Simple Summary

Tivozanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Europe based on the results of a Phase III trial. To complement the data from the clinical trial, we conducted the post-approval study T-Rex to assess tivozanib’s safety, effectiveness and impact on the patients’ quality of life when used to treat patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma in routine clinical practice in Germany. The majority of the patients were over 75 years of age and did not previously receive treatment for renal cell carcinoma. Tivozanib was generally well tolerated and effective, with 46.9% of patients responding to treatment. Further benefits were reflected in the trend toward improved patient quality of life over the course of the study. Our findings support the use of tivozanib for the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, including those with advanced age, in routine clinical practice.

Abstract

Background: The efficacy and safety of tivozanib for the treatment of advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) have been established in the first-line setting in the Phase III trial TIVO-1. Methods: The prospective T-Rex study conducted in German clinical practice evaluated the safety, effectiveness and impact on quality of life (QoL) of first-line treatment with tivozanib in 32 patients with mRCC recruited between May 2019 and April 2021. Results: Recruited patients were predominantly elderly, with 53.1% aged over 75 years. Patients received a median of 6.5 tivozanib treatment cycles and the median time on treatment was 5.7 months. Overall, 78.1% of patients experienced treatment-related adverse events, including diarrhea, nausea and hypotension/hypertension. A clinical (i.e., complete or partial) response was observed in 46.9% of patients. Patients’ QoL remained stable from baseline to the end of treatment and most symptomatic toxicities resolved by the final treatment cycle, with the exclusion of dry skin, itching, and hand–foot syndrome. Conclusions: These data demonstrate that first-line treatment with tivozanib was associated with clinical activity, favorable tolerability, and stable QoL in patients with mRCC treated in everyday clinical practice across Germany, including those with advanced age.

1. Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of kidney cancer, accounting for ~90% of all kidney tumors, and ~3% of all cancers globally [1,2]. Clear cell RCC constitutes 80% of malignant renal tumors in adults, with papillary RCCs representing the majority of the remaining 20% of RCC cases [1]. The incidence of RCC typically peaks between the ages of 60 and 70 years and most patients are diagnosed with RCC over the age of 65 years [3]. Approximately 16% of patients with RCC present with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) at diagnosis, and up to 20% of those initially diagnosed with localized RCC will develop metastases over the course of their disease [4,5].

Prior to the introduction of targeted therapies for mRCC, patients were treated with high-dose interleukin-2 or interferon-α, achieving median survival rates of <20 months [6,7]. The shift from these non-targeted therapies to targeted treatments, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, has resulted in improved survival rates [8,9,10,11]. For example, in the COMPARZ and TIVO-1 studies, treatment with TKI monotherapy (pazopanib or sunitinib and sorafenib or tivozanib, respectively) demonstrated median overall survival rates of >28 months [9,10]. Overall survival improved even further in the era of ICI combination therapies [12,13,14,15].

Treatment decisions in patients with mRCC are guided by the stratification of patients into risk groups (favorable-, intermediate-, and poor-risk) proposed by the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) [1,16]. Recent evidence suggests that patients classified as favorable-risk (0 risk factors) have a higher proportion of angiogenic tumors and thus, are more sensitive to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-targeted therapies, compared with those in the intermediate- or poor-risk categories, [17,18,19]. VEGF plays a key role in tumor angiogenesis and vascular permeability, with VEGF overproduction shown to promote disease progression in patients with mRCC [4,20,21,22].

Combination therapy with ICIs and VEGF receptor-TKI is recommended as a first-line therapy in patients with clear cell RCC regardless of IMDC risk group [1,23]. However, monotherapy with TKIs, such as tivozanib, is recommended as an alternative to combination therapy in the IMDC favorable-risk group, or when ICI therapy is contraindicated [1,23]. While Phase III trials demonstrated robust survival benefits for regimens combining TKIs with ICIs in the overall patient population, subgroups of patients with intermediate- and poor-risk prognosis derived the most benefit, with mixed results in the favorable-risk subgroup [12,13,24,25,26]. These data suggest that the favorable-risk category is enriched for patients with angiogenic tumors who derive a greater survival advantage from VEGF-targeted therapies compared with those in the intermediate- and poor-risk categories [16]. Observations regarding the survival benefit of ICI combinations and TKI monotherapy across IMDC subgroups are reflected in the European Association of Urology (EAU) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines, which recommend TKI monotherapy for favorable-risk patients as an alternative to ICI combinations, and for all risk groups when ICI treatments are contraindicated [1,23].

One of the VEGFR-TKIs recommended for the treatment of mRCC is tivozanib, which is approved in Europe as first-line treatment for advanced RCC, and as second-line treatment in VEGFR and mTOR inhibitor-naïve patients with advanced RCC after disease progression following cytokine therapy [27]. Approval of tivozanib was based on the results of TIVO-1, a Phase III, multicenter, open-label, randomized study demonstrating superiority of tivozanib over sorafenib in both progression-free survival and objective response rate [10,27].

