Abstract

Background/Objectives: There is no consensus regarding the impacts of supplementation with milk proteins (MPs) on body composition (BC). This systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessed the effects of MP, casein protein (CP), and whey protein (WP) supplementation on BC and anthropometric parameters. Methods: A comprehensive search was performed in several databases to identify eligible RCTs published until October 2025. Random-effects models were applied to estimate the pooled effects of MP supplementation on anthropometric parameters. Results: A total of 150 RCTs were included. MP supplementation substantially increased lean body mass (LBM) (weighted mean difference (WMD): 0.41 kg; 95% CI: 0.19, 0.62; p < 0.001) and fat-free mass (FFM) (WMD: 0.67 kg; 95% CI: 0.40, 0.94; p < 0.001). It also significantly reduced body fat percentage (BFP) (WMD: −0.66%; 95% CI: −1.03, −0.28; p = 0.001), fat mass (FM) (WMD: −0.66 kg; 95% CI: −0.91, −0.41; p < 0.001), and waist circumference (WC) (WMD: −0.69 cm; 95% CI: −1.16, −0.22; p = 0.004). No considerable effects were observed for muscle mass (MM), body mass index (BMI), and body weight (BW). Dose–response analysis revealed that MP dosage was associated with significant changes in BFP, LBM, and MM. Conclusions: MP supplementation was associated with favorable modifications in body composition, including increases in LBM and FFM, as well as reductions in FM, BFP, and WC. These findings provide coherent and consistent evidence supporting the potential role of MP supplementation in targeted body composition management.

1. Introduction

Supplementation with milk proteins (MPs) has been widely investigated for its potential effects on body composition (BC), particularly in individuals with specific nutritional needs or those engaged in high levels of physical activity [1,2]. Dairy-derived proteins enhance satiety, improve glycemic regulation, and support weight management [3,4]. Whey protein (WP) and milk protein concentrate (MPC) notably affect lean body mass (LBM) and body fat, positioning them as effective strategies for improving BC [1]. Incorporating milk products into the diet improves skeletal muscle mass (MM) and reduces body fat in young women with insufficient protein intake [5]. Among individuals participating in resistance training (RT), MPC supplementation has been associated with reductions in fat mass (FM) and body fat percentage (BFP), along with increases in LBM [6]. It has been indicated that MP supplementation, with or without RT, may improve MM and strength in older adults [7,8].

Cow’s milk provides essential macro- and micronutrients, along with high-quality proteins, making it an important component of a balanced diet [9,10]. Dairy proteins are primarily composed of whey and casein, which account for approximately 20% and 80% of the total amino acids (AAs), respectively [11]. These proteins differ markedly in their digestion and absorption kinetics [12]. WP is rapidly digested, in contrast to casein protein (CP), which is absorbed at a slower rate [13]. CP supplies all essential AAs except cysteine [14], whereas WP is particularly rich in branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) (isoleucine, valine, and leucine) at higher concentrations than CP [15,16]. Leucine serves as a key regulator that stimulates muscle protein synthesis [17]. Conversely, CP contains higher amounts of non-essential AAs than WP [15]. Both WP and CP have received increasing attention from researchers and consumers because of their potential health benefits [18,19,20,21,22]. WP, one of the most commonly used supplements among athletes [23], provides BCAAs that promote muscle protein synthesis [24] and is safe for improving BC and reducing cardiovascular risk factors [14,20,21,25].

Several reviews and meta-analyses have examined the impacts of MP and WP supplementation, with or without RT, on BC [1,2,26,27,28,29,30]. However, the existing evidence is fragmented. Prior reviews have largely focused on either WP or CP in isolation, emphasized resistance-trained or athletic populations, or have not evaluated dose–response relationships. Furthermore, the effects of MP supplementation across diverse consumer groups on a broader range of anthropometric outcomes remain insufficiently characterized. These limitations have led to inconsistent or contradictory findings, preventing the development of clear, evidence-based recommendations for the use of MP supplementation to improve BC. Therefore, this systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aimed to comprehensively assess the effects of MP supplementation on BC and anthropometric parameters in adults and provide robust and clinically relevant evidence.

2. Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were implemented following the recommendations outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [31] and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. In addition, the systematic review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (No. CRD42025634923).

2.1. Search Strategy

Two investigators searched some databases (Scopus, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Web of Science) for potential RCTs published until October 2025. A grey literature search was performed using Google Scholar and trial registries to detect additional studies. The reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and included trials were also screened to find any further RCTs. When full texts were not accessible, the corresponding authors were contacted to request the necessary information and full texts.

The search strategy was structured around the PICOS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, and Study design) [32] to guide the identification of eligible studies. Search strategies were customized for each database. Both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and non-MeSH keywords were used. Boolean operators (OR, AND) were applied to combine search terms and enhance the overall sensitivity of the search. Body composition and anthropometric parameters were MM, LBM, FM, BFP, fat-free mass (FFM), body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and body weight (BW).

The search strategy included the following terms: (“milk protein” OR “milk” OR “milk protein supplementation” OR “milk protein supplement” OR “casein” OR “whey” OR “whey supplementation” OR “whey supplement” OR “casein supplementation” OR “casein supplement” OR “MPC” OR “milk protein concentrate” OR “whey protein hydrolysates” OR “WPH”) AND (“body weight” OR “body mass index” OR “BMI” OR “WC” OR “waist circumference” OR “BFP” OR “body fat percentage” OR “FFM” OR “fat-free mass” OR “FM” OR “fat mass” OR “LBM” OR “lean body mass” OR “muscle mass” OR “MM”) AND (“randomized controlled trial” OR “RCT” OR “clinical trial”). The search strategy in PubMed is provided in Table S1.

2.2. Selection Criteria

All citations retrieved for this meta-analysis were transferred into EndNote for reference management. Study selection was performed independently by two researchers, and any differences in assessment were addressed in consultation with a third investigator. Eligible RCTs evaluated the effects of supplementation with MP on BC and anthropometric measurements in adults and compared the intervention with a placebo or standard control. Both crossover and parallel RCTs were included. Studies were required to have an intervention duration of at least 2 weeks, enroll participants aged ≥ 18 years, and report at least one outcome of interest (FFM, BMI, WC, MM, LBM, FM, BFP, or BW) at both baseline and post-intervention. Early anabolic and atrophic responses in muscle protein metabolism can occur within days, and previous meta-analyses have documented measurable lean-mass changes within 14 days [33]. Therefore, a ≥2-week minimum intervention duration was selected to ensure inclusion of trials capable of producing early physiological adaptations while excluding very short exposure periods unlikely to yield meaningful changes. Trials were excluded if MP was provided as part of a multicomponent supplement in the intervention or control group. Additional exclusion criteria were the absence of a control or placebo arm, enrollment of pregnant women or participants < 18 years, the use of observational or other non-randomized designs, failure to meet the ≥2-week minimum intervention duration, or a lack of adequate baseline or post-intervention data for at least one outcome of interest.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data extraction was conducted independently by two investigators, and any discrepancies were settled through consultation with another researcher. The extracted information included study characteristics such as trial design, duration, setting, sample size, first author name, publication year, and MP dose. Participant demographics, including BMI, sex, and age, were also collected. The outcomes of interest (WC, FFM, BMI, FM, BW, LBM, MM, and BFP) were recorded at baseline and at the post-intervention time point.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias in each included study was independently evaluated by two reviewers using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool. Any differences in their assessments were addressed through consultation with a third researcher. The RoB 2 framework evaluated study quality through structured signaling questions across five key areas: how well participants were randomized, whether any departures from assigned interventions may have influenced outcomes, the extent and impact of missing outcome data, the appropriateness and consistency of outcome measurement, and whether the reported findings align with pre-specified analyses. Based on these evaluations, each domain was rated as “low risk,” “some concerns,” or “high risk” of bias [34].

2.5. Certainty Assessment

The certainty of evidence for each outcome was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. This framework evaluated five key areas (indirectness, RoB, imprecision, inconsistency, and potential publication bias). GRADE classified the certainty of evidence as high, moderate, very low, or low [35]. Two reviewers conducted the assessments independently, and any differences were resolved through discussion.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software (version 17). Outcomes were summarized as mean values with their corresponding standard deviations (SD), and effect sizes were expressed as mean differences. To compare changes from baseline to post-intervention between the MP and placebo groups, weighted mean differences (WMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated [36]. Pooled WMDs were estimated using a random-effects model [36]. Between-trial heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test [36]. I2 values were classified as low (0–25%), moderate (26–50%), substantial (51–75%), or considerable (>75%) heterogeneity [37].

Subgroup analyses were implemented to detect possible factors contributing to heterogeneity, such as participant sex (both sexes, male, female), health status (unhealthy vs. healthy), protein type (MP, WP, CP), baseline BMI (overweight, obesity, and normal), age (>60 vs. ≤60 years), trial duration (>8 vs. ≤8 weeks), and MP dosage (>30 vs. ≤30 g/day). Sensitivity analyses were applied to evaluate the effect of each trial on overall results.

