Abstract

Cyanotoxin occurrence is gaining importance due to anthropogenic activities, climate change and eutrophication. Among them, Microcystins (MCs) and Cylindrospermopsin (CYN) are the most frequently studied due to their ubiquity and toxicity. Although MCs are primary classified as hepatotoxins and CYN as a cytotoxin, they have been shown to induce deleterious effects in a wide range of organs. However, their effects on the immune system are as yet scarcely investigated. Thus, to know the impact of cyanotoxins on the immune system, due to its importance in organisms’ homeostasis, is considered of interest. A review of the scientific literature dealing with the immunotoxicity of MCs and CYN has been performed, and both in vitro and in vivo studies have been considered. Results have confirmed the scarcity of reports on the topic, particularly for CYN. Decreased cell viability, apoptosis or altered functions of immune cells, and changed levels and mRNA expression of cytokines are among the most common effects reported. Underlying mechanisms, however, are still not yet fully elucidated. Further research is needed in order to have a full picture of cyanotoxin immunotoxicity.

Key Contribution:

Microcystins and Cylindrospermopsin induce immunotoxicity in in vitro and in vivo models; however; the mechanisms involved are not yet fully elucidated.

1. Introduction

Nowadays toxic cyanobacterial blooms are recognized worldwide as an emerging environmental threat because they can produce a sizeable number of secondary metabolites [1]. These secondary metabolites, called cyanotoxins, are produced as a consequence of an increase in cyanobacterial blooms resulting from anthropogenic activities, climate change and eutrophication [2,3]. Humans can be exposed to cyanotoxins in different ways, mainly orally, although inhalation and dermal exposure during recreational activities are also common [2]. Due to the toxic risks resulting from exposure to cyanotoxins, The World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) have catalogued cyanobacteria as an emerging health issue [4,5].

Cyanotoxins can be classified according to their target organ. At present the main toxin groups are hepatotoxins, cytotoxins, neurotoxins, dermatoxins, and irritant toxins [6]. Among cyanotoxins, Microcystins (MCs) are cyclic heptapeptides composed of five common amino acids, plus a pair of variable L-amino acids [7]. These cyanotoxins act mainly by inhibiting the protein phosphatases 1 and 2A (PP1 and PP2A), and to date at least 279 MC congeners have been recognized [8]. Microcystin-LR (MC-LR) is the variant more frequently assessed, although some other variants (MC-RR, MC-YR) have been gaining more interest due to their toxicity [9,10,11,12]. Severe hepatotoxicity and numerous toxic effects including nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, reproductive toxicity and endocrine disruption have been reported for MCs [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Cylindrospermopsin (CYN) is a steady tricyclic alkaloid formed by a tricyclic guanidine moiety linked to hydroxy-methyl-uracil through a hydroxyl bridge [19]. CYN inhibits protein [20] and glutathione synthesis [21]. It is classified as a cytotoxin even though it can affect different organs [22]. It has also been shown to exhibit dermatoxic and neurotoxic activity, and CYN induces pro-genotoxicity via hepatic cytochrome P450-dependent mechanism [18,23,24,25,26,27]. Furthermore, these two cyanotoxins are also able to cause oxidative stress [28,29,30,31].

For both cyanotoxins, there is growing evidence that besides the above-mentioned toxicity, they can also have immunomodulatory potential acting in a dualistic way, inducing both immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive responses in the immune system [32]. Immunotoxicity could be defined as “any adverse effect on the components of and/or function of the immune system by a biological, chemical, or physical agent resulting from either direct or indirect actions and reflecting either permanent or reversible toxicity” [33]. The immune system is specialized in defense against pathogens, and it is composed of a collection of cells and tissues dispersed throughout the body [34]. This system is divided into two components closely connected with each other: innate and adaptive or acquired immunity. Innate immunity is possessed by all kinds of multi-cellular organisms; however, acquired immunity exists only in vertebrates [35]. The innate immune system is the first to respond to pathogens and does not retain memory of previous responses. It is mediated by cellular components such as granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils), macrophages, mast cells, dendritic cells and natural killer cells (NK). The cells involved in innate immunity recognize foreign substances such as bacteria with toll-like receptors (TLR), the receptors for innate immunity, and regulate the activation of other cells by the production of various cytokines, complement and acute phase proteins [35].

With respect to macrophages, they are important components of innate immunity against different pathogens and are involved in the pathology of numerous inflammatory diseases [36]. Macrophages stimulated by pro-inflammatory molecules release a variety of endogenous mediators such as nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6), among others, that trigger an inflammatory reaction. Activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), a dependent intracellular signaling pathway in macrophages, includes the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [37]. When MAPK is the dominant signal activated in TNF, this signal is connected to inflammation, apoptosis or necrosis [38]. Other important cellular component of the innate immune system are neutrophils. They exhibit potent antimicrobial responses through various intracellular and extracellular mechanisms including the release of granules containing cytotoxic and antimicrobial enzymes, phagocytosis and the production of ROS and NO [39].

If a pathogen persists, despite the innate immune defenses, the adaptive immune system is recruited. The adaptive immune system is highly specific to a particular antigen, can provide long-lasting immunity and needs memory B and T lymphocytes (B and T cells), immunoglobulins (Igs), and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [40,41]. The main role of B cells is to produce high affinity Igs against foreign antigens, and to act as a professional antigen presenting cell (pAPC) to present processed antigen to activate T cells. The T cell receptor (TCR) is always membrane bound and once stimulated via interaction with antigen presented by the pAPC, in the presence of co-stimulation, the T cell can be activated to function as a helper (CD4+) T cell, a regulatory (CD4+) T cell or a cytotoxic (CD8+) T cell [39,42].

Pioneer studies concerning the role of the immune system in the pathogenicity of cyanotoxins focused on MCs and reported that they could regulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1), TNF-α, and the induction of the synthesis of NO in macrophages [43,44,45]. It was observed that MCs had a clastogenic effect in human lymphocytes connected with chromosomal breakage in a dose-dependent manner [46]. Other approaches showed the apoptotic effect of cyanobacterial bloom extracts in rat hepatocytes and human lymphocytes [47], and demonstrated the potential genotoxic effect of these extracts on immunocytes, which was reflected by the DNA damage in human lymphocytes [48]. With respect to CYN, Terao et al. [49] described necrosis of lymphocytes of the thymus of mice giving a single dose of 0.2 mg/kg purified CYN intraperitoneally (i.p.). Similarly, degeneration and necrosis of cortical lymphocytes in the thymus and lympho-phagocytosis in rodents as experimental models were observed by Seawright et al. [50] and Shaw et al. [51]. Moreover, CYN can induce oxidative stress and a significant increase in the frequency of micronucleus (MN) in the presence of S9 fraction in human lymphocytes [26,52,53]. These processes can eventually lead to adverse responses in the immune system.

In recent decades, research on the potential impact of cyanotoxins on the immune system, especially in the case of MCs, has increased significantly. There are different studies in which cyanotoxins can impact both the function of blood cells of the immune system (such as macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes) [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61], and the production of ROS and NO [35,37,55,62,63,64,65,66]. Moreover, several authors have focused on the study of transcription factors and cytokine production [37,61,62,66,67,68,69,70]. Recently, immunological gene and protein expression, immunohistochemical analyses and immunofluorescence staining by exposure to MC-LR have been studied both in vitro [60,71] and in vivo [59,72,73,74].

