Simple Summary

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been linked to esophageal cancer, but its association with extraesophageal malignancies remains unclear. Clarifying these risks may inform clinical surveillance strategies. This systematic review and meta-analysis found significant associations between GERD and increased risks of pharyngeal, laryngeal, and lung cancers, with Mendelian randomization supporting a potential causal relationship to lung cancer. The potential extraesophageal malignancies risks associated with GERD highlight the need for greater awareness and may support the development of targeted risk assessment or monitoring approaches.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and extraesophageal malignancies remains unclear. This study aimed to systematically evaluate the relationship between GERD and these cancers. Methods: PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science were searched for studies reporting risk estimates—risk ratios (RRs), odds ratios (ORs), hazard ratios (HRs), or standardized incidence ratios (SIRs)—of GERD and extraesophageal malignancies. Mendelian randomization (MR) studies with available risk estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also included. Pooled estimates with 95% CIs were calculated using a random-effects model. Results: As of 21 May 2025, a total of 37 studies were included in the analysis. GERD was significantly associated with an increased risk of several extraesophageal malignancies, including pharyngeal cancer (pooled RR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.38–3.02), with a particularly high risk observed for hypopharyngeal cancer (RR = 2.95; 95% CI: 1.99–4.37; I2 = 60.24%). Elevated risks were also identified for laryngeal cancer (RR = 2.23; 95% CI: 1.41–3.52) and lung cancer (RR = 1.20; 95% CI: 1.01–1.42). No significant association was found between GERD and colorectal cancer (RR = 1.19; 95% CI: 0.68–2.09), and findings regarding oral cancer were inconsistent across studies. Six MR studies confirmed a positive causal relationship between GERD and lung cancer, while one MR study suggested a potential causal association with oral cancer and another with pancreatic cancer. Conclusions: Our findings suggest that GERD may be a significant risk factor for pharyngeal, laryngeal and lung cancers. Appropriate evaluation and surveillance in patients with GERD may be warranted.

1. Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common chronic gastrointestinal disorders, affecting nearly 783.95 million individuals worldwide [1]. It is characterized by esophageal mucosal damage or troublesome symptoms caused by the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus [2,3,4], leading not only to impaired quality of life but also to substantial long-term health consequences [5]. The carcinogenic potential of chronic reflux has been well established in the esophagus, where GERD represents a principal risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus and subsequently esophageal adenocarcinoma [6,7]. However, whether GERD contributes to malignant transformation beyond the esophagus remains less clear.

In recent years, increasing attention has been directed toward possible links between GERD and extraesophageal malignancies [8,9,10]. Several observational studies have suggested elevated risks of cancers of the larynx [11,12], pharynx [9,10,13], oral cavity [14], and lung [15] among individuals with GERD, raising concerns about the systemic or upper aerodigestive carcinogenic effects of chronic reflux exposure. Despite these indications, findings across studies have been inconsistent, with substantial heterogeneity in study design, diagnostic definitions of GERD, and adjustment for confounders such as smoking and alcohol drinking. As a result, the magnitude, robustness, and clinical relevance of these associations remain uncertain.

Therapeutic management of GERD includes lifestyle modification, pharmacologic therapy—primarily proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)—and surgical interventions such as laparoscopic fundoplication [5]. These treatments effectively reduce esophageal acid exposure and alleviate symptoms, and long-term PPI therapy has been suggested to mitigate progression to Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma [16]. However, whether GERD treatment reduces the incidence of extraesophageal malignancies remains unknown. Existing evidence is limited. Therefore, determining whether GERD is associated with an increased risk of extraesophageal cancers is critical for understanding its broader clinical consequences.

To date, no comprehensive synthesis has systematically evaluated this potential relationship across all reported cancer sites. Clarifying whether GERD is associated with increased risks of extraesophageal malignancies is essential for understanding the broader implications of reflux disease, identifying high-risk populations, and informing future surveillance or prevention strategies.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the association between GERD and the risk of extraesophageal malignancies and to further explore the potential cause-and-effect relationship between GERD and these cancers, thereby providing more robust evidence regarding the long-term impact of GERD.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17]. The protocol for this study was registered in PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42024504172).

2.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted in the PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases. The search was conducted on 21 May 2025. Search terms such as “gastroesophageal reflux”, “GERD”, “non-erosive reflux disease”, “NERD”, “erosive esophagitis”, “neoplasm”, “cancer”, and “malignancy” were used across all databases. The full search strategy is provided in the Supplemental Material. Additionally, studies referenced in the reference lists of the identified sources were also screened.

2.2. Study Outcomes and Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis focused on two outcomes: (1) to examine the observational association between GERD and the risk of developing extraesophageal malignancies, and (2) to evaluate the potential causal relationship between GERD and extraesophageal malignancies through meta-analyses of Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses.