Publication bias was evaluated by inspecting funnel plot symmetry, as well as Begg’s [38] and Egger’s [39] tests. Statistical significance was p < 0.05. Dose–response relationships were examined using the fractional polynomial method [40]. It was applied to explore potential non-linear associations between MP dosage (g/day) or intervention duration (weeks) and changes in the outcomes. Meta-regression analyses were carried out to examine linear dose–response associations between MP dosage or trial duration and the corresponding changes in outcomes [41].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

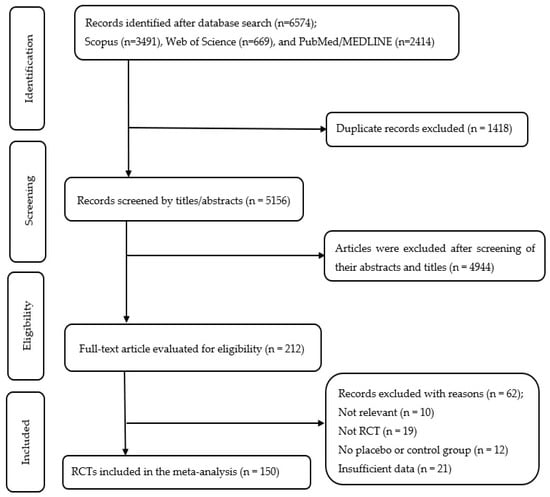

A comprehensive search among several databases retrieved 6574 records, and 1418 duplicate entries were subsequently excluded. Screening of abstracts and titles for the remaining 5156 records led to the exclusion of 4944. The full-text assessment of 212 articles resulted in the inclusion of 150 studies in the current meta-analysis. Figure 1 displays the flow diagram outlining the stages of screening and selecting studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

3.2. Study Characteristics

This systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis included 150 RCTs [12,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190]. Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Across 150 studies, 7998 participants were enrolled (MP group: n = 3979; control group: n = 4019), with sample sizes ranging from 10 to 208. The mean age of participants ranged from 18 to 86 years, with a mean BMI ranging from 18.5 to 46.5 kg/m2. In addition, 73 trials recruited mixed-sex samples [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,176,177,178,180,181,183,185,186,187,188,189,190], 28 were performed exclusively among female participants [12,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,174,179], and 49 included only men [128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,175,182,184].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included RCTs in the meta-analysis.

The trials were conducted across diverse participants, including dialysis patients [57,61,81,82,86]; older adults [52,66,68,71,75,77,83,84,85,87,89,90,93,94,95,96,98,99,103,108,110,111,114,119,121,124,159,164,184,185,186,187,188,189,190] with sarcopenic obesity [106,169]; individuals with overweight or obesity [42,43,48,49,50,53,54,55,56,59,67,70,78,80,105,107,112,115,116,117,128,129,130,137,174], abdominal obesity [76,91] hypertension (HTN) and pre-HTN [44,58,132], or increased visceral fat [45]; individuals who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [180]; patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [64,101,109,126,158,175], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [69,104], metabolic syndrome (MetS) [47], cystic fibrosis (CF) [51], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [60], cancer [63,88], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [65,72,100], sarcopenia [123,139], chronic liver disease [97], or hyperlipidemia [145]; pre-menopausal women [179]; postmenopausal women [118,154] who underwent bariatric surgery [125]; patients who underwent one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) [181]; patients with chronic heart disease (CHD) [102]; and women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [127]. Trials were also performed among healthy individuals [62,79,92,113,133,134,138,140,141,143,144,146,150,151,157,161,163,165,166,167,168,170,171,177], nursing home residents [73], midlife adults [46], sedentary individuals [183], basketball players [120,135], futsal players [136], trained men [74,131,147,148,153,155,156], male bodybuilders [142], physically active men [149,182], recreationally active men [172], well-trained endurance athletes [173], master triathletes [152], untrained individuals [176,178], collegiate female athletes [12], collegiate female dancers [122], and army soldiers [160,162].

The articles were published between 2000 and 2025. The RCTs were carried out in multiple countries, including Finland [73,138,150], the Netherlands [42,83,89,172,182,190], Australia [43,67,103,119,142], Japan [45,72,93,94,121,123,132], Iran [61,65,109,115,117,126,128,129,130,135,144,174,181], France [66,149], Tunisia [173], Brazil [60,97,99,101,102,106,110,111,116,118,124,125,175], Germany [47,169,177,178], Denmark [49,54,56,91,98], Canada [51,76,78,80,113,133,139,141,161,164,186], and the United States of America (USA) [12,44,46,48,50,52,53,55,57,59,62,69,70,74,75,77,79,85,92,95,104,105,107,112,114,120,122,127,131,134,140,143,145,147,148,151,154,155,156,157,160,162,165,170,176,183,188]. Trials were also conducted in China [58,90,96,100,108], Thailand [63], Italy [64,88], Portugal [136], Sweden [137,146], the Czech Republic [68], Norway [71,84], the United Kingdom (UK) [152,153,184,187,189], Israel [81,82], New Zealand [158,159,179], Malaysia [86], South Korea [168,171], Spain [87], Turkey [180], Iceland [185], Serbia [163], Chile [166], and Saudi Arabia [167]. Trial durations varied from 2 to 96 weeks, and the daily doses of CP, MP, and WP ranged between 3.14 and 137 g.

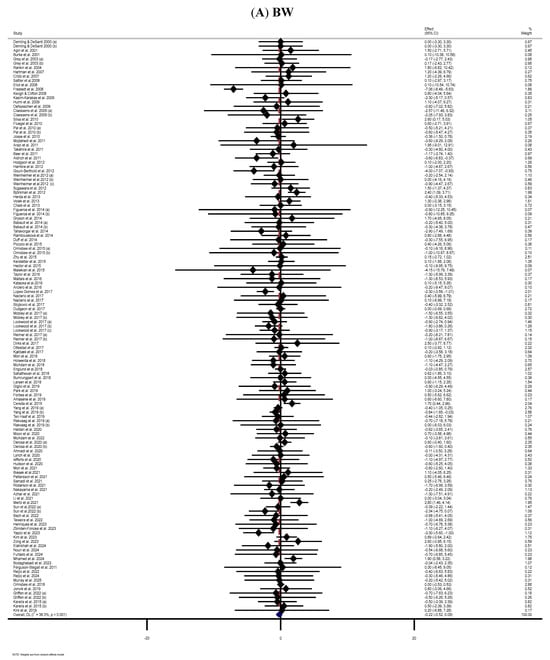

3.3. Effect of Supplementation with MP on BW

The meta-analysis of 114 RCTs [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,58,59,60,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,83,85,86,87,88,89,91,92,94,95,96,98,99,100,101,103,104,105,107,108,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,123,124,125,126,127,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,141,142,143,144,145,146,148,149,152,153,154,156,157,159,160,161,162,165,166,167,168,170,171,173,174,176,177,178,179,182,183,184,186,187] found no statistically significant impact of MP consumption on BW in the MP-treated group compared to the control group (WMD: −0.22 kg, 95% CI: −0.52, 0.09; p = 0.160). Moderate heterogeneity was observed among the included RCTs (I2 = 38.3%, p < 0.001) (Figure 2A). Subgroup analyses showed significant reductions in BW with MP supplementation among women, participants aged ≤60 years, and individuals with obesity. However, it significantly increased BW in participants older than 60 years (Table 2).

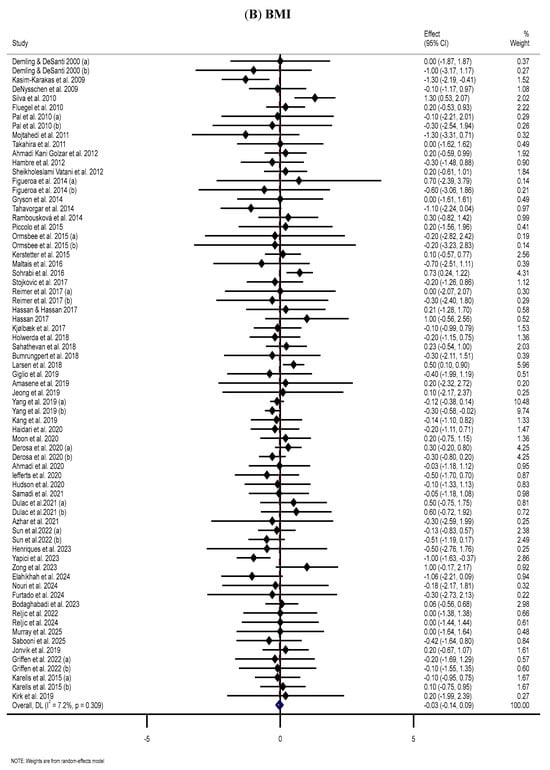

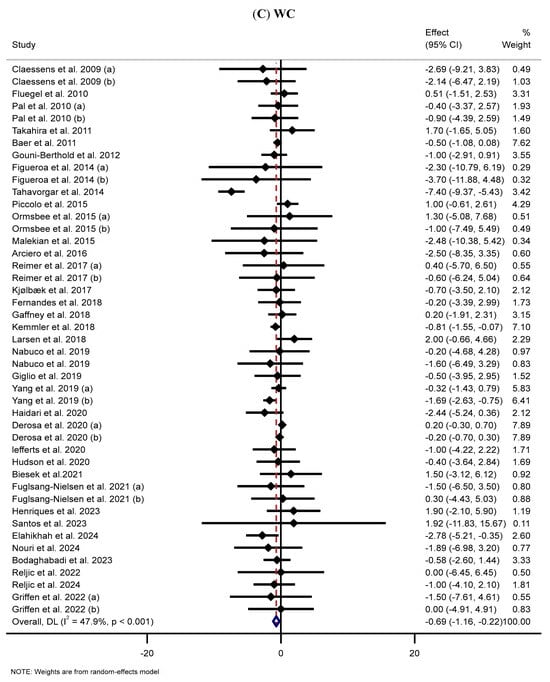

Figure 2.

