Abstract

Medicinal and culinary plants are identified as natural sources of antioxidants, bioactive molecules, and enzyme inhibitors, which are widely used for their nutritional and medicinal virtues. In attempts to identify natural extracts and molecules for overcoming obesity and acne issues, plant extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), sage (Salvia officinalis), and ginger (Zingiber officinale) were prepared using solvents of different polarities. On the other hand, piperine was extracted from Piper nigrum with an extraction yield of 3.25 ± 0.12%. The piperic acid was obtained after the alkaline hydrolysis of piperine with a conversion rate of 97.2%. The ethanolic extract of ginger presented the highest radical scavenging activity with an IC50 = 17.3 ± 1.42 μg/mL, followed by the ethyl acetate extract of sage (IC50 = 20.16 ± 0.57 μg/mL). However, the ethyl acetate extract of ginger (IC50 = 27.87 μg/mL) presented the highest antioxidant activity with the β-Carotene-linoleic acid assay. Furthermore, only the ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of sage, piperine, and piperic acid presented antibacterial activity against the B. subtilis strain. Using inhibition method A, 1 mg/mL ethyl acetate or ethanol extract of sage inhibited 94% or 79% of the chicken pancreatic lipase (CPL) activity, respectively. However, only 500 µg/mL of the same extracts or pure piperic acid completely inhibited the Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL). Indeed, an IC50 of 54 ± 0.48 µg/mL and 68 ± 0.67 µg/mL were obtained with piperic acid and the sage ethyl acetate extract, respectively. Moreover, complete inhibition of SXL was obtained with piperic acid or ethanol extract of ginger, using inhibition method C, confirming the slight hydrophobic character of the inhibitors. Our results suggest that piperic acid and the studied ethanol/ethyl acetate extracts could play an important role as potent anti-obesity and anti-acne agents.

1. Introduction

Obesity and acne threaten human health and beauty. Obesity is one of the most common complex disorders, affecting approximately 650 million adults worldwide [1]. Furthermore, due to similarities in metabolic alterations and risk factors, obesity is associated with other metabolic diseases, including hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and cancer [2,3].

In humans, pancreatic lipase is the enzyme responsible for the hydrolytic process of dietary triacylglycerol in the gastrointestinal tract. Triacylglycerol lipase converts dietary triacylglycerol to diacylglycerol and monoacylglycerol, releasing free fatty acids. The production of fecal lipids and pancreatic lipase inhibition are highly interconnected [4].

Acne is the most common human skin disorder, affecting 80% of the population at least once during life. It results from abnormal hyperkeratinization and inflammation. The sebaceous glands are the most relevant cells in the pathophysiology of acne. Insufficient removal of sebum from the skin leads to the growth of microorganisms such as Propionibacterium acnes [5] and Staphylococcus aureus [6]. Lipases from P. acnes [7] and S. aureus [8] have been recognized as one of the virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of acne. These lipases are the main responsible enzymes for the hydrolysis of sebum triglycerides, thus releasing glycerol and free fatty acids. Glycerol is a source of nutrients for bacteria, whereas fatty acids are highly inflammatory, chemotactic, and irritating for the sebaceous follicle cells.

Moreover, liberated fatty acids increase the adhesion between bacterial and follicle cells, which favors bacterial colonization and biofilm formation. Staphylococcus aureus has also been proven to affect skin rash in acne patients [6]. The boundless and long-term use of antibiotics in treating acne has resulted in the spread of resistant bacterial strains and treatment failure [9,10].

Numerous lipase inhibitors on the market manage and reduce obesity problems by regulating the calorie intake from dietary fat. Both Orlistat and DAC-59 are commercial reversible lipase inhibitors. Several studies have shown that the therapy with these drugs was effective, leading to a 5–10% decrease in body weight in a 4–8-month period compared to diet and exercise [11,12]. In contrast to their effect on obesity, the acting lipase inhibitors are unsuitable for treating acne vulgaris [13,14,15].

Furthermore, it has been shown that tetrahydrolipstatin (THL), the active ingredient of Orlisat, has side effects on human health. Indeed, Orlistat reduces the absorption of beta-carotene and vitamin E by 30% and 60%, respectively. It could have the same effects on other fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamins A, D, and K. Moreover, some patients may develop high levels of oxalates in their urine [16]. In addition, Orlistat has been suspected of increasing the risk of liver damage [17].

Since the beginning of civilization, humans have used aromatic and medicinal plants in the history of medicine (in Greece, the Carthaginian Empire, and the Arab Empire). They have been used in all cultures for their medicinal properties [18].

Therefore, herbs and spices are identified as natural sources of phytochemicals (e.g., polyphenols, flavonoids, vitamins, and other active compounds), well known for their biological activities, such as antioxidant, antitumor, antifungal, and antibacterial activities [19,20,21]. These plant secondary metabolites can be extracted by green solvents like water, ethanol, or their binary mixtures [22]. However, due to the variable compositions of phytochemicals and bioactive compounds, it is difficult to predict the optimal conditions for extracting individual plant materials [23]. Consequently, several solvents have been used to extract phytochemicals and bioactive compounds from plants.

Furthermore, medicinal plants are considered as an interesting source of active compounds that moderate enzymatic activities. Camellia sinensis and Morus australis polyphenols inhibit certain digestive enzymes such as amylase, glucosidase, pepsin, trypsin, and lipase [24,25,26]. Other plants, including Myristica fragrans, are reported to have lipase-inhibitory activity [27]. These natural lipase inhibitors include polyphenols, terpenes, flavonoids, catechin, and quercetin [23]. Some polyphenols extracted from tea, such as epigallocatechin 3,5-di-O-gallate, or grape seeds such as procyanidins are known for their remarkable anti-lipase activity [28].

Therefore, inhibitors that decrease the activities of relevant lipases are potential anti-obesity and anti-acne drugs [11,13,14,15,29,30]. In this context, medicinal and culinary plants native to the Mediterranean region (thyme and sage), as well as some of the most ancient South Asian spices (ginger root and black pepper), used as folk medicine, were investigated for their antioxidant and antibacterial activities, and their inhibitory effect on lipases. The present study sheds light on the importance of different solvents for the extraction of the major compounds from the ginger rhizomes (Zingiber officinale) and the leaves of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) and sage (Salvia officinalis). The antioxidant and antibacterial activities of the different plant extracts and the purified piperine and piperic acid from black pepper (Piper nigrum) were studied. Their inhibitory effect on pancreatic and bacterial lipases was evaluated for the first time.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of the Studied Plants

The plant extracts, namely thyme, sage, and ginger, were prepared using solvents of different polarities: water, ethanol, and ethyl acetate. These solvents are known for extracting most bioactive molecules, such as phenolic compounds and flavonoids [22,23].

