Abstract

Nutritional ingredients, including various fibers, herbs, and botanicals, have been historically used for various ailments. Their enduring appeal is predicated on the desire both for more natural approaches to health and to mitigate potential side effects of more mainstream treatments. Their use in individuals experiencing upper gastrointestinal (GI) complaints is of particular interest in the scientific space as well as the consumer market but requires review to better understand their potential effectiveness. The aim of this paper is to review the published scientific literature on nutritional ingredients for the management of upper GI complaints. We selected nutritional ingredients on the basis of mentions within the published literature and familiarity with recurrent components of consumer products currently marketed. A predefined literature search was conducted in Embase, Medline, Derwent drug file, ToXfile, and PubMed databases with specific nutritional ingredients and search terms related to upper GI health along with a manual search for each ingredient. Of our literature search, 16 human clinical studies including nine ingredients met our inclusion criteria and were assessed in this review. Products of interest within these studies subsumed the categories of botanicals, including fiber and combinations, and non-botanical extracts. Although there are a few ingredients with robust scientific evidence, such as ginger and a combination of peppermint and caraway oil, there are others, such as melatonin and marine alginate, with moderate evidence, and still others with limited scientific substantiation, such as galactomannan, fenugreek, and zinc-l-carnosine. Importantly, the paucity of high-quality data for the majority of the ingredients analyzed herein suggests ample opportunity for further study. In particular, trials with appropriate controls examining dose–response using standardized extracts and testing for specific benefits would yield precise and effective data to aid those with upper GI symptoms and conditions.

Keywords:

fiber; botanicals; herbs; dyspepsia; upper gastrointestinal; GERD; heartburn; reflux; nausea 1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Upper GI Issues

American adults have been experiencing an increasing prevalence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, whether in an occasional or chronic manner [1]. A global survey indicates that 40% of adults worldwide suffer with one of many functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), with upper GI conditions representing a large component of those disorders [2]. A Cedars-Sinai study showed that two of every five Americans suffer from gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)-like symptoms every week, including heartburn and regurgitation [3,4].

Examples of structural upper GI conditions include erosive esophagitis, gastritis, and peptic ulcer disease, sometimes associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection [5,6]. Functional disorders involving the upper GI tract include GERD, esophageal hypersensitivity, esophageal dysmotility, and non-ulcer dyspepsia. FGIDs, now more commonly categorized as disorders of gut–brain interaction (DGBIs), are clinically defined per the Rome IV criteria [7]. Particularly common DGBIs of the upper GI tract include functional dyspepsia (FD), marked by symptoms of epigastric abdominal pain with or without early satiety, nausea or vomiting; and non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP). Disorders of the lower GI tract will not be included in this review.

Among these upper GI conditions, symptoms can include heartburn, reflux, indigestion, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, trouble swallowing, upper abdominal fullness, bloating, loss of appetite, and epigastric pain. While some individuals may experience occasional symptoms of upper GI distress, which may differ only slightly from normal perceived baselines, other individuals may notice a consistent pattern of these symptoms, which can then be mapped to a defined DGBI diagnosis [7].

Addressing upper GI conditions and symptoms is important due not only to their high healthcare utilization costs (annual expenditure of $135.9 billion in the United States), but also their impact on health-related quality of life (QoL), hindrance of ability to work, and necessity for prescriptions and/or over-the-counter (OTC) medications [2,3,8]. While current treatments for functional GI conditions and symptoms include H2 receptor antagonists (H2RA), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), antidepressants, and prokinetics, there is interest from consumers in more natural-based products, which is accompanied to some extent by published evidence in the scientific literature [3].

1.2. Background on Nutritional Ingredients and Use for Upper GI Support

Nutritional ingredients (a collective term used herein to describe botanicals, including dietary fibers, and non-botanicals) have been employed throughout history for a myriad of GI conditions and symptoms due to their claimed anti-ulcer, carminative, spasmolytic, soothing, and laxative effects, to name a few [9]. The usage of these products continues to increase, as evidenced by sales growth of 8.6% in 2019, the second largest percentage increase since 1998 [10,11].

To assess the state of the field and identify potentially fruitful avenues of future investigation, we chose to examine the clinical evidence for key ingredients’ effectiveness in treating upper GI conditions and symptoms. Table 1 provides a list of these 25 nutritional ingredients.

Table 1.

Ingredients of interest with alternative naming schemes.

1.3. Primary Aim of This Review

The primary aim of this review is to assess the robustness of clinical evidence and other data on the use of a select number of popular nutritional ingredients for upper GI conditions and symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was conducted following principles from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [12].

In developing the research question, the PICOS (population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design) criteria were used as well as consultation amongst authors to establish research design, study eligibility, and inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 2) [13]. The 25 ingredients were identified as being of interest based on currently marketed ingredients and information in the scientific literature.

Table 2.

PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies.

To better understand how these nutritional ingredients may impact upper GI health, a literature search with predefined search criteria was conducted in June 2021 using the Embase, Medline, Derwent drug file, Pubmed, and ToXfile databases. MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and keywords for nutritional ingredients as well as common upper GI complaints and symptoms were used in the search string (Table 3). The literature search was conducted with a time limit of 15 years (2006).

Table 3.

Search string for nutritional ingredients and upper GI conditions and symptoms.

For the initial search, the librarian screened for duplicates and then titles and abstracts to determine suitability for inclusion. They included all suitable titles and abstracts in a document that the primary author (RS) further screened for suitability. A second reviewer (RK) checked off on this process. Hand-searched articles were also checked off by a second reviewer. Full-text articles were screened independently by one review author and independently checked by a second reviewer.

The reviewers used a standard data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data. One review author (RS) extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies: Methods: study design, total duration of study, and number and location of study centers; Participants: number of participants, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, and diagnostic criteria; Interventions: intervention, comparison, duration of treatment, and follow-up time; Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion between RK and RS.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identified Trials

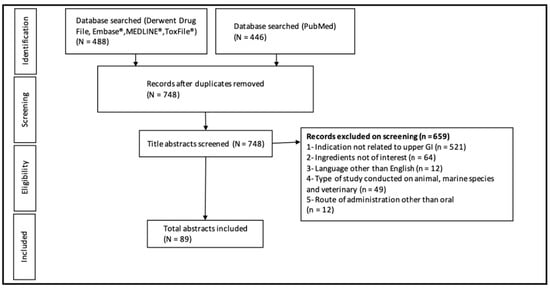

A total of 2282 articles were identified in the initial search strategy of 25 ingredients. After duplicates were removed, 1958 articles remained. The initial screening removed 1746 articles and the remaining abstracts that were included for further screening by the primary author totaled 212. This literature search process is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search process.

