Abstract

Background/Objectives. The ketogenic diet has emerged as a potential treatment strategy for reducing inflammation. The purpose of this meta-analysis and systematic review is to look into how a ketogenic diet affects inflammatory biomarkers in persons who are overweight or obese. Methods. We conducted an extensive search of Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar to find pertinent studies reporting changes in inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and cytokines after a ketogenic diet. Results. Seven randomized controlled trials involving 218 overweight or obese individuals who followed a ketogenic or control diet over 8 weeks to 2 years were included in the review, and five of those were considered for the meta-analysis. The primary outcomes were CRP and IL-6 levels. The results reported significant decreases after treatment for CRP (mean of −0.62 mg/dL (95% CI: −0.84, −0,40), and a slight, but not statistically significant, reduction in IL-6 (mean of −1.31 pg/mL (95% CI: −2.86, 0.25). Conclusions. The ketogenic diet could contribute to modulating inflammation in obese and overweight subjects.

1. Introduction

Obesity is often accompanied by chronic low-grade inflammation, which is associated with metabolic diseases and organ tissue complications, such as insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes [1,2]. The complex interconnections between obesity and inflammation are mainly due to the intricate cross-talk between various pro- and anti-inflammatory pathways within expanding fat stores, particularly in visceral adipose tissue (VAT) [3]. Adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ that secretes various molecules called adipokines, able to modulate inflammatory responses, regulating the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by immune cells [4].

Although the precise causes of obesity-related inflammation are unclear and may differ across tissues, it is commonly known that abnormalities in adipokine synthesis by adipose tissue caused by excess visceral fat result in persistent low-grade inflammation [5]. The association between chronic inflammation and obesity-associated metabolic disturbances is now widely recognized, prompting numerous studies to investigate the specific biomarkers of oxidative stress and systemic inflammation in this context.

Visceral fat has a pivotal role in metabolic disturbances, and various adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted by visceral adipocytes may be involved in altered metabolism [6]. Inflammation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome in obese and overweight individuals, and adipose tissue dysregulation and increased monocyte/macrophage activity appear to be key drivers of this inflammatory process. In a recent study, Reddy et al. [7] identified elevated that C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are a prototypic biomarker of the inflammatory burden in metabolic syndrome.

Since it was found in 1921 that both starvation and high-fat diets cause ketosis, the ketogenic diet (KD) has been used to treat epilepsy. The ketogenic diet acquired popularity as a possible treatment for several illnesses towards the end of the 20th century [8]. Low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets have been linked to beneficial effects on inflammatory biomarkers in individual studies, but this association has never been systematically reviewed [8]. The ketogenic diet is a low-carbohydrate, high-fat, and adequate-protein diet [9]. To induce nutritional ketosis, which is defined as an elevation of ketones in the blood in the range of 0.5–3.0 mmol/L, the ketogenic diet reduces carbohydrate intake to below 50 g a day [10].

It has been demonstrated that ketones can control oxidative stress and inflammation [11]. In particular, β-hydroxybutyrate (βOHB) inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome and activates the GPR109A receptor to reduce inflammation in macrophages. The βOHB-mediated inhibition of this inflammasome reduces proinflammatory interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-18, and caspase-1 activation, independently of GPR109A [12].

The classic ketogenic diet is the most widely evaluated KD, although other forms of this diet, such as the medium-chain triglyceride diet, the modified Atkins diet, low glycemic index treatment, and the very low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD), present several advantages due to their better tolerability and easier administration [8].

When compared to low-calorie diets, ketogenic dietary therapy has been linked to a higher reduction in VAT and a stronger preservation of lean mass [13]. By lowering the factors that cause the release of proinflammatory cytokines, a decrease in VAT can result in less chronic inflammation. Following a VLCKD intervention, one study found that the levels of serum CRP decreased and anti-inflammatory cytokines increased [14].

CRP is generated from the liver in response to inflammation and has a positive correlation with visceral fat, which is commonly seen in obese people, and it is a risk factor for cardiovascular events and type 2 diabetes [15].

