renewable energy, including solar energy, wind energy, water energy, geothermal energy and biomass energy, offers the potential to reduce dependence on fossil fuels [7]. Among the many renewable energy sources, biomass has become a highly sought-after alternative energy source due to its short regeneration cycle, wide distribution of resources, and carbon neutrality [8,9]. Biomass resources, mainly in the form of lignocellulose, have an estimated annual global production exceeding 10 billion tons [10]. As a carbon-neutral energy source, bioenergy derived from biomass not only mitigates greenhouse gas emissions but also provides a sustainable pathway for energy transformation [11].

Furfural (C5H4O2, FAL), also known as 2-furaldehyde, is a representative platform molecule derived from lignocellulosic biomass and serves as a critical bridge between biomass feedstocks and multifunctional chemicals [12]. It is mainly sourced from agricultural wastes, such as corn cobs and rice husks, which are rich in cellulose and lignin. Through a specific hydrolysis process, the five-carbon sugars in these biomasses can be efficiently converted into furfural [13]. As of 2022, China’s annual furfural production reached approximately 320,000 tons [14]. Owing to the high reactivity of its aldehyde group and C=C bond, furfural can be transformed into a variety of high-value chemicals under different reaction conditions. Its downstream products re widely used in the chemical, energy, and materials industries. Through catalyst design and process optimization, highly selective conversion pathways can be developed to maximize its value utilization. Furfuryl alcohol (C5H6O2, FOL), also known as 2-furanmethanol, is the primary hydrogenation product of furfural and is typically produced industrially via catalytic hydrogenation in either the gas or liquid phase. Guillermo R. Bertolini et al. [15] investigated the gas-phase hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol over Cu-ZnO-Al catalysts prepared from layered double hydroxides. In recent years, research on furfural has mainly focused on improving production process efficiency, reducing production costs, and enhancing reaction selectivity. The hydrogenation of FAL to FOL has thus become a key reaction of both academic and industrial significance, contributing to the efficient utilization of biomass resources [16,17].

Copper-based catalysts have been extensively studied for the selective hydrogenation of furfural. However, their intrinsic hydrogenation activity is relatively weak, largely due to limited interaction with the carbonyl group and a restricted number of accessible active sites. Copper-based catalysts such as Cu/SiO2 [18,19], Cu/CeO2 [20,21], Cu/MgO and Cu/ZnO [22] have been widely employed in the hydrogenation of furfural to produce furfuryl alcohol. Although supported noble metals such as Pt, Pd, and Rh offer excellent dispersion and low activation energies [23,24,25], their high cost and scarcity hinder large-scale application. In contrast, non-precious metals such as Ni, Cu, and Co have demonstrated promising activity in heterogeneous hydrogenation at significantly lower costs [26,27]. In particular, Ni has attracted particular attention for its high activity, good selectivity, and economic advantages. Synergistic effects between two metals—such as ensemble, ligand, and geometric effects—can enhance structural and surface properties, increase active site availability, and improve resistance to deactivation [28]. Liao et al. [29] worked on the hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol and cyclopentanone with high efficiency and selectivity using Cu-Ni bimetallic catalysts. In addition, silicon dioxide (SiO2) is a widely used oxide support in heterogeneous catalysis due to its high specific surface area and execllent stability, providing more active sites for catalytic reactions [30]. Ravi Balaga et al. [31] worked on bimetallic Ni-Cux on m-SiO2 catalysts were synthesized via the alkaline hydrothermal method (in situ preparation) and evaluated for selective hydrogenation of FAL to CPO.

In this work, a series of bimetallic Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts were prepared via a wet impregnation method by introducing Ni as a promoter to Cu/SiO2, and applied in the selective hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol. The effect of Ni incorporation on catalytic performance was systematically investigated by evaluating FAL conversion and FOL selectivity under varied reaction conditions. Characterization results revealed that the introduction of Ni modified the electronic environment of Cu and altered the metal-support interaction, leading to a redistribution of active sites and an overall enhancement in catalytic performance. This study offered a feasible strategy to tailor the active sites of Cu-based catalysts and provided a theoretical basis for the design of efficient and cost-effective catalytic systems for C=O bond hydrogenation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure Characterization of Catalysts

