Abstract

The design of efficient catalysts is vital for the application of catalytic oxidation technology in the removal of gaseous pollutants. Herein, a series of MnOx catalysts with the typical Mn2O3 crystal structure was synthesized via the high-temperature pyrolysis method by using Mn-based metal–organic frameworks (Mn-MOFs) with various morphologies as the precursors. The physicochemical properties of these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx samples were investigated by various characterization techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermogravimetry (TG), N2 adsorption–desorption, scanning electron microscope (SEM), and H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR), and their catalytic activity was evaluated for catalytic CO degradation. The results showed that the Mn-MOF with leaf-like morphology, derived MnOx-Leaf, presented the optimal catalytic CO oxidation performance (T98 = 214 °C), stability, and reusability. Characterization results showed that the different Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts possessed different physical–chemical properties. The superior catalytic activity of MnOx-Leaf for CO degradation was ascribed to its large surface area and pore size, better low-temperature redox properties, and high H2 consumption, which promoted the adsorption and activation of the CO and gaseous oxygen molecules, improving CO oxidation. Finally, the possible CO degradation pathway was evaluated by in situ diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DRIFTS), which showed that gaseous CO and O2 were adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst and oxidized to form surface carbon-related species (bicarbonate and carbonate), and finally converted to CO2.

1. Introduction

As a colorless and odorless toxic gas, carbon monoxide (CO) is mainly generated from the incomplete combustion of fuel [1]. It readily combines with hemoglobin, causing oxygen deficiency in the human body and leading to headaches, coma, and even death [2]. Long-term exposure may also damage the cardiovascular and nervous systems. At the same time, it also causes serious harm to the environment, including intensifying air pollution, etc. [3,4]. Therefore, the removal of CO is important for human health and environmental protection, and the construction of a green city. To reduce the emission of gaseous pollutions, such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), oxynitride (NOx), CO, etc., many technologies, including photocatalysis [5,6,7,8], photothermal catalysis [9,10,11,12], catalytic reduction [13,14], catalytic oxidation [15,16,17,18,19], etc., have been proposed in the past several decades. Among the various technologies, catalytic oxidation has been considered the most hopeful technology for gaseous pollution elimination [20]. For catalytic oxidation, its crux lies in the design of efficient catalysts.

The catalysts used for catalytic oxidation can be divided into supported noble metal catalysts and metal oxide catalysts. Although supported noble metal catalysts exhibit excellent catalytic performance for CO oxidation, their high prices and scarcity limit their widespread application. Metal oxide catalysts, due to their low price, being readily available, and outstanding redox properties, have been widely applied for the catalytic degradation of gaseous pollution [21,22]. Although the catalytic performance of metal oxide catalysts is inferior compared to that of supported noble metal catalysts, they have the advantage of being inexpensive and readily available. Therefore, the key relevance of CO oxidation research lies in developing cost-effective metal oxide catalysts that can replace noble metals such as platinum, palladium, and rhodium, currently used for CO conversion in exhaust systems. For instance, Cai et al. [23] prepared a CeO2 catalyst for CO oxidation, and the as-prepared catalysts had a temperature of 100% CO conversion (T100) at 290 °C. Xu et al. [24] synthesized Fe2O3 for CO oxidation, which exhibited a temperature of 90% CO conversion (T90) at 400 °C. Pulleri et al. [25] prepared Mn3O4 catalysts via the precipitation method and the reduction method for CO oxidation. The Mn3O4 prepared via different synthesis methods both presented the CO oxidation performance of T100 = 275 °C. Among the various metal oxide catalysts, MnOx catalysts with the advantages of flexible valence state changes (Mn2+, Mn3+, and Mn4+), abundant surface active oxygen species, and low toxicity have been employed for gaseous pollution elimination [26,27]. For example, Zhang et al. [28] synthesized a battery of MnOx via the co-precipitation method for toluene oxidation. The results showed that the as-prepared MnOx catalysts presented better catalytic performance, great reusability, and stability. Generally, the methods for MnOx catalyst synthesis include the hydrothermal method [29], co-precipitation [30], sol–gel [31], etc.—traditional approaches. However, the MnOx catalysts prepared by traditional methods still face challenges, such as easy agglomeration, uncontrollable structure, and poor mechanical strength, which result in insufficient catalytic activity and stability. Therefore, developing an efficient and controllable preparation method is the key to obtaining highly active MnOx catalysts.

Recently, a new approach for preparing metal oxides or composite metal oxides using metal–organic framework (MOF) materials as precursors and through high-temperature pyrolysis has been widely reported [32,33]. It had been reported that the metal oxides derived from MOFs can precisely inherit the high specific surface area, hierarchical porous structure, and atomically dispersed active sites after pyrolysis due to the designability of their precursors [34,35]. Meanwhile, the precise design of metal oxidation states and crystal forms can be achieved through ligand regulation. Based on these advantages, the MOF-derived method has been extensively employed for metal oxide catalysts preparation. For example, Jiang et al. [36] prepared MnOx catalysts by using Mn-MOFs as the precursors for chlorobenzene oxidation, which displayed excellent catalytic activity. Jiang et al. [37] contrasted the catalytic activity of the MnOx-CeO2 catalyst derived from the MOF-derived method and that prepared by the hydrothermal method in the catalytic degradation of ethyl acetate. It was found that the MOF-derived MnOx-CeO2 catalyst exhibited better ethyl acetate oxidation activity, which was ascribed to the generation of abundant oxygen vacancies and large surface area in the MOF-derived catalysts. Additionally, our previous work [38] also observed that the MOF-derived CuO/CeO2 catalyst exhibited better catalytic performance than that prepared via the impregnation and mechanical mixing method for CO oxidation. Therefore, the MOF-derived method was the optimal synthesis method for the preparation of MnOx catalysts for CO oxidation. However, so far, the influence of MOFs morphology on CO oxidation performance and the CO degradation pathway on MOF-derived MnOx remains unclear.

Herein, a suite of Mn-MOFs with different morphologies was prepared as the precursors to prepare MnOx catalysts, and their catalytic performance was evaluated by catalytic oxidation using CO as the probe molecule. The physical and chemical properties of the as-prepared MOF-derived MnOx catalysts were studied by multiple characterization techniques. The influence of MOFs precursors’ morphologies on the physicochemical properties and the CO oxidation activity was investigated. Meanwhile, the stability and reusability of the MnOx catalysts were also studied. Importantly, the possible CO oxidation pathway over the MOF-derived MnOx catalyst was systematically expounded via the in situ diffuse reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DRIFTS).

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Characterization of the Mn-MOFs Precursors

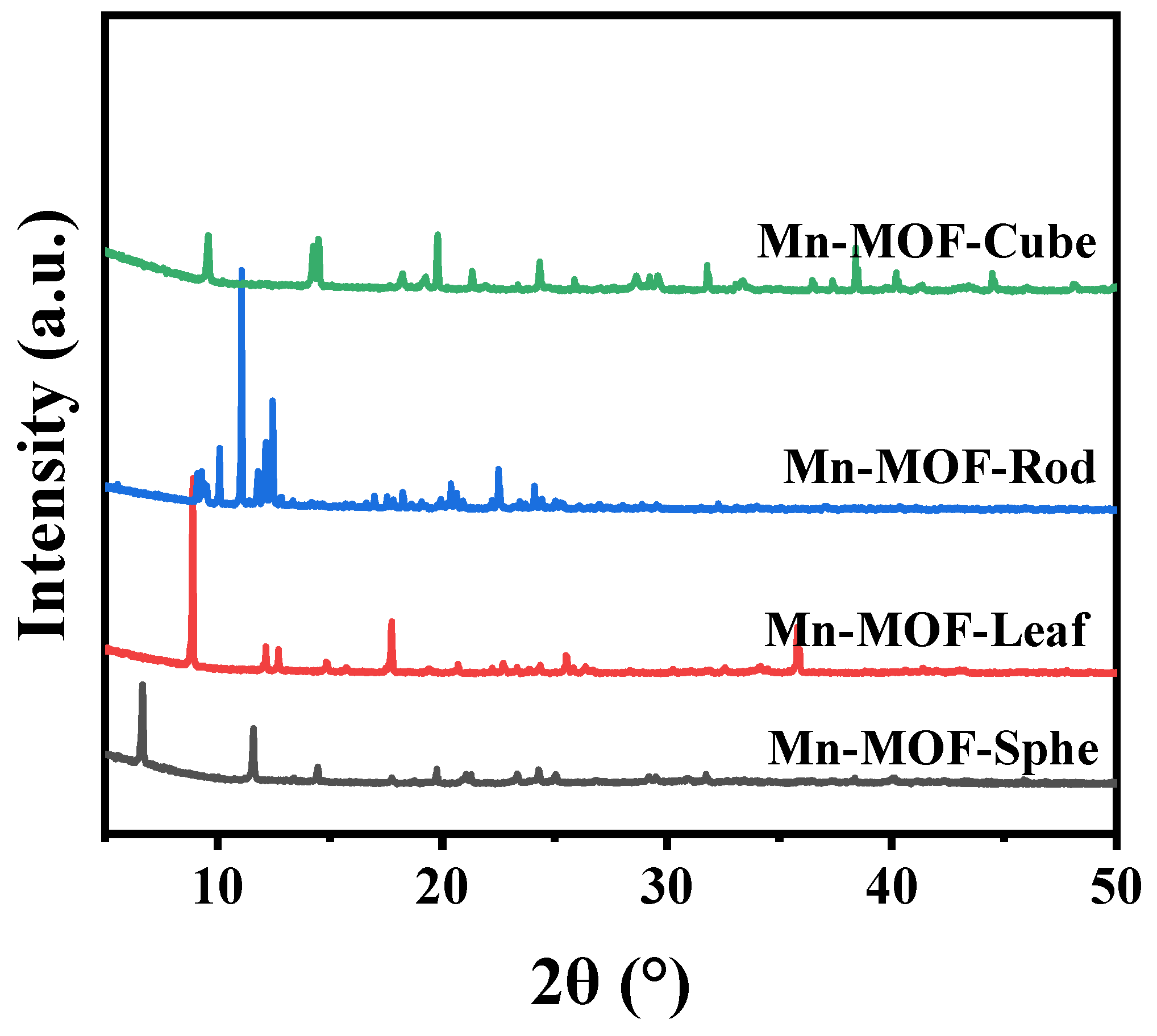

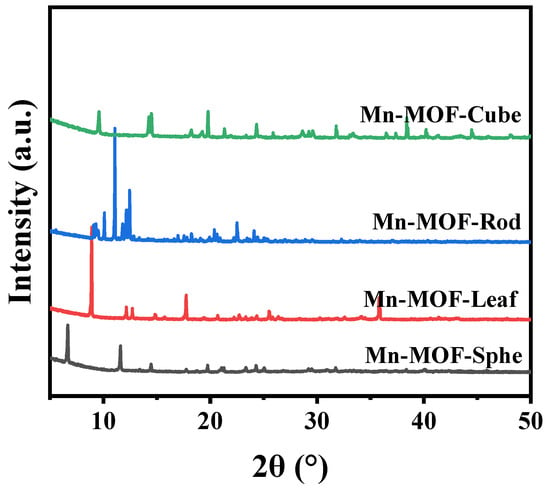

The Mn-MOFs precursors with different morphologies were prepared via the conventional solvothermal method and characterized by many characterization techniques. The Mn-MOFs precursors with spherical, leaf-like, rod-like, and cube-like morphology were named Mn-MOF-Sphe, Mn-MOF-Leaf, Mn-MOF-Rod, and Mn-MOF-Cube, respectively. Firstly, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) was employed to study the crystal structure of these as-prepared Mn-MOFs precursors with different morphologies (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1, all the Mn-MOFs with spherical, leaf-like, rod-like, and cube-like morphology presented the typical XRD peaks of the MOF structure, which were similar to the reported literature [39,40,41,42]. This suggested the successful synthesis of these different morphologies of Mn-MOFs precursors.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the Mn-MOFs with different morphologies.