The results presented in Table 1 show that the extraction yields varied depending on the polarity of the solvent used.

Table 1.

Extraction yield, total phenolic content, and total flavonoid content of various plant extracts.

From this table, we can note that the extraction yields with water and ethanol resulted in the highest amount of total extractable compounds, confirming that the polarity of the solvents affects the extraction yield and the nature of the extracted molecules [22,23,31].

The results in Table 1 also show that the total phenolic and flavonoid contents depend on the plant and the extraction solvent.

Our results show that the highest phenolic compounds were found in the ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts. Total phenolics of 65.93 ± 0.48, 96.36 ± 7.53, and 122.65 ± 9.53 mg gallic acid equivalent/g were obtained in the T. vulgaris ethyl acetate extract, Z. officinale ethyl acetate extract, and S. officinalis ethanol extract, respectively. This result agrees with that previously obtained by Han et al. (2008), who reported that ethanol was a suitable solvent for extracting phenolic compounds [32].

Quantitative determination of total flavonoids by the aluminum trichloride method revealed that the content of flavonoids in Z. officinale increased with a decrease in the polarity of the solvent used. However, the highest flavonoid contents in S. officinalis (43.64 ± 1.91 mg quercetin/g of total extract) and T. vulgaris (12.3 ± 0.13 mg quercetin/g of total extract) were obtained in water and ethanol extracts, respectively.

The difference in the molecule polarities in the different plants could explain the observed variations in the phenolic and flavonoid contents.

Similar results concerning the low total phenolic contents in Thymus vulgaris water extract (2.13 ± 0.11 gallic acid equivalent/g of fresh weight) and Salvia officinalis water extract (1.34 ± 0.09 gallic acid equivalent/g of fresh weight) were previously obtained [33].

2.2. Purification of Piperine and Piperic Acid

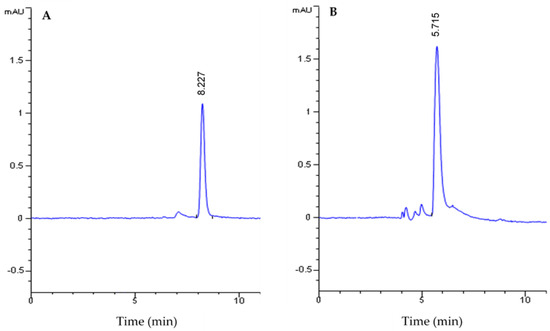

The extraction of piperine from black pepper (P. nigrum) was carried out according to the method described by Han et al. (2008). An extraction yield of 3.25 ± 0.12% was obtained using ethanol as the extraction solvent. A yield of 3.78% was previously obtained when using the same extraction method [32]. HPLC was used to confirm the purity of the extracted piperine. A single peak corresponding to piperine was eluted at the same retention time (8.227 min) as the commercial piperine used as standard (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis of piperine (A) and piperic acid (B).

After the alkaline hydrolysis of the extracted piperine, the yellow precipitate of piperic acid obtained was filtrated and analyzed by HPLC. Our results show the presence of a single peak corresponding to the elution of piperic acid at a retention time of 5.715 min (Figure 1B). The analysis of the chromatogram peak areas shows that the piperic acid was obtained with a conversion rate of 97.2%.

2.3. Antioxidant Activity

This study performed DPPH radical scavenging assays, β-carotene-linoleic acid assays, and DNA nicking assays to evaluate the antioxidant power of the various plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid.

2.3.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

DPPH is a free radical compound commonly used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of plant extracts or other biological substrates.

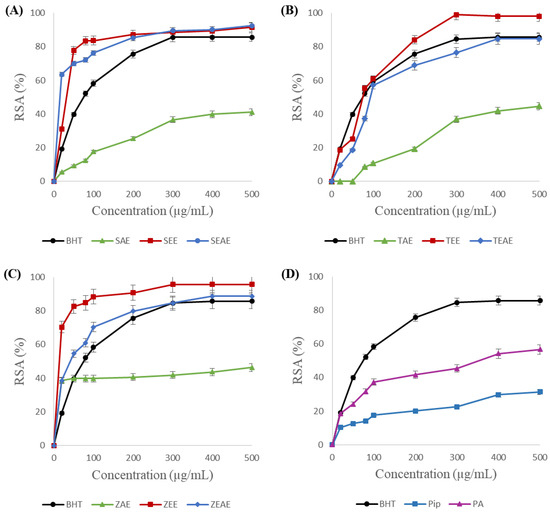

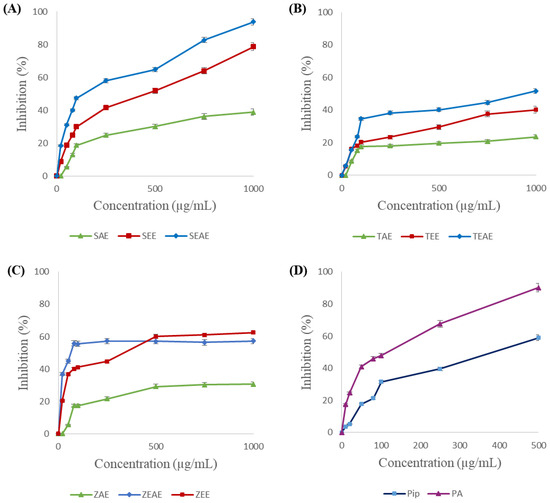

As shown in Figure 2, the radical scavenging activity of the studied plant extracts and the purified molecules is directly proportional to the concentration. The highest scavenging activities were obtained with the studied plants’ ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts. The results show that ethanol extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis) (Figure 2A), thyme (Thymus vulgaris) (Figure 2B), and ginger (Zingiber officinale) (Figure 2C) exhibited scavenging activities of 92 ± 0.053%, 98 ± 0.162%, and 95 ± 0.245% µg/mL, respectively. These activities are higher than the radical scavenging activity of BHT (84%), which is used as a standard antioxidant. The results in Figure 2 also show that the aqueous extracts of the three plants have the weakest antiradical activities. A radical scavenging activity of 55% was observed for piperic acid (Figure 2D). This activity is twice as great as the one for piperine (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

DPPH free radical scavenging activities (RSAs) of different extracts and purified molecules. (A) SAE, SEE, and SEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis), respectively. (B) TAE, TEE, and TEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), respectively. (C) ZAE, ZEE, and ZEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale), respectively. (D) Pip: piperine; PA: piperic acid. BHT: positive control. Data are presented as the mean of three experiments ± SD.

IC50 (concentration of extract that reduces 50% of the DPPH radical) determination proved that the ethanolic extract of ginger (Zingiber officinale) presented the highest radical scavenging activity with an IC50 = 17.3 ± 1.42 μg/mL, followed by the ethyl acetate extract of sage (IC50 = 20.16 ± 0.57 μg/mL). These values are significantly lower than the one for BHT (IC50 = 75.98 ± 0.03 μg/mL).

