Abstract

This study proposes an indicator system for evaluating AI-assisted learning in higher education, combining evidence-based indicator development with expert-validated weighting. First, we review recent studies to extract candidate indicators and organize them into coherent dimensions. Next, a Delphi session with domain experts refines the second-order indicators and produces a measurable, non-redundant, implementation-ready index system. To capture interdependencies among indicators, we apply a hybrid Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory–Analytic Network Process (DEMATEL–ANP, DANP) approach to derive global indicator weights. The framework is empirically illustrated through a course-level application to examine its decision usefulness, interpretability, and face validity based on expert evaluations and structured feedback from academic staff. The results indicate that pedagogical content quality, adaptivity (especially difficulty adjustment), formative feedback quality, and learner engagement act as key drivers in the evaluation network, while ethics-related indicators operate primarily as enabling constraints. The proposed framework provides a transparent and scalable tool for quality assurance in AI-assisted higher education, supporting instructional design, accreditation reporting, and continuous improvement.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), and especially recent generative AI (GAI) models, is rapidly transforming higher education by augmenting learning environments with new capabilities. Integrating AI into Learning Management Systems (LMS) promises more personalized instruction, adaptive assessment, and real-time learning analytics [1]. Numerous studies report that AI-driven tools can enhance student engagement, tailor learning pathways, and improve educational quality and learning outcomes [2,3]. For example, recommender systems and conversational agents embedded in AI-enabled LMS have been shown to increase participation and provide individualized support [4,5]. AI adoption also reflects broader transformations in digital higher education, where algorithmic decision-making and automation increasingly shape instructional design [6], learner support [7], and assessment practices [8].

However, these opportunities are accompanied by significant concerns. Deploying AI in education raises technical and ethical challenges (such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, transparency, etc.) that require explicit governance and oversight [1,9]. UNESCO and other international organizations warn that the rapid, largely unregulated diffusion of generative AI has outpaced institutional readiness; many universities remain “largely unprepared to validate” these tools and ensure safe, equitable use [8]. At the same time, educational technologies evolve quickly, making traditional evaluation designs (e.g., long-term randomized trials) difficult to implement in practice [10]. Consequently, systematic evidence on the effectiveness of AI-assisted learning remains limited [11]. Reviews of LMS and e-learning research also highlight the lack of unified models for assessing teaching quality and learning gains in AI-enhanced environments [12]. This leaves faculty and administrators without robust frameworks to identify which AI features genuinely improve learning and which introduce unacceptable risks.

Note: For the purposes of this paper “AI-assisted learning” refers to educational settings in which AI technologies support and augment instructional and learning processes, while pedagogical control and academic responsibility remain primarily with human instructors.

Despite growing empirical studies on AI-assisted learning, there is still no standardized, causal-aware, and expert-validated indicator system that integrates pedagogical effectiveness, analytics-driven adaptivity, and ethical governance within a single evaluation model. Current evaluation approaches are often fragmented, focusing on isolated dimensions such as usability, engagement, or satisfaction [13], while underestimating the interdependencies among pedagogical, technological, and ethical factors [14,15,16]. In addition, the absence of standardized, empirically grounded indicator systems limits comparability across studies, reduces transparency, and weakens evidence-based decision-making. As AI capabilities diversify, robust multidimensional and methodologically rigorous evaluation tools become essential for responsible integration and for realizing the potential of AI-assisted learning.

To address this gap, the present study develops (i) a comprehensive indicator framework and (ii) a hybrid multi-criteria model combining the Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) [17] and the Analytic Network Process (ANP) [18] for evaluating AI-assisted learning. We integrate evidence from the literature with expert consensus to define measurable, non-redundant indicator system. DEMATEL is then used to model causal interdependencies among indicators, and ANP is applied to derive weights and to aggregate performance across indicators into an interpretable score. The result is a systematic and transparent tool for assessing AI-enhanced courses. This contribution aligns with recent calls for standardized quality and transparency in AI-driven education (e.g., initiatives such as “ELEVATE-AI LLMs”) [19], while operationalizing an evaluation approach tailored to higher-education learning contexts.

The aim of this study is to develop a comprehensive indicator framework and a hybrid DEMATEL–ANP (DANP) evaluation model for assessing the effectiveness of AI-assisted learning in a holistic, transparent, and empirically grounded manner. Unlike statistical causal models, which require large datasets and assume stable relationships, the proposed DANP framework is well suited for early-stage, rapidly evolving AI-assisted learning contexts where expert judgment and structural reasoning are critical.

The hybrid DANP approach is selected for weighting indicators because it explicitly models interdependencies among criteria. DEMATEL is first used to identify and quantify cause–effect relationships between indicators, distinguishing driving factors from outcome-oriented effects. This influence structure then informs the ANP network, which derives global weights while accounting for interrelations among criteria, rather than assuming independence. As a result, DANP produces weights that reflect both perceived importance and each criterion’s systemic influence within the AI-assisted learning ecosystem, supporting more realistic and interpretable evaluation outcomes.

The evaluation of AI-assisted learning constitutes an inherently multi-criteria decision problem. It involves simultaneously considering pedagogical effectiveness, learner engagement, personalization and adaptivity, assessment and feedback quality, ethical and governance requirements (including fairness, transparency, and data privacy), as well as organizational and technical constraints. These criteria are heterogeneous in nature, partly qualitative, potentially conflicting, and often characterized by limited or evolving empirical evidence, particularly in the context of rapidly developing generative AI technologies. Under such conditions, traditional single-criterion or purely statistical evaluation approaches are insufficient to capture the complexity of AI-assisted learning environments. A multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach therefore provides an appropriate and systematic framework for integrating expert judgments, combining qualitative and quantitative indicators, and making transparent trade-offs among competing evaluation dimensions when assessing the effectiveness of AI-assisted learning in higher education. In the proposed framework, MCDM serves as the overarching methodological foundation for modeling causal relationships among indicators and aggregating them into composite effectiveness scores through the hybrid DEMATEL–ANP approach.

This study contributes to the emerging field of AI-assisted learning evaluation in several ways. First, it proposes an evidence-based indicator framework derived from a systematic review of current scholarly literature, ensuring alignment with contemporary research and pedagogical challenges. Second, the framework is refined through a Delphi process to ensure practical relevance, measurability, and non-redundancy. Third, the methodological rigor is enhanced by integrating DEMATEL and ANP into a hybrid model that captures both causal structure and relative importance—an approach rarely applied in AI-mediated education. Finally, empirical validation involving academic staff provides further support for the framework’s clarity, relevance, and practical applicability. Collectively, these contributions offer a robust, multidimensional tool to support evidence-based instructional design and quality assurance in AI-assisted learning environments.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews existing evaluation approaches in AI-assisted learning and highlights methodological gaps. Section 3 outlines the research design and methodological procedures. Section 4 presents the proposed indicator system for evaluating AI-assisted learning, detailing the structure of dimensions and indicators and their conceptual grounding. Section 5 illustrates the practical implementation of the proposed indicator system, including the Delphi refinement of indicators, DEMATEL modeling of causal relationships, ANP derivation of indicator weights, and the construction of hybrid DANP weights. Section 6 reports the empirical validation based on data collected from academic staff and discusses the findings, implications, and limitations of the study. Finally, Section 7 concludes and offers directions for future research.

2. Classical and Contemporary Evaluation Models in the Context of AI-Assisted Learning

Research on program evaluation in higher education and e-learning provides a mature foundation of frameworks and metrics for assessing learning quality and impact. Classic outcome-oriented models, most notably Kirkpatrick’s four-level model [20], assess effectiveness across sequential stages, ranging from learners’ reactions and immediate learning outcomes to behavioral change and organizational results. In technology-mediated instruction, quality is often examined using multidimensional e-learning quality frameworks (e.g., the e-quality framework), which address content and material quality, instructional design, learner support, and technical or usability performance [21]. Additional approaches emphasize design determinants of online course quality, such as structure, presentation, interactivity, and support services [22], as well as curriculum alignment strategies like Backward Design [23,24] and assessment models focusing on academic integrity, feedback quality, and equity [25]. Systems-oriented and operational metrics (such as adoption rates, usage intensity, and course completion) are also widely used to monitor digital learning performance [26]. Collectively, these models define the conventional evaluation landscape for higher education and e-learning.

While these models remain relevant, GAI and other AI-enabled technologies expose structural limitations when classical frameworks are applied to effectiveness evaluation. Many existing approaches assume stable instructional conditions, predefined learning tasks, and transparent pedagogical processes. In contrast, GAI-enabled learning environments are dynamic (frequent tool updates, evolving functionalities) and often opaque (limited insight into algorithmic behavior and decision logic). This creates challenges in evaluating AI-specific dimensions such as fairness, privacy, transparency, and responsible governance, alongside pedagogical impacts of AI-mediated support and automation [1,27]. In practice, common evaluation models often emphasize short-term or easily measurable outcomes (e.g., learner satisfaction), while offering limited support for tracing sustained skill development, behavioral change, or long-term academic impact.

