Simple Summary

This study provides physicians’ perspectives on the information cancer patients with autoimmune diseases should learn when considering ICI. This information can be incorporated into patient–doctor discussions and educational tools to improve shared decision-making in this patient population.

Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have improved cancer outcomes but can cause severe immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and flares of autoimmune conditions in cancer patients with pre-existing autoimmune disease. The objective of this study was to identify the information physicians perceived as most useful for these patients when discussing treatment initiation with ICIs. Twenty physicians at a cancer institution with experience in the treatment of irAEs were interviewed. Qualitative thematic analysis was performed to organize and interpret data. The physicians were 11 medical oncologists and 9 non-oncology specialists. The following themes were identified: (1) current methods used by physicians to provide information to patients and delivery options; (2) factors to make decisions about whether or not to start ICIs in patients who have cancer and pre-existing autoimmune conditions; (3) learning points for patients to understand; (4) preferences for the delivery of ICI information; and (5) barriers to the implementation of ICI information in clinics. Regarding points to discuss with patients, physicians agreed that the benefits of ICIs, the probability of irAEs, and risks of underlying autoimmune condition flares with the use of ICIs were most important. Non-oncologists were additionally concerned about how ICIs affect the autoimmune disease (e.g., impact on disease activity, need for changes in medications for the autoimmune disease, and monitoring of autoimmune conditions).

1. Introduction

The American Autoimmune Association has described more than 100 recognized autoimmune diseases [1]. More than 15% of the U.S. population suffers from autoimmune disorders (~50 million individuals, or one in five) [2,3,4]. Autoimmune diseases cause chronic inflammation that can alter DNA repair pathways [5]. Subsequently, DNA damage results in enhanced mutation frequency, cancer, and cell death [6]. Additionally, certain autoimmune disease treatments have been associated with increased cancer risk. A literature review revealed significant associations between more than 20 different autoimmune and chronic inflammatory autoimmune-related diseases with cancer [7].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been dramatically successful in treating various advanced solid tumors, including melanoma, lung cancer, and kidney cancer [8,9,10,11]. For cancer patients with autoimmune diseases, checkpoint inhibition is possible but requires careful monitoring because they are at higher risk for immune-related adverse events (irAEs) than cancer patients without autoimmune diseases [12,13]. Cancer patients with autoimmune diseases must make decisions about receiving ICIs with respect to potential survival benefits versus the risk of adverse events and autoimmune condition flares. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to identify the types of educational content perceived by physicians as most useful for cancer patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases who are candidates to receive ICIs as well as the preferred delivery method for this content. Our findings provide key learning points for incorporation into patient–doctor discussions and educational tools.

2. Methods

The results of this study are reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research [14].

2.1. Qualitative Approach and Research Paradigm

We used grounded theory methods to inductively identify and classify the information perceived by physicians to be of relevance for educational content. Our analytical methods were aligned with a social constructivist approach [15] because the physicians’ knowledge about the most relevant educational content was believed to be obtained through their interactions with their patients and their own work-related environment and experiences [16].

2.2. Researcher Characteristics and Reflexivity

Discussions with the physicians were led by an investigator with experience in cognitive interviews (M.A.L.-O.). The research team comprised clinical researchers with expertise in qualitative research (N.H., R.J.V., M.E.S.-A., M.A.L.-O.), knowledge synthesis (M.A.L.-O., M.E.S.-A., J.I.R.), patient education (R.J.V., M.E.S.-A., M.A.L.-O.), internal medicine (J.I.R.), rheumatology (M.E.S.-A., C.O.B., C.C.), and oncology (M.A., H.T., A.D.), with doctorate-level training in these areas.

2.3. Context and Sampling Strategy

We used convenience sampling and invited to participate all melanoma oncologists and thoracic/head and neck medical oncologists who had prescribed or were considering ICIs for their patients at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and physicians in the departments of rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology who had cared for or evaluated patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases who were considering ICIs use. The size of the sample was largely determined by the availability of respondents and based on our previous research. We estimated that the recruitment of 15 to 20 physicians would achieve data saturation and allow us to fully explore in-depth each physician’s account [17,18].

2.4. Ethical Issues Pertaining to Human Subjects

This study was approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board (protocol #2020-0035). A consent statement was provided to physicians, and any questions concerning the study were answered. Institutional standard procedures were followed to address data security issues.

