Abstract

Bio-oil’s high chlorine content severely hinders its application, because of its high corrosivity. Catalytic pyrolysis is an effective method for the dechlorination of bio-oil. Herein, the performances of the acidified-γ-Al2O3 modified with alkaline and alkaline earth metal compounds were investigated. It was found that NaOH was a better loading material than Ca(NO3)2 or Mg(NO3)2 in the support of acidified-γ-Al2O3. The optimal loading amount of NaOH was 5 wt% in the range of 1 wt%–15 wt%, and the better calcination temperature was 600 °C, compared with 800 °C. When catalyzed with Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C), the organic chlorides content in bio-oil from the pyrolysis of corn straw at 500 °C was significantly reduced from 150 ppm to 29 ppm, while the inorganic chlorides content barely changed. NaAlO2 was generated in Na/Al2O3 from the solid-phase reaction between NaOH and Al2O3 by calcination. When Na/Al2O3 (5%,600 °C) and Na2CO3 were both used in two layers in a fixed-bed reactor, the organic and inorganic chlorides in bio-oil simultaneously significantly decreased, respectively, to 57 ppm and 23 ppm. The decrease in chlorides benefits the deep dechlorination of bio-oil by absorption or catalytic hydrodechlorination in a post-treatment process, which reduces the consumption of absorbent or hydrogen.

1. Introduction

Biomass is a renewable energy source with wide applications [1]. Bio-oil, which is produced from the pyrolysis of biomass, has the potential to partially replace petroleum-based automobile fuels or chemicals [2,3]. Through pyrolysis, most of the energy in biomass is transferred to bio-oil, which mainly contains acids, furans, ketones, aromatics, and phenols [4]. The contents of these components strongly depend on the biomass source: shells produce more phenols, hulls yield more aromatics, stalks yield higher amounts of ketones and furans, and pits are preferred for recovering fatty acids [4]. With the rise in temperature, the content of acetic acid in bio-oil increases, and the concentrations of hydrogen and methane in pyrolysis gas increase as well, while the H/C and O/C ratios in char decrease at higher temperatures [5].

The quality of bio-oil can be improved via catalysis during pyrolysis, including the properties like thermal stability, heating value, acidity, and selectivity toward valuable components (e.g., benzene, toluene, xylene, ethene, propene) [6]. The obtained bio-oil can further be upgraded in a post-treatment progress, through the technologies of catalytic hydrotreating (hydrodeoxygenation, a process with external H2 in a pressurized environment) and catalytic cracking (cracking deoxygenation, a process under ambient pressure without external H2) [6]. The hydrodeoxygenation has been extensively investigated, and the catalysts can mainly be classified into the types of supported noble metal catalysts (e.g., Pd/C, Pt/Al2O3-SiO2, Ru/Al2O3, and Ru/TiO2) [7,8,9,10], supported non-noble metal catalysts (e.g., Ni, Co, Fe, and NiCu on various supports such as SiO2, CeO2, MgAl2O4, Cr2O3, and Al-SBA-15) [11,12,13,14,15], metal carbides (e.g., WC, W2C, and Mo2C) [16,17,18] and metal phosphides (Ni2P, WP, MoP, CoP, and FeP) [19,20,21]. Catalytic cracking is not as developed as hydrotreating. It usually leads to lower yields of lighter hydrocarbons in bio-oil, with a severe deposition of coke. Solid acids such as Al2O3 [22,23] and zeolites (e.g., HZSM-5, SAPO-11, SAPO-6, and MgAPO-36) [24,25,26,27] are frequently used as cracking catalysts. Besides the solid acids, some neutral and alkaline materials like ZnO and MgO may also work as cracking catalysts for deoxygenation [22]. These catalysts can also be used in situ during pyrolysis before condensation, to avoid reheating the bio-oil and thus save energy.

Catalytic deoxygenation has been extensively investigated in the past decades. In fact, the significant chlorine (Cl) content in bio-oil is also a major challenge to the application of bio-oil, yet it has not received enough attention so far, although the content of Cl is significantly lower than that of oxygen. The presence of a significant amount of Cl in bio-oil, which migrates from the raw biomass, leads to the high corrosivity of the bio-oil [28,29,30,31]. This causes a severe problem for the hydrodeoxygenation of bio-oil, as the corrosion in the pressurized reactor severely threatens the safety of the process. Therefore, the removal of Cl from bio-oil is very important and needs to be investigated intensively. In situ catalytic dechlorination during pyrolysis is an effective method for reducing the Cl in bio-oil [32].

The Cl in bio-oil may be divided into inorganic chlorine (ClI) and organic chlorine (ClO) [33,34,35,36]. At present, the removal of ClI has been widely investigated, and some alkaline or neutral oxides or salts have been verified to be effective for the removing of ClI, while the studies on ClO are still scarce. Most of the investigations are focused on municipal solid wastes (MSWs), which are a complex mixture of different types of biomass and plastics. In Park et al.’s work [32], the dechlorination of bio-oil in the pyrolysis of sewage sludge was investigated, and the Cl contents in bio-oil were reduced from 498 ppm to 73 ppm and 78 ppm, respectively, using CaO and La2O3. Lopez et al. [37] investigated the dechlorination of a pyrolysis oil derived from a mixed plastic waste. The pyrolysis oils were catalytically cracked in an autoclave at 325 °C. Using red mud, the light fraction of bio-oil was increased with a low content of Cl (<0.1 wt.%). In Cho et al.’s work [38], to absorb the HCl that was formed from the pyrolysis of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) in a mixture of plastic wastes, the substances of calcium oxide, calcium hydroxide, crushed oyster shells, and rice straw were tested. In the experiments without any additive, the contents of Cl in the pyrolysis oils were 350–500 ppm. When the substances of calcium oxide, calcium hydroxide, and crushed oyster shells were applied, the Cl content of the pyrolysis oils decreased to 50 ppm. Liang et al. [39] studied the absorption of HCl with CuOx/Na2CO3. The results showed that the existence of CO2, particularly at a high flow rate, has a negative relationship with the absorption of HCl. Tsubouchi et al. [40] investigated the absorption of HCl with a supported natural soda ash (Na2CO3) for hot gas cleanup at 300–600 °C. It showed that the absorption of HCl was largest at 500 °C, and the absorption extent changed within a narrow range of 60–65%. Generally, the variation in total Cl content in a pyrolytic liquid has been extensively studied in the literature, while the distributions of organic and inorganic chlorides have seldom been discussed, and the mechanistic roles of different types of catalysts are far from clear.