Several well-established models illustrate these challenges. Outcome-driven frameworks such as the Tyler model [28] rely on linear logic and stable objectives—assumptions difficult to maintain amid rapidly evolving AI capabilities and shifting educational competencies [23]. Instructional design models such as ADDIE [29] remain valuable for structured course development but may clash with the iterative, real-time adjustments required by AI-enhanced learning tools. Business-focused models like the Phillips return on investment (ROI) framework [30] promote financial accountability but often overlook core academic goals (e.g., critical thinking, disciplinary mastery) and ethical obligations related to AI use. Technology integration models such as SAMR [31] help categorize digital adoption but lack constructs for evaluating AI-specific risks, governance, or the interplay of pedagogy, adaptivity, and feedback. Competency-oriented frameworks such as Intelligent-TPACK [32,33] focus on educators’ knowledge and readiness but do not offer comprehensive models for assessing student outcomes or institutional oversight.

Across the AI-in-education literature, systematic reviews document a growing body of research on adaptive tutoring systems, personalized learning, intelligent assessment, learning analytics, and administrative automation [34]. In LMS contexts, studies highlight benefits such as automated learner support, content recommendation, instructor dashboards, and conversational agents. However, the evidence base remains fragmented. Many evaluations focus on feasibility, engagement, or perceived utility, and findings are often context-dependent, limiting comparability across institutions, disciplines, and AI implementations [34]. These limitations hinder efforts to identify which AI functionalities reliably improve learning outcomes, particularly when ethical and organizational considerations are involved [1,9].

More targeted evaluations of AI-enhanced learning tend to focus on isolated elements. For example, recent studies propose Delphi- or AHP-based indices for assessing the quality of AI-generated content, emphasizing accuracy and relevance [35]. Other research describes AI-enabled quality assurance systems that automate course review through machine learning or natural language processing [36]. While these approaches illustrate the feasibility of structured, multi-criteria evaluation, they remain limited in scope, addressing either content quality or general quality assurance (QA) processes, without offering an integrated framework for evaluating effectiveness across the full spectrum of AI-assisted learning dimensions (e.g., pedagogy, engagement, assessment, adaptivity, and ethics).

Table 1 synthesizes key classical and contemporary evaluation models, comparing their applicability to higher education and highlighting structural deficiencies in GAI-enabled learning environments. The analysis shows that although existing frameworks offer valuable conceptual tools, they often fall short in addressing the unique demands of AI-assisted learning. Traditional models tend to prioritize immediate perceptions and short-term gains, while overlooking complex, longitudinal outcomes like skill transfer or academic integrity. Curriculum- and process-based models support structured planning but rely on linear assumptions incompatible with evolving AI ecosystems. Business and ROI-oriented models focus on efficiency but fail to address educational ethics and systemic interdependencies. Even comprehensive e-learning quality frameworks frequently treat AI-related factors as peripheral rather than integrated components.

Table 1.

Comparison of evaluation models and their limitations in GAI-enabled higher education.

Given these shortcomings, recent scholarship and institutional guidance increasingly call for ethics-aware, system-level evaluation models capable of supporting continuous quality assurance in AI-assisted learning. For instance, Logan-Fleming et al. [37] emphasize that traditional QA cycles cannot keep pace with AI innovation and advocate for curriculum-embedded assurance models incorporating AI literacy and inclusive design. Others have proposed expanding evaluation rubrics to integrate ethical dimensions such as transparency and bias mitigation alongside traditional learning constructs, while practitioner guidance highlights transparency, security, and iterative refinement in LMS-based AI applications [9,27].

Collectively, the literature reveals a persistent gap: higher education lacks a holistic, empirically grounded indicator system that can support comparative assessment of AI-assisted courses and capture the interdependencies among pedagogical, technological, and ethical factors. This gap motivates the current study’s approach—developing a multidimensional, operational indicator framework aligned with the core requirements of AI-assisted learning, combined with a weighting and aggregation model that explicitly captures causal and network-like relationships among evaluation criteria.

3. Research Methodology

This section outlines the research methodology used to develop and validate the proposed evaluation framework for AI-assisted learning in higher education. The study follows a sequential, mixed-methods design that integrates evidence-based indicator construction, expert consensus validation, and network-based multi-criteria decision modeling. Specifically, the methodology combines thematic synthesis of recent literature with a Delphi refinement process and applies a hybrid DEMATEL–ANP (DANP) approach to capture causal interdependencies among indicators and derive robust global weights for course evaluation and benchmarking.

3.1. Research Design Overview

The proposed methodological framework follows the logic of MCDM, which is widely used for the evaluation of complex systems characterized by multiple, interdependent criteria and limited availability of objective performance data. MCDM approaches [38] are particularly suitable in educational and socio-technical contexts, where expert judgment plays a central role and causal relationships among evaluation dimensions must be explicitly modeled. In methodological terms, the overall structure of the framework is consistent with established hybrid MCDM applications, in which DEMATEL is used to model causal interdependencies among criteria, and ANP is subsequently applied to derive global weights within an interdependent network structure. The primary adaptation introduced in this study concerns the domain-specific construction of the indicator system and the interpretation of causal relations in the context of AI-assisted learning. In particular, ethical governance and algorithmic transparency are treated as explicit evaluation dimensions, reflecting the specific risks and decision mechanisms associated with AI-enabled educational environments.

The unit of analysis of the multi-stage, expert-based MCDM framework is an AI-enabled course or module delivered via a university LMS. The study aims to produce (i) a parsimonious indicator framework and (ii) a set of global indicator weights derived through a hybrid DANP procedure, enabling weighted scoring and comparative assessment of AI-assisted courses.

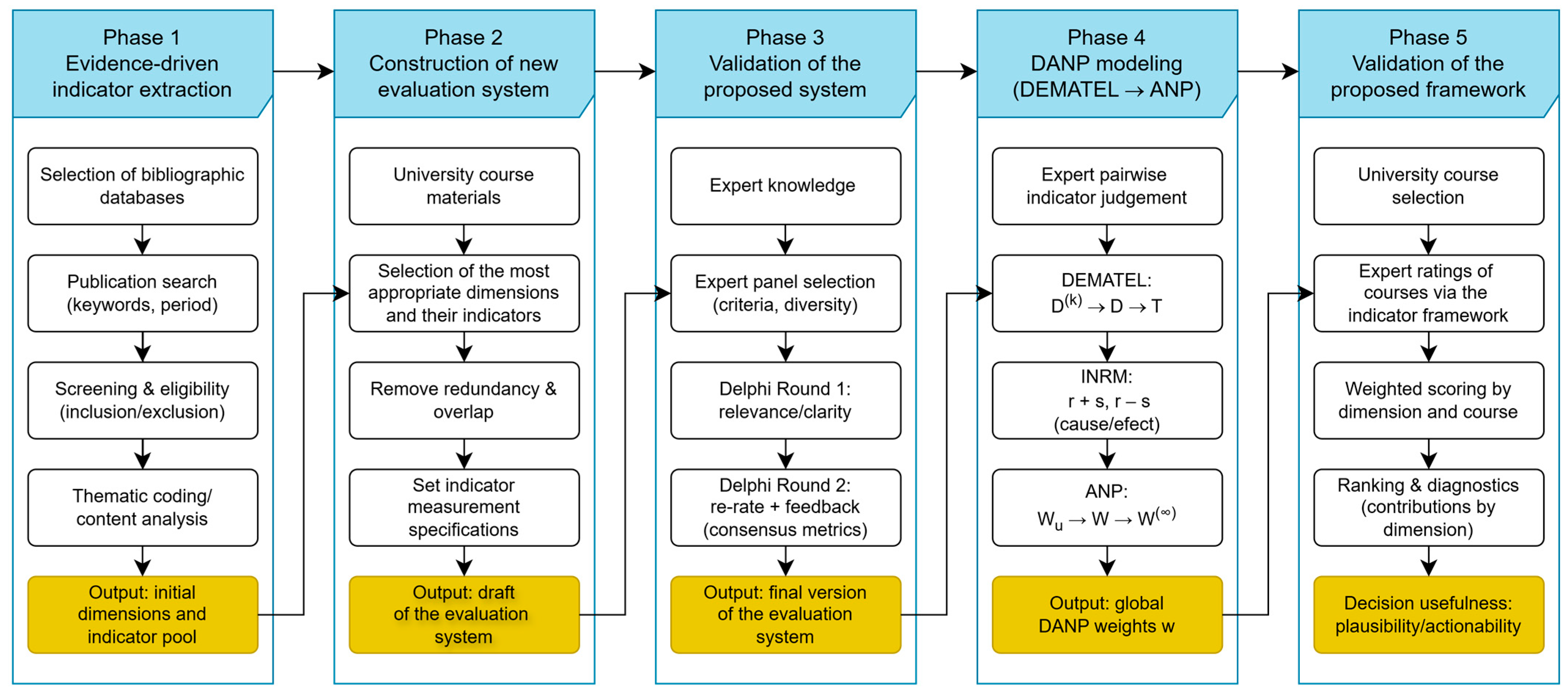

The methodology unfolds in five sequential phases: (1) evidence-based indicator extraction, (2) construction of new evaluation system, (3) validation of the proposed system, (4) DANP modeling (DEMATEL → ANP), and (5) validation of the proposed framework. The overall process is illustrated in Figure 1, summarizing the key phases, data inputs, intermediate outputs, and final deliverables.

