Abstract

Targeted multimodal sentiment classification is frequently impeded by the semantic sparsity of social media content, where text is brief and context is implicit. Traditional methods that rely on direct concatenation of textual and visual features often fail to resolve the ambiguity of specific targets due to a lack of alignment between modalities. In this paper, we propose the Complementary Description Network (CDNet) to bridge this informational gap. CDNet incorporates automatically generated image descriptions as an additional semantic bridge, in contrast to methods that handle text and images as distinct streams. The framework enhances the input representation by directly translating visual content into text, allowing for more accurate interactions between the opinion target and the visual narrative. We further introduce a complementary reconstruction module that functions as a regularizer, forcing the model to retain deep semantic cues during fusion. Empirical results on the Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017 benchmarks confirm that CDNet outperforms existing baselines. The findings suggest that visual-to-text augmentation is an effective strategy for compensating for the limited context inherent in short texts.

1. Introduction

Social media platforms like Weibo and Twitter are widely used by people and have a significant influence on communication. They now play a crucial role in daily life. As the popularity of social media increases, users post a lot of multimodal content, primarily text and images, to express their ideas and emotions. Effectively performing sentiment analysis on this extensive and diverse data can help us better understand public sentiment and opinion trends, and can provide useful empirical evidence for government and corporate decision-making. Consequently, how to accurately extract people’s sentiment from social media has attracted increasing attention.

Targeted sentiment classification, also known as aspect-based sentiment classification, takes classical sentiment analysis to the level of specific targets in a sentence [1,2,3,4]. The goal is to assess whether feelings toward a given target are favorable, negative, or neutral. However, on social media, individuals frequently write short and casual sentences. These sentences can be ambiguous, and the text alone sometimes does not provide enough clues for accurate sentiment prediction. In many cases, the attached image brings additional emotional cues and can help the classifier make a better decision. As shown in Figure 1, the user’s feeling is often mainly expressed through the visual scene, while the text only hints at this feeling with a few words.

Figure 1.

Representative examples for targeted multimodal sentiment classification task. Blue text in brackets indicates target entities; colored italicized text denotes the corresponding sentiment labels (e.g., Positive, Neutral, Negative).

Effectively extracting and integrating complementing information from several modalities is the primary issue in targeted multimodal sentiment categorization. This problem was examined from a number of angles in early research. For instance, Xu et al. [5] suggested a dual memory network that allows textual and visual features to interact through cross-modal operations while modeling them independently. In addition, Yu et al. [6] introduced a target-sensitive attention network to model the interactions between sentence–image pairs for targeted sentiment classification. More recently, with the development of pre-trained language models, Yu and Jiang [7] designed a BERT-based multimodal architecture to capture complex relationships among targets, text, and images.

Even with these developments, current approaches still confront significant challenges in effectively synthesizing multimodal information. First, many existing methods treat textual and visual modalities as separate streams that are only combined via simple concatenation or late fusion. This isolationist processing fails to capture the deep, intrinsic semantic alignment between the opinion target and the visual scene. Second, while recent works have attempted to bridge this gap using auxiliary information, they often fall short in synergistic integration. For instance, Khan and Fu [8] translates images into captions to convert the multimodal task into a text-pair classification problem. While innovative, this “translation-based” approach risks discarding fine-grained visual details (e.g., facial expressions or background ambiance) that are not captured by the generated caption. Consequently, treating descriptions as a replacement for, rather than a complement to, visual features limits the model’s ability to fully comprehend the sentiment.

To address these limitations, we introduce a Complementary Description Network designed for multimodal targeted sentiment classification using image descriptions. Our approach provides a novel methodology for seamlessly integrating image descriptions with target and text information to construct enhanced sentence representations while modeling dynamic interactions between these generated sentences and associated images. The primary contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- We use generated image descriptions to compensate for the semantic sparsity of social media text, providing additional context that supports more reliable sentiment inference.

- We introduce the Complementary Description Network (CDNet), which integrates image descriptions as auxiliary data to model intricate relationships among text, targets, and images for enhanced targeted multimodal sentiment classification.

