Enhancement of Cellulase Production by Penicillium oxalicum Using Traditional Chinese Medicine Residue and Its Application in Flavonoid Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

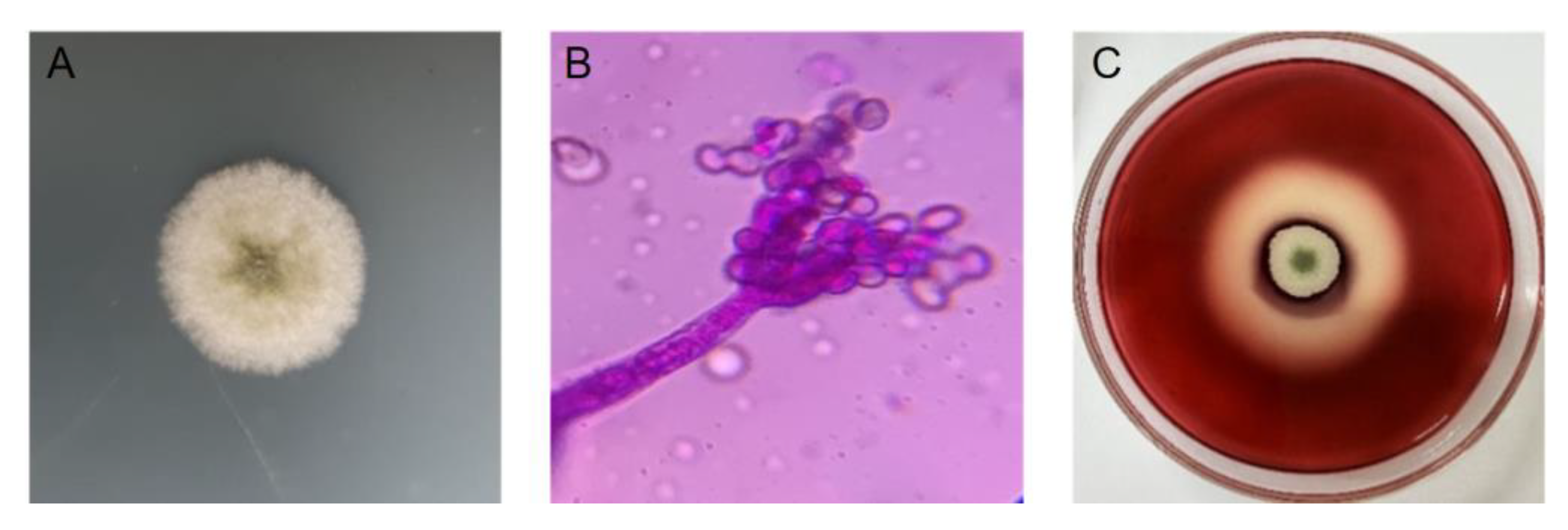