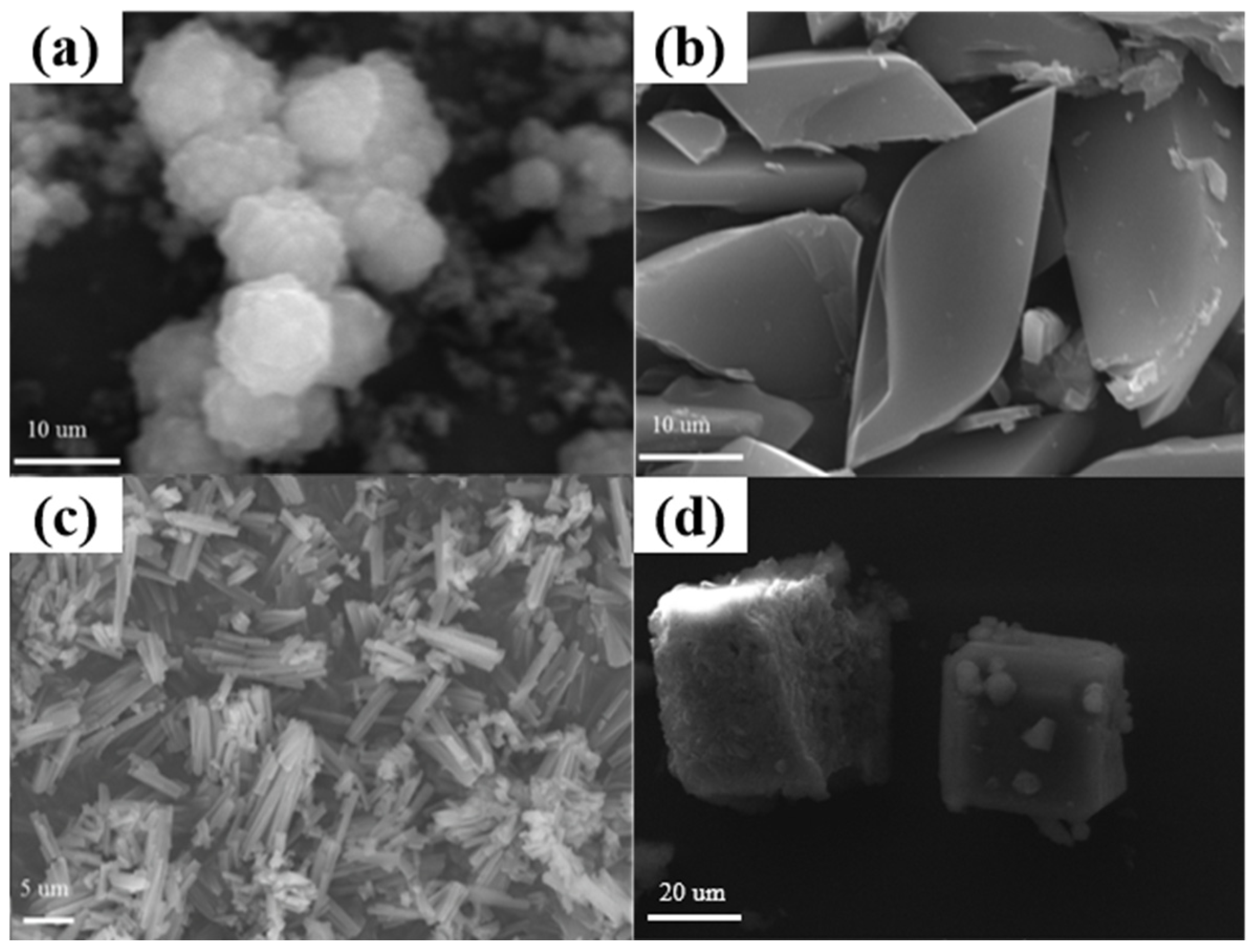

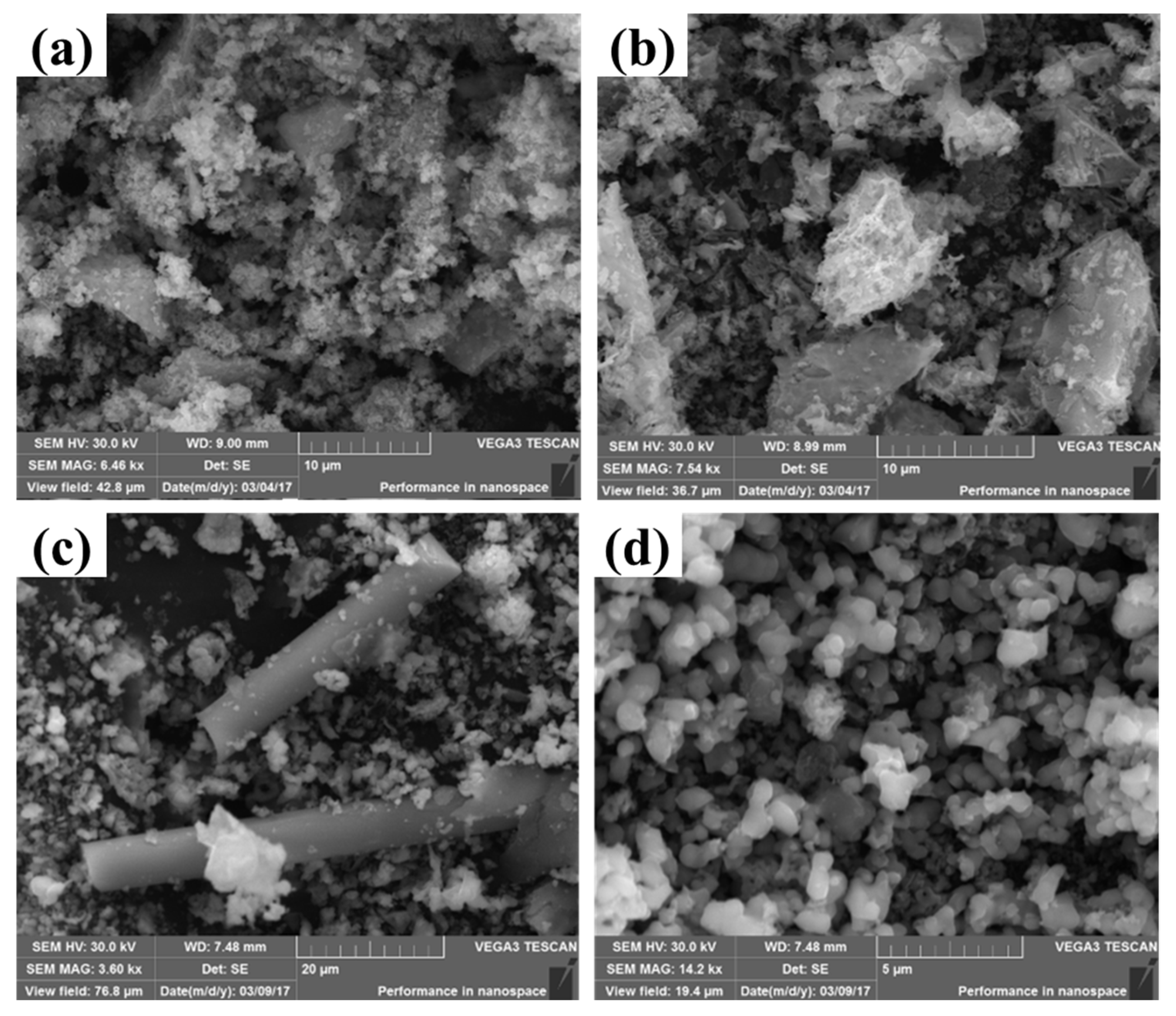

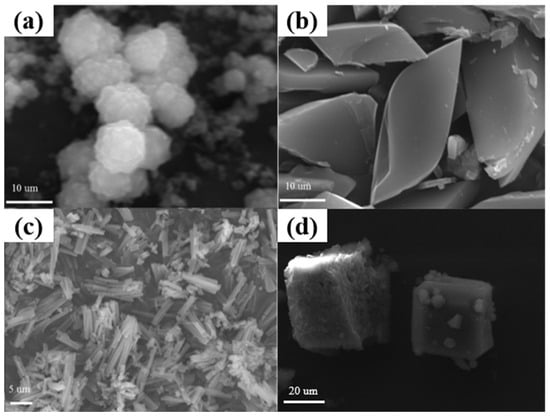

Generally, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is one of the most efficient techniques to distinguish the morphology of a material directly. Therefore, to further confirm the successful preparation of the Mn-MOFs with the specific appearance, the SEM was performed. Figure 2 displayed the SEM images of these Mn-MOF precursors. As shown in Figure 2a–d, the as-prepared Mn-MOF-Sphe, Mn-MOF-Leaf, Mn-MOF-Rod, and Mn-MOF-Cube displayed the spherical, leaf-like, rod-like, and cube-like morphologies, respectively, which also confirmed the successful synthesis of the Mn-MOFs precursors with different morphologies.

Figure 2.

SEM images of the Mn-MOFs with different morphologies: (a) Mn-MOF-Sphe, (b) Mn-MOF-Leaf, (c) Mn-MOF-Rod, and (d) Mn-MOF-Cube.

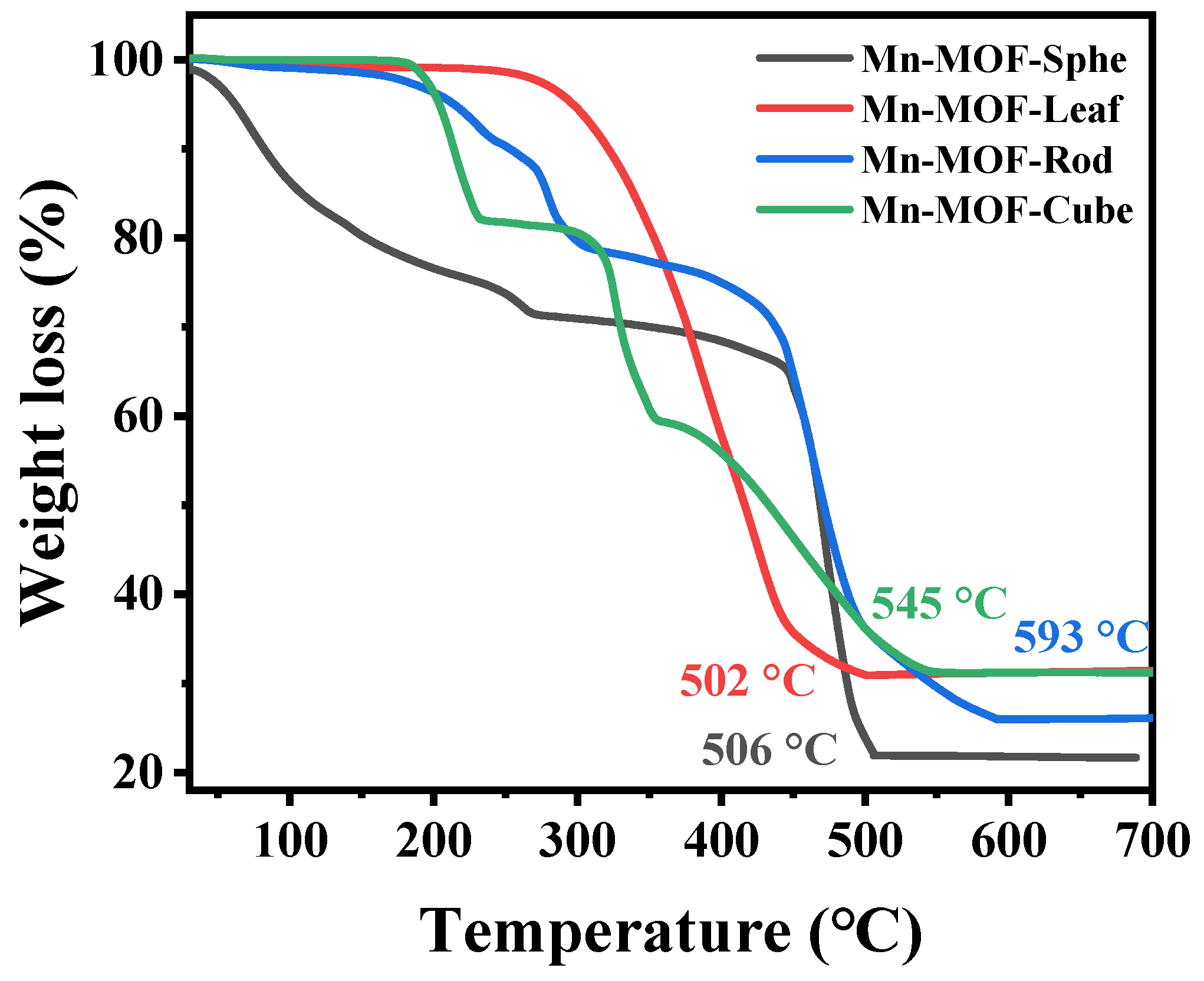

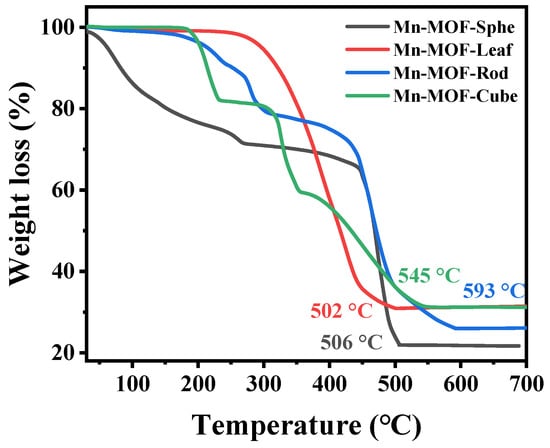

Furthermore, the thermal stability of the as-prepared Mn-MOFs precursors was investigated via a thermal gravimetric (TG) analyzer, and the results are exhibited in Figure 3. As presented in Figure 3, for Mn-MOF-Sphe, the weight loss below 100 °C was attributed to the adsorbed water vapor [43]. The weight loss between 100 and 300 °C was assigned to the evaporation of the residual organic solvent [44]. The sharp weight loss above 450 °C was attributed to the disintegration of the organic linkers, and the frameworks were converted to MnOx [45]. For Mn-MOF-Leaf, only a weight loss could be found between 300 and 500 °C, which was ascribed to the oxidation of the organic ligands. For Mn-MOF-Rod and Mn-MOF-Cube, two weightless staircases were observed in the TG curves. For Mn-MOF-Rod, these two weightless staircases were attributed to the unreacted organic ligands and the combustion of the organic linkers coordinated with the metal clusters, respectively, while for Mn-MOF-Cube, these two weightless staircases were assigned to the loss of residual solvent and the decomposition of the organic linkers in the MOF. The complete decomposition temperatures of Mn-MOF-Sphe, Mn-MOF-Leaf, Mn-MOF-Rod, and Mn-MOF-Cube were 506, 502, 545, and 593 °C, respectively, suggesting that these Mn-MOF precursors possess great thermal stability. According to the above characterizations, these Mn-MOFs with different morphologies were successfully prepared.