Titles and abstracts of all identified records were independently screened by two investigators. Full-text was reviewed for relevance, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third investigator. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Studies reporting risk estimates (odds ratios [ORs], hazard ratios [HRs], risk ratios [RRs], or standardized incidence ratios [SIRs]) assessing the association between GERD and extraesophageal malignancies, or from which such estimates could be derived. All included cancer diagnoses were required to be confirmed by a gold-standard method, such as biopsy, or identified through medical records. GERD was diagnosed based on 24 h pH monitoring, endoscopy, clinical diagnosis, symptom-based questionnaires, or medical records. (2) MR studies that investigated the causal relationship between GERD and extraesophageal malignancies, with available risk estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Case reports, reviews, letters, editorial comments, studies without available full text, and those unrelated to the research topic were excluded. In addition, studies focusing on esophageal cancer or gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, as well as those lacking data on individual cancer types, were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Information was extracted independently by two investigators, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third investigator. For the first outcome, the following data were extracted: first author, year of publication, country, study design, participant characteristics (e.g., age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption), cancer subtype, the number of GERD cases and total sample size, and the definitions used for GERD and cancer. The number of cases and controls, risk estimates (OR, RR, HR, or SIR) with 95% CIs, and covariate adjustments were also collected. When multiple results were reported, the most fully adjusted estimates were used. Additional details, such as data sources, number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and effect estimates with 95% CI, were extracted for the second outcome. The quality of studies included for the first outcome was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [18], with studies receiving ≥7 stars considered high quality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The first outcome was assessed using pooled RRs with corresponding 95% CI for cohort studies, and pooled ORs with corresponding 95% CI for case–control and cross-sectional studies. All estimates were combined using a random-effects model. Studies reporting HRs and SIRs were converted into RRs because the incidence of cancer in the general population is low, following the methods described by Siristatidis and Qiao [19,20]. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I2 statistic, with values of <25%, 25–49%, 50–74%, and ≥75% interpreted as no, low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [21]. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on cancer subsite, gender, age, definition of GERD and adjustments when available. Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the results when five or more studies were included. For outcomes with sufficient number of studies (n > 10), we further performed meta-regression analyses. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Egger’s test (if the number of included studies ≥ 10).

For the second outcome, IVW MR estimates were pooled for the primary analysis. Sensitivity analyses were performed using the weighted median and MR-Egger methods, following the approach described by Zamani [22]. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.4.3), and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Study Characteristics

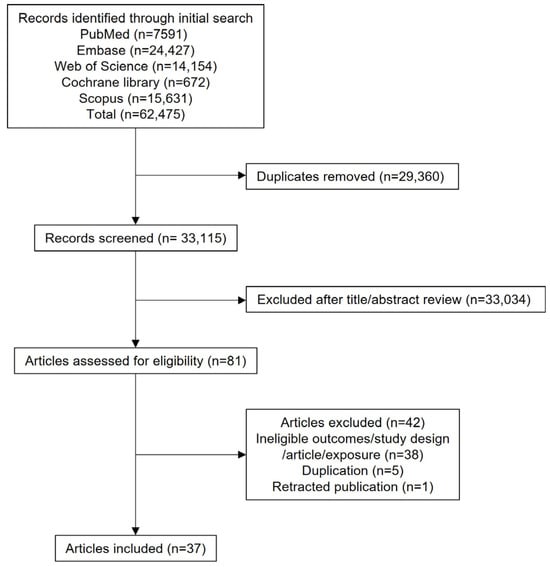

The search strategy identified 62,475 records on 21 May 2025, of which 29,360 were excluded due to duplication. After screening titles and abstracts, 33,035 records were excluded. After full-text screening, a total of 37 studies were included in the final meta-analysis [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. A detailed list of excluded studies along with reasons for exclusion is provided in in Supplemental Material, Table S1.

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1 and Supplemental Material (Tables S2 and S3). Among the included studies, 29 were observational and 8 were MR studies. A flow diagram outlining the study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included observational studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Association Between GERD and Non-Esophageal Cancer

