Simple Summary

The use of multi-gene testing platforms to individualize treatment is rapidly expanding into routine oncology practice. UGT1A1, which encodes for the uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 enzyme, is commonly included on multi-gene molecular testing assays. UGT1A1 polymorphisms may influence drug-induced toxicities of numerous medications used in oncology. However, guidance for incorporating UGT1A1 results into therapeutic decision-making is sparse and can differ depending on the referenced resource. We summarize the literature describing associations between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and toxicity risk with irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, and nilotinib. Resources that provide recommendations for UGT1A1-guided drug prescribing are reviewed, and considerations for implementation into patient care are provided.

Abstract

Multi-gene assays often include UGT1A1 and, in certain instances, may report associated toxicity risks for irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, and nilotinib. However, guidance for incorporating UGT1A1 results into therapeutic decision-making is mostly lacking for these anticancer drugs. We summarized meta-analyses, genome-wide association studies, clinical trials, drug labels, and guidelines relating to the impact of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, or nilotinib toxicities. For irinotecan, UGT1A1*28 was significantly associated with neutropenia and diarrhea, particularly with doses ≥ 180 mg/m2, supporting the use of UGT1A1 to guide irinotecan prescribing. The drug label for belinostat recommends a reduced starting dose of 750 mg/m2 for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes, though published studies supporting this recommendation are sparse. There was a correlation between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and pazopanib-induced hepatotoxicity, though further studies are needed to elucidate the role of UGT1A1-guided pazopanib dose adjustments. Limited studies have investigated the association between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and nilotinib-induced hepatotoxicity, with data currently insufficient for UGT1A1-guided nilotinib dose adjustments.

Keywords:

UGT1A1; pharmacogenetics; irinotecan; pazopanib; nilotinib; belinostat; cancer; genotype; precision medicine; Gilbert’s syndrome 1. Introduction

Individualizing anticancer therapy based on genetic biomarkers is an essential component of precision oncology. There has been a rapid uptake of genetic testing to assist with the clinical management of cancer patients, due in part to strong evidence demonstrating associations between genetic polymorphisms and drug response. Inclusive are clinical data showing that certain germline polymorphisms can identify opportunities for targeted therapy, assist with mitigation of chemotherapy toxicity risks, and optimize supportive care pharmacotherapy [1,2,3,4,5]. Multi-gene pharmacogenetic panels or targeted next-generation sequencing platforms that provide somatic and germline information, rather than single-gene assays, are emerging as preferred genetic testing approaches in oncology. A limitation to multi-gene assays is that clinicians may be exposed to germline results where ambiguous recommendations exist for genotype-guided drug prescribing.

One such example is UGT1A1, which encodes for the uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 enzyme. UGT1A1 genetic variants can affect enzymatic function, causing reduced metabolic capacity. Dinucleotide repeats located in the gene’s promoter region are among the most frequently observed polymorphisms, with the UGT1A1*28 TA7 repeat occurring at a frequency of 0.09–0.41 in Asian populations, 0.26–0.32 in European populations, 0.37–0.4 in Latino populations, and 0.37–0.56 in African populations [6,7,8,9]. Dependent on ancestry, over 50% of individuals may harbor a UGT1A1 polymorphism that can decrease enzymatic activity [6,7,8]. Table 1 provides example UGT1A1 variants, their predicted impact on metabolic function, and phenotype frequencies among race and ethnic groups. A comprehensive overview of UGT1A1 polymorphisms, allele frequencies, and predicted enzymatic function is provided by the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), which publishes evidence-based, peer-reviewed guidelines for how to translate genetic test results into actionable prescribing decisions for affected drugs [6,10]. Individuals who are heterozygous for one decreased function allele (e.g., UGT1A1 *1/*28) are predicted to be intermediate metabolizers (IMs), and those who are carriers of two decreased function alleles (e.g., UGT1A1 *28/*28) are predicted to be poor metabolizers (PMs) (Table 1) [6]. For drugs that undergo UGT1A1-mediated glucuronidation as the major elimination pathway, such as irinotecan and belinostat, decreased UGT1A1 metabolic capacity caused by genetic variation may result in elevated drug concentrations that can increase the risk of drug-induced toxicities.

Table 1.

Example UGT1A1 alleles, predicted phenotype function, and frequencies among racial/ethic groups.

In addition to drug metabolism, UGT1A1 also has a role in bilirubin elimination. Individuals who are UGT1A1 PMs (e.g., UGT1A1 *28/*28, UGT1A1 *6/*6) may display mild hyperbilirubinemia, referred to as Gilbert’s syndrome [13]. However, cases have been published demonstrating that some UGT1A1 PMs may be asymptomatic [13,14]. Individuals with Gilbert’s syndrome are estimated to have only 25–30% of normal UGT1A1 activity [15]. In rare instances, UGT1A1 genetic variants can result in almost complete loss of UGT1A1 function leading to high levels of unconjugated bilirubin that cause severe and debilitating symptoms described as Crigler–Najjar syndrome [16,17]. Oncology agents, such as pazopanib and nilotinib, can also impair bilirubin elimination through inhibition of UGT1A1 function [18,19,20]. Prescribing drugs that inhibit UGT1A1 to patients carrying UGT1A1 loss of function alleles may increase the risk of hyperbilirubinemia and liver toxicity [21,22].

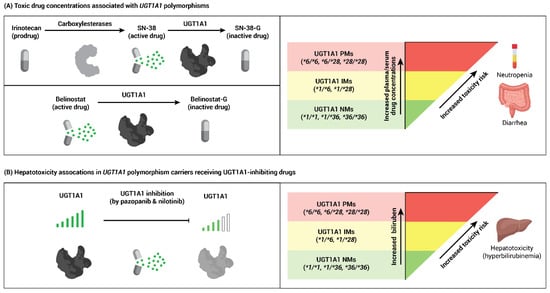

Studies have investigated the association between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and toxicity induced by irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, or nilotinib. UGT1A1 PMs, and potentially IMs, are proposed to be at an increased risk of diarrhea or hematologic toxicities due to elevated systemic exposure to irinotecan and belinostat (Figure 1A). Similarly, the inhibition of UGT1A1 by pazopanib or nilotinib has been reported to exacerbate hyperbilirubinemia in patients harboring UGT1A1 genetic polymorphisms (Figure 1B) [20,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Findings from prior studies have led to FDA-approved labeling that provides specific irinotecan and belinostat dosing recommendations based on UGT1A1 genetic test results and precautions for increased risk of pazopanib and nilotinib induced toxicities in those harboring UGT1A1 polymorphisms [23,34,35,36]. However, clinical guidance for integrating UGT1A1 results into cancer care are sparse and can be inconsistent. We reviewed the literature evaluating associations between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, or nilotinib toxicities along with applicability to patient care. Established resources for pharmacogenetic guidance were identified, and recommendations were evaluated for UGT1A1-guided therapy for irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, or nilotinib to elucidate further the role of UGT1A1 in guiding cancer pharmacotherapy.

Figure 1.

Association of UGT1A1 polymorphisms with toxicity from cancer drugs. (A) Irinotecan and belinostat are metabolized by UGT1A1. Intermediate (IM) or poor (PM) UGT1A1 metabolic activity may result in greater than expected exposure to SN-38 (the active drug metabolite of irinotecan) and belinostat, increasing the risk of neutropenia or diarrhea. (B) The tyrosine kinase inhibitors pazopanib and nilotinib can inhibit UGT1A1 enzyme function, which may lead to an increased incidence of hyperbilirubinemia in UGT1A1 IMs or PMs.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Literature Review

A literature search was performed to identify studies analyzing the correlation between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, or nilotinib toxicity. Specifically, the PubMed® database was searched from 1966 to June 2020 for the following keywords: (UGT1A1 or UGT1A or Gilbert or uridine diphosphate glucuronidation) and (irinotecan or belinostat or pazopanib or nilotinib). Additional search terms for pazopanib included human leukocyte antigen (HLA) or HLA-B or HLA-B*57:01. Inclusion criteria for publications were meta-analyses, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), posthoc analyses, and clinical trials investigating the association between UGT1A1 and clinical outcomes (e.g., diarrhea, neutropenia, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated alanine aminotransferase (E-ALT), dosage changes, or drug discontinuation). Studies included in this review were chosen considering the relevant characteristics from Thorn et al. [37].