While clinical trials are important for evaluating the safety and efficacy of new therapies, they are subject to time limitations and strict eligibility criteria [28,29,30,31]. Post-approval studies can complement clinical trials by providing long-term data in a more diverse group of patients, thereby reducing selection bias and more accurately reflecting the target patient population seen in clinical practice [28,32,33]. Notably, while elderly patients are not always excluded from clinical trials based on age at enrollment [12,25,34,35,36], recruitment protocols may implicitly select for younger populations by restricting entry for individuals on the grounds of factors such as performance status, organ function or burden of study procedures [36,37,38]. In addition, post-approval studies sometimes evaluate patient-reported outcomes (PRO), which provide insight into the impact of a therapy from the perspective of the patient and can support clinical decision-making, facilitate communication between patients and healthcare professionals, and enable the monitoring of patient well-being and QoL in clinical practice [39,40,41].

Here, we report the results of the prospective, post-approval study T-Rex that evaluated the effectiveness, safety, and impact on QoL of tivozanib in patients with advanced or mRCC in routine clinical practice in Germany.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

The T-Rex study was a prospective, non-interventional, post-approval study of tivozanib in patients with advanced or mRCC. Recruitment commenced on 21 May 2019 and stopped early on 30 April 2021. During this period, patients diagnosed with advanced or mRCC were recruited in 23 centers across Germany, 21 of which had patients who received first-line treatment with tivozanib under clinical practice conditions and were eligible for this analysis. The database was closed on 15 November 2021. Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with advanced or mRCC, with or without measurable disease according to RECIST 1.1 or based on clinical criteria at enrolment. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of tivozanib as well as its impact on QoL in patients with advanced or mRCC.

2.2. Study Endpoints and Assessments

The primary endpoints were the incidence of treatment-related adverse events and serious adverse events during the study and up to 30 days following the last dose of tivozanib, and PRO (QoL and tolerability to treatment). Secondary endpoints included tivozanib-related treatment discontinuations and hospitalizations, clinical response rate, duration of response, progression-free survival and duration of tivozanib treatment.

Tumor assessments were performed using imaging at intervals indicated by the treating physician and tumor response was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) Version 1.1, where available, or according to non-standardized clinical criteria. The clinical response rate was defined as the proportion of patients with complete and partial response. Progression-free survival was defined as the length of time from treatment initiation to disease progression or death and was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method [42,43].

Safety assessments included the incidence of adverse events, rates of hospitalization and treatment discontinuation. Treatment-related adverse events and serious adverse events were monitored throughout the study and up to 30 days following the last dose of tivozanib and evaluated according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE [V4.0]).

PRO included QoL and tolerability to treatment and were assessed using questionnaires, which were completed by all patients following every other tivozanib treatment cycle. QoL was assessed using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy—Kidney Symptom Index (19-item version; NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 [Version 2]) questionnaire and the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). The NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 captures patient-reported data on QoL sub-scales over the previous seven days. In our study, the following four statements from the FKSI were chosen as they focus on emotional symptoms and functional well-being. Thus following patient responses were evaluated: ‘I am able to work (include work at home)’, ‘I am able to enjoy life’, ‘I am content with the quality of my life right now’, and ‘I worry that my condition will get worse’ [44]. For scores on the sub-scales ‘I am able to work (include work at home)’, ‘I am able to enjoy my life’, and ‘I am content with the quality of my life right now’ a higher score indicates improved patient QoL, whereas a higher score for the sub-scale ‘I worry that my condition will deteriorate’ suggests worsening of QoL. The PRO-CTCAE is a PRO measure that assesses up to 124 items relating to the attributes (frequency, severity, and interference with daily activities) of symptomatic toxicities experienced by patients over the previous seven days [45]. In the present study, a customized version with 61 items was evaluated. Attributes of reported toxicities were scored by patients from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating the absence of the symptom and lower scores indicating greater frequency, severity and interference with daily activities.

All statistical analyses were descriptive. Both the effectiveness and safety populations included all patients treated with tivozanib in the first-line setting.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

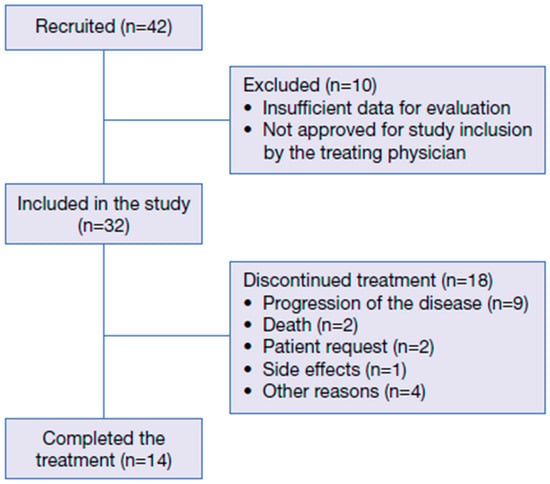

Overall, 42 patients were included in the study; however, ten patients did not have sufficient data for evaluation and/or were not approved for study inclusion by the treating physician (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