Figure 1.

Methodological workflow of the proposed evaluation framework for AI-based learning. Note: INRM denotes the Influential Network Relation Map.

The next subsection details the process of identifying candidate indicators from the literature, structuring them into six evaluation dimensions, and refining them into a set of 18 measurable criteria suitable for expert elicitation and DANP modeling.

3.2. Identifying Evaluation Dimensions and Their Indicators

Indicator identification followed an evidence-driven approach. A structured literature search targeted peer-reviewed publications from 2020 to 2025 on topics including AI in education, AI-enabled LMS, generative AI-supported learning, adaptive learning, learning analytics, AI-driven assessment and feedback, and ethical and responsible AI. Searches were conducted across major academic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library), using keyword combinations such as generative AI, large language models, adaptive learning, transparency, and fairness.

Studies were included if they: (i) addressed AI-enabled learning processes or tools in higher education or related contexts, (ii) reported evaluative constructs, risks, or outcomes relevant to assessment, and (iii) offered conceptual or empirical grounding for measurable indicators. Exclusions removed purely technical papers, opinion pieces, and studies lacking transferable evaluation criteria.

The literature search yielded 249 records across the selected databases. After removal of duplicates, 174 records remained for title and abstract screening. Based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 83 studies were retained for full-text review. Following full-text assessment, 62 peer-reviewed studies were included in the structured coding process used to derive candidate indicators.

While the review followed transparent and structured screening procedures inspired by systematic review practices, it was not intended as a full PRISMA-compliant systematic review, but as an evidence-informed foundation for indicator construction.

Eligible studies were subjected to a structured qualitative coding process aimed at extracting recurring evaluation-relevant concepts related to AI-assisted learning quality. The coding focused on pedagogical, adaptive, assessment-related, engagement-related, and ethical aspects reported across empirical and conceptual contributions. Redundant items were merged to ensure indicators were (a) clearly defined, (b) observable by experts, and (c) non-overlapping across dimensions.

This structured coding process was conducted by a team of three independent researchers with expertise in educational technology, AI in education, and quantitative evaluation methods. All coders had prior experience with systematic literature reviews and indicator-based framework construction. Before full-scale coding, a shared coding protocol and indicator extraction template were developed and pilot-tested on a subset of the reviewed literature to ensure consistent interpretation of coding categories.

Each included article was independently coded by at least two researchers. Agreement was assessed using percentage overlap and correlations among extracted indicator categories, indicating a high level of convergence in the identified themes. Any remaining discrepancies were resolved through iterative discussion and consensus refinement, with the involvement of a third reviewer when necessary. This procedure ensured that the final indicator pool was grounded in reproducible evidence extraction rather than in the subjective judgment of a single researcher.

The resulting coded concepts were aggregated and synthesized into a preliminary pool of candidate indicators, which subsequently entered the Delphi refinement process. The initial indicators were organized into six dimensions: Pedagogical Design and Content Quality (PD), Learner Engagement and Analytics (LE), Adaptivity and Personalization (AP), Assessment and Feedback (AF), Ethics, Privacy, and Governance (EG), and Technological Infrastructure and Usability (TI).

The resulting indicator set comprised 18 indicators (three per dimension): PD1—Content Quality, PD2—Instructional Design, PD3—Alignment with Learning Objectives; LE1—Interactivity, LE2—Motivation and Emotional Engagement, LE3—Collaboration and Social Learning; AP1—Content Adaptivity, AP2—Learning Path Personalization, AP3—Difficulty Adjustment; AF1—Feedback Quality, AF2—Assessment Diversity, AF3—Feedback Timeliness; EG1—Data Privacy and Security, EG2—Fairness and Inclusivity, EG3—Transparency and Accountability; and TI1—Accessibility and User Experience, TI2—System Responsiveness and Latency, TI3—LMS Integration and Interoperability. This preliminary indicator set served as the input for the Delphi-based refinement process described in Section 3.3, where the final indicator system was established.

3.3. Expert Panel and Delphi Refinement

A purposively selected expert panel was assembled to validate the indicator system. Potential experts were identified through professional networks, institutional affiliations, and publication records in AI-in-education and educational technology research. Inclusion criteria required demonstrated expertise in at least one relevant domain: higher education pedagogy, educational technology, AI in education (including GAI), learning analytics, assessment design, or AI ethics and governance. Experts also were required to meet the following criteria: (i) a doctoral degree or equivalent professional qualification in a relevant field; (ii) a minimum of five years of professional or academic experience in a relevant field; and (iii) demonstrated involvement in the design, implementation, evaluation, or governance of AI-supported or digitally mediated courses. Invitations outlining the study objectives, Delphi procedure, and expected time commitment were sent individually by email. Participation was voluntary, and all responses were anonymized to reduce dominance and conformity bias.

The final Delphi panel consisted of seven experts, a size consistent with methodological recommendations for expert-based Delphi studies in complex and specialized domains. Among these seven experts, five were academics and two were industry practitioners. Experts were invited based on publication records and professional affiliations, ensuring diversity in geography and roles. All panelists met minimum professional experience requirements and were familiar with course-level evaluation practices.

An anonymized summary of the Delphi panel characteristics, including areas of expertise and years of professional experience, is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Delphi expert panel (anonymized).

A multi-round Delphi procedure was implemented to confirm indicator relevance and distinctiveness. The Delphi process was conducted entirely online to facilitate participation from geographically dispersed experts. Structured questionnaires were administered using standardized survey instruments. Each Delphi round consisted of three sequential tasks: (i) individual rating of indicators, (ii) optional qualitative justification or suggestions for modification, and (iii) review of aggregated feedback in subsequent rounds. To enhance procedural rigor, identical instructions and evaluation criteria were provided to all experts, and no direct interaction among panelists was allowed during the rating phases.

In Round 1, experts independently evaluated the initial indicator set in terms of relevance, clarity, and conceptual distinctiveness using a five-point Likert scale. Qualitative comments were collected to identify ambiguities, redundancies, or missing aspects. Based on quantitative results and thematic analysis of comments, indicators were revised, merged, or removed.

In Round 2, experts reassessed the revised indicator set, with access to anonymized summary statistics (median, interquartile range) and synthesized rationales from Round 1. This controlled feedback mechanism supported convergence while preserving independent judgment. Additional rounds were planned only if predefined consensus thresholds were not met, but convergence was achieved within two rounds.

Indicators were retained when they consistently met the predefined consensus criteria, such as high median relevance scores combined with acceptable dispersion. Indicators were revised or removed when they repeatedly failed to achieve agreement or exhibited substantial conceptual overlap with other indicators. Consensus was assessed using standard Delphi metrics, including median scores, interquartile ranges (IQR), percentage agreement above a relevance threshold, and Kendall’s coefficient of concordance () for inter-rater agreement. After the second Delphi round, the finalized indicator system demonstrated acceptable levels of consensus, with a Kendall’s value of 0.821, indicating high inter-rater concordance among experts.

During the Delphi process, particular attention was paid to the conceptual distinctiveness and practical separability of the initially defined dimensions. Expert feedback indicated that indicators within the Technological Infrastructure and Usability dimension exhibited substantial overlap with other dimensions, especially Learner Engagement and Analytics and Ethics, Privacy and Governance, when considered at the course evaluation level. Some of the panelists noted that infrastructure-related aspects, such as system responsiveness, accessibility, and LMS integration, are largely institution-dependent prerequisites rather than course-level design or pedagogical features. As a result, these indicators were judged to have limited discriminative power for evaluating the effectiveness of AI-assisted learning at the course or module level, where instructional design and AI-mediated learning processes are the primary focus.

Based on this feedback and the predefined consensus criteria, the Technological Infrastructure and Usability dimension was removed from the final framework, and its most salient concerns were treated as contextual or boundary conditions rather than core evaluation indicators. This refinement resulted in a more parsimonious and analytically focused framework better aligned with expert judgement and the intended decision-support purpose of the evaluation system.

