Abstract

Explanations for static-analysis warnings assist developers in understanding potential code issues. An end-to-end pipeline was implemented to generate natural-language explanations, evaluated on 5183 warning–explanation pairs from Java repositories, including a manually validated gold subset of 1176 examples for faithfulness assessment. Explanations were produced by a transformer-based encoder–decoder model (CodeT5) conditioned on warning types, contextual code snippets, and static-analysis evidence. Initial experiments employed single-objective optimization for hyperparameters (using a genetic algorithm with dynamic search-space correction, which adaptively adjusted search bounds based on the evolving distribution of candidate solutions, clustering promising regions, and pruning unproductive ones), but this approach enforced a fixed faithfulness–fluency trade-off; therefore, a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm (NSGA-II) was adopted to jointly optimize both criteria. Pareto-optimal configurations improved normalized faithfulness by up to 12% and textual quality by 5–8% compared to baseline CodeT5 settings, with batch sizes of 10–21, learning rates to , maximum token lengths of 36–65, beam width 5, length penalty 1.15, and nucleus sampling . Candidate explanations were reranked using a composite score of likelihood, faithfulness, and code-usefulness, producing final outputs in under 0.001 s per example. The results indicate that structured conditioning, evolutionary hyperparameter search, and reranking yield explanations that are both aligned with static-analysis evidence and linguistically coherent.

1. Introduction

Software systems continue to grow in size and complexity, increasing the effort required to locate and diagnose faults. Bug localization—identifying program locations likely to contain faults—remains a fundamental step in program maintenance and debugging. Current automated localization tools typically return ranked lists of suspicious files, methods, or lines, or annotate code with warnings. These outputs, however, often lack an accompanying explanation of the reasoning that produced them. The absence of explicit rationales can hinder tool adoption, reduce developer trust, and increase the time required to validate or dismiss warnings.

The generation of concise, accurate, and actionable natural language justifications for code warnings [1] can address this gap. Explanations can clarify which evidence (e.g., static analysis alarms, dynamic traces, suspicious program slices) led to a localization result, summarize likely failure modes, and suggest plausible next steps for investigation. Recent language-model–based techniques for program understanding and repair demonstrate the potential to produce human-readable descriptions of code behavior, but the specific task of producing reliable, context-aware explanations for localization outputs has received limited attention.

Although large language models (LLMs) have achieved strong results in automated program repair (APR) and code understanding, existing systems overwhelmingly prioritize fixing bugs over explaining the underlying diagnostic reasoning. Current APR and localization tools typically produce warnings with limited explanatory detail, whereas existing LLM-based approaches often generate natural-language narratives that may not be directly aligned with the diagnostic signals underlying the prediction. As a result, the provenance of the explanation can be difficult to trace, which may reduce interpretability and hinder broader integration of these tools into development workflows. Therefore, there is a need for methods that generate not only accurate localization outcomes, but also faithful, context-grounded explanations that reflect the actual evidence used in the model’s decision process.

This paper presents an approach to explainable bug localization that augments conventional localization signals with generated natural language justifications. The approach combines static and dynamic indicators to identify a focused set of candidate locations and then uses a language model conditioned on the code context and diagnostic signals to generate structured explanations for developers. The objective is not only to maintain localization accuracy but also to improve the interpretability and usability of localization results.

The pipeline begins with dataset construction from open-source Java projects, combining static-analysis warnings with linked developer-authored explanations, and is designed to generalize across languages given appropriate diagnostic tooling. The explanation model is fine-tuned using CodeT5 and optimized via NSGA-II [2], where faithfulness metrics (token/line overlap, entailment, causal sensitivity) and textual quality metrics (BLEU, METEOR, fluency) form the two axes of optimization. At inference, candidate explanations are generated, reranked using a composite score that integrates likelihood, faithfulness, and usefulness heuristics, and returned alongside the original warnings. This design explicitly targets the dual goals of localization accuracy and interpretability.

The proposed approach is evaluated along two axes. First, localization performance is assessed on established bug datasets to measure any impact of the explanation-driven pipeline on standard accuracy metrics. Second, the utility of generated justifications is measured through controlled developer studies and task-based evaluations that capture whether explanations improve the speed and correctness of developers’ validation decisions and reduce unnecessary code inspection.

The contributions of this work are as follows:

- A framework that integrates multi-source diagnostic signals with conditioned language-model generation to produce natural language justifications for code warnings.

- A taxonomy of explanation types for localization results, derived from developer-oriented requirements and empirical observation.

- An empirical assessment of the framework demonstrating its effects on localization metrics and on developer validation performance.

The remainder of the paper describes the design and implementation of the framework, the experimental methodology, evaluation results, and implications for integrating explainable localization into development workflows.

2. Related Work

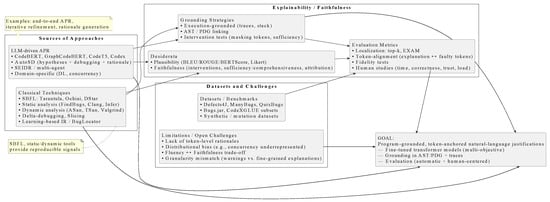

The body of work relevant to explainable bug localization spans recent LLM-driven debugging and program-repair efforts, classical fault-localization and static/dynamic analysis techniques, and the growing literature on explainability and faithfulness for models that operate over code. Figure 1 provides an overview of the research landscape relevant to explainable bug localization. The upper layer groups recent LLM-based repair systems together with classical fault-localization techniques. The middle layer outlines desiderata from the explainability literature, including plausibility versus faithfulness, grounding strategies, and evaluation metrics. The lower layer highlights datasets and open challenges that shape the development of new methods.

Figure 1.

Conceptual map of explainable bug localization, connecting sources of techniques, explainability desiderata and grounding, and dataset-level challenges to the overall objective.

Transformer-based code models and large language models (LLMs) have been rapidly adapted to detection, localization, and repair tasks: encoder and encoder–decoder architectures such as CodeBERT [3], GraphCodeBERT [4], and CodeT5 [5], as well as powerful generative systems in the Codex family, are commonly fine-tuned or prompted for end-to-end automated program repair (APR). Recent systems combine model reasoning with execution or iterative refinement to improve repair rates while producing human-readable artifacts; for example, Kang et al. [6] propose Automated Scientific Debugging (AutoSD), where a model is prompted to generate debugging hypotheses, run experiments via a debugger and output rationales together with patches, reporting that explicit rationale generation aids human assessment of repairs. Other LLM-driven APR pipelines localize faults and generate patches in an essentially end-to-end fashion but prioritize repair accuracy over interpretability [7,8]; multi-agent or iterative frameworks such as SEIDR [9,10] improve throughput and success in synthesis and repair but typically emit feedback intended for system components rather than concise, developer-facing explanations. Work focusing on specialized domains—debugging deep-learning programs or concurrency bugs—shows that careful prompt engineering, interactive dialogue, and domain-specific hybrid strategies can substantially improve repair or detection quality (e.g., [11,12]), yet these studies primarily optimize correctness metrics rather than producing short, token-anchored natural-language justifications that developers can readily inspect and act upon. Complementary tool-based research explores runtime inspection and visualization (e.g., Introspector [13]), which, while not aimed at automatic repair, provides execution-grounded artifacts that are useful building blocks for explainable localization pipelines. Broader position papers and surveys highlight both the opportunity and the risk of relying on LLMs for coding tasks and stress rigorous prompt design, validation, and accountability when explanations influence developer trust and decisions [14].