2.1. Results of Isolation and Identification of Cellulase-Producing Fungi

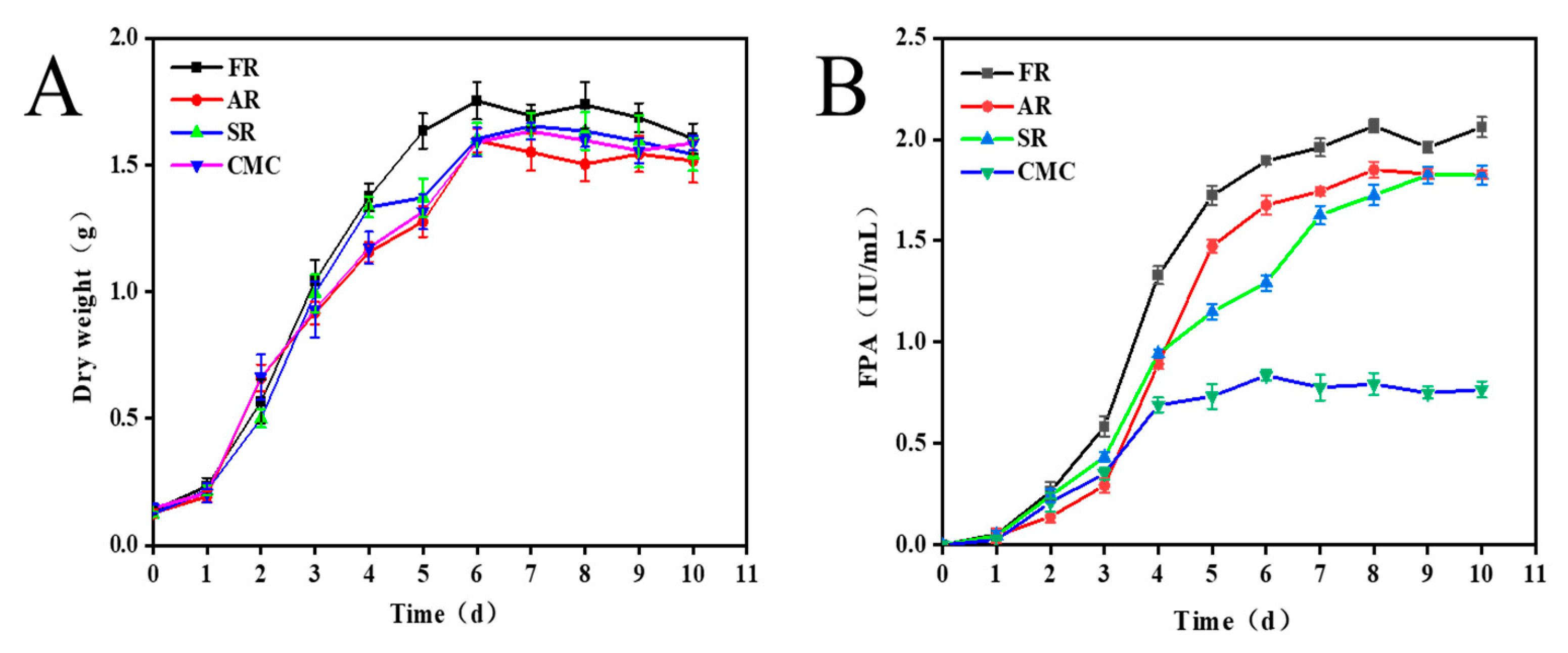

2.2. Fungi Growth and Enzyme Production Under Three Kinds of Residues

2.3. Structural Characterization of TCMRs Before and After Enzymatic Hydrolysis