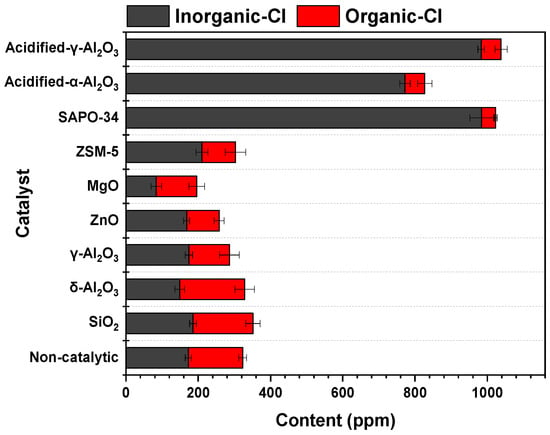

In a previous study conducted by our group [41], the catalytic dechlorination of bio-oil during the pyrolysis of corn straw was investigated. The performances of eight catalysts (δ-Al2O3, γ-Al2O3, acidified-α-Al2O3, acidified-γ-Al2O3, SAPO-34, ZSM-5, ZnO, MgO) comprising acidic, neutral, and alkaline materials were tested. The contents of inorganic and organic chlorides in bio-oil with different catalysts are shown in Figure 1 [41]. It shows that the organic chlorides in bio-oil could be converted highly efficiently using the acidic catalysts of SAPO-34, acidified-α-Al2O3 and acidified-γ-Al2O3; meanwhile, the content of inorganic chlorides in bio-oil was significantly increased (e.g., the ClO content reduced from 150 ppm to 55 ppm, while the ClI content rose from 173 ppm to 983 ppm, under the catalysis of acidified-γ-Al2O3). By contrast, the materials of MgO and ZnO were effective in reducing the content of ClI, but the content of ClO was only slightly decreased (e.g., the ClI content decreased from 173 ppm to 84 ppm, while the ClO content merely reduced from 150 ppm to around 112 ppm under MgO). In brief, the organic and inorganic chlorides in bio-oil could hardly be simultaneously removed high-efficiently by any of the tested catalysts.

Figure 1.

Contents of inorganic and organic chlorides in bio-oil with different catalysts [41].

Usually, the amount of HCl, as the majority of ClI, can be effectively decreased through the co-pyrolysis of organic wastes with alkaline absorbents, such as Ca(OH)2, CaCO3, and Na2CO3, with the formation of chloride salts [42,43]. The ClO in bio-oil is often post-treated by a thermal catalytic hydrodechlorination method (organic chlorides react with H2 at a higher temperature, and the chloride is removed as HCl, usually under the catalysis of a noble metal- or Ni- based material) [44,45]. Comparatively, the removal of ClO is relatively more difficult than that of ClI, so the decrease of ClO during pyrolysis is even more important for bio-oil. Therefore, acidified-γ-Al2O3, with a lower price and better performance in removing ClO, is worthy of further investigation.

In this work, as a continuous investigation of the previous one, the modification of acidified-γ-Al2O3 with alkaline and alkaline earth metal compounds (NaOH, Ca(NO3)2, or Mg(NO3)2) was further studied, to improve the performance of the catalyst in removing both organic and inorganic chlorides from the bio-oil produced from the pyrolysis of corn straw. Herein, NaOH, Ca(NO3)2, and Mg(NO3)2 were selected, because they were typical alkaline and alkaline earth metal compounds with low cost, and Na, Ca, and Mg were active in interacting with Cl. Straw was selected as the research objective, because of its large production and great utilization potential in China (the total theoretical resource of straw in China in 2020 was approximately 7.72 × 108 tons, and corn straw accounted for 31.45% of the total [46]). The influences of the loading material type, the mass percentage of NaOH in the catalyst of Na/Al2O3, and the calcination temperature (600 °C and 800 °C) were investigated, using a lab-scale fixed-bed reactor. The performances of the support and the loading materials in the catalysts were also tested independently for comparison. Based on the optimal catalyst (Na/Al2O3, 5% NaOH, calcined at 600 °C) for the decomposition of organic chlorides, an additional layer of Na2CO3 was placed downstream of the fixed-bed reactor for removing HCl derived from the conversion of organic chlorides, to achieve the simultaneous removal of organic and inorganic chlorides.

In general, most of the studies in the literature focus on the total chlorine content, seldom discussing the types of chlorides (organic or inorganic). Alkaline substances are the most common materials used for the dechlorination in pyrolysis. A plastic mixture or a mixture of biomass and plastics (serving as a model of MSW) is usually used as the raw pyrolysis material for the study of dechlorination, instead of a neat biomass. The water content in a neat biomass pyrolytic liquid is much higher than that of the liquid from plastics, which is prone to pose a higher challenge for catalytic dechlorination. This work emphasizes the distribution and simultaneous removal of organic and inorganic chlorides, rather than the total chlorine content alone, using a specially designed catalyst of the acidified-γ-Al2O3 (with a verified high performance in the removal of ClO) modified with alkaline/alkaline earth metal compounds (effective in removing HCl). A neat biomass (corn straw) is used as the sample for pyrolysis, instead of a mixture of biomass and plastics.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Comparison Among Different Types of Catalysts

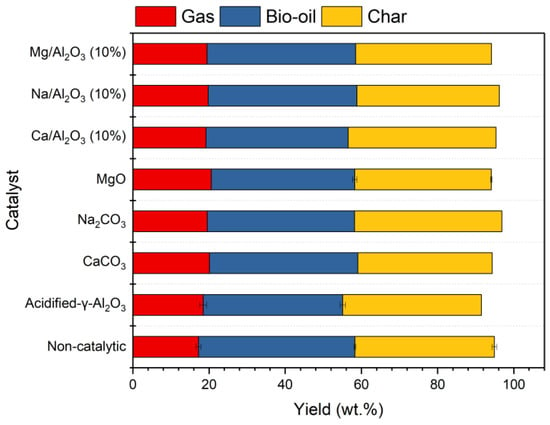

Pyrolysis of corn straw under three multi-component catalysts (Na/Al2O3 (10%), Mg/Al2O3 (10%), and Ca/Al2O3 (10%)) at 500 °C were investigated. An experiment without a catalyst was conducted for reference, and the performances of the support (acidified-γ-Al2O3) and the three loading materials (NaOH, MgCO3, and CaCO3) were also tested for comparison. The yields of bio-oil, char, and non-condensable gas are shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that the catalysts with single or multiple components all have generally weak influences on product yields. Relatively, the gas yields are slightly increased, meanwhile the yields of bio-oil are reduced under the use of all catalysts. This indicates a weak promoting effect of the catalyst on the conversion of bio-oil to gases. In an early study on the deoxygenation of bio-oil [22], Al2O3 (a Lewis acid) and MgO (a solid base) were found to be effective in promoting the conversion of oxygenated organic compounds, leading to the formation of gaseous products (CO, CO2, and H2O). This explains the increase in gas yield and the reduction in bio-oil.

