Abstract

A LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 heterojunction photocatalyst composite was constructed for the removal of tetracycline (TC). The structure, morphology, and elemental composition of the composite were systematically characterized using tools such as XRD, SEM, and XPS. The results from characterization jointly verified the successful construction of a LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 heterojunction. UV–vis DRS analysis further revealed a narrowing of the optical bandgap from 3.29 eV to 2.24 eV, which enhanced visible-light absorption. Characterization via XPS identified the presence of Fe2+/Fe3+ mixed valence states, while bismuth predominantly existed in the stable Bi3+ state. Under simulated sunlight (300 W xenon lamp) irradiation, the photocatalytic performance of LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 was systematically evaluated. The results demonstrated that the LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 composite achieved a removal efficiency of 95% for TC within 120 min, with a reaction rate constant of 0.023 min−1. The construction of heterojunction greatly increased not only the removal efficiency but also the reaction rate. For instance, the first-order reaction rate constants of LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 were 3.8 and 4.7 times higher than those of pure LaFeO3 and Bi4Ti3O12. TC removal by the composite was affected by dosage, initial TC concentration, and pH of the water. The composite exhibited the best performance at a dosage of 1.6 g/L with a pH around 7–8 and an initial TC concentration less than 20 mg/L. Anions such as Cl− and NO3− had minimal impact on its photocatalytic activity, whereas H2PO4−, humic acid, showed inhibitory effects. Free radical trapping experiments further confirmed that holes (h+) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) were the primary active species in the process.

1. Introduction

Antibiotics are widely used to treat bacterial and fungal infections [1]. However, overuse of antibiotics leads to severe residual presence, which, in turn, results in adverse effects on global environmental health. Due to their stable chemical structures, antibiotics take a long time to degrade completely in the natural environment. Studies have shown that antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and antibiotic resistance genes have been detected in multiple environmental media [2,3]. These pollutants not only exacerbate the spread and evolution of antibiotic resistance, but also contaminate aquatic ecosystems and compromise the quality and safety of aquatic products [4,5]. Therefore, the effective removal of antibiotics from the environment is of great significance for controlling the spread of drug resistance and reducing public health risks.

Tetracycline (TC) is a low-cost and broad-spectrum antibiotic that exhibits inhibitory activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [6]. It is widely used for disease prevention, infection treatment, and growth promotion in both humans and animals. Presence of TC in aquatic environments could be attributed to discharges from pharmaceutical industries, hospitals, agriculture, animal husbandry and sewage, etc. [7]. Once in the environment, it tends to accumulate through the food chain, thus causing toxicity to the microbial community and promoting the spread of antibiotic resistance genes [8].

Biological treatment, membrane separation, adsorption, and advanced oxidation are technologies predominantly employed in removing TC from aquatic environments. Shang et al. [9] observed that 90% of TC was degraded successfully via anaerobic digestion. As a matter of fact, the presence of TC at a low concentration (<50 mg/L) was conducive to the hydrolysis and acidogenesis processes. Du et al. [10] constructed an iron–carbon wetland micro-fuel cell to overcome the low biodegradability and inhibition effects of TC and achieved a 100% removal after 48 h. On the other hand, membrane separation technologies for TC removal were highly efficient, with a low need for floor space and energy consumption. Many studies in this field have focused on the development of new membranes to enhance their ability to remove TC [11,12]. Magnetic graphene oxides, biochar, carbon aerogel, etc., are adsorbents that have been under investigation to remove pollutants, especially antibiotics [13]. Thanks to these adsorbents’ high specific surface area, porous network, and durable structure, adsorption showed its unique advantages in efficiency, operational simplicity, life-cycle cost effectiveness, and environmental friendliness [14].

Advanced oxidation, including ozonation [15], persulfate/peroxymonosulfate [16], Fenton and photo-Fenton [17], and electrochemical and photocatalytic oxidation [18], is renowned for its high efficiency and mineralization capability. Unlike adsorption or membrane filtration, advanced oxidation destroys the target compounds by converting them into less harmful substances or completely mineralizing them into CO2 and H2O. The technology produces little or no sludge, which minimizes the cost and complexity involved with sludge management for technologies such as biological treatment [19].

In recent years, photocatalytic degradation technology based on advanced oxidation processes has emerged as a potential candidate for TC removal [20,21]. The structure and composition of the semiconductors are critical to the performance of photocatalysis [22]. The construction of heterostructure composites is a useful strategy to increase the separation of photo-excited carriers and improve the photocatalytic performance.

Due to their structural stability and composition flexibility, ferrite-based semiconductors are photocatalytic materials under intense investigation in recent years [23]. In particular, LaFeO3, an iron-based perovskite-type oxide and a typical p-type semiconductor, possesses a narrow band gap (around 2.0 eV). It is also non-toxic and recyclable magnetically, making it a promising visible-light-driven photocatalyst [24]. However, the use of LaFeO3 was limited due to its easy recombination of photogenerated carriers [25]. In addition, LaFeO3 particles tend to agglomerate. The construction of a heterostructure is one of the techniques commonly employed for the modification of LaFeO3 to improve its photocatalytic oxidation applicability.

On the other hand, layered bismuth-based semiconductors gained prominence as promising photocatalytic materials, owing to their unique structures composed of alternating [Bi2O2]2+ layers and anionic groups. This structure results in highly dispersed energy levels, a narrowed band gap, and enhanced photogenerated charge carrier transport, leading to their remarkable ability for the removal of pollutants [26].

A number of studies have tried to construct heterostructures by combining LaFeO3 with Bi3+-containing compounds since Bi3+ exhibits strong photocatalytic activity. The most commonly employed compounds include Bi2O3, BiVO4, Bi4Ti3O12, Bi12TiO20, Bi2O2CO3, and BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) [27,28]. Guan et al. [29] synthesized a series of X-LaFeO3/BiOBr heterojunction composite photocatalysts (x = 10%, 20% and 30%) using a hydrothermal method. Their study demonstrated that the synergistic effect between the Z-scheme electron transfer mechanism and the photo-Fenton process enables 20% LaFeO3/BiOBr to achieve a Rhodamine B degradation of 98.2% within 30 min. Mirhosseini et al. [30] constructed a heterojunction photocatalyst by coupling LaFeO3 nanoparticles (mass fraction: 12.5%) with Bi2WO6 via a solvothermal approach. The composite exhibited remarkable performance in TC degradation, with photocatalytic activity 20 times and 10 times higher than that of pure LaFeO3 and Bi2WO6, respectively. Furthermore, Yue et al. [31] prepared X-LaFeO3/Bi2S3 (X = 5, 15, 50, 75%) composites through a hydrothermal route and evaluated their performance with Amido Red 18 (AR18) as the target pollutant. The results indicated that the 15%-LFO/BS sample achieved 99% degradation of AR18 within 40 min. Gao et al. [32] reported the successful synthesis of a BiOBr/FeWO4 Type II heterojunction. Results showed that FeWO4 extended the light response range of BiOBr and achieved a 90.4% degradation rate of doxycycline within 1 h while demonstrating good stability and catalytic reusability.

