Nutritional Determinants of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the European Union: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PECOS Strategy and Research Question

- Population: Adults (≥18 years) without diagnosed T2DM, may include prediabetes at baseline, residing in the EU-28.

- Exposure: Dietary and nutritional exposures, including dietary patterns, specific foods, macronutrient and micronutrient intake, or other nutrition-related behaviors.

- Control: Populations with lower or no exposure to the nutritional factor of interest.

- Outcome: Incidence of T2DM, as measured by clinical diagnosis, fasting glucose, HbA1c, or self-report confirmed by medical records.

- Study Design: Analytical peer-reviewed observational studies, including prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, and nested case–control studies.

- What is the association between adherence to specific dietary patterns and the incidence of T2DM among adults without diagnosed T2DM in the EU-28?

- What is the regional impact on dietary patterns adherence and its association with T2DM risk?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

- Whole & Minimally Processed Foods: nutrient-dense, low-processed foods commonly recommended for metabolic health.Includes: Dairy products, eggs, fruits, vegetables, cereals and cereal products, fish and seafood.

- Animal-Based & Protein-Rich Foods.Focus: High-protein foods with potentially divergent health effects depending on processing and source.Includes: Red meat and meat products, animal fats and oils.

- Processed & Discretionary Foods.Focus: Highly processed, energy-dense products typically associated with poor metabolic outcomes.Includes: Sugars and confectionery, bakery products, snacks and desserts, alcoholic beverages, and condiments.

- Composite & Special-Purpose Foods.Focus: Foods developed for specific populations or health contexts, including clinical trials or supplementation.Includes: Infant foods, food supplements, composite meals, and products for special nutritional use.

- Sugar-sweetened beverages.Focus: All drinkable products, categorized by potential metabolic effects.Includes: Non-alcoholic beverages (e.g., coffee, tea, soft drinks) and alcoholic beverages.

- Carbohydrates.Focus: Quantitative and qualitative aspects of carbohydrate intake.Includes: Glycemic index/load, fiber, sugars, and starches.

- Dietary Patterns.Focus: Holistic eating approaches such as the Mediterranean diet, Western diet, or other predefined food-based patterns.

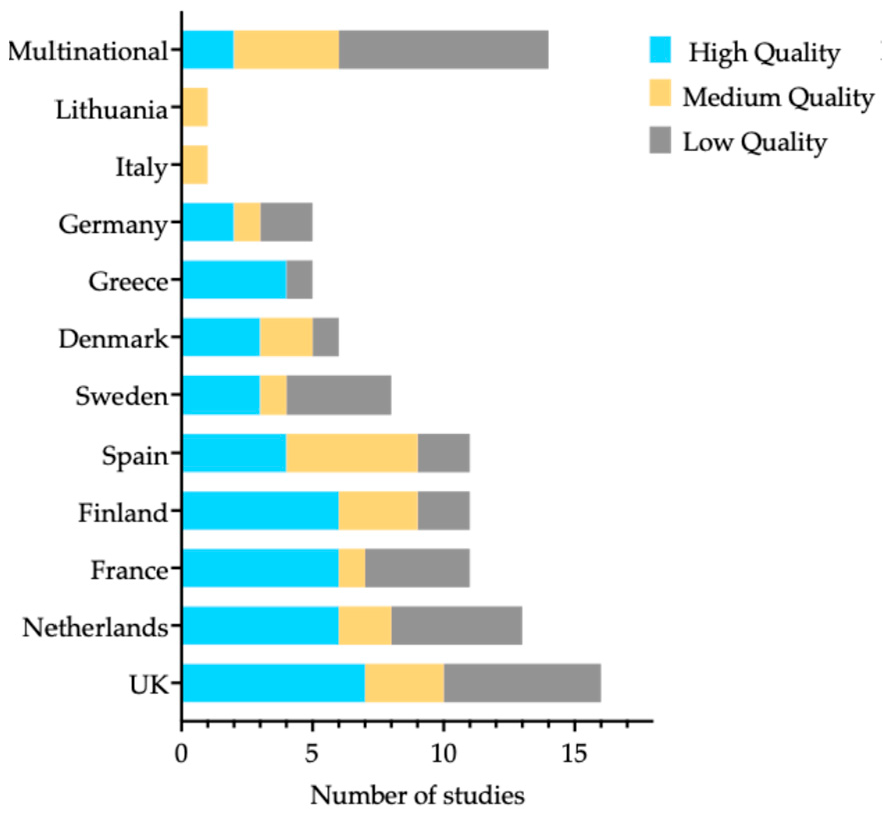

2.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

- Low Methodological Quality:Critical domain questions: One or more “no” answers, or one “no” answer combined with one “cannot determine/not reported”, or two or more “cannot determine/not reported” answers.Non-critical domain questions: Three or more “no” answers, or four or more “cannot determine/not reported”, or one “cannot determine/not reported” response combined with two “no” answers.

- Moderate Methodological Quality:Critical domain questions: One “no” answer and one “cannot determine/not reported” answer.Non-critical domain questions: Two “no” answers, or three “cannot determine/not reported”, or one “cannot determine/not reported” response combined with one “no” answer.

- High Methodological Quality:Critical domain questions: No “no” answers and no “cannot determine/not reported”.Non-critical domain questions: One “no” answer and at most two “cannot determine/not reported” responses.