The primary author then further screened the full text of the 212 abstracts and titles and excluded 200 for the following reasons: the paper was not related to upper GI symptoms (39); it examined an irrelevant intervention (20); its language of publication was not English (5); it examined animals (1); it examined child/adolescent subjects (14); it was a secondary analysis (1); it was a duplicate (3), the full text was unavailable (3); it was a review (61); it was observational (2); or because it had been listed in a recent review (51). From this search, 12 articles were eligible and included in this review.

The manual search method yielded four more eligible articles which were included and assessed by the second reviewer. This process resulted in 16 articles covering nine ingredients that were eligible and included in this review. The additional 16 ingredients either lacked sufficient evidence to be mentioned, defined by possessing only animal or in vitro trials, or are reviewed in the discussion as ingredients meriting future investigation. The included ingredients fell into two main categories: botanical (including fiber, “other” botanicals, and combinations) and non-botanical.

3.2. Botanical Ingredients Addressing Heartburn, GERD, and Gastric Conditions: Fiber, Other Botanicals, and Combinations

3.2.1. Fiber

Fiber has been extensively studied for its impacts on lower GI health and recently more efforts have been invested in exploring fiber for its upper GI benefits, including two ingredients (fenugreek and galactomannan, reviewed herein and included in the table), and a third, marine alginate, which we mention only briefly due to its having recently been extensively reviewed (Table 4) [14,15].

Table 4.

Summary of human trials on botanical fiber ingredients and upper GI conditions.

Fenugreek and Galactomannan

Fenugreek is composed of a wide variety of bioactive compounds of which fiber, primarily the water-soluble fiber galactomannan, is suggested to be the effective component in observed reductions of heartburn and GERD symptoms [16]. DiSilvestro found that the fenugreek fiber group (2000 mg, twice per day, standardized to contain 85% galactomannan), and the ranitidine group (75 mg, twice per day) both yielded reduced heartburn severity and incidence in subjects (n = 45) over two weeks, and that fenugreek was significantly more effective than a placebo (Table 4) [14]. However, it is challenging to draw conclusions as to the efficacy of fenugreek based on this trial, as this was a partially blinded study and the primary outcome was measured subjectively based on participant diary entries of heartburn without pH measures, placebo, or other objective measures.

Abenavoli et al. conducted a double-blind RCT in which a formula (10 mL, three times per day) containing fenugreek-derived galactomannan significantly reduced symptoms in GERD patients (n = 60) as compared to a placebo (Table 4) [15]. However, as the formula also contained calcium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate, both known to reduce GERD symptomology, as well as Malva sylvestris and hyaluronic acid, indicated for mucosal healing due to their anti-inflammatory properties, it is challenging to elucidate whether and to what degree galactomannan itself is responsible for the observed effect [17,18,19,20]. Additionally, as galactomannan contains different ratios of mannose to galactose, depending on its source, further investigation is needed to determine a standardized composition [14].

The proposed mechanism for galactomannan’s effect on heartburn and GERD involves the soluble fiber forming a raft when hydrated, acting as a barrier to ameliorate the rise of acid into the esophagus, thus serving as an effective adjunct in the relief of GERD symptoms [15,21]. However, this mechanism is hypothesized based on similarities to observed MoAs for other naturally occurring polysaccharides such a marine alginate; research is needed to confirm this similarity [22]. An animal study by Pandian et al. attributed galactomannan’s superior antiulcerogenic ability to its observed reduction in gastric acid output but did not indicate a barrier mechanism [23]. Based on this evidence, fenugreek and its constituent, galactomannan, hold promise for the management of upper GI symptoms or conditions, but further investigations into a standardized extract composition and MoA are needed.

As galactomannan is a component of other gums such as guar gum, locust bean gum, and partially hydrolyzed guar gum, these could be investigated for similar effects on heartburn reduction [22,24]. In addition to galactomannan, soluble fiber as a whole is an evolving area of interest for upper GI symptom management. A prospective, open-label study (n = 30) observed an inverse relationship between increased fiber intake, specifically psyllium fiber (15 g per day), and occasional heartburn, esophageal sphincter resting pressure, and heartburn frequency in non-erosive GERD patients with previous low dietary fiber intake, defined as less than 20 g per day [25]. This trial lacked a placebo and was short in duration (10 days).

Marine Alginate

Marine alginate is an extract of seaweed, which, as described above, is suggested to mitigate GERD symptoms due to its raft-forming mucilage properties [21,22]. A recent SR by Zhao et al. assessed 10 RCTs, comparing various proprietary blends of marine alginate to a placebo or antacids, in combination with PPI versus PPI alone, or against PPI, in terms of their effectiveness in mitigating GERD symptoms [26]. Of these ten RCTs, seven were included in an MA. We found the authors’ use of the Cochrane Collaboration risk assessment to be satisfactory for rating the quality of evidence. Upon descriptive analysis of the related articles, they observed superior outcomes for alginate over a placebo or antacids, but pooled analysis revealed the differences in change in heartburn, regurgitation, and dyspepsia scores to be non-significant. Similarly, no significant difference was seen between changes in heartburn, regurgitation, and dyspepsia scores in a pooled analysis of those articles examining alginate in combination with PPI versus PPI alone. The articles examining alginate versus PPI were heterogenous and therefore not included in the MA, and descriptive analysis found no difference in outcomes between groups. However, although this SR grouped trials by intervention, the alginate formulations were heterogenous, and the duration of treatment varied considerably. Additionally, trials examining alginate versus a placebo or antacid should be assessed separately.

3.2.2. “Other” Botanicals

Nine studies explored four “other” botanical ingredients (defined as non-fiber ingredients for the purpose of this review) and their impact on upper GI conditions: Aloe vera (A. vera), ginger, licorice, and papaya [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. (Table 5). Here, we also review those “other” botanical ingredients with limited evidence (apple cider vinegar (ACV), cardamom, and fennel) or those subject to trials outside of the inclusion-date range (d-limonene) and thus not included in the tables.

Table 5.

Summary of human trials on “other” botanical ingredients and upper GI conditions.

Aloe Vera

A. vera is believed to help alleviate ulcerogenic and GERD related symptoms [36,37]. A 2015 open-label RCT by Panahi et al. found that A. vera syrup (10 mL once per day, standardized to 5.0 mg polysaccharide/mL syrup), when compared to ranitidine tablets (150 mg twice per day) and omeprazole capsules (20 mg once a day), was equally effective in reducing GERD symptoms in subjects (n = 70) (Table 5) [28]. A second randomized, open-label trial conducted in 2016 also by Panahi et al., found that A. vera syrup as an adjunct to pantoprazole therapy (5 mL twice per day and 40 mg once per day, respectively) was significantly more effective in reducing GERD symptoms compared to pantoprazole (40 mg once per day) alone in Iranian male veterans (n = 85) suffering from past sulfur-mustard gas exposure [27]. Although both utilized the same dosage of A. vera syrup, it is difficult to know whether both studies used a consistent composition and thus whether a dosage recommendation can be made. Furthermore, as the studies lacked placebos and were not blinded, it is difficult to make comprehensive conclusions as to A. vera’s effectiveness for GERD. Both the 2015 and 2016 studies shared adverse event (AE) data, with the earlier reporting two AEs in the A. vera group (vertigo and stomachache), neither of which resulted in dropout, and the latter reporting none.

