Abstract

Naproxen (NPX), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, is considered an emerging contaminant due to its persistence and potential environmental risks. In this study, NPX degradation was investigated through ozonation using nickel–iron foam (NiFeF) and NiO-modified NiFeF (NiO/NiFeF). The effect of the foam size was investigated using three configurations: S1 (1 cm × 2.5 cm), S2 (2 cm × 2.5 cm), and S3 (2 cm × 5 cm). Complete NPX removal was achieved in all systems, with degradation times of 4 min for ozonation alone, 2 min for NiFeF-S1, and 1 min for NiO/NiFeF-S2 and NiO/NiFeF-S3. The NiO/NiFeF catalyst was synthesized via ultrasonic spray pyrolysis, resulting in a porous structure with abundant active sites. Compared with conventional ozonation, NiO/NiFeF-S1 improved the total organic carbon (TOC) removal rate by 6.2-fold and maintained 87.5% of its activity after five reuse cycles, demonstrating excellent stability. High-resolution mass spectrometry revealed that catalytic ozonation generated fewer by-products (22 vs. 27 for ozonation alone) and promoted more selective pathways, including demethylation, ring-opening oxidation, and partial mineralization to CO2 and H2O. This enhanced performance is attributed to the synergy between NiO and NiFeF, which facilitates reactive oxygen species generation and electron transfer. These results demonstrate the potential of NiO/NiFeF as an efficient and stable catalyst for pharmaceutical removal from water.

1. Introduction

Technical advances and industrial development have intensified environmental pollution due to the continuous release of toxic compounds into water, air and soil. Among these pollutants, emerging contaminants (ECs), which are synthetic or naturally occurring compounds that are not routinely monitored, have drawn increasing attention because of their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and adverse effects on ecosystems and human health [1]. ECs include pharmaceuticals, personal care products, hormones, pesticides, and industrial additives, many of which are poorly removed by conventional wastewater treatment processes, leading to their continuous accumulation in aquatic environments. The presence of ECs has been linked to endocrine disruption in aquatic organisms, antibiotic resistance, and potential genotoxicity in humans.

Among ECs, pharmaceutical compounds are of particular concern due to their widespread use in maintaining animal and human health. The pharmaceutical industry produces significant quantities of toxic effluents that are often discharged through hospital wastewater, manufacturing plants, and domestic sewage systems [2,3]. In particular, naproxen (NPX), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory properties, has been detected in surface waters across several Latin American countries (e.g., Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador) [4,5]. In many cases, its concentration exceeds the predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) of 0.15 mg L−1 for human health as defined by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) [6].

Several physicochemical methods have been applied for NPX removal from aqueous solutions, including photocatalysis [7,8], UV photolysis [9,10], sonocatalysis [11], and Fenton-based reaction [12]. While some of these technologies are effective, many suffer from high energy demands, secondary waste generation, and limited mineralization efficiency.

Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation (HCO), a type of advanced oxidation process (AOP), has emerged as an effective approach for degrading persistent organic pollutants in water [13,14]. This method relies on the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including free radicals (•OH and O2•−) and non-radicals (1O2, and *O2), which promote fast and non-selective degradation [15]. Generally, transition metal oxides have shown good catalytic activity, but their recovery (in powder form) after treatment can be complicated and may lead to secondary pollution [16]. To overcome this limitation, catalyst immobilization on solid supports such as thin films, membranes, and coated spheres has been proposed. For instance, NiO films deposited on glass substrates by the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) have been used for NPX degradation, achieving 45% total organic carbon (TOC) removal compared to 35% with conventional ozonation [17].

Three-dimensional metallic foams have gained increasing interest because of their high porosity, low density, thermal stability, reusability, and low cost [18,19]. These structures are suitable for catalyst immobilization and facilitate mass transfer during water treatment. Their applications include fuel cells [20], sensors [21], gas filters and wastewater treatment [22,23]. Foam-based catalysts offer multiple advantages: (a) they not only act as a macro substrate to immobilize the catalyst but also provide active sites (transition metal), (b) allow physical separation from the treated effluent by mechanical lifting, and (c) enable improved flow and diffusion properties. Several recent works have demonstrated the efficacy of foam-based catalysts in HCO systems [24,25].

Some studies have explored Ni-based catalysts supported on nickel foam for catalytic ozonation. C. Feng et al. [19] developed a NiFe2O4–NiO/NF hybrid through a hydrothermal–annealing process, achieving over 96% decolorization of methyl orange within 20 min. S. Zhan et al. [26] synthesized NF@NiO via an oxalic acid-assisted hydrothermal route, obtaining 95% toluene removal and 74% mineralization efficiency. H. Wang et al. [27] reported 91.6% bioaerosol inactivation using MnO2/Ni foam, while S. Zhou et al. [28] achieved 85.6% TOC removal of p-nitrophenol with Co-doped Ni3S2/Ni foam. Similarly, L. Zhu et al. [22] attained 88.2% mineralization of p-nitrophenol using Cu2S/Ni3S2/Ni foam by ozone, and W. Yao et al. [29] applied LaMnO3-loaded ceramic foam to remove tetracycline, reaching 51.3% mineralization in 120 min. S. Tian et al. [30] fabricated 3D–NiO1–δ/NF catalysts by electrodeposition, achieving complete toluene degradation with enhanced durability.

In contrast, our study focuses on the degradation of naproxen, a pharmaceutically active emerging contaminant that has been rarely investigated in previous Ni-based catalytic ozonation systems. The NiO/NiFeF catalyst, synthesized via ultrasonic spray pyrolysis, offers a simpler, one-step, and scalable alternative to conventional multi-step fabrication routes.

Building on previous research, metallic foams have been proven to be promising supports for the development of composite catalysts with high activity and convenient post-treatment handling [31]. Their three-dimensional, open-cell structure facilitates mass transfer and eliminates the need for filtration or centrifugation, thereby reducing operational costs.

In this study, NiO was synthesized by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis (USP) and directly deposited onto nickel–iron foam (NiFeF). The resulting catalyst was applied for the catalytic ozonation of NPX in aqueous solution. The effects of NiO deposition and foam size on the catalytic performance were systematically investigated. Furthermore, the degradation pathway was elucidated through by-product identification, and the relationship between the catalyst structure and its degradation efficiency was analyzed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Evaluation of the Catalytic Activity of NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF in NPX Ozonation

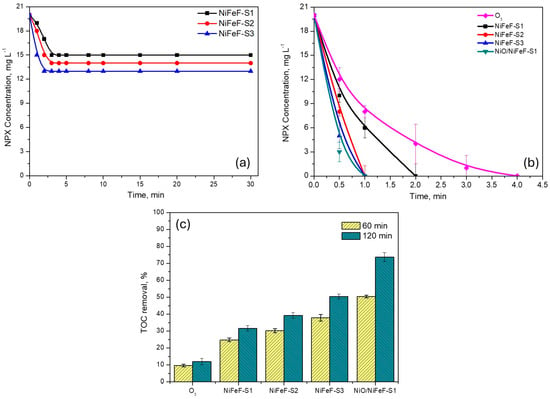

Adsorption experiments were conducted to evaluate the effect of NiFeF piece size on NPX removal. As shown in Figure 1a, NPX adsorption increased with foam size, following the trend S1 (25%) < S2 (30%) < S3 (35%) in 4 min. After this time, the NPX concentration remained constant, indicating that adsorption equilibrium had been reached.