3.2.1. Pharyngeal Cancer

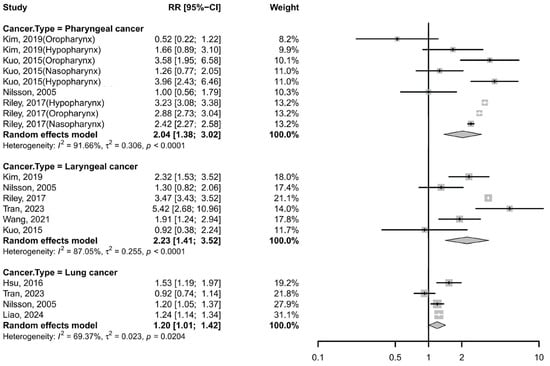

Nine studies (six cohort studies and three case–cohort studies) evaluated the association between GERD and pharyngeal cancer using risk estimates including RR, HR, SIR [8,9,10,13,14]. The pooled analysis yielded a RR of 2.04 (95% CI: 1.38–3.02; I2 = 91.66%; Figure 2), suggesting a significant positive association between GERD and pharyngeal cancer. Subgroup analysis by anatomical subsite revealed varying effects: the RR was 1.84 (95% CI: 0.59–5.72; I2 = 87.46%) for oropharyngeal cancer, 2.95 (95% CI: 1.99–4.37; I2 = 60.24%) for hypopharyngeal cancer, and 1.83 (95% CI: 0.97–3.45; I2 = 85.2%) for nasopharyngeal cancer. Despite stratification, high heterogeneity persisted across subgroups (Table S4). Sensitivity analyses confirmed that no single study substantially influenced the overall effect estimate.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the risk of non-esophageal cancer among subjects with GERD cancer. CI, confidence interval; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease [8,9,10,13,15,32,34,46].

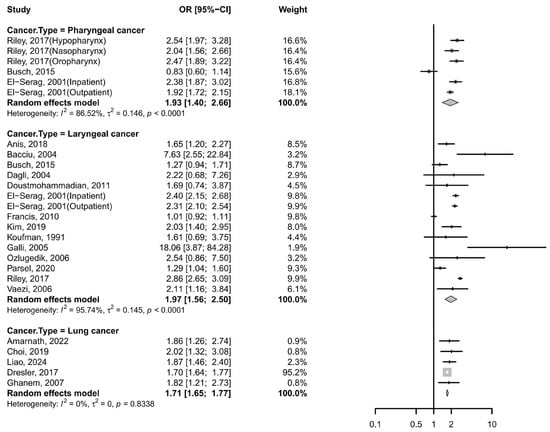

Six case–control studies also supported this association between GERD and pharyngeal cancer [13,14,27,47], with a pooled OR of 1.93 (95% CI: 1.40–2.66; I2 = 86.52%, Figure 3). However, no significant associations were observed in subgroup analyses by cancer subtype: the pooled OR was 1.45 (95% CI: 0.44–4.84) for hypopharyngeal cancer and 1.45 (95% CI: 0.50–4.16) for oropharyngeal cancer. Despite stratification, high heterogeneity persisted across subgroups (Supplementary Table S4). Notably, sensitivity analysis indicated that omission of the study by Busch et al. [14] reduced heterogeneity substantially (I2 = 43.8%) and increased the pooled OR to 2.19 (95% CI: 1.93–2.50) (Table S5).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the risk of GERD among subjects with non-esophageal cancer. CI, confidence interval; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease [8,11,12,13,14,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,39,46,48,50].

3.2.2. Laryngeal Cancer

Five cohort studies and one case–cohort study reported RRs, HRs, or SIRs [8,9,10,13,32,34], with a pooled RR of 2.23 (95% CI: 1.41–3.52; I2 = 87.05%; Figure 2), indicating a significantly increased risk of laryngeal cancer among GERD patients. Subgroup analyses showed that the heterogeneity remained substantial across different stratifications (Supplementary Material Table S6). Sensitivity analyses confirmed that no single study substantially changed the overall effect estimate.

Additionally, fourteen case–control studies and one cross-sectional study consistently supported this association, with a pooled OR of 1.97 (95% CI: 1.56–2.50; I2 = 95.74%; Figure 3) [8,11,12,13,14,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,33]. The funnel plot appeared symmetrical (Figure S1), and Egger’s test indicated no significant publication bias (p = 0.8344). Despite stratification, high heterogeneity persisted across subgroups (Supplementary Table S6). Sensitivity analyses further confirmed the robustness of the findings, as no individual study substantially altered the pooled association. Meta-regression analyses indicated that sex, region, GERD diagnostic criteria, the number of participants and adjustments for smoking/drinking were significant contributors to the observed heterogeneity for laryngeal cancer (p < 0.05), whereas age showed less pronounced effects (Supplementary Table S7).

3.2.3. Lung Cancer

Four cohort studies reported a pooled RR of 1.20 (95% CI: 1.01–1.42; I2 = 69.37%; Figure 2) [10,15,32,46], suggesting a modest but significant association. Notably, one of these studies, conducted by Liao et al. [46], identified positive associations between GERD and multiple subtypes—small cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma. Removing Tran et al.’s study [32] reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 29.3%) and strengthened the association (RR 1.24, 95% CI: 1.17–1.33) (Table S5).

