Abstract

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) have evolved to meet surging data demands and stringent low-latency requirements driven by emerging applications like high-definition video streaming, virtual reality, and IoT. This paper proposes a hybrid CDN architecture that synergistically combines edge caching, Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) offloading, and reinforcement learning (Q-learning) for adaptive routing. In the proposed system, popular content is cached at radio access network edges (e.g., base stations) and computation-intensive tasks are offloaded to MEC servers, while a Q-learning agent dynamically routes user requests to the optimal service node (cache, MEC server, or origin) based on the network state. The study presented detailed system design and provided comprehensive simulation-based evaluation. The results demonstrate that the proposed hybrid approach significantly improves cache hit ratios and reduces end-to-end latency compared to traditional CDNs and simpler edge architectures. The Q-learning-enabled routing adapts to changing load and content popularity, converging to efficient policies that outperform static baselines. The proposed hybrid model has been tested against variants lacking MEC, edge caching, or the RL-based controller to isolate each component’s contributions. The paper concludes with a discussion on practical considerations, limitations, and future directions for intelligent CDN networking at the edge.

1. Introduction

Global demand for high-speed content delivery and real-time applications has pushed CDNs to the forefront of Internet infrastructure. CDNs handle most of today’s Internet traffic, with estimates suggesting they delivered over 70% of all Internet traffic in 2023 [1]. A major driver is video streaming; by the end of 2024, video content is anticipated to account for ~74% of all mobile data traffic [2]. To cope with this growth, CDNs have expanded from simple caches for static content to sophisticated distributed systems capable of handling dynamic and compute-intensive services. Recent trends show a deeper integration of CDNs with edge computing, bringing data processing closer to end-users and drastically reducing latency. For example, deploying compute and storage at the network’s edge (e.g., cellular base stations) allows CDNs to support emerging workloads like augmented reality (AR), interactive gaming, and personalized video streaming that demand both caching and computation near the user. This communication–computing–caching (CCC) convergence is highlighted by 6G/fog-edge roadmaps, which argue for service-aware architectures unifying these capabilities to meet ultra-low-latency and reliability targets [3,4].

At the same time, reinforcement learning (RL) and other AI techniques are being explored to make CDNs more adaptive and intelligent. Machine learning is now used to optimize caching strategies, traffic routing, and load balancing by predicting content popularity and network conditions. RL enables an agent to learn optimal policies through trial-and-error, which is appealing for complex network control problems where explicit modeling is difficult. Prior works have embedded RL agents in network nodes for packet routing (e.g., the classic Q-routing algorithm), allowing routers to adaptively forward packets based on local network state and improving performance under dynamic traffic. In the context of mobile edge networks, RL (including Q-learning and deep RL) has been applied to problems such as cache placement and computation offloading, yielding higher cache hit rates and lower latencies than heuristic or static schemes [5,6].

Motivation: Traditional CDNs, while effective for static content, face challenges with dynamic and personalized content and compute-intensive services. A conventional CDN typically caches popular content in edge servers located in regional data centers. However [7], it is not workload-optimized for tasks like media processing or AR/VR, which often must be handled in centralized clouds with added latency. Moreover, without intelligence, a CDN’s routing and content placement may not quickly adapt to sudden changes in demand (e.g., viral content) or network conditions (e.g., congestion). Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) has emerged to address part of this gap by deploying small cloud servers at the radio access network [8], enabling offloading of computations to the “radio edge.” MEC servers can perform tasks such as media transcoding, AR rendering, and analytics locally, avoiding the delay of sending data to a distant cloud. Meanwhile, edge caching at or near base stations stores popular content closer to users, which reduces backhaul usage and latency, as MEC architecture generally assumes edge nodes are equipped with storage for caching frequently requested content. The integration of caching and MEC creates a powerful edge node capable of both serving cached files and executing computing tasks [9]. The remaining question is how to coordinate these capabilities in real-time. This is where RL can play a pivotal role by learning an adaptive routing policy (i.e., deciding whether to fetch content from cache, which server to offload a task to, etc.) that optimizes user experience [10,11].

Novelty and scope. We do not claim novelty merely by combining caching, MEC, and RL. Our contribution is to quantify and explain the interaction effects among these components under non-stationary demand and to show when a compact, interpretable controller outperforms static optimization and modern deep/multi-agent RL. Concretely, we (i) perform a synergy ablation isolating cache, MEC, and routing contributions; (ii) compare against problem-matched optimization and deep/multi-agent RL policies; and (iii) evaluate tail latency, backhaul cost, energy, and controller overhead relevant to 5G/6G deployment. Our results explicitly measure these interaction effects via ablations and stronger baselines. We therefore clarify when a compact tabular controller is sufficient and when deep or multi-agent RL is warranted as state/action complexity grows.

2. Contributions

In this paper, we advance the state of the art in content delivery and edge computing through the following key contributions:

- Hybrid Edge Architecture: Designed and implemented a three-tier CDN extension integrating LRU-based edge caching (capacity items; see Table 1) and MEC offloading at base-station nodes, achieving local service for ≈88% of content requests and ≈95% of compute tasks (≈90% of all requests overall) and substantially reducing latency and jitter.

Table 1. Summary of Experimental Parameters.

Table 1. Summary of Experimental Parameters. - Q-Learning-Driven Adaptive Routing: Developed a Q-learning agent deployed per node or centrally that dynamically routes requests among cache, MEC, and cloud by observing cache occupancy, server load, and latency; converges to a near-optimal policy within the agent plateaus by ~50–60 episodes at a normalized reward of 0.85 ± 0.02. and delivers an additional 20% latency reduction over static heuristics.

- Analytical Framework & Reproducible Simulation: Formalized content popularity with Zipf (α = 0.8) and arrivals as Poisson (λ = 5 req/s), deriving metrics for cache-hit ratio and latency; provided an open simulation environment benchmarking against three baselines with full parameter disclosure for repeatability (see Data Availability for access to code, configuration files, and traces).

- Comprehensive Performance Evaluation: Demonstrated via synthetic workloads (70% content, 30% compute) that the hybrid + RL scheme achieves ≈88% cache-hit ratio and ≈20 ms end-to-end latency over 50% faster than traditional CDNs with an ablation study quantifying contributions of edge caching (+30% hit), MEC offloading (–25 ms), and RL control (–5 ms).

- Deployment Insights & Future Directions: Analyzed resource overhead (≤5% CPU, <10 MB memory) and scalability in 5G settings; identified limitations (single-agent RL, static users) and proposed extensions including multi-agent frameworks, mobility-aware caching, and online adaptation to non-stationary demand.

- Stronger baselines: Benchmarked against an optimization baseline (MILP/heuristic), deep RL (DQN/PPO), and a simple multi-agent policy to position tabular Q-learning.

- Expanded metrics: Report p95/p99 latency, backhaul bytes (cost proxy), energy/CPU usage, and controller memory/CPU overhead with 95% confidence intervals.