This research attempted to employ Bi4Ti3O12 as a Bi-based compound to construct a heterojunction composite with LaFeO3. Bi4Ti3O12 belongs to the Aurivillius family of compounds, with its valence band formed by the hybridization of Bi 6s and O 2p orbitals. Compared to Sillén-structured BiOX materials, the Aurivillius phase exhibits significant spontaneous polarization, which generates a strong built-in electric field within the material [33]. This field not only effectively promotes the separation of photogenerated electron–hole pairs but also enhances the migration of holes to the catalyst surface, thereby significantly improving the material’s oxidation activity and charge transport efficiency. However, Bi4Ti3O12 has a band gap of approximately 3.2 eV, which leads to limitations, such as low visible light utilization and high recombination rate of photogenerated charge [34,35]. Due to the high structural match between the perovskite-like layers [Bi12Ti3O10]2− in Bi4Ti3O12 and the perovskite-type LaFeO3, heteroepitaxial growth with low lattice mismatch can be achieved.

In this study, LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 composite was prepared via a solvothermal method. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV–vis DRS) were used to obtain the morphology, crystalline structure, elemental composition, and chemical state of the composite (LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12) and compare them with those of LaFeO3 and Bi4Ti3O12. The photocatalytic performances of these materials were evaluated using TC in water as the target pollutant. Furthermore, the effects of initial TC concentration, dosage of the materials, pH of the wastewater, and the impact of co-existing anions and humic acid on the TC removal efficiency were investigated in detail. The goal was to offer theoretical insights and practical references for the development of novel catalysts and provide effective technical support for the treatment of TC.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characteristics of Materials

2.1.1. Crystal Structures

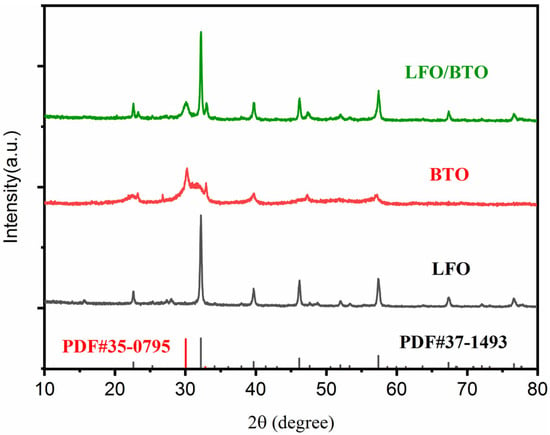

The crystal structures of LaFeO3 (LFO), Bi4Ti3O12 (BTO), and the LFO/BTO composite were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Figure 1, LFO exhibited strong characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 22.66°, 32.20°, 39.70°, 46.22°, 51.94°, 53.36°, 57.44°, 67.4°, 72.24°, and 76.74°, which correspond to the (101), (121), (220), (202), (141), (311), (240), (242), (143), and (204) crystal planes, respectively. These peaks match well with the standard card for orthorhombic perovskite LFO (PDF #37-1493) [36], confirming the successful synthesis of pure-phase LFO. The diffraction peaks of BTO were observed at 23.28°, 30.20°, 32.92°, 39.7°, 42.26°, and 57.22° in accordance with the standard card (PDF #35-0795) [37], corresponding to the (111), (171), (0120), (280), (1131), and (173) crystal planes. Diffraction peaks detected in the XRD patterns of LFO/BTO composite were of LFO or BTO, indicating high sample purity and successful incorporation of LFO with BTO without disrupting the original framework.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of LFO, BTO, and LFO/BTO.

2.1.2. Morphology

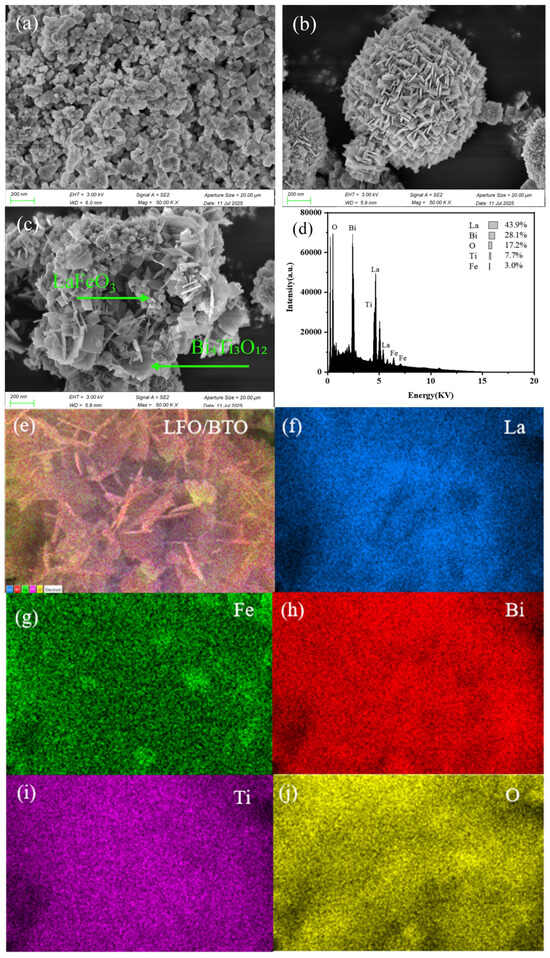

SEM images in Figure 2 clearly reveal the microscopic morphology and structural features of LFO, BTO, and their composite. Pure-phase LFO (Figure 2a) consists of smooth and uniformly elliptical nanoparticles with an average particle size of approximately 60 nm. Figure 2b shows that BTO formed microspheres through the self-assembly of regular nanosheets. Figure 2c displays the morphology of LFO/BTO. LFO is observed to be uniformly dispersed on the surface of BTO microspheres, proving the construction of heterostructures. Figure 2d,e show the results of the SEM-EDS analysis. They show that the mass percentages of La, Bi, O, Ti, and Fe in the material were 43.9%, 28.1%, 17.2%, 7.7%, and 3.0%, respectively. Moreover, elemental mapping in Figure 2f–j visually illustrate the uniform distribution of elements of La, O, Fe, Ti, and Bi.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy of (a) LFO; (b) BTO; (c) LFO/BTO; (d) energy-dispersive spectroscopy of LFO/BTO; (e) energy-dispersive spectroscopy layered image of LFO/BTO; (f–j) elemental mappings of LFO/BTO.

