Abstract

This systematic review assessed genotypes and changes in calcium homeostasis. A literature search was performed in EMBASE, Medline and CENTRAL on 7 August 2020 identifying 1012 references. Studies were included with any human population related to the topic of interest, and genetic variations in genes related to calcium metabolism were considered. Two reviewers independently screened references, extracted relevant data and assessed study quality using the Q-Genie tool. Forty-one studies investigating Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in relation to calcium status were identified. Almost half of the included studies were of good study quality according to the Q-Genie tool. Seventeen studies were cross-sectional, 14 case-control, seven association and three were Mendelian randomization studies. Included studies were conducted in over 18 countries. Participants were mainly adults, while six studies included children and adolescents. Ethnicity was described in 31 studies and half of these included Caucasian participants. Twenty-six independent studies examined the association between calcium and polymorphism in the calcium-sensing receptor (CASR) gene. Five studies assessed the association between polymorphisms of the Vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene and changes in calcium levels or renal excretion. The remaining ten studies investigated calcium homeostasis and other gene polymorphisms such as the CYP24A1 SNP or CLDN14. This study identified several CASR, VDR and other gene SNPs associated with calcium status. However, to provide evidence to guide dietary recommendations, further research is needed to explore the association between common polymorphisms and calcium requirements.

1. Introduction

As one of the most important minerals in the human body, calcium fulfils essential physiological roles such as mineralization of bones and teeth, muscle contraction, blood clotting and transmission of nerve impulses [1]. Ninety-nine percent of total calcium in the body is in bones and teeth [1]. The remaining one percent can be found in blood and body fluids [2]. Its homeostasis is tightly regulated and intra- and extracellular concentration of calcium are maintained through the activation and deactivation of signalling cascades involving mainly the hormone systems parathyroid hormone (PTH) and vitamin D [3,4].

The recommended dietary allowances (RDA) for calcium by the American Institute of Medicine (IOM) is 1000 mg/day for adults aged 19–50 and men until age 70 and 1200 mg/day for women >50 years and men >70 years [5]. The IOM identified the revised tolerable upper intake level for calcium as 2500–3000 mg/day for adults [5]. These levels were determined considering the following indicators: hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, vascular and soft tissue calcification and nephrolithiasis [5]. Calcium balance changes during the life stages and is determined by dietary calcium intake, intestinal calcium absorption and renal reabsorption [1].

Inadequate intake of calcium or increased calcium requirements can lead to calcium deficiency. Long-term calcium deficiency, disruption of PTH secretion or the vitamin D metabolism can cause chronic low levels of serum calcium (hypocalcemia) [6]. Symptoms of low calcium levels may include muscle aches, fatigue, skin sensitivity and in more extreme cases bone fractures due to demineralization, convulsions, arrhythmias and death [6]. The major causes of hypercalcemia or too much calcium are increased bone resorption due to high levels of PTH or increased intestinal calcium absorption due to high levels of vitamin D [7]. Increased levels of serum calcium can weaken bones, lead to the formation of kidney stones, and intervene with functions of the heart and brain [7]. Calcium status depends on multiple factors including genetics. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the calcium-sensing receptor (CASR) such as SNPs rs1801725 A986S [8,9], rs1042636 R990G [10] or rs1801726 Q1011E [11] as well as the vitamin D receptor (VDR) SNP Bsm1 (rs1544410) [12] and Fok1 (rs2228570) [13] have been suggested to be associated with calcium status.

Normal levels of total serum calcium range between 2.12 and 2.62 mmol/L (8.5 and 10.5 mg/dL) [1]. The CASR responds to changes in extracellular calcium. Low levels of extracellular calcium result in signals from the CASR to increase PTH secretion in the parathyroid gland and to decrease thyroid calcitonin (opposing hormone to PTH) secretion [14,15]. To elevate calcium levels to normal ranges, PTH stimulates the mobilization of calcium from bones, absorption of calcium in the intestine and reabsorption in the kidney through increased activation of vitamin D [15,16]. In a feedback mechanism, the increase in calcium results in the suppression of PTH secretion and stimulation of the release of calcitonin through signals from the CASR [1,15]. Calcitonin reduces the uptake of calcium in the kidney and stimulates calcium deposition in the bones [15]. Genetic variations of the CASR gene can lead to disturbances in calcium homeostasis through gain-of-function mutations resulting in a receptor with higher activity, e.g., CASR SNP R990G [17] or a less active receptor as seen for the CASR SNPs A986S [18] and Q1101E [19].

It is not known if polymorphisms of genes involved in calcium regulation result in different dietary requirements of calcium depending on the genotype. Therefore, we systematically assessed genetic factors and calcium status in this review and aimed to summarize the effects of different polymorphisms on calcium homeostasis.

The review was commissioned to inform the work of updating the joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, Rome, Italy) and World Health Organization (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland) calcium requirements in children 0–36 months of age.

2. Materials and Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [20]. The review was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under CRD42021240324.