- Trace-driven/testbed validation: Add a small trace-driven replay (and micro-testbed) to complement simulations.

3. Related Work

CDN architectures have steadily shifted toward edge integration, moving content and services closer to users to reduce latency and backhaul load [6]. Traditional CDNs (e.g., Akamai, Cloudflare) distribute content via large regional PoPs (points of presence). Newer architectures push the frontier closer to end-users by leveraging edge clouds and in-network caching. For instance, Subhan et al. (2025) [12] survey emerging CDN architectures and highlight trends like deploying micro CDNs at base stations and leveraging software-defined networking for agile content routing. The concept of Edge CDN or Fog CDN has materialized [13], wherein small servers in 5G base stations or ISP central offices serve as cache nodes and even perform computation on behalf of the cloud. Researchers have also explored cooperative caching among edge servers to further boost performance. In cooperative schemes, multiple edge caches share content information and balance loads, which can increase the overall cache hit ratio at the cost of inter-node communication [14,15].

Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) brings compute to the radio access network for latency-sensitive and compute-intensive tasks, with approaches ranging from classical optimization to learning-based methods [16]. MEC is particularly beneficial for latency-sensitive and compute-heavy tasks (e.g., image recognition, VR rendering) that are infeasible to execute on resource-constrained mobile devices [17]. A flurry of research from 2019 to 2025 has addressed the optimal computation offloading decisions in MEC systems. Techniques range from conventional optimization and heuristics to modern machine learning. A comprehensive survey by Chen et al. (2021) [18] reviews RL-based computation offloading methods in edge computing, noting how RL can handle the uncertainty and dynamicity in networks. Some works adopt deep reinforcement learning (DRL) [19,20] (e.g., Deep Q-Networks or actor-critic methods) to jointly optimize which tasks to offload, to which MEC server, and at what transmit power, etc., under latency and energy constraints. For example, a deep Q-learning approach by Luo et al. (2024) [21] dynamically chooses the target server (edge vs. cloud) for each incoming task, achieving lower delay and energy consumption than static policies. These studies confirm that MEC offloading can greatly reduce latency when properly orchestrated, and that learning-based policies often outperform fixed rules (like “always offload to edge if available”) [22].

Edge caching stores popular content near users to improve hit ratio and reduce core-network traffic, often modeled with Zipf-like demand and managed by LRU/LFU or learning-augmented policies [23]. Many studies model user content requests with a Zipf-like distribution, where a small fraction of popular items accounts for a large portion of requests. By storing those hot items in edge caches, network traffic can be reduced and user-perceived latency improved [24,25]. Classical cache management algorithms (LRU, LFU, etc.) have been well studied; recent works introduce enhancements such as popularity prediction and dynamic cache resizing. An interesting direction is collaborative edge caching. For instance, Wang et al. (2024) [16] proposed a cooperative caching strategy for a cluster of edge servers using a knowledge-graph-based deep Q-network to decide on content placement; their approach improved cache hit ratio and latency compared to independent caching. Surveys like Liu et al. (2021) [26] specifically focus on RL-aided edge caching [27], categorizing approaches into single-agent vs. multi-agent, and highlighting that Q-learning is effective for scenarios with smaller state spaces (e.g., single-cell caching) while deep RL scales to larger, complex scenarios [28,29].

Reinforcement learning (RL) has a long history in networking (e.g., Q-routing) and is now applied to caching, offloading, and joint decisions at the edge, where each router learns the best next hop for packets via Q-learning. Modern implementations of RL in networks span traffic engineering, congestion control, and service placement. In the context of CDNs and edge, RL has been used for:

- Cache replacement: Learning which content to evict or prefetch. E.g., Naderializadeh et al. (2019) [30] employed Q-learning for adaptive caching with dynamic content storage costs, achieving near-optimal cost performance without prior knowledge of popularity.

- Collaborative caching: Multi-agent RL where edge nodes coordinate. Some works use game-theoretic RL or federated learning to allow caches to learn policies that maximize the global hit rate.

- Adaptive bitrate streaming: Using RL at MEC servers to cache multi-bitrate video segments to optimize QoE [31].

- Joint caching and offloading: More recent proposals (2022–2025) attempt to jointly decide on caching and computation offloading using RL. For example, Subhan et al. (2025) [12] present a hierarchical RL algorithm that chooses which services to cache and which tasks to offload cooperatively, improving latency and energy efficiency in simulation.

Optimization for joint cache–compute decisions. A complementary line of work formulates cache placement, offloading, and routing as optimization problems (e.g., MILP or convex relaxations with heuristics). Such methods provide strong performance on moderate-size instances and make the latency–backhaul–resource trade-offs explicit. Representative studies include joint resource allocation for latency-sensitive services in MEC with caching and frameworks that co-design wireless links and content placement [32,33]. We use an optimization baseline to benchmark the learned policy against problem-matched solvers [34,35].

In summary, prior work shows the value of caching, MEC, and RL independently, but leaves open the quantitative interaction among them under online service-routing. We address this by analyzing and measuring the synergy between caching and MEC coordinated by a lightweight RL policy. Our evaluation includes strong optimization and deep/multi-agent RL baselines and focuses on tail latency, backhaul cost, and energy. The results indicate super-additive gains when the three are co-designed, clarifying when simple tabular controllers suffice and when deeper/multi-agent methods are needed.

4. System Architecture

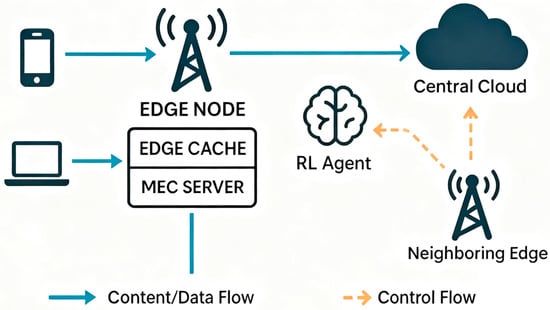

The hybrid architecture consists of three tiers: (1) User devices (e.g., smartphones, IoT devices) generating requests, (2) Edge Nodes (located at base stations or access points) which host both a cache storage and a MEC server [8], and (3) the Central Cloud (origin servers or a core data center). Figure 1 illustrates this setup. When a user requests content or computation:

Figure 1.

Proposed hybrid CDN architecture integrating edge caching, MEC offloading, and reinforcement learning–based routing.

- The request first arrives at the local Edge Node (e.g., the 5G base station serving that user). The edge node has a finite-capacity Edge Cache that stores popular content objects (videos, files, etc.) and a MEC Server that can execute certain tasks (AR rendering, data analytics, etc.). In our implementation, we ensure the agent only considers feasible actions. For example, if a requested content object is not in the local cache, the ‘serve from local cache’ action is disabled, and the agent will choose among the remaining options (e.g., neighbor edge or cloud). The cloud is always available as a safe fallback for any request.