3. Results

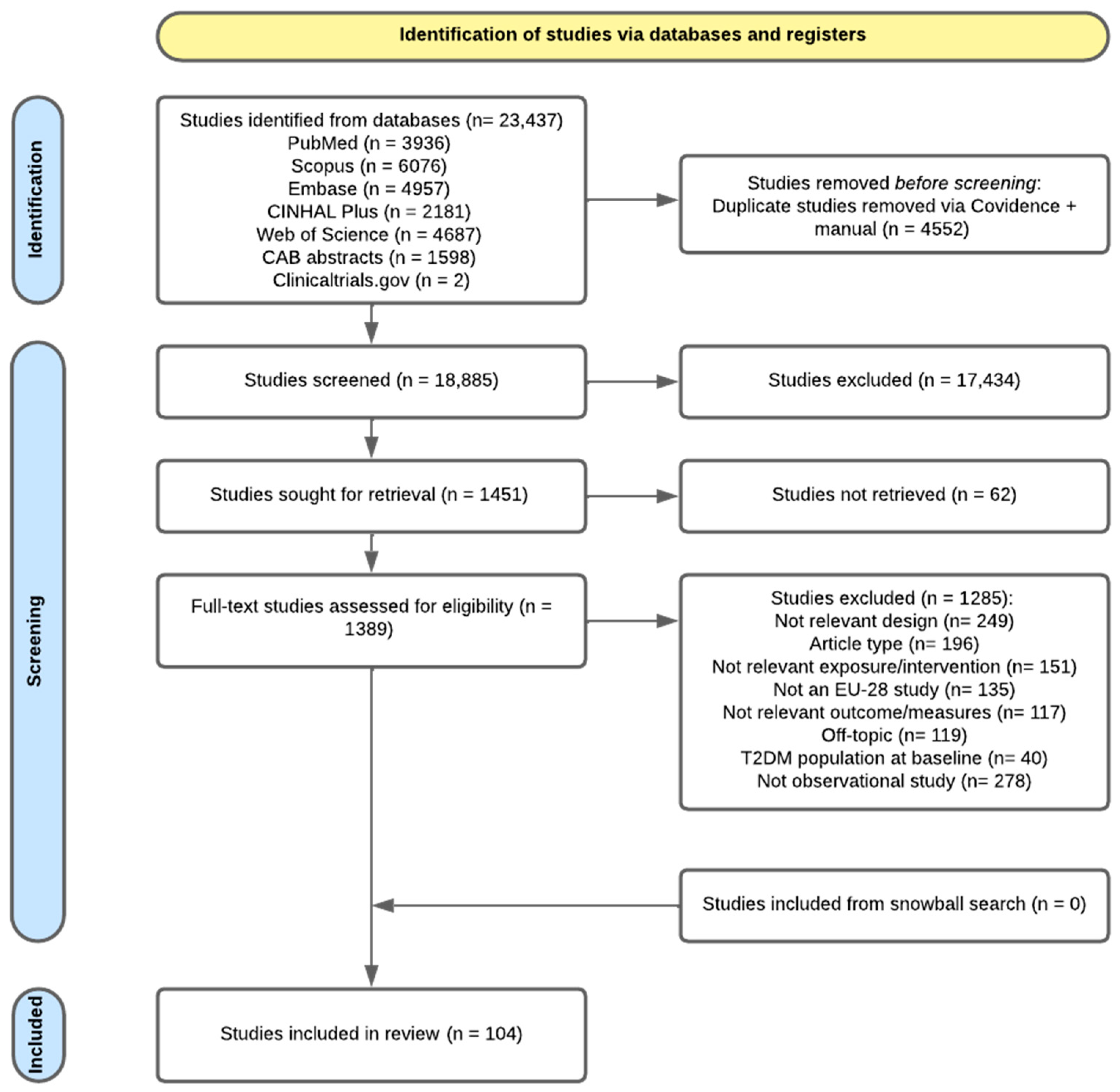

3.1. Study Selection

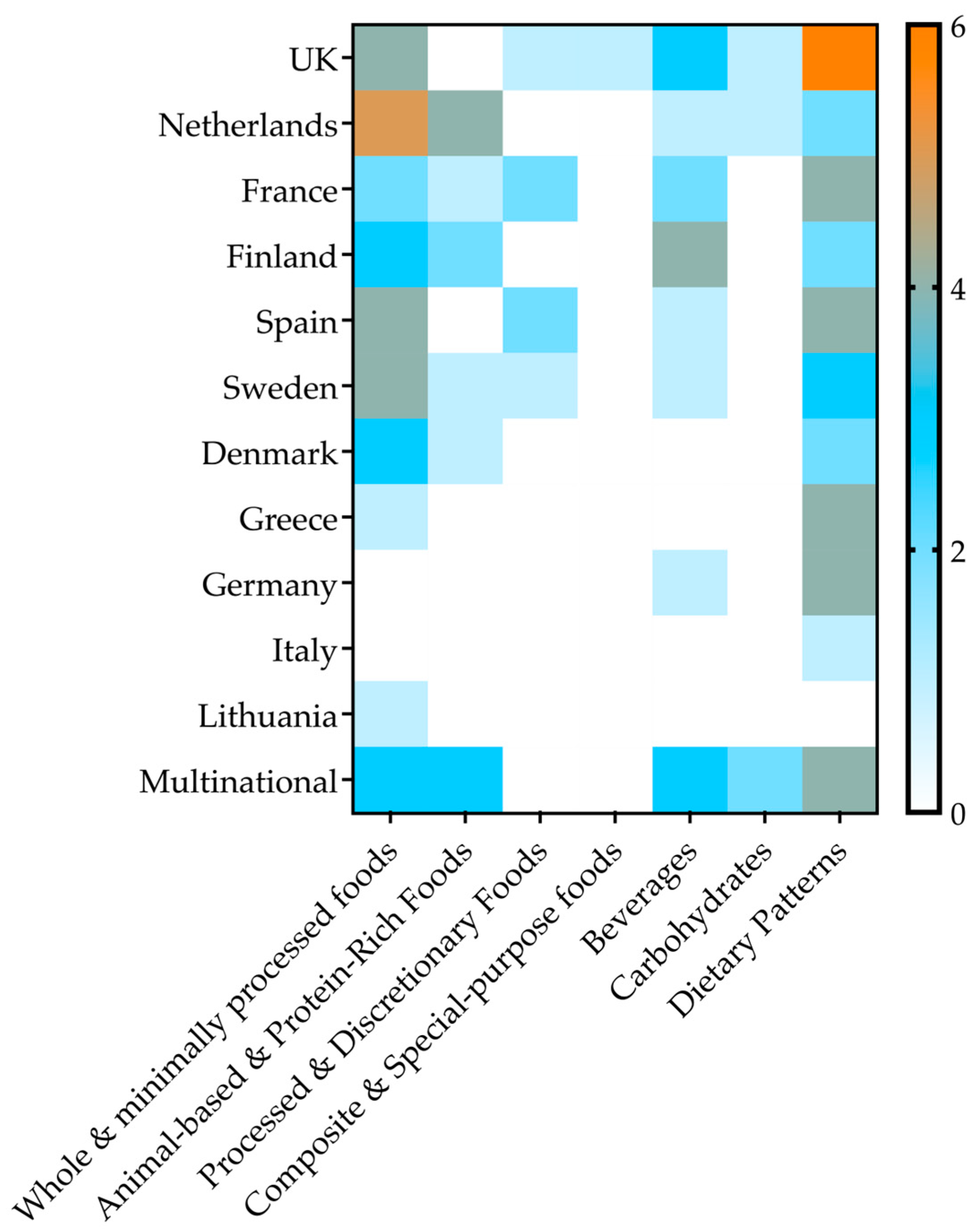

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Quality Assessment

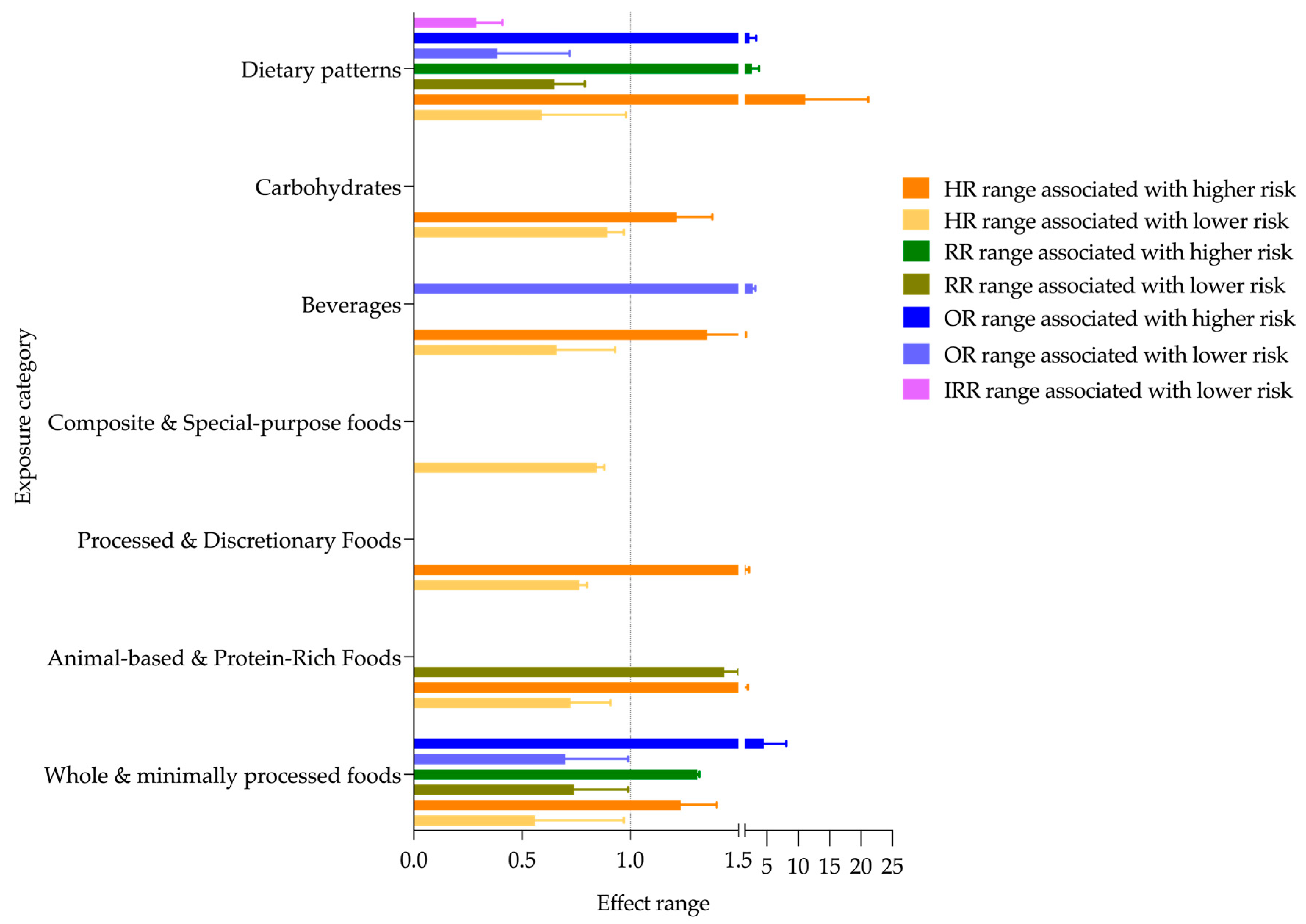

3.4. Main Findings

4. Discussion

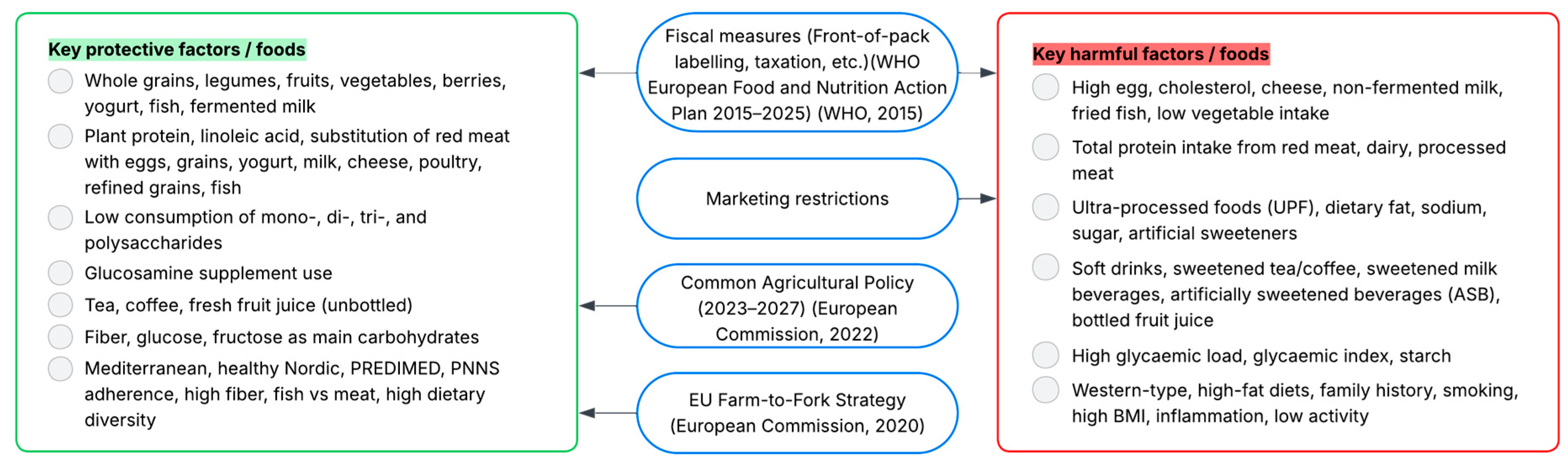

4.1. Policy Recommendations (EU Level)

- Farm-to-Fork/CAP alignment: Use CAP instruments to shift support toward the production, storage, and distribution of legumes, whole grains, and fruit/vegetables, and phase down measures that favor highly processed inputs.

- Front-of-pack labelling & marketing restrictions: Adopt a single interpretive front-of-pack label across MS and set EU minimum standards to restrict marketing of HFSS/UPF to children, allowing MS to go further.

- Fiscal measures (EU guidance; national adoption): Issue EU guidance for evidence-informed SSB excise taxes and encourage earmarking revenues for healthy food subsidies/vouchers in low-income regions; ensure state-aid compatibility and equity monitoring.

- Surveillance & research investment: Fund longitudinal cohorts and dietary assessment standardization in Central & Eastern Europe to address the regional evidence gap through EU4Health/Horizon Europe and with ECDC/EFSA coordination.

