Abstract

Authentication mechanisms attract considerable research interest due to the protective role they offer, and when they fail, the system becomes vulnerable and immediately exposed to attacks. Blockchain technology was recently incorporated to enhance authentication mechanisms through its inherited specifications that cover higher security requirements. This article proposes a dynamic multi-factor authentication (MFA) mechanism based on blockchain technology. The approach combines a honeytoken authentication method implemented with smart contracts and deploys the dynamic change of honeytokens for enhanced security. Two additional random numbers are inserted into the honeytoken within the smart contract for protection from potential attackers, forming a triad of values. The produced set is then imported into a dynamic hash algorithm that changes daily, introducing an additional layer of complexity and unpredictability. The honeytokens are securely transferred to the user through a dedicated and safe communication channel, ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of this critical authentication factor. Extensive evaluation and threat analysis of the proposed blockchain-based MFA dynamic mechanism (BMFA) demonstrate that it meets high-security standards and possesses essential properties that give prospects for future use in many domains.

1. Introduction

Authentication is the prime concern when providing legitimate access to a system before assigning privileges for its proper use. Although recent research works have demonstrated the potential to cover a large number of known vulnerabilities, any authentication mechanism could be proven too weak to protect a system [1]. Two-factor authentication (2FA) mechanisms and multi-factor authentication (MFA) mechanisms have brought together the efforts of many different research groups as an attempt to solve common problems. Although the use of the same device as the single point to enter all factors is acceptable by authentication mechanism issuers, cases of stolen devices remain an unaddressed problem [2]. The aim, accordingly to enhance system access by deploying strong authentication mechanisms, has not been met yet.

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) mechanisms require more than two credentials to verify a user’s identity. These factors ensure that the security technique significantly enhances the levels of protection against advanced attacks, especially masquerading attacks. Factors are related to users through knowledge (e.g., password), possession properties (e.g., token), or personal unique features (e.g., fingerprint).

Honeytokens is a method of decoying passwords inserted into a list of passwords and permuting the items to prevent and detect unauthorized access. If an attacker tries to use one of these honeytokens, but not the correct one, an alert is triggered, signaling a potential system compromise.

A novel authentication method that combines honeytokens and Google Authenticator has been recently introduced in [3]. The method resembles a two-factor authentication procedure, but in reality, it works like a multi-factor authentication one by incorporating honeytokens. Honeytokens have been used to mix up the real token with fake ones.

The problems encountered in the honeytoken MFA method require the incorporation of cutting-edge technologies to ensure higher levels of security with certain properties. Blockchain technology is a distributed architecture that permits sharing, provides mutual trust, and holds the property of immutability [4]. In authentication procedures, blockchain supports auditing processes, OTP verification, and shields data stored against tampering with illegals.

This article proposes a blockchain-based MFA (BMFA) dynamic mechanism that combines Blockchain technology with the honeytoken method. It is an extended and substantially revised version of our earlier work presented at ICS-CSR 2024 (ARES 2024) [5], incorporating a redesigned four-factor authentication architecture, new implementation and validation algorithms, comprehensive security evaluation, expanded related work, and additional figures and analysis. The proposed mechanism is designed and implemented to improve existing authentication standards and enforce MFA procedures against attacks that have endured through time.

The main contributions of the proposed BMFA mechanism are listed in the sequel:

- Honeytokens and Ethereum: The proposed BMFA method incorporates the Ethereum blockchain technology to provide multi-factor authentication (MFA) and combines the honeytoken technology to enhance security. The selected novel approach strengthens user authentication mechanisms included in a decentralized ecosystem and adds extra levels of security.

- Honeytoken Integration into Smart Contracts: The integration of honeytokens into smart contracts provides a secure and unchangeable environment [6], properties inherited from blockchain technology, known as the immutability feature [7]. Beyond user identity verification, smart contracts strengthen authentication mechanisms by including an additional tamper-resistance layer that prevents illegal access or alterations.

- Dynamic Honeytokens: In the realm of contemporary cybersecurity, the strategic utilization of honeytokens has emerged as a critical line of defense against potential threats. In our pursuit of heightened security measures, we have devised an innovative approach to honeytoken implementation—a dynamic system wherein the token undergoes continuous change with each user login. The proposed mechanism introduces an element of adaptability, generating a distinctive token for every login instance. This dynamic feature not only elevates the overall security posture but also ensures that users consistently receive the accurate honeytoken on one communication channel while encountering a set of three distinct honeytokens on another. This multifaceted approach adds complexity against potential adversaries, fortifying defenses against unauthorized access and malicious activities. As we advance cybersecurity protocols, the dynamic honeytoken system is robust against evolving threats.

- Honeytokens for Early Threat Detection: Decoy data, known as honeytokens, have been deliberately inserted into a system and aim at luring attackers. Organizations can lure the attackers by integrating honeytokens into smart contracts, which, upon activation, raise alerts to any potential security incident. The early detection and mitigation of such threats are feasible when this technique is applied.

- Time Delay: Smart contracts usually have time delays that range from 1 s to 1 min [6]. Specifically, Ethereum has a block time of around 15 s. On average, a new block is added to the Ethereum blockchain approximately every 15 s. However, during periods of high network congestion or if users set lower gas fees, it might take longer for a transaction to be confirmed. Similarly, Bitcoin has a longer block time, approximately 10 min. This means that, on average, a new block is mined every 10 min, and smart contract capabilities on Bitcoin are more limited compared to platforms like Ethereum. The proposed authentication mechanism overcomes these time delays, and its operation is not affected by them.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents related works that incorporate blockchain solutions into authentication mechanisms. Section 3 first describes the design of the BMFA mechanism with the use of an example that explains elements and related security concerns. The interoperability of the components that the mechanism is composed of is thoroughly discussed and illustrated in a sequence diagram. Next, details regarding the BMFA mechanism implementation are presented through the registration and login phases, and the smart contract data validation and retrieval algorithm is provided. Section 4 evaluates and assesses the BMFA dynamic mechanism against various security challenges. Conclusions and future work summarize the proposed research work in Section 5.

2. Related Work

This section reviews selected papers, which present 2FA methods that incorporate smart contracts and the way they focus on the use of blockchain technology and its decentralized features to improve authentication procedures. These related works include both actual implementations and theoretical frameworks, which offer insightful information for the efficacy and practicality of the 2FA developed approaches.

An early work on a two-factor authentication solution, based on smart contracts, has been presented in [8]. Independent of any trusted third party, without a verifier, the proposed scheme has added an extra layer of security over the OpenSSH server. One of the goals of this research work was to provide a thorough analysis of multi-factor authentication (MFA) schemes, investigating different approaches and techniques utilized in the development of safe authentication systems. A subsequent goal was to evaluate [9] and comprehend the advantages and disadvantages of various MFA designs.

By introducing TrustOTP in [10], the authors address the security and usability issues of current one-time password (OTP) authentication systems, as well as present a unique framework that uses ARM TrustZone technology to combine the flexibility of software tokens with the robustness of hardware tokens. Despite its convenience, traditional software-based OTP generators on smartphones are susceptible to mobile operating system (OS) compromise, which can reveal OTPs or their cryptographic seeds and cause a denial-of-service attack that stops the service. Hardware tokens, on the other hand, provide more robust security but are expensive, hard to update, and heavy for users to carry. By safely separating OTP code, data, and storage within the TrustZone secure domain, TrustOTP circumvents these trade-offs and guarantees that OTP availability, secrecy, and integrity are preserved even if the host operating system malfunctions or is insecure. In addition to safeguarding the generation process, the system adds a trusted input/output pathway, where a secure framebuffer and touchscreen driver ensure that private OTPs and sensitive seeds are not accessed or altered by the untrusted operating system. Without changing the mobile operating system, this design allows users to control several OTP instances and algorithms on a single smartphone while preventing attacks like memory inspection, screenshot taking, and seed exfiltration. The prototype design shows that TrustOTP has little performance and power overhead, resulting in a dependable OTP display in less than 80 ms and a flawless user experience. All things considered, TrustOTP is a useful and effective solution that balances high-assurance authentication in mobile settings with accessibility.