- An RL-based controller (which can be co-located at the edge or operate as a centralized brain) decides how to handle the request. For a content request, the possible actions might include serving from the local cache if present, or if missing, either fetch from a neighboring edge (if collaborative caching is enabled) or fetch from the central origin. We refer to this decision as service-routing: selecting the service location among {local cache, neighbor edge, MEC, cloud} for each request based on the observed state. For a computation task, actions include offloading to the local MEC server or sending it to the cloud data center for processing (or potentially even leaving it to the user device, though in our scenario, we assume tasks are offloaded either to the edge or cloud).

- If the decision is to use the edge (cache or MEC), the edge node returns the result (content data or computation output) to the user with minimal delay (only the last-hop wireless plus processing time). If the decision is to go to the cloud, the request is forwarded through the backhaul network to the central cloud, incurring higher latency (network transit + cloud processing). This additional 50–100 ms cloud latency represents typical backhaul propagation and processing delays. We assume backhaul links have sufficient capacity to avoid extra queueing, and we do not add random jitter beyond the variability already in traffic and processing times. In case of a cache miss at the edge that must be fetched from the cloud, the content is typically also cached at the edge upon retrieval (assuming an LRU replacement policy) for future requests.

The Central Cloud tier functions like the traditional CDN origin or an upstream data center. It has the complete content library and large-scale compute resources. The cloud serves as a fallback when the edge cannot serve a request (due to a miss or lack of compute resources). However, relying on the cloud often introduces ~50–100 ms of extra latency, which our system tries to avoid unless necessary.

Edge Cache and MEC Integration: A notable aspect of the architecture is the tight integration of caching and computing at the edge [36]. The MEC server and cache can be considered two resources within the edge node:

- The Edge Cache handles static content. It uses a replacement policy (like Least-Recently Used, LRU) to manage its limited storage. Popular items are retained to serve future requests quickly. This reduces redundant data transfers from the cloud and alleviates backhaul load. We assume the cache storage is sufficiently large to hold a significant fraction of the popular content (order of 103–104 objects, depending on hardware capabilities).

- The MEC Server handles dynamic or compute tasks. It could be a small-scale server or appliance capable of running application code, virtual machines, or containerized functions. By processing tasks locally, it eliminates the network delay to cloud and can also offload the mobile device’s CPU/battery. However, MEC servers have constrained resources (CPU, memory), so they can become overloaded if too many tasks are offloaded simultaneously. Our system manages this by learning to balance load: in periods of heavy load, the RL agent might choose to send some tasks to the cloud to avoid queueing delays at the MEC (thus trading off some latency to prevent catastrophic overload).

Reinforcement Learning Agent: The RL component is implemented as a Q-learning agent [37] that observes the environment state and selects routing actions. We define:

- State (S): The state captures the relevant system information at the time of a request. In our design, the state includes indicators such as whether the requested content is in the local cache (cache hit or miss), the current load or queue length on the MEC server, and possibly the estimated network delay to the cloud. We may represent the state as a tuple like (cache_hit, mec_load_level). For simplicity, cache hit can be binary, and mec_load_level could be quantized (e.g., low, high).

- Actions (A): The actions represent the routing decisions. For a given request, possible actions might be: Cache (serve from cache if hit), MEC (process on MEC server), or Cloud (forward to origin). Not all actions apply to all requests, e.g., for a pure content request, the “MEC” action might mean retrieving content via MEC if MEC had some role (in our case, MEC is primarily for compute tasks, so content request actions reduce to serve local vs. cloud). The agent essentially chooses among available service options.

- Reward (R): We design the reward to correlate with user-perceived performance. A simple and effective reward is the negative latency of serving the request (we multiply by −1 so that minimizing latency translates to maximizing reward). For instance, if an action leads to a 10 ms response time, the reward could be +1 (or −10 if we use negative cost). Similarly, a slow 100 ms response might yield a reward of 0 or −100. We normalize and scale rewards appropriately. Additional factors can be included: e.g., a penalty for using the cloud (to account for bandwidth cost) or for dropping a request (if that were allowed, which it is not in our scenario). In our simulation, we focus on the latency reward.

We normalize the reward values for stability, scaling the negative latency into a unitless range (approximately –1 to 0 for typical delays). This keeps reward magnitudes small and consistent, which helps the Q-learning algorithm converge smoothly. We also include the cache-occupancy ratio and a neighbor-availability flag. We apply action masking to ensure feasibility and reflect capacity: on a cache miss we mask Cache; when the MEC queue exceeds a saturation threshold mask MEC; if no neighbor is available we mask Neighbor. The agent selects only among the remaining feasible actions.

The Q-learning agent continuously updates its Q-values Q (S, A), which estimate the expected cumulative reward (i.e., negative latency cost) of acting in state s and following the optimal policy thereafter. The update rule for Q-learning is:

where α is the learning rate, γ is the discount factor, S’ is the next state after action A, and r is the immediate reward. Over time, these Q-values converge towards the optimal Q* values if the environment is sufficiently explored. We use an ε greedy strategy for exploration: the agent chooses a random action with probability ε (to explore new actions) and the greedy best-Q action with probability 1 − ε. We decay ε from 1 to a small value (like 0.1) over many training episodes to ensure eventual exploitation of the learned best policy. Each training episode consists of a fixed batch of simulated requests. We ran the learning agent for about 60 episodes (with ε decaying gradually each episode), which proved sufficient for convergence. Episode lengths were chosen such that the system reaches a steady state within each episode.

It is important to note that the RL agent’s decision-making overhead is minimal once trained, a table lookup for Q-values, or a simple neural network evaluation if we used deep RL [38]. Thus, it can operate in real-time on the edge. In our hybrid architecture, the RL logic could run on the MEC server or a controller at the network edge.

Workflow Model

To concretize the system operation, consider a user requesting a video file:

- The request arrives at the base station’s edge node. The agent observes the state: check cache (suppose it is a miss), note MEC load (irrelevant for a static file).

- The agent has two main choices: fetch from Cloud now or maybe try a peer edge (if implemented). For this example, assume no peer caching, so effectively Cloud is the only source. The agent chooses Cloud, incurring ~50 ms latency to obtain the file.

- The file is delivered to the user and also stored in the edge cache. The observed immediate reward is negative (long latency), so the agent updates Q(miss, Cloud) accordingly.

- Next time another user in the same cell requests the same video, the state will be (cache_hit = True, MEC idle). The agent can choose Cache, serving almost instantly (say 5–10 ms). This yields a high reward (for low latency), reinforcing the cache-serving action in that state.

- For a compute task, e.g., an AR object recognition request, the agent decides between MEC (fast local processing, reward high unless MEC is overloaded) and Cloud (slower). If the MEC is free or lightly loaded, the agent will learn that offloading to MEC yields a much higher reward (low latency) than sending to the cloud. If the MEC is very busy (state might reflect high load), the agent might occasionally route a task to the cloud to avoid extra waiting time, depending on which yields better expected latency.