Figure 3.

The TG curves of the Mn-MOFs with different morphologies.

2.2. Characterizations of the Mn-MOF-Derived MnOx Catalysts

The MnOx catalysts were prepared by using Mn-MOFs with various morphologies as the precursors. As presented in Figure 3, the complete collapse temperature of these Mn-MOF precursors was above 500 °C. Among them, the decomposition temperature of Mn-MOF-Cube was as high as 593 °C. To ensure the complete conversion of these Mn-MOFs precursors to MnOx, the Mn-MOFs precursors were calcined at 700 °C under a 30.0 vol.% O2/Ar atmosphere for 2 h directly.

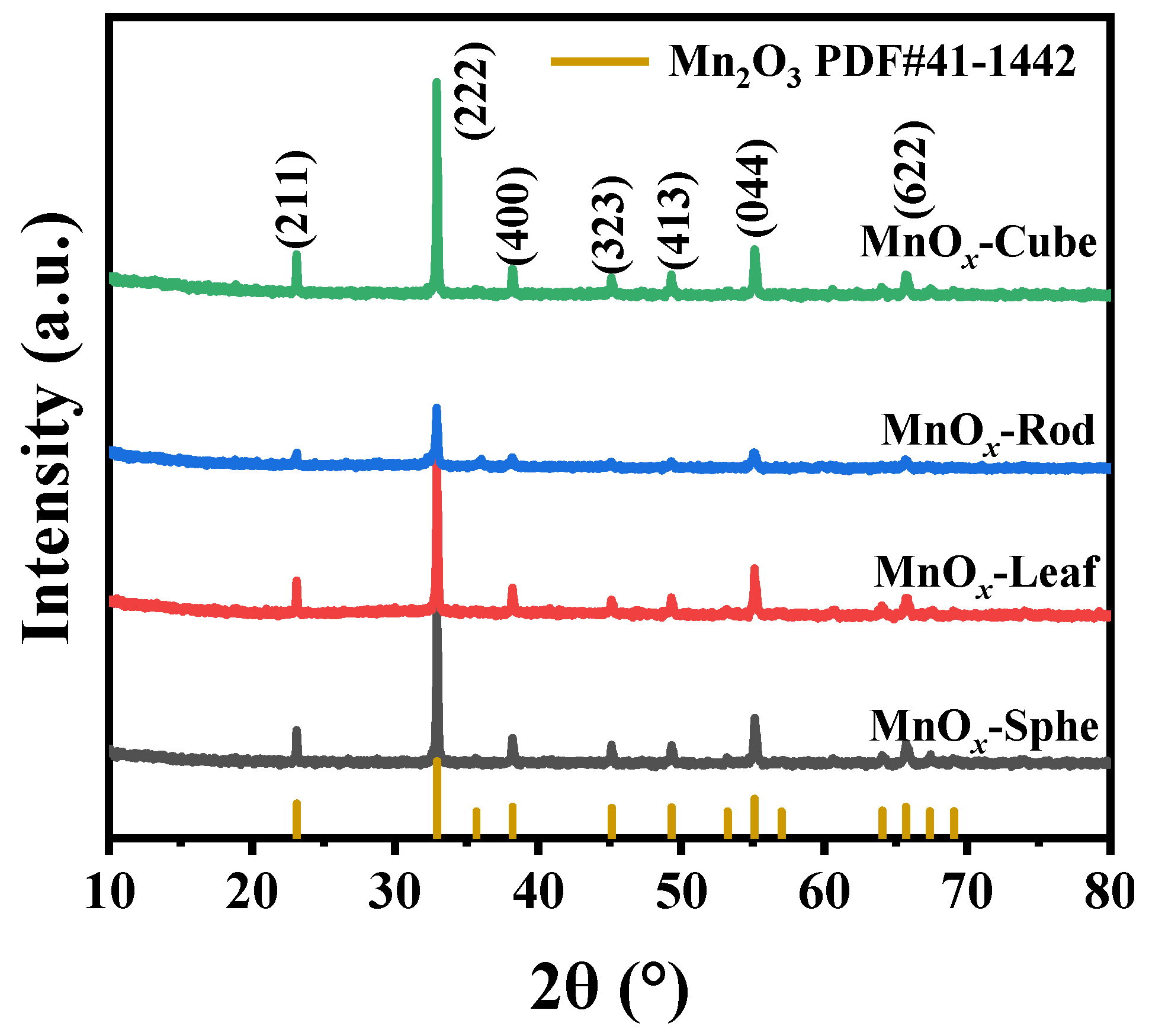

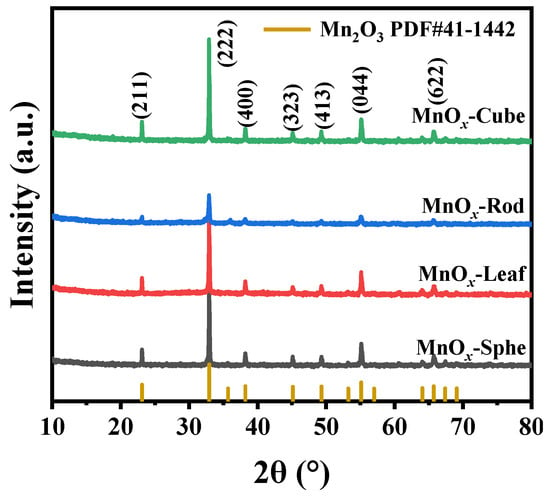

The crystal structure of these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts was studied via XRD (Figure 4). As presented in Figure 4, all the Mn-MOF-derived catalysts presented the similar XRD peaks at 23.12°, 32.92°, 38.20°, 45.14°, 49.32°, 55.14°, and 65.72°, corresponding to the (211), (222), (400), (323), (413), (044), and (622) crystal facets of Mn2O3 (PDF#41–1442), respectively. Meanwhile, no other diffraction peaks corresponded to the Mn-MOFs structure, which suggested that these Mn-MOF precursors were converted to MnOx completely after 700 °C calcination. Notably, compared with other MnOx catalysts, the XRD peak intensity of Mn-MOF-Rod-derived MnOx-Rod catalyst was weak, which might be related to the better thermal stability of Mn-MOF-Rod (593 °C) in comparison to other Mn-MOFs (<550 °C), resulting in the weak crystallinity of MnOx-Rod.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the MOF-derived MnOx catalysts.

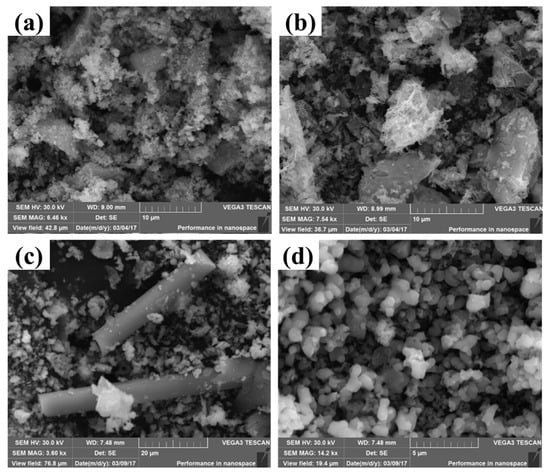

To investigate the morphology of these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts, SEM was employed. Figure 5a–d show the SEM images of MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Leaf, MnOx-Rod, and MnOx-Cube, respectively. As shown in Figure 5a, compared with the Mn-MOF-Sphe, which presented the size of a 10 μm sphere (Figure 2a), the MnOx-Sphe displayed an irregular shape with a smaller size, which might be ascribed to the structure collapse during the higher temperature calcination to form the small Mn2O3 particles. A similar phenomenon could also be observed in MnOx-Rod (Figure 5c) and MnOx-Cube (Figure 5d). Different from MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Rod, and MnOx-Cube, Mn-MOF-Leaf-derived MnOx-Leaf (Figure 5b) exhibited the leaf-like morphology with a rough surface, which suggested the shape of the leaf in Mn-MOF-Leaf was kept through high-temperature calcination. Meanwhile, the rough surface could provide more active sites for small molecule adsorption and activation, improving the catalytic efficiency for pollution degradation [46].

Figure 5.

SEM images of the MOF-derived MnOx catalysts: (a) MnOx-Sphe, (b) MnOx-Leaf, (c) MnOx-Rod, and (d) MnOx-Cube.

