Why Cemiplimab? Defining a Unique Therapeutic Niche in First-Line Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Ultra-High PD-L1 Expression and Squamous Histology

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Characteristics

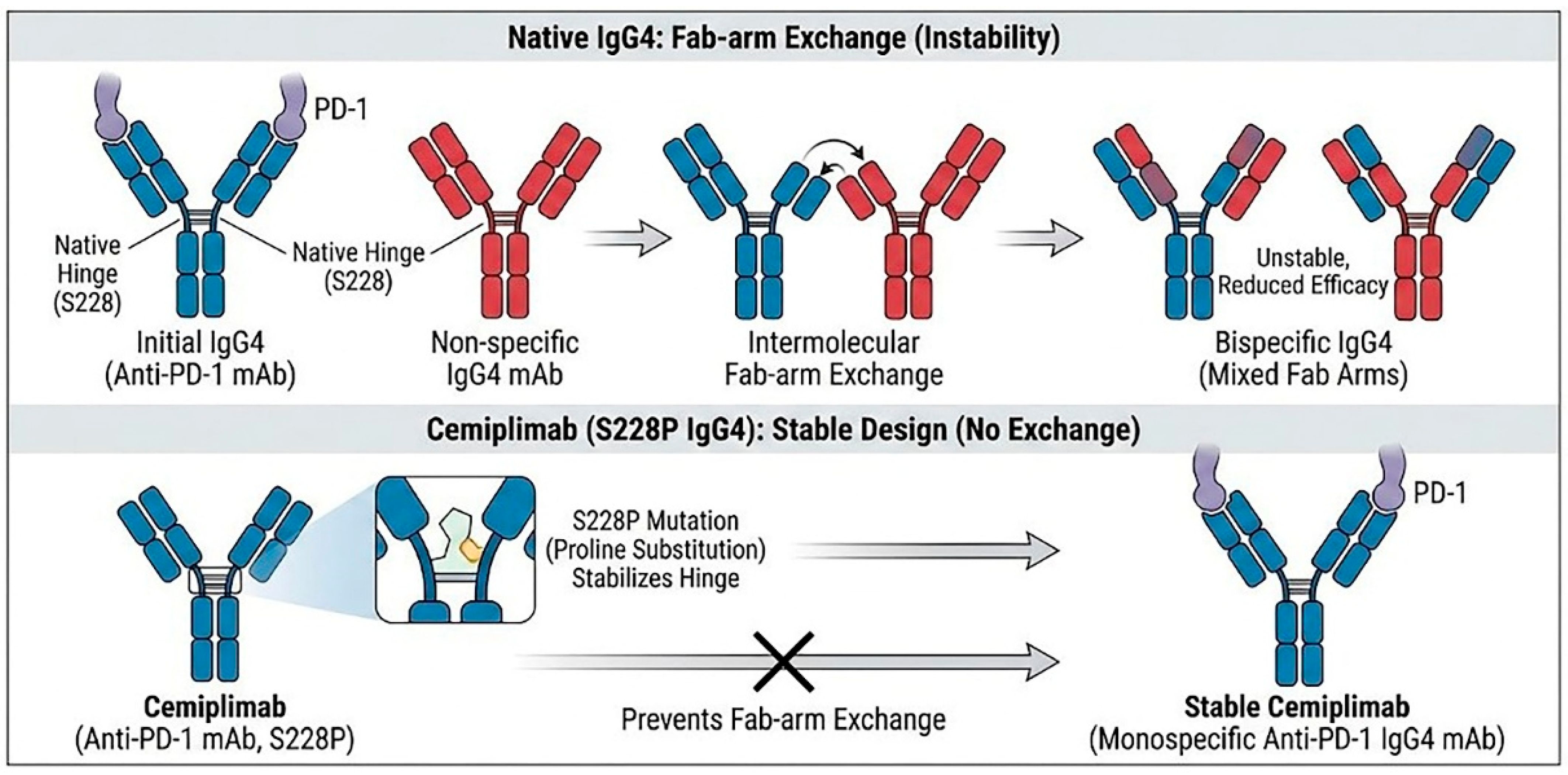

2.1. The IgG4 Backbone and the S228P Mutation: Ensuring Stability and Low Immunogenicity

2.2. Anti-Drug Antibodies (ADAs) and Immunogenicity

2.3. Critical Role of PD-1 Glycosylation (N58-Glycan)

3. Evidence from Pivotal Trials

3.1. EMPOWER-Lung 1

3.2. EMPOWER-Lung 3

3.3. Japanese Phase I, Dose-Expansion Study

4. Strategic Positioning in Clinical Practice

4.1. Cemiplimab Monotherapy: Advantages in Squamous Histology and Ultra-High PD-L1 Subgroups

4.2. Cemiplimab Plus Chemotherapy: Clinical Value in Squamous Histology

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, E.J.; Kim, H.R.; Arcila, M.E.; Barron, D.; Chakravarty, D.; Gao, J.; Chang, M.T.; Ni, A.; Kundra, R.; Jonsson, P.; et al. Prospective Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Lung Adenocarcinomas for Efficient Patient Matching to Approved and Emerging Therapies. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.H.; Harrington, D.; Belani, C.P.; Langer, C.; Sandler, A.; Krook, J.; Zhu, J.; Johnson, D.H. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagliotti, G.V.; Parikh, P.; von Pawel, J.; Biesma, B.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Manegold, C.; Serwatowski, P.; Gatzemeier, U.; Digumarti, R.; Zukin, M.; et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Agata, Y.; Shibahara, K.; Honjo, T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3887–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Gettinger, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Chow, L.Q.M.; Burgio, M.A.; de Castro Carpeno, J.; Pluzanski, A.; Arrieta, O.; Frontera, O.A.; Chiari, R.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes from the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Steins, M.; Ready, N.E.; Chow, L.Q.; Vokes, E.E.; Felip, E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fessas, P.; Lee, H.; Ikemizu, S.; Janowitz, T. A molecular and preclinical comparison of the PD-1-targeted T-cell checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Semin. Oncol. 2017, 44, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Sofiya, L.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Lamine, F.; Maillard, M.; Fraga, M.; Shabafrouz, K.; Ribi, C.; Cairoli, A.; Guex-Crosier, Y.; et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burova, E.; Hermann, A.; Waite, J.; Potocky, T.; Lai, V.; Hong, S.; Liu, M.; Allbritton, O.; Woodruff, A.; Wu, Q.; et al. Characterization of the Anti-PD-1 Antibody REGN2810 and Its Antitumor Activity in Human PD-1 Knock-In Mice. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migden, M.R.; Rischin, D.; Schmults, C.D.; Guminski, A.; Hauschild, A.; Lewis, K.D.; Chung, C.H.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Lim, A.M.; Chang, A.L.S.; et al. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratigos, A.J.; Sekulic, A.; Peris, K.; Bechter, O.; Prey, S.; Kaatz, M.; Lewis, K.D.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Chang, A.L.S.; Dalle, S.; et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced basal cell carcinoma after hedgehog inhibitor therapy: An open-label, multi-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, K.S.; Monk, B.J.; Vergote, I.; Miller, A.; de Melo, A.C.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Samouëlian, V.; Lorusso, D.; et al. Investigators for GOG Protocol 3016 and ENGOT Protocol En-Cx9. Survival with Cemiplimab in Recurrent Cervical Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispens, T.; Huijbers, M.G. The unique properties of IgG4 and its roles in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, X.; Li, K.; Zhang, T. FcγR-Binding Is an Important Functional Attribute for Immune Checkpoint Antibodies in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Antonenko, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.W.; Tabrizifard, M.; Ermakov, G.; Wiswell, D.