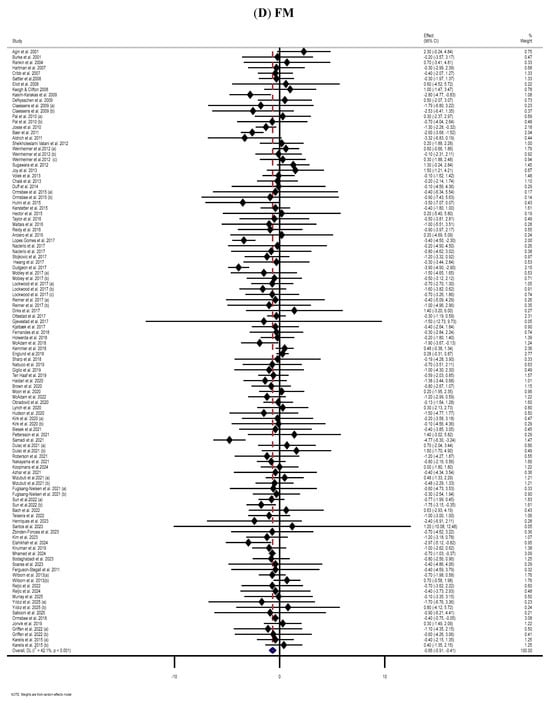

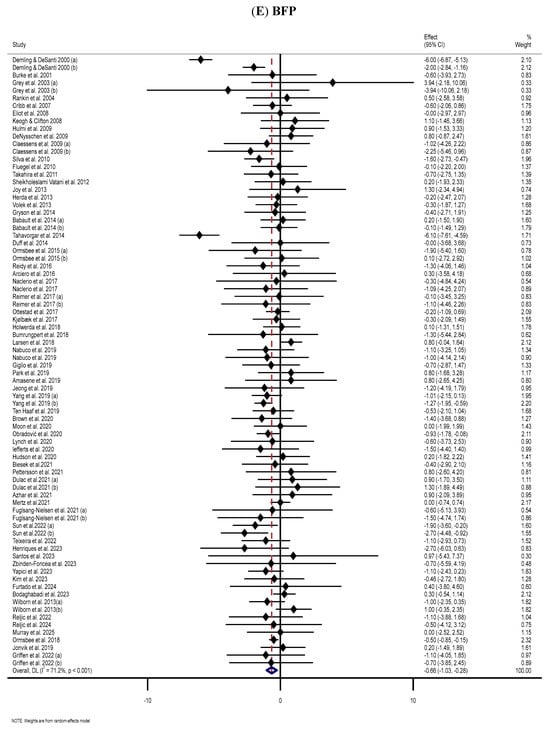

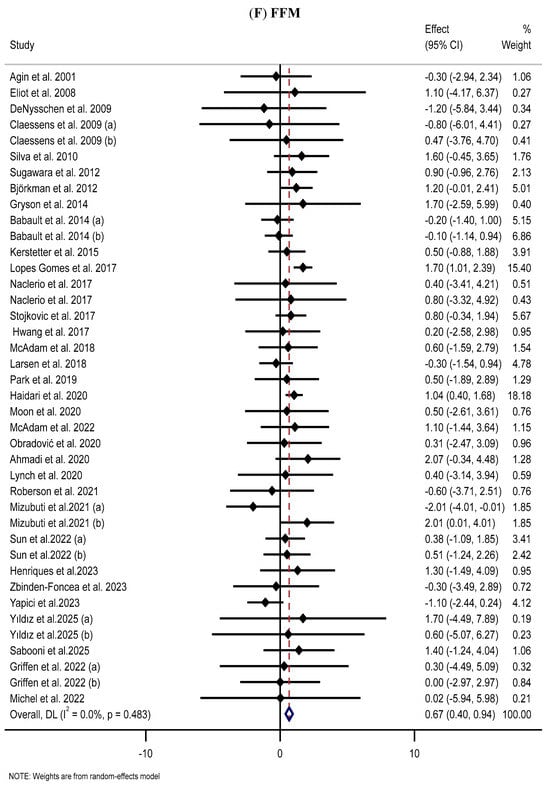

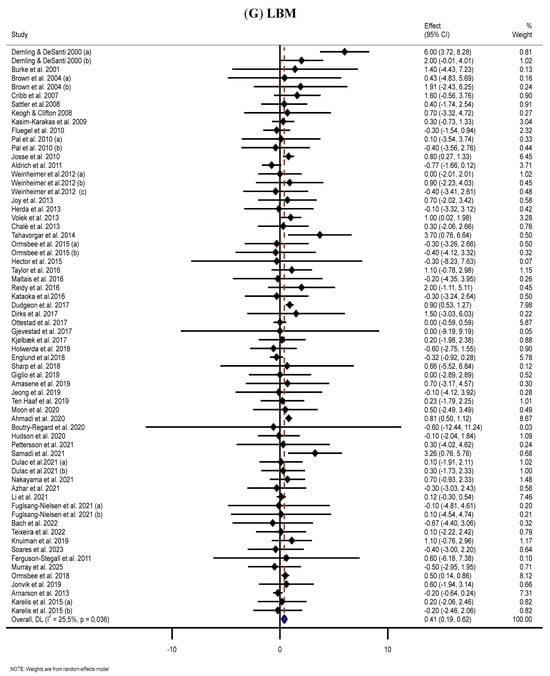

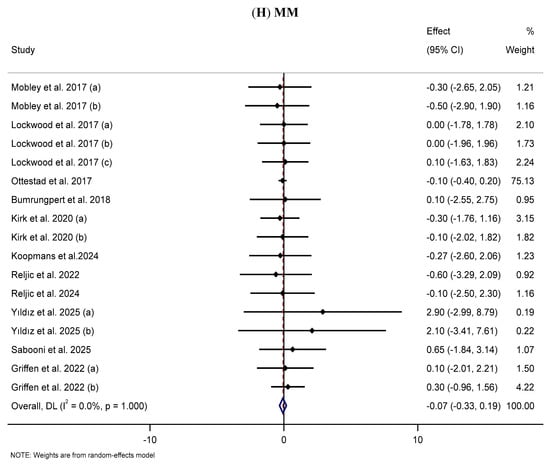

The forest plots illustrate the WMDs and 95% CIs regarding the impact of MP supplementation on (A) BW (Kg), (B) BMI (kg/m2), (C) WC (cm), (D) FM (kg), (E) BFP (%), (F) FFM (Kg), (G) LBM (kg), and (H) MM (kg) [12,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190].

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of the effects of MP supplementation on BC and anthropometric parameters.

3.4. Effect of Supplementation with MP on BMI

The meta-analysis of 59 trials [43,44,45,49,50,52,53,56,57,58,60,61,63,64,65,66,68,77,80,81,82,86,87,90,95,100,101,105,107,108,112,114,115,116,117,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,135,139,145,146,154,159,164,167,174,177,178,179,181,182,184,186,187] revealed no statistically substantial differences in BMI between the MP and placebo groups (WMD: −0.03 kg/m2, 95% CI: −0.14, 0.09; p = 0.626) (Figure 2B). Subgroup analyses indicated substantial reductions in BMI among female participants and those who consumed MP supplements (Table 2).

3.5. Effect of Supplementation with MP on WC

The meta-analysis of 36 studies [42,43,44,45,47,48,49,52,53,54,56,58,64,70,79,80,102,105,106,107,110,111,112,115,116,117,124,125,126,130,158,169,174,177,178,184] revealed that MP supplementation significantly reduced WC in the MP group compared to the placebo group (WMD: −0.69 cm, 95% CI: −1.16, −0.22; p = 0.004) (Figure 2C). Moderate heterogeneity was identified among the included studies (I2 = 47.9%, p < 0.001). Subgroup analyses displayed that long-term supplementation (>8 weeks) with high doses (>30 g/day) of WP markedly decreased WC in healthy participants and individuals with obesity (regardless of sex or age) (Table 2).

3.6. Effect of Supplementation with MP on FM

The meta-analysis, which included 93 trials [12,42,43,46,48,53,54,55,56,62,67,69,70,71,72,74,75,76,77,78,80,83,84,85,89,92,94,95,97,99,102,104,106,107,108,111,113,115,116,117,118,120,122,124,125,127,129,131,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,141,142,143,145,147,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,159,160,162,163,164,165,166,168,169,170,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,186,189,190] demonstrated that supplementation with MP substantially decreased FM in the MP group compared with the placebo group (WMD: −0.66 kg, 95% CI: −0.91, −0.41; p < 0.001) (Figure 2D). Moderate heterogeneity was detected among the trials (I2 = 42.1%, p < 0.001). Subgroup analyses further revealed that supplementation with MP or WP significantly decreased FM, particularly in healthy participants aged ≤ 60 years (irrespective of dose, duration, sex, or BMI) (Table 2).