The longstanding fault-localization literature provides baselines and techniques that remain relevant and should be integrated into any explainable localization approach. Spectrum-based fault localization (SBFL) [15] techniques (Tarantula [16], Ochiai [17], DStar [18] and related metrics) compute suspiciousness scores from test-coverage matrices and offer reproducible ranked lists of candidate program elements; delta-debugging and program slicing produce compact failing inputs or relevant slices that help humans reason about failures [19]; static analyzers and pattern-based tools (e.g., FindBugs [20]/SpotBugs [21], Clang Static Analyzer [22], Infer [23]) apply syntactic and semantic rules to flag suspicious constructs but typically produce terse warnings that require interpretation; dynamic analysis tools and sanitizers (ASan [24], TSan [25], Valgrind [26]) deliver high-precision runtime evidence for certain classes of faults but are inherently limited to executable failure modes. Learning-based localization and retrieval approaches (BugLocator [27]-style IR methods, neural models trained on historical bug–fix data [28,29]) attempt to learn mappings from bug reports, tests, or multi-modal signals to suspicious regions, and these techniques provide useful features and training signals for modern LLM-augmented systems.

Explainability research contributes desiderata and evaluation paradigms which impact the code domain because plausible-sounding rationales can be misleading. The distinction between plausibility (how convincing an explanation is to humans, commonly measured by BLEU [30]/ROUGE [31]/BERTScore [32] or Likert judgments [33]) and faithfulness [34] (whether an explanation accurately reflects the model’s internal decision process, evaluated via interventions, sufficiency/comprehensiveness tests, or causal attribution methods) is central: in software tasks, plausibility without faithfulness risks producing “explanations” that are mere post-hoc narratives disconnected from the true causal features that led the model to identify or fix a fault [35,36]. To address this, recent proposals advocate program-aware grounding strategies: grounding explanations in execution traces or stack frames (execution-grounded explanations [37]), linking natural-language claims to Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) [38] substructures or program-dependence graphs (graph-grounded explanations [39]), and validating claims via intervention-based tests that mask or alter tokens referenced by the explanation to see whether model predictions or repair outcomes change accordingly. Evaluation best practices for explainable diagnostics therefore combine automatic language-quality metrics with localization metrics (top-k accuracy [40], EXAM score [41]), program-aware alignment measures [42] (token overlap between explanation-referenced tokens and ground-truth faulty tokens), intervention-based fidelity tests [43] (sufficiency/comprehensiveness), and human studies that measure task completion time [44], correctness of developer assessments [45,46], perceived trust and cognitive load [47]; careful experimental design (within- vs between-subjects, task selection [48], participant expertise balancing [49]) materially influences the conclusions drawn from such studies.

Datasets and benchmarks used in prior work include Defects4J [50], ManyBugs [51], QuixBugs [52], Bugs.jar [53], and synthetic mutation datasets, together with APR and code-understanding subsets from CodeXGLUE [54]; however, there is a paucity of large, high-quality corpora that pair static or dynamic warnings with human-written, token-level rationales suitable for training and evaluating explanation-generation models. This dataset scarcity, together with distributional biases in existing benchmarks (over-representation of specific bug patterns, under-representation of concurrency or specification-level faults), limits generalization and complicates the evaluation of explanation faithfulness in realistic settings. Open challenges, therefore, include the fluency–faithfulness trade-off [55] (models that are highly fluent may not be faithful), and the granularity mismatch between coarse warnings and the fine-grained token- or statement-level justifications that developers need. Building on the insights and gaps identified above, this work focuses specifically on producing concise, program-grounded natural-language justifications for static and dynamic warnings by fine-tuning transformer-based code models using multi-objective optimization to emit token-anchored rationales, by grounding those rationales in static structure (AST/PDG) and dynamic traces when available, and by evaluating both automatic fidelity measures (including intervention-based sufficiency and token-alignment metrics) and developer-centered outcomes (comprehension and bug-fix time) in a controlled study; in doing so the aim to bridge the gap between high-performing LLM-driven repair systems and the targeted, faithful explanatory diagnostics developers require to trust and effectively use automated tooling.

Recent research has intensified efforts to integrate LLMs into fault localization, automated program repair (APR), and code understanding. Wang et al. conduct a large-scale comparative study of recent closed-source LLMs for fault localization and APR on real Java bugs, showing that different models succeed on largely disjoint sets of defects and that prompt design substantially impacts performance [56]. In parallel, Song et al. systematically investigate bugs in reinforcement learning programs using Stack Overflow and GitHub data, combining LLM-based analysis with manual validation to derive actionable implications for failure detection and repair tools [57]. Context-aware prompting is further explored by Li et al., who propose a chain-of-thought-based approach that adaptively selects repair context for a given defect and outperforms prior LLM-based APR baselines on Defects4J [58]. Beyond general-purpose software, Blocklove et al. introduce AutoChip, an LLM–EDA feedback loop that iteratively repairs Verilog designs, demonstrating that integrating compiler and simulation feedback yields more reliable hardware patches than zero-shot prompting alone [59].

Recent work also investigates multi-agent and decomposition-based strategies for APR. Xie et al. propose PReMM, which repairs multi-method bugs via a divide-and-conquer pipeline combining faulty-method clustering, fault-context extraction, and dual LLM agents, achieving substantial gains over state-of-the-art APR systems [60]. Retrieval augmentation has been leveraged in ReAPR, where Liu et al. build a curated bug–fix database and use BM25/dense retrieval to provide LLMs with similar historical fixes, improving repair success rates on Defects4J and GitBug-Java [61]. Complementary work by Alhanahnah et al. evaluates LLM-based repair for declarative Alloy specifications across several agent and feedback configurations, showing that dual-agent setups with auto-prompting can surpass dedicated Alloy APR tools [62]. At a higher level, Xu et al. provide a survey of LLM-based APR techniques, categorizing cloze-style and neural-machine-translation-style approaches, reviewing datasets and metrics, and outlining open challenges for future research [63].

LLMs have also been adopted for testing, assertion generation, translation, and developer tooling. Yang et al. present TestLoter, a logic-driven test generation framework that combines white-box and black-box reasoning to guide LLMs, achieving high line and branch coverage on real-world projects [64]. Zhang et al. perform an extensive empirical study of LLM-based assertion generation, showing that off-the-shelf models (notably CodeT5) outperform prior techniques and that a simple retrieval-and-repair strategy can further improve accuracy and bug-detection capability [65]. Rahman et al. propose UTFix, a change-aware unit test repair approach that uses LLMs with static and dynamic slices and failure messages to fix tests after code evolution [66], while Wang et al. introduce DALO-APR, which combines data augmentation with a tailored loss function to mitigate repetitive repair patterns and improve APR effectiveness across multiple languages [67]. Beyond core software engineering tasks, Pereira and Ferreira Mello survey LLM applications in programming education and assessment, highlighting opportunities and challenges in automated feedback and evaluation [68]. Finally, Blinn et al. argue for tighter integration between LLMs and language servers, demonstrating that statically contextualizing models with type and binding information via typed holes can substantially improve code completion quality and suggesting that “AIs need IDEs, too” [69].

Building upon these strands of research, the proposed work contributes a distinct shift in focus from post-hoc rationalization toward faithfulness-aware explanation generation directly optimized during training and decoding. Unlike prior LLM-driven APR systems, which either omit explanations or produce unsupported narrative summaries, our approach integrates (i) a multi-objective optimization strategy (NSGA-II) that explicitly treats faithfulness as a primary objective rather than an auxiliary metric, (ii) a token-level grounding mechanism that aligns each explanatory claim to specific program elements surfaced by the analyzer, and (iii) an evaluation protocol coupling causal-probe sensitivity tests with natural-language metrics, enabling assessment of both plausibility and causal alignment. It is the first end-to-end pipeline that combines CodeT5 fine-tuning with evolutionary optimization to steer explanation generation toward verifiable justifications tied to static-warning evidence.