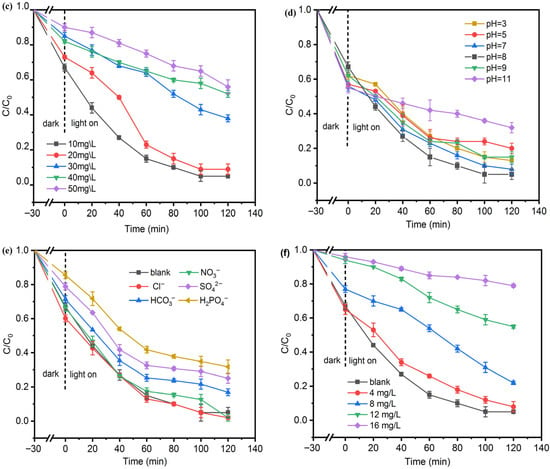

2.1.3. UV–vis Diffuse Reflectance Analysis

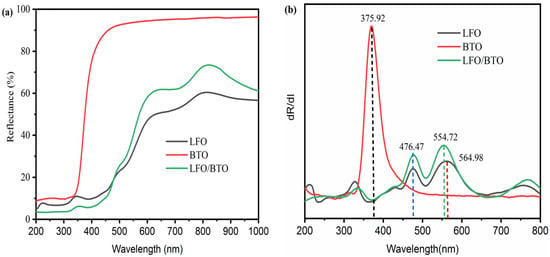

Figure 3 is the ultraviolet–visible diffuse reflectance spectra (UV–vis DRS) of BTO, LFO, and LFO/BTO.

Figure 3.

UV–vis DRS analysis of LFO, BTO, and LFO/BTO: (a) DRS spectra; (b) first derivative curves.

As shown in Figure 3a, compared with pure BTO, the reflectance of the LFO/BTO composite in the 400–800 nm visible light range is significantly reduced. Its reflectance behavior is similar to that of pure LFO, indicating that the introduction of LFO effectively enhances the composite’s response to the visible light region. Figure 3b further displays the first derivative curves of the DRS spectra. The absorption edge of pure BTO is located at λ = 375.92 nm. The band gap was calculated to be 3.29 eV using Equation (1) [29]:

where λ represents the peak wavelength, and 1240 is a constant.

Pure LFO shows a distinct derivative peak at λ = 564.98 nm and the band gap of 2.19 eV. The absorption edge of the LFO/BTO composite is significantly red-shifted to λ = 554.72 nm, compared with that of pure BTO, and the calculated bandgap is reduced to 2.24 eV. These results indicate that a heterojunction structure was successfully constructed between LFO and BTO, achieving a synergistic effect through band alignment. This could potentially enhance the carrier separation efficiency of the wide-bandgap semiconductor and the visible light absorption capability of the narrow-bandgap semiconductor.

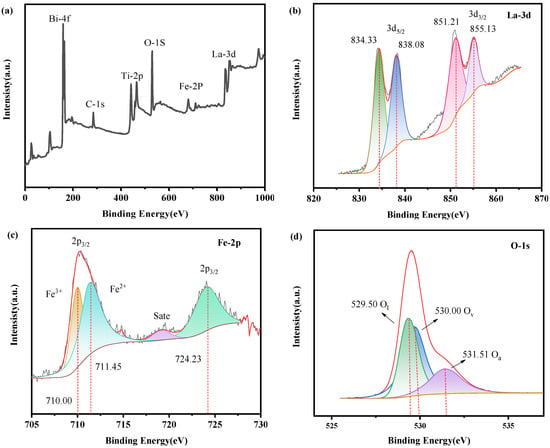

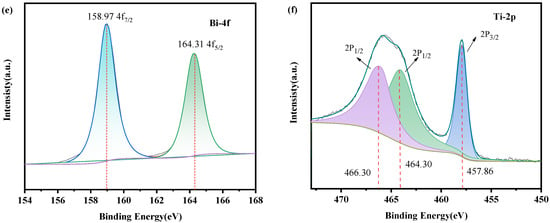

2.1.4. XPS Analysis

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was next conducted to determine the elemental composition and chemical valence state of the LFO/BTO. Results are shown in Figure 4. The spectra were calibrated using the C 1s peak (binding energy 284.80 eV). The full survey spectrum (Figure 4a) confirms the presence of five elements in the composite: Bi, Ti, O, La, and Fe. The high-resolution La-3d XPS spectrum is shown in Figure 4b, displaying four characteristic peaks. The peaks at binding energies of 834.33 eV and 838.08 eV correspond to the main peak and its satellite peak of La-3d5/2, respectively. The peaks at binding energies of 851.21 eV and 855.13 eV correspond to the main peak and its satellite peak of La-3d3/2. The calculated spin–orbit splitting energy for the La 3d orbital is 16.88 eV, which is consistent with data from Mishra et al. [38]. The high-resolution Fe 2p XPS spectrum is shown in Figure 4c. In the Fe 2p region, the peaks at binding energies of 710.00 eV and 711.45 eV correspond to the Fe 2p3/2 orbital signals of Fe2+ and Fe3+, respectively [39]. The binding-energy difference between Fe2+ and Fe3+ is larger than the peak width of the 2p3/2 sub-level. This allows for the peaks of the two oxidation states to be clearly separated in the XPS spectrum. Therefore, two peaks were observed in the 2p3/2 region. These mixed-valence states significantly inhibit electron–hole recombination. The peak at a binding energy of 724.23 eV corresponds to the Fe 2p1/2 orbital signal. A distinct satellite peak (labeled “sate.”) is observed between the Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 peaks. Dastjerdi et al. [39] argued that peak shape is affected by the overall spin–orbit splitting, which could result in a wider energy range. Consequently, the two peaks (corresponding to Fe2+ and Fe3+) overlapped and “crowded together” into one. In the O 1s region (Figure 4d), the peaks at binding energies of 529.50 eV, 530.00 eV, and 531.51 eV correspond to lattice oxygen (Ol), oxygen vacancies (Ov), and adsorbed oxygen (Oa), respectively. The high-resolution Bi-4f XPS spectrum is shown in Figure 4e. The peak at a binding energy of 158.97 eV corresponds to the Bi-4f7/2 orbital, while that at 164.31 eV corresponds to the Bi-4f5/2 orbital. The binding-energy difference between these two peaks is 5.34 eV, which aligns with the typical peak splitting pattern of Bi3+, indicating that Bi in the material primarily exists in the form of Bi3+ [40]. The high-resolution Ti 2p XPS spectrum is shown in Figure 4f. The characteristic peaks of Ti4+ are clearly visible. The peaks at 457.86 eV and 464.30 eV correspond to the Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2. Additionally, an extra peak appears at a binding energy of 466.30 eV. This phenomenon arises from the partial overlap between the Bi 4d3/2 peak and the Ti 2p orbital peak due to their close binding energies, resulting in the observed extra peak [41].

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of LFO/BTO: (a) survey spectrum; high-resolution XPS spectra of (b) La-3d, (c) Fe-2p, (d) O-1s, (e) Bi-4f, and (f) Ti-2p.

