Threats to the Digital Ecosystem: Can Information Security Management Frameworks, Guided by Criminological Literature, Effectively Prevent Cybercrime and Protect Public Data?

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

- What is the current state of research in criminology for cybercrimes?

- In what ways have criminology theories been applied to understand and address cybercrime?

- How does information security literature address cybercrime prevention?

- What empirical evidence supports the integration of criminology research findings into the development of effective cybersecurity frameworks?

2. Materials and Methods

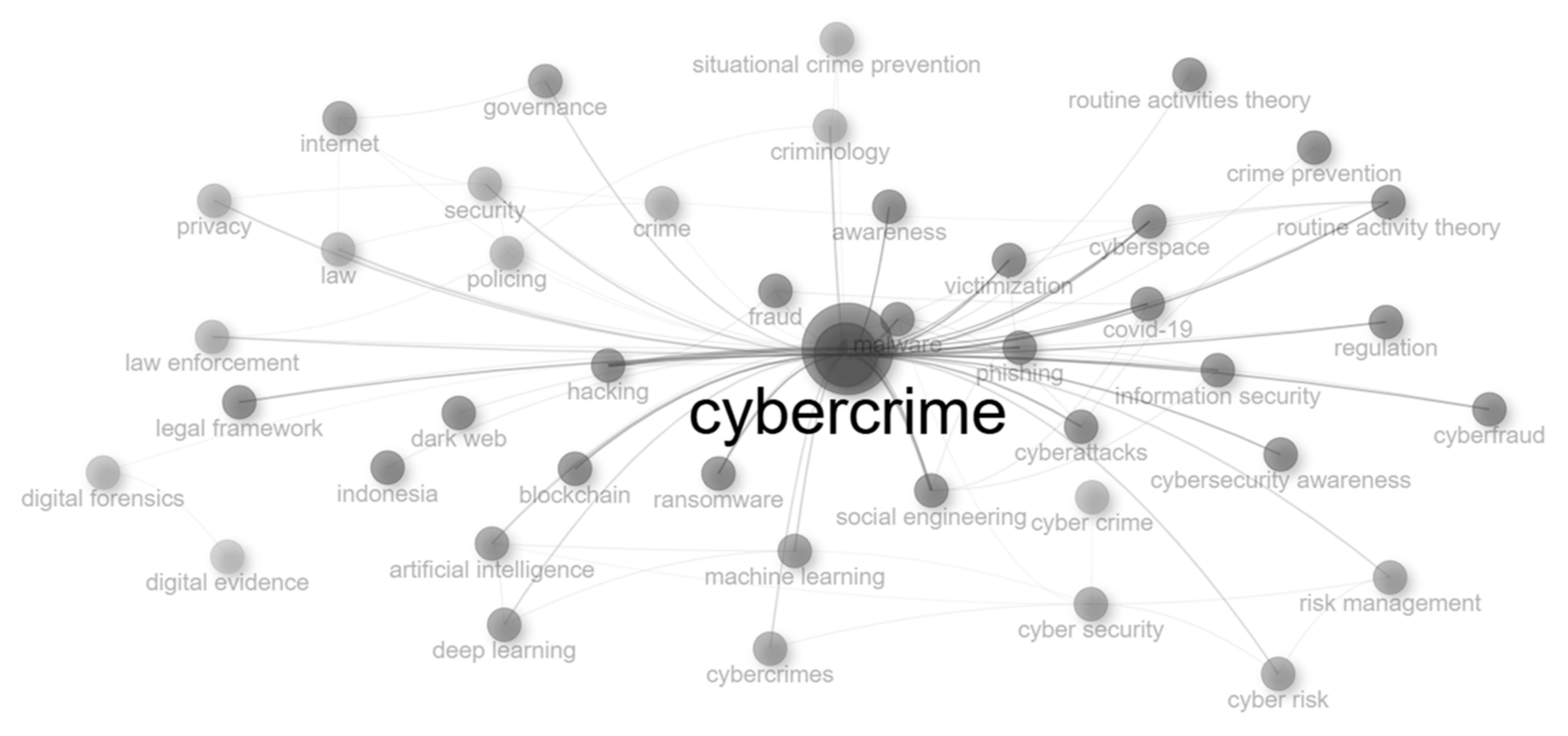

2.1. Phase 1: Bibliometric Analysis of Scholarly Literature

2.2. Phase 2: Temporal Mapping of Criminological Theories

2.3. Phase 3: Global Benchmarking Using Cybersecurity Performance Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Phase I: Bibliometric Analysis

