Abstract

There is evidence that hospital waste is indisputably high, and various strategies have been used to reduce the hospital’s rate of plate waste. This study aimed to map the currently implemented strategies in lowering the rate of plate waste in hospitals and categorize the different types of strategies used as interventions, as well as determine their impact based on specific parameters. The scoping review method included a search of three databases using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-SCR). The duplicate articles (n = 80) were removed. A total of 441 articles remained for the title and abstract screening. After 400 were excluded, 41 articles were reviewed for eligibility. Thirty-two full articles were eliminated due to a lack of focus on plate waste evaluation. Finally, nine accepted studies were grouped into five categories: menu modification, room service implementation, menu presentation, meal-serving system, and dietary monitoring tool. In conclusion, results showed that the majority of the studies implemented either of the five strategies to reduce plate waste; however, the cook-freeze system and staff training for both kitchen and ward staff were not yet part of any intervention strategy. The potential of this method should be explored in future interventions.

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), food waste is one of society’s most critical challenges [1]. A higher proportion of food waste that is generated impacts the environment, society, and economy [2]. A lesser-known fact is that the foodservice sector accounted for 14% of food waste in most affluent nations in 2010 [3], which translates to one meal wasted out of every six [4]. In the industrialized nation of the United States, about 188 kg of food waste per capita per year, with an estimated worth of $165.6 billion, is produced at the final consumption level [5]. In addition, research conducted by SWCorp in Malaysia reported that the entire quantity of food waste will be sufficient to fill sixteen Twin Towers of Malaysia by 2020 [6]. The costs of disposing of food waste include the price of purchasing raw food materials, food storage, food transportation, food preparation, labor costs, and food waste disposal costs [7].

Every foodservice organization strives to produce, deliver, and serve safe foods [8]. Hospital is one of the foodservice establishments that provide food to its patients [9]. In fact, in some healthcare facilities in New Zealand, food accounts for up to 50% of all waste. [10]. A recent review by Alshqaqeeq and colleagues [11] found that the rate of food waste in hospitals produced globally ranged from 6% to 65%. On the other hand, a previous Malaysian study indicated that depending on the food group and sex, public food waste ranged from 20% to 90% [12]. For instance, food waste tended to be highest for protein dishes such as chicken and fish and more prevalent among women for most food items [12]. Another study by Aminuddin and colleagues [13] involving government hospitals in East Malaysia reported that the average plate waste was 36% in 2017. Additionally, in a recent report, the average percentage of food waste for therapeutic diets served in 21 public hospitals was reported to be 47.4% in 2016 [14]. Recently, Razalli and colleagues [8] reported a high percentage of plate waste of 47.5% among hospitalized patients receiving a textured modified diet. The most wasted diet was found to be a blended diet (65%), followed by a minced diet (56%) and mixed porridge (35%) [8].

The amount of food waste that might be generated by the 6210 hospitals in the United States is alarming [15]. According to research by Alshqaqeeq and colleagues [16], a hospital serving 6640 patient meals per week can create more than 48,000 lbs. (24 tons) of food waste annually, including food lost during preparation and food that is prepared and not consumed or rejected by patients. In Indonesia, when documenting patients’ food intake, the majority of allied health professionals reported that plate waste was evaluated by using visual estimation from the entire tray using a Visual Comstock form, while those from smaller hospitals used a simple table in a logbook to record the proportion of food consumption [17].

Furthermore, a study conducted by Kontogianni and colleagues [18] found that about 58% of hospital patients could not consume all the foods provided to them. Based on these findings, a few factors related to food intake during hospitalization were identified, including patients’ clinical condition and food quality [18]. Physical attributes such as difficulty swallowing and food consumption are factors associated with the patient’s condition [18]. Thus, these factors have been strongly associated with increased food waste in hospitals [14]. Intestinal obstruction, dysphagia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, poor appetite, being too ill or lethargic to consume food, and poor dentition are additional nutrition-impact symptoms [19]. Inadequate nutrition intake while in the hospital strongly correlated with other variables, including mealtime interruptions, avoiding meals when a meal is missed, and refusing to consume requested food [19]. As a result, every hospital foodservice must have a robust management system in place to optimize the patient’s food and nutrition intake, increase patients’ satisfaction with the foodservice and produce better quality outcomes while lowering costs and revenue generation [8]. As yet, little is known of the most optimum strategies to reduce food waste among hospitalized patients.

Therefore, the present scoping review aimed to map the currently implemented strategies in lowering the rate of plate waste in hospitals and categorize the different types of strategies used as interventions, as well as determine the impact of the strategies on other parameters, in addition to plate waste. The feasibility of the strategies applicable to low-middle-income countries (LMIC), such as Malaysia, is also discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for the Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [20] and using Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework [21]. The methodology was strengthened by implementing the recommendations made by Levac et al. (2010) [22] and the Joanna Briggs Institute [23] methodology.