Some point to A. vera’s antioxidant activity as its MoA related to GERD, as oxidative stress and inflammation may be involved in GERD pathogenesis [38]. In vitro and animal studies have observed reduced lipid peroxidation, hepatic and fatty markers, and necrosis upon A. vera administration [28,39,40].

Apple Cider Vinegar

Several studies indicate apple cider vinegar (ACV)’s usefulness in lowering postprandial glycemic response, specifically by slowing of gastric motility, which would seem paradoxical with respect to its potential value for upper GI symptoms [41,42,43]. However, these studies were small and yielded heterogenous outcomes. ACV was used in the gum formulation mentioned above, and while subjects found beneficial effects in relief of heartburn and acid reflux, it is challenging to elucidate whether this effect was due to the ACV or the other ingredients [44].

Cardamom

A review examining the effects of natural ingredients on PINV mentioned an RCT examining the effects of cardamom, but the trial was in Arabic and therefore unevaluable [45,46]. Two animal studies observed cardamom extract as an effective treatment for induced gastric ulcers in rats, with the proposed MoA including direct protection of the mucosal barrier as well as the extract’s ability to facilitate smooth muscle relaxation [47,48].

D-limonene

D-limonene, a terpene extracted from citrus essential oil (Rutaceae), has a number of animal and in vitro trials highlighting it as a gastroprotective and GERD ameliorating agent [49]. Additionally, two separate clinical studies performed under a U.S. patent found that adults suffering from chronic heartburn and GERD significantly benefited from d-limonene supplementation [50]. However, we did not include this in the tables as the date was outside of our inclusion criteria. Additionally, the first trial did not contain a placebo and did not account for three of the participants, and both utilized heterogenous dosing patterns and duration of treatment, as well as differently standardized extracts (1000 mg d-limonene of 98.5–99.3 vs 98% purity, respectively).

Fennel

Rodent studies have shown that anethole, a chemical derivative of fennel oil, increases gastric emptying in mice, suggesting that it could be used for FD [51]. A clinical trial examined the effects of a formulation comprised of fennel, lemon balm, and German chamomile on gastric transit time, but this trial was unevaluable as infants were the studied population and thus the study fell outside of our inclusion criteria [52]. As a result, further investigation is needed to elucidate the relationship between fennel and gastric emptying in adults, and its potential impact on related upper GI conditions.

Ginger

Ginger’s proposed MoA is its inhibition of intestinal cholinergic M3 and serotonergic 5-HT3 receptors, manifesting in decreased nausea and vomiting, as well as increased gastric motility and a corresponding decrease in transit time [29,53,54]. Gingerols are commonly indicated as the active ingredient responsible for targeting and modulating these signaling pathways [55].

Due to the recent publication of two systematic reviews (SRs) of ginger, our assessment only included those clinical trials that had been conducted since the publication of these SRs. We also analyzed the findings of these SRs [29,30,31] (Table 4).

In their SR, Nikkhah Bodagh et al. concluded that a daily dosage of 1500 mg of ginger is effective in relieving pregnancy induced nausea and vomiting (PINV), and that more investigation is needed before making a similar recommendation for other GI conditions due to the paucity of evidence [56]. Upon closer examination, however, this SR did not report any research methodology regarding how they conducted the SR; among other details, information indicating how they arrived at the dosage recommendation is lacking. Additionally, the included data set is heterogeneous, utilizing findings from RCTs, SRs, and meta-analyses (MAs), and considering the various etiologies of nausea simultaneously, integrating heterogenous outcomes and thus weakening the quality of its evidence.

Anh et al.’s SR reviewed 109 RCTs focused on clinical use of ginger, 47 of which were related to ginger’s antiemetic function and three to its gastric emptying function [57]. While we did not examine each included reference in depth due to the data-set size, we concluded that their system for rating quality of evidence was sufficient based on their use of the Cochrane Collaboration tool and granularity in research methodology reporting. Regarding their assessment of ginger’s gastric emptying ability, the three RCTs reported inconsistent effects [58,59,60]. Additionally, only one of these studies was rated by the authors as “high quality evidence” and upon closer examination, this study involved a crossover design. Regarding their assessment of articles analyzing various types of nausea, they concluded that a divided daily dosage of less than or equal to 1500 mg ginger could be recommended for PINV due to all 10 reported RCTs yielding consistent data, but that more trials are needed to ascertain results for chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) due to conflicting results.

Three trials examining ginger’s effectiveness were published since these SRs: Attari et al. and Panda et al. examined FD; Bhargava et al. examined upper GI symptoms in advanced cancer patients (Table 5) [29,30,31]. While Attari et al. and Panda et al. examined FD, these studies utilized inconsistent daily dosing (3 g versus 400 mg), extract composition, use of ginger powder versus OLNP-06 (standardized high gingerol concentration), and heterogenous subjective reporting questionnaires, making it difficult to integrate outcomes and ascertain an effective dose. Additionally, Attari et al.’s study examined H. pylori positive FD subjects; although H. pylori is also a necessary area for study due to its high global prevalence and potential role as a factor in the development of dyspepsia, it is challenging to elucidate the impact of ginger on FD alone based on this study, and is therefore difficult to integrate its outcomes [61,62]. Furthermore, this study did not include a placebo and had a small sample size (n = 15). Conversely, Panda et al. conducted a higher powered trial (n = 50) with proper blinding and a placebo. Panda et al. reported two mild AEs in the intervention group and Attari et al. did not provide AE information. Based on this, ginger shows promise in managing FD symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, and early fullness, but requires larger, appropriately designed clinical trials with standardized interventions to reach consensus on a consistent ginger extract composition and dosage.

Bhargava et al. found that ginger (1650 mg per day) significantly improved upper GI symptoms such as dysmotility-, reflux-, and ulcer-like symptoms, as well as nausea and anorexia in advanced cancer patients (n = 14) with anorexia-cachexia syndrome [31]. In addition, nine of the fifteen patients saw improvement in stomach gastric myoelectrical activity, indicated by an electrogastrogram (EGG), which could be related to motility. The authors noted their study limitations, such as the small sample size, short duration (14 days), and lack of a placebo. In sum, this study indicates the need for further trials to confirm ginger’s application for dyspepsia-like symptoms in advanced cancer patients. Whether these results can be generalized to non-cancer patients also needs further investigation.