The researchers in [11] address shortcomings in traditional authentication methods by putting forth a multi-factor authentication (MFA) technique that prioritizes cost-effectiveness and accessibility. Conventional login techniques that only use usernames and passwords are extremely vulnerable to phishing, brute force, and credential guessing attacks. Despite being more secure, current MFA solutions frequently rely on hardware tokens, biometric devices, or third-party authenticator apps, which can be costly or impractical for small- and medium-sized businesses. The proposed approach uses graphical passwords as an easily accessible and inexpensive authentication method to get around these obstacles. Users must choose and commit to memory three photos in a specific order to register under the suggested design. Then, they have to replicate these images while logging in. Because this graphical method eliminates direct text input and lessens the possibility of observation-based attacks, it offers resilience against common threats, including keyloggers, screen capture attacks, and shoulder surfing. A total of 170 participants in a user research, categorized by demographics and technical expertise, showed that the approach is useful even for people who are not very aware of security risks. The system’s ease of use, low infrastructure requirements, and improved resistance to intrusions make it a promising alternative for bolstering authentication in resource-constrained environments. It is supported by cognitive psychology, which posits that humans remember images more effectively than abstract words.

Another interesting related approach is proposed in [12]. The primary goal is to provide a multi-factor authentication method for the Internet of Things devices in smart homes. To improve security, the system uses visual cryptography; the purpose of this work is to describe the architecture, stages, and formal analysis of this authentication method. The Digital Memory Authentication Service (DMAS), the service provider (SP), and the user’s smartphone (US) comprise the three-entity system introduced in this work. The process entails encrypting and decrypting digital memory using visual cryptography. The suggested system goes through several stages, such as login and registration, and uses the Scyther tool for formal security analysis.

A blockchain-based MFA model for a cloud-enabled internet of vehicles is introduced in [13]. The authors aim to present a blockchain-based multi-factor authentication paradigm created specifically for cloud-enabled Internet of Vehicles (IoV) applications. The emphasis is given on improving security protocols inside the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) by using multi-factor authentication and blockchain technology. The design and implementation of a multi-factor authentication mechanism based on blockchain technology is the technique employed in this study. Implementing multi-factor authentication on a blockchain platform might solve possible weaknesses and enhance security measures in connected car settings.

The proposed system in [14] integrates blockchain technology, specifically Ethereum, with the MQTT protocol to enhance authentication security in IoT devices. By leveraging and incorporating smart contracts, the system provides an immutable and decentralized authentication mechanism, mitigating reliance on the MQTT broker and traditional transport-layer security protocols. A key feature is the use of a blockchain-based one-time password (OTP) authentication scheme, where OTPs are generated using secure random number generators and transmitted through the Ethereum network, reducing the vulnerabilities associated with conventional single-channel OTP delivery. Privacy is preserved by hashing IPv6 addresses of IoT devices and associating user identities with Ethereum addresses, ensuring anonymity while maintaining accountability through an immutable authentication log. The architecture is designed to be lightweight for IoT devices, offloading computationally intensive operations to the broker and blockchain, thereby minimizing energy consumption on constrained devices.

Honeytokens are tokens, data items, or decoy credentials that are created on purpose and monitored so that an alert is raised when an attacker uses them. Honeywords are fake passwords stored together with the real password; if an attacker submits one of these fake values, the system can detect that the password file has been compromised. More generally, honeytokens can be identifiers, database records, or API keys whose use points to abuse, data exfiltration, or credential stuffing attempts. In our architecture, blockchain-based commitments record the state of honeytokens in an immutable and tamper-evident way. This gives defenders a reliable timeline of suspicious activity and extends classical honeyword/honeytoken techniques to an on-chain commitment and detection workflow.

Despite its security advantages, the system introduces challenges, primarily due to the costs and latency associated with Ethereum transactions, which may not be suitable for real-time applications. The approach assumes the broker’s integrity and the smart contract’s correctness, with any compromise in these components potentially undermining the system’s security. Additionally, while IoT devices benefit from a reduced computational load, the solution increases the energy demands of the Ethereum network, raising concerns about sustainability. The dependency on Ethereum also makes the system susceptible to network congestion and scalability issues. Furthermore, the security of the scheme relies on the secrecy of private keys and the robustness of cryptographic hash functions, where any compromise in these aspects could weaken the overall authentication framework.

By requiring active user engagement, Microsoft Authenticator uses push notifications in its number matching feature that improves multi-factor authentication (MFA) security and reduces the danger of social engineering attacks and approval fatigue [15]. Although it improves authentication procedures by integrating with several authentication situations, such as standard MFA, self-service password resets, and Active Directory Federation Services (AD FS), it does not support wearable devices, which restricts accessibility. Proactive IT management is required because the system’s efficacy depends on Windows Server configurations, NPS extensions, and regular software updates. Number matching improves security posture but creates usability issues like administrative overhead and more friction in authenticating. Although opting out guarantees widespread adoption, it may encounter opposition in settings that value easy access. Organizations should use backup techniques like TOTP, convey changes clearly, and maintain an updated authentication infrastructure to maximize deployment. To reach a compromise between security and usability, future developments should concentrate on extending compatibility with wearables, including biometric alternatives, and implementing adaptive authentication models.

In [16], the main goal is to develop and put into practice a safe two-factor authentication system that makes use of a decentralized application (dApp) and the Ethereum blockchain. The emphasis is on user registration, login procedures, and guaranteeing authentication security by blockchain technology’s decentralized structure. The importance of blockchain for secure communication is emphasized in the article, which also highlights how proof-of-work and hashing techniques make blockchain tamper-proof.

The extensive usage of credit cards for online transactions brought about by the broad acceptance of e-commerce and web-based enterprises has resulted in more complex fraud attempts. In a cashless economy, accurate fraud prevention and detection are crucial. Several techniques, including data mining, blacklisting, and behavioral analysis based on machine learning, have been shown to enhance primary information verification; among these is multi-factor authentication (MFA). Along with credit card details, SMS messages are often delivered to a registered phone as an extra security measure. However, because third-party services are involved, this approach is vulnerable to many types of assaults.

The implementation of blockchain technology as a safe platform for storing second-factor security data is suggested in the study [17]. In particular, a permissioned blockchain contains the user’s mobile device signature, which the bank has verified. Through an easy-to-use QR-code scanning interface, merchants may obtain this information and confirm that the user actually owns the registered device. We outline the architecture of the system, examine any dangers, and carry out a thorough security assessment. The goal of this strategy is to improve multi-factor authentication’s dependability and security for online transactions.

By fusing robust security measures with user-centric design, the introduction of passwordless phone sign-in and number matching in Azure Active Directory (Azure AD)—which uses the Microsoft Authenticator app for multi-factor authentication (MFA)— represents a significant advancement in digital security. By doing away with conventional password inputs, this method improves security by lowering the risks related to password-based authentication. On the other hand, the lack of time constraints and blockchain data transmission techniques presents certain security risks, including replay attacks, man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks, credential stuffing, device theft, brute force attacks, and social engineering attacks. The aforementioned flaws underscore the necessity of instituting temporal constraints and secure data transmission mechanisms, such as blockchain, to fortify the dependability and security of passwordless authentication techniques.