Due to the large quantity of published data investigating the association of UGT1A1 polymorphisms and irinotecan toxicity, many of which were retrospective studies consisting of small patient cohorts, we focused on meta-analyses and prospective studies that were not included in the meta-analyses identified investigating UGT1A1-guided irinotecan therapy.

2.2. Pharmacogenetic Guidance Resources

There are several resources for genotype-guided pharmacotherapy recommendations, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), CPIC, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG), European Medicines Agency (EMA), and peer-reviewed primary literature, including clinical trials and meta-analyses [10,38,39,40,41,42,43]. CPIC, DPWG, NCCN, FDA, and EMA were identified as established resources for information regarding genotype-guided cancer pharmacotherapy. Recommendations, or lack of recommendations, were collected for UGT1A1-guided irinotecan, nilotinib, or belinostat therapy, along with UGT1A1/HLA-B*57:01-guided therapy for pazopanib.

3. Results

3.1. Drug Concentration-Based Toxicity in UGT1A1 Polymorphism Carriers

3.1.1. UGT1A1-Irinotecan

Irinotecan is a topoisomerase I inhibitor used to treat numerous cancer types, including gastrointestinal cancers, commonly as part of combination therapy with fluoropyrimidines. Irinotecan is a prodrug metabolized by carboxylesterases to the active metabolite SN-38, which has approximately 100-fold greater activity than the prodrug [25,44]. SN-38 is eliminated from the body through UGT1A1 mediated glucuronidation to SN-38-glucuronide [44]. UGT1A1*6 and *28 alleles and their impact on the incidence of irinotecan toxicity (severe neutropenia and diarrhea) caused by elevated exposure to SN-38 have been the most extensively studied, with the majority of evidence focused on the UGT1A1*28 allele [41,45,46,47,48,49]. Most studies investigating the interaction between UGT1A1 variants and irinotecan have focused on non-liposomal irinotecan formulations. The impact of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on liposomal irinotecan has not been fully elucidated, though some data supports an initial dose reduction for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes. [50,51].

Ten meta-analyses investigating the association between UGT1A1 polymorphisms (i.e., UGT1A1*6 and *28) and irinotecan-induced toxicities were identified (Table 2). Although some studies suggested both UGT1A1 IMs and PMs were at increased risk of toxicity irrespective of the irinotecan dosage [48,52,53], the majority of data supports a “gene–drug exposure” interaction in which toxicities among UGT1A1 polymorphism carriers were associated with higher levels of irinotecan exposure [52]. The strongest correlations with severe neutropenia and diarrhea were found among UGT1A1*28 homozygotes with irinotecan doses ≥ 180 mg/m2, particularly with doses ≥ 250 mg/m2 [41,52,54]. Hoskins and colleagues proposed that irinotecan-induced toxicity among UGT1A1 PMs was not significantly different than UGT1A1 normal metabolizers (NMs) at doses of less than 150 mg/m2 [52]. Irinotecan dosages that may increase the risk of toxicity among UGT1A1 IMs (i.e., UGT1A1 *1/*6 or *1/*28) have not been fully established. Some meta-analyses reported that for irinotecan doses ≥ 125 mg/m2, UGT1A1 IMs have a significantly higher risk for severe toxicity than UGT1A1 NMs [48,53,55,56]. However, other studies have not found statistically significant findings at doses ≤ 200 mg/m2 [48,54,57]. Evidence from the meta-analyses we identified suggests that UGT1A1 IMs may have a significantly higher risk of irinotecan toxicity than UGT1A1 NMs for doses ≥ 250 mg/m2.

Table 2.

Meta-analyses investigating the pharmacogenetic influence of UGT1A1 with the use of irinotecan.

Recent prospective trials have investigated UGT1A1-guided irinotecan dosing (Table 3). Fujii et al. assessed the impact of prospectively reducing irinotecan doses by 20% for UGT1A1 PMs treated for colorectal cancer [61]. There were no differences in toxicities, disease response rate, or disease control rate for the patients who received a reduced irinotecan dose compared to UGT1A1 IMs or NMs. In the neoadjuvant setting, Catenacci and colleagues investigated preemptive dose reductions for irinotecan (180 mg/m2, 135 mg/m2, and 90 mg/m2 for UGT1A1 NMs, IMs, and PMs, respectively) as part of a FOLFIRINOX regimen. Margin-negative resection rates and pathological response grades did not differ among UGT1A1 genotype groups. The authors also proposed that UGT1A1-guided therapy improved overall tolerability and cumulative dosing based on higher treatment completion rates than historical controls [61]. A phase I dose-finding study explored maximum tolerated doses of irinotecan in bevacizumab-FOLFIRI combination therapy [62,63]. UGT1A1 NMs tolerated a maximum irinotecan dose of 310 mg/m2, whereas UGT1A1 IMs tolerated a maximum dose of 260 mg/m2. Results of the phase I study suggested that UGT1A1 genotyping could identify patients who may tolerate higher doses of irinotecan. Overall, for the trials we identified that assessed disease response rates among prospective UGT1A1-guided irinotecan dosing regimens, there were no differences in outcomes between UGT1A1 genotype groups. Additional prospective, large randomized studies are needed to elucidate further the impact of UGT1A1-guided irinotecan dosing on clinical outcomes, including toxicities and disease response.

Table 3.

Prospective studies investigating safety and efficacy of UGT1A1 guided irinotecan dosing.

3.1.2. UGT1A1-Belinostat

Belinostat is a histone deacetylase inhibitor approved for the treatment of relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that UGT1A1 is the most prominent enzyme involved in belinostat glucuronidation, though UGT1A3, UGT1B4, and UGT2B7 also have significant roles in belinostat metabolism [71,72]. The FDA-approved drug label for belinostat recommends a reduced starting dose of 750 mg/m2 for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes, though published data investigating the influence of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on observed toxicities is limited with most studies predominately focused on pharmacokinetic modeling [34].

A phase I trial investigated the effects of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and toxicities (fatigue, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia) of 48-hour continuous infusion belinostat. Belinostat drug exposure was significantly higher, as measured by half-life and area under the curve, for patients carrying UGT1A1 *28 or *60 decreased function alleles who received doses greater than 400 mg/m2/24 h [73]. UGT1A1 IMs or PMs receiving larger belinostat doses also had increased incidences of higher-grade neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. A pharmacokinetic model of 48-h continuous infusion belinostat did not find an effect of UGT1A1 genotype status on platelet reductions, though the authors hypothesized that the data sets used had insufficient observations to predict differences [74].

Another phase I trial investigated the maximum tolerated belinostat dose combined with cisplatin and etoposide in patients with advanced small-cell lung cancer. The investigators observed an association between decreased belinostat clearance and UGT1A1 *28 or *60 carriers [75]. Those harboring UGT1A1 *28 or *60 alleles also experienced higher grade thrombocytopenia and elevated QTc intervals when compared to patients without UGT1A1 polymorphisms [75]. A followed-up pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation study using data from both the phase I study of 48-h continuous infusion belinostat and the phase I study of belinostat in combination with cisplatin/etoposide suggested that a dose adjustment of belinostat 400 mg/m2/24 h for UGT1A1 IMs and 600 mg/m2/24 h for UGT1A1 NMs would provide equivalent exposures and potentially reduce toxicities for UGT1A1 IMs [76]. These studies also argued that the belinostat drug label should include dosing recommendations for other UGT1A1 decreased function alleles besides UGT1A1*28.

3.2. Hepatotoxicity from UGT1A1-Inhibiting Drugs in UGT1A1 Polymorphism Carriers

3.2.1. UGT1A1 and HLA-B*57:01-Pazopanib

Pazopanib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor indicated for use in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma or advanced soft tissue sarcoma that have received prior chemotherapy. Pazopanib impedes the metabolism of bilirubin through direct inhibition of UGT1A1, and when prescribed to those harboring UGT1A1 genetic variants, the incidence of hyperbilirubinemia is proposed to be higher. A total of 5 studies were found that investigated the influence of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on hyperbilirubinemia in patients treated with pazopanib (Table 4). Two GWAS, including a total of 1486 patients from numerous phase II/III trials implicated UGT1A1 polymorphisms to be significantly associated with total serum bilirubin [30,31]. In a subpopulation of patients who were genotyped for UGT1A1 polymorphisms in the phase III COMPARZ study, UGT1A1*28, *37 or *6 homozygotes or inferred compound heterozygotes had higher baseline bilirubin and were more likely to experience hyperbilirubinemia (OR 9.97, 95% CI 4.13–24.03, p = 7.7 × 10−8) [32]. Similarly, two retrospective analyses of phase II/III studies reported a significant association between UGT1A1*28 homozygotes and hyperbilirubinemia risk with pazopanib [32,33].