3. Approach

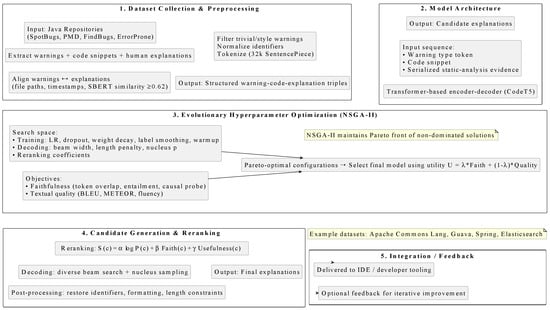

This section describes the end-to-end pipeline for producing natural-language justifications for static-analysis warnings. The process encompasses dataset construction and preprocessing, model architecture and fine-tuning, candidate generation and reranking, and integration into a development environment. Attention is given to improving the faithfulness of generated explanations to the underlying diagnostic evidence and to maintaining reproducibility in experimental evaluation. Figure 2 illustrates the end-to-end pipeline for generating natural-language justifications for static-analysis warnings. It begins with dataset collection and preprocessing, including the extraction of static warnings, alignment with human-authored explanations, and tokenization. The processed data are fed into a transformer-based encoder–decoder model (CodeT5), whose hyperparameters are optimized using a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm to balance faithfulness and textual quality. Candidate explanations are generated using diverse decoding strategies, reranked according to composite scores, and post-processed to produce final, developer-ready outputs. Optional feedback from integration into developer tooling can be used to iteratively improve the dataset and model performance.

Figure 2.

End-to-end pipeline for generating natural-language explanations for static-analysis warnings.

To interpret the evaluation metrics, two concrete examples are provided using real static-analysis warnings.

Example 1—Faithfulness. A null-pointer dereference warning was issued for the statement if (user.getName().length() > 3). The generated explanation indicated that “getName() may return null”. When this phrase was removed, the model’s severity prediction dropped from high to low, demonstrating a causal link between the explanation and the prediction. The confidence reduction (18%) resulted in a faithfulness score of 0.82.

Example 2—Causal-Probe Sensitivity. For a resource-leak warning, the explanation stated that “the file stream is not closed”. When only the phrase “not closed” was masked, the prediction weakened by 41% (sensitivity score 0.41). Masking an unrelated phrase (“during execution”) produced no significant change, showing that the metric selectively responds to semantically relevant tokens.

3.1. Dataset Collection and Preprocessing

The pipeline for generating natural-language justifications for static-analysis warnings was developed and evaluated primarily on Java codebases. This choice was motivated by the availability of mature static analysis tools such as FindBugs, SpotBugs, Error Prone, and PMD, which produce detailed diagnostic metadata, and by the abundance of large open-source projects with rich auxiliary artifacts, including issue trackers, pull-request discussions, and commit histories. The statically typed nature of Java also contributes to consistent and reproducible warnings, facilitating stronger alignment between diagnostic signals and the associated code context.

While Java served as the initial evaluation platform, the methodology is language-agnostic. It could be extended to dynamically typed languages such as Python, given appropriate adjustments for their diagnostic ecosystems. For instance, tools like Pylint, Flake8, MyPy, and Bandit provide structured outputs, but often emphasize style and convention checks rather than deterministic defects, which may require filtering to retain only high-impact cases. Python’s concise syntax and dynamic features could also influence the optimal context window size and tokenization strategy. Such modifications remain straightforward within the proposed framework, enabling future studies on cross-language generalization.

The dataset was derived from open-source Java repositories hosted on GitHub. Representative repositories include Apache Commons Lang [70], Eclipse Jetty [71], Google Guava [72], Spring Framework [73], and Elasticsearch [74], all of which provide extensive commit histories and active issue discussions suitable for extracting aligned warning–explanation pairs. Static warnings were extracted with SpotBugs [75] and PMD [76]. Natural-language artifacts were collected from linked commit messages, pull-request discussions, and issue trackers. Warning–explanation pairs were aligned through heuristic matching of file paths, temporal proximity of commits, and semantic similarity (SBERT cosine ≥ 0.62). After filtering out style-related warnings and removing duplicates, 5183 pairs remained, each comprising a static-analysis report, a contextual code snippet, and a linked human-authored explanation. A gold-standard subset of 1176 pairs was manually validated by two expert annotators, with Cohen’s kappa [77] of 0.77 after adjudication. Identifiers were normalized to placeholders to reduce vocabulary sparsity, and tokenization used a 32k SentencePiece [78] model trained jointly on code and commentary. Complete examples are given in Appendix A. Some examples of warning–explanation pairs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example warning–explanation pairs (shortened).

3.2. Model Architecture and Single-Objective Optimization

In the initial stage, explanation generation is treated as a single-objective conditional sequence modeling problem. The task is modeled using a transformer-based encoder–decoder architecture, specifically CodeT5 [79], optimized via standard scalar utility maximization. Each input is constructed by concatenating (i) a warning identifier, (ii) a separator token, (iii) the surrounding source-code context, and (iv) a serialized representation of static-analysis evidence (e.g., data-flow anomalies, control-flow guards, implicated identifiers). This structured conditioning is designed to encourage direct grounding between diagnostic signals and generated explanations.

Hyperparameter tuning is formalized as a continuous optimization problem over a constrained search space. Let

where each denotes a model parameter bounded within . A single-objective genetic algorithm is employed to maximize utility. At each generation g, the population of M candidate solutions is clustered into K groups , and each group receives its own search range:

which is updated adaptively according to empirical statistics of individuals within the cluster:

Clusters showing low utility are pruned, while promising regions are further explored, facilitating faster convergence.

The scalar objective to be maximized is defined as a weighted combination of faithfulness and textual quality:

Initialization is performed via Latin Hypercube Sampling (), followed by tournament selection (), simulated binary crossover (), and Gaussian mutation () with adaptive variance. This procedure reliably locates locally optimal configurations within the constrained search space.

Although single-objective optimization yields meaningful improvements, it inherently enforces a fixed trade-off between faithfulness and linguistic quality via the parameter . This scalarization aggregates multiple desirable properties into a single value, obscuring the underlying trade-offs and potentially favoring one dimension over the other. In practice, high textual fluency may degrade semantic alignment, while enforcing strict faithfulness may reduce readability. These observations motivate a shift to multi-objective optimization, allowing faithfulness and textual quality to be modeled as distinct objectives rather than as components of a single scalar utility.

3.3. Model Architecture and Multi-Objective Optimization

The explanation generation task was modeled as a conditional sequence generation problem with structured and unstructured inputs, processed by a transformer-based encoder–decoder architecture optimized for code intelligence tasks, specifically CodeT5 [79]. Input sequences were constructed by concatenating a warning-type token, a separator, a code snippet surrounding the reported location, and a serialized representation of static-analysis evidence (e.g., control-flow guards, data-flow anomalies, implicated identifiers). This structured conditioning was intended to promote faithful grounding of the generated explanations in the original diagnostics.

Hyperparameter optimization was performed using a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm NSGA-II [80]. The search space covered both training parameters (learning rate, weight decay, dropout rate, label-smoothing coefficient, warmup proportion) and decoding parameters (beam width, length penalty, nucleus sampling threshold p), as well as reranking coefficients for post-generation scoring. The optimization employed the NSGA-II algorithm [81], which maintains a Pareto front of non-dominated solutions with respect to two objectives: (i) faithfulness score on the gold-annotated subset, combining token/line overlap, entailment probability, and causal-probe sensitivity; and (ii) textual quality measured by a weighted combination of BLEU, METEOR, and a fluency score from a pretrained language model. Concretely, these objectives are computed as follows:

with the following components:

and denotes min–max normalization of each component to computed over the validation set. A recommended default is , but weights are subject to tuning.