Beyond authentication, several studies examine wider security and efficiency issues in blockchain systems. A well-known early work on blockchain-based financial fraud is by Chen et al. [18], who showed that Ponzi schemes can be encoded directly inside Ethereum smart contracts. Their method extracts features at both the bytecode and the transaction level from more than 3000 contracts and trains an XGBoost classifier that can detect Ponzi-like behavior even when the source code is not available. This underlines the need to include monitoring and misuse detection in any smart contract-based design, including authentication mechanisms such as BMFA.

In addition to security analysis, lightweight blockchain designs have been proposed to handle scalability, storage, and latency limits. Chen et al. [19] proposed LiteChain, a hierarchical and resource-aware blockchain for scalable federated learning, with a CBFT-style consensus and aggressive on-chain pruning to shrink the state size. Their experiments on Hyperledger Fabric report lower latency and reduced storage while keeping verifiability. These lightweight ledger ideas support the design choice behind BMFA, which aims to balance security, on-chain footprint, and overall system performance.

The proposed mechanism holds all the common key fields of the related works discussed above, with emphasis on the smart contract defense, and by adding another security layer, the honeytokens. The honeytokens are a technique that enhances the security of an authentication mechanism by confusing the attacker with decoy tokens. The use of dynamic honeytokens in the proposed approach further advances the authentication security features [20].

3. The BMFA Mechanism

In addressing the imperative need for enhanced security in user system access, we propose a sophisticated blockchain-based multi-factor dynamic authentication mechanism, the BMFA mechanism, that combines conventional authentication methods with cutting-edge techniques to fortify application defenses.

The BMFA mechanism has been designed to include four authentication factors: (1) The knowledge factor, which is something the user is aware of, such as his username and password; (2) the possession factor (TOTP/authenticator or hardware token), an item that the user possesses, like a hardware token, device attestation, or a Google Authenticator TOTP seed; (3) the dynamic honeytokens (including the fake numbers) in the proposed design that serve as a decoy-and-detect technique and the PoN; (4) an optional device or biometric attestation: a cryptographic attestation of a reliable device or something the user is (biometric factor).

3.1. Outline of the Design

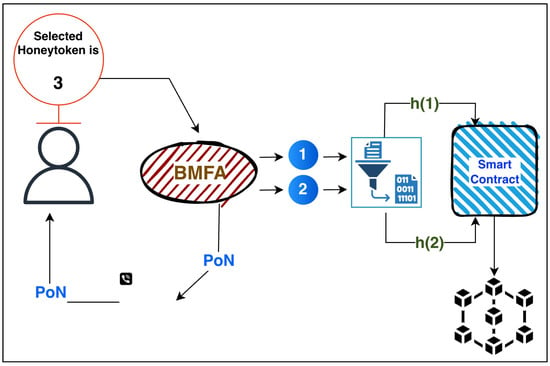

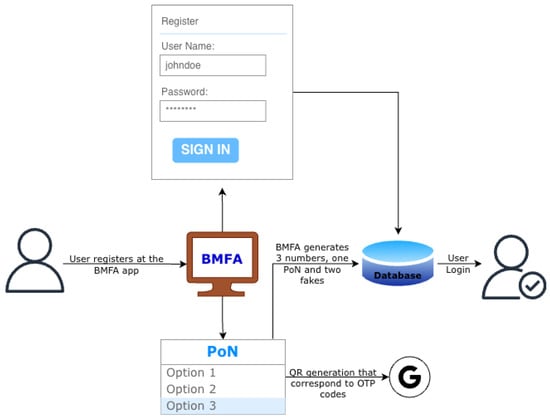

Suppose the following example as illustrated in Figure 1. The user registers and selects honeytoken number 3 as the correct token. The BMFA mechanism will take number 3 as the input and it will produce two additional honeytokens, which are the phony tokens (1 and 2 in circles). Next, the honeytokens are hashed into and , and these hash values are sent to the smart contract. The user will be informed via an application (e.g., Viber, SMS) with the correct PoN (3) (Position Number). The correct PoN is valid per session. If the user logs in again, the PoN will change to a new valid PoN.

Figure 1.

Illustration of BMFA Operation.

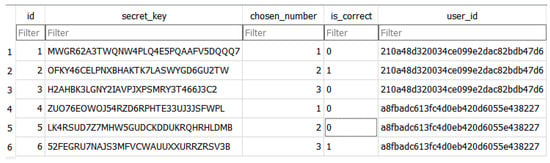

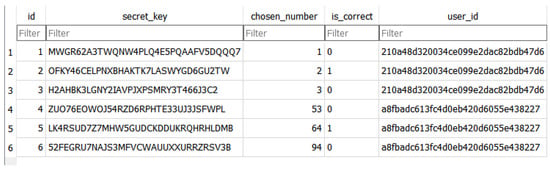

Figure 2 illustrates how the chosen number 3, which is the correct PoN, is recorded in a database when the user first logs in. Rows 4, 5, and 6 correspond to the user of the depicted example. The user ID is encrypted and has the same value. The secret key represents the TOTP that corresponds to the PoN. The PoN is not encrypted for exposition reasons, to show the raw value of the number and better understand the example. In a real environment, the chosen number field is in encrypted form.

Figure 2.

Database at first login.

In Figure 3, the PoN and the value of the PoN have changed after the first login. The user will be notified via email and receive three honeytokens, the two phonies, and the PoN (number 3 in this example). The number will be randomly placed among the honeytokens. If the number is in the first position, then the user will know that the first OTP of the authenticator is the correct one. In this example, if number 3 is placed at the second position, then the user will know that the correct OTP is the second one of the authenticator [21]. Every time the user logs in, the honeytokens change, and so does the PoN, which links to the correct honeytoken. The user will be notified with the correct honeytonen via an SMS or other communication channel.

Figure 3.

Database after the first login.

Ethereum blocks take about 15 s to process. This indicates that a new block is created on the Ethereum blockchain around every 15 s on average. These blocks include the executions of smart contracts. However, it might take longer for a transaction, including the execution of a smart contract, to be verified during times of heavy network congestion or if users select lower gas costs.

The block time for Bitcoin is longer—roughly ten minutes. This indicates that a new block is typically mined every ten minutes or so and that Bitcoin’s smart contract capabilities are more constrained than those of platforms like Ethereum.

In many authentication mechanisms, the OTP codes stored on the blockchain are not useful to the user because the OTP code changes every 30 s. From the time the OTP is stored on the blockchain until the time the user is authenticated by the system with the OTP, the time delay will be an issue for the authentication. In the BMFA mechanism, the time delay of the blockchain will not affect the authentication because the PoN (Position Number) is a number that corresponds to the position of the correct number in the OTP and not to the OTP itself. The Position Number (PoN) is the number where the correct honeyword is placed, the OTP order.

In practice, the end-to-end delay of a smart-contract write in our setup is shaped by three main factors: (i) the average block time on Ethereum, which is around 15 s; (ii) the time a transaction waits in the mempool before it is included, which grows under network congestion or when using a low gas price; (iii) the number of block confirmations the application requires before accepting a result. With common confirmation policies (for example, waiting for a small, fixed number of blocks), the confirmation delay normally falls in the 15–60 s range. Importantly, BMFA does not make the user’s login experience depend on this delay: PoN and honeytoken selection happen off-chain, and the on-chain transaction only provides an auditable commitment, not a blocking step in the authentication flow.

