Tumor Microenvironment: Insights from Multiparametric MRI in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preclinical Study with Animals and Tumor Models

2.2. Preclinical MRI Data Acquisition

2.3. Irradiation

2.4. Histology

2.5. DeepLIIF

2.6. Clinical Study with Patients with PDAC

2.7. Clinical MRI Data Acquisition

2.8. DW- and DCE-MRI Data Modeling and Analysis

2.9. Image Processing and Data Analysis

2.9.1. Image Processing and Data Analysis for the Preclinical PDAC Model

2.9.2. Image Processing and Data Analysis for Patients with PDAC

3. Results

3.1. Insights into the Architecture of the TME in PDAC

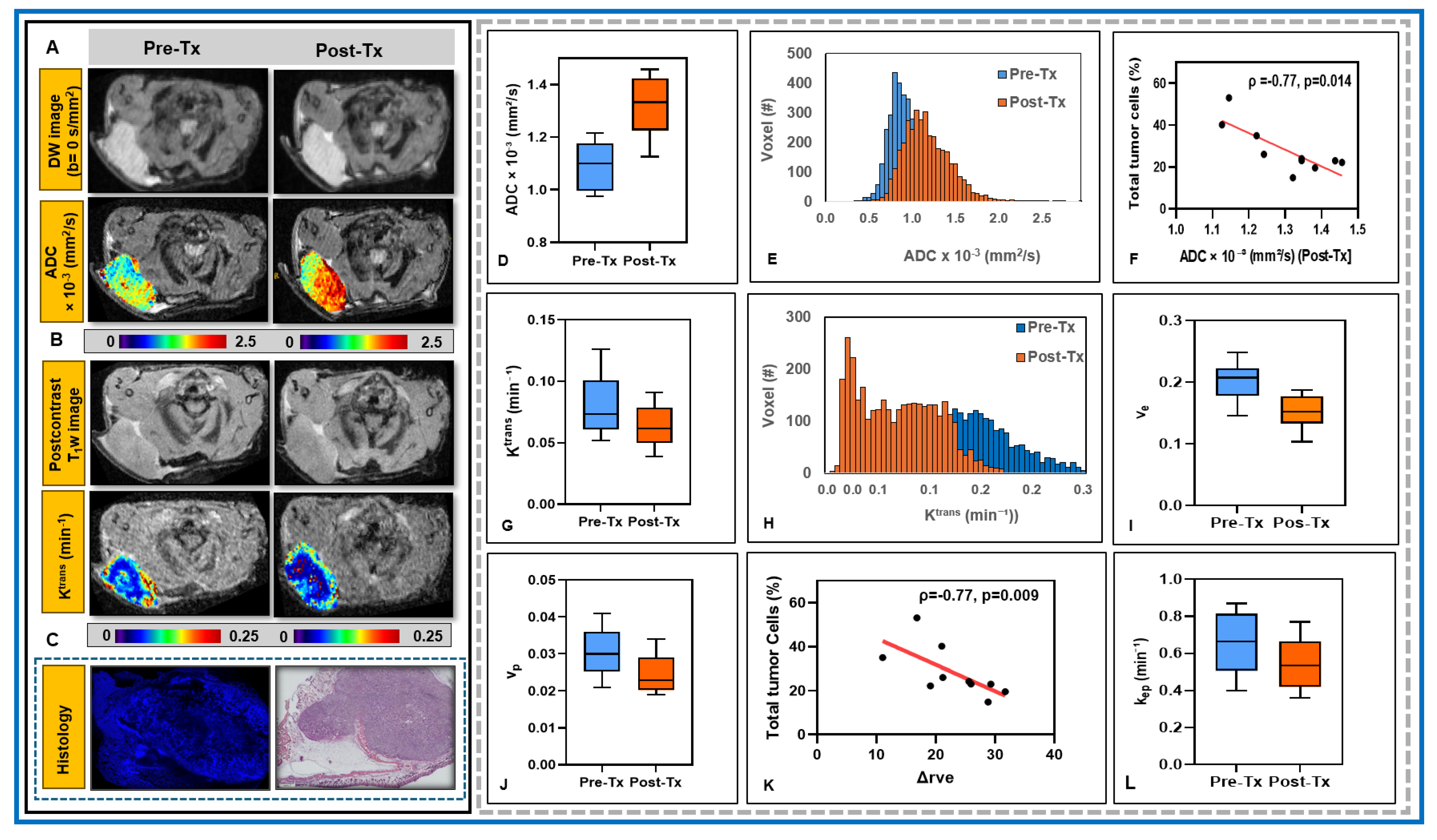

3.2. Potential of mpMRI-Derived QIBs to Determine Early Treatment Response

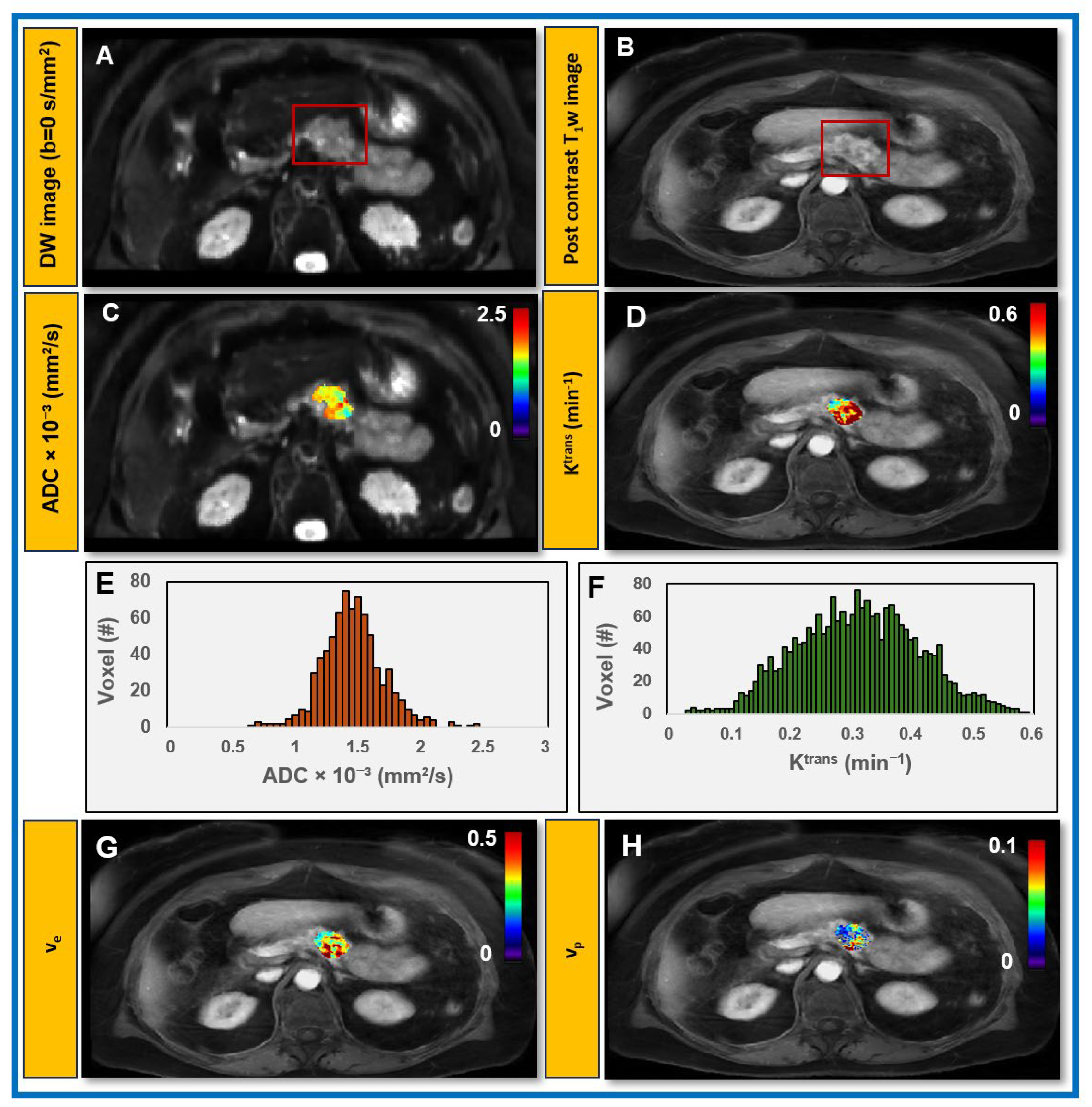

3.3. Feasibility of Obtaining QIBs from Patients with PDAC at Pre-Treatment mpMRI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Apparent diffusion coefficient |