Table 4.

Pharmacogenetic influence of UGT1A1 or HLA-B*57:01 on hepatotoxicity with use of pazopanib.

Limited studies have explored using UGT1A1 to guide pazopanib dosage. Henriksen et al. investigated the clinical utility of UGT1A1 genotyping to guide dose adjustments for metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with pazopanib who developed liver toxicity [20]. Of 261 patients in this study, 34 developed liver toxicity after a median of 29 days starting pazopanib. Eighteen of the 34 patients (53%) were UGT1A1 IMs, and 7 patients (21%) were UGT1A1 PMs. The median length of pazopanib interruption was 75 days for UGT1A1 PMs, 22 days for IMs, and 28 days for NMs. Pazopanib was restarted at very low doses for UGT1A1 PMs (median dose of 167 mg) and IMs (median dose of 217 mg). Of interest, UGT1A1 polymorphisms were associated with improved outcomes, with UGT1A1 IMs having the longest median progressive free survival of 34.2 months followed by 22.3 months for PMs. There were limitations to this study, including the lack of a detailed algorithm for UGT1A1-guided dose adjustments and only a small subset of patients were UGT1A1 genotyped.

Pharmacogenetic studies have also investigated whether polymorphisms in other pharmacogenes impact pazopanib toxicity. The HLA-B*57:01 allele has emerged as potentially influencing pazopanib toxicity. Pazopanib is proposed to interact with the HLA-B*57:01 binding cleft, leading to T-cell activation and increased incidence of immune-mediated hepatotoxicity in HLA-B*57:01 carriers [77]. Pazopanib-HLA-B*57:01 immune-mediated hepatotoxicity was assessed in a discovery cohort of eight phase II/III trials (n = 1188), a second confirmatory cohort of 23 additional phase I–III trials (n = 1002), and a GWAS for time to elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (Table 4, Tables S1 and S2) [77]. For the combined discovery and confirmatory cohorts, HLA-B*57:01 was significantly associated with elevated ALT (p ≤ 5.4 × 10−4). Overall, HLA-B*57:01 carriers had a 1.5- to 2.0-fold greater risk for elevated ALT ≥ 3 times the upper normal limit. The GWAS meta-analysis for time to ALT ≥ 3 times the upper limit did not reveal any significant variant associations. Additionally, patients with both elevated ALT and hyperbilirubinemia were analyzed for HLA-B*57:01 and UGT1A1 variants. No patients carried both risk alleles.

3.2.2. UGT1A1-Nilotinib

Nilotinib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat patients with BCR-ABL positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) [23,78]. Similar to pazopanib, nilotinib is also a potent inhibitor of UGT1A1, impeding the elimination of bilirubin. Those with UGT1A1 polymorphisms prescribed nilotinib are proposed to have an increased risk of hyperbilirubinemia [79]. Retrospective analysis of a phase I/II clinical trial of nilotinib in patients with BCR-ABL positive CML or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) found that UGT1A1*28 homozygotes had a significant risk of grade 3/4 hyperbilirubinemia [28]. A population pharmacokinetics study of 493 patients with CML receiving nilotinib investigated the impact of UGT1A1 variants on toxicity [29]. For UGT1A1 NMs, IMs, and PMs, high-grade hyperbilirubinemia occurred at 6%, 12%, and 48%, respectively. Furthermore, UGT1A1 PMs were more likely to develop high-grade hyperbilirubinemia at lower serum concentrations of nilotinib. However, not all investigations have found an association between UGT1A1 PMs and hepatotoxicity in patients receiving nilotinib [80].

Case studies have also reported nilotinib toxicities among UGT1A1 PMs. Assessment of UGT1A1 *6,*27, and *28 alleles in 34 Japanese patients with CML receiving nilotinib found that UGT1A1 PMs (*6/*6, *6/*28, and *28/*28) had increased rates of hyperbilirubinemia and greater nilotinib dose reductions [81]. A retrospective case-series including eight Japanese patients with CML receiving nilotinib found three UGT1A1 PMs (two *6 homozygotes, one *6/*28 compound heterozygote) experienced high-grade adverse events. In comparison, only two of the five UGT1A1 NMs experienced high-grade toxicities [82]. Single patient case reports have described similar findings of severe nilotinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia among UGT1A1 PMs [83,84,85,86]. Some of the studies identified in our review proposed that UGT1A1 results may help avoid treatment delays and adverse events, but there is a lack of implementation studies assessing UGT1A1-guided nilotinib prescribing.

3.3. Comparison of Pharmacogenetic Resources and Guidelines

CPIC, DPWG, EMA, FDA, and NCCN were identified as established pharmacogenetic resources to guide the application of genetic information to patient care. These resources were reviewed to determine if recommendations are provided for UGT1A1-guided irinotecan, belinostat, or nilotinib therapy, along with UGT1A1/HLA-B*57:01-guided therapy for pazopanib (Table 5). The FDA, DPWG, and EMA all recommend irinotecan dose reductions for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes, though specific dose reductions vary by resource. The FDA also provides specific recommendations for liposomal irinotecan with an initial starting dose of 50 mg/m2 (~30% dose reduction) for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes [50]. DPWG states that irinotecan dose adjustments for UGT1A1*28 heterozygotes (i.e., UGT1A1 *1/*28) are not warranted, with the other pharmacogenetic resources not providing any specific recommendations for UGT1A1*28 heterozygotes. CPIC guidelines for adjusting irinotecan dose based on UGT1A1 status are currently not available, but CPIC categorizes UGT1A1-irinotecan as “level A” where the preponderance of evidence is deemed sufficiently strong that genetic information should be used to individualize pharmacotherapy [87,88]. NCCN, however, states that guidelines for using UGT1A1 to guide irinotecan dosing in clinical practice have not yet been established. None of the identified pharmacogenetic resources provided information regarding other UGT1A1 alleles.

Table 5.

Comparison of UGT1A1 pharmacogenetic recommendations between guideline and administrative authorities.

The FDA-approved drug label for belinostat provides specific dosing recommendations for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes, a dose reduction to 750 mg/m2 [34]. The drug label does not provide any specific recommendations for UGT1A1*28 heterozygotes or other UGT1A1 alleles. None of the other pharmacogenetic resources currently provide guidance for belinostat dose adjustments based on UGT1A1 results. CPIC categorizes UGT1A1-belinostat as level B, where evidence, though not as strong, supports that genetic information could be used to guided drug prescribing.

The FDA Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations indicates that UGT1A1 status may potentially impact pazopanib or nilotinib safety [40]. Specifically, UGT1A1*28 homozygotes may have a higher risk for pazopanib or nilotinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia. The FDA Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations also indicates that HLA-B*57:01 carriers may have an elevated risk for pazopanib-induced hepatotoxicity. UGT1A1-nilotinib and UGT1A1/HLA-B*57:01-pazopanib are categorized by CPIC as level B/C, indicating that evidence is not clear for supporting genotype-guided prescribing. None of the identified pharmacogenetic resources currently provide recommendations for using UGT1A1 to guide nilotinib or pazopanib prescribing or HLA-B*57:01 status to guide pazopanib prescribing.

3.4. Other Anticancer Drugs with Potential UGT1A1 Considerations

Our review focused on anticancer drugs that either have UGT1A1-guided prescribing recommendations provided by an established pharmacogenetics resource or anticancer drugs listed in the FDA Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations stating that UGT1A1 status can potentially impact drug safety. The association between UGT1A1 and drug toxicity has been investigated for several other anticancer drugs, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib, erlotinib, and imatinib [89,90]. To date, evidence for these other anticancer drugs has not been sufficiently strong to warrant considerations for UGT1A1 prescribing actions. Of interest, sacituzumab govitecan-hziy was recently approved to treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer patients who have received at least two prior therapies for metastatic disease [91,92]. Sacituzumab govitecan is a Trop-2 directed antibody conjugated with the topoisomerase inhibitor SN-38. Based on clinical data to date, up to 72% of patients receiving sacituzumab govitecan have experienced grade 3/4 adverse reactions, including neutropenia (43%) and diarrhea (9%) [92]. The FDA-approved drug label states that UGT1A1*28 homozygotes have an increased risk of neutropenia, but limited data have been published regarding the association between UGT1A1 and sacituzumab govitecan toxicity [93]. Further analysis of clinical trial data, including the ASCENT trial, may provide additional insights on whether UGT1A1 polymorphisms influence sacituzumab govitecan toxicity [91,94,95].