- We develop a specialized complementary reconstruction module within CDNet that extracts deep semantic insights to improve the effective utilization of information embedded in image descriptions.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Relevant work is reviewed in Section 2. The architecture of CDNet is described in Section 3. Our experimental results, including comparisons, ablation studies, and visualizations, are reported in Section 4. Lastly, the paper is concluded in Section 5.

2. Related Work

2.1. Text Sentiment Analysis

Text-based sentiment classification has been extensively studied in natural language processing [9,10,11]. The objective is to deduce the underlying sentiment from the text in order to get relevant data regarding the attitudes and opinions of users. When working with large-scale textual data, this task is especially crucial because human inspection is not practical. Additionally, by helping computers better understand and respond to users’ emotional states, sentiment analysis might facilitate more natural human–computer interaction. Consequently, text sentiment analysis has emerged as a central issue in natural language processing (NLP) and serves as the foundation for numerous applications in affective computing and opinion mining.

Traditional statistical models, manually created rules, and external knowledge sources were the main tools utilized in early sentiment analysis research [12,13,14,15,16]. At first, these techniques were crucial. However, because they mostly relied on human feature creation and domain-specific sentiment lexicons, they did not scale well. Deep learning later gained popularity and altered sentiment analysis. Instead of being created by hand, features might be automatically learned from data using deep models. Numerous neural architectures have been investigated. Recursive neural networks were used to model sentence structure [17]. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) were applied to represent word sequences [18,19], while convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were used to capture local patterns [20]. Later, attention mechanisms were introduced so that the model could focus on context words that are important for a given target [21,22]. More recently, pre-trained language models have become widely used. Several works [23,24] have adapted BERT [25] for targeted sentiment classification and reported strong performance by using its contextual representations.

Text-based approaches have performed well, but because they only employ one modality, they are inherently constrained. Posts on social media rarely consist only of text; instead, they frequently include brief, casual text together with pictures. In certain situations, text might not offer sufficient context for accurate sentiment analysis. Short text misunderstandings can be resolved by additional hints provided by visual data. As a result, more recent research has focused on multimodal sentiment analysis, which includes both text and pictures.

2.2. Multimodal Sentiment Analysis

These days, a lot of social media users use both text and photos to convey their ideas and feelings rather than just text. Traditional text-only sentiment analysis techniques are no longer able to properly capture online expressions as a result of this shift. As a result, multimodal sentiment analysis has become popular among researchers. Depending on the task’s granularity, current research in this area can be loosely divided into two categories.

The first stream deals with coarse-grained analysis, where the goal is to categorize a post’s overall sentiment. Prior studies [26,27,28,29] have developed various fusion techniques to handle this. The consensus among these works is that fusing information from diverse modalities consistently outperforms unimodal baselines by augmenting the feature space. However, while effective for coarse-grained, these generic approaches often struggle to adapt to the specific demands of targeted classification tasks, where precision regarding specific entities is required. In this paper, we move beyond these broad methods to propose a model specifically tailored for target-oriented tasks. The second stream focuses on fine-grained or targeted sentiment analysis. This area has gained traction as it tackles the more complex challenge of discerning sentiment directed at specific entities within a multimodal post [5,6,7]. Our study is closely related to the approach in [8] (CapTrBERT), which examined the use of supplemental picture descriptions to facilitate this effort. However, CapTrBERT primarily functions by translating visual inputs into the textual domain, thereby bypassing the challenge of direct visual–text alignment. In contrast, our CDNet approach is distinct as it employs descriptions to guide the interaction between the original visual features and the target text, ensuring that neither the semantic structure of the description nor the raw visual information is discarded.

Despite advancements, multimodal approaches still have several obvious drawbacks. Many models merely combine the properties of textual and visual data at a later point, treating them as two distinct streams. As a result, the comprehension of the data is still superficial and they do not accurately represent how text and visuals complement one another. Additionally, it is difficult for current architectures to explain how an image might alter or clarify a sentence’s emotion in various settings. In several pieces, image captions are added as supplementary information, but they are frequently not thoroughly integrated with the text and the image. As a result, techniques that can more effectively combine textual and visual cues are still needed.

3. Methodology

This section begins by stating the problem and then introduces the Complementary Description Network (CDNet) structure. After this broad look, we examine the CDNet parts designed for targeted multimodal emotion analysis. This work looks at social media situations where people’s posts have text and a related picture.