2.5. Data Collection Methods

Eligible physicians were invited to participate with an email. The interviewer (M.A.L.-O.) had previous professional relationships (research collaboration) with three rheumatology physicians. The interviewer emailed each physician the day before each interview to remind them of the interview date and time and summarized the questions that would be asked. Participating physicians could opt to be interviewed in their clinics, on Zoom, or in their offices at the most convenient time from August to November 2021. Physicians who chose Zoom could turn their video off. Each session lasted about 45 min, and the audio was recorded.

2.6. Data Collection Instruments and Technologies

A semi-structured interview guide was created by the study authors (Supplementary Table S1). M.A.L.-O., developed the first draft of the guide and received feedback from the rest of the study team. Two pilot interviews were conducted to assess the interview length, check the flow, and confirm that the content accurately addressed the research questions. During the study interviews, our goal was to gain insight into the problems patients and providers experience when making treatment decisions. Our hope was that the data obtained would elucidate the approaches to decision-making physicians use for patients with autoimmune diseases and cancer and provide the most appropriate learning content to be delivered.

Information on the physicians’ sex, ethnicity, specialty, years of practice, and percent of time in the clinic was obtained using REDCap. We also asked how many of their patients receive ICIs per month on average and how confident they felt in managing patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases who receive ICIs.

2.7. Data Processing

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim using Adept Word Management (Houston, TX, USA). Transcripts were anonymized using identification codes. A research team member reviewed each interview and confirmed the transcript accuracy. Audio files were stored on a secured drive under an institutional server accessible by the research team only. Transcripts were then transferred to the web application Dedoose to code and analyze the data [19].

2.8. Data Analysis

A previously reported approach to thematic analysis was used [20]. Initial data familiarization was completed by M.A.L.-O. Next, independent coding of the transcripts was performed by 3 researchers (M.A.L.-O., J.I.R., G.F.D.). The transcripts were analyzed with a combination approach of deductive and inductive coding to list categories and subcategories of the data units (i.e., physicians’ statements and quotes for each question asked) according to the guiding questions to ensure our research objectives were met. M.A.L.-O. created a thematic map and checked themes against the data set before applying the themes’ meanings to the research question. A preliminary report included the identification and definition of themes (i.e., main categories of data) and subthemes (i.e., subcategories) emerging from the analysis. Saturation was considered when no new information was obtained from the data collected [21,22].

2.9. Techniques to Enhance Trustworthiness

To ensure study rigor and trustworthiness, the data were coded by different researchers. Interviews were listened to and compared against their transcripts. Three physicians were selected for a non-causal random institutional audit, and all standards for research without bias were met.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

We invited 24 physicians, but only 20 participated. Two-thirds were women. Six physicians were melanoma oncologists (30%), five were thoracic/head and neck medical oncologists (25%), four were rheumatologists (20%), three were dermatologists (15%), and two were gastroenterologists (10%). The years of practice ranged from 2 to 27. The average number of patients receiving ICIs seen per month ranged from 10 to 80. Most physicians felt confident in managing cancer patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases receiving ICI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants (n = 20).

3.2. Synthesis and Interpretation of the Data

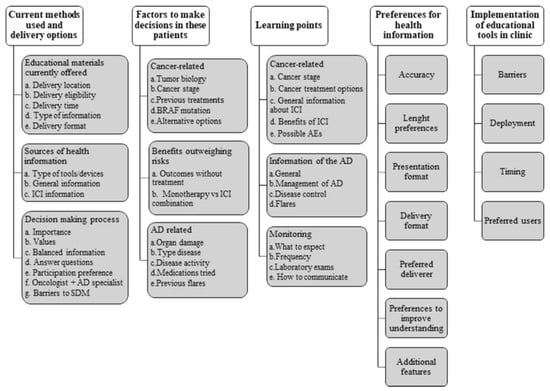

We identified five themes from the interviews that aligned with our research objectives: current information provided, methods used, and delivery options; factors considered when making treatment decisions; key information to share with patients during patient–doctor discussions; preferences for optimal delivery of health information on ICIs for patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases; and factors perceived as obstacles to and facilitators of the use of an educational tool or decision aid in this context (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Themes and their subthemes identified in the physicians’ interviews. AD, autoimmune disease; AEs, adverse events; SDM, shared decision-making; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors.