Baseline patient and treatment characteristics of all 32 evaluated patients are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were male (59.4%) and the median age was 77.5 years (range 61.0–89.0), with six (18.8%), nine (28.1%) and 17 (53.1%) patients aged ≤65 years, 66–75 years and >75 years, respectively. Twenty-one patients (65.6%) had a favorable European Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of 0, nine (28.1%) had a score of 1 and two (6.3%) had a score of 2. The majority of patients (n = 22, 68.8%) had an intermediate IMDC risk score, seven (21.8%) had a favorable and three (9.4%) a poor risk score. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), when excluding index points given for age and the presence of solid tumors, was 3.5 (SD 3.36) (men: 3.0 [SD 2.97]; women: 4.4 [SD 3.69]). Among the 32 patients, 16 (50%) had lung metastases, 4 (12.5%) had bone metastases, 4 (12.5%) had liver metastases, 3 (9.4%) had adrenal gland metastases, and 12 (37.5%) had metastases at other locations.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

During the study, each patient received a median of 6.5 tivozanib treatment cycles (range 1–35) and the median time on treatment was 5.7 months (range 0.4–32.7). Tivozanib was administered at a starting dose of 1340 micrograms in 26 patients (81.3%) and at 890 micrograms in six patients (18.8%); however, the reason for this was not documented. Pre- or co-medication was required by nine patients (28.1%) and reasons for use included emesis (n = 3 [9.4%]), infection (n = 2 [6.3%]), skin reactions (n = 1 [3.1%]), allergic reactions (n = 1 [3.1%]) and ‘other reasons’ (n = 8 [25.0%]); some patients required pre- or co-medication for more than one reason. Prednisolone was administered in one patient (3.1%) and another active ingredient was administered in four patients (12.5%).

3.2. Safety Outcomes

Treatment-related adverse events were experienced by 25 patients (78.1%). Grade 1–2 events included diarrhea (n = 6 [18.8%]), nausea (n = 7 [21.9%]), stomatitis (n = 2 [6.3%]), peripheral neuropathy (n = 1 [3.1%]), emesis (n = 1 [3.1%]), and alopecia (n = 1 [3.1%]) (Table 2). Adverse events that were not graded and were experienced by ≥5% of patients included hypotension/hypertension (n = 5 [15.6%]), skin changes (n = 3 [9.4%]), neurologic disorders (n = 2 [6.3%]), paresthesia (n = 2 [6.3%]), fatigue (n = 2 [6.3%]), and ‘other’ (n = 22 [68.8%]). Grade 3–4 adverse events included cardiac dysfunction (n = 2 [6.3%]), diarrhea (n = 2 [6.3%]), ataxia (n = 1 [3.1%]), aphonia (n = 1 [3.1%]), pericardial effusion (n = 1 [3.1%]), and ‘other’ (n = 5 [15.6%]).

Table 2.

Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade occurring during the study and up to 30 days following the last dose of tivozanib.

Treatment interruption and dose reduction were required in eight patients (25.0%) each. Seven patients (21.9%) required a dose reduction due to adverse events and one patient (3.1%) requested a dose reduction. Nine patients (28.1%) required hospitalization; however, the reasons were not documented. Early treatment discontinuations occurred in seven patients (21.9%) and were due to patient request (n = 2 [6.3%]), adverse events (n = 1 [3.1%]) and ‘other reasons’ (n = 4 [12.5%]).

3.3. Patient Reported Outcomes

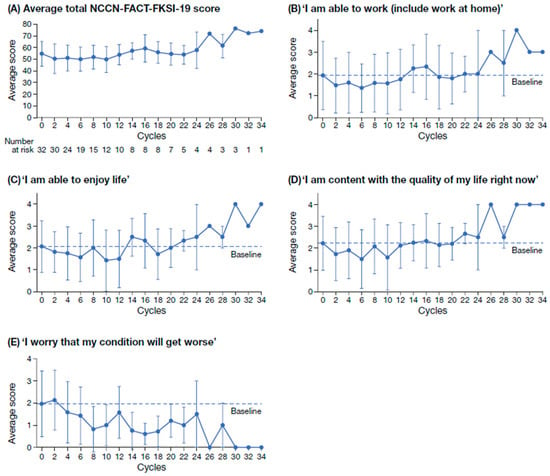

In total, 149 NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 questionnaires were completed by patients treated with tivozanib. Per cycle, a minimum of 1 questionnaire and a maximum of 22 questionnaires were completed. The overall completion rate of the NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 was 76.8% (Figure 2 and Figure S1). At baseline, questionnaire completion rate per patient was 100% (n = 32); however, the number of patients completing the questionnaire decreased over the course of the study. For all 19 QoL items evaluated using the PRO questionnaire NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19, there was no decrease in the mean score with increasing cycles (Figure 2A). For the sub-scales ‘I am able to work (include work at home)’, ‘I am able to enjoy life’, and ‘I am content with the quality of my life right now’, mean NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 scores generally increased from cycle 2 to cycle 34 (Figure 2B–D). For the sub-scale ‘I worry that my condition will get worse’, the mean NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 score generally decreased from cycle 2 to cycle 34 (Figure 2E). For the remaining 15 NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 scores, the same trend of improvement over time was observed (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Average total NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 score at alternating treatment cycles (A) and scores on the QoL sub-scales ‘I am able to work (include work at home)’ (B); ‘I am able to enjoy life’ (C); ‘I am content with the quality of my life right now’ (D); ‘I worry that my condition will get worse’ (E). Scores on the sub-scales in B–E range from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19, National Comprehensive Cancer Network Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy—Kidney Symptom Index; QoL, quality of life.