2.1. Search Methods

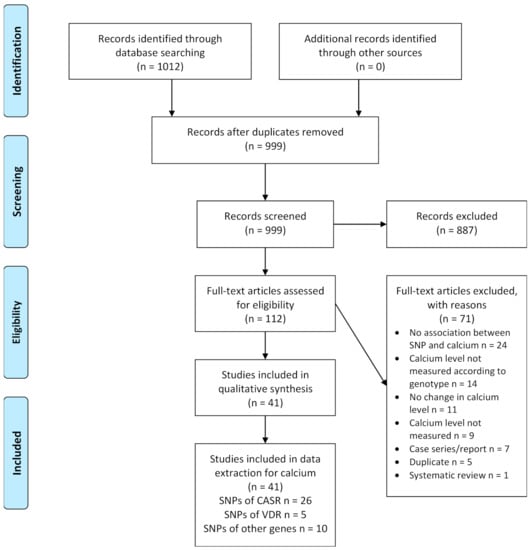

We conducted a literature search in the following databases from inception to 7 August 2020: CENTRAL, EMBASE and Medline (Figure 1). We did not apply any restrictions regarding publication type, date or language. A detailed search strategy is included in the supplement (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. Abbreviations: CASR: calcium-sensing receptor; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; VDR: vitamin D receptor.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Human studies were included related to the topic of interest and genetic variations in genes linked to calcium metabolism were considered. We included any population regardless of age, gender or health status. For context, changes in metabolic status of calcium (e.g., serum calcium concentration, ionized calcium concentration and urinary calcium excretion, calcium absorption) were assessed in any way as no robust biomarker is currently available. Observational and intervention studies were included. Additionally, abstracts were included if the full study was not published. Reviews and systematic reviews were used to identify primary studies for inclusion.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Studies reporting results on gene variants unrelated to calcium metabolism were excluded. Studies which did not mention the metabolic status of calcium (e.g., serum calcium concentration, ionized calcium concentration, urinary calcium excretion, calcium absorption) were excluded. Studies only describing clinical outcomes e.g., higher/lower disease risks without describing changes in calcium, were also excluded. Case reports were excluded as these might describe only rare genetic variants. Other study designs which were excluded were animal and in vitro studies. Abstracts were excluded if the study was already published as a full article.

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4.1. Selection of Studies

The two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the studies using Rayyan [21]. We retrieved full-text articles and assessed them for inclusion. We resolved conflicts through discussion. We manually searched reference lists and reviews of relevant studies.

2.4.2. Data Extraction

We developed an extraction table including the following information: basic study characteristics (year of publication, country, study type), sample description (total number of participants, male and females, age, ethnicity, inclusion and exclusion criteria) and association of genetic variants with calcium status. The two review authors extracted the data into a table which included: SNPs associated with the phenotype (gene, rs#, nucleotide change, amino acid change), prevalence of SNP in the study population, description of SNP and phenotype. SNP association with calcium change including SNP association with calcium intake or calcium supplementation was also included if available. To assess changes in calcium status, the following outcomes were extracted: serum calcium concentration, ionized calcium concentration, urinary calcium excretion or calcium absorption. The data were cross-verified. Any inconsistencies were resolved through discussion.

2.5. Assessment of Study Quality

We used the Quality of Genetic Studies (Q-Genie) tool version 1.1 [22]. The Q-Genie tool contains 11 questions and a quality assessment marked on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 7 (excellent).

The method has been previously described in detail and the assessment tool is available [22]. Briefly, one author respectively assessed all studies, while the other author confirmed assessment. Disagreements were settled through discussion. We assessed the included studies covering the following themes: scientific rational, ascertainment of comparison groups, technical and non-technical classification, outcome (e.g., disease status or quantitative trait), bias, sample size, planned statistical analyses, statistical methods, test of assumptions and interpretation of results [22]. For studies with control groups, total scores of ≤35 indicate poor quality studies, >35 and ≤45 indicate studies of moderate quality, and >45 indicate good quality studies. For studies without control groups, total scores of ≤32 indicate poor quality studies, >32 and ≤40 indicate studies of moderate quality and >40 indicate good quality studies.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Search

The literature search in three databases identified 1012 references. After removal of duplicates, a total of 999 title and abstracts were independently screened by the two review authors. We excluded 887 records and the two review authors independently assessed 112 full-text articles for inclusion by applying the pre-specified eligibility criteria. Of the 71 records excluded at this stage, 24 articles did not show an association between the studied polymorphism and calcium, in 14 articles the calcium levels were not measured according to genotype, no changes in calcium levels were seen in 11 articles, nine did not measure calcium levels at all, seven were case series or case reports, five were duplicates and one article was a systematic review. Finally, we included 41 studies for qualitative synthesis. The process of study selection is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

3.2. Assessment of Study Quality

We assessed the quality of included studies using the Q-Genie tool (Table 1). Nine-teen studies (46%) were of good quality [9,12,19,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], 16 studies (39%) of moderate quality [8,11,13,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] and six studies (15%) of poor quality [10,52,53,54,55,56]. Most studies sufficiently provided a rational for the selected gene or genes in the study and appropriately drew conclusions supported by the presented results. Studies only available as abstracts [8,10,39,53] provided very few methodological details and many items were not sufficiently clear to make a judgement about the study quality. Prior power analysis and an appropriate sample size were not provided in most of the studies. Furthermore, non-technical classification of the exposure was problematic in almost all studies due to insufficient information about the blinding of the assessor who conducted the genotyping or details about the randomisation of samples prior to genotyping.

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment using the Q-Genie tool.

3.3. Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of the included 41 studies are summarized in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4. Studies were carried out between 1999 [13,40,49] and 2019 [9,35]. Twenty-one studies were conducted in Europe [8,10,11,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,38,39,42,43,44,49,50,51,52,54], 10 in Asia [12,24,36,37,45,47,48,53,55,56] and six in North America [13,19,23,25,40,41]. Three studies [9,34,35] included cohorts from different countries while one study provided no country information [46]. Of the included studies, 17 were cross-sectional studies [8,11,13,27,30,33,34,37,38,39,41,45,49,50,51,53,56], 14 were case-control studies [10,12,19,24,29,31,32,36,42,43,47,48,52,55], seven association studies [23,25,26,35,40,46,54] and three were Mendelian randomisation studies [9,28,44]. Twenty-six studies examined the association between calcium and polymorphisms in the CASR gene (Table 2). Five studies examined polymorphisms in the VDR gene and calcium homeostasis (Table 3). Ten studies investigated other gene polymorphisms including AHSG (alpha 2-HS glycoprotein), CALCR (calcitonin receptor), CLDN14 (claudin-14), CYP24A1 (cytochrome P450 family 24 subfamily A member 1), DGKD (diacylglycerol kinase delta), GCKR (glucokinase regulatory protein), GNAS1 (guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha subunit), hKLK1 (human renal kallikrein), LPH (lactase-phlorizin hydrolase); NMU (neuromedin U) and ORAI1 (calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1) (Table 4).

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies assessing polymorphisms of the calcium sensing receptor (CASR).

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies assessing polymorphisms of the vitamin D receptor (VDR).

Table 4.

Characteristics of studies assessing different gene polymorphisms.