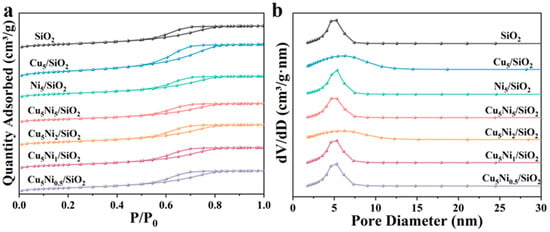

As shown in Figure 1, the physical properties of the Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst were investigated by N2 adsorption–desorption. All samples exhibited typical Type IV isotherms and H3 hysteresis loops, indicating that adsorption mainly occurred within the mesoporous region. The pore size distribution curves (Figure 1b) revealed that the pore diameters were mainly concentrated in the range of 2–10 nm, and no significant variation was observed among the samples. This result confirmed that Ni incorporation had a negligible effect on the mesoporous structure of the catalysts. The specific surface area (SBET) of Cu5Ni0.5/SiO2 was 434.3 m2/g (Table 1), which is slightly lower than that of the pristine SiO2 support (474.1 m2/g), This decrease indicated that Ni and Cu were successfully loaded onto the support surface. As the Ni loading increased, the specific surface area of the Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst first increases and then decreases, reaching a maximum value of 440.4 m2/g for Cu5Ni2/SiO2. The high specific surface area and abundant mesoporous structure of the Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst facilitated the anchoring of Ni and Cu on the support surface and the distribution of catalytic active sites.

Figure 1.

(a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and (b) pore size distribution diagrams for different catalysts.

Table 1.

Physical properties of SiO2 carriers and Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts.

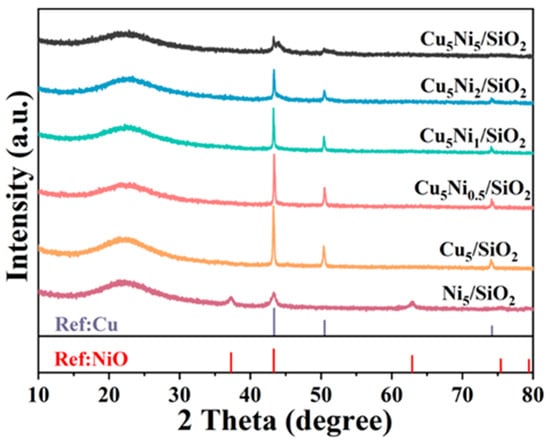

The XRD pattern of the reduced Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst is shown in Figure 2. A broad diffraction peak at 22.0° could be attributed to amorphous silica. The diffraction peaks located at 37.2°, 43.3°, and 62.9° corresponded to the (111), (200), and (220) crystal planes of NiO, respectively [32], indicating that Ni was not completely reduced at a reduction temperature of 250 °C and still existed in the form of metal oxides. Additionally, t characteristic peaks appearing at 43.3°, 50.4°, and 74.1° are attributed to the (111), (200), and (220) [33] crystal planes of metallic Cu, respectively [34]. As the Ni loading increased, the diffraction intensity of the Cu peaks gradually decreased, while the NiO peaks became less pronounced and eventually disappeared. This suggested that the introduction of Ni effectively enhanced the dispersion of Cu species, likely due to strong interactions between Ni and Cu [35]. Such interactions might lead to improved structural uniformity and better distribution of active metal sites, which could be beneficial for the subsequent hydrogenation reaction.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of different catalysts.

Ni as a promoter to Cu/SiO2 influenced the crystallite size of Cu. As shown in Table 2, With the Ni loading increasing from 0 to 5 wt%, the crystallite size initially increased and subsequently decreased. This suggested that Ni might promote the growth of Cu crystallites, whereas a higher Ni loading likely inhibited grain growth and refined the crystallites due to lattice strain induced by the formation of Cu-Ni alloys. Therefore, the crystallite structure of Cu could be effectively modulated by regulating the Ni loading.

Table 2.

Cu crystallite sizes of Cu5/SiO2 carriers and Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts.

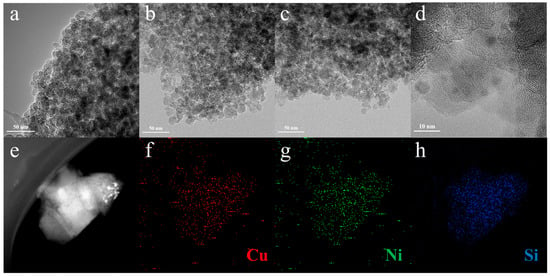

Figure 3 presents the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) images of the Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts, which were employed to investigate the morphology and distribution of Cu and Ni species on the catalyst surface. As illustrated in Figure 3a–c, the metal nanoparticles exhibited different degrees of dispersion depending on the Ni loading. In the case of Cu5Ni2/SiO2, metal particles were observed to be uniformly distributed on the support surface without noticeable agglomeration (Figure 3d). This result suggested that the introduction of Ni promoted the dispersion of active sites, which was conducive to improving the catalytic performance. However, when the Ni loading was further increased to 5 wt%, agglomeration of metal particles occurred on the catalyst surface, indicating that excessive Ni loading weakened the dispersion of active species. Moreover, High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images and the corresponding EDS mapping (Figure 3e–h) further confirmed that Cu, Ni, and Si elements were uniformly distributed throughout the support in the Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst, demonstrating good metal-support interaction and high dispersion of active components.