The final indicator system included 15 indicators across five validated dimensions (PD, LE, AP, AF, EG), each clearly defined for weighting and empirical application.

3.4. DANP Weighting Procedure

The DANP weighting procedure was carried out by the same seven experts who participated in the Delphi process. This ensured conceptual continuity between indicator refinement and weighting, as all experts were fully familiar with the finalized indicator definitions and evaluation framework.

To operationalize the indicator framework and derive weights, we apply a hybrid DANP model. DANP is particularly suitable for this context as it captures both (i) causal relationships among indicators and (ii) their relative importance within an interdependent network structure. This section presents the key concepts, modelling logic, and main computational steps of the DANP procedure as implemented in the study, while a detailed, step-by-step description of the methodology, including matrix construction and normalization procedures, is provided in Appendix A.1.

Stage 1: DEMATEL—Causal Influence Modelling.

DEMATEL models the direct and indirect influence of each indicator on others based on expert input. Experts rated the influence of indicator on using a 0–4 scale (0 = no influence, 4 = very high influence). Individual direct-relation matrices were aggregated (e.g., arithmetic mean) into a group matrix , which was normalized to form :

The total relation matrix was calculated as:

where is the identity matrix.

For each indicator , influence () and dependence () were computed:

Prominence and net causality informed the INRM, forming the input structure for ANP.

Stage 2: ANP—Network-Based Global Weightings.

The DEMATEL-derived influence structure defines the ANP network. Unlike hierarchical models, ANP allows feedback and cross-cluster dependence. The unweighted supermatrix is constructed using normalized influence values. If required, cluster weights are applied to create the weighted supermatrix . The limit supermatrix is obtained by powering to convergence:

The stabilized column values of yield the global DANP weights for each indicator , where . These weights reflect both perceived importance and systemic influence.

The DANP model supports informed decision-making by:

- Capturing causal and systemic interdependencies among evaluation criteria;

- Allowing structured expert judgment to complement limited course-level empirical data in early-stage evaluation contexts;

- Producing weights that are realistic, justifiable, and aligned with the complexity of AI-assisted learning ecosystems.

The complete computational procedure and pseudocode are provided in Appendix A.

3.5. Empirical Validation and Decision Usefulness

Validation was conducted through an illustrative application in which experts evaluated multiple AI-assisted courses using the finalized indicators and their corresponding DANP-derived weights . Decision usefulness was examined by eliciting expert judgments on whether (i) overall course rankings, (ii) indicator-level contributions, and (iii) dimension-level profiles were plausible, interpretable, and actionable for academic decision-making.

Feedback was collected using structured instruments (e.g., alternatives assessment via real scores in the interval [1,5]) and open-ended comments. The evaluation focused on three criteria:

- Actionability: ability to identify areas for course improvement;

- Interpretability: clarity of indicator contributions and dimension profiles;

- Face validity: alignment between evaluation outcomes and expert judgement regarding course design and AI integration.

Course-level scoring was conducted by the same expert panel involved in the Delphi process (N = 7), ensuring continuity and domain familiarity. Each expert independently rated all courses on each indicator using a real-valued scale in the interval [1,5]. For each course and indicator , ratings were aggregated by averaging across experts to obtain . The overall score for course was computed as a weighted sum of indicator scores:

Dimension-level scores were calculated by summing the weighted scores of the three indicators within each dimension, enabling diagnostic insights alongside the global evaluation. When cross-course or cross-study comparability is required, overall and dimension-level scores can be normalized to the [0, 1] interval using the scale maximum.

Overall, the empirical validation indicates that the proposed framework is not only methodologically coherent but also practically useful for instructional design, quality assurance, and evidence-informed decision-making in AI-assisted higher education.

4. Proposed Indicator System for Evaluation of AI-Assisted Learning

The proposed framework is a multidimensional system developed to overcome the limitations of traditional instructional assessment models when applied to AI-supported learning. Recent AI-in-education literature highlights quality risks in AI-generated resources, the need for robust personalization and feedback mechanisms, and the centrality of ethical, privacy, and governance safeguards in AI-mediated learning environments. Accordingly, the indicator system, grounded in prior empirical evidence and established evaluation frameworks [6,35,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] and refined through expert consensus using a Delphi procedure, is organized into five dimensions—Pedagogical Design (PD), Learner Engagement and Analytics (LE), Adaptivity and Personalization (AP), Assessment and Feedback (AF), and Ethics, Privacy and Governance (EG). Each dimension is operationalized through three indicators, resulting in a total of 15 indicators.

4.1. Pedagogical Design and Content Quality (PD)

This dimension assesses whether AI-assisted learning is instructionally sound and aligned with course goals, while accounting for AI-specific failure modes such as hallucinations, inaccuracy, and content drift [6,35,39,40,42,43].

- PD1—Content Quality: Accuracy, clarity, currency, and level-appropriateness of AI-generated instructional content; evaluates error prevalence, conceptual coherence, and bias-free formulation in AI outputs [35,39,40].

- PD2—Instructional Design: Degree to which AI-supported materials and activities implement sound design principles (sequencing, scaffolding, worked examples, practice opportunities), indicating whether AI supports learning processes rather than merely supplying information [6,40,43].

- PD3—Alignment with Learning Objectives: Extent to which AI-generated content, activities, and resources are mapped to intended learning outcomes/competencies; checks whether AI use remains goal-directed and avoids tangential or mis-leveled outputs [42].

4.2. Learner Engagement and Analytics (LE)

This dimension captures how AI affects learners’ participation and persistence, and whether engagement is supported through meaningful interaction rather than passive reliance on AI [40,42,44,45,46,47,48].

- LE1—Interactivity: Level and quality of two-way learner–AI interaction that supports active learning (dialogue, prompting, guided problem-solving, adaptive questioning), beyond one-directional content delivery [40,44].

- LE2—Motivation and Emotional Engagement: Influence of AI support on learner motivation, interest, and persistence; examines whether the system sustains productive challenge and avoids demotivating patterns (e.g., over-assistance or frustration) [40,45,46].

- LE3—Collaboration and Social Learning: Extent to which AI supports peer interaction and collaborative learning (AI-facilitated group work, discussion support, participation equity), ensuring AI use does not displace social learning processes [42,45,46,47,48].

4.3. Adaptivity and Personalization (AP)

This dimension evaluates the extent to which AI enables real-time tailoring of learning to individual needs, including what learners study, in what sequence, and at what level of challenge, based on learner data and interaction evidence [39,42,45,46,49,50].

- AP1—Content Adaptivity: Ability to select, modify, or generate instructional content in response to a learner model (e.g., performance signals), including remedial explanations, targeted examples, and enrichment [39,46].

- AP2—Learning Path Personalization: Ability to personalize sequencing and curriculum flow through recommendations, branching, or mastery-based progression (e.g., revisiting prerequisites, tailoring routes to learner goals) [42,45,46].

- AP3—Difficulty Adjustment: Real-time calibration of task difficulty and scaffolding (hints, decomposition, challenge escalation) to maintain productive challenge (e.g., self-pacing, scaffolding, and targeted support based on progress) [49,50].

4.4. Assessment and Feedback (AF)

This dimension captures how AI supports the learning loop: measuring learning and providing feedback that enables improvement. It emphasizes quality, diversity, and timeliness of AI-enabled assessment and feedback, while acknowledging risks of inaccurate feedback and integrity issues [40,42,45,46,47,48,49,50].

- AF1—Feedback Quality: Accuracy, specificity, and actionability of feedback (diagnostic value, guidance for improvement, alignment with criteria/rubrics), avoiding vague or incorrect AI-generated explanations [40,46,47,48].

- AF2—Assessment Diversity: Breadth of supported assessment formats (e.g., quizzes, open-ended tasks, scenarios, projects) and AI-enabled generation of variants/authentic tasks to assess different competencies and reduce predictability [42,46,47].

- AF3—Feedback Timeliness: Speed and availability of feedback (real-time or near-immediate responses, on-demand guidance), while maintaining correctness and consistency [45,46,47,48,49,50].

4.5. Ethics, Privacy, and Governance (EG)

This dimension evaluates whether AI is deployed responsibly and in ways that sustain trust, equity, compliance, and institutional accountability—issues repeatedly emphasized as intrinsic to educational quality in GAI contexts [39,41,42].

- EG1—Data Privacy and Security: Data minimization, informed use/consent, secure storage/transmission, access control, and compliance (e.g., GDPR), including retention and third-party processing policies [39,41].

- EG2—Fairness and Inclusivity: Evidence that the system avoids discriminatory outputs and performs consistently across learner groups; includes bias monitoring/audits and accessibility features [39,41].