3.2.1. Current Information Provided (Methods Used and Delivery Options)

This theme had three subthemes: educational materials, perceived sources of health information used by patients, and factors involved in decision-making. Table 2 shows example quotes for salient subthemes.

Table 2.

Example of quotes for salient subthemes.

- First, most physicians reported delivering information to patients in the examining room but not at every visit. All physicians expressed being unaware of any currently available materials specifically developed for patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases. The available materials that physicians were aware of contain concise generic information about immune checkpoints inhibitors for all cancer patients. These materials are provided in-person by anyone available (in most cases, either the staff member obtaining patient consent for treatment or the physician) when patients consent to initiate therapy, and some patients receive pamphlets after discussions with their oncologists. Materials provided most often include handouts on drugs, materials developed in-house (by the institution), or materials offered by medical societies or organizations. Two physicians preferred drawing pictures of the information discussed with patients. Non-oncology specialists preferred to first learn about what was discussed with the oncologist to supplement the information already provided and more specifically address patients’ educational needs in the context of autoimmune disease. Most preferred to deliver information verbally and then send it through the electronic health record system (note with a summary of the discussion) for patients to review.

- For the perceived sources of health information used by patients, most physicians stated that most of their patients use electronic tools/devices to obtain health information, with Google and social media sites as the most common sources. Other common sources of information were the patients’ support groups (relatives, caregivers, friends, etc.) and cancer- and/or disease-specific societies.

- For the factors involved in decision-making, physicians described the methods used during decision-making for patients who are candidates to receive ICIs and are diagnosed with pre-existing autoimmune diseases. They said that shared decision-making is important to avoid decisional regret and emphasized first considering the patient’s values. All physicians also stressed the importance of presenting balanced information about benefits and risks, ensuring patients correctly interpret information, answering any questions (during or after the encounter), and accounting for patient preferences when making treatment decisions. In addition, most expressed the need to consider the decisions of patients’ support group members (e.g., family, caregivers, close friends) when patients want their involvement. Non-oncologists also mentioned the need for close communication with oncologists to facilitate decision-making and monitoring. Physicians listed several concerns regarding the decision-making process in this population. Shared decision-making was thought to require additional clinical personnel. Some participants thought patients may have anxiety when presented with the probability of flares or irAEs. Others mentioned insufficient time to cover all components of shared decision-making in visits, inability to complete a detailed electronic health record note summarizing the shared decision-making visit, and not having time to answer all questions or contact all interested parties in cases where the patient has a large support system.

3.2.2. Factors to Make Treatment Decisions in These Patients

This theme also had three subthemes: factors associated with cancer, ensuring that treatment benefits outweigh the risks, and factors associated with autoimmune diseases.

- First, the cancer-associated factors to make treatment decisions in these patients were tumor biology (i.e., how effective ICIs are anticipated to be), cancer stage (i.e., metastatic or not), previous cancer treatments, availability of targeted therapies, and other alternative options.

- The second subtheme consisted of contemplating the consequences of autoimmune toxicity in the context of the survival benefit expected while considering the patient’s needs. Another item within this subtheme was the decision to use one ICI versus combination therapy owing to the higher probability of adverse events with a combination. Physicians reported accounting for patient frailty, autoimmune disease severity, and the specific effect of targeted inhibitors on different autoimmune diseases.

- Regarding autoimmune disease, physicians mentioned considering the type, disease activity, number of medications used for it, severity of previous flares, and organ damage.

3.2.3. Key Information to Share with Patients

Information regarding cancer and ICIs was the first subtheme in this theme.

- The key points suggested were information on cancer stage, cancer treatment options, general information, and specific information about ICIs (i.e., mechanism of action, benefits/response rates/cancer progression, and probability of adverse events). Regarding possible adverse events, oncologists emphasized the probability of fatalities, symptoms to be aware of, the possibility of quality of life being affected or the need for hospice care, and the potential for pause or discontinuation of the ICI administration.