Figure 3.

TEM image of Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst: (a) Cu5Ni0.5/SiO2, (b) Cu5Ni1/SiO2 and (c) Cu5Ni2/SiO2; (d) HRTEM image of Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst, (e–h) HAADF-STEM and corresponding elemental mapping image of Cu5Ni2/SiO2.

2.2. Physicochemical Properties of the Catalysts

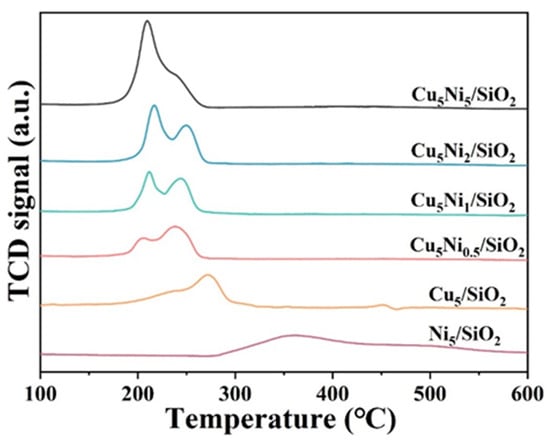

According to the H2-TPR results (Figure 4), the reduction peak of Ni5/SiO2 was mainly concentrated in the temperature range of 300–500 °C, corresponding to the reduction of NiO to metallic Ni0. The two reduction peaks appeared at approximately 225 and 273 °C, which were corresponded to the reduction peaks of Cu+ and Cu0, respectively. This indicated that part of Cu2+ was reduced to Cu+ and Cu0, consisting with the previous XRD results. For the Cu5Nix/SiO2 bimetallic catalyst, both Cu-related reduction peaks shifted toward lower temperatures, indicating the presence of a strong interaction between Cu and Ni species. Such an interaction facilitated the reduction of Ni2+ and simultaneously enhanced the dispersion of Cu particles on the support surface, thereby generating more accessible active sites for the hydrogenation reaction [36].

Figure 4.

H2-TPR curve of Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts.

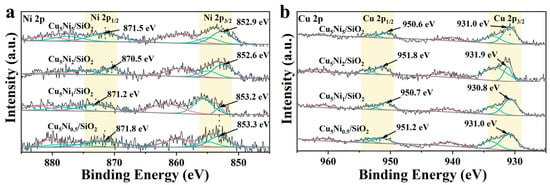

The surface chemical states of Cu and Ni were analyzed by XPS. All catalysts were pre-reduced in 10 vol% H2/Ar at 250 °C for 2 h and briefly exposed to air (<2 min) before analysis; thus, slight surface oxidation could occur.

As shown in Figure 5a, the main peaks at 852.6 eV (Ni 2p3/2) and 870.5 eV (Ni 2p1/2), together with the satellite peaks at 861.3 eV and 879.6 eV, correspond to Ni2+ (NiO), A weak shoulder at 853.4 eV corresponded to metallic Ni0. The coexistence of Ni0 and Ni2+ indicated that Ni was not completely reduced, consistent with XRD results. In the Cu 2p spectra (Figure 5b), main peaks at 931.9 eV (Cu 2p3/2) and 951.8 eV (Cu 2p1/2) without satellite features confirmed Cu0/Cu+ species. Compared with Cu5/SiO2, a slight positive shift (~0.8 eV) of Cu 2p3/2 and a minor negative shift of Ni 2p3/2 were observed for Cu5Ni2/SiO2, suggesting a mild electron transfer from Cu to Ni. Although the absolute shift was small and might be affected by noise, the consistent trend aligned with H2-TPR results, supporting strong Cu-Ni electronic interaction.

Figure 5.

(a) Ni 2p3/2 (Green: Ni0; Blue: Ni2+; Red: statellite peaks) and (b) Cu 2p3/2 (Green: Cu2+; Blue: Cu0/Cu+; Red: statellite peaks) XPS spectra of Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts.