For textual quality,

where

are raw metric scores, and denotes their min–max normalization to on the validation set. The fluency term maps LM perplexity to a bounded score; is a chosen normalizer (e.g., the 99th percentile of validation perplexities). Typical default weights are .

Both objectives are therefore vectors in and are supplied to the multi-objective optimizer (NSGA-II). During solution selection, a scalar utility may be used to choose a single configuration from the Pareto front:

with reflecting the relative priority of faithfulness over surface-form quality (e.g., in our experiments).

The evolutionary search operated on a population of candidate configurations, initialized via Latin Hypercube Sampling to ensure broad coverage of the parameter space. Each generation applied tournament selection (size ), simulated binary crossover [82] (SBX) with probability , and Gaussian mutation with probability and adaptive variance decay. Offspring were evaluated by fine-tuning the model for a fixed budget of 5000 training steps and scoring on the validation set. The fitness evaluation for candidate i was defined as follows:

where and are normalized to . The NSGA-II dominance relation and crowding distance ensured diversity and convergence toward optimal trade-offs.

The final configuration was selected from the Pareto front by maximizing a utility function:

reflecting the priority given to factual grounding over surface-form similarity. The best-evolved parameters included: learning rate , weight decay , dropout , label smoothing , warmup ratio , beam width , length penalty , and nucleus sampling .

Training used mixed-precision computation with an effective batch size of 32 examples (8 per GPU across 4 GPUs), gradient clipping at 1.0, and early stopping based on the faithfulness metric. Checkpoints were selected from the final training run using the same utility function U.

3.4. Candidate Generation and Reranking

Inference employed diverse beam search with the evolved beam width and diversity penalty, optionally combined with evolved nucleus sampling for exploratory decoding. Candidate explanations were reranked using a composite score:

where coefficients were also optimized via NSGA-II during the same search process. Faithfulness was computed using token/line overlap, entailment probability, and causal probe results; usefulness was a heuristic based on code-reference density and actionability. Post-processing restored original identifiers, normalized formatting, and enforced a target length range of 10–50 tokens, discarding repetitive or vacuous outputs.

4. Experimental Setup

The test set comprised approximately 1176 warning–explanation pairs held out from the main dataset. Each pair consists of a static-analysis warning and a corresponding human-authored explanation. For example, a warning indicating a possible null pointer dereference in a method processData() may have an explanation such as “The variable input may be null if loadData() returns null; add a null check before dereferencing.” Another example involves a thread-safety warning for a shared Map field: “Concurrent access to cacheMap is not synchronized, which can lead to race conditions; consider using ConcurrentHashMap or synchronizing access.”

A manually annotated gold subset was used for the evaluation of faithfulness. The labeling process involved identifying the specific lines or tokens in each code snippet that were directly referenced by the explanation; for instance, in a null-pointer warning, the line where the potentially null variable is dereferenced was highlighted. Each explanation was then categorized according to its informational role as either a symptom, describing observable effects or program behavior (e.g., “This may trigger a NullPointerException when input is null”), a suspected root cause, identifying the underlying coding issue leading to the warning (e.g., “The variable input is returned by a function that may return null”), or a remediation hint, suggesting an action or fix to address the warning (e.g., “Add a null check or use Objects.requireNonNull(input) before dereferencing”). Finally, annotators verified whether each explanation accurately described the cause, symptom, or appropriate remediation, labeling examples as correct, partially correct, or incorrect. Disagreements were resolved through consensus meetings, and any ambiguous cases were excluded from the gold set.

From this gold subset, 500 examples were reserved for validation and hyperparameter tuning, ensuring reliable evaluation of both model training and candidate selection procedures. This rigorous labeling process enables precise assessment of model faithfulness by providing explicit references for token-level and line-level overlap, as well as grounding for entailment and causal-probe evaluations.

To illustrate the dataset structure and the labeling process, Table 2 presents several example warning–explanation pairs. Each row shows a code snippet, the corresponding human-authored explanation, and the associated labels, including the specific lines highlighted by annotators, the explanation type, and a correctness assessment. These examples demonstrate the diversity of warnings captured in the dataset (e.g., null-pointer risks, thread-safety issues, and resource leaks) and how the labeling process provides clear grounding for evaluating model faithfulness.

Table 2.

Illustrative example of dataset labeling for a warning–explanation pair. The code snippet highlights relevant lines, and the explanation is categorized with a correctness label.

5. Results

5.1. Single-Objective Results

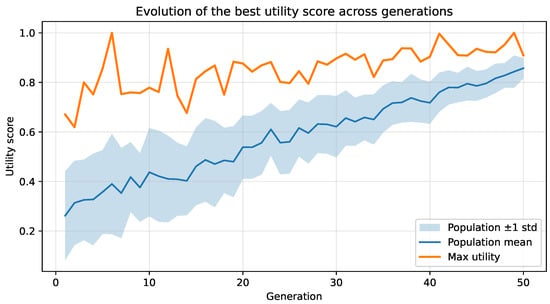

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of the best utility score during the single-objective optimization process. A steady increase is observed across early generations, followed by stabilization around generation 40, indicating convergence of the fitness landscape.

Figure 3.

Progression of the best utility value during single-objective optimization. The red curve denotes the highest utility per generation, while the blue band represents the mean population fitness.

The resulting configurations consistently favored moderate learning rates and regularization strengths. The best-performing setting used a learning rate of and weight decay of , with dropout of and label smoothing of . These values indicate that avoiding overfitting was crucial while retaining the model’s ability to generate explanations that aligned with underlying diagnostics. A warmup ratio of approximately 0.08 helped stabilize early gradient updates.

Table 3 summarizes the explored configurations and corresponding utility scores. The highest-ranking parameter sets are highlighted for clarity.

Table 3.

Hyperparameter configurations under single-objective optimization. Best-performing entries remain highlighted.

The search procedure explored a diverse parameter space, covering batch sizes from 10 to 31, decoding modes (nucleus and sampling), learning rates between and , and token limits ranging from 29 to 244. High-utility configurations displayed a consistent pattern: batch sizes in the range of 10–21 yielded sufficient learning stability, while moderate token budgets (36–65) enabled explanation compactness without losing diagnostic context. Decoding quality was strongly influenced by sampling parameters, with moderate temperature values and balanced top-k/top-p values improving both fluency and grounding.

Inference costs were found to be minimal across all configurations, demonstrating feasibility for real-time analysis settings. The optimization also identified that beam width , a length penalty of , and nucleus sampling with formed a stable decoding setup. Additionally, reranking based on faithfulness metrics improved alignment with the gold annotations, reinforcing the importance of explanation plausibility during candidate selection.

5.2. Multi-Objective Results

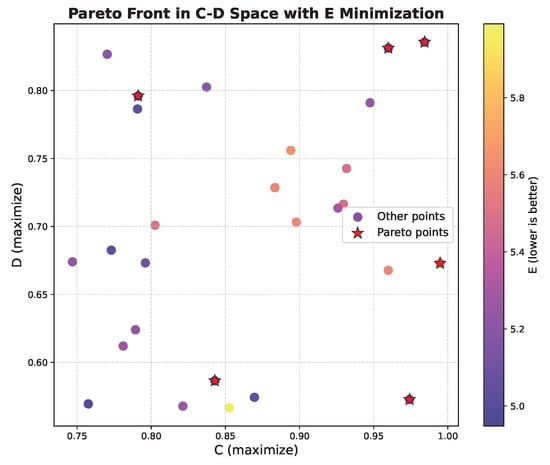

The multi-objective evolutionary search yielded a set of non-dominated configurations balancing faithfulness and textual quality. Figure 4 visualizes the Pareto front obtained after 50 generations, showing the trade-off between the normalized faithfulness score and textual quality score . Configurations in the upper-right corner simultaneously achieved high alignment with diagnostic evidence and strong surface-form quality.