Figure 1.

(a) Adsorption and (b) removal rate of NPX in the presence of the NiFeF (varying the size of the piece). (c) TOC removal of NPX in different systems. Experimental conditions: [O3] = 11 mg L−1, catalyst dosage = 1 piece, [NPX] = 20 mg L−1.

Figure 1b shows the NPX concentration profile for the three NiFeF piece sizes. NPX degradation was rapid in both catalytic and non-catalytic systems, with complete removal achieved within approximately 2 min. Notably, despite the moderate adsorption percentages, catalytic ozonation effectively eliminated NPX from the solution in shorter times, indicating that the process removes the pollutant before adsorption becomes significant.

Although the catalytic effect was not apparent in the NPX concentration profile, it is clearly reflected in the TOC results, as shown in Figure 1c. In the absence of a catalyst (i.e., conventional ozonation), TOC removal reached only 9.6% after 60 min and 11.9% after 120 min. In contrast, the use of NiFeF-S3 enhanced TOC removal to 37.9% at 60 min and 50.4% at 120 min. Even the smallest foam sample (NiFeF-S1) significantly outperformed the non-catalytic process, achieving 31.7% TOC removal after 120 min. The mineralization efficiency followed the order: NiFeF-S1 (31.7%) < NiFeF-S2 (39.2%) < NiFeF-S3 (50.4%) at 120 min. Increasing the catalyst size by a factor of four (from S1 to S3) led to a 1.53-fold increase in TOC removal at 60 min and a 1.60-fold increase at 120 min, indicating a proportional relationship between catalyst surface area and mineralization efficiency.

Additionally, extending the ozonation time from 60 to 120 min improved TOC removal by an average factor of 1.3 in all NiFeF systems. Based on these results, NiFeF-S1 was selected as the substrate for NiO deposition. Although NiFeF-S3 provides a surface area approximately four times larger than S1, the difference in TOC removal was only 18.7%, indicating that S1 exhibited higher catalytic efficiency per unit area.

NiO supported on NiFeF-S1 catalyst (NiO/NiFeF-S1) further enhanced catalytic performance, achieving 73.7% TOC removal at 120 min, more than twice that of the uncoated NiFeF-S1. This enhancement is attributed to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via catalytic ozone decomposition, facilitated by NiO. Moreover, the incorporation of NiO increases the density of Lewis acid sites on the catalyst surface, which plays a key role in promoting ozone decomposition in HCO [32]. These effects are corroborated by the characterization data presented in Section 2.2.

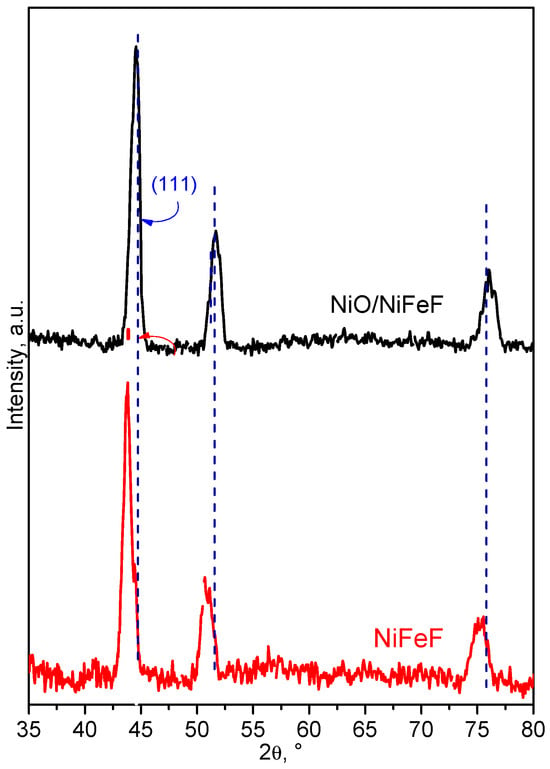

2.2. Crystalline Structure of NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF composite are shown in Figure 2. The pristine NiFeF sample exhibited characteristic peaks at 43.7°, 50.6° and 74.9° corresponding to the (111), (200), and (220) planes of bulk FeNi alloy, in agreement with JCPDS card 96-901-1507. Additionally, a distinct peak at 44.5° is assigned to the (110) planes of body-centered cubic (BCC) iron, according to JCPDS No. 987-018-5729. Other expected Fe-related reflections were not observed, likely due to low crystallinity or peak overlap (see Figure S1). It is worth noting that NiFeF is a Ni–Fe alloy with a higher nickel content than iron, which explains the greater intensity of Ni-related peaks [33].

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF.

Upon deposition of Ni onto NiFeF, the XRD pattern displayed a pronounced peak corresponding to the Ni–Fe alloy (ICSD 98-010-8456). In addition, distinct reflections were assigned to metallic iron and nickel in accordance with ICSD 96-901-4477 and 98-064-6089, respectively (see Figure S2). The (111) diffraction peak exhibited a slight shift within the 2θ range of 43.5° to 44.2°, which can be attributed to changes in the Ni:Fe molar ratio and the resulting lattice distortion. Furthermore, the peak at 50.3° became more prominent in the NiO/NiFeF composite, indicating enhanced crystallinity and possible structural ordering induced by NiO incorporation.

The crystallite size of the samples was estimated using the Debye–Scherrer equation. The pristine NiFeF exhibited an average crystallite size of 8.32 nm, which increased to 11.08 nm in the NiO/NiFeF composite. This increase is attributed to the direct growth of pre-existing crystallites during the NiO deposition process.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were also measured to determine the specific surface area and porosity of the materials. The NiO/NiFeF composite exhibited a BET surface area of 4.7 m2 g−1 and a pore volume of 1.05 cm3 g−1. These values are comparable to those reported for other metallic foams used in catalytic ozonation processes for the degradation of pharmaceuticals (e.g., 1.47 m2 g−1).