| AIF | Arterial input function |

| CA | Contrast agent |

| DISCO | Differential Subsampling with Cartesian ordering |

| DKI | Diffusion kurtosis imaging |

| DW | Diffusion-weighted |

| DCE | Dynamic contrast-enhanced |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EES | Extravascular extracellular space |

| FA | Flip angle |

| FLASH | Fast Low Angle Shot |

| FOV | Field of view |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| LAVA | Liver Acquisition with Volume Acceleration |

| mpMRI | Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging |

| MS | Matrix size |

| NA | Number of averages |

| NS | Number of slices |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PERT | Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| RARE | Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement |

| rFOV | Reduced field of view |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| STAR | Stack-of-stars |

| TE | Echo time |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TR | Repetition time |

| QIB | Quantitative imaging biomarker |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michetti, F.; Cirone, M.; Strippoli, R.; D’Orazi, G.; Cordani, M. Mechanistic insights and therapeutic strategies for targeting autophagy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghy, K.; Ladányi, A.; Reszegi, A.; Kovalszky, I. Insights into the Tumor Microenvironment-Components, Functions and Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangnia, P.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Nickho, H.; Delbandi, A.-A. Current and future immunotherapeutic approaches in pancreatic cancer treatment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitter, K.L.; Grbovic-Huezo, O.; Joost, S.; Singhal, A.; Blum, M.; Wu, K.; Holm, M.; Ferrena, A.; Bhutkar, A.; Hudson, A.; et al. Systematic Comparison of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Models Identifies a Conserved Highly Plastic Basal Cell State. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3549–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartupee, C.; Nagalo, B.M.; Chabu, C.Y.; Tesfay, M.Z.; Coleman-Barnett, J.; West, J.T.; Moaven, O. Pancreatic cancer tumor microenvironment is a major therapeutic barrier and target. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1287459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhani, A.R.; Khan, A.A. Diffusion-weighted (DW) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for monitoring anticancer therapy. Target. Oncol. 2010, 5, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, M.; Metzger, P.; Gerum, S.; Mayerle, J.; Schneider, G.; Belka, C.; Schnurr, M.; Lauber, K. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Biological hallmarks, current status, and future perspectives of combined modality treatment approaches. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Lv, P.; Zhang, H.; Fu, C.; Yao, X.; Wang, C.; Zeng, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI assessment of microvascular characteristics in the murine orthotopic pancreatic cancer model. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 33, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, C.S.; Gaustad, J.V.; Andersen, L.M.; Simonsen, T.G.; Rofstad, E.K. Diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of pancreatic adenocarcinoma xenografts: Associations with tumor differentiation and collagen content. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, R.; Park, J.; Wang, Y.N.; Gravelle, K.; Whang, S.; Hwang, J.H.; Lee, D. Evaluation of pancreatic tumor development in KPC mice using multi-parametric MRI. Cancer Imaging 2018, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wojtkowiak, J.W.; Martinez, G.V.; Cornnell, H.H.; Hart, C.P.; Baker, A.F.; Gillies, R. MR Imaging Biomarkers to Monitor Early Response to Hypoxia-Activated Prodrug TH-302 in Pancreatic Cancer Xenografts. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Pickup, S.; Clendenin, C.; Blouw, B.; Choi, H.; Kang, D.; Rosen, M.; O’Dwyer, P.J.; Zhou, R. Dynamic Contrast-enhanced MRI Detects Responses to Stroma-directed Therapy in Mouse Models of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2314–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akisik, M.F.; Sandrasegaran, K.; Bu, G.; Lin, C.; Hutchins, G.D.; Chiorean, E.G. Pancreatic cancer: Utility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging in assessment of antiangiogenic therapy. Radiology 2010, 256, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heid, I.; Steiger, K.; Trajkovic-Arsic, M.; Settles, M.; Eßwein, M.R.; Erkan, M.; Kleeff, J.; Jäger, C.; Friess, H.; Haller, B.; et al. Co-clinical Assessment of Tumor Cellularity in Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinh Do, R.; Reyngold, M.; Paudyal, R.; Oh, J.H.; Konar, A.S.; LoCastro, E.; Goodman, K.A.; Shukla-Dave, A. Diffusion-Weighted and Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI Derived Imaging Metrics for Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Preliminary Findings. Tomography 2020, 6, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, F.; Xie, T.; Liu, W.; Xiang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Z. Value of diffusion kurtosis MR imaging and conventional diffusion weighed imaging for evaluating response to first-line chemotherapy in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Imaging 2024, 24, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofts, P.S.; Brix, G.; Buckley, D.L.; Evelhoch, J.L.; Henderson, E.; Knopp, M.V.; Larsson, H.B.; Lee, T.Y.; Mayr, N.A.; Parker, G.J.; et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: Standardized quantities and symbols. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1999, 10, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Liu, W.; Li, H.-M.; Wang, Q.-F.; Fu, C.-X.; Wang, X.-H.; Zhou, L.-P.; Peng, W.J. Quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging for the preliminary prediction of the response to gemcitabine-based chemotherapy in advanced pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Eur. J. Radiol. 2019, 121, 108734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukukura, Y.; Kumagae, Y.; Fujisaki, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Dominik Nickel, M.; Imai, H.; Yoshiura, T. Extracellular volume fraction with MRI: As an alternative predictive biomarker to dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for chemotherapy response of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 145, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, K.C.; de Groot, A.E.; Pienta, K.J. Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic-Arsic, M.; Heid, I.; Steiger, K.; Gupta, A.; Fingerle, A.; Worner, C.; Teichmann, N.; Sengkwawoh-Lueong, S.; Wenzel, P.; Beer, A.J.; et al. Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) predicts therapy response in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorza, A.M.A.; Ravi, H.; Philip, R.C.; Galons, J.-P.; Trouard, T.P.; Parra, N.A.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Read, W.L.; Tibes, R.; Korn, R.L.; et al. Dose–response assessment by quantitative MRI in a phase 1 clinical study of the anti-cancer vascular disrupting agent crolibulin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Lorza, A.M.; Costello, J.R.; Hingorani, S.R.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Korn, R.L.; Raghunand, N. Tumor Response to Stroma-Modifying Therapy: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in Early-Phase Clinical Trials of Pegvorhyaluronidase alpha (PEGPH20). Res. Sq. 2023, 3, 3314770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, P.P.; Hingorani, S.R. Hyaluronan, fluid pressure, and stromal resistance in pancreas cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalah, E.; Erickson, B.; Oshima, K.; Schott, D.; Hall, W.A.; Paulson, E.; Tai, A.; Knechtges, P.; Li, X.A. Correlation of ADC with Pathological Treatment Response for Radiation Therapy of Pancreatic Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.E.; Paget, J.T.; Khan, A.A.; Harrington, K.J. The tumour microenvironment after radiotherapy: Mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, E.A.; Alsaleem, M.; ElSharawy, K.A.; Toss, M.S.; Raafat, S.; Mihai, R.; Minhas, F.A.; Green, A.R.; Rajpoot, N.M.; Dalton, L.W.; et al. Visual histological assessment of morphological features reflects the underlying molecular profile in invasive breast cancer: A morphomolecular study. Histopathology 2020, 77, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalber, T.L.; Waterton, J.C.; Griffiths, J.R.; Ryan, A.J.; Robinson, S.P. Longitudinal in vivo susceptibility contrast MRI measurements of LS174T colorectal liver metastasis in nude mice. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2008, 28, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.L.; Sorace, A.G.; Loveless, M.E.; Whisenant, J.G.; Yankeelov, T.E. Correlation of tumor characteristics derived from DCE-MRI and DW-MRI with histology in murine models of breast cancer. NMR Biomed. 2015, 28, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, R.; Steins, A.; Gurney-Champion, O.J.; Bijlsma, M.F.; van Tienhoven, G.; Engelbrecht, M.R.W.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; Suker, M.; Wilmink, J.W.; Besselink, M.G.; et al. Pathological validation and prognostic potential of quantitative MRI in the characterization of pancreas cancer: Preliminary experience. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 2176–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, P.; Jiang, Y.; Kuder, T.A.; Bergmann, F.; Khristenko, E.; Steinle, V.; Kaiser, J.; Hackert, T.