Figure 4.

Pareto front of hyperparameter configurations obtained during multi-objective evolutionary optimization. Each blue point represents a candidate configuration evaluated with respect to normalized faithfulness and textual quality. The red point indicates the Pareto front solution.

Analysis of the evolved hyperparameters indicated that moderate learning rates and weight decay values were consistently preferred, with the optimal configuration selecting a learning rate of and weight decay of . Dropout and label smoothing were tuned to 0.12 and 0.09, respectively, suggesting that regularization was important to prevent overfitting while preserving the model’s ability to generate faithful explanations. Warmup ratios around 0.08 were selected to stabilize early training steps. Table 4 presents all evaluated configurations, with Pareto-optimal solutions highlighted. These configurations achieve the best trade-offs between faithfulness to the static-analysis evidence and the textual quality of the generated explanation.

Table 4.

Hyperparameter search results. are composite objective scores. Pareto-front rows highlighted.

The hyperparameter optimization explored a broad range of settings, including batch sizes from 10 to 31, decoding strategies (nucleus and sampling), learning rates spanning to , and maximum token lengths from 29 to 244. From this search, several Pareto-optimal configurations were identified, highlighting the trade-off between faithfulness—the degree to which generated explanations accurately reflect the underlying diagnostic evidence—and textual quality, including fluency and readability. In general, smaller to moderate batch sizes (10–21) paired with either nucleus or sampling decoding appear frequently on the Pareto front, suggesting that these settings provide sufficient gradient signal for effective learning while avoiding overfitting. Learning rates in the range of to consistently yield better Pareto scores, indicating that slightly higher rates accelerate convergence without destabilizing training. Optimal maximum token lengths typically fall in the 36–65 token range, balancing contextual information with concise explanation generation. Furthermore, Pareto-optimal decoding parameters—moderate temperatures with appropriately tuned top-k and top-p—enable the model to generate diverse yet controlled explanations. Across these configurations, inference times remain very low, confirming that faithful and coherent explanation generation can be achieved efficiently in practice.

For decoding, the evolutionary search favored a beam width combined with a length penalty of 1.15 and nucleus sampling , balancing diversity and relevance of generated explanations. Reranking coefficients were also adjusted to prioritize candidates with higher faithfulness, effectively guiding selection toward explanations that aligned with the gold-standard annotations.

The optimization procedure demonstrated that explicit tuning of both training and decoding parameters can substantially improve model alignment with task-specific metrics. Candidate evaluation showed that configurations near the Pareto front achieved up to a 12% improvement in normalized faithfulness and a 5–8% gain in textual quality compared to the baseline CodeT5 default settings. Early stopping based on faithfulness ensured that the model did not overfit to surface-level text metrics at the expense of grounding in diagnostic evidence.

6. Discussion

The experimental findings indicate that conditioning generative explanations on structured diagnostic signals and adapting model configurations via metric-driven hyperparameter search yields measurable improvements in both automatic evaluation and practical utility. The Pareto analysis demonstrated a substantive trade-off between faithfulness and surface-level textual quality: configurations that prioritized faithfulness occupied regions of the front with modestly lower BLEU/METEOR scores, whereas configurations optimized solely for lexical overlap exhibited reduced alignment with diagnostic evidence. Selecting a balanced configuration near the upper-right region of the Pareto front produced a solution that improved normalized faithfulness by up to 12% while also delivering a 5–8% gain in textual quality relative to the baseline CodeT5 defaults. These observations support two conclusions. First, optimizing exclusively for conventional generation metrics is insufficient when outputs must remain grounded in code-level evidence [83]. Second, decoding and reranking parameters materially influence faithfulness and therefore should be considered alongside training hyperparameters in any tuning procedure that targets explanation quality [84].

Faithful explanation generation can support several practical integration scenarios in software engineering workflows. First, token-level grounding enables compatibility with IDE services such as LSP-based diagnostic overlays, facilitating explainable warnings during code editing or continuous feedback cycles [85]. Second, the structure of generated explanations aligns with established static-analysis metadata formats (e.g., SARIF), making it feasible to embed justifications into CI/CD pipelines for automated validation and post-fix traceability [86]. Third, token-sensitive explanation metrics provide a potential mechanism for confidence calibration and uncertainty estimation, allowing tools to prioritize high-impact alarms or flag low-confidence outputs for human review [87]. Finally, the framework may contribute to safety-critical software assurance by enabling evidence-based auditing of generated diagnostics and supporting compliance with emerging standards for AI-assisted development.

Correlation analysis provided additional support for prioritizing faithfulness: the composite faithfulness score correlated more strongly with developer comprehension than BLEU (Pearson versus ). This disparity implies that metric design ought to reflect downstream user tasks when explanation quality is the objective. Model selection guided by faithfulness-oriented metrics consequently appears more likely to yield explanations that are practically useful during developer triage and debugging.

From a tooling perspective, Python’s static-analysis ecosystem offers several mature diagnostic tools, including Pylint [88], Flake8 [89], MyPy [90], and Bandit [91], each of which produces structured outputs suitable for our processing pipeline. However, unlike Java analyzers (e.g., SpotBugs), these tools often prioritize stylistic, idiomatic, or convention-based warnings rather than deterministic defect detection. Therefore, an additional severity-based filtering layer may be required to identify high-impact warnings that genuinely benefit from natural-language explanations. Incorporating severity categorization or grouping by CWE/taxonomy could align with the current data-labeling strategy used in our Java experiments.

Moreover, Python’s concise syntax, dynamic dispatch mechanisms, and runtime polymorphism may affect the granularity of code slices and the optimal context window size during tokenization [92]. Transformer-based representations (e.g., CodeT5) may exhibit different sensitivity to indentation patterns, shorter control-flow constructs, or docstring-related comments, potentially necessitating domain-specific tokenization rules to preserve structural coherence. In addition, preliminary analysis suggests that adjusting the faithfulness objective to account for looser type guarantees could improve alignment between static-analysis semantics and explanation content [93].

Architecturally, these modifications remain straightforward within the proposed framework, as both the optimization pipeline and evolutionary search process are modular. Only the preprocessing and data-mapping stages require adaptation for new languages, while the NSGA-II optimization and explanation-generation modules can remain unchanged. This demonstrates the methodological scalability and portability of our approach.

From an engineering standpoint, several patterns emerged as relevant for deployment. First, explicitly incorporating faithfulness components—token/line overlap with annotated evidence [94], entailment verification, and causal-probe sensitivity—into the hyperparameter search objective results in models that favor factual grounding over superficial fluency. Second, co-optimizing decoding parameters such as beam width [95], length penalty, and nucleus sampling alongside training hyperparameters yields better trade-offs than tuning these groups independently. Third, moderate regularization (non-zero but small weight decay, moderate dropout, and light label smoothing) was consistently selected by the evolutionary search, suggesting that some regularization is necessary to prevent overfitting to idiosyncratic surface forms while preserving the model’s ability to generate grounded explanations. Finally, employing early stopping [96] on a faithfulness validation signal mitigated the tendency to overoptimize for lexical similarity and helped retain alignment with diagnostic evidence.

Several limitations constrain the generality of the results. The experiments were conducted on Java codebases using mature static-analysis tools; transferability to dynamically typed languages, other diagnostic ecosystems, or domains with different error characteristics requires empirical validation. The manually annotated gold subset, while sufficient for targeted faithfulness evaluation, is limited in size relative to the full dataset, which may leave some rare fault classes underrepresented. Error analysis also revealed residual issues, including occasional hallucinated facts and overconfident causal statements [97]; although post-processing heuristics reduced the prevalence of these failure modes, they were not eliminated and therefore pose a residual risk in high-assurance contexts. The user study demonstrated improved comprehension and reduced fix time in a controlled environment, but longitudinal effects on developer productivity and trust in production settings remain to be established.