- Autoimmune disease information was the second subtheme. The key learning points centered on providing general information about the autoimmune disease (natural history of the patient’s autoimmune disease, emphasis on how patients differ), general management of the autoimmune disease, the importance of disease control (including steroid use), and risk of flares of autoimmune conditions with ICIs. Specifically, non-oncologists centered on how ICIs may affect the outcome of autoimmune disease: (1) impact on disease activity, (2) changes in medications for an autoimmune disease, (3) probability of flares of autoimmune conditions, (4) available treatment options for flares, (5) other possible irAEs, (6) symptoms requiring immediate attention, (7) follow-up and monitoring of autoimmune conditions, (8) good sources of information other than asking doctors, and (9) potential influence of steroids on tumor response to ICIs.

- The third subtheme was information about monitoring. Physicians emphasized the need to provide information on what to expect during and after treatment with ICIs, the expected frequency of visits to autoimmune disease physicians (preferred in-person), the importance of frequent laboratory exams, and maintaining close contact with providers, especially during the first three cycles of ICI administration.

3.2.4. Preferences for Optimal Delivery of Health Information

All physicians expressed the need for an educational tool that can help patients be more aware of the factors when making treatment decisions and provide precise estimates of the benefits and risks of ICIs for those with pre-existing autoimmune diseases. Crucial requirements, as noted by nine physicians, were accuracy, simplicity (information should be presented concisely and graphically), and fixed information (as opposed to individualized or non-linear information).

Requirements also mentioned included multiple delivery formats (e.g., electronic medical record portal (MyChart) (with the possibility to add attachments), paper, videos (delivered by doctors or nurses), and websites (interaction with patients responding to questions)) with features for improving understanding (e.g., interaction with images, graphs, and tables), avoiding language barriers, accounting for literacy levels, and presenting basic information initially, with the possibility of selecting more in-depth information if desired to avoid overwhelming patients. Additional features suggested to improve comprehension of the information and facilitate decision-making were vignettes of patient–doctor conversations, patient stories, and online peer support groups (or possibly social media). Not all physicians favored including a risk calculator to provide personalized probabilities of adverse events because of validity concerns, the potential for patient misinterpretation of the probabilities, and uncertainty about the most appropriate outcomes to include. However, physicians who did favor this suggested creating a separate website to make a risk calculator available for physicians, mid-level providers, and trainees before encounters with patients.

3.2.5. Preferences for Optimal Delivery of Health Information

Physicians mentioned the following barriers to using an educational tool in the clinic: the need for dissemination to make people aware and remind them that there is a tool available, the potential increase in consult time, and the possibility of over-alerting patients.

Most physicians suggested deploying tools in a format that will allow for maintaining their current workflows and ensuring the tools can be accessed within the electronic health record system or a separate website before, during, and after patient–doctor encounters. Few solutions to provide information while facilitating workflow were mentioned and included providing access to the information before the visit to let patients bring questions for the encounter with their doctors, letting a nurse discuss the information, use it only to determine patient preferences (patient averse to significant toxicities or bedridden and wants to be part of all treatment decisions, etc.), or to provide after-care or after-discussion summaries.

4. Discussion

We learned that educational materials specifically developed to meet the learning needs of cancer patients with underlying autoimmune diseases who are considering ICIs are lacking. Therefore, our study can serve as a comprehensive catalog of relevant information and delivery formats that, according to physicians, can facilitate decision-making for patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases who are candidates to receive ICIs. Three main elements must be considered and understood by patients when discussing ICI initiation: cancer-associated characteristics that inform the probability of success/survival, autoimmune disease-associated characteristics that inform the probability of irAEs/flares, and the consequences of any potential treatment-related harms that may affect the patient’s quality of life.

To the best of our knowledge, the literature contains no studies exploring the most important educational topics about ICIs for patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases according to physicians who treat these diseases. Previous qualitative and mixed methods studies focused on the perceptions of patients with specific types of cancer without pre-existing autoimmune diseases receiving ICIs or the needs of patients with irAEs [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

A qualitative study by Fraterman et al. identified what patients should expect in regard to health information and technology applications [23]. In contrast with our physicians’ preference for a more generic approach to providing information, Fraterman and colleagues reported that inability to personalize educational tools and notifications was a barrier to patients’ use of technology applications. Furthermore, the key topics raised by patients in that study were similar to those raised by the physicians in our study, including clinical management and available supportive care services. However, a topic relevant to patients not mentioned by the physicians in our study was related to what patients can do to support their physical and mental well-being and symptom monitoring using mobile applications to facilitate patient–doctor communication and help patients feel more secure [23].

