Abstract

Background/Objectives: The increasing interest in functional foods has highlighted the need to better understand consumer perceptions and their influence on dietary behaviours. This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods (QAPAF) and apply it to a Portuguese adult population to explore associations with sociodemographic and lifestyle factors. Methods: Participants were recruited through convenience sampling; the achieved sample was predominantly female and highly educated. The 17-item QAPAF was assessed through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha), and test–retest reliability. Associations between QAPAF scores and participant characteristics were analysed using non-parametric tests. Results: EFA supported a four-factor structure, explaining 58.8% of total variance. Internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.70), and test–retest analysis (n = 25) showed no significant score differences, indicating temporal stability. QAPAF scores were significantly higher among participants with higher education and among non-smokers and non-drinkers. No associations were found with sex, BMI, or income. Participants with correct understanding of functional foods were more likely to reject misconceptions and express trust in professional recommendations. Conclusions: The QAPAF is a valid and reliable tool for assessing functional food perceptions. Its application provides insights into consumer attitudes and may support the design of targeted food literacy interventions. Generalizability is limited by the convenience sampling and by the predominance of female and highly educated participants; external validation in more diverse samples and cultural contexts is warranted.

1. Introduction

Functional foods have received increasing attention over the past two decades due to their potential role in promoting health and preventing disease [1,2,3]. Defined as foods that, beyond their basic nutritional value, exert beneficial physiological effects when consumed as part of a regular diet, they have gained prominence in scientific research, food innovation, and health communication strategies [4,5]. In Europe, regulatory frameworks such as Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 have established strict criteria for the use of health and nutrition claims, reflecting the need to safeguard consumer protection and ensure informed decision-making [6,7].

Although functional foods are widely available across European markets, consumer acceptance and use remain heterogeneous, influenced not only by factual knowledge, but also by perceptions, attitudes, trust in health information, and broader beliefs about food and health [8,9,10]. Understanding these perceptions is therefore essential for developing public health messages and supporting the effective integration of functional foods into healthy dietary patterns [11,12].

Previous research has shown that consumers generally hold favourable views regarding the benefits of functional foods, especially when these are associated with natural ingredients or traditional diets such as the Mediterranean [13,14]. However, persistent concerns regarding processing, artificiality, cost, and the credibility of health claims often contribute to ambivalence or rejection [15,16]. In addition, confusion surrounding the term “functional”, often conflated with supplements or fortified products, may obscure understanding and limit adoption [17,18]. Sociocultural norms, education, and personal health motivation also play key roles in shaping consumer attitudes and intentions [19,20].

In this context, the concept of food literacy has gained growing importance. It includes not only the ability to access and understand nutritional information, but also the capacity to critically evaluate claims and make informed dietary decisions [21,22,23]. Assessing perceptions of functional foods is thus a crucial step in identifying knowledge gaps, evaluating public trust, and developing targeted communication and education strategies adapted to different population groups [24,25].

Despite the increasing relevance of the topic, few validated tools are available to assess consumer perceptions of functional foods in a multidimensional and culturally sensitive way. In our previous work, we developed the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods (QAPAF) to address this gap [26,27]. Grounded in a theoretical model of food perception, the QAPAF integrates cognitive, affective and behavioural dimensions. In our previous work, we used this instrument in descriptive studies of functional food perception [27]. However, its psychometric properties had not yet been systematically validated, limiting its application in wider surveillance and intervention contexts.

In recent years, the functional food market in Portugal has shown consistent growth, particularly in urban areas and among health-conscious consumers [28,29]. Nonetheless, national data on consumer knowledge, trust, and usage patterns remain scarce. A recent survey by the Directorate-General of Health (Direção-Geral da Saúde) highlighted persistent gaps in food literacy, especially in interpreting nutritional claims, with scepticism towards functional ingredients being particularly marked among older adults and those with lower education [30,31]. Although these products are increasingly present in the retail environment, their integration into daily food practices remains uneven, reinforcing the need for robust tools to monitor perceptions and identify barriers to adoption [32].

Across Europe and other regions, multiple studies have examined how consumers perceive functional foods, identifying facilitators such as health motivation, trust in professional recommendations, and perceived naturalness, and barriers including price, processing, and the credibility of health claims [33,34,35]. Building on this literature, we expected to confirm a four-component structure for the QAPAF with acceptable internal consistency and temporal stability, and to observe higher scores among participants with higher education and health-oriented behaviours. The novelty of this work is threefold: (i) it provides the first comprehensive psychometric validation of the QAPAF in Portuguese adults; (ii) it combines validation with an application that links perception scores to sociodemographic and lifestyle variables; and (iii) it offers an English version and practical scoring guidance to facilitate use in population surveys and intervention evaluation, building on preliminary development work [27].