3.2. Components and Interoperability

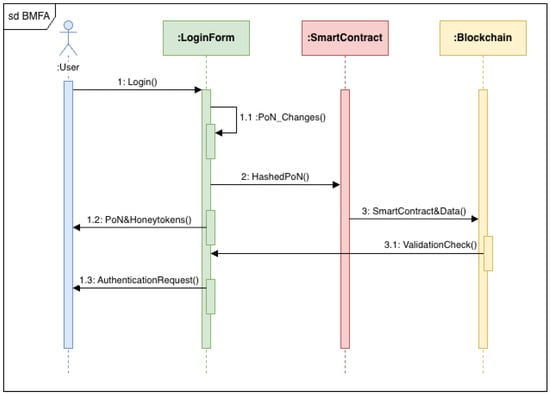

The process that is being displayed in Figure 4 begins with the “USER” performing an action designated as “LOGIN,” which sets off a chain of events involving “OUR APPLICATION.” The application makes modifications marked “PoN CHANGES” after successfully logging in. The user then uses the program to carry out an activity labeled as “PoN WITH HONEYTOKENS” after this. It is implied that this stage may entail some sort of security or fraud detection mechanism since honeytokens are often fictitious data or tokens that are used to identify or monitor unwanted access or requests inside a system. After that, the user receives an “AUTHENTICATION REQUEST” from the program, asking for verification of their identity or the legitimacy of their activities.

Figure 4.

Interoperability between components.

The sequence diagram demonstrates that the program takes the “PoN” and performs an action titled “PoN IS HASHED” at the same time. Data is transformed into a fixed-length character string through the process of hashing. This is usually performed for security purposes so that the original data cannot be easily inferred from the hash. A “SMART CONTRACT,” a self-executing contract with the terms of the agreement directly put into lines of code, receives this hashed data after that. The “BLOCKCHAIN”, an immutable digital ledger that records transactions across several computers to prevent any related record from being changed retrospectively, is where the smart contract is located. To confirm the integrity and validity of the hashed data, the smart contract performs a “VALIDATION CHECK”. The arrow that points from the smart contract to the blockchain and is labeled “SMART CONTRACT WITH HASHING DATA” indicates that, should the validation be successful, the smart contract will engage with the blockchain. Each step in this diagram is significant for ensuring the security and integrity of transactions in a blockchain- enabled application.

3.3. Honeytoken Integration into Smart Contracts

To implement this system, we embed the honeytoken within a smart contract, introducing a dynamic and immutable layer to the authentication process. This smart contract not only validates the user’s identity but also complicates the task for potential attackers through the introduction of two randomly generated numbers [3]. The fusion of the honeytoken with these numbers results in a triplet of values that form the third authentication factor.

3.4. Secure Delivery of Honeytoken

Recognizing the pivotal role of the honeytoken, we establish a dedicated and secure communication channel to deliver this confidential numerical identifier to the user. By ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of the honeytoken delivery, we mitigate the risk of interception and unauthorized access to this critical factor.

This multifaceted approach, combining traditional authentication with advanced smart contract technology, dynamic hashing, and secure delivery channels, collectively forms a robust multi-factor authentication mechanism. The proposed system not only addresses current security challenges but also establishes a dynamic and adaptive framework capable of thwarting evolving threats in the digital landscape.

Each honeytoken represents three OTP codes that were generated when the user registered into the system. Given the above prerequisites, there is no impact on the BMFA mechanism because the number of the OTP code the user chose does not affect the right OTP. The OTP codes add one more security layer and strengthen the mechanism on the side of the “client” in the event someone obtains all three numbers to further confuse the attacker. If the attacker puts an incorrect honeytoken, then the account will be disabled, and an alert will be sent to the user.

3.5. Mechanism Implementation and Functionality

The implementation was performed on a local server with the following specifications: Ryzen 5 2600 3.4 GHz, 6-core CPU, and 16 GB RAM, running on Windows 10. The operation of the proposed mechanism is divided into two phases: the registration phase and the login phase. Detailed descriptions are provided next to offer the technical part of the mechanism implementation.

3.5.1. Registation Phase

The BMFA mechanism operation at the registration phase is illustrated in Figure 5. First, the user must register using the BMFA mechanism, entering a username and password. This is the first factor of the authentication process. The username must be unique, and the password is hashed and stored in the BMFA mechanism. At the same time, the user chooses one number from 1–3 that will represent the One-Time Password 6-digit code. This is the Position Number (PoN) the user has to remember. This number will be stored in the database once hashed.

Figure 5.

The BMFA honeytoken dynamic mechanism—Registration.

The hashing algorithm we have selected is Bcrypt. Bcrypt is designed to be a slow hashing algorithm specifically to resist brute force and rainbow table attacks. The time it would take to “break” a hashed value depends on various factors, including the computational power of the attacker’s hardware and the specific implementation details of the hashing algorithm. Bcrypt is intentionally designed to be slow, so even with relatively fast hardware, it can still take a considerable amount of time to attempt brute force attacks.

At the same time, the BMFA mechanism will generate the corresponding QR images [22] of the OTP codes. When the registration form is completed and submitted, three OTP codes will be generated for the user. The user will get the QR images for scanning to store the OTP codes at the authenticator; the Google Authenticator has been chosen for this implementation. One of them will be the correct OTP that the user will enter, and the other two will be the “Honeywords”.

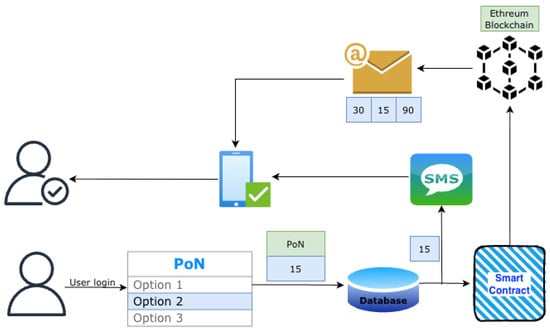

3.5.2. Login Phase

The mechanism operation for the login phase is illustrated in Figure 6. The login phase starts when the user fills the login form with the username and the password. After a successful login, the corresponding PoN with the honeywords will be transferred to the Ethereum blockchain, hashed, and executed with a smart contract. The PoN will be sent to the user via an application chosen by the user (Viber, SMS). Every time the user performs a successful login, the honeytokens change, and so does the PoN. This approach has been selected as a technique to confuse attackers, as the user does not follow one specific pattern. If the attacker observes the same user activity with the same PoN, eventually she will learn the correct token. The correct honeytoken will be sent to the user via SMS or another way (email, Viber). The validation of the honeytokens will take place on another platform according to the user’s preferences (email, SMS, Viber).

Figure 6.

The BMFA honeytoken dynamic mechanism—Login.

The smart contract has been developed using Solidity. Smart contracts on Ethereum need gas to be built and transferred to the blockchain. In this implementation, an Ethereum testnet has been used with its cryptocurrency. The smart contract cannot be altered after its creation. In Ethereum, the blockchain is transparent and decentralized, meaning that all transactions and data on the blockchain are visible to all participants. If one stores a value in a smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain, it will be visible to anyone who participates in this blockchain.

The proposed mechanism retrieves the corresponding smart contract and extracts the information contained. The PoN, together with the other honeywords, will be displayed to the user’s side as an email notification.

We introduce an algorithmic method for data extraction, validation, and visualization from blockchain-based smart contracts efficiently, as depicted in Algorithm 1. The proposed technique starts by taking advantage of the transparent and immutable characteristics of blockchain technology to guarantee data integrity by extracting hash values directly from the smart contract. After extraction, the technique uses a strict validation procedure in which every hash value is carefully compared to a hash of the original data that has already been generated.

Verifying the legitimacy and accuracy of the data received from the blockchain requires this crucial step. The algorithm shows the user the validated data in the last phase when a validation is successful. This end-to-end procedure offers a smooth method for data verification and retrieval, which not only makes data transactions on the blockchain more trustworthy but also greatly increases user experience. The use of this algorithm offers a solid answer to the problems of data integrity and transparency in decentralized networks, with significant ramifications for the field of blockchain technology.

