The Involvement of the Peptidergic Systems in Breast Cancer Development

Simple Summary

Abstract

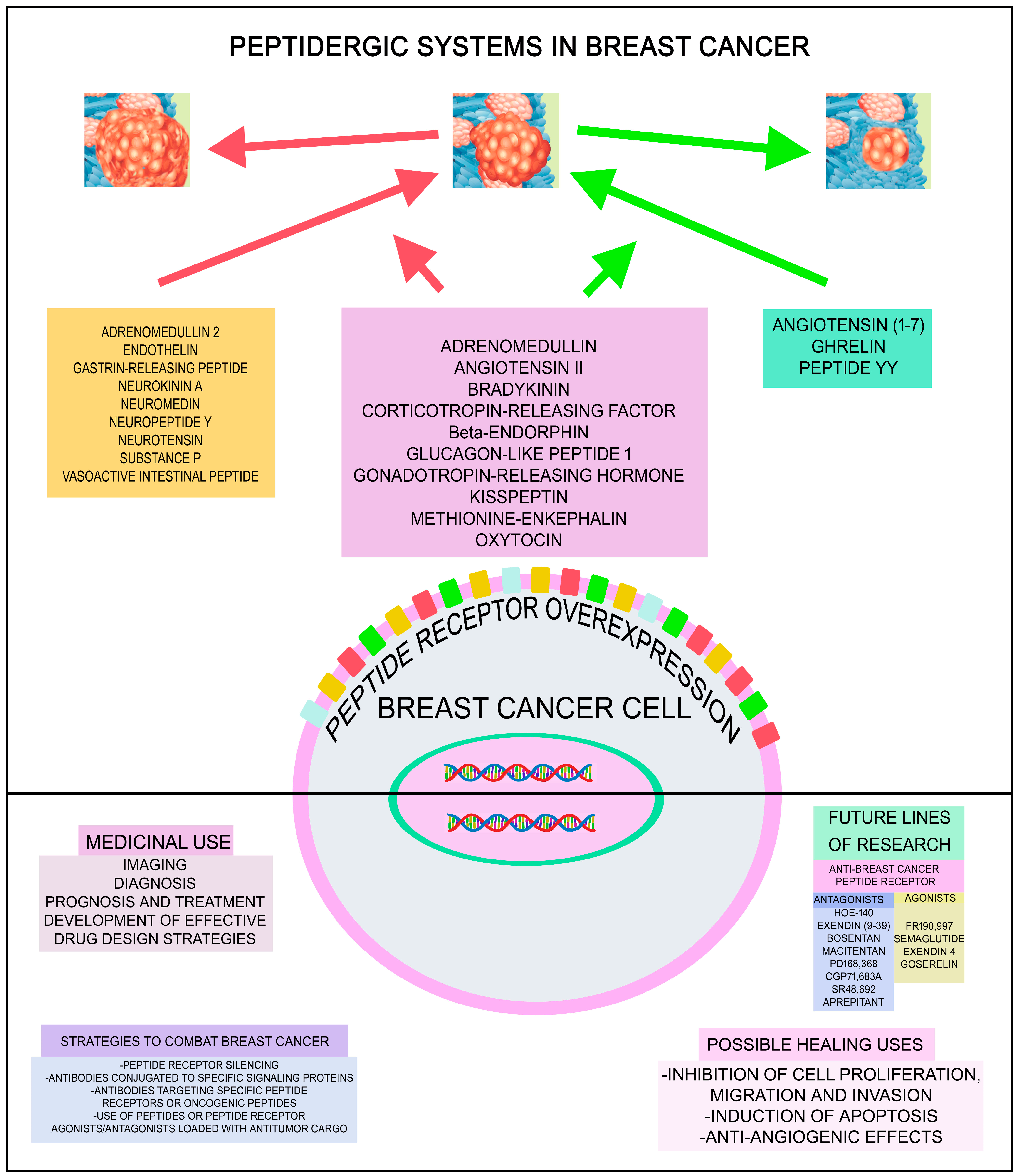

1. Introduction

2. Breast Cancer and Peptidergic Systems

2.1. Oncogenic and Anticancer Peptides

2.1.1. Adrenomedullin

2.1.2. Angiotensin II

2.1.3. Bradykinin

2.1.4. Corticotropin-Releasing Factor

2.1.5. Endorphins

2.1.6. Enkephalins

2.1.7. Glucagon-like Peptide 1

2.1.8. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone/Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone

2.1.9. Kisspeptin

2.1.10. Oxytocin

2.2. Oncogenic Peptides

2.2.1. Adrenomedullin 2

2.2.2. Endothelin

2.2.3. Gastrin-Releasing Peptide

2.2.4. Neurokinin A

2.2.5. Neuromedin

2.2.6. Neuropeptide Y

2.2.7. Neurotensin

2.2.8. Substance P

2.2.9. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide

2.3. Anticancer Peptides

2.3.1. Angiotensin (1–7) Fragment

2.3.2. Ghrelin

2.3.3. Peptide YY

2.4. Other Bioactive and Non-Bioactive Peptides and Breast Cancer

2.4.1. ASRPS

2.4.2. Carnosine

2.4.3. Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript

2.4.4. Dynorphin

2.4.5. Galanin

2.4.6. HMK (HER2 Affibody-Matrix Metalloproteinase 2-Sensitive Cleavage Sequence-KLA (Kytoplasmic Lipid-Associated))

2.4.7. KLA Peptide

2.4.8. LINC00511-133aa

2.4.9. Melittin

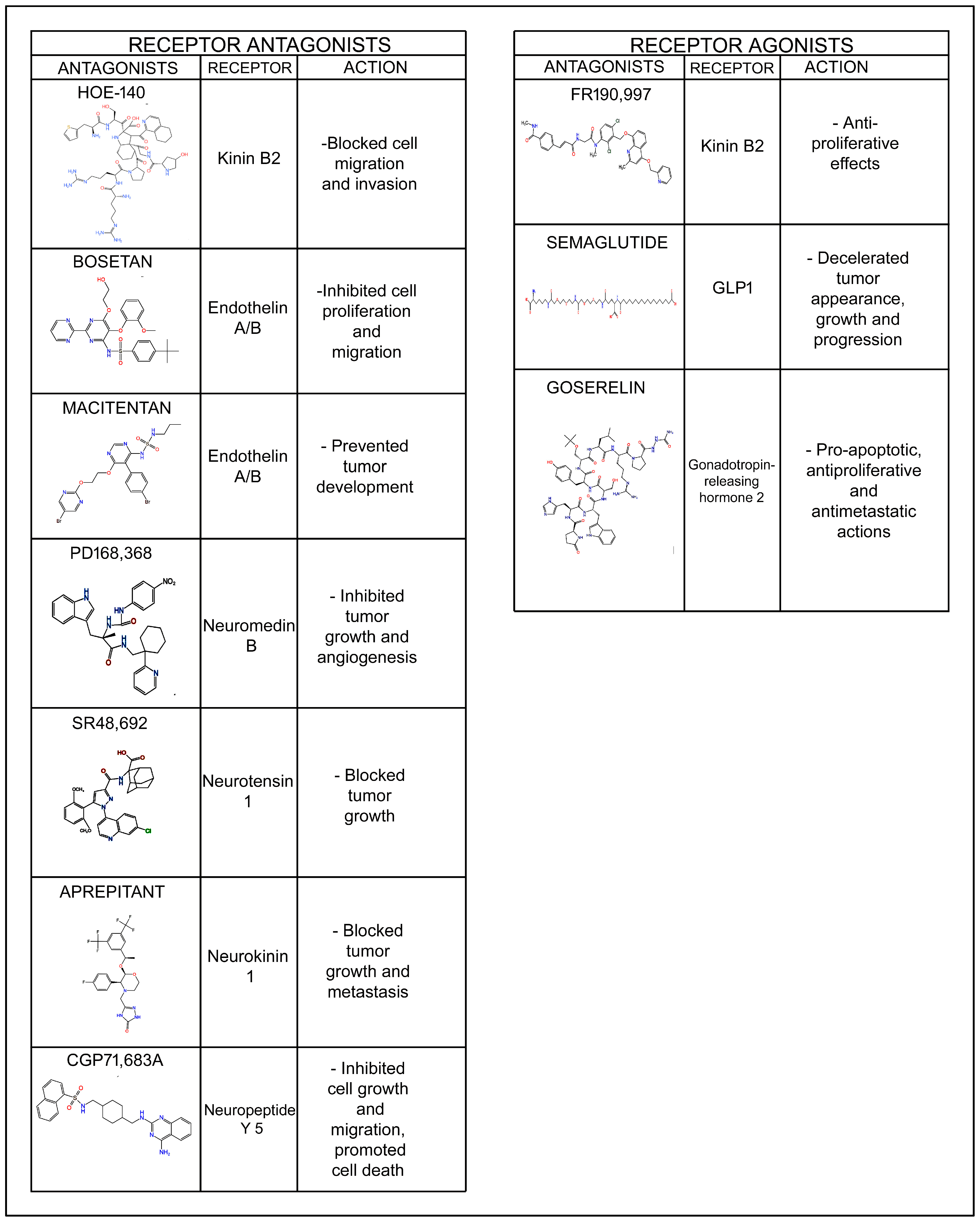

3. Perspectives and Future Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, N.; Javidan, M.; Sheikhi, S.; Taştan, Ö.; Parodi, A.; Liao, Z.; Tayybi Azar, M.; Ganjalıkhani-Hakemi, M. Bioactive Peptides: An Alternative Therapeutic Approach for Cancer Management. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1310443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.D.; Coveñas, R. Peptidergic G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling Systems in Cancer: Examination of Receptor Structure and Signaling to Foster Innovative Pharmacological Solutions. Future Pharmacol. 2024, 4, 801–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.L.; Coveñas, R. The Galaninergic System: A Target for Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2022, 14, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.L.; Rodríguez, F.D.; Coveñas, R. Involvement of the Opioid Peptide Family in Cancer Progression. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.L.; Rodríguez, F.D.; Coveñas, R. Peptidergic Systems and Cancer: Focus on Tachykinin and Calcitonin/Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Families. Cancers 2023, 15, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorica, J.; De Feo, M.S.; Filippi, L.; Frantellizzi, V.; Schillaci, O.; De Vincentis, G. Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor Agonists and Antagonists for Molecular Imaging of Breast and Prostate Cancer: From Pre-Clinical Studies to Translational Perspectives. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Lei, Z.; Chang, M.; Peng, Y. Design and Implication of a Breast Cancer-Targeted Drug Delivery System Utilizing the Kisspeptin/GPR54 System. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 670, 125154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okarvi, S.M. Preparation, Radiolabeling with 68Ga/177Lu and Preclinical Evaluation of Novel Angiotensin Peptide Analog: A New Class of Peptides for Breast Cancer Targeting. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S.; Rosso, M.; Medina, R.; Coveñas, R.; Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M. The Neurokinin-1 Receptor Is Essential for the Viability of Human Glioma Cells: A Possible Target for Treating Glioblastoma. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 6291504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Musaimi, O. Peptide Therapeutics: Unveiling the Potential against Cancer—A Journey through 1989. Cancers 2024, 16, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goserelin Drug Label. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/019726s050s051s052lbl.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Rodriguez, E.; Pei, G.; Kim, S.T.; German, A.; Robinson, P. Substance P Antagonism as a Novel Therapeutic Option to Enhance Efficacy of Cisplatin in Triple Negative Breast Cancer and Protect PC12 Cells against Cisplatin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 3871, Erratum in Cancers 2021, 13, 5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legi, A.; Rodriguez, E.; Eckols, T.K.; Mistry, C.; Robinson, P. Substance P Antagonism Prevents Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cancers 2021, 13, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larráyoz, I.M.; Martínez-Herrero, S.; García-Sanmartín, J.; Ochoa-Callejero, L.; Martínez, A. Adrenomedullin and Tumour Microenvironment. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Shi, M.; Li, Y. Adrenomedullin in Tumorigenesis and Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-L.; Chen, S.-L.; Huang, Y.-H.; Yang, X.; Wang, C.-H.; He, J.-H.; Yun, J.-P.; Luo, R.-Z. Adrenomedullin Inhibits Tumor Metastasis and Is Associated with Good Prognosis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siclari, V.A.; Mohammad, K.S.; Tompkins, D.R.; Davis, H.; McKenna, C.R.; Peng, X.; Wessner, L.L.; Niewolna, M.; Guise, T.A.; Suvannasankha, A. Tumor-Expressed Adrenomedullin Accelerates Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyahia, Z.; Dussault, N.; Cayol, M.; Sigaud, R.; Berenguer-Daizé, C.; Delfino, C.; Tounsi, A.; Garcia, S.; Martin, P.-M.; Mabrouk, K. Stromal Fibroblasts Present in Breast Carcinomas Promote Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis through Adrenomedullin Secretion. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 15744–15762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, M.; Darini, C.Y.; Yao, X.; Chignon-Sicard, B.; Rekima, S.; Lachambre, S.; Virolle, V.; Aguilar-Mahecha, A.; Basik, M.; Ladoux, A. Breast Cancer Mammospheres Secrete Adrenomedullin to Induce Lipolysis and Browning of Adjacent Adipocytes. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shibahara, S.; Takahashi, K. Adrenomedullin Is a Novel Adipokine: Adrenomedullin in Adipocytes and Adipose Tissues. Peptides 2007, 28, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunyady, L.; Catt, K.J. Pleiotropic AT1 Receptor Signaling Pathways Mediating Physiological and Pathogenic Actions of Angiotensin II. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervais, M.; Dugourd, C.; Muller, L.; Ardidie, C.; Canton, B.; Loviconi, L.; Corvol, P.; Chneiweiss, H.; Monnot, C. Akt Down-Regulates ERK1/2 Nuclear Localization and Angiotensin II-Induced Cell Proliferation through PEA-15. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 3940–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.-K.; Harris, R.C. Angiotensin II Induces Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Renal Epithelial Cells through Reactive Oxygen Species/Src/Caveolin-Mediated Activation of an Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, A.; Takagi, H.; Suzuma, K.; Honda, Y. Angiotensin II Potentiates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor–Induced Angiogenic Activity in Retinal Microcapillary Endothelial Cells. Circ. Res. 1998, 82, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddesha, J.M.; Valente, A.J.; Sakamuri, S.S.V.P.; Yoshida, T.; Gardner, J.D.; Somanna, N.; Takahashi, C.; Noda, M.; Chandrasekar, B. Angiotensin II Stimulates Cardiac Fibroblast Migration via the Differential Regulation of Matrixins and RECK. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013, 65, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghooti, H.; Firoozrai, M.; Fallah, S.; Khorramizadeh, M.R. Angiotensin II Differentially Induces Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1 Production and Disturbs MMP/TIMP Balance. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2010, 2, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Alfoudiry, M.M.; Khajah, M.A. Angiotensin 1–7 and the Non-Peptide MAS-R Agonist AVE0991 Inhibit Breast Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamro, A.A.; Almutlaq, M.A.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Alshammari, A.H.; Alshehri, E.; Abdi, S. Role of Renin–Angiotensin System and Macrophages in Breast Cancer Microenvironment. Diseases 2025, 13, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, K.; Kamata, M.; Hayashi, I.; Yamashina, S.; Majima, M. Roles of Bradykinin in Vascular Permeability and Angiogenesis in Solid Tumor. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2002, 2, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusco, I.; Fialho, M.F.P.; Becker, G.; Brum, E.S.; Favarin, A.; Marquezin, L.P.; Serafini, P.T.; Oliveira, S.M. Kinins and Their B1 and B2 Receptors as Potential Therapeutic Targets for Pain Relief. Life Sci. 2023, 314, 121302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Bertels, Z.; Del Rosario, J.S.; Widman, A.J.; Slivicki, R.A.; Payne, M.; Susser, H.M.; Copits, B.A.; Gereau, R.W. Bradykinin Receptor Expression and Bradykinin-Mediated Sensitization of Human Sensory Neurons. Pain 2024, 165, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Function and Structure of Bradykinin Receptor 2 for Drug Discovery. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.; Wu, C.; Yang, C. Bradykinin Induces Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Expression and Cell Migration through a PKC-δ-dependent ERK/Elk-1 Pathway in Astrocytes. Glia 2008, 56, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augoff, K.; Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A.; Tabola, R.; Stach, K. MMP9: A Tough Target for Targeted Therapy for Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-S.; Wang, S.-W.; Chang, A.-C.; Tai, H.-C.; Yeh, H.-I.; Lin, Y.-M.; Tang, C.-H. Bradykinin Promotes Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression and Increases Angiogenesis in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 87, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Sato, E.; Nomura, H.; Kubo, K.; Miura, M.; Yamashita, T.; Nagai, S.; Izumi, T. Bradykinin Stimulates Type II Alveolar Cells to Release Neutrophil and Monocyte Chemotactic Activity and Inflammatory Cytokines. Am. J. Pathol. 1998, 153, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Turén, F.; Lobos-González, L.; Riquelme-Herrera, A.; Ibacache, A.; Meza Ulloa, L.; Droguett, A.; Alveal, C.; Carrillo, B.; Gutiérrez, J.; Ehrenfeld, P. Kinin Receptors B1 and B2 Mediate Breast Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion by Activating the FAK-Src Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rassias, G.; Leonardi, S.; Rigopoulou, D.; Vachlioti, E.; Afratis, K.; Piperigkou, Z.; Koutsakis, C.; Karamanos, N.K.; Gavras, H.; Papaioannou, D. Potent Antiproliferative Activity of Bradykinin B2 Receptor Selective Agonist FR-190997 and Analogue Structures Thereof: A Paradox Resolved? Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuc, C.; Savard, M.; Bovenzi, V.; Lessard, A.; Côté, J.; Neugebauer, W.; Geha, S.; Chemtob, S.; Gobeil, F. Antitumor Activity of Cell-penetrant Kinin B1 Receptor Antagonists in Human Triple-negative Breast Cancer Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 2851–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfeld, P.; Manso, L.; Pavicic, M.F.; Matus, C.E.; Borquez, C.; Lizama, A.; Sarmiento, J.; Poblete, M.T.; Bhoola, K.D. Bioregulation of Kallikrein-Related Peptidases 6, 10 and 11 by the Kinin B1 Receptor in Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 6925–6938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ehrenfeld, P.; Conejeros, I.; Pavicic, M.F.; Matus, C.E.; Gonzalez, C.B.; Quest, A.F.G.; Bhoola, K.D.; Poblete, M.T.; Burgos, R.A.; Figueroa, C.D. Activation of Kinin B1 Receptor Increases the Release of Metalloproteases-2 and -9 from Both Estrogen-Sensitive and -Insensitive Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Lett. 2011, 301, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, K.; Iwasaki, Y.; Daimon, M. Hypothalamic Regulation of Corticotropin-Releasing Factor under Stress and Stress Resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, E. Multi-Facets of Corticotropin-Releasing Factor in Modulating Inflammation and Angiogenesis. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 21, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, M.; Hippel, C.; Spiess, J. Corticotropin-releasing Factor (CRF) Rapidly Suppresses Apoptosis by Acting Upstream of the Activation of Caspases. J. Neurochem. 2003, 84, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reubi, J.C.; Waser, B.; Vale, W.; Rivier, J. Expression of CRF1 and CRF2 Receptors in Human Cancers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 3312–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaprara, A.; Pazaitou-Panayiotou, K.; Kortsaris, A.; Chatzaki, E. The Corticotropin Releasing Factor System in Cancer: Expression and Pathophysiological Implications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.E.; Wilgus, T.A. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Angiogenesis in the Regulation of Cutaneous Wound Repair. Adv. Wound Care 2014, 3, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J.; Jones, H.P. Implications of Corticotropin Releasing Factor in Targeted Anticancer Therapy. J. Pharm. Pract. 2010, 23, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neophytou, C.M.; Panagi, M.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Papageorgis, P. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Metastasis: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2021, 13, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koureta, M.; Karaglani, M.; Panagopoulou, M.; Balgkouranidou, I.; Papadaki-Anastasopoulou, A.; Zarouchlioti, C.; Dekavallas, S.; Kolios, G. Corticotropin Releasing Factor Receptors in Breast Cancer: Expression and Activity in Hormone-Dependent Growth in Vitro. Peptides 2020, 129, 170316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Chen, C.; Guo, R.; Wan, R.; Li, S. Role of Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Family Peptides in Androgen Receptor and Vitamin D Receptor Expression and Translocation in Human Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 684, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaprara, A.; Pazaitou-Panayiotou, K.; Chemonidou, M.C.; Constantinidis, T.C.; Lambropoulou, M.; Koffa, M.; Kiziridou, A.; Kakolyris, S.; Kortsaris, A.; Chatzaki, E. Distinct Distribution of Corticotropin Releasing Factor Receptors in Human Breast Cancer. Neuropeptides 2010, 44, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulidaki, A.; Dermitzaki, E.; Venihaki, M.; Karagianni, E.; Rassouli, O.; Andreakou, E.; Stournaras, C.; Margioris, A.N.; Tsatsanis, C. Corticotropin Releasing Factor Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Motility and Invasiveness. Mol. Cancer 2009, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziani, G.; Tentori, L.; Muzi, A.; Vergati, M.; Tringali, G.; Pozzoli, G.; Navarra, P. Evidence That Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Inhibits Cell Growth of Human Breast Cancer Cells via the Activation of CRH-R1 Receptor Subtype. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2007, 264, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, S.; Allan, A.; Markovic, D.; Walker, R.; Macartney, J.; Europe-Finner, N.; Tyson-Capper, A.; Grammatopoulos, D.K. Estrogen Alters the Splicing of Type 1 Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor in Breast Cancer Cells. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, ra53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimas, A.; Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Politi, A.; Sotiriadis, A.; Papanikolaou, A.; Dinas, K.; Petousis, S. The Expression and Possible Role of Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Family Peptides and Their Corresponding Receptors in Gynaecological Malignancies and Premalignant Conditions: A Systematic Review. Menopausal Rev. 2023, 22, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.-Y.; Wen, H.-Z.; Dai, L.-M.; Lou, Y.-X.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Yi, Y.-L.; Yan, X.-J.; Wu, Y.-R.; Sun, W.; Chen, P.-H. A Brain-Tumor Neural Circuit Controls Breast Cancer Progression in Mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e167725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Hamada, Y.; Narita, M.; Sato, D.; Tanaka, K.; Mori, T.; Tezuka, H.; Suda, Y.; Tamura, H. Elucidation of the Mechanisms Underlying Tumor Aggravation by the Activation of Stress-Related Neurons in the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus. Mol. Brain 2023, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Chen, C.; Li, S. CRH Suppressed TGFβ1-Induced Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition via Induction of E-Cadherin in Breast Cancer Cells. Cell. Signal. 2014, 26, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhr, L.E.B.; Wei, E.T.; Reed, R.K. Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Reduces Tumor Volume, Halts Further Growth, and Enhances the Effect of Chemotherapy in 4T1 Mammary Carcinoma in Mice. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.R. William Gossman Biochemistry, Endorphin—PubMed. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470306/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Sarkar, D.K.; Murugan, S.; Zhang, C.; Boyadjieva, N. Regulation of Cancer Progression by β-Endorphin Neuron. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.H. Role of Endorphins in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis and Recovery. In Endogenous Opioids; Kerr, P.L., Sirbu, C., Gregg, J.M., Eds.; Advances in Neurobiology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 35, pp. 87–106. ISBN 978-3-031-45492-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, D.K.; Zhang, C. Beta-Endorphin Neuron Regulates Stress Response and Innate Immunity to Prevent Breast Cancer Growth and Progression. In Vitamins & Hormones; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 93, pp. 263–276. ISBN 978-0-12-416673-8. [Google Scholar]

