Abstract

Efficient oxidation of refractory sulfides, such as dibenzothiophene (DBT) and its derivatives, provides a promising strategy to produce fuel oils with ultra-low sulfur content, or even completely sulfur-free. In this study, a series of non-stoichiometric molybdenum oxides (MoOx) were synthesized via a facile procedure and employed as efficient catalysts. These catalysts can effectively oxidize DBT and its derivatives into insoluble sulfones, which subsequently precipitate from the oil phase, achieving efficient sulfur removal. In this system, molecular oxygen from air can be activated by the MoOx catalysts with oxygen vacancies into superoxide radicals, which act as active oxygen species to efficiently oxidize refractory sulfides. Under atmospheric pressure at 120 °C, complete sulfur removal (100%) was achieved for both DBT and its derivatives, representing significantly milder conditions compared to conventional hydrodesulfurization. The aerobic oxidation system could be reused for up to 12 consecutive cycles without any significant decline in sulfur removal. And complete desulfurization (100%) was regained after a simple washing of the separated solid phase. Then, a possible reaction procedure was subsequently proposed to describe the desulfurization route. The remarkable catalytic performance, together with the facile synthesis strategy, indicates the potential of this approach for constructing other transition metal oxides used in various advanced aerobic oxidation reactions.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, environmental issues arising from the excessive emission of sulfur oxides (SOx) have attracted widespread attention [1,2,3]. Although the development of novel green energy technologies has progressed rapidly, the world still relies heavily on traditional fossil fuel oils. With the implementation of increasingly stringent regulations in recent years, deep desulfurization of fuel oils has become particularly important. Hydrodesulfurization (HDS) currently serves as a key method for sulfur removal from fuel oils [4,5], efficiently eliminating thiols, thioethers, and thiophenes, while being much less effective against dibenzothiophene (DBT) and its derivatives. To address the above challenge, various non-HDS strategies have been developed, including extractive desulfurization [6], bio-desulfurization [7], adsorptive desulfurization [8], and oxidative desulfurization (ODS) [9]. Here, the ODS technique is considered a promising strategy for the deep removal of DBT and its derivatives [10], while operating under atmospheric pressure and without the consumption of any H2. With this approach, DBT and its derivatives dissolved in the oil phase can be oxidized to their corresponding sulfones, which exhibit strong polarity, making them insoluble in the oil phase and thereby achieving deep desulfurization. Thus, the choice of oxidants and the design of catalysts are two key factors that need to be considered.

Generally, peroxides such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [11] and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) [12] are often selected as promising oxidants for the ODS process due to their strong oxidative capability under mild conditions. However, several limitations exist: the water generated during the use of H2O2 can reduce the quality of the final product, and the high flammability and toxicity of TBHP pose safety risks during storage, transportation, and handling, thereby limiting its practical application. These challenges highlight the importance of selecting efficient, safe, and cost-effective ODS systems for industrial use. Molecular oxygen (O2) from the air is regarded as one of the most green and low-cost oxidants [13]. However, the unique triplet ground-state electronic configuration of O2 makes it difficult to activate. Thus, many catalysts have been developed to effectively activate O2, including transition metal oxides (TMOs) [14], noble metals [15], metal–organic frameworks [16], and metal-free catalysts [17]. Among these catalysts, TMOs stand out as promising candidates for aerobic ODS reactions owing to their multiple oxidation states, facile synthesis, low cost, and excellent durability.

To enhance the catalytic performance of TMOs, various strategies have been employed, such as constructing nanostructured catalysts [18], supporting TMOs on suitable carriers [19], and creating oxygen vacancies [20]. Catalysts in the form of quantum dots [21], nanowires [22], and nanosheets [18], which are often fabricated via top-down or bottom-up approaches, have been reported to exhibit enhanced aerobic oxidation capabilities. However, the reported synthesis of nano-structured metal oxides generally involves multiple steps using toxic organic solvents and is inherently associated with low yields. For supported catalysts, the leaching of active sites often results in a noticeable decline in catalytic performance [23]. Thus, the facile construction of TMOs catalysts with oxygen vacancies would be a promising strategy. In TMOs, oxygen vacancies originate from the removal of lattice oxygen atoms from their original sites [24]. Liu’s study demonstrated that the presence of oxygen vacancies enhances substrate adsorption and facilitates the overall reaction process [25]. This feature helps overcome the difficulty of efficiently transferring O2 to the catalyst surface, as O2 is almost insoluble in the oil phase. Thus, TMOs catalysts with efficiently engineered oxygen vacancies in their crystal structures could serve as promising candidates for aerobic ODS processes.

Among the available metal elements, molybdenum was chosen for many redox reactions due to its multiple oxidation states, and high catalytic stability [26]. Therefore, a variety of molybdenum-based catalysts, including oxides [27], sulfides [28], polyoxometalates [29], bimetallic compounds [30], and MOFs [31], have been developed for highly efficient redox reactions. Here, molybdenum oxides have attracted considerable attention in the field of catalysis due to their unique properties [32]. Upon the removal of oxygen atoms from the lattice, non-stoichiometric molybdenum oxides (MoOx) are formed, where Mo(VI) is partially reduced to Mo(V) and Mo(IV) [33]. The reduced Mo sites in MoOx serve as chemically active centers that participate in the adsorption and catalysis of the reactants [32]. Thus, many strategies, such as ion bombardment or controlled annealing and chemical reactions in oxygen-poor conditions [34], have been developed to synthesize MoOx with oxygen vacancies. Among these methods, annealing Mo-containing precursors under an inert atmosphere represents one of the most facile strategies.