2.1. Stage 1: Identifying the Research Questions

This review aimed to answer the following questions:

- What current strategies have been implemented to reduce the rate of plate waste in hospitals?

- What are the categories of strategies to reduce the rate of plate waste in hospitals?

- What are the impacts of the strategies on other parameters in addition to plate waste?

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

2.2.1. Search Terms

The search terms in this review were developed based on the PCC mnemonic framework that refers to the Population, Context, and Concept (Table 1). The search terms were then developed (Table 2). The following terminology was used in this review, including plate waste and food waste. Plate waste in hospitals refers to the amount or proportion of the food served that remains uneaten by patients [24]. Conversely, food waste is a term that describes a condition that can occur anywhere and at any time in the world during the preparation, cooking, or consumption of food [11]. Boolean operators (OR, AND), including matching and abbreviated keywords, were used to combine related keywords and terms.

Table 1.

Keywords used for this review.

2.2.2. Databases

This search was conducted in May 2022 and was independently discussed and verified by two reviewers. Further discussions were made with second senior authors if a consensus was not reached. Searches on the following three databases, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and PubMed, and an additional search strategy using Google Scholar, were utilized to retrieve the potentially relevant studies.

2.3. Stage 3: Selection of Studies

The retrieved articles were then selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The articles were only included if they were full articles published in English from January 2011 to April 2022 that discussed strategies to reduce plate waste among patients in hospital wards. However, other articles were excluded if they were conference papers, abstracts, forums, posters, books, book series, titled books, blogs, magazines, theses, review articles, qualitative research articles, guidelines, pre-printed articles, and non-peer-reviews. Furthermore, studies that did not measure plate waste in the ward were excluded.

2.4. Stage 4: Data Extraction

The review team developed a chart data table to assist in data extraction. The data extracted from each study were author, year, country, category of strategy, study design, patient’s characteristics (sample size, age group, type of participants, gender), methodology (pre-intervention and strategy), outcome parameters, and findings.

2.5. Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

The extracted data were mapped and organized according to the review questions. Two independent reviewers charted data from each included study into a pre-designed data-charting template using Microsoft Excel software. Summarized data, including author, year, country, category of strategy, study design, patient characteristics, strategy, and pre-intervention, are provided in Table 2. Additionally, for the findings section, studies were grouped into a few parameters, such as (i) method to estimate plate waste, (ii) patient satisfaction, (iii) nutritional intake, (iv) meal quality, (v) food cost, (vi) portion size, and (vii) nutrition assistant role and satisfaction are provided in Table 3.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

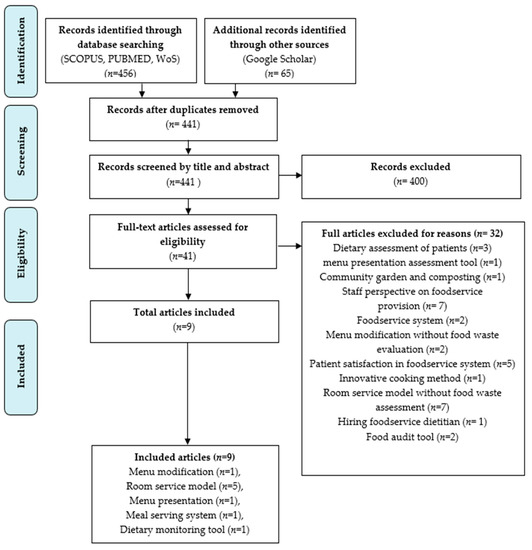

The study selection process was in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-SCR) [20], with full-text articles being thoroughly read to ensure that the articles met the inclusion criteria. A total of 521 articles were retrieved from the searched keywords and databases. The duplicate articles were removed (n = 80), and 441 articles remained for the title and abstract screening. After 400 articles were further excluded, 41 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility criteria.

Of these, thirty-two full articles were excluded for reasons such as the inclusion of dietary assessment of patients without measuring the plate waste assessment (n = 3), menu presentation assessment tool that did not focus on plate waste assessment (n = 1), linked hospitals’ foodservices to local community gardens to implement robust composting programs without focus on ward plate waste of the patients (n = 1), staff perspective on foodservice provision (n = 7), foodservice system that did not focus on plate waste assessment (n = 2), menu modification without plate waste assessment (n = 2), patient satisfaction on foodservice system (n = 5), an innovative cooking method that did not measure plate waste (n = 1), room service model without plate waste assessment (n = 7), the use of food audit tool that did not involve in hospital wards and examine patients’ nutritional status (n = 2), and hiring of foodservice dietitians without the focus on plate waste assessment (n = 1).