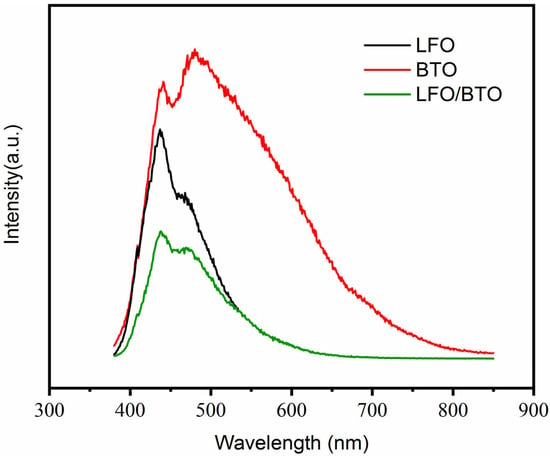

2.1.5. PL Analysis

PL spectra are used to illustrate the charge transfer, separation, and electron–hole pair recombination in the semiconductors, where a lower PL intensity typically indicates more efficient charge separation [30]. As shown in Figure 5, BTO exhibits the most intense photoluminescence PL peak, indicating the highest rate of electron–hole recombination. In contrast, the BTO/LFO composite shows the weakest PL intensity, suggesting superior charge separation efficiency. This enhancement is attributed to the heterojunction interface between BTO and LFO, which effectively separates the charge carriers spatially, thereby boosting the photocatalytic activity.

Figure 5.

PL spectra of BTO, LFO, and BTO/LFO.

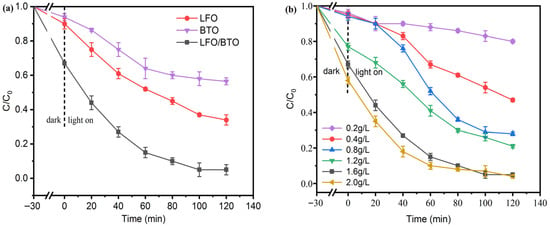

2.2. Performance Analysis of Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline

Based on characterization results, the LFO/BTO composite was successfully synthesized. The photocatalytic degradation performance of the composite toward TC were systematically evaluated and compared with those of LFO and BTO in Figure 6a. The initial TC concentration was 10 mg/L, with a catalyst dosage of 1.6 g/L and the initial pH of 8.0. After 30 min in the dark, 10%, 6%, and 33% of TC were removed by LFO, BTO, and LFO/BTO. This could be attributed to adsorption. Table S1 lists the BET surface area and pore volumes of these materials, and LFO/BTO boasts a higher surface area of 20.91 m2/g and pore volume of 0.14 cm3/g. By comparison, surface areas of LFO and BTO are 15.23 m2/g and 10.20 m2/g, respectively. However, adsorption reached equilibrium at 30 min. Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials shows the TC removal results of these three materials in the dark for 240 min. TC removal rose only slightly to 12%, 10%, and 35% as the time of adsorption was extended to 240 min. Therefore, in all the tests followed, the dark stage was set at 30 min. The experiment with the light turned on continued for 120 min. Under the same conditions, the performance followed the order of LFO/BTO > LFO > BTO. After 120 min, BTO managed to remove only 44% of the original TC. This limited removal ability could be due to its wide bandgap (3.29 eV) and high recombination rate of photogenerated electron–hole pairs. Kumar et al. [42] also argued that the weak catalytic performance of BTO was caused by rapid carrier recombination. LFO performed better than BTO with 66% removal. TC removal by LFO/BTO reached 95% after 120 min of illumination. The kinetics of the reaction were calculated, and the results are shown in Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials. The first-order reaction rate constant for the LFO/BTO composite was 0.0230 min−1, which is 3.8 times and 4.7 times higher than those of pure LFO (0.0086 min−1) and BTO (0.0049 min−1). These results indicate that the heterojunction formed between LFO and BTO significantly enhanced the photocatalytic performance of the composite. The performance of LFO/BTO is comparable or even superior to other materials under investigation. For instance, Gan et al. [43] achieved a 90.63% TC removal with a g-C3N4/BaTiO3/PVDF photocatalytic-membrane separation coupled system. Zhang et al. [44]. constructed an S-scheme BaTiO3/g-C3N4 heterojunction with a TC removal of 91.88%.

Figure 6.

Photocatalytic removal of TC: (a) comparison of LFO, BTO, and LFO/BTO; (b) effects of LFO/BTO dosage; (c) effects of initial TC concentration; (d) effects of initial pH; (e) effects of common anions; (f) effects of humic acid.

To further optimize the TC removal conditions for LFO/BTO, the effects of catalyst dosage were investigated. As shown in Figure 6b, there is a general increase in TC removal with the increase in dosage. TC removal increased from 22% at 0.2 g/L to 95% at 1.6 g/L after 120 min. The reaction rate constant increased from 0.00149 min−1 to 0.0230 min−1 (Figure S3) as the dosage rose from 0.2 g/L to 1.6 g/L. Further increasing the dosage to 2.0 g/L resulted in no significant change in removal efficiency (96%), likely due to agglomeration of excessive catalyst at a fixed TC concentration, which reduced active sites and introduced a light-shielding effect [45].

At a dosage of 1.6 g/L and a reaction time of 120 min, the effect of initial TC concentration (ranging from 10 to 50 mg/L) on the removal was next investigated. As shown in Figure 6c, the removal efficiency decreased with increasing TC concentration. At a concentration < 20 mg/L, more than 90% of the original TC was removed. TC removal drops to 44% at a concentration of 50 mg/L. The TC concentration also affected reaction rates. Figure S4 in Supplementary Materials shows that the reaction rate constant decreased markedly from 0.0230 min−1 at 10 mg/L to 0.00351 min−1 at 50 mg/L. The effect of concentration on TC removal could be explained by the following: (1) The active sites are limited at a fixed photocatalyst dosage. At higher concentrations, there are not enough sites for every TC molecule. (2) It is also possible that intermediate products generated during degradation could be adsorbed onto the catalyst surface, thus blocking active sites. It appears that a TC concentration of less than 20 mg/L was optimal for LFO/BTO photocatalytic removal.

Besides initial concentration, the effects of pH were also studied (Figure 6d). TC removal peaked at pH around 7–8, with removal efficiency reaching as high as 95% and a reaction rate constant of 0.023 min−1. At this pH range, the negatively dissociated forms of TC (TCH−, TC2−) were more readily adsorbed onto the catalyst surface due to electrostatic attraction [46]. Under acidic conditions (pH = 3–5), a high concentration of H+ could suppress the dissociation of TC, causing it to exist predominantly in the positively charged form of TCH3+. Furthermore, due to the acidification effect of HCl on the solution, Cl− consumes ·OH to generate ·ClO, thus also adversely affecting removal. Removal of TC decreased to around 80% at a pH of 5. A high pH was also not conducive to TC removal. At a pH of 11, only 68% was removed, with a reaction rate constant of 0.00434 min−1 (Figure S5). This is likely because TC exists as anions under strongly alkaline conditions, leading to electrostatic repulsion with the negatively charged catalyst surface, thereby inhibiting adsorption and subsequent degradation.