Five case–control studies reported a pooled OR of 1.71 (95% CI: 1.65–1.77; I2 = 0%; Figure 3) [24,39,46,48,50], indicating a significant association with no observed heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses confirmed consistent results across all studies.

3.2.4. Other Cancers

For colorectal cancer, three cohort studies reported no statistically significant association with GERD (pooled RR = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.68–2.09). Similarly, three studies investigating gastric (excluding gastric cardia) cancer showed a non-significant pooled estimate (RR: 1.57, 95% CI: 0.75–3.29) [45,49,51].

Findings for oral cancer were inconsistent across studies. Two cohort studies reported conflicting estimates (RR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.43–1.31; vs. SIR = 1.33, 95% CI: 0.94–1.83) [8,9,32], and one case–control study conducted by Busch et al. reported an OR of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.46–1.02) [14], though all the result was not statistically significant.

Regarding other cancer types, Tran et al. found inverse associations between GERD and cancers of the liver and pancreatic cancers, but a positive association with thyroid cancer [32]. In another study, Riley reported a positive relationship between GERD and cancers of the tonsil and paranasal sinus [13]. However, these results are derived from single studies, limiting the ability to draw firm conclusions.

3.3. Cause-and-Effect Relationship Between GERD and Non-Esophageal Cancer

3.3.1. Lung Cancer

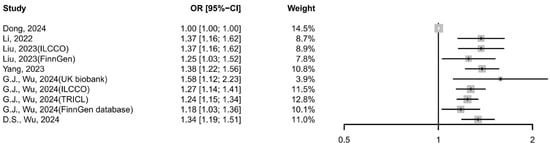

Six MR studies [35,36,37,38,41,42] were included to assess the potential causal relationship between GERD and lung cancer. The meta-analysis using the IVW method revealed that a significant positive association (OR: 1.26 [95% CI:1.16–1.36], I2 = 93.55%, p <0.0001; Figure 4), with GERD increasing the risk of lung cancer, which was supported by the weighted median (1.00 [95% CI 1.00–1.01], I2 = 0%, p = 0.5280) and MR-Egger analyses (1.19 [95% CI 1.09–1.29], I2 = 82.52%, p < 0.0001). Leave-one-out analysis revealed that the study by Dong et al. [41] was a major source of heterogeneity; its exclusion reduced the I2 from 93.59% to 0%, likely due to its weak reported association (OR = 1.0027), narrow confidence interval, and disproportionate weight.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the cause-and-effect relationship between GERD and lung cancer using IVW methods. CI, confidence interval; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease [35,36,37,38,41,42].

Subgroup analyses confirmed the causal relationship between GERD and all subtypes of lung cancer. The meta-IVW estimates showed a consistent positive association: 1.27 (95% CI: 1.16–1.38) for squamous cell carcinoma, 1.21 (95% CI: 1.12–1.30) for adenocarcinoma, and 1.87 (95% CI: 1.47–2.31) for small cell carcinoma. These findings were further supported by sensitivity analyses, with low heterogeneity observed across all subtypes (I2 = 0%).

3.3.2. Other Cancers

One MR study conducted by Shen et al. reported a positive association between GERD and oral cavity cancer, with an IVW estimate of 1.90 (95% CI: 1.26–2.81) [40]. This finding was consistent with results from the weighted median (OR: 1.60 [95% CI: 0.70–3.70]) and MR-Egger methods (OR: 27.27 [95% CI: 0.31–290.04]).

In addition, one MR study reported a potential causal relationship between GERD and pancreatic cancer, with an IVW OR of 1.36 (95% CI: 1.04–1.80) [43]. The weighted median (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 0.86–1.91) and MR-Egger (OR: 1.83, 95% CI: 0.37–9.09) results were consistent in direction, though not statistically significant.

4. Discussion

GERD is a chronic condition that necessitates long-term management. Current screening guidelines recognize chronic GERD as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma [52,53,54] and recommend appropriate clinical evaluation and surveillance for patients with additional risk factors, such as male sex or age ≥50 years. However, GERD is not currently considered a risk factor for extraesophageal malignancies. Our findings underscore the urgent need for increased clinical and public health attention to GERD in the context of extraesophageal cancer burden. Our meta-analysis revealed that GERD was significantly associated with an elevated risk of cancers of the pharynx, larynx, and lung, while no significant associations were found between GERD and either colorectal or gastric cancer.

The core pathophysiological feature of GERD is the retrograde movement of acidic and non-acidic gastric contents into the esophagus. When aspirated into adjacent or distant tissues, these refluxates—containing acid, pepsin, bile acids, and trypsin—may induce chronic mucosal injury. Biologically, this process is believed to contribute to carcinogenesis through mechanisms such as chronic inflammation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and angiogenesis [55,56]. This was supported by a prospective case–control study, in which a higher risk of laryngeal cancer was observed among patients who had undergone gastrectomy, suggesting a potential role of duodenal content (including bile acids and trypsin), pepsin, and acid residues on the development of laryngeal malignancies [57]. Moreover, the presence of pepsin in the airways of GERD patients at significantly higher levels than in controls was confirmed, further supporting the role of aspiration in carcinogenesis [58].