- Faith, R.E.; Liang, H.J.; Murgo, A.J.; Plotnikoff, N.P. Neuroimmunomodulation with Enkephalins: Enhancement of Human Natural Killer (NK) Cell Activity in Vitro. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1984, 31, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, R.E.; Liang, H.J.; Plotnikoff, N.P.; Murgo, A.J.; Nimeh, N.F. Neuroimmunomodulation with Enkephalins: In Vitro Enhancement of Natural Killer Cell Activity in Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes from Cancer Patients. Nat. Immun. Cell Growth Regul. 1987, 6, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Dueñas-Rodríguez, B.; Carrera-González, M.P.; Navarro-Cecilia, J.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Circulating Levels of β-Endorphin and Cortisol in Breast Cancer. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2021, 5, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, D.K.; Zhang, C.; Murugan, S.; Dokur, M.; Boyadjieva, N.I.; Ortigüela, M.; Reuhl, K.R.; Mojtehedzadeh, S. Transplantation of β-Endorphin Neurons into the Hypothalamus Promotes Immune Function and Restricts the Growth and Metastasis of Mammary Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6282–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.M.; Cascella, M. Physiology, Enkephalin. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Drell, T.L.; Joseph, J.; Lang, K.; Niggemann, B.; Zaenker, K.S.; Entschladen, F. Effects of Neurotransmitters on the Chemokinesis and Chemotaxis of MDA-MB-468 Human Breast Carcinoma Cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003, 80, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagon, I.S.; Porterfield, N.K.; McLaughlin, P.J. Opioid Growth Factor—Opioid Growth Factor Receptor Axis Inhibits Proliferation of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 2013, 238, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripolt, S.; Neubauer, H.A.; Knab, V.M.; Elmer, D.P.; Aberger, F.; Moriggl, R.; Fux, D.A. Opioids Drive Breast Cancer Metastasis through the δ-Opioid Receptor and Oncogenic STAT3. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, O.; Orho-Melander, M.; Manjer, J.; Svensson, T.; Almgren, P.; Nilsson, P.M.; Engström, G.; Hedblad, B.; Borgquist, S.; Hartmann, O. Stable Peptide of the Endogenous Opioid Enkephalin Precursor and Breast Cancer Risk. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2632–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabou, C.; Burcelin, R. GLP-1, the Gut-Brain, and Brain-Periphery Axes. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2011, 8, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaya, C.; Nomiyama, T.; Komatsu, S.; Kawanami, T.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Horikawa, T.; Yoshinaga, Y.; Yamashita, S. Exendin-4, a Glucagonlike Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist, Attenuates Breast Cancer Growth by Inhibiting NF-κB Activation. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 4218–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Bin Zafar, M.D.; Changez, M.I.K.; Abdullah, M.; Safwan, M.; Qamar, B.; Shinwari, A.; Rai, S. Exploring the Potential Impact of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Cancer Therapy. Minerva Endocrinol. 2023, 50, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanisavljevic, I.; Pavlovic, S.; Simovic Markovic, B.; Jurisevic, M.; Krajnovic, T.; Mijatovic, S.; Spasojevic, M.; Mitrovic, S.; Corovic, I.; Jovanovic, I. Semaglutide Decelerates the Growth and Progression of Breast Cancer by Enhancing the Acquired Antitumor Immunity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 181, 117668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligumsky, H.; Amir, S.; Arbel Rubinstein, T.; Guion, K.; Scherf, T.; Karasik, A.; Wolf, I.; Rubinek, T. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Analogs Activate AMP Kinase Leading to Reversal of the Warburg Metabolic Switch in Breast Cancer Cells. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanteet, A.A.; Attia, H.A.; Shaheen, S.; Alfayez, M.; Alshanawani, B. Anti-Proliferative Activity of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist on Obesity-Associated Breast Cancer: The Impact on Modulating Adipokines’ Expression in Adipocytes and Cancer Cells. Dose-Response 2021, 19, 1559325821995651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Tadros, A.B.; Montagna, G.; Bell, T.; Crowley, F.; Gallagher, E.J.; Dayan, J.H. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RAs) May Reduce the Risk of Developing Cancer-Related Lymphedema Following Axillary Lymph Node Dissection (ALND). Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1457363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, F.; Brown, S.; Gallagher, E.J.; Dayan, J.H. GLP-1 Receptor Agonist as an Effective Treatment for Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Case Report. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1392375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dian, Y.; Zeng, F.; Deng, G.; Lei, S. Association of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists with Risk of Cancers-Evidence from a Drug Target Mendelian Randomization and Clinical Trials. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 4688–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Iwaya, C.; Kawanami, T.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Horikawa, T.; Shigeoka, T.; Yanase, T.; Kawanami, D.; Nomiyama, T. Combined Treatment with Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Exendin-4 and Metformin Attenuates Breast Cancer Growth. Diabetol. Int. 2022, 13, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidan-Yaylalı, G.; Dodurga, Y.; Seçme, M.; Elmas, L. Antidiabetic Exendin-4 Activates Apoptotic Pathway and Inhibits Growth of Breast Cancer Cells. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 2647–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Duan, X.; Yuan, M.; Yu, J.; Hu, X.; Han, X.; Lan, L.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Activation by Liraglutide Promotes Breast Cancer through NOX4/ROS/VEGF Pathway. Life Sci. 2022, 294, 120370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadboorestan, A.; Tarighi, P.; Koosha, M.; Faghihi, H.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Montazeri, H. Growth Promotion and Increased ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters Expression by Liraglutide in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cell Line MDA-MB-231. Drug Res. 2021, 71, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G.F.; Mesquita, L.A.; Stein, C.; Aziz, M.; Zoldan, M.; Degobi, N.A.H.; Spiazzi, B.F.; Lopes Junior, G.L.; Colpani, V.; Gerchman, F. Do GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Increase the Risk of Breast Cancer? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funch, D.; Mortimer, K.; Li, L.; Norman, H.; Major-Pedersen, A.; Olsen, A.H.; Kaltoft, M.S.; Dore, D.D. Is There an Association between Liraglutide Use and Female Breast Cancer in a Real-World Setting? Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, B.M.; Yin, H.; Yu, O.H.Y.; Pollak, M.N.; Platt, R.W.; Azoulay, L. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Analogues and Risk of Breast Cancer in Women with Type 2 Diabetes: Population Based Cohort Study Using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMJ 2016, 355, i5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santella, C.; Yin, H.; Hicks, B.M.; Yu, O.H.Y.; Bouganim, N.; Azoulay, L. Weight-Lowering Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Detection of Breast Cancer Among Obese Women with Diabetes. Epidemiology 2020, 31, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.P.; Hernandez, A.; Vega, M.; Araya, E.; Romero, C. Conventional and New Proposals of GnRH Therapy for Ovarian, Breast, and Prostatic Cancers. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1143261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desaulniers, A.T.; White, B.R. Role of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone 2 and Its Receptor in Human Reproductive Cancers. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1341162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, T.; Fu, F.; Wang, A.; Liu, X. Preparation of Long-Acting Somatostatin and GnRH Analogues andTheir Applications in Tumor Therapy. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2022, 19, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delavari, B.; Bigdeli, B.; Khazeni, S.; Varamini, P. Nanodiamond-Protein Hybrid Nanoparticles: LHRH Receptor Targeted and Co-Delivery of Doxorubicin and Dasatinib for Triple Negative Breast Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 675, 125544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-P.; Lu, X. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Proliferation and Metastasis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2022, 50, 03000605221082895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefvand, M.; Mohammadi, Z.; Ghorbani, F.; Irajirad, R.; Abedi, H.; Seyedi, S.; Papi, A.; Montazerabadi, A. Investigation of Specific Targeting of Triptorelin-Conjugated Dextran-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles as a Targeted Probe in GnRH+ Cancer Cells in MRI. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2021, 2021, 5534848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, H.S.A.; Varamini, P. New Drug Delivery Strategies Targeting the GnRH Receptor in Breast and Other Cancers. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2021, 28, R251–R269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazesh, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Jalili, S.; Kavousipour, S.; Faraji, S.N.; Mokarram, P.; Pirhadi, S. Design and Characterization of a Recombinant Immunotoxin for Targeted Therapy of Breast Cancer Cells: In Vitro and in Silico Analyses. Life Sci. 2021, 265, 118866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründker, C.; Emons, G. The Role of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone in Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Taratula, O.; Taratula, O.; Schumann, C.; Minko, T. LHRH-Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayemi, J.D.; Salifu, A.A.; Eluu, S.C.; Uzonwanne, V.O.; Jusu, S.M.; Nwazojie, C.C.; Onyekanne, C.E. LHRH-Conjugated Drugs as Targeted Therapeutic Agents for the Specific Targeting and Localized Treatment of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluu, S.C.; Obayemi, J.D.; Yiporo, D.; Salifu, A.A.; Oko, A.O.; Onwudiwe, K.; Aina, T. Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH)-Conjugated Cancer Drug Delivery from Magnetite Nanoparticle-Modified Microporous Poly-Di-Methyl-Siloxane (PDMS) Systems for the Targeted Treatment of Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndinguri, M.; Middleton, L.; Unrine, J.; Lui, S.; Rollins, J.; Nienaber, E.; Spease, C.; Williams, A.; Cormier, L. Therapeutic Dosing and Targeting Efficacy of Pt-Mal-LHRH towards Triple Negative Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumkoon, T.; Noree, C.; Boonserm, P. Engineering BinB Pore-Forming Toxin for Selective Killing of Breast Cancer Cells. Toxins 2023, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, L.E.; Black, C.A.; Rollins, J.D.; Overbay, B.; Shiferawe, S.; Elliott, A.; Reitz, S. Synthesis of Radiolabeled Technetium- and Rhenium-Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (99m Tc/Re-Acdien-LHRH) Conjugates for Targeted Detection of Breast Cancer Cells Overexpressing the LHRH Receptor. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1846–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Liu, Q.; Suby, N.; Xiao, W.; Agrawal, R.; Vu, M.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Lam, K.S. LHRH-Targeted Redox-Responsive Crosslinked Micelles Impart Selective Drug Delivery and Effective Chemotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2001196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, H.; Dhillo, W.S.; Jayasena, C.N. Comprehensive Review on Kisspeptin and Its Role in Reproductive Disorders. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 30, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, K.T.; Welch, D.R. The KISS1 Metastasis Suppressor: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Utility. Front. Biosci. 2006, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, S.; Brackstone, M.; Wondisford, F.; Babwah, A.V.; Bhattacharya, M. KISS1/KISS1R and Breast Cancer: Metastasis Promoter. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2019, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzabek, K.; Koda, M.; Kozlowski, L.; Milewski, R.; Wolczynski, S. Immunohistochemical Study of KiSS1 and KiSS1R Expression in Human Primary Breast Cancer: Association with Breast Cancer Receptor Status, Proliferation Markers and Clinicopathological Features. Histol. Histopathol. 2015, 30, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.B.; Oksuz, H.; Ilgaz, N.S.; Ocal, I.; Tazehkand, M.N. The Role of Kisspeptin on Aromatase Expression in Breast Cancer. Bratisl. Med. J. 2019, 119, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, A.; Dragan, M.; Tirona, R.G.; Hardy, D.B.; Brackstone, M.; Tuck, A.B.; Babwah, A.V.; Bhattacharya, M. G Protein-Coupled KISS1 Receptor Is Overexpressed in Triple Negative Breast Cancer and Promotes Drug Resistance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goertzen, C.G.; Dragan, M.; Turley, E.; Babwah, A.V.; Bhattacharya, M. KISS1R Signaling Promotes Invadopodia Formation in Human Breast Cancer Cell via β-Arrestin2/ERK. Cell Signal. 