Collectively, it appears that a divided daily dosage of 1500 mg of ginger may be effective in reducing PINV but that further trials are needed to reach a consensus on a dosage and standardized extract composition for other types of nausea besides FD [63].

Licorice

There is a paucity of trials examining the MoAs underlying licorice’s effectiveness for FD. Animal trials attribute its anti-ulcerogenic activity to observed free radical scavenging, as well as mucus production, and prostaglandin inhibition [32,64,65,66]. Licoflavone and glycyrrhizin are commonly indicated as the active ingredients responsible for the observed effects [67,68].

Two clinical studies were identified that investigated the effects of licorice on upper GI symptoms (Table 5) [32,33]. Prajapati and Patel reported that licorice root powder and licorice substitute (T. nummularia) (both dosed at 2 g, three times per day) were effective in significantly reducing indigestion symptoms in subjects (n = 40) such as eructation with a bitter or sour taste, nausea, and a burning sensation in the throat and chest [32]. In addition to lacking a placebo, this study did not state whether it was blinded, and seemed primarily interested in investigating the substitute’s effectiveness.

In a double-blind RCT, Raveendra et al. observed a significant improvement in dyspeptic symptoms and QoL in Rome III classified FD subjects (n = 50) receiving a standardized flavonoid-rich licorice extract (75 mg, twice per day) over 30 days as compared to placebo [33]. Although they utilized a validated questionnaire measuring QoL, their method for assessing improvements in FD symptoms was a subjective measure. No AEs were reported.

Papaya

Animal and in vitro studies suggest that papaya has an ability to scavenge ROS and inhibit gastric secretion through histamine reduction [69,70,71] and that it also acts directly upon gastric smooth muscle to impact its motility [72].

Muss et al. and Weiser et al. examined papaya extracts among subjects with a range of GI dysfunctions such as constipation, heartburn, and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and chronic gastritis (Table 5) [34,35]. Muss et al. found that a papaya proprietary blend (20 mL per day; standardized to higher papain activity) improved heartburn symptoms non-significantly (n = 13) [34]. Weiser et al. observed an improvement in upper GI complaints in patients (n = 60) supplemented with papaya formula (20 g, twice per day; formula containing papaya and oats) as compared to a placebo, but these differences were non-significant [35]. Muss et al. did not reveal AE data and Weiser at al. reported zero AEs. Although both studies examined papaya, they used widely different formulations and are thus difficult to compare.

3.2.3. Combination Products

Two studies explored the relationship between combinations of various botanical ingredients and their impact on upper GI conditions (Table 6) [44,73]. In addition, we also discuss the recent SR summarizing the effectiveness of peppermint oil and caraway oil (POCO).

Table 6.

Summary of human trials on botanical combination ingredients and upper GI conditions.

Ried et al. studied the effects of curcumin, A. vera, slippery elm, guar gum, pectin, peppermint oil, and glutamine in three amounts (5 g/day; 10 g/day; choice of 0–10 g/day) for three consecutive, four-week trial periods on adults (n = 43) experiencing one or more upper and/or lower GI symptom at least once per week for at least 3 months. The authors found a significant improvement in indigestion, heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, and QoL, as well as a decrease in GERD symptom frequency and incidence (Table 6) [73]. The authors reported two mild AEs related to the trial (severe bloating and constipation) which resulted in dropout. While the study utilized a 4-week run-in period to act as the control, the intervention period was a single-arm design and lacked a placebo. Slippery elm has received increased interest, but trials examining its singular effect are lacking, with Ahuja and Ahuja highlighting it as a promising ingredient due to its raft-forming potential and therefore its ability to ameliorate GERD symptoms, but stating that this requires further investigation [74].

Brown et al. conducted a crossover RCT trial in which participants (n = 24) consumed a specific high-fat, reflux inducing meal followed by 30 min of chewing one of the two treatment gums, either the placebo gum or the intervention gum, containing calcium carbonate (500 mg), ACV, licorice, and papain (Table 6) [44]. The intervention significantly reduced heartburn and mean acid reflux score (measured by a symptom based visual analogue scale (VAS)) in GERD patients (n = 24) as compared to the placebo. Given the combinatorial nature of the intervention, as well as calcium carbonate’s effects on GERD symptom reduction and the known heartburn-reducing effect of chewing gum alone, it is challenging to elucidate each individual ingredient’s role in the observed outcome [75].

Peppermint Oil and Caraway Oil

Peppermint oil (PO) has been a long-studied ingredient for its possible effects on upper GI conditions as well as the combined formulation of POCO. A recent paper reviewed peppermint’s effects on FGIDs, finding that PO was always used in combination with additional ingredients when used for FD, either as POCO or another formulation [76]. The three RCTs they included consisted of heterogenous combinations and outcomes, with two showing improvement in FD symptoms and the other showing no significant difference between the intervention and a placebo. Another recent SR-MA also examined POCO’s effectiveness in FD, including five RCTs (n = 578) which were of the same duration (4 weeks) examining heterogenous formulations [77]. The authors’ use of the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool was satisfactory. They found that POCO resulted in statistically significant global improvement in FD symptoms and improvement in epigastric pain. The common divided daily dosage was one capsule of 90 mg PO and 50 mg CO, twice daily. This SR-MA concluded by calling for higher quality studies investigating longer term effects of POCO on FD. In addition, there is a need for trials studying the effects of isolated PO on FD. The underlying MoA for POCO’s effects on FD is unclear, but may have to do with POCO’s observed ability to modulate post-inflammatory visceral hypersensitivity in rats [78] as well as its effect on decreasing frequency and amplitude of the migrating motor complex (MMC) in healthy volunteers [79].

3.3. Non-Botanical Ingredients Addressing Heartburn, GERD, and Gastric Conditions

Two studies investigated the impact of non-botanical nutritional ingredients: activated charcoal (AC) and zinc-l-carnosine (ZnC) on upper GI conditions (Table 7) [80,81]. In addition, we mention the recent work dedicated to melatonin.

Table 7.

Summary of human trials on non-botanical ingredients and upper GI conditions.

3.3.1. Activated Charcoal

Lecuyer et al. (n = 132) and Coffin et al. (n = 276) found that two formulations of AC and simethicone with or without magnesium oxide resulted in a significant reduction in FD symptoms in FD patients as compared to placebo (Table 7) [80,81]. Coffin et al. reported four patient dropouts in both groups because of mild AEs related to GI symptoms while Lecuyer et al. reported zero AEs.