The getNumbers() is the function that implements Algorithm 1 and retrieves the hashed PoN, with the correct order. The user must enter the corresponding OTP code into the BMFA mechanism to successfully continue. The OTP codes will be displayed at an authenticator (Google Authenticator), so when the user obtains the correct honeytoken and the PoN, then the next step is to see the corresponding OTP at the authenticator. If the user logs in with one of the phony codes, then the account will lock, and the user will be alerted with a notification. If the user mistypes the OTP code, then she must try again, from the beginning of the login phase. Too many wrong tries will cause the account to be locked, and the user will be notified.

Experimental Settings and Measurement Procedure: To make our evaluation easy to repeat, all BMFA experiments were run on a local testbed. The application server, smart contract tools, and blockchain client were placed on one machine with a Ryzen 5 2600 CPU (6 cores, 3.4 GHz), 16 GB RAM, and Windows 10. We created a local Ethereum-compatible network and exposed a JSON-RPC endpoint. The BMFA backend used a web3 client library to connect to this endpoint. All parts of the protocol, registration, login, PoN generation, honeytoken rotation, and smart contract calls, were triggered by real HTTP requests sent to the BMFA backend.

For each login attempt, the server performed two steps: (i) it computed the PoN and honeytokens off-chain, and (ii) it sent a commitment transaction on-chain. We treated the transaction as confirmed after N blocks (N = 3 in our setup; see Section 3.6). We used a low gas price to reflect typical public-chain behavior. This setup allowed us to record timings for local computation, contract deployment, transaction submission, and block confirmation. We also logged all blockchain actions through the RPC interface. In this way, the testbed shows how BMFA computation, network delay, and blockchain confirmation time interact, even though a full, large-scale latency study is left for future work.

| Algorithm 1 Smart Contract Data Validation and Retrieval |

|

3.6. Blockchain Client and Testbed Configuration

We deployed the BMFA smart contract (written in Solidity) on an Ethereum-style test network (Infura) running on a local node. The BMFA server connects to this node via an RPC endpoint and uses a web3 client library to sign and send transactions. For each authentication step, the server waits for N block confirmations (N = 3 in our setup) before accepting the on-chain result. We used a conservative gas price to reduce the chance of delayed or dropped transactions when the network is busy.

All blockchain parts (local node, RPC endpoint, and key store) ran on the same isolated test machine as the application server in Section 3.5. This controlled setup keeps network delay and trust assumptions simple and under our control, and it is close to how BMFA would run in a private or permissioned blockchain deployment.

4. Evaluation of the BMFA Dynamic Mechanism

The intersection of blockchain technology and multi-factor authentication (MFA), examined in other related works and discussed previously, offers significant insights to improve security, trust, and privacy in a variety of contexts. These articles are similar in that they make use of the Ethereum blockchain, implement smart contracts, and create novel 2FA authentication mechanisms.

The cornerstone of these investigations is the utilization of blockchain, specifically Ethereum, as a strong framework to reinforce security protocols. A major issue that appears is multi-factor authentication, with a focus on the use of decentralized and trustless systems to reduce the risks associated with single-factor authentication.

The essential components of these systems, smart contracts, automate and enforce blockchain security policies. Creating a reliable and safe environment for authentication procedures is the main objective. These goals are investigated in several contexts, such as generic authentication systems and cross-domain Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT).

Some research introduces decentralized applications (DApps) to improve user interfaces and increase the accessibility and usability of blockchain-based authentication systems. Reducing reliance on third parties is a common goal, supporting decentralized and trustless systems that comply with blockchain norms.

In these suggested systems, the security of data, transactions, and access is largely dependent on cryptographic algorithms. The comparative analysis provides a thorough grasp of the common objectives and approaches of the various improvements made in blockchain-based 2FA systems.

Examining the comparable features shared between the presented related works and the proposed BMFA dynamic mechanism, we conclude that all works have been implemented upon a smart contract platform; two are resistant to MITM attacks, and none of them integrates a dynamic honeytoken to provide advanced security services. The proposed BMFA dynamic mechanism holds all features (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Authentication System Features.

4.1. Evaluation Criteria and Selection Justifications

The evaluation criteria and selection of attacks were based upon several security aspects that are most pertinent to blockchain-based multi-factor authentication systems, and which combine off-chain authentication channels, user-facing elements, and on-chain commitments. In the next paragraphs, certain decisions are explained and justified, and evaluation criteria are disclosed to support the evaluation process of the BMFA mechanism.

Threat Selection

We first located the most significant potential attacks the BMFA mechanism might confront. The selection was based on known vulnerabilities and flaws in blockchain technology, mainly the Ethereum, in tools used in the BMFA mechanism, such as the Solidity and the Google Authenticator, and even threats against hash algorithms, such as the Bcrypt used in this implementation. Then, a risk level was assigned to each of these threats to rank them from low to high.

The risk assignment method follows classifications described in [23,24]:

- Low Risk: The attack is hard to carry out, has little effect, or is well countered by existing defenses.

- Medium Risk: The assault is doable but necessitates particular circumstances, has a moderate effect, or can be lessened with further security.

- High Risk: The assault has serious repercussions, is simple to carry out, or lacks appropriate mitigation techniques.

Table 2 shows the list of potential attacks, a corresponding risk level for each one, and a description that outlines the justification for where the main origin of each threat is. Remarkably, no high-level threat has been revealed, which indicates a fair level of security.

Table 2.

Potential attacks and risk levels.

We proceeded to further assess the proposed BMFA mechanism against the above threats and security-relevant challenges, as well as to compare it with selected related works discussed in Section 2.

- 51% Attack: An extra line of protection can be added to the blockchain system by introducing honeytokens. In essence, honeytokens are lure assets that mimic real ones to potential attackers. An attacker may interact with these honeytokens if their main goal is system manipulation [25], which could notify the network of their presence and possibly lead to the activation of countermeasures.

- Sybil Attack: By making it expensive to generate numerous false identities, Ethereum’s PoS mechanism helps prevent Sybil assaults [26]. However, attackers might still target OTP delivery systems by flooding the system with phony accounts. The system can identify and report questionable authentication attempts from these phony identities by using honeytokens as decoy credentials. The system can recognize and react to Sybil-based threats by keeping an eye on interactions with honeytokens.

- Smart Contract Exploits: By incorporating honeytokens into smart contracts, vulnerabilities can be found early on [27]. An attacker may unintentionally set off the honeytoken, indicating the existence of malicious behavior, if they try to take advantage of a smart contract.

- Routing Attack: Attackers may be able to obtain authentication codes by intercepting OTP packets while they are being transmitted [28]. The system can use offline OTP techniques that do not depend on network delivery, like Google Authenticator, to tackle this. When an attacker tries to use a honeytoken, it indicates that the OTP was intercepted, enabling the system to implement countermeasures such as preventing access from dubious sources. Honeytokens can also be presented as phony OTPs.

- Phishing Attack: Using phony websites or misleading messages, attackers can try to fool users into revealing their login credentials [29]. By functioning as bait, honeytokens can be a potent defense. If an attacker unintentionally uses a honeytoken credential, the system can quickly identify the phishing attempt and take the appropriate action. This strategy strengthens defenses against phishing attempts when paired with password managers and user education.

- Reentrancy Attack: If authentication depends on contract logic, reentrancy attacks [30] could still be dangerous, even though their main target is smart contracts that retain money. By adhering to best practices such as the Checks–Effects–Interaction pattern [31], the system can reduce this. By being incorporated into smart contracts, honeytokens can further enhance security. If an attacker initiates a honeytoken interaction through recursive calls, the system can identify and stop the attack before it goes out of control.

- Eclipse Attack: By postponing or altering authentication replies, attackers may try to block an Ethereum node from the network [32]. If blockchain data is used via authentication methods, this could be risky. By being inserted into network interactions regularly, honeytokens can aid in the detection of such assaults. Should an anticipated honeytoken interaction not take place as planned, it may signal that a node is being attacked, triggering defensive measures such as node switching or peer connection refreshes.