4.2. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovács, N.; Shahin, B.; Andrade, C.A.S.; Mahrouseh, N.; Varga, O. Lifestyle and metabolic risk factors, and diabetes mellitus prevalence in European countries from three waves of the European Health Interview Survey. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J.; IDF. Diabetes Atlas 10th Edition Scientific Committee. IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th Edition 537 Million People Worldwide Have Diabetes. 2021. Available online: www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majabadi, H.A.; Solhi, M.; Montazeri, A.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Nejat, S.; Farahani, F.K.; Djazayeri, A. Factors influencing fast-food consumption among adolescents in Tehran: A qualitative study. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e23890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazidi, M.; Speakman, J.R. Association of fast-food and full-service restaurant densities with mortality from cardiovascular disease and stroke, and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Davis, J.A.; Beattie, S.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Loughman, A.; O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.; Berk, M.; Page, R.; Marx, W.; et al. Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bishop, T.R.P.; Imamura, F.; Sharp, S.J.; Pearce, M.; Brage, S.; Ong, K.K.; Ahsan, H.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Beulens, J.W.J.; et al. Meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: An individual-participant federated meta-analysis of 1·97 million adults with 100,000 incident cases from 31 cohorts in 20 countries. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Castor, L.; O’Hearn, M.; Cudhea, F.; Miller, V.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J.; Sharib, J.R.; Cash, S.B.; Barquera, S.; Micha, R.; et al. Burdens of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease attributable to sugar-sweetened beverages in 184 countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Díaz-López, A.; Rosique-Esteban, N.; Ros, E.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Fitó, M.; Serra-Majem, L.; Arós, F.; et al. Legume consumption is inversely associated with type 2 diabetes incidence in adults: A prospective assessment from the PREDIMED study. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Peláez, S.; Montse, F.; Castaner, O. Mediterranean diet effects on type 2 diabetes prevention, disease progression, and related mechanisms. A review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Salvadó, J.; Bulló, M.; Babio, N.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Ibarrola-Jurado, N.; Basora, J.; Estruch, R.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the mediterranean diet: Results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Williams, F.; Bromley, H.; Orton, L.; Hawkes, C.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; O’Flaherty, M.; McGill, R.; Anwar, E.; Hyseni, L.; Moonan, M.; et al. Smorgasbord or symphony? Assessing public health nutrition policies across 30 European countries using a novel framework. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Kuraj, S. Diversity in Food Culture and Consumption Patterns. Survey Results from Seven European Countries. 2022. Available online: www.oslomet.no/en/about/sifo (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Silva, P.; Araújo, R.; Lopes, F.; Ray, S. Nutrition and Food Literacy: Framing the Challenges to Health Communication. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajdar, D.; Lühmann, D.; Fertmann, R.; Steinberg, T.; van den Bussche, H.; Scherer, M.; Schäfer, I. Low health literacy is associated with higher risk of type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study in Germany. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G.; Lampousi, A.M.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Schwedhelm, C.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander, M.; Ballon, A.; Weber, K.S.; Norat, T.; Aune, D.; Schwingshackl, L.; Schlesinger, S. Role of diet in type 2 diabetes incidence: Umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective observational studies. BMJ 2019, 366, l2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjarnahor, R.L.; Javadi Arjmand, E.; Onni, A.T.; Thomassen, L.M.; Perillo, M.; Balakrishna, R.; Sletten, I.S.K.; Lorenzini, A.; Plastina, P.; Fadnes, L.T. Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses on Consumption of Different Food Groups and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Syndrome. J. Nutr. 2025, 155, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.A.S.; Lovas, S.; Mahrouseh, N.; Chamouni, G.; Shahin, B.; Mustafa, E.O.A.; Muhlis, A.N.A.; Njuguna, D.W.; Israel, F.E.A.; Gammoh, N.; et al. Primary Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the European Union: A Systematic Review of Interventional Studies. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, M.T.; Corrêa, C.d.C.; Cassettari, A.J.; Giacomin, L.T.; Faria, A.C.; Moreira, A.P.S.M.; Magalhães, I.; da Cunha, M.O.; Weber, S.A.T.; Zancanella, E.; et al. Is ankyloglossia associated with obstructive sleep apnea? Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 88, S156–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. 2024. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/download/attachments/355599504/JBI%20Manual%20for%20Evidence%20Synthesis%202024.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- NHLBI National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2021, July. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Conklin, A.I.; Monsivais, P.; Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Dietary Diversity, Diet Cost, and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in the United Kingdom: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, P.; Proctor, G.; Driollet, B.; Garcia-Esquinas, E.; Lopez-Garcia, E.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Neyraud, E.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Morzel, M.; Féart, C. The role of overweight in the association between the Mediterranean diet and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A mediation analysis among 21 585 UK biobank participants. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Estigarribia, L.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Díaz-Gutiérrez, J.; Sayón-Orea, C.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Lifestyle behavior and the risk of type 2 diabetes in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippatos, T.D.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Pitaraki, E.; Kouli, G.-M.; Chrysohoou, C.; Tousoulis, D.; Stefanadis, C.; Pitsavos, C.; ATTICA Study Group. Mediterranean diet and 10-year (2002–2012) incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in participants with prediabetes: The ATTICA study. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2016, 13, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidemann, C.; Hoffmann, K.; Spranger, J.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Möhlig, M.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Boeing, H. A dietary pattern protective against type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)—Potsdam Study cohort. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zuurmond, M.G.; van der Schaft, N.; Nano, J.; Wijnhoven, H.A.H.; Ikram, M.A.; Franco, O.H.; Voortman, T. Plant versus animal based diets and insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: The Rotterdam Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montonen, J.; Knekt, P.; Härkänen, T.; Järvinen, R.; Heliövaara, M.; Aromaa, A.; Reunanen, A. Dietary patterns and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 161, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mursu, J.; Virtanen, J.K.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Nurmi, T.; Voutilainen, S. Intake of fruit, berries, and vegetables and risk of type 2 diabetes in Finnish men: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study1–4. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montonen, J.; Knekt, P.; Järvinen, R.; Aromaa, A.; Reunanen, A. Whole-grain and fiber intake and the incidence of type 2 diabetes 1,2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriguer, F.; Colomo, N.; Olveira, G.; García-Fuentes, E.; Esteva, I.; Ruiz de Adana, M.S.; Morcillo, S.; Porras, N.; Valdés, S.; Rojo-Martínez, G. White rice consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.J.; Khaw, K.T.; Sharp, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Lentjes, M.A.H.; Forouhi, N.G.; Luben, R.N. A prospective study of the association between quantity and variety of fruit and vegetable intake and incident type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosti, R.I.; Tsiampalis, T.; Kouvari, M.; Chrysohoou, C.; Georgousopoulou, E.; Pitsavos, C.S.; Panagiotakos, D.B. The association of specific types of vegetables consumption with 10-year type II diabetes risk: Findings from the ATTICA cohort study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, D.B.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Halkjær, J.; Tjønneland, A.; Kilpeläinen, T.O.; Parner, E.T.; Overvad, K. Replacing Red Meat with Other Nonmeat Food Sources of Protein is Associated with a Reduced Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in a Danish Cohort of Middle-Aged Adults. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaguera, D.; Norat, T.; Wark, P.A.; Vergnaud, A.C.; Schulze, M.B.; van Woudenbergh, G.J.; Drogan, D.; Amiano, P.; Molina-Montes, E.; Sánchez, M.J.; et al. Consumption of sweet beverages and type 2 diabetes incidence in European adults: Results from EPIC-InterAct. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Abhari, S.; Luben, R.N.; Powell, N.; Bhaniani, A.; Chowdhury, R.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G.; Khaw, K.T. Dietary intake of carbohydrates and risk of type 2 diabetes: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer-Norfolk study. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-López, A.; Bulló, M.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Fitó, M.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Fiol, M.; Garcia De La Corte, F.J.; Ros, E.; et al. Dairy product consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in an elderly Spanish Mediterranean population at high cardiovascular risk. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, I.; Esberg, A.; Nilsson, L.M.; Jansson, J.H.; Wennberg, P.; Winkvist, A. Dairy product intake and cardiometabolic diseases in Northern Sweden: A 33-year prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajous, M.; Bijon, A.; Fagherazzi, G.; Balkau, B.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F. Egg and cholesterol intake and incident type 2 diabetes among French women. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Männistö, S.; Kontto, J.; Kataja-Tuomola, M.; Albanes, D.; Virtamo, J. High processed meat consumption is a risk factor of type 2 diabetes in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1817–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajous, M.; Tondeur, L.; Fagherazzi, G.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Boutron-Ruaualt, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F. Processed and unprocessed red meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes among French women. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nielen, M.; Feskens, E.J.; Mensink, M.; Sluijs, I.; Molina, E.; Amiano, P.; Ardanaz, E.; Balkau, B.; Beulens, J.W.; Boeing, H.; et al. Dietary protein intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Europe: The EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1854–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagherazzi, G.; Gusto, G.; Affret, A.; Mancini, F.R.; Dow, C.; Balkau, B.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Bonnet, F.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C. Chronic Consumption of Artificial Sweetener in Packets or Tablets and Type 2 Diabetes Risk: Evidence from the E3N-European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 70, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, R.B.; Rauber, F.; Chang, K.; Laura Louzada, M.C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Millett, C.; Vamos, E.P.; Bertazzi Levy, R. Ultra-processed food consumption and type 2 diabetes incidence: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 40, 3608–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfvenborg, J.E.; Andersson, T.; Carlsson, P.O.; Dorkhan, M.; Groop, L.; Martinell, M.; Tuomi, T.; Wolk, A.; Carlsson, S. Sweetened beverage intake and risk of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) and type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 175, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, L.; Imamura, F.; Lentjes, M.A.H.; Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Prospective associations and population impact of sweet beverage intake and type 2 diabetes, and effects of substitutions with alternative beverages. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, A.; di Giuseppe, D.; Orsini, N.; Åkesson, A.; Forouhi, N.G.; Wolk, A. Fish consumption and frying of fish in relation to type 2 diabetes incidence: A prospective cohort study of Swedish men. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woudenbergh, G.J.; van Ballegooijen, A.J.; Kuijsten, A.; Sijbrands, E.J.G.; van Rooij, F.J.A.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Feskens, E.J.M. Eating fish and risk of type 2 diabetes: A population-based, prospective follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2021–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaobelina, K.; Dow, C.; Romana Mancini, F.; Dartois, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Balkau, B.; Bonnet, F.; Fagherazzi, G. Population attributable fractions of the main type 2 diabetes mellitus risk factors in women: Findings from the French E3N cohort. J. Diabetes 2019, 11, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.C.; Arthur, R.; Qin, L.Q.; Chen, L.H.; Mei, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Rohan, T.E.; Qi, Q. Association of Oily and Nonoily Fish Consumption and Fish Oil Supplements With Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Large Population-Based Prospective Study. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barouti, A.A.; Tynelius, P.; Lager, A.; Björklund, A. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: Results from a 20-year long prospective cohort study in Swedish men and women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3175–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuber, J.M.; Vissers, L.E.T.; Verschuren, W.M.M.; Boer, J.M.A.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Sluijs, I. Substitution among milk and yogurt products and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes in the EPIC-NL cohort. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 34, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffers, F.R.; Wijga, A.H.; Verschuren, W.M.M.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Sluijs, I.; Smit, H.A.; Boer, J.M.A. Pure Fruit Juice and Fruit Consumption Are Not Associated with Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes after Adjustment for Overall Dietary Quality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Netherlands (EPIC-NL) Study. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, D.B.; Laursen, A.S.D.; Lauritzen, L.; Tjonneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Jakobsen, M.U. Substitutions between dairy product subgroups and risk of type 2 diabetes: The Danish Diet, Cancer and Health cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluijs, I.; Forouhi, N.G.; Beulens, J.W.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Agnoli, C.; Arriola, L.; Balkau, B.; Barricarte, A.; Boeing, H.; Bueno-De-Mesquita, H.B.; et al. The amount and type of dairy product intake and incident type 2 diabetes: Results from the EPIC-InterAct Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.J.; Forouhi, N.G.; Ye, Z.; Buijsse, B.; Arriola, L.; Balkau, B.; Barricarte, A.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Boeing, H.; Büchner, F.L.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and type 2 diabetes: EPIC-InterAct prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazpe, I.; Beunza, J.J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Mari-Sanchis, A.; Martínez-González, M.Á. Consumo de huevo y riesgo de diabetes tipo 2 en una cohorte mediterránea; el proyecto SUN. Nutr. Hosp. 2013, 28, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.S.; Sharp, S.J.; Luben, R.N.; Khaw, K.T.; Bingham, S.A.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Association between type of dietary fish and seafood intake and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes: The European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC)-Norfolk cohort study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1857–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholdt, H.K.M.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Ellervik, C. Milk intake is not associated with low risk of diabetes or overweight-obesity: A Mendelian randomization study in 97,811 Danish individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noerman, S.; Kärkkäinen, O.; Mattsson, A.; Paananen, J.; Lehtonen, M.; Nurmi, T.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Voutilainen, S.; Hanhineva, K.; Virtanen, J.K. Metabolic Profiling of High Egg Consumption and the Associated Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Middle-Aged Finnish Men. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 63, e1800605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, P.; Vol, S.; Cacès, E.; Born, C.; Chabrolle, C.; Lasfargues, G.; Halimi, J.M.; Tichet, J. Five-year predictive factors of type 2 diabetes in men with impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes Metab. 2007, 33, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Lager, A.; Fredlund, P.; Elinder, L.S. Consumption of fruit and vegetables and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A 4-year longitudinal study among Swedish adults. J. Nutr. Sci. 2020, 9, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzevičienė, L.; Ostrauskas, R. Egg consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1437–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamluk, L.; O’Doherty, M.G.; Orfanos, P.; Saitakis, G.; Woodside, J.V.; Liao, L.M.; Sinha, R.; Boffetta, P.; Trichopoulou, A.; Kee, F. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of incident of type 2 diabetes: Results from the consortium on health and ageing network of cohorts in Europe and the United States (CHANCES). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertiwi, K.; Wanders, A.J.; Harbers, M.C.; Küpers, L.K.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; de Goede, J.; Zock, P.L.; Geleijnse, J.M. Plasma and dietary linoleic acid and 3-year risk of type 2 diabetes after myocardial infarction: A prospective analysis in the Alpha Omega Cohort. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, H.E.K.; Koskinen, T.T.; Voutilainen, S.; Mursu, J.