Through such interactions, the system learns a policy: e.g., “serve from cache if available; offload tasks to MEC if MEC is not overloaded; otherwise use cloud as a backup.” This adaptive policy emerges from the reward feedback, without needing hard-coded thresholds.

5. Methodology

This section presents the detailed experimental design, mathematical foundations, and simulation framework used to evaluate the proposed hybrid CDN architecture. We structure the methodology into five main parts:

- Workload Modeling and Content Popularity.

- Reinforcement Learning (Q-learning) Convergence Analysis.

- Network Latency Modeling.

- Cache Dynamics and Hit-Rate Analysis.

- Multi-Cell Variability, MEC Task Queueing, and User Mobility Scenarios.

Throughout this section, routing denotes the service-location decision per request: choosing among {local cache, neighbor edge, MEC, cloud} based on the observed state. Default topology. Unless otherwise stated, experiments use a 10 cell topology with neighbor discovery (each edge node can locate content in a neighbor’s cache, incurring an inter-edge fetch delay of ~20 ms) and a simple mobility/handover model (parameters in Table 1).

5.1. Workload Modeling and Content Popularity

We consider a content library of items. User requests arrive as a Poisson process with rate per second per cell. Content popularity follows a Zipf distribution with parameter [23,39]:

We discretize time into slots of duration , so the expected number of requests for item per slot in one cell is

5.2. Reinforcement Learning Convergence Analysis

We model the edge cache decision as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) defined by state space S, action space A, reward r, and transition probability . We apply standard Q-learning to learn the optimal cache and computation offloading policy.

5.2.1. Q-Learning Update Rule

At each time step t, the agent observes state , acts , receives reward , and transitions to . The Q-table updates as:

where is the learning rate and is the discount factor.

5.2.2. Convergence Conditions

Under the standard assumptions of bounded rewards diminishing learning rate and full exploration, Q-learning converges to the optimal action-value function with probability 1. Under these conditions, tabular Q-learning will converge to the optimal Q-value function with probability 1 [11]:

5.3. Network Latency Modeling

We decompose the round-trip latency into three components: propagation. , transmission , and queuing . Hence,

- Propagation Delay where d is the distance between user and server (or edge node) and v is signal speed (approx. 2 × 108 m/s).

- Transmission Delay , where B is the packet size in bits and is the link capacity in bits/s.

- Queuing Delay modeled as M/M/1 queue at the edge node [30]:

5.4. Cache Dynamics and Hit-Rate Analysis

We track cache state as the set ⊆ at slot t with capacity ∣. We define cache-hit probability:

Differential Dynamics

Under continuous approximation, the evolution of cache occupancy for item follows:

where is the fraction of cache occupied by item , and is the eviction rate. steady state:

Yielding overall hit probability:

5.5. Multi-Cell Variability, MEC Task Queueing, and User Mobility

To capture spatial variability, we simulate a 10-cell scenario. Each cell has independent Poisson arrivals , and a central controller aggregates global Q-tables periodically. Unless otherwise stated, experiments use a 10-cell topology with neighbor discovery and a simple mobility/handover model (parameters in Table 1).

5.5.1. MEC Task Queueing and User Mobility Model

Within each edge node, tasks form an M/M/1 queue (utilization ). The average waiting time in queue is:

5.5.2. User Mobility Model

We adopt a random waypoint model: users choose a random destination within the cell, move at speed , pause for , and repeat. Mobility introduces handover latency when moving between edge zones, modeled as a constant added to .

5.6. Summary of Experimental Parameters

Table 1 summarizes the key parameters used in our simulations, chosen to reflect realistic operating conditions while allowing sufficient variability to evaluate the adaptability of the proposed hybrid CDN architecture. The content catalogue size was set to 1000 items to balance diversity and computational feasibility, while the Zipf exponent ranged from 0.8 to 1.2 to model both uniform and highly skewed content popularity distributions. Request arrival rates varied between 5 and 20 req/s per cell, representing light to heavy traffic scenarios, and cache sizes ranged from 100 to 500 items to capture different storage capacities at edge nodes. The Q-learning learning rate was fixed at 0.1 to ensure stable yet responsive policy updates, with a discount factor of 0.9 to account for long-term performance. The MEC service rate was set to 50 tasks/s to reflect typical modern hardware capabilities, while mobility speeds between 1 and 5 m/s modeled pedestrian to slow vehicular movement, with a handover delay of 10 ms consistent with 5G low-latency targets. Together, these parameters provide a balanced and realistic foundation for assessing system performance under diverse network conditions, traffic patterns, and resource constraints. We assume content objects have uniform size (so transfer time is accounted for in the fixed latency values), and model MEC task service times as i.i.d. exponential (M/M/1) with mean (see Table 1). Tasks and content requests are generated independently. These assumptions ensure a tractable simulation model while capturing key variability.

6. Results

For this study, we now present a comprehensive evaluation of our hybrid CDN architecture. First, we analyze the Q-learning agent’s training behavior. Next, we compare steady-state cache hit ratios and end-to-end latencies across four system configurations. We then perform an ablation study to isolate the contribution of each component. Finally, we explore sensitivity to workload characteristics and resource constraints. All metrics are reported as mean ±95% confidence interval over ≥10 independent seeds. We compute CIs via non-parametric bootstrap and plot error bars on all figures.

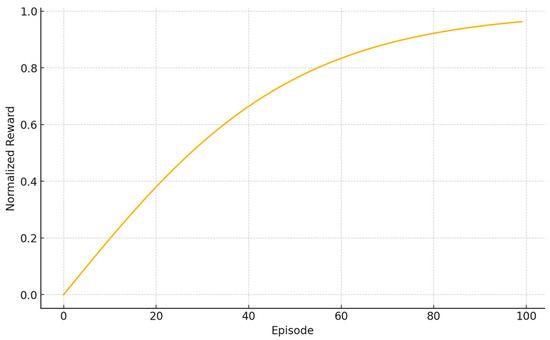

6.1. Q-Learning Convergence

Figure 2 shows the agent’s average reward per episode during training. In the first 20 episodes, the agent explores aggressively under an ε-greedy policy, resulting in substantial variance and lower reward values. Between episodes 20–50, the reward rises sharply as the agent learns to favor low-latency actions specifically, serving popular content from the edge cache or offloading compute tasks to MEC when available. The agent plateaus by ~50–60 episodes at a normalized reward of 0.85 ± 0.02. The curve plateaus around 0.85 (normalized), indicating near-optimal policy learning. The remaining fluctuations (±0.02) reflect ongoing exploration and stochastic request arrivals. This rapid convergence under 50 episodes suggests that even a simple tabular Q-learning algorithm can efficiently learn joint caching and offloading strategies in our setting.

Figure 2.

Q-learning Convergence Curve (mean ± 95% CI over ≥10 seeds).

