Abstract

The rapid advancement of Industry 4.0 and digital transformation is significantly impacting various sectors. Enabling digital technologies, such as big data, machine learning, and the Internet of Things, is becoming increasingly prevalent in industry. However, engineering curricula often fail to keep pace with these swift changes. This study, grounded in Kolb’s experiential learning theory, investigates the integration of enabling digital technologies into final academic projects for industrial engineering students to enhance their competencies through practical experience with affordable technologies. It presents a case study on the design of access control systems using Android, NFC, and Arduino. To demonstrate the potential of this approach, two projects are highlighted: one implementing an integrated parking access control system with NFC payment, and the other focusing on appointment management for access to services. A total of 50 industrial engineering students evaluated both projects, showing a high level of interest and a desire for similar future implementations. The findings indicate that integrating Industry 4.0 technologies into final academic projects effectively bridges the gap between industry requirements and engineering education, enhancing students’ technical skills through experiential learning.

1. Introduction

Recent technological advances are driving industry towards a fourth industrial revolution, also known as Industry 4.0 [1,2]. The availability of hardware capable of storing, processing and transmitting huge amounts of data is key to the transformation of industry [3]. The interconnection of the different elements of the production process and the easy access to data in near real time allow the creation of smarter systems, in which industrial processes are conceived as automated, self-configurable and flexible [4,5,6]. Computer science concepts such as big data, machine learning, cloud computing, data management, or Internet of Things (IoT) are increasingly present in the industry [7,8].

Engineering education has a strong connection with global economic and social development [9]. It is essential for Engineer 4.0 to have solid skills in human relations, combined with knowledge of engineering sciences and contemporary industry [10,11,12]. At the same time, students must be capable of adapting to the rapid changes occurring in the sector and mastering both traditional engineering and the computational technologies inherent to Industry 4.0 [13,14]. In addition, it is crucial to address the challenge of providing access to practical experiences in real contexts related to Industry 4.0 [15,16]. The profile of engineers demanded by companies is changing, and university programs must evolve accordingly [17]. However, most current industrial engineering curricula include only one or two courses related to programming, while key Industry 4.0 topics such as cloud computing, data analytics, or IoT are often excluded [18,19,20]. Training engineering professionals requires skills for increasingly dynamic labor and social environments, supported by scientific evidence showing that knowledge is not static but constantly evolving [21,22]. Therefore, there is a need to restructure teaching programs to adapt them to the new era by: (i) adding new content, which may require eliminating or reducing outdated topics, securing financial resources to purchase equipment and prepare teaching materials; and (ii) developing and/or adapting new teaching-learning methodologies [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. These methodologies are defined as organized, formalized, and oriented procedures to achieve established learning objectives, involving the planning of the teaching-learning process and the adoption of techniques and activities that can be applied in the classroom to meet the proposed goals and make decisions critically and reflectively regarding expected learning outcomes [15,30].

Different learning models are listed in the literature [31], commonly applied in the area of engineering education [32,33], such as Kolb’s experiential learning model [34], the Felder and Silverman learning model [35], the VARK (visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic) learning model [36], or the multimedia cognitive theory of learning [37], among others. These methods could be used to better understand the different disciplines included within the Industry 4.0 framework. Specifically, Kolb’s experiential learning method fosters an environment where participants engage in personally meaningful activities [38,39], allowing the student to apply prior knowledge by developing a commitment to practice [40]. As is the case in medicine [41], when engineering students graduate, their learning process does not end; throughout their professional career they will see some of their knowledge become obsolete and they will face new problems that they will have to learn to solve. Employers increasingly emphasize skills, with problem-solving being the most in-demand [42]. Educational techniques that foster learning and problem-solving skills have proven to be at least as effective as traditional teaching methods and, for this reason, in this article the Kolb’s experiential learning model will be used, which considers learning as a process by which knowledge is created through the transformation of experience, significantly improving the learning of the students in the laboratory [43].

That said, it is common in many countries and essential in Spain for engineering students to complete a Final Academic Project (FAP) (either bachelor’s or master’s level) in their last academic year to obtain the corresponding degree. This academic work is an individual research or professional project in which students must demonstrate that they have achieved the competencies required in their degree. An FAP is an opportunity for self-education and specialization in a subject that has not been taught in the degree or has not been seen in sufficient depth. In the case of industrial engineering degrees, it is, in our opinion, fundamental for deep learning of the Industry 4.0 concepts [44,45,46,47,48,49]. According to this, the implementation of the Industry 4.0 concepts in the study plan or curriculum will help to obtain a greater knowledge about their application in the classroom. On the other hand, the student needs to move from theoretical to practical, which is why the idea of creating Industry 4.0 laboratory examples for students arises, highlighting the reflective process of learning towards practice [50,51], which is derived from students’ reflection on their experiences, leading to the development of skills and competencies that society and industry need [38].

The use of open source technology facilitates the learning/training of new technologies, allowing free access to an enormous amount of software and, to some extent, hardware resources [52,53]. The hardware used in engineering schools is expensive, which means that it is not always possible to provide students with the equipment that would be desirable. For example, an industrial Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) costs hundreds of euros, and a numerical control milling machine costs tens of thousands of euros. Due to the limited financial resources of universities, engineering students often have to share equipment, which reduces the time that each student has to interact with the machine. However, there is one device with infinite possibilities that is within the reach of almost every European student: the smartphone, which is a device that contains numerous hardware components such as cameras, gyroscopes, accelerometers, telecommunication antennas, touch panels, etc. The smartphone is the most complex IoT device with the greatest potential, not only due to the number of sensors it integrates, but also due to its ability to act as a link between different devices [54]. A smartphone alone cannot control motors or pick up signals from external sensors, but it can communicate with other devices that do have these capabilities through different communication protocols such as WiFi, Bluetooth or Near-Field Communication (NFC), among others.

On the other hand, low-cost electronic components can be a perfect complement to a smartphone, enabling a wide range of simple automation projects. When a smartphone is connected to a microcontroller board, the possibilities become virtually limitless. One of the main limitations of low-cost microcontrollers is their low processing power, which prevents them from performing complex Industry 4.0 tasks such as machine learning or computer vision. However, by leveraging the computational power of a smartphone, these limitations disappear. Several industry-related projects have demonstrated positive results using a smartphone as the backbone. For instance, a real-time light monitoring system applicable to industry was proposed in [55], a smartphone-controlled unmanned aircraft system was developed in [56], and the feasibility of using smartphone sensors to quantify productive cycle elements in industrial cable logging operations was demonstrated in [57].

Considering these aspects, this paper proposes the development of Final Academic Projects that integrate open-source technologies, low-cost electronic devices, and a web-based system architecture. The approach leverages the processing capabilities of students’ smartphones to enhance Industrial Engineering education in alignment with Industry 4.0 principles. Grounded in Kolb’s experiential learning model, this educational strategy fosters active learning through real-world technological applications. As a case study, the paper presents the design of access control systems using Android, NFC, and Arduino, illustrated through two FAPs developed by undergraduate Industrial Engineering students. The first project implements an NFC-enabled parking access and payment system, while the second focuses on appointment scheduling and booking for controlled service access. Although this study primarily operationalizes IoT principles through NFC-based access control systems—along with limited use of edge and cloud computing—the proposed approach is adaptable to other enabling technologies such as digital twins, autonomous robotics, and cybersecurity solutions. By combining these elements, the proposal offers a scalable and practical pathway for implementing experiential learning strategies in engineering education.

To complement this technical and educational approach, an empirical study was conducted with Industrial Engineering students to evaluate their interest in the proposed methodology and to assess the usability and educational relevance of the two NFC-based prototypes. These contributions highlight the value students place on complementing their education and demonstrate how they can learn and apply Industry 4.0 concepts in a simple and cost-effective way, preparing them for their future professional development.

Based on this context, the study is guided by the following research questions:

- RQ1:

- How can low-cost open-source technologies be integrated into FAPs to foster Industry 4.0 skills?

- RQ2:

- What is the educational impact and perceived usability of these implementations among students?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the educational framework for incorporating Industry 4.0 technologies and skills. Section 3 provides a brief overview of Industry 4.0 technologies, highlighting IoT and its role in Education. Section 4 introduces some of the main low-cost technologies for academic use. Section 5 presents the proposed case study on NFC access control systems using Android and Arduino and outlines the objectives of two projects based on this approach. Section 6 reports the results of each project and demonstrates the ease of using these technologies in an academic environment. Section 7 presents the empirical study and its results, while Section 8 reflects on the educational impact, usability of the prototypes, and the development of Industry 4.0 skills, while also addressing limitations and future implications. Finally, Section 9 summarizes the conclusions of this work.