In this regard, taking into account the growing occurrence of cyanobacterial toxins and therefore its potential increased exposure, the fact that immunotoxicity is not considered a primary toxicity mechanism of MCs and CYN, and that immune system alterations could lead to important consequences in the organisms, it is of high interest to gain a full picture about the toxicity of these two types of cyanotoxins on the immune system. Thus, the aim of this review was to gather the available information to date in the scientific literature on the topic, including potential mechanisms involved and identification of data gaps. The information used was compiled after an extensive search of different sources in the public domain (PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Google Scholar) considering reports published in all time ranges.

2. Microcystins

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 show the different in vitro and in vivo studies that deal with the immuno-toxic effects induced by MCs.

Table 1.

In vitro effects of MCs on the immune system.

Table 2.

In vivo effects of MCs on the immune system of aquatic organisms.

Table 3.

In vivo effects of MCs on the immune system of mammals.

2.1. In Vitro Studies

Most of the in vitro studies available in the scientific literature that focused on immuno-toxic effects of MCs (Table 1) have been performed with pure standards, especially in the case of MC-LR, the most frequently studied MC-congener. The exact mechanisms of immunotoxicity of MCs have not yet been fully elucidated. In this sense, the in vitro studies constitute an adequate and important tool that allows us to deepen our knowledge of MCs-immunotoxicity. Different cellular models have been employed so far to investigate MC-LR immunotoxicity, highlighting human lymphocytes i.e. [47,63,75,76] and neutrophils [53], as well as mammals’ macrophages. i.e. [43,62,68,77], because their results could be more representative of the effects and immuno-toxic mechanisms that may occur in humans. These reports evidenced the immunomodulatory potential of MC-LR. Thus, it decreased cell viability and induced cell death by apoptosis [47,76,78,79], altered the production of different cytokines or their mRNA expression [43,62,68,75,80,81,82,83], and induced a chemotactic effect [63,84].

Moreover, changes in inflammatory parameters have been reported not only in cells from the immune system but also in hepatic cells [81,82] and bovine Sertoli cells (from testis) [71,85].

Apart from MC-LR, other different MC-congeners have been investigated, such as MC-YR, [Asp3]-MC-LR, MC-RR, and MC-LA [55,63,77,79,80,86]. These reports did not show a clear differential response in comparison to MC-LR. Kujbida et al. [55] observed some different responses between MC-LR, -LA and -YR. Thus, human neutrophils’ viability was not altered by MC-YR treatment. Rat neutrophils also released significantly greater amounts of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-2αβ (CINC-2αβ), only after incubation with MC-LR. However, and for example, extracellular ROS levels in human and rat neutrophils were similarly altered by the three MCs. These authors concluded that hepatic neutrophil accumulation is further increased by MC-induced neutrophil-derived chemokine. On the contrary, Yea et al. [80] observed that concanavalin A (ConA)-induced lymphoproliferative response was decreased by MC-YR, but no significant effect was observed in the MC-LR treatment. Considering the importance that minority MC congeners are acquiring due to their occurrence and toxicity [11,12], and the interest shown by international authorities such as EFSA [5], additional focused studies dealing with immune responses would be of interest.

An even more limited number of studies employed cyanobacterial bloom samples or crude extracts [47,76]. Of these, only the second compared the effects of crude microcystin-containing extracts, purified microcystin-containing and non microcystin-containing extracts and indicated that the purified extract (with MC-LR, MC-RR and MC-YR) induced the highest cytotoxicity and genotoxicity on human lymphocytes, and that other compounds had an influence on the results. Toxic effects of cyanotoxin mixtures are also worthy of research as they represent a more realistic exposure scenario, and can show antagonistic, additive or potentiation responses [87,88,89,90,91].

There is also a certain number of studies that use fish cells as experimental models [79,92,93,94,95,96,97]. These studies also report similar responses to those shown by mammalian models (decreased cell viability, apoptosis, changes in respiratory burst activity, altered cytokine mRNA expression, etc.). There is a single in vitro study by Zhang et al. [97] performed in carp (C. auratus) lymphocytes that evaluated the efficacy of the chemo-protectant quercetin in regulating the MC-LR induced apoptosis. The protective effects of natural antioxidants on fish immunotoxicity have also been evidenced in vivo [98].