Most studies on AC examine its relationship to lower GI gas. Furthermore, most of these trials were conducted in the 1990s, are relatively low powered, and yielded conflicting results, with some indicating that AC significantly reduced breath hydrogen levels and GI symptoms, and others not showing any effect [83,84,85,86]. These studies all indicated unclear mechanisms of action, though authors hypothesized that AC likely either adsorbed the gas or gas-causing agents or prevented gas formation. Although this benefit might seem relevant only to lower GI symptoms, Lecuyer et al. make the point that dyspeptic symptoms such as early satiety and bloating might also be related to the accumulation of air. Thus, one could hypothesize that AC could reduce the dyspeptic symptoms by mitigating abdominal air [80]. However, the formulations studied could also both be effective simply due to the use of simethicone [80,87,88]. As a result, more extensive research needs to be performed to assess the efficacy of AC alone.

3.3.2. Melatonin

While the use of melatonin as a sleep aid has been well established, research also indicates its potential role in GERD and FD [89,90]. While an SR has not yet been conducted, Bang et al. composed a protocol for an SR-MA assessing melatonin’s effectiveness in the context of GERD [91].

A trial studied patients (n = 36) with and without GERD, who received the following four interventions: a control; melatonin (3 mg, once per day at bedtime); omeprazole (20 mg, twice per day); and a combination of omeprazole and melatonin. They found that the two groups receiving melatonin supplements alone, or in addition to omeprazole, yielded a significant increase in LES pressure, while the groups receiving omeprazole alone or in addition to melatonin yielded a significant increase in pH and serum gastrin levels, and a significant decrease in basal acid output (BAO), compared to melatonin alone [90]. While they utilized diagnostic tools such as esophageal manometry, pH-metry, BAO monitoring, and serum measurements to assess outcomes, the authors did not share their methods for assessing improvements in heartburn and epigastric pain. An RCT by Klupinska et al. examined the role of melatonin (5 mg, once per day at bedtime) versus placebo in FD subjects (n = 60) and found that 56.6% of the melatonin group had complete resolution of dyspeptic symptoms and 30% experienced a partial resolution, while the majority of placebo subjects (93.3%) saw no improvement [89]. Additionally, those in the melatonin group used significantly less alkaline relief tablets than those receiving the placebo. The authors utilized a Likert scale to rate pain, sleep, and symptom intensity. MoA have been proposed for melatonin’s effectiveness in upper GI conditions, including animal trials that have demonstrated decreased secretion of HCl and pepsin [92], and also the stimulation of gastrin release, which could mitigate reflux by increasing the contractile activity of the LES [93].

3.3.3. Zinc-l-carnosine

ZnC, also known as polaprezinc, a chelate of zinc with L-carnosine, is a compound with numerous clinical trials conducted in the 1990s, and a long history of use in Japanese medicine as a gastric mucosal protective agent [82,94,95,96,97]. In an RCT, Tan et al. found that all three arms consisting of ZnC (either 75 mg or 150 mg, 2x per day), in combination with triple therapy (omeprazole (20 mg), amoxicillin (1 g), clarithromycin (500 mg), each twice daily) or triple therapy alone, were effective in significantly reducing symptoms in H. pylori positive gastritis patients, including abdominal pain, acid reflux, belching, heartburn, bloating, nausea, and vomiting (Table 7) [82]. As mentioned above, as H. pylori infection has a high global prevalence and can be an underlying risk factor for the development of dyspepsia symptoms, it is an important area to also investigate [61,62]. However, as there are no non-H. pylori gastritis studies examining ZnC, it is not clear what the results could be regarding ZnC’s effectiveness for heartburn or dyspepsia. Additionally, as this study did not include a placebo, it is difficult to elucidate ZnC’s superiority over prescriptions used for gastritis. While MoAs related to gastritis have not been elucidated, animal and in vitro studies have attributed ZnC’s observed anti-ulcerogenic activity to binding and healing of the ulcer site, as well as its ability to reduce levels of inflammatory cytokines, increase heat shock proteins, and inhibit gastric TNF-α concentration [95,98,99,100,101].

3.4. Areas for Improvement of Future Clinical Trials

Due to the many challenges involved in designing rigorous trials utilizing nutritional supplement ingredients, the studies included in this review shared many common issues, which should be addressed during future research. We will highlight those areas here in the hopes of guiding future clinical trials in the service of more accurate and reproducible results.

As many trials lacked proper controls, utilizing prescription or OTC medications, designing future trials that include the use of a placebo is paramount. Additionally, trials enlisting a larger sample size and longer duration are needed, as most trials included in this review had less than 100 subjects and a duration of less than 30 days. Regarding the intervention, determination of a standardized extract composition and dosage is needed, as nutritional compounds often contain many component ingredients. Identifying the active ingredient(s) therein and their associated MoAs is essential for the reproducibility of clinical study results. Furthermore, many of these trials examined ingredients in combination; it is necessary to develop trials examining ingredients in isolation in order to elucidate the specific effect of each individual ingredient.

Controlling for diet is another important feature of rigorous study design; most studies analyzed herein took a heterogenous approach, with some making no mention of diet implementation and others totally changing subjects’ diets to one that would either increase or decrease reflux incidents. It could also be important to assess whether subjects’ dietary intake already involves the bioactive agent of interest, e.g., study subjects who are already on high-fiber diets.

Additionally, a standardized protocol around the usage of prescription and OTC medications before and during the trial would help ensure that results could be integrated between studies and avoid confounding variables. Ensuring that studies are double-blinded and utilize allocation concealment is likewise paramount to optimize the quality of the evidence they can provide. To ensure consistency and reproducibility, studies would do well to use specific validated questionnaires for interval symptom assessments and to use standardized diagnostic criteria for the purposes of recruitment.

4. Conclusions

This review highlights both those nutritional ingredients with robust evidence for managing upper GI conditions and those that, although traditionally associated with upper GI conditions, lack significant data at present. Those with robust evidence include ginger for pregnancy induced nausea and vomiting, and peppermint and caraway oil for functional dyspepsia. Melatonin and marine alginate appear promising for GERD use; a comprehensive systematic review assessing the current body of evidence for melatonin and additional trials investigating marine alginate against a placebo would be helpful to determine their effectiveness and the appropriate dose for each. Fenugreek, galactomannan, and zinc-l-carnosine represent promising areas for further study. Additionally, A. vera, papaya, and licorice are each represented in a handful of trials, but mostly exist in a combinatorial form; further investigation of each ingredient in isolation would help to elucidate their specific effects. The remainder of the nutritional ingredients examined in this review lack substantial data to support their use for upper GI symptoms. While attending to those ingredients with relatively stronger evidence for current clinical applicability, we believe this review may help set a focused research agenda for additional studies moving forward, calling for trials examining dose–response using standardized extract formulations and attending to specific symptomatic benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.S., N.K.A. and J.L.S.; methodology, R.M.S.; formal analysis, R.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.S.; writing—review and editing, R.M.S., J.L.S. and N.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ankita Srivastava, research librarian, for aiding us in the methodology development, as well as Jan Willem Van Klinken and Renee Korczak for their critical input to the structure and methodology of the manuscript as well as written comments and critique.