2. Educational Framework for Industry 4.0 Competencies

Preparing engineers for the fourth industrial revolution requires not only technical knowledge but also adaptive learning strategies that bridge theory and practice. This section reviews the competencies demanded by the new industrial paradigm, the main pedagogical approaches applied in engineering education, and the rationale for adopting experiential learning—specifically Kolb’s model—as the foundation of our proposal. This pedagogical framework establishes the rationale for integrating Industry 4.0 competencies into Final Academic Projects and provides the foundation for the research questions guiding this study (RQ1 and RQ2).

2.1. Competencies and Knowledge Areas for Industry 4.0

Despite the growing computerization, Industry 4.0 remains focused on people, placing new demands on workers through the integration of new organizational forms, work practices, and advanced technologies. Academia plays a fundamental role in ensuring the rapid adoption of changes and developments related to Industry 4.0. While it was once sufficient to convey highly specialized perspectives and information, today it is crucial to offer a broader view of related areas to foster effective communication across all hierarchical levels and throughout the value chain [58]. These evolving requirements underscore the need for engineering education to adapt, equipping future professionals with both technical expertise and interpersonal skills.

Engineering faculties must adapt their curricula and their teaching and learning methodologies so that students develop new skills that go beyond technical knowledge. In an increasingly connected industry, engineers cannot work in isolation; they must constantly communicate with other professionals and be able to clearly convey their ideas.

In [59], the need to align educational plans with the new industrial environment was highlighted. It emphasized that, without abandoning technical content, it is essential to promote the development of soft skills such as creativity, teamwork, and active listening. Similarly, Beagon and Bowe [60] stressed that engineering education should focus on behaviors and interactions between people rather than exclusively on technical skills. The findings of Deters et al. [61] suggest that there will always be a gap between education and industry. For this reason, engineering programs must prepare students not only with fundamental knowledge and skills but also with experiences and strategies that provide a solid foundation and enable them to adapt to change, thus minimizing that gap.

On the other hand, in [38] it is presented a road-map consisting of three pillars that outline possible changes and improvements in curriculum development, laboratory concept, and student club activities. The study emphasized the need for greater interdisciplinary collaboration and closer cooperation between universities and industry. According to [62], in Industry 4.0, workers, engineers, and managers must possess four types of competency:

- Personal competencies, understood as the ability to act in a reflective and autonomous manner, making informed decisions independently.

- Social competencies, referring to the ability to communicate effectively, collaborate, and establish social connections and structures with other individuals and organizations.

- Action-related competencies, defined as the ability to plan, organize, and implement actions effectively, applying knowledge and concepts in practical contexts to achieve the intended goals.

- Domain-related competencies, alludes to the ability to reach and use techniques, dialects, and instruments that are especially important for a business or trade area.

Several areas of knowledge have been highlighted in the literature as being of great importance for Industry 4.0 but have not been developed in depth in industrial engineering curricula. For example, in [63] it was stated that computer skills would be needed for all types of future employment, not just industry jobs, and highlighted the important role of computer infrastructure design, programming, electronic measurement and control principles, and data science. In [64] the importance of mathematics, computer science, natural sciences, and data analysis was stressed. The study also suggested that digitization of the educational environment could facilitate the transition to the new industry.

2.2. Pedagogical Approaches for Engineering Education

In recent decades, numerous learning and teaching theories have emerged to support the integration of Industry 4.0 concepts and skills into engineering curricula. First, we review the classical models that have historically shaped engineering education, as summarized in [65]:

- Behaviorism: This model can be condensed into three words: stimulus, behavior, and reinforcement. It is based on applying reinforcement to encourage desired behaviors and punishment to discourage undesired ones. Education is seen as gradually building skills and information into discrete components [66].

- Cognitivism: This model understands learning as a reorganization of existing cognitive structures. It explains the acquisition of new knowledge through recombination acting on mental schemes [67].

- Cultural-historical: This approach conceives personal development as a cultural construction that occurs through interaction with others in a given culture by means of shared social activities. Every intellectual function must be explained based on its essential relationship with historical and cultural conditions [68].

- Socio-cultural: Similar to the previous model, this approach is based on accumulated knowledge of the social community and interaction between the individual and society. Learning occurs mainly through participation in activities rather than through formal instruction.

While traditional theoretical frameworks provide valuable foundations, they are insufficient to address the practical and interdisciplinary demands of Industry 4.0. Consequently, engineering education increasingly requires methodologies that emphasize hands-on experience and reflective practice. Active learning strategies—such as Project-Based Learning (PBL) [69] and Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) [70]—have proven effective in bridging the gap between theory and industrial application, particularly when supported by technological resources that replicate real-world scenarios. These strategies are rooted in experiential learning principles that advocate learning through direct experience and reflection rather than passive knowledge acquisition. Recent reviews confirm that such experiential approaches enhance student engagement, practical skills, and readiness for complex industrial environments [71,72,73,74,75]. This conceptual foundation leads to the next subsection, where we examine Kolb’s experiential learning cycle as a general framework for structuring individual learning processes in engineering education.

2.3. Experiential Learning as a Framework for Final Academic Projects

Experiential learning provides a structured approach to active and hands-on strategies in engineering education, and Kolb’s experiential learning cycle is its most widely recognized model [38,76,77,78,79,80]. This theory conceptualizes learning as a continuous process of transforming experience into knowledge through two complementary activities: (i) perceiving experience—either concrete or abstract—and (ii) processing experience—through reflection or active experimentation [81].

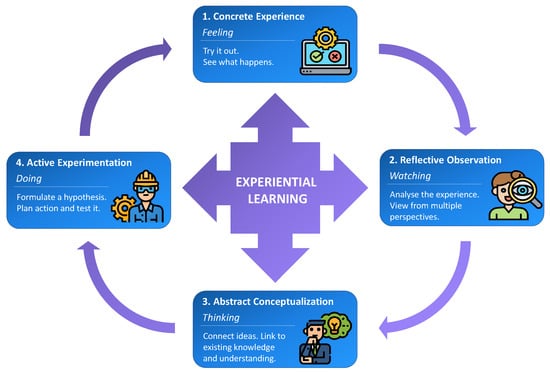

The experiential learning cycle consists of four sequential stages, which can begin at any point but must all be completed for effective learning. These stages are illustrated in Figure 1 and described as follows:

Figure 1.

Proposed learning strategy based on the Kolb and the experiential learning models.

- Concrete experience: Immediate and specific experiences that initiate observation. Learners engage in an activity and recall how they felt during the process.

- Reflective observation: Reflection on the experience to analyze outcomes, generate alternatives, and deepen understanding.

- Abstract conceptualization: Development of generalizations and conceptual models based on reflection, enabling pattern recognition and knowledge organization.

- Active experimentation: Application of new concepts in different contexts to validate and refine understanding, focusing on functional goals and improvement.

In recent years, several initiatives have introduced Industry 4.0 concepts into engineering education through experiential learning approaches. For example, in [82] it is proposed a model for CAD interoperability using a social network-based educational platform and a learning factory. Similarly, in [83], remote laboratories for automation and process control are validated, while in [84] immersive environments for software engineering were demonstrated. Challenge-based learning cases integrating collaborative robotics and real-time dashboards further illustrate how experiential design nurtures digital competencies [70].

While methodologies such as PBL and CBL operationalize experiential principles mainly through teamwork and open-ended challenges, Kolb’s model provides a more general and adaptable structure for individual learning. Given that Final Academic Projects are mandatory and individual, our approach applies Kolb’s cycle directly rather than adopting collaborative experiential strategies. The proposed framework leverages low-cost and open-source technologies—such as smartphones, Arduino boards, NFC modules, and web server architectures—to create realistic scenarios that foster hands-on practice without imposing significant financial burdens. This approach promotes autonomy and iterative learning, enabling students to acquire technical skills through experimentation while developing adaptability for future professional contexts. Furthermore, this strategy requires no curricular changes, offering an immediate and cost-effective pathway to integrate emerging technologies into engineering education. This aligns with recent research advocating experiential strategies in Logistics 4.0 and Industry 4.0 contexts [47], reinforcing the relevance of affordable, hands-on methodologies to bridge academic training and industrial practice.