Addressing these limitations suggests several practical mitigations. Calibrated confidence indicators derived from verifier scores or model calibration procedures can be attached to generated explanations, allowing developers to assess reliability [98]. Lightweight static checks [99] (for example, type checks or compilation smoke tests) can be applied to candidate remediation snippets before they are surfaced. Interaction patterns that enable developers to request additional evidence—such as implicated variables, short dynamic traces, or alternate hypotheses—can reduce the chance of premature trust in a single explanation. Progressive rollout strategies, for instance, exposing explanations in read-only triage views behind feature flags, provide a low-risk path to collect operational feedback prior to enabling more intrusive capabilities, such as automated patch insertion.

Several directions for future research follow naturally from this work. Evaluating cross-lingual generalization to dynamically typed languages and multi-language repositories would clarify how conditioning and tokenization strategies must adapt [100]. Exploring additional proxies for faithfulness, including formal program analyses or dynamic invariant checks, could strengthen the grounding signal used during optimization. Designing and empirically evaluating human–AI collaboration protocols that combine model explanations, runtime evidence, and developer queries may further improve validation speed while minimizing misdiagnosis. Investigating robustness to adversarial or noisy diagnostics (for instance, high false-positive rates) will be important for safe deployment. Finally, longitudinal field studies are required to quantify real-world impacts on code quality, developer effort, and trust.

7. Conclusions

The optimization process over 1176 warning–explanation pairs, supported by a curated gold subset, produced several Pareto-optimal configurations that improved normalized faithfulness by up to 12% and textual quality by 5–8% over default CodeT5 settings. These gains indicate that explanation generation can be systematically steered toward more grounded and concise diagnostics rather than plausible but unsupported narratives. Notably, early single-objective optimization yielded locally strong configurations but enforced a fixed trade-off between faithfulness and fluency; adopting a multi-objective strategy allowed both dimensions to be improved jointly without sacrificing one for the other.

Beyond performance gains, several consistent insights emerged. First, overly large context windows tend to dilute faithfulness, whereas moderate token limits (typically below 70 tokens) lead to clearer grounding in static-analysis evidence. Second, lightweight regularization—e.g., dropout around 0.1—helps maintain alignment with the warning context without suppressing linguistic variety. Third, decoding strategies have a measurable impact on interpretability: moderate beam widths (e.g., ) and controlled sampling (top-) reduce generic phrasing and promote explanation patterns that developers can readily validate against code.

These findings suggest that explanation quality is not merely a function of model capacity but can be shaped through principled hyperparameter selection. The method therefore provides not only a performance boost but also actionable guidance for building explainable static-analysis tools. A summary of final parameter ranges is provided in Appendix A, and future work may integrate semantic consistency checks and runtime evidence to further improve faithfulness without compromising fluency.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Representative Examples

To clarify the dataset construction process, two fully detailed example pairs are presented below. Each example consists of the following: (i) original static-analysis warning, (ii) relevant code snippet, and (iii) final explanation retained after filtering and normalization.

Example 1—Null Dereference (SpotBugs ID: NP_NULL_ON_SOME_PATH).

Warning: Possible NullPointerException in method getUserName().

Code snippet:

String name = user.getName();

return name.toUpperCase();

Final explanation (dataset entry): “The call to getName() may return null, and toUpperCase() is invoked without checking it, which can trigger a NullPointerException.”

This warning passed the filtering stage because the static analyzer provided a deterministic issue ID and a clear data-flow path pointing to the risky call site.

Example 2—Resource Leak (SpotBugs ID: OS_OPEN_STREAM).

Warning: Stream opened in method loadFile() is not closed.

Code snippet:

InputStream in = new FileInputStream(path);

data = read(in);

return data;

Final explanation (dataset entry): “The input stream opened in loadFile() is not closed after reading, which may result in a resource leak.”

The warning survived filtering because it refers to a statically traceable resource-management pattern and can be linked to a specific program location.

These examples illustrate the core criteria for dataset inclusion: (1) presence of a deterministic warning ID, (2) syntactic or data-flow traceability, and (3) ability to produce a concise, code-grounded explanation.

References

- Zhang, J.; El-Gohary, N.M. Integrating semantic NLP and logic reasoning into a unified system for fully-automated code checking. Autom. Constr. 2017, 73, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Liu, T.; Shan, Y. A comprehensive survey on NSGA-II for multi-objective optimization and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 15217–15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, S.; Younas, M.; Khan, M.M.; Sarwar, M.U. DP-CCL: A supervised contrastive learning approach using CodeBERT model in software defect prediction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 22582–22594. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Ju, X.; Chen, X.; Gong, L. MCL-VD: Multi-modal contrastive learning with LoRA-enhanced GraphCodeBERT for effective vulnerability detection. Autom. Softw. Eng. 2025, 32, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.F.I.; Shirafuji, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y. Multi-label code error classification using CodeT5 and ML-KNN. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 100805–100820. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Chen, B.; Yoo, S.; Lou, J.G. Explainable automated debugging via large language model-driven scientific debugging. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2025, 30, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaedi, S.A.; Noaman, A.Y.; Gad-Elrab, A.A.A.; Eassa, F.E.; Haridi, S. Leveraging Large Language Models for Automated Bug Fixing. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishina, A.; Liventsev, V.; Härmä, A.; Moonen, L. Fully Autonomous Programming Using Iterative Multi-Agent Debugging with Large Language Models. ACM Trans. Evol. Learn. Optim. 2025, 5, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liventsev, V.; Grishina, A.; Härmä, A.; Moonen, L. Fully autonomous programming with large language models. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 15–19 July 2023; pp. 1146–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Vella Zarb, D.; Parks, G.; Kipouros, T. Synergistic Utilization of LLMs for Program Synthesis. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 539–542. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Li, M.; Wen, M.; Cheung, S.C. A study on prompt design, advantages and limitations of ChatGPT for deep learning program repair. Autom. Softw. Eng. 2025, 32, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsofyani, M.; Wang, L. Evaluating ChatGPT’s strengths and limitations for data race detection in parallel programming via prompt engineering. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortin, F.; Rodriguez-Prieto, O.; Garcia, M. Introspector: A general-purpose tool for visualizing and comparing runtime object structures on the Java platform. SoftwareX 2025, 31, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.; Clark, A.T.; Lecomte, N.; Qiao, H.; Ellison, A.M. Harnessing large language models for coding, teaching and inclusion to empower research in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2024, 15, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyasari, R.; Prana, G.A.A.; Haryono, S.A.; Wang, S.; Lo, D. Real world projects, real faults: Evaluating spectrum based fault localization techniques on Python projects. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2022, 27, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, Q.I.; Beszédes, Á. A survey of challenges in spectrum-based software fault localization. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10618–10639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkouche, M. Model checking-enhanced spectrum-based fault localization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing Systems and Applications, Sousse, Tunisia, 22–26 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Widyasari, R.; Prana, G.A.A.; Haryono, S.A.; Tian, Y.; Zachiary, H.N.; Lo, D. XAI4FL: Enhancing spectrum-based fault localization with explainable artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Program Comprehension, Virtual Event, 16–17 May 2022; pp. 499–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Zhang, X.; Hua, Z.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Xiong, Y.; Xie, T. Validity-Preserving Delta Debugging via Generator Trace Reduction. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q. Find bugs in static bug finders. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Program Comprehension, Virtual Event, 16–17 May 2022; pp. 516–527. [Google Scholar]