3.2. Phase II: Theoretical Progression

3.2.1. The Rational Choice Theory (1750)

3.2.2. The Path of Least Resistance Theory (1911)

3.2.3. The Cultural Lag Theory (1922)

3.2.4. Social Learning Theory (1961–1963)

3.2.5. Deterrence Theory (1963)

3.2.6. Routine Activity Theory (1979)

3.2.7. The Situational Crime Prevention (1980)

3.2.8. The General Theory of Crime (1990)

3.2.9. The General Strain Theory (1992)

3.2.10. The Crime Pattern Theory (1998)

3.2.11. The Space Transition Theory (2008)

3.2.12. The Digital Drift Theory (2015)

3.3. Information Security Management (ISM)

3.3.1. Socio-Technical Systems Theory

3.3.2. Cybersecurity and Risk Management Framework

3.3.3. Institutional Theory

3.3.4. Integrated Framework for Information Security Management

3.3.5. Information Security Policy Compliance

3.3.6. Cybersecurity Mitigation Framework

3.4. Phase III: Cybersecurity Frameworks and Global Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Future Research Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- In, H.P.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, T.; Moon, C.-J.; Jung, Y.; Kim, I. A security risk analysis model for information systems. In Proceedings of the Systems Modeling and Simulation: Theory and Applications: Third Asian Simulation Conference, AsianSim 2004, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 4–6 October 2004; Revised Selected Papers 3. pp. 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah-Ofori, A.; Opoku-Boateng, F.A. Mitigating cybercrimes in an evolving organizational landscape. Contin. Resil. Rev. 2023, 5, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. NIST Cybersecurity Framework. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework/framework (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Harmer, G.; Williams, M. Governance of Enterprise IT Based on COBIT®5: A Management Guide, 1st ed.; IT Governance Ltd.: Ely, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, A.; Ojalade, I.; Taiwo, E.; Obunadike, C.; Oloyede, K. Cyber-Security Tactics in Mitigating Cyber-Crimes: A Review and Proposal. Int. J. Cryptogr. Inf. Secur. (IJCIS) 2023, 13, 1–20. Available online: https://airccse.org/journal/ijcis/current2023.html (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Phillips, B. Information technology management practice: Impacts upon effectiveness. J. Organ. End User Comput. (JOEUC) 2013, 25, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidat, M.A.; Obeidat, S.; Holst, J.; Al Hayajneh, A.; Brown, J. A Comprehensive and Systematic Survey on the Internet of Things: Security and Privacy Challenges, Security Frameworks, Enabling Technologies, Threats, Vulnerabilities and Countermeasures. Computers 2020, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawindaran, N.; Jayal, A.; Prakash, E. Exploration of the Impact of Cybersecurity Awareness on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Wales Using Intelligent Software to Combat Cybercrime. Computers 2022, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, B.; Holt, T. The Human Factor of Cybercrime. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2021, 40, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, B.; Holt, T.J. Advancing research on the Human Factor in Cybercrime. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 138, 107410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.J.; Dupont, B. Summarizing the special issue on the human factor in cybercrime. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 138, 107411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leukfeldt, R.; Holt, T.J. The Human Factor of Cybercrime; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pollini, A.; Callari, T.C.; Tedeschi, A.; Ruscio, D.; Save, L.; Chiarugi, F.; Guerri, D. Leveraging human factors in cybersecurity: An integrated methodological approach. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2022, 24, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, B.; Whelan, C. Enhancing relationships between criminology and cybersecurity. J. Criminol. 2021, 54, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Ko, R.; Mazerolle, L. Situational Crime Prevention (SCP) techniques to prevent and control cybercrimes: A focused systematic review. Comput. Secur. 2022, 115, 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, Z.A.; Shah, M.H.; Ahmed, J. Information security management needs more holistic approach: A literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mee, P.; Chandrasekhar, C. Cybersecurity is Too Big a Job for Governments or Business to Handle Alone; European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training (CEPOL): Budapest, Hungary, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lohrke, F.T.; Frownfelter-Lohrke, C. Cybersecurity research from a management perspective: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Gen. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Estimated Cost of Cybercrime Worldwide 2018–2029. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1280009/cost-cybercrime-worldwide (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Drew, J.M. A study of cybercrime victimisation and prevention: Exploring the use of online crime prevention behaviours and strategies. J. Criminol. Res. Policy Pract. 2020, 6, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, S. E-government, cyber-crime and cyber-terrorism: A population at risk. Electron. Gov. Int. J. 2005, 2, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil-Gil, D.; Miró-Llinares, F.; Moneva, A.; Kemp, S.; Díaz-Castaño, N. Cybercrime and shifts in opportunities during COVID-19: A preliminary analysis in the UK. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, S47–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, L.; Visschers, J.; Verstraete, C. The impact of cybercrime on businesses: A novel conceptual framework and its application to Belgium. Crime Law Soc. Change 2018, 70, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Miller, A.S.; Zhou, Z.; Warkentin, M. Does government social media promote users’ information security behavior towards COVID-19 scams? Cultivation effects and protective motivations. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abomhara, M.; Yayilgan, S.Y.; Nweke, L.O.; Székely, Z. A comparison of primary stakeholders’ views on the deployment of biometric technologies in border management: Case study of SMart mobILity at the European land borders. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, A.; Dolezel, D. Cyber-analytics: Modeling factors associated with healthcare data breaches. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 108, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M. Corruption, fraud and cybercrime as dehumanizing phenomena. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2011, 38, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuadiamu, G. Cybercrime in Criminology: A Systematic Review of criminological theories, methods, and concepts. J. Econ. Criminol. 2025, 8, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radanliev, P. Digital security by design. Secur. J. 2024, 37, 1640–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, A.; Bahuguna, P. Organizational performance as dependent variable in strategic human resource management literature–a journey so far. Benchmarking Int. J. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaure, S.; Punjabi, S. The Effect of Artificial Intelligence on Data Security Systems. In Proceedings of the Cognitive Computing and Cyber Physical Systems, Bhimavaram, India, 4–6 April 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 408–419. [Google Scholar]