3.1. Task Formulation

Let denote a dataset of multimodal instances derived from tweets or reviews. Each instance comprises a textual sequence of n words, denoted as , a specific opinion target containing m words, , and an accompanying image . Each target is associated with a sentiment label . Our objective is to learn a mapping function that accurately predicts the sentiment polarity for the target within the sample .

3.2. Proposed Approach Overview

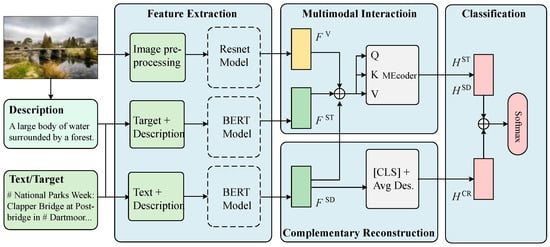

Instead of typical fusion methods that just combine text and images, our approach uses image descriptions as a way to understand complex cross-modal relationships. The CDNet design is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

CDNet framework overview. The model integrates image descriptions through four main stages: feature extraction, multimodal interaction, complementary reconstruction, and final sentiment classification.

This framework runs in four stages. First, the Feature Extraction part encodes three data inputs: text–target pairs, text–description sequences, and basic visual features. Next, the Multimodal Interaction part uses attention mechanisms to separate intra-modal dependencies in the text and match text with visual data. A key part is the Complementary Reconstruction part that makes sure auxiliary info is saved by using semantic consistency, instead of just using the image descriptions. Last, the Classification part changes the combined representation to a probability distribution over sentiment classes through a fully connected layer.

3.3. Feature Extraction Module

The feature extraction module creates detailed semantic representations from the inputs. The design includes a dual-branch structure. One branch uses a pre-trained language model to encode text data (targets and descriptions). The other branch extracts features from the images using a visual backbone.

3.3.1. Text Representation Extraction

For textual encoding, we select BERT as the foundational model. Its ability to extract deep contextual correlations makes it particularly suitable for distinguishing the sentiment of specific targets within a sentence. Rather than treating words in isolation, BERT captures the intricate interactions between the target entity and the context words.

In the standard setting for targeted sentiment analysis, the input is treated as a sentence-pair classification problem. We construct the input sequence by concatenating the context sentence S and the target phrase T. The resulting sequence follows the format below:

where and denote the tokens for the sentence and target, respectively. The [CLS] token aggregates the sequence-level information, and the [SEP] token serves as a delimiter.

To enrich the semantic space, we introduce a parallel input stream combining the context sentence S with an image description D. Following the protocol of [8], we generate descriptions that contain standardized, class-relevant semantic features. This strategy not only constructs a unified textual and visual–semantic sequence but also ensures fair comparability with existing baselines. This structure creates a unified sequence containing both textual and visual–semantic information:

where represents the description tokens. Both the text-target (ST) and text–description (SD) sequences are fed into the shared BERT encoder to yield the hidden states and :

where d is the dimensionality of the hidden states. By encoding these two streams, we provide the subsequent modules with a richer set of features that encapsulate both the target-specific context and the visual narrative.

3.3.2. Image Representation Extraction

For visual feature extraction, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) remain the dominant architecture in the field. Following standard protocols in multimodal sentiment analysis, we employ a CNN-based backbone to generate dense image representations. Before feeding the data into the network, we perform standard preprocessing by resizing the raw input image I to 224 × 224 pixels, yielding the transformed image . We then extract visual features from the final convolutional layer of a ResNet model [30] pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset [31]. Unlike using the final classification layer, tapping into the convolutional layer allows us to capture high-level semantic information while retaining spatial resolution. The extraction process is defined as:

The output consists of 49 regional feature vectors (corresponding to a 7 × 7 spatial grid), where each region is represented as a 2048-dimensional vector. To enable interaction with the textual modality, we project these visual features into the shared semantic space using a learnable linear transformation:

where is the weight matrix used to map the visual dimensions to the hidden dimension d.