- Tomassi, D.A.; Rubio-González, C. On the real-world effectiveness of static bug detectors at finding null pointer exceptions. In Proceedings of the 2021 36th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), Melbourne, Australia, 15–19 November 2021; pp. 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Umann, K.; Porkoláb, Z. Towards Better Static Analysis Bug Reports in the Clang Static Analyzer. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/ACM 47th International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice (ICSE-SEIP), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 27 April–3 May 2025; pp. 170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Shahriar, S.; Tufano, M.; Shi, X.; Lu, S.; Sundaresan, N.; Svyatkovskiy, A. Inferfix: End-to-end program repair with llms. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–9 December 2023; pp. 1646–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Serebryany, K.; Kennelly, C.; Phillips, M.; Denton, M.; Elver, M.; Potapenko, A.; Morehouse, M.; Tsyrklevich, V.; Holler, C.; Lettner, J.; et al. Gwp-asan: Sampling-based detection of memory-safety bugs in production. In Proceedings of the 46th International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2024; pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Andrianov, P.; Mutilin, V.; Gerlits, E. Detecting Data Races in Language Virtual Machines with RaceHunter. Lessons Learned. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on the Foundations of Software Engineering, Trondheim, Norway, 23–28 June 2025; pp. 1246–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, P.; Gaddis, N. Leveraging Valgrind to Assess Concurrent, Testing-Unaware C Programs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 31st International Conference on High Performance Computing, Data and Analytics Workshop (HiPCW), Bangalore, India, 18–21 December 2024; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Xiang, C.; Li, H.; He, P. Sbuglocater: Bug localization based on deep matching and information retrieval. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3987981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, C.E.A.; Alimam, M.N.; Kouatly, R. Effectiveness of ChatGPT in coding: A comparative analysis of popular large language models. Digital 2024, 4, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ji, X.; Xu, S.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, S.; Huang, R. An empirical assessment of different word embedding and deep learning models for bug assignment. J. Syst. Softw. 2024, 210, 111961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fang, L.; Lou, J.G. Retro-BLEU: Quantifying chemical plausibility of retrosynthesis routes through reaction template sequence analysis. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citarella, A.A.; Barbella, M.; Ciobanu, M.G.; De Marco, F.; Di Biasi, L.; Tortora, G. Assessing the effectiveness of ROUGE as unbiased metric in Extractive vs. Abstractive summarization techniques. J. Comput. Sci. 2025, 87, 102571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Gupta, K.K. A Detailed Comparative Analysis of Automatic Neural Metrics for Machine Translation: BLEURT & BERTScore. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeijmakers, E.J.; Martens, B.; Hendriks, B.M.; Mihl, C.; Miclea, R.L.; Backes, W.H.; Wildberger, J.E.; Zijta, F.M.; Gietema, H.A.; Nelemans, P.J.; et al. How subjective CT image quality assessment becomes surprisingly reliable: Pairwise comparisons instead of Likert scale. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 4494–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Cui, J.; Xi, R.; Liu, C.; Rashid, P.; Li, R.; Gehringer, E. On assessing the faithfulness of llm-generated feedback on student assignments. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, Atlanta, Georgia, 14–17 July 2024; pp. 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, C.; Tanneru, S.H.; Lakkaraju, H. Faithfulness vs. plausibility: On the (un) reliability of explanations from large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04614. [Google Scholar]

- Camburu, O.M.; Giunchiglia, E.; Foerster, J.; Lukasiewicz, T.; Blunsom, P. Can I trust the explainer? Verifying post-hoc explanatory methods. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.02065. [Google Scholar]

- Russino, J.A.; Wang, D.; Wagner, C.; Rabideau, G.; Mirza, F.; Basich, C.; Mauceri, C.; Twu, P.; Reeves, G.; Tan-Wang, G.; et al. Utility-Driven Approach to Onboard Scheduling and Execution for an Autonomous Europa Lander Mission. J. Aerosp. Inf. Syst. 2025, 22, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Bicong, E.; Huang, X.; Liu, L. Software Defect Prediction Based on Double Traversal AST. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th Asian Conference on Artificial Intelligence Technology (ACAIT), Fuzhou, China, 8–10 November 2024; pp. 1665–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Fang, Y. Augmenting low-resource text classification with graph-grounded pre-training and prompting. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 July 2023; pp. 506–516. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, A. Improving time complexity and accuracy of the machine learning algorithms through selection of highly weighted top k features from complex datasets. Ann. Data Sci. 2019, 6, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wecks, J.O.; Voshaar, J.; Plate, B.J.; Zimmermann, J. Generative AI Usage and Exam Performance. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19699. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, F.; Wang, M.; Li, G.; Peng, B.; Liu, C.; Zheng, M.; Stein, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, E.Z.; Humble, T.; et al. Qasmtrans: A qasm quantum transpiler framework for nisq devices. In Proceedings of the SC’23 Workshops of the International Conference on High Performance Computing, Network, Storage, and Analysis, Denver, CO, USA, 12–17 November 2023; pp. 1468–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, H.; Duan, B.; Yin, J. VCounselor: A psychological intervention chat agent based on a knowledge-enhanced large language model. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Demartini, G.; Gadiraju, U. Plan-then-execute: An empirical study of user trust and team performance when using llm agents as a daily assistant. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama Japan, 26 April–1 May 2025; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, R.; Wang, D.; Zhan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y. Assessing and analyzing the correctness of github copilot’s code suggestions. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Börstler, J.; Bennin, K.E.; Hooshangi, S.; Jeuring, J.; Keuning, H.; Kleiner, C.; MacKellar, B.; Duran, R.; Störrle, H.; Toll, D.; et al. Developers talking about code quality. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2023, 28, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Zhang, H.; Cai, J.; Goyal, N. AI Trust Reshaping Administrative Burdens: Understanding Trust-Burden Dynamics in LLM-Assisted Benefits Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Athens, Greece, 23–26 June 2025; pp. 1172–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Yan, S.; Xie, W.; He, D. When young scholars cooperate with LLMs in academic tasks: The influence of individual differences and task complexities. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 4624–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sharma, P.; Oswal, M.; Xia, H.; Huang, Y. PersonaFlow: Designing LLM-Simulated Expert Perspectives for Enhanced Research Ideation. In Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Madeira, Portugal, 5–9 July 2025; pp. 506–534. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Liu, K.; Kim, D.; Koyuncu, A.; Kim, K.; Tian, H.; Lei, Y.; Mao, X.; Klein, J.; Bissyandé, T.F. Where were the repair ingredients for defects4j bugs? exploring the impact of repair ingredient retrieval on the performance of 24 program repair systems. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2021, 26, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morovati, M.M.; Nikanjam, A.; Khomh, F.; Jiang, Z.M. Bugs in machine learning-based systems: A faultload benchmark. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2023, 28, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuisang, M.C.; Kurniawan, M.; Santosa, K.A.W.; Gunawan, A.A.S.; Saputra, K.E. An evaluation of the effectiveness of openai’s chatGPT for automated python program bug fixing using quixbugs. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication (iSemantic), Semarang, Indonesia, 16–17 September 2023; pp. 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Gyimesi, P.; Vancsics, B.; Stocco, A.; Mazinanian, D.; Beszédes, Á.; Ferenc, R.; Mesbah, A. BUGSJS: A benchmark and taxonomy of JavaScript bugs. Softw. Test. Verif. Reliab. 2021, 31, e1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Ye, C.; Zhou, H. Fine-Tuning Pre-trained Model with Optimizable Prompt Learning for Code Vulnerability Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 35th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE), Tsukuba, Japan, 28–31 October 2024; pp. 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Si, Q.; Lin, Z. Breaking the Trade-Off Between Faithfulness and Expressiveness for Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.18651. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Deng, M.; Chen, M.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.M. Assessing the effectiveness of recent closed-source large language models in fault localization and automated program repair. Autom. Softw. Eng. 2026, 33, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, H.; Zuo, J.; Liu, J.; Niu, W. Investigating the bugs in reinforcement learning programs: Insights from Stack Overflow and GitHub. Autom. Softw. Eng. 2026, 33, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, M.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, J. Context-aware prompting for LLM-based program repair. Autom. Softw. Eng. 2025, 32, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocklove, J.; Thakur, S.; Tan, B.; Pearce, H.A.; Garg, S.J.; Karri, R. Automatically Improving LLM-based Verilog Generation using EDA Tool Feedback. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 2025, 30, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Li, Z.; Pei, Y.; Wen, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhang, T.; Li, X. PReMM: LLM-Based Program Repair for Multi-method Bugs via Divide and Conquer. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2025, 9, 1316–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Du, X.; Liu, H. ReAPR: Automatic program repair via retrieval-augmented large language models. Softw. Qual. J. 2025, 33, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhanahnah, M.J.; Hasan, M.R.; Xu, L.; Bagheri, H. An empirical evaluation of pre-trained large language models for repairing declarative formal specifications. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2025, 30, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Kuang, B.; Su, M.; Fu, A. Survey of Large-Language-Model-Based Automated Program Repair. Jisuanji Yanjiu Yu Fazhan/Comput. Res. Dev. 2025, 62, 2040–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, X.; Wang, R. TestLoter: A logic-driven framework for automated unit test generation and error repair using large language models. J. Comput. Lang. 2025, 84, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; David, C.; Wang, M.; Paulsen, B.; Kroening, D. Scalable, Validated Code Translation of Entire Projects using Large Language Models. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2025, 9, 1616–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Kuhar, S.; Çirisci, B.; Garg, P.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Deoras, A.; Ray, B. UTFix: Change Aware Unit Test Repairing using LLM. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2025, 9, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lu, L.; Qiu, S.; Tian, Q.; Lin, H. DALO-APR: LLM-based automatic program repair with data augmentation and loss function optimization. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.F.; Ferreira Mello, R. A Systematic Literature Review on Large Language Models Applications in Computer Programming Teaching Evaluation Process. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 113449–113460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinn, A.J.; Li, X.; Kim, J.h.; Omar, C. Statically Contextualizing Large Language Models with Typed Holes. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2024, 8, 468–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Martinez, M.; Demarco, F.; Clement, M.; Marcote, S.L.; Durieux, T.; Le Berre, D.; Monperrus, M. Nopol: Automatic repair of conditional statement bugs in java programs. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2016, 43, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosà, A.; Basso, M.; Bohnhoff, L.; Binder, W. Automated Runtime Transition between Virtual and Platform Threads in the Java Virtual Machine. In Proceedings of the 2023 30th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 4–7 December 2023; pp. 607–611. [Google Scholar]