3. Industry 4.0 Technologies

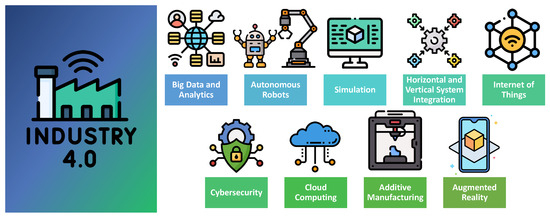

The transition from Industry 3.0 to Industry 4.0 is taking place through the adoption of new technologies by industry [85]. According to Boston Consulting Group [86], there are 9 key technologies that are transforming the industry, making production processes faster, more flexible and efficient. These technologies, shown in Figure 2, are listed next:

Figure 2.

Industry 4.0 technologies.

- Big Data and Analytics: In Industry 4.0 every element of the production process is a source of data, and the analysis of that data can guide decision making and can allow the creation of systems that self-regulate in real time, thereby improving product quality and process efficiency.

- Autonomous Robots: Advances in robotics allow robots to perform increasingly complex tasks and rely less and less on human workers to make decisions.

- Simulation: Traditionally, when a system, machine or production process was to be tested, a physical model was built. With increasingly powerful computers, it is possible to create a digital twin [87,88,89,90,91,92] to replace the physical model, which allows more tests to be performed in less time, thus achieving better quality products more efficiently.

- Horizontal and Vertical System Integration: Data sharing between different points in the value chain is key in Industry 4.0; the greater the flow of data, the greater the degree of cohesion between departments, factories, and companies [93].

- The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT): The connection of sensors and other production and control elements to a network allows a greater degree of automation and interaction between devices. This also helps to implement solutions for the safety and well-being of workers [94].

- Cybersecurity: In Industry 4.0, production systems are highly connected, making them more vulnerable to a computer attack. As exposure to the outside world increases, the security of information and communication systems must increase.

- The Cloud: The processing and storage of data on servers becomes a necessity when data sharing goes beyond company boundaries.

- Additive Manufacturing: In an industry characterized by flexibility, additive manufacturing technologies such as 3D printing make it possible to produce small batches of customized products.

- Augmented Reality: Augmented reality can provide real-time information to workers to facilitate their work or can even be used for virtual training [95].

Among these technologies, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) stands out for its role in enabling connectivity and automation across industrial systems. This relevance makes IoT the cornerstone of the case study presented in this paper.

Internet of Things in Education

The Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the most influential enabling technologies in Industry 4.0. It offers unprecedented opportunities for connectivity, data acquisition, and automation. In educational settings, IoT facilitates experiential learning by allowing students to interact with real-time data and develop solutions that mirror industrial practices. Its integration into engineering curricula promotes active learning, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the acquisition of digital competencies essential for modern industry.

Recent studies highlight the pedagogical potential of IoT-based projects. For instance, IoT-driven initiatives have been successfully applied to sustainability education through project-based learning, enabling students to design solutions for real-world environmental challenges [96]. Similarly, citizen science projects leveraging IoT and AI forecasting have demonstrated how open data and edge computing can enhance STEM education [97]. Comprehensive reviews also emphasize the concept of the Internet of Educational Things (IoET), which advocates embedding IoT technologies into higher education to foster personalized and autonomous learning experiences [98]. Furthermore, structured programs in IoT engineering using project-based methodologies have shown significant improvements in technical and transversal skills [99].

Despite these advances, IoT adoption in education faces challenges such as infrastructure costs, data privacy, and faculty training. Security concerns are particularly relevant in decentralized IoT architectures, where open-source solutions have been proposed to mitigate vulnerabilities [100]. Likewise, comparative analyses of open-source IIoT platforms for smart factories provide valuable insights into interoperability and scalability issues that can inform academic implementations [101]. Future trends such as TinyML and edge intelligence offer promising avenues for integrating artificial intelligence into resource-constrained IoT devices, enabling more sophisticated educational applications [102,103]. The following sections exemplify these principles through NFC-enabled access control systems integrated with Arduino and Android platforms, illustrating how low-cost solutions can deliver meaningful experiential learning outcomes in FAPs.

4. Low-Cost Technologies for Academic Use

Engineering departments need to have equipment that can be used to train future engineers in Industry 4.0 technologies. However, the rapid advance of information and communication technologies means that electronic devices quickly become obsolete. For this reason, universities are reluctant to invest in expensive equipment that will lose most of its value in a few years. In this context, low-cost electronic devices are positioning themselves as an alternative to devices for professional use. Low-cost electronic devices have the capacity to recreate the operation of any industrial device, and due to their low price they can be renewed as new models are released without having to make a large financial outlay. The following subsections describe some of the low-cost electronic devices that have the greatest potential for introducing new industry 4.0 technologies in industrial engineering degrees.

4.1. Smartphones

A smartphone can be defined as a cell phone running a mobile operating system with greater computing and connectivity capabilities than a phone [104]. In education, smartphones can be seen as a distraction that hinders learning [105] or, as in our case, as a powerful educational tool with particular characteristics very useful for academic use. Virtually, any smartphone on the market can be used to implement the technologies described in the previous section with the exception of additive manufacturing. Basically, a basic smartphone usually includes the following four fundamental characteristics:

- High computational power.

- Capability to network with other devices.

- Sensors such as cameras, gyroscopes, etc.

- Display and speaker (especially necessary in augmented reality applications).

There are numerous smartphone operating systems, but the majority of smartphones on the market run the operating system Android [106] that will be described next.

4.2. Android

Android is an open source mobile operating system based on the Linux kernel, initially developed for use on smartphones and tablets, but today its use has spread to other devices such as TVs, watches or cars [107]. Android applications are written in the Java programming language [108]. There is an official development environment for Android, called Android Studio [109], which allows developing applications for all types of Android devices [110]. Using this tool, applications can be uploaded to any Android device without paying a developer fee as is the case with iOS (iPhone Operating System). For an engineering student, learning a multi-platform programming language such as Java applied to Android application development can be much more useful than learning the same language in a generic manner. A student with Java programming skills can make a program that displays something on the screen when the user performs some action with the keyboard or mouse; however, an engineering student with Java programming skills applied to Android has access to a large number of sensors and communication technologies that can be used in any area of engineering [111].

4.3. Arduino

Arduino is an open-source hardware and software platform widely used in the academic environment [112], as well as for some industrial applications [113]. Using the Arduino integrated development environment (IDE), a large number of microcontrollers can be easily programmed in C or C++ languages, allowing us to capture and process data from a wide number of sensors and control multiple actuators such as motors, lights, buzzers, etc. [114]. In addition to sensors and actuators, it is also possible to connect to an Arduino several compatible board modules that allow the main board to connect to other devices via communication technologies such as WiFi, Bluetooth, Near Field Communication, radio frequency or infrared [115]. The connection between a smartphone and an Arduino-compatible board makes it possible to combine the Arduino’s ability to capture sensor signals and control actuators with the high computational power of a smartphone, which can lead to a large number of academic projects related to Industry 4.0 [116].

Although Arduino was selected as the primary platform in this study due to its accessibility and educational adoption, other low-cost alternatives such as Raspberry Pi or ESP32 could also be considered for implementing similar solutions in future work.

4.4. NFC

NFC is a wireless communication technology that allows information to be transferred over a distance of up to 10 cm [117]. This technology enables two-way communication between two electronic devices, allowing users to perform contactless operations by simply bringing the two devices together. Although this technology has been around for more than a decade, its use did not become widespread until it began to be used as a means of payment and major smartphone manufacturers began to include this technology in their devices [118]. NFC technology can operate in the following three different modes [119]:

- Reader/Writer Mode. In this mode the NFC device can read or write data to passive devices (without own power supply) such as an NFC tag.

- Card Emulation Mode. The NFC device behaves like a smart card; this mode allows NFC-enabled devices such as smartphones to be used as credit cards or ID cards.

- Peer-to-peer Mode. Allows bidirectional communication between devices for data exchange.

5. Case Study: NFC Access Control System Using Android and Arduino

In this section we present a proposal for an FAP based on low-cost open source technologies related to Industry 4.0. The objective of the project is the development of an access management system that makes use of the technologies described in Section 4.