Figure 2.

Yields of gas, liquid, and solid products from the pyrolysis of corn straw with different types of catalysts.

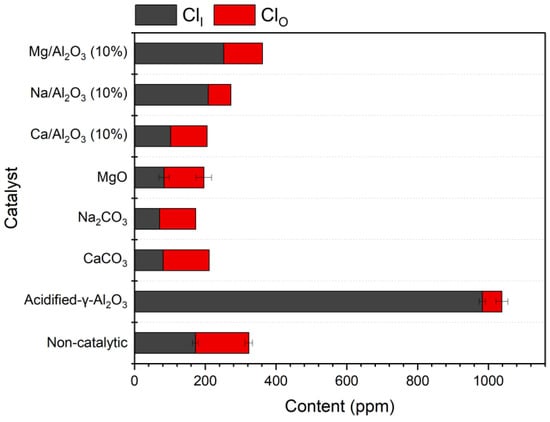

The dechlorination performances of different types of catalysts were investigated and the results are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that the content of ClO is significantly reduced under the catalyst of acidified-γ-Al2O3, while the content of ClI is significantly increased, in comparison with the non-catalytic result. This indicates that the organic chlorides in bio-oil may be converted into HCl as inorganic chloride, which leads to the decrease of ClO in bio-oil. However, the organic chlorides in gas products may also be converted into HCl, which severely increases the content of ClI in bio-oil. By contrast, under the catalysts of MgO, Na2CO3, and CaCO3, the amount of ClI is strongly decreased due to the absorption of HCl, but the ClO content in bio-oil is still high. This indicates that the three alkaline substances cannot significantly promote the conversion of organic chlorides.

Figure 3.

Contents of organic and inorganic chlorides in bio-oil from the pyrolysis of corn straw with different types of catalysts.

When catalyzed with the modified γ-Al2O3 catalysts, the performances strongly depend on the types of the loading metals. In the system of Mg/Al2O3 (10%, 600 °C), neither organic nor inorganic chlorides can be removed from bio-oil with high efficiency, and the content of ClI is even higher than that in the system without a catalyst. Under the Ca/Al2O3 (10%, 600 °C) catalyst, the inorganic chlorides in bio-oil are significantly reduced, but the influence on ClO is very weak. For the catalyst of Na/Al2O3 (10%, 600 °C), the content of ClO in bio-oil is significantly decreased, reaching a level similar to that of acidified-γ-Al2O3, but the catalyst does not significantly influence the removal of ClI. In the three systems of Mg/Al2O3, Ca/Al2O3, and Na/Al2O3, the conversion of ClO to ClI (i.e., HCl) can be promoted by acidified-γ-Al2O3. However, the alkaline or alkaline earth metal reduces the activity of Al2O3, due to the coverage of the acidic surface and the neutralization of the acidified-γ-Al2O3 by solid-phase reaction with the alkaline material during calcination, which hinders the conversion of ClO to ClI. Therefore, the contents of ClI in the systems of the three modified catalysts are not as high as that in the system of acidified-γ-Al2O3. Comparatively, the hindering effects of Ca and Mg are even higher than that of Na, which may be attributed to the larger atomic and spatial sizes of the Ca and Mg compounds in the catalyst, leading to more coverage of the surface of acidified-γ-Al2O3. Consequently, the ClO is less decreased in the systems of Ca/Al2O3 and Mg/Al2O3 than in the Na/Al2O3 system. Generally, Na/Al2O3 (10%, 600 °C) is a better choice, considering its advantage in converting the organic chlorides, although the performance on the removal of ClI is less satisfactory. In the following work, more investigations were conducted on the Na/Al2O3 catalyst.

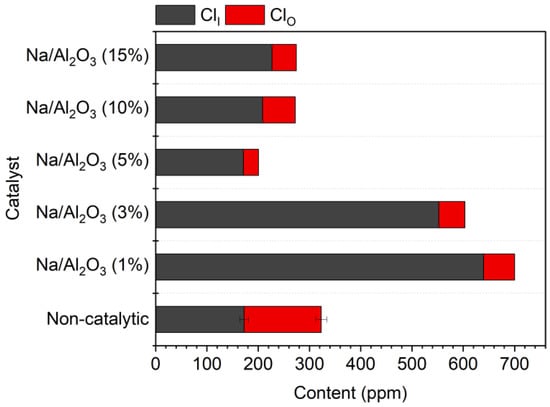

2.2. Optimization for the Performance of Na/Al2O3

The influence of the loading amount of NaOH in the catalyst of Na/Al2O3 was investigated. The corn straw was pyrolyzed under the catalysis of Na/Al2O3 with a varied mass proportion of NaOH in the range of 1–15%. The contents of ClO and ClI in the bio-oil are shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that with the increase in NaOH loading amount, the content of ClI in bio-oil illustrates a V-form variation trend, with the lowest value (171 ppm) appearing at 5%. The contents of ClO and ClT change in a similar tendency as well, and the minimum values of ClO (30 ppm) and ClT (201 ppm) appear at the same NaOH percentage of 5%. Therefore, 5% is determined as the optimal loading amount of NaOH in the Na/Al2O3 catalyst. At the optimal NaOH percentage of 5%, the contents of ClO and ClT are, respectively, reduced by 80.4% and 37.9%, while the content of ClI is still as high as that without a catalyst.

Figure 4.

Contents of organic and inorganic chlorides in bio-oil from the pyrolysis of corn straw under the catalysis of Na/Al2O3 with different NaOH loading percentages.

The reaction mechanisms may be speculated as follows. At a low loading condition (e.g., 1%), the exposed surface area of the acidified-γ-Al2O3 is large, so more ClO is converted into ClI under the catalysis of Al2O3, leading to the increase of ClI in bio-oil. On the other hand, not only the ClO in bio-oil but also the ClO in the gas phase can be converted under the highly active Al2O3 with a low Na loading. The promoted conversion of gaseous ClO occupies some active sites, thus competing with the conversion of ClO in bio-oil, so the content of ClO in bio-oil is not significantly reduced. At a high loading condition (e.g., 10%), too much of the surface of Al2O3 is covered, which severely decreases the active sites of Al2O3, leaving more unreacted ClO in bio-oil. Besides the coverage of the surface of Al2O3, the formation of solid-phase reaction product may also influence the catalyst performance. A Na-Al2O3 compound can be generated in the catalyst after calcination, and there may exist some synergistic effects between the active sites of the new-phase compound and the acidified-γ-Al2O3. The amount of the newly generated Na-Al2O3 compound has a close relation to the synergistic effect, and thus is influential on the selectivity for different products. The V-shaped variation trend of the chlorides indicates the high complexity of the reaction system. More systematic work is necessary in future to verify the speculations.