These results are comparable with those obtained by Stoilova et al. (2007), who showed that the ethanolic extract of ginger has an antiradical activity of 90.1% [34]. Furthermore, Grzegorczyk et al. (2007) found that the methanolic extract of sage presents a strong radical scavenging activity with an IC50 = 20.4 μg/mL [35].

2.3.2. Β-Carotene-Linoleic Acid Assay

The oxidation of linoleic acid generates free radicals, which attack the molecules of β-carotene and cause their oxidation and loss of color. This loss of color can be measured by spectrophotometry.

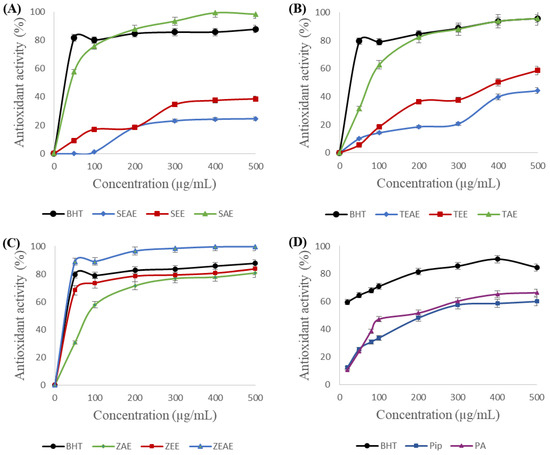

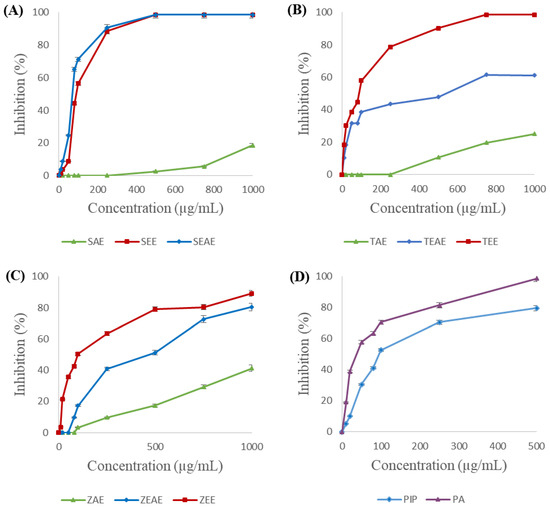

The results of the β-carotene-linoleic acid emulsion assays of the different plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant activity of different extracts and purified molecules using the β-carotene-linoleic acid assay. (A) SAE, SEE, and SEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis), respectively. (B) TAE, TEE, and TEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), respectively. (C) ZAE, ZEE, and ZEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale), respectively. (D) Pip: piperine; PA: piperic acid. BHT: positive control. Data are expressed as the mean of three experiments ± SD.

Our results show that adding various extracts of sage, thyme, and ginger to the linoleic acid-β-carotene emulsion prevents the bleaching of the latter, which testifies to the richness of these extracts in antioxidants. One can note from Figure 3 that, in almost all cases, the antioxidant activity of the plant extracts increases rapidly at low concentrations before becoming constant for higher concentrations. Strong antioxidant activities of 95% and 99% were noted for the aqueous extracts of sage (Figure 3A) and thyme (Figure 3B), respectively. However, these two plants’ ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts have the weakest antiradical activities. In contrast, a 99% antioxidant activity was obtained with the ethyl acetate extract of ginger. One can conclude that the polar molecules in sage and thyme could be responsible for the protection of β-carotene against oxidation, whereas the more hydrophobic molecules from ginger are responsible for its antioxidant activity when using the β-carotene-linoleic acid essay.

Similarly, piperine and piperic acid showed significant antioxidant activities of 58% and 64%, respectively.

The IC50 determination showed that the ethyl acetate extract of ginger (IC50 = 27.87 μg/mL) presented the highest antioxidant activity compared with the other extracts, followed by the ethanol extract of ginger (IC50 = 38.2 μg/mL). A comparable IC50 of 29.58 μg/mL was obtained with BHT.

Free radicals generated following linoleic acid oxidation are responsible for the bleaching of β-carotene. Molecules from the studied plant extracts could, therefore, be used as antioxidants, preventing the oxidation of linoleic acid, and as scavengers of free radicals generated following oxidation [36].

2.3.3. DNA Nicking Assay

DNA oxidation is a severe problem in living organisms. The hydroxyl radical is the main reactive oxygen species contributing to the oxidation of cellular DNA. This radical is produced in vivo by Fenton-type reactions induced by transition metals [37,38].

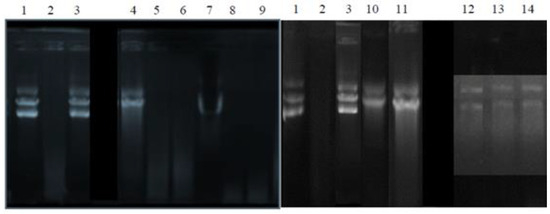

The capacity of the various extracts and purified molecules to inhibit the cutting of plasmid DNA (pCR™ II TOPO, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was evaluated by observing the plasmid’s migration products on agarose gel (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The ability of the extracts and molecules tested to inhibit DNA oxidation and its degradation under the action of hydroxyl radicals. Well 1: native plasmid. Well 2: DNA+ Fenton’s Reagent (negative control). Well 3: DNA + Fenton’s reagent + quercetin (positive control). Wells 4, 5, and 6: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis), respectively. Wells 7, 8, and 9: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale), respectively. Well 10: piperine. Well 11: piperic acid. Wells 12, 13, and 14: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), respectively.

The results illustrated in Figure 4 show that the hydroxyl radicals generated by the Fenton reaction completely degraded the plasmid DNA (well 2), which was initially in its three forms: circular, coiled, and supercoiled (well 1). Pre-incubation of the plasmid with quercetin (well 3), used as a positive control, prevented it from oxidizing. In addition, only the sage aqueous extract (well 4), piperine (well 10), piperic acid (well 11), and thyme extracts (wells 12, 13, and 14) helped in the protection of the plasmid DNA against its degradation. This protection is partial, and it only affected the circular coiled and supercoiled forms.

Therefore, the ability of the different active extracts, piperine, and piperic acid to protect plasmid DNA against oxidation can be explained by their richness in antioxidant molecules capable of scavenging hydroxyl radicals [39] or inhibiting their formation by the chelation of iron ions [40].