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Klauß, M. Diffusion kurtosis imaging—A superior approach to assess tumor–stroma ratio in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farace, P.; Merigo, F.; Fiorini, S.; Nicolato, E.; Tambalo, S.; Daducci, A.; Degrassi, A.; Sbarbati, A.; Rubello, D.; Marzola, P. DCE-MRI using small-molecular and albumin-binding contrast agents in experimental carcinomas with different stromal content. Eur. J. Radiol. 2011, 78, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.R.; O’Reilly, E.M. New Treatment Strategies for Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Drugs 2020, 80, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Pagel, M.D.; Kingsley, C.V.; Ma, J.; Long, J.P.; Wen, X.; Gammon, S.T.; Delacerda, J.; Javadi, S.; Li, C. Multiparametric MRI to Predict Response to Irreversible Electroporation Plus Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Magn. Reson. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, N.; Wang, Y.N.; D’Andrea, S.; Gravelle, K.M.; Hwang, J.H.; Lee, D. Noninvasive characterization of pancreatic tumor mouse models using magnetic resonance imaging. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winograd, R.; Byrne, K.T.; Evans, R.A.; Odorizzi, P.M.; Meyer, A.R.; Bajor, D.L.; Clendenin, C.; Stanger, B.Z.; Furth, E.E.; Wherry, E.J.; et al. Induction of T-cell Immunity Overcomes Complete Resistance to PD-1 and CTLA-4 Blockade and Improves Survival in Pancreatic Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Pickup, S.; Yankeelov, T.E.; Springer, C.S., Jr.; Glickson, J.D. Simultaneous measurement of arterial input function and tumor pharmacokinetics in mice by dynamic contrast enhanced imaging: Effects of transcytolemmal water exchange. Magn. Reson. Med. Off. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004, 52, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCastro, E.; Paudyal, R.; Konar, A.S.; LaViolette, P.S.; Akin, O.; Hatzoglou, V.; Goh, A.C.; Bochner, B.H.; Rosenberg, J.; Wong, R.J.; et al. A Quantitative Multiparametric MRI Analysis Platform for Estimation of Robust Imaging Biomarkers in Clinical Oncology. Tomography 2023, 9, 2052–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, T.M.; Xiao, S.; Manley, N.; Nikolich-Zugich, J.; Pugh, J.; Van den Brink, M.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Yasutomo, K.; Iwama, A.; Koyasu, S.; et al. An interlaboratory comparison of dosimetry for a multi-institutional radiobiological research project: Observations, problems, solutions and lessons learned. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2016, 92, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, P.; Marino, J.; Dodds, R.; Nadeem, S. DeepLIIF: An Online Platform for Quantification of Clinical Pathology Slides. Proc. IEEE Comput. Soc. Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 2022, 21399–21405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donati, F.; Casini, C.; Cervelli, R.; Morganti, R.; Boraschi, P. Diffusion-weighted MRI of solid pancreatic lesions: Comparison between reduced field-of-view and large field-of-view sequences. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 143, 109936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, S.; Motosugi, U.; Wakayama, T.; Morisaka, H.; Funayama, S.; Tamada, D.; Wang, K.; Mandava, S.; Cashen, T.A.; Onishi, H. An Intra-individual Comparison between Free-breathing Dynamic MR Imaging of the Liver Using Stack-of-stars Acquisition and the Breath-holding Method Using Cartesian Sampling or View-sharing. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 2023, 22, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagher-Ebadian, H.; Paudyal, R.; Nagaraja, T.N.; Croxen, R.L.; Fenstermacher, J.D.; Ewing, J.R. MRI estimation of gadolinium and albumin effects on water proton. Neuroimage 2011, 54, S176–S179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szomolanyi, P.; Rohrer, M.; Frenzel, T.; Noebauer-Huhmann, I.M.; Jost, G.; Endrikat, J.; Trattnig, S.; Pietsch, H. Comparison of the Relaxivities of Macrocyclic Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents in Human Plasma at 1.5, 3, and 7 T, and Blood at 3 T. Investig. Radiol. 2019, 54, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlak, C.S.; Blasberg, R.G.; Fenstermacher, J.D. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 1983, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J.R.; Bagher-Ebadian, H. Model selection in measures of vascular parameters using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI: Experimental and clinical applications. NMR Biomed. 2013, 26, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Cheng, X.-B.; Kohi, S.; Koga, A.; Hirata, K. Targeting hyaluronan for the treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2016, 6, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Harris, W.P.; Beck, J.T.; Berdov, B.A.; Wagner, S.A.; Pshevlotsky, E.M.