For most of the symptomatic toxicities evaluated with the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire, the frequency and severity of the symptoms, as well as their interference with normal daily activities, decreased from baseline to cycle 34. While the majority of symptoms appeared to resolve prior to cycle 34 in most patients, one patient reported the severity of dry skin, itching and hand–foot syndrome worsened from baseline to cycle 34; dry skin was reported to be ‘fairly’, and both itching and hand–foot syndrome were reported to be ‘moderate’ at study completion. As with the NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19, the proportion of patients completing the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire decreased as the study continued.

3.4. Effectiveness Outcomes

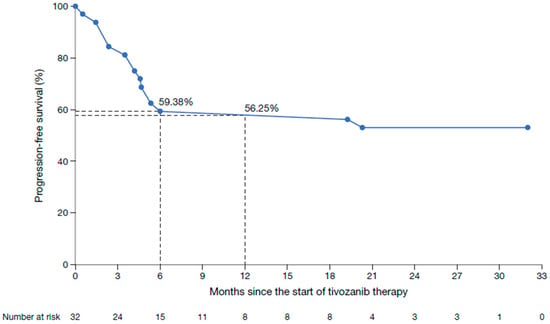

Clinical response rate was reported in 15 patients (46.9%), with six patients (18.8%) achieving a complete response and nine patients (28.1%) a partial response (Table 3). Stable disease was reported in four patients (12.5%), giving a clinical disease control rate of 59.4%. Progressive disease in patients without prior response was observed in nine patients (28.1%). The clinical progression-free survival rates were 59.4% after 6 months and 56.3% after 12 months of tivozanib treatment (Figure 3); median clinical progression-free survival was not reached. Treatment with tivozanib was discontinued in 11 patients (34.4%); 9 (28.1%) discontinued due to disease progression and two patients (6.3%) died while receiving study treatment.

Table 3.

Clinical tumor response following first-line treatment with tivozanib.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of clinical progression-free survival in patients treated with tivozanib in a first-line setting.

4. Discussion

The prospective, non-interventional T-Rex study evaluated the safety, effectiveness and impact on QoL of tivozanib in patients with advanced or mRCC treated in post-approval clinical practice across Germany. Our results demonstrate that first-line treatment with tivozanib was generally well tolerated, with no new safety signals observed during the study. Tivozanib also demonstrated efficacy and maintained QoL in our study population.

As expected, the baseline characteristics of the patient population included in this study differ from those of the population included in the pivotal Phase III clinical trial, TIVO-1, which investigated the efficacy and safety of tivozanib in comparison with sorafenib in patients with mRCC [10]. Compared with patients included in TIVO-1, the population enrolled in T-Rex had a higher median age (77.5 years versus 59.0 years) and included a greater proportion of patients with a favorable ECOG PS of 0 (65.6% versus 49.3%). However, while TIVO-1 only included patients with an ECOG PS ≤ 1, the T-Rex study enrolled two patients (6.3%) with an unfavorable ECOG PS of 2. Advanced age may be associated with patient frailty and vulnerability in the clinical setting [46], and recent evidence suggests that frailty can affect >50% of older patients with cancer [47]. The median patient age in T-Rex (77.5 years) was also higher compared with that of patient populations included in other Phase III studies in advanced or mRCC, which included patient populations with a median age of approximately 60 years [12,13,24,25]. In T-Rex, 81.3% of the population were aged >65 years, suggesting that a large proportion of this population would be at risk of frailty. This observation is further supported by the high number of patients with comorbidities, as indicated by the high mean CCI score. Although such data are lacking for pivotal TKI trials such as TIVO-1, they emphasise the influence of competing risks and comorbidities in patients in routine clinical practice.