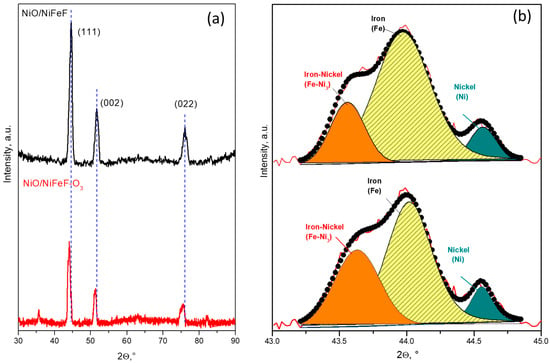

Comparison of the XRD patterns of fresh and NPX-ozonized NiO/NiFeF reveals that the characteristic peaks corresponding to the constituent phases remained largely unchanged, indicating that the crystal structure was mostly preserved during the catalytic ozonation process, as shown in Figure 3. However, a slight shift of approximately 3° toward lower angles was observed after ozonation, as shown in Figure 3a. This shift may be attributed to lattice expansion, possibly caused by the adsorption of NPX molecules, incorporation of oxygen species, or surface interactions during the ozonation process. No new crystalline phases were detected, suggesting that the NiO/NiFeF catalyst maintains its structural integrity under the reaction conditions, as shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

(a) XRD patterns of fresh and NPX-ozonized NiO/NiFeF, highlighting subtle shifts in peak positions after ozonation, and (b) deconvolution of the 2θ region between 43° and 45°.

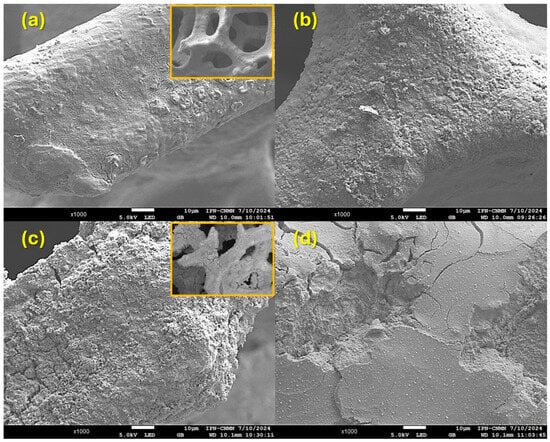

2.3. SEM Analysis

The surface morphology of the materials was analyzed using SEM. As shown in the insert of Figure 4a, the pristine NiFeF exhibits a three-dimensional porous network with an interconnected structure and relatively smooth surfaces. After exposure to ozone (Figure 4b), the NiFeF surface appears rougher, with the presence of small particles and irregular granules.

Figure 4.

SEM images of (a,b) NiFeF and (c,d) NiO/NiFeF (a,c) before and (b,d) after the contact with ozone at 120 min.

Figure 4c shows the morphology of the fresh NiO/NiFeF composite. The deposited NiO is unevenly distributed on the NiFeF substrate, resulting in a visibly rougher surface while retaining the overall porous structure (insert of Figure 4c), but the surface presents a visible coating with characteristic cracks, indicating the formation of NiO on the metallic skeleton. Cracks are also observed across the NiO layer, likely resulting from the deposition and drying processes. These cracks could potentially reduce mechanical stability but may also enhance the transport of reactive species during ozonation. After 120 min of NPX ozonation, Figure 4d shows the used NiO/NiFeF catalyst surface, where some particles and relatively smooth surfaces can be observed. The structure of the coating has changed significantly compared to Figure 4c.

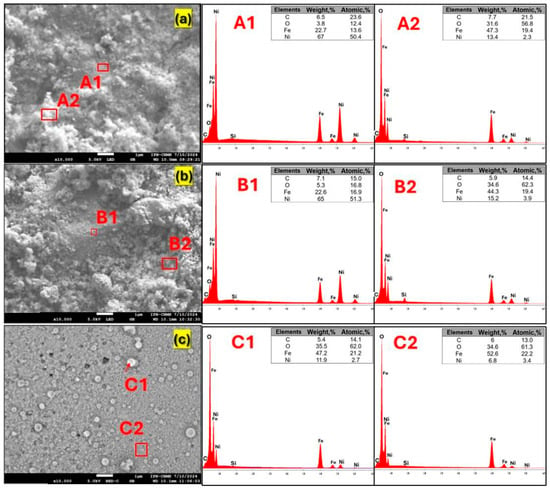

The elemental composition and distribution of Ni, Fe, and O were examined by EDS, as presented in Figure 5a–c. Elemental mapping was performed in two different regions (A1 and A2) of each sample to assess the homogeneity of the surface composition. In pristine NiFeF (Figure 5a), mapping revealed a pronounced variation in Ni content, with 67 wt% in region A1 and 13.4 wt% in region A2, indicating an inhomogeneous surface distribution. This variability likely reflects local compositional or structural features, such as Ni enrichment, porosity, or uneven surface coverage.

Figure 5.

SEM images and EDS analysis of the (a) fresh NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF (b) before and (c) after the contact with ozone.

After NiO deposition (Figure 5b), the surface oxygen content increased noticeably, reaching 34.6 wt% in region A2, consistent with the formation of NiO on the surface. Following the catalytic process (Figure 5c), the Ni content decreased compared with the fresh sample. This behavior suggests that ozone exposure promoted further oxidation of surface Fe, leading to the formation of higher-valence iron oxides and oxygenated surface species, due to the strong oxidizing nature of ozone and the generation of ROS. Nickel leaching was quantified by atomic absorption spectrometry, yielding concentrations below 0.02 mg L−1 after ozonation, confirming negligible Ni release despite the surface heterogeneity. These surface chemical changes are further supported by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis, as discussed in Section 2.4.

2.4. XPS Analysis

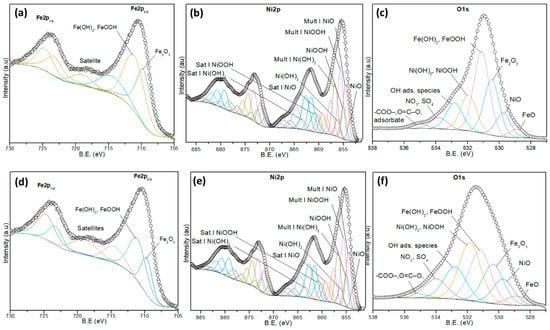

To study the surface chemical composition and the oxidation states of the fresh and used NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF catalysts in NPX ozonation, XPS measurements were performed.

The Fe2p spectra (Figure 6a,d) display characteristics of Fe3+ species, including Fe2O3 (710.7 eV) and hydroxylated forms such as FeOOH and Fe(OH)3 (~712.4 eV), along with their associated satellite peaks (~719 eV). After the ozonation process, an increase in the intensity of the satellite peaks is observed, which may indicate enhanced surface disorder or interaction with some byproducts. The presence of Fe2+ decreased, suggesting that Fe remained predominantly in the +3-oxidation state under both conditions.