Another qualitative study reported the experiences of cancer survivors and their care needs after receiving ICIs [24]. In that study, patients also emphasized the need for more tailored health information, and similar to what we observed, they wanted information about how and when to communicate with their providers. Cappelli et al. also explored the needs of people with inflammatory arthritis induced by ICIs [27]. They highlighted the impact of irAEs in different domains of cancer patients’ quality of life and how these events influence the patients’ decision-making regarding the continuation of treatment. This aligns with the physicians’ statements in our study indicating that they discuss preferences about quality of life and ultimate treatment goals to avoid decisional regret with their patients. Researchers in two mixed methods studies also reported on this topic. One from Germany highlighted the need to increase patients’ general knowledge about ICIs and to increase risk awareness given that most patients perceived adverse events to be significantly less severe than those of other therapies [25]. A study from the United Kingdom also suggested creating content emphasizing the variability among patients when covering information about adverse events [26].

One qualitative study gathered physicians’ perspectives on emerging treatments for locally advanced unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma [35]. The authors explored the factors that influence providers’ treatment recommendations. Like our findings, they observed that decision-making was influenced by the patient’s characteristics and comorbidities, tumor biology, and goals and preferences for treatment. It is important to note that the physicians also expressed the need for more general (as opposed to tailored) education, demonstrating potential discordance between patients’ and physicians’ perspectives regarding learning needs that can facilitate decision-making in the context of ICIs use.

The last theme explored the potential barriers to using educational material in the clinic with the potential increase in consult time being the one most mentioned. Most agreed that developing an educational tool for this population would be important, but few physicians provided solutions for implementing such a tool. Other studies have evaluated barriers and facilitators of educational tools in other medical contexts and, contrasting with our results, solutions provided include increasing the interest of physicians in the use of the tool, forming alliances between clinicians and researchers, and offering training in the use of the tool [36,37,38].

Our study has some limitations. Our findings are derived from interviews with physicians at a single U.S. comprehensive cancer center. Relevant elements identified for the development of educational tools may differ in other centers or countries. Furthermore, the physicians in our study may have had an interest in the development of educational tools. We did not explore potential barriers to health care such as insufficient or lack of health insurance, which could be another determining factor when making decisions for these patients, as patients seen at our institution for the most part are insured. Lack of health insurance coverage has been associated with poor receipt of cancer care in the U.S. [39]. Although we included physicians more likely to see patients with common autoimmune diseases who may receive ICI, such as inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, or rheumatoid arthritis, not all subspecialties could be represented. Providers in subspecialties not included in our study may have different perceptions about the key learning points or requirements for educational tools for their patients. Nonetheless, given that we used a semi-structured interview including open-ended questions and reached saturation after 13 providers, additional interviews would likely not change our conclusions. Furthermore, the investigators’ observations, intentions, and prejudices may have influenced the results. We tried to minimize this by avoiding any previous assumptions when analyzing the data and primarily using the natural language used by the physicians interviewed. Finally, we dealt with learning needs from the physicians’ perspective, and examining the views and opinions of patients in a similar qualitative study is necessary.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings have implications for the development and implementation of educational tools aimed at cancer patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases considering treatment with ICIs. Our qualitative study provides important new information from the physicians’ perspectives on the information cancer patients with autoimmune diseases considering this treatment must learn. In this work, we gained insight into the current methods used to inform these patients and how the information is delivered, the factors that physicians consider when making treatment decisions regarding ICIs for these patients, the physicians’ most important learning points for developing educational content that can facilitate shared decision-making in this context, preferred methods of delivery of educational content in the clinic, and potential barriers to and facilitators for implementation. The next step after obtaining patients’ preferences for content and optimal ways to deliver it is to develop an educational tool incorporating our results. Our findings can also be used in patient–doctor discussions to improve shared decision-making in this patient population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers15102690/s1, Table S1: Semi-structured interview used.