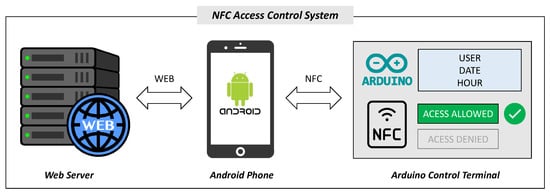

5.1. Generic Proposal Approach

Figure 3 represents the general concept of the proposed NFC access control system. The backbone of the system is a smartphone. The student has to develop an Android application that allows users to register their data on a web server that manages access to a certain establishment or service. In addition, the application must implement the use of NFC technology to interact with an Arduino device that functions as the control terminal and ultimately allows or denies entry to the user. For the implementation of the control terminal, students must design the electronic circuit using Arduino-compatible components and it will have at least the necessary hardware to allow NFC communication and display information to the user about the date, time, and access. Due to the academic nature of the proposal, advanced security mechanisms such as encrypted communications and integration with banking systems for payment applications are not considered. Instead, payment-related functionalities are simulated through a basic mechanism implemented in the database, ensuring the feasibility of the prototype while keeping the scope aligned with educational objectives.

Figure 3.

Overview of the proposed NFC access control system.

5.1.1. Web Server

To reduce complexity and focus on core learning objectives, the web server shall meet the following simplified requirements:

- Use a MySQL relational database hosted on a free web hosting service to store user information and system data.

- Implement communication between the Android application and the database through PHP scripts and the Volley library, using JSON format for data exchange.

- Apply basic security practices, including the use of mysqliprepared statements to prevent SQL injection.

- Support essential operations via HTTP requests, including:

- –

- User log in: Validate credentials and grant access to user data.

- –

- User sign up: Register new users in the database.

- –

- User data query: Retrieve stored information after authentication.

- –

- User data update: Modify existing records based on user input.

- Exclude advanced security mechanisms such as HTTPS encryption and password hashing, as these are beyond the scope of the academic proposal.

5.1.2. Android Application

The application is the link between the server and the access control system. Through a graphical user interface (GUI) designed by the student, the application allows to make requests to the server to perform queries, update data, or any other function that has been implemented. The application enables two-way communication via NFC between the smartphone and the NFC chip connected to the Arduino board. In this way, the application can send the user’s access permissions, such as the schedule in which the user can access, and it can also receive feedback from the control system.

5.1.3. Arduino Control Terminal

The Arduino-compatible components required to assemble the control terminal are listed in Table 1. In addition to these components, the student can integrate additional components to provide the terminal with new functionalities, such as LEDs to simulate events or represent different states of the system.

Table 1.

Electronic components list.

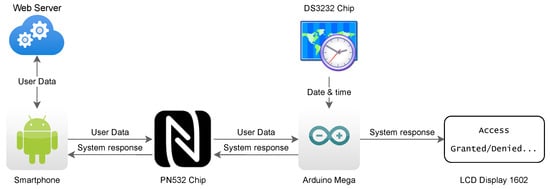

Finally, Figure 4 shows the communication diagram of the proposed NFC access control system and the basic components for the assembly of the Arduino terminal.

Figure 4.

Communication diagram of the NFC access control system consisting of Web server, Android smartphone and Arduino control terminal (main components: Arduino Mega board, PN532 NFC chip, DS3232 chip and LCD display 1602).

5.2. FAP Proposals

The previous Section 5.1 describes the FAP proposal in generic terms. Adding some conditions, two FAPs have been realized in which the access control system described above is implemented to a specific application. The problem statement of the two applications is described below.

5.2.1. NFC Access Control and Payment System for Parking

The first FAP focuses on the interaction between the user and the car park control panel, so that the user can pay the cost of the car park using their NFC-enabled mobile phone. For this purpose, certain aspects and limits are defined: (i) The car park is intended for establishments or companies, whose users will use this service on a regular basis. Consequently, users must be registered in the system to use the car park. (ii) The opening hours are set according to the opening hours of a generic commercial establishment or company, so that the car park will be open from 6:00 to 23:30. (iii) At night the car park will be closed to the public and no cars will be left inside the car park.

Considering the above, the student will have to program an Android application in which the user will enter their data and will be able to recharge a virtual wallet to pay for parking. The Android APP will be connected to a server where a database will manage the information of the parking users. In addition, the student will have to design the Arduino control terminal that will be used to register the entry and exit of the car using the user’s smartphone with NFC. Depending on the time spent in the car park, the system will determine the cost to be paid by the user. The virtual wallet will be implemented as a simple balance field in the database, updated through recharge and deduction operations when simulating payments.

5.2.2. NFC Access Control and Appointment System for Establishments

The second FAP deals with the design of a solution for customers to book an appointment and access an establishment using their smartphone with NFC. For this purpose, it is considered a generic establishment that will have the following conditions: (i) The establishment will be open from Monday to Sunday and the administrator can choose to give appointments only in the morning or in the morning and afternoon. (ii) The opening hours are from 9:00 to 14:00 and from 16:00 to 20:00 in the afternoon. (iii) Each user can only book one appointment. (iv) The establishment will only have one service available, and all available appointments will be for that single service.

To provide a solution for the establishment and address the different objectives of the FAP, the student will have to design two mobile applications for Android devices: one for the establishment’s customers and the other for the establishment’s administrator. Both applications will share information in an online database that will store customer data (which must be registered in the system), available appointments (entered by the manager) and the different bookings (made by customers from the corresponding application). The student will also have to design the Arduino control terminal that will allow or deny customers access to the establishment depending on whether they have an appointment or not. This terminal will use the NFC communication to interact with the user’s smartphone.

6. Results

This section describes the solutions proposed by the students to the problems posed in Section 5.2. Firstly, the Android application for payment in car parks using NFC is described, in which the control terminal is used to register the entry and exit of vehicles. In this project, a web server manages all the information related to the car park. Secondly, the solution designed for the problem of managing appointments and access to the establishment via NFC is presented. In this case, two Android applications are designed for the booking of appointments by customers and for the management of these appointments by the administrator. Both applications share information via web server, while the Arduino control terminal is responsible for allowing or denying access to the establishment.

6.1. Results for the NFC Access Control and Payment System for Parking

6.1.1. Android App for the NFC Parking System

The Android application or app has all the necessary functions for the user to enter data and interact with the car park’s Arduino control terminal. At the same time, the app makes use of the online database to consult and/or update information about the user and the status of the car park.

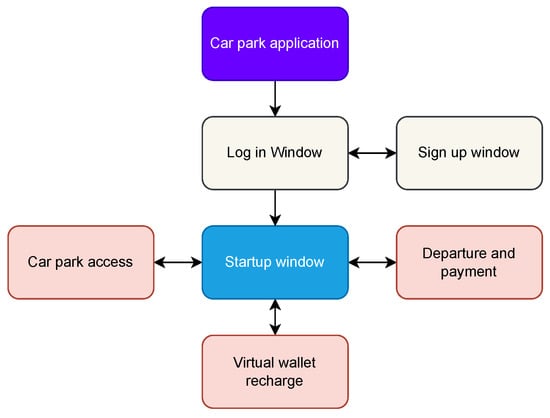

For its programming, the student uses the Android Studio IDE (Integrated Development Environment). A total of 6 main activities and layouts make up the application, and the relationship between them is graphically represented in Figure 5. From the log in window, the user can access the start-up window if they are registered in the system or the sign-up window to register. And once the user has accessed the start-up window, they have three options to access the parking lot, to pay and exit the parking lot or to add money to the virtual wallet.

Figure 5.

GUI structure of the Android app for the NFC Parking System.

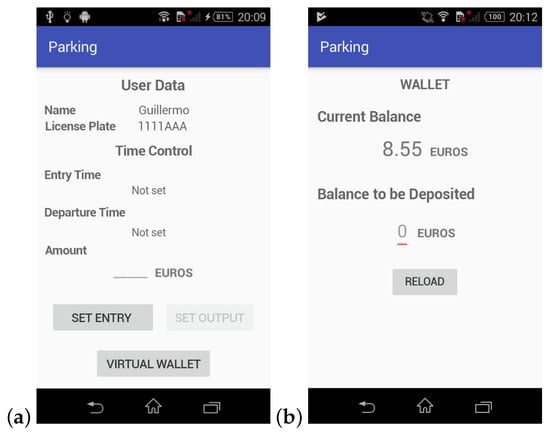

When the user arrives at the car park with their vehicle, they must set the entry and bring their Android phone close to the Arduino control terminal (click on the “Set Entry” button in the Startup window in Figure 6a). This will set the parking start time, and this information will be sent to the online database. Once the user wishes to leave the car park, they must set the exit by bringing the mobile phone close to the car park control panel (click on the “Set Output” button in the Startup window in Figure 6a). This will set the exit time, and depending on the parking time, the price that the user must pay will be determined, which will be deducted from their virtual wallet. In the event of an insufficient balance, the user will have to top up before being able to leave the car park (see Virtual wallet recharge window in Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Startup window. (b) Virtual wallet recharge window.