3.4. Description of Participants in Included Studies

The total number of participants in included studies ranged from 72 [13] to 184,205 [28]. Six studies included only female participants [19,40,41,44,45,53] and two only male participants [47,49]. Five studies were conducted in children [13,23,34,52,54], one in adolescent girls [44] and in one study it was unclear if patients included only adults or also children [10]. The remaining studies included adults of different ages. Ethnicity was described in 31 studies: 15 studies included Caucasians [11,27,29,32,34,38,39,40,41,42,44,49,50,51,54], two studies Indians [24,55], Japanese [12,56], one study Africa-Americans [25], Chinese [53], Korean [37], Taiwanese [36] and eight studies included multi-ethnic participants [9,13,19,23,26,28,35,46]. In 10 studies, no information on participants’ ethnicity was provided [8,10,30,31,33,43,45,47,48,52]. Twenty-two studies included healthy participants [8,9,11,13,23,25,26,27,34,37,38,39,40,41,43,44,46,49,51,53,54,56], six studies included patients with kidney or urinary stones [24,32,35,47,48,55], four with primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) [10,30,31,42], two with coronary artery disease (CAD) [28,29] or hypertension [12,33], and one with vitamin D deficiency (VDD) [45], hypercalciuria [52], cancer [19], cardiovascular risk factors [50] or chronic kidney disease (CKD) [36].

3.5. Calcium and Polymorphism of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor (CASR)

Twenty-six independent studies were identified that assessed the association of polymorphisms of the CASR gene and changes in calcium levels or renal excretion (Table 2). Seventeen out of 26 studies examined the SNP rs1801725 (G/T, A986S, Ala > Ser) [8,9,11,19,23,24,26,27,28,29,32,40,41,44,45,48,52]. Except three studies which looked at renal calcium excretion [32,48,52], all studies assessed the association between SNP and serum calcium levels. Healthy women homozygous for A986 (GG) had lower serum calcium levels corrected for albumin compared with heterozygotes A986S (GT) [40] and the result was confirmed for serum calcium levels without correction for albumin in a follow-up study with a greater number of participants [41]. Ionized calcium levels were lower in healthy adults with the common GG genotype compared with GT or TT genotypes [11,27]. Kidney stone formers [24] or breast cancer patients [19] as well as healthy controls with the more common genotype GG showed lower serum calcium levels compared with GT and TT genotypes together. Cerani et al. investigated various SNPs in different genes and found an increase in serum calcium by 0.0178 mmol/L (0.0713 mg/dL) for the calcium increasing allele T in CASR rs1801725 [9]. Also, Larsson et al. showed an increase in serum calcium by 0.0177 mmol/L (0.071 mg/dL) per additional T allele in patients with CAD [28] and each T allele yield a calcium increase of 0.01874 mmol/L (0.0751 mg/dL) in a large genome-wide association study [26]. März et al. reported significantly higher serum calcium levels and calcium levels adjusted for albumin for patients with or without CAD carrying the GT or TT genotype compared with the GG genotype [29]. Healthy carriers of the T allele had significantly higher serum calcium levels [8] or higher serum calcium levels corrected for albumin in another study of healthy females [44]. One study also showed an association of the SNP with serum calcium level for the minor allele T in African-Americans and European-Americans [23]. No association between different genotypes and serum calcium level was found in adult women with VDD [45]. In kidney stone formers, carriers of the different alleles for the SNP rs1801725 reported no differences in 24 h urinary calcium excretion or serum calcium concentration between wild type and mutant [48]. In one study examining the three common CASR SNPs rs1801725 (A986S), rs1042636 (R990G) and rs1801726 (Q1011E) in kidney stone formers and healthy controls, higher urinary calcium excretion was reported in participants with rs1801725 GG, rs1042636 GG or AG, rs1801726 CC genotype compared with participants with rs1801725 GG, rs1042636 AA, rs1801726 CC genotype [32]. One study investigated the SNP rs1801725 in children with idiopathic hypercalciuria and healthy controls and found a positive association in the T allele with renal calcium excretion, independent of age and serum levels of calcium, intact parathormone and 25-hydroxy-vitamin D [52].

The second most studied polymorphism of the CASR gene was rs1042636 (A/G, R990G, Arg > Gly) which was investigated in 11 studies [8,10,11,24,30,32,42,45,48,52,53]. The common AA genotype showed higher ionized calcium levels compared with the AG genotype in healthy adults [11] and also higher serum calcium levels for the AA genotype compared with the genotypes AG or GG in adult females with VDD [45], healthy young Chinese women [53], or kidney stone formers and healthy controls [48]. Furthermore, in one study examining the association of the three most common SNPs rs1801725, rs1042636 and rs1801726 and calcium, carriers of TG (rs1801725) AA (rs1042636) GC (rs1801726) had significantly higher serum calcium levels compared to the most common haplotype GG AA CC [8]. In contrast, PHPT patients carrying minor alleles in two CASR SNPs rs1042636 (GG or GA) and rs1501899 (AA or GA) had higher serum ionized calcium and higher urine calcium compared with patients carrying wild type alleles at both SNPs [30]. PHPT patients [10,42] or kidney stone formers [24,32] carrying the GG or AG genotype showed higher urinary calcium excretion compared with homozygotes for the 990R allele (AA genotype). One study investigated the SNP rs1042636 in children with idiopathic hypercalciuria and healthy controls, but did not report changes in calcium levels or renal excretion [52].

Five studies assessed the CASR SNP rs1801726 (G/A,C, Q1011E, Gln > Glu) [8,11,32,48,52]. Of those, three showed higher serum calcium levels for the GC genotype compared with the more common CC genotype in healthy participants [8,11] as well as kidney stone formers [48]. In kidney stone formers and healthy controls, heterozygous participants with GC had lower urinary calcium excretion compared with CC homozygotes, but there were no differences in plasma calcium levels [32]. One study investigated the SNP rs1801726 in children with idiopathic hypercalciuria and healthy controls, but did not report on changes in calcium levels or renal excretion [52].

Two studies examined the SNP rs17251221 (A/G) [43,46]; Jorde et al. showed significantly higher serum calcium levels for the GG genotype compared with the AA genotype [43]. O’Seaghdha et al. also confirmed an association of the SNP with 0.015 mmol/L (0.06 mg/dL) higher serum calcium levels per copy of the minor G allele in healthy participants [46].