Figure 6.

High-resolution XPS spectra of the (a,d) Fe2p, (b,e) Ni2p, and (c,f) O1s of (a–c) fresh and (d–f) used NiFeF catalyst.

The Ni2p spectra (Figure 6b,e) exhibit contributions from NiO (853.7 eV), Ni(OH)2 (855.5 eV), and NiOOH (~856.8 eV), along with multiplet structures and satellite peaks between 860 and 867 eV, as shown in Table S1 [34,35,36]. In the fresh sample, NiOOH is the dominant species, indicating a significant amount of Ni3+. After ozonation, a relative decrease in NiOOH intensity is observed, accompanied by an increase in Ni(OH)2 and NiO signals. These changes suggest a partial reduction of Ni3+ to Ni2+, indicating that nickel may be actively involved in redox processes during ozonation, likely contributing to electron transfer with Fe, as shown in Table S2.

The O1s spectra (Figure 6c,f) reveal peaks corresponding to oxygen in metal oxides/hydroxides (FeOOH, Fe2O3, Ni(OH)2, NiOOH), as well as adsorbed species including hydroxyl groups, carboxylates (-COO−, O=C–O), and oxygenated anions such as NO3− and SO42−, as shown in Table S3 [36,37,38]. These last contributions are inherent impurities from the foam. After the catalytic process, there is a notable increase in the contribution from oxygenated adsorbates, suggesting surface accumulation of byproducts derived from NPX degradation, as shown in Table S4.

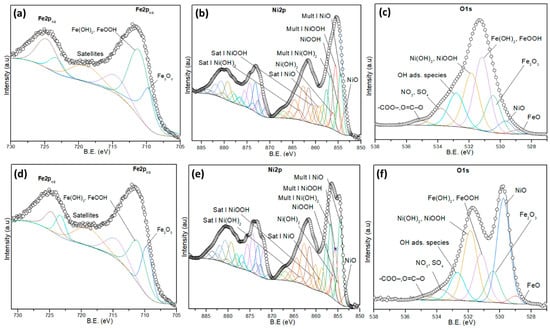

High-resolution spectra were recorded for the Fe2p, Ni2p, and O1s regions of NiO/NiFeF, as shown in Figure 7. The Fe2p spectra shows well-defined signals for Fe3+ species, which are assigned to Fe2O3, and FeOOH/Fe(OH)3. A prominent satellite peak appears around 719 eV, indicative of Fe3+ (Figure 7a,d). After the ozonation reaction, no significant shift in binding energies is observed, and the relative intensities remain stable.

Figure 7.

High-resolution XPS spectra of the (a,d) Fe2p, (b,e) Ni2p, and (c,f) O1s of (a–c) fresh and (d–f) used NiO/NiFeF catalyst.

The Ni2p spectra reveal the presence of Ni2+ and Ni3+ species, including NiO, Ni(OH)2, and NiOOH (Ni3+), along with their multiplet structures and satellite features for each species, Table S5. Figure 7b shows the spectrum of a fresh NiO/NiFeF catalyst, where the dominant species are NiO and NiOOH, suggesting a mixed valence surface, which is favorable for redox reactions. Figure 7e displays the spectrum of NiO/NiFeF after ozonation; a noticeable increase in the NiO signal is observed with a relative decrease in NiOOH, Table S6. This shift indicates a partial reduction of Ni3+ to Ni2+, confirming the active role of nickel in facilitating electron transfer in the oxidative degradation process.

As shown in Figure 7c,f, the O1s spectra show several contributions. The peaks at 528.5–530.2 eV correspond to lattice oxygen in NiO and Fe2O3, while the peaks at 531.2–531.9 eV can be ascribed to hydroxyl species (Ni(OH)2, FeOOH), and the peak at 532.8 eV is attributed to adsorbed OH groups. Additional peaks in the range 532.5–535.2 eV are ascribed to surface-adsorbed oxygenated species, including -COO−, O=C–O−, NO3− and SO42−, Table S7.

After ozonation, the spectrum of the O1s region shows that the intensity of oxygenated species increased significantly (Table S8), suggesting the accumulation of partially intermediates from NPX removal on the catalyst surface, as shown in Figure 8. The species identified by XPS could contribute to ozone decomposition and the formation of various ROS, which are responsible for the high TOC removal observed during NPX ozonation.

Figure 8.

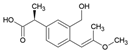

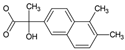

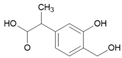

The possible degradation pathway of NP by conventional ozonation.

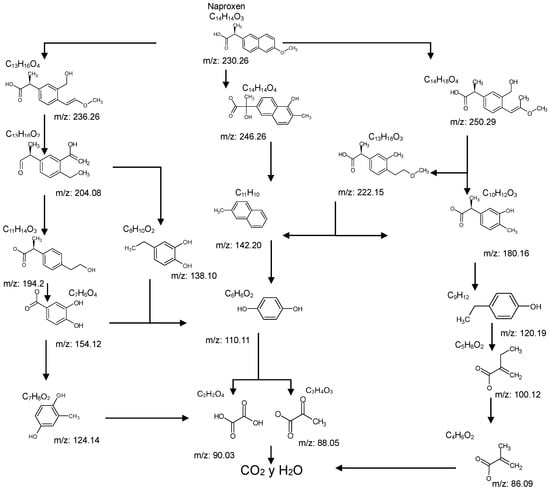

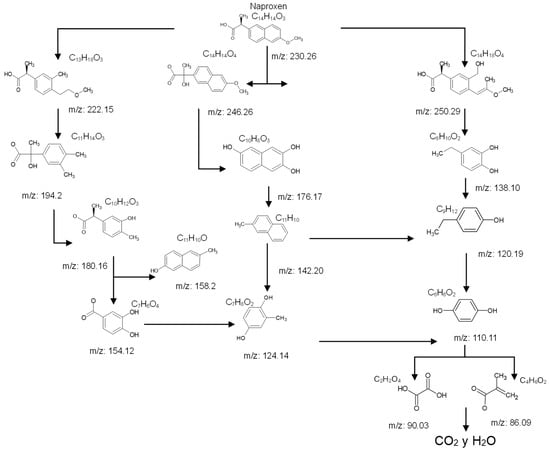

2.5. Catalytic Reaction Pathways

The identified intermediate and final products observed in the three studied processes are presented in Table 1. A comparison of the identified compounds for each process (conventional and catalytic ozonation with NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF) revealed some differences. Overall, catalytic ozonation, regardless of the catalysts used, demonstrated superior efficacy, as evidenced by a lower number of identified byproducts (26 for conventional ozonation versus 20–21 for catalytic ozonation). This reduction correlates with a higher degree of mineralization. Notably, in catalytic processes, complex derivatives of propanoic acid (compounds No. 3–6, 10–14) were not detected.