Herein, in this study, a series of MoOx catalysts containing oxygen vacancies were synthesized via calcination of recrystallized ammonium molybdate at different temperatures under a high-purity N2 atmosphere. The catalyst demonstrated excellent desulfurization activity, achieving 100% removal of both DBT and its derivatives from the oil phase. In addition, the reaction conditions employed in this study (120 °C and 1 atm) are significantly milder than those required for the conventional HDS process (380 °C and 80 atm). Experimental studies have shown that oxygen vacancies play a crucial role in aerobic oxidation. They enable the activation of O2 from air into superoxide radicals (O2−•), which can efficiently oxidize refractory sulfides into insoluble sulfones. The resulting sulfones spontaneously separate from the oil phase, achieving effective sulfur removal. In addition, the catalyst used in this reaction system exhibits excellent recyclability and renewability. The facile synthesis process, together with the excellent sulfur removal performance of the constructed MoOx catalysts, highlights their great potential for practical applications.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterizations

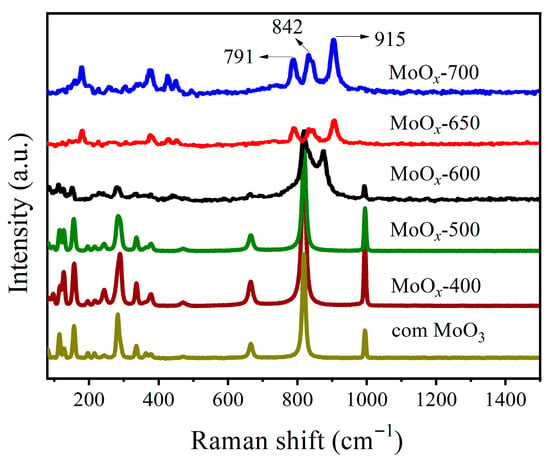

As an efficient characterization strategy to detect slight vibration changes associated with the emergence of phase transitions and defects, Raman spectra of MoOx calcined at different temperatures and commercially available MoO3 (com MoO3) were conducted (Figure 1). Initially, for com MoO3, the asymmetric stretching of Mo=O (va(Mo=O)) around 997 cm−1 could be viewed. Then, stretching vibrations viewed at 823 and 667 cm−1 could be attributed to v(Mo2–O) and v(Mo3–O), respectively. In addition, the characteristic peaks in the range of 150–400 cm−1 could be ascribed to bending, wagging, and twisting vibrations [35]. For MoOx calcined at 400 °C and 500 °C, similar Raman spectra could be detected, indicating the generation of a basic MoO3 lattice framework. For MoOx calcined at higher temperatures, the prominent peaks at 997, 823, and 667 cm−1 disappeared. Simultaneously, three new peaks at 791, 842, and 915 cm−1 were observed, which can be ascribed to the stretching vibrations of the bridging oxygen bonds in MoOx-700 [36,37]. Generally, the appearance or disappearance of peaks, variations in peak intensity, and shifts in peak position in the Raman spectra indicate variations in chemical bonding. In this study, the changes in the Raman spectra might be attributed to the generation of oxygen vacancies.

Figure 1.

Raman spectra of MoOx-M and com MoO3.

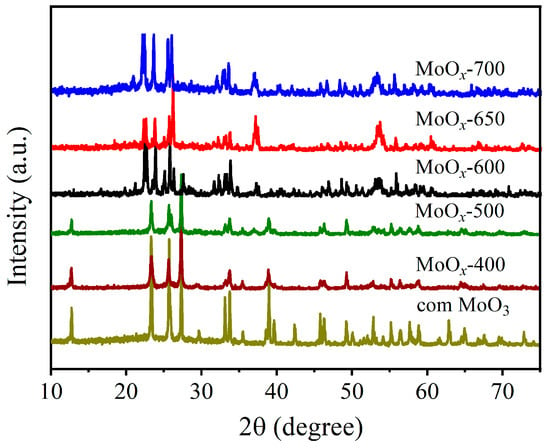

Then, X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were conducted to determine the lattice changes of MoOx during the calcination procedure (Figure 2). For com MoO3, its orthorhombic phase was clearly identified (JCPDS card: 76-1003), exhibiting lattice constants of a = 3.962 Å, b = 13.855 Å, and c = 3.699 Å [38]. For MoOx calcined at lower temperatures, similar diffraction peaks could be observed, with no other phases detected, indicating the generation of the orthorhombic MoO3 lattice framework at these temperatures. For the MoOx calcined at higher temperatures, the generation of MoOx containing both a monoclinic phase (JCPDS card: 78-1073) and an orthorhombic phase (JCPDS card: 72-0448) was observed [39]. The formation of mixed crystal phases is conducive to the generation of oxygen vacancies.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of MoOx-M and com MoO3.

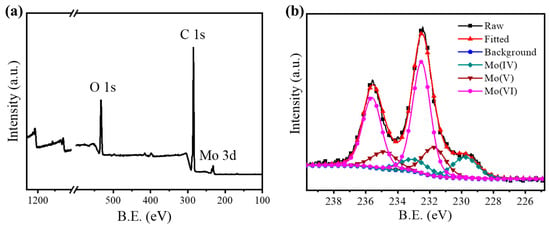

Furthermore, the surface elemental states of the samples calcined at different temperatures, together with com MoO3, were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Figure 3 and Figure S1). For the Mo 3d core-level spectrum of MoOx-700 (Figure 3b), the raw data consisted of multiple peaks, indicating the presence of different chemical states, which then could be deconvoluted into three groups. The two main deconvoluted peaks observed at 232.5 and 235.6 eV can be attributed to the Mo 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 states of Mo(VI), respectively [40]. In addition to the main peaks of Mo(VI), two smaller groups of peaks, centered at 231.8, 234.9, 229.7, and 232.8 eV, were resolved, corresponding to the 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 components of Mo in the IV and V oxidation states, respectively [41]. In the meantime, deconvolution of the raw data for the samples calcined at lower temperatures, along with com MoO3, was performed (Figure S1). For com MoO3 and the samples calcined at 400 °C, 500 °C, and 600 °C, Mo species in pentavalent and hexavalent states could be deconvoluted. For the sample calcined at 650 °C, Mo species in the tetravalent state could also be deconvoluted, in addition to Mo(V) and Mo(VI). Along with this, the Mo species in lower oxidation states increase significantly with increasing calcination temperature (Table S1). The detection of Mo elements with lower oxidation state might be ascribed to the generation of oxygen vacancies [42], which would be beneficial for aerobic oxidative reactions.