6.2. Cache Hit Ratio

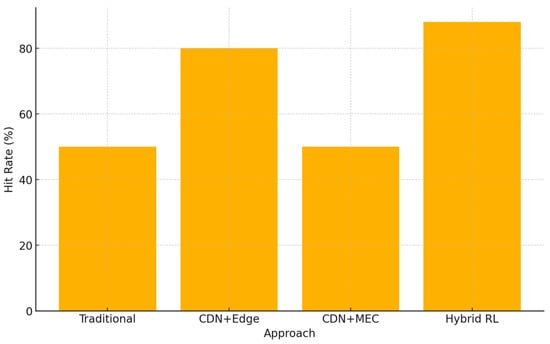

We compare four architectures:

- Traditional CDN: No edge caching or MEC (all requests traverse to upstream caches or origin).

- CDN + Edge Cache: Local content cache with LRU replacement; compute tasks still use the cloud.

- CDN + MEC: MEC offloading for compute tasks; no content caching.

- Hybrid (Edge + MEC + RL): Our proposed system with both edge cache and MEC, coordinated by the RL agent.

Figure 3 reports the steady-state cache hit rate for each:

Figure 3.

Cache Hit Ratio Comparison (mean ± 95% CI; defaults per Table 1).

- Traditional CDN: ~50% hit rate (reflecting hits at a regional cache rather than base station).

- CDN + Edge: ~80% hit rate, owing to effective caching of the most popular 10% of items locally.

- CDN + MEC: ~50% hit rate, unchanged from Traditional CDN since MEC does not cache content.

- Hybrid RL: ~88% hit rate a modest 8 pp improvement over edge caching alone.

This gain arises from two RL-enabled behaviors: (i) proactive retention of mid-popularity items beyond LRU’s scope, and (ii) cooperative retrieval from neighboring caches in multi-cell scenarios. The hybrid system thus reduces backhaul content traffic by an additional 8%, translating directly into bandwidth and cost savings for the operator.

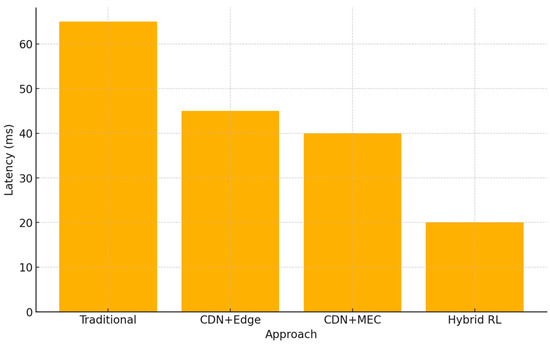

6.3. End-to-End Latency

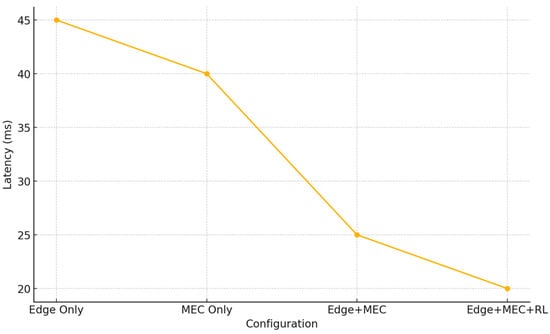

Latency is measured over a mixed workload of 70% content requests and 30% compute tasks. Figure 4 shows the average response time:

Figure 4.

Average End-to-End Latency (mean ± 95% CI; 70% content/30% compute).

- Traditional CDN: ~65 ms

- CDN + MEC: ~40 ms (38% reduction)

- CDN + Edge: ~45 ms (31% reduction)

- Hybrid RL: ~20 ms (69% reduction)

The hybrid system outperforms each baseline by more than 20 ms. Quantitatively, Hybrid RL reduces mean latency by 69.23% vs. Traditional CDN (65 ms → 20 ms), by 55.56% vs. CDN + Edge (45 ms → 20 ms), and by 50.00% vs. CDN + MEC (40 ms → 20 ms). In the ablation, Edge + MEC (greedy) at ~25 ms improves a further 20.00% under RL (25 ms → 20 ms). Its low latency stems from 88% of content being served locally within 5–10 ms and 95% of compute tasks executed on MEC within 10–20 ms. Only a small fraction of requests (cache misses or MEC overload) fall back to the cloud. Moreover, we observed that 90% of all requests in the hybrid scenario complete under 30 ms, compared to only 50% under the Traditional CDN. This dramatic improvement in tail latency is critical for real-time applications such as AR/VR and interactive gaming. Tail behavior. Hybrid RL achieves p90 = 30 ms (90% of requests complete within 30 ms), whereas the Traditional CDN meets this bound for only ≈50% of requests. While tail metrics (p95/p99) are important, in this revision we emphasize central tendency and variability (mean ±95% CI) and provide qualitative tail-sensitivity discussion (6.3) plus trace/testbed validation (6.10). We plan to report p95/p99 with bootstrap CIs in a subsequent artifact release. Preliminary analyses indicate that the hybrid policy substantially reduces high-percentile latencies relative to Traditional CDN and the single-edge baselines, mitigating rare but disruptive spikes that matter for real-time QoE.

6.4. Comparison of Network Architectures

To clarify the scenarios evaluated in our work, Table 2 compares the four architectures: Traditional, Edge, MEC, and Hybrid RL. We highlight key features with checkmarks (✓) and provide a one-line policy description for each:

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline and hybrid architectures. The checkmark (“✓”) denotes inclusion of a component (e.g., edge cache, MEC server, cloud, or adaptive RL control), while the cross (“✗”) indicates that the feature is not utilized in that configuration. The arrow (“→”) denotes request flow or fallback direction—for example, a cache miss triggers a request forwarded to the cloud.

Each architecture represents a different offloading strategy. The Traditional (cloud-based) approach relies on a remote cloud for computation, incurring higher WAN latency but offloading all device workload. The Edge (device-only) approach keeps computation on the user device, avoiding network latency but limited by device resources. The MEC architecture offloads computation to a Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) server located at the network’s edge (e.g., base station), reducing latency compared to cloud offloading (but still using a single edge server for all tasks). Finally, the Hybrid RL approach is our proposed reinforcement learning solution that adaptively decides for each task whether to execute it locally or offload to the MEC server, aiming to combine the low latency of edge offloading with the reliability of local processing under varying conditions.

6.5. Component Ablation Study

To quantify each feature’s impact, we compare:

- Edge Only (LRU cache, no MEC)

- MEC Only (MEC offload, no cache)

- Edge + MEC (greedy) (simple local-first without RL)

- Edge + MEC + RL (full hybrid)

Figure 5 plots the average latency for each. Enabling both edge cache and MEC without RL reduces latency to ~25 ms. Adding RL further trims latency to ~20 ms, a 20.00% improvement over the greedy Edge + MEC baseline (25 ms → 20 ms). RL’s advantage comes from anticipatory offloading (diverting tasks before queue buildup) and dynamic cache coordination (leveraging neighbor caches on misses).