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Kokko, P.; Virtanen, J.K. Intake of different dietary proteins and risk of type 2 diabetes in men: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krachler, B.; Norberg, M.; Eriksson, J.W.; Hallmans, G.; Johansson, I.; Vessby, B.; Weinehall, L.; Lindahl, B. Fatty acid profile of the erythrocyte membrane preceding development of Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008, 18, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, D.B.; Steur, M.; Imamura, F.; Overvad, K.; Schulze, M.B.; Bendinelli, B.; Guevara, M.; Agudo, A.; Amiano, P.; Aune, D.; et al. Replacement of red and processed meat with other food sources of protein and the risk of type 2 diabetes in European populations: The epic-interact study. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2660–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woudenbergh, G.J.; Kuijsten, A.; Tigcheler, B.; Sijbrands, E.J.G.; van Rooij, F.J.A.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Feskens, E.J.M. Meat consumption and its association with C-reactive protein and incident type 2 diabetes: The Rotterdam study. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, I.; Beulens, J.W.; van der A, D.L.; Spijkerman, A.M.; Grobbee, D.E.; van der Schouw, Y.T. Dietary intake of total, animal, and vegetable protein and risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-NL study. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Franco, O.H.; Lamballais, S.; Ikram, M.A.; Schoufour, J.D.; Muka, T.; Voortman, T. Associations of specific dietary protein with longitudinal insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: The Rotterdam Study. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The InterAct Consortium. Association between dietary meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: The EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, K.; Ramne, S.; González-Padilla, E.; Ericson, U.; Sonestedt, E. Associations of carbohydrates and carbohydrate-rich foods with incidence of type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llavero-Valero, M.; Escalada-San Martín, J.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultra-processed foods and type-2 diabetes risk in the SUN project: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2817–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Debras, C.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes among Participants of the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, T.; Sun, D.; Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Heianza, Y.; Qi, L. Glucosamine use, inflammation, and genetic susceptibility, and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study in UK Biobank. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorelli, D.S.; Fagherazzi, G.; Balkau, B.; Touillaud, M.S.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Clavel-Chapelon, F. Differential effects of coffee on the risk of type 2 diabetes according to meal consumption in a French cohort of women: The E3N/EPIC cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresan, U.; Gea, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Carlos, S.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. Substitution of water or fresh juice for bottled juice and type 2 diabetes incidence: The SUN cohort study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Jousilahti, P.; Peltonen, M.; Bidel, S.; Tuomilehto, J. Joint association of coffee consumption and other factors to the risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study in Finland. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 1742–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomilehto, J.; Hu, G.; Bidel, S.; Lindströ, J.; Jousilahti, P. Coffee Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Among Middle-Aged Finnish Men and Women. 2004. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Bidel, S.; Silventoinen, K.; Hu, G.; Lee, D.H.; Kaprio, J.; Tuomilehto, J. Coffee consumption, serum γ-glutamyltransferase and risk of type II diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, M.; Witte, D.R.; Mosdøl, A.; Marmot, M.G.; Brunner, E.J. Prospective study of coffee and tea consumption in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus among men and women: The Whitehall II study. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.; van de Vegte, Y.J.; Verweij, N.; van der Harst, P. Associations of observational and genetically determined caffeine intake with coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dieren, S.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.M.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; van der A, D.L.; Boer, J.M.A.; Spijkerman, A.; Grobbee, D.E.; Beulens, J.W.J. Coffee and tea consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2561–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; Schulze, M.B.; Sharp, S.J.; Guevara, M.; Romaguera, D.; Bendinelli, B.; Salamanca-Fernández, E.; Ardanaz, E.; Arriola, L.; Aune, D.; et al. Estimated Substitution of Tea or Coffee for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Was Associated with Lower Type 2 Diabetes Incidence in Case-Cohort Analysis across 8 European Countries in the EPIC-InterAct Study. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The InterAct Consortium. Tea consumption and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Europe: The EPIC-interact case-cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagherazzi, G.; Vilier, A.; Sartorelli, D.S.; Lajous, M.; Balkau, B.; Clavel-Chapelon, F. Consumption of artificially and sugar-sweetened beverages and incident type 2 diabetes in the Etude Epidé miologique auprè s des femmes de la Mutuelle Gé né rale de l’Education Nationale-European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floegel, A.; Pischon, T.; Bergmann, M.M.; Teucher, B.; Kaaks, R.; Boeing, H. Coffee consumption and risk of chronic disease in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Germany study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montonen, J.; Jä, R.; Knekt, P.; Heliö, M.; Reunanen, A. Consumption of Sweetened Beverages and Intakes of Fructose and Glucose Predict Type 2 Diabetes Occurrence 1. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, I.; Beulens, J.W.J.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; van der A, D.L.; Buckland, G.; Kuijsten, A.; Schulze, M.B.; Amiano, P.; Ardanaz, E.; Balkau, B.; et al. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and digestible carbohydrate intake are not associated with risk of type 2 diabetes in eight European countries. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, I.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; van der A, D.L.; Spijkerman, A.M.; Hu, F.B.; Grobbee, D.E.; Beulens, J.W. Carbohydrate quantity and quality and risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Netherlands (EPIC-NL) study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonpor, J.; Petermann-Rocha, F.; Parra-Soto, S.; Pell, J.P.; Gray, S.R.; Celis-Morales, C.; Ho, F.K. Types of diet, obesity, and incident type 2 diabetes: Findings from the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cea-Soriano, L.; Pulido, J.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Santos, J.M.; Mata-Cases, M.; Díez-Espino, J.; Ruiz-García, A.; Regidor, E. Mediterranean diet and diabetes risk in a cohort study of individuals with prediabetes: Propensity score analyses. Diabet. Med. 2021, 39, e14768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, M.; Turati, F.; Lagiou, P.; Trichopoulos, D.; Augustin, L.S.; la Vecchia, C.; Trichopoulou, A. Mediterranean diet and glycaemic load in relation to incidence of type 2 diabetes: Results from the Greek cohort of the population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Diabetologia 2013, 56, 2405–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, K.; Schwingshackl, L.; Floegel, A.; Schwedhelm, C.; Stelmach-Mardas, M.; Wittenbecher, C.; Galbete, C.; Knüppel, S.; Schulze, M.B.; Boeing, H. Gaussian graphical models identified food intake networks and risk of type 2 diabetes, CVD, and cancer in the EPIC-Potsdam study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalazi, E.; Drake, I.; Wirfält, E.; Orho-Melander, M.; Sonestedt, E. A high diet quality based on dietary recommendations is not associated with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes in the malmö diet and cancer cohort. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Rebouillat, P.; Payrastre, L.; Allès, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Srour, B.; Bao, W.; Touvier, M.; Galan, P.; et al. Prospective association between organic food consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: Findings from the NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Chaltiel, D.; Fezeu, L.K.; Baudry, J.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Galan, P.; Deschamps, V.; Touvier, M.; Julia, C.; Hercberg, S. Association between adherence to the French dietary guidelines and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Nutrition 2021, 84, 111107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markanti, L.; Ibsen, D.B.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Dahm, C.C. Adherence to the Danish food-based dietary guidelines and risk of type 2 diabetes: The Danish diet, cancer, and health cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoppidan, S.A.; Kyrø, C.; Loft, S.; Helnæs, A.; Christensen, J.; Hansen, C.P.; Dahm, C.C.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A.; Olsen, A. Adherence to a healthy Nordic food index is associated with a lower risk of type-2 diabetes—The Danish diet, cancer and health cohort study. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8633–8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Marfi, R.; Levantesi, G.; Silletta, M.G.; Tavazzi, L.; Tognoni, G.; Valagussa, F.; Marchioli, R. Incidence of new-onset diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in patients with recent myocardial infarction and the eff ect of clinical and lifestyle risk factors. Lancet 2007, 370, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The InterAct Consortium. Adherence to predefined dietary patterns and incident type 2 diabetes in European populations: EPIC-InterAct Study. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijsse, B.; Boeing, H.; Drogan, D.; Schulze, M.B.; Feskens, E.J.; Amiano, P.; Barricarte, A.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Fagherazzi, G.; et al. Consumption of fatty foods and incident type 2 diabetes in populations from eight European countries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.S.; Forouhi, N.G.; Kuijsten, A.; Schulze, M.B.; van Woudenbergh, G.J.; Ardanaz, E.; Amiano, P.; Arriola, L.; Balkau, B.; Barricarte, A.; et al. The prospective association between total and type of fish intake and type 2 diabetes in 8 European countries: EPIC-InterAct study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The InterAct Consortium. The Association between Dietary Energy Density and Type 2 Diabetes in Europe: Results from the EPIC-InterAct Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, M.B.; Schulz, M.; Heidemann, C.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Hoffmann, K.; Boeing, H. Carbohydrate intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, R.K.; Harding, A.H.; Wareham, N.J.; Griffin, S.J. Do simple questions about diet and physical activity help to identify those at risk of Type 2 diabetes? Diabet. Med. 2007, 24, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, K.; Ahlqvist, E.; Alfredsson, L.; Groop, L.; Hjort, R.; Löfvenborg, J.E.; Tuomi, T.; Carlsson, S. Combined lifestyle factors and the risk of LADA and type 2 diabetes—Results from a Swedish population-based case-control study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 174, 108760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; de La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Nunez-Cordoba, J.M.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Beunza, J.J.; Vazquez, Z.; Benito, S.; Tortosa, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008, 336, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Aveyard, P.; Ambrosini, G.L.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Papier, K.; Carter, J.; Piernas, C. Associations Between Dietary Patterns and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: Prospective Cohort Study of 120,343 UK Biobank Participants. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguaras, S.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Carlos, S.; de La Rosa, P.; Martínez-González, M.A. May the Mediterranean diet attenuate the risk of type 2 diabetes associated with obesity: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassou, C.; Yannakoulia, M.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Chrysohoou, C.; Pitsavos, C.; Cropley, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Irrational beliefs, dietary habits and 10-year incidence of type 2 diabetes; the attica epidemiological study (2002–2012). Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2021, 17, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvari, M.; Tsiampalis, T.; Kosti, R.I.; Naumovski, N.; Chrysohoou, C.; Skoumas, J.; Pitsavos, C.S.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Mantzoros, C.S. Quality of plant-based diets is associated with liver steatosis, which predicts type 2 diabetes incidence ten years later: Results from the ATTICA prospective epidemiological study. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, N.; Mühlenbruch, K.; Meidtner, K.; Boeing, H.; Stefan, N.; Schulze, M.B. Characterization of metabolically unhealthy normal-weight individuals: Risk factors and their associations with type 2 diabetes. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2015, 64, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, C.; Mangin, M.; Balkau, B.; Affret, A.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Bonnet, F.; Fagherazzi, G. Fatty acid consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: An 18-year follow-up in the female E3N (Etude Epidémiologique auprès des femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale) prospective cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tertsunen, H.M.; Hantunen, S.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Virtanen, J.K. Adherence to a healthy Nordic diet and risk of type 2 diabetes among men: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3927–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.H.; Johansson, I.; Rolandsson, O.; Wennberg, P.; Fhärm, E.; Weinehall, L.; Griffin, S.J.; Simmons, R.K.; Norberg, M. Healthy behaviours and 10-year incidence of diabetes: A population cohort study. Prev. Med. 2015, 71, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayner, B.; Kaur, G.; Keske, M.A.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Piernas, C.; Livingstone, K.M. Dietary Patterns Characterized by Fat Type in Association with Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Longitudinal Study of UK Biobank Participants. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 3570–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming-Jie, D.; Dekker, L.H.; Carrero, J.J.; Navis, G. Blood lipids-related dietary patterns derived from reduced rank regression are associated with incident type 2 diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4712–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, A.M.; Axelsen, M.; Churuangsuk, C.; Hermansen, K.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Kahleova, H.; Khan, T.; Lean, M.E.J.; Mann, J.I.; Pedersen, E.; et al. Evidence-based European recommendations for the dietary management of diabetes. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 965–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, S.; Feehan, J.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Wilson, K.; Plebanski, M.; Scott, D.; Hebert, J.R.; Shivappa, N.; Mousa, A.; George, E.S.; et al. Higher Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Improved Insulin Sensitivity and Selected Markers of Inflammation in Individuals Who Are Overweight and Obese without Diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, F.; Gruber, J.R.; Ruf, A.; Edwin Thanarajah, S.; Reif, A.; Matura, S. Exploring the Link between Lifestyle, Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance through an Improved Healthy Living Index. Nutrients 2024, 16, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobo Cejudo, M.G.; Cruijsen, E.; Heuser, C.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Voortman, T.; Geleijnse, J.M. Dairy consumption and 3-year risk of type 2 diabetes after myocardial infarction: A prospective analysis in the alpha omega cohort. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; van Woudenbergh, G.J.; Oude Elferink, S.J.W.H.; Singh-Povel, C.M.; Hofman, A.; Dehghan, A.; Franco, O.H.; Feskens, E.J.M. Intake of different types of dairy and its prospective association with risk of type 2 diabetes: The Rotterdam Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 26, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struijk, E.A.; Heraclides, A.; Witte, D.R.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Toft, U.; Lau, C.J. Dairy product intake in relation to glucose regulation indices and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseinovic, E.; Winkvist, A.; Slimani, N.; Park, M.; Freisling, H.; Boeing, H.; Buckland, G.; Schwingshackl, L.; Weiderpass, E.; Rostgaard-Hansen, A.; et al. Meal patterns across ten European countries—Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) calibration study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2769–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krznarić, Ž.; Karas, I.; Kelečić, D.L.; Bender, D.V. The Mediterranean and Nordic Diet: A Review of Differences and Similarities of Two Sustainable, Health-Promoting Dietary Patterns. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 683678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marí-Sanchis, A.; Beunza, J.J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Toledo, E.; Basterra Gortariz, F.J.; Serrano-Martínez, M.; Martínez-González, M.A. Olive oil consumption and incidence of diabetes mellitus, in the Spanish sun cohort. Nutr. Hosp. 2011, 26, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumm-Kreuter, D. Comparison of the Eating and Cooking Habits of Northern Europe and the Mediterranean Countries in the Past, Present and Future. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2001, 71, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Masset, G.; Verberne, L.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Brunner, E.J. Consumption of dairy products and associations with incident diabetes, CHD and mortality in the Whitehall II study. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. 2020. Available online: https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/Qlik_Downloads/Jobs-Growth-sources.htm (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289051231 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- European Commission. Common Agricultural Policy for 2023–2027 28 Cap Strategic Plans at a Glance. 2022. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/cap-overview/cap-glance_en (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