Figure 3.

(a) the XPS spectrum of MoOx-700, (b) Mo 3d core-level spectrum of MoOx-700.

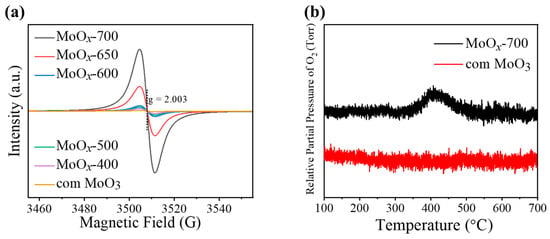

To more directly confirm the presence of oxygen vacancies, electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra of com MoO3 and MoOx-M were recorded under atmospheric conditions (Figure 4a). For com MoO3, no clear ESR signal was detected, suggesting that any unpaired electrons, if present, are below detectable or significant levels [43]. For MoOx calcined at different temperatures, the ESR signal at g = 2.003 increases significantly with increasing calcination temperature, indicating the effective loss of lattice oxygen at higher temperatures. Here, MoOx-700 exhibits the most prominent peak, confirming the presence of abundant oxygen vacancies within its crystal lattice [44]. Additionally, oxygen temperature-programmed desorption (O2-TPD) measurements were carried out for both MoOx-700 and com MoO3 (Figure 4b). While no notable peaks were observed for com MoO3, MoOx-700 showed O2 evolution at relatively lower temperatures, suggesting that the pre-existing oxygen vacancies in the sample can effectively adsorb O2 molecules from air [45]. Such a capability would enhance the catalyst’s performance in aerobic oxidation reactions.

Figure 4.

(a) ESR analyses of com MoO3 and MoOx-M; (b) O2-TPD analyses of com MoO3 and MoOx-700.

2.2. Sulfur Removal with Different Catalysts

The constructed samples served as efficient catalysts for the oxidation of refractory sulfides into their corresponding sulfones, which are insoluble in oil, thus offering a novel approach to realize deep desulfurization of fuel oils. To investigate the effect of calcination temperature on the ODS performance, five catalysts calcined at different temperatures were synthesized and subsequently applied to the ODS procedure. Here, the sulfur removals of all as-prepared MoOx samples and com MoO3 are summarized in Table 1. For com MoO3, a sulfur removal of only 8.9% was achieved, implying its poor catalytic oxidation performance. Then, sulfur removal of MoOx calcined at lower temperatures was measured. Here, sulfur removal increases slightly, which might be ascribed to its structural similarity to com MoO3. According to previous studies, the crystal structure of MoOx undergoes significant changes at higher temperatures. Correspondingly, a noticeable increase in sulfur removal was observed. For MoOx-700, a sulfur removal of 100% was achieved after 4 h of reaction using air directly as the oxidant, indicating the thorough removal of refractory sulfides. The increase in sulfur removal might be ascribed to the generation of oxygen vacancies at higher temperatures.

Table 1.

Sulfur removals of all as-prepared MoOx.

For most reported ODS systems employing Mo-oxide-based catalysts, TBHP [46,47] or H2O2 [48,49] is typically used as an oxidant (Table 2). The reaction temperatures achieved with these peroxide-based oxidants are often lower than those obtained when O2 is used as the oxidant. However, these temperatures are still relatively high for large-scale applications, which may pose an explosion risk due to the instability of large amounts of liquid peroxide-based oxidants. Thus, O2, readily available from air at almost no cost, is considered as an ideal oxidant for the ODS process. Compared with other aerobic oxidative desulfurization systems employing Mo-oxide-based catalysts (Table 2) [50,51,52,53], this reaction system operates at a lower reaction temperature while exhibiting superior recyclability, highlighting its promising potential for practical applications.

Table 2.

Comparisons of reaction conditions for different Mo-oxide-based catalysts.

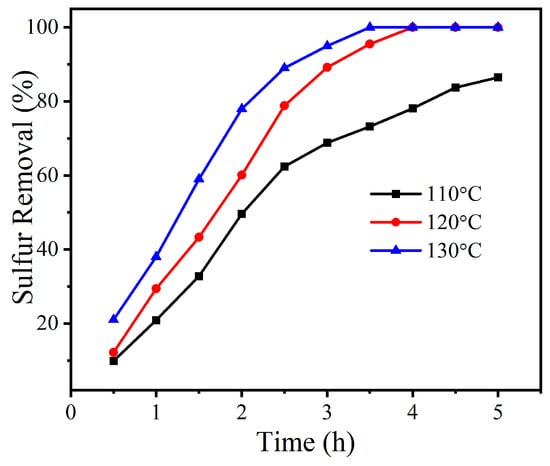

Subsequently, the sulfur removal at different reaction temperatures was evaluated under atmospheric pressure (Figure 5). The sulfur removal performed at a lower reaction temperature (110 °C) was far from achieving deep desulfurization, resulting in only 82.5% sulfide removal after 5 h of reaction. With the increase in reaction temperature, an enhancement in sulfur removal was observed. At 120 °C, thorough removal (100%) of refractory DBT was achieved within a shorter reaction time of 4 h. By continuously increasing the reaction temperature to 130 °C, the time required for 100% sulfur removal was shortened to 3.5 h. The above experimental observation could be attributed to an increase in the reaction rate constant at higher temperatures. Finally, considering the cost-saving requirements of industrial applications, 120 °C was selected as the optimal reaction temperature. Compared with the harsh conditions of conventional HDS (T > 380 °C, P > 80 atm), both the reaction temperature and pressure required in this work are significantly reduced.

Figure 5.

Desulfurization activity for DBT at different reaction temperatures using MoOx-700 as catalyst. Reaction conditions: m(catalyst) = 0.01 g, v(air) = 100 mL/min, T = 120 °C, V(oil) = 20 mL.