- Timejacking Attack: To obtain an edge, an attacker can alter the timestamps of the blockchain, which could have an impact on time-sensitive authentication systems [33]. This risk is reduced by timestamp validation techniques, which make sure that the system will not accept changed time values. By including timestamps in decoy transactions, honeytokens can strengthen this defense. Should a honeytoken interaction take place with an inaccurate timestamp, the system can identify the anomaly and reject the transaction.

- Dusting Attack: Sending small amounts of cryptocurrency to wallets to track transactions and de-anonymize users is known as a “dusting attack” [34]. Honeytokens could be used as bait transactions to find and identify attackers trying to track user activity, even though this kind of attack has nothing to do with authentication. The system can keep an eye on an attacker’s activities and take action if they use honeytoken dust transactions.

- Double-Spending Attack: It is possible to deliberately insert honeytokens into the blockchain to serve as bait for prospective double-spending attacks [35]. If an attacker tries to engage in double-spending through these honeytoken interactions, the network can identify the irregularity and initiate remedial measures, such as stopping transactions or notifying administrators.

- Bridge Attack: By taking advantage of flaws in the systems that move assets between blockchains, bridge attacks target cross-chain solutions [36]. This danger is negligible if cross-chain activities are not used in the authentication system. If cross-chain interactions are included in the future, honeytokens can be used as test transactions to find anomalies and help find weaknesses before attackers take advantage of them.

- Flash Loan Attack: These attacks, which use uncollateralized loans to influence market circumstances, are primarily pertinent to DeFi applications [37]. This kind of attack is not a particular problem because the authentication process does not entail loans or financial transactions. On the other hand, honeytokens might be used to mimic transactions and spot possible vulnerabilities before they are taken advantage of if financial activities are eventually incorporated.

- Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attack: The BMFA mechanism secures against MITM attacks [38] by employing a physical instance for secure number communication. The presented research work, though not directly addressing MITM attacks, benefits from the use of blockchain and smart contracts, contributing to overall security.

- Brute Force Attack: The BMFA mechanism introduces complexity by the use of the Bcrypt hashing algorithm and by employing user-specific numbers, making brute force attacks more challenging. This research work, while not explicitly mentioning defense against brute force attacks [39], aligns with the principle of the Bcrypt hashing algorithm for advanced security.

- Honeytokens: The BMFA mechanism introduces decoy numbers, adding an extra layer of confusion for potential attackers, a unique aspect not explicitly covered in the related works.

4.2. Evaluation

We narrowed the list of attacks by picking attack classes that span the full lifecycle of an authentication transaction in the BMFA mechanism and have been ranked at a medium risk level. These classes together cover network, protocol, code, and human factors that are salient to the BMFA mechanism and to the surveyed literature. Seven classes of attacks were designated.

- Smart Contract Exploits—because any logic or storage placed on-chain (even transiently) introduces contract-level risk (bugs, access-control flaws) that may invalidate authentication guarantees;

- Routing Attacks—because OTP/PoN delivery often traverses third-party carriers or messaging platforms (SMS, Viber, email), so interception or routing manipulation can directly enable account takeover;

- Phishing Attacks—because social engineering remains the dominant human vector and honeytokens are explicitly designed to detect it;

- Eclipse Attacks—because node isolation can distort the on-chain view used for timeliness or rotation assurances;

- Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks—because mixed on-chain/off-chain flows create multiple channels where message integrity and endpoint authentication are required;

- Brute Force Attacks—because passwords, PoN choices, and OTP configurations determine resistance to offline/online guessing;

- Private Key/Secret Compromise—because leakage of signing or long-lived secrets is catastrophic for systems that rely on cryptographic identity or immutable ledgers.

The selection of the attack classes was based on relevant chosen works for comparison purposes, as they cover a wide range of methods and techniques, including graphical passwords, permissioned ledgers, push-number matching, hardware-assisted OTP, smart contract 2FA, and IoT-focused designs. The same aspects of the system are shared in every design: how to transmit second factors (push, TOTP, QR, in-app), which trust anchors to utilize (hardware enclave, broker, permissioned authority), and where to store secrets (on-chain vs. off-chain). We can observe which architectural decisions shift risk to which layer by selecting attacks that target the blockchain layer, the delivery layer, and the endpoint/secret layer. For example, moving more logic on-chain reduces centralization risk but increases smart contract exposure.

The criteria for determining risk levels (Low, Medium, High) in cybersecurity threats [40], including blockchain security, typically consider the following factors:

- Probability of Occurrence, or likelihood: How frequently does the attack happen in actual situations? Is it possible with the security measures in place now?

- Impact (Attack’s Repercussion): What harm might result from a successful attack? Does it result in system compromise, data exposure, or monetary loss?

- Exploitability (Easy to Implement): How challenging would it be for an attacker to execute this attack? Does it call for a lot of money or sophisticated knowledge?

- Availability of Mitigation (Defense Mechanisms in Place): Are there any countermeasures in place that render the attack useless or drastically lower the likelihood that it will succeed?

- Attack Surface (Scope of Vulnerability): Does the assault impact the entire system or network (big scope) or just a single component (small scope)?

Next, we applied a scoring method. We assigned a score on a scale of 1 to 5 to each attack, assessing the attack’s impact and consequences observed, from 1 being the worst unaddressed consequences to 5 corresponding to efficient counteractions. In particular, ratings took into account four factors: (a) Impact—the possible harm if the attack is successful (data loss, impersonation, irreversible ledger effects); (b) Exploitability/Likelihood—the ease with which an adversary, given the assumptions of the system, could execute the attack; (c) Detectability—the likelihood that the system will detect the attack (logs, alerts, honeytokens); (d) Recoverability/Mitigation Difficulty—the difficulty of repairing the damage, for example, on immutable ledgers remediation is often expensive. To score on the composite judgment across these factors, we applied the same assumptions regarding attacker capabilities for each related work and the BMFA mechanism. These assumptions included a network adversary’s ability to intercept or control network paths, a remote adversary’s ability to attempt social engineering, and a node or service-level adversary’s ability to influence peers.

The goal of this systematic comparison is to identify risk areas in each design and mitigation strategies that work well across designs, not to generate absolute rankings. Hardware enclaves (such as TrustZone) have a high private-key protection score because they significantly minimize local secret extraction. In contrast, public-chain dApps increase auditability but present smart contract and key management issues. Our recommendations are based on these observations: use hardware or threshold signing for high-value keys, opt for authenticated, in-app channels for critical factor delivery, and treat SMS, email, and Viber as fallbacks equipped with server-side signatures and anomaly detection. We also suggest minimizing sensitive on-chain payloads (store commitments, not secrets).

The BMFA mechanism was compared with other related works, which address the same set of selected attacks (medium/high). Table 3 summarizes comparison results on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent). The “N/A” means ’not applicable’ for that research work.

Table 3.

Comparing the BMFA mechanism with other related works on selected attacks (medium/high).

Detection Semantics and Timing Notes: BMFA does not use probabilistic or classifier-based detection. Instead, it works as a simple deterministic trigger: whenever an invalid honeytoken is submitted, the system raises an alert. Because of this design, classical false-positive and false-negative rates from anomaly detection do not directly apply. In our prototype, the main timing cost comes from blockchain confirmation, not from the BMFA logic itself, since on-chain writes depend on network settings and gas price. A full quantitative study, with controlled timing benchmarks and user-level FP/FN analysis, is left for future work.

4.3. Outstanding Security Considerations

In an attempt to cover other security-relevant unconventional challenges, we answer the following exceptional questions:

4.3.1. Is Finding the Smart Contract a Real Threat?

Ethereum is public and transparent, which means anyone can see all transactions. However, to exploit the PoN, an attacker would need to accomplish the following:

- Find the relevant smart contract among millions of transactions.