Given the foregoing, the purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the effects of a ketogenic diet on cytokine-based indicators of inflammation in overweight or obese people, as opposed to other dietary regimens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies were English-language randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in the previous 10 years that examined the effects of the ketogenic diet on inflammation in adults. The search targeted studies reporting on serum CRP, serum interleukin, TNF-α, albumin, insulin, glucose, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides. In order to calculate mean changes, the relative standard deviations from baseline, and/or the mean differences between intervention and control groups, the eligible studies had to supply enough data. Studies involving children, studies that were not randomized, and studies without a control group were not eligible for inclusion.

This review was conducted in four steps, guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [16]: (1) the formulation of the review question: “Can the ketogenic diet affect the inflammatory process?”; (2) the definition of participants: overweight/obese women and men aged 18 to 75 years; (3) the approach used to search for pertinent intervention studies that discussed how the ketogenic diet affected the inflammatory process; and (4) data analysis using a meta-analysis and systematic review.

2.2. Information Sources

A search of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for English-language articles published between January 2013 and July 2024 was performed.

2.3. Search Strategy

The following search terms were employed: ketogenic diet [MeSH Terms]) OR very low-calorie ketogenic diet [MeSH Terms]) OR ketosis [MeSH Terms]) OR protein diet [MeSH Terms]) OR low-carbohydrate [MeSH Terms]) OR low-carbohydrate diet [MeSH Terms]) OR carbohydrate-restricted [MeSH Terms]) OR nutritional ketosis [MeSH Terms]) OR high-fat [MeSH Terms]) AND inflammation [MeSH Terms]) OR cytokines [MeSH Terms]) OR inflammatory diseases [MeSH Terms]) OR C-reactive protein [MeSH Terms]) OR lipid profile [MeSH Terms]) OR visceral adipose tissue [MeSH Terms]) OR lipids [MeSH Terms]).

2.4. Study Selection

Studies retrieved by the search strategy were screened and selected for a full-text review, performed independently by two authors (C.G. and M.P.), based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the case of disagreement, a third author was involved in the decision process (A.M.).

2.5. Participants

The eligibility criteria for participants included an age of 18 years or older and being overweight or obese, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or greater, and treatment with a ketogenic or control diet. No restrictions were placed on gender, diseases, race, or geographic location.

2.6. Intervention

RCTs investigating the effects of the ketogenic diet on inflammatory biomarkers in overweight and obese individuals were included. The range of anthropometric and biochemical markers was wide and included serum levels of adiponectin, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, albumin, insulin, CRP, and glucose. Levels reported in different units were standardized for the meta-analysis.

2.7. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

The Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias in individual studies [17]. The creation of the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome data, existence of incomplete data, and selective reporting were among the factors evaluated to determine the quality of the study. In each case, the risk was classified as low, high, or unclear. Studies with a low risk of bias for at least three items were considered to be of high quality, those with a low risk of bias for at least two items were considered to be of fair quality, and those with a low risk of bias for one or no items were considered to be of poor quality. This was evaluated independently by two writers (M.P. and C.G.), and any discrepancies were settled by a third author (S.P.).

2.8. Data Extraction and Analysis

Two authors (S.P. and M.R.) independently extracted the data and recorded the following for each study: first author and publication year; study design; study setting; inclusion criteria; number, gender/sex, and age of trial participants; dietary intervention in the control and experimental group(s); duration of interventions; and primary outcomes observed in each group. A meta-analysis was conducted to provide a pooled estimate for aggregated data.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

To collect ambiguous or missing data, the study’s authors were contacted. Missing data for continuous outcome data were taken into account using the same techniques as in the original research (usually last observation carried forward or mixed model repeated measures). Using p values, missing SD values were calculated. The meta-analysis combined results using the pooled effect size, which was the standardized mean difference with 95% CI. Heterogeneity across the studies was assessed using the I2 statistic. A fixed-effects model for data pooling was used when this statistic was below 50%. An I2 of less than 50% in Higgins’ I2 statistic test and a non-significant result in Cochrane’s Q test for significance indicate acceptable heterogeneity among studies. A meta-analysis or subgroup analysis of datasets from five or more research was used to investigate publication bias. Procedures related to data pooling were carried out in Review Manager 5.4.