- Hechter, M.; Kanazawa, S. Sociological Rational Choice Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1997, 23, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Cyber Crime, Security and Digital Intelligence; Taylor & Francis Group: Farnham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Volti, R.; William, F.O. Social Change with Respect to Culture and Original Nature; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Englewood Cliffs Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beccaria, C. On Crimes and Punishments; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reyns, B.W.; Henson, B. The Thief With a Thousand Faces and the Victim With None:Identifying Determinants for Online Identity Theft Victimization With Routine Activity Theory. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2016, 60, 1119–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, J.E. Examining Routine Activity Theory: A Review of Two Books; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, R.V.G.; Felson, M. Routine Activity and Rational Choice; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1993; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Back, S.; LaPrade, J. Cyber-situational crime prevention and the breadth of cybercrimes among higher education institutions. Int. J. Cybersecur. Intell. Cybercrime 2020, 3, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, K.A.; Farrington, D.P. Evaluating situational crime prevention using a young people’s survey: Part II making sense of the elite police voice. Br. J. Criminol. 2001, 41, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasmick, H.G.; Tittle, C.R.; Bursik, R.J.; Arneklev, B.J. Testing the Core Empirical Implications of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s General Theory of Crime. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1993, 30, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency*. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantingham, P.; Brantingham, P. Crime pattern theory. In Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis; Willan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 100–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jaishankar, K. Space transition theory of cyber crimes. Crimes Internet 2008, 5, 283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, A.; Brewer, R. Digital drift and the criminal interaction order. Theor. Criminol. 2015, 19, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Gilmour, J.; Mazerolle, L.; Ko, R. Utilizing cyberplace managers to prevent and control cybercrimes: A vignette experimental study. Secur. J. 2023, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatji, M.; Marnewick, A.; von Solms, S. Validation of a socio-technical management process for optimising cybersecurity practices. Comput. Secur. 2020, 95, 101846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurii, Y.; Opirskyy, I. Analysis and Comparison of the NIST SP 800-53 and ISO/IEC 27001: 2013. NIST Spec. Publ. 2022, 800, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Al-ma’aitah, M.A. Investigating the drivers of cybersecurity enhancement in public organizations: The case of Jordan. The Electronic J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 88, e12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Schmidt, M.B.; Herberger, G.R.; Pearson, J.M. An integrated framework for information security management. Rev. Bus. 2009, 30, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, G.D.; Siponen, M.; Pahnila, S. Toward a unified model of information security policy compliance. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 285–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy, e-Governance. National Cybersecurity Index; NCSI: Yokosuka, Japan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alanezi, F.; Brooks, L. Combatting Online Fraud in Saudi Arabia Using General Deterrence Theory (GDT). 2014. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2014/ICTGlobal/GeneralPresentations/12/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Okeke, R.I.; Eiza, M.H. The Application of Role-Based Framework in Preventing Internal Identity Theft Related Crimes: A Qualitative Case Study of UK Retail Companies. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.S. Integrating Criminological Theories in Cybersecurity Risk Assessment: A Study of the TRACI Framework’s Application to Critical Infrastructure. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. Ph.D. Thesis, Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, S.; Green, K.; Johnson, C.; Cooper, J.; Gilstrap, C. An Extended TOE Framework for Cybersecurity Adoption Decisions. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 47, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.W.; Welke, R.J. Coping with systems risk: Security planning models for management decision making. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 441–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.; Triplett, R. Capable guardians in the digital environment: The role of digital literacy in reducing phishing victimization. Deviant Behav. 2017, 38, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawdon, J. Cybercrime: Victimization, Perpetration, and Techniques. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 46, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, S.; Khan, N.F.; Zafar, S. Prevalence of cyberbullying victimization among Pakistani Youth. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Weijer, S.; Leukfeldt, R.; Moneva, A. Cybercrime during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence, nature and impact of cybercrime for citizens and SME owners in the Netherlands. Comput. Secur. 2024, 139, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Levi, M.; Burnap, P.; Gundur, R.V. Under the Corporate Radar: Examining Insider Business Cybercrime Victimization through an Application of Routine Activities Theory. Deviant Behav. 2019, 40, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criminological Theory | Influence on International Cybersecurity Frameworks |