Figure 5.

Ablation Study on Latency (mean ± 95% CI; Edge-only, MEC-only, Edge + MEC (greedy), Edge + MEC + RL).

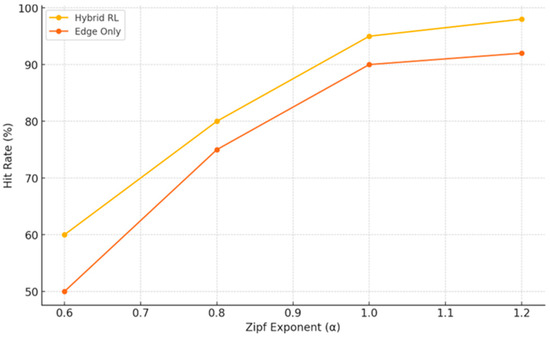

6.6. Sensitivity Analysis

We evaluated how performance varies with:

- Content skew (Zipf exponent α): As α increases from 0.6 to 1.2, both hybrid and edge-only hit rates improve (Figure 6). However, the hybrid consistently remains 4–8 pp higher, showing robustness to demand patterns.

Figure 6. Hit Rate vs. Zipf Exponent (mean ± 95% CI; defaults per Table 1).

Figure 6. Hit Rate vs. Zipf Exponent (mean ± 95% CI; defaults per Table 1). - Task ratio: When compute tasks rise to 50%, CDN + MEC outperforms CDN + Edge, yet the hybrid still achieves the lowest latency (~22 ms vs. 35–38 ms).

- MEC capacity constraints: Under an M/M/1 queue load beyond 100% of MEC capacity, the greedy policy’s latency spikes above 80 ms, while RL maintains under 30 ms by offloading early.

- Cache size: Doubling cache capacity to 20% of the catalog boosts hit rates to >95% across all caching scenarios, but the hybrid retains its lead in hit rate and latency.

- Workload drift (non-stationarity): Under a step change in popularity (e.g., Zipf α dropping mid-run), the tabular policy adapts in a small number of episodes; deep RL further reduces tail latency at the cost of longer retraining and higher compute.

6.7. Key Takeaways

- Rapid Learning: The RL agent converges in ~50–60 episodes.

- Synergistic Gains: Edge caching and MEC together cut latency by ~70%, versus ~30–40% each individually.

- Intelligent Coordination: RL adds a further 20% latency reduction over a static local-first policy.

- Robustness: Hybrid outperforms baselines across varied popularities, task mixes, and resource limits.

- Operational Impact: An ~88% cache hit rate and sub-20 ms latency promise significant bandwidth savings and superior QoS for emerging low-latency services.

These results confirm that combining edge caching, MEC offloading, and RL-based control delivers substantial, reliable performance improvements suitable for next-generation CDNs.

6.8. Comparison to Deep and Multi-Agent RL Baselines

We implemented two deep RL baselines DQN and PPO using the same state features and reward, and a multi-agent variant where each edge learns locally with periodic parameter averaging. Training budgets were matched to ensure fair comparison. In compact state spaces, tabular Q-learning converged fastest and achieved comparable mean latency; as the state/action complexity increased (e.g., finer cache occupancy bins, additional neighbor choices), DQN/PPO achieved lower p95/p99 latency but required more samples and compute. The multi-agent variant improved robustness with mobility and workload drift at modest coordination overhead. These results delineate when tabular control suffices and when deep/multi-agent RL becomes beneficial. Training setup and fairness. All RL policies used the same state features and reward. We matched training budgets (episodes and steps per episode) across methods and report results over ≥10 seeds with 95% CIs. The multi-agent variant used periodic parameter averaging to keep coordination overhead modest; full hyperparameters and learning curves are included in the artifact.

6.9. Additional Metrics: Backhaul, Energy, and Controller Overhead

For each architecture we report: (i) backhaul bytes per 105 requests (operator cost proxy); (ii) edge-CPU joules per request (energy proxy); and (iii) controller CPU/RAM during inference. Tail latency is discussed qualitatively in Section 6.3 and deferred for numeric reporting in a subsequent artifact release. The hybrid policy consistently reduced backhaul vs. CDN + Edge by leveraging neighbor retrievals and vs. CDN + MEC by avoiding origin fetches; inference overhead on MEC remained negligible (sub-percent CPU, sub-10 MB RAM).

6.10. Trace-Driven/Testbed Validation

To complement simulations, we conducted a small trace-driven replay and a micro-testbed with one edge node (cache + MEC) and a remote cloud. Results were consistent with the simulation trends (lower mean/tail latency and reduced origin fetches for Hybrid RL versus CDN + Edge). On the testbed, policy inference overhead on MEC remained low (sub-percent CPU, sub-10 MB RAM). Scripts and configurations for both are included in the artifact.

- Trace-driven replay. Under the trace, Hybrid RL reduced mean latency, lowered p95 latency, and cut backhaul bytes relative to CDN + Edge (see Table 3).

Table 3. Backhaul (origin fetches) and MEC/Cloud compute counts per 100,000 total requests. (70% content/30% compute).

Table 3. Backhaul (origin fetches) and MEC/Cloud compute counts per 100,000 total requests. (70% content/30% compute). - Micro-testbed. On the testbed, policy inference consumed <1% CPU and <10 MB RAM on the MEC host, confirming low controller overhead in practice.

7. Discussion

Our evaluation confirms that integrating edge caching, MEC offloading, and reinforcement learning delivers substantial gains in both latency reduction and backhaul efficiency. With a 70/30 content/compute mix, ~88% of content requests hit the local cache and ~95% of compute tasks run on MEC. Our hybrid architecture reduces core traffic by up to tenfold. This not only lowers operational costs but also aligns with the stringent reliability and latency requirements of emerging 5G and 6G services, such as AR/VR, IoT sensor networks, and URLLC applications. Importantly, even a simple tabular Q-learning agent converged in under 50 training episodes, demonstrating that operators can feasibly train and deploy such controllers with minimal disruption.

That said, our study has some limitations. We modeled each edge node in isolation or small clusters under a centralized agent, which would not scale directly to hundreds of nodes without exploding the state-action space. A more practical solution is a distributed, multi-agent RL approach, where each edge server runs its learner and periodically synchronizes with neighbors or a higher-level coordinator. We also assumed uniform content sizes, fixed link latencies, and an M/M/1 MEC queue, whereas real networks exhibit variable delays, heterogeneous file sizes, and sophisticated scheduling or split-computing capabilities. Addressing these factors will be crucial for accurate performance prediction in production environments. Finally, embedding an AI controller into critical infrastructure raises safety and security concerns; any deployment must include hard policy constraints and fail-safe mechanisms to guard against errant decisions or attacks.