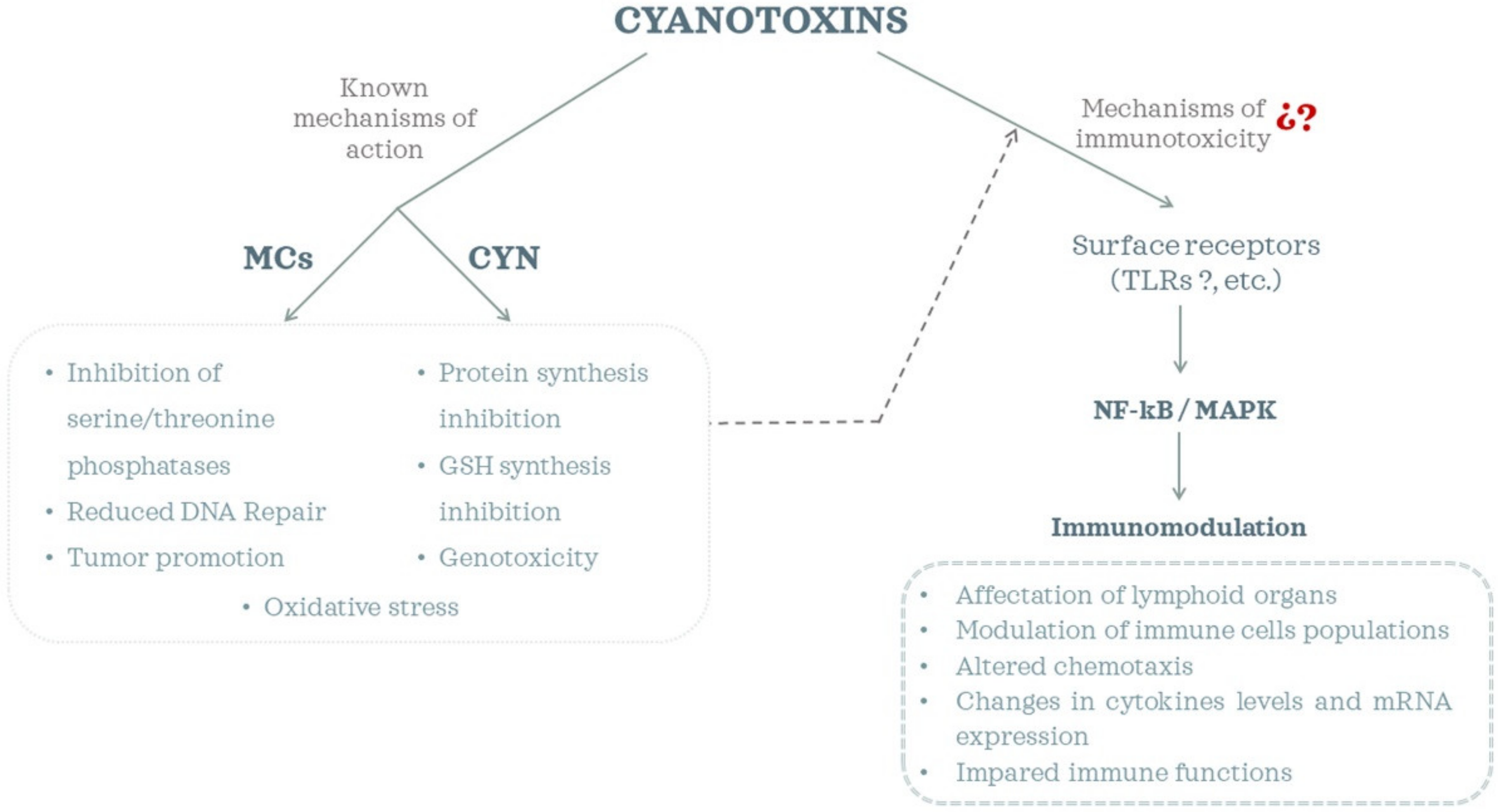

Taken together, most of these studies explored changes in immune parameters, but the molecular pathways involved are not yet totally elucidated (Figure 1). There are some reports that suggested that MC-LR induced a dysfunction of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways [82,83,85,97]. Inflammatory and immune responses are regulated by multiple signaling pathways, among which the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, which include the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways, are critical participants in cellular stress responses and modulate a variety of inflammatory responses [82,99,100]. Moreover, surface receptors (such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs)) have also been suggested to play a role in the observed immunomodulatory effects of MCs [71,83,85]. TLRs are known to transduce signals via adaptor proteins (e.g., MyD88), kinases (e.g., MAPKs, AKT) and transcription factors (e.g., NF-κB). However, recent studies by Hansen et al. [86] observed that MC-LR, -RR and -LA exhibited neither stimulatory nor inhibitory effects on cell lines that expressed specific TLRs, and they hypothesized that tested cyanobacterial toxins might initiate immune responses via NF-κB through interaction with other cell surface receptors. Therefore, more research efforts are still required to reveal the underlying mechanisms of cyanotoxin immunotoxicity.

Figure 1.

Cyanotoxins’ toxicity mechanisms and immunomodulatory effects.

2.2. In Vivo Studies

2.2.1. Aquatic Organisms

The immuno-toxic potential of cyanotoxins in fish is an issue of interest taking into account the number of studies available in the scientific literature (Table 2). Rymuszka et al. [102] have already reviewed the topic and pointed out that the immuno-modulative effects of cyanotoxins on fish could result in higher susceptibility to diseases. From this report, additional studies have been performed, with special focus on MC-LR. There is a single study that compares the immunotoxicity potential of MC-LR versus an extract of a cyanobacterial bloom containing a similar level of MCs [101]; it concluded that the extract had greater suppressive effects on immune cells. It is known that environmental samples may include additional bioactive compounds (i.e., oligopeptides such as micro-ginins or aeruginosins, lipopolysaccharides, polar alkaloid metabolites and other unidentified metabolites [103,104] that have an influence on the toxicity observed [105].

From the results compiled, it is evidenced that MCs are able to induce pathological lesions in lymphoid organs and cells [72,74,106,107,108]. Interestingly, the toxic effect is recovered with time. Thus, Wei et al. [109] found that damaged lymphocytes were almost unobserved in the spleen and pronephros after 21 days of a single exposure to 50 µg/kg MC-LR body weight (b.w.) i.p. injection in grass carp, showing the spleen to have a higher sensitivity.

Cytokines gene expression by RT-PCR is the parameter most frequently investigated in aquatic animals (fish and shrimps) i.e., [72,101,110,111,112]. All of these studies evidenced that the exposure to MCs (MC-LR) affect the function of the immune system, resulting in immunomodulation. Moreover, this effect is independent of the method of exposure (i.p. injection, immersion, diet). Several authors agreed on a dualistic response of the fish innate immune system. Thus, fish immunity tends to proceed toward the direction of an immuno-stimulative response at low MC concentrations but toward the trend of immunosuppressive answer at high MC concentrations [59,69,106].

Another interesting finding is that there are substances such as L-carnitine that when used as functional feed additive could significantly inhibit the progression of MC-LR immunotoxicity [98]. The efficacy of this chemo-protectant on cyanotoxin-induced oxidative stress and histopathological changes was already known [113,114], but this is the first report that evidenced a positive influence also on the immune system. As oxidative stress triggers inflammatory responses, it can be hypothesized that other chemo-protectants that have shown to reduce MC-induced oxidative damage in fish such as N-acetylcysteine, Trolox, etc., [115,116] could also ameliorate immunotoxicity.

Different authors have also shown that MC-LR can induce cross-generational immunotoxicity not only in fish [70] but also in other aquatic organisms such as prawns [117]. Thus, Lin et al. [70] observed that after exposure up to 10 µg/L MC-LR for 60 days in zebrafish (F0 generation) and with/without continued exposure of the embryos until 5 days postfertilization, the F1 generation showed an upregulation on innate immune-related genes (tlr4α, myd88, tnfα, il1β) as well as increased proinflammatory cytokine content (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6). Moreover, the inflammatory response was higher in embryos with a continued exposure. Similarly, Sun et al. [117] reported that F1 offspring prawns (Macrobrachium nipponense) showed, among other effects, downregulation of immunity molecules (lysozyme, lectin3) and increased expression of innate immune-related factors (TLR3, MyD88), despite not being treated with MC-LR. These results indicate that parental exposure of aquatic organisms could jeopardize the immune homeostasis and healthy growth of larvae.

Overall, aquatic organisms are at high risk of cyanobacterial toxin exposure, and the immune system has been revealed as an important target, apart from the well-known hepatotoxicity of MCs.

2.2.2. Mammals

Studies dealing with immunomodulatory effects of MCs on mammalian models are limited (Table 3). They have explored the effects of both bloom extracts containing MCs [54,67,119,120] and pure MCs, in this latter case restricted to MC-LR [60,61,73,121,122,123]. The preferred model is the mouse (70% of articles) followed by the rat (20%) and the rabbit (10%). Most used i.p. injection as the exposure route, and only three employed the oral route, two by drinking water [60,123] and a single one through the diet [120].

The research performed up to now has revealed that MCs impaired immune functions in different ways. Thus, a reduction of phagocytosis [54,122], changes in gene expression of different cytokines [67,73,123] and in their levels [61,73,119,122], modulation of cell populations [54,119,120], etc., have been reported (Figure 1). However, these effects appeared to depend on the doses or the method of exposure, etc., or to show variations in a transient manner. For example, Li et al. [121] observed severe damage in the spleen of Wistar rats exposed i.p., and a significant MC-LR accumulation in this organ. By contrast, Palikova et al. [120] reported no histological changes in the spleen or thymus of Wistar rats exposed through the diet. The compiled results also showed the importance of the immune system in the homeostasis of the whole organism, with effects not only in lymphoid organs but also in the reproductive system [60,73], bones [61], or jejunum [123].