2.4. Antibacterial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of the various extracts of sage, thyme, ginger, piperine, and piperic acid was studied according to the method of diffusion in agar [41] using seven pathogenic strains responsible for several severe infections. Ampicillin and streptomycin were used as positive controls at 20 μg per well. The antibacterial activity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zone. The results are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of the different studied plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid.

Our results proved that the tested strains are sensitive to the various extracts of sage, thyme, ginger, piperine, and piperic acid. The aqueous extracts of the three studied plants have been determined to be inactive. The best antibacterial activity was obtained with the ethyl acetate extract of thyme against Salmonella sp. (inhibition diameter of 20.7 ± 3.8 mm). Furthermore, Al Bayati (2008) showed that Gram-negative strains (including Salmonella) are more susceptible than Gram-positive strains with methanol extract and essential oil of Thymus vulgaris [42]. Piperine and piperic acid were active against all the studied bacterial strains with comparable antibacterial activities. Interestingly, inhibition diameters of 16.7 ± 1.6 mm and 9.7 ± 1.0 mm were observed for Salmonella sp. using piperic acid and piperine, respectively. Furthermore, only ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of sage, piperine, and piperic acid presented antibacterial activity against the B. subtilis strain (Table 2), which is known as pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant bacteria [43].

2.5. Lipase Inhibitory Activity Analysis

Several studies have been conducted on plant extracts’ ability to inhibit digestive and bacterial lipase activities [44]. Inhibition of the activity of digestive lipases is directly linked to treating obesity [11]. The inhibition of the microbial lipases involved in specific dermatoses could be an alternative for treating these diseases. In this study, the pancreatic and microbial lipases taken as models are chicken pancreatic lipase (CPL) and Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) [45,46]. The ability of different plant extracts and purified molecules to inhibit lipases was evaluated using the three inhibition methods, namely method A, method B, and method C.

2.5.1. Lipase Inhibitory Effect Using Method A

This method experimented with feasible reactions between the lipase and the inhibitor in an aqueous medium without substrate. The pre-incubation of lipase with the different studied plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid at different concentrations was studied in the absence of bile salts at 25 °C and pH 8 for 10 min. Residual activity was then measured under standard conditions for each enzyme, using an olive oil emulsion as a substrate.

The inhibitory effects of extracts and purified molecules on CPL hydrolytic activity are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of chicken pancreatic lipase (CPL) using method A. (A) SAE, SEE, and SEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis), respectively. (B) TAE, TEE, and TEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), respectively. (C) ZAE, ZEE, and ZEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale), respectively. (D) Pip: piperine; PA: piperic acid. Data are expressed as the mean of three experiments ± SD.

The results proved that inhibition of CPL activity depends on the plant, the extraction solvent, and the concentration of the extract used. Indeed, at 1 mg/mL concentration, the ethyl acetate and ethanol extracts of sage inhibited 94% and 79% of the CPL activity, respectively (Figure 5A). A 65% inhibition was obtained with 1 mg/mL of the ethanol extract of ginger (Figure 5C). Interestingly, piperic acid, with a concentration of 500 μg/mL, inhibited 92% of the CPL activity, against 56% for piperine (Figure 5D). One can also note from Figure 5 that the aqueous extracts presented the lowest inhibitory effects against CPL activity. Inhibitions of 35%, 30%, and 20% were obtained with the aqueous extracts of sage, ginger, and thyme.

On the other hand, complete inhibition of the SXL was obtained with 500 µg/mL of the ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Figure 6A) or 750 µg/mL of the ethanol extract of thyme (Figure 6B). In the same way, piperic acid was found to completely inhibit SXL at a concentration of 500 μg/mL, against 79% inhibition for piperine (Figure 6D). In contrast, the aqueous extracts of sage, thyme, and ginger showed the lowest inhibitory activities (16%, 27%, and 42%, respectively). These results suggest that the inhibitory molecules found in the three plant extracts are hydrophobic.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) using method A. (A) SAE, SEE, and SEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis), respectively. (B) TAE, TEE, and TEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), respectively. (C) ZAE, ZEE, and ZEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale), respectively. (D) Pip: piperine; PA: piperic acid. Data are expressed as the mean of three experiments ± SD.

Furthermore, Table 3 gives the effective inhibition concentrations (IC50) of various plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid on CPL and SXL using method A.

Table 3.

Effective inhibition concentration (IC50) of plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid on CPL and SXL using method A.

As shown in Table 3, for CPL, an IC50 of 75 ± 0.85 µg/mL and 134.6 ± 0.87 µg/mL were obtained with the ginger and sage ethyl acetate extracts, respectively. An IC50 of 88.9 ± 0.42 µg/mL was obtained for the same enzyme with piperic acid.

Concerning SXL inhibition, an IC50 of 54 ± 0.48 µg/mL and 68 ± 0.67 µg/mL was obtained with piperic acid and sage ethyl acetate extract, respectively. Comparable results were obtained with sage and thyme ethanol extracts, with an IC50 of 89 ± 1.19 µg/mL and 80.7 ± 1.34 µg/mL, respectively.

These results confirm the hydrophobic character of the bioactive molecules in the different extracts that could interact with specific lipase residues. These interactions could affect the C-terminal colipase-binding domain or the N-terminal catalytic domain of the CPL. In addition, they could interact with and modify the SXL structure, thus affecting the maintenance of its active form. Several studies have reported the inhibitory effects of ethanolic and methanolic extracts of pomegranate and grape seed on porcine pancreatic and lipoprotein lipases [47,48].

2.5.2. Lipase Inhibitory Effect Using Method B

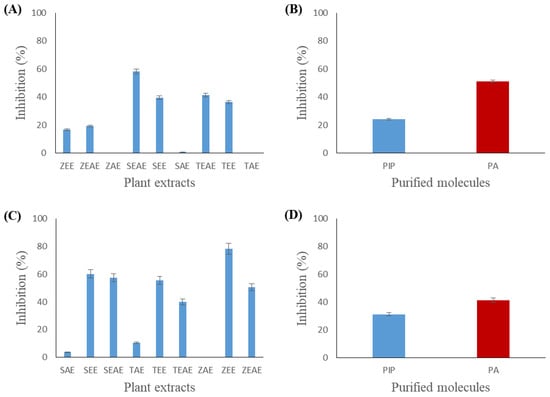

Enzyme inhibition during hydrolysis was performed for different plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid concentrations, with a final sample concentration in the reaction medium equal to 1 mg/mL. The obtained results are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of chicken pancreatic lipase (CPL) and Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) using method B. (A) Inhibition of CPL by different plant extracts. (B) Inhibition of CPL by piperine and piperic acid. (C) Inhibition of Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) by different plant extracts. (D) Inhibition of Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) by piperine and piperic acid. SAE, SEE, and SEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis), respectively. TAE, TEE, and TEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), respectively. ZAE, ZEE, and ZEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale), respectively. Pip: piperine. PA: piperic acid. Data presented as the mean of three experiments ± SD.