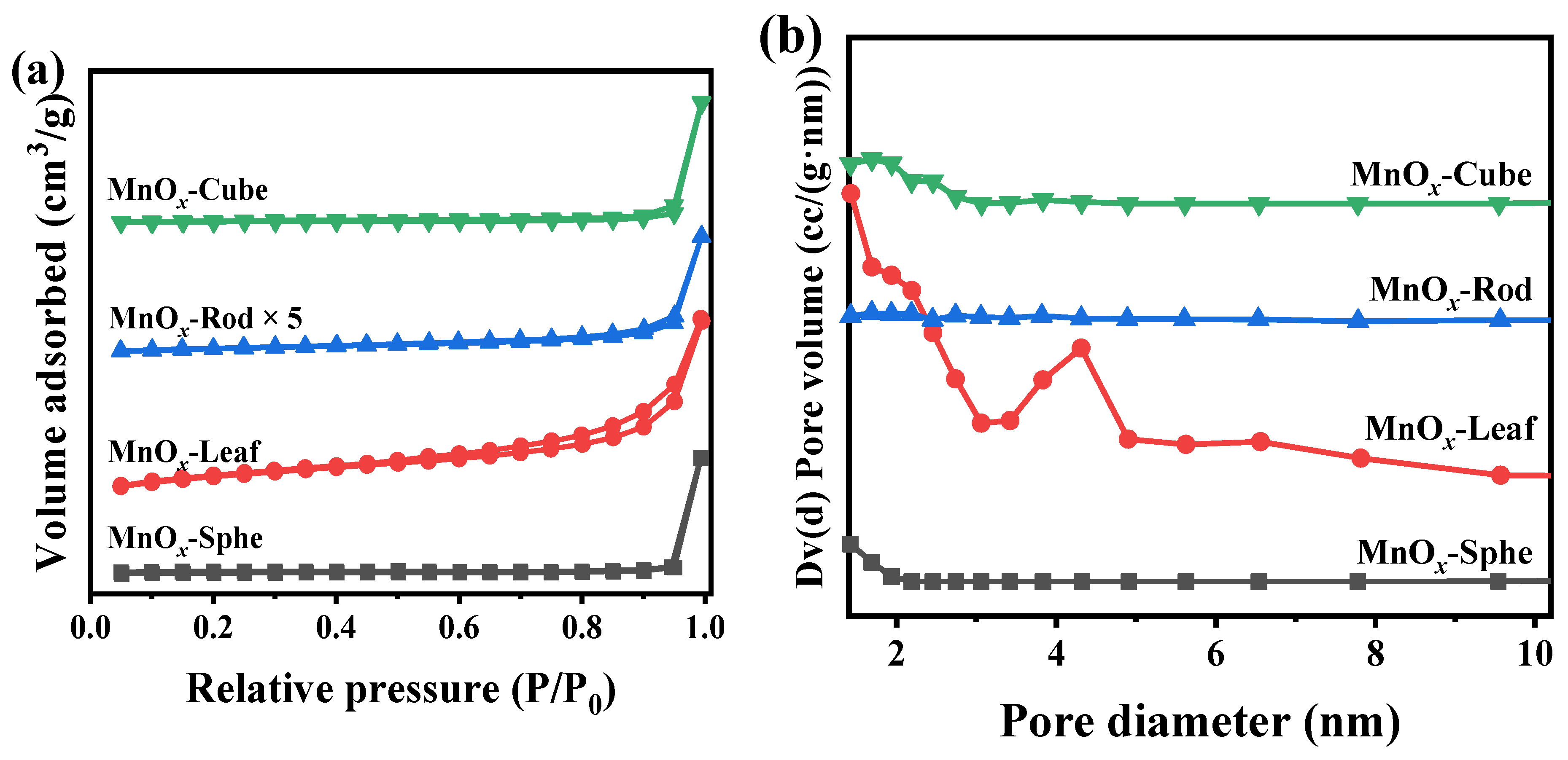

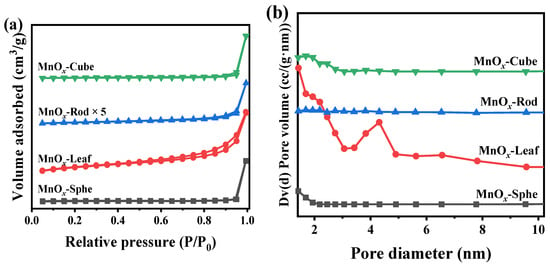

Generally, the surface area and pore structure were the important parameters of a catalyst. Therefore, the N2 adsorption–desorption was applied to study the surface area and pore structure of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts. Figure 6a,b exhibit the N2 adsorption–desorption curves and corresponding pore size distribution, calculated via the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method according to the desorption branch of the N2 adsorption–desorption curves, respectively. The corresponding surface area, total pore volume, and pore diameter are listed in Table 1. As depicted in Figure 6a, all the as-prepared catalysts presented a V typed isotherm [47,48]. Compared with other Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts, an H3-typed hysteresis loop could be found in MnOx-Leaf, indicating the presence of a mesoporous structure. Meanwhile, the presence of many mesopores in MnOx-Leaf can also be observed in the pore size distribution in Figure 6b. Furthermore, compared with MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Rod, and MnOx-Cube, MnOx-Leaf exhibited a smaller pore volume intensity in the pore size distribution (Figure 6b), which might be attributed to the fast collapse of the MOF during the high-temperature calcination, causing the blockage of the pore structure. This was kept in line with the SEM result in Figure 5. As illustrated in Table 1, the surface area and total pore volume of MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Leaf, MnOx-Rod, and MnOx-Cube were 4.8 m2/g and 0.032 cm3/g, 32.1 m2/g and 0.091 cm3/g, 1.7 m2/g and 0.017 cm3/g, and 13.5 m2/g and 0.062 cm3/g, respectively. Obviously, MnOx-Leaf, with the large pore diameter, displayed a large surface area and pore volume.

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption–desorption curves (a) and pore diameter distributions (b) of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts.

Table 1.

Physical–chemical parameters and catalytic performance of the MOF-derived MnOx catalysts.

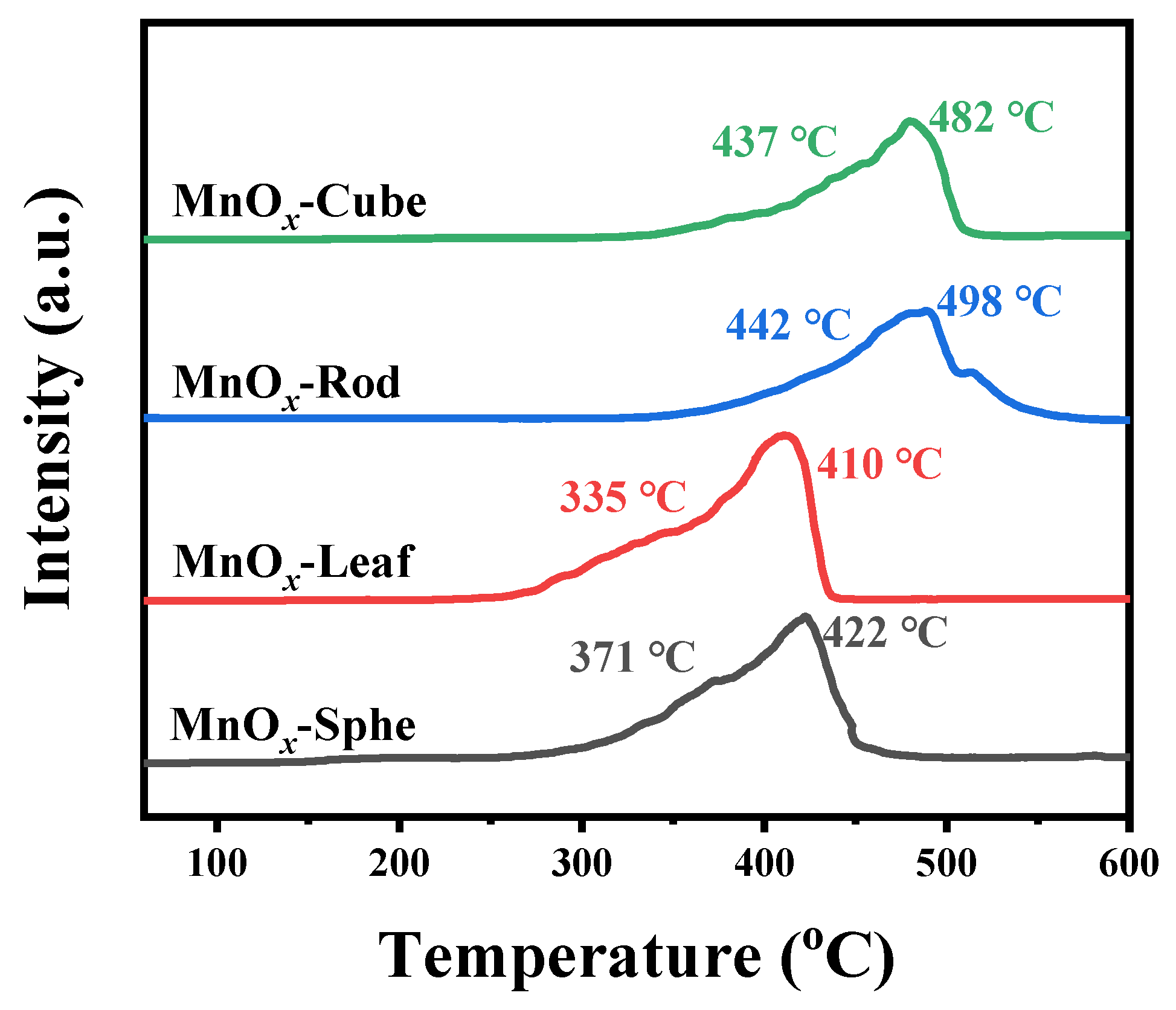

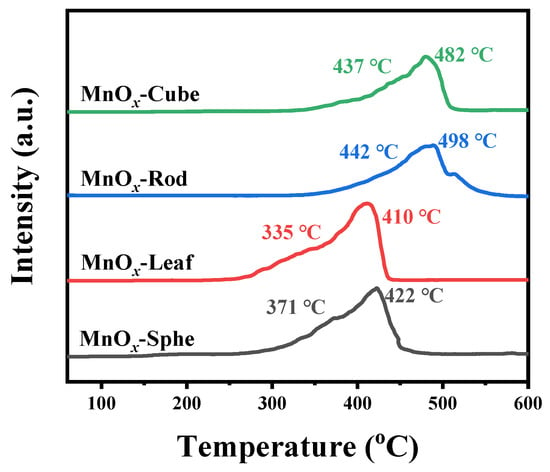

To understand the redox properties of these Mn-MOF-derived catalysts, the H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) was performed from 50 to 600 °C [49]. Figure 7 exhibits the H2-TPR profiles of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts. As presented in Figure 7, two reduction peaks were observed in all samples. For MnOx-Sphe and MnOx-Leaf, the first reduction peak below 400 °C was attributed to the reduction of Mn2O3 to Mn3O4 [50,51], while the other reduction peak above 400 °C was attributed to the reduction of Mn3O4 to MnO [52,53]. For MnOx-Rod and MnOx-Cube, the reduction peaks for the reduction of Mn2O3 to Mn3O4 and Mn3O4 to MnO were shifted to higher temperatures. Apparently, MnOx-Leaf possessed the lowest reduction temperatures (335 and 410 °C), followed by MnOx-Sphe (371 and 422 °C), MnOx-Cube (437 and 482 °C), and MnOx-Rod (442 and 498 °C), which suggested MnOx-Leaf presented the best reducibility at low temperature. Additionally, to further evaluate the reducibility of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts, the H2 consumption (Table 1) was calculated based on the reduction peaks area in the H2-TPR profiles. The H2 consumption over MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Leaf, MnOx-Rod, and MnOx-Cube was 339.9, 398.3, 251.5, and 280.7 μmol/g, respectively, which also confirmed that MnOx-Leaf possessed the best low-temperature reduction ability. As maintained in the XRD patterns, all the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx presented the Mn2O3 crystal structure. However, their H2-TPR profiles exhibited distinct reduction temperatures and H2 consumption. This discrepancy arises from differences in microstructural properties, such as surface area, porosity, and morphology, which influence the accessibility and reactivity of oxygen species. A similar phenomenon was also observed by Liu et al. [54]. Their study also found that the morphologies of α-Mn2O3 presented great influence on their reducibility, confirming the morphology-dependence of redox behavior. Herein, the high surface area of MnOx-Leaf (32.1 m2/g), its mesoporous structure, and preserved leaf-like morphology contribute to its enhanced low-temperature reducibility, as evidenced by its lowest reduction peaks and highest H2 consumption.

Figure 7.

H2-TPR profiles of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts.

2.3. Catalytic Performance of the Mn-MOF-Derived MnOx Catalysts for CO Oxidation

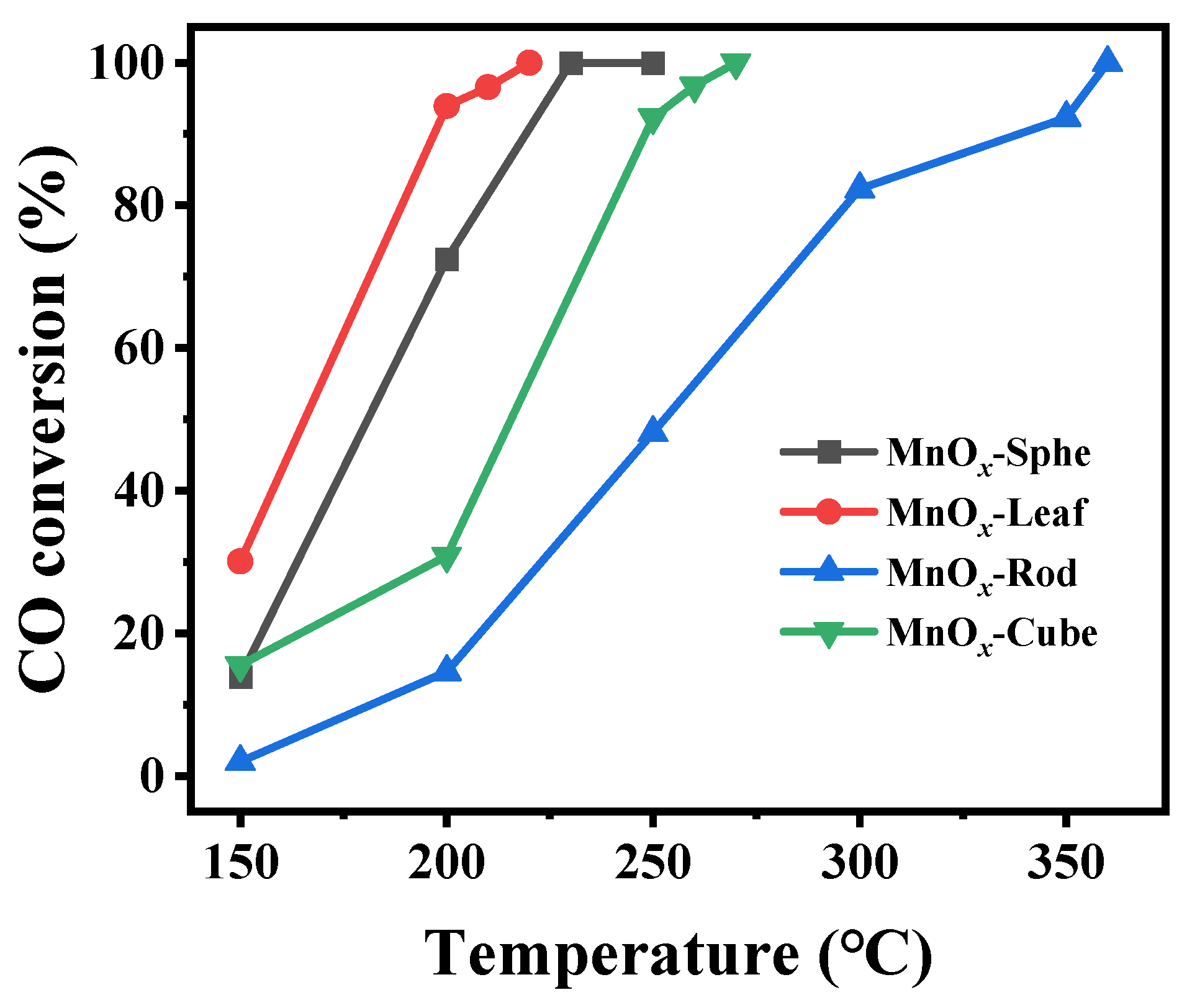

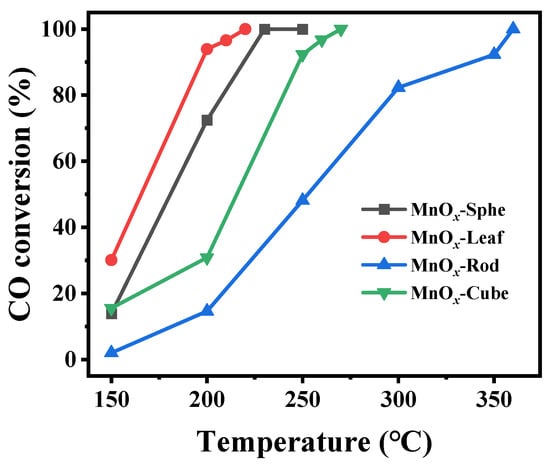

The catalytic activity of these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts was estimated via CO catalytic oxidation. Figure 8 presents CO conversion over these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts. Meanwhile, the temperatures at which CO conversion reached 50% and 98% (T50 and T98) were calculated (Table 1). As illustrated in Figure 8, the Mn-MOF-Leaf-derived MnOx-Leaf catalysts presented the best catalysts, followed by MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Cube, and MnOx-Rod. The T50 and T90 values of MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Leaf, MnOx-Rod, and MnOx-Cube were 180 and 228 °C, 165 and 214 °C, 253 and 357 °C, and 216 and 262 °C, respectively, which also demonstrated that MnOx-Leaf presented the best CO oxidation activity. Additionally, compared with the reported MnOx catalysts [55,56], other metal oxide catalysts [57,58,59,60], and even supported noble metal catalysts [61,62,63] (Table 2), the Mn-MOF-Leaf-derived MnOx-Leaf also presented a relatively low-temperature CO oxidation performance (T98 = 214 °C), indicating its good CO oxidation ability.