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of the Therapeutic IgG4 Antibody Pembrolizumab: Hinge Modification Blocks Half Molecule Exchange In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 4002–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico, D.; Paci, A.; Chaput, N.; Karamouza, E.; Besse, B. Antidrug Antibodies Against Immune Checkpoint Blockers: Impairment of Drug Efficacy or Indication of Immune Activation? Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usdin, M.; Quarmby, V.; Zanghi, J.; Bernaards, C.; Liao, L.; Laxamana, J.; Wu, B.; Swanson, S.; Song, Y.; Siguenza, P. Immunogenicity of Atezolizumab: Influence of Testing Method and Sampling Frequency on Reported Anti-drug Antibody Incidence Rates. AAPS J. 2024, 26, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Galle, P.R.; Bernaards, C.A.; Ballinger, M.; Bruno, R.; Quarmby, V.; Ruppel, J.; Vilimovskij, A.; Wu, B.; Sternheim, N.; et al. Evaluation of atezolizumab immunogenicity: Efficacy and safety (Part 2). Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 15, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucali, P.A.; Lin, C.C.; Carthon, B.C.; Bauer, T.M.; Tucci, M.; Italiano, A.; Iacovelli, R.; Su, W.C.; Massard, C.; Saleh, M.; et al. Targeting CD38 and PD-1 with isatuximab plus cemiplimab in patients with advanced solid malignancies: Results from a phase I/II open-label, multicenter study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Tani, Y.; Ishii, H.; Katakura, S.; Oki, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Yokoyama, T.; Naoki, K.; Pouliot, J.F.; Kaul, M.; et al. Cemiplimab in Japanese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 56, hyaf160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, P.; Finn, R.S.; Mitchell, C.R.; Ndirangu, K.; Ramji, Z.; Redhead, G.S.; Pinato, D.J. Treatment-emergent antidrug antibodies related to PD-1, PD-L1, or CTLA-4 inhibitors across tumor types: A systematic review. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Sternheim, N.; Agarwal, P.; Suchomel, J.; Vadhavkar, S.; Bruno, R.; Ballinger, M.; Bernaards, C.A.; Chan, P.; Ruppel, J.; et al. Evaluation of atezolizumab immunogenicity: Clinical pharmacology (part 1). Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 15, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Statkevich, P.; Bajaj, G.; Feng, Y.; Saeger, S.; Desai, D.D.; Park, J.S.; Waxman, I.M.; Roy, A.; Gupta, M. Evaluation of Immunogenicity of Nivolumab Monotherapy and Its Clinical Relevance in Patients with Metastatic Solid Tumors. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 57, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, D.; Jin, Z.; Budczies, J.; Kluck, K.; Stenzinger, A.; Sinicrope, F.A. Tumor Mutational Burden as a Predictive Biomarker in Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1808–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, T.A.; Yarchoan, M.; Jaffee, E.; Swanton, C.; Quezada, S.A.; Stenzinger, A.; Peters, S. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: Utility for the oncology clinic. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, C.W.; Chung, E.M.; Yang, R.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, A.H.; Lai, Y.J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, J.; et al. Targeting Glycosylated PD-1 Induces Potent Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 2298–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, M.; Liu, K.; He, J.; Ma, D.; Ma, X.; Tan, S.; Gao, G.F.; et al. PD-1 N58-Glycosylation-Dependent Binding of Monoclonal Antibody Cemiplimab for Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 826045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, J.; Kirchgatterer, P.C.; Singh, A.; Cho, J.H.; Nety, S.P.; Larson, R.C.; Macrae, R.K.; Deasy, R.