Considering that the i.p. pathway is not the most relevant exposure route when considering potential effects in humans, a special focus on studies using the oral route is of interest. In this regard, Palikova et al. [120] performed a study in rats fed for 28 days with a diet containing fish meat with/without MCs and complex toxic biomass. They pointed out that toxic effects were less pronounced than expected (actually, no significant histological changes were observed in the spleen or thymus), and they suggested that other compounds of the diet could influence MC availability or have a positive effects on faster elimination. In any case, diets enriched with MCs (700 and 5000 mg total MCs per kg of feed, wet weight (w.w.)) influenced preferably innate parts of the immune system represented by NK cells and gamma-delta T cells, which play a role as a bridge between adaptive and innate immune response. On the other hand, rats fed with fish from a locality with heavy cyanobacterial bloom mainly showed changes in proportions of Th, Tc and double-positive T cells which represent cells of the adaptive immune system. The level of MCs in this type of diet was very low, so these effects were probably caused by the presence of other substances contained in the bloom.

Chen et al. [60] and Cao et al. [123] used mice exposed to MC-LR through drinking water but selected a different experimental design and focused on different target organs. Thus, they exposed mice to a concentration range of 1–30 μg/L MC-LR for 180 consecutive days and explored the outcome in the testes. They found that MC-LR treatment induced significant enrichment of macrophages in the testes and that these macrophages promoted Leydig cell apoptosis. Additionally, expression levels of macrophage activation marker protein TNF-α in the testes were significantly up-regulated. Similarly, mRNA levels of IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), Axl, and MerTK (tyrosine kinase receptors) were also increased at different concentrations. Cao et al. [123] focused their study on the jejunal microstructure and the expression level of inflammatory-related factors in this organ. They used mice exposed to 1–120 μg/L MC-LR for 6 months and observed an alteration in the expression levels of different inflammation-related factors depending on the concentration. Interestingly, these authors showed that even at 1 μg/L MC-LR, which is the current guidance value in water [124], MC-LR was able to alter immunologic parameters in mice.

Changes in hematological parameters, activation of neutrophils and macrophages, and alteration and activation of lymphocytes, were the specific effects on immune functions identified for MCs in mammals by Lone et al. [125]. As reports included in Table 3 evidence, little progress has been made so far in trying to decipher MCs’ immunotoxicity.

Thus, further research is required to understand the immunomodulatory effects of cyanotoxins. Particularly, mammalian studies with relevant exposure scenarios would be welcome to try to interpolate the potential consequences in humans.

3. Cylindrospermopsin

Among the effects induced by CYN, the toxin may also exhibit immunotoxicity [126], although studies focused on this pathogenicity are very scarce [25] (Table 4). The first work in which pure CYN was classified as a potential immuno-toxicant was reported in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. In this experimental model, CYN induced a significant inhibition of their proliferation [53]. Previously, Seawright et al. [50] had already provided hints of the immunomodulatory effects of CYN as they observed histopathological alterations (atrophy) in the lymphoid organs (thymus and spleen) in mice orally exposed to a C. raciborskii culture. This is actually the only report of CYN immunotoxicity in vivo.

Table 4.

Effects of CYN on the immune system.

Poniedzialek et al., have performed an extensive investigation of CYN effects on human immune cells, mainly lymphocytes [53,56,57,58,127]. These studies showed that CYN inhibited cell proliferation [53,56,58], reduced viability, altered cell cycle [56], and induced changes in oxidative stress parameters in lymphocytes [127]. Moreover, it decreased the oxidative burst capacity of neutrophils [57], cells that play an important role in non-specific immune response and organism resistance, specifically in anti-bacterial resistance. These authors also demonstrated that both CYN and non-CYN producing C. raciborskii extracts can exhibit immunomodulatory potencies. Thus, human lymphocytes in general were more resistant than neutrophils after exposure to cell-free extracts. Nevertheless, their short-term exposure resulted in a significantly increased rate of apoptosis and necrosis, whereas CYN did not induce similar effects. The effect of the non-CYN extracts on T- lymphocyte proliferation was not as pronounced as for CYN, suggesting that the cells can partially overcome the toxic effects induced by C. raciborskii exudates, or that the metabolites are degraded due to their lower stability than that of CYN.

Apart from human cells, pure CYN was reported to impair and decrease the function of phagocytic cells in the CLC cell line from fish (Cyprinus carpio) [128] and in phagocytic cells isolated from head kidneys of the same fish species. In this model system, cytotoxicity was observed, as well as a decreased phagocytic activity, changes in actin cytoskeletal structures, production of ROS and NOS, and altered expression of specific genes of proinflammatory cytokines [66].

Moosova et al. [37] investigated whether CYN, either alone or in combination with the immunomodulatory agent lipopolysaccharide (LPS), could affect murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, the model of mammalian innate immunity. They found that CYN induced the TNF-α production and pro-inflammatory phenotype in macrophages and also increased ROS that trigger an inflammatory response. Moreover, it can synergistically potentiate the stimulation of macrophages by LPS. It is known that LPS stimulates the phagocytic cells via Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), resulting in production of proinflammatory cytokines as a result of NF-κB and MAPK activation. It has also been suggested that cyanotoxins interact with TLRs, key triggers of inflammatory processes [37,77,83]. However, recently Hansen et al. [86] found that CYN (and other cyanotoxins) did not directly interact with human TLRs in either an agonistic or antagonistic manner. Thus, reports of cyanotoxin-induced NF-κB responses likely occur through different surface receptors.

As has been evidenced, the information available regarding the immunomodulatory effects of CYN is very limited, even more sp the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms involved (Figure 1). Further research is required on this issue to develop effective prevention and intervention strategies against CYN toxicosis.

4. Final Considerations

Cyanotoxins (MCs and CYN) have been shown to induce immunomodulatory effects, with impact on both innate and adaptive immunity. They induced pathological alterations in immune cells and organs, altered immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, etc.), changed levels and mRNA expression of cytokines, and altered chemotaxis, among other effects. However, the mechanisms underlying these responses are far from being well understood. This is due to the still limited number of studies that focus on this topic, particularly for CYN. Different studies have proposed a TLR dependent NF-κB activation by MCs. TLRs are known to transduce signals via adaptor proteins (e.g., MyD88), kinases (e.g., MAPKs, AKT) and transcription factors (e.g., NF-κB). However, recently Hansen et al. [86] reported that neither MCs nor CYN interacted with human TLRs in either an agonistic or antagonistic manner. They proposed that other cell surface receptors such as peptidoglycan recognition proteins, scavenger receptors, receptor tyrosine kinases or cytokine receptors could be involved. Moreover, there are other receptors involved in the dysfunction of the immune system. This is the case with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) that belong to the nuclear steroid receptor superfamily [129], although the interaction of cyanotoxins with these has not been explored. Hansen et al. [86] also pointed out that organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs) could potentially activate NF-κB in a non-specific manner. OATPs are a well-known family of membrane transporters used by MCs to enter the cell. In this regard, different studies have reported the presence of OATPs in lymphoid organs such as spleen and thymus [130], immune cells such as monocytes and macrophages [131], lymphocytes [132], etc. However, Adamovsky et al. [83] described that macrophages do not express MC-related OATPs (1a2, 1b1, 1b3, 1c1), but do express others with unknown affinities to MCs.