The pharynx—particularly the oropharynx—and larynx are anatomically adjacent to the esophagus and directly exposed to gastric refluxate, making them susceptible to injury from acid, pepsin, and bile acids. Chronic exposure of the upper aerodigestive tract to refluxate can induce epithelial inflammation, oxidative stress, and microerosion, predisposing mucosal tissue to malignant transformation. These biological processes may partially explain the elevated risks identified in our synthesis. Also, this anatomical proximity, together with the feasibility of endoscopic surveillance, highlights the clinical relevance of assessing cancer risk in these regions. Our meta-analysis revealed a significant association between GERD and laryngeal cancers, consistent with previous findings [31,59,60]. Although tobacco and alcohol use are established confounders [61,62], subgroup analyses adjusting for these factors showed only slightly attenuated effect estimates without statistical significance. Moreover, several studies demonstrated positive associations even among nonsmokers and nondrinkers, further supporting GERD as a potential independent risk factor for malignancies in the upper digestive tract [23,63].

Lung cancer is the most prevalent cancer worldwide. While previous studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the association between GERD and lung cancer [32,39], our meta-analysis supports a positive association. Given that tobacco smoking is a major confounder, the included studies had adjusted for or excluded smoking as a variable, and the pooled OR estimates still demonstrated a positive association. MR analyses also support a causal relationship, with all IVW estimates demonstrating significant associations independent of smoking status. These findings are reinforced by a population-based cohort study, which found that anti-reflux surgery was associated with a reduced risk of small-cell and squamous-cell lung cancers [64].

Compared with previous meta-analyses exploring the relationship between GERD and laryngeal or pharyngeal cancer [59,65]—which included only case–control or cross-sectional studies and confirmed associations without addressing causality—our study incorporated cohort studies, thereby providing more robust evidence with long-term follow-up. This methodological improvement strengthens the reliability of the observed associations. Furthermore, to minimize publication bias and ensure comprehensive data inclusion, we also included eligible conference abstracts. Importantly, our integration of MR studies allowed us to assess potential causal relationships between GERD and non-esophageal cancers, offering insights beyond those achievable through traditional observational designs. To our knowledge, this is the most up-to-date and comprehensive synthesis of evidence on this topic.

Notably, there is no established guideline recommending surveillance solely because of GERD for most extraesophageal cancers. Routine cancer screening solely on the basis of GERD symptoms is not supported by the current evidence. Instead, a targeted, risk-stratified approach is more appropriate. Clinicians should consider intensified evaluation or referral for patients with GERD who present additional high-risk factors, such as older age, heavy smoking history, obesity, or a family history of relevant malignancy. For these patients, a lower threshold for diagnostic work-up and counseling on modifiable risk factors (smoking cessation, alcohol reduction, weight management) is reasonable. Also, while standard therapeutic protocols such as PPIs and lifestyle interventions effectively reduce esophageal inflammation and symptoms, evidence regarding their ability to lower the incidence of extraesophageal cancers is limited. Future studies should explore whether early intervention in GERD patients can modify cancer risk and identify subgroups who may benefit most from targeted prevention strategies.

One strength of our analysis is the incorporation of MR evidence, which helps mitigate key biases inherent to observational studies, such as confounding and reverse causation [66]. However, MR studies also have important limitations that must be acknowledged. Their validity depends heavily on the selection of robust genetic instruments. Although we ensured instrument strength by including variants with F-statistics >10, MR analyses may still be affected by horizontal pleiotropy, population stratification, and violations of the core instrumental variable assumptions. Moreover, the genetic architecture of GERD may differ across populations, potentially contributing to the observed heterogeneity among MR estimates.