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Maus, M.V.; et al. CRISPR activation screen identifies BCL-2 proteins and B3GNT2 as drivers of cancer resistance to T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rischin, D.; Porceddu, S.; Day, F.; Brungs, D.P.; Christie, H.; Jackson, J.E.; Stein, B.N.; Su, Y.B.; Ladwa, R.; Adams, G.; et al. C-POST Trial Investigators. Adjuvant Cemiplimab or Placebo in High-Risk Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, A.; Kilickap, S.; Gümüş, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Gogishvili, M.; Turk, H.M.; Cicin, I.; Bentsion, D.; Gladkov, O.; et al. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: A multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilickap, S.; Baramidze, A.; Sezer, A.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Gumus, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Gogishvili, M.; Nechaeva, M.; Schenker, M.; Cicin, I.; et al. Cemiplimab Monotherapy for First-Line Treatment of Patients with Advanced NSCLC With PD-L1 Expression of 50% or Higher: Five-Year Outcomes of EMPOWER-Lung 1. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025, 20, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilickap, S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Sezer, A.; Gümüş, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Gogishvili, M.; Turk, H.M.; Cicin, I.; Bentsion, D.; Gladkov, O.; et al. Cemiplimab monotherapy as first-line treatment of patients with brain metastases from advanced non-small cell lung cancer with programmed cell death-ligand 1 ≥ 50. Cancer 2025, 131, e35864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogishvili, M.; Melkadze, T.; Makharadze, T.; Giorgadze, D.; Dvorkin, M.; Penkov, K.; Laktionov, K.; Nemsadze, G.; Nechaeva, M.; Rozhkova, I.; et al. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer: A randomized, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makharadze, T.; Gogishvili, M.; Melkadze, T.; Baramidze, A.; Giorgadze, D.; Penkov, K.; Laktionov, K.; Nemsadze, G.; Nechaeva, M.; Rozhkova, I.; et al. Cemiplimab Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone in Advanced NSCLC: 2-Year Follow-Up from the Phase 3 EMPOWER-Lung 3 Part 2 Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baramidze, A.; Makharadze, T.; Gogishvili, M.; Melkadze1, T.; Giorgadze, D.; Penkov, K.; Laktionov, K.; Nemsadze, G.; Nechaeva, M.; Rozhkova, I.; et al. MA10.09 Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC: 5-year results from phase 3 EMPOWER-Lung 3 Part 2 trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025, 20, s99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes with Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciuti, B.; Elkrief, A.; Lin, J.; Zhang, J.; Alessi, J.V.; Lamberti, G.; Gandhi, M.; Di Federico, A.; Pecci, F.; Wang, X.; et al. Three-Year Overall Survival Outcomes and Correlative Analyses in Patients with NSCLC and High (50–89%) Versus Very High (≥90%) Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Expression Treated with First-Line Pembrolizumab or Cemiplimab. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2024, 5, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garassino, M.C.; Gadgeel, S.; Speranza, G.; Felip, E.; Esteban, E.; Dómine, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; Bischoff, H.G.; Peled, N.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes from the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novello, S.; Kowalski, D.M.; Luft, A.; Gümüş, M.; Vicente, D.; Mazières, J.; Rodríguez-Cid, J.; Tafreshi, A.; Cheng, Y.; Lee, K.H.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, N.D.; Miller, D.M.; Khushalani, N.I.; Divi, V.; Ruiz, E.S.; Lipson, E.J.; Meier, F.; Su, Y.B.; Swiecicki, P.L.; Atlas, J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Cemiplimab for Stage II to IV Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | EMPOWER-Lung 1 | EMPOWER-Lung 3 | KEYNOTE-024 | KEYNOTE-189 | KEYNOTE-407 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | |||||