To investigate the effects of common anions and humic acid (HA) in actual water bodies on the photocatalytic process, experiments were conducted under optimal conditions (dosage of 1.6 g/L, pH = 8, and initial TC = 10 mg/L) by adding inorganic anions (Cl−, SO42−, HCO3−, NO2−, and H2PO4−) at a concentration of 5 mmol/L and humic acid at concentrations ranging from 4 to 16 mg/L. The results are shown in the corresponding Figure 6e,f.

Cl− and NO2− slightly promoted TC removal, possibly due to their contribution to the generation of reactive oxygen species, though the effect was almost negligible. Compared with the blank group, H2PO4− exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect, reducing the TC removal to 68%. The order of inhibition of the anions was H2PO4− > SO42− > HCO3−. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that anions, such as H2PO42-, may form complexes with metal ions on the photocatalyst surface, thus changing the crystal structure of the photocatalyst and affecting its electronic and band structure. Moreover, these anions may compete for active sites on the catalyst surface [47]. The effects of anions on the reaction constant rate are consistent with those on removal efficiency. Kinetics results in Figure S6 show that the presence of Cl− and NO2− had little or even a positive impact, while reaction rate constants decreased in the presence of H2PO4−, SO42−, and HCO3−. Due to its broad light absorption characteristics and abundance of functional groups, such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and phenolic hydroxyl groups, humic acid can adsorb onto the photocatalyst surface via hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, or coordination, shielding active sites and significantly inhibiting the photocatalytic process [48]. As shown in Figure 6f and Figure S7 in Supplementary Materials, at a low humic acid concentration of 4 mg/L, TC removal was not greatly affected. However, as humic acid increased from 8 mg/L to 16 mg/L, both the removal efficiency and reaction rate constant dropped, indicating that higher HA concentrations lead to more significant inhibition.

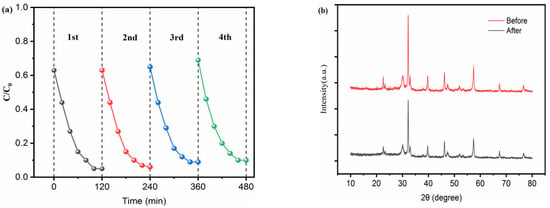

2.3. Reusability Tests

Reusability is one of the essential factors for evaluating the application potential of catalysts. In this study, a cyclic treatment process of “centrifugal collection-cleaning-drying” was adopted to conduct a four-cycle reuse experiment on the catalyst, and the results are shown in Figure 7. Figure 7a shows the cyclic TC removal performance. After four cycles, the removal of TC decreased slightly from the initial 95% to 90%, indicating that its catalytic activity can be well retained. To further verify the structural stability, XRD characterization was performed on the catalyst after four cycles of reuse (Figure 7b). There is no obvious shift in the position of the characteristic diffraction peaks of the composite and no significant attenuation in the peak intensity, which proves that its crystal structure remains intact. In conclusion, the composite has both excellent cyclic reuse performance and structural stability, providing important support for its practical application.

Figure 7.

(a) Reusability tests for TC removal by LFO/BTO; (b) comparison of XRD pattern of LFO/BTO before and after photocatalyst process.

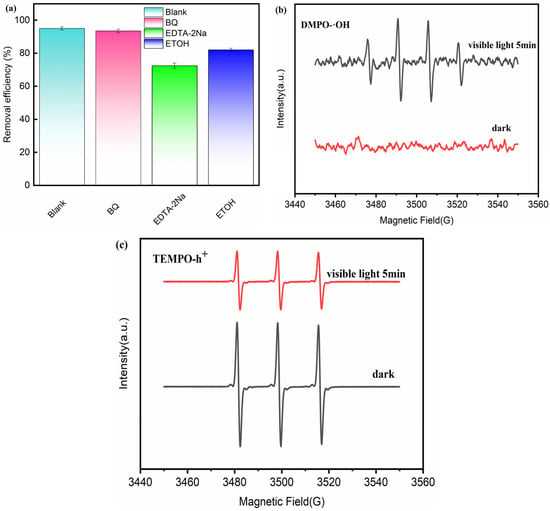

2.4. Free Radical Trapping

To reveal the active radicals in the reaction system, free radical scavenging experiments were carried out, with the results shown in Figure 8. Chemicals, p-benzoquinone (BQ), disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA-2Na), and ethanol (ETOH), were selected to sequentially and selectively scavenge superoxide radicals (·O2−), photogenerated holes (h+), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) [49].

Figure 8.

(a) Free radical trapping experiments of LFO/BTO; (b) EPR signal of DMPO-·OH; (c) EPR signal of TMPO-h+.

After adding BQ, the TC removal only decreased slightly from 95% to 93%, indicating that ·O2− made a small contribution to the removal process. When EDTA-2Na and ETOH were added separately, the TC removal decreased to 74% and 82%. The results show that photogenerated holes (h+) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) are the active species that play a major role in the system, while the role of superoxide radicals (·O2−) is relatively limited. Figure 8b,c show the EPR spectra of DMPO-·OH and TEMPO-h+ in the dark and under 5 min of light irradiation. Distinct characteristic peaks of DMPO-·OH can be observed after 5 min of illumination. Characteristic peaks of TMPO-h+ weekend under visible light compared with those in the dark. These results confirm that h+ and ·OH are the primary active species in this reaction.

2.5. Mechanism Investigation

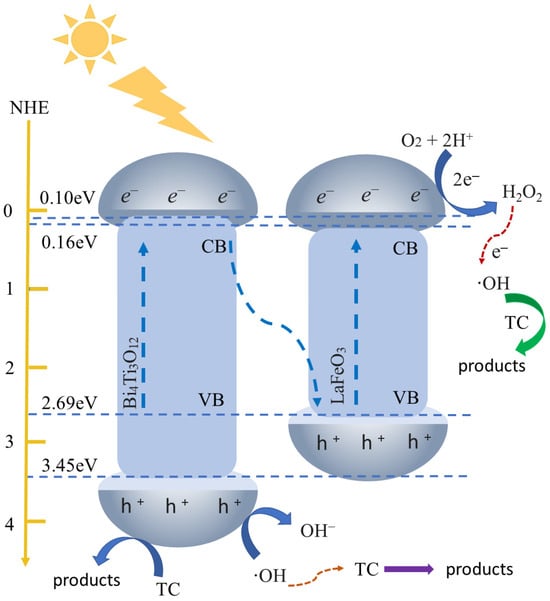

The redox capability and migration of photogenerated charges are highly dependent on the band potential of the photocatalyst. The band potential can be calculated using the following Equations (2)–(5) to infer the reaction mechanism of the catalyst [50].

where EVB: the valence band potential (eV); ECB: the conduction band potential (eV); X: absolute electronegativity of the semiconductor (eV); Ee: energy of free electrons on the hydrogen scale (≈4.5 eV vs. NHE). The value for a solid is calculated by taking the geometric mean of the electronegativity values of the atoms that constitute it. The absolute electronegativities of LFO and BTO, calculated via Equations (2) and (3), are 5.62 eV and 6.30 eV, respectively, which is consistent with those reported by Chen et al. [51].