This study was therefore conducted in two parts. Study 1 aimed to validate the psychometric properties of the QAPAF, including its factor structure, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability in a sample of Portuguese adults. Study 2 applied the instrument to describe consumer perceptions and explore associations with sociodemographic and behavioural variables, with particular attention to conceptual understanding of functional foods and engagement in health-promoting behaviours.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Psychometric Evaluation of the QAPAF

2.1.1. Participants and Procedures

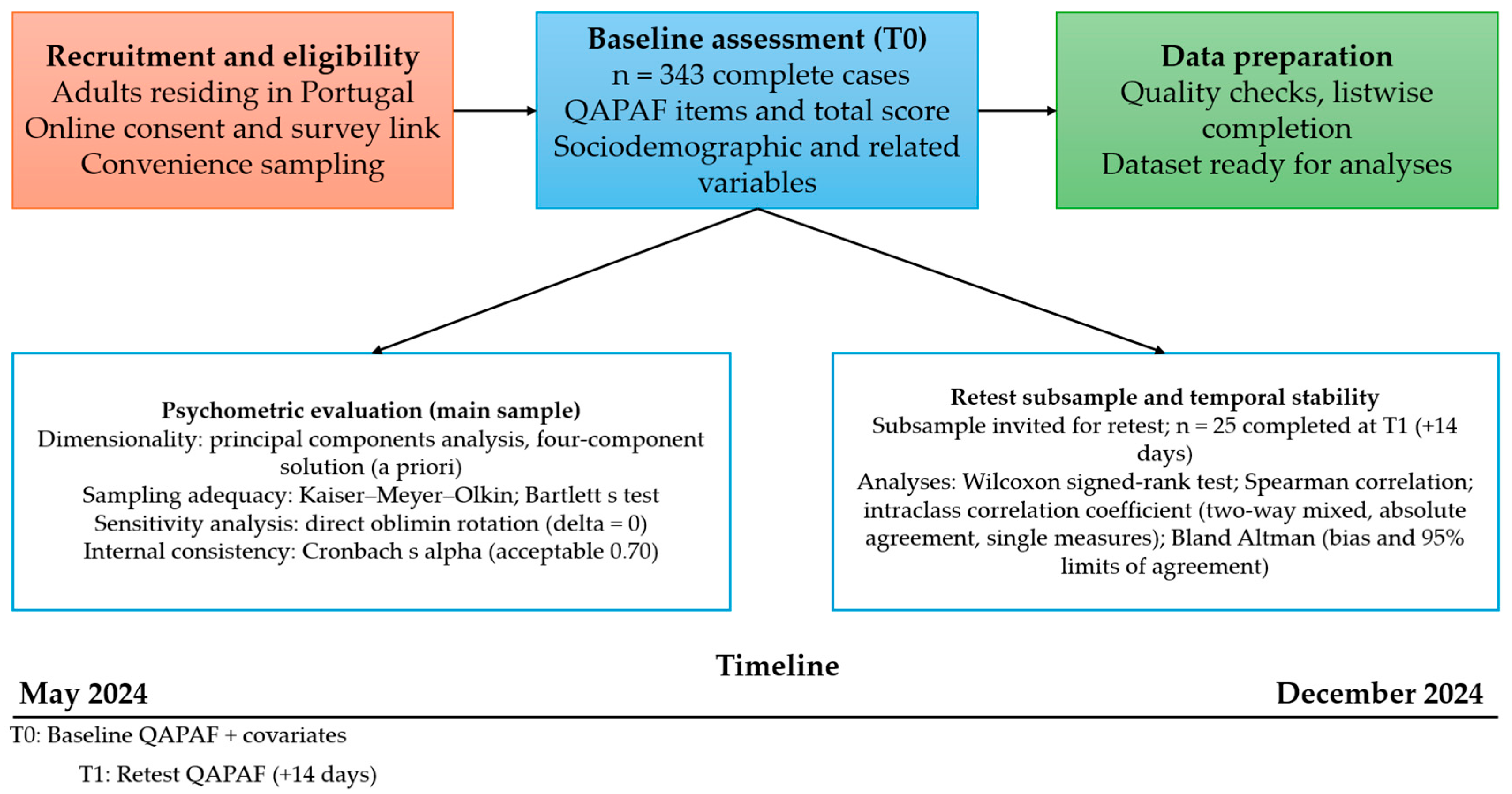

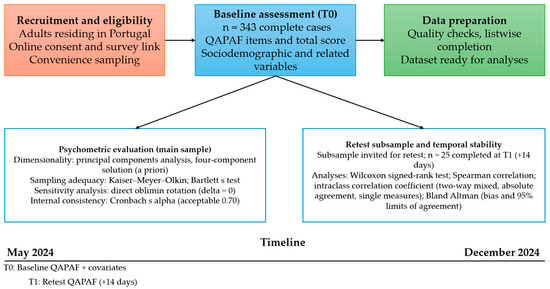

A cross-sectional study was conducted with a convenience sample of 343 adults residing in Portugal. Inclusion criteria included age 18 years or older and proficiency in reading and understanding the Portuguese language. Data collection took place between May and December 2024 using an online questionnaire distributed via Google Forms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design and timeline. Adult participants in Portugal completed the baseline online assessment (T0; n = 343 complete cases). Psychometric analyses were conducted in the main sample (PCA, four-component solution; Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin; Bartlett p < 0.001), with a sensitivity analysis using direct oblimin rotation. A subsample (n = 25) completed a retest after 14 days (T1) for temporal stability analyses (Wilcoxon, Spearman correlation, intraclass correlation coefficient two-way mixed absolute agreement, single measures; Bland–Altman). Abbreviation: QAPAF: Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods.

The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [36] and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidade Lusófona (reference: P04-24, 30 April 2024). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and informed consent was obtained electronically before beginning the questionnaire. Participants were free to withdraw at any time without consequences.