Table 1.

Identified compounds in conventional and catalytic ozonation.

Table 1 reports the compounds identified during conventional and catalytic ozonation for NPX removal. Some compounds are consistent with those reported in the literature [39,40]; however, the formation of certain intermediates during the catalytic process depends on the type of catalyst used. Therefore, it can be inferred that the degradation pathway of NPX differs between ozonation alone and the catalytic process in the presence of NiO/NiFeF.

The absence of these compounds in catalytic ozonation suggests a more rapid progression toward final degradation products with their partial mineralization. This could result from: (a) the transient nature of intermediates due to increased ROS, or (b) alternative reaction mechanisms in which such intermediates are not formed.

Tables S9–S11 present the compounds identified at specific ozonation times. Based on these data, a possible degradation pathway for NPX under conventional ozonation can be proposed: NPX is eliminated within 15 min via attack on the first aromatic ring, forming 2-(5,6-dimethylnaphthalen-2-yl)-2-hydroxypropanoic acid (C15H16O3), which is subsequently transformed into 6-ethylnaphthalen-2-ol (C12H12O) after 30 min, and further into 2-methylnaphthalene (C11H10) after 60 min. This compound is eventually decomposed into three types of organic intermediates, ultimately yielding CO2 and H2O. However, as shown in Figure 8, other parallel and sequential reactions also occur during NPX elimination under conventional ozonation.

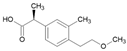

In the case of catalytic ozonation (Figure 9), NPX initially forms more complex compounds (C13–C11), which decompose within 15 min into low-molecular-weight products. It is important to note that not all compounds identified in Table 1 were included in the proposed NPX degradation pathway, illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9. Only the most stable and persistent compounds (those remaining the longest during ozonation) were considered (see Tables S9–S11). These results confirm that catalytic ozonation follows a more efficient degradation pathway, in which recalcitrant intermediates are either short-lived or not formed at all, leading to a faster and more complete mineralization of NPX.

Figure 9.

The possible degradation pathway of NP by catalytic ozonation with NiO/NiFeF-S1.

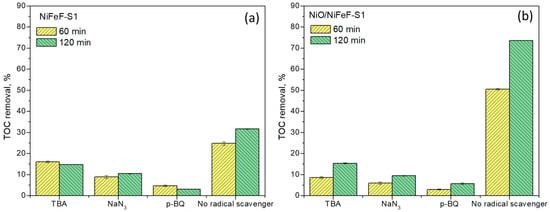

2.6. Identification of ROS Formed in Catalytic Ozonation

Competitive quenching experiments were conducted to identify the ROS responsible for NPX degradation, as shown in Figure 10. Tert-butanol (TBA, 20 mM), p-benzoquinone (p-BQ, 10 mM), and sodium azide (NaN3, 20 mM) were used as scavengers of •OH, •O2−, and 1O2, respectively [41,42].

Figure 10.

Competitive radical quenching in (a) NiFeF-S1 and (b) NiO/NiFeF-S1 during 60 and 120 min of catalytic ozonation. Experimental conditions: [NPX] = 20 mg/L; catalyst size = 1 × 2.5 cm; [O3] = 11 mg/L; flow rate = 5 mL/min; [TBA, NaN3, and p-BQ] = 20 mM.

The addition of TBA suppressed NPX degradation in both NiFeF-S1 and NiO/NiFeF-S1 systems, with TOC removal efficiencies decreasing by 2.1- and 4.8-fold, respectively. This strong inhibition in the NiO/NiFeF-S1 system confirms the key role of •OH in catalytic ozonation, consistent with its much higher reactivity rate constant (2.49 × 1010 M−1 s−1) compared to O3 (4.4 × 103 M−1 s−1) [43]. The suppression of TOC removal efficiency to 53.5% (NiFeF-S1) and 80% (NiO/NiFeF-S1) after 120 min in the presence of TBA, compared with the control systems, provides clear evidence that •OH participated during NPX degradation.

In contrast, p-BQ addition exerted a stronger inhibitory effect, reducing TOC removal by 10.2- and 13.0-fold with NiFeF-S1 and NiO/NiFeF-S1, respectively. The corresponding decline in average TOC removal efficiencies to 90.1% and 92.2% indicates the participation of •O2−, although its reactivity toward most organic compounds is considerably lower (kO3 = 1.50–4.4 × 102 M−1 s−1; k•OH = 9.9 × 108–6.2 × 109 M−1 s−1) [44]. These findings suggest that •O2− was more effectively inhibited in the system but contributed only secondarily to NPX degradation, owing to its comparatively lower reactivity with organic compounds.

NaN3 addition also reduced TOC removal efficiencies by 3.0- and 7.8-fold, indicating the involvement of 1O2. The average TOC removal efficiencies decreased to 90.2% (NiFeF-S1) and 87.2% (NiO/NiFeF-S1) after 120 min. This agrees with previous reports of 1O2 generation during catalytic ozonation [45]. The dual reactivity of NaN3 with both 1O2 and •OH (k•OH = 1.2 × 109 M−1 s−1) [46]. may also partially account for the observed inhibition.

These results demonstrate that hydroxyl radicals are the principal oxidizing species in both catalytic systems, with singlet oxygen playing a significant but secondary role, and superoxide contributing to a minor extent. Scavenger experiments further confirmed that the same primary ROS are operative in both NiFeF-S1 and NiO/NiFeF-S1 systems. The enhanced TOC removal observed with NiO/NiFeF-S1 is attributed to a higher generation of these reactive species, resulting from an increased density of active sites provided by the NiO nanoparticles (e.g., surface hydroxyl groups and Ni2+/Ni3+ redox couples), which promote more efficient ozone decomposition into radicals.

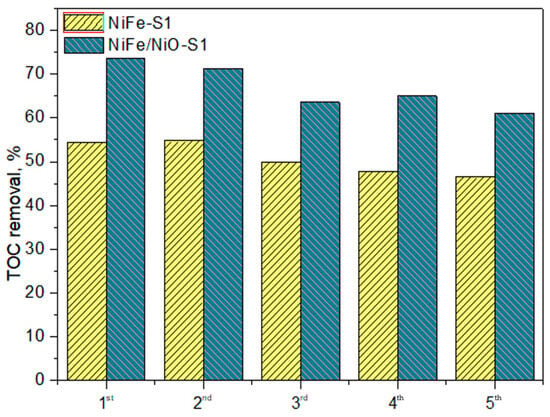

2.7. Catalyst Stability Study

Catalyst stability during NPX ozonation is a critical parameter, evaluated through five consecutive reuse cycles. Figure 11 shows that TOC removal decreased slightly after each run. In the fifth cycle, TOC removal was reduced by only 12.4%. This slight loss of catalytic activity may be due to changes in the oxidation state of the metals in the catalyst (as confirmed by XPS analysis), as well as the partial adsorption of intermediates on the catalyst surface. Therefore, the NiO/NiFeF-S1 catalyst demonstrates good stability and is suitable for long-term use. In the case of NiFeF-S1, it also exhibited high stability, with TOC removal remaining below 10% throughout five successive reuse cycles.