2016, 28, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, M.M.; Dragan, M.; Mehta, M.M.; Hess, D.A.; Brackstone, M.; Tuck, A.B. The Matrix Protein Fibulin-3 Promotes KISS1R Induced Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cell Invasion. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 30034–30052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dragan, M.; Nguyen, M.-U.; Guzman, S.; Goertzen, C.; Brackstone, M.; Dhillo, W.S.; Bech, P.R.; Clarke, S. G Protein-Coupled Kisspeptin Receptor Induces Metabolic Reprograming and Tumorigenesis in Estrogen Receptor-Negative Breast Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Al-Odaini, A.A.; Wang, Y.; Korah, J.; Dai, M.; Xiao, L.; Ali, S.; Lebrun, J.-J. KiSS1 Gene as a Novel Mediator of TGFβ-Mediated Cell Invasion in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Cell. Signal. 2018, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azubuike, U.F.; Newton, C.L.; Van Den Bout, I. Lack of Oestrogen Receptor Expression in Breast Cancer Cells Does Not Correlate with Kisspeptin Signalling and Migration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ricks-Santi, L.J.; Naab, T.J.; Rajack, F.; Beyene, D.; Abbas, M.; Kassim, O.O.; Copeland, R.L.; Kanaan, Y. Inverse Correlation of KISS1 and KISS1R Expression in Triple-Negative Breast Carcinomas from African American Women. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2022, 19, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, S.; Zaki, M.; Sultan, M.; Dwedar, F.; Elzain Zidan, E.H. Evaluation of KISS1 Receptor Gene Expression in Egyptian Female Patients with Breast Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Bhatt, M.L.B.; Singh, S.P.; Kumar, V.; Goel, M.M.; Mishra, D.P.; Kumar, R. Evaluation of KiSS1 as a Prognostic Biomarker in North Indian Breast Cancer Cases. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kaverina, N.; Borovjagin, A.V.; Kadagidze, Z.; Baryshnikov, A.; Baryshnikova, M.; Malin, D. Astrocytes Promote Progression of Breast Cancer Metastases to the Brain via a KISS1-Mediated Autophagy. Autophagy 2017, 13, 1905–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antar, S.; Mokhtar, N.; Abd Elghaffar, M.A.; Seleem, A.K. Association of Polymorphisms in Metastasis Suppressor Genes NME1 and KISS1 with Breast Cancer Development and Metastasis. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 32, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-H.; Cho, S.-G. Kisspeptin Inhibits Cancer Growth and Metastasis via Activation of EIF2AK2. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 7585–7590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulzadeh, Z.; Ghods, R.; Kazemi, T.; Mirzadegan, E.; Ghaffari-Tabrizi-Wizsy, N.; Rezania, S.; Kazemnejad, S. Placental Kisspeptins Differentially Modulate Vital Parameters of Estrogen Receptor-Positive and -Negative Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonov, M.E.; Borovjagin, A.V.; Kaverina, N.; Xiao, T.; Kadagidze, Z.; Lesniak, M.; Baryshnikova, M.; Ulasov, I.V. KISS1 Tumor Suppressor Restricts Angiogenesis of Breast Cancer Brain Metastases and Sensitizes Them to Oncolytic Virotherapy in Vitro. Cancer Lett. 2018, 417, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.-Q.; Zhao, Y. Kisspeptin-10 Inhibits the Migration of Breast Cancer Cells by Regulating Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.Q.; Zhao, Y. Kisspeptin 10 Inhibits the Warburg Effect in Breast Cancer through the Smad Signaling Pathway: Both in Vitro and in Vivo. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.-H.; Cho, S.-G. Melatonin-Induced KiSS1 Expression Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Invasiveness. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 2511–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gründker, C.; Bauerschmitz, G.; Knapp, J.; Schmidt, E.; Olbrich, T.; Emons, G. Inhibition of SDF-1/CXCR4-Induced Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition by Kisspeptin-10. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 152, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.H.; Abele, H.; Plappert, C.F. The Role of Oxytocin and the Effect of Stress During Childbirth: Neurobiological Basics and Implications for Mother and Child. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 742236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassoni, P.; Sapino, A.; Marrocco, T.; Chini, B.; Bussolati, G. Oxytocin and Oxytocin Receptors in Cancer Cells and Proliferation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2004, 16, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latt, H.M.; Matsushita, H.; Morino, M.; Koga, Y.; Michiue, H.; Nishiki, T.; Tomizawa, K.; Matsui, H. Oxytocin Inhibits Corticosterone-Induced Apoptosis in Primary Hippocampal Neurons. Neuroscience 2018, 379, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gruber, C.W.; Alewood, P.F.; Möller, A.; Muttenthaler, M. The Oxytocin Receptor Signalling System and Breast Cancer: A Critical Review. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5917–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, P.; Sanchez De La Rosa, C.; Möller, A.; Alewood, P.F.; Muttenthaler, M. Targeting the Oxytocin Receptor for Breast Cancer Management: A Niche for Peptide Tracers. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassoni, P.; Sapino, A.; Negro, F.; Bussolati, G. Oxytocin Inhibits Proliferation of Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Virchows Arch. 1994, 425, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; San, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, A.; Xie, W.; Chen, Y.; Lu, X. Oxytocin Receptor Induces Mammary Tumorigenesis through Prolactin/p-STAT5 Pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariana, M.; Pornour, M.; Mehr, S.S.; Vaseghi, H.; Ganji, S.M.; Alivand, M.R.; Salari, M.; Akbari, M.E. Preventive Effects of Oxytocin and Oxytocin Receptor in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis. Pers. Med. 2019, 16, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Muttenthaler, M. High Oxytocin Receptor Expression Linked to Increased Cell Migration and Reduced Survival in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behtaji, S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Sayad, A.; Sattari, A.; Rederstorff, M.; Taheri, M. Identification of Oxytocin-Related lncRNAs and Assessment of Their Expression in Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, T.S.; Kononchuk, V.V.; Sidorov, S.V.; Obukhova, D.A.; Abdullin, G.R.; Gulyaeva, L.F. Oxytocin Receptor Expression Is Associated with Estrogen Receptor Status in Breast Tumors. Biomeditsinskaya Khimiya 2021, 67, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Dueñas-Rodríguez, B.; Carrera-González, M.P.; Navarro-Cecilia, J.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Insulin-Regulated Aminopeptidase in Women with Breast Cancer: A Role beyond the Regulation of Oxytocin and Vasopressin. Cancers 2020, 12, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Huang, R.; Li, A.; Yu, S.; Yao, S.; Xu, J.; Tang, L.; Li, W.; Gan, C.; Cheng, H. The Role of the Oxytocin System in the Resilience of Patients with Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1187477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.M.; Heydari, Z.; Rahimi, M.; Bazgir, B.; Shirvani, H.; Alipour, S.; Heidarian, Y.; Khalighfard, S.; Isanejad, A. Oxytocin Mediates the Beneficial Effects of the Exercise Training on Breast Cancer. Exp. Physiol. 2018, 103, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jailani, A.B.A.; Bigos, K.J.A.; Avgoustou, P.; Egan, J.L.; Hathway, R.A.; Skerry, T.M.; Richards, G.O. Targeting the Adrenomedullin-2 Receptor for the Discovery and Development of Novel Anti-Cancer Agents. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2022, 17, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, L.; Li, M.; Feng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Intermedin (Adrenomedullin 2) Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis via Src/c-Myc-Mediated Ribosome Production and Protein Translation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 195, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.; Zinovkin, D.; Pranjol, M.Z.I. Endothelin-1 and Its Role in Cancer and Potential Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olender, J.; Nowakowska-Zajdel, E.; Walkiewicz, K.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M. Endothelins and Carcinogenesis. Postępy Hig. Med. Dośw. 2016, 70, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendinelli, P.; Maroni, P.; Matteucci, E.; Luzzati, A.; Perrucchini, G.; Desiderio, M.A. Microenvironmental Stimuli Affect Endothelin-1 Signaling Responsible for Invasiveness and Osteomimicry of Bone Metastasis from Breast Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamkus, D.; Sikorskii, A.; Gallo, K.A.; Wiese, D.A.; Leece, C.; Madhukar, B.V.; Chivu, S.C.; Chitneni, S.; Dimitrov, N.V. Endothelin-1 Enriched Tumor Phenotype Predicts Breast Cancer Recurrence. ISRN Oncol. 2013, 2013, 385398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinar, I.; Yayla, M.; Celik, M.; Bilen, A.; Bayraktutan, Z. Role of Endothelin 1 on Proliferation and Migration of Human MCF-7 Cells. Eurasian J. Med. 2020, 52, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halaka, M.; Hired, Z.A.; Rutledge, G.E.; Hedgepath, C.M.; Anderson, M.P.; John, H.S.; Do, J.M. Differences in Endothelin B Receptor Isoforms Expression and Function in Breast Cancer Cells. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 2688–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Han, S.; Cui, M.; Xue, J.; Ai, L.; Sun, L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C. Knockdown of Endothelin Receptor B Inhibits the Progression of Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1448, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoves, M.; Kotzki, S.; Hazane-Puch, F.; Lemarié, E.; Bouyon, S.; Vollaire, J. Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia, a Hallmark of Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Promotes 4T1 Breast Cancer Development through Endothelin-1 Receptors. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askoxylakis, V.; Ferraro, G.B.; Badeaux, M.; Kodack, D.P.; Kirst, I.; Shankaraiah, R.C.; Wong, C.S.F.; Duda, D.G.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Dual Endothelin Receptor Inhibition Enhances T-DM1 Efficacy in Brain Metastases from HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Hanibuchi, M.; Kim, S.-J.; Yu, H.; Kim, M.S.; He, J.; Langley, R.R.; Lehembre, F.; Regenass, U.; Fidler, I.J. Treatment of Experimental Human Breast Cancer and Lung Cancer Brain Metastases in Mice by Macitentan, a Dual Antagonist of Endothelin Receptors, Combined with Paclitaxel. Neuro-Oncol. 2016, 18, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnarao, K.; Bruno, K.A.; Di Florio, D.N.; Edenfield, B.H.; Whelan, E.R.; Macomb, L.P.; McGuire, M.M. Upregulation of Endothelin-1 May Predict Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Women with Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maayah, Z.H.; Takahara, S.; Alam, A.S.; Ferdaoussi, M.; Sutendra, G.; El-Kadi, A.O.S.; Mackey, J.R.; Pituskin, E.; Paterson, D.I.; Dyck, J.R.B. Breast Cancer Diagnosis Is Associated with Relative Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Elevated Endothelin-1 Signaling. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maayah, Z.H.; Ferdaoussi, M.; Boukouris, A.E.; Takahara, S.; Das, S.K.; Khairy, M. Endothelin Receptor Blocker Reverses Breast Cancer–Induced Cardiac Remodeling. JACC CardioOncol. 2023, 5, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampenrieder, S.P.; Hufnagl, C.; Brechelmacher, S.; Huemer, F.; Hackl, H.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Romeder, F. Endothelin-1 Genetic Polymorphism as Predictive Marker for Bevacizumab in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Pharmacogenom. J. 2017, 17, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, R.; Schwartsmann, G. Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptors in the Central Nervous System: Role in Brain Function and as a Drug Target. Front. Endocrinol. 2012, 3, 38969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Yuan, A.; Li, Z. Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Links Stressor to Cancer Progression. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 136, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Ma, Q.; Bian, H.; Meng, X.; Jin, J. Novel Insight on GRP/GRPR Axis in Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zhao, X.; Sun, T.; Liu, Y.; Gu, Q.; Sun, B. Role of Gastrin-Releasing Peptides in Breast Cancer Metastasis. Hum. Pathol. 2012, 43, 2342–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baun, C.; Olsen, B.B.; Alves, C.M.L.; Ditzel, H.J.; Terp, M.; Hildebrandt, M.G.; Poulsen, C.A. Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor as Theranostic Target in Estrogen-Receptor Positive Breast Cancer: A Preclinical Study of the Theranostic Pair [55Co]Co- and [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-RM26. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2024, 138–139, 108961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baun, C.; Naghavi-Behzad, M.; Hildebrandt, M.G.; Gerke, O.; Thisgaard, H. Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor as a Theranostic Target in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Scoping Review. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2024, 54, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomena, J.; Vári, B.; Oláh-Szabó, R.; Biri-Kovács, B.; Bősze, S.; Borbély, A.; Soós, Á.; Ranđelović, I.; Tóvári, J.; Mező, G. Targeting the Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor (GRP-R) in Cancer Therapy: Development of Bombesin-Based Peptide–Drug Conjugates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, A.; Engelbrecht, S.; Läppchen, T.; Rominger, A.; Gourni, E. GRPR-Targeting Radiotheranostics for Breast Cancer Management. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1250799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, E.; Aksoy, T.; Can Trabulus, F.D.; Kelten Talu, C.; Yeni, B.; Çermik, T.F. The Association of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/Computed Tomography Parameters with Tissue Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor and Integrin Avβ3 Receptor Levels in Patients with Breast Cancer. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2020, 41, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalski, K.; Stoykow, C.; Bronsert, P.; Juhasz-Böss, I.; Meyer, P.T.; Ruf, J.; Erbes, T.; Asberger, J. Association between Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor Expression as Assessed with [68Ga]Ga-RM2 PET/CT and Histopathological Tumor Regression after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Primary Breast Cancer. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2020, 86–87, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgat, C.; Schollhammer, R.; Macgrogan, G.; Barthe, N.; Vélasco, V.; Vimont, D.; Cazeau, A.-L.; Fernandez, P.; Hindié, E. Comparison of the Binding of the Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor (GRP-R) Antagonist 68Ga-RM2 and 18F-FDG in Breast Cancer Samples. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgat, C.; MacGrogan, G.; Brouste, V.; Vélasco, V.; Sévenet, N.; Bonnefoi, H.; Fernandez, P.; Debled, M.; Hindié, E. Expression of Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor in Breast Cancer and Its Association with Pathologic, Biologic, and Clinical Parameters: A Study of 1,432 Primary Tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennefather, J.N.; Lecci, A.; Candenas, M.L.; Patak, E.; Pinto, F.M.; Maggi, C.A. Tachykinins and Tachykinin Receptors: A Growing Family. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 1445–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonists as Antitumor Drugs in Gastrointestinal Cancer: A New Approach. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigioni, M.; Benzo, A.; Irrissuto, C.; Maggi, C.A.; Goso, C. Role of NK-1 and NK-2 Tachykinin Receptor Antagonism on the Growth of Human Breast Carcinoma Cell Line MDA-MB-231. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2005, 16, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, E.; Erin, N. Differential Consequences of Neurokinin Receptor 1 and 2 Antagonists in Metastatic Breast Carcinoma Cells; Effects Independent of Substance, P. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Joshi, D.D.; Hameed, M.; Qian, J.; Gascón, P.; Maloof, P.B.; Mosenthal, A.; Rameshwar, P. Increased Expression of Preprotachykinin-I and Neurokinin Receptors in Human Breast Cancer Cells: Implications for Bone Marrow Metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, S.; Boada, M.D. Neuropeptide-Induced Modulation of Carcinogenesis in a Metastatic Breast Cancer Cell Line (MDA-MB-231LUC+). Cancer Cell Int. 2018, 18, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malendowicz, L.K.; Rucinski, M. Neuromedins NMU and NMS: An Updated Overview of Their Functions. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 713961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-J.; Kim, S.-R.; Kim, M.-K.; Choi, K.-S.; Jang, H.-O.; Yun, I.; Bae, S.-K.; Bae, M.-K. Neuromedin B Receptor Antagonist Suppresses Tumor Angiogenesis and Tumor Growth in Vitro and in Vivo. Cancer Lett. 2011, 312, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Kim, M.-K.; Choi, K.-S.; Jeong, J.-W.; Bae, S.-K.; Kim, H.J.; Bae, M.-K. Neuromedin B Receptor Antagonism Inhibits Migration, Invasion, and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-J.; Kim, M.-K.; Kim, S.-R.; Bae, S.-K.; Bae, M.-K. Hypoxia Regulates the Expression of the Neuromedin B Receptor through a Mechanism Dependent on Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garczyk, S.; Klotz, N.; Szczepanski, S.; Denecke, B.; Antonopoulos, W.; Von Stillfried, S.; Knüchel, R.; Rose, M.; Dahl, E. Oncogenic Features of Neuromedin U in Breast Cancer Are Associated with NMUR2 Expression Involving Crosstalk with Members of the WNT Signaling Pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36246–36265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, V.G.; Crown, J.; Porter, R.K.; O’Driscoll, L. Neuromedin U Alters Bioenergetics and Expands the Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype in HER2-positive Breast Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 2771–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Corcoran, C.; Shiels, L.; Germano, S.; Breslin, S.; Madden, S.; McDermott, M.S. Neuromedin U: A Candidate Biomarker and Therapeutic Target to Predict and Overcome Resistance to HER-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 3821–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, V.G.; O’Neill, S.; Salimu, J.; Breslin, S.; Clayton, A.; Crown, J.; O’Driscoll, L. Resistance to HER2-Targeted Anti-Cancer Drugs Is Associated with Immune Evasion in Cancer Cells and Their Derived Extracellular Vesicles. OncoImmunology 2017, 6, e1362530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlestedt, C.; Ekman, R.; Widerlöv, E. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and the Central Nervous System: Distribution Effects and Possible Relationship to Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1989, 13, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.L.; Rodríguez, F.D.; Coveñas, R. Neuropeptide Y Peptide Family and Cancer: Antitumor Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualsaud, N.; Caprio, L.; Galli, S.; Krawczyk, E.; Alamri, L.; Zhu, S.; Gallicano, G.I.; Kitlinska, J. Neuropeptide Y/Y5 Receptor Pathway Stimulates Neuroblastoma Cell Motility Through RhoA Activation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 627090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscica, M.; Dozio, E.; Motta, M.; Magni, P. Role of Neuropeptide Y and Its Receptors in the Progression of Endocrine-Related Cancer. Peptides 2007, 28, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascetta, S.A.; Kirsh, S.M.; Cameron, M.; Uniacke, J. Pharmacological Inhibition of Neuropeptide Y Receptors Y1 and Y5 Reduces Hypoxic Breast Cancer Migration, Proliferation, and Signaling. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, P.J.; Pascetta, S.A.; Kirsh, S.M.; Al-Khazraji, B.K.; Uniacke, J. Expression of Hypoxia Inducible Factor–Dependent Neuropeptide Y Receptors Y1 and Y5 Sensitizes Hypoxic Cells to NPY Stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, S.; Ali, M.; Yahya, A.; Haider, K.H.; Balasubramaniam, A.; Amlal, H. Neuropeptide Y Y5 Receptor Promotes Cell Growth through Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling and Cyclic AMP Inhibition in a Human Breast Cancer Cell Line. Mol. Cancer Res. 2010, 8, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; Cheng, L.; Ma, C.; Xiao, L.; Xu, D.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, H. NPY1R Is a Novel Peripheral Blood Marker Predictive of Metastasis and Prognosis in Breast Cancer Patients. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 9, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawoud, M.M.; Abdelaziz, K.K.-E.; Alhanafy, A.M.; Ali, M.S.E.-d.; Elkhouly, E.A.B. Clinical Significance of Immunohistochemical Expression of Neuropeptide Y1 Receptor in Patients with Breast Cancer in Egypt. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2021, 29, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memminger, M.; Keller, M.; Lopuch, M.; Pop, N.; Bernhardt, G.; von Angerer, E.; Buschauer, A. The Neuropeptide Y Y1 Receptor: A Diagnostic Marker? Expression in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells Is Down-Regulated by Antiestrogens In Vitro and in Xenografts. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.; Thangavel, H.; Abdulkareem, N.M.; Vasaikar, S.; De Angelis, C.; Bae, L.; Cataldo, M.L.; Nanda, S.; Fu, X.; Zhang, B. NPY1R Exerts Inhibitory Action on Estradiol-Stimulated Growth and Predicts Endocrine Sensitivity and Better Survival in ER-Positive Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tian, Y.; Wu, A. Neuropeptide Y Receptors: A Promising Target for Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Regen. Biomater. 2015, 2, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, P.J.; Jackson, D.N. Neuropeptide Y Y5-Receptor Activation on Breast Cancer Cells Acts as a Paracrine System That Stimulates VEGF Expression and Secretion to Promote Angiogenesis. Peptides 2013, 48, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, K.; Kostevšek, N.; Romeo, S.; Bassanini, I. Neuropeptide Y Receptors 1 and 2 as Molecular Targets in Prostate and Breast Cancer Therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 187, 118117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.H.; Real, C.C.; Malafaia, O. Heterobivalent Dual-Target Peptide for Integrin-Avβ3 and Neuropeptide Y Receptors on Breast Tumor. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maschauer, S.; Ott, J.J.; Bernhardt, G.; Kuwert, T.; Keller, M.; Prante, O. 18F-Labelled Triazolyl-Linked Argininamides Targeting the Neuropeptide Y Y1R for PET Imaging of Mammary Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, M.E.; Tejería, E.; Zirbesegger, K.; Savio, E.; Terán, M.; Rey Ríos, A.M. Development and Characterization of Two Novel 68Ga-labelled Neuropeptide Y Short Analogues with Potential Application in Breast Cancer Imaging. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 98, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.E.; Tejería, E.; Rey Ríos, A.M.; Terán, M. Development and Characterization of a 99mTc-labeled Neuropeptide Y Short Analog with Potential Application in Breast Cancer Imaging. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2020, 95, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Pan, J.; Lin, K.-S.; Dude, I.; Lau, J.; Zeisler, J.; Merkens, H.; Jenni, S.; Guérin, B.; Bénard, F. Targeting the Neuropeptide Y1 Receptor for Cancer Imaging by Positron Emission Tomography Using Novel Truncated Peptides. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 3657–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelletto, V.; Edwards-Gayle, C.J.C.; Greco, F.; Hamley, I.W.; Seitsonen, J.; Ruokolainen, J. Self-Assembly, Tunable Hydrogel Properties, and Selective Anti-Cancer Activity of a Carnosine-Derived Lipidated Peptide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 33573–33580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yuan, B.; Xing, J.; Li, M.; Gao, Q.; Xu, K.; Akakuru, O.U. The Neuropeptide Y 1 Receptor Ligand-Modified Cell Membrane Promotes Targeted Photodynamic Therapy of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks for Breast Cancer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 11280–11287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.; Shende, P. Experimental Aspects of NPY-decorated Gold Nanoclusters Using Randomized Hybrid Design against Breast Cancer Cell Line. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 16, 2100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, D.; Krieghoff, J.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Double Methotrexate-Modified Neuropeptide Y Analogues Express Increased Toxicity and Overcome Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer Cells. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 3409–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ge, X.; Zhu, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, P.; Akakuru, O.U.; Wu, A.; Li, J. Transformable Neuropeptide Prodrug with Tumor Microenvironment Responsiveness for Tumor Growth and Metastasis Inhibition of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Gelais, F.; Jomphe, C.; Trudeau, L.-É. The Role of Neurotensin in Central Nervous System Pathophysiology: What Is the Evidence? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006, 31, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaou, S.; Qiu, S.; Fiorentino, F.; Simillis, C.; Rasheed, S.; Tekkis, P.; Kontovounisios, C. The Role of Neurotensin and Its Receptors in Non-Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Review. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Pellino, G.; Fiorentino, F.; Rasheed, S.; Darzi, A.; Tekkis, P.; Kontovounisios, C. A Review of the Role of Neurotensin and Its Receptors in Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 6456257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wong, N.; Tang, Z. Weibo Cai Development of 177Lu-FL-091 for the Treatment of NTSR1-Positive Cancers | Journal of Nuclear Medicine. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 2418575. [Google Scholar]