| Regimen | Cemiplimab | Cemiplimab + Chemotherapy | Pembrolizumab | Pembrolizumab + Chemotherapy | Pembrolizumab + Chemotherapy |

| Target Population | PD-L1 ≥ 50% | All Comers | PD-L1 ≥ 50% | Non-Squamous | Squamous |

| Demographics | |||||

| Median Age | 63 years | 64 years | 64.5 years | 65 years | 65 years |

| Gender (Male) | 87.7% | 70.0% | 59.7% | 65.8% | 80.5% |

| ECOG PS 1 | 72.9% | 63.8% | 64.3% | 60.2% | 70.3% |

| Histology | |||||

| Squamous | 43.3% | 42.4% | 18.8% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Non-Squamous | 56.7% | 57.6% | 81.2% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| PD-L1 Status | |||||

| <1% | - | 32.0% | - | 32.9% | 35.1% |

| 1–49% | - | 36.0% | - | 36.0% | 38.8% |

| ≥50% | 100.0% | 32.0% | 100.0% | 31.2% | 26.1% |

| ≥90% (Ultra-high) | 35.0% | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| Trial Name | Agent | Target Population | Histology | Median OS (95% CI) | OS HR (95% CI) | Median PFS (95% CI) | PFS HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMPOWER-Lung 1 | Cemiplimab | Overall (PD-L1 ≥ 50%) | All | 26.1 months (22.1–31.9) | 0.59 (0.48–0.72) | 8.1 months (6.2–8.8) | 0.50 (0.41–0.61) |

| PD-L1 ≥ 90% (Ultra-high) | All | 38.8 months (22.9–NE) | 0.44 (0.30–0.65) | 14.7 months (10.2–21.1) | 0.32 (0.22–0.46) | ||

| PD-L1 ≥ 50% | Squamous | 22.7 months (17.3–31.5) | 0.51 (0.38–0.69) | 8.3 months (5.6–9.4) | 0.44 (0.32–0.60) | ||

| PD-L1 ≥ 50% | Non-Sq | 28.7 months (22.9–44.3) | 0.66 (0.50–0.88) | 6.5 months (4.4–12.4) | 0.55 (0.42–0.72) | ||

| Japanese Phase 1 | Cemiplimab | Cohort A (PD-L1 ≥ 50%) | All | 44.5 months (27.0–54.4) | - | NR (12.5–NE) | - |