Author Contributions

M.A.L.-O.: conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; G.F.D.: data curation, writing—reviewing and editing; J.I.R.: writing—reviewing and editing; M.A.: writing—reviewing and editing; H.T.: writing—reviewing and editing, validation; A.D.: writing—reviewing and editing; C.O.B.III: writing—reviewing and editing; C.C.: writing—reviewing and editing: N.I.H.: methodology, writing—reviewing and editing; R.J.V.: methodology, writing—reviewing and editing; M.E.S.-A.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute (Project number: CA237619), The University of Texas MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant funded from NIH/NCI under award number P30CA016672 (using the Shared Decision Making Core), and the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (protocol #2020-0035; date of approval: 23 January 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.A.L.-O., upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented in conference abstracts at the 2022 European League Against Rheumatism and American College of Rheumatology Convergence [40,41]. Editorial support was provided by Don Norwood of MD Anderson Editing Services, Research Medical Library. We also would like to thank Hollie Darnell from the Community Health Program at Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, for her coding contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

A.M.: research funding from Genentech, Nektar Therapeutics, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Jounce Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Adaptimmune, Shattuck Lab, and Gilead; consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Shattuck Lab, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, AstraZeneca, Nektar Therapeutics, Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer, Nanobiotix-MDA alliance, and Hengenix. H.A.T.: research funding from GlaxoSmithKline; research funding and consulting honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Merck, and Novartis; consulting fees from Boxer, Eisai, Iovance, Karyopharm, and Pfizer. A.D.: research funding from Apexigen, Idera Phamaceuticals, and Nektar Therapeutics; consulting fees from Apexigen, Idera Phamaceuticals, Memgen, Nektar Therapeutics, and Pfizer. The other authors declare no competing interest in the submitted work.