4. Discussion

Utilizing genetic information to guide therapeutic decision-making in the oncology setting is rapidly becoming part of routine care. The exponential growth of commercially available anticancer drugs that target specific genetic mutations along with molecularly focused clinical trials are expanding treatment options for cancer patients. Furthermore, cancer patients have a high prevalence of exposure to drugs influenced by pharmacogenetic variants, with certain gene–drug interactions associated with severe and potentially life-threatening adverse events [88,96]. A piecemeal approach of testing one gene for one drug no longer reflects the clinical reality that multiple genetic variants can impact both anticancer regimens and supportive care therapies. As such, multi-gene panel testing inclusive of targeted next-generation sequencing platforms are emerging as preferred approaches for genetic testing in oncology. In certain instances, sequencing platforms can interrogate hundreds of genes and thousands of variants representing both somatic and germline findings [97,98]. In the not too distant future, whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing of the tumor and germline may become commonplace in oncology. A limitation of multi-gene assays is that clinicians may be exposed to vast amounts of genetic information that can potentially impact pharmacotherapy outcomes, but there may be a lack of guidance for applying to patient care for certain genes. We highlighted UGT1A1 as an example focusing on irinotecan, belinostat, pazopanib, and nilotinib.

Numerous studies have investigated the influence of UGT1A1 on irinotecan toxicity, with evidence from meta-analyses supporting dose adjustments for UGT1A1 PMs receiving higher irinotecan doses to mitigate severe toxicities. The strongest correlations between UGT1A1 and irinotecan toxicities have been observed with UGT1A1 PMs receiving doses ≥ 250 mg/m2, though doses these large are typically no longer used in clinical settings. The meta-analyses we identified in this review also support dose adjustments for UGT1A1 PMs receiving irinotecan doses ≥ 180 mg/m2. Although data support the clinical implementation of UGT1A1 genotyping to guide dose adjustments for those receiving ≥ 180 mg/m2 irinotecan, the implications for lower irinotecan dosages have not been fully established. Prior studies have proposed that UGT1A1 variants do not significantly influence irinotecan-induced toxicity for doses ≤ 150 mg/m2, with further analyses needed to determine the role of UGT1A1-guided therapy for lower irinotecan doses [52].

Irinotecan is commonly used in combination with other anticancer drugs that have similar adverse effects, which can potentially influence toxicity risks. In addition to UGT1A1 mediating elimination of the active metabolite SN-38, the parent drug irinotecan is metabolized by CYP3A4 [99]. Co-administration of drugs that strongly inhibit CYP3A4 or UGT1A1 can also increase exposure to SN-38 [35]. Thus, both gene–drug and drug–drug interactions can influence irinotecan toxicity risks.

Yang et al.’s meta-analysis [59] was further analyzed by Hulshof et al. for validity and utility of pre-therapeutic genotyping of UGT1A1 in Asian and Caucasian carriers of *6 and *28 alleles treated with irinotecan [99]. For *28 carriers, the number of patients that would need to receive dose reductions (number needed to treat) to prevent ≥ grade III neutropenia was 9, and to prevent ≥ grade III diarrhea was 14. The number of patients needed to be genotyped to prevent ≥ grade III neutropenia and ≥ grade III diarrhea was 79 and 127, respectively [100]. For *6 allele carriers, the number of patients that would need to receive dose reductions to prevent ≥ grade III neutropenia was 8, and to prevent ≥ grade III diarrhea was 11. The number of patients that would need to be genotyped to prevent ≥ grade III neutropenia and ≥ grade III diarrhea was 376 and 564, respectively [101].

In addition to utility, the value of preemptive UGT1A1 testing has been reported as cost-effective and, in some instances, cost-saving [101,102,103,104,105,106]. The majority of data for cost savings, though, are from simulations rather than measuring actual healthcare costs in a prospective setting. Cost evaluations have traditionally focused on single gene–drug models, which are not reflective of current clinical realities that cancer patients are exposed to numerous drugs influenced by genetic variants [88]. Studies are emerging that multi-gene panels may have greater cost-effectiveness due to reuse of genetic test results [107,108]. Further studies are needed that incorporate multi-gene testing strategies and reuse of genetic results into cost-effectiveness models.

The majority of studies assessing the influence of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on irinotecan therapy have been retrospective and focused on toxicities, with few studies investigating prospective UGT1A1-guided irinotecan dosing and impact on disease outcomes. Clinical trials exploring preemptive UGT1A1-guided irinotecan therapy are emerging with initial results suggestive of no differences in disease response rates for those who received a reduced irinotecan dose based on UGT1A1 genotype [61,64]. Catenacci et al. proposed that reduced irinotecan doses for UGT1A1 PMs may result in higher treatment completion rates which could potentially improve treatment outcomes [64]. In contrast, UGT1A1 NMs may be underdosed. A dose-finding study suggested that the recommended dose of 180 mg/m2 for irinotecan in the FOLFIRI regimen was lower than the dose that can be tolerated by UGT1A1 NMs [63]. A follow-up phase II randomized trial compared the FOLFIRI regimen to a high-dose irinotecan FOLFIRI regimen in colorectal cancer patients, where UGT1A1 NMsin the high-dose FOLFIRI cohort received 300 mg/m2 irinotecan [66]. The overall response rate was significantly greater in the high-dose FOLFIRI cohort, and no differences in severe toxicities were observed, though there was no difference in survival between cohorts. Taken together, lower irinotecan doses for UGT1A1 PMs and higher irinotecan doses for UGT1A1 NMs may have the potential to increase disease response rates. Additional prospective, randomized studies to further elucidate the impact of preemptive UGT1A1-guided irinotecan dosing on clinical outcomes, including disease response, may further support the routine use of UGT1A1 to guide irinotecan dosing.

The FDA-approved drug label for belinostat recommends a reduced starting dose of 750 mg/m2 for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes, though we found limited published data supporting this specific dose recommendation. For the published studies assessing the impact of UGT1A1 on belinostat toxicities, evidence was supportive of UGT1A1 PMs having an increased risk of hyperbilirubinemia. Similarly, evidence was supportive of UGT1A1 variants being predictive of pazopanib or nilotinib toxicity. How to mitigate toxicity risks based on UGT1A1 information is uncertain, as there appears to be limited data available to extrapolate pazopanib or nilotinib dose reductions based on UGT1A1 status. Furthermore, clinical studies have correlated increased pazopanib exposure and occurrence of adverse events with improved disease outcomes, suggesting that pazopanib plasma concentrations for efficacy and toxicity overlap [109,110]. Taken together, there is insufficient evidence to recommend preemptive pazopanib or nilotinib dose reductions based on UGT1A1 status. The presence of UGT1A1 variants could help identify patients who may need closer monitoring due to toxicity risks. For those who develop hepatotoxicity, the drug inserts for pazopanib and nilotinib provide guidance for dose modifications.

Arbitrio and colleagues recently described the complex process of pharmacogenetic biomarker validation and translation to clinical practice [111]. Sample size, study endpoints, and reproducibility are important considerations for biomarker discovery and validation. A limited number of studies were identified that assessed the impact of UGT1A1 variants on pazopanib or nilotinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia. Furthermore, the majority of data consisted of subpopulations identified from clinical trials that were not directly investigating the impact of UGT1A1 on these drugs. Reproducing results in larger study cohorts specifically designed to assess the impact of UGT1A1 on pazopanib or nilotinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia would further validate UGT1A1 as a pharmacogenetic biomarker for these drugs. Biomarker clinical utility demonstrated by improved patient management is also an important consideration [111]. There is currently a dearth of strong clinical data demonstrating UGT1A1-guided pazopanib or nilotinib prescribing improves patient care. The need for further pharmacogenetic biomarker validation and clinical utility studies supports our conclusion that there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend UGT1A1 genotyping to guide pazopanib or nilotinib prescribing. The evidence supporting UGT1A1-guided irinotecan or belinostat dosing has been deemed sufficiently strong for regulatory bodies such as the FDA to provide specific dosing recommendations [34,35]. However, there is a lack of recommendations for performing UGT1A1 genotyping before prescribing irinotecan or belinostat. Arbitrio et al. identified genotyping recommendations as a key consideration for supporting the clinical implementation of pharmacogenetic biomarkers [111].