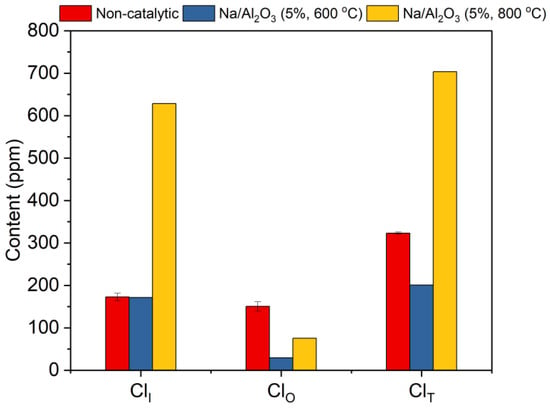

Based on the NaOH loading percentage of 5%, the calcination temperature on the performance of Na/Al2O3 was further investigated. The corn straw was pyrolyzed at 500 °C under the catalysis of Na/Al2O3 calcined at 600 °C and 800 °C. The contents of ClI and ClO in bio-oil are shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that when calcined at 800 °C, the contents of ClI, ClO, and ClT in bio-oil are all higher than those calcined at 600 °C, and even exceed the non-catalytic values of ClI and ClT. This means that an overhigh calcination temperature is not preferred for the dechlorination of bio-oil using the catalyst of Na/Al2O3. On the one hand, the catalyst may sinter under high-temperature calcination, which decreases the catalyst activity in converting the ClO to ClI. On the other hand, the lattice defects of a catalyst may increase at a high temperature, which therefore enhances the activity of the catalyst [47,48]. To be more specific, the Na/Al2O3 calcined at 800 °C has a higher activity in converting ClO to ClI, and is comparatively more effective in promoting the conversion of ClO in the gas phase than in bio-oil, which increases the content of ClI in bio-oil and does not significantly reduce the content of ClO in bio-oil. In addition, the ClI may further react with some liquid components like phenol to produce a product of ClO in bio-oil (the composition of the bio-oil can be found in the early report [22]). This process may be enhanced more significantly by a more active catalyst, which leads to the higher content of ClO in bio-oil over the Na/Al2O3 calcined at 800 °C than that calcined at 600 °C. Therefore, the optimal calcination temperature is determined as 600 °C.

Figure 5.

Contents of organic, inorganic, and total chlorides in bio-oil from the pyrolysis of corn straw under the catalysis of Na/Al2O3 calcined at 600 °C and 800 °C.

2.3. Characterization of Catalyst

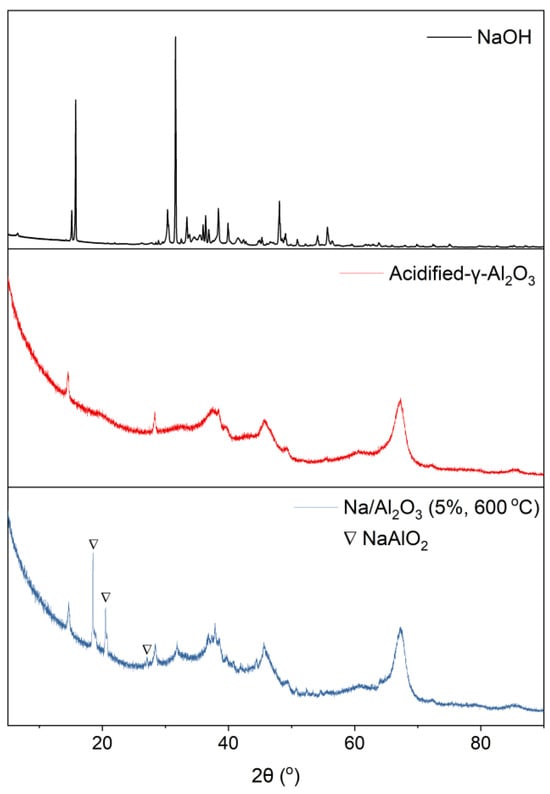

To investigate the existing forms of the Na compounds in Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C), the catalyst was characterized using the XRD method. The support of acidified-γ-Al2O3 and the loading material of NaOH were also analyzed for comparison. The XRD patterns are shown in Figure 6. It can be seen that Al2O3 is the main component, whereas there is almost no NaOH in the catalyst. Instead, a new chemical phase of NaAlO2 as the predominant existing form of Na compounds is identified in the catalyst, which should be generated from the reaction between the support of Al2O3 and the loading material of NaOH (NaOH is a solid base, while Al2O3 is a solid Lewis acid. A solid-state reaction occurs between them upon calcination, generating NaAlO2 as the reaction product). The Na atoms in the catalyst may work as alkaline sites for the selective absorption of chlorides, and thus benefit the dechlorination. Additionally, NaAlO2 is a solid base, so the basicity of NaAlO2 is higher than that of Al2O3. The presence of NaAlO2 with a high alkalinity decreases the general acidity of the catalyst, which weakens the function of the catalyst in promoting the cracking of organic chlorides to HCl. This hinders the conversion of ClO in gas phase to ClI in bio-oil, so the content of ClI in bio-oil obtained under the Na/Al2O3 with 5% NaOH is significantly lower than that with 1% or 3% of NaOH. However, on the other hand, if there exists too much NaAlO2 in the catalyst, like the catalysts with 10% or 15% of NaOH, the conversion of ClO in the gas phase and in bio-oil will be both restricted, which leads to the increase of ClO in bio-oil.

Figure 6.

XRD patterns of NaOH, acidified-γ-Al2O3, and Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C).