Figure 8.

Temperature-dependent CO conversions over the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts for CO oxidation (reaction condition: 1.0 vol.% CO, 20.0 vol.% O2, balanced with He; 100 mg of catalysts particle with the size of 0.43–0.85 mm (20–40 mesh), total flow: 18,000 mL/(g·h), heating rate: 10 °C/min; at each temperature, the reaction was held for 40 min.).

Table 2.

CO catalytic oxidation performance of metal oxide and supported noble metal catalysts reported in the literature.

As is well known, the catalytic performance of a catalyst is greatly influenced by its physicochemical properties [64,65]. Generally, the large surface area and pore size could increase the exposure of more surface active sites to boost the adsorption of the pollutant molecules and promote the desorption of degradation products [66]. Meanwhile, the better low-temperature redox properties could accelerate the oxidation–reduction cycle to promote the rapid transformation of pollutants [67]. For example, Luo et al. [68] confirmed that the CuO-CeO2 catalysts with a large surface area exposed more active sites than those with low surface area catalysts, which induced the high catalytic performance of the catalyst with a large surface area for CO oxidation. Meanwhile, our previous work [69] also observed that the Ce-BTC-derived CeO2 catalysts with a large surface area presented better CO oxidation activity. Additionally, Wang et al. [70] confirmed that the catalytic performance of CuOx/CeO2 catalysts for CO oxidation could be greatly enhanced via the tuning of their low-temperature redox properties. Herein, according to the above catalysts characterization and catalytic performance test results, Mn-MOF-Leaf-derived MnOx-Leaf with the large surface area (32.1 m2/g), better low-temperature reduction ability, and high H2 consumption amount (398.3 μmol/g) displayed the optimal CO oxidation activity (T98 = 214 °C). Therefore, the superior catalytic performance of MnOx-Leaf for CO oxidation can be attributed to the synergistic effects of its physicochemical properties. Specifically, the large surface area and mesoporous structure facilitate the diffusion and adsorption of reactant molecules, maximizing the accessibility to active sites. The better low-temperature reducibility, as evidenced by the lowest reduction temperatures in H2-TPR, indicates the presence of highly labile lattice oxygen species, which are crucial for the oxidation process via the Mars–van Krevelen mechanism. Concurrently, the highest H2 consumption suggests a greater abundance of reducible oxygen species and a higher capacity for oxygen vacancy formation. These oxygen vacancies are pivotal for the adsorption and activation of gaseous O2, promoting the replenishment of the consumed lattice oxygen and thus sustaining the catalytic cycle at lower temperatures. In essence, the large surface area ensures the efficient utilization of active sites, while the superior redox properties, easy lattice oxygen removal, and facile oxygen vacancy formation dictate the intrinsic activity of these sites, collectively contributing to the outstanding CO oxidation activity of MnOx-Leaf. According to the above, the better catalytic performance of MnOx-Leaf for CO oxidation could be attributed to its large surface area, better low-temperature reduction ability, and high H2 consumption.

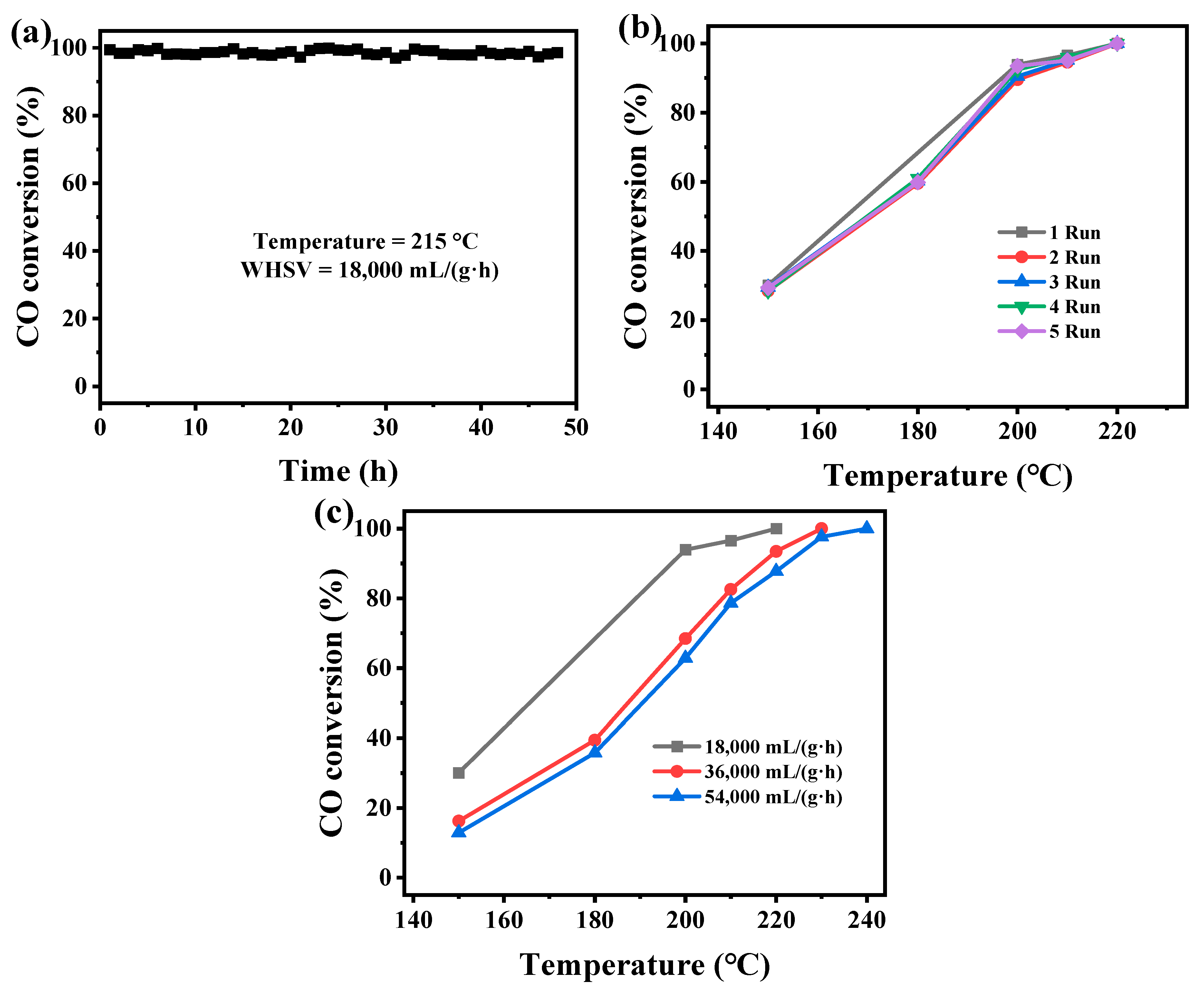

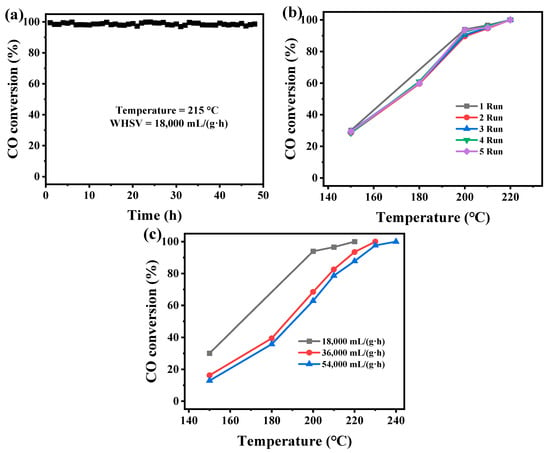

Typically, the factors for evaluating the catalytic activity of a catalyst also include its stability, reusability, and resistance to weight hourly space velocity (WHSV). Therefore, the MnOx-Leaf with the optimal catalytic performance for CO oxidation was selected to estimate the stability, reusability, and influence of WHSV. Figure 9a presents the thermal stability test of MnOx-Leaf for CO oxidation at 215 °C. As depicted in Figure 9a, MnOx-Leaf displayed the CO conversion of nearly 98% at 215 °C for 48 h, which confirmed its great stability for the catalytic degradation of CO. As shown in Figure 9b, after being reused five times, the catalytic performance of MnOx-Leaf for CO oxidation decreased slightly, suggesting the great reusability of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts. Figure 9c presents the influence of WHSV on MnOx-Leaf for CO oxidation. As displayed in Figure 9c, as the WHSV increased from 18,000 to 36,000 mL/(g·h), and the CO oxidation activity over MnOx-Leaf decreased significantly. With a further increase in WHSV to 54,000 mL/(g·h), the CO degradation performance decreased slightly. The decrease in CO oxidation activity might be ascribed to the fact that the contact time between CO molecules and the active sites of the catalyst was reduced. Thus, according to the above results, it could be concluded that the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx-Leaf presented great stability and reusability for CO catalytic oxidation.

Figure 9.

The stability (a) and reusability (b) of MnOx-Leaf for CO oxidation, and influence of space velocity (c) on the MnOx-Leaf for CO oxidation.