- Extract the hashed PoN from the contract.

- Attempt to brute force the PoN within 30 s (since OTP expires quickly).

To check the feasibility of the above actions and the possibility of accomplishments, we further examined their required steps:

- Finding the Smart Contract—If the contract address is well-hidden (not tied to a public user ID), an attacker must sift through a lot of data. However, if they monitor all recent transactions, they can track which ones are used for authentication and target them.

- Extracting the Hashed PoN—Since Ethereum is transparent, once they find the contract, they can see the stored hashed PoN.

- Brute-Forcing the PoN (Hash Cracking)—Bcrypt is slow, which is great for security. It makes brute force attacks difficult. However, hashing a number from 1 to 3 is weak. Since there are only 3 possible PoN values, an attacker could pre-compute their hashes and produce pre-computed hash tables (rainbow table attack) and instantly match them. The real security comes from brute-forcing the OTP (6-digit code, 1 million combinations). But if they learn the correct PoN quickly, they only have to guess 6 digits.

4.3.2. Can an Attacker Decrypt the OTP Within 30 s?

Even with a highly optimized setup, the Bcrypt algorithm takes time to compute, so brute force attacks are significantly slowed down. Ethereum latency exists, indicating that the attacker must first identify the correct transaction, extract data, and attempt decryption. Realistically, brute-forcing a 6-digit OTP takes too long in 30 s. However, a more robust attack could involve an adversary monitoring transactions in real time and using GPU-based brute-force to successfully pre-compute PoN hashes. This would allow them to skip step 3 and only guess the OTP, which may take just seconds.

4.4. Scalability: Smart Contract State Size and Mitigations

Hash commitments for the honeytoken PoN and related honeyword hashes are stored inside the prototype smart contract (see Algorithm 1 and its implementation, the getNumbers() retrieval). Because each user only needs one commitment, the on-chain storage grows linearly with the number of users. This provides immutability and a clear audit trail, but it also increases costs. For long-term scalability, the BMFA contract is designed so that storage grows only at O(n) with the number of users, since each user has a single commitment slot. To keep the on-chain state small, we suggest the following simple steps:

- Keep only the latest commitment on-chain. Use a Solidity mapping address (address => bytes32) and overwrite the previous value instead of appending. This keeps on-chain storage balanced per user and drastically reduces growth.

- Keep large/historical data off-chain and commit compactly on-chain. Store bulk or archival data in an encrypted database or a distributed store (e.g., IPFS) and publish a small Merkle root or cryptographic commitment on-chain. This preserves verifiability while avoiding expensive on-chain storage.

- Use events (logs) for auditable change history when possible. If you need a tamper-evident history but can accept lower on-chain persistence guarantees, emit events instead of writing to storage. Events are more inexpensive than STORE and still provide an auditable record for off-chain indexing.

- Amortize gas with L2s or batching. Deploying to Layer-2 networks or batching multiple changes into single transactions reduces per-operation gas costs and could make on-chain commitments viable at scale.

These options depend on the deployment needs and balance immutability with cost. It is suggested that a mixed selection is picked, which matches a threat model and the corresponding budget. The creation and reading of commitments are shown in Section 3.3 and Algorithm 1, and Section 3.5.2 describes detailed steps.

4.5. Limitations

The current BMFA prototype has several limitations. (1) Latency: Because we wait for on-chain confirmation, the authentication flow has an extra delay, which can be a problem for applications that need very low latency. (2) Cost and scalability: Each transaction and each on-chain write consumes gas, so costs grow with the number of users and how often they log in. (3) False alarms and parameter choice: Honeytoken detection needs careful tuning to avoid too many false positives (blocking real users) and false negatives (missing attacks). (4) Adversary adaptation: A skilled attacker may try to avoid touching honeytokens or may trigger many honeytokens on purpose to cause denial of service. (5) Privacy and metadata: If the commitment scheme is not designed with care, even small on-chain commitments can leak metadata or allow correlation between users and events. (6) Node and network dependence: The design assumes honest and available blockchain nodes with an honest majority. Outages, forks, or heavy congestion can reduce or delay detection.

We see these points as important topics for future work. Possible directions include using more off-chain commitments, batching updates to reduce gas usage, adding economic incentives that discourage abuse, and designing privacy-preserving commitment schemes.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The novel BMFA dynamic honeytoken mechanism integrates a dynamic honeytoken method in a blockchain-based authentication scheme to advance the security services required in highly demanded systems. Implementation verifies the feasibility and the significance of the presented scheme. The proposed approach is effective because it mitigates the effects of smart contract time delays, which range from 15 s to one minute in the proposed system. Ethereum blocks take about 15 s on average, although sometimes longer confirmation periods for transactions—including smart contract executions—can be caused by changes in network congestion or user-set gas prices.

The authentication method presented a novel security technique that has as its starting point the construction of an unchangeable and tamper-proof system. Fundamentally, it uses a dynamic honeytoken method, in which a honeytoken is just an 88-character hash. But the system effectively corresponds to this long hash with a single-digit position number rather than sending it directly, which might cause delays, too.

This design decision guarantees that the honeytoken itself does not become a bottleneck or a point of vulnerability because of transmission delays by drastically lowering the possibility of time lag in the authentication process. However, there is a significant payoff for this increased efficiency and security.

From a security perspective, the BMFA mechanism adds a layer of protection over other common blockchain-based multi-factor authentication schemes with the dynamic honeytokens. The combination of the PoN and the dynamic change of the PoN value every time the user logs in enhances the protection provided to the credentials used for a system. If an attacker finds out the value of the PoN, she also needs to know the order of the PoN. If an attacker finds out both the value and the order of the PoN, he will also need the corresponding OTP’s to proceed and enter the system. The complexity of the information an attacker needs to know to successfully attack the BMFA mechanism is a boost to security against attacks.

The application is possible in diverse security domains, including digital education, IoT ecosystems, e-voting systems [41], web-based sensor data access, cross-domain Industrial IoT, and smart home security, and is expected to further demonstrate the potential and the prospects of the proposed approach. Due to its adaptability, the technique can be used to solve a variety of security challenges in a wide range of applications.

Honeytokens integrated into smart contracts are a strong indicator of malicious behavior or illegal access. This might give the feasibility for detection schemes to take advantage of the combination of blockchain technology and honeytokens. Such an alert will be activated in response to any attempt to misuse or exploit smart contracts.

6. Future Work

Another interesting approach to improving the security of the BMFA dynamic honeytoken process is quantum technology. The system can guarantee that authentication data is impervious to being intercepted and decrypted by adversaries, whether classical or quantum, by utilizing quantum cryptography, especially quantum key distribution (QKD). By using quantum-resistant cryptographic methods, honeytoken security may be further enhanced, and future quantum assaults that can jeopardize blockchain-based authentication can be avoided. To further increase the unpredictability of honeytoken generation and make sure that every authentication attempt is immune to pattern analysis and predictive attacks, quantum random number generators, or QRNGs, could be used. In blockchain authentication systems, this quantum-enhanced BMFA technique would offer a future-proof security solution against changing cyber threats.

In order to raise the cost and uncertainty for adversaries, we introduced a unique BMFA mechanism that combines dynamic honeytokens with on-chain commitments and time-based possession factors. The idea and preliminary architecture show promise for hardening multi-factor authentication processes and identifying unwanted access attempts. The conceptual design and preliminary threat reasoning are the main focus of this paper. However, there are still several operational and implementation-level security concerns, which are noted as limitations below that are left for future addressing. Key management, deployment, and company-specific operational controls are examples of detailed production hardening that are purposefully outside the scope of this article and will be covered in industrial implementations.