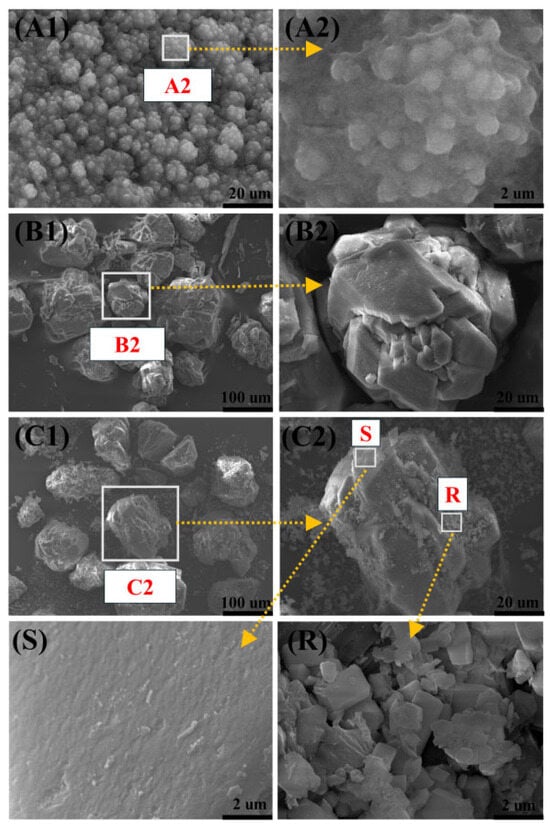

SEM/EDS analysis was conducted to characterize the morphology and the distribution of main elements on the surface of the catalyst. The morphologies of NaOH, acidified-γ-Al2O3, and Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C) are shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that the NaOH particles (~2 μm) are significantly smaller than those of acidified-γ-Al2O3 (~20 μm). For the catalyst of Na/Al2O3 after the solid-phase reaction between NaOH and Al2O3, a lot of small particles appear around the bulk of Al2O3, and the Al2O3 surface seems rougher than before. Table 1 gives the elemental compositions (atom%) of NaOH at position (A2), acidified-γ-Al2O3 at position (B2), and Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C) at position (C2), and the smooth area at position (S) and the rough area at position (R) of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C). It can be seen that the ratio of Na/Al is significantly higher in the smooth area (S) than in the rough area (R), indicating more NaAlO2 in the smooth surface of Na/Al2O3. The content of O atoms is relatively higher in the rough area (R), with smaller amounts of Na and Al atoms, which is in accordance with the higher content of Al2O3, with a higher percentage of O in this area. It should be noted that the amount of O cannot be precisely quantified by the EDS method in principle, so the data herein is merely for semi-quantitation, to illustrate the variations in the elements in different materials or at different surface positions.

Figure 7.

SEM images of NaOH (A1,A2), acidified-γ-Al2O3 (B1,B2), and Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C) (C1,C2), and the smooth (S) and rough (R) areas of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C).

Table 1.

EDS analysis of NaOH (A2), acidified-γ-Al2O3 (B2), and Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C) (C2), and the smooth (S) and rough (R) areas of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C).

2.4. Process with a Layer of Catalyst and a Layer of HCl Absorbent

From the above discussion, it can be seen that the ClO in bio-oil can be effectively removed using the optimal catalyst of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C), whereas the content of ClI in bio-oil is barely changed. To achieve a simultaneous removal of ClO and ClI, a two-layer process (an internal layer of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C) (1 g) and an external layer of Na2CO3 (1 g) are placed in both the top and bottom sides of corn straw in a quartz basket) is investigated. It is expected that the ClO in the pyrolytic volatile can be converted into HCl under the catalyst of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C), and then the HCl is absorbed by the layer of Na2CO3. Another experiment with only one layer of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C) but double the amount (2 g) was also conducted, to make a comparison with the two-layer process.

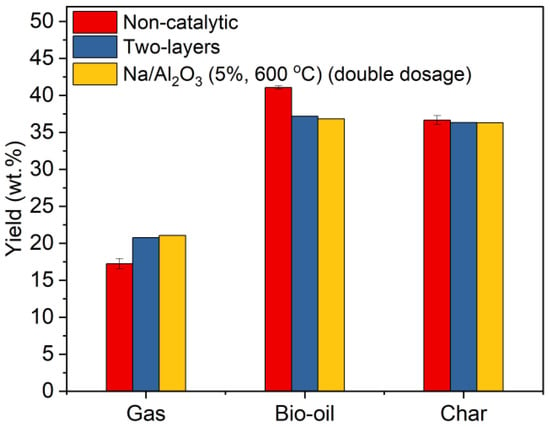

Pyrolysis is conducted at 500 °C and the yields of gas, liquid, and solid products are shown in Figure 8. It can be seen that the yields of all products in the two-layer mode are quite similar to those with one layer of the double-dosed Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C). Compared with the non-catalytic results, the gas yields in the two catalytic processes both increased; meanwhile, the yields of bio-oil were reduced, while the yields of char were generally at the same level for the two catalytic modes. This verifies the catalytic role of Na/Al2O3 in promoting the cracking of the volatiles to gases in any of the two catalytic modes. The substances, including acidified-γ-Al2O3, NaAlO2, and Na2CO3, are either Lewis acids or solid bases. These types of species have been found to be effective in promoting the deoxygenation of bio-oil (i.e., the conversion of organic oxides to CO, CO2, and H2O), which thereby increases the gas yield and meanwhile reduces the yield of bio-oil [22,23,49,50].

Figure 8.

Yields of the pyrolysis products of corn straw without a catalyst, with two layers of Na/Al2O3 and Na2CO3, and with one layer of Na/Al2O3 in double dosage.

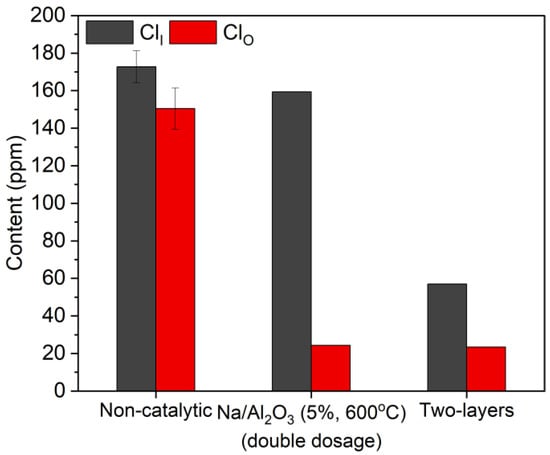

The contents of ClI and ClO in bio-oil were also compared, among the cases without catalyst, with two layers of Na/Al2O3 and Na2CO3 in equal mass, and with one layer of Na/Al2O3 in double dosage. The results are shown in Figure 9. It can be seen that the contents of ClO are nearly the same between the two catalytic modes with one or two layers of catalyst, and the two values are both significantly lower than that without a catalyst. This indicates that the layer of Na2CO3 has almost no influence on the conversion of ClO, and the removal of ClO is mainly attributed to Na/Al2O3. The content of ClI in bio-oil with one layer of catalyst is merely slightly lower than that without a catalyst, while the value of the two-layer process is significantly decreased, which verifies the high performance of Na2CO3 in absorbing HCl from the hot volatiles. In general, in the two-layer process, the contents of ClI, ClO, and ClT in bio-oil are lowest, with the respective values of 57.0 ppm, 23.4 ppm, and 80.4 ppm, and the corresponding dechlorination efficiencies are 67.0%, 84.4%, and 75.1%, in comparison with the non-catalytic values.