2.4. CO Oxidation Mechanism over MnOx-Leaf

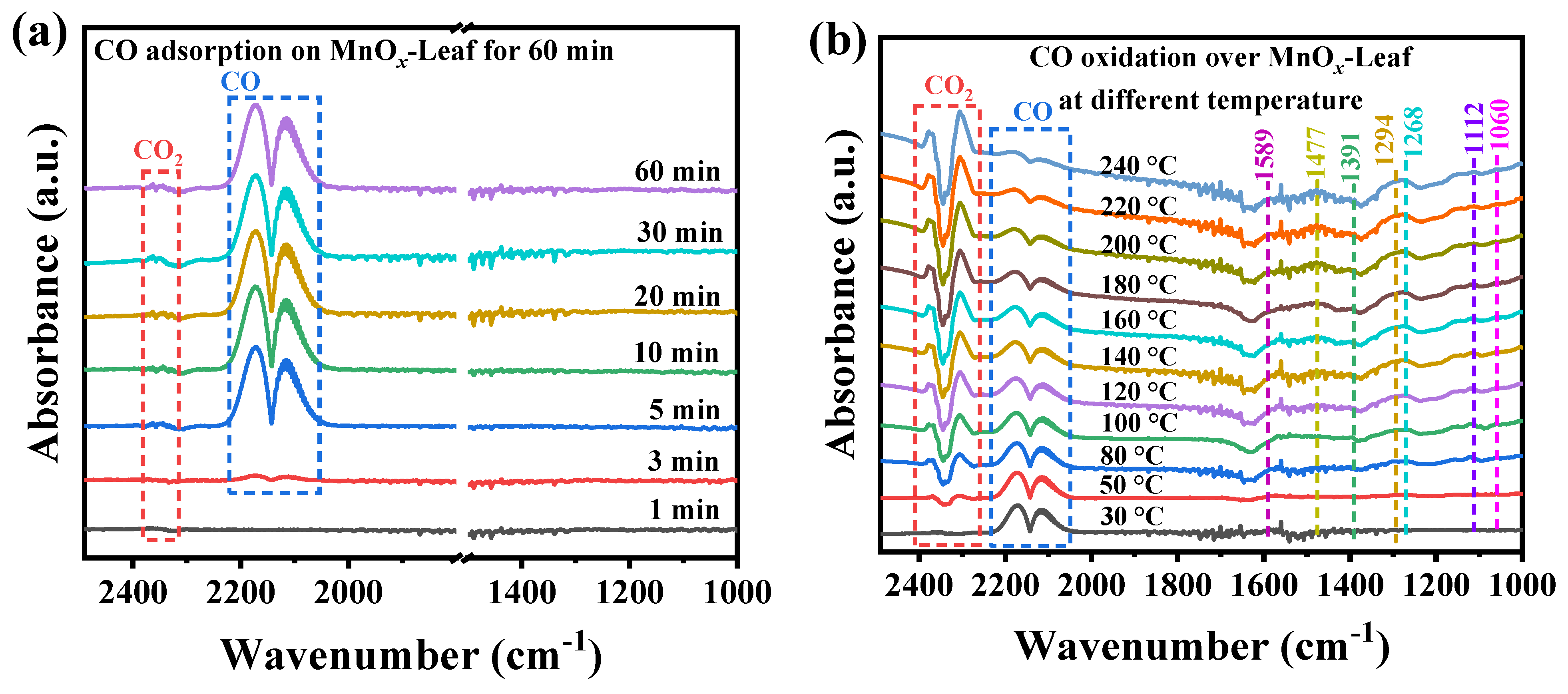

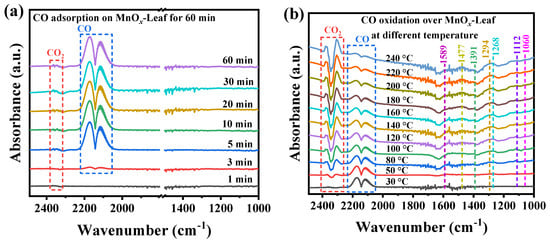

Generally, the in situ DRIFTS was sensitive to the changes in intermediates on the catalyst’s surface for gaseous pollution degradation [71]. Therefore, the in situ DRIFTS was hired to investigate the CO oxidation mechanism over MnOx-Leaf. Figure 10a,b display the in situ DRIFTS spectra for CO adsorption and oxidation over MnOx-Leaf, respectively, and the assignment of the absorption bands is displayed in Table 3. Figure 10a presents the in situ CO adsorption spectra for 60 min. As illustrated in Figure 10a, the absorption bands at 2300–2400 cm−1 were attributed to the gaseous CO2 [72,73]. The other two absorption bands at 2114 and 2175 cm−1 were assigned to the adsorption of gaseous CO [74,75]. As the adsorption time improved from 1 to 60 min, the bands corresponding to gaseous CO were gradually enhanced, accompanied by the appearance of the adsorbed CO2, which suggested that the CO molecules were first adsorbed on the catalyst’s surface and then oxidized by the adsorbed oxygen species to generate CO2. Figure 10b presents the in situ DRIFTS spectra for CO oxidation at different temperatures after preabsorbing 1.0 vol.% CO for 60 min. As shown in Figure 10b, with the reaction temperature elevated, the absorption peaks ascribed to the adsorbed CO molecules were weakened gradually, and the intensity of CO2 was improved. Meanwhile, several new absorption bands appeared. The absorption band at 1060 cm−1 was assigned to the vibration of COO−, indicating the formation of carboxyl salt species during CO oxidation [76,77]. The band at 1112 cm−1 was attributed to the adsorption of O2 on M+-O2− [78]. The band at 1268 cm−1 was due to the vibration of bicarbonate, suggesting the formation of HCO3− species during CO oxidation [79,80]. Two bands at 1294 and 1589 cm−1 were attributed to the νs (OCO) and νas (OCO) stretching of bidentate carbonate species, respectively, indicating the formation of b-CO32− [79,80,81,82]. The bands at 1391 and 1477 cm−1 were attributed to the νs (OCO) stretching of monodentate carbonate species and polydentate carbonate, respectively, suggesting the generation of m-CO32− on the catalyst’s surface [81,82,83,84]. As the temperature increased from 30 to 240 °C, the peak intensity of these intermediates was gradually enhanced, indicating the degradation of CO over MnOx-Leaf. Therefore, according to the above analysis, it could be concluded that CO and O2 were adsorbed on the catalyst surface and oxidized to form surface carbon-related species (bicarbonate and carbonate), and finally converted to CO2.

Figure 10.

In situ DRIFTS spectra for CO adsorption (a) and oxidation (b) over MnOx-Leaf catalysts.

Table 3.

The assignment of the species generated during CO adsorption and oxidation over MnOx-Leaf catalysts.

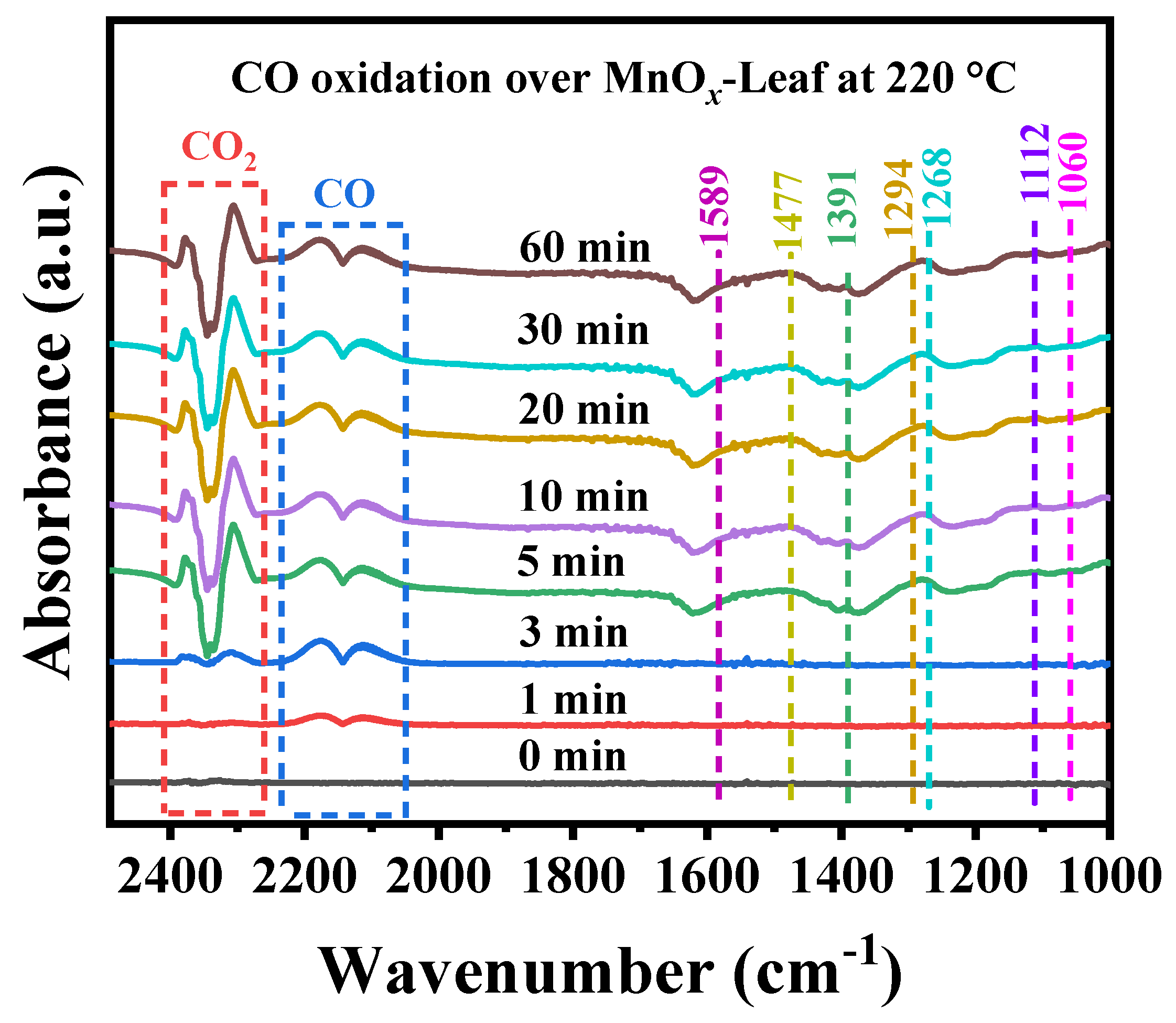

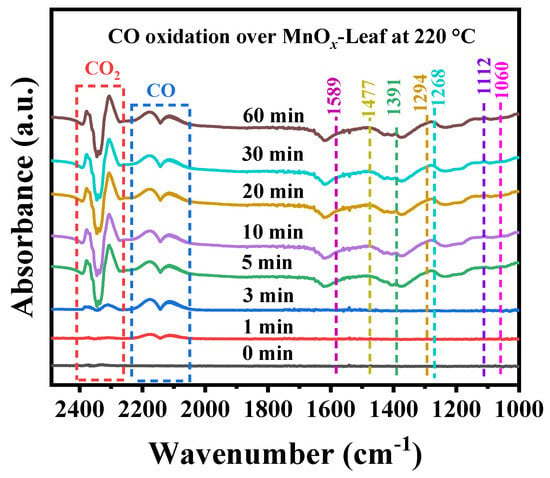

To further investigate the possible intermediates generated over MnOx-Leaf during CO oxidation, the in situ DRIFTS spectra for CO oxidation at a certain temperature of 220 °C was carried out in a continuous flow reaction condition of 1.0 vol.% CO + 20.0 vol.% O2 balanced with He atmosphere under the total flow of 30 mL/min. The result is summarized in Figure 11, and the corresponding assignment of the intermediates is summarized in Table 3. As presented in Figure 11, with the reaction time increased, the absorption peaks intensity of gaseous CO at 2114 and 2175 cm−1 first increased and then stabilized. Meanwhile, the absorption peaks of CO2 at 2309 and 2372 cm−1 were enhanced gradually, which suggested CO was oxidized to form CO2. Additionally, as the reaction time increased to 5 min, some new absorption bands at 1589 (b-CO32−), 1477 (m-CO32−), 1391 (m-CO32−), 1294 (b-CO32−), 1268 (HCO3−), 1112 (adsorption of O2), and 1060 (carboxyl salt species) cm−1 appeared with the strengthening of CO2 absorption peaks. The appearance of these new bands suggested that some of the intermediates were formed during CO oxidation. Combined with temperature-dependent in situ DRIFTS CO oxidation spectra, the possible CO oxidation pathway could be further obtained so that CO and O2 were adsorbed on the catalyst surface and oxidized to form surface carbon-related species (bicarbonate and carbonate), and finally converted to CO2.

Figure 11.

In situ DRIFTS spectra for CO oxidation over MnOx-Leaf catalysts at 220 °C.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

All the chemicals, including manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl2·4H2O), manganese(II) nitrate tetrahydrate (Mn(NO3)2·4H2O), 1,3,5-benzene tricarboxylic acid (H3-BTC, C9H6O6), terephthalic acid (H2-BDC, C8H6O4), hydrochloric acid (HCl), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, C3H7NO), N,N-Dimethylacetamide (DMA, C4H9NO) methanol (CH3OH), meso-butane-1,2,3,4-tetracarboxylic acid (H4BuTC, C8H12O8), 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalic acid (C8H6O6), and ethanol (C2H6O), were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and used without any purification.

3.2. Catalysts Preparation

3.2.1. Synthesis of the Mn-MOFs Precursors with Different Morphologies

All the Mn-MOFs with different morphologies were prepared via the solvothermal method according to the literature [40,41,42,85]. The detailed synthesis processes are listed as follows.

(1) Synthesis of the spherical Mn-MOF

Firstly, 60 mL of mixed solution containing DMF, ethanol, and H2O with a volume ratio of 15:1:1 was prepared. Then, 0.22 g of MnCl2·4H2O (1.11 mmol) and 0.067 g of 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalic acid (0.366 mmol) were added to the above solution and stirred until completely dissolved. After that, the clear solution was transferred into an autoclave and crystallized in an oven at 135 °C for 24 h. Finally, after natural cooling, the spherical Mn-MOF, named Mn-MOF-Sphe, could be acquired through centrifugation, was washed with DMF and ethanol several times, and dried at 80 °C for 12 h.

(2) Synthesis of the leaf-like Mn-MOF

A total of 0.38 g of H4BuTC (1.6 mmol) and 0.8 g of Mn(NO3)2·4H2O (3.2 mmol) were dissolved in 25 mL DMA, and stirred until a clear solution formed. Then, the above two solutions were mixed and stirred for 30 min. After that, the mixed solution was transferred to an autoclave and crystallized in an oven at 100 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the faint yellow solid product could be acquired via centrifugation and was washed with DMA and ethanol several times. Finally, the leaf-like Mn-MOF named Mn-MOF-Leaf powder was obtained after drying in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h.

(3) Synthesis of the rod-like Mn-MOF

A total of 0.49 g of Mn(CH3COO)·4H2O and 0.3 g of PVP were poured into a 10 mL ethanol and water mixed solution with a volume ratio of 1:1 and stirred until dissolved completely to form solution A. Then, 0.09 g of H3-BTC was dissolved in another 10 mL ethanol and water mixture (volume ratio: 1:1) to generate solution B. After that, solution B was slowly dropped into solution A under vigorous stirring at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the mixed solution reacted without any heating for 24 h. Finally, the rod-like Mn-MOF powder, named Mn-MOF-Rod, could be obtained via centrifugation, was washed with DMF and ethanol several times, and dried at 80 °C for 12 h.