Based on Equations (4) and (5), the EVB and ECB of LFO are 2.47 eV and 0.03 eV, while the EVB and ECB of BTO are 3.45 eV and 0.16 eV, respectively. Accordingly, the proposed photocatalytic mechanism of the LFO/BTO composite is illustrated in Figure 9. Due to the higher Fermi level of BTO compared to LFO, electrons spontaneously flow from BTO to LFO, causing the energy bands of BTO to bend downward and those of LFO to bend upward, thereby forming a built-in electric field at the interface directed from BTO to LFO.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of TC removal mechanism by LFO/BTO under visible light irradiation.

Under visible light irradiation (λ > 420 nm), photogenerated electrons in BTO transfer from its conduction band to the valence band of LFO, while the photogenerated holes remain in the valence band of BTO. Since the valence band potential of BTO (3.45 eV) is significantly higher than the redox potentials of of 1.99 eV vs. NHE and of 2.40 eV vs. NHE, it can drive the oxidation of water or hydroxide species, leading to the generation of hydroxyl radicals (·OH) or direct degradation of tetracycline (TC). On the other hand, the conduction band potential of LFO is 0.10 eV, which is more positive than the redox potential of O2/·O2− (−0.33 eV vs. NHE), preventing the direct reduction of oxygen to superoxide radicals. However, these conduction band electrons can react with H+ ions and oxygen in the solution to generate H2O2, which subsequently reacts with electrons to form highly oxidizing ·OH radicals. The above inferences are consistent with the results of free radical trapping experiments, indicating that holes (h+) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) are the primary active species in the photodegradation of tetracycline by LFO/BTO composite.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

All chemicals used in the study, including lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O), iron nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O), butyl titanate (C16H36O4Ti), bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO3)3·5H2O), ethylene glycol, absolute ethanol, sodium hydroxide, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, p-benzoquinone, isopropanol, and tetracycline, were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Shanghai, China, and were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

3.2. Materials Preparation

LaFeO3 was synthesized via a hydrothermal method [52]. First, 1.732 g of La(NO3)3·6H2O and 1.616 g of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O were added to 40 mL of a mixed solvent consisting of ethylene glycol and ethanol (volume ratio 9:1). The resulting mixture was stirred vigorously on a magnetic stirrer for 60 min, then transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and reacted at 180 °C for 24 h. After the reaction, the product was washed multiple times with deionized water and ethanol and dried in an oven at 60 °C. Finally, the powder was calcined in a muffle furnace at 800 °C for 4 h under air to obtain LaFeO3, which was denoted as LFO

Bi4Ti3O12 was synthesized via a solvothermal method. In total, 0.85 mL of C16H36O4Ti was added to 30 mL of NaOH solution (3 mol/L). Next, 1.61 g of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O was added to the solution and stirred until complete dissolution. The mixture was then transferred into a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and reacted at 180 °C for 20 h. After the reaction, the autoclave was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The resulting precipitate was collected, centrifugally washed three times with deionized water, and dried at 60 °C to obtain Bi4Ti3O12, denoted as BTO.

The LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 composite was prepared by depositing LaFeO3 nanoparticles onto the surface of Bi4Ti3O12 via a hydrothermal method. The specific steps are as follows: 0.85 mL of C16H36O4Ti was added to 30 mL of 3 mol/L NaOH solution and stirred for 30 min. Then, 1.61 g of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O was added and stirred until complete dissolution. The resultant solution was denoted as Solution A. Solution B is LaFeO3 solution with a concentration of 11.286 g/L. Solution B was added to Solution A and stirred for 60 min. The mixed solution was then transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-lined hydrothermal reactor and reacted at 180 °C for 20 h. After completion, the reactor was cooled naturally to room temperature. The precipitate was collected and washed three times with deionized water and ethanol, then dried at 60–80 °C to obtain LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12. The sample was labeled as LFO/BTO.

3.3. Material Characterization

A variety of characterization techniques were employed to systematically analyze the physicochemical properties of the synthesized samples. The phase composition and crystal structure of the samples were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (Rigaku SmartLab SE, Tokyo, Japan), while surface morphology and microstructure of the materials were observed via Scanning Electron Microscopy (ZEISS Gemini SEM 300, Oberkochen, Germany). Specific surface area and pore volume were determined with an automated surface area and porosity analyzer (ASAP 2460, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). In addition, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha, Waltham, MA, USA), ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-3600i Plus, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), and photoluminescence spectroscopy (FLS1000, Edinburgh Instruments, Livingston, UK) were used to characterize the surface elemental composition and chemical states, light absorption characteristics, and photogenerated carrier behavior of the materials, respectively. Finally, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (Bruker-E500, Bruker, Hamburg, Germany) was applied to detect possible free radicals in the samples.

3.4. Evaluation of Photocatalytic Performance

A 300 W xenon lamp (JH-GHX-IV, Shanghai, China) equipped with a λ > 420 nm filter was used to simulate solar light. TC was selected as the target pollutant to evaluate the photocatalytic activity of the samples. During the reaction, the temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C using a low-temperature cooling-circulation pump (DLSB-5/−10 °C, Shanghai, China) and a low-temperature thermostatic bath (DC-0506, Shanghai, China). The specific experimental procedure was as follows: a certain amount of photocatalyst was added to 25 mL of TC solution at different concentrations, and the mixture was magnetically stirred in the dark for 30 min to achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium between TC and the photocatalyst. Subsequently, the xenon lamp was turned on for a 120 min reaction. Samples were taken every 20 min, filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. TC concentration was measured via a UV–vis absorption at 357 nm using an ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shanghai Mapada Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and TC removal efficiency (η) was calculated based on Equation (6).

where C0: Initial concentration of TC; Cₜ: TC concentration at time t.

In the experiments to test the effect of dosage, initial TC concentration, pH, and co-existing substances (anions and humic acid) on the photocatalytic performance, all the above procedures were kept the same. The amount of LFO/BTO added varied from 5 mg to 50 mg to change the dosage from 0.2 g/L–2.0 g/L. The range of TC concentration tested was 10 mg/L to 50 mg/L, while the pH of water was adjusted to 3–11 by 1 mol/L HCl or Na(OH). NaCl, Na2SO4, NaNO3, NaHCO3, and humic acid were added to test the effects of co-existing substances with a Cl−, SO42−, NO3−, and HCO3− concentration of 5 mmol/L, with humic acid concentrations varying from 4 to 16 mg/L.