2.4. Results of Screening and Optimization

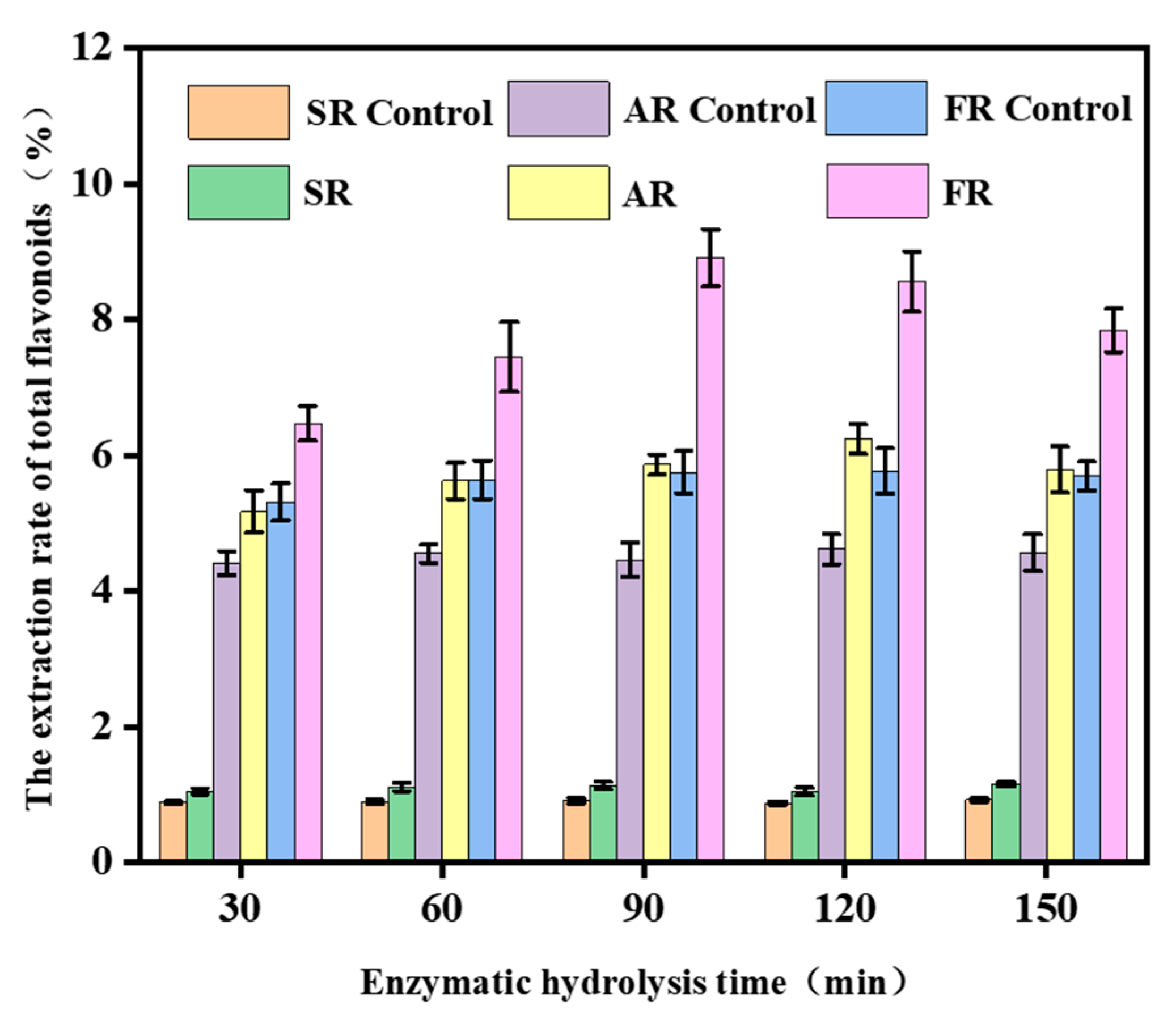

2.5. Extraction of Total Flavonoids from TCMRs by Crude Cellulase

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation and Identification of Cellulase-Producing Fungi