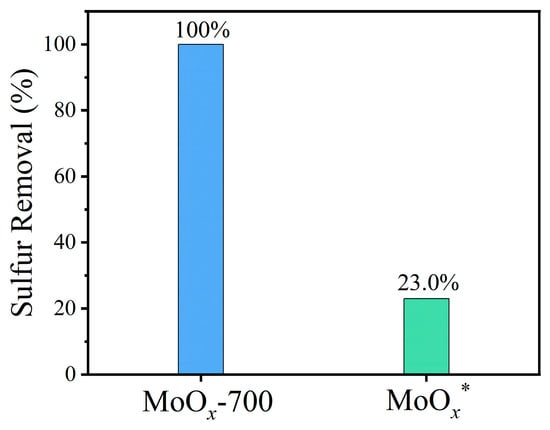

To gain a deeper understanding of the essential role of oxygen vacancies, the MoOx-700 catalyst with the highest catalytic activity was further calcined under a high-purity O2 atmosphere. The resulting light-yellow product was designated as MoOx*. The catalytic aerobic oxidative desulfurization performance of MoOx-700 and MoOx* was then evaluated under the same reaction conditions. As shown in Figure 6, MoOx* achieved only 23.0% sulfur removal after 4 h of reaction. The sharp decline in activity is attributed to the filling of oxygen vacancies during calcination in a high-purity O2 atmosphere at elevated temperatures. Subsequently, UV–visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV–vis DRS) was performed for both MoOx-700 and MoOx* (Figure S2a). The absorption peaks in the visible-light region disappeared after calcination, corresponding to an increase in the bandgap from 1.16 eV to 2.81 eV (Figure S2b). This bandgap widening can be ascribed to the elimination of oxygen vacancies [54], which in turn leads to a significant decrease in catalytic aerobic oxidation performance.

Figure 6.

Sulfur removal of DBT using MoOx-700 and MoOx* as catalysts under the same reaction conditions. Reaction conditions: m(catalyst) = 0.01 g, v(air) = 100 mL/min, T = 120 °C, V(oil) = 20 mL, t = 4 h.

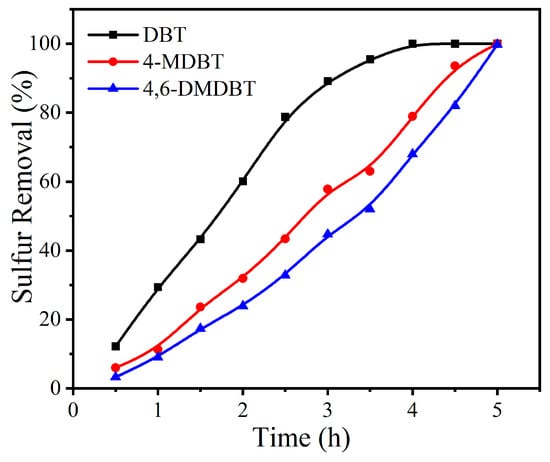

Considering the presence of various refractory sulfides in fuel oils, the sulfur removal of different sulfides needs to be investigated using MoOx-700 as catalyst under the same reaction conditions (Figure 7). Here, DBT, 4-methyl-dibenzothiophene (4-MDBT), and 4,6-dimethyl-dibenzothiophene (4,6-DMDBT) were selected as representative sulfur compounds owing to their known difficulty in traditional desulfurization procedure. In this reaction system, sulfur removal decreased in the order of DBT > 4-MDBT > 4,6-DMDBT. After reaction for 4 h, sulfur removals of 92.8% and 90.5% were achieved for 4-MDBT and 4,6-DMDBT, respectively. The reactivity of sulfides is often influenced by both the electron cloud density on S atoms and the steric hindrance effect, the latter of which affects the efficient contact between S atoms and reactive oxygen species. For these sulfides, the electron cloud densities on the S atoms are 5.758, 5.759, and 5.760 for DBT, 4-MDBT, and 4,6-DMDBT, respectively, showing only slight differences among them [55]. Thus, the presence of additional methyl groups in 4-MDBT and 4,6-DMDBT would be responsible for the decrease in sulfur removal [56]. However, by continuously prolonging the reaction time to 5 h, complete removal of sulfides was also achieved for both 4-MDBT and 4,6-DMDBT, which might be attributed to the continuously supplied oxidant from air. Compared to ODS processes using H2O2 or TBHP as the oxidant, the oxidant employed in this work can be supplied continuously at negligible cost and with a lower risk of explosion [57], implying its potential suitability for practical applications.

Figure 7.

Sulfur removal of DBT, 4-MDBT, and 4,6-DMDBT using MoOx-700 as catalyst under the same reaction conditions. Reaction conditions: m(catalyst) = 0.01 g, v(air) = 100 mL/min, T = 120 °C, V(oil) = 20 mL.

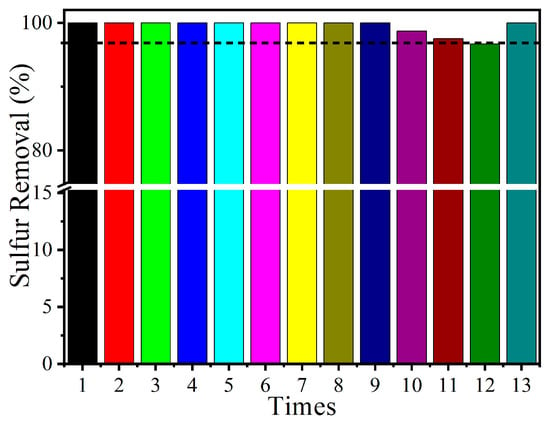

The recyclability and renewability of the prepared catalyst are two additional key properties that need to be evaluated before practical application (Figure 8). After each single reaction, the cleaned oil phase was separated. The remaining catalyst was then dried in an oven, after which fresh oil was added along with the dried catalyst to start the subsequent run. Sulfur removal shows no obvious decrease during the initial 9 cycles. Even after being recycled 12 times, sulfur removal of over 95.0% could still be obtained, indicating excellent cycling performance. To evaluate whether the surface constituents of the catalyst underwent significant changes, XPS analyses of the fresh and used catalysts were conducted (Table 3). Here, the Mo element with different valence shows no obvious variation. Moreover, the Raman and XRD analyses of the recovered catalyst were conducted (Figure S3). Here, no obvious variation in the spectra was observed, indicating the stability of the synthesized catalyst. Thus, we speculate that the accumulated oxidized sulfone on the catalyst surface might hinder efficient contact among the catalytic sites, the oxidant, and the substrate, ultimately leading to a decrease in sulfur removal. Then, the separated catalyst phase was washed several times with diethyl ether and dried for the subsequent run. Here, a sulfur removal of 100% could be achieved again. The above results indicate that the catalyst prepared in this study exhibits both outstanding recyclability and renewability, further demonstrating its practical applicability.