- Christou, N.; Blondy, S.; David, V.; Verdier, M.; Lalloué, F.; Jauberteau, M.-O.; Mathonnet, M.; Perraud, A. Neurotensin Pathway in Digestive Cancers and Clinical Applications: An Overview. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupouy, S.; Doan, V.K.; Wu, Z.; Mourra, N.; Liu, J.; De Wever, O.; Llorca, F.P.; Cayre, A.; Kouchkar, A.; Gompel, A. Activation of EGFR, HER2 and HER3 by Neurotensin/Neurotensin Receptor 1 Renders Breast Tumors Aggressive yet Highly Responsive to Lapatinib and Metformin in Mice. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 8235–8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, O.; Maisel, A.S.; Almgren, P.; Manjer, J.; Belting, M.; Hedblad, B. Plasma Proneurotensin and Incidence of Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, Breast Cancer, and Mortality. JAMA 2012, 308, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, N.; Mougel, R.; Riley, G.; Bruand, M.; Gauchotte, G.; Agopiantz, M. Neurotensin and Its Involvement in Female Hormone-Sensitive Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.L.; Coveñas, R. The Neurotensinergic System: A Target for Cancer Treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 3231–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souazé, F.; Dupouy, S.; Viardot-Foucault, V.; Bruyneel, E.; Attoub, S.; Gespach, C.; Gompel, A.; Forgez, P. Expression of Neurotensin and NT1 Receptor in Human Breast Cancer: A Potential Role in Tumor Progression. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 6243–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, S.; Pundavela, J.; Demont, Y.; Faulkner, S.; Keene, S.; Attia, J.; Jiang, C.C.; Zhang, X.D.; Walker, M.M.; Hondermarck, H. Sortilin Is Associated with Breast Cancer Aggressiveness and Contributes to Tumor Cell Adhesion and Invasion. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10473–10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupouy, S.; Viardot-Foucault, V.; Alifano, M.; Souazé, F.; Plu-Bureau, G.; Chaouat, M.; Lavaur, A. The Neurotensin Receptor-1 Pathway Contributes to Human Ductal Breast Cancer Progression. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgat, C.; Brouste, V.; Chastel, A.; Vélasco, V.; Macgrogan, G.; Hindié, E. Expression of Neurotensin Receptor-1 (NTS1) in Primary Breast Tumors, Cellular Distribution, and Association with Clinical and Biological Factors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 190, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graefe, S.B.; Rahimi, N.; Mohiuddin, S.S. Biochemistry, Substance P. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Coveñas, R.; Rodríguez, F.D.; Muñoz, M. The Neurokinin-1 Receptor: A Promising Antitumor Target. Receptors 2022, 1, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveñas, R.; Muñoz, M. Involvement of the Substance P/Neurokinin-1 Receptor System in Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanaban, V.; Keller, I.; Seltzer, E.S.; Ostendorf, B.N.; Kerner, Z.; Tavazoie, S.F. Neuronal Substance P Drives Metastasis through an Extracellular RNA–TLR7 Axis. Nature 2024, 633, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; González-Ortega, A.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; Carranza, A.; Garcia-Recio, S.; Almendro, V.; Coveñas, R. The Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonist Aprepitant Is a Promising Candidate for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1658–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Coveñas, R. Triple Negative Breast Cancer: How Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonists Could Be Used as a New Therapeutic Approach. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Ganea, D. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide: A Neuropeptide with Pleiotropic Immune Functions. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.M.; Ji, S.; Cai, H.; Maudsley, S.; Martin, B. Therapeutic Potential of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide and Its Receptors in Neurological Disorders. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets 2010, 9, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, T.W.; Nuche-Berenguer, B.; Jensen, R.T. VIP/PACAP, and Their Receptors and Cancer. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2017, 23, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Lei, W.I.; Lee, L.T.O. The Role of Neuropeptide-Stimulated cAMP-EPACs Signalling in Cancer Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittikulsuth, W.; Nakano, D.; Kitada, K.; Uyama, T.; Ueda, N.; Asano, E.; Okano, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Nishiyama, A. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Blockade Suppresses Tumor Growth by Regulating Macrophage Polarization and Function in CT26 Tumor-Bearing Mice. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Qian, W.; Song, G.; Hou, X. Effect of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide on Gastric Adenocarcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 22, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, S.; Ozasa, K.; Uehara, T.; Yokoyama, R.; Nakazawa, T.; Yanamoto, S.; Ago, Y. Dimerisation of the VIP Receptor VIPR2 Is Essential to Its Binding VIP and Gαi Proteins, and to Its Functions in Breast Cancer Cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 3612–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes-e-Silva, A. The Renin–Angiotensin System and Diabetes: An Update. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambados, N.; Walther, T.; Nahmod, K.; Tocci, J.M.; Rubinstein, N.; Böhme, I. Angiotensin-(1-7) Counteracts the Transforming Effects Triggered by Angiotensin II in Breast Cancer Cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 88475–88487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, E.; Silva, A.C.; Sampaio, W.O. The Role of Angiotensin–(1-7) in Cancer. In Angiotensin-(1-7); Santos, R.A.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 219–229. ISBN 978-3-030-22695-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, J.; Cai, Y.; Xu, R.; Yu, X.; Han, X.; Weng, M.; Chen, L.; Ma, T.; Gao, T.; Gao, F. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Identifies Immuno-Hot Tumors Suggesting Angiotensin-(1–7) as a Sensitizer for Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer. Biol. Proced. Online 2022, 24, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, E.R.; Jialal, I. Biochemistry, Ghrelin. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cassoni, P.; Papotti, M.; Ghè, C.; Catapano, F.; Sapino, A.; Graziani, A.; Deghenghi, R.; Reissmann, T.; Ghigo, E.; Muccioli, G. Identification, Characterization, and Biological Activity of Specific Receptors for Natural (Ghrelin) and Synthetic Growth Hormone Secretagogues and Analogs in Human Breast Carcinomas and Cell Lines1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 1738–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, P.L.; Murray, R.E.; Yeh, A.H.; McNamara, J.F.; Duncan, R.P.; Francis, G.D.; Herington, A.C.; Chopin, L.K. Expression and Function of the Ghrelin Axis, Including a Novel Preproghrelin Isoform, in Human Breast Cancer Tissues and Cell Lines. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2005, 12, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönberg, M.; Nilsson, C.; Markholm, I.; Hedenfalk, I.; Blomqvist, C.; Holmberg, L.; Tiensuu Janson, E.; Fjällskog, M.-L. Ghrelin Expression Is Associated with a Favorable Outcome in Male Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellatt, A.J.; Lundgreen, A.; Wolff, R.K.; Hines, L.; John, E.M.; Slattery, M.L. Energy Homeostasis Genes and Survival after Breast Cancer Diagnosis: The Breast Cancer Health Disparities Study. Cancer Causes Control 2016, 27, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, G. Peptide YY(1-36) and Peptide YY(3-36): Part, I. Distribution, Release and Actions. Obes. Surg. 2006, 16, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisé, K.R.; Rongione, A.J.; Laird, E.C.; McFadden, D.W. Peptide YY Inhibits Growth of Human Breast Cancerin Vitroandin Vivo. J. Surg. Res. 1999, 82, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, T.; Towfigh, S.; Simon, N.; McFadden, D.W. Peptide YY and Vitamin E Inhibit Hormone-Sensitive and -Insensitive Breast Cancer Cells. J. Surg. Res. 2000, 91, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, S.; Wu, M. Novel Insights into Noncanonical Open Reading Frames in Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Rev. Cancer 2022, 1877, 188755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Li, F.; Guo, B.; Zhang, S. LncRNA-Encoded Polypeptide ASRPS Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Angiogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukić, I.; Kolobarić, N.; Stupin, A.; Matić, A.; Kozina, N.; Mihaljević, Z. Carnosine, Small but Mighty—Prospect of Use as Functional Ingredient for Functional Food Formulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solana-Manrique, C.; Sanz, F.J.; Martínez-Carrión, G.; Paricio, N. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects of Carnosine: Therapeutic Implications in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, S.; Sibbitts, J.; Privitera, A.; Cardaci, V.; Di Pietro, L.; Leggio, L.; Iraci, N.; Lunte, S.M.; Caruso, G. The Anti-Cancer Activity of the Naturally Occurring Dipeptide Carnosine: Potential for Breast Cancer. Cells 2023, 12, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habra, K.; Pearson, J.R.D.; Le Vu, P.; Puig-Saenz, C.; Cripps, M.J.; Khan, M.A.; Turner, M.D.; Sale, C.; McArdle, S.E.B. Anticancer Actions of Carnosine in Cellular Models of Prostate Cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, R.M.; Gaafar, P.M.E.; Hazzah, H.A.; Helmy, M.W.; Abdallah, O.Y. Chemotherapeutic Potential of L-Carnosine from Stimuli-Responsive Magnetic Nanoparticles Against Breast Cancer Model. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 891–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhem, S.A.; Saadah, L.M.; Attallah, Z.S.; Mansi, I.A.; Hamed, S.H.; Talib, W.H. Deciphering Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Inhibition Dynamics: Carnosine’s Modulatory Role in Breast Cancer Proliferation—A Clinical Sciences Perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, A.; Drljača Lero, J.; Miljković, D.; Popović, M.; Marinović, J.; Ljubković, M.; Andjelković, Z.; Čapo, I. Karnozin EXTRA® Causes Changes in Mitochondrial Bioenergetics Response in MCF-7 and MRC-5 Cell Lines. Biotech. Histochem. 2025, 100, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.M.A.; Abdelfattah-Hassan, A.; Eldoumani, H.; Essawi, W.M.; Alsahli, T.G.; Alharbi, K.S.; Alzarea, S.I.; Al-Hejaili, H.Y.; Gaafar, S.F. Evaluation of Anti-Cancer Effects of Carnosine and Melittin-Loaded Niosomes in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1258387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaafar, P.M.E.; El-Salamouni, N.S.; Farid, R.M.; Hazzah, H.A.; Helmy, M.W.; Abdallah, O.Y. Pegylated Liquisomes: A Novel Combined Passive Targeting Nanoplatform of L-Carnosine for Breast Cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 602, 120666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian-Moghadam, H.; Sadat-Shirazi, M.-S.; Zarrindast, M.-R. Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript (CART): A Multifaceted Neuropeptide. Peptides 2018, 110, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Chan, S.W.; Jiang, B.; Cui, D.; Sakata, I.; Sakai, T.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.Y.H.; Chan, T.W.D.; Rudd, J.A. Action of Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript (CART) Peptide to Attenuate Cisplatin-Induced Emesis in Suncus Murinus (House Musk Shrew). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 984, 177072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owe-Larsson, M.; Pawłasek, J.; Piecha, T.; Sztokfisz-Ignasiak, A.; Pater, M.; Janiuk, I.R. The Role of Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript (CART) in Cancer: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Kim, H.-C.; Oh, S.; Lee, Y.-M.; Hu, Z.; Oh, K.-W. Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript (CART) Peptide Plays Critical Role in Psychostimulant-Induced Depression. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, D.J.; O’Connor, D.P.; Laursen, H.; McGee, S.F.; McCarthy, S.; Zagozdzon, R. The Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript Mediates Ligand-Independent Activation of ERα, and Is an Independent Prognostic Factor in Node-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncogene 2012, 31, 3483–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, C. 30 Years of Dynorphins-New Insights on Their Functions in Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Pharmacol. AMP Ther. 2009, 123, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, B.; Yang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhou, S. Dynorphin B Induces Mitochondrial Fragmentation in NSCLC through the PKD/DRP-1 Signaling Pathway. Neuropeptides 2025, 112, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, H.U.; Conroy, W.G.; Isom, G.E.; Malven, P.V.; Yim, G.K.W. Presence of Dynorphin-like Immunoreactivity but Not Opiate Binding in Walker-256 Tumors. Life Sci. 1985, 37, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ma, Z.; Lei, Y. The Expression of Kappa-Opioid Receptor Promotes the Migration of Breast Cancer Cells in Vitro. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021, 21, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Hu, X.; Bennett, S.; Charlesworth, O.; Qin, S.; Mai, Y.; Dou, H.; Xu, J. Galanin Family Peptides: Molecular Structure, Expression and Roles in the Neuroendocrine Axis and in the Spinal Cord. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1019943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormandy, C.J.; Lee, C.S.; Ormandy, H.F.; Fantl, V.; Shine, J. Amplification, Expression, and Steroid Regulation of the Preprogalanin Gene in Human Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 1998, 28, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, I.; Kofler, B. The Galanin System in Cancer. In Galanin; Hökfelt, T., Ed.; Experientia Supplementum; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 102, pp. 223–241. ISBN 978-3-0346-0227-3. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Hu, J.; Fan, B.; Zhang, S.; Chang, K.; Mao, X.; Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Ma, L. Anti-Breast Cancer Activity of a Novel Genetically Engineered Fusion Protein Composed of HER2 Affibody and Proapoptotic Peptide R8-KLA. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahmani, T.; Sharifzadeh, S.; Tamaddon, G.H.; Farzadfard, E.; Zare, F.; Fadaie, M. Mitochondrial Targeted Peptide (KLAKLAK)2, and Its Synergistic Radiotherapy Effects on Apoptosis of Radio Resistant Human Monocytic Leukemia Cell Line. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 2019, 11, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, S.; Firoozpour, L.; Davoodi, J. The Synergistic Effect of Chimeras Consisting of N-Terminal Smac and Modified KLA Peptides in Inducing Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 655, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abnous, K.; Danesh, N.M.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M.; Bahreyni, A.; Lavaee, P.; Moosavian, S.A.; Taghdisi, S.M. A Smart ATP-Responsive Chemotherapy Drug-Free Delivery System Using a DNA Nanostructure for Synergistic Treatment of Breast Cancer in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Drug Target. 2020, 28, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Hu, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y. Coadministration of Kla Peptide with HPRP-A1 to Enhance Anticancer Activity. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Long, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Miao, F.; Shen, Y.; Pan, N. Enhanced Antitumor Effects of the BRBP1 Compound Peptide BRBP1-TAT-KLA on Human Brain Metastatic Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, D.; Wu, R.; Shi, H.; Zhu, T.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Hybrid Anticancer Peptide Synergistically Improving Cancer Cell Uptake and Inducing Apoptosis Mediated by Membrane Fusion. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 2708–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Biswas, S.; Li, Y.; Sooranna, S.R. The Emerging Roles of LINC00511 in Breast Cancer Development and Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1429262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Zhao, L.; Huang, S.; Jiang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Wu, J.L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Small Peptide LINC00511-133aa Encoded by LINC00511 Regulates Breast Cancer Cell Invasion and Stemness through the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Mol. Cell. Probes 2023, 69, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rady, I.; Siddiqui, I.A.; Rady, M.; Mukhtar, H. Melittin, a Major Peptide Component of Bee Venom, and Its Conjugates in Cancer Therapy. Cancer Lett. 2017, 402, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir Hassani, Z.; Nabiuni, M.; Parivar, K.; Abdirad, S.; Karimzadeh, L. Melittin Inhibits the Expression of Key Genes Involved in Tumor Microenvironment Formation by Suppressing HIF-1α Signaling in Breast Cancer Cells. Med. Oncol. 2021, 38, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachlioti, E.; Ferikoglou, S.; Georgiou, X.; Karampatsis, V.; Afratis, K. Development of a Multigram Synthesis of the Bradykinin Receptor 2 Agonist FR-190997 and Analogs Thereof. Arch. Pharm. 2023, 356, 2200610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, M.D.; Fraser, S.; Boer, J.C.; Plebanski, M.; De Courten, B.; Apostolopoulos, V. Anti-Cancer Effects of Carnosine—A Dipeptide Molecule. Molecules 2021, 26, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.M.; Haratipour, P.; Lingeman, R.G.; Perry, J.J.P.; Gu, L.; Hickey, R.J.; Malkas, L.H. Novel Peptide Therapeutic Approaches for Cancer Treatment. Cells 2021, 10, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandekar, K.R.; Satapathy, S.; Dharmashaktu, Y.; Ballal, S.; Ranjan, P.; Batra, A.; Gogia, A.; Mathur, S.; Bal, C. Somatostatin Receptor-Targeted Theranostics in Patients with Estrogen Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer—A Prospective Exploratory Study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 211, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvvula, P.K.; Moon, A.M. Discovery and Characterization of Anti-Cancer Peptides from a Random Peptide Library. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0293072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ramírez, J.M.; Carmona, C.; Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Extracting Knowledge from Machine Learning Models to Diagnose Breast Cancer. Life 2025, 15, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, F.; Esser, A.K.; Egbulefu, C.; Karmakar, P.; Su, X.; Allen, J.S.; Xu, Y.; Davis, J.L.; Gabay, A.; Xiang, J.; et al. Transferrin Receptor in Primary and Metastatic Breast Cancer: Evaluation of Expression and Experimental Modulation to Improve Molecular Targeting. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, D.; Dey, S.K.; Manna, S.; Das Chaudhuri, A.; Mahata, R.; Pradhan, A.; Roy, T.; Jana, K.; Das, S.; Roy, S.; et al. Nanoconjugate Carrying pH-Responsive Transferrin Receptor-Targeted Hesperetin Triggers Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Death through Oxidative Attack and Assemblage of Pro-Apoptotic Proteins. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 7556–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, P.N.; Vahidfar, N.; Tohidkia, M.R.; Hamidi, A.A.; Omidi, Y.; Aghanejad, A. Mucin-1 Conjugated Polyamidoamine-Based Nanoparticles for Image-Guided Delivery of Gefitinib to Breast Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 174, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, V.J.; Wu, S.; Gottumukkala, V.; Coelho, R.; Palmer, K.; Nair, S.; Erick, T.; Puri, R.; Ilovich, O.; Mukherjee, P. Preclinical Evaluation of an111 In/225 Ac Theranostic Targeting Transformed MUC1 for Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6946–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Wuest, M.; Richter, S.; Bergman, C.; Dufour, J.; Krys, D.; Simone, J.; Jans, H.-S.; Riauka, T.; Wuest, F. A Comparative PET Imaging Study of 44gSc- and 68Ga-Labeled Bombesin Antagonist BBN2 Derivatives in Breast and Prostate Cancer Models. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2020, 90–91, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okarvi, S.M.; Al-Jammaz, I. Synthesis, Radiolabeling, and Preclinical Evaluation of 68Ga/177 Lu-Labeled Leuprolide Peptide Analog for the Detection of Breast Cancer. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2022, 37, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Oncogenic and Anticancer Peptides | ||