3.4. Multimodal Interaction Module

Subsequent to the aforementioned procedures, the tasks of text representation extraction and image representation extraction involve distinct and independent learning of discriminative features. It is imperative not only to acquire a grasp of individual modality features but also to comprehend their interdependencies in the context of multimodal sentiment analysis. Consequently, after obtaining representations for both text and images, we introduce a multimodal interaction module. This module is purposefully engineered to facilitate the acquisition of relationships among the target, text, and image components, thereby augmenting the accuracy of targeted multimodal sentiment classification.

Direct fusion of multimodal features can impair classification performance due to the independent semantics of text and images. To address this limitation, we employ an attention-based multimodal encoder that integrates text, target, and image features into a unified representation. The attention mechanism assigns differential weights to input sequence components, ensuring that the most relevant features from each modality contribute proportionally to the final representation. This approach enables the model to selectively emphasize critical cross-modal information while mitigating the semantic misalignment inherent in naive feature concatenation. The attention mechanism can be formalized as follows:

where Q, K, and V are the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, derived from the fused features , , and . is the dimension of the key vectors, which serves to scale the dot product, ensuring stable gradients during training. The softmax function is applied to the scaled dot product to generate the attention weights, which are then used to produce a weighted sum of the value vectors.

For the interactive fusion of text, target, and images, we obtain the fused sequence features and , which highlight the most important information in the combined feature representations:

The multimodal interaction module incorporates the attention mechanism to selectively focus on the most relevant parts of the input, effectively capturing the inter-modal dependencies. This attention-driven fusion allows the model to better align and integrate complementary information from both text and images, resulting in a more robust and context-aware representation.

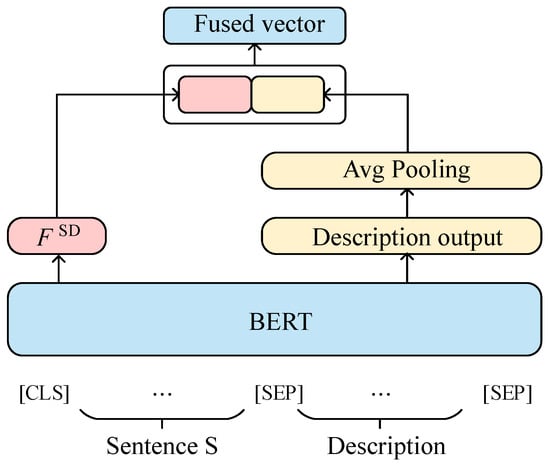

3.5. Complementary Reconstruction Module

Although the multimodal interaction module captures cross-modal dependencies, relying solely on the final classification objective can lead to the “forgetting” of auxiliary information. Specifically, the subtle semantic nuances provided by the image descriptions may be diluted as the network primarily optimizes for the dominant text-target features. To address this, we introduce the Complementary Reconstruction Module, which serves as a semantic regularizer.

The core principle of this module is to enforce a strong semantic alignment between the fused representation and the original description. As illustrated in Figure 3, instead of discarding the description tokens after encoding, we explicitly recover their semantic content to reinforce the primary classification task. The process operates as follows: First, we extract the hidden states corresponding to the image description tokens from the text-description stream. We then apply average pooling to these states to obtain a condensed global representation of the description. This global vector captures the essence of the visual content as interpreted by the text. Next, we concatenate this averaged description vector with the sentence-level representation (derived from the [CLS] token). This operation explicitly re-injects the visual–semantic signals into the fused feature space. The resulting combined feature, , is formally defined as:

Figure 3.

The architecture of the complementary reconstruction module, designed to enforce semantic consistency via feature reconstruction.

Subsequently, is processed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to produce the final reconstructed feature . This feature contains enriched semantic information that is robust against noise and is subsequently used for the final sentiment classification:

By integrating , the model ensures that the auxiliary descriptive knowledge remains active and influential throughout the learning process.

3.6. Multimodal Sentiment Classification Module

Following the extraction of the feature representation by the complementary reconstruction module, a subsequent process involves late feature fusion. This step concatenates , and , followed by processing these predictions through a softmax layer to derive the final prediction result, denoted as y. Layer normalization (LN) is applied in this context.