- EG3—Transparency and Accountability: Clarity on when/how AI is used; explainability where relevant; logging and oversight mechanisms, including human-in-the-loop control, reporting channels, and contestability/appeal for high-stakes outputs [39,41,42].

4.6. Comparison to Traditional Evaluation Frameworks

Compared with conventional course evaluation and e-learning quality assurance models, the proposed approach is broader in scope and more explicitly tailored to AI-enabled learning mechanisms. Traditional evaluation systems typically emphasize pedagogical design, general engagement, learner satisfaction, and outcome indicators, often operationalized through surveys, grades, or completion metrics. While such frameworks often acknowledge ethical principles at an institutional or policy level, personalization is rarely treated as a core quality requirement. Data privacy, fairness, and transparency are typically not structurally integrated as explicit, course-level evaluation criteria, but are instead assumed to be addressed externally through institutional governance arrangements. In contrast, the proposed framework makes these previously “background” conditions explicit evaluation criteria, reflecting the fact that AI systems can directly influence learners through data processing, automated decision-making, and opaque content generation processes.

The framework further operationalizes opportunities specific to generative AI as measurable evaluation standards. For example, AI technologies enable near-immediate, individualized feedback and the scalable generation of diverse assessment prompts. Accordingly, the proposed indicator set assesses not only the presence of feedback, but also its timeliness, accuracy, and instructional usefulness (AF1–AF3), as well as the diversity of assessment formats (AF2). Similarly, adaptivity is treated as a first-class requirement (AP1–AP3), allowing evaluators to distinguish between systems that genuinely personalize learning and those that merely automate content delivery.

At the same time, the proposed measurement system entails several practical considerations. First, certain indicators (such as fairness assessment, transparency verification, and adaptivity inspection) may require greater analytical effort than conventional survey-based evaluations. Second, the evaluation dimensions are interdependent in practice—for example, stronger adaptivity often enhances engagement, while weak content quality may undermine motivation and raise ethical concerns. Although the framework separates dimensions for analytical clarity, interpretation should consider cross-dimensional interactions. Moreover, the framework is primarily designed to assess instructional design and process quality and is therefore best applied alongside outcome-based measures (e.g., learning achievement, retention, or skill transfer) to support triangulation and strengthen validation.

The indicator framework is deliberately limited to five dimensions and fifteen indicators to balance parsimony, coverage, and methodological feasibility. Conceptually, these five dimensions span the core stages of the AI-assisted learning cycle: Pedagogical Design (PD), Learner Engagement and Analytics (LE), Adaptivity and Personalization (AP), Assessment and Feedback (AF), and Ethics, Privacy and Governance (EG). This structure was not adopted from a single pre-existing model, but emerged through an evidence-driven synthesis of recurring conceptual patterns identified in the literature review and the subsequent expert-based refinement process. Operationally, the fifteen-indicator structure results from an evidence-driven reduction process that eliminates redundancy and avoids indicator proliferation, thereby improving interpretability and reducing respondent burden.

From a methodological perspective, compactness is essential for DEMATEL–ANP-based weighting and interdependency modelling. Large criterion sets substantially increase pairwise judgment demands, expert fatigue, and inconsistency risks. The adopted 5 × 3 structure preserves multidimensional coverage while maintaining the stability, tractability, and reliability of expert elicitation and subsequent causal and weight estimation.

5. Practical Example of Implementing the Proposed Indicator System

The objective of this practical example is to compute (i) the cluster-level influence weights and (ii) the global (indicator-level) weights that account for interdependencies among criteria. The DANP procedure is performed in two stages. First, DEMATEL is applied to the aggregated expert direct-influence judgments (0–4 scale) to obtain the normalized direct-relation matrix, the total-relation matrix, and the prominence and causal degree measures, which support interpretation of the cause–effect structure among indicators. Second, the ANP stage transforms the DEMATEL-derived interdependencies into a supermatrix model; the unweighted supermatrix is constructed by block-wise column normalization, then weighted using cluster-level influence coefficients to obtain the weighted supermatrix, which is iterated to convergence to yield the limit supermatrix and the final DANP global weights.

5.1. DEMATEL Analysis

Three domain experts evaluated the direct influence of each indicator on every other using a five-point scale. Their individual matrices were aggregated using the arithmetic mean to form the group direct-influence matrix (Table 3). Diagonal elements were set to zero by definition.

Table 3.

Direct influence matrix .

The normalized direct-relation matrix was derived, followed by the total-relation matrix , which captures both direct and indirect influences (Table 4).

Table 4.

Total-relation matrix T (comprehensive influence matrix).

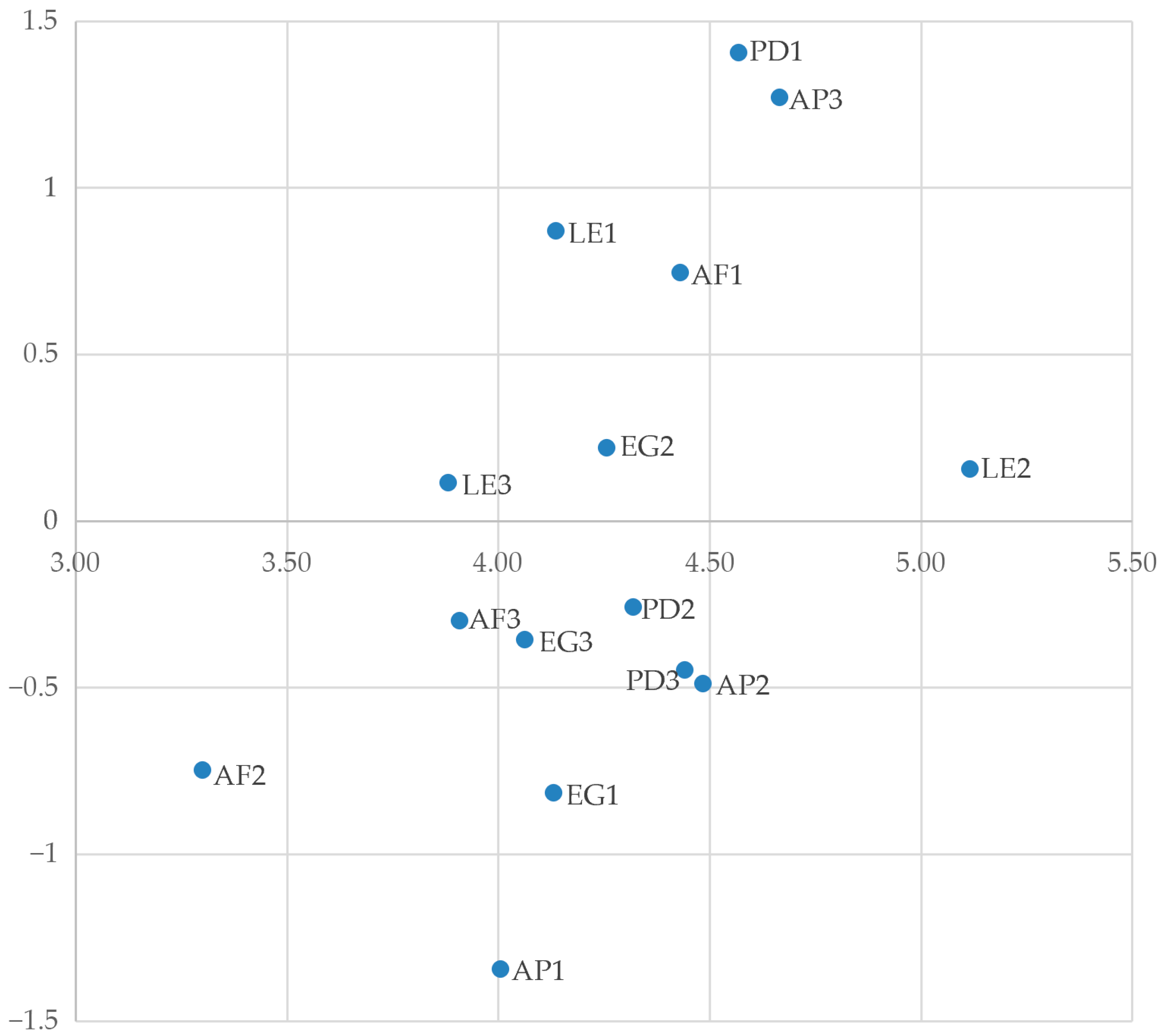

From this, we calculated the influence degree (), dependence degree (), prominence , and causal degree , presented in Table 5. The resulting cause–effect map (Figure 2) identifies Content Quality and Difficulty Adjustment as the most influential indicators, followed by Interactivity and Feedback Quality. These core drivers exert upstream control over more dependent criteria such as Content Adaptivity, Data Privacy, and Assessment Diversity.