The established pharmacogenetic resources that we identified as part of this review were mostly concordant that evidence is sufficiently strong to consider using UGT1A1 to guide irinotecan dosing. However, one identified resource suggested that using UGT1A1 to guide irinotecan dosing in clinical practice has not yet been established. Prior studies have described a lack of consensus for pharmacogenetic guidance across resources, which may hinder the integration of pharmacogenetics into patient care [112,113]. However, there are examples of collaborative efforts among pharmacogenetic resources to establish consistencies for genotype interpretations and clinical recommendations [114]. No pharmacogenetic resources provided UGT1A1-guided recommendations for pazopanib or nilotinib, and besides the FDA, no pharmacogenetic resources provided UGT1A1-guided recommendations for belinostat.

For the pharmacogenetic resources that did provide UGT1A1-guided recommendations, they were all specific to UGT1A1*28. Other UGT1A1 variants are predicted to result in decreased function, including UGT1A1*6 and *37. The UGT1A1*6 allele is more commonly observed in Asian populations, and when implementing UGT1A1 genotyping into diverse patient populations, the UGT1A1*6 allele is likely to be observed [6]. Published data support that the UGT1A1*6 allele is associated with an increased risk of irinotecan-induced toxicity [58], and pharmacokinetic modeling suggests that other UGT1A1 decreased function alleles besides UGT1A1*28 influence belinostat exposure [76]. For patients homozygous for other UGT1A1 decreased function alleles who are predicted to be PMs, it may be reasonable to extrapolate dose adjustments from pharmacogenetic resources. Further research is needed to support implementation into diverse patient populations, as differences in enzymatic function among alleles may influence drug exposure. Following established processes for pharmacogenetic biomarker discovery and validation for less commonly observed UGT1A1 alleles may provide the additional evidence needed to support translation into clinical practice [111]. Other considerations for implementing UGT1A1 into patient care include the need for annotation of discrete results, electronic health record decision support tools, and provider education tools [115,116].

5. Conclusions

Evidence supports the use of UGT1A1 information to guide irinotecan dosing, particularly for patients receiving doses ≥ 180 mg/m2. The drug label for belinostat recommends a reduced starting dose of 750 mg/m2 for UGT1A1*28 homozygotes, though we found limited published data supporting this specific dose recommendation. Evidence suggested that UGT1A1 variants are predictive of pazopanib or nilotinib toxicity. However, there is insufficient evidence to recommend preemptive pazopanib or nilotinib dose reductions based on UGT1A1 status.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers13071566/s1, Table S1: Summary of findings from Xu et al.’s meta-analysis investigating the association between liver toxicity and HLA-B*57:01, Table S2: Summary of Xu et al’s meta-analysis of eight trials in the discovery, and 23 trials in the confirmatory, pharmacogenetic liver toxicity analyses with HLA-B*57:01.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: R.S.N. and J.K.H. Data collection, analysis and writing of the manuscript: R.S.N., N.D.S., S.B., E.C., A.D.C., I.I., R.L., A.S.P., S.M.S., E.M.T. and J.K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30 CA076292 (R.S.N., E.C., A.D.C., I.I., R.L., J.K.H.) and ASHP (J.K.H.).

Acknowledgments

ARUP Laboratories Sr. Graphics Designer, Natalia Wilkins-Tyler, provided support in developing figures and tables in this review.

Conflicts of Interest

In the past 12 months, Sandra M. Swain has received: Personal Fees for consulting/advisory services/nonpromotional speaking (AstraZeneca, Athenex, Daiichi-Sankyo, Genentech/Roche, Exact Sciences (Genomic Health), Natera, Bejing Medical Foundation). Institutional research support from Kailos Genetics. And other support from AstraZeneca (member, independent data monitoring committee) and Genentech/Roche (third-party writing assistance). JKH has received consulting fees from Quest Diagnositics and receives research support from OneOme. Sal Bottiglieri has the following disclosures: Eisai Co., Ltd. (advisory board) and Merck, Inc. (speaker board).