For the majority of approaches to multimodal sentiment analysis, the prevalent practice involves employing cross-entropy as the primary loss function during model training. In our specific case, the training process for the model involves the minimization of the cross-entropy loss through the application of the Adam optimization algorithm:

where N represents the count of samples for the classification task, denotes the probability distribution associated with the ultimate targeted multimodal sentiment classification.

3.7. Training Procedure

To facilitate reproducibility and provide a clear overview of the learning process, we summarize the training pipeline of CDNet in Algorithm 1. The training procedure is conducted in an end-to-end manner. In each iteration, the model accepts a batch of multimodal inputs (text, target, image) along with the generated image descriptions. These inputs are processed through the feature extraction, multimodal interaction, and complementary reconstruction modules sequentially. Finally, the model minimizes the cross-entropy loss function Equation (14) to optimize the parameters.

| Algorithm 1 CDNet Training Process | |

| Require: Dataset , Pre-trained BERT, ResNet | |

| Ensure: Trained CDNet Model parameters | |

| 1: for each batch in do | |

| 2: // Phase 1: Feature Extraction | |

| 3: Generate description D for image I using protocol [29] | |

| 4: | ▷ Text-Target features |

| 5: | ▷ Text-Description features |

| 6: | ▷ Visual features |

| 7: // Phase 2: Multimodal Interaction | |

| 8: | |

| 9: | |

| 10: // Phase 3: Complementary Reconstruction | |

| 11: | |

| 12: | |

| 13: // Phase 4: Classification and Optimization | |

| 14: | |

| 15: | |

| 16: | ▷ Cross-Entropy Loss |

| 17: Update model parameters to minimize | |

| 18: end for |

4. Experiments

This section provides the empirical evaluation of the CDNet model we propose. First, we describe the datasets and experimental setup, like baseline comparisons and hyperparameter settings. Then, we show a complete result analysis, with ablation studies that show the effect of our main ideas, in particular, adding image descriptions.

4.1. Datasets

We perform our experiments on the standard Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017 datasets introduced in [7]. These datasets are derived from tweets posted during 2014–2015 and 2016–2017, respectively, and serve as established benchmarks for targeted multimodal sentiment analysis. Each entry consists of a text–image pair along with annotated opinion targets. The task is to classify the sentiment polarity for each target into one of three categories: negative, neutral, or positive. Detailed statistics for the train, development, and test splits are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of two Twitter datasets.

4.2. Experimental Settings

For text, we chose a pre-trained BERT-base (uncased) model, and for images, we used ResNet to get visual features. Table 2 shows the exact values we picked for settings like batch size, attention heads, hidden dimensions, and learning rate. We built our models using PyTorch (version 2.9.0) and trained them using NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs provided via the Google Colab platform (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Table 2.

Settings of important parameters.

4.3. Baseline Methods

CDNet is evaluated against other established methods for targeted sentiment classification, considering both unimodal and multimodal approaches.

Unimodal methods include ResNet [30] for sentiment analysis using only images, Faster R-CNN [32] for getting visual features, AE-LSTM [33], which adds aspect embedding in attention-based LSTM frameworks, MemNet [34], which employs multi-hop memory networks with attention mechanisms, RAM [35], using GRU-based multi-hop attention for information extraction, and BERT [25] for understanding the relationship between text and target. Multimodal methods comprise MIMN [5], a multi-interactive memory network for cross-modal interactions; ESAFN [6], which focuses on targeted-sensitive attention and fusion; TomBERT [7], using multimodal BERT for understanding relationships within and between modalities; CapTrBERT [8], translating images to captions before BERT-based analysis; ARFN [36], specializing in affective region recognition and fusion; ITMSC [37], using image semantics and visual contributions for better multimodal fusion; and MPFIT [38], a multimodal method that employs prompt-based learning strategies for aspect-based sentiment classification.

4.4. Experimental Results

The quantitative results on the Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017 datasets are summarized in Table 3. We report both Accuracy and Macro-F1 scores to provide a comprehensive view of model performance.

Table 3.

Comparison of different methods on Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017. The best results for each metric are highlighted in bold.