Overall, the combined XRD and XPS analyses demonstrated partial Ni reduction and interfacial charge redistribution, which contributing to enhance hydrogenation performance of the Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst.

2.3. Testing the Selective Hydrogenation Performance of Cu5Nix/SiO2 Catalyst on Furfural

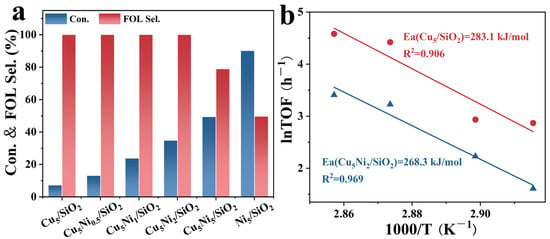

Figure 6 demonstrates the catalytic performance of Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts with various Ni loadings for the selective hydrogenation of FAL to FOL. As shown in Figure 6a, the incorporation of Ni significantly enhanced the FAL conversion. With the Ni loading increased, the FAL conversion rate first increased and then decreased. Specifically, Cu5Ni2/SiO2 exhibited the optimal catalytic behavior, achieving a FAL conversion of 34.7% and a FOL selectivity of 99.9%. When the Ni loading was further increased to 5 wt%, the FAL conversion reached its maximum value of 49.3%, but the selectivity toward FOL decreased markedly to 78.8%, indicating that excessive Ni content negatively affected the product distribution. Furthermore, the FAL hydrogenation reaction is generally considered a pseudo-first-order reaction [37]. Figure 6b shows the Arrhenius plot derived from the logarithm of the rate constant versus the inverse temperature for Cu5/SiO2 and Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalysts. According to the Arrhenius equation, the apparent activation energies for Cu5/SiO2 and Cu5Ni2/SiO2 are 283.1 kJ·mol−1 and 268.3 kJ·mol−1, respectively. This indicates that Cu5Ni2/SiO2 provides a low-energy barrier pathway, accelerating the initial reaction rate and thereby achieving a higher FAL conversion rate.

Figure 6.

(a) Ni loading effect of Reaction Pressure on Cu5Nix/SiO2 Catalysts, (b) Arrhenius plots for the hydrogenation of furfural using Cu5/SiO2 and Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalysts. Reaction conditions: (a) P(H2) = 1 MPa, t = 2 h, T = 90 °C.

The influence of different reaction conditions on the hydrogenation performance of the Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst was further investigated (Figure S2). For Cu5Ni2/SiO2, the FAL conversion gradually increased with the increasing reaction temperature and eventually reached complete conversion at 150 °C. However, the FOL selectivity slightly declined to 97.3%, which was attributed to the coupling between residual FAL and the generated FOL. When the reaction time was further extended to 2.5 h, it was found that the selectivity of FOL also decreased (73.2%). The effect of H2 pressure on the reaction performance was also investigated. It was worth noting that as the H2 pressure increased from 0.15 MPa to 1 MPa, the FAL conversion rate increased from 10.8% to 99.9%, indicated that the selective hydrogenation reaction of FAL on Cu5Ni2/SiO2 could be carried out under mild conditions, which was conducive to preventing further hydrogenation of FAL to form by-products. Meanwhile, H2 pressure also affect the selectivity of FOL. When H2 pressure increased to 2 MPa, the selectivity of FOL first increased and then decreased, which could be attributed to the coupling of FAL with part of FOL. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis confirmed that the reaction by-products were all FAL and FOL conjugates.

In summary, introducing an appropriate amount of Ni (2 wt%) and employing mild reaction conditions significantly improved the catalytic performance while minimizing side reactions. Although excessively high temperatures, long reaction times, and elevated H2 pressures further increased the FAL conversion, they also led to reduced FOL selectivity due to the formation of condensation by-products. Therefore, optimizing the reaction parameters was crucial for achieving high conversion and selectivity. Under the optimized conditions (150 °C, 1 MPa H2, 2 h), the Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst achieved an excellent FAL conversion of 99.7% and a FOL selectivity of 97.3%.

2.4. Stability Test of Cu5Ni2/SiO2 Catalyst

To investigate the durability of the Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst, its catalytic performance was examined through multiple cyclic hydrogenation reactions of FAL. The test reaction conditions were as follows: isopropanol was used as the solvent, the reaction temperature was 150 °C, H2 pressure of 1 MPa, 1 g of FAL, 0.3 g of catalyst, and the reaction time was 2 h. After each cycle, the solid catalyst was separated by centrifugation at 8000 rpm, washed five times with ethanol, and then dried overnight at 60 °C before being reused directly in the subsequent run. A total of five consecutive cycles were performed under identical conditions.