One study identified an association between CASR rs11716910 (A/G) and serum calcium levels (corrected for albumin) and showed that healthy individuals with the AA genotype had higher levels than those with the AG and GG genotypes [39]. Jung et al. investigated 15 SNPs in the CASR gene and found that the six SNPs rs6438712 (A/G), rs4678172 (G/T), rs9874845 (A/T), rs4678059 (A/T), rs1965357 (C/T) and rs937626 (A/G) were associated with lower urinary calcium excretion for African-Americans carrying the minor alleles [25]. Vezzoli et al. 2011 looked at two SNPs in the regulatory region of the CASR gene in PHPT patients and healthy controls: rs7652589 (G/A) and rs1501899 (G/A) [31]. They found higher serum ionized calcium and higher urine calcium for PHPT patients with the diplotype AA/AA or AA/GG versus GG/GG [31].

3.6. Calcium and Polymorphism of the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR)

Five studies [12,13,49,54,55] assessed the association between polymorphisms for the VDR gene and changes in calcium levels or renal excretion (Table 3). Three studies examined the VDR SNP Bsm1 (rs1544410, A/G) [12,49,55]. In healthy subjects, intake of a high calcium-phosphate diet resulted in higher calcium concentrations in fasting urine and higher daily calcium excretion in subjects carrying the mutant bb genotype compared with the wild type BB genotype, but there was no difference between genotypes for serum ionized calcium, urinary calcium or daily urinary calcium excretion without dietary modifications [49]. Participants consumed products rich in calcium and phosphate and additionally 1000 mg elemental phosphorus per day as potassium-phosphorus syrup for five days (high calcium-phosphate diet) [49]. Urinary calcium excretion was higher for the bb genotype in nephrolithiatic subjects with or without hypercalciuria [55] and total and ionized serum calcium levels were lower in normotensive or hypertensive subjects with the BB genotype [12].

Two studies examined the VDR SNP Fok1 (rs2228570, C/T) [13,55]. Healthy children with the wild type FF genotype showed a greater calcium absorption compared with the mutant ff or Ff [13]. Serum calcium was significantly higher in hypercalciuric nephrolithiatic subjects with the ff genotype compared with FF or Ff genotypes and FF and Ff genotypes showed higher renal calcium excretion compared with ff [55].

In another study, the VDR SNP rs4516035 (−1012 G/A) was significantly associated with serum calcium levels (adjusted for serum protein levels) and the GG genotype in healthy children and adolescents showed lower levels compared with GA or AA genotypes [54].

3.7. Calcium and Polymorphism of Other Genes

Ten independent studies examined the association between calcium homeostasis and polymorphisms in various genes (Table 4). Seven studies [34,35,36,37,38,50,51] found a link with serum calcium levels and three with renal calcium excretion [33,47,56]. In patients with one or more cardiovascular risk factors, the AHSG (alpha 2-HS glycoprotein) SNP rs4918 (G/C, T256S) was associated with lower calcium levels for patients carrying the CC genotype compared with the GC or GG genotypes [50]. Another study by Gianfagna et al. examined NMU (neuromedin U) SNP rs9999653 (major/minor C/T) and found a significant association between the CC genotype and lower serum calcium levels [34]. In a multi-ethnic study on kidney stone disease, CYP24A1 (cytochrome P450 family 24 subfamily A member 1) SNP rs17216707 (T/C) showed higher serum calcium levels for participants carrying the TT genotype compared with those carrying the TC but not CC genotype [35]. In the same study, DGKD (diacylglycerol kinase delta) rs838717(A/G) was associated with lower 24 h renal calcium excretion for male patients carrying the AA genotype compared with GG [35]. Hwang et al. looked at the influence of the SNP rs12313273 (C/T) in the ORAI1 (calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1) gene in CKD patients and found that serum calcium concentration was significantly higher in carriers of the C allele compared with T carriers [36]. One study examined the association of the SNPs rs780093 (T/C), rs780094 (T/C) and rs1260326 (T/C) in the GCKR (glucokinase regulatory protein) gene in healthy participants [37]. Participants with the minor CC genotype displayed significantly decreased serum calcium levels compared with participants with the TT genotype for all three investigated SNPs. One study identified an association between the LPH (lactase-phlorizin hydrolase) polymorphism rs498823 (G/C) and calcium levels, where C-homozygotes had lower ionized calcium levels compared with G homo- or heterozygotes, but there was no difference in total serum calcium levels between genotypes [38]. Another study assessed the GNAS1 (guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha subunit) gene polymorphism (T/C) and showed that healthy participants with the minor C allele had lower serum calcium levels compared with the major T allele [51].

One study looked at the different SNPs in the 3′ region of the claudin-14 gene and found the strongest association between the CLDN14 SNP rs219755 (G/A) and 24 h-urinary calcium excretion with higher excretion for the GG genotype compared with GA or AA in patients with hypertension [33]. In healthy Japanese volunteers, the polymorphism in the hKLK1 (human renal kallikrein) gene (promoter region, H allele: with nucleotide substitution 130(G)11) was associated with higher fractional calcium excretion in the urine and higher calcium excretion per creatinine in the urine of subjects with the H allele compared with subjects without the H allele [56]. Shakhssalim et al. 2014 studied different SNPs in the CALCR (calcitonin receptor) gene and found significantly higher urine calcium concentrations for hetero- or homozygotes (patients with T allele) compared with the wild type for the 3′UTR + 18C > T polymorphism in kidney stone formers (calcium urinary stones) [47].

4. Discussion

Calcium is an essential micronutrient critical to human physiology, particularly bone and dental health. It cannot be produced in the body and needs to be obtained through a balanced diet. Genetic factors, such as polymorphisms of genes involved in calcium signalling, can influence calcium homeostasis [26,36]. However, it is unknown whether these genetic variations directly affect dietary requirements of calcium. In this context, our systematic review aimed to assess and summarize genetic factors contributing to changes in calcium status. We identified 41 studies for inclusion and about half (46%) were of good study quality. Twenty-six studies examined the association between polymorphism in the CASR gene and changes in serum calcium levels or renal calcium excretion, five between polymorphism in the VDR gene and calcium and 10 studies investigated the relationship between different gene polymorphisms and calcium.