Figure 7A shows that 57% inhibition of CPL activity was observed with the ethyl acetate extract of sage. A comparable CPL inhibitory effect was obtained with the ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (18% and 20%, respectively) and thyme (38% and 41%, respectively). Figure 7B highlights that piperic acid had a more significant inhibitory effect (50%) than piperine (24%) for the CPL.

On the other hand, a more significant inhibitory effect was observed with the SXL. The results in Figure 7C show that ethanol extracts of sage, thyme, and ginger presented the highest inhibition values (61%, 58%, and 79%, respectively). The different ethyl acetate extracts have shown lower inhibitory activities. Figure 7D shows that piperic acid has a slightly higher inhibitory activity (42%) than piperine (30%) for the SXL.

Therefore, the observed inhibitory effect could be explained either by a direct action on the adsorbed enzyme (open form) or by adsorption and modification of the interface, thereby affecting the enzyme’s binding step to the lipid/water interface.

2.5.3. Lipase Inhibitory Effect Using Method C

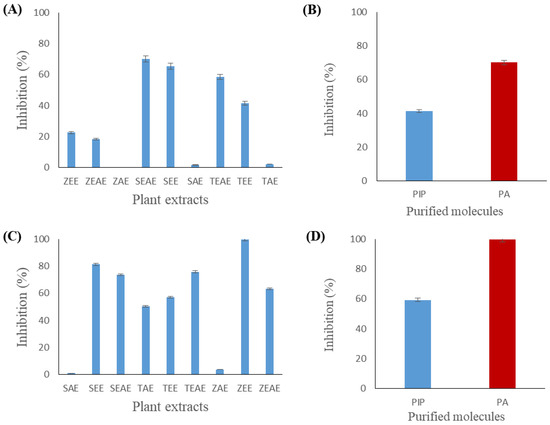

The study of the inhibition of lipases by the “poisoned substrate” method was carried out. In this method, the inhibitor (plant extract or pure molecule) is injected into the reaction medium before adding the enzyme. The obtained results are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of chicken pancreatic lipase (CPL) and Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) using method C. (A) Inhibition of CPL by different plant extracts. (B) Inhibition of CPL by piperine and piperic acid. (C) Inhibition of Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) by different plant extracts. (D) Inhibition of Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) by piperine and piperic acid. SAE, SEE, and SEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of sage (Salvia officinalis), respectively. TAE, TEE, and TEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme (Thymus vulgaris), respectively. ZAE, ZEE, and ZEAE: aqueous, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale), respectively. Pip: piperine. PA: piperic acid. Data presented as the mean of three experiments ± SD.

Figure 8 shows that the CPL inhibition profile of method C is comparable to that observed using method B (Figure 7). A 70% or 65% inhibition was observed using the ethyl acetate or ethanol extract of sage, respectively (Figure 8A). Figure 8B shows that piperic acid had higher inhibitory activity (69%) against CPL than piperine (40%).

Figure 8D shows that piperic acid completely inhibited SXL by method C. Similarly, total inhibition of the enzyme was observed with the ethanol extract of ginger (Figure 8C). Furthermore, ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of sage and ethyl acetate extracts of thyme and ginger showed important inhibitory activities against SXL (80%, 72%, 75%, and 63%, respectively).

The inhibition of lipases by method C depends on the physico-chemical properties of the inhibitor. Indeed, the inhibitor can remain in the aqueous phase or adsorb at the interface. The first case amounts to inhibition by method A (as previously described). In the second case, the hydrophobic inhibitor could interact with the hydrophobic residues around the active site, blocking, therefore, the access of the substrate to the catalytic serine or by a change in the quality of the interface, which would affect the enzyme’s adsorption step at the lipid/water interface.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical Reagents and Standards

Piperine (98% purity) is from Acros Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Linoleic acid, β-carotene, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), potassium ferrycianide, α-tocopherol, ferric chloride trichloro acetic acid (TCA), and 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) are from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ethanol, hexane, and acetone (99.5% purity) are from Prolabo (Couëron, France). Ethyl acetate is from Pharmacia (Uppsala, Sweden). Acetic acid (99.9% purity) is from Carlo Erba (Val-de-Reuil, France). All other chemicals are of analytical grade.

3.2. Enzymes

The chicken pancreatic lipase CPL and the bacterial lipase from Staphylococcus xylosus (SXL) were purified as described previously [45,46].

3.3. Purification of Piperine and Piperic Acid

Piperine was purified from black pepper (Piper nigrum) extracts using the method previously described [32]. Piperic acid was obtained by the alkaline hydrolysis of piperine. The production of piperic acid and its purification were carried out according to the protocol described previously [49,50]. HPLC analysis was used to ensure the excellent quality of the purified piperine and the piperic acid obtained after its alkaline hydrolysis. The analysis used a C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm). The chromatography was done in an isocratic elution manner using a mobile phase acetonitrile: 50 mM KH2PO4 (pH 3.5) (40:60; v:v) at a 0.6 mL/min flow rate. The detection was followed by measuring the absorbance at 340 nm.

3.4. Bioactive Compounds Determination

3.4.1. Preparation of Plant Extracts

All spices and plants (Table 4) were purchased from a local market (Sfax, Tunisia) and identified by a taxonomist at the Department of Biological Engineering, National Institute of Applied Science and Technology (Tunis, Tunisia). The ginger rhizomes (Zingiber officinale) and the leaves of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) and sage (Salvia officinalis) were dried in the dark and ground until a fine powder was obtained. Each plant powder (5 g) was extracted by reflux for 2 h with 100 mL of solvent at different polarities: water, ethanol, and ethyl acetate. After extraction, the suspensions were filtered through a Buchner funnel. The ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts were concentrated using a rotary evaporator Büchi Rotavapor R-200 (Büchi, Flawil, Switzerland) at 50 °C while the water extract was lyophilized using CHRIST Alpha 1-2 LSC Basic freeze dryers (Martin Christ, Osterode an Harz, Germany). The extraction yield was calculated as follows [51]:

Table 4.

List of plant spices and pure molecules used in this present study.

The obtained extracts were packed in glass bottles and stored at 4 °C until use.

3.4.2. Total Phenolic Content

The plant samples’ total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using the modified Folin–Ciocalteu method described by [52]. Briefly, plant samples were appropriately diluted, and 0.5 mL was mixed with 2.5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteau reagent and 2 mL of Na2CO3 (7.5%). After the incubation of the final mixture for 15 min at room temperature and dark conditions, absorbance at 760 nm was measured using a UV mini 1240 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan). A standard curve equation was prepared using gallic acid, and results were expressed as milligrams equivalent gallic acid per g of extract (mg GAE/g).

