Segmenting Increasing- and High-Risk Alcohol Drinkers by Motives and Occasions: Implications for Targeted Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Acknowledgements

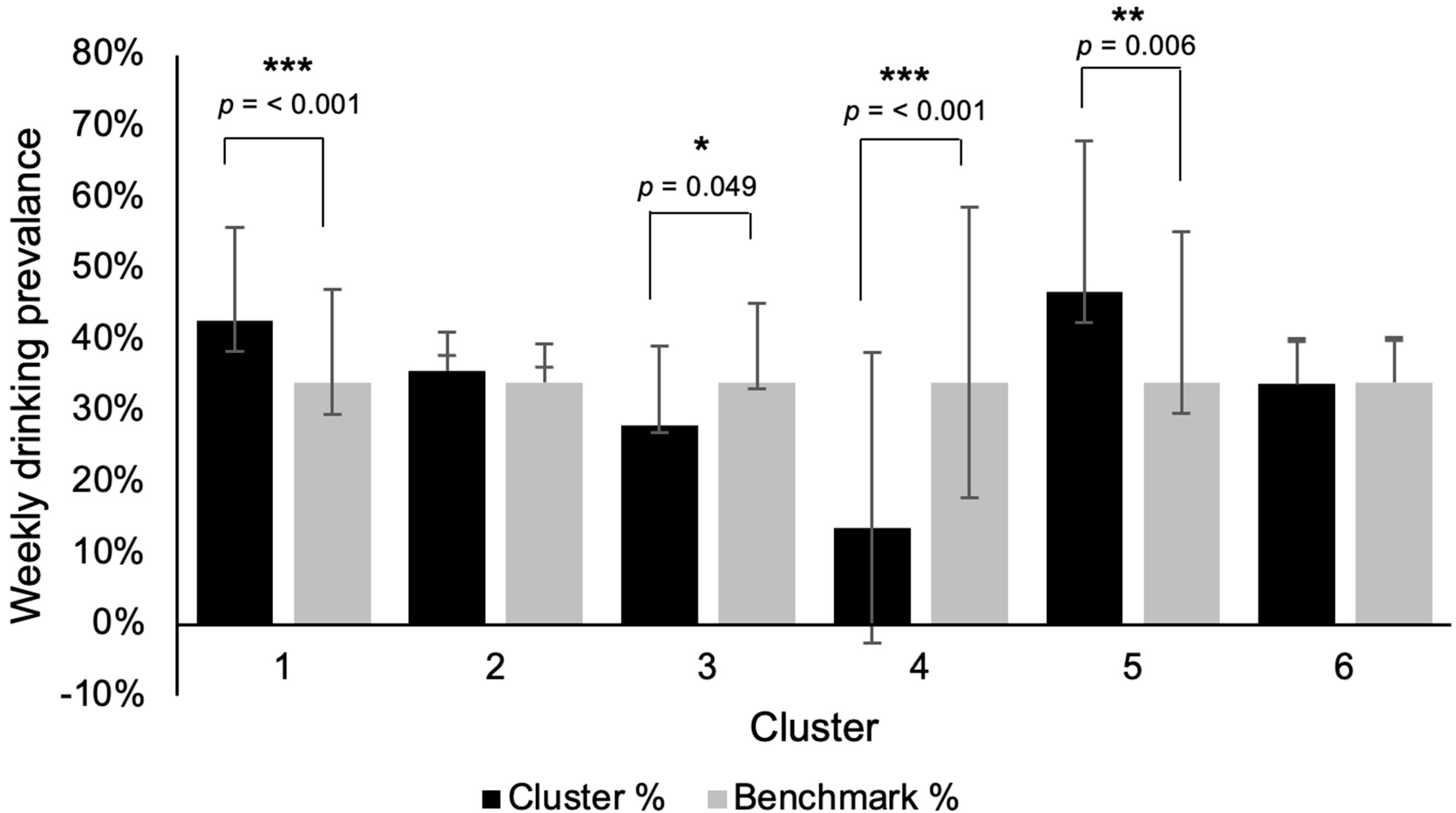

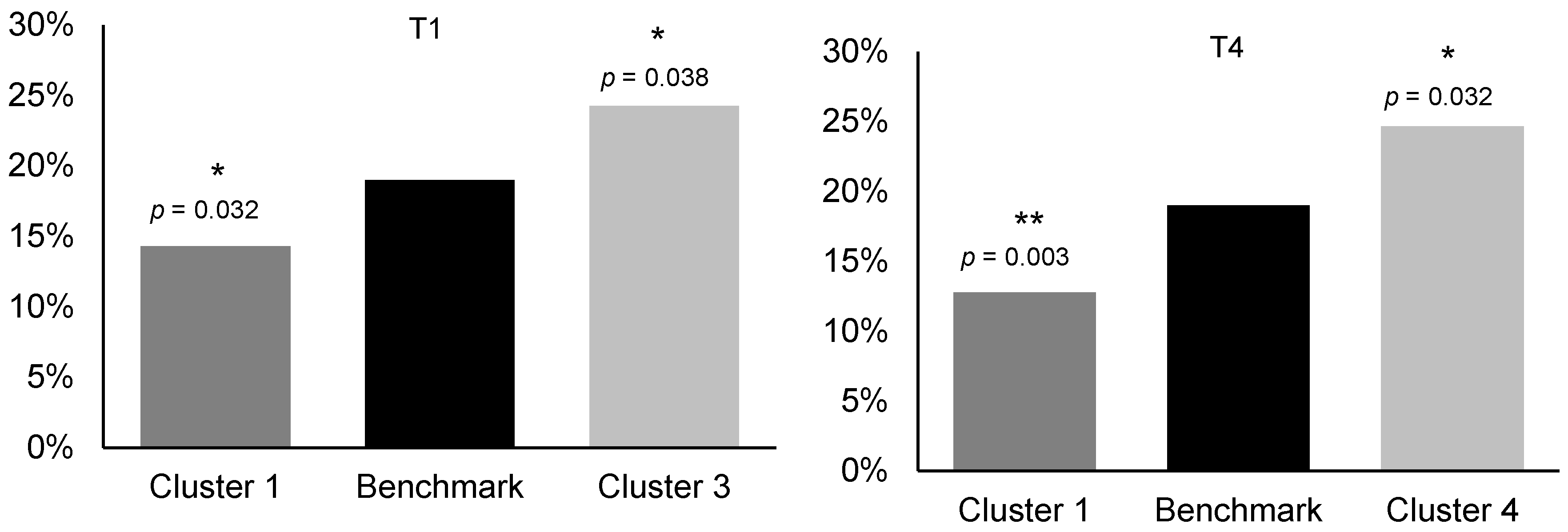

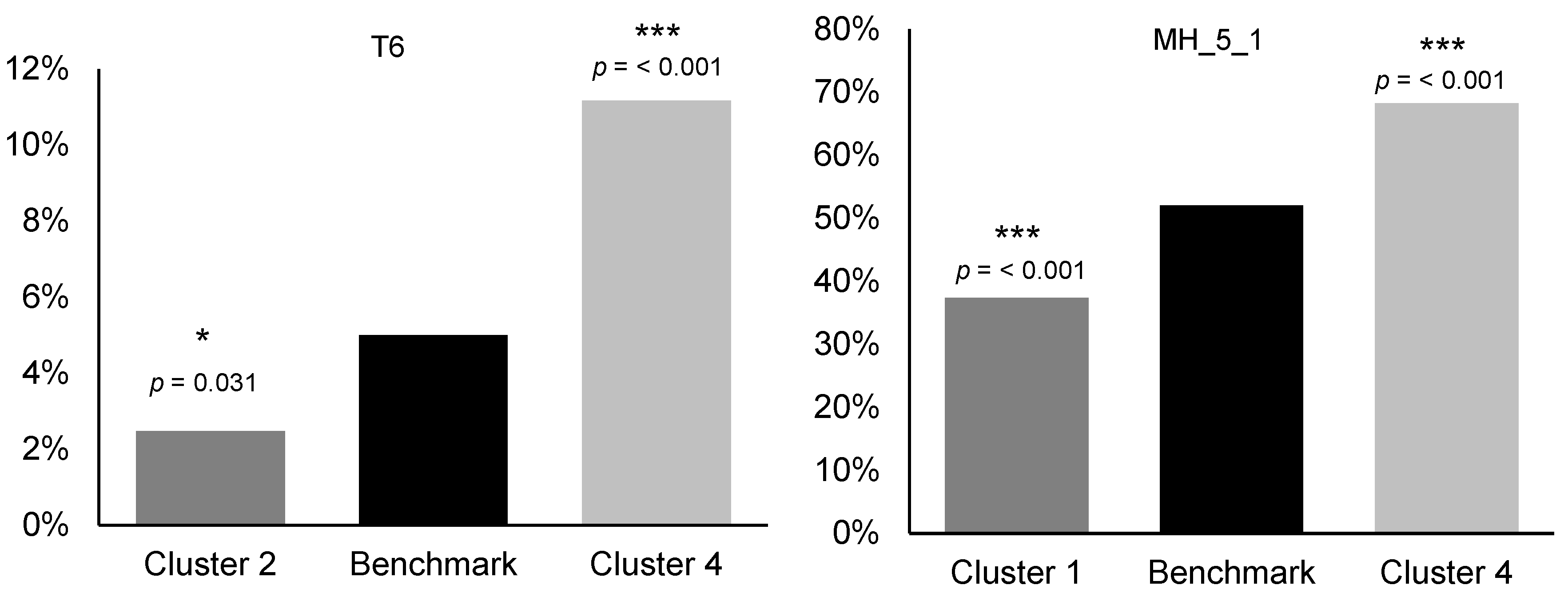

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation and Implications

4.2. International Approaches and Relevance

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2021. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-Specific Deaths in the UK. Office for National Statistics, 2025. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/bulletins/alcoholrelateddeathsintheunitedkingdom/registeredin2023 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Alcohol Profiles for England: Short Statistical Commentary, February 2024. gov.uk. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/alcohol-profiles-for-england-february-2024-update/alcohol-profiles-for-england-short-statistical-commentary-february-2024 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Drinkaware Monitor 2020: Drinking and the Coronavirus Pandemic. Drinkaware.co.uk. 2020. Available online: https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/research/drinkaware-monitors/drinkaware-monitor-2020-drinking-and-the-coronavirus-pandemic (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Alcohol Profile: Short Statistical Commentary, February 2025. gov.uk. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/alcohol-profile-february-2025-update/alcohol-profile-short-statistical-commentary-february-2025 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- World Health Organisation. Alcohol; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-Specific Deaths in the UK. www.ons.gov.uk. 2024. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/bulletins/alcoholrelateddeathsintheunitedkingdom/registeredin2022 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol’s Effects on the Body. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2025. Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohols-effects-body (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- World Health Organisation. No Level of Alcohol Consumption Is Safe for Our Health. World Health Organization, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- World Health Organisation. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- NE Digital. Adult Drinking. NHS England, 2024. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2022-part-1/adult-drinking (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Office for National Statistics, 2024. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Population Health Directorate. Alcohol and Drugs: Minimum Unit Pricing. www.gov.scot. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/alcohol-and-drugs/minimum-unit-pricing (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Public Health Scotland. Evaluating the Impact of Minimum Unit Pricing for Alcohol in Scotland: A Synthesis of the Evidence; Public Health Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, A.; Anderson, P.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Manthey, J.; Kaner, E.; Rehm, J. Immediate impact of minimum unit pricing on alcohol purchases in Scotland: Controlled interrupted time series analysis for 2015–18. BMJ 2019, 366, l5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh Government. Consultation on Setting the Minimum Price of Alcohol Beyond 2026; Welsh Government: Welsh, UK, 2025.