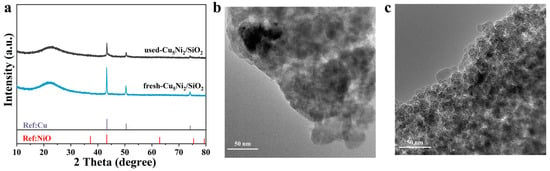

As shown in Figure S2d, both the FAL conversion and FOL selectivity exhibited only a slight decline after five reaction cycles, which might have been attributed to partial agglomeration of Cu and Ni metal particles on the catalyst surface. Importantly, the XRD patterns (Figure 7a) and TEM images (Figure 7b) of the used catalyst showed no significant structural changes compared to the fresh sample, indicating that the active phase remained stable during the reaction. These results demonstrated that the Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst not only achieved the highest FAL conversion and FOL selectivity among all tested samples but also exhibited excellent thermal and structural stability under repeated reaction cycles.

Figure 7.

The (a) XRD; (b,c) TEM images of fresh and used Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst.

2.5. Mechanism of FAL Hydrogenation on Catalysts

The reaction mechanism was further explored to clarify the origin of the enhanced activity. Figure 6b shows the Arrhenius plots for the Cu5/SiO2 and Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalysts. According to the Arrhenius plots, the apparent activation energies corresponding to Cu5/SiO2 and Cu5Ni2/SiO2 were 283.1 kJ·mol−1 and 268.3 kJ·mol−1, respectively. The lower energy barrier observed for Cu5Ni2/SiO2 suggested that the incorporation of Ni provides a more favorable reaction pathway, thereby accelerating the initial hydrogenation rate and achieving a higher FAL conversion.

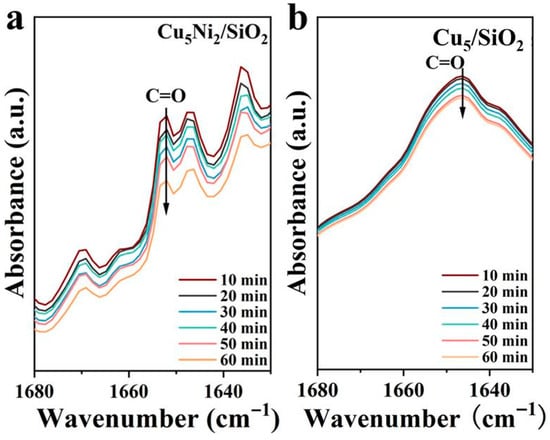

In addition, in order to further investigate the activation behavior of FAL on the catalyst surface, in situ FT-IR spectroscopy was used to gain a deeper understanding of the hydrogenation process of C=O on FAL. As shown in Figure 8 and Figure S3, two overlapping bands appeared in the 1640–1660 cm−1 region. The main peak at 1653 cm−1 was assigned to the C=O stretching of adsorbed furfural on Cu0/Cu+ sites, and the weaker one at 1642 cm−1 to hydrogen-bonded or Ni-O-coordinated C=O species. With increasing Ni loading, these peaks shifted and changed in intensity, reflecting variations in adsorption strength. Notably, Cu5Ni2/SiO2 showed a faster decrease than other catalysts. This clearly demonstrated its superior ability to activate and hydrogenate the C=O bond in FAL, which was consistent with the catalytic performance trends.

Figure 8.

In situ FT-IR spectrum of FAL hydrogenation at 90 °C using (a) Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst and (b) Cu5/SiO2.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

Fumed silica (SiO2, specific surface area of 480 m2/g, Aladdin, Shanghai, China) was used as a carrier. Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, ≥98%, SinoPharm, Shanghai, China) and copper nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, 99%, Macklin, Shanghai, China) were used as active metal precursors. All reagents can be used without further purification.

3.2. Materials Synthesis

A series of Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalysts with varying Ni loadings were prepared via an initial wet impregnation method. Briefly, a certain amount of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (5 wt% Cu) and different amounts of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O mixed solution was used to impregnate SiO2,. Subsequently, all samples were dried overnight at 80 °C. Then, the catalyst precursor was calcined in air at 400 °C for 2 h and reduced at 250 °C for 2 h in a 10 vol% H2/Ar atmosphere. The catalyst obtained was named Cu5Nix/SiO2 (x represents the load capacity of Ni, x = 0.5, 1, 2, 5 wt%).