Table 5.

Influence degree, dependence degree, prominence, and causal degree.

Figure 2.

Cause–effect mapping of indicators, based on prominence () and relation (), plotted on the x and y axes, respectively.

Indicators with high prominence but negative causal degree, such as Learning Path Personalization (AP2) and Alignment with Learning Objectives (PD3), appear central but function primarily as outcomes of upstream mechanisms. The causal structure suggests strategic interventions should focus on highly prominent causal indicators.

In Table 5 and Figure 2, the DEMATEL results reveal a clear cause–effect structure among the 15 indicators. Indicators with positive causal degree () form the driving set, led by Content Quality (PD1; = 1.403) and Difficulty Adjustment (AP3; 1.269), followed by Interactivity (LE1; 0.869) and Feedback Quality (AF1; 0.744). This pattern inricates that system effectiveness is primarily pushed by the quality of instructional content and by adaptive, interactive, feedback-intensive learning processes, which then propagate improvements through the broader network. A second tier of drivers—Fairness (EG2; 0.219), Motivation (LE2; 0.153) and Collaboration (LE3; 0.113)—suggests that engagement and governance-related factors contribute as supportive causes, but with weaker net influence. In contrast, indicators with negative causal degree are positioned as dependent outcomes, most notably Content Adaptivity (AP1; −1.345), Data Privacy (EG1; −0.819), and Assessment Diversity (AF2; −0.750), implying that these elements are shaped by upstream design and interaction mechanisms rather than driving the system directly.

Prominence () further highlights centrality: Motivation (LE2; = 5.117) is the most connected indicator, while (AP3; 4.666), (PD1; 4.570), (AP2; 4.485) and (AF1; 4.431) also show high system embeddedness, reinforcing their diagnostic value. Overall, the joint reading of causal degree and prominence suggests that the most effective intervention points are those that combine high connectivity with net causality (particularly PD1 and AP3) whereas highly prominent but net-effect criteria (e.g., AP2 and PD3) function more as performance outcomes that improve indirectly when upstream drivers are strengthened.

5.2. DANP Weight Derivation

Before deriving the global ANP priorities, we first estimated the relative importance of the main clusters (PD, LE, AP, AF, and EG). The matrix was then column-normalized to produce the cluster weight matrix. These cluster weights capture the comparative role of each cluster within the interdependent system and were subsequently used to weight the corresponding blocks of the ANP supermatrix. The final cluster weight matrix is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Cluster weight matrix.

The normalized coefficients quantify how the total influence originating from a source cluster (column) is distributed across target clusters (rows). Several dependency patterns emerge.

- Pedagogical Design (PD) primarily feeds Learner Engagement (LE): PD → LE is the largest entry in the PD column ( = 0.229), indicating that instructional structure and content decisions propagate most strongly into interactivity and motivation. PD’s remaining influence is distributed across AP ( = 0.213, PD itself ( = 0.208), AF ( = 0.174), and EG ( = 0.175), suggesting PD acts as a broad upstream contributor rather than a single-direction lever.

- Learner Engagement (LE) most strongly supports Pedagogical Design (PD): LE → PD is the dominant linkage from LE ( = 0.231), followed closely by LE → LE ( = 0.221) and LE → AP ( = 0.193). This pattern is consistent with engagement traces (interaction intensity, persistence) informing instructional adjustments and refinements more directly than they drive assessment routines (LE → AF is the weakest, = 0.159.

- Adaptivity and Personalization (AP) most strongly drives Learner Engagement (LE): AP → LE is the largest entry in the AP column ( = 0.237), with additional spillovers toward PD ( = 0.217) and AF ( = 0.196). This aligns with the role of adaptive sequencing and difficulty control in sustaining participation and shaping subsequent learning activities.

- Assessment and Feedback (AF) channels its largest share toward Pedagogical Design (PD): AF → PD is the strongest outgoing flow from AF ( = 0.225), followed by AF → LE ( = 0.209) and AF → AP ( = 0.205). This suggests that assessment evidence and feedback loops mainly feed back into pedagogical redesign and interaction patterns, rather than remaining confined within the AF cluster: AF → AF ( = 0.173).

- Ethics, Privacy and Governance (EG) primarily conditions PD and LE: EG → PD and EG → LE are tied as the two largest entries in the EG column ( = 0.221; = 0.221), followed by EG → AF ( = 0.184). This indicates that privacy, fairness, and transparency considerations act chiefly through course structuring and learners’ willingness to participate, while EG’s direct influence on adaptivity is comparatively smaller: EG → AP ( = 0.193).

- Diagonal values are not dominant (≈0.173–0.221): within-cluster self-reinforcement is comparable to, and often weaker than, several cross-cluster flows. This confirms that the evaluation system is governed primarily by cross-dimensional interactions, supporting the use of a network-based weighting approach (DANP) rather than independence-assuming weighting.

In sum, the matrix highlights strong couplings along the pathways PD → LE, AP → LE, and AF → PD, with EG exerting its main influence through PD and LE. This structure is consistent with AI-assisted learning settings in which instructional design shapes engagement, adaptivity sustains participation, assessment evidence feeds back into redesign, and governance conditions both participation and course organization.

The DEMATEL-derived reachability matrix was used to define the network structure of the ANP model. Links were established between indicators based on their reachability, and the total-relation matrix was normalized by columns to create the unweighted supermatrix. Cluster-level influence weights were then elicited from experts and used to weight the supermatrix blocks, producing the weighted supermatrix (Table 7).

Table 7.

Weighted supermatrix.

The weighted supermatrix was powered to convergence, producing the limit supermatrix (Table 8). Global DANP weights were extracted from this limit matrix (Table 9).

Table 8.

Limit supermatrix.

Table 9.

Indicator weights.

According to the obtained DANP weights (Table 9), the highest global priorities are concentrated in Pedagogical Design, Adaptivity and Personalization, and Learner Engagement, with Assessment and Feedback also prominent. The top-weighted indicators are Content Quality (PD1, = 0.095) and Difficulty Adjustment (AP3, = 0.092), followed by Motivation (LE2, = 0.082), Feedback Quality (AF1, = 0.081), and Interactivity (LE1, = 0.077). Overall, the pattern indicates that, within the interdependent DANP structure, perceived effectiveness is driven primarily by the quality of instructional content and the system’s capacity to adapt task demands and sustain active engagement, while other features play more supporting roles.

- Content Quality (PD1, = 0.095) ranks first, implying that the overall perceived strength of AI-assisted learning depends most on the accuracy, clarity, relevance, and completeness of instructional content. Even when engagement and adaptivity mechanisms are strong, weak or unreliable content constrains learning value, explaining PD1’s dominant position.

- Difficulty Adjustment (AP3, = 0.092) and Learning Path Personalization (AP2, = 0.064) receive comparatively high weights, highlighting adaptive control of challenge level and sequencing as key leverage points. Practically, this emphasizes the importance of matching task complexity to learner ability and guiding progression coherently through the curriculum.

- In Assessment & Feedback, Feedback Quality (AF1, = 0.081) is weighted more strongly than Feedback Timeliness (AF3, = 0.059) and Assessment Diversity (AF2, = 0.037). This suggests that, in the network, what feedback communicates (accuracy, specificity, actionability) contributes more to perceived impact than speed or variety alone.

- In Learner Engagement, Motivation (LE2, = 0.082) and Interactivity (LE1, = 0.077) are both highly ranked, indicating that engagement is driven mainly by active learner–system exchange and motivational support. Collaboration (LE3, = 0.065) remains meaningful but appears secondary to these more direct engagement mechanisms.

- The lowest weights are assigned to Assessment Diversity (AF2, = 0.037) and Content Adaptivity (AP1, = 0.042), with Data Privacy (EG1, = 0.051) also in the lower range. This does not imply these aspects are negligible; rather, within the estimated interdependency structure they act more as enablers or constraints and/or their influence is partly mediated through higher-priority drivers such as content quality, adaptive difficulty control, and feedback quality.

The DANP results imply that improvement efforts should primarily target high-quality content, adaptive difficulty and sequencing, actionable feedback, and motivating interactive learning experiences, while ethics and governance and broader assessment features function mainly as essential supporting conditions in the current network.

Additional computational details for this practical example are reported in Appendix A.

These hybrid DANP-derived weights are practically plausible for AI-based learning contexts because they prioritize factors that most directly determine whether AI support translates into substantive learning gains, rather than merely increased “AI activity.” In contrast, lower weights are assigned to criteria that primarily function as baseline requirements or enabling conditions, whose effects on learning outcomes are typically indirect and mediated through stronger upstream drivers.

Highest weights (core drivers of learning value).