- Public Health England. The Public Health Burden of Alcohol: Evidence Review. gov.uk. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-public-health-burden-of-alcohol-evidence-review (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- O’Donnell, A.; Kaner, E. Are Brief Alcohol Interventions Adequately Embedded in UK Primary Care? A Qualitative Study Utilising Normalisation Process Theory. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, I.; Bye, E.K. The alcohol harm paradox: Is it valid for self-reported alcohol harms and does hazardous drinking pattern matter? BMC Public. Health 2024, 24, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Strategy of prevention: Lessons from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 1981, 282, 1847–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreitman, N. Alcohol Consumption and the Preventive Paradox. Addiction 1986, 81, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, C.; Mongan, D.; Millar, S.R.; Rackard, M.; Galvin, B.; Long, J.; Barry, J. Drinking patterns and the distribution of alcohol-related harms in Ireland: Evidence for the prevention paradox. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Alcohol-Use Disorders: Prevention. 2010. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Department of Health and Social Care. Alcohol Consumption: Advice on Low Risk Drinking. gov.uk. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/alcohol-consumption-advice-on-low-risk-drinking (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Alcohol: Applying All Our Health. gov.uk. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/alcohol-applying-all-our-health/alcohol-applying-all-our-health (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Kuntsche, E.; Kuntsche, S. Development and Validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised Short Form (DMQ–R SF). J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2009, 38, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aquino, S.; Callinan, S.; Smit, K.; Mojica-Perez, Y.; Kuntsche, E. Why do adults drink alcohol? Development and validation of a Drinking Motives Questionnaire for adults. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2022, 37, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drinkaware. Drinkaware Monitor 2023. www.drinkaware.co.uk. 2023. Available online: https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/research/drinkaware-monitors/drinkaware-monitor-2023/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- YouGov. Drinkaware Monitor 2023 Technical Report. 2023. Available online: https://media.drinkaware.co.uk/media/ttpn0iab/drinkaware-monitor-2023-technical-report.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Office for National Statistics. Adult Drinking Habits in Great Britain. ons.gov.uk. 2018. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/drugusealcoholandsmoking/bulletins/opinionsandlifestylesurveyadultdrinkinghabitsingreatbritain/2017 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Haynes, W. Benjamini–Hochberg Method; Encyclopedia of Systems Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. Global Code of Conduct & Ethics. yougov.com. 2022. Available online: https://corporate.yougov.com/documents/277/Global_Code_of_Conduct__Ethics_June_2022_Update_19.07.22.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Drinkaware. Governance, Funding and Support. www.drinkaware.co.uk. 2025. Available online: https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/about-us/governance-funding-and-support (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Critchlow, N.; Moodie, C.; Gallopel-Morvan, K. Restricting the content of alcohol advertising and including text health warnings: A between—Group online experiment with a non—Probability adult sample in the United Kingdom. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 48, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.; de Bruijn, A.; Angus, K.; Gordon, R.; Hastings, G. Impact of Alcohol Advertising and Media Exposure on Adolescent Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Alcohol. Alcohol. 2009, 44, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G. An evaluation of the impact of a national Minimum Unit Price on alcohol policy on alcohol behaviours. J. Public. Health 2025, 47, e94–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, J.M.; Farkouh, E.K.; Stockwell, T.; Thomas, G.; Johnston, K.; Naimi, T.S. The impact of alcohol minimum pricing policies on vulnerable populations and health equity: A rapid review. Int. J. Drug Policy 2025, 145, 105014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaner, E.F.S.; Beyer, F.R.; Garnett, C.; Crane, D.; Brown, J.; Muirhead, C.; Redmore, J.; O’Donnell, A.; Newham, J.J.; de Vocht, F.; et al. Personalised digital interventions for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community-dwelling populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD011479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, S.; Room, R.; Cook, M.; Mugavin, J.; Callinan, S. Affordances of home drinking in accounts from light and heavy drinkers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 296, 114712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HSC Public Health Agency. ‘Know Your Units’ Living Well campaign launched|HSC Public Health Agency. Available online: https://www.publichealth.hscni.net/news/know-your-units-living-well-campaign-launched (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Garland, E.L.; Howard, M.O. Mindfulness-based treatment of addiction: Current state of the field and envisioning the next wave of research. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2018, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzidowska, M.; Lee, K.S.K.; Wylie, C.; Bailie, J.; Percival, N.; Conigrave, J.H.; Hayman, N.; Conigrave, K.M. A systematic review of approaches to improve practice, detection and treatment of unhealthy alcohol use in primary health care: A role for continuous quality improvement. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, N.; García-Iglesias, J.; Bontoft, C.; Breslin, G.; Bartington, S.; Freethy, I.; Huerga-Malillos, M.; Jones, J.; Lloyd, N.; Marshall, T.; et al. A systematic review and behaviour change technique analysis of remotely delivered alcohol and/or substance misuse interventions for adults. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2022, 239, 109597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, P.S.; Warde, A.; Holmes, J. All drinking is not equal: How a social practice theory lens could enhance public health research on alcohol and other health behaviours. Addiction 2017, 113, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, N.C.; Debenham, J.; Slade, T.; Smout, A.; Grummitt, L.; Sunderland, M.; Barrett, E.L.; Champion, K.E.; Chapman, C.; Kelly, E.; et al. Effect of Selective Personality-Targeted Alcohol Use Prevention on 7-Year Alcohol-Related Outcomes Among High-risk Adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2242544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, N.C.; Conrod, P.J.; Slade, T.; Carragher, N.; Champion, K.E.; Barrett, E.L.; Kelly, E.V.; Nair, N.K.; Stapinski, L.; Teesson, M. The long-term effectiveness of a selective, personality-targeted prevention program in reducing alcohol use and related harms: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, C.C.A.; Mann, M.J.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Garcia, P.R.; Sigfusson, J.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Kristjansson, A.L. Preliminary impact of the adoption of the Icelandic Prevention Model in Tarragona City, 2015–2019: A repeated cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1117857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjansson, A.L.; Mann, M.J.; Sigfusson, J.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Development and Guiding Principles of the Icelandic Model for Preventing Adolescent Substance Use. Health Promot. Pract. 2019, 21, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnett, C.; Oldham, M.; Loebenberg, G.; Dinu, L.; Beard, E.; Angus, C.; Burton, R.; Field, M.; Greaves, F.; Hickman, M.; et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of the Drink Less smartphone app for reducing alcohol consumption compared with usual digital care: A comprehensive synopsis from a 6-month follow-up RCT. Public Health Res. 2025, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ally, A.K.; Lovatt, M.; Meier, P.S.; Brennan, A.; Holmes, J. Developing a social practice-based typology of British drinking culture in 2009-2011: Implications for alcohol policy analysis. Addiction 2016, 111, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, S.; Shelton, N. How is alcohol consumption affected if we account for under-reporting? A hypothetical scenario. Eur. J. Public. Health 2013, 23, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, S.; Kneale, J.; Shelton, N. Drinking pattern is more strongly associated with under-reporting of alcohol consumption than socio-demographic factors: Evidence from a mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Jones, L.; Morleo, M.; Nicholls, J.; McCoy, E.; Webster, J.; Sumnall, H. Holidays, celebrations, and commiserations: Measuring drinking during feasting and fasting to improve national and individual estimates of alcohol consumption. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neve, R.J.M.; Lemmens, P.H.; Drop, M.J. Changes in Alcohol Use and Drinking Problems in Relation to Role Transitions in Different Stages of the Life Course. Subst. Abus. 2000, 21, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, A.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Benzeval, M.; Kuh, D.; Bell, S. Life course trajectories of alcohol consumption in the United Kingdom using longitudinal data from nine cohort studies. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, B.A.; Krause, N.; Liang, J.; McGeever, K. Age differences in long-term patterns of change in alcohol consumption among aging adults. J. Aging Health 2011, 23, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Benchmark | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 2486) | (n = 622) | (n = 817) | (n = 344) | (n = 315) | (n = 140) | (n = 248) | ||