This study has several limitations. First, the exclusion of studies that defined GERD based solely on symptoms may have led to an underestimation of the true associations, as some cases of GERD might have been missed. Second, substantial heterogeneity was observed in several analyses, which could not be fully accounted for through subgroup or sensitivity analyses, and may reflect differences in study populations, diagnostic criteria for GERD, and study designs. Lastly, for cancer types such as oral, thyroid, colorectal, gastric, and pancreatic cancers, the available evidence is limited and sometimes inconsistent. Therefore, while our meta-analysis did not identify statistically significant associations for these cancers, this should be interpreted cautiously, as the small number of studies prevents definitive conclusions. These limitations underscore the need for future high-quality, large-scale studies with standardized definitions of GERD and cancer outcomes to more accurately elucidate the relationship between GERD and non-esophageal cancers.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the association between GERD and extraesophageal cancers. We found evidence of a positive association between GERD and certain malignancies, including pharyngeal, laryngeal, and lung cancer. Meta-analyses of MR studies suggested a potential causal link with lung cancer. However, for other cancer types, the evidence remains limited and inconclusive. These findings highlight the need for further high-quality studies before making definitive public health recommendations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers17233881/s1, Table S1. Table of excluded studies with rationale; Table S2. Baseline characteristics of the Mendelian randomization studies assessing the relationship of GERD and cancer; Table S3. Baseline characteristics of the Mendelian randomization studies assessing the relationship of GERD and lung cancer on specific subtype; Table S4. Subgroup analysis results assessing the relationship of GERD and pharyngeal cancer; Table S5. Leave-one-out meta-analysis results; Table S6. Subgroup analysis results assessing the relationship of GERD and laryngeal cancer; Table S7. Meta-regression results; Figure S1. Funnel plot to assess publication bias across the studies evaluating the risk of GERD among subjects with laryngeal cancer.

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conceptualization: Y.-S.X. and Y.G.; Data curation, Methodology, Investigation and Formal analysis: Y.-S.X., Z.-R.C. and Y.B.; Writing—original draft: Y.-S.X.; Writing—review and editing: L.X.; Project administration: Y.G., L.X. and L.-W.W.; Supervision: L.X. and L.-W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (number 82370677), and the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Fund under Grant (number 202240357). The funding sources of this study had no role in the study, including study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its Supplemental Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| RR | Risk Ratio |