The sample size was determined based on established methodological recommendations for factor analysis, which suggest using between 10 and 20 participants per item to ensure the statistical robustness of parameter estimates [37]. Considering the 17 items of the QAPAF, the sample of 340 participants was deemed adequate for the psychometric analysis. Study 2 used the same sample as Study 1. The same inclusion criteria and ethical procedures previously described were applied.

2.1.2. Instrument

The initial version of the QAPAF [26] included 17 items, presented in randomised order and rated on a five-point Likert-type scale: 1 = “Strongly disagree”, 2 = “Disagree”, 3 = “Neither agree nor disagree”, 4 = “Agree”, and 5 = “Strongly agree”. An additional response option (“I don’t know”) was available and treated as a neutral response (value = 3). Items 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 14, 15, and 16 were negatively worded and were reverse-coded during data processing to ensure that higher scores consistently reflected more favourable perceptions of functional foods. The total score, obtained by summing the scores of all 17 items, ranges from 17 to 85. Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes and greater confidence towards functional foods. To minimise interpretation bias, all participants were presented with a standardised definition of functional foods prior to completing the scale. Before answering the QAPAF, all participants were presented with a standardised definition of functional foods to ensure consistent interpretation and minimise bias. The definition was as follows: A functional food is one that, beyond its appropriate nutritional effects, exerts a beneficial effect on one or more body functions, contributing to improved health and well-being and/or reducing the risk of disease. It is consumed as part of a normal diet and not in the form of pills, capsules, or dietary supplements [38]. No brand names or examples were included in the questionnaire to avoid marketing influence. The full list of items and the English version of the QAPAF are provided in the Supplementary Material (Table S1).

2.1.3. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0. Descriptive statistics were computed for all items and total scores. Dimensionality was examined with principal components analysis (PCA); the primary unrotated solution is reported to align with the original instrument and to present the partition of total variance. The number of factors was prespecified as four, grounded in the instrument’s conceptual model and the original version. Sampling adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Communalities, eigenvalues, and the scree plot were inspected. As an exploratory check, factor retention followed the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue > 1) and visual inspection of the scree plot, which were consistent with the prespecified four-factor structure. Loadings ≥ 0.40 were considered salient. Internal consistency was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha (acceptable ≥ 0.70). Corrected item–total correlations and the impact of removing each item on overall reliability were examined [39]. For transparency, a sensitivity analysis with oblique rotation (oblimin) was conducted given plausible correlations among dimensions.

2.1.4. Test–Retest Reliability

Test–retest reliability was assessed in a subsample of 25 participants who completed the questionnaire again after a two-week interval. Although small, this sample size is consistent with previous studies using subsamples of 20–30 individuals for preliminary assessments of temporal stability in similar psychometric contexts [40]. Paired scores were compared with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test; we report the Z statistic, two-tailed p value, and the effect size r = Z/N∗, where N∗ is the number of non-zero paired differences. Rank-order association was examined with Spearman’s ρ. Absolute agreement was quantified using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) from a two-way mixed-effects model with absolute-agreement definition and single-measures unit, with 95% confidence intervals. Agreement was also visualised with Bland–Altman plots, reporting mean bias and 95% limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96 × SD of the differences) and checking proportional bias by regressing differences on the mean. All tests were two-tailed with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 [39].

2.2. Application of the QAPAF in the Portuguese Population

2.2.1. Questionnaire Structure

In addition to the QAPAF, the questionnaire included the following variables: Sociodemographic characteristics: sex, age, nationality, marital status, educational attainment, region and type of residence, occupation or field of study, and household income; Anthropometric data: self-reported height and weight, used to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI), classified according to WHO criteria [41]; Health conditions: self-reported chronic illnesses. Before answering the QAPAF, all participants were presented with the same standardised definition of functional foods used in Study 1, to ensure conceptual clarity and consistency across responses. In addition to the QAPAF, the questionnaire included sociodemographic, anthropometric, and health-related variables. As in Study 1, all negatively worded QAPAF items were reverse-coded so that higher scores consistently reflected more favourable perceptions. The total score, ranging from 17 to 85, served as an overall index of functional food perception [26].

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were summarised using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as normality assumptions were not met (Shapiro–Wilk test). Group comparisons were performed using non-parametric tests: Mann–Whitney U test for continuous or ordinal variables; Chi-square, likelihood ratio, or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables; Spearman’s correlation for continuous or ordinal variables. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All analyses followed methodological recommendations for non-parametric data in health sciences [39].

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric Evaluation of the QAPAF

Prior to factor extraction, sampling adequacy was assessed. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.821, indicating meritorious adequacy for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (χ2 (136) = 2002.80, p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrix was appropriate for factor extraction.

An EFA was performed using principal component analysis without rotation, and the decision to extract four components was theoretically driven, in accordance with the original structure of the QAPAF. All 17 items were retained. The four-component solution explained 58.8% of the total variance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total variance explained by the four retained factors of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods (n = 343).