In this post-approval study, first-line treatment with tivozanib resulted in a clinical response rate of 46.9%, confirming its effectiveness in everyday clinical practice, including in elderly patients, who, as discussed above, have a high probability of being frail. Clinical progression-free survival rates at 6 and 12 months were comparable between the T-Rex study and the cohort receiving tivozanib in TIVO-1, despite T-Rex including a patient population that was older than that in TIVO-1. Consistent with our findings, another post-approval study of tivozanib reported a significant improvement in PFS, with greater benefits seen in patients with metastatic RCC treated in the first-line setting [48]. The safety profile of tivozanib in T-Rex was similar to that reported previously [10,27,49,50], despite the advanced age and associated comorbidities of the study population, as measured by the CCI. Overall, adverse events were experienced by 78.1% of patients, primarily diarrhea, nausea and hypertension/hypotension, and no new safety signals were observed. This incidence is slightly lower than that reported in TIVO-1, where adverse events occurred in 93.6% of patients, with hypertension, diarrhea and dysphonia being the most commonly observed [10]. Furthermore, the T-Rex study reported low rates of grade 3–4 adverse events, such as cardiac dysfunction (6.3%) and diarrhea (6.3%). These rates were comparable to, or lower than, those observed in the TIVO-1 trial, which reported grade 3–4 hypertension in 27% and diarrhea in 2% of patients [10]. In another post-approval study of first-line tivozanib use in patients with RCC, the tolerability of tivozanib appears favorable vs. other TKIs in this setting, but the authors noted that adverse events are likely to be under-recorded in real-world studies [51]. Additionally, outcomes cannot be directly compared between studies due to differences in study design and patient populations. It is also generally accepted that real-world studies are less accurate than clinical trials in the reporting of adverse events [32]. In total, 9 patients experienced 12 serious adverse events over the course of the study, further demonstrating the favorable tolerability profile of tivozanib in our patient population. The safety of other TKIs, including cabozantinib, sunitinib and pazopanib, has been evaluated in other real-world studies, which reported comparable findings to the T-Rex study [52,53]. In these studies, adverse events were observed in 91% of patients [52], while grade ≥ 3 events occurred in 22–33% [52,53].

The T-Rex study also evaluated PRO, which are an important tool for the assessment of the patients’ QoL and are valuable in guiding treatment decisions and improving patient well-being [39,41,54]. Patient scores generally improved for all items included in the NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 questionnaire, suggesting that overall patient QoL was maintained throughout the duration of the study [9]. For the sub-scales ‘I am able to work (include work at home)’, ‘I am able to enjoy life’, and ‘I am content with the quality of my life right now’, scores increased over the course of the study. Patients also reported improvements in their overall condition with continued tivozanib use, with scores generally decreasing for the sub-score ‘I worry that my condition will get worse’. The absence of a decline in these PRO items potentially indicates that therapy management allowed patients to adapt to treatment toxicities and the burden of treatment. However, drop-outs, missing PRO assessments and a small sample size limit the interpretation of the data. According to patient responses on the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire, the frequency, severity, and interference with normal daily activities of most of the evaluated symptomatic toxicities decreased from baseline to study completion. However, the evaluation of PRO was challenging, as the number of patients completing the questionnaires reduced throughout the course of the study, introducing selection bias to the results.

There are several important limitations to consider regarding this study. Firstly, the small sample size included in T-Rex makes it challenging to interpret the results and draw conclusions from the study. Secondly, the lack of a comparator further limits the interpretability of these findings, which is, however, inherent to non-interventional studies. In addition, the absence of standardized imaging assessments for tumor evaluation may have introduced variations in response assessment across treatment centers. Finally, it is possible that adverse events were underreported. Despite these limitations, the present study provides meaningful evidence on the clinical effectiveness, safety profile and impact on QoL of first-line treatment with tivozanib in patients with advanced and mRCC, complementing data from other global clinical trials.

5. Conclusions

First-line treatment with tivozanib demonstrated relevant clinical activity and favorable tolerability in patients with advanced or mRCC in routine clinical practice in Germany, including elderly and potentially frail patients. The results of this study support the use of tivozanib for the first-line treatment of patients with advanced or mRCC suitable for single-agent TKI treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers17243910/s1, Figure S1: Proportion of patients completing the NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 questionnaire at alternate treatment cycles; Figure S2: NCCN-FACT-FKSI-19 score on the QoL sub-scales.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: V.G., M.H. (Martin Herold), B.I.L.; Data curation: V.G.; Formal analysis: V.G.; Investigation: V.G., K.R., R.E., S.S., D.S., M.H. (Miriam Hegemann), S.B., H.B., M.S., O.R., S.S.-M., E.H., C.F.F., C.D., C.Z., A.D., N.M., P.I., C.L., A.J., M.B.; Methodology: V.G.; Project administration: M.H. (Martin Herold), B.I.L.; Supervision: V.G.; Validation: V.G., M.H. (Martin Herold), B.I.L.; Writing—original draft: V.G.; Writing—reviewing and editing: V.G., M.H. (Martin Herold), B.I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Recordati Rare Diseases Germany GmbH sponsored the T-Rex study and funded editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and is registered with the Federal Institute for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Products (#7296). The study received ethical approval on 25.02.19 and was registered on the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices database on 31.10.19. This non-investigational study received professional legal advice from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen according to §15 of the professional code, prior to carrying out this research (18-8501-BO).

Informed Consent Statement

All patients provided informed consent prior to enrolling in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices at https://awbdb.bfarm.de/ords/r/awb/awb/anzeigedetails?p2_anzeige_id=40BB22D754093D83E063140810AC1B5D&clear=2 (accessed on 1 November 2025) or ID 7296.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Summer Tredgett of mXm Medical Communications. Statistical and operational support was provided by NCO GmbH.