Figure 11.

Reusability experiment of NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF during NPX ozonation.

The activity of other catalysts reported in previous studies for NPX removal using AOPs was compared with that of the present work. As shown in Table 2, the catalytic activity of as-prepared NiO/NiFeF was similar to or even superior to that of these other materials. Therefore, NiO/NiFeF represents a viable alternative for the removal of pharmaceutical compounds via catalytic ozonation.

Table 2.

Comparison of NPX removal using several catalysts in POAs.

3. Experimental Section

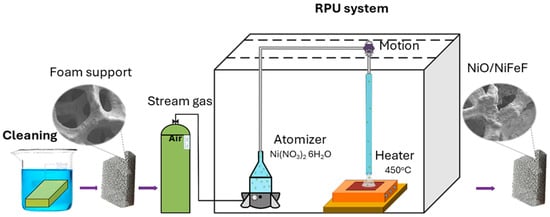

3.1. Preparation of the Catalysts

Prior to use, the NiFeF pieces were sequentially cleaned with HCl solution (1.0 mol L−1), ethanol, acetone, and distilled water. The cleaned NiFeF was subjected to an ultrasonic treatment in aqueous solution for 15 min and dried at 60 °C for 12 h [3].

The NiO deposited on NiFeF (denoted as NiO/NiFeF) was synthesized by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis (USP), as shown in Figure 12. The experimental conditions were as follows: (a) spray nozzle diameter of 1.4 cm, (b) nozzle-to-substrate distance of 3.7 cm, (c) substrate temperature of 450 °C, (d) carrier gas pressure of 20 psia, (e) atomizer frequency of 0.7 MHz, and (f) deposition time of 15 min. The precursor solution consisted of 0.001 mol L−1 nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 97%) dissolved in deionized water.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of the synthesis of NiO/NiFeF catalyst.

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

The crystalline structure of the materials was analyzed by X-ray diffraction, using an XPERT-Pro diffractometer (PANalytical) in Bragg–Brentano configuration and grazing incidence mode, with Cu-kα radiation, scanning speed of 0.5°/minute, 2θ range of 10° to 90°, and step size of 0.02°.

Surface area and pore characteristics were determined via Brunauer–Emmet–Teller (BET) nitrogen adsorption using a Quantachrome NovaWin analyzer (version 11.03). Samples were degassed under vacuum at 110 °C for 48 h prior to measurement.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted using an EDAX-AMETEK Octane-Elect model, set at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV and a window opening distance of 30 mm. A secondary electron detector captured the images, while energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental analysis indicated the predominant presence of Fe, O, and Ni at a working distance of 10 mm (WD).

A comprehensive chemical analysis of commercial metal foam and NiO/NiFeF catalyst compounds was conducted using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). This analysis utilizes a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer, equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). Three randomly located zones of ≥213 μm2 on the surface of each sample were analyzed using a 400 μm spot size and pass energies of 160 and 40 eV, enabling acquisition of both survey and high-resolution spectra.

Before analysis, samples were maintained under high vacuum (≥1 × 10−8 Torr) for up to 12 h in a pre-vacuum chamber directly connected to the equipment and then transferred to the analysis chamber with a base pressure of 1 × 10−10 Torr. A series of surveys and high-resolution spectra were subsequently obtained. Throughout the spectrum acquisition, no artifacts related to peak deformation were observed. To compensate for possible binding energy shifts induced by charge effects, the O1s peak at 529.7 eV (associated with NiO) was used as an internal reference. Finally, analysis and fitting of the high-resolution spectra of NiFeF samples, O1s, and Fe2p were performed using Thermo Scientific AVANTAGE v. 5.99 software, employing pseudo-Voigt type functions (70% Gaussian, 30% Lorenzian) in combination with a Shirley background.

3.3. Ozonation Procedure

Catalytic and conventional ozonation experiments were conducted in a 640 mL glass reactor containing NPX solution (20 mg L−1). Ozone (O3) was generated from extra dry oxygen using a corona discharge type generator (Longevity Resources) and introduced through a ceramic diffuser placed at the bottom of the reactor. The O3/O2 gas flow was 0.5 L min−1, with an ozone concentration of 11 mg L−1. Residual ozone at the reactor outlet was continuously monitored using a BMT 964 BT ozone sensor, which allows real-time measurement of ozone concentration in the gas phase.

3.4. Analytical Methods

The degradation of NPX and formation of intermediates were monitored using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Flexar Series 200, PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) equipped with a diode array detector and a Platinum C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and acidified water (40:60, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min−1. The injection volume was 20 µL.

Identification of intermediates and final products from both conventional and catalytic ozonation was performed using Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry (FTICR-MS) (7T SolariX XR, Bruker Daltonik, Germany). Samples were directly infused into the electrospray ionization source (ESI) using a 250 μL Hamilton syringe at 2 μL/min. ESI parameters included a capillary voltage of 4.5 kV, drying gas temperature of 180 °C, and gas flow rate of 4 L/min. Measurements were conducted in positive ion mode over an m/z range of 43−2000 Da. Isotopic patterns were acquired using quadrupole selection and broadband detection. Data acquisition involved 100 scans, with a total run time of 2 min and a resolving power of 2,000,000 at m/z.

TOC measurements were determined using a GE Sievers InnovOx TOC analyzer with a built-in oxygen generator. Organic matter was oxidized using sodium persulfate and phosphoric acid under supercritical conditions. A calibration curve was established using glucose as the standard, ensuring accurate and reliable TOC quantification in complex aqueous matrices.