- Guizzo, G.; Bazargani, M.; Paixao, M.; Drake, J.H. A hyper-heuristic for multi-objective integration and test ordering in google guava. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Search Based Software Engineering, Paderborn, Germany, 9–11 September 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski, M.; Zabierowski, W. Analysis and comparison of the Spring framework and play framework performance, used to create web applications in Java. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE XVth International Conference on the Perspective Technologies and Methods in MEMS Design (MEMSTECH), Polyana, Ukraine, 22–26 May 2019; pp. 170–173. [Google Scholar]

- Walter-Tscharf, F.F.W.V. Indexing, clustering, and search engine for documents utilizing Elasticsearch and Kibana. In Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics: Proceedings of ICMCSI 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 897–910. [Google Scholar]

- Alqaradaghi, M.; Nazir, M.Z.I.; Kozsik, T. Design and Implement an Accurate Automated Static Analysis Checker to Detect Insecure Use of SecurityManager. Computers 2023, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.h.; Nam, J. WINE: Warning miner for improving bug finders. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2023, 155, 107109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vach, W.; Gerke, O. Gwet’s AC1 is not a substitute for Cohen’s kappa–A comparison of basic properties. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.; Lee, H.; Kang, S. An empirical study of Korean sentence representation with various tokenizations. Electronics 2021, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, A.; Luburić, N.; Slivka, J.; Prokić, S.; Grujić, K.G.; Vidaković, D.; Sladić, G. Automatic detection of code smells using metrics and CodeT5 embeddings: A case study in C#. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 9203–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms. In Springer Handbook of Computational Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 995–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Xu, W.; Li, L.; He, C.; Cheng, R. Adaptive simulated binary crossover for rotated multi-objective optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 60, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahedi, K.; Gyambrah, N.; Li, H.; Lamothe, M.; Khomh, F. An Empirical Study on Method-Level Performance Evolution in Open-Source Java Projects. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.07084. [Google Scholar]

- Dehdarirad, T. Evaluating explainability in language classification models: A unified framework incorporating feature attribution methods and key factors affecting faithfulness. Data Inf. Manag. 2025, 9, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Liu, N.; Deng, H.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Yin, D.; Du, M. Explainability for large language models: A survey. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.; Erata, F.; Iser, M.; Sinz, C.; Loiret, F.; Otten, S.; Sax, E. Integrating static code analysis toolchains. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 43rd Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 15–19 July 2019; Volume 1, pp. 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Gbenle, P.; Abieba, O.A.; Owobu, W.O.; Onoja, J.P.; Daraojimba, A.I.; Adepoju, A.H.; Chibunna, U.B. A privacy-preserving AI model for autonomous detection and masking of sensitive user data in contact center analytics. World Sci. News 2025, 203, 154–193. [Google Scholar]

- Eghbali, A.; Burk, F.; Pradel, M. DyLin: A Dynamic Linter for Python. Proc. ACM Softw. Eng. 2025, 2, 2828–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, N.J.; Majeed, B.K. Evaluating Large Language Models using Arabic Prompts to Generate Python Codes. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA), Sana’a, Yemen, 6–7 August 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rak-Amnouykit, I.; McCrevan, D.; Milanova, A.; Hirzel, M.; Dolby, J. Python 3 types in the wild: A tale of two type systems. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM SIGPLAN International Symposium on Dynamic Languages, Virtual, 17 November 2020; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, E.; Kleynhans, B.; Kadioğlu, S. Mabwiser: A parallelizable contextual multi-armed bandit library for python. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 31st International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Portland, OR, USA, 4–6 November 2019; pp. 909–914. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, A.; Saha, R.; Kumar, G.; Brighente, A.; Conti, M.; Kim, T.H. Exploring the Landscape of Programming Language Identification with Machine Learning Approaches. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 23556–23579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Tan, T.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Lai, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Dong, W.; Zhou, Y. Mitigating false positive static analysis warnings: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2023, 49, 5154–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, Z.; You, Y. To repeat or not to repeat: Insights from scaling llm under token-crisis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 59304–59322. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, S.; Karthika Renuka, D.; Ashok Kumar, L. Robust Multi-Dialect End-to-End ASR Model Jointly with Beam Search Threshold Pruning and LLM. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, E.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Z. When to stop? towards efficient code generation in llms with excess token prevention. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Vienna, Austria, 16–20 September 2024; pp. 1073–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, Y.A. Hallucinations in large language models and their influence on legal reasoning: Examining the risks of ai-generated factual inaccuracies in judicial processes. J. Comput. Intell. Mach. Reason. Decis.-Mak. 2025, 10, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Naiseh, M.; Simkute, A.; Zieni, B.; Jiang, N.; Ali, R. C-XAI: A conceptual framework for designing XAI tools that support trust calibration. J. Responsible Technol. 2024, 17, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y. Automatic Inspection of Static Application Security Testing (SAST) Reports via Large Language Model Reasoning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on AI Logic and Applications, Lanzhou, China, 10–11 August 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, H.; Fan, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Q. TokenRec: Learning to Tokenize ID for LLM-Based Generative Recommendations. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 6216–6231. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).