3.7. Effect of Supplementation with MP on BFP

The meta-analysis of 68 RCTs [12,42,44,45,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,56,57,58,60,63,66,67,71,74,76,80,87,89,92,95,98,101,102,106,107,108,110,116,122,124,125,129,130,131,133,134,136,137,142,143,145,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,159,163,164,166,167,168,171,174,177,178,179,182,183,184] displayed substantial reductions in BFP following MP supplementation compared to the placebo group (WMD: −0.66%, 95% CI: −1.03, −0.28; p = 0.001) (Figure 2E). The analysis also revealed a very high level of heterogeneity among the included RCTs (I2 = 71.2%, p < 0.001). Subgroup analyses indicated that BFP significantly reduced during supplementation with WP or MP among participants aged ≤ 60 years and those with normal BMI (independent of dose, duration, sex, and health status) (Table 2).

3.8. Effect of Supplementation with MP on FFM

The effect of MP supplementation on FFM was assessed through the analysis of 34 RCTs [42,49,60,65,66,72,73,77,92,97,104,108,117,118,125,131,143,145,149,152,153,154,155,160,162,163,165,166,167,171,180,181,184,188]. The meta-analysis indicated that MP supplementation substantially increased FFM in the MP group compared with that in the placebo group (WMD: 0.67 kg, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.94; p < 0.001) (Figure 2F). Subgroup analyses further revealed that long-term supplementation with low WP doses significantly increased FFM among healthy participants and those with obesity (regardless of age or sex) (Table 2).

3.9. Effect of Supplementation with MP on LBM

The meta-analysis of 56 RCTs [43,44,46,50,53,54,55,56,57,62,65,67,69,71,74,75,78,83,84,85,87,89,93,94,95,96,99,107,113,116,120,127,130,131,132,133,135,136,137,139,140,142,147,148,151,156,159,164,172,175,176,179,182,183,185,186] revealed that MP supplementation significantly increased LBM in the MP group compared with the placebo group (WMD: 0.41 kg, 95% CI: 0.19, 0.62; p < 0.001) (Figure 2G). The analysis also revealed low heterogeneity among the included RCTs (I2 = 25.5%, p = 0.036). Subgroup analyses further indicated that LBM significantly increased after supplementation with WP or MP among participants with normal BMI (irrespective of dose, duration, sex, age, or health status) (Table 2).

3.10. Effect of Supplementation with MP on MM

The meta-analysis of 11 RCTs [63,71,157,170,177,178,180,181,184,189,190] did not demonstrate statistically significant impacts of MP supplementation on MM in the MP group compared with the placebo group (WMD: −0.07 kg, 95% CI: −0.33, 0.19; p = 0.588) (Figure 2H). Subgroup analyses also did not reveal any significant effects of supplementation with MP on MM (Table 2).

3.11. Publication Bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plots displayed asymmetry for all outcomes (Figure S1). However, Egger’s and Begg’s tests did not detect any evidence of publication bias for BMI, WC, FFM, BW, FM, LBM, BFP, and MM.

3.12. Risk of Bias Evaluation

The overall RoB of 150 included RCTs is summarized in Table S2. Among these studies, 99 RCTs were rated low RoB, while 51 were rated high RoB.

3.13. GRADE

Table S3 shows the certainty of evidence for the outcomes evaluated after MP supplementation. The evidence for BW, FM, FFM, BMI, WC, MM, and LBM was rated as high certainty, whereas the evidence for BFP was rated as moderate certainty.

3.14. Linear and Non-Linear Dose–Response Relations

Dose–response analyses revealed significant linear (−4.48, p = 0.011; Figure S4E) and non-linear (−0.04, p < 0.001; Figure S2E) associations between MP dose and changes in BFP. A significant linear relationship was also detected between MP dose and changes in LBM (5.66, p = 0.030; Figure S4G). In addition, a substantial non-linear association was identified between MP supplementation dose and change in MM (22.97, p = 0.003; Figure S2H).

3.15. Sensitivity Analysis

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis revealed no changes in any of the evaluated outcomes.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis included 150 RCTs. It revealed that MP supplementation may beneficially influence specific BC and anthropometric parameters, as evidenced by increases in LBM and FFM and reductions in FM, BFP, and WC. However, it had no substantial effects on BW, MM, and BMI.

Subgroup analyses revealed that MP substantially reduced BW in women, participants aged ≤60 years, and individuals with obesity. However, it significantly increased BW in participants aged 60 years or older. In addition, significant reductions in BMI were observed among female participants. Long-term supplementation (>8 weeks) with high WP doses (>30 g/day) markedly decreased WC in healthy participants and those with obesity (regardless of sex or age). Supplementation with MP or WP significantly reduced FM in healthy participants aged ≤ 60 years (independent of dose, duration, sex, and BMI). Furthermore, BFP significantly declined during supplementation with WP or MP among participants aged ≤ 60 years and those with normal BMI (irrespective of dose, duration, sex, or health status). Long-term supplementation with low WP doses significantly increased FFM among healthy participants and those with obesity (independent of age or sex). Moreover, LBM significantly increased after supplementation with WP or MP among participants with normal BMI (independent of dose, duration, sex, age, and health status).

Dose–response analyses demonstrated significant linear and non-linear associations between MP dosage and changes in BFP. A substantial linear relationship was also observed between MP dose and changes in LBM, whereas a significant non-linear association was found between MP dose and changes in MM.

A meta-analysis of 35 RCTs demonstrated that WP supplementation improved several BC indicators, including FM, BMI, LBM, and WC [27]. The beneficial effects of WP on BC appeared to be most pronounced when combined with RT and an overall calorie restriction [27]. Another meta-analysis of 10 trials reported that concurrent MP supplementation and RT yielded favorable effects on FFM in older adults, although no significant changes were observed in FM or BW [28]. Moreover, a meta-analysis of nine studies indicated that WP supplementation may increase BW and total FM in individuals with obesity or overweight [1]. These divergent findings likely reflect differences in participant characteristics, baseline adiposity, energy intake, and concurrent RT across trials. A meta-analysis of 17 RCTs suggested that MP is more effective than WP in improving RT-induced LBM or FFM gains in older adults [26]. A recent meta-analysis reported that WP supplementation did not significantly improve anthropometric indicators, including FM, BFP, LBM, or WC, in older adults [30]. It has been revealed that WP is more effective than CP in stimulating protein synthesis in older adults [191]. In addition, milk proteins, particularly WP, may play a critical role in mitigating sarcopenia, a condition characterized by a progressive decline in MM [192,193,194].

4.1. Possible Underlying Mechanisms

The impact of MP on BC appears to be mediated through multiple physiological pathways involving satiety regulation, energy metabolism, and hormonal responses [3,195]. WP and CP exert distinct metabolic effects that influence weight management and BC [195]. Dairy proteins have been shown to enhance satiety more effectively than carbohydrates or fats, thereby reducing overall energy intake [3]. WP is primarily associated with short-term satiety, whereas CP contributes to prolonged feelings of fullness [195]. Additionally, dairy proteins may modulate energy expenditure and lipid metabolism via calcium- and vitamin D-dependent mechanisms that regulate lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation [196]. MP also improves postprandial glycemic control by attenuating blood glucose responses when co-ingested with carbohydrates [3], an effect linked to enhanced insulin sensitivity and more favorable long-term regulation of BW and BC [197,198].

The rapid digestion and absorption of WP lead to elevated circulating AAs [199]. This stimulates muscle protein synthesis and modestly inhibits muscle protein degradation after RT [200]. Therefore, the influence of WP on BC is closely associated with metabolic regulation and MM preservation [1]. WP also stimulates the release of appetite-regulating hormones, including dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4), cholecystokinin (CCK), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) [201], contributing to appetite regulation [195]. Owing to its high biological value and rich BCAA profile, WP effectively supports muscle protein synthesis, which is a key determinant of BC maintenance during weight loss [125]. Furthermore, WP may promote the browning of white adipose tissue (WAT) and activate brown adipose tissue (BAT), thereby increasing energy expenditure and facilitating fat loss [202]. It has been suggested that uncoupling proteins and reduced lipogenesis may act as mechanisms contributing to improved weight management [202]. WP also enhances fat oxidation while preserving LBM, providing additional benefits for BC optimization [4,203].