6.1.2. Web Server for the NFC Parking System

In terms of server programming, five functions are defined that can be called from the application. Two of these functions implement the user log in and user sign up actions described in Section 5.1.1 while the other three additional functions implement the actions user data query and user data update (see Table 2 for the information about the user data administered by the server) whose details are explained next:

Table 2.

User data managed by the server for NFC Parking System.

- Input: It is used when the user sets the entrance to the car park through the mobile application. In this case, the license plate of the vehicle and the time of entry are sent to the database, thus updating the user’s status.

- Output: It is used when the user sets the exit from the car park. For this case, the values of balance, status, entry time, and license plate are passed. The balance (after payment) and the user status with respect to the car park will be and the entry time will be reset, after payment of the parking fee.

- Recharge: It is used to check the current balance and to add money to the user’s virtual wallet.

6.1.3. Arduino Terminal for the NFC Parking System

To meet the project requirements, the student must design the Arduino control terminal and program the system to interact with the Android application via NFC. The system schematic is almost identical to Figure 4. The only difference is that, in this case, three LEDs—one red, one green, and one blue—are connected to the Arduino board. These LEDs simulate the opening and closing of the car park barrier and indicate when data is being transferred via NFC.

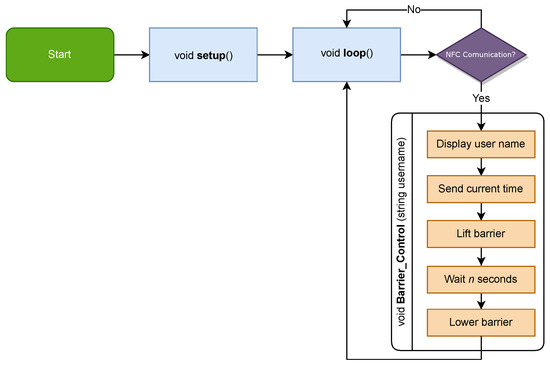

On the other hand, Arduino programming is structured into three main functions, as illustrated in Figure 7 and whose details are explained next:

Figure 7.

Simplified flowchart of the Arduino programming for NFC Parking System.

- void setup() runs once at the beginning and initializes the configuration for all electronic components.

- void loop() is the main function that runs continuously after setup(). It displays the current time on the LCD and checks for NFC communication. If no NFC device is detected, the loop repeats; otherwise, it calls Barrier_control().

- void Barrier_control(string username) manages access control. When an NFC device is detected, the Arduino displays the user’s name and current time on the LCD and sends the timestamp to the Android application for server update.

6.1.4. Experimental Tests for the NFC Parking System

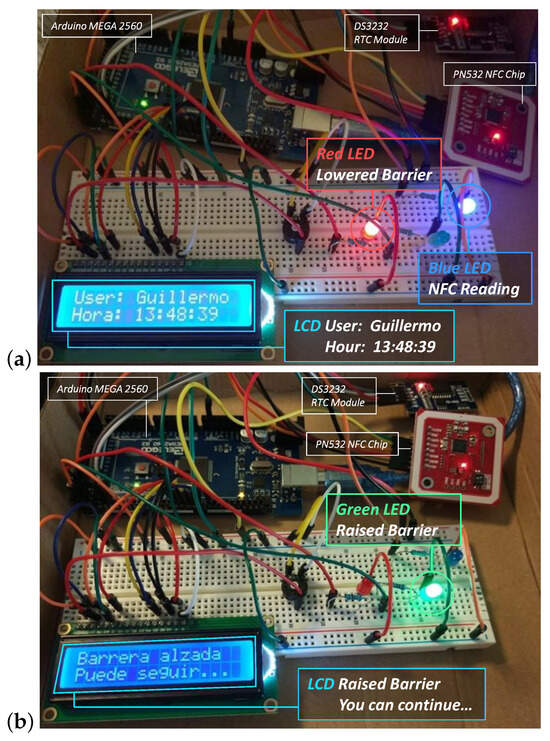

To conclude the description of the project, below are some images of the experimental setup carried out to test the operation of the NFC access control system implemented for car parks. Figure 8a shows the output of the Arduino control terminal when a user configures the entry to the parking by bringing their Android terminal close to the NFC reader. In this case, the display shows the user’s name and the current time, the red light is on, indicating that the barrier is down, and the blue light indicates that data is being transferred via NFC. Figure 8b shows the output of the control terminal when the data transfer is finished. In this case a message appears on the screen in Spanish indicating that the barrier is up, and the green light is lit indicating that the barrier is also up. The tests carried out show the correct functioning of the interaction of the Android application and the Arduino control terminal, as well as the web server that manages all the parking data. It should also be noted that in addition to the basic functions for system management, numerous exception handling functions have also been implemented to prevent system errors, such as those that would occur if communication was lost during data transmission via NFC.

Figure 8.

Experimental setup for NFC Access Control and Payment System for Parking. (a) Status of the Arduino terminal when a user brings his or her smartphone close to the NFC reader. (b) Status of the Arduino terminal when the parking barrier is raised.

6.2. Results for the NFC Access Control and Appointment System for Establishment

6.2.1. Android Apps for the NFC Access Control and Appointment System

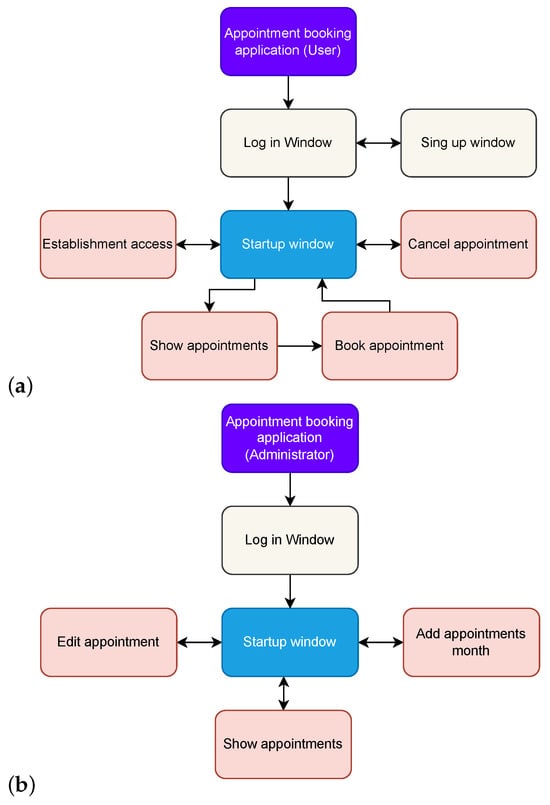

One of the main aspects of this project is how to manage appointments through an Android device, both for customers and for the administrator of the business or establishment. In this sense, it is necessary to give a solution to customers so that they can book appointments from their mobile, but also to give a solution to the administrator to be able to configure the available appointments, make queries and even modify some of them according to their needs. To this end, the student developed two different Android applications using the official Android Studio IDE: one for customers and one for the administrator, whose main activities are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

GUI structure of the Android apps for NFC Access Control and Appointment System. (a) User application. (b) Administrator application.