Conflicts of Interest

At the time this paper was written, RMS was a student intern at GSK and is also a graduate student at the University of Minnesota; NKA has served as a consultant for Medtronic, and GSK, as an advisory board member for GI Supply and Takeda, and has received research support from Nestle and Vanda Pharmaceuticals; JS serves on the scientific advisory board for Simply Good Foods and the Quality Carbohydrate Coalition, and has consulted with GSK on dietary fiber recommendations.

References

- Andreasson, A.; Talley, N.J.; Walker, M.M.; Jones, M.P.; Platts, L.G.; Wallner, B.; Kjellstrom, L.; Hellstrom, P.M.; Forsberg, A.; Agrocus, L. An Increasing Incidence of Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders Over 23 Years: A Prospective Population-Based Study in Sweden. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperber, A.D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Drossman, D.A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Simren, M.; Tack, J.; Whitehead, W.E.; Dumitrascu, D.L.; Fang, X.; Fukudo, S.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 99–114.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, C.J.; Drossman, D.A.; Talley, N.J.; Ruddy, J.; Ford, A.C. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: Advances in understanding and management. Lancet 2020, 396, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delshad, S.D.; Almario, C.V.; Chey, W.D.; Spiegel, B.M.R. Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Proton Pump Inhibitor-Refractory Symptoms. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1250–1261.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fass, R.; Achem, S.R. Noncardiac chest pain: Epidemiology, natural course and pathogenesis. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 17, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brito, B.B.; da Silva, F.A.F.; Soares, A.S.; Pereira, V.A.; Santos, M.L.C.; Sampaio, M.M.; Neves, P.H.M.; de Melo, F.F. Pathogenesis and clinical management of Helicobacter pylori gastric infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 5578–5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, D.A. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1262–1279.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peery, A.F.; Crockett, S.D.; Murphy, C.C.; Lund, J.L.; Dellon, E.S.; Williams, J.L.; Jensen, E.T.; Shaheen, N.J.; Barritt, A.S.; Lieber, S.R.; et al. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 254–272.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifi, A.C.; Axelrod, C.H.; Chakraborty, P.; Saps, M. Herbs and Spices in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review of Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; May, G.; Eckl, V.; Morton Reynolds, C. US Sales of Herbal Supplements Increase by 8.6% in 2019. HerbalGram 2020, 127, 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lahner, E.; Bellentani, S.; Bastiani, R.D.; Tosetti, C.; Cicala, M.; Esposito, G.; Arullani, P.; Annibale, B. A survey of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2013, 1, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSilvestro, R.A.; Verbruggen, M.A.; Offutt, E.J. Anti-heartburn effects of a fenugreek fiber product. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abenavoli, L.; Luigiano, C.; Pendlimari, R.; Fagoonee, S.; Pellicano, R. Efficacy and tolerability of a novel galactomannan-based formulation for symptomatic treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 25, 4128–4138. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cao, H.; Xiao, J. Advances on application of fenugreek seeds as functional foods: Pharmacology, clinical application, products, patents and market. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2342–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalik, A.C.; Bisetto, P.; Pochapski, M.T.; Campagnoli, E.B.; Pilatti, G.L.; Santos, F.A. Effects of an orabase formulation with ethanolic extract of Malva sylvestris L. in oral wound healing in rats. J. Med. Food. 2014, 17, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maton, P.N.; Burton, M.E. Antacids revisited: A review of their clinical pharmacology and recommended therapeutic use. Drugs 1999, 57, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparetto, J.C.; Martins, C.A.F.; Hayashi, S.S.; Otuky, M.F.; Pontarolo, R. Ethnobotanical and scientific aspects of Malva sylvestris L.: A millennial herbal medicine. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ialenti, A.; Di Rosa, M. Hyaluronic acid modulates acute and chronic inflammation. Agents Actions 1994, 43, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Sun, M. A brief review of nutraceutical ingredients in gastrointestinal disorders: Evidence and suggestions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapadia, C.J.; Mane, V.B. Raft-Forming Agents: Antireflux Formulations. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2007, 33, 1350–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suja Pandian, R.; Anuradha, C.V.; Viswanathan, P. Gastroprotective effect of fenugreek seeds (Trigonella foenum graecum) on experimental gastric ulcer in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G.O.; Williams, P.A. (Eds.) Hydrocolloid Thickeners and Their Applications. In Gums and Stabilisers for the Food Industry 12; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2004; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Morozov, S.; Isakov, V.; Konovalova, M. Fiber-enriched diet helps to control symptoms and improves esophageal motility in patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2291–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.X.; Wang, J.W.; Gong, M. Efficacy and safety of alginate formulations in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 24, 11845–11857. [Google Scholar]