Figure 8.

Recycling performance of MoOx-700 in DBT removal. Reaction conditions: m(catalyst) = 0.01 g, v(air) = 100 mL/min, T = 120 °C, V(oil) = 20 mL, t = 4 h.

Table 3.

Contents of different forms of Mo in the near-surface layers of catalysts.

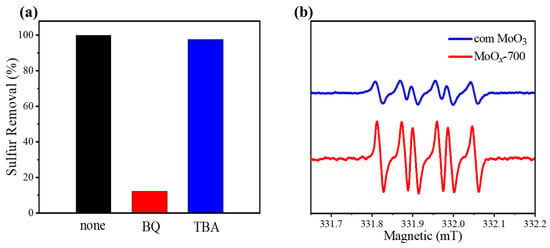

To identify the types of reactive oxygen species generated during the desulfurization process, radical quenching experiments were performed (Figure 9a). Here, p-benzoquinone (BQ) and tert-butanol (TBA) were employed as radical scavengers for O2−• and •OH, respectively [58]. When BQ was introduced into the model oil, the sulfur removal sharply decreased to 12.3%. In contrast, no significant decrease in sulfur removal was observed upon the addition of TBA. The above results illustrate that O2−• would be the dominant radicals generated during the desulfurization procedure. To further confirm the above conclusion, ESR measurements were carried out (Figure 9b), in which 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) was used as a radical scavenger. For MoOx-700, a typical strong signal of DMPO-O2−• with six peaks could be observed, indicating the abundant generation of O2−• during the desulfurization process [59]. In addition, for com MoO3, a typical DMPO-O2−• signal could also be identified, but it exhibited a significantly weaker intensity, which is consistent with its sharply decreased catalytic oxidation performance. Taking the above together, we can speculate that the refractory DBT in the oil phase is first oxidized to sulfoxide and then ultimately to polar sulfone. The generated sulfone is subsequently precipitated on the surface of the catalyst due to its obviously changed polarity, realizing the efficient removal of sulfide from the oil phase.

Figure 9.

(a) selective quenching experiments for the removal of DBT with different captures using MoOx-700 as catalyst. Reaction conditions: m(catalyst) = 0.01 g, v(air) = 100 mL/min, T = 120 °C, V(oil) = 20 mL, t = 4 h, n(DBT) = n(BQ) = n(TBA). (b) ESR spectra of different aerobic oxidation systems.

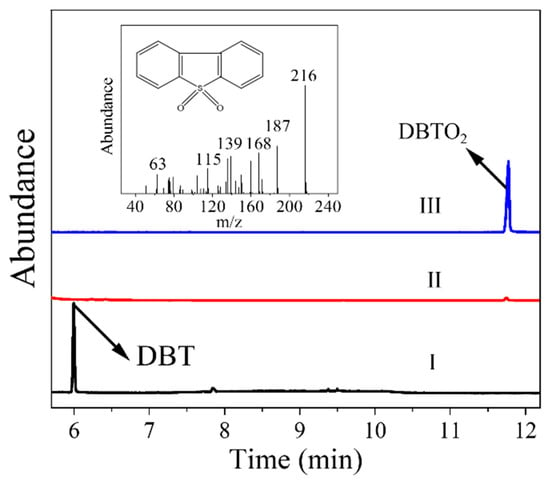

To confirm the successful oxidation of DBT to DBTO2 and the spontaneous separation of sulfone from the oil phase, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was employed to analyze the sulfide species in the fresh oil phase, the oxidized oil phase, and the extract solution of the reacted catalyst phase (Figure 10). Initially, the prominent peak observed in the fresh oil phase corresponds to DBT, which disappears in the oxidized oil phase, indicating the successful oxidation of DBT in this desulfurization system. Meanwhile, a distinct peak is observed in the extract solution of the reacted catalyst phase, whose m/z value is 216, corresponding to the oxidized DBTO2 [60]. However, this peak is negligible in the oxidized oil phase. Thus, based on the above experimental observations, DBT present in the oil phase was oxidized by the generated O2−• to DBTO2 with strong polarity, which subsequently precipitated on the surface of the catalyst, achieving the successful removal of sulfide from the oil phase finally.

Figure 10.

GC-MS analyses of I: fresh oil, II: oxidized oil phase, III: re-extracted catalyst phase.

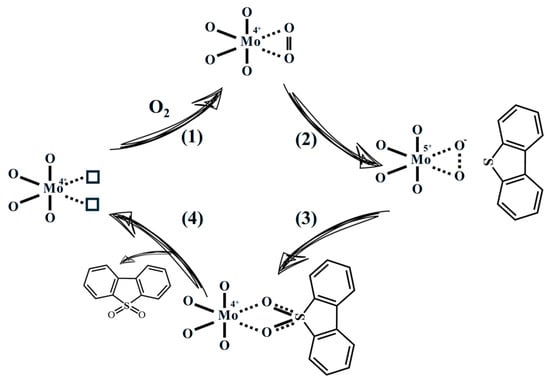

Based on the above observations, the potential reaction procedures were proposed. As the sulfur removal increases sharply with catalysts containing Mo(IV) species, we speculate that the Mo(IV) species act as the main catalytic sites (Scheme 1), while the Mo(V) species act as complementary catalytic sites (Scheme S1). The reactions occurring on Mo(IV) species may proceed as follows. In step (1), O2 molecules are effectively adsorbed onto the catalyst surface owing to the strong adsorption capability of the oxygen--vacancy sites. In step (2), electrons from the Mo(IV)–Vo centers are transferred to the adsorbed O2, generating Mo(V)–O2− superoxide species. Subsequently, the resulting superoxide species oxidize DBT to the corresponding sulfone (step (3)), while the oxygen vacancies are simultaneously regenerated (step (4)). Thus, the oxidation process could proceed continuously, enabling efficient removal of refractory sulfides. In addition, the detailed reaction procedures at the Mo(V) sites are provided in the “Supporting Information”. As the polarity of sulfides in the oil phase sharply increases, they would precipitate and aggregate together with the catalyst phase, realizing deep desulfurization finally.