| Gender | Male | 61.36 | 58.2 | 65.54 | 62.49 | 52.19 | 65.82 | 63.09 |

| Female | 38.64 | 41.8 | 34.46 | 37.51 | 47.81 | 34.18 | 36.91 | |

| Age | 18–34 | 35.55 | 27.67 ** | 37.13 | 46.82 *** | 53.29 *** | 11.79 *** | 25.45 *** |

| 35–54 | 37.71 | 38.66 | 36.34 | 39.36 | 34.59 | 45.56 | 37.14 | |

| 55+ | 26.73 | 33.66 ** | 26.54 | 13.82 *** | 12.12 *** | 42.65 *** | 37.41 ** | |

| Ethnicity | Ethnic minority | 6.77 | 3.86 * | 7.25 | 11.41 * | 8.53 | 3.32 | 5.72 |

| White | 90.39 | 94.52 ** | 89.66 | 84.60 ** | 87.58 | 94.25 | 91.87 | |

| Parental status | Parent (U18) | 23.71 | 24.67 | 23.31 | 28.55 | 19.71 | 25.77 | 19.83 |

| Parent (O18) | 25.57 | 31.95 ** | 26.22 | 12.25 *** | 15.6 ** | 37.11 * | 32.09 | |

| Non-parent | 51.08 | 46.3 | 49.45 | 58.48 | 66.83 *** | 36.19 ** | 46.64 | |

| Social grade | ABC1 | 57.97 | 63.34 | 60.5 | 58.28 | 55.92 | 43.75 ** | 46.4 ** |

| C2DE | 42.03 | 36.66 | 39.5 | 41.72 | 44.08 | 56.25 ** | 53.6 ** | |

| IMD decile | 1 to 3 | 30.53 | 26.28 | 32.22 | 31.7 | 28.96 | 28.96 | 36.58 |

| 4 to 7 | 38.98 | 40.58 | 37.35 | 40.47 | 40.98 | 40.98 | 34.01 | |

| 8 to 10 | 30.49 | 33.14 | 30.43 | 27.83 | 30.06 | 30.06 | 29.41 | |

| Response | Benchmark | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Because drinking is part of the fun with family or friends | 56.4 | 76.68 *** | 39.31 *** | 89.91 *** | 67.47 *** | 10.74 *** | 27.15 *** |