Conflicts of Interest

VG received speakers fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Eisai, MSD, Merck KGa, AstraZeneca, AAA/Novartis, Amgen, Johnson & Johnson, Teilx Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences and Roche. VG also received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis, MSD, Ipsen, Johnson & Johnson, Eisai, Debiopharm, Gilead Sciences, Oncorena, Synthekine, Recordati Rare Diseases Germany GmbH. He also received travel expenses from Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Merck KGa, Ipsen and Amgen. SS participated in advisory boards for Astellas, Bayer, BMS, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, MSD, and Novartis and has given lectures for Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Johnson and Johnson, MSD, and Novartis. DS received honoraria/consultation fees from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Ipsen, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Serono, MSD Oncology, Novartis, and Pfizer. MHeg received consultation fees from Roche, Pfizer, BMS, Merck, Eusa-Pharm and Novartis, has given letures for Novartis, Janssen, Eisai, Ipsen, Astellas and Merck, provided conference support for Ipsen, Janssen, Pfizer and Merck, participated in study activites for Janssen, Ipsen, Eusa-Pharm and Accord, was a DGP mandate holder for the S3 guideline on bladder cancer and is a member of DGU, GESRU, EAU, DPG, BvDU, DÄB, DieChirurginnen e.V. HB was a member of the advisory board for Johnson and Johnson. EH received consultation fees from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Ipsen, Johnson and Johnson, MSD, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche, and honoraria from Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Ipsen, Johnson and Johnson, MSD, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Sandoz. She also received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Ipsen, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, and Sandoz. CD received honoraria/consultation fees from Amgen, Apogepha, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Merck Serono, MSD Oncology, and Recordati Rare Diseases Germany GmbH. CD is a stock shareholder of AstraZeneca and Merck Serono, and received travel expenses from Apogepha, BMS, EUSA Pharm, Ipsen, Merck Serono, MSD, and Recordati Rare Diseases Germany GmbH. NM is the Chief Scientific Officer and shareholder of IOMEDICO AG, Freiburg, and serves as an advisor for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beigene, BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Deloitte, GILEAD, GSK, IPSEN, J&J, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Onkovis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Seagen, Servier and Stemline. PI received the advisory fees from and gave expert testimony to BMS, Bayer, ClinSol, Deciphera, EISAI, EMD-Serono, EUSA, H5-Oncology, Ipsen, Merck Serono (Global), Metaplan, MSD, Onkowissen, Pfizer and Roche. He also obtained lecture honoraria from AIM, Apogepha, Astra Zeneca, Astella, BMS, Bayer (+Europe, Global), CORE2ED, Deciphera, DKG-Onkoweb, EISAI, EUSA, FoFM, Id-Institut, Ipsen (Europe), Merck Serono (+Europe, Global), MSD, MedKom, MTE-Academy, MedWiss, New Concept Oncology, Onkowissen-tv.de, Pharma Mare, Pfizer, Roche, ThinkWired!, Schmitz-Communikation, StreamedUP!, Solution Academy and Vivantis. In addition, he received clinical trials/research grants from AIO, AstraZeneca, BMS, GSK, Ipsen, Lilly, Merck Serono, Niedersächsische Krebsgesellschaft, Novartis, EUSA, EISAI, Pfizer, MSD, Roche, Stiftung Immunonkologie and Wilhelm Sander Stiftung, and travel grants/others from BB-Biotech, BMS, Bayer, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Thoraxchirurgie, EUSA, Ipsen, Merck and Pharma Mare. PI’s non-financial conflicts of interest are as follows: Member of German Working Party Medical Oncology (AIO), Member of the German Cancer Society, ASCO Member, ESMO Member, Member of Oncological Working Party Hannover (OAK), Spokesman, Interdisciplinary Working Party—Kidney Cancer (IAGN-DKG), Steering Board Immunooncologic Cooperative Group (ICOG-H) and Clinical Trial Steering Committee CCC-H. MHer and BIL are employees of Recordati Rare Diseases Germany GmbH. MB received fees from EUSA Pharma for participation in advisory boards and giving talks. KR, RE, SB, MSe, OR, SS-M, CFF, CZ, AD, CL and AJ have nothing to declare.