Scheme 1.

Possible reaction procedure at Mo(IV) sites during the catalytic aerobic oxidative desulfurization procedure.

3. Materials and Methods

The details regarding the preparation of model fuel oils, the characterization techniques used for the catalysts, and the heating program of the chromatographic analysis are provided in the Supporting Information.

3.1. Reagents

Ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate (A.R.), tert-butanol (A.R.), p-benzoquinone (A.R.), diethyl ether (99%), carbon tetrachloride (A.R.), dodecane (A.R.), hexadecane (A.R.), and commercially available molybdenum trioxide (MoO3, A.R.) in the form of a white crystalline powder were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Dibenzothiophene (DBT, 98%), 4-methyl-dibenzothiophene (4-MDBT, 98%), and 4,6-dimethyl-dibenzothiophene (4,6-DMDBT, 97%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China). The reagents were applied directly in their received state, without subsequent purification steps.

3.2. The Synthesis of MoOx-M Catalyst

Initially, an appropriate amount of ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate was dissolved in high-purity water. The solution was then heated at 55 °C to evaporate the water and simultaneously obtain a white solid. The resulting recrystallized solid was subsequently calcined in a tube furnace under a high-purity N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 5 °C/min up to 700 °C and maintained at this temperature for 2 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, a dark brown product was obtained and denoted as MoOx-700. Similarly, the products calcined at other temperatures (M°C) were marked as MoOx-M.

3.3. Reaction Conditions for ESR Analyses

For the ESR signal of oxygen vacancies, the catalyst was directly loaded into a quartz tube, which was then placed in the resonant cavity of the spectrometer. The bottom of the quartz tube was positioned at the center of the cavity to ensure optimal signal detection. After positioning, the instrument was tuned and the ESR spectrum was recorded under ambient conditions.

For the ESR signal of reactive oxygen species generated under reaction conditions, the catalyst and DMPO (used as a spin-trapping agent) were dispersed in methanol. Then, an appropriate amount of the mixture was transferred into a quartz tube, which was subsequently placed in the ESR resonant cavity for radical detection.

3.4. The Aerobic Oxidative Desulfurization Procedure

The oxidation procedure was carried out using O2 from air as an oxidant. The reaction was performed in a three-necked flat-bottom flask. Initially, 0.01 g of fresh catalyst and 20 mL of model oil were added into the flask. The sulfur concentrations of DBT, 4-MDBT, and 4,6-DMDBT were set to 500 ppm, 200 ppm, and 200 ppm, respectively. Subsequently, the flask was immersed in an oil bath maintained at a specific temperature. Once the reaction temperature reached stability, air was introduced at a flow rate of 100 mL/min. In addition, a water condenser was connected to minimizing oil evaporation. The sulfur concentration of the model oil was determined every 0.5 h using gas chromatography. The sulfur removal was then calculated according to the following equation: Sulfur removal (%) = (C0 − Ct)/C0 × 100%. This approach has been widely adopted in related studies. Here, C0 and Ct represent the initial and time-dependent sulfur concentrations, respectively.