References

- Golan, T.; Hammel, P.; Reni, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Macarulla, T.; Hall, M.J.; Park, J.O.; Hochhauser, D.; Arnold, D.; Oh, D.Y.; et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Carreira, S.; Sandhu, S.; Miranda, S.; Mossop, H.; Perez-Lopez, R.; Nava Rodrigues, D.; Robinson, D.; Omlin, A.; Tunariu, N.; et al. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstutz, U.; Henricks, L.M.; Offer, S.M.; Barbarino, J.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Swen, J.J.; Klein, T.E.; McLeod, H.L.; Caudle, K.E.; Diasio, R.B.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relling, M.V.; Schwab, M.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Suarez-Kurtz, G.; Pui, C.H.; Stein, C.M.; Moyer, A.M.; Evans, W.E.; Klein, T.E.; Antillon-Klussmann, F.G.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for Thiopurine Dosing Based on TPMT and NUDT15 Genotypes: 2018 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 105, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.K.; Quilitz, R.E.; Komrokji, R.S.; Kubal, T.E.; Lancet, J.E.; Pasikhova, Y.; Qin, D.; So, W.; Caceres, G.; Kelly, K.; et al. Prospective CYP2C19-Guided Voriconazole Prophylaxis in Patients with Neutropenic Acute Myeloid Leukemia Reduces the Incidence of Subtherapeutic Antifungal Plasma Concentrations. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 107, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammal, R.S.; Court, M.H.; Haidar, C.E.; Iwuchukwu, O.F.; Gaur, A.H.; Alvarellos, M.; Guillemette, C.; Lennox, J.L.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Brummel, S.S.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for UGT1A1 and Atazanavir Prescribing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 99, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutler, E.; Gelbart, T.; Demina, A. Racial variability in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 (UGT1A1) promoter: A balanced polymorphism for regulation of bilirubin metabolism? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 8170–8174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Ybazeta, G.; Destro-Bisol, G.; Petzl-Erler, M.L.; Di Rienzo, A. Variability at the uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 promoter in human populations and primates. Pharmacogenetics 1999, 9, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.H.; Venuto, C.; Ritchie, M.D.; Morse, G.D.; Daar, E.S.; McLaren, P.J.; Haas, D.W. Genomewide association study of atazanavir pharmacokinetics and hyperbilirubinemia in AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol A5202. Pharm. Genom. 2014, 24, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relling, M.V.; Klein, T.E. CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium of the Pharmacogenomics Research Network. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.A.; Innocenti, F.; Ratain, M.J. Pharmacogenetic testing for uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 polymorphisms: Are we there yet? Pharmacotherapy 2008, 28, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPIC® Guideline for Atazanavir and UGT1A1. Available online: https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/guideline-for-atazanavir-and-ugt1a1 (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Bosma, P.J.; Chowdhury, J.R.; Bakker, C.; Gantla, S.; de Boer, A.; Oostra, B.A.; Lindhout, D.; Tytgat, G.N.; Jansen, P.L.; Oude Elferink, R.P.; et al. The genetic basis of the reduced expression of bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 in Gilbert’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.; Evans, J. Population studies on Gilbert’s syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1975, 12, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticova, E.; Jirsa, M. New insights in bilirubin metabolism and their clinical implications. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 6398–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aono, S.; Yamada, Y.; Keino, H.; Sasaoka, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Onishi, S.; Mimura, S.; Koiwai, O.; Sato, H. A new type of defect in the gene for bilirubin uridine 5’-diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase in a patient with Crigler–Najjar syndrome type I. Pediatr. Res. 1994, 35, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Soeda, Y.; Kamisako, T.; Hosaka, H.; Fukano, M.; Sato, H.; Fujiyama, Y.; Adachi, Y.; Satoh, Y.; Bamba, T. Analysis of bilirubin uridine 5’-diphosphate (UDP)-glucuronosyltransferase gene mutations in seven patients with Crigler–Najjar syndrome type II. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 43, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Bracarda, S.; Chen, M.; Norry, E.; Compton, N.; Heise, M.; Hutson, T.; Harter, P.; Carpenter, C.; Pandite, L.; et al. Characterisation of liver chemistry abnormalities associated with pazopanib monotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials in advanced cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miners, J.O.; Chau, N.; Rowland, A.; Burns, K.; McKinnon, R.A.; Mackenzie, P.I.; Tucker, G.T.; Knights, K.M.; Kichenadasse, G. Inhibition of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes by lapatinib, pazopanib, regorafenib and sorafenib: Implications for hyperbilirubinemia. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 129, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, J.N.; Bottger, P.; Hermansen, C.K.; Ladefoged, S.A.; Nissen, P.H.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.; Fink, T.L.; Donskov, F. Pazopanib-Induced Liver Toxicity in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Effect of UGT1A1 Polymorphism on Pazopanib Dose Reduction, Safety, and Patient Outcomes. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danoff, T.M.; Campbell, D.A.; McCarthy, L.C.; Lewis, K.F.; Repasch, M.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Spurr, N.K.; Purvis, I.J.; Roses, A.D.; Xu, C.F. A Gilbert’s syndrome UGT1A1 variant confers susceptibility to tranilast-induced hyperbilirubinemia. Pharm. J. 2004, 4, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lankisch, T.O.; Moebius, U.; Wehmeier, M.; Behrens, G.; Manns, M.P.; Schmidt, R.E.; Strassburg, C.P. Gilbert’s disease and atazanavir: From phenotype to UDP-glucuronosyltransferase haplotype. Hepatology 2006, 44, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Tasigna (Nilotinib Hydrochloride) [Package Insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/022068s033lbl.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. PrTasigna (Nilotinib Hydrochloride Monohydrate) [Package Insert]. The Drug and Health Product Register Website. Available online: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00046617.PDF (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Barbarino, J.M.; Haidar, C.E.; Klein, T.E.; Altman, R.B. PharmGKB summary: Very important pharmacogene information for UGT1A1. Pharm. Genom. 2014, 24, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcoma (STS) Treatment|VOTRIENT® (Pazopanib) Tablets. Available online: https://www.hcp.novartis.com/products/votrient/advanced-soft-tissue-sarcoma (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Treatment|VOTRIENT® (Pazopanib) Tablets. Available online: https://www.hcp.novartis.com/products/votrient/advanced-renal-cell-carcinoma (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Singer, J.B.; Shou, Y.; Giles, F.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Hsu, Y.; Robeva, A.S.; Rae, P.; Weitzman, A.; Meyer, J.M.; Dugan, M.; et al. UGT1A1 promoter polymorphism increases risk of nilotinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia. Leukemia 2007, 21, 2311–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, F.J.; Yin, O.Q.; Sallas, W.M.; le Coutre, P.D.; Woodman, R.C.; Ottmann, O.G.; Baccarani, M.; Kantarjian, H.M. Nilotinib population pharmacokinetics and exposure-response analysis in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia. Eur. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013, 69, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Xu, C.-F.; Choueiri, T.K.; Figlin, R.A.; Sternberg, C.N.; King, K.S.; Xue, Z.; Stinnett, S.; Deen, K.C.; Carpenter, C.; et al. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) of efficacy and safety endpoints in pazopanib- or sunitinib-treated patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambia, G.; Johnson, T.; Floquet, A.; Heitz, F.; Park, S.-Y.; Buck, M.; Gallego, R.Ã.l.; Shimada, M.; Vergote, I.; Avall-Lundqvist, E.; et al. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) of pazopanib efficacy and safety in patients with ovarian cancer who have not progressed following first-line standard therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Johnson, T.; Choueiri, T.K.; Deen, K.C.; Xue, Z.; Pandite, L.N.; Carpenter, C.; Xu, C.F. Hyperbilirubinemia in pazopanib- or sunitinib-treated patients in COMPARZ is associated with UGT1A1 polymorphisms. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2927–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.F.; Reck, B.H.; Xue, Z.; Huang, L.; Baker, K.L.; Chen, M.; Chen, E.P.; Ellens, H.E.; Mooser, V.E.; Cardon, L.R.; et al. Pazopanib-induced hyperbilirubinemia is associated with Gilbert’s syndrome UGT1A1 polymorphism. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acrotech. Beleodaq (Belinostat) [Package Insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/206256s003lbl.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Pfizer. Camptosar (Irinotecan) [Package Insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=020571 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Votrient (Pazopanib Hydrochloride) [Package Insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/022465s029lbl.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Thorn, C.F.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Hachad, H.; Johnson, J.A.; McDonagh, E.M.; Ratain, M.J.; Relling, M.V.; Scott, S.A.; Altman, R.B.; Klein, T.E. Essential Characteristics of Pharmacogenomics Study Publications. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 105, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/committees/working-parties-other-groups/chmp/pharmacogenomics-working-party (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/precision-medicine/table-pharmacogenetic-associations (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Swen, J.J.; Nijenhuis, M.; de Boer, A.; Grandia, L.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.H.; Mulder, H.; Rongen, G.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Schalekamp, T.; Touw, D.J.; et al. Pharmacogenetics: From Bench to Byte—An Update of Guidelines. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swen, J.J.; Wilting, I.; de Goede, A.L.; Grandia, L.; Mulder, H.; Touw, D.J.; de Boer, A.; Conemans, J.M.H.; Egberts, T.C.G.; Klungel, O.H.; et al. Pharmacogenetics: From Bench to Byte. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 83, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmann, F.; Caneva, L.; Papaluca, M. European Medicines Agency initiatives and perspectives on pharmacogenomics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 77, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawato, Y.; Aonuma, M.; Hirota, Y.; Kuga, H.; Sato, K. Intracellular roles of SN-38, a metabolite of the camptothecin derivative CPT-11, in the antitumor effect of CPT-11. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 4187–4191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Etienne-Grimaldi, M.C.; Boyer, J.C.; Thomas, F.; Quaranta, S.; Picard, N.; Loriot, M.A.; Narjoz, C.; Poncet, D.; Gagnieu, M.C.; Ged, C.; et al. UGT1A1 genotype and irinotecan therapy: General review and implementation in routine practice. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 29, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Man, F.M.; Goey, A.K.L.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Bins, S. Individualization of Irinotecan Treatment: A Review of Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Pharmacogenetics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 57, 1229–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association (KNMP) Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) Pharmacogenomic Guidelines. Available online: https://upgx.eu/guidelines/ (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Liu, X.; Cheng, D.; Kuang, Q.; Liu, G.; Xu, W. Association of UGT1A1*28 polymorphisms with irinotecan-induced toxicities in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis in Caucasians. Pharm. J. 2014, 14, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Sparreboom, A. Pharmacogenetics of irinotecan disposition and toxicity: A review. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 5, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsen Inc. Onivyde (Irinotecan Hydrochloride) [Package Insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/207793lbl.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Adiwijaya, B.S.; Kim, J.; Lang, I.; Csõszi, T.; Cubillo, A.; Chen, J.S.; Wong, M.; Park, J.O.; Kim, J.S.; Rau, K.M.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Liposomal Irinotecan in Patients with Cancer. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 102, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Y.; Yu, Q.; Pei, Q.; Guo, C. Dose-dependent association between UGT1A1*28 genotype and irinotecan-induced neutropenia: Low doses also increase risk. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3832–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Hu, M.; Cui, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Liang, L.; Huang, F. UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28 polymorphisms are correlated with irinotecan-induced toxicity: A meta-analysis. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 14, e479–e489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, J.M.; Goldberg, R.M.; Qu, P.; Ibrahim, J.G.; McLeod, H.L. UGT1A1*28 genotype and irinotecan-induced neutropenia: Dose matters. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 1290–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Lu, J.; Duan, W.; Dai, Z.M.; Wang, M.; Lin, S.; Yang, P.T.; Tian, T.; Liu, K.; Zhu, Y.Y.; et al. Predictive Value of UGT1A1*28 Polymorphism in Irinotecan-based Chemotherapy. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, Y.S. Dose-dependent association between UGT1A1*28 polymorphism and irinotecan-induced diarrhoea: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. 2010, 46, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Guo, Z.; Liang, W.; He, J.; Huang, L.; Deng, Q.; Tang, H.; Pan, H.; Guo, M.; et al. UGT1A1 polymorphisms with irinotecan-induced toxicities and treatment outcome in Asians with Lung Cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 79, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Hu, F.; Li, C.Y.; Fang, J.M.; Chu, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Q. The association of UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28 with irinotecan-induced neutropenia in Asians: A meta-analysis. Biomark. Biochem. Indic. Expo Response Susceptibility Chem. 2014, 19, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.F.; Guo, C.L.; Yu, D.; Zhu, J.; Gong, L.L.; Li, G.R.; Lv, Y.L.; Liu, H.; An, G.Y.; Liu, L.H. Associations between UGT1A1*6 or UGT1A1*6/*28 polymorphisms and irinotecan-induced neutropenia in Asian cancer patients. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 73, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, M.; Hu, J.; Ren, W.; Xie, L.; Sun, Z.P.; Liu, B.R.; Xu, G.X.; Dong, X.L.; Qian, X.P. UGT1A1*6 polymorphisms are correlated with irinotecan-induced toxicity: A system review and meta-analysis in Asians. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 73, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Yamada, Y.; Watanabe, D.; Matsuhashi, N.; Takahashi, T.; Yoshida, K.; Suzuki, A. Dose adjustment of irinotecan based on UGT1A1 polymorphisms in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 83, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toffoli, G.; Sharma, M.R.; Marangon, E.; Posocco, B.; Gray, E.; Mai, Q.; Buonadonna, A.; Polite, B.N.; Miolo, G.; Tabaro, G.; et al. Genotype-Guided Dosing Study of FOLFIRI plus Bevacizumab in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toffoli, G.; Cecchin, E.; Gasparini, G.; D’Andrea, M.; Azzarello, G.; Basso, U.; Mini, E.; Pessa, S.; De Mattia, E.; Lo Re, G.; et al. Genotype-driven phase I study of irinotecan administered in combination with fluorouracil/leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenacci, D.V.T.; Chase, L.; Lomnicki, S.; Karrison, T.; de Wilton Marsh, R.; Rampurwala, M.M.; Narula, S.; Alpert, L.; Setia, N.; Xiao, S.Y.; et al. Evaluation of the Association of Perioperative UGT1A1 Genotype-Dosed gFOLFIRINOX with Margin-Negative Resection Rates and Pathologic Response Grades Among Patients with Locally Advanced Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1921290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.R.; Joshi, S.S.; Karrison, T.G.; Allen, K.; Suh, G.; Marsh, R.; Kozloff, M.F.; Polite, B.N.; Catenacci, D.V.T.; Kindler, H.L. A UGT1A1 genotype-guided dosing study of modified FOLFIRINOX in previously untreated patients with advanced gastrointestinal malignancies. Cancer 2019, 125, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Páez, D.; Tobeña, M.; Fernández-Plana, J.; Sebio, A.; Virgili, A.C.; Cirera, L.; Barnadas, A.; Riera, P.; Sullivan, I.; Salazar, J. Pharmacogenetic clinical randomised phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of FOLFIRI with high-dose irinotecan (HD-FOLFIRI) in metastatic colorectal cancer patients according to their UGT1A 1 genotype. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-J.; Chang, T.-K.; Tsai, H.-L.; Su, W.-C.; Huang, C.-W.; Yeh, Y.-S.; Chang, Y.-T.; Wang, J.-Y. Regorafenib plus FOLFIRI with irinotecan dose escalated according to uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A1genotyping in previous treated metastatic colorectal cancer patients: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oki, E.; Kato, T.; Bando, H.; Yoshino, T.; Muro, K.; Taniguchi, H.; Kagawa, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tsuji, A.; et al. A Multicenter Clinical Phase II Study of FOLFOXIRI Plus Bevacizumab as First-line Therapy in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: QUATTRO Study. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2018, 17, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.; Yoshino, T.; Muro, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Oki, E.; Iwamoto, S.; Tsuji, A.; Nakayama, G.; Emi, Y.; et al. A phase II study of FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab in untreated metastatic colorectal cancer patients: A UGT1A1 genotype and safety results (QUATTRO study). Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, iii9–iii10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Xie, C.; Qiu, H.; Liu, B.; Huang, L.; Peng, P.; Feng, J.; Chen, J.; Zang, A.; et al. UGT1A polymorphisms associated with worse outcome in colorectal cancer patients treated with irinotecan-based chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Zhang, T.; Lu, D.; Liu, J.; Wu, B. In vitro characterization of belinostat glucuronidation: Demonstration of both UGT1A1 and UGT2B7 as the main contributing isozymes. Xenobiotica 2017, 47, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Z.; Ramírez, J.; Yeo, W.; Chan, M.-Y.M.; Thuya, W.-L.; Lau, J.-Y.A.; Wan, S.-C.; Wong, A.L.-A.; Zee, Y.-K.; Lim, R.; et al. Glucuronidation by UGT1A1 is the dominant pathway of the metabolic disposition of belinostat in liver cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goey, A.K.; Sissung, T.M.; Peer, C.J.; Trepel, J.B.; Lee, M.J.; Tomita, Y.; Ehrlich, S.; Bryla, C.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Piekarz, R.; et al. Effects of UGT1A1 genotype on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicities of belinostat administered by 48-hour continuous infusion in patients with cancer. J. Clin Pharm. 2016, 56, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, C.J.; Hall, O.M.; Sissung, T.M.; Piekarz, R.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Bates, S.E.; Figg, W.D. A population pharmacokinetic/toxicity model for the reduction of platelets during a 48-h continuous intravenous infusion of the histone deacetylase inhibitor belinostat. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, S.; Redon, C.E.; Peer, C.J.; Bryla, C.; Lee, M.J.; Trepel, J.B.; Tomita, Y.; Rajan, A.; Giaccone, G.; Bonner, W.M.; et al. Phase I trial of belinostat with cisplatin and etoposide in advanced solid tumors, with a focus on neuroendocrine and small cell cancers of the lung. Anticancer Drugs 2018, 29, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, C.J.; Goey, A.K.; Sissung, T.M.; Erlich, S.; Lee, M.J.; Tomita, Y.; Trepel, J.B.; Piekarz, R.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Bates, S.E.; et al. UGT1A1 genotype-dependent dose adjustment of belinostat in patients with advanced cancers using population pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 56, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.F.; Johnson, T.; Wang, X.; Carpenter, C.; Graves, A.P.; Warren, L.; Xue, Z.; King, K.S.; Fraser, D.J.; Stinnett, S.; et al. HLA-B*57:01 Confers Susceptibility to Pazopanib-Associated Liver Injury in Patients with Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breccia, M.; Alimena, G. Nilotinib: A second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2010, 34, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qosa, H.; Avaritt, B.R.; Hartman, N.R.; Volpe, D.A. In vitro UGT1A1 inhibition by tyrosine kinase inhibitors and association with drug-induced hyperbilirubinemia. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iurlo, A.; Bucelli, C.; Cattaneo, D.; Levati, G.V.; Viani, B.; Tavazzi, D.; Consonni, D.; Baldini, L.; Cappellini, M.D. UGT1A1 genotype does not affect tyrosine kinase inhibitors efficacy and safety in chronic myeloid leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, E283–E285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumiya, M.; Takahashi, N.; Niioka, T.; Kameoka, Y.; Fujishima, N.; Tagawa, H.; Sawada, K.; Miura, M. Influence of UGT1A1 6, 27, and 28 polymorphisms on nilotinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia in Japanese patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Drug Metab. Pharm. 2014, 29, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, T.; Minami, Y.; Mitsuma, A.; Morita, S.; Inada-Inoue, M.; Oguri, T.; Shimokata, T.; Sugishita, M.; Naoe, T.; Ando, Y. Association between severe toxicity of nilotinib and UGT1A1 polymorphisms in Japanese patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 19, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, K.; Sato, T.; Iyama, S.; Ono, K.; Kamihara, Y.; Murase, K.; Kawano, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Miyanishi, K.; Sato, Y.; et al. UGT1A1*28 and *6 polymorphisms and nilotinib-induced unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in a Japanese patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Int. Canc. Conf. J. 2012, 1, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.P.-L.; Poon, W.-T.; Miu Mak, C.; Lam, C.-W.; Kwong, Y.-I.; Chan, A.Y.-W.; Tam, S. Application of pharmacogenetics: UGT1A1*28 and nilotinib-induced unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Pathology 2011, 43, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Cho, H.S.; Bae, Y.K.; Lee, K.H.; Chung, H.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Hyun, M.S. Nilotinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia: Is it a negligible adverse event? Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, e159–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belopolsky, Y.; Grinblatt, D.L.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Sabatini, L.M.; Joseph, N.E.; Fimmel, C.J. A Case of Severe, Nilotinib-Induced Liver Injury. ACG Case Rep. J. 2019, 6, e00003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, K.E.; Klein, T.E.; Hoffman, J.M.; Muller, D.J.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Gong, L.; McDonagh, E.M.; Sangkuhl, K.; Thorn, C.F.; Schwab, M.; et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr. Drug Metab. 2014, 15, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.K.; El Rouby, N.; Ong, H.H.; Schildcrout, J.S.; Ramsey, L.B.; Shi, Y.; Tang, L.A.; Aquilante, C.L.; Beitelshees, A.L.; Blake, K.V.; et al. Opportunity for Genotype-Guided Prescribing Among Adult Patients in 11 U.S. Health Systems. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, M.W.; Smith, M.H.; Maloney, A.; Diasio, R.B. Imatinib-induced hyperbilirubinemia with UGT1A1 (*28) promoter polymorphism: First case series in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann Gastroenterol 2016, 29, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ramírez, J.; House, L.; Ratain, M.J. Comparison of the drug-drug interactions potential of erlotinib and gefitinib via inhibition of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab. Dispos. Biol. Fate Chem. 2010, 38, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligson, J.M.; Patron, A.M.; Berger, M.J.; Harvey, R.D.; Seligson, N.D. Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy: An Antibody-Drug Conjugate for the Treatment of Refractory, Metastatic, Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Ann Pharm. 2020, 1060028020966548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahby, S.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.; Osgood, C.L.; Cheng, J.; Fiero, M.H.; Zhang, L.; Tang, S.; Hamed, S.S.; Song, P.; Charlab, R.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Accelerated Approval of Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy for Third Line Treatment of Metastatic Triple-negative Breast Cancer (mTNBC). Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean, A.J.; Starodub, A.N.; Bardia, A.; Vahdat, L.T.; Isakoff, S.J.; Guarino, M.; Messersmith, W.A.; Picozzi, V.J.; Mayer, I.A.; Wegener, W.A.; et al. Sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132), an anti-Trop-2-SN-38 antibody-drug conjugate for the treatment of diverse epithelial cancers: Safety and pharmacokinetics. Cancer 2017, 123, 3843–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASCENT-Study of Sacituzumab Govitecan in Refractory/Relapsed Triple-Negative Breast Cancer—Full Text View. 2021. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Syed, Y.Y. Sacituzumab Govitecan: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.K.; McLeod, H.L. Probabilistic medicine: A pre-emptive approach is needed for cancer therapeutic risk mitigation. Biomark. Med. 2019, 13, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Johnson, A.; Shufean, M.A.; Kahle, M.; Yang, D.; Woodman, S.E.; Vu, T.; Moorthy, S.; Holla, V.; Meric-Bernstam, F. Operationalization of Next-Generation Sequencing and Decision Support for Precision Oncology. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 2019, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.R.; Warner, J.L.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Miller, R.S. Next-Generation Sequencing and the Clinical Oncology Workflow: Data Challenges, Proposed Solutions, and a Call to Action. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whirl-Carrillo, M.; McDonagh, E.M.; Hebert, J.M.; Gong, L.; Sangkuhl, K.; Thorn, C.F.; Altman, R.B.; Klein, T.E. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 92, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulshof, E.C.; Deenen, M.J.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Gelderblom, H. Pre-therapeutic UGT1A1 genotyping to reduce the risk of irinotecan-induced severe toxicity: Ready for prime time. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 141, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncato, R.; Cecchin, E.; Montico, M.; De Mattia, E.; Giodini, L.; Buonadonna, A.; Solfrini, V.; Innocenti, F.; Toffoli, G. Cost Evaluation of Irinotecan-Related Toxicities Associated with the UGT1A1*28 Patient Genotype. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 102, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Cai, J.; Sun, H.; Li, N.; Xu, C.; Zhang, G.; Sui, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Zheng, B. Cost-effectiveness analysis of UGT1A1*6/*28 genotyping for preventing FOLFIRI-induced severe neutropenia in Chinese colorectal cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzke, B.; Oduncu, F.S.; Severin, F.; Pfeufer, A.; Heinemann, V.; Giessen-Jung, C.; Stollenwerk, B.; Rogowski, W.H. The cost-effectiveness of UGT1A1 genotyping before colorectal cancer treatment with irinotecan from the perspective of the German statutory health insurance. Acta Oncol. 2016, 55, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, M.; Mrhar, A.; Kos, M. Cost-effectiveness of UGT1A1 genotyping in second-line, high-dose, once every 3 weeks irinotecan monotherapy treatment of colorectal cancer. Pharmacogenomics 2008, 9, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, H.T.; Hall, M.J.; Blinder, V.; Schackman, B.R. Cost effectiveness of pharmacogenetic testing for uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 before irinotecan administration for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 2009, 115, 3858–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, Z.; Stenehjem, D.D.; Jacobson, P.; Lou, E.; Nelson, A.; Kuntz, K.M. A cost-effectiveness analysis of pretreatment DPYD and UGT1A1 screening in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) treated with FOLFIRI+bevacizumab (FOLFIRI+Bev). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, D.M.; Van Driest, S.L.; Mosley, J.D.; Wells, Q.S.; Robinson, J.R.; Denny, J.C.; Peterson, J.F. Benefit of Preemptive Pharmacogenetic Information on Clinical Outcome. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, O.M.; Wheeler, S.B.; Cruden, G.; Lee, C.R.; Voora, D.; Dusetzina, S.B.; Wiltshire, T. Cost-Effectiveness of Multigene Pharmacogenetic Testing in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2020, 23, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, C.N.; Motzer, R.J.; Hutson, T.E.; Choueiri, T.K.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Paul, N.; Porta, C.; Grunwald, V.; Dezzani, L.; et al. COMPARZ Post Hoc Analysis: Characterizing Pazopanib Responders with Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttle, A.B.; Ball, H.A.; Molimard, M.; Hutson, T.E.; Carpenter, C.; Rajagopalan, D.; Lin, Y.; Swann, S.; Amado, R.; Pandite, L. Relationships between pazopanib exposure and clinical safety and efficacy in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbitrio, M.; Scionti, F.; Di Martino, M.T.; Caracciolo, D.; Pensabene, L.; Tassone, P.; Tagliaferri, P. Pharmacogenomics Biomarker Discovery and Validation for Translation in Clinical Practice. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhani, R.; Steinacher, L.; Swen, J.J.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Evaluation of Current Regulation and Guidelines of Pharmacogenomic Drug Labels: Opportunities for Improvements. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 107, 1240–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, M.; Attya, M.; Patrinos, G.P. Unraveling heterogeneity of the clinical pharmacogenomic guidelines in oncology practice among major regulatory bodies. Pharmacogenomics 2020, 21, 1247–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, K.E.; Sangkuhl, K.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Swen, J.J.; Haidar, C.E.; Klein, T.E.; Gammal, R.S.; Relling, M.V.; Scott, S.A.; Hertz, D.L.; et al. Standardizing CYP2D6 Genotype to Phenotype Translation: Consensus Recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 13, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, K.D.; Blake, K.; Fletcher-Hoppe, C.; Franciosi, J.; Goto, D.; Hicks, J.K.; Holmes, A.M.; Kanuri, S.H.; Madden, E.B.; Musty, M.D.; et al. Opportunities to implement a sustainable genomic medicine program: Lessons learned from the IGNITE Network. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2019, 21, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.K.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Gumpper, K.F.; Haidar, C.E.; Hoffman, J.M. Integrating pharmacogenomics into electronic health records with clinical decision support. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. AJHP Off. J. Am. Soc. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2016, 73, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).