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Gladkov, O.A.; Holcombe, R.F.; Korn, R.; et al. Phase Ib Study of PEGylated Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase and Gemcitabine in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2848–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Zheng, L.; Bullock, A.J.; Seery, T.E.; Harris, W.P.; Sigal, D.S.; Braiteh, F.; Ritch, P.S.; Zalupski, M.M.; Bahary, N. HALO 202: Randomized phase II study of PEGPH20 plus nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine versus nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine in patients with untreated, metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.-i.; Kawai, M.; Hirono, S.; Kojima, F.; Tanioka, K.; Terada, M.; Miyazawa, M.; Kitahata, Y.; Iwahashi, Y.; Ueno, M.; et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI predicts the histologic response for neoadjuvant therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer: A prospective study (DIFFERENT trial). Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2020, 405, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, T.; Saida, Y.; Kishimoto, S.; Lee, J.; Otowa, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Chandramouli, G.V.; Devasahayam, N.; Mitchell, J.B.; Krishna, M.C.; et al. PEGPH20, a PEGylated human hyaluronidase, induces radiosensitization by reoxygenation in pancreatic cancer xenografts. A molecular imaging study. Neoplasia 2022, 30, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudyal, R.; LoCastro, E.; Reyngold, M.; Do, R.K.; Konar, A.S.; Oh, J.H.; Dave, A.; Yu, K.; Goodman, K.A.; Shukla-Dave, A. Longitudinal Monitoring of Simulated Interstitial Fluid Pressure for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients Treated with Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, S.; Cuthill, I.C. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: A practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2007, 82, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilly, J.; Hoffman, M.T.; Abbassi, L.; Li, Z.; Paradiso, F.; Parent, B.D.; Hennessey, C.J.; Jordan, A.C.; Morgado, M.; Dasgupta, S.; et al. Mechanisms of Resistance to Oncogenic KRAS Inhibition in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 2135–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Choi, H.; Kemp, S.B.; Furth, E.E.; Pickup, S.; Clendenin, C.; Orlen, M.; Rosen, M.; Liu, F.; Cao, Q.; et al. Multimetric MRI Captures Early Response and Acquired Resistance of Pancreatic Cancer to KRAS Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello Joaquim, M.; Furth, E.E.; Fan, Y.; Song, H.K.; Pickup, S.; Cao, J.; Choi, H.; Gupta, M.; Cao, Q.; Shinohara, R.; et al. DWI Metrics Differentiating Benign Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms from Invasive Pancreatic Cancer: A Study in GEM Models. Cancers 2022, 14, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraoka, N.; Uematsu, H.; Kimura, H.; Imamura, Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Murakami, M.; Yamaguchi, A.; Itoh, H. Apparent diffusion coefficient in pancreatic cancer: Characterization and histopathological correlations. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2008, 27, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.P.B.; Jackson, A.; Parker, G.J.M.; Jayson, G.C. DCE-MRI biomarkers in the clinical evaluation of antiangiogenic and vascular disrupting agents. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, K.; Adema, G.J.; Bussink, J.; Ansems, M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor and radiotherapy: Interactions in the tumor micro-environment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Pickup, S.; Rosen, M.; Zhou, R. Impact of Arterial Input Function and Pharmacokinetic Models on DCE-MRI Biomarkers for Detection of Vascular Effect Induced by Stroma-Directed Drug in an Orthotopic Mouse Model of Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2023, 25, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.P.; Jackson, A.; Parker, G.J.; Roberts, C.; Jayson, G.C. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in clinical trials of antivascular therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 9, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Tempero, M.A.; Sigal, D.; Oh, D.Y.; Fazio, N.; Macarulla, T.; Hitre, E.; Hammel, P.; Hendifar, A.E.; Bates, S.E.; et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa with Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine for Patients with Hyaluronan-High Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3185–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value | Total Tumor Cells (/μm2) | Total Nuclei | Total Percentage of Tumor Cells (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (min, max) | 3408 (1403, 20,629) | 8650 (4696, 118,138) | 24 (15, 53) |