Modality Analysis. As anticipated, text-based features produced the highest performance on sentiment classification tasks. The BERT-based text-only baselines performed at 74.15% and 68.15% accuracy for the Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017 datasets, respectively; this was significantly superior to the image-based (ResNet, Faster R-CNN) baselines which did not surpass 60% accuracy. This gap indicates the limitations of visual sentiment analysis when it is not grounded in text. However, adding additional visual information led to enhanced performance across the board. For example, applying advanced multimodal techniques such as the proposed ITMSC achieved a record 78.59% accuracy on the Twitter-2015 dataset, establishing that well-aligned visual features in conjunction with text yield additional support for the inferred sentiment of given posts.

Performance of CDNet and Comparative Analysis. CDNet was able to provide strong performance in both benchmark datasets. On the Twitter-2015 dataset, CDNet achieved a Macro-F1 score of 74.37% and an accuracy of 78.78%, exceeding the strong baseline MPFIT, which had a 77.53% accuracy. On the Twitter-2017 dataset, CDNet achieved an accuracy of 69.94% and a Macro-F1 score of 68.90%. ARFN may have slightly outperformed CDNet in terms of accuracy on this dataset. However, CDNet’s consistent performance across the multiple metrics indicates its ability to robustly process multimodal interactions. The superiority of CDNet over baselines like MIMN [5] and CapTrBERT [8] can be attributed to its unique handling of auxiliary information. Unlike MIMN, which relies on multi-hop memory networks that may struggle to align sparse text with complex images, CDNet utilizes the generated description as a direct “semantic bridge”. Furthermore, unlike CapTrBERT, which translates images entirely into text and risks losing fine-grained visual cues, CDNet retains the original visual features () while enriching them with semantic descriptions (). This dual-stream interaction ensures that the model benefits from both high-level semantic summaries and low-level visual details, resulting in more robust predictions.

Computational Efficiency Analysis. To assess the practical applicability of CDNet, we analyzed its computational overhead. Regarding inference latency, it is important to note that the image description generation is performed as an offline pre-processing step; thus, it does not affect the real-time inference speed of the sentiment analysis model. regarding the model architecture, the primary computational cost stems from the heavy pre-trained backbones (BERT and ResNet). The proposed Multimodal Interaction Module (MIM) and Complementary Reconstruction Module (CRM) consist mainly of lightweight linear transformations and attention layers, which add marginal parameter overhead. Empirically, on a single NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, the average training time is approximately 5 min per epoch. This indicates that CDNet achieves significant performance gains with only a negligible increase in computational cost compared to standard backbone-based baselines, ensuring its suitability for practical deployment.

4.5. Ablation Studies

To evaluate the influence of essential components and the impact of image descriptions within the CDNet model, a systematic ablation analysis was conducted. We compared the full CDNet model against three variants: (1) CDNet w/o MIM, where the Multimodal Interaction Module is omitted; (2) CDNet w/o CRM, where the Complementary Reconstruction Module is excluded; and (3) CRM w/o DES, a variant where the image description input is explicitly removed from the Complementary Reconstruction Module to verify its specific contribution. Table 4 provides an overview of the experimental results.

Table 4.

Ablation study results on Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017. The best results for each metric are highlighted in bold.

Based on these findings, several noteworthy observations can be made:

- The comprehensive CDNet model, incorporating all constituent modules, achieves superior performance across both datasets. Omitting any specific module leads to a noticeable decrease in predictive accuracy, underscoring the critical role of each component in achieving optimal sentiment prediction.

- The CDNet w/o MIM variant performs significantly worse than the complete CDNet. This observation underscores the pivotal role of the MIM in effectively capturing the intricate relationships between textual content, image data, and target entities. Since MIM relies on descriptions to bridge the modality gap, this drop confirms the value of the generated descriptions.

- The comparison with CDNet w/o CRM demonstrates that the integration of the reconstruction module further enhances the model’s capability to extract and preserve complementary information from different modalities, leading to a consistent improvement in performance.

- The CRM w/o DES variant exhibits poorer performance than the complete CRM. This observation is crucial as it explicitly validates the quality and utility of the generated descriptions. By removing the description input (DES) from the reconstruction process, the model loses the semantic guidance necessary to align visual and textual features effectively.