Figure 9.

Contents of ClI and ClO in bio-oil from the pyrolysis of corn straw without a catalyst, with two layers of Na/Al2O3 and Na2CO3, and with one layer of Na/Al2O3 in double dosage.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Corn straw was used as the feed stock for pyrolysis. Before the experiment, the sample was first crushed (<200 mesh) and then dried at 105 °C for 4 h. The proximate and ultimate analysis of the raw material are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Proximate and ultimate analysis of the corn straw.

The catalyst was prepared using the incipient-wetness impregnation method. A measured amount of NaOH, Ca(NO3)2, and Mg(NO3)2 (all purchased from Sinopharm, Beijing, China) was dissolved in deionized water to prepare the impregnation solution. The solution was then homogenously added dropwise onto the acidified-γ-Al2O3, followed by vigorous stirring for 5 min. After impregnation, the catalyst precursors were dried at 105 °C for 8 h and then calcined at 600 °C or 800 °C for 4 h by 20 °C/min. The prepared catalyst was named Met./Al2O3 (x%, y °C), where the symbol Met. indicates the metals of Na, Ca, and Mg, the x% represents the mass percentages of NaOH, Ca(NO3)2, and Mg(NO3)2 (x = 1, 3, 5, 10, 15) in the catalysts, and the y °C indicates the calcination temperature (y = 600 or 800). If not otherwise specified, the catalyst was calcined at 600 °C.

3.2. Experimental Procedural

The tubular reactor was first heated to 500 °C and stabilized at that temperature for 20 min in a N2 atmosphere (50 mL/min). A quartz basket containing 2.4 g corn straw and 1.0 g catalyst powders (the catalyst powders were equally located on both the top and bottom of the corn straw layer) was put into a tubular reactor (length of 590 mm and inner diameter of 26 mm). It should be noted that although the N2 carrier gas flows along the reaction tube, volatiles may still be released simultaneously from the top and bottom sides of the corn straw layer. Therefore, the catalyst powders were placed both above and below the corn straw to ensure good contact between the catalyst and all volatiles. The mass of corn straw (2.4 g) was determined by the volume of the quartz basket (for holding the straw), and the quantity of the catalyst (1 g) could fully cover the top and bottom sides of the straw.

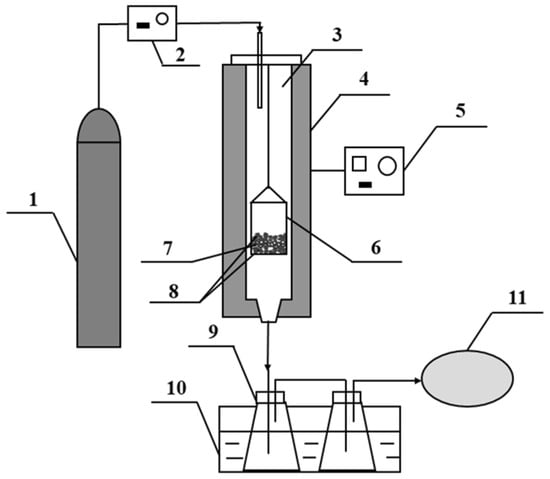

The pyrolysis of the corn straw started and the produced volatiles were transported via the N2 carrier gas to a condensing unit (−10 °C, controlled using a constant temperature bath with an aqueous solution of ethylene glycol as the cooling medium), where the condensed bio-oil was trapped in bottles, and the non-condensable gas was collected in a gasbag. After reaction (60 min for each run), the char in the quartz basket and the bio-oil in bottles were weighed. The diagram of the experimental equipment is shown in Figure 10. An experiment with two layers of bed materials (a layer of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C) for catalytic decomposition of organic chlorides and a layer of Na2CO3 for HCl absorption) was also conducted. The powders of Na2CO3 (1 g) were equally located on both the top and bottom sides of the Na/Al2O3 catalyst.

Figure 10.

Fixed-bed reactor for pyrolysis of corn straw. 1. N2 cylinder; 2. Mass flowmeter; 3. Quartz tubular reactor; 4. Tubular oven; 5. Temperature controller; 6. Quartz basket; 7. Corn straw; 8. Two layers of catalyst (with or without two external layers of Na2CO3); 9. Glass bottles for liquid collection; 10. Cooling pool; 11. Gasbag.

3.3. Product Analysis

The contents of total chlorine (ClT) and ClI in bio-oil were analyzed by two types of micro-coulometric titration analyzers (MCT). MCT-I (WC-200, Jiangfen, China [51]) and MCT-T (WK-2000, Jiangfen, China [52]) were, respectively, used for the quantifications of ClI and ClT. Prior to measurement, 0.1 g of bio-oil was mixed with 10 mL of deionized water and vigorously shaken for 30 min to ensure thorough mixing. The chloride content in the resulting homogeneous solution was then measured using the MCT-I instrument. MCT-T consists of a combustion chamber, a drying bottle, and an MCT-I. In the combustion chamber, ClT in bio-oil was converted into gaseous ClI at a high temperature (1000 °C). The carrier gas transported the gaseous ClI through a drying bottle filled with concentrated sulfuric acid to remove moisture. The outlet of the drying bottle was connected to the MCT-I, which was used for ClI determination. The content of ClO was calculated from the difference between ClT and ClI.

The crystal phases of the optimal catalyst were characterized by X-ray diffraction spectrometry (XRD, Smartlab, Rigaku, Japan). The morphology of the catalyst with the elemental distribution on the catalyst surface was analyzed using electron microscopy-energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS, SU8020, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

3.4. Data Processing

The yields of gas, bio-oil, and char were defined as the ratio of the mass of a product to the mass of corn straw (wt.%).

where i indicates the products of gas, bio-oil, and char; mi represents the mass of product i; and mcorn straw indicates the mass of corn straw for pyrolysis.

The contents of ClO and ClI in bio-oil were defined as follows:

where Clk indicates ClO or ClI; indicates the mass of Clk in bio-oil; and mbio-oil indicates the mass of bio-oil.