The communalities reflect the proportion of variance in each item explained by the retained components. As shown in Supplementary Table S2, values ranged from 0.30 (Item 17) to 0.75 (Item 3), indicating that all items contributed meaningfully to the factor structure. Most items presented communalities above 0.45, supporting their inclusion in the final model. The scree plot (Supplementary Figure S1) also supported the retention of four components, with a visible inflection point observed after the fourth factor

The total scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70. Most item-total correlations were satisfactory. However, Item 13 and Item 16 showed negative or weak corrected item-total correlations. Despite this, removing these items did not significantly improve reliability, and they were retained to preserve the theoretical consistency and content validity of the questionnaire (Supplementary Table S3).

In a sensitivity analysis using oblique rotation (direct oblimin, delta = 0), sampling adequacy was good (KMO = 0.821), and Bartlett’s test was significant, χ2(136) = 2002.796, p < 0.001. The four-component solution accounted for 58.8% of the variance and remained conceptually stable. Inter-factor correlations were small in magnitude (|r| ≤ 0.17). Salient pattern loadings (≥0.40) mapped as follows: Component 1 included items 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 11, and 15; Component 2 included items 12, 16, and 17, with item 9 showing a cross-loading; Component 3 included items 1, 8, and 13; and Component 4 was driven by item 3. One item showed low communality (item 17 = 0.301). Full pattern and structure matrices, the factor correlation matrix, and the scree plot are available in Supplementary Table S4 and Figure S2.

In the retest subsample (n = 25), test and retest totals were identical for every participant. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test returned Z = 0 and p = 1.000, with 0 negative ranks, 0 positive ranks, and 25 ties; the effect size was r = 0.00. Spearman’s correlation was ρ = 1.00 (p not estimable in SPSS under perfect identity). The two-way mixed, absolute-agreement ICC (single measures) was 1.00; confidence intervals and the F test were not estimable for the same reason (Table 2). The Bland–Altman plot showed zero mean bias and zero limits of agreement, reflecting null differences across time points (Supplementary Figure S3).

Table 2.

Test–retest agreement of Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods total score (n = 25).

3.2. Application of the QAPAF: Perceptions of Functional Foods

Table 3 presents the distribution of sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics of participants according to biological sex and their understanding of functional foods. The final sample comprised 343 participants, predominantly female (73.8%), with a median age of 31.0 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 23.0–45.0 years). Most participants reported living in urban areas (82.5%) and resided outside the Lisbon metropolitan area (57.1%). Regarding marital status, 62.4% were married. In terms of education, 61.5% had completed higher education, while 38.5% had completed up to the 12th grade. Among those who provided information on their field of study or professional area (n = 213), 26.5% were in health-related areas. The median monthly family income was €2400 (IQR: €1500–€3000). Based on self-reported height and weight, the median Body Mass Index (BMI) was 22.9 kg/m2 (IQR: 20.7–25.6), with 67.6% classified as having low or normal weight and 32.4% as overweight. Regarding health status, 39.6% reported having at least one chronic condition or disease. Lifestyle behaviours indicated that 14.9% were smokers, 48.4% reported consuming alcoholic beverages, and 78.6% consumed caffeinated beverages such as coffee or energy drinks.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Characteristics of the Participants According to Biological Sex and Understanding of Functional Foods (n = 343).

No statistically significant differences were observed in the understanding of functional foods between males and females (p = 0.244). Participants identifying as male were significantly older than females (median age: 37.0 vs. 29.0 years; p = 0.041), had a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption (61.4% vs. 38.6%; p = 0.025), and reported higher monthly family income (median: €2500 vs. €2000; p = 0.030). Males also presented a significantly higher median BMI compared to females (24.6 vs. 22.5 kg/m2; p = 0.004).

Regarding marital status, a significantly greater proportion of females were married compared to males (66.0% vs. 52.2%; p = 0.020). A higher proportion of men resided in Lisbon compared to other regions (p = 0.019) and were more frequently working in health-related professional areas (p = 0.014). No other statistically significant differences were found in the remaining sociodemographic or lifestyle variables by sex. When stratified by the level of understanding of functional foods, no statistically significant associations were found with any sociodemographic or lifestyle variables. This suggests that knowledge regarding functional foods was relatively evenly distributed across groups regardless of age, sex, education level, BMI, or health-related behaviours.

Table 4 displays the distribution of participants’ responses to a series of statements about functional foods, using a 5-point Likert scale. Most participants agreed that functional foods should be consumed as part of a varied diet, with 39.7% agreeing and 26.2% strongly agreeing. The majority disagreed with the statement that functional foods are useless for healthy individuals (69.7%). Regarding the belief that functional foods can repair damage from an unhealthy diet, 39.7% of participants neither agreed nor disagreed, while 31.8% agreed. Taste was not generally perceived as a barrier, with only 8.1% agreeing or strongly agreeing that functional foods do not taste good.

Table 4.

Distribution of Participants’ Responses to Statements about Functional Foods (n = 343).

No statistically significant differences were found in response distributions between male and female participants (p > 0.05 for all items). Therefore, only the comparisons according to correctness of functional food understanding are reported.

Three statements revealed statistically significant associations with participants’ level of knowledge: the perception that functional foods are unnecessary (p = 0.027), with higher disagreement among those with correct understanding; the belief that functional foods are only for the elderly, sick, or children (p = 0.005), where participants with correct knowledge more frequently disagreed; trust in functional foods when recommended by health professionals (p = 0.019), with greater agreement among those with correct knowledge.