These observations collectively underscore the indispensable nature of each proposed module within the CDNet model. The interaction and synergy between these components are crucial for enhancing overall performance. Crucially, the ablation results quantitatively validate the relevance of the image descriptions; removing the description inputs (as seen in CRM w/o DES) consistently degrades performance. This integrated approach not only validates the significance of considering multiple modalities but also highlights CDNet’s robustness in harnessing the synergistic potential of both textual and visual modalities for fine-grained sentiment analysis.

4.6. Visualization Analysis

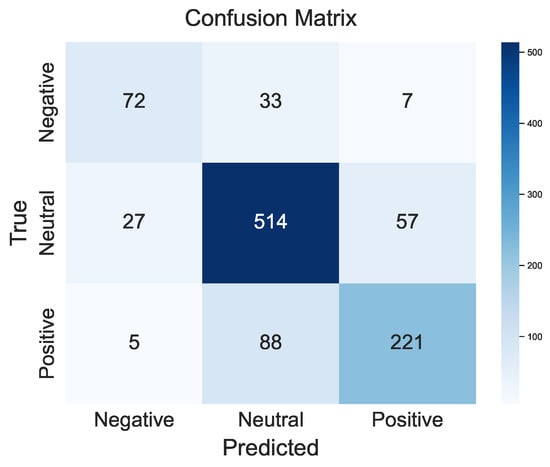

In this section, we provide a detailed visualization analysis of CDNet’s performance on the Twitter-2015 dataset. Figure 4 displays the confusion matrix, while Figure 5 illustrates the training dynamics over several epochs.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix of CDNet on the Twitter-2015 dataset.

Figure 5.

Training metric progression (Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, and Recall) across epochs.

Confusion Matrix Analysis: As shown in Figure 4, the model is proficient at classifying sentiments, especially Neutral, with 514 samples correctly identified. Looking at the classification errors provides us with a better understanding of the challenges associated with combining different types of data. The confusion matrix shows that the 88 positive instances wrongly classified as neutral often have ‘factual descriptions’. For example, if a cheering crowd is described as ‘a group of people standing’, the emotional feeling is weakened. This ‘semantic dilution’ causes the model to focus more on the objective description instead of the subtle visual sentiment, leading to a neutral bias. This suggests that while image descriptions serve as a useful semantic link, the current method might eliminate strong emotional cues. Consequently, the model sometimes struggles to differentiate between a genuinely neutral post and a positive one where the visual sentiment is subtly expressed. Future studies might benefit from utilizing description generators that comprehend sentiment to address this objective bias.

Training Dynamics. As shown in Figure 5, the model converges rapidly. The accuracy increases sharply during the first two epochs and stabilizes at approximately 0.725. Meanwhile, the F1-score shows a steady improvement, reaching 0.665 by the final epoch. Although precision and recall fluctuate slightly between epochs 4 and 5, the overall trend remains positive. The model achieves stability within a few training cycles, indicating an efficient learning process.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces CDNet, a multimodal sentiment classification framework that increases semantic richness by strategically incorporating image descriptions. Through multimodal fusion, the framework efficiently captures intricate relationships between textual content, target entities, and visual data while utilizing complementary reconstruction techniques to increase prediction robustness. Empirical evaluation on the Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017 datasets demonstrates competitive performance, achieving accuracy scores of 78.78% and 69.94% respectively. These results, supported by extensive ablation studies, confirm that augmenting textual content with descriptive visual information significantly enhances sentiment classification effectiveness. Future research will focus on developing advanced description generation and filtering strategies to reduce noise while increasing relevance across varied datasets, as well as incorporating external sentiment knowledge to improve model interpretability and lessen reliance on description quality.