For comparison, monometallic Cu5/SiO2 catalysts and Ni5/SiO2 catalysts with the same Cu loading were also prepared using the same procedure.

3.3. Catalyst Characterization

The surface area and pore structure of the catalyst were characterized by nitrogen physisorption at −196 °C using a Micromeritics ASAP 2420 analyzer (Micromeritice, Norcross, GA, USA). Before the measurement, the samples were degassed at 150 °C for 6 h. The specific surface area was calculated by the BET model, the pore size distribution and pore volume analyzed by the BJH model.

The actual metal loadings were determined by inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using a Shimadzu ICPE-9820 instrument (Micromeritice, Norcross, GA, USA), in order to evaluate the influence of different preparation methods on metal content and to further investigate the correlation between metal loading and catalytic performance.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using a SmartLab SE diffractometer (Rigaku, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å), operated at 40 kV and 15 mA. Data were collected over a 2θ range of 10–90° with a step size of 0.1°/s. Cu crystallite size determined from XRD measurement. The crystallite size of Cu can be determined through XRD measurements. The calculation was performed according to the Scherrer equation:

D: the crystallite size, k: the shape factor, λ: the X-ray wavelength, β: the corrected full width at half maximum of the diffraction peak expressed in radians, θ: the Bragg angle measured in radians.

The morphology and particle distribution of the catalysts were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a Tecnai G20 (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operated at 200 kV. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images were acquired on a JEOL JEM-2100F (Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) to further investigate the dispersion and distribution of metal species.

Hydrogen temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) was carried out using a Quantachrome Autosorb-IQ analyzer (Boynton Beach, FL, USA) to evaluate the redox behavior and surface metal dispersion of the catalysts.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on an AXIS SUPRA spectrometer using Al Kα radiation (hν = 1486.6 eV). The binding energies were calibrated using the C 1s peak at 284.8 eV as a reference. These measurements provided insights into the surface chemical states and electronic interactions between Cu and Ni species.

In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (in situ FT-IR) was conducted on the prepared catalysts with an INVENIO S Fourier infrared spectrometer from Bruker (Billerica, MA, USA), Germany. Firstly, catalysts at different reduction temperatures were reduced with 10 vol% H2/Ar (30 mL/min) for 1 h. After the temperature was lowered to 30 °C, the background spectra were collected. Furfural was then introduced into the cuvette with a bubbler using N2 (10 mL/min) as the carrier gas. Infrared spectra were collected every 10 min for 1 h of adsorption. The spectra were collected when the adsorption was stabilized. Subsequently, N2 was introduced to elevate the temperature to 90 °C, and the desorption stability spectra were recorded. Upon completion of the desorption process, 10 vol% H2/Ar mixture (30 mL/min) was introduced for in situ hydrogenation. Spectra were then collected every 10 min over for 1 h.

3.4. Catalytic Performance Test

All reactions described in this paper were conducted in a 100 mL stainless steel high-pressure reactor with liquid phase automatic sampling (YZQR-100, ShanghaiYanzheng, Shanghai, China). First, purge three times with N2 to remove air. Subsequently, add 0.3 g of catalyst, 1 g of FAL, and 30 mL of isopropanol, and heat the reactor to the set reaction temperature at a stirring speed of 800 rpm/min. Next, H2 was introduced at a certain pressure to carry out the furfural hydrogenation reaction. After 2 h of reaction, sample analysis was performed using an Agilent 8890-5977B gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an SH-RXI-5SIL capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm) and a flame ionization detector (FID). FAL conversion rate and FOL selectivity yield were calculated using the external standard method according to Equations (2) and (3), respectively.

Because H2 is significantly in excess during the reaction process, FAL hydrogenation to produce FOL can be regarded as a pseudo-first-order kinetic reaction. The following empirical formula can be used to study chemical kinetics:

where k represents the empirical kinetic constant, Ea represents the apparent activation energy, T represents the temperature at which the reaction takes place, R represents the molar gas constant, and A represents the pre-exponential factor.