| OR | Odds Ratios |

| HR | Hazard Ratios |

| MR | Mendelian Randomization |

| CI | Confidence Intervals |

| SIR | Standardized Incidence Ratio |

References

- Zhang, D.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, R. Global, Regional and National Burden of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, 1990–2019: Update from the Gbd 2019 Study. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 1372–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyawali, C.P.; Yadlapati, R.; Fass, R.; Katzka, D.; Pandolfino, J.; Savarino, E.; Sifrim, D.; Spechler, S.; Zerbib, F.; Fox, M.R.; et al. Updates to the Modern Diagnosis of Gerd: Lyon Consensus 2.0. Gut 2024, 73, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakil, N.; van Zanten, S.V.; Kahrilas, P.; Dent, J.; Jones, R. The Montreal Definition and Classification of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Global Evidence-Based Consensus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 1900–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar, K.B. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, ITC113–ITC128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, P.O.; Dunbar, K.B.; Schnoll-Sussman, F.H.; Greer, K.B.; Yadlapati, R.; Spechler, S.J. Acg Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroush, A.; Malekzadeh, R.; Roshandel, G.; Khoshnia, M.; Poustchi, H.; Kamangar, F.; Brennan, P.; Boffetta, P.; Dawsey, S.M.; Abnet, C.C.; et al. Sex and Smoking Differences in the Association between Gastroesophageal Reflux and Risk of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a High-Incidence Area: Golestan Cohort Study. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgomo, M.; Mokoena, T.R.; Ker, J.A. Non-Acid Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Is Associated with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oesophagus. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017, 4, e000180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, B.; Lim, H.; Kim, M.; Kong, I.G.; Choi, H.G. Increased Risk of Larynx Cancer in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease from a National Sample Cohort. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2019, 44, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-L.; Chen, Y.-T.; Shiao, A.-S.; Lien, C.-F.; Wang, S.-J. Acid Reflux and Head and Neck Cancer Risk: A Nationwide Registry over 13 Years. Auris Nasus Larynx 2015, 42, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Chow, W.H.; Lindblad, M.; Ye, W. No Association between Gastroesophageal Reflux and Cancers of the Larynx and Pharynx. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 1194–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, M.M.; Razavi, M.-M.; Xiao, X.; Soliman, A.M.S. Association of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Laryngeal Cancer. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 4, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, D.O.; Maynard, C.; Weymuller, E.A.; Reiber, G.; Merati, A.L.; Yueh, B. Reevaluation of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease as a Risk Factor for Laryngeal Cancer. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, C.A.; Wu, E.L.; Hsieh, M.-C.; Marino, M.J.; Wu, X.-C.; McCoul, E.D. Association of Gastroesophageal Reflux with Malignancy of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract in Elderly Patients. Jama Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 144, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, E.L.; Zevallos, J.P.; Olshan, A.F. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Odds of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in North Carolina. Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.K.; Lai, C.C.; Wang, K.; Chen, L. Risk of Lung Cancer in Patients with Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, E.J.; Kaz, A.M.; Inadomi, J.M.; Grady, W.M. Chemoprevention of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 8, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The Prisma 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Bmj 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Nos) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Huang, Q.; Zhao, M.J.; Luo, L.S.; Deng, T.; Zeng, X.; Wang, X. Discrimination and Conversion between Hazard Ratio and Risk Ratio as Effect Measures in Prospective Studies. Chin. J. Evid. Based Med. 2020, 20, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Siristatidis, C.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Kanavidis, P.; Trivella, M.; Sotiraki, M.; Mavromatis, I.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Skalkidou, A.; Petridou, E.T. Controlled Ovarian Hyperstimulation for Ivf: Impact on Ovarian, Endometrial and Cervical Cancer—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. Bmj 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Alizadeh-Tabari, S.; Chan, W.W.; Talley, N.J. Association between Anxiety/Depression and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 2133–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacciu, A.; Mercante, G.; Ingegnoli, A.; Ferri, T.; Muzzetto, P.; Leandro, G.; Di Mario, F.; Bacciu, S. Effects of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Laryngeal Carcinoma. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 2004, 29, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.I.; Jeong, J.; Lee, C.W. Association between Egfr Mutation and Ageing, History of Pneumonia and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease among Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 122, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dağli, S.; Dağli, U.; Kurtaran, H.; Alkim, C.; Sahin, B. Laryngopharyngeal Reflux in Laryngeal Cancer. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 15, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Doustmohammadian, N.; Naderpour, M.; Khoshbaten, M.; Doustmohammadian, A. Is There Any Association between Esophagogastric Endoscopic Findings and Laryngeal Cancer? Am. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Med. Surg. 2011, 32, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Hepworth, E.J.; Lee, P.; Sonnenberg, A. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Is a Risk Factor for Laryngeal and Pharyngeal Cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, J.; Cammarota, G.; Calò, L.; Agostino, S.; D’Ugo, D.; Cianci, R.; Almadori, G. The Role of Acid and Alkaline Reflux in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 1861–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufman, J.A. The Otolaryngologic Manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (Gerd): A Clinical Investigation of 225 Patients Using Ambulatory 24-Hour Ph Monitoring and an Experimental Investigation of the Role of Acid and Pepsin in the Development of Laryngeal Injury. Laryngoscope 1991, 101 Pt 2 (Suppl. S53), 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ozlugedik, S.; Yorulmaz, I.; Gokcan, K. Is Laryngopharyngeal Reflux an Important Risk Factor in the Development of Laryngeal Carcinoma? Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 263, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsel, S.M.; Iarocci, A.L.; Gastañaduy, M.; Winters, R.D.; Marino, J.P.; McCoul, E.D. Reflux Disease and Laryngeal Neoplasia in Nonsmokers and Nondrinkers. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 163, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.L.; Han, M.; Kim, B.; Park, E.Y.; Kim, Y.I.; Oh, J.-K. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Risk of Cancer: Findings from the Korean National Health Screening Cohort. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 19163–19173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaezi, M.F.; Qadeer, M.A.; Lopez, R.; Colabianchi, N. Laryngeal Cancer and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Case-Control Study. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.M.; Freedman, N.D.; Katki, H.A.; Matthews, C.; Graubard, B.I.; Kahle, L.L.; Abnet, C.C. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Risk Factor for Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in the Nih-Aarp Diet and Health Study Cohort. Cancer 2021, 127, 1871–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, H. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and the Risk of Respiratory Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ren, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Bai, Y.