4.2. Acquisition and Preparation of TCMRs

4.3. Determination of Cellulase Activity

4.4. Screening and Optimization

4.5. Structural Characterization of TCMRs

4.6. Extraction of Total Flavonoids from TCMRs

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, G.; Taggar, M.S.; Kalia, A. Cellulase-immobilized chitosan-coated magnetic nanoparticles for saccharification of lignocellulosic biomass. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 111627–111647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Rojas, I.; Moreno-Sarmiento, N.; Montoya, D. Mechanisms and regulation of the enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose in filamentous fungi: Classic cases and new models. Iberoam. J. Mycol. 2015, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Wu, F.; Wu, X.; Bao, T.; Jie, Y.; Gao, L. Fungal systems for lignocellulose deconstruction: From enzymatic mechanisms to hydrolysis optimization. Gcb Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, E.M. From first generation biofuels to advanced solar biofuels. Ambio 2016, 45, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Gupta, R.; Jain, K.K.; Gautam, S.; Kuhad, R.C. Cellulases: Application in wine and brewery industry. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoop Kumar, V.; Suresh Chandra Kurup, R.; Snishamol, C.; Nagendra Prabhu, G. Role of cellulases in food, feed, and beverage industries. In Green Bio-Processes: Enzymes in Industrial Food Processing; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Amaresan, N. Mass Multiplication, Production Cost Analysis, and Marketing of Cellulase. In Industrial Microbiology Based Entrepreneurship: Making Money from Microbes; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, S.; Aneesh, E.M.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Pandey, A.; Gnansounou, E. Enzyme catalysis: A workforce to productivity of textile industry. High Value Ferment. Prod. Hum. Welf. 2019, 2, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Iqbal, H.; Dhama, K. Enzyme-based biodegradation of hazardous pollutants-an overview. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 2017, 5, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangrila Sadhu, S.S.; Maiti, T.K. Cellulase production by bacteria: A review. Microbiol. Res. J. Int. 2013, 3, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhad, R.C.; Gupta, R.; Singh, A. Microbial cellulases and their industrial applications. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 280696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Srivastava, M.; Mishra, P.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Molina, G.; Rodriguez-Couto, S.; Manikanta, A.; Ramteke, P.W. Applications of fungal cellulases in biofuel production: Advances and limitations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2379–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.J.; Odaneth, A.A. Industrial application of cellulases. In Current Status and Future Scope of Microbial Cellulases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.C.; Sethi, B.K.; Mishra, R.R.; Dutta, S.K.; Thatoi, H.N. Microbial cellulases–Diversity & biotechnology with reference to mangrove environment: A review. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2017, 15, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Valkonen, M.; Jackson, R.E.; Palmer, J.M.; Bhalla, A.; Nikolaev, I.; Saloheimo, M. Modification of transcriptional factor ACE3 enhances protein production in Trichoderma reesei in the absence of cellulase gene inducer. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, L.R.; Xia, L.M. High-level production of a fungal β-glucosidase with application potentials in the cost-effective production of Trichoderma reesei cellulase. Process Biochem. 2018, 70, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.T.; Wages, J.M. New-to-nature sophorose analog: A potent inducer for gene expression in Trichoderma reesei. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2016, 85, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Peng, N.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Induction of cellulase production in Trichoderma reesei by a glucose–sophorose mixture as an inducer prepared using stevioside. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 17392–17400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, V.; Astolfi, A.L.; Mazutti, M.A.; Rigo, E.; Di Luccio, M.; Camargo, A.F.; Dalastra, C.; Kubeneck, S.; Fongaro, G.; Treichel, H. Cellulolytic enzyme production from agricultural residues for biofuel purpose on circular economy approach. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.G.; Li, Q.M.; Thakur, K.; Faisal, S.; Wei, Z.J. A possible water-soluble inducer for synthesis of cellulase in Aspergillus niger. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 226, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, G.S.; Brar, S.K.; Kaur, S.; Metahni, S.; M’hamdi, N. Lactoserum as a moistening medium and crude inducer for fungal cellulase and hemicellulase induction through solid-state fermentation of apple pomace. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 41, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratale, G.D.; Kshirsagar, S.D.; Sampange, V.T.; Saratale, R.G.; Oh, S.E.; Govindwar, S.P.; Oh, M.K. Cellulolytic enzymes production by utilizing agricultural wastes under solid state fermentation and its application for biohydrogen production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 2801–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, S.K.; Mahmud, S.; Paul, G.K.; Jabin, T.; Naher, K.; Uddin, M.S.; Zaman, S.; Saleh, M.A. Fermentation optimization of cellulase production from sugarcane bagasse by Bacillus pseudomycoides and molecular modeling study of cellulase. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, F.; Peng, L.-C.; Zhang, D.-B.; Kondo, A.; Bai, F.-W. Optimization of cellulolytic enzyme components through engineering Trichoderma reesei and on-site fermentation using the soluble inducer for cellulosic ethanol production from corn stover. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Yun, C.; Yang, B.; Duan, J.; Chen, T.; Liu, L.; Li, B.; Guo, S.; Zhang, S. Comprehensive reutilization of Glycyrrhiza uralensis residue by extrusion-biological pretreatment for coproduction of flavonoids, cellulase, and ethanol. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 131002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreya, N.B.; Sharma, A.K. Cost—effective cellulase production, improvement strategies, and future challenges. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44, 13623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Z.X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Gao, J. Treatment and bioresources utilization of traditional Chinese medicinal herb residues: Recent technological advances and industrial prospect. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. Development of a compound microbial agent beneficial to the composting of Chinese medicinal herbal residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 330, 124948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Yin, X.-L.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, X.-H.; Yuan, H.-Y.; Xie, J.-J.; Wu, C.-Z. Characteristics of NOx precursors and their formation mechanism during pyrolysis of herb residues. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2017, 45, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandpe, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Paliya, S.; Pratap, V.; Hussain, A.; Kumar, S. Life-cycle assessment approach for municipal solid waste management system of Delhi city. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yang, R.; Ma, F.; Jiang, W.; Han, C. Recycling utilization of Chinese medicine herbal residues resources: Systematic evaluation on industrializable treatment modes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 32153–32167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, D.; Manjunatha, G.S.; Singh, D.; Periyaswami, L.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Estimation of spontaneous waste ignition time for prevention and control of landfill fire. Waste Manag. 2022, 139, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelino, S.; Gaspar, P.D.; Paco, A. Sustainable waste management in the production of medicinal and aromatic plants—A systematic review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Fu, Z.; Lin, K.; Wang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Han, L.; Yu, H.; Tian, F. Green synthesis of multifunctional fluorescent carbon dots from mulberry leaves (Morus alba L.) residues for simultaneous intracellular imaging and drug delivery. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2020, 22, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Sharma, A.; Gupta, G.; Mansoor, S.; Jan, S.; Kaur, B.; Paray, B.A.; Ahmad, A. Response surface optimization of cellulase production from Aneurinibacillus aneurinilyticus BKT-9: An isolate of urban Himalayan freshwater. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 2333–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Li, C.L. Comprehensive utilization of Chinese medicine residues for industry and environment protection: Turning waste into treasure. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jiang, J.G. Application of enzymatic method in the extraction and transformation of natural botanical active ingredients. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 169, 923–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Kumar, B.; Agrawal, K.; Verma, P. Current perspective on production and applications of microbial cellulases: A review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, M.; Sharma, D.; Barrow, C.J. Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactives from plants. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 30, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França Passos, D.; Pereira, N., Jr.; de Castro, A.M. A comparative review of recent advances in cellulases production by Aspergillus, Penicillium and Trichoderma strains and their use for lignocellulose deconstruction. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 14, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.-P.; Meng, J.; Gao, Y.-F.; He, X.-M.; Hu, X.-M. Identification of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms and determination of their phosphate-solubilizing activity and growth-promoting capability. BioResources 2020, 15, 2560–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnav, N.; Singh, A.; Adsul, M.; Pooja, D.; Kaur, S.S.; Anshu, M.; Kumar, P.S.; Rani, S.R. Penicillium: The next emerging champion for cellulase production. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 2, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, J.I.; Presley, S.D.; Rajabathar, J.R.; Sangeetha, V.; Babu, V.; Rajkumar, M.; Kamath, M.S. Analyze and assess the spectral, DFT, and medicinal characteristics through targeted pharmacological investigation of 2-(3-(5-(4-chlorophenyl) furan-2-yl) acryloyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-naphthalen-1-one (CHFADN). J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321, 139659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, S.; Moon, H.C.; Seo, H.; Kim, J.Y.; Hong, S.