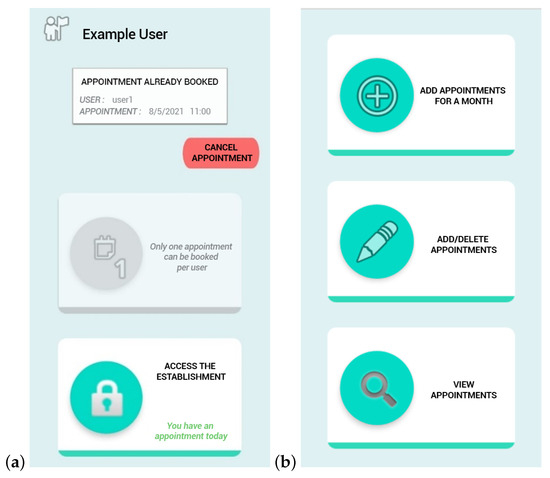

As for the Android client application or user application (see Figure 9a), once the user has logged in to the application, they access the main interface, the Startup window. In case the user is not registered in the system, they can access this option from the initial activity Log Window. Once in the Startup window, it is possible to access the window Establishment access; in this window the user is asked to bring their mobile phone close to the Arduino control terminal so that through NFC communication the control terminal receives the data and checks whether or not the user can access at that moment. It is also possible to access the window Show appointments, from which the user can view the available appointments and select the desired one. Once selected, it opens the window Reserve appointment which, as its name indicates, allows the user to reserve the selected appointment. Finally, from the Start window it is also possible to access the window that allows the user to cancel a booked appointment. Please note that depending on certain conditions, such as whether the user has booked an appointment or not, or the current day, some elements of the application will change or be inactive. For example, if the user has an appointment booked but it is not the day of the appointment, even if the user clicks the button to access the establishment, the corresponding activity will not start. Similarly, if the user has already booked an appointment, the appointment booking button will be inactive because the system only allows to have one (see Figure 10a). The user application also connects to the server, as will be detailed later, to perform the necessary queries to the online database where the establishment’s customer and appointment data are stored. To facilitate the management of these appointments by the establishment, the administrator application is designed (see Figure 9b). In this case, after logging into the system, and once in the Startup window is possible to access three modes: (i) Edit appointment, which allows to add or cancel appointments individually, (ii) Show appointments, which allows to visualize the available and booked appointments, and (iii) Add appointments month, which allows to add all the available appointments of a month automatically. For all modes (accessible from the corresponding button in the main interface, see Figure 10b), the application will connect to the online server where it will perform the necessary queries or updates to the establishment’s database.

Figure 10.

Sample of the GUI of the Android apps for NFC Access Control and Appointment System. (a) User startup window. (b) Administrator startup window.

6.2.2. Web Server for the NFC Access Control and Appointment System

In this system, the server manages a database shared by user and administrator applications, the fields of which are detailed in Table 3. For the consultation and modification of the database from the Android apps, different functions have been implemented, based on those described in Section 5.1.1. In this sense, and in addition to the functions of user log in and user sign up, the following methods have been programmed:

Table 3.

Data managed by the server in the NFC Access Control and Appointment System.

- Registration check user. It is used to check that the user name chosen is not previously reserved by a previously registered user.

- Check user appointments. Checks the database to see if the user has a booked appointment.

- Book appointments. Used by user app to add or delete citations from the database.

- Available appointments. Used to consult the database and show the user the available appointments.

- Booked appointments. Used by administrator app to consult the database for the appointments booked by the users.

- Remove appointments. Used by administrator app to remove appointments from the database.

- Add appointments. Used by administrator app to add new available appointments in the database.

6.2.3. Arduino Terminal for the NFC Access Control and Appointment System

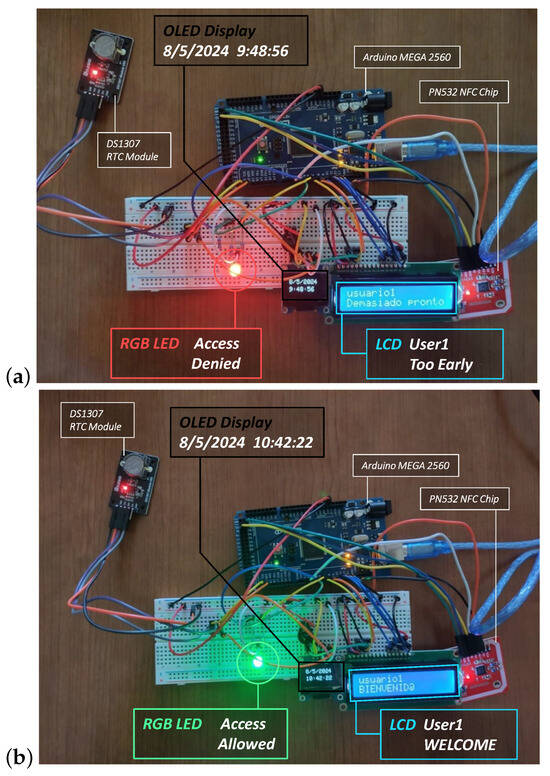

In this case, the system layout is very similar to that shown in Figure 4. The only difference is the addition of a second display to show the date and time, and an RGB LED that indicates: (i) data transmission via NFC (blue color), (ii) access denied (red color), and (iii) access allowed (green color).

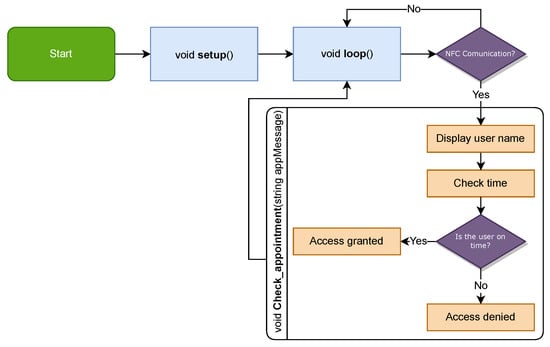

The Arduino code is similar to the one used for the car park (see Section 6.1.3), with the main difference being the function executed when the smartphone connects to the Arduino board via NFC, as illustrated in Figure 11. The void Check_appointment(string appMessage) function is responsible for displaying the name of the user who wishes to access the establishment and allowing or denying access. The function calculates the difference between the user’s arrival time and the current time; if this difference is less than a pre-established margin, access is denied, and a message is displayed indicating that the user has arrived too early or too late; otherwise, access to the establishment is allowed.

Figure 11.

Simplified flowchart of the Arduino programming for NFC Access Control and Appointment System.

6.2.4. Experimental Tests for the NFC Access Control and Appointment System

Finally, Figure 12 shows a couple of images of the set-up carried out to evaluate the operation of the designed NFC access control and appointment control system. In this case, the test consists of checking the interaction between the Arduino control terminal and the Android smartphone as follows. The user, with his appointment already booked (having selected in the app one of the appointments previously enabled by the administrator), arrives at the entrance and brings his device close to the control terminal. As mentioned above, the control terminal verifies that the user has an appointment and checks if they are within the allowed access margin. If the user is too early or too late, the terminal will display a message indicating this situation (see Figure 12a). In case the user arrives on time, the control terminal allows access (see Figure 12b). This verifies that the system is functioning as expected.

Figure 12.

Experimental setup for NFC Appointment and Access Control System. (a) Status of the Arduino terminal when a user is too late/early for their appointment. (b) Status of the Arduino terminal when a user is on time for their appointment.

7. Empirical Study

To evaluate students’ interest in the proposed methodology and to assess the usability and educational relevance of the two NFC-based prototypes described in Section 6.1 and Section 6.2, an empirical study was conducted with Industrial Engineering students. This section summarizes the study design, participants, and procedure, followed by the analysis of results.

7.1. Study Design, Participants, and Procedure

A within-subjects design was used: each participant interacted with both prototypes—(i) the access control and payment system for parking and (ii) the appointment management system—in a random counterbalanced order to reduce sequence effects. Two instruments were applied: a six-item perception questionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale and the System Usability Scale (SUS), a standardized 10-item usability measure [120].

Fifty Industrial Engineering students from the University of Castilla-La Mancha took part in the study (38 men, 12 women; mean age = 22.82 years, SD = 2.99, range = 20–37). Most were enrolled in the Bachelor’s degree program (n = 38), and the rest were pursuing a Master’s in Industrial Engineering (n = 12). All participants were native Spanish speakers and volunteered during scheduled laboratory sessions.

Sessions were conducted in a controlled laboratory environment. After a standardized introduction, each participant explored both prototypes for approximately 5 min per system. They were instructed to perform key tasks, including: (i) User registration via Android app, (ii) Virtual wallet recharge, (iii) Appointment booking, and (iv) NFC-based interaction between smartphone and Arduino terminal. After the interaction, the participants responded to the following questionnaires in Spanish using Microsoft Forms:

- A six-item perception questionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale, which included the following items:

- –

- Q1: I consider it is important for my future to be trained in key Industry 4.0 technologies such as NFC technology.

- –

- Q2: I find interesting the proposal for the realization of projects based on NFC technology using low-cost tools such as Android and/or Arduino for the improvement of the industrial engineering student’s training.

- –

- Q3: The development of projects on NFC technology integrating Arduino and/or Android is related to the contents of the course curriculum.

- –

- Q4: Developing projects on NFC technology integrating the use of smartphones and Arduino electronic circuits would complement my training.

- –

- Q5: I would like to develop a project similar to those shown in the case studies for my future thesis.

- –

- Q6: I find it technically complicated to develop the projects shown as examples in the case studies.

- System Usability Scale in Spanish, consisting of 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale [121]. The total score was converted to a 0–100 scale, where scores of 68 or higher are considered acceptable.