Author Contributions

Methodology, B.D.; validation, J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.D. and J.A.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Jiangxi Provincial Education Reform Project (Grant No. BKJG-2026-37-9) and the Doctoral Research Fund of Gandong University (Grant No. 12225000401).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for providing their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y. CIEG-Net: Context Information Enhanced Gated Network for multimodal sentiment analysis. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 168, 111785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Sentiment analysis methods, applications, and challenges: A systematic literature review. J. King Saud-Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Kabir, M.N.; Ghani, N.A.; Zamli, K.Z.; Zulkifli, N.S.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Moni, M.A. Challenges and future in deep learning for sentiment analysis: A comprehensive review and a proposed novel hybrid approach. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, Z.; Ho, S.B.; Cambria, E. Survey on sentiment analysis: Evolution of research methods and topics. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8469–8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Mao, W.; Chen, G. Multi-interactive memory network for aspect based multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 29–31 January 2019; Volume 33, pp. 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, J.; Xia, R. Entity-sensitive attention and fusion network for entity-level multimodal sentiment classification. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2019, 28, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, J. Adapting BERT for target-oriented multimodal sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI 2019, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.; Fu, Y. Exploiting BERT for multimodal target sentiment classification through input space translation. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual Event, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 3034–3042. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.; Vishwakarma, D.K. Progress, achievements, and challenges in multimodal sentiment analysis using deep learning: A survey. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 152, 111206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zhong, G. Textgt: A double-view graph transformer on text for aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 19404–19412. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Yi, B.; Luo, L. Aspect-based sentiment analysis via bidirectional variant spiking neural P systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 259, 125295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Semary, N.; Ahmed, W.; Amin, K.; Pławiak, P.; Hammad, M. Enhancing machine learning-based sentiment analysis through feature extraction techniques. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0294968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, A.M.; Bleich, E. The advantages of lexicon-based sentiment analysis in an age of machine learning. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wankhade, M.; Rao, A.C.S.; Kulkarni, C. A survey on sentiment analysis methods, applications, and challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 5731–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligthart, A.; Catal, C.; Tekinerdogan, B. Systematic reviews in sentiment analysis: A tertiary study. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 4997–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birjali, M.; Kasri, M.; Beni-Hssane, A. A comprehensive survey on sentiment analysis: Approaches, challenges and trends. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 226, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, H.; Feng, F.; Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Hovy, E. Dual graph convolutional networks for aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), Virtual Event, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 6319–6329. [Google Scholar]

- Basiri, M.E.; Nemati, S.; Abdar, M.; Cambria, E.; Acharya, U.R. ABCDM: An attention-based bidirectional CNN-RNN deep model for sentiment analysis. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 115, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahin, M.A.; Shovon, M.S.H.; Mridha, M.; Islam, M.R.; Watanobe, Y. A hybrid transformer and attention based recurrent neural network for robust and interpretable sentiment analysis of tweets. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Teng, Z.; Zhang, Y. Inducing target-specific latent structures for aspect sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 5596–5607. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, P.; He, C.; Leung, C.W.K. Target-guided structured attention network for target-dependent sentiment analysis. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wei, W.; Mao, X.L.; Wang, F.; He, Z. BiSyn-GAT+: Bi-syntax aware graph attention network for aspect-based sentiment analysis. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.03117. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Ong, D.C. Context-guided bert for targeted aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 14094–14102. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, I.; Jung, Y.; Hockenmaier, J. SIR-ABSC: Incorporating Syntax into RoBERTa-based Sentiment Analysis Models with a Special Aggregator Token. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 8535–8550. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, T.; Li, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Qian, J. Multimodal sentiment analysis with image-text interaction network. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 3375–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zeng, Z.; Mao, W. Reasoning with multimodal sarcastic tweets via modeling cross-modality contrast and semantic association. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 3777–3786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Xue, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tian, J.; Chua, M.C.H.; Liu, M. An image-text consistency driven multimodal sentiment analysis approach for social media. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Mao, W.; Chen, G. A co-memory network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 8–12 July 2018; pp. 929–932. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (NIPS 2015), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, L. Attention-based LSTM for aspect-level sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Austin, TX, USA, 1–4 November 2016; pp. 606–615. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D.; Qin, B.; Liu, T. Aspect level sentiment classification with deep memory network. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.08900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Sun, Z.; Bing, L.; Yang, W. Recurrent attention network on memory for aspect sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–11 September 2017; pp. 452–461. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Ma, T.; Rong, H.; Al-Nabhan, N. Affective region recognition and fusion network for target-level multimodal sentiment classification. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2023, 12, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Zainon, N.W.; Mohd, W.; Hao, Z. Improving targeted multimodal sentiment classification with semantic description of images. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 75, 5801–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, F. Prompt fusion interaction transformer for aspect-based multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.