References

- Powles, T.; Albiges, L.; Bex, A.; Comperat, E.; Grünwald, V.; Kanesvaran, R.; Kitamura, H.; McKay, R.; Porta, C.; Procopio, G.; et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungberg, B.; Bex, A.; Albiges, L.; Bedke, J.; Capitanio, U.; Dabestani, S.; Hora, M.; Klatte, T.; Kuusk, T.; Lund, L.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma. Available online: https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Renal-Cell-Carcinoma-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A.; Thandra, K.C.; Saginala, K.; Mohammed, A.; Vakiti, A.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. World J. Oncol. 2020, 11, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serzan, M.T.; Atkins, M.B. Current and emerging therapies for first line treatment of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, S.; Lacin, S. Impact of tivozanib on patient outcomes in treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 7779–7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canil, C.; Hotte, S.; Mayhew, L.A.; Waldron, T.S.; Winquist, E. Interferon-alfa in the treatment of patients with inoperable locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2010, 4, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, J.A.; Downey, S.G.; Smith, F.O.; Yang, J.C.; Hughes, M.S.; Kammula, U.S.; Sherry, R.M.; Royal, R.E.; Steinberg, S.M.; Rosenberg, S. High-dose interleukin-2 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A retrospective analysis of response and survival in patients treated in the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute between 1986 and 2006. Cancer 2008, 113, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furubayashi, N.; Negishi, T.; Yamashita, T.; Kusano, S.; Taguchi, K.; Shimokawa, M.; Nakamura, M. Progression-free survival of first-line treatment with molecular-targeted therapy may be a meaningful intermediate endpoint for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 7, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sternberg, C.N.; Motzer, R.J.; Hutson, T.E.; Choueiri, T.K.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Nathan, P.; Porta, C.; Grünwald, V.; Dezzani, L.; et al. COMPARZ Post Hoc Analysis: Characterizing Pazopanib Responders With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019, 17, 425–435.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Nosov, D.; Eisen, T.; Bondarenko, I.; Lesovoy, V.; Lipatov, O.; Tomczak, P.; Lyulko, O.; Alyasova, A.; Harza, M.; et al. Tivozanib versus sorafenib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from a phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3791–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Rini, B.I.; McDermott, D.F.; Redman, B.G.; Kuzel, T.M.; Harrison, M.R.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; Drabkin, H.A.; George, S.; Logan, T.F.; et al. Nivolumab for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results of a Randomized Phase II Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1430–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grünwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.Y.; Merchan, J.; Goh, J.C.; et al. Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab Versus Sunitinib in First-Line Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: Final Prespecified Overall Survival Analysis of CLEAR, a Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Apolo, A.B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Shah, A.Y.; Suárez, C.; Porta, C.; Barrios, C.H.; Richardet, M.; et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended follow-up from the phase III randomised CheckMate 9ER trial. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plimack, E.R.; Powles, T.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Nosov, D.; Waddell, T.; Alekseev, B.; Pouliot, F.; Melichar, B.; Soulières, D.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Axitinib Versus Sunitinib as First-line Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: 43-month Follow-up of the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-426 Study. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannir, N.M.; Albigès, L.; McDermott, D.F.; Burotto, M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Hammers, H.J.; Barthélémy, P.; Plimack, E.R.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended 8-year follow-up results of efficacy and safety from the phase III CheckMate 214 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, D.Y.; Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Warren, M.A.; Golshayan, A.R.; Sahi, C.; Eigl, B.J.; Ruether, J.D.; Cheng, T.; North, S.; et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: Results from a large, multicenter study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5794–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Zang, D.Y. Prognostic and predictive value of VHL gene alteration in renal cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis and review. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 13979–13985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Shim, B.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, I.H. Loss of Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) Tumor Suppressor Gene Function: VHL-HIF Pathway and Advances in Treatments for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Banchereau, R.; Hamidi, H.; Powles, T.; McDermott, D.; Atkins, M.B.; Escudier, B.; Liu, L.F.; Leng, N.; Abbas, A.R.; et al. Molecular Subsets in Renal Cancer Determine Outcome to Checkpoint and Angiogenesis Blockade. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 803–817.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, R.S.; Chen, D.S.; Ferrara, N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell 2019, 176, 1248–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, I.; Pircher, A.; Pichler, R. Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment in Renal Cell Cancer Biology and Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Song, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Ma, G.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y. Expression levels of VEGF-C and VEGFR-3 in renal cell carcinoma and their association with lymph node metastasis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bex, A.; Albiges, L.; Bedke, J.; Capitanio, U.; Dabestani, S.; Hora, M.; Klatte, T.; Kuusk, T.; Lund, L.; Marconi, L.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma. Available online: https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Renal-Cell-Carcinoma-2025_2025-04-17-105637_dkgm.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Choueiri, T.K.; Penkov, K.; Uemura, H.; Campbell, M.T.; Pal, S.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Lee, J.L.; Venugopal, B.; van den Eertwegh, A.J.M.; Negrier, S.; et al. Avelumab + axitinib versus sunitinib as first-line treatment for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: Final analysis of the phase III JAVELIN Renal 101 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Waddell, T.