7.2. Analysis of the Results

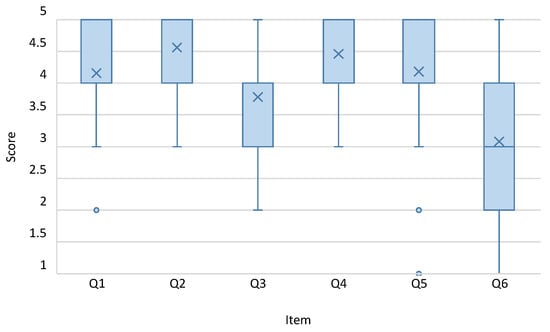

Figure 13 presents the results of the technology perception questionnaire. Participants considered training in Industry 4.0 technologies important for their future (mean = 4.2). They also found the proposed solutions interesting (mean = 4.6), believed that such projects could complement their education (mean = 4.5), and expressed interest in developing similar projects for their future theses (mean = 4.2). The connection between these projects and the current curriculum obtained an average score of 3.8 out of 5.0. Regarding perceived technical difficulty, the mean was 3.1, with a wide dispersion among participants.

Figure 13.

Box and whisker plots of the various items from the technology perception questionnaire.

Table 4 provides the mean and standard deviation for each SUS item. Both prototypes achieved overall scores slightly above the threshold of 68 (Parking system: 68.05; Appointment system: 68.20).

Table 4.

Mean or standard deviation of the different items of the SUS questionnaire.

The results reveal strong student interest in integrating Industry 4.0 technologies into Final Academic Projects, particularly NFC-based solutions using low-cost tools (Q2 mean = 4.6) and their perceived complementarity to training (Q4 mean = 4.5). However, the moderate score for curriculum alignment (Q3 mean = 3.8) suggests a perceived disconnect between these projects and formal coursework. Technical complexity (Q6 mean = 3.1) showed high variability, reflecting differences in prior programming experience. Regarding usability, both prototypes achieved SUS scores slightly above the threshold of 68, which is considered acceptable and typical for student-developed systems created under limited time and resources. These findings support the feasibility of integrating low-cost technologies into FAPs (RQ1) and demonstrate positive educational impact and usability (RQ2). A more detailed analysis of these implications is provided in Section 8.

8. Discussion

This section analyzes the main findings of the study, their implications, and limitations. The discussion is organized into five subsections: (i) pedagogical rationale and framework, (ii) integration of low-cost technologies, (iii) educational impact and usability, (iv) curricular and institutional challenges, and (v) technical limitations and future directions.

8.1. Pedagogical Rationale and Framework

Kolb’s experiential learning model was adopted because it emphasizes individual reflection and autonomy, aligning with the nature of Final Academic Projects as mandatory, individual capstone experiences. Its four-stage cycle (concrete experience → reflective observation → abstract conceptualization → active experimentation) provides a structured approach for transforming hands-on technical work into meaningful learning outcomes.

A distinctive feature of the proposal is the use of affordable, open-source technologies—such as smartphones, Arduino boards, and NFC modules—to create realistic scenarios without imposing significant financial burdens on institutions. This strategy enables students to experiment with low-cost resources while acquiring transferable skills applicable to professional environments equipped with advanced systems. In this way, the approach bridges the gap between academic practice and industrial reality, fostering adaptability and lifelong learning.

While Kolb’s model supports deep individual learning, it does not inherently promote collaborative skills, which are increasingly relevant in Industry 4.0 contexts. Future implementations may explore hybrid strategies combining Kolb’s experiential depth with Project-Based Learning to enhance both autonomy and teamwork competencies.

8.2. Integration of Low-Cost Technologies (RQ1)

The two FAPs demonstrate that a smartphone-centric architecture (Android app + web server), combined with NFC and Arduino, enables students to operationalize key Industry 4.0 concepts such as IoT connectivity, data exchange between nodes, decision automation, and cloud/edge computing using ultra-low-cost resources. Students programmed APIs and GUIs, designed circuits, integrated communication protocols, and modeled control logic in realistic scenarios, aligning naturally with Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. This distributed architecture compensates for the limited processing capacity of microcontrollers by leveraging smartphones as computational hubs, ensuring low cost and high accessibility. These results confirm the feasibility of integrating Industry 4.0 skills into FAPs without introducing new subjects or requiring major curricular changes.

8.3. Educational Impact and Usability (RQ2)

The empirical study (N = 50) revealed strong student interest in the proposed methodology (mean scores between 4.2 and 4.6 for items related to educational value and intention to replicate in future projects) and acceptable usability of both prototypes (SUS ≈ 68). In the literature, a SUS score of 68 is considered average and marks the threshold for “acceptable,” placing these prototypes within the expected range for student-developed systems. Comparison with other IoT- and Arduino-based implementations, such as the Fluid Level Monitoring and Notification System Using IoT (SUS = 54.3) and the Automatic Fish Feeding System based on Arduino Uno and Android (SUS = 72.5) [122,123], confirms that the usability levels achieved fall within the expected range for low-cost solutions.

However, the score above 3 on item 10 (“I needed to learn a lot before I could get going”) indicates cognitive load and onboarding challenges. These findings reflect two critical issues: limited attention to UI/UX design due to time constraints and the absence of human–computer interaction principles in the curriculum. Future work should include formative usability testing and pre–post skill assessments to quantify learning gains and evaluate long-term competency development.

8.4. Curricular and Institutional Challenges

Despite positive perceptions, the curriculum disconnect (mean = 3.8) suggests students do not fully associate these projects with formal coursework. This gap reflects the limited presence of Industry 4.0 topics in current industrial engineering programs and the persistence of traditional teaching approaches. To mitigate this disconnect, strategies such as leveraging mandatory FAPs as an immediate integration point, introducing short preparatory modules within existing courses, and providing faculty training in emerging technologies are recommended. Broader adoption also faces institutional challenges such as resource allocation for large cohorts and resistance to change in traditional curricula. While hardware costs are negligible, the hidden cost lies in time and expertise, making structured guidance and mentoring essential for scalability.

8.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Technical aspects: The prototypes prioritized functional feasibility over advanced features, omitting robust security mechanisms, comprehensive data management, and well-designed interfaces—usability was secondary to functionality. Future work should address these gaps by incorporating Industry 4.0 technologies such as AI, cybersecurity, and data analytics, together with strategies for secure communication, scalable data handling, and improved UI/UX design. Additionally, exploring lightweight AI solutions (e.g., TinyML for edge devices) and augmented reality could enhance the performance and user interaction. Beyond the NFC-based access control case study, this approach can be extended to other educational projects that integrate key Industry 4.0 technologies using low-cost solutions, thereby broadening the scope of FAPs and better preparing students for the evolving demands of industrial environments.

Methodological aspects: The study used a convenience sample of 50 students from one institution, which limits the generalizability of the results despite exceeding the usual threshold for usability testing (30 participants according to [124]). Future research should include larger and more diverse samples, apply stratified sampling (e.g., based on prior programming experience), and determine the required sample size through an a priori power analysis. It is also recommended to conduct pre–post evaluations of project developments to confirm competency acquisition and assess the effectiveness of the approach. Finally, comparing results with other IoT and HCI systems will help validate findings in broader contexts.

9. Conclusions and Future Work

This study proposed a cost-effective and scalable approach to integrating Industry 4.0 competencies into Industrial Engineering education through mandatory Final Academic Projects. By leveraging open-source technologies and affordable hardware—particularly smartphones, which offer extensive computational and connectivity capabilities—alongside Arduino boards and NFC modules, students could acquire practical skills in IoT connectivity, data exchange, and automation without requiring major curricular changes or significant financial investment. Grounded in Kolb’s experiential learning model, the approach fostered autonomy and iterative learning, bridging the gap between academic training and industrial demands.

The empirical results confirmed strong student interest in this methodology and acceptable usability of the developed prototypes. However, the study also revealed a perceived disconnect between these projects and formal curricula, highlighting the need for complementary strategies such as short preparatory modules and faculty training. Technical limitations included the absence of advanced security mechanisms, minimal attention to UI/UX design, and the lack of quantitative learning assessments. Some constraints were deliberate to maintain feasibility within the academic scope but should be addressed in future work.