Research works focusing on assessments or proofs of concept have been prioritized because of their importance. The incorporation of smart contracts in the proposed honeytoken authentication mechanism extends the introduced BMFA method by providing more legitimacy and thus proving its applicability and efficacy in actual situations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.P., I.K. and L.M.; methodology, L.M. and I.K.; software, V.P. and I.K.; validation, L.M. and S.K.; formal analysis, I.K. and S.K.; investigation, V.P. and Y.Y.; resources, V.P. and Y.Y.; data curation, V.P. and Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, V.P. and I.K.; writing—review and editing, L.M. and S.K.; visualization, V.P. and Y.Y.; supervision, I.K. and L.M.; project administration, I.K. and L.M.; funding acquisition, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, D.; Wang, P. Two birds with one stone: Two-factor authentication with security beyond conventional bound. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2016, 15, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrunić, A.R. Honeytokens as active defense. In Proceedings of the 2015 38th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 25–29 May 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1313–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Papaspirou, V.; Maglaras, L.; Ferrag, M.A.; Kantzavelou, I.; Janicke, H.; Douligeris, C. A novel two-factor honeytoken authentication mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Wang, H. Secure, efficient, and weighted access control for cloud-assisted industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 16917–16927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspirou, V.; Kantzavelou, I.; Yigit, Y.; Maglaras, L.; Katsikas, S. A Blockchain-based Multi-Factor Honeytoken Dynamic Authentication Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Vienna, Austria, 30 July–2 August 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani, S.; Deters, R. Security, performance, and applications of smart contracts: A systematic survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 50759–50779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, M.N.M.; Khwaja, A.A.; Nadeem, A.; Ahmad, H.F.; Khan, M.K.; Hanif, M.A.; Song, H.; Alshamari, M.; Cao, Y. A survey on blockchain technology: Evolution, architecture and security. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 61048–61073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutiya, V.; Jhamb, S.; Priyadarshi, P.; Bhatia, A. Trustless two-factor authentication using smart contracts in blockchains. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 9–11 January 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.; He, Y.; Maglaras, L.; Yevseyeva, I.; Janicke, H. Evaluating information security core human error causes (IS-CHEC) technique in public sector and comparison with the private sector. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 127, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Sun, K.; Wang, Y.; Jing, J. TrustOTP: Transforming smartphones into secure one-time password tokens. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Denver, CO, USA, 12–16 October 2015; pp. 976–988. [Google Scholar]

- ALSaleem, B.O.; Alshoshan, A.I. Multi-factor authentication to systems login. In Proceedings of the 2021 National Computing Colleges Conference (NCCC), Taif, Saudi Arabia, 27–28 March 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.; Abayomi, A.; Gabriel, A.J. Multifactor IoT Authentication System for Smart Homes Using Visual Cryptography, Digital Memory, and Blockchain Technologies. In Blockchain Applications in the Smart Era; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kebande, V.R.; Awaysheh, F.M.; Ikuesan, R.A.; Alawadi, S.A.; Alshehri, M.D. A blockchain-based multi-factor authentication model for a cloud-enabled internet of vehicles. Sensors 2021, 21, 6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccafurri, F.; De Angelis, V.; Nardone, R. Securing mqtt by blockchain-based otp authentication. Sensors 2020, 20, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Multi-Factor Authentication Number Matching. 2022. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/authentication/how-to-mfa-number-match?tabs=iOS (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Putri, M.C.I.; Sukarno, P.; Wardana, A.A. Two factor authentication framework based on ethereum blockchain with dApp as token generation system instead of third-party on web application. Register 2020, 6, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercan, S.; Cebe, M.; Akkaya, K.; Zuluaga, J. Blockchain-Based Two-Factor Authentication for Credit Card Validation. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Data Privacy Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zheng, Z.; Cui, J.; Ngai, E.; Zheng, P.; Zhou, Y. Detecting ponzi schemes on ethereum: Towards healthier blockchain technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 1409–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, R.; Chan, Y.H.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, X.; Ngai, E.C. LiteChain: A lightweight blockchain for verifiable and scalable federated learning in massive edge networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 24, 1928–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanda, M.M.R.R.; Lacy, A.; Saxena, N. {SoK}: Inaccessible & Insecure: An Exposition of Authentication Challenges Faced by Blind and Visually Impaired Users in {State-of-the-Art} Academic Proposals. In Proceedings of the 34th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 25), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–15 August 2025; pp. 1393–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Papaspirou, V.; Papathanasaki, M.; Maglaras, L.; Kantzavelou, I.; Douligeris, C.; Ferrag, M.A.; Janicke, H. Security Revisited: Honeytokens meet Google Authenticator. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Ioannina, Greece, 23–25 September 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Otta, S.P.; Panda, S.; Gupta, M.; Hota, C. A systematic survey of multi-factor authentication for cloud infrastructure. Future Internet 2023, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.S. Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments. 2012. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/legacy/sp/nistspecialpublication800-30r1.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- SP 800-39; Managing Information Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View. National Institute of Standards & Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2011.

- Aponte-Novoa, F.A.; Orozco, A.L.S.; Villanueva-Polanco, R.; Wightman, P. The 51% attack on blockchains: A mining behavior study. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 140549–140564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, M.; McBurney, P. Sybil in the haystack: A comprehensive review of blockchain consensus mechanisms in search of strong Sybil attack resistance. Algorithms 2023, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.S.; Joshi, S.; Singh, D.; Kaur, M.; Lee, H.N. Systematic review of security vulnerabilities in ethereum blockchain smart contract. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 6605–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, N. Attacks on blockchain. In Advances in Computers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 121, pp. 399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, K.; Bhatt, C.; Shah, K.; Parmar, D.; Corchado, J.M.; Bruno, A.; Mazzeo, P.L. Machine-learning techniques for predicting phishing attacks in blockchain networks: A comparative study. Algorithms 2023, 16, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifah, A.; Ng, A.; Watters, P.A.; Kayes, A. A mechanism to detect and prevent ethereum blockchain smart contract reentrancy attacks. Front. Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 598780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solidity. Security Considerations: Reentrancy. 2022. Available online: https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/latest/security-considerations.html (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Alangot, B.; Reijsbergen, D.; Venugopalan, S.; Szalachowski, P.; Yeo, K.S. Decentralized and lightweight approach to detect eclipse attacks on proof of work blockchains. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2021, 18, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, K.; Agrawal, A.; Bhatia, A.; Tiwari, K. A novel classification of attacks on blockchain layers: Vulnerabilities, attacks, mitigations, and research directions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- binti Malik, M.; Zolkipli, M.F. Blockchain Threats: A Look into the Most Common Forms of Cryptocurrency Attacks. Borneo Int. J. 2023, 6, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Matulevičius, R. Exploring sybil and double-spending risks in blockchain systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 76153–76177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z. Security of cross-chain bridges: Attack surfaces, defenses, and open problems. In Proceedings of the 27th International Symposium on Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses, Padua, Italy, 30 September–2 October 2024; pp. 298–316. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, K.; Zhou, L.; Livshits, B.; Gervais, A. Attacking the defi ecosystem with flash loans for fun and profit. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Ahn, B.; Bere, G.; Ahmad, S.; Mantooth, H.A.; Kim, T. Blockchain-based man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack detection for photovoltaic systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Design Methodologies Conference (DMC), Virtually, 14–15 July 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, H.; Kim, J.; Jeong, Y.; Seok, B.; Gong, S.; Lee, C. A Security Analysis of Cryptocurrency Wallets against Password Brute-Force Attacks. Electronics 2024, 13, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razikin, K.; Soewito, B. Cybersecurity decision support model to designing information technology security system based on risk analysis and cybersecurity framework. Egypt. Inform. J. 2022, 23, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, A.; Kantzavelou, I. EtherVote: A Secure Smart Contract-based E-Voting System. Wirel. Netw 2025, 31, 1279–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).