|---|---|---|

| Peptides | Actions | |

| Oncogenic | Anticancer | |

| Adrenomedullin | - Accelerated bone metastasis [18] - Fibroblasts release AM, promoting angiogenesis and tumor growth [19] | - Blocked cell invasion and metastasis [17] |

| Angiotensin II | - Angiotensin II receptor 1 overexpression favored angiogenesis and tumor growth [9] | - Decreased cell motility [28] |

| Bradykinin | - Facilitated migration and invasion; both effects blocked with kinin B1 and B2 receptor antagonists (Des-[Arg9]-Leu8-bradykinin, HOE-140) [38] - Bradykinin analogs promoted cell proliferation and metalloproteinase 2/9 release, favoring invasion and metastasis [41,42] - BC cell stimulation with kinin B1 receptor agonists increased peptidase KLK6/KLK11 levels (favoring invasiveness and proliferation) and decreased KLK10 (protease related to growth suppression) level [41] - Kinin receptor B1 antagonists cooperated with chemotherapeutic drugs (paclitaxel, doxorubicin) to favor the death of triple-negative BC cells [40] | - Kinin receptor B2 agonists (FR190,997) exerted antiproliferative effects [39] |

| Corticotropin-releasing factor | - CRF receptor 2 mediated cell migration [51] - Mediated cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis and regulated the immune response [57] - Favored cell motility and invasiveness, blocked apoptosis, augmented FAK phosphorylation and actin polymerization and promoted the synthesis of prostaglandins, favoring metastasis [54] | - Inhibited cell growth [55] and migration [60] - Tumor suppressor [60] - Decreased tumor volume without affecting angiogenesis and increased chemotherapy action [61] - CRF and urocortin 2 promoted apoptosis [52] |