The extracellular CASR plays a pivotal role in maintaining calcium homeostasis and is highly expressed in the parathyroid glands and the kidneys [14]. To regulate calcium levels, the receptor detects changes in extracellular calcium concentration and mediates the secretion of PTH and calcium absorption in the kidney [14,57]. Various mutations in the CASR gene leading to diseases such as familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH; loss-of-function mutation) or hypocalcemia (gain-of-function mutation) have been described [46]. Polymorphisms of the CASR gene have been associated with changes in calcium status; the three polymorphisms A986S (rs1801725), R990G (rs1042636) and Q1011E (rs1801726) have been intensely studied and seem to be of clinical importance [8,11,32,48,52]. The polymorphism A986S (rs1801725) results in a shift from alanine to serine at codon 986 and probably in a less active receptor [18]. Participants carrying the minor T allele had significantly higher serum calcium levels [8,9,11,19,23,24,26,27,28,29,40,41,44]. This observation was independent of the health status of study participants leading to the speculation that healthy individuals [8,9,11,23,26,27,40,41,44], kidney stone formers [24], breast cancer patients [19] and CAD patients [28,29] with the minor genotypes GT or TT may have lower calcium requirements compared with individuals carrying the major genotype GG. However, none of these studies examined dietary calcium intake or calcium supplementation.

R990G (rs1042636) and Q1011E (rs1801726) are also common polymorphisms of the CASR gene and have been associated with calcium levels [11]. The CASR polymorphism rs1042636 leads to an amino acid change from arginine to glycine at codon 990 which results in a receptor with higher activity [17]. The common AA genotype showed higher calcium levels compared with the mutant AG or GG genotype in healthy study participants [11,53], women with VDD [45] or kidney stone formers [48]. Furthermore, PHPT patients [10,42] or kidney stone formers [24,30,32] carrying the mutant AG or GG genotype had higher urinary calcium excretion compared with the wild type AA genotype. The CASR SNP rs1801726 (Q1011E) results in a cytosine-guanine substitution at codon 1011 and reduced receptor function [19]. The mutant GC genotype led to higher serum calcium levels compared with the wild type (CC) in healthy individuals [8,11] as well as kidney stone formers [48]. Our review also identified studies examining less common SNPs in the CASR gene which resulted in alteration of serum calcium levels and/or renal calcium excretion [25,31,39,43,46]. Depending on the genotype expressed, these studies suggest an association between the polymorphism and calcium homeostasis which potentially could influence calcium requirements. Dietary recommendations for calcium according to the expressed genotype need to take into account the interaction of different polymorphisms and calcium homeostasis as well as calcium intake. The study of the interaction between dietary factors and common polymorphism can help us understand calcium requirements for good health and in disease [58,59]. For example, previous reviews have investigated genetic variants of zinc-transporters and dietary zinc requirements [60], genetic factors influencing vitamin D deficiency [61] or the effects of polymorphism in folate and vitamin B12 genes on metabolism and intake [62]. The gene-nutrient interactions are complex and interpretation of results can be challenging; nevertheless, the studies identified in this review clearly demonstrate changes in calcium status depending on the genotype expressed. These polymorphisms of the CASR gene may be interesting candidates to study the gene-nutrient interaction and an individual’s response to differences in calcium intake or supplementation. However, included studies failed to report important confounders such as calcium intake of participants according to genotype. This makes it difficult to compare results from different studies and to draw conclusions about SNPs and the regulation of calcium. Therefore, further research should consider potential lifestyle-related confounders when conducting studies and interpreting results. Furthermore, it would be important to investigate if any individuals are at risk of adverse calcium-related outcomes that would require the need for higher or lower calcium intake.

Vitamin D in its active, hormonal form (calcitriol or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) binds to the nuclear VDR and mediates calcium homeostasis through three mechanisms: increasing calcium absorption in the intestine, stimulating calcium release from bones and reabsorption of calcium in the kidney [1,3]. The latter two processes require PTH [1]. Mutations in the VDR gene can hinder the effect of vitamin D on calcium regulation and may result in diseases such as vitamin D-resistant rickets type 2a (VDDR2A), a condition described with hypocalcemia, hyperparathyroidism and rickets [3,63]. Among the five studies included in this review that assessed polymorphisms in the VDR gene and calcium changes, three examined the SNP Bsm1 (rs1544410, A/G) which is located in an intronic region of the receptor [12,49,55]. In one study, the wild type allele BB was associated with lower serum calcium compared with the mutant genotype bb [12] while the other two studies looked at renal calcium excretion [49,55]. Ferrari et al. was the only study which assessed the influence of dietary modifications and calcium changes according to genotype [49]. Participants in this study consumed a diet restricted in calcium and phosphate for the first five days, achieved through counselling and the intake of magnesium- and aluminium-containing phosphorus binder. After a washout period, participants received a diet with products rich in calcium and phosphate plus 1000 mg elemental phosphorus per day for five days. Phosphorus is another essential mineral of bones and teeth and its homeostasis is regulated by PTH and calcitriol [64]. This study found higher fasting urinary calcium and higher daily calcium excretion in the urine in healthy participants receiving a high or low calcium-phosphate diet with the bb genotype compared with the wild type BB [49]. Furthermore, renal phosphate (salt of the phosphorus oxoacid) reabsorption capacity and plasma levels were higher in participants with the bb genotype compared with BB, an effect independent of dietary modification (high or low calcium-phosphate diet). This study suggests that polymorphisms in the VDR gene interact with dietary factors and the response to changes in the diet depends on the genotype expressed. However, different dietary sources of calcium or phosphorus and their influence on the observations were not examined and discussed in the study. Two studies examined the Fok1 (rs2228570, C/T) polymorphism in the start codon of the VDR gene and found greater calcium absorption for the wild type FF genotype in healthy children [13], but hypercalciuric nephrolithiatic participants with the FF or Ff genotype showed lower serum calcium levels and higher renal calcium excretion [55]. The results suggest that genetic variations in the VDR gene result in change of function of the receptor which alters calcium homeostasis. However, the relevance of these SNPs and changes in serum or urinary calcium in response to calcium intake or supplementation need to be further investigated.