3. Results

The search strategy retrieved 324 studies. Of these, 282 were removed after initial screening and the removal of duplicates. Of the 42 remaining studies, 30 were eliminated as they were not RCTs. This left 12 studies for the full-text review. Five were eliminated due to methodological issues (they did not assess dietary intake during treatment). The meta-analysis and systematic review covered the remaining seven. Figure 1 depicts the flowchart of the study selection.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Most of the studies analyzed a classic ketogenic diet with a total daily energy intake divided as follows: 15% carbohydrates, 60% lipids, and 25% proteins. The ketogenic dietary intervention was mostly compared with a baseline diet consisting of 15% proteins, 50% carbohydrates, and 35% lipids or the usual diet followed by the participants.

Although the initial study design contemplated a wide range of biomarkers, TNF-α, IL-10, albumin, insulin, glucose, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides were not included in the meta-analysis as fewer than three studies analyzing each of these measures were yielded by the literature search.

The main features of the seven RCTs included in the systematic review are summarized in Table 1. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 75 years. The total number of participants was 218. In five of the studies, the participants in the intervention group followed a ketogenic diet, while those in the control group followed a whole-food diet (without ultra-processed foods) or their usual diet [18,19,20,21,22]. In two studies, the intervention was a VLCKD with or without docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplements [23,24]. Generally, the classic ketogenic diet was formulated with 90% lipids, 6% protein, and 4% carbohydrates, with a very high ketogenic ratio of 4:1. The VLCKD used had a total calorie intake of 600–800 kcal/d, a carbohydrate intake of 20–60 g/d, obtained from plant foods, 1.2–1.5 g/kg of protein per kilogram of ideal body weight from food sources with high biological value to preserve muscle mass, and 15–30 g of lipid intake obtained mainly from extra virgin olive oil and omega-3 series polyunsaturated fatty acids. In one study, a medium-carbohydrate, low-fat, calorie-restricted, carbohydrate-counting diet or a very low-carbohydrate, high-fat, non-calorie-restricted diet were administered to induce nutritional ketosis [21].

Table 1.

Studies included in the meta-analysis.

Overall, almost all of the studies considered in this review showed improvements in inflammatory status, specifically with reductions in CRP and IL-6 levels [22,23,24,25,26].

3.1. Meta-Analysis

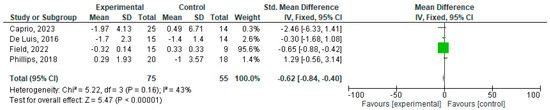

CRP and IL-6 levels were assessed through blood tests and reported as mg/L, mg/dL, or mmol/L (CRP) or pg/mL or ng/mL (IL-6). For the meta-analysis, the units were standardized to mg/dL and pg/mL, respectively. The effects of the ketogenic diet on CRP levels across four studies (references) are depicted in Figure 2, which shows a significant decrease after treatment (mean of −0.62 mg/dL (95% CI: −0.84, −0,40)).

Figure 2.

Effects of KD compared other type of diets on CRP [18,19,23,24].

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of the ketogenic diet on IL-6 levels over time. In this case, a not statistically significant decrease was detected, although the analyzed studies were only two (mean of −1.31 pg/mL (95% CI: −2.86, 0.25)).

Figure 3.

Effects of KD compared to other types of diet on IL6 [22,23].

3.2. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias for studies included in the meta-analysis, according to the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk of bias for studies included in the meta-analysis according to the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool a.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed evidence that the ketogenic diet could be used as a treatment for lowering inflammatory biomarkers in obese and overweight adults. We analyzed seven RCTs involving 288 participants who followed a ketogenic or control diet for 8 weeks to 2 years. The meta-analysis showed statistically significant changes in the CRP levels after treatment in mostly overweight or obese adults; a slight, but not statistically significant, reduction in IL-6 levels was observed. There were insufficient data to analyze other inflammatory markers, such as TNF-α and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