-P.; Lee, B.S.; Kang, E.; Lee, J.; Ryu, D.H.; et al. Antimicrobial spray nanocoating of supramolecular Fe(III)-tannic acid metal-organic coordination complex: Applications to shoe insoles and fruits. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, V.V.; Zothanpuia; Lalthafala; Ramesh, N.; Singh, B.P. Microorganisms as an efficient tool for cellulase production: Availability, diversity, and efficiency. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 45, p. 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Han, S.Y.; Hsieh, Y.L. Controlled defibrillation of rice straw cellulose and self-assembly of cellulose nanofibrils into highly crystalline fibrous materials. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 12366–12375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasekara, S.; Ratnayake, R. Microbial cellulases: An overview and applications. In Cellulose; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; Volume 22, p. 84531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S. Screening of Enzyme Producing Resistance Strain from Chinese Medicine Residues Such as Salviae Militorrhizae and Its Resource Utilization. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Moholkar, V.S.; Goyal, A. Optimization of carboxymethyl cellulase production from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SS35. 3 Biotech 2013, 4, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Bibi, A. Fungal cellulase; production and applications: Minireview. Int. J. Health Life Sci. 2018, 4, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensels, J.; Snoek, T.; Meersman, E.; Nicolino, M.P.; Voordeckers, K.; Verstrepen, K.J. Improving industrial yeast strains: Exploiting natural and artificial diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 947–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, A.; Aggarwal, N.K.; Yadav, A. Cost-effective cellulase production using Parthenium hysterophorus biomass as an unconventional lignocellulosic substrate. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Ma, L.; Li, C.; Jia, W.; Li, D.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S. Trpac1, a pH response transcription regulator, is involved in cellulase gene expression in Trichoderma reesei. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2014, 67, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, M.; Mushtaq, Q.; Tabssum, F.; Shakir, H.A.; Qazi, J.I. Carboxymethyl cellulase production optimization from newly isolated thermophilic Bacillus subtilis K-18 for saccharification using response surface methodology. AMB Express 2017, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotkar, P.; Tumane, P.M.; Wasnik, D.D. Bioconversion of waste paper into bio-ethanol by co-culture of fungi isolated from lignocellulosic waste. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2016, 4, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, W.A.; Khan, H.M.; Javed, S. Bioprocess Optimization for Enhanced Production of Bacterial Cellulase and Hydrolysis of Sugarcane Bagasse. Bioenergy Res. 2022, 15, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-González, M.L.; Sepúlveda, L.; Verma, D.K.; Luna-García, H.A.; Rodríguez-Durán, L.V.; Ilina, A.; Aguilar, C.N. Conventional and emerging extraction processes of flavonoids. Processes 2020, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhou, X.; Si, J.; Gong, X.; Wang, S. Studies on cellulase-ultrasonic assisted extraction technology for flavonoids from Illicium verum residues. Chem. Cent. J. 2016, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Li, W.; Deng, Y.; Wang, X.; Tang, H.; Zhao, L.; Yan, G. Optimization of Cellulase-Assisted Extraction of Total Flavonoids from Equisetum via Response Surface Methodology Based on Antioxidant Activity. Processes 2023, 11, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chang, S.; Xiao, P.; Qiu, S.; Ye, Y.; Li, L.; Yan, H.; Guo, S.; Duan, J. Enzymatic in situ saccharification of herbal extraction residue by a medicinal herbal-tolerant cellulase. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 287, 121417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Qin, F.X.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Jia, Y.S. Study on technology of extracting total flavonoids from seed of wild jujube by cellulase method. Foods Oils 2018, 31, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, T.; Lin, C.; Xiong, H.; Bai, Z.; Wu, H.; Cao, F.; Wei, P. Determination of Lignocellulosic Components in Traditional Chinese Herb Residues and Its Sugar-Producing Application. Waste Biomass Valor. 2023, 14, 1891–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Du, G.; Li, X.; Qin, X.; Du, Y. Extraction, characterization, antitumor and immunological activities of hemicellulose polysaccharide from Astragalus radix herb residue. Molecules 2019, 24, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, T.K. Measurement of cellulase activities. Pure Appl. Chem. 1987, 59, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaja, K.; Shobha Rani, R.H. Design of experiments: Concept and applications of Plackett Burman design. Clin. Res. Regul. Aff. 2007, 24, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarina, Z.; Tan, S.Y. Determination of flavonoids in Citrus grandis (Pomelo) peels and their inhibition activity on lipid peroxidation in fish tissue. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 313. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285866489 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