A total of nine articles were finally included in the review. Five categories of strategies were identified, such as (1) menu modification (n = 1), (2) room service model (n = 5), (3) menu presentation (n = 1), (4) meal-serving system (n = 1), and (5) dietary monitoring tool (n = 1). Based on the guidelines for conducting a scoping review, the researcher did not assess methodological quality or risk of bias in the accompanying articles [23]. Quality assessment is usually not required in scoping reviews [22,25], and this requirement is still debatable [26,27]. The PRISMA-SCR checklist is attached in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The original preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses for the scoping review process (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram [20].

3.2. Study Characteristics and Patient Characteristics

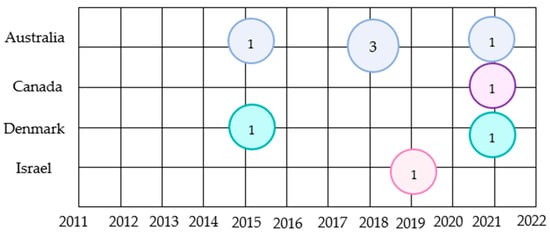

Out of the nine included studies, eight were conducted in western high-income countries, with the majority in Australia (n = 5), Canada (n = 1), Denmark (n = 2), and Israel (n = 1). Figure 2 illustrates the publication years and countries of the included articles. The study consisted of two observational point prevalence cohort studies, a quasi-experimental study, a randomized intervention study, a pilot study, a prospective cross-sectional study, two retrospective analysis studies, and a prospective observational cohort study (n = 1). Two of these selected studies specifically involved geriatric patients [28,29]. The sample size of most studies ranged from a total of 65 to 200 participants.

Figure 2.

Shows the original publication years and countries of included articles (n = 9). Different colors of circles represent the countries. The circles correspond to the number of articles published in the year and the country.

3.3. Types of Strategies to Reduce the Rate of Plate Waste in Hospitals

This review included five strategies implemented as interventions to reduce the rate of plate waste in hospitals. The strategies included menu modification, room service model, menu presentation, meal-serving system, and dietary monitoring tool. A summary of the interventions and pre-intervention is provided in Table 2. A total of five studies were found on room service model strategy to combat plate waste problems in hospitals, including two observational point prevalence cohort studies [30,31], two retrospective analyses [32,33], and one quasi-experimental study [34] that examined a comparison between a variety of room service models and the bought-in, thaw-retherm foodservice model and the traditional and cook-fresh paper menu system in hospitals. The investigated strategies included an à-la-carte-style menu with varied items and ordering times that suited the patients [32,33] and a 24 h available patient-directed bedside electronic meal ordering system using a touch screen and/or mouse and keyboard [30]. Furthermore, a bedside meal ordering system model was identified that allowed nutrition assistants to discuss suitable meal choices according to patients’ preferences and enter orders in a handheld wireless mobile device (Apple iPad) with a 7-day cycle menu of freshly cooked contemporary menu items [31]. Furthermore, Dining on Call (DOC), also known as room-service-style dining, enables patients to conveniently order meals anytime from a single integrated menu and can be delivered within 45 min [34].

Recently, a study focusing on menu modification strategy in Denmark [29] found that Free Choice Menu (FCM) allowed patients to order from a menu that included both hot and cold foods 24 h a day and improved cooking methods. Another study that highlighted a meal presentation intervention strategy used an orange napkin to improve food presentation and dietary intake and reduce readmission rates of hospital patients [35]. Furthermore, the Dietary Intake Monitoring System (DIMS) strategy is an innovative tool to monitor plate waste for portion size of meals and reduce food waste. The technology captures photographs while simultaneously collecting data on the dish’s weight, food temperature, date, and time [28]. Finally, in another study on the meal-serving system, the oral intake of adults in an acute care institution was improved by using smooth, pureed foods that were thickened and molded into a three-dimensional form [36].

Table 2.

Summary of strategies implemented as pre-interventions and interventions to reduce the rate of plate waste in hospitals and the characteristics of patients.

Table 2.

Summary of strategies implemented as pre-interventions and interventions to reduce the rate of plate waste in hospitals and the characteristics of patients.

| Author/Year/Country | Category of Strategy | Study Design | Patient’s Characteristics | Strategy | Pre-Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abou et al., 2021 (Canada) [34] | Room service model | Quasi-experimental study |

| Dining on Call (DOC) hospital foodservice

| Traditional foodservice

|

| Barrington et al., 2018 (Australia) [30] | Room service model | An observational point prevalence cohort study | For paper menu

| Patient-Directed Bedside Electronic Meal Ordering System (BMOS)

| Paper Menu (PM)

|

| Dynesen et al., 2021 (Denmark) [29] | Menu modification | A prospective cross-sectional study | Traditional trolley meal service

| Free Choice Menu (FCM).