In addition to the aforementioned SNPs in CASR and VDR gene, our review identified a number of polymorphisms in genes which may play a direct or indirect role in calcium homeostasis. For example, the enzyme CYP24A1 is involved in vitamin D metabolism and is responsible for the degradation of calcitriol [1,35]. The SNP rs17216707 (T/C) in the CYP24A1 gene resulted in higher serum calcium levels for individuals carrying the TT genotype compared with the TC genotype due to a reduced enzyme activity [35]. The authors suggested that individuals with the TT genotype may be more sensitive to vitamin D and supplementation with vitamin D could potentially increase the risk of kidney stones due to the development of hypercalcemia [35].

Several included studies reported on genetic factors influencing renal calcium excretion [10,24,25,30,31,32,33,35,47,48,49,52,55,56]. However, none of the included studies in this review assessed faecal calcium excretion. Previous research has shown that dietary calcium intake has an influence on calcium homeostasis (e.g., calcium absorption, renal and faecal excretion) and other dietary factors such as faecal fat excretion [65,66,67]. Further studies should take these relationships into account and also assess potential influences of polymorphisms on faecal calcium excretion.

During phases of development, sufficient intake of minerals is extremely important for the growing child. Calcium requirements increase for bone mineralization especially during the neonatal period and puberty [1,68]. For example, the favourable FF genotype of the VDR Fok1 polymorphism resulted in greater calcium absorption and higher bone mineral density in prepubertal and pubertal children [13]. This is consistent with another study showing 20% less calcium absorption and bone mineralization during pubertal growth for the ff genotype compared with the FF genotype [69]. Polymorphisms in CASR or VDR mediated regulation of calcium homeostasis can affect bone formation and growth in children and adolescents [13,23,34,44,52,54]. However, studies lack important information such as calcium intake (according to genotype) and physical activity which can have an influence on mineral levels in children and adolescents.

Polymorphisms in the CASR, VDR gene or other genes such as CYP24A1, GNAS1 or DGKD, may contribute to the genetic regulation of calcium status. However, except one study, none of the included studies explored gene-nutrient interactions in response to calcium intake or supplementation. Further investigations are needed to explore this relationship. This may reveal if individuals carrying a particular genotype respond to dietary factors differently and require individual recommendations for dietary calcium intake or supplementation.

5. Conclusions

This review assessed genetic variations and calcium homeostasis. We identified several studies assessing polymorphisms in the CASR and VDR gene and other genes directly or indirectly involved in the regulation of calcium status. Studies showed changes in calcium levels or renal excretion according to the SNP and it may be of importance to consider if individuals have different calcium requirements depending on the genotype expressed. However, with the exception of one study, none of the included studies assessed the interaction of genes and nutrients through dietary supplementation studies. Therefore, it is unclear if different genotypes lead to different calcium requirements. This highlights the need for further research to explore the effects of genetic variants of genes involved in calcium homeostasis and calcium intake through the diet or supplementation. The results of this review should be interpreted with caution and further research is necessary to develop recommendations for calcium requirements that consider polymorphisms known to change calcium status.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu13082488/s1, Table S1: Search strategy in Medline and EMBASE.