| Types | Weight Loss Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| SR | 9.55 ± 2.59 |

| AR | 14.38 ± 1.76 |

| FR | 22.67 ± 4.33 |

| std | A: FR Concentration (g/L) | B: Temperature (°C) | C: pH | Y: Filter Paper Activity (IU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22.84 | 32.44 | 5.8 | 1.46846 |

| 2 | 26.84 | 32.44 | 5.8 | 1.72069 |

| 3 | 22.84 | 36.44 | 5.8 | 1.47085 |

| 4 | 26.84 | 36.44 | 5.8 | 1.68722 |

| 5 | 22.84 | 32.44 | 6.6 | 1.12537 |

| 6 | 26.84 | 32.44 | 6.6 | 1.95021 |

| 7 | 22.84 | 36.44 | 6.6 | 1.56409 |

| 8 | 26.84 | 36.44 | 6.6 | 1.98368 |

| 9 | 21.7907 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 1.01181 |

| 10 | 27.8893 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 1.75177 |

| 11 | 24.84 | 31.3907 | 6.2 | 1.5629 |

| 12 | 24.84 | 37.4893 | 6.2 | 1.57126 |

| 13 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 5.59014 | 2.17017 |

| 14 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 6.80986 | 1.57485 |

| 15 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 2.11518 |

| 16 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 2.41643 |

| 17 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 2.61845 |

| 18 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 2.75593 |

| 19 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 2.55868 |

| 20 | 24.84 | 34.44 | 6.2 | 2.53836 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 4.18 | 9 | 0.4639 | 7.70 | 0.0018 | significant |

| A-FR concentration | 0.6382 | 1 | 0.6382 | 10.60 | 0.0086 | |

| B-temperature | 0.0163 | 1 | 0.0163 | 0.2705 | 0.6143 | |

| C-pH | 0.0315 | 1 | 0.0315 | 0.5236 | 0.4859 | |

| AB | 0.0243 | 1 | 0.0243 | 0.4039 | 0.5393 | |

| AC | 0.0752 | 1 | 0.0752 | 1.25 | 0.2898 | |

| BC | 0.0317 | 1 | 0.0317 | 0.5258 | 0.4850 | |

| A2 | 1.79 | 1 | 1.79 | 29.70 | 0.0003 | |

| B2 | 1.16 | 1 | 1.16 | 19.20 | 0.0014 | |

| C2 | 0.4138 | 1 | 0.4138 | 6.87 | 0.0255 | |

| Residual | 0.6021 | 10 | 0.0602 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.3626 | 5 | 0.0725 | 1.51 | 0.3301 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 0.2395 | 5 | 0.0479 | |||

| Cor Total | 4.78 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, X.; Li, X.; Guan, W.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ran, S.; Ma, L. Enhancement of Cellulase Production by Penicillium oxalicum Using Traditional Chinese Medicine Residue and Its Application in Flavonoid Extraction. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121150

Zeng X, Li X, Guan W, Hu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Ran S, Ma L. Enhancement of Cellulase Production by Penicillium oxalicum Using Traditional Chinese Medicine Residue and Its Application in Flavonoid Extraction. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121150

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Xiaoxi, Xuan Li, Wenjun Guan, Zilin Hu, Yuanke Zhang, Cheng Zhang, Song Ran, and Liang Ma. 2025. "Enhancement of Cellulase Production by Penicillium oxalicum Using Traditional Chinese Medicine Residue and Its Application in Flavonoid Extraction" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121150

APA StyleZeng, X., Li, X., Guan, W., Hu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., Ran, S., & Ma, L. (2025). Enhancement of Cellulase Production by Penicillium oxalicum Using Traditional Chinese Medicine Residue and Its Application in Flavonoid Extraction. Catalysts, 15(12), 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121150