Future research should prioritize four areas: (i) technological enhancements such as secure communication, improved UI, and integration of advanced Industry 4.0 tools (AI, cybersecurity, AR, TinyML); (ii) rigorous pedagogical evaluation through pre–post assessments and comparative studies; (iii) strategies for scalability and institutional adoption, including structured guidance and hybrid experiential–collaborative models; and (iv) development of new project proposals that incorporate other key Industry 4.0 technologies, such as robotics, big data analytics, and collaborative automation, to broaden the educational scope and strengthen practical competencies.

Smartphones, as versatile IoT devices, remain central to this vision: their computational power and sensor integration enable countless future project possibilities, including augmented reality, cybersecurity, and data analytics, without requiring additional equipment. By addressing these aspects, the proposed approach can evolve into a robust framework for preparing engineers to meet the challenges of Industry 4.0 in an accessible and sustainable manner. Ultimately, this approach contributes to closing the gap between academic training and industry needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.B., E.S., J.d.l.M., A.F.-C. and R.M.; methodology, L.M.B., J.L.G.-S., F.L.d.l.R. and R.M.; formal analysis, E.S., J.L.G.-S. and F.L.d.l.R.; investigation, L.M.B., J.L.G.-S. and F.L.d.l.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.B., E.S., J.L.G.-S., F.L.d.l.R., J.d.l.M., A.F.-C. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, L.M.B., J.d.l.M., A.F.-C. and R.M.; visualization, L.M.B., J.L.G.-S. and F.L.d.l.R.; supervision, L.M.B., E.S., J.d.l.M., A.F.-C. and R.M.; funding acquisition, L.M.B., J.d.l.M., A.F.-C. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIN) grant number PID2022-141978NB-I00; European Project REBBECA (Project ID: 101097224; HORIZON-KDT-JU-2021-2-RIA); and Spanish MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union “NextGenerationEU/PRTR” grant number PCI2022-135043-2. This work has also been partially supported by Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha/ESF (grant numbers SBPLY/21/180501/000030 and SBPLY/24/180225/000225). Finally, this work was also partially supported by Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha under Innovation Teaching Project “Experiential Learning in Digital Technologies for Industry 4.0 Aprendizaje experiencial en tecnologÍas digitales para la Industria 4.0”.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, N.; Gallon, R.; Palau, R.; Mogas, J. New objectives for smart classrooms from industry 4.0. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2021, 26, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ge, S.; Wang, N. Digital transformation: A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 162, 107774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, C.O.; Borges, M.A.V.; Antunes, J.A.V., Jr. Industry 4.0 as a data-driven paradigm: A systematic literature review on technologies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 570–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda-Sanchez, L.; Olivares, T.; Garrido-Hidalgo, C.; de la Vara, J.L.; Fernández-Caballero, A. Human-robot interaction in Industry 4.0 based on an Internet of Things real-time gesture control system. Integr.-Comput.-Aided Eng. 2021, 28, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda-Sanchez, L.; Garrido-Hidalgo, C.; García, A.S.; Olivares, T.; Fernández-Caballero, A. Comparison of RGB-D and IMU-based gesture recognition for human-robot interaction in remanufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 3099–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuett-Garza, H.; Kurfess, T. A brief discussion on the trends of habilitating technologies for Industry 4.0 and Smart manufacturing. Manuf. Lett. 2018, 15, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Hidalgo, C.; Roda-Sanchez, L.; Fernández-Caballero, A.; Olivares, T.; Ramírez, F.J. Internet-of-Things framework for scalable end-of-life condition monitoring in remanufacturing. Integr.-Comput.-Aided Eng. 2024, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena, J.C.; Schneider, J. Engineers, development, and engineering education: From national to sustainable community development. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2008, 33, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.N.; Blanchette, S.; Kelley, T.D.; Hohnka, M. The Crucial Need to Modernize Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Male, S.A.; Bush, M.B.; Chapman, E.S. Perceptions of Competency Deficiencies in Engineering Graduates. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2010, 16, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao Iturbe, C.; Lopez Ochoa, L.; Juarez Castello, M.; Castresana Pelayo, J. Educating the engineer of 2020: Adapting engineering education to the new century. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 9–11 March 2009; pp. 1110–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Akkari, A.C.S.; Rocha, M.F.M.d.; Farias Novaes, R.F.d. Cognitive ergonomics and the Industry 4.0. In Brazilian Technology Symposium; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Biały, W.; Gajdzik, B.; Jimeno, C.L.; Romanyshyn, L. Engineer 4.0 in a metallurgical enterprise. Multidiscip. Asp. Prod. Eng. 2019, 2, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcael, E.; Garcés, G.; Erazo, P.B.; Bastías, L. How do we teach? A practical guide for engineering educators. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 1451–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Litzinger, T.; Lattuca, L.; Hadgraft, R.; Newstetter, W.; Alley, M.; Atman, C.; DiBiasio, D.; Finelli, C.; Diefes-Dux, H.; Kolmos, A.; et al. Engineering education and the development of expertise. Eng. Educ. 2011, 100, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akşit, M. The role of computer science and software technology in organizing universities for Industry 4.0 and beyond. In Proceedings of the 2018 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, Poznan, Poland, 9–12 September 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, L. Industrial revolution-industry 4.0: Are German manufacturing SMEs the first victims of this revolution? J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2015, 8, 1512–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.M.; Mesquita, D.; Sousa, R.M.; Monteiro, M.T.T.; Cunha, J. Curriculum Analysis Process: Analysing Fourteen Industrial Engineering Programs. 2019. Available online: http://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/handle/1822/66284 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Valenzuela, J.; Smith, J.; Reece, B.; Shannon, D. Integrating Computer Programming Technologies Into The Industrial Engineering Curriculum. In Proceedings of the 2010 Annual Conference & Exposition, Louisville, KY, USA, 20–23 June 2010; pp. 15–759. [Google Scholar]

- Turns, J.; Atman, C.J.; Adams, R.S.; Barker, T.J. Research on Engineering Student Knowing: Trends and Opportunities. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 94, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaez Rojas, C.; Alomia Peñafiel, G.A.; Loaiza Buitrago, D.F.; Tavera Romero, C.A. Society 5.0: A Japanese concept for a superintelligent society. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, E.; Metternich, J.; Tisch, M.; Chryssolouris, G.; Sihn, W.; ElMaraghy, H.; Hummel, V.; Ranz, F. Learning Factories for Research, Education, and Training. Procedia CIRP 2015, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, F.; Guarin, A.; Mora, J.; Sauza, J.; Retat, S. Learning Factory: The Path to Industry 4.0. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 9, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhedasgaonkar, R.C.; Chavan, M.S.; Kubade, P.R.; Patil, S.B. Course Level PBL: An Excellent Teaching Method for Increasing Skill Levels and Learning Motivation in First Year of Engineering Students. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2020, 33, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bremgartner, V.; de Magalhães Netto, J.F.; de Menezes, C.S. Adaptation resources in virtual learning environments under constructivist approach: A systematic review. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, El Paso, TX, USA, 21–24 October 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, M.; Adair, D. Impact of PBL on engineering students’ motivation in the GCC region: Case study. In Proceedings of the 2018 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 6 February–5 April 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.Q.; Do, T.T.A. Active Teaching Techniques for Engineering Students to Ensure The Learning Outcomes of Training Programs by CDIO Approach. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xie, K.; Anderman, L.H. The role of self-regulated learning in students’ success in flipped undergraduate math courses. Internet High. Educ. 2018, 36, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloat, K.C.; Tharp, R.G.; Gallimore, R. The incremental effectiveness of classroom-based teacher-training techniques. Behav. Ther. 1977, 8, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, D. Learning Theories, A to Z; ABC-Clio ebook; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj, R.; Sharma, V. Smart Education with artificial intelligence based determination of learning styles. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 132, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konak, A.; Clark, T.K.; Nasereddin, M. Using Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle to improve student learning in virtual computer laboratories. Comput. Educ. 2014, 72, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Felder, R. Learning and Teaching Styles in Engineering Education. J. Eng. Educ. 1988, 78, 674–681. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, N. Teaching and Learning Styles: VARK Strategies; N.D. Fleming: Hong Kong, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.E.; Heiser, J.; Lonn, S. Cognitive constraints on multimedia learning: When presenting more material results in less understanding. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, S.; Kayıkcı, Y.; Gençay, E. Adapting Engineering Education to Industry 4.0 Vision. Technologies 2019, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briede, B.; Popova, N. Self-directed learning of university engineering students in context of fourth industrial revolution. In Proceedings of the 19th International Scientific Conference on Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 20–22 May 2020; Volume 19, pp. 1594–1600. [Google Scholar]