In the cyclic experiment, the solid catalyst after the reaction was centrifuged at 8000 rpm and washed five times with ethanol. After drying overnight at 60 °C, the resulting catalyst was directly used in the subsequent reaction.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the influence of Ni incorporation on the catalytic performance of the bimetallic Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst in the selective hydrogenation of FAL to FOL was systematically investigated. Under optimized conditions (150 °C, 1 MPa H2, 2 h), the FOL yield reached 99.3%, demonstrating the excellent activity of the Cu5Ni2/SiO2 catalyst. The superior performance originated from the strong synergistic interaction between Cu and Ni, in which Cu facilitated the reduction of Ni2+, while Ni enhanced the dispersion of Cu species, thereby increasing the number of accessible active sites. Moreover, the incorporation of Ni effectively lowered the reaction energy barrier and promoted the activation of the C=O bond, which accelerated the overall hydrogenation process. These results highlighted the potential of rational bimetallic design to achieve both high catalytic efficiency and thermal stability. This study not only provided fundamental insights into the structure–activity relationship of Cu–Ni catalysts but also offered a promising and sustainable strategy for developing efficient catalysts for the selective hydrogenation of biomass-derived platform molecules.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121151/s1, Figure S1: (a) TEM image of Cu5Ni5/SiO2; HRTEM image of Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst: (b) Cu5Ni0.5/SiO2, (c) Cu5Ni1/SiO2 and (d) Cu5Ni5/SiO2; HAADF-STEM and corresponding elemental mapping image of Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst: (e–h) Cu5Ni0.5/SiO2, (i–l) Cu5Ni1/SiO2 and (m–p) Cu5Ni5/SiO2; Figure S2: (a) Response Time (b) Reaction Temperature (c) Reaction Pressure effect of Reaction Pressure on Cu5Nix/SiO2 Catalysts; (d) Evaluation of the Cycling Performance of Cu5Ni2/SiO2 Catalysts; (e) Evaluation of the Cycling Performance of Cu5/SiO2 Catalysts; Figure S3: in situ FT-IR spectrum of FAL hydrogenation at 90 °C using Cu5Nix/SiO2 catalyst.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G., J.W., Z.L., S.L. and Q.L.; methodology, Y.G. and J.W.; validation, Y.G. and J.W.; investigation, J.W.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Q.L. and S L; visualization, Y.G.; supervision, Z.L. and Q.L.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the School of Chemistry and the State Key Laboratory of Green Coal Resources Development of Zhengzhou University for providing the experimental platform and technical support. In addition, we thank our laboratory colleagues for their help in experimental design and data analysis, and the reviewers for their valuable comments on this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, M.; Sun, Y.; Han, B. Green carbon science: Efficient carbon resource processing, utilization, and recycling towards carbon neutrality. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202112835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yang, C.; Sun, P.; Gao, G.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Li, F. Synergistic catalysis for promoting ring-opening hydrogenation of biomass-derived cyclic oxygenates. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 5170–5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Putten, R.-J.; Van Der Waal, J.C.; De Jong, E.; Rasrendra, C.B.; Heeres, H.J.; de Vries, J.G. Hydroxymethylfurfural, a versatile platform chemical made from renewable resources. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1499–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, J.B.; Anastas, P.T.; Erythropel, H.C.; Leitner, W. Designing for a green chemistry future. Science 2020, 367, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, G.J.; Krishnan, A.U. Quantifying environmental performance of biomass energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segge, S.; Mauerhofer, V. Progress in local climate change adaptation against sea level rise: A comparison of management planning between 2013 and 2022 of Swedish municipalities. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Renewable energy and climate change. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huber, G.W. Catalytic oxidation of carbohydrates into organic acids and furan chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1351–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniza, R.; Chen, W.-H.; Petrissans, M.; Petrissans, A. Chemical bioexergy analysis in thermochemically converted biomass fuels: An introductory review. Fuel 2026, 405, 136652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.; Schröder, U. Hydrothermal production of furfural from xylose and xylan as model compounds for hemicelluloses. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 22253–22260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Aniza, R. Specific chemical bioexergy and microwave-assisted torrefaction optimization via statistical and artificial intelligence approaches. Fuel 2023, 333, 126524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, X.; Qiu, S.; Meng, Q.; Wang, T. Ethanol-induced transformation of furfural into 1, 4-pentanediol over a Cu/SiO2 catalyst with enhanced metal–acid sites by copper phyllosilicate. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakzeski, J.; Bruijnincx, P.C.; Jongerius, A.L.; Weckhuysen, B.M. The catalytic valorization of lignin for the production of renewable chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3552–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Shen, X.; Chen, B.; Liu, H.; Han, B. Selective hydrogenation of aromatic furfurals into aliphatic tetrahydrofurfural derivatives. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 4937–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, G.R.; Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A.; Maireles-Torres, P. Gas-phase hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol over Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 catalysts prepared from layered double hydroxides. Catalysts 2020, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lin, J.; Wan, S.; Wang, S. Selective amination of furfuryl alcohol to furfurylamine over nickel catalysts promoted by alumina encapsulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slak, J.; Pomeroy, B.; Kostyniuk, A.; Grilc, M.; Likozar, B. A review of bio-refining process intensification in catalytic conversion reactions, separations and purifications of hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) and furfural. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Tan, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhu, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, W.; Ding, Y. Hydrogenation of dimethyl oxalate to ethanol over Mo-doped Cu/SiO2 catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Ma, X.; Yan, P.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Z.C. Catalytic furfural hydrogenation to furfuryl alcohol over Cu/SiO2 catalysts: A comparative study of the preparation methods. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 193, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Liu, S.; Steffensen, A.K.; Schill, L.; Kastlunger, G.; Riisager, A. On the role of Cu+ and CuNi alloy phases in mesoporous CuNi catalyst for furfural hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 8437–8444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Lin, H.; He, P.; Yuan, Y. Effect of boric oxide doping on the stability and activity of a Cu–SiO2 catalyst for vapor-phase hydrogenation of dimethyl oxalate to ethylene glycol. J. Catal. 2011, 277, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y. Cr-free Cu-catalysts for the selective hydrogenation of biomass-derived furfural to 2-methylfuran: The synergistic effect of metal and acid sites. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 398, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hou, Z. Catalytic transfer hydrogenation of the C=O bond in unsaturated aldehydes over Pt nanoparticles embedded in porous UiO-66 nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 12260–12268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Chen, X.; Bai, Z.; Liang, C. Noble metal silicides catalysts with high stability for hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophenes. Catal. Today 2021, 377, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Song, Y.; Mei, J.; Wang, A.; Li, D.; Gao, S.; Jin, L.; Shang, H.; Duan, A.; Wang, X. Highly Dispersed Pt Catalysts on Hierarchically Mesoporous Organosilica@Silica Nanoparticles with a Core–Shell Structure for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrogenation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 10761–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolek, W.; Nanthasanti, N.; Pongthawornsakun, B.; Praserthdam, P.; Panpranot, J. Effects of TiO2 structure and Co addition as a second metal on Ru-based catalysts supported on TiO2 for selective hydrogenation of furfural to FA. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, N.; Chen, B.H. PtMx/SBA-15 (M= Co, Cu, Ni and Zn) bimetallic catalysts for crotonaldehyde selective hydrogenation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 294, 127003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Miyawaki, K.; Yamashita, H. Ru and Ru–Ni nanoparticles on TiO2 support as extremely active catalysts for hydrogen production from ammonia–borane. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3128–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, R.; Luo, H.; Lv, Y.; Liu, P. Highly efficient and selective hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol and cyclopentanone over Cu-Ni bimetallic Catalysts: The crucial role of CuNi alloys and Cu+ species. J. Catal. 2024, 436, 115603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soled, S. Silica-supported catalysts get a new breath of life. Science 2015, 350, 1171–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaga, R.; Balla, P.; Zhang, X.; Ramineni, K.; Du, H.; Lingalwar, S.; Perupogu, V.; Zhang, Z.C. Enhanced cyclopentanone yield from furfural hydrogenation: Promotional effect of surface silanols on Ni-Cu/m-silica catalyst. Catalysts 2023, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Y.R.; Perez-Lopez, O.W. Carbon dioxide methanation over Ni-Cu/SiO2 catalysts. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 203, 112214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wang, L.; Walle, M.D.; Mustapha, A.; Liu, Y.-N. An alloy chemistry strategy to tailoring the d-band center of Ni by Cu for efficient and selective catalytic hydrogenation of furfural. J. Catal. 2020, 383, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yue, Y.; Wang, T.; Yuan, P. Hierarchical flower-like NiCu/SiO2 bimetallic catalysts with enhanced catalytic activity and stability for petroleum resin hydrogenation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 5432–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-Y.; Wang, S.-R.; Zhu, L.-J.; Ge, X.-L.; Li, X.-B.; Luo, Z.-Y. The influence of copper particle dispersion in Cu/SiO2 catalysts on the hydrogenation synthesis of ethylene glycol. Catal. Lett. 2010, 135, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, E.T.; Oemar, U.; Tan, X.; Du, Y.; Borgna, A.; Hidajat, K.; Kawi, S. Bimetallic Ni–Cu catalyst supported on CeO2 for high-temperature water–gas shift reaction: Methane suppression via enhanced CO adsorption. J. Catal. 2014, 314, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Remón, J.; Jiang, Z.; Yao, L.; Hu, C. Selective hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol in water under mild conditions over a hydrotalcite-derived Pt-based catalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 309, 121260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).