Thus, as has been evidenced, there are many open questions in relation to cyanotoxins immunotoxicity. Taking into account the pivotal role of the immune system in the homeostasis of all organisms, further research is required to gain knowledge on this important issue. The application of omics, the use of in vitro methods for mechanistic research exploring the potential pathways involved, and in vivo experiments with realistic exposure scenarios could contribute to a better understanding of the complex cyanotoxin pathology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.; methodology, M.d.M.B.-G., L.D.-Q., M.P., A.M.C. and A.J.; investigation, M.d.M.B.-G., L.D.-Q.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.-Q., M.P., A.M.C., and A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.M.C., A.J.; visualization, A.M.C. and A.J.; supervision, A.M.C. and A.J.; project administration, A.M.C. and A.J.; funding acquisition, A.M.C. and A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the SPANISH MINISTERIO DE CIENCIA E INNOVACIÓN, project number PID2019-104890RB-I00 MICINN). The FPI grant number BES-2016-078773 awarded to Leticia Diez-Quijada Jiménez was funded by Spanish Ministerio de Economia, Industria y Competitividad. The Postdoctoral Bridge Contract of L.D-Q was funded by the VI PPIT-US.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data achieved from this review.

Acknowledgments

Leticia Diez-Quijada Jiménez thanks for the grant FPI (BES-2016–078773) to the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad and the VI PPIT-US for the grant Postdoctoral Bridge Contract. To the MICINN for the PID2019-104890RB-I00 project funds. Also authors would like to acknowledge networking support by the Marie Slodowska-Curie grant agreement Nº 823860.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, I.-S.; Zimba, P.V. Cyanobacterial bioactive metabolites—A review of their chemistry and Biology. Harmful Algae 2019, 83, 42–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, F.M.; Manganelli, M.; Vichi, S.; Stefanelli, M.; Scardala, S.; Testai, E.; Funari, E. Cyanotoxins: Producing organisms, occurrence, toxicity, mechanism of action and human health toxicological risk evaluation. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 1049–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bormans, M.; Amzil, Z.; Mineaud, E.; Brient, L.; Savar, V.; Robert, E.; Lance, E. Demonstrated transfer of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins along a freshwater-marine continuum in France. Harmful Algae 2019, 87, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganelli, M.; Scardala, S.; Stefanelli, M.; Palazzo, F.; Funari, E.; Vichi, S.; Buratti, F.M.; Testai, E. Emerging health issues of cyanobacterial blooms. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita. 2012, 48, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testai, E.; Buratti, F.M.; Funari, E.; Manganelli, M.; Vichi, S.; Arnich, A.; Biré, R.; Fessard, V.; Sialehaamoa, A. Review and analysis of occurrence, exposure and toxicity of cyanobacteria toxins in food. EFSA Support. Publ. 2016, 13, 998E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, A.A.; Chernoff, N.; Sinclair, J.L.; Hill, D.; Diggs, D.L.; Lynch, A.T. Introduction to Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins. In Water Treatment for Purification from Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins; Hiskia, A.E., Triantis, T.M., Antoniou, M.G., Kaloudis, T., Dionysiou, D.D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–35. ISBN 978-1-118-92861-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, W.W.; Boyer, G.L. Health impacts from cyanobacteria harmful algae blooms: Implications for the North American Great Lakes. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaïcha, N.; Miles, C.O.; Beach, D.G.; Labidi, Z.; Djabri, A.; Benayache, N.Y.; Nguyen-Quang, T. Structural Diversity, Characterization and Toxicology of Microcystins. Toxins 2019, 11, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, S.; Jos, Á.; Zurita, J.L.; Salguero, M.; Cameán, A.M.; Repetto, G. Acute and subacute toxic effects produced by microcystin-YR on the fish cell lines RTG-2 and PLHC-1. Toxicol. Vitr. 2007, 21, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto, M.; Pichardo, S.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. Comparison of the toxicity induced by microcystin-RR and microcystin-YR in differentiated and undifferentiated Caco-2 cells. Toxicon 2009, 54, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Quijada, L.; Puerto, M.; Gutiérrez-Praena, D.; Llana-Ruiz-Cabello, M.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. Microcystin-RR: Occurrence, content in water and food and toxicological studies. A review. Environ. Res. 2019, 168, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Quijada, L.; Prieto, A.I.; Guzmán-Guillén, R.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. Occurrence and toxicity of microcystin congeners other than MC-LR and MC-RR: A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xie, P.; Chen, J.; Liang, G. Distribution of microcystins in various organs (heart, liver, intestine, gonad, brain, kidney and lung) of Wistar rat via intravenous injection. Toxicon 2008, 52, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yan, W.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Yu, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, G. Microcystin-LR exposure induces developmental neurotoxicity in zebrafish embryo. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 213, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Yan, W.; Wu, Q.; Liu, C.; Gong, X.; Hung, T.-C.; Li, G. Parental exposure to microcystin-LR induced thyroid endocrine disruption in zebrafish offspring, a transgenerational toxicity. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 230, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Meng, F.; Yao, L. Hepatotoxicity and immunotoxicity of MC-LR on silver carp. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 169, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Wu, Q.; Liu, C.; Shen, J.Z.; Yan, W. Microcystin-LR exposure induced nephrotoxicity by triggering apoptosis in female zebrafish. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, M.G.; Gutiérrez-Praena, D.; Prieto, A.I.; Guzmán-Guillén, R.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. Neurotoxicity induced by microcystins and cylindrospermopsin: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, I.; Moore, R.E.; Runnegar, M.T.C. Cylindrospermopsin, a potent hepatotoxin from the blue-green alga Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 7941–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froscio, S.M.; Humpage, A.R.; Burcham, P.C.; Falconer, I.R. Cylindrospermopsin-induced protein synthesis inhibition and its dissociation from acute toxicity in mouse hepatocytes. Environ. Toxicol. 2003, 18, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnegar, M.T.; Kong, S.-M.; Zhong, Y.-Z.; Lu, S.C. Inhibition of reduced glutathione synthesis by cyanobacterial alkaloid cylindrospermopsin in cultured rat hepatocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995, 49, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, P.R.; Runnegar, M.T.C.; Jackson, A.R.B.; Falconer, I.R. Severe hepatotoxicity caused by the tropical cyanobacterium (blue-green alga) Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Woloszynska) Seenaya and Subba Raju isolated from a domestic water supply reservoir. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1985, 50, 1292–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpage, A.R.; Fenech, M.; Thomas, P.; Falconer, I.R. Micronucleus induction and chromosome loss in transformed human white cells indicate clastogenic and aneugenic action of the cyanobacterial toxin cylindrospermopsin. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2000, 472, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.; Mihali, T.; Moffitt, M.; Kellmann, R.; Neilan, B. On the Chemistry, Toxicology and Genetics of the Cyanobacterial Toxins, Microcystin, Nodularin, Saxitoxin and Cylindrospermosin. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1650–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, S.; Cameán, A.M.; Jos, Á. In vitro toxicological assessment of cylindropermopsin: A review. Toxins 2017, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puerto, M.; Prieto, A.I.; Maisanaba, S.; Gutiérrez-Praena, D.; Mellado-García, P.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. Mutagenic and genotoxic potential of pure Cylindrospermopsin by a battery of in vitro test. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 121, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Quijada, L.; Llana-Ruiz-Cabello, M.; Cătunescu, G.M.; Puerto, M.; Moyano, R.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. In vivo genotoxicity evaluation of cylindrospermopsin in rats using a combined micronucleus and comet assay. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 132, 110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puerto, M.; Pichardo, S.; Jos, Á.; Prieto, A.I.; Sevilla, E.; Frías, J.E.; Cameán, A.M. Differential oxidative stress responses to pure Microcystin-LR and Microcystin-containing and non-containing cyanobacterial crude extracts on Caco-2 cells. Toxicon 2010, 55, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto, M.; Jos, Á.; Pichardo, S.; Gutiérrez-Praena, D.; Cameán, A.M. Acute effects of pure cylindrospermopsin on the activity and transcription of antioxidant enzymes in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exposed by gavage. Ecotoxicology 2011, 20, 1852–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto, M.; Jos, Á.; Pichardo, S.; Moyano, R.; Blanco, A.; Cameán, A.M. Acute exposure to pure cylindrospermopsin results in oxidative stress and pathological alterations in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Environ. Toxicol. 2014, 29, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, S. Microcystin-LR induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in alveolar type II epithelial cells of ICR mice in vitro. Toxicon 2020, 174, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierosławska, A. Immunotoxic, genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of cyanotoxins. Centr. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 35, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, D.M. US FDA “Redbook II” Immunotoxicity Testing Guidelines and Research in Immunotoxicity Evaluations of Food Chemicals and New Food Proteins. Toxicol. Pathol. 2000, 28, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.A. Cell Biology of the Immune System. In Goodman’s Medical Cell Biology, 4th ed.; Goodman, S.R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 337–360. ISBN 9780128179277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohchi, C.; Inagawa, H.; Nishizawa, T.; Soma, G.-I. ROS and Innate Immunity. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 817–821. [Google Scholar]