| Traditional trolley meal service (trolley)

|

| Farrer et al., 2015 (Australia) [36] | Meal-serving system | A pilot study | Molded meals (treatment group)

| Molded smooth pureed meals

| Non-molded smooth pureed meals Served in the standard format |

| Navarro et al., 2019 (Israel) [35] | Meal presentation | A randomized intervention study | White napkin (control group)

| The addition of an orange napkin (experimental group) Cost approximately USD 0.05 for each napkin for the hospital meal tray | White napkin (control group) Received usual food trays with a white napkin |

| Neaves et al., 2021 (Australia) [32] | Room service model | A retrospective analysis | Thaw retherm service model

| On-demand room service model

| Bought-in, thaw-retherm foodservice model and cook-fresh

|

| McCray et al., 2018a (Australia) [33] | Roomservice model | A retrospective analysis | Traditional foodservice model

| Room service (RS)

| Traditional Model (TM)

|

| McCray et al., 2018b (Australia) [31] | Room service model | An observational point prevalence | Traditional paper menu ordering system (TM)

| Bedside meal ordering system (BMOS) model

| Traditional paper menu system (TM)

|

| Ofei et al., 2015 (Denmark) [28] | Dietary intake monitoring tool | A prospective observational cohort study | A trolley meal delivery system with dietary intake monitoring system (DIMS) technology

| Utilize a trolley meal delivery system with dietary intake monitoring system (DIMS) technology

| Trolley meal delivery system

|

Table 3.

The impact of the strategies on other parameters and plate waste.

Table 3.

The impact of the strategies on other parameters and plate waste.

| Author/Year/Country | Parameter | Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abou et al., 2021 (Canada) [34] |

| Tray waste | Patient Satisfaction | Food cost and labor cost per meal per day | ||

|

|

| ||||

| Barrington et al., 2018 (Australia) [30] |

| Plate waste | Dietary intake | Patient meal experience | ||

|

|

| ||||

| Dynesen et al., 2021 (Denmark) [29] |

| Plate waste | Nutritional intake | Portion Size | ||

|

|

| ||||

| Farrer et al., 2015 (Australia) [36] |

| Plate Waste | Patient Satisfaction | |||

| No statistical significance was seen in the hedonic rating of patient satisfaction with meals in the molded form as compared to the control group (p = 0.31) | |||||

| McCray et al., 2018a (Australia) [33] |

| Plate waste | Patient Satisfaction | Nutritional intake | Food cost | |

|

|

|

| |||

| McCray et al., 2018b (Australia) [31] |

| Plate waste | Patient Satisfaction | Nutritional intake | Nutrition assistant role and satisfaction | Food cost |

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Navarro et al., 2019 (Israel) [35] |

| Plate Waste | Patient Satisfaction | |||

|

| |||||

| Neaves et al., 2021 (Australia) [32] |

| Plate waste | Patient Satisfaction | Nutritional intake | Meal quality | Food cost |

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Ofei et al., 2015 (Denmark) [28] |

| Plate waste | Nutritional intake | |||

|

| |||||

3.4. The Impacts of the Strategies on Other Parameters and to Plate Waste

3.4.1. Method to Estimate Plate Waste

Plate waste in hospitals refers to the volume or percentage of food served to patients that have been discarded [24]. In the hospital context, there are two methods of measuring plate waste: the weighing method and the visual estimation method. Hence, this review of nine studies focused on plate waste measurement.

The weighing method is the most precise option, but it is time-consuming and resource-intensive to implement without disrupting or delaying typical foodservice operations [24]. A total of two studies were conducted using the weighing method [29,36]. In a study that implemented the food-serving-style strategy, the patients received either a non-molded (control group) or a molded smooth pureed lunch (treatment group). Overall, the control group generated 286 g of plate waste, while the treatment group generated 160 g [36].

Next, the Free Choice Menu (FCM) strategy for menu modification evaluated that plate waste using the weighing method was significantly lower (p = 0.0005) for lunch (15.6%) compared to the trolley concept (26.1%) [29].

Meanwhile, a visual estimation method is used to estimate the amount of food that remained. A variety of scales have been proposed. A seven-point scale (all, one mouthful eaten, ¾, ½, ¼, one mouthful remaining, none) [37] and the Comstock 6-point scale (all, one bite taken, ¾, ½, ¼, one mouthful left, none) [38] are the most comprehensive measurements, followed by the five-point scale (all, ¾, ½, ¼ or less, none, or virtually none) [39], a four-point scale (all, ½, ¼ or fewer, none or almost none) [40] and a three-point scale (all, below 50%, above 50%) [41].