Overall, responses indicate a favourable perception of functional foods, especially in terms of their safety, effectiveness, and contribution to well-being. However, some scepticism remains regarding advertising claims and perceived cost.

Table 5 presents the association between sociodemographic and lifestyle variables and QAPAF scores. Overall, the median QAPAF score was similar across most subgroups, with no statistically significant differences observed according to sex, marital status, region or type of residence, field of study, body mass index classification, or presence of chronic conditions (p > 0.05).

Table 5.

Association between Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Characteristics and Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods Score.

Participants with higher education reported significantly higher QAPAF scores compared to those with education up to the 12th grade (59.0 [55.0–64.0] vs. 58.0 [52.0–61.8]; p = 0.010). Similarly, non-smokers scored higher than smokers (59.0 [54.0–64.0] vs. 57.0 [50.5–60.0]; p = 0.008), and participants who did not consume alcoholic beverages had higher scores than those who did (59.0 [53.3–64.0] vs. 57.0 [53.0–61.0]; p = 0.020).

No significant correlations were found between QAPAF scores and age (r = −0.008; p = 0.883), BMI (r = 0.050; p = 0.407), or monthly family income (r = −0.058; p = 0.408).

4. Discussion

This study contributes to the understanding of how functional foods are perceived by adults in Portugal by re-evaluating the psychometric properties of the QAPAF and applying it in a population-based sample. Together, the two studies offer a comprehensive assessment of the instrument’s validity and provide new insights into how knowledge, beliefs, and lifestyle factors influence consumer attitudes towards functional foods [1,42,43].

4.1. Psychometric Evaluation of the QAPAF

The findings from Study 1 confirmed the theoretical four-factor model of the QAPAF, encompassing perceived benefits, perceived necessity, trust in efficacy, and safety concerns. These results support the multidimensional nature of consumer perception and are consistent with previous literature that highlights the complexity of how functional foods are understood and evaluated [4,26,44]. The proportion of variance explained (58.8%) and the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70) indicate that the QAPAF is a psychometrically sound tool for assessing perceptions at the population level [27]. Temporal stability was assessed in a subsample of 25 participants who completed the questionnaire again after a two-week interval. Test and retest totals were identical for all participants (Wilcoxon signed-rank test: Z = 0, p = 1.000; effect size r = 0.00), indicating point-by-point agreement over the two-week interval. Because there were no between-time differences, uncertainty for ρ and ICC could not be estimated, which limits assessment of measurement error. Larger samples and settings with natural within-person fluctuation would yield more informative reliability estimates. We also recommend complementing rank-based tests with absolute-agreement metrics and Bland–Altman analysis in future work. These results may also reflect the inherently dynamic nature of food perception, which can be influenced by exposure to media, marketing strategies, public health campaigns, or personal experiences [17,45,46]. Still, the observed stability supports the potential utility of the QAPAF for monitoring perception changes over time, particularly in the context of educational or behavioural interventions [47].

There is no single gold-standard instrument for functional food perception against which criterion validity could be established. We therefore followed recognised standards for health status questionnaires, assessing content validity, internal consistency, structural validity by exploratory factor analysis, and test–retest reliability in line with published quality criteria (e.g., Terwee and colleagues [40]). The QAPAF is feasible for population studies because it comprises 17 items on a single page, uses a five-point response scale with a neutral option, allows simple total scoring from 17 to 85, is generic rather than disease-specific, and was written for lay respondents [26,27]. These features support its use in surveillance and evaluation settings and facilitate administration alongside sociodemographic and lifestyle measures.

4.2. Application of the QAPAF in the Portuguese Population

Study 2 applied the QAPAF to a broader sample to explore perceptions of functional foods and their association with sociodemographic and lifestyle variables. The results revealed a generally favourable perception of functional foods. Most participants agreed that such products should be consumed as part of a balanced diet and rejected the idea that they are only useful for specific groups such as older adults or individuals with chronic conditions [48]. However, the data also revealed persistent uncertainty, particularly in relation to safety, efficacy, and marketing claims. Neutral responses to statements about the ability of functional foods to reverse dietary damage or the reliability of advertised benefits suggest a degree of public scepticism. These perceptions mirror those found in other European studies, where concerns about product processing, artificiality, and the credibility of health claims are common [7,12,16,25]. Such scepticism may act as a barrier to the adoption of functional foods and should be addressed through transparent labelling and clearer communication [49]. Participants with correct knowledge about what constitutes a functional food were more likely to express trust in professional recommendations and to reject misconceptions. This highlights the importance of food literacy, not only as a knowledge domain but also as a determinant of confidence, trust, and intention to consume [22,24]. Educational interventions that improve understanding of functional food definitions and health benefits may therefore contribute to more informed dietary choices [13,32]. The study also found that individuals with higher levels of education, as well as those who abstain from smoking or alcohol, had significantly higher QAPAF scores. These associations suggest that the acceptance of functional foods is related to broader health-oriented behaviours and to individual motivation for health maintenance [19,28]. No differences were found according to sex, income, or BMI, indicating that attitudes may depend more on behavioural and cognitive factors than on demographic traits [20]. These findings have important implications for public health and nutrition policy. As functional foods continue to expand in the European market, there is a growing need to ensure that consumers can critically interpret health claims, understand product functionality, and make choices that align with evidence-based dietary guidelines [15,38,50]. Drawing on our prior findings (Oliveira et al. [51]), the QAPAF may help identify subgroups with low confidence or limited understanding and guide tailored health communication and educational programmes, pending confirmation in more diverse samples.