- Jou, I.-M.; Lin, C.-F.; Tsai, K.-J.; Wei, S.-J. Macrophage-Mediated Inflammatory Disorders. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 316482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosova, Z.; Pekarova, M.; Sindlerova, L.S.; Vasicek, O.; Kubala, L.; Blaha, L.; Adamovsky, O. Immunomodulatory effects of cyanobacterial toxin cylindrospermopsin on innate immune cells. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Goeddel, D.V.G. TNF-R1 signaling: A beautiful pathway. Science 2002, 296, 1634–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C.; Rise, M.L.; Christian, S.L. A Comparison of the Innate and Adaptive Immune Systems in Cartilaginous Fish, Ray-Finned Fish, and Lobe-Finned Fish. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flajnik, M.F.; Kasahara, M. Origin and evolution of the adaptive immune system: Genetic events and selective pressures. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuper, C.F.; Ruehl-Fehlert, C.; Elmore, S.A.; Parker, G.A. Immune System. In Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, 3rd ed.; Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume III, pp. 1795–1862. ISBN 978-0-12-415759-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. The Adaptive Immune System. In Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th ed.; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 10:0-8153-4072-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, M.; Nakano, Y.; Sato-Taki, T.; Mori, N.; Kojima, M.; Ohtake, A.; Shirai, M. Toxicity of Microcystis aeruginosa K-139 strain. Microbiol. Immunol. 1989, 33, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahan, K.; Sheikh, F.G.; Namboodiri, A.M.S.; Singh, I. Inhibitors of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A differentially regulate the expression of inducible nitric-oxide synthase in rat astrocytes and macrophages. J. Bio. Chem. 1998, 273, 12219–12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, M.F.G.; Sidrim, J.J.C.; Soares, A.M.; Jiménez, G.C.; Guerrant, R.L.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Lima, A.A.M. Supernatants from Macrophages Stimulated with Microcystin-LR Induce Electrogenic Intestinal Response in Rabbit Ileum. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000, 87, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repavich, W.M.; Sonzogni, W.C.; Standridge, J.H.; Wedepohl, R.E.; Meisner, L.F. Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) in wisconsin waters: Acute and chronic toxicity. Water Res. 1990, 24, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiewicz, J.; Tarczynska, M.; Fladmark, K.E.; Doskeland, S.O.; Walter, Z.; Zalewski, M. Apoptotic effect of cyanobacterial extract on rat hepatocytes and human lymphocytes. Environ. Toxicol. 2001, 16, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankiewicz, J.; Walter, Z.; Tarczynska, M.; Palyvoda, O.; Wojtysiak-Staniaszczyk, M.; Zalewski, M. Genotoxicity of cyanobacterial extracts containing microcystins from Polish water reservoirs as determined by SOS chromotest and comet assay. Environ. Toxicol. 2002, 17, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terao, K.; Ohmori, S.; Igarashi, K.; Ohtani, I.; Watanabe, M.F.; Harada, K.I.; Ito, E.; Watanabe, M. Electron microscopic studies on experimental poisoning in mice induced by cylindrospermopsin isolated from blue-green alga Umezakia natans. Toxicon 1994, 32, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, A.A.; Nolan, C.C.; Shaw, G.R.; Chiswell, R.K.; Norris, R.L.; Moore, M.R.; Smith, M.J. The oral toxicity for mice of the tropical cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Wolonszynska). Environ. Toxicol. 1999, 14, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.R.; Seawright, A.A.; Moore, M.R.; Lam, P.K.S. Cylindrospermopsin, a cyanobacterial alkaloid: Evaluation of its toxicological activity. Ther. Drug Monit. 2000, 22, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žegura, B.; Gajski, G.; Štraser, A.; Garaj-Vrhovac, V. Cylindrospermopsin induced DNA damage and alteration in the expression of genes involved in the response to DNA damage, apoptosis and oxidative stress. Toxicon 2011, 58, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniedziałek, B.; Rzymski, P.; Wiktorowicz, K. First report of cylindrospermopsin effect on human peripheral blood lymphocytes proliferation in vitro. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 37, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.P.; Zhao, S.W.; Zheng, W.J.; Hua, Z.C.; Shi, Q.; Liu, Z.T. Effects of cyanobacteria bloom extract on some parameters of immune function in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 143, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujbida, P.; Hatanaka, E.; Campa, A.; Curi, R.; Farsky, S.H.P.; Pinto, E. Analysis of chemokines and reactive oxygen species formation by rat and human neutrophils induced by microcystin-LA, -YR and -LR. Toxicon 2008, 51, 1274–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniedziałek, B.; Rzymski, P.; Wiktorowicz, K. Toxicity of cylindrospermopsin in human lymphocytes: Proliferation, viability and cell cycle studies. Toxicol. Vitr. 2014, 28, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniedziałek, B.; Rzymski, P.; Karczewski, J. Cylindrospermopsin decreases the oxidative burst capacity of human neutrophils. Toxicon 2014, 87, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniedziałek, B.; Rzymski, P.; Kokociński, M.; Karczewski, J. Toxic potencies of metabolite(s) of non-cylindrospermopsin producing Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii isolated from temperate zone in human white cells. Chemosphere 2015, 120, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Hou, J.; Guo, H.; Qiu, Y.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Tang, R. Dualistic immunomodulation of sub-chronic microcystin-LR exposure on the innate-immune defense system in male zebrafish. Chemosphere 2017, 183, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Han, X. Microcystin-leucine arginine mediates apoptosis and engulfment of Leydig cell by testicular macrophages resulting in reduced serum testosterone levels. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 199, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, H.Y.; Lone, Y.; Koiri, R.K.; Mishra, P.K.; Srivastava, R.K. Microcystin-leucine arginine (MC-LR) induces bone loss and impairs bone micro-architecture by modulating host immunity in mice: Implications for bone health. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Q.; Hua, Z.; Shen, P. Analysis of immunomodulating nitric oxide, iNOS and cytokines mRNA in mouse macrophages induced by microcystin-LR. Toxicology 2004, 197, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujbida, P.; Hatanaka, E.; Campa, A.; Colepicolo, P.; Pinto, E. Effects of microcystins on human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 341, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.N.; Al-Omran, A.; Parvathy, S.S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2007, 15, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieroslawska, A.; Rymuszka, A.; Adaszek, L. Effects of cylindrospermopsin on the phagocytic cells of the common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Cui, J.; Zhang, J.; Kong, F.X.; Hua, Z.C.; Shen, P.P. Expression modulation of multiple cytokines in vivo by cyanobacteria blooms extract from taihu lake, China. Toxicon 2004, 44, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Shen, P.; Zhang, J.; Hua, Z. Effects of Microcystin-LR on Patterns of iNOS and Cytokine mRNA Expression in Macrophages In vitro. Environ. Toxicol. 2005, 20, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, G.; Lu, T.; Sun, L.; Pan, X. Effects of different concentrations of Microcystis aeruginosa on the intestinal microbiota and immunity of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2019, 214, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, D.; Tang, R. Parental Transfer of Microcystin-LR-Induced Innate Immune Dysfunction of Zebrafish: A Cross-Generational Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, E.O.; Adeniran, S.O.