4. Conclusions

The high content of chlorine in bio-oil severely hinders its application because of its high corrosivity. In this work, a catalyst composed of the acidic support of acidified-γ-Al2O3 and a loading material of NaOH, Ca(NO3)2, or Mg(NO3)2 was prepared and evaluated. It was found that NaOH is a better loading material than Ca(NO3)2 or Mg(NO3)2. The optimal loading amount of NaOH is 5 wt% in the range of 1 wt%–15 wt%, and the better calcination temperature is 600 °C, compared with 800 °C. With the optimal catalyst of Na/Al2O3 (5%, 600 °C), the content of organic chlorides in bio-oil from the pyrolysis of corn straw at 500 °C was significantly reduced from 150 ppm to 29 ppm, while the inorganic chlorides barely changed. A new chemical phase of NaAlO2 was identified as the predominant form of the Na compounds in Na/Al2O3, generated from the solid-phase reaction between NaOH and Al2O3 by calcination. When Na/Al2O3 (5%,600 °C) and Na2CO3 were both used in two layers in a fixed-bed reactor, respectively, as the dechlorination catalyst and the absorbent of HCl, the contents of inorganic chlorides and organic chlorides in bio-oil were observed to be significantly decreased to 57 ppm and 23 ppm, with corresponding dechlorination efficiencies of 67.0% and 84.4%, in comparison with the non-catalytic values. The simultaneous reduction in organic and inorganic chlorides facilitates the deep dechlorination of bio-oil in the subsequent post-treatment stage via absorption or catalytic hydrodechlorination, which reduces the consumption of absorbents or hydrogen. The dechlorination performance of the catalyst may be associated with the surface coverage of acidified-γ-Al2O3, the synergistic effect between acidified-γ-Al2O3 and the newly generated Na/Al2O3, and the perfection and defects of the crystal lattice formed under different calcination temperatures. Detailed catalytic mechanisms are to be systematically investigated in future work.

Author Contributions

W.Z.: Investigation, Data processing, Writing—original draft; Z.W.: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Review and Editing; S.L.: Supervision, Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the project from the State Key Laboratory of Mesoscience and Engineering, IPE, CAS (2024, MESO-24-A06).