In addition, the tool could support the integration of functional foods into culturally appropriate dietary models, such as the Mediterranean diet. By identifying barriers and facilitators to acceptance, researchers and policymakers can better design interventions that promote both individual and public health outcomes [14,29,52]. Further validation of the QAPAF in other cultural and linguistic contexts is recommended. Longitudinal studies and applications in intervention settings will help establish the tool’s predictive validity and responsiveness to change. Exploring its association with actual dietary intake and health outcomes would also expand its utility for guiding population-based nutrition strategies [53].

4.3. Implications for Nutrition and Public Health

The QAPAF provides a practical and validated tool for assessing public perceptions of functional foods in adult populations. Its application in this study revealed that conceptual understanding and health-oriented behaviours are key predictors of positive attitudes toward functional foods [2,8,18]. These insights may support the development of more effective nutrition education strategies, especially in populations with lower health literacy [21,54]. By identifying groups with limited trust or misperceptions, public health professionals can design targeted interventions that clarify the role of functional foods within a healthy diet [11,55]. The instrument may also be useful in clinical nutrition settings to explore patient attitudes and inform personalised counselling [56]. From a policy perspective, the findings highlight the importance of transparent communication and regulation of health claims on food products. Ensuring that functional foods are not misunderstood or overestimated in their benefits is essential for promoting realistic and evidence-based dietary choices [31]. Furthermore, the QAPAF can be integrated into monitoring and evaluation frameworks to track changes in public perception over time, particularly in response to national campaigns, product reformulations, or regulatory changes. Its utility in future intervention research may also help assess the impact of food literacy programmes on consumer attitudes and behaviours [57].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

One of the main strengths of this study lies in the robust psychometric re-evaluation of a culturally adapted instrument designed to assess consumer perceptions of functional foods. The QAPAF was tested in a real-world setting with a relatively large and diverse adult sample, enhancing its applicability in population-level research and nutritional surveillance. The multidimensional structure of the instrument allows for a more comprehensive understanding of attitudes and beliefs, extending beyond knowledge to include trust, perceived necessity, and safety concerns [27]. Another strength is the inclusion of relevant behavioural and lifestyle variables, such as smoking status, alcohol consumption, and adherence to healthier dietary behaviours. These factors are often underrepresented in studies of consumer perception but proved to be significantly associated with QAPAF scores, offering insight into how functional food acceptance fits within broader health-related patterns [30].

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Generalisability is limited by the convenience sampling and by the predominance of female and highly educated participants; external validation in more diverse and preferably probability-based samples is warranted. The sample was recruited through convenience methods and was not representative of the general Portuguese population. Participants were predominantly female and highly educated, which may have influenced the overall attitudes and reduced the variability in perceptions [58]. Additionally, data collection relied on self-reported measures, including height, weight, and health status. This may introduce reporting bias or inaccuracies in BMI estimation [41]. The online format of the survey may have excluded individuals with limited digital access or literacy, potentially affecting sample diversity. Lastly, test–retest reliability was assessed in a relatively small subsample (n = 25), which constrains the precision and generalisability of the stability estimates. In this subsample, agreement across time points was perfect (Spearman ρ = 1.00; two-way mixed ICC, absolute agreement, single measures = 1.00), and all paired differences were zero (Wilcoxon Z = 0, p = 1.000; Bland–Altman bias = 0.00 with 95% limits of agreement 0.00 to 0.00). While this supports temporal stability over the two-week interval, the absence of between-time variation precluded estimating uncertainty for ρ and ICC. Confirmation in larger and more diverse retest cohorts is warranted [59]. Nonetheless, the chosen sample size is consistent with that used in preliminary psychometric studies of similar instruments [40,60]. Future work should also examine measurement invariance and predictive validity across key sociodemographic strata to strengthen external validity.