| KEYNOTE-024 | Pembrolizumab | Overall (PD-L1 ≥ 50%) | All | 26.3 months (18.3–40.4) | 0.62 (0.48–0.81) | 7.7 months (6.1–10.2) | 0.50 (0.39–0.65) |

| PD-L1 ≥ 50% | Squamous | - | 0.61 (0.30–1.24) | - | 0.37 (0.19–0.73) | ||

| PD-L1 ≥ 50% | Non-Sq | - | 0.63 (0.47–0.84) | - | 0.54 (0.41–0.71) |

| Trial Name/ Agent | Target Population (Subgroup) | Histology | Median OS (95% CI) | OS HR (95% CI) | Median PFS (95% CI) | PFS HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMPOWER-Lung 3/ Cemiplimab + Chemo | Overall | All | 21.1 months (15.9–23.9) | 0.66 (0.53–0.83) | 8.2 months (6.4–9.3) | 0.58 (0.47–0.72) |

| Squamous (PD-L1 any) | Squamous | 22.3 months (15.7–27.2) | 0.61 (0.42–0.87) | 8.2 months (6.3–10.7) | 0.56 (0.41–0.78) | |

| Non-Squamous (PD-L1 any) | Non-Squamous | 19.4 months (14.0–23.5) | 0.64 (0.47–0.88) | - | 0.61 (0.45–0.81) | |

| PD-L1 1–49% | All | - | 0.50 (0.34–0.74) | - | 0.48 (0.34–0.68) | |

| Japanese Phase 1/ Cemiplimab + Chemo | Cohort C (Overall) | All | NR (13.4–NE) | - | 8.1 months (6.0–NE) | - |

| PD-L1 1–49% | All | - | - | - | - | |

| KEYNOTE-189/ Pembrolizumab + Chemo | Overall | Non-Squamous | 22.0 months (19.5–24.5) | 0.60 (0.50–0.72) | 9.0 months (8.1–10.4) | 0.50 (0.42–0.60) |

| PD-L1 1–49% | Non-Squamous | 21.8 months (17.7–25.6) | 0.65 (0.46–0.90) | 9.4 months (6.1–12.8) | 0.57 (0.41–0.80) | |

| KEYNOTE-407/ Pembrolizumab + Chemo | Overall | Squamous | 17.2 months (14.4–19.7) | 0.71 (0.59–0.85) | 6.4 months (6.2–8.3) | 0.62 (0.52–0.74) |

| PD-L1 1–49% | Squamous | 19.3 months (12.2–25.2) | 0.61 (0.45–0.83) | 6.5 months (4.4–12.4) | 0.57 (0.42–0.78) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ikeda, S.; Araki, K.; Kitagawa, M.; Makihara, N.; Nagata, Y.; Fujii, K.; Yoshida, K.; Ikoma, T.; Nakahama, K.; Takeyasu, Y.; et al. Why Cemiplimab? Defining a Unique Therapeutic Niche in First-Line Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Ultra-High PD-L1 Expression and Squamous Histology. Cancers 2026, 18, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020272

Ikeda S, Araki K, Kitagawa M, Makihara N, Nagata Y, Fujii K, Yoshida K, Ikoma T, Nakahama K, Takeyasu Y, et al. Why Cemiplimab? Defining a Unique Therapeutic Niche in First-Line Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Ultra-High PD-L1 Expression and Squamous Histology. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020272

Chicago/Turabian StyleIkeda, Satoshi, Keigo Araki, Mai Kitagawa, Natsuno Makihara, Yutaro Nagata, Kazuki Fujii, Kiyori Yoshida, Tatsuki Ikoma, Kahori Nakahama, Yuki Takeyasu, and et al. 2026. "Why Cemiplimab? Defining a Unique Therapeutic Niche in First-Line Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Ultra-High PD-L1 Expression and Squamous Histology" Cancers 18, no. 2: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020272

APA StyleIkeda, S., Araki, K., Kitagawa, M., Makihara, N., Nagata, Y., Fujii, K., Yoshida, K., Ikoma, T., Nakahama, K., Takeyasu, Y., Katsushima, U., Yamanaka, Y., & Kurata, T. (2026). Why Cemiplimab? Defining a Unique Therapeutic Niche in First-Line Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Ultra-High PD-L1 Expression and Squamous Histology. Cancers, 18(2), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020272