Data Availability Statement

All data will be made available as published and as requested through the corresponding author’s contacts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Motghare, K.A.; Rathod, A.P.; Wasewar, K.L.; Labhsetwar, N.K. Comparative Study of Different Waste Biomass for Energy Application. Waste Manag. 2016, 47, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, S.; Shahbazi, A. Bio-Oil Production and Upgrading Research: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 4406–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gholizadeh, M. Progress of the Applications of Bio-Oil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brebu, M.; Ioniță, D.; Stoleru, E. Thermal Behavior and Conversion of Agriculture Biomass Residues by Torrefaction and Pyrolysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlonka-Mędrala, A.; Evangelopoulos, P.; Sieradzka, M.; Zajemska, M.; Magdziarz, A. Pyrolysis of Agricultural Waste Biomass towards Production of Gas Fuel and High-Quality Char: Experimental and Numerical Investigations. Fuel 2021, 296, 120611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvartzides, S.; Charisiou, N.D.; Wang, W.; Papadakis, V.G.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Goula, M.A. Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Agricultural Residues and Dedicated Energy Crops for the Production of High Energy Density Transportation Biofuels. Part I: Chemical Pathways and Bio-Oil Upgrading. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildschut, J.; Mahfud, F.H.; Venderbosch, R.H.; Heeres, H.J. Hydrotreatment of Fast Pyrolysis Oil Using Heterogeneous Noble-Metal Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 10324–10334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, W.; Balfanz, U.; Rupp, M. Upgrading of Flash Pyrolysis Oil and Utilization in Refineries. Biomass Bioenergy 1994, 7, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, Y.H.E.; Anthony, R.G.; Soltes, E.J. Kinetic Studies of Upgrading Pine Pyrolytic Oil by Hydrotreatment. Fuel Process. Technol. 1988, 19, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbosch, R.H.; Ardiyanti, A.R.; Wildschut, J.; Oasmaa, A.; Heeres, H.J. Stabilization of Biomass-derived Pyrolysis Oils. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcese, R.N.; Bettahar, M.; Petitjean, D.; Malaman, B.; Giovanella, F.; Dufour, A. Gas-Phase Hydrodeoxygenation of Guaiacol over Fe/SiO2 Catalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 115, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, V.A.; Khromova, S.A.; Sherstyuk, O.V.; Dundich, V.O.; Ermakov, D.Y.; Novopashina, V.M.; Lebedev, M.Y.; Bulavchenko, O.; Parmon, V.N. Development of New Catalytic Systems for Upgraded Bio-Fuels Production from Bio-Crude-Oil and Biodiesel. Catal. Today 2009, 144, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, P.M.; Grunwaldt, J.D.; Jensen, P.A.; Jensen, A.D. Screening of Catalysts for Hydrodeoxygenation of Phenol as a Model Compound for Bio-Oil. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Ma, L.; Yu, Y.; Chen, L. Hydrodeoxygenation of Lignin-Derived Phenolic Compounds to Hydrocarbons over Ni/SiO2–ZrO2 Catalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 134, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Uemura, Y.; Ramli, A. Hydrodeoxygenation of Guaiacol over Al-MCM-41 Supported Metal Catalysts: A Comparative Study of Co and Ni. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.B.; Boudart, M. Platinum-like Behavior of Tungsten Carbide in Surface Catalysis. Science 1973, 181, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, C.J.; Luc, W.; Chen, J.G.; Bhan, A.; Jiao, F. Ordered Mesoporous Metal Carbides with Enhanced Anisole Hydrodeoxygenation Selectivity. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3506–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongerius, A.L.; Gosselink, R.W.; Dijkstra, J.; Bitter, J.H.; Bruijnincx, P.C.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Carbon Nanofiber Supported Transition-metal Carbide Catalysts for the Hydrodeoxygenation of Guaiacol. ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 2964–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Gong, J.; Song, H.L.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.G. Preparation of Core-Shell Structured Ni2P/Al2O3@ TiO2 and Its Hydrodeoxygenation Performance for Benzofuran. Catal. Commun. 2016, 85, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, A.; Sankaranarayanan, T.M.; Gómez, G.; Moreno, I.; Coronado, J.M.; Pizarro, P.; Serrano, D.P. Evaluation of Transition Metal Phosphides Supported on Ordered Mesoporous Materials as Catalysts for Phenol Hydrodeoxygenation. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, Y.; Richard, F.; Renème, Y.; Brunet, S. Hydrodeoxygenation of Benzofuran and Its Oxygenated Derivatives (2, 3-Dihydrobenzofuran and 2-Ethylphenol) over NiMoP/Al2O3 Catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2009, 353, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Ge, T.; Yang, C.; Song, W.; Li, S.; Ma, R. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Corn Straw for Deoxygenation of Bio-Oil with Different Types of Catalysts. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhu, G.; Lv, T.; Kang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Z.; Xu, L. Sustainable Production of Aromatic-Rich Biofuel via Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Lignin and Waste Polyoxymethylene over Commercial Al2O3 Catalyst. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 174, 106147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Bakhshi, N.N. Catalytic Upgrading of Pyrolysis Oil. Energy Fuel 1993, 7, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katikaneni, S.P.R.; Adjaye, J.D.; Bakhshi, N.N. Performance of Aluminophosphate Molecular Sieve Catalysts for the Production of Hydrocarbons from Wood-Derived and Vegetable Oils. Energy Fuel 1995, 9, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjaye, J.D.; Katikaneni, S.P.R.; Bakhshi, N.N. Catalytic Conversion of a Biofuel to Hydrocarbons: Effect of Mixtures of HZSM-5 and Silica-Alumina Catalysts on Product Distribution. Fuel Process. Technol. 1996, 48, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjaye, J.D.; Bakhshi, N.N. Production of Hydrocarbons by Catalytic Upgrading of a Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oil. Part I: Conversion over Various Catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 1995, 45, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Li, X.; Luo, J.; Yu, X. Fate of Chlorine in Rice Straw under Different Pyrolysis Temperatures. Energy Fuel 2019, 33, 9272–9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, J.M.; Aho, M.; Paakkinen, K.; Taipale, R.; Egsgaard, H.; Jakobsen, J.G.; Frandsen, F.J.; Glarborg, P. Release of K, Cl, and S during Combustion and Co-Combustion with Wood of High-Chlorine Biomass in Bench and Pilot Scale Fuel Beds. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013, 34, 2363–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wang, X.; Shao, J.; Yang, H.; Xu, G.; Chen, H. Releasing Behavior of Chlorine and Fluorine during Agricultural Waste Pyrolysis. Energy 2014, 74, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, H. Release and Transformation Characteristics of K and Cl during Straw Torrefaction and Mild Pyrolysis. Fuel 2016, 167, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Heo, H.S.; Park, Y.K.; Yim, J.H.; Jeon, J.K.; Park, J.; Ryu, C.; Kim, S.S. Clean Bio-Oil Production from Fast Pyrolysis of Sewage Sludge: Effects of Reaction Conditions and Metal Oxide Catalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, S83–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.A.; Frandsen, F.J.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Sander, B. Experimental Investigation of the Transformation and Release to Gas Phase of Potassium and Chlorine during Straw Pyrolysis. Energy Fuel 2000, 14, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yu, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, X.; Luo, Z. Investigation on K and Cl Release and Migration in Micro-Spatial Distribution during Rice Straw Pyrolysis. Fuel 2016, 167, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Gao, X.; Qiao, Y. Effects of Secondary Vapor-Phase Reactions on the Distribution of Chlorine Released from the Pyrolysis of KCl-Loaded Wood. Energy Fuel 2020, 34, 11717–11721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.U.; Chunjiang, Y.U.; Jisong, B.; Lianming, L.; Fang, H. Mechanism Study of Chlorine Release During Biomass Pyrolysis. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2013, 33, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Urionabarrenechea, A.; Marco, I.; Caballero, B.M.; Laresgoiti, M.F.; Adrados, A. Upgrading of Chlorinated Oils Coming from Pyrolysis of Plastic Waste. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 137, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.H.; Jung, S.H.; Kim, J.S. Pyrolysis of Mixed Plastic Wastes for the Recovery of Benzene, Toluene, and Xylene (BTX) Aromatics in a Fluidized Bed and Chlorine Removal by Applying Various Additives. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Liu, S.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Guo, M.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, M. Enhanced HCl Removal from CO2-Rich Mixture Gases by CuOx/Na2CO3 Porous Sorbent at Low Temperature: Kinetics and Forecasting. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubouchi, N.; Fukuyama, K.; Matsuoka, N.; Mochizuki, Y. Removal of Hydrogen Chloride from Simulated Coal Gasification Fuel Gases Using Honeycomb-Supported Natural Soda Ash. Fuel 2022, 317, 122231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Ge, T.; Song, W.; Li, S. Migration of Cl in the Process for Pyrolysis of Corn Straw and the Influence of Catalysis for Dechlorination of Bio-Oil. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 14, 6773–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttiyathil, M.S.; Ali, L.; Teoh, W.Y.; Altarawneh, M. Dechlorination of Waste Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) via Its Co-Pyrolysis with Ca(OH)2: A TG-IR-GCMS Investigation. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Sanchez Monsalve, D.A.; Clough, P.; Jiang, Y.; Leeke, G.A. Understanding the Dechlorination of Chlorinated Hydrocarbons in the Pyrolysis of Mixed Plastics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 1576–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flid, M.R.; Kartashov, L.M.; Treger, Y.A. Theoretical and Applied Aspects of Hydrodechlorination Processes—Catalysts and Technologies. Catalysts 2020, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Otero, J.A.; Martin-Martinez, M.; Rodriguez-Franco, D.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Gómez-Sainero, L.M. Understanding Hydrodechlorination of Chloromethanes. Past and Future of the Technology. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.W.; Xing, F.; Zhu, J.C.; Li, R.H.; Zhang, Z.Q. Temporal and Spatial Distribution, Utilization Status, and Carbon Emission Reduction Potential of Straw Resources in China. Environ. Sci. 2023, 44, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Shan, W. High-Temperature Calcination Enhances the Activity of MnOx Catalysts for Soot Oxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 6278–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Shan, W.; He, H. High-Temperature Calcination Dramatically Promotes the Activity of Cs/Co/Ce-Sn Catalyst for Soot Oxidation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109928. [Google Scholar]

- Ramzy, K.; Ismail, T.; Alswat, M.; El-Askary, W.A. Effect of Using Zeolite as a Catalyst on Syngas Produced from Different Wastes Using Pyrolysis Technology. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 65, 103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirapanampai, C.; Phetwarotai, W.; Phusunti, N. Effect of Temperature and the Content of Na2CO3 as a Catalyst on the Characteristics of Bio-Oil Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Microalgae. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 142, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinopec Research Institute of Petroleum Processing, Daqing Oilfield Engineering Co., Ltd., Tarim Oilfield Exploration & Development Research Institute of Sinopec {Pei He, Shuqing Wang, Shouguo Song, Zhangling Li}. SY/T 0536-2008; Determination of Salt Content in Crude Petroleum—Coulometric Titration Method. Petroleum and Gas Industry Standards of the People’s Republic of China; National Development and Reform Commission: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Daqing Oilfield Architectural Design & Research Institute {Xuejun Yang, Xuezhi Hou, Shusheng Ge, Hong Zhang, Guangping Pan, Jing Chen}. GB/T 18612-2001; Determination of Organic Chloride Content in Crude Oil by Combustion and Microcoulometry. National Standards of the People’s Republic of China; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2001.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).