A study conducted by Navarro et al. [35] used the Modified Comstock Plate Waste 6-point scale (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, or 100%) to determine the proportion of the menu item remaining on the plate. Patients in the group using the orange napkin (n = 66) consumed 17.6% more hospital-provided food than those in the white napkin (control) group (n = 65), (p = 0.002), driven by the significantly higher proportion of carbohydrate side dishes (p = 0.015) and vegetable dishes consumed (p = 0.022) [35]. The proportion of lunch consumed remained higher in the orange napkin group than in the control group (54.34 ± 4.08 versus 31.86 ±4.12; p = 0.004) [35].

Besides, the study conducted by Ofei et al. [28] revealed a significant relationship between the portion size of the meal and plate waste (p = 0.002). For the patients with nutritional risk, the food waste increased significantly during supper (p = 0.001) [28].

Furthermore, a total of five studies used the room service model [30,31,32,33,34], which allowed patients to make an ordered meal based on their preference at any time of the day with a variety of choices using the visual method five-point visual scale (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%) to evaluate plate waste. In four out of the five studies, the total average percentage of plate waste decreased from 40% to 5% and was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001) [31,32,33,34].

3.4.2. Patient Satisfaction

In previous studies conducted by [31,32,33], patient satisfaction was measured using the validated Acute Care Hospital Food Service Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire [42]. For the room service model, patient satisfaction increased from 75% to 89.8% (χ2 9.985 [2]; p = 0.007) [32], with 98% of the patients provided a score from good to very good, compared to 75% for the traditional model (p < 0.04) [33]. The overall foodservice satisfaction remained constant, with significantly more patients preferring bedside menu ordering systems (84%), while (16%) of patients preferred the traditional model (p = 0.00) [31].

A study by Navarro and colleagues [35] observed patient satisfaction levels using the Utah State University Hospital Food Service Patient Satisfaction Survey. Patients from the orange napkin group revealed significantly higher levels of satisfaction with the hospital dining service (p < 0.0001). They had higher foodservice satisfaction scores for serving patient’s preferred lunch, satisfactory food, appetizing presentation, preservation of served cold food, provision of main meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner), adequate time to consume the meal, and lunch looks tasty with (p < 0.0001) [35].

Regarding the perceptual ratings for pureed and molded lunches for individuals with and without impaired swallowing [36], no statistical significance was found in the hedonic rating of patients’ satisfaction with meals in the molded form compared to the control group (p = 0.31). A bedside satisfaction survey was verbally given to patients by a patient satisfaction surveyor and was used to compare patients’ satisfaction with pre- and post-Dining on Call (DOC). The management of hospital foodservice operations regularly uses this kind of survey [34]. At BC Children’s and Women’s hospitals, post-DOC results showed an increase of 1.9% and 7.9% in overall patient satisfaction for children and women, respectively [34]. According to patient satisfaction surveys in NYGH, overall patient satisfaction increased by 7% [34].

3.4.3. Nutritional Intake

Two studies investigated the effectiveness of nutritional intake by implementing a room service model using an à la carte menu [32,33] that was compared with a paper menu (cooked fresh, 14-day cycle menu), bought-in, thaw-retherm foodservice model and cooked fresh food, respectively. Both of the studies reported that the nutritional intake of patients had increased statistically significantly in room service for both energy intake (5513 kJ day−1 versus 6379 kJ day−1, p = 0.020) and protein intake (53 g day−1 versus 74 g day−1, p < 0.001) intake [33] with average energy and protein intake, percentage requirements, improved between thaw-retherm and room service (4320 kJ/day vs. 7265 kJ/day; 42.4 g/day vs. 82.5 g/day; and 46% vs. 80.7%; 49.9% vs. 98.4%; all p < 0.001), respectively [32].

The 7-day cycle menu [31], Free Choice Menu (FCM) [29], and Patient-Directed Bedside Electronic Meal Ordering System (BMOS) [30] were provided with a variety of meal choices according to the clinical conditions of the patients. The systems also enabled patients to make orders at any time according to personal preferences and were compared with traditional trolley meal service [29] orders at fixed hours as well as traditional paper-based menu systems [30,31], which have to make an order a day before. The study shows there was a significant increase in mean daily energy and protein intake (p = 0.035; p < 0.001 respectively) [31], average energy intake (6457 kJ day−1 versus 4805 kJ day−1, p < 0.001), and protein intake (73 g day−1 versus 58 g day−1, p < 0.001) [30].

Another study applied the trolley meal delivery system with and without the dietary intake monitoring system (DIMS) technology. For lunch, the energy intake (p = 0.150) and protein intake (p = 0.09) of patients were not statistically significant. In addition, the energy intake (p = 0.143) and protein intake (p = 0.698) for supper were not statistically significant [28].

3.4.4. Meal Quality

The meal quality scores were high for both the thaw-retherm and room-service models. There was a significant improvement in the appearance of meals (p = 0.031) [32].