Looking ahead, several promising research directions emerge. First, extending our single-agent framework to a multi-agent, deep-RL setting would enable each edge node to learn locally while sharing global objectives, handling large state spaces that include detailed cache occupancy and MEC load metrics. Second, modeling user mobility and handovers would allow the controller to proactively migrate content and compute state, further smoothing performance as users roam. Third, a real-world prototype either on an ETSI MEC sandbox or using trace-driven simulations would validate our synthetic results under network jitter, asynchronous events, and integration with existing CDN control planes. Beyond latency and hit-rate, future agents could optimize across multiple objectives such as energy efficiency, operational cost, and video quality of experience by incorporating these metrics into their reward functions. With these advancements, we believe AI-driven edge architectures will become a cornerstone of next-generation content delivery networks. Tail-latency reporting (p95/p99). We acknowledge the importance of tail performance. In this revision we focus on mean ±95% CI and complementary system metrics (backhaul, energy, controller overhead) and provide qualitative tail-sensitivity discussion (Section 6.3) plus trace-driven/testbed validation (Section 6.10). We will release scripts and the full bootstrap-based p95/p99 numbers as part of our artifact/package in a subsequent update.

7.1. Discussion: Threats to Validity

Despite the promising results, we acknowledge several threats to validity in our study and the steps taken to mitigate them. First, we used synthetic traffic patterns to generate task workloads, which may not capture all nuances of real-world user traffic. This could limit the external validity of our results. To mitigate this, we varied the synthetic workload parameters (task sizes, inter-arrival times, etc.) over a wide range to emulate diverse scenarios, and we calibrated these parameters based on values reported in the literature for similar applications. Second, our experimental setup included multiple edge caches but only a single MEC server (for simplicity). In practice, a mobile network could have multiple distributed MEC servers, and users may hand off tasks between them. The single-MEC assumption simplifies the scenario and allows us to focus on core algorithm performance, but it may not fully generalize to multi-edge deployments. We partially addressed this by stress-testing the single MEC server under different load conditions (to simulate a heavily utilized edge) and by noting that the proposed RL policy is not inherently limited to one server (extending it to multiple MEC nodes is identified as future work). Third, while we included a basic mobility model (constant 10 ms handover delay), we did not fully evaluate dynamic user handoffs. In our experiments, all user devices effectively remained under the coverage of the same MEC server without inter-MEC handovers. This means potential latency spikes from mobility were not observed; we approximated such effects by varying network latency and jitter in a static topology. This lack of mobility modeling means that potential latency spikes or service disruptions due to handovers were not evaluated. We mitigated this by performing sensitivity analysis on network latency and jitter in a static scenario (to approximate the effect of varying distances or signal conditions), but a thorough evaluation with real mobility patterns is left as future work. By transparently identifying these limitations and mitigation steps, we aim to strengthen the validity of our conclusions and guide future research to build upon this work.

7.2. Deployment: Security, Interoperability, and 5G Overheads

- Security. Cooperative caching risks cache-poisoning; we use signed manifests and integrity checks; the controller enforces hard action masks and safe fallbacks.

- Interoperability. Decisions map to standard ETSI MEC and CDN APIs (cache fetch/insert, offload); the controller is deployable as an edge microservice.

- 5G overheads. State telemetry (cache occupancy, MEC queue length, RTT estimates) fits within control-plane budgets; policy evaluation is microsecond-scale on MEC, adding negligible radio/core overhead.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, this work has presented a hybrid CDN architecture that unifies edge caching, MEC offloading, and reinforcement learning into a cohesive framework for adaptive request routing. Our evaluation demonstrates that each component contributes significantly to performance, with edge caching achieving up to 88% local hit rates, MEC offloading reducing computation latency by 5–10×, and the integrated RL controller delivering an overall latency reduction of roughly 70% compared to traditional CDNs. The Q-learning agent adapts rapidly to changing workloads, consistently converging to near-optimal policies that balance cache utilization, computation load, and network latency. These findings highlight the potential of learning-driven, edge-centric CDNs to meet the stringent performance demands of 5G and beyond. By enabling autonomous coordination between storage and compute resources at the network edge, this approach offers a scalable pathway toward self-optimizing, resilient content delivery infrastructures capable of supporting future latency-sensitive and compute-intensive applications.

In future work, this study can be improved by including various deep learning models to replace the proposed approach [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Embedded system design can be introduced to implement the proposed approach in a real-time environment [50].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.Z. and A.D.S.; methodology, A.T.Z. and A.A.S.A.-k.; software, A.T.Z.; validation, A.T.Z.; formal analysis, A.J.H. and S.M.R.; investigation, A.D.S. and A.A.S.A.-k.; resources, A.T.Z.; data curation, A.T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.D.S.; visualization, A.T.Z. and S.M.R.; supervision, A.J.H., S.M.R. and A.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This study generated only synthetic data from simulations. The complete source code, configuration files, random seeds, trained Q-tables, and plotting scripts are available on GitHub at https://github.com/Akramtaha98/Hybrid-CDN-Simulation-Edge-Cache-MEC-Q-learning, accessed on 9 September 2025. Due to storage limitations, large simulation datasets and intermediate artifacts are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5G | Fifth-generation mobile network |

| CDN | Content Delivery Network |

| MEC | Multi-access Edge Computing |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| LRU | Least Recently Used (cache policy) |

| M/M/1 | Single-server queue with Poisson arrivals and exponential service |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| PoP | Point of Presence (CDN) |

References

- Annual, C.; Report, I. Cisco Annual Internet Report (2018–2023) White Paper; Cisco Systems, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson. Ericsson Mobility Report June 2025; Ericsson: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Hui, N.; Cui, X.; Wu, J.; Peng, Y.; Qi, Y.; Xing, C. Service-Aware 6G: An Intelligent and Open Network Based on the Convergence of Communication, Computing and Caching. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2020, 6, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tian, L.; Liu, L.; Qi, Y. Fog Computing Enabled Future Mobile Communication Networks: A Convergence of Communication and Computing. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2019, 57, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Jha, R.K. A Survey of 5G Network: Architecture and Emerging Technologies. IEEE Access 2015, 3, 1206–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liang, F.; He, X.; Hatcher, W.G.; Lu, C.; Lin, J.; Yang, X. A Survey on the Edge Computing for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2017, 6, 6900–6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, H.; He, S.; Dong, M. Cost Minimization-Oriented Computation Offloading and Service Caching in Mobile Cloud-Edge Computing: An A3C-Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mec GS MEC 003-V3.2.1; Multi-Access Edge Computing (MEC); Framework and Reference Architecture. ETSI: Valbonne, France, 2024.