It has long been known that diet and fasting have a mitigating effect on inflammation, but the precise mechanisms by which this occurs remain largely elusive. The ketone bodies β-hydroxybutyric acid (BHB) and acetoacetate (AcAc) play a crucial role in mammalian survival during energy-deficit states, as they provide an alternative source of adenosine triphosphate. BHB levels are high during the ketogenic diet. BHB inhibits NLRP3, an inflammasome complex involved in driving inflammatory responses in many diseases, including several autoinflammatory conditions; it inhibits inflammatory activity by preventing the efflux of potassium ions, therefore decreasing IL-1 and IL-18 production [27]. Weight loss, a decrease in VAT, the modification of inflammatory markers, and the treatment of chronic pain with a resultant improvement in quality of life are some of the potential advantages of the ketogenic diet that have been documented [19]. The anti-inflammatory effects of the ketogenic diet are possibly mediated by several pathways. One recent study showed that this dietary therapy induced the cytochrome P450 4 A-dependent ω- and ω-1-hydroxylation of reactive lipid species, a novel mechanism that might contribute to the anti-inflammatory properties observed with ketogenic diet therapy [28]. The ketogenic diet also reduces the production of reactive oxygen species, thereby helping to improve mitochondrial respiration and bypass complex I dysfunction [29]. As suggested in a recent review of dietary therapy in obese individuals, there may be more specific mechanisms through which the ketogenic diet improves low-grade chronic inflammation and oxidative stress [30]. Ketosis specifically (1) inhibits NLRP3, a crucial signaling platform that triggers pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-18; (2) raises adenosine levels, which enhances HIF-α activation; (3) activates GPR109A, a receptor that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties; and (4) is linked to weight loss and calorie restriction, which alter the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes [30].

The findings of a recent study suggest that DHA supplementation may enhance the anti-inflammatory effects of the KD [23]. The authors compared a VLCKD with and without DHA supplementation. Large volumes of free fatty acids and bioactive lipid mediators, which are made from fatty acids and have potent pro- and anti-inflammatory effects, are released by adipose tissue during a VLCKD. Although the diet alone led to an improved red blood cell fatty acid profile (increased omega-3 index and decreased ratios of arachidonic acid [AA] to eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and AA to DHA), the anti-inflammatory fatty acid index (AIFAI) fell significantly during the ketogenic phase but reverted to near-baseline levels during the re-education phase. When the diet was combined with DHA supplementation, the AIFAI increased during both the ketogenic and re-education phases. DHA supplementation was also associated with greater variability in the omega-3 index and AA/EPA and AA/DHA ratios. Research has shown that DHA supplementation induces the time-dependent incorporation of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids into cell membrane phospholipids. This could affect inflammation as it would result in lower AA availability for eicosanoid synthesis [23]. Indeed, it is well known that taking DHA supplements raises the levels of intermediate anti-inflammatory metabolites, which in turn affects the release of proinflammatory substances by increasing resolvine and other active metabolites to address lipo-inflammation. As a result, even over an extended period of time, DHA administration is able to disrupt the re-entry circuit between obesity and lipo-inflammation, resulting in a decreased risk of weight gain and an increased sense of satiety [31,32,33].

Despite the limited number of studies analyzed, especially concerning IL(6), an overall significant decrease in CRP and IL(6) was found, indicating the promising modulating effect of the ketogenic diet, which could also be linked to a potential effect on the expression of genes related to enzymes involved in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory (ALOX5, COX1, COX2) and anti-inflammatory (ALOX15) eicosanoids. Based on the results of a study of gene expression in multiple sclerosis, Bock et al. [34] suggested that ketogenic diets might counteract pro-inflammatory mediators such as leukotrienes by increasing vascular permeability, promoting leukocyte migration, and improving leukocyte chemotaxis.

Adipose tissues are among the several organs that secrete the proinflammatory cytokines CRP and IL-6. These cytokines are more prevalent in obese individuals than in non-obese individuals, and there is a positive correlation between obesity and fat mass. Long-term exposure to elevated levels of CRP and IL-6 is associated with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome [35]. Subclinical, chronic inflammation is believed to originate in adipose tissue and may play a role in the development of metabolic syndrome. More precisely, the development of visceral adipose tissue is believed to be the primary source of the elevated inflammation associated with obesity. During this phase, macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue results in chronic oxidative stress and an inflammatory response due to altered immunological responses and endothelial dysfunction. These factors are underlying causes of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and other metabolic abnormalities [36]. Therefore, reducing the level of inflammation could reduce the risk of developing these disorders.

Regarding IL-6, the results of the present study are in line with those reported in an interesting very recent metanalysis that included randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of a KD on CRP, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 levels, showing that this KD has an effect on lowering TNF-a and IL-6 [37]. However, the results regarding CRP are not entirely similar; in fact, unlike the study conducted by Ji et al. [37], the results of the present meta-analysis showed a statistically significant reduction in CRP. The quantitative analysis regarding TNF-α was not conducted due to a lack of studies deemed adequate for the purpose, having restricted the search only to studies published in the last 10 years.