3.4.5. Food Cost

A total of four studies on the room service model strategy reported a reduction in food costs ranging from 9% to 43.5% compared to the traditional meal service system [31,32,33,34].

3.4.6. Portion Size

A study conducted by Dynesen and colleagues [29] shows there was a significant positive relationship between portion size and meal consumption percentage for both concepts (trolley: p < 0.000; Free Choice Menu: p = 0.031).

3.4.7. Nutrition Assistant Role and Satisfaction

During the pre-implementation of the bedside meal ordering system (BMOS), approximately 36% of nutrition assistants preferred this strategy, and this increased significantly to 86% during post-implementation (p = 0.047) [31].

4. Discussion

The purpose of the scoping review is to map the current strategies implemented to reduce the rate of food waste in hospitals, categorize the strategies used, and determine the impact of the strategies on other parameters and plate waste. A total of five categories of strategies were identified, including menu modification, room service model, menu presentation, meal-serving system, and dietary monitoring tool.

The ideal strategy that can be adopted to reduce hospital plate waste is the room service model. However, we also acknowledge the challenges of implementing this strategy, particularly in hospitals in middle-to low-income countries, implying that enforcing a cook-freeze system and staff training are worthwhile strategies to combat food waste.

The room service model involves organizing structured mealtime and meal production schedules and mainly focuses on patients’ diagnosis and treatment schedules [33]. Additionally, ordering through the call center or bedside meal order personnel can promote better patient interactions and patient participation [33]. Furthermore, healthcare personnel should be responsible for supporting patients to make the best decisions when ordering the meal [31,43]. It is also likely that allowing ordering nearer to mealtimes can better accommodate patients’ current preferences, boost satisfaction, and permit food delivery within 45 min of ordering [31,32,33,34]. However, it will be more challenging to implement this strategy in low to middle-income countries such as Malaysia as most hospitals are high-volume and public- or government-funded. Thus, the cost will be a critical issue.

The cook-freeze method will be more effective in reducing plate waste in public or government-funded hospitals where the conventional foodservice system is common. Cook-freeze is similar to the cook-chill method, except that the prepared meals are frozen immediately rather than frozen in a blast freezer [44]. To increase menu flexibility, items can be frozen in bulk or as individual servings, especially for individuals who have specific nutritional requirements, such as gluten-free [44]. In a trolley, hot food may also be delivered to wards so that patients can make their selections there. The aroma and presentation of the food may help with patients’ hunger, whereas various serving sizes and food choices based on current appetite can be offered [44]. Additional nursing staff can be involved in notifying patients of the arrival of the trolley, further encouraging and socializing patients and more. However, disadvantaged patients may not have the mobility to access the trolley; thus, managing therapeutic diets can indeed be challenging because foodservice staff are untrained in this area, leading to more food waste (from the bulk trolley but not from individual patient meal plates) due to the number of options that must be included in the trolley to cover the menu [45]. In addition, we also identified that staff training had not been reported as a strategy to combat plate waste problems. It is a plausible strategy worth exploring since staff training has been linked with better service quality [46]. Understanding hospital foodservice management is one of the strategies to enhance hospital food provision [47]. A few studies focused on strategies such as the inclusion of room service [30,31,32,33,34], menu modifications [29], meal-serving style [36], menu presentation [35], and the dietary intake monitoring tool [28], but none of the studies intervened in staff training.

Consequently, two studies that were conducted in Malaysia [47,48] emphasized hospital personnel’s role in food provision and investigate staff attitudes and behaviors during patients’ mealtimes. The viewpoints and experiences of important stakeholders aided in the development of knowledge in several aspects of hospital meal production that affect patients’ decisions to accept and eat food.

There are a few strengths and limitations in this review. The review was conducted twice to filter duplicate articles during extraction and consider the study eligibility to meet specific criteria. Furthermore, this is the first review focused on documenting strategies to reduce plate waste in hospitals. This limitation of the study was the absence of a quality assessment, which is not a requirement for scoping reviews; therefore, it was not included in the methodology. In addition, very few publications focused on strategies to combat plate waste problems in hospitals, and the majority of studies were conducted in western high-income countries such as Australia, Canada, Denmark, and Israel. Therefore, more studies on strategies to reduce plate waste in hospitals in low to middle-income countries are needed to link with sustainable development goals related to food sustainability and the environment.

5. Conclusions

An appropriate solution proven to contribute to the objective of this study is to reduce food waste through plate waste, which has been reported to be the largest rate in a hospital setting [24]. It has been postulated that some food waste is inevitable in order to satisfy the dietary and nutritional needs of patients. [44]. The distribution of food to patients and the accompanying levels of waste are frequently prioritized in cost-cutting efforts. Food waste can be caused by a variety of variables, including food-service model design such as bulk cooking and reheating, extended lead time forecasting, and in-advance meal ordering, missed meals related to environmental factors, specifically hospital procedures and test schedules, as well as individual patient problems in the case of reduced appetite and other impacts of clinical symptoms and treatments, such as nausea or pain [44].