5. Conclusions

The QAPAF proved to be a valid and reliable instrument for assessing perceptions of functional foods in the Portuguese adult population. Its four-factor structure reflects key dimensions of consumer beliefs and attitudes, including confidence in health professionals, safety concerns, misconceptions, and general trust. The application of the QAPAF revealed significant associations with education level and health-related behaviours, suggesting its potential utility in identifying target groups for nutrition education. As functional foods continue to gain prominence in public health strategies, the QAPAF may serve as a valuable tool to inform and tailor food literacy interventions, supporting more informed and health-conscious food choices. Further research is warranted to confirm its applicability across different cultural and demographic contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17182938/s1, Table S1. Items of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods and Likert-scale response options; Table S2. Communalities of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods items based on principal component analysis (n = 343); Table S3. Item-total statistics and Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted for the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Perception of Functional Foods (n = 343); Table S4: Oblique four-component solution for the QAPAF (n = 343, listwise complete): pattern matrix, structure matrix, and factor correlation matrix. Extraction by principal components. Rotation by direct oblimin (delta = 0) with Kaiser normalization; Figure S1. The scree plot displays the eigenvalues associated with each principal component. The elbow observed after the fourth component supports the retention of four factors; Figure S2: Scree plot for the QAPAF item set (n = 343). Extraction: principal components. The elbow at the fourth component, together with eigenvalues greater than 1, supports retaining four components; Figure S3: Bland–Altman plot for the QAPAF total score (n = 25). The mean difference (bias) was 0.00 and the 95% limits of agreement were 0.00 to 0.00, because all paired differences were zero. Points lie on the horizontal line at 0, indicating perfect point-by-point agreement between test and retest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.O.; methodology, L.O.; validation, A.R.; formal analysis, L.O.; investigation, A.O.A., H.A.A., N.A.A., S.N.A., N.A., I.A. and A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.O.; writing—review and editing, A.O.A., H.A.A., N.A.A., S.N.A., N.A., I.A. and A.R.; visualisation, A.R.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, A.R.; funding acquisition, A.O.A., H.A.A., N.A.A., S.N.A., N.A., I.A. and A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidade Lusófona (reference: P04-24, 30 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The author N.A.A. would like to thank the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project (number PNURSP2025R130), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Granato, D.; Barba, F.J.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Cruz, A.G.; Putnik, P. Functional Foods: Product Development, Technological Trends, Efficacy Testing, and Safety. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefegha, S.A. Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals as Dietary Intervention in Chronic Diseases; Novel Perspectives for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. J. Diet. Suppl. 2018, 15, 977–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekete, M.; Lehoczki, A.; Kryczyk-Poprawa, A.; Zábó, V.; Varga, J.T.; Bálint, M.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Csípő, T.; Rząsa-Duran, E.; Varga, P. Functional Foods in Modern Nutrition Science: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Public Health Implications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyon, M.; Labrecque, J. Functional foods: A conceptual definition. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 1133–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanoglu, E.; Feng, S.; Janaswamy, S. Editorial: Functional foods: Adding value to food. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1466003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, O.P.; Ottaway, P.B.; Jennings, S.; Coppens, P.; Gulati, N. Chapter 20—Botanical nutraceuticals (food supplements and fortified and functional foods) and novel foods in the EU, with a main focus on legislative controls on safety aspects. In Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in the United States and around the World, 3rd ed.; Bagchi, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 277–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, S.; Herzig, C.; Birringer, M. A Balancing Act—20 Years of Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation in Europe: A Historical Perspective and Reflection. Foods 2025, 14, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urala, N.; Lähteenmäki, L. Attitudes behind consumers’ willingness to use functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Y.; Verbeke, W. Consumer evaluation, use and health relevance of health claims in the European Union. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 74, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrand, B.T.; Olsen, S.O. Relationships between functional food consumption and individual traits and values: A segmentation approach. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 86, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiel, J. Functional foods from the perspective of the consumer: How to make it a success? Int. Dairy J. 2010, 20, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Bai, L.; Zhang, X.; Gong, S. Re-understanding the antecedents of functional foods purchase: Mediating effect of purchase attitude and moderating effect of food neophobia. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; Sinesio, F.; Moneta, E.; Dinnella, C.; Laureati, M.; Torri, L.; Peparaio, M.; Saggia Civitelli, E.; Endrizzi, I.; Gasperi, F.; et al. Measuring consumers attitudes towards health and taste and their association with food-related life-styles and preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, E.; Deligiannidou, G.-E.; Kontogiorgis, C.; Giaginis, C.; Koutelidakis, A.E. Natural Functional Foods as a Part of the Mediterranean Lifestyle and Their Association with Psychological Resilience and Other Health-Related Parameters. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwatani, S.; Yamamoto, N. Functional food products in Japan: A review. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2019, 8, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalor, F.; Madden, C.; McKenzie, K.; Wall, P.G. Health claims on foodstuffs: A focus group study of consumer attitudes. J. Funct. Foods 2011, 3, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, T.; Nebbia, S.; Pascucci, S. The “Young” Consumer Perception of Functional Foods in Italy. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2012, 18, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.-T. Attitudes and Repurchase Intention of Consumers Towards Functional Foods in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Int. J. Anal. Appl. 2020, 18, 212–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barauskaite, D.; Gineikiene, J.; Fennis, B.M.; Auruskeviciene, V.