One of the key strengths of this meta-analysis lies in the design of the studies reviewed, as they were all RCTs, which enable causative inferences to be drawn. The examination of CRP and IL-6 levels before and after the various dietary interventions analyzed lends strength to the robustness of our findings. This systematic review and meta-analysis also has some limitations, including the small number of studies eligible for inclusion and the heterogeneous patient profiles. Most of the trial participants were overweight or obese, and some of them had comorbid conditions; moreover, it would have been interesting to consider other inflammatory indices, such as TNF-alpha, but the studies currently published on the subject did not fit the criteria we had defined for this meta-analysis.

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis showed the potential ability of the ketogenic diet to lower inflammatory biomarkers in overweight and obese individuals through different mechanisms. Such results need to be improved in order to involve a wider number of subjects and consider other inflammatory markers that could not be analyzed in this study. For this reason, these findings could be a starting point for future studies that investigate the long-term effectiveness and safety of this diet in achieving sustained reductions in inflammation levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and I.S.; methodology, S.P.; formal analysis, S.P.; data curation, M.P., C.G. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, C.G., A.M. and G.C.B.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, I.S.; project administration, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Ignacio Sajoux is employed by Pronokal Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in Obesity, Diabetes and related Disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondmkun, Y.T. Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Type 2 Diabetes: Associations and Therapeutic Implications. Diabetes. Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Laborde-Cárdenas, C.C.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. The Role of Adipokines in Health and Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, A.M.; Fouts, J.K.; Regan, D.P.; Booth, A.D.; Dow, S.W.; Foster, M.T. Adipose tissue extrinsic factor: Obesity-induced inflammation and the role of the visceral lymph node. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 190, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Choi, W.J.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.W. Relationship between inflammatory markers and visceral obesity in obese and overweight Korean adults: An observational study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.; Lent-Schochet, D.; Ramakrishnan, N.; McLaughlin, M.; Jialal, I. Metabolic syndrome is an inflammatory disorder: A conspiracy between adipose tissue and phagocytes. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 496, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, D.; Kasperek, K.; Rękawek, P.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. The Therapeutic Role of Ketogenic Diet in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, J.M. How does the ketogenic diet induce anti-seizure effects? Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 637, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, N.E.; Cross, J.H.; Sander, J.W.; Sisodiya, S.M. The ketogenic and related diets in adolescents and adults—A review. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossoff, E.H.; Dorward, J.L. The modified Atkins diet. Epilepsia 2008, 49 (Suppl. S8), 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.E.; Kim, H.D. Recent aspects of ketogenic diet in neurological disorders. Acta Epileptol. 2021, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, B.; Crujeiras, A.B.; Bellido, D.; Sajoux, I.; Casanueva, F.F. Obesity treatment by very low-calorie-ketogenic diet at two years: Reduction in visceral fat and on the burden of disease. Endocrine 2016, 54, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzano, A.; Polito, R.; Trimigno, V.; Di Palma, A.; Moscatelli, F.; Corso, G.; Sessa, F.; Salerno, M.; Montana, A.; Di Nunno, N.; et al. Effects of very low calorie ketogenic diet on the orexinergic system, visceral adipose tissue, and ROS production. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, P.A.; Attipoe, S.; Kazman, J.B.; Zeno, S.A.; Poth, M.; Deuster, P.A. Role of plasma adiponectin /C-reactive protein ratio in obesity and type 2 diabetes among African Americans. Afr. Health Sci. 2017, 17, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.C.L.; Murtagh, D.K.J.; Gilbertson, L.J.; Asztely, F.J.S.; Lynch, C.D.P. Low-fat versus ketogenic diet in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.; Pourkazemi, F.; Rooney, K. Effects of a Low-Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diet on Reported Pain, Blood Biomarkers and Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Pain: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.; Hall, K.D.; Guo, J.; Ravussin, E.; Mayer, L.S.; Reitman, M.L.; Smith, S.R.; Walsh, B.T.; Leibel, R.L. Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis and Inflammation in Humans Following an Isocaloric Ketogenic Diet. Obesity 2019, 27, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saslow, L.R.; Kim, S.; Daubenmier, J.J.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Phinney, S.D.; Goldman, V.; Murphy, E.J.; Cox, R.M.; Moran, P.; Hecht, F.M. A randomized pilot trial of a moderate carbohydrate diet compared to a very low carbohydrate diet in overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambadiari, V.; Katsimbri, P.; Kountouri, A.; Korakas, E.; Papathanasi, A.; Maratou, E.; Pavlidis, G.; Pliouta, L.; Ikonomidis, I.; Malisova, S.; et al. The Effect of a Ketogenic Diet versus Mediterranean Diet on Clinical and Biochemical Markers of Inflammation in Patients with Obesity and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luis, D.; Domingo, J.C.; Izaola, O.; Casanueva, F.F.; Bellido, D.; Sajoux, I. Effect of DHA supplementation in a very low-calorie ketogenic diet in the treatment of obesity: A randomized clinical trial. Endocrine 2016, 54, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio, M.; Moriconi, E.; Camajani, E.; Feraco, A.; Marzolla, V.; Vitiello, L.; Proietti, S.; Armani, A.; Gorini, S.; Mammi, C.; et al. Very-low-calorie ketogenic diet vs hypocaloric balanced diet in the prevention of high-frequency episodic migraine: The EMIKETO randomized, controlled trial. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keech, A.; Mitchell, P.; Summanen, P.; O’Day, J.; Davis, T.; Moffitt, M.; Taskinen, M.R.; Simes, R.; Tse, D.; Williamson, E.; et al. Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1687–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinman, R.D.; Pogozelski, W.K.; Astrup, A.; Bernstein, R.K.; Fine, E.J.; Westman, E.C.; Accurso, A.; Frassetto, L.; Gower, B.A.; McFarlane, S.I.; et al. Corrigendum to “Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base” [Nutrition 31 (2015) 1–13]. Nutrition 2019, 62, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, Y.H.; Nguyen, K.Y.; Grant, R.W.; Goldberg, E.L.; Bodogai, M.; Kim, D.; D’Agostino, D.; Planavsky, N.; Lupfer, C.; Kanneganti, T.D.; et al. The ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Berthiaume, J.M.; Li, Q.; Henry, F.; Huang, Z.; Sadhukhan, S.; Gao, P.; Tochtrop, G.P.; Puchowicz, M.A.; Zhang, G.F. Catabolism of (2E)-4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal via ω- and ω-1-Oxidation Stimulated by Ketogenic Diet. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 32327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, L.B.; Rae, C.D. β-Hydroxybutyrate in the Brain: One Molecule, Multiple Mechanisms. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Caprio, M.; Watanabe, M.; Cammarata, G.; Feraco, A.; Muscogiuri, G.; Verde, L.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Could very low-calorie ketogenic diets turn off low grade inflammation in obesity? Emerging evidence. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 8320–8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Perna, S.; Ilyas, Z.; Peroni, G.; Bazire, P.; Sajuox, I.; Maugeri, R.; Nichetti, M.; Gasparri, C. Effect of very low-calorie ketogenic diet in combination with omega-3 on inflammation, satiety hormones, body composition, and metabolic markers. A pilot study in class I obese subjects. Endocrine 2022, 75, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endres, S.; Ghorbani, R.; Kelley, V.E.; Georgilis, K.; Lonnemann, G.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; Cannon, J.G.; Rogers, T.S.; Klempner, M.S.; Weber, P.C.; et al. The Effect of Dietary Supplementation with n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on the Synthesis of Interleukin-1 and Tumor Necrosis Factor by Mononuclear Cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 320, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, C.A. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest 2000, 118, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, M.; Karber, M.; Kuhn, H. Ketogenic diets attenuate cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase gene expression in multiple sclerosis. eBioMedicine 2018, 36, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, A.M.B.; Oliveira, P.D.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Gonçalves, H.; Assunção, M.C.F.; Tovo-Rodrigues, L.; Ferreira, G.D.; Oliveira, I.O. Association between interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and adiponectin with adiposity: Findings from the 1993 pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort at 18 and 22 years. Cytokine 2018, 110, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Efremov, L.; Mikolajczyk, R. Differences in the levels of inflammatory markers between metabolically healthy obese and other obesity phenotypes in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Fotros, D.; Sohouli, M.H.; Velu, P.; Fatahi, S.; Liu, Y. The effect of a ketogenic diet on inflammation-related markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2024, nuad175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).