Content Quality (PD1, = 0.095) is the top weight, which is consistent with practice: if AI-generated/explained content is unclear, inaccurate, or misaligned, it undermines everything else—engagement, feedback, and adaptivity become irrelevant or even harmful (e.g., “confidently wrong” explanations). In AI-based courses, content quality is also directly tied to hallucination control, prompt/scaffold quality, and instructor curation.

Difficulty Adjustment (AP3, = 0.092) being nearly as high is also expected: one of AI’s distinctive advantages is maintaining an appropriate challenge level in real time (hints, scaffolding, step decomposition, stretching advanced learners). This is a high-leverage mechanism for both learning efficiency and motivation.

Motivation (LE2, = 0.082) and Interactivity (LE1, = 0.077) being high reflects a common reality: AI tools deliver value when students actively engage (question–answer loops, iterative refinement, practice with feedback). Motivation is especially central because AI can either support persistence (micro-successes, personalized pacing) or cause disengagement (over-reliance, passive copying).

Feedback Quality (AF1, = 0.081) is correctly prioritized: in AI-supported learning, the usefulness and correctness of feedback typically matters more than speed. Poor feedback scales harm fast; high-quality feedback scales benefit fast.

Middle weights (important, but usually mediated).

Collaboration (LE3, = 0.065) is meaningful but slightly lower than interactivity/motivation—often because collaboration depends on course orchestration and assessment design, not only on the AI tool itself.

Learning Path (AP2, = 0.064) aligns with many university contexts: macro-level sequencing is valuable, but many courses still constrain path flexibility (syllabus structure), so its incremental effect can be smaller than real-time difficulty control.

Instructional Design (PD2, = 0.062) and Alignment with learning objectives (PD3, = 0.062) are mid-range, which is plausible when experts view them as embedded through PD1 and through the course design itself. In other words, if content is high-quality and the course is competently designed, marginal differences in “alignment” may not dominate the network.

Lower weights (often “must-have” constraints or downstream effects).

Fairness (EG2, = 0.072) is relatively high within ethics, which makes sense: bias and unequal performance across groups directly damages legitimacy and learning outcomes, and it can also reduce engagement and trust.

Transparency (EG3, = 0.058) and Privacy (EG1, = 0.051) being lower does not mean they are unimportant; it often means they behave like threshold criteria in higher education: institutions expect a minimum compliance baseline (policies, consent, GDPR practices). Once that baseline is met, differences may be perceived as less performance-driving than content, adaptivity, engagement, and feedback.

Feedback timeliness (AF3, = 0.059) being below AF1 matches practice: “instant but wrong/vague” is worse than “slightly slower but precise and actionable”.

Content adaptivity (AP1, = 0.042) and Assessment diversity (AF2, = 0.037) being lowest is plausible for two reasons: (i) they are harder to implement robustly (true content adaptation and varied authentic assessment), and (ii) their effects are frequently indirect, working through difficulty adjustment, feedback quality, and engagement—so the network weighting can push their global contribution downward.

As a practical profile for AI-based learning, this weighting pattern is coherent: it emphasizes (1) trustworthy instructional content, (2) adaptive challenge control, (3) sustained interactive engagement, and (4) high-quality feedback, while treating ethics and governance as essential enablers and giving less relative priority to features whose benefits are more context-dependent (assessment diversity, fine-grained content adaptivity).

Overall, the obtained DANP weights indicate that perceived effectiveness of AI-based learning is driven primarily by content quality (PD1), adaptive difficulty regulation (AP3), and actionable feedback and engagement mechanisms (AF1, LE2, LE1), whereas the remaining indicators play comparatively more supportive/enabling roles within the interdependent evaluation network.

6. Empirical Application and Decision-Usefulness Evaluation

This section presents an empirical application of the proposed evaluation framework to examine its decision usefulness, interpretability, and face validity in realistic AI-assisted learning settings. The primary objective is to assess whether the framework produces plausible, transparent, and actionable evaluation outcomes that can support informed course-level decision-making.

The analysis does not aim to establish psychometric construct validity or to validate the indicator system as a latent measurement scale. Instead, the framework is evaluated as a decision-support and diagnostic tool, consistent with its design-oriented and MCDM-based nature. The five-dimensional indicator structure is theory-driven, grounded in prior literature and expert consensus, rather than empirically derived through factor-analytic techniques.

While tendencies in inter-rater agreement were examined to assess consistency across expert evaluations, the study does not seek to establish full psychometric reliability in the sense of scale validation. Expert judgments are employed to support comparative evaluation and decision analysis, rather than to estimate latent traits. Formal reliability testing and construct validation using larger and more diverse samples are left for future research.

To examine the practical applicability of the proposed framework, three domain experts assessed four GAI-based university courses using the final indicator system and the derived DANP weights. These experts were drawn from the original seven-member Delphi/DANP panel and were selected based on their direct teaching experience with the evaluated course types. The courses evaluated were Electronic Government, Digital Marketing, Management Information Systems (MIS), and Internet Technologies in Tourism.

The empirical application is exploratory and illustrative in nature. Its purpose is to demonstrate how the proposed framework can be applied in practice and to assess the interpretability and plausibility of its outputs, rather than to support statistical generalization or population-level inference. The use of a small number of highly qualified experts is consistent with common practice in exploratory MCDM applications, where depth of judgment and cognitive feasibility are prioritized.

To enhance transparency and reduce subjectivity in the use of the 1–5 rating scale, an operational scoring guide was developed. The guide provides indicative anchors for low (1), medium (3), and high (5) performance levels for each indicator and specifies typical evidence sources considered during scoring (e.g., course syllabi, LMS artifacts, and assessment materials). The full scoring guide is provided in Appendix B, Table A3.

6.1. Aggregation of Expert Evaluations

The experts evaluated each course using 15 indicators, assigning real-valued scores on a scale from 1 to 5. Table 10 presents the average rating for each indicator and course.

Table 10.

Mean expert ratings for each framework indicator (transposed).

The results exhibit a clear pattern across the four courses:

E-Government excels in Pedagogical Design (PD1–PD3) and Ethics & Governance (EG1–EG3) but is weaker in Adaptivity & Personalization (AP1–AP3).

Digital Marketing scores highest in Engagement & Learning Analytics (LE1–LE3) and Adaptivity & Personalization.

MIS shows moderate, balanced performance across all dimensions.

Internet Technologies in Tourism scores highly in Engagement & Learning Analytics and Assessment & Feedback, with solid results in Pedagogical Design.

6.2. Weighted Contributions and Total Course Scores

Each indicator score was multiplied by its DANP weight to compute weighted contributions and overall course scores (Table 11).

Table 11.

Weighted indicator contributions and total scores for the evaluated courses.

The obtained overall course ranking is:

- Digital Marketing—4.185;

- Internet Technologies in Tourism—3.955;

- E-Government—3.807;

- MIS—3.765.

In this ranking, E-Government and MIS remain very close; Tourism sits clearly between Digital Marketing and the other two.

6.3. Dimension-Level View

Indicators were grouped by their framework dimensions, and weighted contributions were summed per dimension (Table 12):

Table 12.

Dimension-level weighted scores (PD, LE, AP, AF, EG) by course and total.

Digital Marketing records the strongest results in Engagement & Learning Analytics (LE = 1.032) and Adaptivity & Personalization (AP = 0.888), while also maintaining solid performance in Pedagogical Design (PD = 0.884) and Assessment & Feedback (AF = 0.764). Its weakest dimension is Ethics & Governance (EG = 0.617).

E-Government demonstrates its main advantage in Pedagogical Design (PD = 0.995) and performs well in Ethics & Governance (EG = 0.816). However, it is comparatively weaker in Adaptivity & Personalization (AP = 0.553) and Assessment & Feedback (AF = 0.658), which reduces its overall standing relative to the highest-performing course.

MIS shows a relatively even profile across dimensions, particularly LE (0.820), AP (0.717), and EG (0.688), but does not reach the top score in any single dimension, indicating consistent but not dominant performance within the proposed evaluation framework.

6.4. Discussion

The weighted course results yield a clear and interpretable ranking of the four AI-based courses. Digital Marketing achieves the highest total score (4.185), followed by Internet Technologies in Tourism (3.955), E-Government (3.807), and MIS (3.765) (Table 11). While the gap between E-Government and MIS is marginal, the dimension-level decomposition (Table 12) reveals meaningfully different performance profiles that align with the courses’ stated design emphases and delivery formats (e.g., lecture/seminar balance and overall contact hours).

E-Government (Total = 3.807) performs strongest in Pedagogical Design (PD = 0.995) and Ethics & Governance (EG = 0.816) (Table 12). At the indicator level, this is reflected in high weighted contributions for PD1 (0.439) and EG2 (0.333), alongside consistently strong PD2–PD3 and EG1–EG3 terms (Table 11). In contrast, Adaptivity & Personalization is its weakest dimension (AP = 0.553), with comparatively low contributions across AP1–AP3 (notably AP1 = 0.125) (Table 11). Overall, the course appears methodologically robust and governance-oriented, while offering relatively limited AI-enabled individualized support.