All tests above were carried out in triplicate, and averages and standard errors were calculated.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully prepared a heterojunction LFO/BTO composite photocatalyst, which achieved a 95% TC removal within 120 min under simulated sunlight. By comparison, LFO and BTO removed 66% and 44% under the same conditions. In addition, the reaction rate constants of LFO/BTO were 3.8 and 4.7 times higher than those of LFO and BTO. In addition, the TC removal was affected by the dosage of photocatalyst, initial TC concentration, pH of the water, and co-existing substances. A dosage of 1.6 g/L was able to remove 95% of the TC at an initial concentration of < 20 mg/L. The optimal pH was 7–8, with TC removal dropping markedly as pH was raised to higher than 9 or lowered to less than 5. Co-existing anions, such as Cl− and NO2−, have minimal influence on the photocatalytic activity of LFO/BTO, whereas H2PO4−, SO42−, HCO3-, and humic acid (HA) demonstrate certain inhibitory effects.

Characterization results confirmed the successful construction of a heterojunction structure, which effectively promoted the separation of photogenerated charge carriers and broadened the visible-light response. The successful construction of the LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 heterojunction was collectively confirmed by XRD, SEM, and EDS elemental analysis. UV–vis DRS spectra revealed that the optical bandgap of the composite narrowed from 3.29 eV for pure Bi4Ti3O12 to 2.24 eV for LFO/BTO. This is accompanied by a distinct red shift in the absorption edge, indicating significantly enhanced visible-light response and more efficient separation of photogenerated electron–hole pairs. The XPS analysis further demonstrated that the mixed Fe2+/Fe3+ valence states in the material form efficient electron migration channels, thereby effectively suppressing the recombination of electron–hole pairs. Meanwhile, the predominant presence of Bi3+ in a stable state contributes to the consolidation of the material’s crystal structure. Mechanistic studies through radical trapping experiments verified that h+ and ·OH are the primary active species. The catalyst also exhibited excellent stability and reusability, maintaining high degradation efficiency without significant structural changes after four consecutive cycles, as confirmed by XRD. This study provides an efficient and recyclable photocatalytic technology for antibiotic wastewater treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121147/s1: Table S1. Specific surface area, pore size and pore volume of LFO, BTO and LFO/BTO; Figure S1: TC removal in dark by LFO, BTO and LFO/BTO; Figure S2: First-order kinetics (Ln(C/C0) = −kt) of TC removal by LFO, BTO, and LFO/BTO; Figure S3: First-order kinetics at different LFO/BTO dosage; Figure S4: First-order kinetics at different initial TC concentration; Figure S5: First-order kinetics at different initial pH; Figure S6: First-order kinetics at different co-existing anion; Figure S7: First-order kinetics at different humic acid concentration.

Author Contributions

W.C.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, review and editing; N.Z.: data curation, formal analysis, draft; S.Z.: visualization, investigation; Q.M.: methodology, data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Chongming Agricultural Scientific Innovation Project (2024CNKC-06-08).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TC | Tetracycline |

| LFO | LaFeO3 |

| BTO | Bi4Ti3O12 |

| LFO/BTO | LaFeO3/Bi4Ti3O12 |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| UV–vis DRS | UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy |

| EPR | Electron paramagnetic resonance |

| BQ | p-benzoquinone |

| EDTA-2Na | Disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate |

| ETOH | Ethanol |

References

- Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Meng, F. Antibiotics in Mariculture Systems: A Review of Occurrence, Environmental Behavior, and Ecological Effects. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenni, P.; Ancona, V.; Barra Caracciolo, A. Ecological Effects of Antibiotics on Natural Ecosystems: A Review. Microchem. J. 2018, 136, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Yuan, X.; Men, C.; Zuo, J. Antibiotic Intermediates and Antibiotics Synergistically Promote the Development of Multiple Antibiotic Resistance in Antibiotic Production Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Men, C.; Mao, Y.; Zuo, J. A Combined Evaluation of the Characteristics and Antibiotic Resistance Induction Potential of Antibiotic Wastewater during the Treatment Process. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 138, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Zou, J.; Zhou, A. Interactions of Microplastics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Effects on the Aquaculture Environments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, I.; Roberts, M. Tetracycline antibiotics: Mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. J. Microbiol. Mol. Bio. Rev. 2001, 65, 232–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Ke, Y.; Chen, C.; Xie, S. A Comprehensive Review on Biodegradation of Tetracyclines: Current Research Progress and Prospect. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Bruckmann, F.; Schnorr, C.E.; da Rosa Salles, T.; Nunes, F.B.; Baumann, L. Highly Efficient Adsorption of Tetracycline Using Chitosan-Based Magnetic Adsorbent. Polymers 2022, 14, 4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Chen, W.; Wei, D.; Li, X.; Tang, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Anaerobic Fermentation for Hydrogen Production and Tetracycline Degradation: Biodegradation Mechanism and Microbial Community Succession. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Bai, S.; Qian, J.; Zhan, P.; Hu, F.; Peng, X. Iron-Carbon Enhanced Constructed Wetland Microbial Fuel Cells for Tetracycline Wastewater Treatment: Efficacy, Power Generation, and the Role of Iron-Carbon. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 430, 132578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nemr, H.A.; El-Khouly, M.E.; Ulbricht, M.; Khalil, A.S.G. Interface engineering of a MXenes/PVDF mixed-matrix membrane for superior water purification: Efficient removal of oil, protein and tetracycline. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 28413–28417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Xie, A.; Liu, Y.; Xue, C.; Pan, J. Fabrication of Multi-Functional Imprinted Composite Membrane for Selective Tetracycline and Oil-in-Water Emulsion Separation. Compos. Commun. 2021, 28, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, R.; Varadavenkatesan, T.; Selvaraj, R. Tetracycline Adsorption Research (2015–2025): A Bibliometric Analysis of Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cai, T.; Zhang, S.; Hou, J.; Cheng, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Q. Contamination Distribution and Non-Biological Removal Pathways of Typical Tetracycline Antibiotics in the Environment: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho Costa, L.R.; Dall Agnol, G.; da Cunha, F.O.V.; de Oliveira, J.T.; Féris, L.A. Advanced Oxidation of Tetracycline: Synergistic Ozonation and Hydrogen Peroxide for Sustainable Water Treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 72, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huidobro, L.; Bautista, Q.; Alinezhadfar, M.; Gómez, E.; Serrà, A. Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Peroxymonosulfate Activation for Antibiotic Mineralization Using Electrosynthesized Nanostructured Bismuth Oxyiodides Thin Films. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Ding, M.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H. Ginkgo Biloba-Derived Biochar Loaded with FeOCl for Photo-Fenton Degradation of Tetracycline. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 184, 108790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, L.; Giacomo, E.C.; Paolo, M. Mechanistic studies in photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3730–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusami, A.B.; Sinha, S.; Ashokan, H.; Paul, M.V.; Hariharan, S.P.; Arun, J.; Gopinath, K.P.; Hoang Le, Q.; Pugazhendhi, A. Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) Combined Biological Process for Wastewater Treatment: A Review on Advancements, Feasibility and Practicability of Combined Techniques. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zango, Z.U.; Ibnaouf, K.H.; Lawal, M.A.; Aldaghri, O.; Wadi, I.A.; Modwi, A.; Zango, M.U.; Adamu, H. Recent Trends in Catalytic Oxidation of Tetracycline: An Overview on Advanced Oxidation Processes for Pharmaceutical Wastewater Remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chang, L.; Li, Y.; He, W.; Liu, K.; Cui, M.; Hameed, M.U.; Xie, J. High-Gravity Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline Hydrochloride under Simulated Sunlight. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Peng, B.; Wang, Z.; Han, Q. Advances in Metal or Nonmetal Modification of Bismuth-Based Photocatalysts. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2024, 40, 2305048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Armutlulu, A.; Wang, Y.; Yao, G.; Xie, R.; Lai, B. Visible-Light-Driven Removal of Atrazine by Durable Hollow Core-Shell TiO2@LaFeO3 Heterojunction Coupling with Peroxymonosulfate via Enhanced Electron-Transfer. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 303, 120889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M.; Ullah, H.; Usman, M.; Habibi-Yangjeh, A.; Tahir, A.A.; Wang, C.; Luo, W. Perovskite-Type Lanthanum Ferrite Based Photocatalysts: Preparation, Properties, and Applications. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 66, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Du, Z.; Wang, J.; Cai, H.; Bi, D.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tang, C.; Fang, Y. Construction of 2D/2D Bi2WO6/BN Heterojunction for Effective Improvement on Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 894, 162487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, H. Solar-driven selective oxidation over bismuth-based semiconductors: From prolte catalysts to diverse reactions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2313883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Xu, D.; Cheng, B.; Yu, J.; Ho, W. Review on Nanoscale Bi-Based Photocatalysts. Nanoscale Horiz. 2018, 3, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yu, S.; Huang, H. Emerging Polynary Bismuth-Based Photocatalysts: Structural Classification, Preparation, Modification and Applications. Chin. J. Catal. 2024, 57, 18–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Yang, H.; Sun, X.; Xian, T. Preparation and Promising Application of Novel LaFeO3/BiOBr Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton Removal of Dyes. Opt. Mater. 2020, 100, 109644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhosseini, H.; Mostafavi, A.; Shamspur, T. Highly Efficient LaFeO3/Bi2WO6 Z-Scheme Nanocomposite for Photodegradation of Tetracycline under Visible Light Irradiation: Statistical Modeling and Optimization of Process by CCD-RSM. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2023, 160, 107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Zhao, S.; Tong, J.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; Li, Z. Effective Removal of Neo Carmine Using Z-Type Heterojunction Composite LaFeO3/Bi2S3 as a Photo-Fenton-like Catalyst. Mater. Lett. 2024, 372, 137005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Gao, Y.; Sui, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Zou, D. Hydrothermal Synthesis of BiOBr/FeWO4 Composite Photocatalysts and Their Photocatalytic Degradation of Doxycycline. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 732, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Hu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T.; Huang, H. Layered Bismuth-Based Photocatalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 463, 214515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathi, A.; Arunachalam, P.; Kirankumar, V.S.; Madhavan, J.; Al-Mayouf, A.M. An Efficient Visible Light Driven Bismuth Ferrite Incorporated Bismuth Oxyiodide (BiFeO3/BiOI) Composite Photocatalytic Material for Degradation of Pollutants. Opt. Mater. 2018, 84, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, J.; Shen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Photothermal Effect Induced Humidity-Resistant Photocatalytic NO Removal over Dual-Defects Modified Bi/Bi4Ti3O12. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2026, 380, 125789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Kandi, D.; Parida, K. CdS QD decorated LaFeO3 nanosheets for photocatalytic application under visible light irradiation. J. Chem. Select. 2020, 20, 6153–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Jiao, X. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Characterization of Bi4Ti3O12 Powders from Different Precursors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2001, 36, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Priyadarshini, N.; Mansingh, S.; Parida, K. Recent Advancement in LaFeO3-Mediated Systems towards Photocatalytic and Photoelectrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 333, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastjerdi, O.D.; Shokrollahi, H.; Yang, H. The Enhancement of the Ce-Solubility Limit and Saturation Magnetization in the Ce0.25BixPryY2.75-x-yFe5O12 Garnet Synthesized by the Conventional Ceramic Method. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 2709–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Li, T.; Zhang, M.; Singh, H.; Huttula, M.; Cao, W. Iodine Doped Z-Scheme Bi2O2CO3/Bi2WO6 Photocatalysts: Facile Synthesis, Efficient Visible Light Photocatalysis, and Photocatalytic Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Qin, N.; Lin, E.; Yuan, B.; Kang, Z.; Bao, D. Synthesis of Bi4Ti3O12 decussated nanoplates with enhanced piezocatalytic activity. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 21128–21136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, P.; Wang, T.; Lai, C.W.; Sharma, G.; Dhiman, P. Recent Progresses in Improving the Photocatalytic Potential of Bi4Ti3O12 as Emerging Material for Environmental and Energy Applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 138, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Song, X.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J.; Huo, P. G-C3N4/BaTiO3/PVDF Membrane Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 152, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, F.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, S. Construction of BaTiO3/g-C3N4 S-Type Heterojunctions for Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 705, 135761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Peng, X.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, W. Z-Scheme CoS/Bi4O5I2 Heterostructure for Visible Light Catalytic Degradation of Tetracycline Hydrochloride: Degradation Mechanism, Toxicity Evaluation, and Potential Applications. Environ. Res. 2025, 276, 121483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pacheco, C.V.; Sánchez-Polo, M.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; López-Peñalver, J.J. Tetracycline Degradation in Aqueous Phase by Ultraviolet Radiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 187, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farner, B.J.; Turolla, A.; Piasecki, A.F.; Turolla, A.; Piasecki, A.F.; Bottero, J.Y.; Antonelli, M.; Wiesner, M.R. Influence of aqueous inorganic anions on the reactivity of nanoparticles in TiO2 photocatalysis. Langmuir 2017, 33, 2770–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J.; Jae Jeong, Y.; Sun Cho, I.; Lee, C.G.; Park, S.J.; Alvarez, P.J.J. The Inhibitory Mechanism of Humic Acids on Photocatalytic Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by TiO2 Depends on the Crystalline Phase. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Fareed, H.; Yang, H.; Xia, Y.; Su, J.; Wang, L.; Kang, L.; Wu, M.; Huang, Z. Mechanistic Insight into the Charge Carrier Separation and Molecular Oxygen Activation of Manganese Doping BiOBr Hollow Microspheres. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 629, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Yang, H.; Xian, T.; Xian, T.; Chen, X. Facile synthesis and enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity of novel p-Ag3PO4/n-BiFeO3 heterojunction composites for dye degradation. J. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, Y.; Meng, S.; Fu, X. Study on the Separation Mechanisms of Photogenerated Electrons and Holes for Composite Photocatalysts G-C3N4-WO3. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 150–151, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.Q.; Li, J.F.; Li, X.; Wang, C.W. Design and Fabrication of NiS/LaFeO3 Heterostructures for High Efficient Photodegradation of Organic Dyes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 504, 144363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).