3.4.3. Total Flavonoid Content

Determination of the plant samples’ total flavonoid content (TFC) was carried out according to the method described previously [53]. One mL of each extract was added to 4 mL of distilled water, then mixed with 0.3 mL of NaNO2 (5%, w/v), 0.3 mL of AlCl3 (10%, w/v), and 2 mL of NaOH (1 M). The total mixture volume was finalized to 10 mL by distilled water. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 510 nm. TFC was expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalent per g of plant extract (mg QE/g).

3.5. Biological Activity Determination

3.5.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

The 1,1 Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay was evaluated as described previously [54] with some modifications. A stock solution (10 mg/mL each) of the various extracts of sage, thyme, ginger, and purified piperine and piperic acid was prepared in absolute ethanol. All samples were used at concentrations of 20–300 µg/mL. Then, 500 µL of each sample was mixed with 500 µL ethanol and 125 µL of freshly prepared solution of 0.02% DPPH in 99.5% ethanol. The mixture was shaken vigorously and incubated (using Eppendorf tubes) at room temperature in darkness for 60 min. The absorbance of the remaining DPPH radicals was read at 519 nm using a UV mini 1240 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan). The scavenging of DPPH radicals was calculated according to the following equation:

where Acontrol is the absorbance at 517 nm of 875 μL of ethanol (99.5%) mixed with 125 μL of ethanolic DPPH solution (0.02%) and Asample is the absorbance of the sample [50,55]. The IC50 value (extracted from the obtained experimental data) was defined as the extract or molecule concentration necessary to reduce the initial concentration of DPPH radicals by 50% (The lower the value of IC50, the higher the antioxidant activity). The values were done in triplicate and given as mean ± SD.

3.5.2. β-Carotene-Linoleic Acid Assay

The antioxidant activity of the various solvent extracts of sage, thyme, and ginger, as well as piperine and piperic acid, was assessed in the β-carotene-linoleic acid system, as described previously [56]. A stock solution was prepared: 0.5 mg β-carotene, 25 µL of linoleic acid, and 200 µL of tween 40 were dissolved in 1 mL of chloroform (HPLC grade). Chloroform was evaporated entirely under a vacuum in a rotary evaporator at 40 °C, and then 100 mL of distilled water was added with vigorous shaking. The reaction medium contained 500 µL of each sample and 2.5 mL of the freshly prepared emulsion. All the test tubes were immediately placed in a water bath at 50 °C for 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 470 nm before and after heat treatment. A control containing 0.5 mL of ethanol instead of the sample solution was carried out in parallel. The IC50 value (extracted from the obtained experimental data) was defined as the concentration of extract or molecule with 50% of antioxidant activity. The values were presented as the mean of triplicate analysis.

3.5.3. DNA Nicking Assay

The ability of the various extracts and purified molecules to protect DNA against oxidation by hydroxyl radicals generated by the Fenton reaction was evaluated according to the method described previously [57]. The native plasmid was incubated with the various plant extracts, piperine, and piperic acid in the presence of Fenton’s reagent. A negative control (plasmid + Fenton’s reagent) and a positive control (containing quercetin as a protective agent) were prepared.

3.5.4. Antibacterial Activity

To determine the antimicrobial activity of the various extracts of sage, thyme, and ginger, as well as piperine and piperic acid, various Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria were used: Escherichia coli, Salmonella sp., Shigella sonnei, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29122).

Briefly, the dried extracts were dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm nylon membrane filter. The bacterial strains were cultured in a nutriment broth for 24 h. Then, 200 μL of culture suspensions (106 colony-forming units estimated by absorbance at 600 nm) was spread onto the surface of Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates. Then, 20 μL of each extract was loaded into wells (6 mm diameter) punched in the agar layer using a sterile 6 mm borer. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as the negative control. Ampicillin and streptomycin were positive reference standards used at 20 μg/well. Subsequently, sample extract plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The antimicrobial activity was evaluated by determining the growth inhibition zone (diameter expressed in millimeters) around the wells. All experiments were done in triplicates.

3.6. Lipase Activity Measurement

The enzymatic activity of the lipase was measured using a pH-Stat (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland) according to the protocol described by [45,46]. Lipase activity is defined as the amount of fatty acid released per minute. One international unit (UI) of lipase activity is defined as the amount of lipase that catalyzes the liberation of 1 µmol of fatty acid per minute.

CPL activity was measured at 37 °C and pH 8.5 using 10 mL of an olive oil emulsion (10% olive oil in 10% Arabic gum) in 20 mL distilled water with 4 mM sodium taurodeoxycholate (NaTDC). Pure colipase was added to the reaction medium at a molar excess of 100 to CPL [45]. The Staphylococcus xylosus (SXL) lipase assay contained 10 mL of 10% an olive oil emulsion in 20 mL distilled water in the presence of 2 mM NaTDC, 2.5 mM Tris- HCl (pH 8.5) and 2 mM CaCl2. The activity was measured at 37 °C and pH 8.5 [46].

3.7. Lipases Inhibition Measurement

Three methods were adapted to study the influence of the extracts and molecules tested on the pancreatic and bacterial lipase activities; inhibition methods A, B, and C were used as described previously [47].

Method A: Lipase/inhibitor pre-incubation method. This method was set up to test the inhibitory effect in an aqueous medium without substrate. The pure enzymatic solution was pre-incubated with different concentrations of extracts and purified molecules for 10 min. The residual activity was then measured under standard conditions, using an olive oil emulsion as substrate.

Method B: Inactivation during lipolysis method. This method was designed to test whether any inactivation reaction occurred in the presence of a water-insoluble substrate during lipase hydrolysis. The plant extract or the purified molecules were added to the assay medium 2 min after the addition of the lipase and at a final concentration in the reaction medium equal to 1 mg/mL. The inhibitory effect was determined by measuring the enzymatic activity before and after adding the sample.

Method C: Poisoned interface method. The samples were added to the reaction medium containing the substrate at a final concentration of 1 mg/mL. After 1 min of incubation, the lipase was injected into the reaction medium. The lipase activity was measured under standard conditions for each enzyme using an olive oil emulsion as a substrate. A control was prepared under the same conditions but without an extract. The inhibition percentage was determined according to the following formula:

where T is the lipase activity of the control, and E is the lipase activity in the presence of different extracts or purified molecules.

The IC50 was defined as an inhibitor concentration (extract, piperine, or piperic acid) that reduces the lipase activity by 50%. IC50 values were extracted from the experimental curves and histograms.