| Exposure Category | No. Studies | Countries | Effect Range | Factors | Follow-Up Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Including All Studies | Including Just High-Quality Studies | |||||

| Whole & minimally processed foods | 30 | Finland; France; Spain; Germany; Italy; UK; Sweden; Lithuania; Netherlands; Denmark; Greece |

| Direction maintained | Berry, whole grains, legumes, white rice, egg, yogurt, fish, fruits, vegetables, fermented milk intake | 1.8–20 years |

| Direction maintained

| High egg, cholesterol, cheese and non-fermented milk intake, fried fish and shellfish, low dairy and vegetable consumption, metabolic factors (BMI ≥ 30, IFG, IGT) | ||||

| Animal-based & Protein-Rich Foods | 12 | Netherlands; Finland; Sweden; France; Denmark; Germany, Italy; Spain; UK; Greece; Norway | HR 0.54–0.91 [68,69,70,71] | Direction maintained HR 0.80–0.95 [68] | Plant protein, linoleic acid, SFA 15:0 and 17:0 intake, substitution of red meat (with eggs, whole grains, yogurt, milk, cheese, poultry, refined grains, fish) | 3.4–19.3 years |

| Direction maintained

| Total protein intake (red meat, fish, dairy, processed meat) | ||||

| Processed & Discretionary Foods | 6 | Sweden; Spain; France; UK | HR 0.73–0.80 [76] | ND | Low consumption of mono-, di-, tri- and polysaccharides | 5.4–18.4 years |

| HR 1.05–2.17 [46,47,76,77,78] | Direction maintained HR 1.12–2.17 [46,47,77,78] | UPF, dietary fat, sodium, and sugar intake, frequent use of artificial sweeteners | ||||

| Composite & Special-purpose foods | 1 | UK | HR 0.81–0.88 [79] | ND | Glucosamine supplement use | 8.1 years |

| Beverages | 16 | France; Spain; Sweden; Germany; Finland; UK; Netherlands; Denmark; Italy | HR 0.39–0.93 [49,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] | Direction maintained HR 0.64 (≥7 cups/day coffee) [84] | Tea, coffee, fresh fruit juice (as substitution for the bottled) | 6.9–13.4 years |

| Direction maintained HR 1.18–1.68 [90,91,92] | Soft drinks, sweetened tea/coffee, sweetened milk beverages, artificially sweetened beverages (ASB), and bottled fruit juice | ||||

| Carbohydrates | 4 | UK; Netherlands; Sweden; France; Italy; Germany | HR 0.82–0.97 [39,93,94] | Direction maintained HR 0.82–0.85 [39] | Fiber, glucose and fructose as main carbohydrates | 6.3–12 years |

| HR 1.05–1.38 [93,94] | ND | Glycemic load, glycemic index and starch | ||||

| Dietary Patterns | 36 | UK; Spain; Greece; Germany; Sweden; France; Netherlands; Denmark; Finland; Italy |

| Direction maintained

| Mediterranean diet, healthy Nordic food index, PREDIMED dietary pattern, PNNS guideline adherence, healthy lifestyle score, fiber adherence, fish vs. meat, high dietary diversity |

|

| Direction maintained | Western-type diet, unhealthy patterns (high-fat diet, family history, smoking, high BMI, antihypertensive meds, high inflammation, low physical activity, high n-3 PUFA intake) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz-Benavides, D.A.; Muhlis, A.N.A.; Chamouni, G.; Charles, R.; Nigatu, D.T.; Ben Khadra, J.; Israel, F.E.A.; Shehab, B.; Tarek, G.L.; Sharshekeeva, A.; et al. Nutritional Determinants of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the European Union: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3507. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223507

Díaz-Benavides DA, Muhlis ANA, Chamouni G, Charles R, Nigatu DT, Ben Khadra J, Israel FEA, Shehab B, Tarek GL, Sharshekeeva A, et al. Nutritional Determinants of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the European Union: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(22):3507. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223507

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz-Benavides, Daniela Alejandra, Abdu Nafan Aisul Muhlis, Ghenwa Chamouni, Rita Charles, Digafe Tsegaye Nigatu, Jomana Ben Khadra, Frederico Epalanga Albano Israel, Bashar Shehab, Gabriella Laila Tarek, Aidai Sharshekeeva, and et al. 2025. "Nutritional Determinants of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the European Union: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 17, no. 22: 3507. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223507

APA StyleDíaz-Benavides, D. A., Muhlis, A. N. A., Chamouni, G., Charles, R., Nigatu, D. T., Ben Khadra, J., Israel, F. E. A., Shehab, B., Tarek, G. L., Sharshekeeva, A., Gammoh, N., Habte, T. T., Chandrika, N., Alshakhshir, F. K., Mahrouseh, N., Andrade, C. A. S., Lovas, S., & Varga, O. (2025). Nutritional Determinants of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the European Union: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 17(22), 3507. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223507