- Panahi, Y.; Aslani, J.; Hajihashemi, A.; Kalkhorani, M.; Ghanei, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of aloe vera and pantoprazole on Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in mustard gas victims: A randomized controlled trial. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 22, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Panahi, Y.; Khedmat, H.; Valizadegan, G.; Mohtashami, R.; Sahebkar, A. Efficacy and safety of Aloe vera syrup for the treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: A pilot randomized positive-controlled trial. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 35, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, V.E.; Somi, M.H.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Moaddab, S.-Y.; Lotfi, N. The gastro-protective effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale roscoe) in Helicobacter pylori positive functional dyspepsia. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Nirvanashetty, S.; Parachur, V.A.; Krishnamoorthy, C.; Dey, S. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled, Parallel-Group, Comparative Clinical Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of OLNP-06 versus Placebo in Subjects with Functional Dyspepsia. J. Diet. Suppl. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, R.; Chasen, M.; Elten, M.; MacDonald, N. The effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3279–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.M.; Patel, B.R. A comparative clinical study of Jethimala (Taverniera nummularia Baker.) and Yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza glabra Linn.) in the management of Amlapitta. Ayu 2015, 36, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveendra, K.R.; Jayachandra; Srinivasa, V.; Sushma, K.R.; Allan, J.J.; Goudar, K.S.; Shivaprasad, H.N.; Venkateshwarlu, K.; Geetharani, P.; Sushma, G.; et al. An Extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra (GutGard) Alleviates Symptoms of Functional Dyspepsia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 216970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muss, C.; Mosgoeller, W.; Endler, T. Papaya preparation (CaricolB®) in digestive disorders. Neuro-Endocrinol. Lett. 2013, 34, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weiser, F.-A.; Fangl, M.; Mosgoeller, W. Supplementation of CaricolB®-Gastro reduces chronic gastritis disease associated pain. Neuro-Endocrinol. Lett. 2018, 39, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Son, H.U.; Yoo, C.Y.; Lee, S.H. Low molecular-weight gel fraction of Aloe vera exhibits gastroprotection by inducing matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibitory activity in alcohol-induced acute gastric lesion tissues. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 2110–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazyar, N.; Yaghoobi, R.; Rafiee, E.; Mehrabian, A.; Feily, A. Skin wound healing and phytomedicine: A review. Ski. Pharm. Physiol. 2014, 27, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, N. Inflammation and oxidative stress in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2007, 40, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, T.; Uddin, B.; Hossain, S.; Sikder, A.M.; Ahmed, S. Aloe vera gel protects liver from oxidative stress-induced damage in experimental rat model. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2013, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duansak, D.; Somboonwong, J.; Patumraj, S. Effects of Aloe vera on leukocyte adhesion and TNF-O;± and IL-6 levels in burn wounded rats. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2003, 29, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C.S.; Kim, C.M.; Buller, A.J. Vinegar Improves Insulin Sensitivity to a High-Carbohydrate Meal in Subjects with Insulin Resistance or Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, M.; Ostman, E.; Björck, I. Vinegar dressing and cold storage of potatoes lowers postprandial glycaemic and insulinaemic responses in healthy subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostman, E.; Granfeldt, Y.; Persson, L.; Björck, I. Vinegar supplementation lowers glucose and insulin responses and increases satiety after a bread meal in healthy subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Sam, C.H.Y.; Green, T.; Wood, S. Effect of GutsyGumm, A Novel Gum, on Subjective Ratings of Gastro Esophageal Reflux Following a Refluxogenic Meal. J. Diet. Suppl. 2015, 12, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozgoli, G.; Saei Ghare Naz, M. Effects of Complementary Medicine on Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozgoli, G.; Gharayagh Zandi, M.; Nazem Ekbatani, N.; Allavi, H.; Moattar, F. Cardamom powder effect on nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Complement. Med. J. 2015, 14, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Jafri, M.A.; Farah; Javed, K.; Singh, S. Evaluation of the gastric antiulcerogenic effect of large cardamom (fruits of Amomum subulatum Roxb). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 75, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Javed, K.; Aslam, M.; Jafri, M.A. Gastroprotective effect of cardamom, Elettaria cardamomum Maton. fruits in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 103, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandakumar, P.; Kamaraj, S.; Vanitha, M.K. Dlimonene: A multifunctional compound with potent therapeutic effects. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J.S., Jr. Method for Treating Gastrointestinal Disorder. U.S. Patent US6420435B1, 16 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Asano, T.; Takenaga, M. Restoration of delayed gastric emptying and impaired gastric compliance by anethole in an animal model of functional dyspepsia. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 840.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, F.; Cresi, F.; Castagno, E.; Silvestro, L.; Oggero, R. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a standardized extract of Matricariae recutita, Foeniculum vulgare and Melissa officinalis (ColiMil) in the treatment of breastfed colicky infants. Phytother. Res. 2005, 19, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakil, N.; Laine, L.; Talley, N.J.; Zakko, S.F.; Tack, J.; Chey, W.D.; Kralstein, J.; Earnest, D.L.; Ligozio, G.; Cohard-Radice, M. Tegaserod treatment for dysmotility-like functional dyspepsia: Results of two randomized, controlled trials. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 1906–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palatty, P.L.; Haniadka, R.; Valder, B.; Arora, R.; Baliga, M.S. Ginger in the Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Yusof, Y.A. Gingerol and Its Role in Chronic Diseases. In Drug Discovery from Mother Nature; Gupta, S.C., Prasad, S., Aggarwal, B.B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 177–207. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah Bodagh, M.; Maleki, I.; Hekmatdoost, A. Ginger in gastrointestinal disorders: A systematic review of clinical trials. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.H.; Kim, S.J.; Long, N.P.; Min, J.E.; Yoon, Y.C.; Lee, E.G.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.J.; Yang, Y.Y.; Son, E.Y.; et al. Ginger on Human Health: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of 109 Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.; Hutchinson, S.; Ruggier, R. Zingiber officinale does not affect gastric emptying rate: A randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Anaesthesia 1993, 48, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, H.C.; Sun, W.M.; Chen, Y.H.; Kim, H.; Hasler, W.; Owyang, C. Effects of ginger on motion sickness and gastric slow-wave dysrhythmias induced by circular vection. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003, 284, G481–G489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonlachanvit, S.; Chen, Y.H.; Hasler, W.L.; Sun, W.M.; Owyang, C. Ginger reduces hyperglycemia-evoked gastric dysrhythmias in healthy humans: Possible role of endogenous prostaglandins. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2003, 307, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentis, A.; Lehours, P.; Mégraud, F. Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2015, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selgrad, M.; Kandulski, A.; Malfertheiner, P. Dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori. Dig. Dis. 2008, 26, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, B.H.; Blunden, G.; Tanira, M.O.; Nemmar, A. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): A review of recent research. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilzadeh-Amin, G.; Najarnezhad, V.; Anassori, E.; Mostafavi, M.; Keshipour, H. Antiulcer properties of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. extract on experimental models of gastric ulcer in mice. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 14, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bennett, A.; Clark-Wibberley, T.; Stamford, I.F.; Wright, J.E. Aspirin-induced gastric mucosal damage in rats: Cimetidine and degly-cyhrrhizinated liquorice together give greater protection than low doses of either drug alone. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1980, 32, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Bao, Y.-R.; Li, T.-j.; Yang, G.-L.; Chang, X.; Meng, X.-S. Anti-ulcer effect and potential mechanism of licoflavone by regulating inflammation mediators and amino acid metabolism. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 199, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HMPC. Assessment Report on Glycyrrhiza glabr L. and/or Glycyrrhiza inflata Bat. and/or Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. radix; European Medicine Agency: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–40.