(4) Synthesis of the cube-like Mn-MOF

A total of 0.95 g of MnCl2·4H2O (4.8 mmol), 0.53 g of H2-BDC (3.2 mmol), and 1.2 mL of HCl solution (2 mol/L) were added to 120 mL of DMF solution and ultrasonicated until complete dissolution. After that, the clear solution was poured into an autoclave and crystallized in an oven at 120 °C for 12 h. After cooling down, the cube-like Mn-MOF powder, named Mn-MOF-Cube, could be obtained via centrifugation, was washed with DMF and ethanol several times, and dried at 80 °C for 12 h.

3.2.2. Synthesis of the Mn-MOF-Derived MnOx Catalysts

The Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts were prepared through the high-temperature pyrolysis of Mn-MOFs. Taking Mn-MOF-Sphe-derived MnOx as an example, a certain amount of Mn-MOF-Sphe was placed in a quartz reaction tube, and a 30% O2/Ar mixture gas was introduced to the reaction tube. Then, the quartz reaction tube was heated from 30 °C to 700 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and kept at 700 °C for 2 h. Finally, after cooling to 30 °C, the black MnOx powder could be acquired. The MnOx was prepared by using Mn-MOF-Sphe, Mn-MOF-Leaf, Mn-MOF-Rod, and Mn-MOF-Cube as the precursors, which were named MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Leaf, MnOx-Rod, and MnOx-Cube, respectively.

3.3. Catalysts Characterization

The as-prepared Mn-MOFs precursors and their derived MnOx catalysts were characterized by many techniques, such as XRD, SEM, TG, etc. The detailed processes of these characterizations are summarized as follows.

(1) The crystal texture of the Mn-MOFs precursors and their derived MnOx catalysts was characterized by XRD, which was performed on an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advance, Billerica, MA, USA), equipped with Cu-Kα radiation and a monochromatic detector. Working conditions: 40 mA of emission current, 40 kV of accelerating voltage, 5°/min of scanning rate, and 10–80° of 2θ range.

(2) The SEM images of the Mn-MOFs precursors and their derived MnOx catalysts were acquired from a scanning electron microscope (VEGA-3-SBH, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic). Before the test, the sample needed to undergo gold plating treatment.

(3) The TG curves of the Mn-MOFs precursors were obtained from a thermal gravimetric analyzer (STA8000, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) under air conditions from 30 °C to 700 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

(4) The N2 adsorption–desorption curves of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts were obtained from a Quantachrome automatic physical adsorption instrument (Autosorb iQ2, Quantachrome, Boca Raton, FL, USA) at −196 °C. Before the test, the sample was pretreated under vacuum at 300 °C for 8 h to remove the impurities in the pore channel. According to the N2 adsorption–desorption curves, the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model were used to calculate the surface area and pore size distribution, respectively.

(5) The H2-TPR profiles of the Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts were acquired from a Quantachrome ChemBET TPR/TPD automatic chemical adsorption instrument (Boca Raton, FL, USA) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Generally, a certain amount of sample was treated under N2 atmosphere at 120 °C for 0.5 h. After cooling naturally, a 10.0 vol.% H2/Ar mixed gas was introduced into the reaction system and kept for 0.5 h. Finally, the temperature-programmed process was performed and heated to 600 °C under 10.0 vol.% H2/Ar atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

(6) The in situ DRIFTS spectra were obtained from a Nicolet/iS50 infrared spectrometer (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an in situ reaction cell. Generally, 50 mg of the catalyst powder was placed in the reaction cell. Before the test, the sample was pretreated under an Ar atmosphere at 250 °C for 1 h to remove the impurities in the catalyst’s pore channel. After cooling to room temperature, the background was taken, the reaction gas, 1.0 vol.% CO + 20.0 vol.% O2, balanced with He, was introduced into the in situ reaction cell, and the adsorption spectra were collected. After that, the reaction cell was heated to the target temperatures, and the oxidation spectra were collected. During the oxidation process, the reaction gas was continuously introduced into the reaction cell. The scanning time was 32, and the resolution ratio was set at 4.

For time-dependent in situ DRIFTS spectra, 50 mg of the catalyst powder was placed in the reaction cell and pretreated under an Ar atmosphere at 250 °C for 1 h. After that, the temperature was cooled to 220 °C, and the background was taken. Then, the gas was changed to the reaction gas, 1.0 vol.% CO + 20.0 vol.% O2, balanced with He, at a flow rate of 30 mL/min, and the spectra were collected for 1 h. The scanning time was 32, and the resolution ratio was set at 4.

3.4. Catalytic Performance Test

A fixed-bed microreactor was applied to evaluate the catalytic performance of these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalytic performances by using CO as the probe molecule. Typically, 100 mg of the catalyst with a particle size in the range of 0.43–0.85 mm was poured into a quartz tube reactor. Then, the mixed gas containing 1.0 vol.% CO, 20.0 vol.% O2, balanced with He was introduced to the reactor at a flow rate of 30 mL/min; the weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) was 18,000 mL/min. The flow rate was controlled by a mass flowmeter. An open-type tubular furnace equipped with a temperature controller and a thermocouple was used to control the reaction temperature. At each temperature, the CO concentration was measured three times, and the average value was used to calculate the CO conversion. A GC2060 (Ruimin, Shanghai, China) online gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a TCD and a 5A molecular sieve packed column (3 m × 3 mm) was applied to determine the initial (Cin) and post-reaction (Cout) CO concentrations. The CO conversion (XCO) was calculated by the following formula:

XCO = (Cin − Cout)/Cin × 100%

4. Conclusions

In summary, four Mn-MOFs with spherical, leaf-like, rod-like, and cube-like morphologies were successfully prepared, and the MnOx catalysts with the Mn2O3 crystal structure were successfully prepared at 700 °C by using these Mn-MOFs as the precursors. The catalytic performance of these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts was evaluated for catalytic CO oxidation. The physical–chemical properties of these MnOx catalysts were characterized by many techniques. It was found that the high-temperature calcination could induce a great change in these Mn-MOFs, which resulted in the different physicochemical properties of the MnOx catalysts. Among these Mn-MOF-derived MnOx catalysts, the leaf-like Mn-MOF-derived MnOx-Leaf catalyst presented the optimal CO oxidation with a T98 value of 214 °C, followed by MnOx-Sphe (T98 = 228 °C), MnOx-Cube (T98 = 262 °C), and MnOx-Rod (T98 = 357 °C). Meanwhile, MnOx-Leaf presented great stability and reusability for CO oxidation. Characterization results showed that, compared with MnOx-Sphe, MnOx-Cube, and MnOx-Rod, the leaf-like Mn-MOF-derived MnOx-Leaf possessed a large surface area, better low-temperature reducibility, and high H2 consumption, which resulted in the fast CO oxidation at low temperature. Finally, the possible CO oxidation pathway over MnOx-Leaf was revealed by in situ DRIFTS. The results showed that CO and O2 were adsorbed on the catalyst surface and oxidized to form surface carbon-related species (bicarbonate and carbonate) and finally to CO2. This work could provide guidance for the preparation of MnOx catalysts for CO oxidation.

Author Contributions

F.B.: writing—original draft, funding acquisition, data curation, and formal analysis. Y.W. (Yanxuan Wang): data curation, formal analysis, and investigation. J.H.: data curation, methodology, and software. H.Q.: investigation and software. H.L.: conceptualization and resources. B.L.: supervision and visualization. Y.W. (Yuxin Wang): conceptualization, validation, and writing—review and editing. X.Z.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22506124 and 12175145) and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (24YF2729800).