4. Conclusions

In this study, sage, thyme, and ginger plant extracts have been prepared using water, ethanol, and ethyl acetate as extraction solvents. Piperine was purified from black pepper (P. nigrum), while piperic acid was obtained by alkaline hydrolysis of piperine with a conversion yield of 79.2%. The different plant extracts and the purified molecules have considerable antioxidant activities. This activity depends on the extraction solvent and the method used. Ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts had significant radical scavenging activity. However, aqueous extracts of sage and thyme are more active when using the β-carotene-linoleic acid assay.

Moreover, the study of their antibacterial activity has shown that piperic acid has a significant antibacterial power directed against pathogenic Gram− and Gram+ strains. In addition, the inhibition study of chicken pancreatic lipase (CPL) and Staphylococcus xylosus lipase (SXL) showed complete inhibition of SXL with piperic acid using the A and C methods. Drastic CPL and SXL inhibition was observed with the ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of sage, thyme, and ginger using the three methods. Our results suggest that piperic acid and the studied extracts may play an important role in the pharmacological field as potent anti-obesity and anti-acne agents.

Author Contributions

A.S.: Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration. A.M.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft. O.A.A.: Writing—Review and Editing. A.H.-S.: Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant No. UJ-23-DR-96. Therefore, the authors thank the University of Jeddah for its technical and financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This research does not involve human participants or animal experiments.