| Mean ± SD | 6633.0 ± 6867.0 | 32,283.0 ± 40,211.0 | 28.0 ± 11.0 |

| Model | Parameter | Values | |ΔrX (%)|(Unitless) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | |||

| Monoexponential | ADC × 10−3 (mm2/s) | 1.10 ± 0.09 | 1.31 ± 0.10 * | 20.50 ± 7.37 |

| Patlak Model | Ktrans (min−1) | 0.007 ± 0.003 | 0.0057 ± 0.002 * | 18.74 ± 7.4 |

| vp | 0.0460 ± 0.004 | 0.0350 ± 0.003 * | 23.78 ± 3.22 | |

| Extended Tofts Model | Ktrans (min−1) | 0.080 ± 0.025 | 0.063 ± 0.017 * | 20.41 ± 5.24 |

| ve | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.030 * | 23.23 ± 6.10 | |

| vp | 0.030 ± 0.007 | 0.025 ± 0.005 * | 17.93 ± 5.52 | |

| kep (min−1) | 0.66 ± 0.16 | 0.54 ± 0.14 * | 17.87± 7.87 | |

| Model | Parameter (Units) | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Monoexponential | ADC (×10−3 mm2/s) | 1.76 ± 0.0.56 |

| Patlak Model | Ktrans (min−1) | 0.095 ± 0.053 |

| vp | 0.067 ± 0.039 | |

| Extended Tofts Model | Ktrans (min−1) | 0.24 ± 0.12 |

| ve | 0.36 ± 0.11 | |

| vp | 0.043 ± 0.029 | |

| kep (min−1) | 0.70 ± 0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Paudyal, R.; Russell, J.; Lekaye, H.C.; Deasy, J.O.; Humm, J.L.; Awais, M.; Nadeem, S.; Do, R.K.G.; O’Reilly, E.M.; Schwartz, L.H.; et al. Tumor Microenvironment: Insights from Multiparametric MRI in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2026, 18, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020273

Paudyal R, Russell J, Lekaye HC, Deasy JO, Humm JL, Awais M, Nadeem S, Do RKG, O’Reilly EM, Schwartz LH, et al. Tumor Microenvironment: Insights from Multiparametric MRI in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020273

Chicago/Turabian StylePaudyal, Ramesh, James Russell, H. Carl Lekaye, Joseph O. Deasy, John L. Humm, Muhammad Awais, Saad Nadeem, Richard K. G. Do, Eileen M. O’Reilly, Lawrence H. Schwartz, and et al. 2026. "Tumor Microenvironment: Insights from Multiparametric MRI in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma" Cancers 18, no. 2: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020273

APA StylePaudyal, R., Russell, J., Lekaye, H. C., Deasy, J. O., Humm, J. L., Awais, M., Nadeem, S., Do, R. K. G., O’Reilly, E. M., Schwartz, L. H., & Shukla-Dave, A. (2026). Tumor Microenvironment: Insights from Multiparametric MRI in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers, 18(2), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020273