In contrast, CP undergoes slower digestion, leading to the gradual release of AAs and prolonged satiety [195]. This sustained absorption may help maintain energy levels and reduce hunger, thereby supporting effective weight management [195]. CP intake has also been associated with the modulation of gastrointestinal hormones involved in appetite regulation, although evidence regarding its superiority over other protein sources is inconclusive [195]. Moreover, CP may influence metabolic hormones, potentially improving glucose metabolism and attenuating fat accumulation [204]. Overall, WP, CP, and MP exhibited distinct but complementary effects on BC, and their outcomes may vary according to individual metabolic profiles, physiological status, and dietary context.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review is the first dose–response meta-analysis that thoroughly assessed the effect of MP supplementation on BC. It included a large number of RCTs (n = 150) with sufficient sample sizes to identify statistically significant relationships between variables. The systematic literature search was unrestricted by publication date or language, reducing potential selection bias. Including recent studies from various regions improves the external validity and applicability of the results. The included RCTs enrolled adults with diverse health conditions, which enhances the generalizability of the findings and captures a wide range of potential responses across different populations. Additionally, the majority of studies demonstrated low RoB, and the GRADE assessment was high for all variables except BFP, which was rated as moderate.

However, this study had several limitations. Considerable heterogeneity was observed across the trials in terms of characteristics of participants, intervention duration, and supplement dosage. Further sources of heterogeneity included the use of different body composition assessment methods (e.g., dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), or skinfolds). Only short- to moderate-term trials were available, limiting the ability to assess long-term effects of WP, CP, or MP supplementation. Differences between the non-intervention and placebo groups also contributed to variability in outcomes. Additionally, variations in macronutrient composition, particularly total protein intake, between the intervention and control groups could have influenced BC outcomes independent of supplementation with MPs. Energy intake, a major determinant of BC, also differed among the studies and may have confounded their results. Moreover, most included trials focused on WP supplementation, whereas fewer studies investigated whole MP or CP supplementation. Therefore, additional RCTs are required to clarify the distinct and combined effects of CP and MP on BC and related anthropometric parameters. However, this meta-analysis provides a comprehensive and valuable insight for future studies.

5. Conclusions

This dose–response meta-analysis revealed that MP supplementation improved LBM, FFM, FM, BFP, and WC, supporting its potential as a feasible dietary approach to enhance BC. However, MP supplementation had no significant effect on BW, BMI, or MM. These findings should be interpreted cautiously due to heterogeneity across trials and the presence of several studies with high RoB. Well-designed, large-scale RCTs with longer follow-up periods are required to confirm these findings and determine the specific contributions of whole milk or CP supplementation to BC outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17243877/s1. Figure S1: funnel plots; Figure S2: non-linear dose–response association between MP dose and mean differences in anthropometric parameters; Figure S3: non-linear dose–response association between duration of MP supplementation and mean differences in anthropometric parameters; Figure S4: linear dose–response association between MP dose and mean differences in anthropometric parameters; Figure S5: linear dose–response association between duration of MP supplementation and mean differences in anthropometric parameters; Table S1: Search strategy in MEDLINE (PubMed); Table S2: RoB assessment for included RCTs; Table S3: GRADE assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.M., D.A.-L. and O.A.; Methodology: S.M., D.A.-L. and O.A.; Formal Analysis: S.M. and O.A.; Investigation: S.M., D.A.-L., O.A., N.A., A.F.A., S.S., A.B., M.M., D.G.C., S.C.F., J.A. and K.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: S.M.; Writing—Review and editing: S.M., D.G.C., S.C.F., J.A. and K.S.; Project Administration: S.M. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

S.C.F. is a scientific advisor for Bear Balanced®, has received creatine donations from Creapure® for research purposes, and is a sports nutrition advisor for the International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN). J.A. is the CEO and co-founder of the ISSN, an academic non-profit organization that has received sponsorship from companies involved in dietary supplement manufacturing and marketing. He also serves as a scientific advisor to several brands, including Forbes®, Bear Balanced®, Create®, Liquid Youth®, Algae to Omega™, and ENHANCED Games®. D.A.-L. is professionally involved in the health and nutrition industry, including work related to dietary products and supplements; however, no commercial interests influenced the design, analysis, or interpretation of this study. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MP | Milk protein |

| BC | Body composition |

| MPC | Milk protein concentrate |

| WMD | Weighted mean difference |

| LBM | Lean body mass |

| WP | Whey protein |

| FFM | Fat-free mass |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| RT | Resistance training |

| WC | Waist circumference |

| FM | Fat mass |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| PROSPERO | Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| BFP | Body fat percentage |

| CP | Casein protein |

| BW | Body weight |

| AAs | Amino acids |

| BCAAs | Branched-chain amino acids |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CHD | Chronic heart disease |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| MetS | Metabolic syndrome |

| MM | Muscle mass |

| OAGB | One anastomosis gastric bypass |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| PICOS | Population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, study design |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| WPH | Whey protein hydrolysates |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| CCK | Cholecystokinin |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| OW | Overweight |

| OB | Obesity |

| AO | Abdominal obesity |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| WPI | Whey protein isolate |