Nickel leaching was quantified using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS). Samples collected after 120 min of ozonation were digested in HNO3 under heating with continuous stirring for 1 h. The digested solutions were then filtered through Whatman 541 filter paper, and the resulting filtrates were analyzed with a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 100 spectrometer, equipped with a nickel lamp and operated under an acetylene–oxygen flow of 0.3 L min−1.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of commercial nickel–iron foam (NiFeF) as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for the ozonation of naproxen (NPX). Despite its low specific surface area (4.737 m2/g) and pore volume (1.05 cm3/g), the pristine foam enabled significant NPX mineralization (31.7%) within 120 min of reaction. The catalytic performance was substantially enhanced through surface modification with NiO via USP, achieving a degree of mineralization of 73.7% under the same conditions. Product analysis by FTICR-MS confirmed a notable reduction in both the number and structural complexity of ozonation intermediates during catalytic treatment. Rapid decomposition of aromatic byproducts within 5–15 min supports the involvement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in indirect oxidation mechanisms. Both catalytic systems (NiFeF and NiO/NiFeF) exhibited good stability, sustaining TOC removal efficiency over five consecutive reuse cycles, with the decline in catalytic activity remaining below 10%. Based on the comprehensive identification of intermediates, plausible degradation pathways for NPX were proposed for both conventional and catalytic ozonation processes. The results highlight the potential of Ni-based foams as scalable, low-cost catalytic platforms for advanced oxidation of pharmaceutical pollutants in aqueous environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15100993/s1. Figure S1: XRD pattern of pristine NiFeF and highlighting the main crystalline phases present; Figure S2: XRD pattern of pristine NiO/NiFeF, highlighting the main crystalline phases present; Table S1: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution Ni 2p XPS spectra of NiFeF; Table S2: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution Ni 2p XPS spectra of NiFeF after exposure to ozone; Table S3: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution O1s XPS spectra of NiFeF; Table S4: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution O 1s XPS spectra of NiFeF after exposure to ozone; Table S5: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution Ni 2p XPS spectra of NiO/NiFeF; Table S6: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution Ni 2p XPS spectra of NiO/NiFeF after exposure to ozone; Table S7: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution O1s XPS spectra of NiO/NiFeF; Table S8: Binding energies (BE), full width at half maximum (FWHM), and peak areas obtained from the deconvolution of high-resolution O1s XPS spectra of NiO/NiFeF after exposure to ozone; Table S9: Chemical structures of products obtained in conventional ozonation. Table S10: Chemical structures of products obtained in catalytic ozonation with NiFeF; Table S11: Chemical structures of products obtained in catalytic ozonation with NiO/NiFeF.