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma: 5-year survival and biomarker analyses of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-426 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3475–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. OPDIVA Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/opdivo-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Fotivda Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fotivda-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Karim, S.; Xu, Y.; Kong, S.; Abdel-Rahman, O.; Quan, M.L.; Cheung, W.Y. Generalisability of Common Oncology Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria in the Real World. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, e160–e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akobeng, A.K. Principles of evidence based medicine. Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.R. Fundamentals of clinical trial design. J. Exp. Stroke Transl. Med. 2010, 3, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariton, E.; Locascio, J.J. Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG 2018, 125, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, M.; Perrone, F.; Conte, P. Real-World Evidence in Oncology: Opportunities and Limitations. Oncologist 2020, 25, e746–e752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petracci, F.; Ghai, C.; Pangilinan, A.; Suarez, L.A.; Uehara, R.; Ghosn, M. Use of real-world evidence for oncology clinical decision making in emerging economies. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 2951–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Porta, C.; Suárez, C.; Hainsworth, J.; Voog, E.; Duran, I.; Reeves, J.; Czaykowski, P.; Castellano, D.; Chen, J.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Sapanisertib ± TAK-117 vs. Everolimus in Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma After VEGF-Targeted Therapy. Oncologist 2022, 27, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Arén Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, M.E.; Stauder, R.; van Munster, B.C. Exclusion of older patients from ongoing clinical trials for hematological malignancies: An evaluation of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Trial Registry. Oncologist 2014, 19, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.; Willoughby, C.; Messer, D.; Lux, M.; Aitken, M.; Getz, K. Assessing Participation Burden in Clinical Trials: Introducing the Patient Friction Coefficient. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, e150–e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, C.M.; Wallen, G.R.; Feister, A.; Grady, C. Respondent burden in clinical research: When are we asking too much of subjects? IRB Ethics Hum. Res. 2005, 27, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.T.; Chan, A.; Charalambous, A.; Darling, H.S.; Eng, L.; Grech, L.; van den Hurk, C.J.G.; Kirk, D.; Mitchell, S.A.; Poprawski, D.; et al. The use of patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer care: Preliminary insights from a multinational scoping survey of oncology practitioners. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruszczyk, K.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Cardoso, V.R.; Gkoutos, G.V.; Slater, L.T.; Collis, P.; Keeley, T.; Calvert, M.J. Implementation of patient-reported outcome measures in real-world evidence studies: Analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov records (1999–2021). Contemp. Clin. Trials 2022, 120, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.C.; Kyte, D.G.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Slade, A.L.; McMullan, C.; Calvert, M.J. The impact of patient-reported outcome (PRO) data from clinical trials: A systematic review and critical analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. In Breakthroughs in Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1958; Volume 53, pp. 319–337. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, W.N.; Wickham, R.; Coombs, N. An Introduction to Survival Statistics: Kaplan-Meier Analysis. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2016, 7, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN-FACT FKSI-19 (Version 2). Available online: https://www.facit.org/_files/ugd/c0dc3a_553da8c1429c49ac8ccae0ea485b6f9f.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- National Cancer Institute. NCI-PRO-CTCAE® ITEMS-ENGLISH. Available online: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/instruments/pro-ctcae/pro-ctcae_english.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ethun, C.G.; Bilen, M.A.; Jani, A.B.; Maithel, S.K.; Ogan, K.; Master, V.A. Frailty and cancer: Implications for oncology surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.W.; Tang, W.R.; Chen, S.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Chen, J.S.; Hung, Y.S.; Chou, W.C. Association of frailty and chemotherapy-related adverse outcomes in geriatric patients with cancer: A pilot observational study in Taiwan. Aging 2021, 13, 24192–24204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehler, M.; Spek, A.K.; Rodler, S.; Schott, M.; Casuscelli, J.; Mittelmeier, L.; Schlemmer, M. Real-World Results from One Year of Therapy with Tivozanib. Kidney Cancer 2019, 3, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agulnik, M.; Costa, R.L.B.; Milhem, M.; Rademaker, A.W.; Prunder, B.C.; Daniels, D.; Rhodes, B.T.; Humphreys, C.; Abbinanti, S.; Nye, L.; et al. A phase II study of tivozanib in patients with metastatic and nonresectable soft-tissue sarcomas. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountzilas, C.; Gupta, M.; Lee, S.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Estfan, B.; Wang, K.; Attwood, K.; Wilton, J.; Bies, R.; Bshara, W.; et al. A multicentre phase 1b/2 study of tivozanib in patients with advanced inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heseltine, J.; Allison, J.; Wong, S.; Prasad, K.; Oong, Z.C.; Wong, H.; Law, A.; Charnley, N.; Parikh, O.; Waddell, T.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Tivozanib Monotherapy as First-Line Treatment for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Multicentric UK Real-World Analysis. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellato, M.; Sepe, P.; Bronte, E.; Conteduca, V.; Rocca, M.C.; De Giorgi, U.; Di Napoli, M.; Galli, L.; Incorvaia, L.; Lalli, L.; et al. Real-life Use of Cabozantinib in Front-line therapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: The CabFRONT Study (Meet-URO 24). Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 82, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikic, P.; Babovic, N.; Dzamic, Z.; Salma, S.; Stojanovic, V.; Matkovic, S.; Pejcic, Z.; Juskic, K.; Soldatovic, I. Real World Overall Survival of Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated With Only Available Sunitinib and Pazopanib in First-Line Setting. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 892156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottomley, A.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Koller, M.; Flechtner, H.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Greimel, E. Current state of quality of life and patient-reported outcomes research. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).