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, H. Causal Associations between Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Lung Cancer Risk: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 7552–7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lai, H.; Zhang, R.; Xia, L.; Liu, L. Causal Relationship between Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease and Risk of Lung Cancer: Insights from Multivariable Mendelian Randomization and Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 52, 1435–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Nie, D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Gong, C.; Liu, Q. The Role of Smoking and Alcohol in Mediating the Effect of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease on Lung Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1054132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnath, S.; Starr, A.; Chukkalore, D.; Elfiky, A.; Abureesh, M.; Aqsa, A.; Singh, C.; Weerasinghe, C.; Gurala, D.; Demissie, S.; et al. The Association between Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Gastroenterol. Res. 2022, 15, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, C.; Cao, C.; Wang, G.; Li, Z. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease as a Risk Factor for Oral Cavity and Pharyngeal Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhou, J.; Song, L.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, T.; Ren, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, L. A Multi-Level Investigation of the Genetic Relationship between Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Lung Cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2024, 13, 2373–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Ning, D.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Chang, L.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L.; Huang, Y. Unraveling the Causality between Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Increased Cancer Risk: Evidence from the Uk Biobank and Gwas Consortia. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Ge, F.; Peng, M.; Cheng, L.; Wang, K.; Liu, W. Exploring the Genetic Link between Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Pancreatic Cancer: Insights from Mendelian Randomization. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.H.; Tseng, C.C.; Bernstein, L. Hiatal Hernia, Reflux Symptoms, Body Size, and Risk of Esophageal and Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2003, 98, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solaymani-Dodaran, M.; Logan, R.F.; West, J.; Card, T.; Coupland, C. Risk of Extra-Oesophageal Malignancies and Colorectal Cancer in Barrett’s Oesophagus and Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 39, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Liao, J.; Long, L. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Risk of Incident Lung Cancer: A Large Prospective Cohort Study in Uk Biobank. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán De Alba, L.M.; Castro, F.M.R. Risk Factors for Developing Laryngeal Cancer in Adult Population at the Hospital Español in Mexico City. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp. 2008, 59, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, Z.; Sedfawy, A.; Debari, V.; Maroules, M. An Association between Lung Cancer and Gastroesophageal Reflux. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 18195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayasaka, J.; Hoteya, S.; Takazawa, Y.; Kikuchi, D.; Araki, A. Antacids and Reflux Esophagitis as a Risk Factor for Gastric Neoplasm of Fundic-Gland Type: A Retrospective, Matched Case–Control Study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1580–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresler, H.; Keizman, D.; Mamtani, R.; Gottfried, M.; Maimon, N.; Mishaeli, M.; Haynes, K.; Yang, Y.X.; Boursi, B. The Association between Proton Pump Inhibitors (Ppi) Use for Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease (Gerd) and Lung Cancer (Lc): A Nested Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.M.; Wu, J.J.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Tian, Y.F.; Chang, P.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Chou, Y.C.; Sun, C.A. Association between Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Desai, M.; Ruan, W.; Thosani, N.C.; Amaris, M.; Scott, J.S.; Saeed, A.; Abu Dayyeh, B.; Canto, M.I.; Abidi, W.; et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Gerd: Summary and Recommendations. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2025, 101, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weusten, B.; Bisschops, R.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; di Pietro, M.; Pech, O.; Spaander, M.C.W.; Baldaque-Silva, F.; Barret, M.; Coron, E.; Fernandez-Esparrach, G.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett Esophagus: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (Esge) Guideline. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 1124–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groulx, S.; Limburg, H.; Doull, M.; Klarenbach, S.; Singh, H.; Wilson, B.J.; Thombs, B.; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Guideline on Screening for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in Patients with Chronic Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. CMAJ 2020, 192, E768–E777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X. Research Progress on Gastroesophageal Reffux Disease Associated Lung Injury and Lung Cancer. Chin. J. Pract. Intern. Med. 2018, 38, 961–963. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, T.L.; Nassar, M.; Soubani, A.O. Pulmonary Manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 14, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarota, G.; Galli, J.; Cianci, R.; De Corso, E.; Pasceri, V.; Palli, D.; Masala, G.; Buffon, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Almadori, G.; et al. Association of Laryngeal Cancer with Previous Gastric Resection. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisichella, P.M.; Davis, C.S.; Lundberg, P.W.; Lowery, E.; Burnham, E.L.; Alex, C.G.; Ramirez, L.; Pelletiere, K.; Love, R.B.; Kuo, P.C.; et al. The Protective Role of Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery against Aspiration of Pepsin after Lung Transplantation. Surgery 2011, 150, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, J.; Chen, B.; Zhou, L.; Tao, L. Gastroesophageal Reflux and Carcinoma of Larynx or Pharynx: A Meta-Analysis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014, 134, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eells, A.C.; Mackintosh, C.; Marks, L.; Marino, M.J. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Head and Neck Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Med. Surg. 2020, 41, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, M.A.; Colabianchi, N.; Strome, M.; Vaezi, M.F. Gastroesophageal Reflux and Laryngeal Cancer: Causation or Association? A Critical Review. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2006, 27, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, J.; Malvezzi, M.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C.; Boffetta, P. Risk Factors for Lung Cancer Worldwide. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacciu, A.; Mercante, G.; Ingegnoli, A.; Bacciu, S.; Ferri, T. Reflux Esophagitis as a Possible Risk Factor in the Development of Pharyngolaryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Tumori 2003, 89, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanes, M.; Santoni, G.; Maret-Ouda, J.; Ness-Jensen, E.; Farkkila, M.; Lynge, E.; Pukkala, E.; Romundstad, P.; Tryggvadottir, L.; von Euler-Chelpin, M.; et al. Laryngeal and Pharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Antireflux Surgery in the 5 Nordic Countries. Ann. Surg. 2022, 276, E79–E85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsel, S.M.; Wu, E.L.; Riley, C.A.; McCoul, E.D. Gastroesophageal and Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Associated with Laryngeal Malignancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1253–1264.e1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Burgess, S. Appraising the Causal Role of Smoking in Multiple Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mendelian Randomization Studies. eBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).