Author Contributions

G.L.M.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation. J.L.R.S.: formal analysis, supervision, resources, funding acquisition, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. T.P.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, supervision, resources, funding acquisition, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, Y.C.N.: Data curation, Mass spectroscopy analysis. H.F.M.L.: Investigation. L.L.R.: XPS análisis, data curation. C.J.R.T.: Data curation, Validation. J.J.C.A.: Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Instituto Politécnico Nacional (Projects No. 20253497, No. 20253966, Innovation No. 20250332). Proyecto apoyado por la Secihti en el año 2025 (C-1456).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Centro de Nanociencias y Micro y Nanotecnologías, Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Barrios-Estrada, C.; de Jesús Rostro-Alanis, M.; Muñoz-Gutiérrez, B.D.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Kannan, S.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Emergent contaminants: Endocrine disruptors and their laccase-assisted degradation—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 1516–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, O.Z.; Olawade, D.B. Recent occurrence of pharmaceuticals in freshwater, emerging treatment technologies, and future considerations: A review. Chemosphere 2025, 374, 144153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska-Kaufman, M.; Zembrzuska, J. Application of oxidation processes in wastewater quaternary treatment for organic compounds, antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs removal and disinfection. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 321, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszyńska, D.; Guzik, U. Naproxen in the environment: Its occurrence, toxicity to nontarget organisms and biodegradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Ríos, A.L.; Gutierrez-Suarez, K.; Carmona, Z.; Ramos, C.G.; Silva Oliveira, L.F. Pharmaceuticals as emerging pollutants: Case naproxen an overview. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Su, Q.; Lv, C.; Jin, X.; Wen, X. UV-Induced Photodegradation of Naproxen Using a Nano γ-FeOOH Composite: Degradation Kinetics and Photocatalytic Mechanism. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.K.; Dhakal, D.; Lee, S.W. Rapid degradation of naproxen by AgBr-α-NiMoO4 composite photocatalyst in visible light: Mechanism and pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 347, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arany, E.; Szabó, R.K.; Apáti, L.; Alapi, T.; Ilisz, I.; Mazellier, P.; Dombi, A.; Gajda-Schrantz, K. Degradation of naproxen by UV, VUV photolysis and their combination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 262, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, L. Degradation of naproxen in chlorination and UV/chlorine processes: Kinetics and degradation products. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 34301–34310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, M.; Kıranşan, M.; Karaca, S.; Khataee, A.; Karimi, A. Sonocatalytic removal of naproxen by synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles on montmorillonite. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 31, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulova, N.; Kattel, E.; Trapido, M. Degradation of naproxen by ferrous ion-activated hydrogen peroxide, persulfate and combined hydrogen peroxide/persulfate processes: The effect of citric acid addition. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 318, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, C.M.; Vazquez-Arenas, J.; Castillo-Araiza, O.O.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Chairez, I.; Salinas, E.; Poznyak, T. Improving ozonation to remove carbamazepine through ozone-assisted catalysis using different NiO concentrations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22184–22194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biard, P.-F.; Werghi, B.; Soutrel, I.; Orhand, R.; Couvert, A.; Denicourt-Nowicki, A.; Roucoux, A. Efficient catalytic ozonation by ruthenium nanoparticles supported on SiO2 or TiO2: Towards the use of a non-woven fiber paper as original support. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 289, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhao, H.; Xie, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species and Catalytic Active Sites in Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Water Purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 5931–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wu, C.; Fu, L.; Tian, X.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zuo, J. Development, dilemma and potential strategies for the application of nanocatalysts in wastewater catalytic ozonation: A review. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 330–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Melo, C.M.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Chairez, I.; Salgado, I.; Andraca Adame, J.A.; Galaviz-Pérez, J.A.; Vazquez-Arenas, J.; Poznyak, T. Enhanced Naproxen Elimination in Water by Catalytic Ozonation Based on NiO Films. Catalysts 2020, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Luo, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, L. Catalytic ozonation of organic contaminants in petrochemical wastewater with iron-nickel foam as catalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 211, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Diao, P. Nickel foam supported NiFe2O4-NiO hybrid: A novel 3D porous catalyst for efficient heterogeneous catalytic ozonation of azo dye and nitrobenzene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 541, 148683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalik, W.F.; Ho, L.N.; Ong, S.A.; Wong, Y.S.; Yusoff, N.A.; Lee, S.L. Revealing the influences of functional groups in azo dyes on the degradation efficiency and power output in solar photocatalytic fuel cell. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2020, 18, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ban, X.; Sun, A.; Lai, H.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Pan, P.; He, J.; Zhang, R. A highly sensitive non-enzymatic glucose sensor based on coral-like Cu/nickel foam bimetallic structure. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, H.; Ma, J.; Imanova, G.; Komarneni, S. Cu2S/Ni3S2 nanosheets combined with nickel foam substrate for efficient catalytic ozonation of p-nitrophenol in wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ran, T.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, F.; Yang, G.; Zhou, Y. Surface Hydrogen Atoms Promote Oxygen Activation for Solar Light-Driven NO Oxidization over Monolithic α-Ni(OH)2/Ni Foam. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 16221–16230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Qiu, S.; Diao, P. Copper Foam-Supported CuxO@Fe2O3 Core–Shell Nanotubes: An Efficient Ozonation Catalyst for Degradation of Organic Pollutants. ACS EST Water 2023, 3, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, F.; Cheng, H.; Komarneni, S.; Ma, J. In-situ growth of Ni3S2@Mo2S3 catalyst on Mo-Ni foam for degradation of p-nitrophenol with a good synergetic effect by using ozone. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Hu, X.; Lou, Z.; Zhu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Tian, S. In-situ growth of defect-enriched NiO film on nickel foam (NF@NiO) monolithic catalysts for ozonation of gaseous toluene. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 893, 162160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, L.; Li, G.; Liu, H.; Liang, Z.; Zhao, H.; An, T. Enhanced catalytic ozonation inactivation of bioaerosols by MnO2/Ni foam with abundant oxygen vacancies and O3 at atmospheric concentration. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 344, 123675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Cheng, H.; Komarneni, S.; Ma, J. Enhanced heterogeneous catalytic ozonation to degrade p-nitrophenol by Co-doped Ni3S2/NF nanosheets. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 689, 133717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Yang, T.; Liu, D.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, C.; Hu, J.; Huang, H. Preparation of LMO@FC catalysts and degradation of tetracycline by catalytic ozonation. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1004, 175848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhan, S.; Lou, Z.; Zhu, J.; Feng, J.; Xiong, Y. Electrodeposition synthesis of 3D-NiO1−δ flowers grown on Ni foam monolithic catalysts for efficient catalytic ozonation of VOCs. J. Catal. 2021, 398, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Wang, P.; Shi, F.; Xu, P.; Zhang, G. Metal foam-based functional materials application in advanced oxidation and reduction processes for water remediation: Design, Mechanisms, and Prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.A.-O.; Valenzuela, M.A. Ni-based catalysts used in heterogeneous catalytic ozonation for organic pollutant degradation: A minireview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 84056–84075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubóová, A.; Oriňaková, R.; Strečková, M.; Paračková, M.; Petruš, O.; Plešingerová, B.; Mičušík, M. Iron-nickel metal foams modified by phosphides as robust catalysts for a hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 34, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Maiyalagan, T.; Panomsuwan, G.; Jiang, Z.; Rahaman, M. Iron-Doped Nickel Hydroxide Nanosheets as Efficient Electrocatalysts in Electrochemical Water Splitting. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, C.; Toldra-Reig, F.; Balaguer, M.; Somacescu, S.; Garcia-Fayos, J.; Palafox, E.; Serra, J.M. Mixed Ionic–Electronic Conduction in NiFe2O4–Ce0.8Gd0.2O2−δ Nanocomposite Thin Films for Oxygen Separation. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 2638–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Payne, B.P.; Grosvenor, A.P.; Lau, L.W.; Gerson, A.R.; Smart, R.S.C. Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, R.; Zhou, W. A Wire-Shaped Supercapacitor in Micrometer Size Based on Fe3O4 Nanosheet Arrays on Fe Wire. Nano-Micro Lett. 2017, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullet, M.; Khare, V.; Ruby, C. XPS study of Fe(II)—Fe(III) (oxy)hydroxycarbonate green rust compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 2008, 40, 125–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Lin, K.; Yang, B.; Yang, M.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Gan, J. Biodegradation of naproxen by freshwater algae Cymbella sp. and Scenedesmus quadricauda and the comparative toxicity. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 238, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourakbar, M.; Ghanbari, F.; Khavar, A.H.C.; Khashij, M.; Mehralian, M.; Behnami, A.; Satari, M.; Mahdaviapour, M.; Oghazyan, A.; Aghayani, E. Comparative study of naproxen degradation via integrated UV/O3/PMS process: Degradation products, reaction pathways, and toxicity assessment. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 2725–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; AlNashef, I.M. Superoxide Ion: Generation and Chemical Implications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3029–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y. Revisiting the role of reactive oxygen species for pollutant abatement during catalytic ozonation: The probe approach versus the scavenger approach. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 280, 119418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathon, B.; Coquery, M.; Liu, Z.; Penru, Y.; Guillon, A.; Esperanza, M.; Miège, C.; Choubert, J.M. Ozonation of 47 organic micropollutants in secondary treated municipal effluents: Direct and indirect kinetic reaction rates and modelling. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kovalova, L.; McArdell, C.S.; von Gunten, U. Prediction of micropollutant elimination during ozonation of a hospital wastewater effluent. Water Res. 2014, 64, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Sun, H.; Xiao, J.; Cao, H.; Wang, S. Efficient Catalytic Ozonation over Reduced Graphene Oxide for p-Hydroxylbenzoic Acid (PHBA) Destruction: Active Site and Mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 9710–9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jary, W.G.; Ganglberger, T.; Pöchlauer, P.; Falk, H. Generation of Singlet Oxygen from Ozone Catalysed by Phosphinoferrocenes. Monatshefte Für Chem./Chem. Mon. 2005, 136, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Sun, D. Degradation characteristics of refractory organic matter in naproxen pharmaceutical secondary effluent using vacuum ultraviolet–ozone treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaccallo-Aguilar, Y.; Álvarez-Torrellas, S.; Gil, M.V.; Larriba, M.; García, J. Insights of emerging contaminants removal in real water matrices by CWPO using a magnetic catalyst. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, R.T.; Ashraf, G.A.; Fadhali, M.M.; Al-Sulaimi, S.; Ghernaout, D.; El Jery, A.; Aldrdery, M.; Elkhaleefa, A.; Hassan, N.; Ajmal, Z.; et al. Peroxymonosulfate-based photodegradation of naproxen by stimulating (Mo, V, and Zr)-carbide nanoparticles. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 54, 104027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhi, J.; Li, H.; Jia, Y.; Gao, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. Peroxymonosulfate activation by magnetic NiCo layered double hydroxides for naproxen degradation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 642, 128696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liang, Y. Theoretical evidence of enhanced interaction between H2O and O3 leads to improved performance of catalytic ozonation with copper doping α-FeOOH. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 44, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheydaei, M.; Haseli, A.; Ayoubi-Feiz, B.; Vatanpour, V. MoS2/N-TiO2/Ti mesh plate for visible-light photocatalytic ozonation of naproxen and industrial wastewater: Comparative studies and artificial neural network modeling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 22454–22468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).