References

- Autoimmune Association. Autoimmune Disease List. 2023. Available online: https://autoimmune.org/disease-information/ (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Lerner, A.; Jeremias, P.; Matthias, T. The World Incidence and Prevalence of Autoimmune Diseases is Increasing. Int. J. Celiac Dis. 2015, 3, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, M.A.; Hogan, S.L. Environmental epidemiology and risk factors for autoimmune disease. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2003, 15, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, G.S.; Bynum, M.L.; Somers, E.C. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: Improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J. Autoimmun. 2009, 33, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, J.; Thadhani, E.; Samson, L.; Engelward, B. Inflammation-induced DNA damage, mutations and cancer. DNA Repair Amst. 2019, 83, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Zhou, P.-K. DNA damage repair: Historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franks, A.L.; Slansky, J.E. Multiple Associations Between a Broad Spectrum of Autoimmune Diseases, Chronic Inflammatory Diseases and Cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2012, 32, 1119–1136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.; Reckamp, K.L.; Baas, P.; Crino, L.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Poddubskaya, E.; Antonia, S.; Pluzanski, A.; Vokes, E.E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Steins, M.; Ready, N.E.; Chow, L.Q.; Vokes, E.E.; Felip, E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; George, S.; Hammers, H.J.; Srinivas, S.; Tykodi, S.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Procopio, G.; Plimack, E.R.; et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akturk, H.K.; Alkanani, A.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, L.; Michels, A.W. PD-1 Inhibitor Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients with Preexisting Endocrine Autoimmunity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3589–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michailidou, D.; Khaki, A.R.; Morelli, M.P.; Diamantopoulos, L.; Singh, N.; Grivas, P. Association of blood biomarkers and autoimmunity with immune related adverse events in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded Theory: Methodology and Theory Construction. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 6396–6399. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, S.B. Sample size and grounded theory. JOAAG 2010, 5, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose Version 7.0.23. Web application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data; Socio Cultural Research Consultants, LLC.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/ (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. In Qualitative Psychology; Smith, J.A., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; pp. 222–248. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraterman, I.; Glaser, S.L.C.; Wilgenhof, S.; Medlock, S.K.; Mallo, H.A.; Cornet, R.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Boekhout, A.H. Exploring supportive care and information needs through a proposed eHealth application among melanoma patients undergoing systemic therapy: A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7249–7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamminga, N.C.W.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Joosen, M.C.W.; de Joode, K.; Joosse, A.; Grunhagen, D.J.; Nijsten, T.E.; Wakkee, M.; Lugtenberg, M. Experiences of resuming life after immunotherapy and associated survivorship care needs: A qualitative study among patients with metastatic melanoma. Br. J. Derm. 2022, 187, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrig, A.; Richter, J.; Grullich, C.; Apostolidis, L.; Horak, P.; Villalobos, M.; Grapp, M.; Friederich, H.-C.; Maatouk, I. Patient expectations are better for immunotherapy than traditional chemotherapy for cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 3189–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L.; Forster, M.D.; Zaki, K.; Mithra, S.; Alli, H.; O’Connor, A.; Patel, A.; Wong, I.C.K.; Chambers, P. Immunotherapy and associated immune-related adverse events at a large UK centre: A mixed methods study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelli, L.C.; Grieb, S.M.; Shah, A.A.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Orbai, A.M. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis: A qualitative study identifying unmet patient needs and care gaps. BMC Rheumatol. 2020, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.; Marrel, A.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Burgess, M.A.; Chmielowski, B.; Fazio, N.; Gambichler, T.; Grob, J.-J.; Lebbé, C.; Robert, C.; et al. Patient Experiences with Avelumab in Treatment-Naive Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Longitudinal Qualitative Interview Findings from JAVELIN Merkel 200, a Registrational Clinical Trial. Patient 2020, 13, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ala-Leppilampi, K.; Baker, N.A.; McKillop, C.; Butler, M.O.; Siu, L.L.; Spreafico, A.; Razak, A.R.A.; Joshua, A.M.; Hogg, D.; Bedard, P.L.; et al. Cancer patients’ experiences with immune checkpoint modulators: A qualitative study. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 3015–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, R.; Shaw, J.W.; Korn, A.; McAuliffe, J. The value of immunotherapy for survivors of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: Patient perspectives on quality of life. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Billett, A.; Milne, D. Balancing the Hype with Reality: What Do Patients with Advanced Melanoma Consider When Making the Decision to Have Immunotherapy? Oncologist 2019, 24, e1190–e1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenehjem, D.D.; Au, T.H.; Ngorsuraches, S.; Ma, J.; Bauer, H.; Wanishayakorn, T.; Nelson, R.S.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Schwartz, J.; Korytowsky, B.; et al. Immunotargeted therapy in melanoma: Patient, provider preferences, and willingness to pay at an academic cancer center. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Dhillon, H.M.; Lomax, A.; Marthick, M.; McNeil, C.; Kao, S.; Lacey, J. Certainty within uncertainty: A qualitative study of the experience of metastatic melanoma patients undergoing pembrolizumab immunotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1845–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuk, E.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Luke, J.; Postow, M.A.; Callahan, M.; Harding, J.J.; Roth, K.G.; Flavin, M.; Granobles, A.; Christian, J.; et al. Patient perspectives on ipilimumab across the melanoma treatment trajectory. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2155–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivas, P.; Huber, C.; Pawar, V.; Roach, M.; May, S.G.; Desai, I.; Chang, J.; Bharmal, M. Management of Patients with Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma in an Evolving Treatment Landscape: A Qualitative Study of Provider Perspectives of First-Line Therapies. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2022, 20, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najem, C.; Wijma, A.J.; Meeus, M.; Cagnie, B.; Ayoubi, F.; Van Oosterwijck, J.; De Meulemeester, K.; Van Wilgen, C.P. Facilitators and barriers to the implementation of pain neuroscience education in the current Lebanese physical therapist health care approach: A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; He, F.J.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Luo, R.; Guo, C.; Zhang, P. Process Evaluation of an Application-Based Salt Reduction Intervention in School Children and Their Families (AppSalt) in China: A Mixed-Methods Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 744881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsma-Bakker, A.; van Leeuwen, R. An Online Competency-Based Spiritual Care Education Tool for Oncology Nurses. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 37, 151210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelblatt, J.S.; Yabroff, K.R.; Kerner, J.F. Equitable access to cancer services: A review of barriers to quality care. Cancer 1999, 86, 2378–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Olivo, M.A.; Ruiz, J.I.; Duhon, G.; Altan, M.; Tawbi, H.; Diab, A.; Bingham, C.O.; Calabrese, C.; Volk, R.J.; Sua-rez-Almazor, M.E. Learning needs assessment for patients with cancer and a pre-existing autoimmune disease who are candidates to receive immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81 (Suppl. 1), 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Olivo, M.; Ruiz, J.; Duhon, G.; Tawbi, H.; Diab, A.; Bingham, I.I.I.C.; Calabrese, C.; Heredia, N.; Volk, R.; Sua-rez-Almazor, M. Priority educational topics to deliver information about immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with cancer and a pre-existing autoimmune disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74 (Suppl. 9), 322–323. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).