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, G. Pharmacological inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB with TLR4-IN-C34 attenuated microcystin-leucine arginine toxicity in bovine Sertoli cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Jin, J.; Kawan, A.; Zhang, X. Pathological damage and immunomodulatory effects of zebrafish exposed to microcystin-LR. Toxicon 2016, 118, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Li, D.; Han, X. Microcystin-leucine arginine exhibits immunomodulatory roles in testicular cells resulting in orchitis. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, D.; Tang, R. Waterborne microcystin-LR exposure induced chronic inflammatory response via MyD88-dependent toll-like receptor signaling pathway in male zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankoff, A.; Carmichael, W.W.; Grasman, K.A.; Yuan, M. The uptake kinetics and immunotoxic effects of microcystin-LR in human and chicken peripheral blood lymphocytes in vitro. Toxicology 2004, 204, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankiewicz-Boczek, J.; Palus, J.; Gagala, I.; Izydorczyk, K.; Jurczak, T.; Dziubałtowska, E.; Stepnik, M.; Arkusz, J.; Komorowska, M.; Skowron, A.; et al. Effects of microcystins-containing cyanobacteria from a temperate ecosystem on human lymphocytes culture and their potential for adverse human health effects. Harmful Algae 2011, 10, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosova, Z.; Hrouzek, P.; Kapuscik, A.; Blaha, L.; Adamovsky, O. Immunomodulatory effects of selected cyanobacterial peptides in vitro. Toxicon 2018, 149, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teneva, I.; Mladenov, R.; Popov, N.; Dzhambazov, B. Cytotoxicity and Apoptotic Effects of Microcystin-LR and Anatoxin-a in Mouse Lymphocytes. Folia Biol. 2005, 51, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. Sensitive apoptosis induced by microcystins in the crucian carp (Carassius auratus) lymphocytes in vitro. Toxicol. Vitr. 2006, 20, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yea, S.S.; Kim, H.M.; Oh, H.-M.; Paik, K.-H.; Yang, K.-H. Microcystin-induced down-regulation of lymphocyte functions through reduced IL-2 mRNA stability. Toxicol. Lett. 2001, 122, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, V.; Meili, N.; Fent, K. Microcystin-LR induces endoplasmatic reticulum stress and leads to induction of NFκB, interferon-alpha, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 3378–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Xia, Z. Microcystin-LR exhibits immunomodulatory role in mouse primary hepatocytes through activation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 136, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovsky, O.; Moosova, Z.; Pekarova, M.; Basu, A.; Babica, P.; Sindlerova, L.S.; Kubala, L.; Blaha, L. Immunomodulatory potency of microcystin, an important water-polluting cyanobacterial toxin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12457–12464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.; Macia, M.; Padilla, C.; Del Campo, F.F. Modulation of Human Polymorphonuclear Leukocyte Adherence by Cyanopeptide Toxins. Environ. Res. 2000, 84, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, E.O.; Chen, W.; Machebe, N.S.; Xue, W.; Hao, W.; Adeniran, S.O.; Han, Z.; Peng, Z.; Guixue, Z. Microcystin-leucine arginine (MC-LR) induced inflammatory response in bovine sertoli cell via TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 63, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.D.; Loftin, K.A.; Laughrey, Z.; Adamovsky, O. Neither microcystin, nor nodularin, nor cylindrospermopsin directly interact with human toll-like receptors. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Praena, D.; Guzmán-Guillén, R.; Pichardo, S.; Moreno, F.J.; Vasconcelos, V.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. Cytotoxic and morphological effects of microcystin-LR, cylindrospermopsin, and their combinations on the human hepatic cell line HepG2. Environ. Toxicol. 2018, 34, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinojosa, M.G.; Prieto, A.I.; Gutiérrez-Praena, D.; Moreno, F.J.; Cameán, A.M.; Jos, Á. Neurotoxic assessment of Microcystin-LR, cylindrospermopsin and their combination on the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line. Chemosphere 2019, 224, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Quijada, L.; Prieto, A.I.; Puerto, M.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. In vitro Mutagenic and Genotoxic Assessment of a Mixture of the Cyanotoxins Microcystin-LR and Cylindrospermopsin. Toxins 2019, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Quijada, L.; Hercog, K.; Štampar, M.; Filipič, M.; Cameán, A.M.; Jos, Á.; Žegura, B. Genotoxic Effects of Cylindrospermopsin, Microcystin-LR and Their Binary Mixture in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HepG2) Cell Line. Toxins 2020, 12, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Quijada, L.; Medrano-Padial, C.; Llana-Ruiz-Cabello, M.; Cătunescu, G.M.; Moyano, R.; Risalde, M.A.; Cameán, A.M.; Jos, Á. Cylindrospermopsin-Microcystin-LR Combinations May Induce Genotoxic and Histopathological Damage in Rats. Toxins 2020, 12, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rymuszka, A.; Sieroslawska, A.; Bownik, A.; Skowronski, T. In vitro effects of pure microcystin-LR on the lymphocyte proliferation in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007, 22, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieroslawska, A.; Rymuszka, A.; Bownik, A.; Skowronski, T. The influence of microcystin-LR on fish phagocytic cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2007, 26, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rymuszka, A.; Sieroslawska, A.; Bownik, A.; Skowronski, T. Microcystin-LR modulates selected immune parameters and induces necrosis/apoptosis of carp leucocytes. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymuszka, A. Microcystin-LR induces cytotoxicity and affects carp immune cells by impairment of their phagocytosis and the organization of the cytoskeleton. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2013, 33, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rymuszka, A.; Adaszek, L. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression in carp blood and head kidney leukocytes exposed to cyanotoxin stress—An in vitro study. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012, 33, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Fang, W.; Wang, D. Regulatory effect of quercetin on hazardous microcystin-LR-induced apoptosis of Carassius auratus lymphocytes in vitro. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 37, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-M.; Guo, G.-L.; Sun, L.; Yang, Q.-S.; Wang, G.-Q.; Zhang, D.-M. Modulatory role of L-carnitine against microcystin-LR-induced immunotoxicity and oxidative stress in common carp. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, G.L.; Lapadat, R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 2002, 298, 1911–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiDonato, J.A.; Mercurio, F.; Karin, M. NF-κB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 246, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymuszka, A.; Adaszek, L. Cytotoxic effects and changes in cytokine gene expression induced by microcystin-containing extract in fish immune cells- An in vitro and in vivo study. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymuszka, A.; Sieroslawska, A.; Bownik, A.; Skowronski, T. Immunotoxic potential of cyanotoxins on the immune system of fish. Centr. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 33, 150–152. [Google Scholar]