- Asha, M.Z.; Khalil, S.F.H. Efficacy and Safety of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2020, 20, e13–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osato, J.A.; Santiago, L.A.; Remo, G.M.; Cuadra, M.S.; Mori, A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of unripe papaya. Life Sci. 1993, 53, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, S.M.; Chow, S.Y.; Han, P.W. Protective effects of Carica papaya Linn on the exogenous gastric ulcer in rats. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1981, 9, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Han, P.W. Papain reduces gastric acid secretion induced by histamine and other secretagogues in anesthetized rats. Proc. Natl. Sci. Counc. Repub. China B 1984, 8, 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Annahazi, A.; Schroeder, A.; Schemann, M. Region-specific effects of the cysteine protease papain on gastric motility. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ried, K.; Travica, N.; Dorairaj, R.; Sali, A. Herbal formula improves upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms and gut health in Australian adults with digestive disorders. Nutr. Res. 2020, 76, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, A.; Ahuja, N.K. Popular Remedies for Esophageal Symptoms: A Critical Appraisal. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzez, R.; Bartlett, D.; Anggiansah, A. The Effect of Chewing Sugar-free Gum on Gastro-esophageal Reflux. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chumpitazi, B.P.; Kearns, G.L.; Shulman, R.J. Review article: The physiological effects and safety of peppermint oil and its efficacy in irritable bowel syndrome and other functional disorders. Aliment. Pharm. Ther. 2018, 47, 738–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lv, L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Zeng, E.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Tang, X. A Combination of Peppermint Oil and Caraway Oil for the Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 7654947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botschuijver, S.; Welting, O.; Levin, E.; Maria-Ferreira, D.; Koch, E.; Montijn, R.C.; Seppen, J.; Hakvoort, T.B.M.; Schuren, F.H.J.; de Jonge, W.J.; et al. Reversal of visceral hypersensitivity in rat by Menthacarin, a proprietary combination of essential oils from peppermint and caraway, coincides with mycobiome modulation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 30, e13299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micklefield, G.; Jung, O.; Greving; May, B. Effects of intraduodenal application of peppermint oil (WS (R) 1340) and caraway oil (WS (R) 1520) on gastroduodenal motility in healthy volunteers. Phytother. Res. 2003, 17, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecuyer, M.; Cousin, T.; Monnot, M.N.; Coffin, B. Efficacy of an activated charcoal-simethicone combination in dyspeptic syndrome: Results of a placebo-controlled prospective study in general practice. Gastroentérol. Clin. Biol. 2009, 33, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, B.; Bortolloti, C.; Bourgeois, O.; Denicourt, L. Efficacy of a simethicone, activated charcoal and magnesium oxide combination (CarbosymagB®) in functional dyspepsia: Results of a general practice-based randomized trial. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2011, 35, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Luo, H.Q.; Xu, H.; Lv, N.H.; Shi, R.H.; Luo, H.S.; Li, J.S.; Ren, J.L.; Zou, Y.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; et al. Polaprezinc combined with clarithromycin-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis: A prospective, multicenter, randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, T.; Ellis, C.; Levitt, M. Activated charcoal: In vivo and in vitro studies of effect on gas formation. Gastroenterology 1985, 88, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.G., Jr.; Thompson, H.; Strother, A. Effects of orally administered activated charcoal on intestinal gas. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1981, 75, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N.K.; Patel, V.P.; Pitchumoni, S. Activated charcoal, simethicone, and intestinal gas: A double-blind study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1986, 105, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Patel, V.P.; Pitchumoni, C.S. Efficacy of activated charcoal in reducing intestinal gas: A double-blind clinical trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1986, 81, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holtmann, G.; Gschossmann, J.; Karaus, M.; Fischer, T.; Becker, B.; Mayr, P.; Gerken, G. Randomised double-blind comparison of simethicone with cisapride in functional dyspepsia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 13, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtmann, G.; Gschossmann, J.; Mayr, P.; Talley, N.J. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of simethicone and cisapride for the treatment of patients with functional dyspepsia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 16, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klupińska, G.; Wiśniewska-Jarosińska, M.; Harasiuk, A.; Chojnacki, C.; Stec-Michalska, K.; Błasiak, J.; Reiter, R.J.; Chojnacki, J. Nocturnal secretion of melatonin in patients with upper digestive tract disorders. J. Physiol. Pharm. 2006, 57 (Suppl. 5), 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kandil, T.S.; Mousa, A.A.; El-Gendy, A.A.; Abbas, A.M. The potential therapeutic effect of melatonin in Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, C.S.; Yang, Y.J.; Baik, G.H. Melatonin for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease; protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e14241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Murai, I.; Asai, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Matsuno, Y.; Komuro, S.; Kurosaka, H.; Iwasaki, A.; Ishikawa, K.; Arakawa, Y. Central nervous system action of melatonin on gastric acid and pepsin secretion in pylorus-ligated rats. Neuroreport 1998, 9, 3989–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konturek, S.J.; Konturek, P.C.; Brzozowska, I.; Pawlik, M.; Sliwowski, Z.; Cześnikiewicz-Guzik, M.; Kwiecień, S.; Brzozowski, T.; Bubenik, G.A.; Pawlik, W.W. Localization and biological activities of melatonin in intact and diseased gastrointestinal tract (GIT). J. Physiol. Pharm. 2007, 58, 381–405. [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi, A.; Matsuo, H.; Miwa, T.; Namiki, M.; Taniuchi, A.; Masamune, K.; Asaki, S.; Mori, H.; Nakajima, M. Clinical Evaluation of Z-103 on Gastric Ulcer: A multi-center double blind comparative study with Cetraxate Hydrochloride. Jpn. Pharm. Ther. 1992, 20, 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hiraishi, H.; Sasai, T.; Oinuma, T.; Shimada, T.; Sugaya, H.; Terano, A. Polaprezinc protects gastric mucosal cells from noxious agents through antioxidant properties in vitro. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 1999, 13, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsukura, T.; Tanaka, H. Applicability of zinc complex of L-carnosine for medical use. Biochemistry 2000, 65, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hudson, T. A combination of zinc and L-carnosine improves gastric ulcers. Nat. Med. J. 2013, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.K.; Leung, C.C. Ginger extract and polaprezinc exert gastroprotective actions by anti-oxidant and growth factor modulating effects in rats. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, Y. Effect of N-(3-Aminopropionyl)-L-Histidinato Zinc (Z-103) on Healing and Hydrocortisone-Induced Relapse of Acetic Acid Ulcers in Rats with Limited Food-Intake-Time. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1990, 52, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Lim, J.Y.; Chun, H.J.; Lee, M.; Kim, E.S.; Keum, B.; Seo, Y.S.; Jeen, Y.T.; Um, S.H.; Lee, H.S.; et al. The effect of polaprezinc on gastric mucosal protection in rats with ethanol-induced gastric mucosal damage: Comparison study with rebamipide. Life Sci. 2013, 93, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Yagi, N.; Matsuyama, K.; Yoshida, N.; Seto, K.; Yoneta, T. Effects of polaprezinc on lipid peroxidation, neutrophil accumulation, and TNF-alpha expression in rats with aspirin-induced gastric mucosal injury. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001, 46, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).