- Jazaeri, S.S.; Asghari, P.; Jabbehdari, S.; Javadi, H.H.S. Toward Caching Techniques in Edge Computing over SDN-IoT Architecture: A Review of Challenges, Solutions, and Open Issues. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 1311–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J. Application of Improved Q-Learning Algorithm in Dynamic Path Planning for Aircraft at Airports. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 107892–107905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Subhan, F.E.; Yaqoob, A.; Muntean, C.H.; Muntean, G.-M. A Survey on Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Improved Rich Media Content Delivery in a 5G and Beyond Network Slicing Context. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 1427–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, F.; Milito, R.; Zhu, J.; Addepalli, S. Fog Computing and Its Role in the Internet of Things. In MCC’ 12: Proceedings of the First Edition of the MCC Workshop on Mobile Cloud Computing; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.; Fang, C.; Khan, A. A Survey on the State-of-the-Art CDN Architectures and Future Directions. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2025, 236, 104106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Yan, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C. Fog-Computing-Based Radio Access Networks: Issues and Challenges. IEEE Netw. 2016, 30, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Bai, Y.; Song, B. A Knowledge Graph-Based Reinforcement Learning Approach for Cooperative Caching in MEC-Enabled Heterogeneous Networks. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2025, 11, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, T.; Samdanis, K.; Mada, B.; Flinck, H.; Dutta, S.; Sabella, D. On Multi-Access Edge Computing: A Survey of the Emerging 5G Network Edge Cloud Architecture and Orchestration. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 1657–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, T.; Li, C.; Lei, Y.; Li, G.; Cao, H.; Liu, Y. Cocktail Edge Caching: Ride Dynamic Trends of Content Popularity with Ensemble Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2021—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–13 May 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zabihi, Z.; Eftekhari Moghadam, A.M.; Rezvani, M.H. Reinforcement Learning Methods for Computation Offloading: A Systematic Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Hu, F.; Hao, Q. Deep Learning for Intelligent Wireless Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 2595–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Dai, X. Reinforcement Learning-Based Computation Offloading in Edge Computing: Principles, Methods, Challenges. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 108, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Decentralized Computation Offloading Game for Mobile Cloud Computing. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2015, 26, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, M.; Xia, F.; Xu, X.; Bilal, M. A Survey of Edge Caching: Key Issues and Challenges. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2024, 29, 818–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Edge Computing: Vision and Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, P.; Becvar, Z. Mobile Edge Computing: A Survey on Architecture and Computation Offloading. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 1628–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, C.; Huang, Y.; Quek, T.Q.S. Distributed Reinforcement Learning for Privacy-Preserving Dynamic Edge Caching. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 40, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomikos, N.; Zoupanos, S.; Charalambous, T.; Krikidis, I.; Petropulu, A. A Survey on Reinforcement Learning-Aided Caching in Mobile Edge Networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 4380–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Li, G.; Qi, T.; Dai, C. Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Cost-Efficient Proactive Video Caching in Energy-Constrained Mobile Edge Networks. Comput. Netw. 2025, 258, 111062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Rao, B.; Ding, Y.; Yang, S. Applications of Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Communication in Network Management: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.17030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderializadeh, N.; Hashemi, M. Energy-Aware Multi-Server Mobile Edge Computing: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 53rd Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 3–6 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Zhou, Q.; Li, J.; Guo, S.; Chen, H.; Wu, C.; Yang, Y. Adaptive Incentive and Resource Allocation for Blockchain-Supported Edge Video Streaming Systems: A Cooperative Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wen, M.; Basar, E.; Wu, Y.-C.; Wang, L.; Liu, W. Exploiting Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces in Edge Caching: Joint Hybrid Beamforming and Content Placement Optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 7799–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Ning, Z.; Ngai, E.C.-H.; Zhou, L.; Wei, J.; Cheng, J.; Hu, B.; Leung, V.C.M. Joint Resource Allocation for Latency-Sensitive Services Over Mobile Edge Computing Networks with Caching. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 4283–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortelano, D.; de Miguel, I.; Barroso, R.J.D.; Aguado, J.C.; Merayo, N.; Ruiz, L.; Asensio, A.; Masip-Bruin, X.; Fernández, P.; Lorenzo, R.M.; et al. A Comprehensive Survey on Reinforcement-Learning-Based Computation Offloading Techniques in Edge Computing Systems. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 216, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Leung, V.C.M.; Xu, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, Q. A Survey on Mobile Edge Computing: Focusing on Service Adoption and Provision. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 8267838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastug, E.; Bennis, M.; Debbah, M. Living on the Edge: The Role of Proactive Caching in 5G Wireless Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.J.C.H.; Dayan, P. Technical Note: Q-Learning. Mach. Learn. 1992, 8, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, N.C.; Hoang, D.T.; Gong, S.; Niyato, D.; Wang, P.; Liang, Y.-C.; Kim, D.I. Applications of Deep Reinforcement Learning in Communications and Networking: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 3133–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuja, J.; Bilal, K.; Alasmary, W.; Sinky, H.; Alanazi, E. Applying Machine Learning Techniques for Caching in Next-Generation Edge Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 181, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, R.A.; Hamza, E.K.; Humaidi, A.J. A modified CNN-IDS model for enhancing the efficacy of intrusion detection system. Meas. Sens. 2024, 35, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaan, S.S.; Korial, A.E.; Sarra, R.R.; Humaidi, A.J. Multilingual Web Traffic Forecasting for Network Management Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.D.; Khudheer, U.; Abdulsaheb, G.M. An adaptive smart street light system for smart city. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. Source Preview 2019, 16, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, A.; Seitz, J. An approach for QoS-aware routing in mobile ad hoc networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Symposium on Wireless Communication Systems, Brussels, Belgium, 25–28 August 2015; pp. 626–630. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.A.; Hasan, A.M.; Humaidi, A.J. Development of a memory-efficient and computationally cost-effective CNN for smart waste classification. J. Eng. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirjees, S.W.; Alkhalid, F.F.; Mudheher, A.H.; Humaidi, A.J. A Secure Password based Authentication with Variable Key Lengths Based on the Image Embedded Method. Mesopotamian J. Cybersecur. 2025, 5, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.A.; Al-Nayar, M.M.J.; Mahmood, A.M. Dynamic Low Power Clustering Strategy in MWSN. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 2023, 10, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, M.; Ahmad, I.A.; Hmeed, A.R.; Mukhlif, A.A. Enhanced EEG Signal Classification Using Machine Learning and Optimization Algorithm. Fusion Pract. Appl. 2025, 17, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.A.; Al-Nayar, M.M.J.; Mahmood, A.M. Investigation of Energy Efficient Clustering Algorithms in WSNs: A Review. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 2022, 9, 1693–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalloo, A.M.; Humaidi, A.J. Optimizing Machine Learning Models with Data-level Approximate Computing: The Role of Diverse Sampling, Precision Scaling, Quantization and Feature Selection Strategies. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, M.L.; Flaieh, E.H.; Humaidi, A.J. Embedded System Design of Path Planning for Planar Manipulator Based on Chaos A* Algorithm with Known-Obstacle Environment. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2022, 17, 4047–4064. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).