- Smutná, M.; Babica, P.; Jarque, S.; Hilscherová, K.; Maršálek, B.; Haeba, M.; Bláha, L. Acute, chronic and reproductive toxicity of complex cyanobacterial blooms in Daphnia magna and the role of microcystins. Toxicon 2014, 79, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujvárosi, A.Z.; Hercog, K.; Riba, M.; Gonda, S.; Filipič, M.; Vasas, G.; Žegura, B. The cyanobacterial oligopeptides microginins induce DNA damage in the human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell line. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, I.R. Cyanobacterial toxins present in Microcystis aeruginosa extracts—More than microcystins! Toxicon 2007, 50, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X. Effect of cyanobacteria on immune function of crucian carp (Carassius auratus) via chronic exposure in diet. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.L.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, S.; Wu, H.; Ruan, J.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Q.; Zhong, Q. Transcriptome analysis of grass carp provides insights into the immune-related genes and pathways in response to MC-LR induction. Aquaculture 2018, 488, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Song, T.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, L.; Yang, P.; Zhang, X. Effects of dietary toxic cyanobacteria and ammonia exposure on immune function of blunt snout bream (Megalabrama amblycephala). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 78, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.L.; Sun, B.J.; Nie, P. Ultrastructural alteration of lymphocytes in spleen and pronephros of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) experimentally exposed to microcystin-LR. Aquaculture 2008, 280, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Sun, B.; Chang, M.X.; Liu, Y.; Nie, P. Effects of cyanobacterial toxin microcystin-LR on the transcription levels of immune-related genes in grass carp Ctenopharyngodon Idella. Environ. Biol. Fish 2009, 85, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cai, Y.; Xie, P.; Li, G.; Hao, L.; Xiong, Q. Identification and Expression Profiles of IL-8 in Bighead Carp (Aristichthys nobilis) in Response to Microcystin-LR. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2013, 65, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zuo, H.; Yang, L.; He, J.-H.; Niu, S.; Weng, S.; He, J.; Xu, X. Long-term influence of cyanobacterial bloom on the immune system of Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 61, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán Guillén, R.; Prieto, A.I.; Vazquez, C.M.; Vasconcelos, V.; Cameán, A.M. The Protective Role of L-Carnitine against Cylindrospermopsin-Induced Oxidative Stress in Tilapia Fish (Orechromis Niloticus). Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 132–133, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán Guillén, R.; Prieto Ortega, A.I.; Moyano, R.; Blanco, A.; Vasconcelos, V.; Cameán, A.M. Dietary l-carnitine prevents histopathological changes in tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) exposed to cylindrospermopsin. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto, M.; Prieto, A.I.; Pichardo, S.; Moreno, I.; Jos, Á.; Moyano, R.; Cameán, A.M. Effects of dietary N-Acetylcysteine on the oxidative stress induced in Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) exposed to a microcystin-producing cyanobacterial water bloom. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, A.I.; Jos, Á.; Pichardo, S.; Moreno, I.; de Sotomayor, M.Á.; Moyano, R.; Blanco, A.; Cameán, A.M. Time-dependent protective efficacy of Trolox (vitamin E analog) against microcystin-induced toxicity in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Environ. Toxicol. 2009, 24, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Zheng, C.; Shi, X. Effect of paternal exposure to microcystin-LR on testicular dysfunction, reproduction, and offspring immune response in the oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense). Aquaculture 2021, 534, 736332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, B.; Wu, H.; Nie, P. Effects of pure microcystin-LR on the transcription of immune related genes and heat shock proteins in larval stage of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquaculture 2009, 289, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Xie, P.; Zhang, X.; Tang, R.; Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Li, L. In vivo Studies on the Immunotoxic Effects of Microcystins on Rabbit. Environ. Toxicol. 2010, 27, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palikova, M.; Ondrackova, P.; Mares, J.; Adamovsky, O.; Pikula, J.; Kohoutek, J.; Navratil, S.; Blaha, L.; Kopp, R. In vivo effects of microcystins and complex cyanobacterial biomass on rats (Rattus norvegicus var. alba): Changes in immunological and haematological parameters. Toxicon 2013, 73, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yan, W.; Qiao, Q.; Chen, J.; Cai, F.; He, Y.; Zhang, X. Global effects of subchronic treatment of microcystin-LR on rat splenetic protein levels. J. Proteom. 2012, 77, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Ye, X.; Zhong, Q.; Gu, K. Comparison of response indices to toxic microcystin-LR in blood of mice. Chemosphere 2013, 92, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Huang, F.; Massey, I.Y.; Wen, C.; Zheng, S.; Xu, S.; Yang, F. Effects of Microcystin-LR on the microstructure and inflammation-related factors of jejunum in mice. Toxins 2019, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cyanobacterial Toxins: Microcystins. Background Document for Development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality and Guidelines for Safe Recreational Water Environments; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338066 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Lone, Y.; Bhide, M.; Koiri, R.K. Microcystin-LR Induced Immunotoxicity in Mammals. J. Toxicol. 2016, 2016, 8048125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, G.; Chen, Y.; Jia, N.; Li, R. Four decades of progress in cylindrospermopsin research: The ins and outs of a potent cyanotoxin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poniedziałek, B.; Rzymski, P.; Karczewski, J. The role of the enzymatic antioxidant system in cylindrospermopsin-induced toxicity in human lymphocytes. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015, 29, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieroslawska, A.; Rymuszka, A. Effects of cylindrospermopsin on a common carp leucocyte cell line. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Young, H.A. PPAR and immune system--what do we know? Int. Immunopharmacol. 2002, 2, 1029–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Tomita, H.; Suzuki, T.; Onogawa, T.; Sato, T.; Mizutamari, H.; Mikkaichi, T.; Nishio, T.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Distribution of Rat Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide-E (oatp-E) in the Rat Eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 4877–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moreau, A.; Le Vee, M.; Jouan, E.; Parmentier, Y.; Fardel, O. Drug transporter expression in human macrophages. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 25, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janneh, O.; Hartkoorn, R.C.; Jones, E.; Owen, A.; Ward, S.A.; Davey, R.; Back, D.J.; Khoo, S.H. Cultured CD4T cells and primary human lymphocytes express hOATPs: Intracellular accumulation of saquinavir and lopinavir. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 155, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).