Data Availability Statement

All the relevant data have been provided in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Haththotuwa, R.N.; Wijeyaratne, C.N.; Senarath, U. Worldwide Epidemic of Obesity. In Obesity and Obstetrics; Mahmood, T.A., Arulkumaran, S., Chervenak, F.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 3–8. ISBN 9780128179215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, D.; Mohajan, H.K. Obesity and Its Related Diseases: A New Escalating Alarming in Global Health. J. Innov. Med. Res. 2023, 2, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagou, M.K.; Karagiannis, G.S. Obesity-Induced Thymic Involution and Cancer Risk. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 93, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.H. Exploring Acne Treatments: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Emerging Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leheste, J.R.; Ruvolo, K.E.; Chrostowski, J.E.; Rivera, K.; Husko, C.; Miceli, A.; Selig, M.K.; Brüggemann, H.; Torres, G.P. Acnes-Driven Disease Pathology: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Giudice, P. Skin Infections Caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, M.; Cho, O.; Sugita, T. Inhibition of Propionibacterium acnes Lipase Activity by the Antifungal Agent Ketoconazole. Microbiol. Immunol. 2017, 61, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horchani, H.; Mosbah, H.; Salem, N.B.; Gargouri, Y.; Sayari, A. Biochemical and Molecular Characterisation of a Thermoactive, Alkaline and Detergent-Stable Lipase from a Newly Isolated Staphylococcus aureus Strain. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2009, 56, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, K.; Varshney, K.R. Study of Microbiological Spectrum in Acne Vulgaris: An in Vitro Study. Sch. J. Appl. Med. Sci. 2013, 1, 724–727. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.; Pathak, R.; Mary, P.B.; Jha, D.; Sardana, K.; Gautam, H.K. New Insights into Acne Pathogenesis: Exploring the Role of Acne-Associated Microbial Populations. Dermatol. Sin. 2016, 34, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-T.; Liu, X.-T.; Chen, Q.-X.; Shi, Y. Lipase Inhibitors for Obesity: A Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, N.F.; Ebeid, A.M.; Khalil, R.M. New Insights into Weight Management by Orlistat in Comparison with Cinnamon as a Natural Lipase Inhibitor. Endocrine 2019, 67, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarika, N. Acne Vulgaris: New Evidence in Pathogenesis and Future Modalities of Treatment. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2019, 32, 1654075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakase, K.; Momose, M.; Yukawa, T.; Nakaminami, H. Development of Skin Sebum Medium and Inhibition of Lipase Activity in Cutibacterium acnes by Oleic Acid. Access Microbiol. 2022, 4, acmi000397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Canha, M.N.; Komarnytsky, S.; Langhansova, L.; Lall, N. Exploring the Anti-Acne Potential of Impepho [Helichrysum odoratissimum (L.) Sweet] to Combat Cutibacterium acnes Virulence. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippatos, T.D.; Derdemezis, C.S.; Gazi, I.F.; Nakou, E.S.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Elisaf, M.S. Orlistat-Associated Adverse Effects and Drug Interactions: A Critical Review. Drug Saf. 2008, 31, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sall, D.; Wang, J.; Rashkin, M.; Welch, M.; Droege, C.; Schauer, D. Orlistat-Induced Fulminant Hepatic Failure. Clin. Obes. 2014, 4, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrelli, M. Medicinal Plants. Plants 2021, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, J.d.S.; Guimarães, R.d.C.A.; Zorgetto-Pinheiro, V.A.; Fernandes, C.D.P.; Marcelino, G.; Bogo, D.; de Cássia Freitas, K.; Hiane, P.A.; de Pádua Melo, E.S.; Vilela, M.L.B.; et al. Natural Antioxidant Evaluation: A Review of Detection Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F. Antioxidants: Principles and Applications. In Handbook of Antioxidants for Food Preservation; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Martemucci, G.; Costagliola, C.; Mariano, M.; D’andrea, L.; Napolitano, P.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Free Radical Properties, Source and Targets, Antioxidant Consumption and Health. Oxygen 2022, 2, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaskova, A.; Mlcek, J. New Insights of the Application of Water or Ethanol-Water Plant Extract Rich in Active Compounds in Food. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1118761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moomin, A.; Russell, W.R.; Knott, R.M.; Scobbie, L.; Mensah, K.B.; Adu-Gyamfi, P.K.T.; Duthie, S.J. Season, Storage and Extraction Method Impact on the Phytochemical Profile of Terminalia ivorensis. MBC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-F.; Chang, Y.-Q.; Deng, J.; Li, W.-X.; Jian, J.; Gao, J.-S.; Wan, X.; Gao, H.; Kurihara, H.; Sun, P.-H.; et al. Prediction and Evaluation of the Lipase Inhibitory Activities of Tea Polyphenols with 3D-QSAR Models. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, T.B.V.; Dias, M.I.; Pereira, C.; Mandim, F.; Ivanov, M.; Soković, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barros, L.; Seixas, F.A.V.; Bracht, A.; et al. Purple Tea: Chemical Characterization and Evaluation as Inhibitor of Pancreatic lipase and Fat Digestion in Mice. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Ikeda, Y.; Ito, M.; Kimura, T.; Ikeuchi, T.; Takita, T.; Yasukawa, K. Inhibition of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase by Morus Australis Fruit Extract and Its Components Iminosugar, Anthocyanin, and Glucose. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 1672–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakaiah, V.; Dakshinamoorthi, A.; Ty, S.S. Novel Aspects in Inhibiting Pancreatic Lipase with Potential New Compound from Nutmeg in Connection with Obesity—in Vitro, in Silico, in Vivo and Ex Vivo Studies. Maedica—A J. Clin. Med. 2021, 16, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unusan, N. Proanthocyanidins in Grape Seeds: An Updated Review of Their Health Benefits and Potential Uses in the Food Industry. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 67, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, J.S.; Jeong, H.I.; Lee, K.W.; Kang, T.H. Anti-Obesity Effect of DKB-117 through the Inhibition of Pancreatic Lipase and α-Amylase Activity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Yin, Z.-P.; Zheng, G.; Chen, J.-G.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Q. Quercetin Is a Promising Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitor in Reducing Fat Absorption in Vivo. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallel, F.; Driss, D.; Chaari, F.; Belghith, L.; Bouaziz, F.; Ghorbel, R.; Chaabouni, S.E. Garlic (Allium sativum L.) Husk Waste as a Potential Source of Phenolic Compounds: Influence of Extracting Solvents on Its Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Borjihan, G.; Bai, R.; Sun, Z.; Bao, N.; Chen, X.; Jing, X. Synthesis and Anti-Hyperlipidemic Activity of a Novel Starch Piperinic Ester. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 71, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, S.Y. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Compounds in Selected Herbs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5165–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, I.; Krastanov, A.; Stoyanova, A.; Denev, P.; Gargova, S. Antioxidant Activity of a Ginger Extract (Zingiber officinale). Food Chem. 2007, 102, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorczyk, I.; Matkowski, A.; Wysokińska, H. Antioxidant Activity of Extracts from in Vitro Cultures of Salvia officinalis L. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, J.; Flieger, W.; Baj, J.; Maciejewski, R. Antioxidants: Classification, Natural Sources, Activity/Capacity Measurements, and Usefulness for the Synthesis of Nanoparticles. Materials 2021, 14, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, D.R.; Phillips, D.H. Oxidative DNA Damage Mediated by Copper(II), Iron(II) and Nickel(II) Fenton Reactions: Evidence for Site-Specific Mechanisms in the Formation of Double-Strand Breaks, 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine and Putative Intrastrand Cross-Links. Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1999, 424, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, S.S.; O’Shea, V.L.; Kundu, S. Base-Excision Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage. Nature 2007, 447, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanta, S.; Banerjee, A.; Poddar, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Oxidative DNA Damage Preventive Activity and Antioxidant Potential Of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) Bertoni, a Natural Sweetener. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10962–10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, L.; Fernandez, M.T.; Santos, M.; Rocha, R.; Florêncio, M.H.; Jennings, K.R. Interactions of Flavonoids with Iron and Copper Ions: A Mechanism for Their Antioxidant Activity. Free. Radic. Res. 2002, 36, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghe, V.A.; Vlietinck, A.J. Screening Methods for Antibacterial and Antiviral Agents from Higher Plants. Methods Biochem. 1991, 6, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bayati, F.A. Synergistic Antibacterial Activity between Thymus Vulgaris and Pimpinella Anisum Essential Oils and Methanol Extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, M.; Jarraya, R.; Lassoued, I.; Masmoudi, O.; Damak, M.; Nasri, M. GC/MS and LC/MS Analysis, and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Various Solvent Extracts from Mirabilis Jalapa Tubers. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truba, J.; Stanisławska, I.; Walasek, M.; Wieczorkowska, W.; Woliński, K.; Buchholz, T.; Melzig, M.F.; Czerwińska, M.E. Inhibition of Digestive Enzymes and Antioxidant Activity of Extracts from Fruits of Cornus Alba, Cornus sanguinea Subsp. Hungarica and Cornus florida—A Comparative Study. Plants 2020, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fendri, A.; Frikha, F.; Mosbah, H.; Miled, N.; Zouari, N.; Ben Bacha, A.; Sayari, A.; Mejdoub, H.; Gargouri, Y. Biochemical Characterization, Cloning, and Molecular Modelling of Chicken Pancreatic Lipase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 451, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbah, H.; Sayari, A.; Mejdoub, H.; Dhouib, H.; Gargouri, Y. Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of Staphylococcus xylosus Lipase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gen. Subj. 2005, 1723, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadrich, F.; Cherif, S.; Gargouri, Y.T.; Sayari, A. Antioxidant and Lipase Inhibitory Activities and Essential Oil Composition of Pomegranate Peel Extracts. J. Oleo Sci. 2014, 63, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, D.A.; Ilic, N.; Poulev, A.; Brasaemle, D.L.; Fried, S.K.; Raskin, I. Inhibitory Effects of Grape Seed Extract on Lipases. Nutrition 2003, 19, 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Narain, U.; Mishra, R.; Misra, K. Design, Development and Synthesis of Mixed Bioconjugates of Piperic Acid–Glycine, Curcumin–Glycine/Alanine and Curcumin–Glycine–Piperic Acid and Their Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarai, Z.; Boujelbene, E.; Ben Salem, N.; Gargouri, Y.; Sayari, A. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Various Solvent Extracts, Piperine and Piperic Acid from Piper nigrum. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, H.; Shad, M.A.; Rehman, N.; Andaleeb, H.; Ullah, N.; Nawaz, H.; Shad, M.A.; Rehman, N.; Andaleeb, H.; Ullah, N. Effect of Solvent Polarity on Extraction Yield and Antioxidant Properties of Phytochemicals from Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Seeds. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Caliskan, O.; Tornuk, F.; Ozcan, N.; Yalcin, H.; Baslar, M.; Sagdic, O. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Mineral, Volatile, Physicochemical and Microbiological Characteristics of Traditional Home-Made Turkish Vinegars. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The Determination of Flavonoid Contents in Mulberry and Their Scavenging Effects on Superoxide Radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersuder, P.; Hole, M.; Smith, G. Antioxidants from a Heated Histidine-Glucose Model System. I: Investigation of the Antioxidant Role of Histidine and Isolation of Antioxidants by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1998, 75, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouka, P.; Priftis, A.; Stagos, D.; Angelis, A.; Stathopoulos, P.; Xinos, N.; Skaltsounis, A.; Mamoulakis, C.; Tsatsakis, A.; Spandidos, D.A.; et al. Assessment of the Antioxidant Activity of an Olive Oil Total Polyphenolic Fraction and Hydroxytyrosol from a Greek Olea Europea Variety in Endothelial Cells and Myoblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowndhararajan, K.; Siddhuraju, P.; Manian, S. Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenging Capacity of the Underutilized Legume, Vigna vexillata (L.) A. Rich. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leba, L.-J.; Brunschwig, C.; Saout, M.; Martial, K.; Vulcain, E.; Bereau, D.; Robinson, J.-C. Optimization of a DNA Nicking Assay to Evaluate Oenocarpus bataua and Camellia sinensis Antioxidant Capacity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 18023–18039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).