| WPC | Whey protein concentrate |

| PL | Placebo |

| WPC-L | High-lactoferrin-containing WPC |

| ERD | Energy-restricted diet |

| CHO | Carbohydrate |

| MD | Maltodextrin |

| PRE | Progressive resistance exercise |

| ITF | Inulin-type fructans |

| SG | Sleeve gastrectomy |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

References

- Wirunsawanya, K.; Upala, S.; Jaruvongvanich, V.; Sanguankeo, A. Whey protein supplementation improves body composition and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.E.; Alexander, D.D.; Perez, V. Effects of whey protein and resistance exercise on body composition: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2014, 33, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.; Luhovyy, B.; Akhavan, T.; Panahi, S. Milk proteins in the regulation of body weight, satiety, food intake and glycemia. Milk Milk Prod. Hum. Nutr. 2011, 67, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dougkas, A.; Reynolds, C.K.; Givens, I.D.; Elwood, P.C.; Minihane, A.M. Associations between dairy consumption and body weight: A review of the evidence and underlying mechanisms. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2011, 24, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Bains, K.; Jain, R. Effect of milk or milk derived food supplementation on body composition of Young Indian Women. Asian J. Dairy Food Res. 2023, 42, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.D.O.; Costa e Silva, G.; Souza, R.B.d.; Medeiros, J.S.; Brito, I.S.d.; Cardoso, S.P.; Leão, P.V.T.; Nicolau, E.S.; Cappato, L.P.; Favareto, R. Effect of milk protein concentrate supplementation on body composition and biochemical markers during a resistance training program. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e67222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuka, Y.; Fujita, S.; Kitano, N.; Kosaki, K.; Seol, J.; Sawano, Y.; Shi, H.; Fujii, Y.; Maeda, S.; Okura, T. Effects of aerobic and resistance training combined with fortified milk on muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-L.; Zhang, F.; Luo, H.-Y.; Quan, Z.-W.; Wang, Y.-F.; Huang, L.-T.; Wang, J.-H. Improving sarcopenia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of whey protein supplementation with or without resistance training. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangoni, F.; Pellegrino, L.; Verduci, E.; Ghiselli, A.; Bernabei, R.; Calvani, R.; Cetin, I.; Giampietro, M.; Perticone, F.; Piretta, L. Cow’s milk consumption and health: A health professional’s guide. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, I.; Bexiga, R.; Pinto, C.; Roseiro, L.; Quaresma, M. Cow’s Milk in Human Nutrition and the Emergence of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives. Foods 2022, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Radavelli-Bagatini, S.; Hagger, M.; Ellis, V. Comparative effects of whey and casein proteins on satiety in overweight and obese individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilborn, C.D.; Taylor, L.W.; Outlaw, J.; Williams, L.; Campbell, B.; Foster, C.A.; Smith-Ryan, A.; Urbina, S.; Hayward, S. The effects of pre-and post-exercise whey vs. casein protein consumption on body composition and performance measures in collegiate female athletes. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2013, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, D.; Lejaniya, A.S.; Mahesh, S.V.; Maneesh, S.V.; Sureshkumar, R.; Buttar, H.S.; Kumar, H.; Sharun, K.; Yatoo, M.I.; Mohapatra, R.K.; et al. Major Health Effects of Casein and Whey Proteins Present in Cow Milk: A Narrative Review. Indian Vet. J. 2021, 98, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, R.A.; Poppitt, S.D. Milk protein for improved metabolic health: A review of the evidence. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W.; Millward, D.; Long, S.; Morgan, L. Casein and whey exert different effects on plasma amino acid profiles, gastrointestinal hormone secretion and appetite. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, B.; Boirie, Y.; Senden, J.M.; Gijsen, A.P.; Kuipers, H.; van Loon, L.J. Whey protein stimulates postprandial muscle protein accretion more effectively than do casein and casein hydrolysate in older men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, M.C.; McGlory, C.; Bolster, D.R.; Kamil, A.; Rahn, M.; Harkness, L.; Baker, S.K.; Phillips, S.M. Leucine, not total protein, content of a supplement is the primary determinant of muscle protein anabolic responses in healthy older women. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Radavelli-Bagatini, S. The effects of whey protein on cardiometabolic risk factors. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pezeshki, A.; Zapata, R.C.; Yee, N.J.; Knight, C.G.; Tuor, U.I.; Chelikani, P.K. Diets enriched in whey or casein improve energy balance and prevent morbidity and renal damage in salt-loaded and high-fat-fed spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 37, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Asbaghi, O.; Dolatshahi, S.; Omran, H.S.; Amirani, N.; Koozehkanani, F.J.; Garmjani, H.B.; Goudarzi, K.; Ashtary-Larky, D. Effects of supplementation with milk protein on glycemic parameters: A GRADE-assessed systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Mehrbod, M.; Kouhi Sough, N.; Salehi Omran, H.; Dolatshahi, S.; Amirani, N.; Asbaghi, O. Impacts of supplementation with milk proteins on inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 1061–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Beyki, M.; Kouhi Sough, N.; Alaghemand, N.; Amirani, N.; Salehi Omran, H.; Dolatshahi, S.; Asbaghi, O. Impacts of Milk Protein Supplementation on Lipid Profile, Blood Pressure, Oxidative Stress, and Liver Enzymes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2025, nuaf068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, F.-C.; Khan, T.M.; Faidah, H.; Haseeb, A.; Khan, A.H. Effectiveness of whey protein supplements on the serum levels of amino acid, creatinine kinase and myoglobin of athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosukhowong, P.; Boonla, C.; Dissayabutra, T.; Kaewwilai, L.; Muensri, S.; Chotipanich, C.; Joutsa, J.; Rinne, J.; Bhidayasiri, R. Biochemical and clinical effects of Whey protein supplementation in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 367, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, G.T.; Lira, F.S.; Rosa, J.C.; de Oliveira, E.P.; Oyama, L.M.; Santos, R.V.; Pimentel, G.D. Dietary whey protein lessens several risk factors for metabolic diseases: A review. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-P.; Condello, G.; Kuo, C.-H. Effects of milk protein in resistance training-induced lean mass gains for older adults aged ≥60 y: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepandi, M.; Samadi, M.; Shirvani, H.; Alimohamadi, Y.; Taghdir, M.; Goudarzi, F.; Akbarzadeh, I. Effect of whey protein supplementation on weight and body composition indicators: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 50, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, K.; Chen, G.-C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, X.; Szeto, I.; Qin, L.-Q. Effects of milk proteins supplementation in older adults undergoing resistance training: A meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanach, N.I.; McCullough, F.; Avery, A. The impact of dairy protein intake on muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in middle-aged to older adults with or without existing sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalafi, M.; Fatolahi, S.; Jafari, R.; Rosenkranz, S.K.; Symonds, M.E.; Abbaszadeh Bidgoli, Z.; Fernandez, M.L.; Dinizadeh, F.; Batrakoulis, A. Effects of Whey Protein Supplementation on Body Composition, Muscular Strength, and Cardiometabolic Health in Older Adults: A Systematic Review with Pairwise Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagawa, R.; Watanabe, D.; Ito, K.; Otsuyama, T.; Nakayama, K.; Sanbongi, C.; Miyachi, M. Synergistic effect of increased total protein intake and strength training on muscle strength: A dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med.-Open 2022, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, C.B.; Berlin, J.A. Publication bias: A problem in interpreting medical data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1988, 151, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, P.; Altman, D.G. Regression using fractional polynomials of continuous covariates: Parsimonious parametric modelling. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 1994, 43, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.N. Interpreting and Visualizing Regression Models Using Stata; Stata Press College Station: College Station, TX, USA, 2012; Volume 558. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, M.; Van Baak, M.; Monsheimer, S.; Saris, W. The effect of a low-fat, high-protein or high-carbohydrate ad libitum diet on weight loss maintenance and metabolic risk factors. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.; Ellis, V.; Dhaliwal, S. Effects of whey protein isolate on body composition, lipids, insulin and glucose in overweight and obese individuals. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluegel, S.M.; Shultz, T.D.; Powers, J.R.; Clark, S.; Barbosa-Leiker, C.; Wright, B.R.; Freson, T.S.; Fluegel, H.A.; Minch, J.D.; Schwarzkopf, L.K. Whey beverages decrease blood pressure in prehypertensive and hypertensive young men and women. Int. Dairy J. 2010, 20, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahira, M.; Noda, K.; Fukushima, M.; Zhang, B.; Mitsutake, R.; Uehara, Y.; Ogawa, M.; Kakuma, T.; Saku, K. Randomized, double-blind, controlled, comparative trial of formula food containing soy protein vs. milk protein in visceral fat obesity. Circ. J. 2011, 75, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, N.D.; Reicks, M.M.; Sibley, S.D.; Redmon, J.B.; Thomas, W.; Raatz, S.K. Varying protein source and quantity do not significantly improve weight loss, fat loss, or satiety in reduced energy diets among midlife adults. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouni-Berthold, I.; Schulte, D.M.; Krone, W.; Lapointe, J.F.; Lemieux, P.; Predel, H.G.; Berthold, H.K. The whey fermentation product malleable protein matrix decreases TAG concentrations in patients with the metabolic syndrome: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1694–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciero, P.J.; Edmonds, R.C.; Bunsawat, K.; Gentile, C.L.; Ketcham, C.; Darin, C.; Renna, M.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, J.Z.; Ormsbee, M.J. Protein-Pacing from Food or Supplementation Improves Physical Performance in Overweight Men and Women: The PRISE 2 Study. Nutrients 2016, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.E.; Bibby, B.M.; Hansen, M. Effect of a Whey Protein Supplement on Preservation of Fat Free Mass in Overweight and Obese Individuals on an Energy Restricted Very Low Caloric Diet. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demling, R.H.; DeSanti, L. Effect of a hypocaloric diet, increased protein intake and resistance training on lean mass gains and fat mass loss in overweight police officers. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2000, 44, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grey, V.; Mohammed, S.R.; Smountas, A.A.; Bahlool, R.; Lands, L.C. Improved glutathione status in young adult patients with cystic fibrosis supplemented with whey protein. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2003, 2, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefferts, W.K.; Augustine, J.A.; Spartano, N.L.; Hughes, W.E.; Babcock, M.C.; Heenan, B.K.; Heffernan, K.S. Effects of Whey Protein Supplementation on Aortic Stiffness, Cerebral Blood Flow, and Cognitive Function in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Findings from the ANCHORS A-WHEY Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.L.; Zhou, J.; Kim, J.E.; Campbell, W.W. Incorporating Milk Protein Isolate into an Energy-Restricted Western-Style Eating Pattern Augments Improvements in Blood Pressure and Triglycerides, but Not Body Composition Changes in Adults Classified as Overweight or Obese: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuglsang-Nielsen, R.; Rakvaag, E.; Langdahl, B.; Knudsen, K.E.B.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J.J.; Hermansen, K.; Gregersen, S. Effects of whey protein and dietary fiber intake on insulin sensitivity, body composition, energy expenditure, blood pressure, and appetite in subjects with abdominal obesity. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinheimer, E.M.; Conley, T.B.; Kobza, V.M.; Sands, L.P.; Lim, E.; Janle, E.M.; Campbell, W.W. Whey Protein Supplementation Does Not Affect Exercise Training–Induced Changes in Body Composition and Indices of Metabolic Syndrome in Middle-Aged Overweight and Obese Adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjølbæk, L.; Sørensen, L.B.; Søndertoft, N.B.; Rasmussen, C.K.; Lorenzen, J.K.; Serena, A.; Astrup, A.; Larsen, L.H. Protein supplements after weight loss do not improve weight maintenance compared with recommended dietary protein intake despite beneficial effects on appetite sensation and energy expenditure: A randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Biruete, A.; Tomayko, E.J.; Wu, P.T.; Fitschen, P.; Chung, H.R.; Ali, M.; McAuley, E.; Fernhall, B.; Phillips, S.A. Results from the randomized controlled IHOPE trial suggest no effects of oral protein supplementation and exercise training on physical function in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, H.P.; Tong, X.; Li, Z.N.; Xu, J.Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, B.Y.; Qin, L.Q. Effect of whey protein on blood pressure in pre-and mildly hypertensive adults: A randomized controlled study. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frestedt, J.L.; Zenk, J.L.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Ward, L.S.; Bastian, E.D. A whey-protein supplement increases fat loss and spares lean muscle in obese subjects: A randomized human clinical study. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.B.d.C.; Mourão, L.F.; Silva, A.A.; Lima, N.M.F.V.; Almeida, S.R.; Franca, M.C., Jr.; Nucci, A.; Amaya-Farfán, J. Effect of nutritional supplementation with milk whey proteins in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2010, 68, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabi, Z.; Eftekhari, M.H.; Eskandari, M.H.; Rezaianzadeh, A.; Sagheb, M.M. Intradialytic oral protein supplementation and nutritional and inflammation outcomes in hemodialysis: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, M.H.; Lowery, R.P.; Shields, K.A.; Lane, J.R.; Gray, J.L.; Partl, J.M.; Hayes, D.W.; Wilson, G.J.; Hollmer, C.A.; Minivich, J.R. The effects of beef, chicken, or whey protein after workout on body composition and muscle performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2233–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumrungpert, A.; Pavadhgul, P.; Nunthanawanich, P.; Sirikanchanarod, A.; Adulbhan, A. Whey protein supplementation improves nutritional status, glutathione levels, and immune function in cancer patients: A randomized, double-blind controlled trial. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; D’angelo, A.; Maffioli, P. Change of some oxidative stress parameters after supplementation with whey protein isolate in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutrition 2020, 73, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, A.; Eftekhari, M.H.; Mazloom, Z.; Masoompour, M.; Fararooei, M.; Eskandari, M.H.; Mehrabi, S.; Bedeltavana, A.; Famouri, M.; Zare, M. Fortified whey beverage for improving muscle mass in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryson, C.; Ratel, S.; Rance, M.; Penando, S.; Bonhomme, C.; Le Ruyet, P.; Duclos, M.; Boirie, Y.; Walrand, S. Four-month course of soluble milk proteins interacts with exercise to improve muscle strength and delay fatigue in elderly participants. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 958.e1–958.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P. The effect of meal replacements high in glycomacropeptide on weight loss and markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1602–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambousková, J.; Procházka, B.; Binder, M.; Anděl, M. Effect of the liquid milk nutritional supplement with enhanced content of whey protein on the nutritional status of the elderly. Vnitr. Lek. 2014, 60, 556–561. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, F.R.; Rajicic, N.; Mulligan, K.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Koletar, S.L.; Zolopa, A.; Smith, B.A.; Zackin, R.; Bistrian, B. Evaluation of high-protein supplementation in weight-stable HIV-positive subjects with a history of weight loss: A randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, D.J.; Stote, K.S.; Paul, D.R.; Harris, G.K.; Rumpler, W.V.; Clevidence, B.A. Whey protein but not soy protein supplementation alters body weight and composition in free-living overweight and obese adults. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottestad, I.; Løvstad, A.; Gjevestad, G.O.; Hamarsland, H.; Benth, J.Š.; Andersen, L.F.; Bye, A.; Biong, A.S.; Retterstøl, K.; Iversen, P.O. Intake of a protein-enriched milk and effects on muscle mass and strength. A 12-week randomized placebo controlled trial among community-dwelling older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, K.; Takahashi, H.; Kashiwagura, T.; Yamada, K.; Yanagida, S.; Homma, M.; Dairiki, K.; Sasaki, H.; Kawagoshi, A.; Satake, M. Effect of anti-inflammatory supplementation with whey peptide and exercise therapy in patients with COPD. Respir. Med. 2012, 106, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, M.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Tilvis, R. Whey protein supplementation in nursing home residents. A randomized controlled trial. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2012, 3, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volek, J.S.; Volk, B.M.; Gómez, A.L.; Kunces, L.J.; Kupchak, B.R.; Freidenreich, D.J.; Aristizabal, J.C.; Saenz, C.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; Ballard, K.D. Whey protein supplementation during resistance training augments lean body mass. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2013, 32, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalé, A.; Cloutier, G.J.; Hau, C.; Phillips, E.M.; Dallal, G.E.; Fielding, R.A. Efficacy of whey protein supplementation on resistance exercise–induced changes in lean mass, muscle strength, and physical function in mobility-limited older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, W.R.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Rooke, J.J.; Kaviani, M.; Krentz, J.R.; Haines, D.M. The effect of bovine colostrum supplementation in older adults during resistance training. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstetter, J.E.; Bihuniak, J.D.; Brindisi, J.; Sullivan, R.R.; Mangano, K.M.; Larocque, S.; Kotler, B.M.; Simpson, C.A.; Cusano, A.M.; Gaffney-Stomberg, E. The effect of a whey protein supplement on bone mass in older Caucasian adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hector, A.J.; Marcotte, G.R.; Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Murphy, C.H.; Breen, L.; von Allmen, M.; Baker, S.K.; Phillips, S.M. Whey protein supplementation preserves postprandial myofibrillar protein synthesis during short-term energy restriction in overweight and obese adults. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malekian, F.; Gebrelul, S.S.; Henson, J.F.; Cyrus, K.D.; Goita, M.; Kennedy, B.M. The efects of whey protein and resistant starch on body weight. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2015, 5, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, R.A.; Willis, H.J.; Tunnicliffe, J.M.; Park, H.; Madsen, K.L.; Soto-Vaca, A. Inulin-type fructans and whey protein both modulate appetite but only fructans alter gut microbiota in adults with overweight/obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Hassan, F. Does whey protein supplementation affect blood pressure in hypoalbuminemic peritoneal dialysis patients? Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2017, 13, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K. Does whey protein supplementation improve the nutritional status in hypoalbuminemic peritoneal dialysis patients? Ther. Apher. Dial. 2017, 21, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, M.L.; Tieland, M.; Verdijk, L.B.; Losen, M.; Nilwik, R.; Mensink, M.; de Groot, L.C.; van Loon, L.J. Protein supplementation augments muscle fiber hypertrophy but does not modulate satellite cell content during prolonged resistance-type exercise training in frail elderly. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjevestad, G.O.; Ottestad, I.; Biong, A.S.; Iversen, P.O.; Retterstøl, K.; Raastad, T.; Skålhegg, B.S.; Ulven, S.M.; Holven, K.B. Consumption of protein-enriched milk has minor effects on inflammation in older adults—A 12-week double-blind randomized controlled trial. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2017, 162, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, D.A.; Kirn, D.R.; Koochek, A.; Zhu, H.; Travison, T.G.; Reid, K.F.; von Berens, Å.; Melin, M.; Cederholm, T.; Gustafsson, T. Nutritional supplementation with physical activity improves muscle composition in mobility-limited older adults, the VIVE2 study: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahathevan, S.; Se, C.-H.; Ng, S.; Khor, B.-H.; Chinna, K.; Goh, B.L.; Gafor, H.A.; Bavanandan, S.; Ahmad, G.; Karupaiah, T. Clinical efficacy and feasibility of whey protein isolates supplementation in malnourished peritoneal dialysis patients: A multicenter, parallel, open-label randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2018, 25, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasene, M.; Besga, A.; Echeverria, I.; Urquiza, M.; Ruiz, J.R.; Rodriguez-Larrad, A.; Aldamiz, M.; Anaut, P.; Irazusta, J.; Labayen, I. Effects of Leucine-enriched whey protein supplementation on physical function in post-hospitalized older adults participating in 12-weeks of resistance training program: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cereda, E.; Turri, A.; Klersy, C.; Cappello, S.; Ferrari, A.; Filippi, A.R.; Brugnatelli, S.; Caraccia, M.; Chiellino, S.; Borioli, V. Whey protein isolate supplementation improves body composition, muscle strength, and treatment tolerance in malnourished advanced cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 6923–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Haaf, D.S.; Eijsvogels, T.M.; Bongers, C.C.; Horstman, A.M.; Timmers, S.; de Groot, L.C.; Hopman, M.T. Protein supplementation improves lean body mass in physically active older adults: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Pang, H.; Peng, L.-N. Effects of whey protein nutritional supplement on muscle function among community-dwelling frail older people: A multicenter study in China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 83, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakvaag, E.; Fuglsang-Nielsen, R.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Landberg, R.; Johannesson Hjelholt, A.; Søndergaard, E.; Hermansen, K.; Gregersen, S. Whey protein combined with low dietary fiber improves lipid profile in subjects with abdominal obesity: A randomized, controlled trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, H.M.; Buman, M.P.; Dickinson, J.M.; Ransdell, L.B.; Johnston, C.S.; Wharton, C.M. No significant differences in muscle growth and strength development when consuming soy and whey protein supplements matched for leucine following a 12 week resistance training program in men and women: A randomized trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutry-Regard, C.; Vinyes-Parés, G.; Breuillé, D.; Moritani, T. Supplementation with whey protein, omega-3 fatty acids and polyphenols combined with electrical muscle stimulation increases muscle strength in elderly adults with limited mobility: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, K.; Saito, Y.; Sanbongi, C.; Murata, K.; Urashima, T. Effects of low-dose milk protein supplementation following low-to-moderate intensity exercise training on muscle mass in healthy older adults: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, G.; Wei, J.Y.; Schutzler, S.E.; Coker, K.; Gibson, R.V.; Kirby, M.F.; Ferrando, A.A.; Wolfe, R.R. Daily consumption of a specially formulated essential amino acid-based dietary supplement improves physical performance in older adults with low physical functioning. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2021, 76, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Meng, H.; Wu, S.; Fang, A.; Liao, G.; Tan, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhu, H. Daily supplementation with whey, soy, or whey-soy blended protein for 6 months maintained lean muscle mass and physical performance in older adults with low lean mass. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1035–1048.e1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizubuti, Y.; Vieira, E.; Silva, T.; d’Alessandro, M.; Generoso, S.; Teixeira, A.; Lima, A.; Correia, M. Comparing the effects of whey and casein supplementation on nutritional status and immune parameters in patients with chronic liver disease: A randomised double-blind controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, K.H.; Reitelseder, S.; Bechshoeft, R.; Bulow, J.; Højfeldt, G.; Jensen, M.; Schacht, S.R.; Lind, M.V.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Mikkelsen, U.R. The effect of daily protein supplementation, with or without resistance training for 1 year, on muscle size, strength, and function in healthy older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Azevedo Bach, S.; Radaelli, R.; Schemes, M.B.; Neske, R.; Garbelotto, C.; Roschel, H.; Pinto, R.S.; Schneider, C.D. Can supplemental protein to low-protein containing meals superimpose on resistance-training muscle adaptations in older adults? A randomized clinical trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 162, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, M.; Shen, H.; Ren, L.; Han, T.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, J. Effects of whey protein complex combined with low-intensity exercise in elderly inpatients with COPD at a stable stage. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 32, 375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho Furtado, C.; Jamar, G.; Barbosa, A.C.B.; Dourado, V.Z.; do Nascimento, J.R.; de Oliveira, G.C.A.F.; Hi, E.M.B.; de Arruda Souza, T.; Parada, M.J.G.; de Souza, F.G. Whey Protein Supplementation in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Undergoing a Resistance Training Program: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2024, 33, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, E.M.; Moreira, A.S.; Huguenin, G.V.; Tibiriça, E.; De Lorenzo, A. Effects of Whey Protein Isolate on Body Composition, Muscle Mass, and Strength of Chronic Heart Failure Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, J.M.; Zhu, K.; Lewis, J.R.; Kerr, D.; Meng, X.; Solah, V.; Devine, A.; Binns, C.W.; Woodman, R.J.; Prince, R.L. Long-term effects of a protein-enriched diet on blood pressure in older women. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agin, D.; Gallagher, D.; Wang, J.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Pierson, R.N., Jr.; Kotler, D.P. Effects of whey protein and resistance exercise on body cell mass, muscle strength, and quality of life in women with HIV. Aids 2001, 15, 2431–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Wong, A.; Kinsey, A.; Kalfon, R.; Eddy, W.; Ormsbee, M.J. Effects of milk proteins and combined exercise training on aortic hemodynamics and arterial stiffness in young obese women with high blood pressure. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabuco, H.C.G.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Fernandes, R.R.; Sugihara Junior, P.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Cunha, P.M.; Antunes, M.; Nunes, J.P.; Venturini, D.; Barbosa, D.S.; et al. Effect of whey protein supplementation combined with resistance training on body composition, muscular strength, functional capacity, and plasma-metabolism biomarkers in older women with sarcopenic obesity: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 32, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormsbee, M.J.; Kinsey, A.W.; Eddy, W.R.; Madzima, T.A.; Arciero, P.J.; Figueroa, A.; Panton, L.B. The influence of nighttime feeding of carbohydrate or protein combined with exercise training on appetite and cardiometabolic risk in young obese women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ling, C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Tong, X.; Hidayat, K.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H. Effects of whey protein or its hydrolysate supplements combined with an energy-restricted diet on weight loss: A randomized controlled trial in older women. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.; Tarighat-Esfanjani, A.; Sadra, V.; Ghasempour, Z.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Tajfar, P.; Gargari, B.P. Effects of Whey Protein Concentrate on Glycemic Status, Lipid Profile, and Blood Pressure in Overweight/Obese Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Turk. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 26, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuco, H.C.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Fernandes, R.R.; Junior, P.S.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Venturini, D.; Barbosa, D.S.; Silva, A.M.; Sardinha, L.B.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of protein intake beyond habitual intakes associated with resistance training on metabolic syndrome-related parameters, isokinetic strength, and body composition in older women. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.R.; Nabuco, H.C.; Junior, P.S.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Fabro, P.M.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Barbosa, D.S.; Venturini, D.; Schoenfeld, B.J. Effect of protein intake beyond habitual intakes following resistance training on cardiometabolic risk disease parameters in pre-conditioned older women. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 110, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, B.D.; Comerford, K.B.; Karakas, S.E.; Knotts, T.A.; Fiehn, O.; Adams, S.H. Whey protein supplementation does not alter plasma branched-chained amino acid profiles but results in unique metabolomics patterns in obese women enrolled in an 8-week weight loss trial. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josse, A.R.; Tang, J.E.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Phillips, S.M. Body composition and strength changes in women with milk and resistance exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, M.C.; Thorpe, M.P.; Karampinos, D.C.; Johnson, C.L.; Layman, D.K.; Georgiadis, J.G.; Evans, E.M. The effects of a higher protein intake during energy restriction on changes in body composition and physical function in older women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2011, 66, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahikhah, M.; Haidari, F.; Khalesi, S.; Shahbazian, H.; Mohammadshahi, M.; Aghamohammadi, V. Milk protein concentrate supplementation improved appetite, metabolic parameters, adipocytokines, and body composition in dieting women with obesity: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giglio, B.M.; Schincaglia, R.M.; da Silva, A.S.; Fazani, I.C.; Monteiro, P.A.; Mota, J.F.; Cunha, J.P.; Pichard, C.; Pimentel, G.D. Whey protein supplementation compared to collagen increases blood Nesfatin concentrations and decreases android fat in overweight women: A randomized double-blind study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidari, F.; Aghamohammadi, V.; Mohammadshahi, M.; Ahmadi-Angali, K.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. Whey protein supplementation reducing fasting levels of anandamide and 2-AG without weight loss in pre-menopausal women with obesity on a weight-loss diet. Trials 2020, 21, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes Gomes, D.; Moehlecke, M.; Lopes da Silva, F.B.; Dutra, E.S.; D’Agord Schaan, B.; Baiocchi de Carvalho, K.M. Whey protein supplementation enhances body fat and weight loss in women long after bariatric surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Kerr, D.A.; Meng, X.; Devine, A.; Solah, V.; Binns, C.W.; Prince, R.L. Two-year whey protein supplementation did not enhance muscle mass and physical function in well-nourished healthy older postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2520–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.W.; Wilborn, C.; Roberts, M.D.; White, A.; Dugan, K. Eight weeks of pre-and postexercise whey protein supplementation increases lean body mass and improves performance in Division III collegiate female basketball players. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Tokuda, Y. Effect of whey protein supplementation after resistance exercise on the muscle mass and physical function of healthy older women: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.F.; Welsh, T.; Panton, L.B.; Moffatt, R.J.; Ormsbee, M.J. Higher-protein intake improves body composition index in female collegiate dancers. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Tokuda, Y. Effect of whey protein supplementation after resistance exercise on the treatment of sarcopenia and quality of life among older women with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Jpn. J. Phys. Fit. Sports Med. 2021, 70, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesek, S.; Vojciechowski, A.S.; Filho, J.M.; Menezes Ferreira, A.C.R.d.; Borba, V.Z.C.; Rabito, E.I.; Gomes, A.R.S. Effects of exergames and protein supplementation on body composition and musculoskeletal function of prefrail community-dwelling older women: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, H.K.F.; Kattah, F.M.; Piccolo, M.S.; Rosa, C.d.O.B.; de Araújo Ventura, L.H.; Cerqueira, F.R.; Vieira, C.M.A.F.; Leite, J.I.A. Effect of whey protein supplementation on body composition of patients undergoing bariatric surgery. J. Arch. Health 2023, 4, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.; Gargari, B.P.; Ghasempour, Z.; Sadra, V.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Babaei, A.; Tajfar, P.; Tarighat-Esfanjani, A. The effects of whey protein on anthropometric parameters, resting energy expenditure, oxidative stress, and appetite in overweight/obese women with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2024, 44, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim-Karakas, S.E.; Almario, R.U.; Cunningham, W. Effects of protein versus simple sugar intake on weight loss in polycystic ovary syndrome (according to the National Institutes of Health criteria). Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Kani Golzar, F.; Sheikholeslami Vatani, D.; Mojtahedi, H.; Marandi, S.M. The effects of whey protein isolate supplementation and resistance training on cardiovascular risk factors in overweight young men. J. Isfahan Med. Sch. 2012, 30, 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikholeslami Vatani, D.; Ahmadi Kani Golzar, F. Changes in antioxidant status and cardiovascular risk factors of overweight young men after six weeks supplementation of whey protein isolate and resistance training. Appetite 2012, 59, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahavorgar, A.; Vafa, M.R.; Shidfar, F.; Gohari, M.; Heydari, I. Beneficial Effects of Whey Protein Preloads on some Cardiovascular Diseases Risk Factors of Overweight and Obese Men are Stronger than Soy Protein Preloads—A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Nutr. Intermed. Metab. 2015, 2, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.M.; Ratliff, K.M.; Blumkaitis, J.C.; Harty, P.S.; Zabriskie, H.A.; Stecker, R.A.; Currier, B.S.; Jagim, A.R.; Jäger, R.; Purpura, M. Effects of daily 24-gram doses of rice or whey protein on resistance training adaptations in trained males. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2020, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, Y.; Kamijo, Y.-i.; Ogawa, Y.; Sumiyoshi, E.; Nakae, M.; Ikegawa, S.; Manabe, K.; Morikawa, M.; Nagata, M.; Takasugi, S. Effects of hypervolemia by protein and glucose supplementation during aerobic training on thermal and arterial pressure regulations in hypertensive older men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, D.G.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Davison, K.S.; Candow, D.C.; Farthing, J.; Smith-Palmer, T. The effect of whey protein supplementation with and without creatine monohydrate combined with resistance training on lean tissue mass and muscle strength. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2001, 11, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, J.W.; Goldman, L.P.; Puglisi, M.J.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M.; Earthman, C.P.; Gwazdauskas, F.C. Effect of post-exercise supplement consumption on adaptations to resistance training. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004, 23, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]