This review has identified five strategies that can potentially reduce the rate of plate waste in hospitals, such as menu modification, room service model, menu presentation, meal-serving system, and dietary monitoring tool. The room service model is the most suitable strategy to combat food waste issues in conventional foodservice systems. However, it would be challenging to implement and apply it in government-funded hospitals in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), such as Malaysia, as the cost will be the major challenge. In conclusion, the cook-freeze system and staff training are not yet part of any intervention strategy to combat the plate waste problem. Training healthcare staff could be explored in the near future and should include a discussion on the obligations and duties required in foodservice operations. It is recommended that the government regularly examine foodservice staff competency, budget food allocations, staff training, and replace equipment used in kitchens to improve the overall foodservice system and cost-effectiveness in reducing the rate of plate waste in hospitals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and N.H.R.; methodology, S.M., N.H.R., Z.A.M., S.S. and A.F.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M., N.H.R., Z.A.M., S.S. and A.F.M.L.; supervision, N.H.R.; project administration, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) FRGS/1/2018/SS08/UKM/02/5.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by the ethics committee of UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2022-346.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the academic librarians for their help and guidance in conducting this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- De Visser-Amundson, A. A Multi-Stakeholder Partnership to Fight Food Waste in the Hospitality Industry: A Contribution to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 12 and 17. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 30, 2448–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasavan, S.; Mohamed, A.F.; Halim, S.A. Drivers of food waste generation: Case study of island-based hotels in Langkawi, Malaysia. Waste Manag. 2019, 91, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environmental Agency. What Are the Sources of Food Waste in Europe? 2016. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/media/infographics/wasting-food−1/image/image_view_fullscreen (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Benson, I. WRAP Running Month of Restaurant Food Waste Action. 2019. Available online: https://resource.co/article/wrap-runningmonth-restaurant-food-waste-action (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Garcia-Garcia, G.; Woolley, E.; Rahimifard, S. A framework for a more efficient approach to food waste management. Int. J. Food Eng. 2015, 1, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.H. Waste not, Want not—It’s Time We Get Serious about Food Waste. New Straits Times. 2019. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/lifestyle/sunday-vibes/2019/09/525506/waste-not-want-not-%E2%80%93-its-time-we-get-serious-about-food-waste (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Kasavan, S.; Nurul Izzati, M.A.; Masarudin, N.A. Quantification of solid waste in school canteens—A case study from a Hulu Selangor Municipality, Selangor. Plan. Malays. 2020, 18, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razalli, N.H.; Cheah, C.F.; Mohammad, N.M.A.; Manaf, Z.A. Plate waste study among hospitalised patients receiving texture-modified diet. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemah, T.C.; Nur Adilah, Z.; Sabaianah, B.; Zurinawati, M.; Aslinda Mohd, S. Plate Waste in Public Hospitals Foodservice Management in Selangor, Malaysia. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goonan, S.; Mirosa, M.; Spence, H. Getting a taste for food waste: A mixed methods ethnographic study into hospital food waste before patient consumption conducted at three New Zealand foodservice facilities. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshqaqeeq, F.; Twomey, J.M.; Overcash, M.R. Food waste in hospitals. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2018, 17, 186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, S.; Chee, K.Y.; Chik, W.; Pa, W.C. Food intakes and preferences of hospitalised geriatric patients. BMC Geriatr. 2002, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminuddin, N.; Vijayakumaran, R.; Abdul Razak, S. Patient Satisfaction with Hospital Foodservice and its Impact on Plate Waste in Public Hospitals in East Malaysia. Hosp. Pract. Resear. 2018, 3, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norshariza, J.; Siti Farrah Zaidah, M.; Basmawati, B.; Leow, C.; Lina, I.; Norafidza, A.; Khalizah, J.; John Kong, J.P.; Lim, S.M. Evaluation of Factors Affecting Food Wastage among Hospitalized Patients on Therapeutic Diet at Ministry of Health (MOH) Hospitals. Asian J. Diet. 2019, 1, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- American Hospital Association. Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2019. Available online: https://www.aha.org/statistics/2020-01-07-archived-fast-facts-us-hospitals-2019 (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Alshqaqeeq, F.; Twomey, J.; Overcash, M.; Sadkhi, A. A study of food waste in St. Francis Hospital. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2017, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiningsari, D.; Shahar, S.; Abdul Manaf, Z.; Susetyowati, S. Needs assessment for patient’s food intake monitoring among Indonesian healthcare professionals. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontogianni, M.D.; Anna, K.; Bersimis, F.; Sulz, I.; Schindler, K.; Hiesmayr, M.; Chourdakis, M. Exploring factors influencing dietary intake during hospitalization: Results from analyzing Nutrition Day’s database (2006–2013). Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 38, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Allard, J.; Vesnaver, E.; Laporte, M.; Gramlich, L.; Bernier, P.; Davidson, B.; Duerksen, D.; Jeejeebhoy, K.; Payette, H. Barriers to food intake in acute care hospitals: A report of the Canadian Malnutrition Task Force. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Walton, K. Plate waste in hospitals and strategies for change. E-Spen. Eur. E J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 6, e235–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, H.M.; van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; McEwen, S.A. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.; Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Parker, D. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofei, K.T.; Holst, M.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Mikkelsen, B.E. Effect of meal portion size choice on plate waste generation among patients with different nutritional status. An investigation using Dietary Intake Monitoring System (DIMS). Appetite 2015, 91, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynesen, A.W.; Snitkjær, P.; Andreasen, L.S.; Elgaard, L.; Aaslyng, M.D. Eat what you want and when you want. Effect of a free choice menu on the energy and protein intake of geriatric medical patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 46, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington, V.; Maunder, K.; Kelaart, A. Engaging the patient: Improving dietary intake and meal experience through bedside terminal meal ordering for oncology patients. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCray, S.; Maunder, K.; Norris, R.; Moir, J.; MacKenzie-Shalders, K. Bedside Menu Ordering System increases energy and protein intake while decreasing plate waste and food costs in hospital patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2018, 26, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaves, B.; Bell, J.J.; McCray, S. Impact of room service on nutritional intake, plate and production waste, meal quality and patient satisfaction and meal costs: A single site pre-post evaluation. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 79, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCray, S.; Maunder, K.; Barsha, L.; Mackenzie-Shalders, K. Room service in a public hospital improves nutritional intake and increases patient satisfaction while decreasing food waste and cost. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 734–741, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou El Hassan, D.; Lewis, R.; Howe, N.; Vlietstra, E. Dining on Call: Outcomes of a hospital patient dining model. In Healthcare Management Forum; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 336–339. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, D.A.; Shapiro, Y.; Birk, R.; Boaz, M. Orange napkins increase food intake and satisfaction with hospital food service: A randomized intervention. Nutrition 2019, 67, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, O.; Olsen, C.; Mousley, K.; Teo, E. Does presentation of smooth pureed meals improve patients consumption in an acute care setting: A pilot study. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 73, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, A.J.; Nowson, C.A.; McPhee, J.; Alexander, J.L.; Wark, J.D.; Flicker, L. Nutrient intake at meals in residential care facilities for the aged: Validated visual estimation of plate waste. Aust J. Nutr. Diet. 1998, 55, 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock, E.M.; St Pierre, R.G.; Mackiernan, Y.D. Measuring individual plate waste in school lunches. Visual estimation and children’s ratings vs. actual weighing of plate waste. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1981, 79, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, K.; Shannon, B. Using visual plate waste measurement to assess school lunch food behaviour. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1983, 82, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hiesmayr, M.; Schindler, K.; Pernicka, E.; Schuh, C.; Schoeniger-Hekeler, A.; Bauer, P.; Laviano, A.; Lovell, A.; Mouhieddine, M.; Schuetz, T.; et al. Decreased food intake is a risk factor for mortality in hospitalised patients: The Nutrition Day survey 2006. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 28, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiah, J.; Stinnett, L.; Lutton, D. Visual plate waste in hospitalized patients: Length of stay and diet order. J. Am. Diet. Assoc 2006, 106, 1663–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, S.; Wright, O.; Sardie, M.; Bauer, J.; Askew, D. The acute hospital foodservice patient satisfaction questionnaire: The development of a valid and reliable tool to measure patient satisfaction with acute care hospital foodservices. Foodserv. Res. Int. 2005, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, K.; Collins, R.; Stone, T.; Carter, H.; Sadler, H.; Collinson, A. Are energy and protein requirements met in hospital? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Rosario, V.A.; Walton, K. Hospital Food Service. In Handbook of Eating and Drinking: Interdisciplinary Perspectives; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell, H.J.; Shepherd, P.A.; Edwards, J.S.A.; Johns, N. What do patients value in the hospital meal experience? Appetite 2016, 96, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sao Joao, E.A.; Spowart, J.; Taylor, A. Employee training contributes to service quality and therefore sustainability. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumaran, R.K.; Eves, A.; Margaret, L. Understanding Patients’ Meal Experiences through Staff’s Role: Study on Malaysian Public Hospitals. Hosp. Pract. Resear. 2018, 3, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumaran, R.K.; Eves, A.; Lumbers, M. Patients Emotions during Meal Experience: Understanding through Critical Incident Technique. Int. J. Hosp. Res 2016, 5, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).