Digital Marketing (Total = 4.185) leads primarily due to its top scores in Engagement & Learning Analytics (LE = 1.032) and Adaptivity & Personalization (AP = 0.888), supported by solid Assessment & Feedback (AF = 0.764) and strong Pedagogical Design (PD = 0.884) (Table 12). This pattern is also visible at the indicator level, with large contributions for LE2 (0.386), LE1 (0.355), and AP3 (0.425) (Table 11). The main relative limitation is Ethics & Governance (EG = 0.617), the lowest EG score among the four courses, suggesting that governance-related elements are present but less emphasized than in E-Government (Table 12).

MIS (Total ≈ 3.765) shows a comparatively even profile across dimensions: PD = 0.917, LE = 0.820, AP = 0.717, AF = 0.624, EG = 0.688, without a single dominant peak (Table 12). Table 11 similarly shows mid-range contributions across most indicators (e.g., PD1 = 0.411, LE2 = 0.295, AP3 = 0.333, EG2 = 0.275), indicating consistent performance but limited specialization. In other words, MIS is “good overall”, yet its AI-related strengths are not as sharply differentiated as those of Digital Marketing (LE/AP) or E-Government (PD/EG).

Internet Technologies in Tourism (Total = 3.955) ranks second overall and is characterized by strong Engagement & Learning Analytics (LE = 0.958) and solid Pedagogical Design (PD = 0.907), together with comparatively strong Assessment & Feedback (AF = 0.705) (Table 12). This is supported by high indicator contributions such as LE2 = 0.353, LE1 = 0.340, and AF1 = 0.323 (Table 11). Its AP (0.717) and EG (0.670) scores are moderate rather than leading, suggesting clear opportunities to further strengthen adaptive support and to embed governance and privacy considerations more systematically within the course context (Table 12).

Taken together, Table 11 and Table 12 show that combining expert ratings with DANP weights produces a coherent and diagnostically useful narrative: Digital Marketing excels in engagement, analytics and personalization; E-Government leads in pedagogy and governance; Internet Technologies in Tourism is particularly strong in engagement and feedback; and MIS remains broadly consistent but less distinctive in any single framework dimension.

7. Conclusions

This study developed and validated a comprehensive evaluation framework for assessing the effectiveness of AI-assisted learning in higher education. The framework conceptualizes effectiveness across five dimensions: Pedagogical Design and Content Quality (PD), Learner Engagement and Analytics (LE), Assessment and Feedback (AF), Adaptivity and Personalization (AP), and Ethics, Privacy, and Governance (EG). These dimensions are operationalized through 15 indicators, whose relative importance was determined using a hybrid DANP approach that accounts for causal relationships and interdependencies among criteria. The framework was empirically tested through expert-based evaluation of four GAI-supported university courses: Electronic Government, Digital Marketing, Management Information Systems (MIS), and Internet Technologies in Tourism.

Beyond its methodological and practical contributions, the proposed framework speaks directly to several ongoing debates in the AI-assisted learning literature (Section 2). First, it mitigates fragmentation in evaluation by integrating pedagogical, adaptive, assessment-related, and ethical dimensions into a single, coherent decision model rather than treating them in isolation. Second, it addresses concerns about opacity and accountability in AI-supported education by operationalizing ethics, privacy, and governance not as external constraints but as assessable, course-level quality dimensions. Third, by explicitly modelling interdependencies among indicators, it informs ongoing discussion about whether personalization, engagement, and feedback function as independent features or as mutually reinforcing processes within AI-mediated learning systems. Overall, the study advances the field by moving from largely descriptive accounts of AI use toward structured, decision-oriented evaluation models that can support empirical comparison and theoretical refinement.

In addition, the empirical application demonstrates that the framework captures effectiveness factors highlighted in both academic and policy discourses. The DEMATEL results yield interpretable causal structures, distinguishing systemic drivers (e.g., pedagogical design, engagement, adaptivity) from more outcome-oriented indicators (e.g., feedback quality, perceived transparency). These relationships were then translated into global DANP weights and applied to expert ratings to generate a consistent course ordering, Digital Marketing Internet Technologies in Tourism E-Government MIS, alongside diagnostic profiles that summarize each course’s relative strengths and areas for improvement.

The inclusion of the Internet Technologies in Tourism course, delivered as a compact 15 h Master’s module, provided an important validation test. It demonstrated the framework’s capacity to differentiate performance across both disciplinary boundaries and instructional formats. Notably, this course scored highly in engagement and feedback despite its brevity, suggesting that short, intensive courses can achieve high effectiveness when AI tools are tightly integrated into active learning and formative assessment processes. At the same time, its moderate performance in personalization and governance dimensions highlighted actionable opportunities, especially in managing ethical risks related to data use and recommender systems in tourism education.

Theoretically, the study contributes in three key ways. First, it advances a multidimensional evaluation model that incorporates AI-specific features such as advanced analytics, adaptivity, and governance considerations—areas often underrepresented in traditional e-learning frameworks. Second, it extends the application of the DANP method to the domain of higher education, showing how expert knowledge and systemic interdependencies can be formalized in a transparent weighting model. Third, it reframes AI-based course evaluation as a socio-technical system problem, moving beyond checklist-based models toward a nuanced analysis that recognizes how pedagogical, technical, and ethical components interact.

Practically, the framework offers concrete benefits for multiple stakeholders:

- For instructors and instructional designers, it provides a structured lens for reviewing and refining course design. For example, while the E-Government course was strong in pedagogy and ethics, it underutilized AI for personalization. Digital Marketing, conversely, leveraged AI for engagement and adaptivity but showed gaps in ethical scaffolding. The Tourism course balanced engagement and feedback well but would benefit from greater emphasis on transparency and privacy.

- For programme coordinators and academic leaders, the indicator-weighting combination enables comparative assessment across courses and supports prioritization of course improvements, staff development, or investment in learning technologies.

- For IT units and technology vendors, the framework clarifies which AI features contribute not just to functionality, but to pedagogical quality and ethical acceptability, guiding procurement, customization, and governance.

- For policy makers and quality assurance bodies, the framework offers a transparent and multidimensional reference for articulating expectations about responsible and effective AI integration in higher education.

Based on the findings, several stakeholder-oriented recommendations can be made:

- Instructors and designers can use the framework for self-assessment and as a design checklist when integrating AI. Compact modules should emphasize high-leverage features such as AI-driven feedback and concise ethics components tied to applied cases.

- Programme coordinators can apply the framework in program-level reviews to ensure systematic AI integration and use DANP weights to identify the most impactful intervention points.

- Teaching and learning centers can embed the indicators into peer-review tools and provide targeted training for weaker dimensions such as feedback, adaptivity, and governance.

- Institutional leaders can incorporate the framework into broader AI governance policies to align educational and ethical criteria with decision-making around AI use.

Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The indicator weights and validation were based on a small expert sample and applied to four courses within specific disciplinary and institutional contexts, limiting generalizability. The expert ratings are subjective, and while the DANP procedure structures these inputs, it cannot eliminate interpretive variation. The study focused primarily on methodological development and illustrative validation; broader psychometric validation and large-scale deployment were beyond scope. The small number of experts involved in the empirical application limits the robustness of aggregated judgments and sensitivity to individual biases. Consequently, the reported course scores and rankings should be interpreted as illustrative rather than definitive. Future studies will extend the application to larger expert samples and examine the stability of results through sensitivity and robustness analyses.

To support replication, comparison, and further methodological development, this study specifies the evaluation procedure as a sequence of clearly delineated steps and artefacts. Replication requires: (i) defining the unit of analysis as an AI-supported course or module; (ii) applying the same evidence-driven indicator identification logic or adopting the validated indicator set provided in this study; (iii) recruiting a multi-disciplinary expert panel meeting the stated expertise criteria; (iv) conducting Delphi-based refinement using the described consensus thresholds; (v) eliciting pairwise influence judgments for DEMATEL and relative importance judgments for ANP using the matrices defined in Appendix A; and (vi) computing global indicator weights and course scores via weighted aggregation.

While numerical weights are context-dependent and expected to vary across institutions, the structure of dimensions, indicators, and causal relationships provides a reusable evaluation template. Future studies may replicate the full procedure, adapt specific indicators, or compare resulting weight patterns across institutional or disciplinary contexts.

The proposed contribution lies primarily in the methodological structure and indicator logic rather than in fixed numerical weights, which are expected to be sensitive to institutional context, course type, and AI maturity level.