4. Conclusions

In summary, MoOx catalysts with oxygen vacancies were successfully prepared via simple calcination under an inert atmosphere. The physicochemical properties of the synthesized catalysts were characterized using Raman, XRD, XPS, ESR, and O2-TPD analyses. The above results indicate the successful construction of MoOx with oxygen vacancies. The sulfur removal of 100% could be obtained for DBT, 4-MDBT, and 4,6-DMDBT at relatively moderate reaction conditions compared to traditional HDS reaction. The efficient desulfurization of refractory sulfides could be attributed to the effective adsorption and activation of O2 from air at the reduced Mo sites. The radical scavenging experiments, ESR measurements, and GC-MS analyses collectively confirm the generation of O2−• and the successful oxidation of refractory sulfides to their corresponding sulfones. Due to the insoluble sulfone accumulating on the surface of the catalyst, it needs to be regenerated through a simple washing process. Then, 100% sulfur removal could be gained again. Considering the facile synthesis procedure and the excellent aerobic ODS performance exhibited in this study, the MoOx catalysts are regarded as promising candidates for practical applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121146/s1, Experimental section. Figure S1. Mo 3d core-level spectra of (a) com MoO3, (b) MoOx-400, (c) MoOx-500, (d) MoOx-600, and (e) MoOx-650. Figure S2: (a) UV-Vis DRS spectra of MoOx-700 and MoOx*, (b) estimated band gaps of the MoOx-700 and MoOx*. Figure S3. (a) Raman and (b) XRD analyses of fresh and recovered MoOx-700. Table S1. Contents of Mo species in the near-surface regions of com MoO3 and catalysts calcined at different temperatures. Scheme S1. Possible reaction procedure at Mo(V) sites during the catalytic aerobic oxidative desulfurization procedure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W. and X.Y.; methodology, M.M. and X.Y.; software, Y.Z. (Ying Zhang); validation, C.W., J.L. and M.Z.; formal analysis, C.W., Y.Z. (Ying Zhang) and Y.Z. (Yijin Zhang); investigation, C.W., Y.L., M.M. and X.Y.; resources, C.W.; data curation, J.C., J.L. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W. and X.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.W.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, C.W. and X.Y.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Thanks for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22108105), the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (No. 225RC748), and the Science and Technology Plan Project of Changzhou City (CJ20252007).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, J.-W.; Lee, T.-H. A comparative study of combustion characteristics for the evaluation of the feasibility of crude bioethanol as a substitute for marine fuel oil. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, X. Research the synergistic carbon reduction effects of sulfur dioxide emissions trading policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zou, Y.; Ding, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Effects of attractive electrostatic interactions on sulfur dioxide capture by functionalized deep eutectic solvents with abundant negative sites. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 591, 165030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.; Rangarajan, S.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J.; Mavrikakis, M.; Lauritsen, J.V. Site-dependent reactivity of MoS2 nanoparticles in hydrodesulfurization of thiophene. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liang, S.; You, F.; Cheng, H.; Zheng, P.; Wu, P.; Liu, J. Regulating the electron affinity of NiMo/Al2O3 to enhance ultra-deep hydrodesulfurization of diesel. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 2025, 378, 125565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M.F.; Zaid, H.F.M.; Kait, C.F.; Jumbri, K.; Yuan, L.C.; Rajasuriyan, S. Futuristic advance and perspective of deep eutectic solvent for extractive desulfurization of fuel oil: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 306, 112870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, R.A.; Bhaduri, B.; Verma, N. Graphitic carbon nitride-immobilized bacterial endospores: Combined adsorptive-and bio-desulfurization of liquid fuels. Mater. Lett. 2024, 361, 136117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S.A.; Lateef, S.A. Review of adsorptive desulfurization process: Overview of the non-carbonaceous materials, mechanism and synthesis strategies. Fuel 2021, 294, 120273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, A.; Merican, Z.M.A.; Musa, S.G. Recent advances in catalytic oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil—A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 112, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ding, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhang, M.; Li, H. The Facile Construction of Defect-Engineered and Surface-Modified UiO-66 MOFs for Promising Oxidative Desulfurization Performance. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.S.; Hamasalih, L.O.; Hama Aziz, K.H.; Omer, K.M.; Shafiq, I. Oxidative desulfurization of real high-sulfur diesel using dicarboxylic acid/H2O2 system. Processes 2022, 10, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, W.N.A.W.; Bakar, W.A.W.A.; Ali, R.; Kadir, A.A.A. Optimization of oxidative desulfurization of Malaysian Euro II diesel fuel utilizing tert-butyl hydroperoxide–dimethylformamide system. Fuel 2015, 161, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wei, D.; Wang, W.; Bai, L.; Chen, H. Efficient aerobic oxidative desulfurization over Co–Mo–O bimetallic oxide catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 2915–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Tian, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Mo–V/g-C3N4 with strong electron donating capacity and abundant oxygen vacancies for low-temperature aerobic oxidative desulfurization. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 11461–11464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, W.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Luo, J.; Yang, W.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, W.; Li, H. Pt nanoparticles encapsulated on V2O5 nanosheets carriers as efficient catalysts for promoted aerobic oxidative desulfurization performance. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Paricio, A.; Santiago-Portillo, A.; Navalón, S.; Concepción, P.; Alvaro, M.; Garcia, H. MIL-101 promotes the efficient aerobic oxidative desulfurization of dibenzothiophenes. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Z.; Yin, S.; Wu, P.; Xun, S.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, H. Light irradiation induced aerobic oxidative deep-desulfurization of fuel in ionic liquid. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 99927–99934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Xun, S.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, W. Atomic-layered α-V2O5 nanosheets obtained via fast gas-driven exfoliation for superior aerobic oxidative desulfurization. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 2612–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, F.; Allahyari, S.; Rahemi, N.; Hussain, M. Ultrasound-assisted aerobic desulfurization of fuel oil using plasma-treated MoO3-boron nitride catalysts. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhao, S.; Wu, P.; Chong, Y.; Li, A.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, G.; Jin, X.; Qiu, Y. Engineering cobalt oxide with coexisting cobalt defects and oxygen vacancies for enhanced catalytic oxidation of toluene. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 4906–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simlandy, A.K.; Bhattacharyya, B.; Pandey, A.; Mukherjee, S. Picosecond electron transfer from quantum dots enables a general and efficient aerobic oxidation of boronic acids. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5206–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Yi, W.; Liu, J.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Yang, H.; Xi, G. Large-scale synthesis of ultrathin tungsten oxide nanowire networks: An efficient catalyst for aerobic oxidation of toluene to benzaldehyde under visible light. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 13545–13551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sádaba, I.; Granados, M.L.; Riisager, A.; Taarning, E. Deactivation of solid catalysts in liquid media: The case of leaching of active sites in biomass conversion reactions. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4133–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Liu, Q.; Liu, C.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Cui, S.; Zang, G. Unraveling the role of oxygen vacancies in metal oxides: Recent progress and perspectives in NH3-SCR for NOx removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 487, 150714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cen, W.; Cheng, Y. Birnessite as a highly efficient catalyst for low-temperature NH3-SCR: The vital role of surface oxygen vacancies. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 14606–14615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolmson, S.J.; Meek, S.J.; Sattely, E.S.; Schrock, R.R.; Hoveyda, A.H. Highly efficient molybdenum-based catalysts for enantioselective alkene metathesis. Nature 2008, 456, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Kuwahara, Y.; Yamashita, H. Development of defective molybdenum oxides for photocatalysis, thermal catalysis, and photothermal catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 8466–8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Xie, L.; Gu, C.; Zheng, W.; Tu, Y.; Yu, H.; Huang, B.; Wang, L. The nature of active sites of molybdenum sulfide-based catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 506, 215715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Chin, Y.-H.C. Catalytic Consequences of Protons in Methanol Oxidative Dehydrogenation on Molybdenum-Based Polyoxometalate Clusters. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 6674–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lu, S.; Feng, Y.; Fu, L.; Feng, L. Insights into the confinement effect of NiMo catalysts toward alkaline hydrogen oxidation. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; An, X.; She, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, W.; Li, H.; Jiang, W. Molybdenum-based metal–organic frameworks as highly efficient and stable catalysts for fast oxidative desulfurization of fuel oil. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 326, 124699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Bhattacharjee, J.; Datta, P.; Roy, S. A comprehensive review of the oxidation states of molybdenum oxides and their diverse applications. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 7, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, I.A.; Datta, R.S.; Ou, J.Z.; Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Sriram, S.; Daeneke, T.; Kalantar-zadeh, K. Molybdenum oxides–from fundamentals to functionality. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Yang, M.-Q.; Fu, X.; Zhang, N.; Xu, Y.-J. Defective TiO2 with oxygen vacancies: Synthesis, properties and photocatalytic applications. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 3601–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.D.; Moura, J.V.; Pinheiro, G.S.; Araujo, J.F.; Gusmão, S.B.; Viana, B.C.; Freire, P.T.; Luz-Lima, C. Co-doped α-MoO3 hierarchical microrods: Synthesis, structure and phonon properties. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 27778–27788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, E.; Grimblot, J.; Kasztelan, S. Study of oxidic and reduced alumina-supported molybdate and heptamolybdate species by in situ laser Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 6642–6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterle, M.; Mestl, G. Raman spectroscopy of molybdenum oxides Part II. Resonance Raman spectroscopic characterization of the molybdenum oxides Mo4O11 and MoO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, E.; Modreanu, M.G.; Mohebbi, E.; Mencarelli, D.; Stipa, P.; Laudadio, E.; Pierantoni, L. First-principles calculation of MoO2 and MoO3 electronic and optical properties compared with experimental data. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lu, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, X. Pseudocapacitive MoOx anode material with super-high rate and ultra-long cycle properties for aqueous zinc ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 882, 115033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Su, J.; Zhao, X.; Pan, X. Inhibition of phase transition from δ-MnO2 to α-MnO2 by Mo-doping and the application of Mo-doped MnO2 in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 30663–30669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.D.; de Carvalho, T.C.; Mendoza, C.D.; da Costa, M.E.M.; Pinheiro, G.d.S.; Luz-Lima, C.; Silva, B.G.; Sommer, R.L.; Araujo, J.F. Magnetic transition in MoO3: Influence of Mo5+/Mo6+ ratios on paramagnetic to diamagnetic behavior. Solid State Sci. 2025, 162, 107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, M.T.; Chai, L.; Helander, M.G.; Tang, W.M.; Lu, Z.H. Transition metal oxide work functions: The influence of cation oxidation state and oxygen vacancies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4557–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liang, C.; Xun, S.; Yu, Z.; Wu, C.; He, M.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Oxygen vacancy regulation strategy in V-Nb mixed oxides catalyst for enhanced aerobic oxidative desulfurization performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 641, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, R.; Huo, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L. Formation, detection, and function of oxygen vacancy in metal oxides for solar energy conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2109503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, J.; Yang, L.; He, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, R.; He, H. Oxygen vacancies induced by transition metal doping in γ-MnO2 for highly efficient ozone decomposition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 12685–12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, X.-M.; Yang, X.-F.; Jiao, M.-G.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, M.-H.; Wang, D.-H.; Bu, X.-H. Electronic structure of heterojunction MoO2/g-C3N4 catalyst for oxidative desulfurization. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2018, 238, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astle, M.A.; Rance, G.A.; Loughlin, H.J.; Peters, T.D.; Khlobystov, A.N. Molybdenum dioxide in carbon nanoreactors as a catalytic nanosponge for the efficient desulfurization of liquid fuels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1808092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Miao, Q.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Duan, Y.; Yan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, S. Fabrication of various morphological forms of a g-C3N4-supported MoO3 catalyst for the oxidative desulfurization of dibenzothiophene. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 18745–18755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W.-H.; Bao, M. Improving the stability of subnano-MoO3/meso-SiO2 catalyst through amino-functionalization. Funct. Mater. Lett. 2018, 11, 1850003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zhao, X.; Bai, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, H.; Yang, L.; Liang, Y.; Bai, L.; Yang, H. Co, N-codoped MoOx nanoclusters on graphene derived from polyoxometalate for highly efficient aerobic oxidation desulfurization of diesel. J. Catal. 2023, 428, 115186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, L.; Bai, L.; Wei, D.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Chen, H. MoOx nanoclusters decorated on spinel-type transition metal oxide porous nanosheets for aerobic oxidative desulfurization of fuels. Fuel 2023, 334, 126753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Wu, Y.; Shao, S.; Liang, S.; You, F.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhu, W.; Liu, J. Regulating the metal-support interaction of MoO3/LaTiOx to enhance ultra-deep aerobic oxidative desulfurization of diesel. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xun, S.; Yang, B.; Zhu, L.; He, M.; Hua, M.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Heterostructure MoO3/g-C3N4 efficient enhances oxidative desulfurization: Rational designing for the simultaneously formation of MoO3 nanoparticle and few layers g-C3N4. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Miao, R.; Huan, T.D.; Mosa, I.M.; Poyraz, A.S.; Zhong, W.; Cloud, J.E.; Kriz, D.A.; Thanneeru, S.; He, J. Mesoporous MoO3–x material as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reactions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, S.; Wu, C.; Tang, L.; Yuan, M.; Chen, H.; He, M.; Zhu, W.; Li, H. One-pot in-situ synthesis of coralloid supported VO2 catalyst for intensified aerobic oxidative desulfurization. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 56, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraei, S. Assessment of reaction parameters in the oxidative desulfurization reaction. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 15373–15393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, I.; Shafique, S.; Akhter, P.; Ishaq, M.; Yang, W.; Hussain, M. Recent breakthroughs in deep aerobic oxidative desulfurization of petroleum refinery products. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 294, 125731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, H.; Yesire, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Li, H. Amphiphilic Catalysts Comprising Phosphomolybdic Acid Fastened on MIL-101 (Cr): Enabling Efficient Oxidative Desulfurization under Solvent-Free and Moderate Reaction Conditions. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 8553–8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Bai, S.; Ding, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Enhanced oxidative desulfurization activity over NH2-MIL-125 (HAc) through facet modulation by acetic acid and surface modification by amino group. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 653, 159315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Sheng, J.; Yuan, Q.; Su, Y.; Zhu, L.; Dai, C.; Zhao, H. Cross-Linked Polyvinylimidazole Complexed with Heteropolyacid Clusters for Deep Oxidative Desulfurization. Molecules 2024, 29, 4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).