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the sponsor of Energy Science and Technology discipline under the Shanghai Class IV Peak Disciplinary Development Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pan, H.; Chen, X.; López-Cartes, C.; Martínez-López, J.; Bu, E.; Delgado, J.J. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of Cu-MnOx catalysts for CO oxidation: Effect of Cu:Mn molar ratio on their structure and catalytic activity. Catal. Today 2023, 418, 114085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, H.; Meijer, G.; Scheffler, M.; Schlögl, R.; Wolf, M. CO Oxidation as a Prototypical Reaction for Heterogeneous Processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 10064–10094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberg, K.; Cohen, N.; Wilson, K.W. Carbon Monoxide: Its Role in Photochemical Smog Formation. Science 1971, 171, 1013–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Peng, B.; Zhu, X.; Guo, Y. Multi-Gas Detection System Based on Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR) Spectral Technology. Sensors 2022, 22, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Tao, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, N.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X. Advances in photocatalytic removal of NOx and VOCs from flue gas. Energy Environ. Prot. 2024, 38, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.; Fukushima, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Higashimoto, S. Visible-light responsive TiO2 for the complete photocatalytic decomposition of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and its efficient acceleration by thermal energy. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 346, 123745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Tian, F.; Bi, F.; Rao, R.; Wang, Y.; Tao, H.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X. Nitrogen-induced TiO2 electric field polarization for efficient photodegradation of high-concentration ethyl acetate: Mechanisms and reaction pathways. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 41, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Cui, H.; Tang, K.; Crawshaw, D.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L. Highly Selective CO2 Conversion to CH4 by N-doped HTiNbO5/NH2-UiO-66 Photocatalyst Without Sacrificial Electron Donor. JACS Au 2025, 5, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, D.; Xie, T.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Z.; Yang, R. Photothermal Synergism on Pd/TiO2 Catalysts with Varied TiO2 Crystalline Phases for NOx Removal via H2-SCR: A Transient DRIFTS Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 14823–14836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, L.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Electron Beam Irradiation-Induced Defects Enhance Pt-TiO2 Photothermal Catalytic Degradation in PAEs: A Performance and Mechanism Study. Molecules 2025, 30, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, P.; Zhang, M.-H.; Cheng, Y.; Riang, D.T.; Yu, L.E. Photocatalytic degradation of SO2 using TiO2-containing silicate as a building coating material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 43, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bi, F.; Wei, J.; Han, X.; Gao, B.; Qiao, R.; Xu, J.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X. Boosting the Photothermal Oxidation of Multicomponent VOCs in Humid Conditions: Synergistic Mechanism of Mn and K in Different Oxygen Activation Pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11341–11352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S.; Alphin; Manigandan, S.; Vignesh, S.; Vigneshwaran, S.; Subash, T. A review of comparison between the traditional catalyst and zeolite catalyst for ammonia-selective catalytic reduction of NOx. Fuel 2023, 344, 128125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, S.; You, M.; Yu, D.; Zhang, C.; Gao, S.; Yu, X.; Zhao, Z. Research Progress on Metal Oxides for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with Ammonia. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Feng, X.; Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; et al. Unveiling the Influence Mechanism of Impurity Gases on Cl-Containing Byproducts Formation During VOC Catalytic Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15526–15537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shu, M.; Niu, Y.; Yi, L.; Yi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, S.; Tang, X.; Gao, F. Advances in CO catalytic oxidation on typical noble metal catalysts: Mechanism, performance and optimization. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, F.; Zhang, X. Electron Beam Irradiation Modified UiO-66 Supported Pt Catalysts for Low-Temperature Ethyl Acetate Catalytic Degradation. Catalysts 2025, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, M.B.; Ali, L.; Shittu, T.; Khaleel, A.; Vermeire, F.H.; Altarawneh, M. Non-noble catalysts formulations using CuO-CeO2/Nb2O5 for low-temperature catalytic oxidation of carbon monoxide. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Huang, H.; Liu, X.; Ren, J.; Ma, K.; Pan, Z.; Ding, Z.; Ding, X.; Gao, Z. Screening the activity of single-atom catalysts for the catalytic oxidation of sulfur dioxide with a kinetic activity model. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 11657–11660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Wei, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X. Insight into the Synergistic Effect of Binary Nonmetallic Codoped Co3O4 Catalysts for Efficient Ethyl Acetate Degradation Under Humid Conditions. JACS Au 2025, 5, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Ge, X.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, F.-S. Two-dimensional manganese oxide on ceria for the catalytic partial oxidation of hydrocarbons. Chem. Synth. 2022, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, J.; Qiao, R.; Bi, F.; Zhang, X. Recent progress of cerium-based catalysts for the catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds: A review. Fuel 2025, 399, 135603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Chen, B.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhou, S.-F.; Zhan, G. Metal oxide/CeO2 nanocomposites derived from Ce-benzene tricarboxylate (Ce-BTC) adsorbing with metal acetylacetonate complexes for catalytic oxidation of carbon monoxide. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 21057–21065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Fang, S.; Yao, S. Revealing the differences in CO oxidation activity of Fe-CeO2, Fe2O3, and CeO2 using operando CO2-DRIFTS-MS: Carbonate species and desorption process. J. Alloy. Compd. 2025, 1010, 177414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulleri, J.K.; Singh, S.K.; Yearwar, D.; Saravanan, G.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Labhasetwar, N.K. Morphology Dependent Catalytic Activity of Mn3O4 for Complete Oxidation of Toluene and Carbon Monoxide. Catal. Lett. 2020, 151, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Lyu, Y.-K. Performance and mechanism comparison of manganese oxides at different valence states for catalytic oxidation of NO. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 361, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Bi, F.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X. Degradation of volatile organic pollutants over manganese-based catalysts by defect engineering: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Song, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, M.; Xing, Y. Insight into the effect of oxygen species and Mn chemical valence over MnOx on the catalytic oxidation of toluene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 493, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, B.; Goda, E.S.; Abu Elella, M.H.; Rehman, A.U.; Hong, S.E.; Rondiya, S.R.; Barkataki, P.; Shaikh, S.F.; Al-Enizi, A.M.; El-Bahy, S.M.; et al. One-pot hydrothermal preparation of hierarchical manganese oxide nanorods for high-performance symmetric supercapacitors. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 65, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, M.; Sivaprakash, P.; Sivakumar, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Saravanan, S. Effect of different precursors on structural and luminescence properties of Mn3O4 nanoparticles prepared by co-precipitation method. Mater. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 53, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbrough, R.; Davis, K.; Dawood, S.; Rathnayake, H. A sol–gel synthesis to prepare size and shape-controlled mesoporous nanostructures of binary (II–VI) metal oxides. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 14134–14146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yuan, G.; Hu, J.; Feng, W.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Pang, H. Recent progress in strategies for preparation of metal-organic frameworks and their hybrids with different dimensions. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, C.; Liu, Y.; Shu, H.; Li, S.; Shi, Q.; Luo, X. Evolutionary trends and photothermal catalytic reduction performance of carbon dioxide by MOF-derived MnOx. Fuel 2025, 384, 133949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. Metal–Organic Framework (MOF)-Derived Metal Oxides for Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) of NOx. Molecules 2025, 30, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Guo, L.; Shen, Q.; Bi, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. The application of metal–organic frameworks and their derivatives in the catalytic oxidation of typical gaseous pollutants: Recent progress and perspective. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Mai, Y.; Chen, J. Highly efficient MnOx catalysts derived from Mn-MOFs for chlorobenzene oxidation: The influence of MOFs precursors, oxidant and doping of Ce metal. Mol. Catal. 2023, 551, 113653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Fu, M.; Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Ye, D. Enhanced oxygen vacancies to improve ethyl acetate oxidation over MnOx-CeO2 catalyst derived from MOF template. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 371, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Song, L.; Hou, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N. Enhanced catalytic performance for CO oxidation and preferential CO oxidation over CuO/CeO2 catalysts synthesized from metal organic framework: Effects of preparation methods. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 18279–18288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Zeng, Y.; Yan, D.; Ren, Q.; Lan, B.; Zhong, J.; Liu, B.; Dong, T.; Huang, H. Construction of hollow sphere MnOx with abundant oxygen vacancy for accelerating VOCs degradation: Investigation through operando spectroscopycombined with on-line mass spectrometry. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 673, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Sa, Y.J.; Kim, T.K.; Moon, H.R.; Joo, S.H. A transformative route to nanoporous manganese oxides of controlled oxidation states with identical textural properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 10435–10443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bi, F.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J.; Lv, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, N. The promoting effect of H2O on rod-like MnCeOx derived from MOFs for toluene oxidation: A combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 297, 120393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Ren, J.; Bai, H.; He, P.; Hao, L.; Liu, N.; Chen, B.; Niu, R.; Gong, J. Shape-controlled fabrication of MnO/C hybrid nanoparticle from waste polyester for solar evaporation and thermoelectricity generation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 451, 138534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Lei, Y.; Xue, F.; Wei, T.; Chu, J.; Cui, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, R.; Tang, J.; Qiao, X. Synergistic role of CuO-Cu+ sites and oxygen vacancies on MOF-derived Cu supported CeO2 for enhancing hydrogenation of cyclohexyl acetate to cyclohexanol. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 709, 163840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ye, J.; Han, Y.; Wang, P.; Fei, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Cui, M.; Qiao, X. Defective UiO-67 for enhanced adsorption of dimethyl phthalate and phthalic acid. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 321, 114477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.Q.; Javeria, H.; Nazir, A.; Du, Z.; Keshta, B.E. Enhanced ibuprofen removal from wastewater using Ni-doped ZIF-67 MOF: Synthesis, characterization, and impact of doping on adsorption performance. Environ. Funct. Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, T.; Tian, H.; Zou, D.; Zeng, J.; Chen, S.; Xie, H.; Zhou, G. Effect of pore size distribution of biomass activated carbon adsorbents on the adsorption capacity. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2024, 99, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.; Abid, H.R.; Usman, M.; Ali, M.; Keshavarz, A.; Vahrenkamp, V.; Iglauer, S.; Hoteit, H. Hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane adsorption potential on Jordanian organic-rich source rocks: Implications for underground H2 storage and retrieval. Fuel 2023, 346, 128362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yan, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Y. Flexible Film Constructed by Asymmetrically-Coordinated La1N4Cl1 Moieties on Interconnected Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Nanocages for High-Efficiency Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2313483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Ding, S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhou, D.; Chu, H.; Bi, F.; Zhang, X. Catalytic oxidation of binary VOCs over MnO2 with different crystal structures: Mechanisms of promotion and inhibition. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 382, 135895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Román, E.; González-Cobos, J.; Guilhaume, N.; Gil, S. Toluene and 2-propanol mixture oxidation over Mn2O3 catalysts: Study of inhibition/promotion effects by in-situ DRIFTS. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.M.; Bailey, L.A.; Morgan, D.J.; Taylor, S.H. The Effect of Metal Ratio and Precipitation Agent on Highly Active Iron-Manganese Mixed Metal Oxide Catalysts for Propane Total Oxidation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Deng, B.; Yang, L.; Zou, M.; Chen, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wei, Z.; Chen, K.; Lu, M.; Ying, T.; et al. Influence of residual anions (Cl−, SO42− and NO3−) on Mn2O3 for photothermal catalytic oxidation of toluene. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cao, M.; He, Z.; Qiao, R.; Bi, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Preparation of CeXMn1−XO2 Catalysts with Strong Mn-Ce Synergistic Effect for Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene. Materials 2025, 18, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Men, Y.; Ji, F.; Shi, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Magkoev, T.T.; An, W. Boosting Catalytic Combustion of Ethanol by Tuning Morphologies and Exposed Crystal Facets of α-Mn2O3. Catalysts 2023, 13, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khder, A.E.R.S.; Altass, H.M.; Orif, M.I.; Ashour, S.S.; Almazroai, L.S. Preparation and characterization of highly active Pd nanoparticles supported Mn3O4 catalyst for low-temperature CO oxidation. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019, 113, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampaiah, D.; Velisoju, V.K.; Devaiah, D.; Singh, M.; Mayes, E.L.; Coyle, V.E.; Reddy, B.M.; Bansal, V.; Bhargava, S.K. Flower-like Mn3O4/CeO2 microspheres as an efficient catalyst for diesel soot and CO oxidation: Synergistic effects for enhanced catalytic performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 473, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo-Vélez, N.; Zanella, R. Comparative study of transition metal (Mn, Fe or Co) catalysts supported on titania: Effect of Au nanoparticles addition towards CO oxidation and soot combustion reactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 385, 123848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Guo, Y.; Huang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, C. Enhanced low-temperature CO oxidation over CuO-Co3O4 catalysts promoted with transition metal oxides. Fuel 2025, 403, 136113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Yoon, S.; Song, J.; Kim, J.; An, K.; Cho, S. Selective phase transformation of layered double hydroxides into mixed metal oxides for catalytic CO oxidation. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Dong, C.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xue, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. Effect of the Fe2O3@TiO2 core-shell structure on CO catalytic oxidation and SO2 poisoning resistance. Mol. Catal. 2023, 547, 113308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Fang, S.; Wu, Z.; Gao, E.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Yao, S.; Li, J. Insight into the Metal-Support Interaction of Pt and β-MnO2 in CO Oxidation. Molecules 2023, 28, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, B.; Tylus, W.; Okal, J.; Chęcmanowski, J.; Szczygieł, B. The Pt-NiO catalysts over the metallic monolithic support for oxidation of carbon monoxide and hexane. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 309, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Do-Thanh, C.-L.; Chen, H.; Xu, S.; Lin, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Entropy-stabilized single-atom Pd catalysts via high-entropy fluorite oxide supports. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, F.K.; Hu, H.T.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, B.L.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X.D. Regulation of Ag1Cux/SBA-15 Catalyst for Efficient CO Catalytic Degradation at Room Temperature. Catalysts 2025, 15, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedan, A.F.; Mohamed, A.T.; El-Shall, M.S.; AlQaradawi, S.Y.; AlJaber, A.S. Tailoring the reducibility and catalytic activity of CuO nanoparticles for low temperature CO oxidation. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 19499–19511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N. Factors affecting CO oxidation reaction over nanosized materials: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 2395–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Sun, Q.; Feng, Y.; Hou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, L.; Wei, Z.; Jing, L.; et al. A novel strategy for enhancing resistance to chlorine, water, and sulfur oxide of the Pt/Co-ZSM-5 catalyst by synergistic coupling of acidity and redox sites for the oxidation of multicomponent VOCs. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2025, 378, 125557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.-F.; Ma, J.-M.; Lu, J.-Q.; Song, Y.-P.; Wang, Y.-J. High-surface area CuO–CeO2 catalysts prepared by a surfactant-templated method for low-temperature CO oxidation. J. Catal. 2007, 246, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hou, F.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Yang, Y. A strawsheave-like metal organic framework Ce-BTC derivative containing high specific surface area for improving the catalytic activity of CO oxidation reaction. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 259, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xiang, G.; Chu, G.; Luo, Y. K+-Modified Redox Properties of the CuOx/CeO2 Catalyst for Highly Efficient CO Oxidation. ACS Eng. Au 2022, 2, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Guo, L.; Bi, F.; Ma, S.; Shen, Q.; Qiao, R.; Zhang, X. Insight into the degradation mechanism of mixed VOCs oxidation over Pd/UiO-66(Ce) catalysts: Combination of operando spectroscopy and theoretical calculation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G. Novel insights for simultaneous NOx and CO Removal: Cu+-Sm3+-Ov-Ti4+ asymmetric active site promoting NH3-SCR coupled with CO oxidation reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.H.; Cai, J.Y.; Meng, Y.D.; Li, J.; Liang, W.J.; Fan, X. Loading Eu2O3 Enhances the CO Oxidation Activity and SO2 Resistance of the Pt/TO2 Catalyst. Catalysts 2025, 15, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. In situ electronic modulation of g-C3N4/UiO66 composites via N species functionalized ligands for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.K.; Kumari, S.; Naveena, U.; Deshpande, P.A.; Sharma, S. Insights into the substitutional chemistry of La1−xSrxCo1−yMyO3 (M = Pd, Ru, Rh, and Pt) probed by in situ DRIFTS and DFT analysis of CO oxidation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2022, 643, 118768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-M.; Deng, Y.-Q.; Tian, P.; Shang, H.-H.; Xu, J.; Han, Y.-F. Dynamic active sites over binary oxide catalysts: In situ/operando spectroscopic study of low-temperature CO oxidation over MnOx-CeO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 191, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Cheng, S.; Jiang, Y. High-performance MnOX-CuO catalysts for low-temperature CO oxidation: Metal interaction and reaction mechanism. Mol. Catal. 2025, 576, 114945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, Z.; Gao, E.; Zhu, J.; Yao, S.; Li, J. Revealing the role of oxygen vacancies on α-MnO2 of different morphologies in CO oxidation using operando DRIFTS-MS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 618, 156643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Mo, S.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, P.; Fu, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, L.; Ye, D. In situ DRIFT spectroscopy insights into the reaction mechanism of CO and toluene co-oxidation over Pt-based catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 4538–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Tian, D.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, C.; Luo, Y. Structure dependence and reaction mechanism of CO oxidation: A model study on macroporous CeO2 and CeO2-ZrO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 2016, 344, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moemen, A.A.; Abdel-Mageed, A.M.; Bansmann, J.; Parlinska-Wojtan, M.; Behm, R.J.; Kučerová, G. Deactivation of Au/CeO2 catalysts during CO oxidation: Influence of pretreatment and reaction conditions. J. Catal. 2016, 341, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, K.; Ni, H.; Guan, B.; Zhan, R.; Huang, Z.; Lin, H. Electric field promoted ultra-lean methane oxidation over Pd-Ce-Zr catalysts at low temperature. Mol. Catal. 2018, 459, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Luo, L.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, W. Size-Dependent Reaction Pathways of Low-Temperature CO Oxidation on Au/CeO2 Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Ning, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Wei, G.; Zhang, T. In situ DRIFTS investigation of low temperature CO oxidation over manganese oxides supported Pd catalysts. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 97, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wu, H.; Yildirim, T. Enhanced H2 Adsorption in Isostructural Metal−Organic Frameworks with Open Metal Sites: Strong Dependence of the Binding Strength on Metal Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 15268–15269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).