| Because drinking adds a certain warmth to social occasions | 56.85 | 78.59 *** | 40.13 *** | 90.81 *** | 68.06 *** | 16.16 *** | 19.13 *** |

| To celebrate a special occasion with friends | 64.97 | 83.76 *** | 53.27 *** | 90.81 *** | 77.69 *** | 20.27 *** | 29.69 *** |

| To calm down when you are tense | 30.01 | 24.7 * | 24.81 ** | 59.32 *** | 30.51 | 48.59 *** | 8.76 *** |

| To help you unwind | 51.42 | 52.31 | 48.72 | 83.39 *** | 37.73 *** | 76.44 *** | 17.15 *** |

| To make you more outgoing | 33.51 | 9.66 *** | 23.87 *** | 86.06 *** | 80.63 *** | 9.98 *** | 5.91 *** |

| To overcome shyness | 30.61 | 4.79 *** | 19.94 *** | 86.03 *** | 79.02 *** | 8.94 *** | 4.58 *** |

| Because you feel more self-confident and sure of yourself | 35.46 | 9.2 *** | 24.48 *** | 92.02 *** | 87.09 *** | 16.3 *** | 4.54 *** |

| To put you at ease with people | 36.22 | 11.62 *** | 27.1 *** | 93.96 *** | 79.73 *** | 13.43 *** | 5.74 *** |

| Because it is satisfying to have a high-quality drink | 52.17 | 64.84 *** | 51.31 | 84.93 *** | 31.7 *** | 32.16 *** | 15.22 *** |

| Because it pairs well with food | 35.39 | 50.56 *** | 37.49 | 51.59 *** | 7.69 *** | 20.24 *** | 11.77 *** |

| Because there are certain products you particularly enjoy | 60.47 | 81.91 *** | 56.80 | 85.8 *** | 35.22 *** | 52.31 | 20.34 *** |

| Because you like the taste | 76.01 | 92.78 *** | 76.11 | 91.31 *** | 58.08 *** | 77.10 | 34.6 *** |

| Because it makes you happy | 60.28 | 79.36 *** | 43.44 *** | 92.1 *** | 67.06 * | 69.79 * | 9.86 *** |

| Because it gives you a pleasant feeling | 66.66 | 84.64 *** | 53.75 *** | 93.77 *** | 69.89 | 79.63 ** | 15.2 *** |

| Response | Benchmark | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking at home alone | 47.29 | 42.75 | 54.35 *** | 51.95 | 30.02 *** | 69.87 *** | 38.17 ** |

| A small number of drinks at home with people in my household | 56.53 | 70.14 *** | 59.33 | 67.88 *** | 37.17 *** | 28.87 *** | 37.62 *** |

| Several drinks at home with people in my household | 52.36 | 65.77 *** | 53.40 | 61.53 ** | 35.68 *** | 29.79 *** | 36.47 *** |

| Getting together at your or someone else’s house | 37.26 | 42.86 * | 37.84 | 47.03 *** | 34.92 | 11.58 *** | 25.27 *** |

| Going out for a meal | 46.25 | 57.59 *** | 51.2 * | 52.11 | 30.5 *** | 9.41 *** | 34.23 *** |

| Evening or night out with friends | 51.28 | 57.23 * | 52.21 | 59.58 ** | 51.77 | 17.01 *** | 40.54 ** |

| Going out for a couple of drinks in the afternoon | 30.79 | 27.82 | 34.71 | 43.38 *** | 25.83 | 5.86 *** | 28.28 |

| Drinking at events | 37.66 | 43.2 * | 40.25 | 49.28 *** | 33.16 | 7.22 *** | 22.02 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bennett, C.; Barratt, L.J.; O’Brien, A. Segmenting Increasing- and High-Risk Alcohol Drinkers by Motives and Occasions: Implications for Targeted Interventions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233745

Bennett C, Barratt LJ, O’Brien A. Segmenting Increasing- and High-Risk Alcohol Drinkers by Motives and Occasions: Implications for Targeted Interventions. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233745

Chicago/Turabian StyleBennett, Chloe, Liam J. Barratt, and Alastair O’Brien. 2025. "Segmenting Increasing- and High-Risk Alcohol Drinkers by Motives and Occasions: Implications for Targeted Interventions" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233745

APA StyleBennett, C., Barratt, L. J., & O’Brien, A. (2025). Segmenting Increasing- and High-Risk Alcohol Drinkers by Motives and Occasions: Implications for Targeted Interventions. Nutrients, 17(23), 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233745