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kondo, N. Eating healthy to impress: How conspicuous consumption, perceived self-control motivation, and descriptive normative influence determine functional food choices. Appetite 2018, 131, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topolska, K.; Florkiewicz, A.; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, A. Functional Food—Consumer Motivations and Expectations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Moreno Pires, S.; Iha, K.; Alves, A.A.; Lin, D.; Mancini, M.S.; Teles, F. Sustainable food transition in Portugal: Assessing the Footprint of dietary choices and gaps in national and local food policies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancone, S.; Corrado, S.; Tosti, B.; Spica, G.; Di Siena, F.; Misiti, F.; Diotaiuti, P. Enhancing nutritional knowledge and self-regulation among adolescents: Efficacy of a multifaceted food literacy intervention. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1405414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Araújo, R.; Lopes, F.; Ray, S. Nutrition and Food Literacy: Framing the Challenges to Health Communication. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Investigating the Effect of Consumers’ Knowledge on Their Acceptance of Functional Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, L.; Ribeiro, S.; Pereira, J.; Antunes, A.; Bezerra, R.; da Cunha, D. Consumer Perceptions of Functional Foods: A Scoping Review Focusing on Non-Processed Foods. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Poínhos, R.; Saousa, F.; Silveira, M.G. Construção e Validação de um Questionário para Avaliação da Perceção sobre Alimentos Funcionais. Acta Port. Nutr. 2016, 7, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Poínhos, R.; Sousa, F. Attitudes Towards Functional Foods Scale: Psychometric Proprieties and Adaptation for Use Among Adolescents. Acta Med. Port. 2019, 32, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moutinho, P.; Macedo, A.; Andrade, I. Functional food consumption by Portuguese university community: Knowledge, barriers and motivators. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2022, 24, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Saraiva, A.; Lima, M.J.; Teixeira-Lemos, E.; Alhaji, J.H.; Carrascosa, C.; Raposo, A. Mediterranean Food Pattern Adherence in a Female-Dominated Sample of Health and Social Sciences University Students: Analysis from a Perspective of Sustainability. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.A.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Oliveira, M.; Beatriz, P.P.; Alves, R.C.; Costa, H.S. Perceção e hábitos de consumo relativamente a alimentos funcionais. Bol. Epidemiológico Obs. 2020, 9, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Graça, P.; Gregório, M.J.; da Freitas, M.G. A Decade of Food and Nutrition Policy in Portugal (2010–2020). Port. J. Public Health 2020, 38, 94–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoni, M.F.; Oliveira, L. Perception of Functional Foods After a Brief Educational Intervention: A Pilot Study in Portuguese Adults. Biomed. Biopharm. Res. 2025, 22, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Consumer acceptance of functional foods: Socio-demographic, cognitive and attitudinal determinants. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Stampfli, N.; Kastenholz, H. Consumers’ willingness to buy functional foods. The influence of carrier, benefit and trust. Appetite 2008, 51, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.R.A.; Campos, R.F.d.A.; Rocha, F.; Emmendoerfer, M.L.; Vidigal, M.C.T.R.; da Rocha, S.J.S.S.; Lucia, S.M.D.; Cabral, L.F.M.; de Carvalho, A.F.; Perrone, Í.T. Perceived healthiness of foods: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diplock, A.T.; Aggett, P.J.; Ashwell, M.; Bornet, F.; Fern, E.B.; Roberfroid, M.B. Scientific Concepts of Functional Foods in Europe Consensus Document. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, S1–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics, 8th ed.; Report Number: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.M.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.W.M.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, C.B.; Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile And Cut Off Points. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Urala, N.; Lähteenmäki, L. Consumers’ changing attitudes towards functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Giménez, A.; Deliza, R. Influence of three non-sensory factors on consumer choice of functional yogurts over regular ones. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siró, I.; Kápolna, E.; Kápolna, B.; Lugasi, A. Functional food. Product development, marketing and consumer acceptance—A review. Appetite 2008, 51, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Functional foods development in the European market: A consumer perspective. J. Funct. Foods 2011, 3, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelakis, C.; Zevgitis, P.; Galanopoulos, K.; Mattas, K. Consumer Trends and Attitudes to Functional Foods. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 32, 266–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killackey-Jones, B.; Lyle, R.; Evers, W.; Tappe, M. An Effective One-Hour Consumer-Education Program on Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior Toward Functional Foods. J. Ext. 2004, 42, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Safraid, G.; Portes, C.; Dantas, R.; Batista, Â. Perception of functional food consumption by adults: Is there any difference between generations? Braz. J. Food Technol. 2024, 27, e2023095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Scholderer, J. Functional foods in Europe: Consumer research, market experiences and regulatory aspects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, N.J. A rational definition for functional foods: A perspective. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 957516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, L.; Sousa, F.; Silveira, M.G.d. Promotion of Functional Foods in a School Context: Evaluation of Food Education Sessions Involving Cooking Skills. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2023, 23, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Tomaino, L.; Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Ngo de la Cruz, J.; Bach-Faig, A.; Donini, L.M.; Medina, F.X.; Belahsen, R.; et al. Updating the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid towards Sustainability: Focus on Environmental Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, J.; Adinolfi, F.; Capitanio, F. Analysis of Consumer Attitudes and Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Functional Foods. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrela, M.; Leitão, C.; Neto, V.; Martins, B.; Santos, J.; Branquinho, A.; Figueiras, A.; Roque, F.; Herdeiro, M.T. Educational interventions for the adoption of healthy lifestyles and improvement of health literacy: A systematic review. Public Health 2025, 245, 105788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD009825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgary, S.; Rastqar, A.; Keshvari, M. Functional Food and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Treatment: A Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.S. Perceção da Importância de Alimentos Funcionais Pela População; Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcão, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Rodrigues, S.; Lobato, L.; et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física, IAN-AF 2015-2016: Relatório de resultados; Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, M.; Sampaio, F.; Costa, J.; Freitas, P.; Matias Dias, C.; Gaio, V.; Conde, V.; Figueira, D.; Pinheiro, B.; Silva Miguel, L. Burden of Disease and Cost of Illness of Overweight and Obesity in Portugal. Obes. Facts 2025, 18, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Nakano, E.Y.; Almutairi, S.; Alzghaibi, H.; Lima, M.J.; Teixeira-Lemos, E.; Saraiva, A.; Raposo, A. From Validation to Assessment of e-Health Literacy: A Study among Higher Education Students in Portugal. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).