|---|---|

| Rational Choice Theory | Forms the conceptual foundation for risk-based cybersecurity models by assuming rational attackers; informs risk assessments and cost–benefit analyses in frameworks like NIST and ISO/IEC 27001. |

| Deterrence Theory | Reinforces the need for enforcement, monitoring, and penalties in policy frameworks such as the Council of Europe’s Budapest Convention and GDPR enforcement mechanisms. |

| Routine Activity Theory | Shapes user behaviour-focused frameworks that emphasise continuous monitoring, user access control, and the role of digital guardianship (e.g., NIST CSF ‘Protect’ and ‘Detect’ functions). |

| Situational Crime Prevention | Informs technical control standards and secure system design principles; aligns with proactive defence strategies in frameworks like ISO 27002 and CIS Controls. |

| Social Learning Theory | Supports awareness training, behavioural analytics, and community reporting elements in national strategies like the UK’s Cyber Aware campaign and Australia’s ACSC initiatives. |

| General Strain Theory | Provides insight into the socio-economic factors driving cybercrime, influencing policy recommendations in OECD cybersecurity reports and UNODC cybercrime frameworks. |

| General Theory of Crime | Highlights the importance of individual accountability and internal governance controls in corporate cybersecurity policies and compliance standards such as PCI DSS. |

| Crime Pattern Theory | Influences threat modelling and vulnerability assessments by identifying digital behaviour patterns and common access points, adopted in frameworks like MITRE ATT and CK. |

| Space Transition Theory | Raises awareness of jurisdictional and policy challenges in cyber law by highlighting behavioural differences across spaces, used in cross-border cooperation protocols such as Interpol’s cybercrime operations. |

| Digital Drift Theory | Encourages ethical design and online platform accountability by identifying drift-related vulnerabilities; relevant to youth digital safety strategies under UNESCO and EU cybersecurity directives. |

| Framework Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deterrence Theory [54] | Situational Crime Prevention [15] | Role-Based Framework [55] | National Institute of Standards and Technology [3] | |

| Main concept | The cybercrime prevention model, based on deterrence theory, addresses various stages of cybercrime prevention, including deterrence, prevention, detection, and remediation. | It operates on five core functions: increasing efforts, increasing risk, reducing rewards, reducing provocations, and removing excuses. These fundamental functions are further expanded into 25 specific controls. | The framework is designed to clarify the distinct roles of management within organisational settings, recommending that various management levels adopt practices to mitigate identity theft within organisations. | It is a comprehensive cybersecurity framework that integrates both technological and managerial controls for cybercrime prevention. The framework offers a detailed set of recommendations for cybersecurity, encompassing both technological and managerial aspects. However, its core emphasizes the importance of identifying, protecting against, detecting, responding to, and recovering from cybercrime. |

| Utilisation | It can serve as a model for implementing practices at various stages of cybercrime mitigation within digital service settings. | Primarily focused on technological controls, this model is frequently referenced in computer science and information systems literature for the implementation of controls in alignment with international cybersecurity frameworks, such as ISO standards. | The framework outlines general management practices for consideration, but it is specifically developed and applied within organisational settings, limiting its generalizability to all digital services sectors. | Excessively detailed about technological controls, the current framework also links the implementation of each individual function to the cybersecurity framework, thereby representing it predominantly as a technological control paradigm. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mushtaq, S.; Shah, M. Threats to the Digital Ecosystem: Can Information Security Management Frameworks, Guided by Criminological Literature, Effectively Prevent Cybercrime and Protect Public Data? Computers 2025, 14, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14060219

Mushtaq S, Shah M. Threats to the Digital Ecosystem: Can Information Security Management Frameworks, Guided by Criminological Literature, Effectively Prevent Cybercrime and Protect Public Data? Computers. 2025; 14(6):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14060219

Chicago/Turabian StyleMushtaq, Shahrukh, and Mahmood Shah. 2025. "Threats to the Digital Ecosystem: Can Information Security Management Frameworks, Guided by Criminological Literature, Effectively Prevent Cybercrime and Protect Public Data?" Computers 14, no. 6: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14060219

APA StyleMushtaq, S., & Shah, M. (2025). Threats to the Digital Ecosystem: Can Information Security Management Frameworks, Guided by Criminological Literature, Effectively Prevent Cybercrime and Protect Public Data? Computers, 14(6), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14060219