Author Contributions

K.d.S.L. and S.K.A. performed the study selection, assessment of study quality and data extraction. K.d.S.L. together with S.K.A. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO), WHO Reference 2020/106272-0.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank FAO and WHO for conceptualizing this research, performing the literature search and giving valued advice during the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; Ross, A.C., Taylor, C.L., Yaktine, A.L., Del Valle, H.B., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; p. 3, Overview of Vitamin D. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56060/ (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Shaker, J.L.; Deftos, L. Calcium and Phosphate Homeostasis. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Grossman, A., Hershman, J.M., Hofland, J., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279023/ (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Bonny, O.; Bochud, M. Genetics of calcium homeostasis in humans: Continuum between monogenic diseases and continuous phenotypes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 29, iv55–iv62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pu, F.; Chen, N.; Xue, S. Calcium intake, calcium homeostasis and health. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2016, 5, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What clinicians need to know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bove-Fenderson, E.; Mannstadt, M. Hypocalcemic disorders. Best Pract. Research Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 32, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, N.; Carmichael, K.A. Evaluation and therapy of hypercalcemia. Mo. Med. 2011, 108, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Annerbo, M.; Lind, L.; Bjorklund, P.; Hellman, P. Association between calcium sensing receptor polymorphisms and serum calcium in a Swedish well-characterized cohort. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Cerani, A.; Zhou, S.; Richards, J.B.; Forgetta, V.; Morris, J.A.; Trajanoska, K.; Rivadeneira, F.; Larsson, S.; Michaelsson, K. Genetic predisposition to increased serum calcium on bone mineral density and the risk of fracture in individuals with normal calcium levels: A Mendelian randomization study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2019, 34, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, T.; Rainone, F.; Paloschi, V.; Scillitani, A.; Terranegra, A.; Dogliotti, E.; Guarnieri, V.; Aloia, A.; Borghi, L.; Guerra, A.; et al. Polymorphisms of the calcium-sensing receptor gene and stones in primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch. Ital. Di Urol. E Androl. 2009, 81, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Scillitani, A.; Guarnieri, V.; De Geronimo, S.; Muscarella, L.A.; Battista, C.; D’Agruma, L.; Bertoldo, F.; Florio, C.; Minisola, S.; Hendy, G.N.; et al. Blood ionized calcium is associated with clustered polymorphisms in the carboxyl-terminal tail of the calcium-sensing receptor. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5634–5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Oshima, T.; Sasaki, S.; Yamaoka, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Hirao, H.; Ozono, R.; Matsuura, H.; Kajiyama, G.; Kambe, M. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism is associated with serum total and ionized calcium concentration. J. Mol. Med. 2000, 78, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, S.K.; Ellis, K.J.; Gunn, S.K.; Copeland, K.C.; Abrams, S.A. Vitamin D receptor gene Fok1 polymorphism predicts calcium absorption and bone mineral density in children. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999, 14, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.M.; MacLeod, R.J. Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 239–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Verdes, L.M.; Costa-Silva, D.R.; da Silva-Sampaio, J.P.; Barros-Oliveira, M.D.C.; Escórcio-Dourado, C.S.; Martins, L.M.; Sampaio, F.A.; Revoredo, C.; Alves-Ribeiro, F.A.; da Silva, B.B. Review of Polymorphism of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor Gene and Breast Cancer Risk. Cancer Investig. 2018, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, A.L.; Ward, B.K.; Ratajczak, T. The calcium-sensing receptor: A molecular perspective. Endocr. Rev. 2011, 32, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, G.; Terranegra, A.; Arcidiacono, T.; Biasion, R.; Coviello, D.; Syren, M.L.; Paloschi, V.; Giannini, S.; Mignogna, G.; Rubinacci, A.; et al. R990G polymorphism of calcium-sensing receptor does produce a gain-of-function and predispose to primary hypercalciuria. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, F.H.; Wong, B.Y.; Chase, M.; Shuen, A.Y.; Canaff, L.; Thongthai, K.; Siminovitch, K.; Hendy, G.N.; Cole, D.E. Genetic variation at the calcium-sensing receptor (CASR) locus: Implications for clinical molecular diagnostics. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Widatalla, S.E.; Whalen, D.S.; Ochieng, J.; Sakwe, A.M. Association of calcium sensing receptor polymorphisms at rs1801725 with circulating calcium in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, Z.N.; Meyre, D.; de Souza, R.J.; Joseph, P.G.; Gandhi, M.; Dennis, B.B.; Norman, G.; Anand, S.S. Assessing the quality of published genetic association studies in meta-analyses: The quality of genetic studies (Q-Genie) tool. BMC Genet. 2015, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Wei, Z.; Mentch, F.D.; Hou, C.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, H.; Kim, C.; Sleiman, P.M.A.; et al. Genome-wide association study of serum minerals levels in children of different ethnic background. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, M.; Bankura, B.; Ghosh, S.; Pattanayak, A.K.; Ghosh, S.; Pal, D.K.; Puri, A.; Kundu, A.K.; Das, M. Polymorphisms in CaSR and CLDN14 genes associated with increased risk of kidney stone disease in patients from the eastern part of India. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Foroud, T.M.; Eckert, G.J.; Flury-Wetherill, L.; Edenberg, H.J.; Xuei, X.; Zaidi, S.A.; Pratt, J.H. Association of the calcium-sensing receptor gene with blood pressure and urinary calcium in african-americans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, K.; Johnson, T.; Beckmann, N.D.; Sehmi, J.; Tanaka, T.; Kutalik, Z.; Styrkarsdottir, U.; Zhang, W.; Marek, D.; Gudbjartsson, D.F.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis for serum calcium identifies significantly associated SNPs near the calcium-sensing receptor (CASR) gene. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, M.M.L.; Outila, T.A.; Kärkkäinen, M.U.M.; Kemi, V.E.; Rita, H.J.; Perola, M.; Valsta, L.M.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.J.E. Associations of vitamin D receptor, calcium-sensing receptor and parathyroid hormone gene polymorphisms with calcium homeostasis and peripheral bone density in adult Finns. J. Nutr. Nutr. 2009, 2, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Burgess, S.; Michaëlsson, K. Association of genetic variants related to serum calcium levels with coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2017, 318, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- März, W.; Seelhorst, U.; Wellnitz, B.; Tiran, B.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Renner, W.; Boehm, B.O.; Ritz, E.; Hoffmann, M.M. Alanine to serine polymorphism at position 986 of the calcium-sensing receptor associated with coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, all-cause, and cardiovascular mortality. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 2363–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, G.; Scillitani, A.; Corbetta, S.; Terranegra, A.; Dogliotti, E.; Guarnieri, V.; Arcidiacono, T.; Macrina, L.; Mingione, A.; Brasacchio, C.; et al. Risk of nephrolithiasis in primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with two polymorphisms of the calcium-sensing receptor gene. J. Nephrol. 2014, 28, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, G.; Scillitani, A.; Corbetta, S.; Terranegra, A.; Dogliotti, E.; Guarnieri, V.; Arcidiacono, T.; Paloschi, V.; Rainone, F.; Eller-Vainicher, C.; et al. Polymorphisms at the regulatory regions of the CASR gene influence stone risk in primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur. J. Endocrinol. Suppl. 2011, 164, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, G.; Tanini, A.; Ferrucci, L.; Soldati, L.; Bianchin, C.; Franceschelli, F.; Malentacchi, C.; Porfirio, B.; Adamo, D.; Falchetti, A.; et al. Influence of calcium-sensing receptor gene on urinary calcium excretion in stone-forming patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 2517–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, T.; Simonini, M.; Lanzani, C.; Citterio, L.; Salvi, E.; Barlassina, C.; Spotti, D.; Cusi, D.; Manunta, P.; Vezzoli, G. Claudin-14 gene polymorphisms and urine calcium excretion. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfagna, F.; Cugino, D.; Ahrens, W.; Bailey, M.E.S.; Bammann, K.; Herrmann, D.; Koni, A.C.; Kourides, Y.; Marild, S.; Molnár, D.; et al. Understanding the Links among neuromedin U Gene, beta2-adrenoceptor Gene and Bone Health: An Observational Study in European Children. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howles, S.A.; Wiberg, A.; Goldsworthy, M.; Bayliss, A.L.; Gluck, A.K.; Ng, M.; Grout, E.; Tanikawa, C.; Kamatani, Y.; Terao, C.; et al. Genetic variants of calcium and vitamin D metabolism in kidney stone disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, D.Y.; Chien, S.C.; Hsu, Y.W.; Kao, C.C.; Cheng, S.Y.; Lu, H.C.; Wu, M.S.; Chang, J.M. Genetic polymorphisms of ORAI1 and chronic kidney disease in Taiwanese population. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.Y.; Kwak, S.Y.; Lim, H.; Shin, M.J. Genotype effects of glucokinase regulator on lipid profiles and glycemic status are modified by circulating calcium levels: Results from the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study. Nutr. Res. 2018, 60, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koek, W.N.H.; Van Meurs, J.B.; Van Der Eerden, B.C.J.; Rivadeneira, F.; Zillikens, M.C.; Hofman, A.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Lips, P.; Pols, H.A.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; et al. The T-13910C polymorphism in the lactase phlorizin hydrolase gene is associated with differences in serum calcium levels and calcium intake. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochud, M.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P. Calcium and vitamin D supplements modify the effect of the rs11716910 CASR variant on serum calcium in the population-based CoLaus study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2011, 49, A15–A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cole, D.E.C.; Peltekova, V.D.; Rubin, L.A.; Hawker, G.A.; Vieth, R.; Liew, C.C.; Hwang, D.M.; Evrovski, J.; Hendy, G.N. A986S polymorphism of the calcium-sensing receptor and circulating calcium concentrations. Lancet 1999, 353, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.E.C.; Vieth, R.; Trang, H.M.; Wong, B.Y.L.; Hendy, G.N.; Rubin, L.A. Association between total serum calcium and the A986S polymorphism of the calcium-sensing receptor gene. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2001, 72, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, S.; Eller-Vainicher, C.; Filopanti, M.; Saeli, P.; Vezzoli, G.; Arcidiacono, T.; Loli, P.; Syren, M.L.; Soldati, L.; Beck-Peccoz, P.; et al. R990G polymorphism of the calcium-sensing receptor and renal calcium excretion in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 155, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorde, R.; Schirmer, H.; Njølstad, I.; Løchen, M.L.; Bøgeberg Mathiesen, E.; Kamycheva, E.; Figenschau, Y.; Grimnes, G. Serum calcium and the calcium-sensing receptor polymorphism rs17251221 in relation to coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer and mortality: The Tromsø Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 28, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzon, M.; Lorentzon, R.; Lerner, U.H.; Nordström, P. Calcium sensing receptor gene polymorphism, circulating calcium concentrations and bone mineral density in healthy adolescent girls. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2001, 144, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, H.; Khan, A.H.; Moatter, T. R990G polymorphism of calcium sensing receptor gene is associated with high parathyroid hormone levels in subjects with vitamin D deficiency: A cross-sectional study. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Seaghdha, C.M.; Yang, Q.; Glazer, N.L.; Leak, T.S.; Dehghan, A.; Smith, A.V.; Kao, W.L.; Lohman, K.; Hwang, S.J.; Johnson, A.D.; et al. Common variants in the calcium-sensing receptor gene are associated with total serum calcium levels. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 4296–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhssalim, N.; Basiri, A.; Houshmand, M.; Pakmanesh, H.; Golestan, B.; Azadvari, M.; Aryan, H.; Kashi, A.H. Genetic polymorphisms in calcitonin receptor gene and risk for recurrent kidney calcium stone disease. Urol. Int. 2014, 92, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhssalim, N.; Kazemi, B.; Basiri, A.; Houshmand, M.; Pakmanesh, H.; Golestan, B.; Eilanjegh, A.F.; Kashi, A.H.; Kilani, M.; Azadvari, M. Association between calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphisms and recurrent calcium kidney stone disease: A comprehensive gene analysis. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 2010, 44, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Manen, D.; Bonjour, J.P.; Slosman, D.; Rizzoli, R. Bone mineral mass and calcium and phosphate metabolism in young men: Relationships with vitamin D receptor allelic polymorphisms. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 2043–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, C.; Agnello, L.; Lo Sasso, B.; Milano, S.; Bivona, G.; Scazzone, C.; Pivetti, A.; Novo, G.; Palermo, C.; Bonomo, V.; et al. Fetuin-A is Associated to Serum Calcium and AHSG T256S Genotype but Not to Coronary Artery Calcification. Biochem. Genet. 2016, 54, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, L.; Del Monte, F.; Gozzini, A.; De Feo, M.L.; Gheri, R.G.; Neri, A.; Falchetti, A.; Amedei, A.; Imbriaco, R.; Mavilia, C.; et al. A novel polymorphism at the GNAS1 gene associated with low circulating calcium levels. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 2007, 4, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Siomou, E.; Pavlou, M.; Papadopoulou, Z.; Vlaikou, A.M.; Chaliasos, N.; Syrrou, M. Calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphisms and idiopathic hypercalciuria in children. Pediatric Nephrol. 2017, 32, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, O.; Meng, X.W.; Xing, X.P.; Xia, W.B.; Li, M.; Xu, L.; Zhou, X.Y.; Jiao, J.; Hu, Y.Y.; Liu, H.C. Association of calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphism with serum calcium level in healthy young Han women in Beijing. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi [Chin. J. Intern. Med.] 2007, 46, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jehan, F.; Voloc, A.; Esterle, L.; Walrant-Debray, O.; Nguyen, T.M.; Garabedian, M. Growth, calcium status and vitamin D receptor (VDR) promoter genotype in European children with normal or low calcium intake. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relan, V.; Khullar, M.; Singh, S.K.; Sharma, S.K. Association of vitamin d receptor genotypes with calcium excretion in nephrolithiatic subjects in northern India. Urol. Res. 2004, 32, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Yasuda, S.; Kamata, M.; Kamata, Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Majima, M. A common polymorphism in the tissue kallikrein gene is associated with increased urinary excretions of calcium and sodium in Japanese volunteers. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 58, 758–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, F.M.; Kallay, E.; Chang, W.; Brandi, M.L.; Thakker, R.V. The calcium-sensing receptor in physiology and in calcitropic and noncalcitropic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 15, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J. The influence of genetic polymorphism. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2711s–2713s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loktionov, A. Common gene polymorphisms and nutrition: Emerging links with pathogenesis of multifactorial chronic diseases (review). J. Nutr. Biochem. 2003, 14, 426–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K.J.; Adamski, M.M.; Dordevic, A.L.; Murgia, C. Genetic Variations as Modifying Factors to Dietary Zinc Requirements-A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepulveda-Villegas, M.; Elizondo-Montemayor, L.; Trevino, V. Identification and analysis of 35 genes associated with vitamin D deficiency: A systematic review to identify genetic variants. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 196, 105516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shane, B. Folate and vitamin B12 metabolism: Overview and interaction with riboflavin, vitamin B6, and polymorphisms. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008, 29, S5–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, S.; Tieder, M.; Kohelet, D.; Liberman, O.A.; Vure, E.; Bar-Joseph, G.; Gabizon, D.; Borochowitz, Z.U.; Varon, M.; Modai, D. Vitamin D resistant rickets with alopecia: A form of end organ resistance to 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D. Clin. Endocrinol. 1981, 14, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Chapter 34-Vitamin D: Role in the Calcium and Phosphorus Economies. In Vitamin D, 3rd ed.; Feldman, D., Pike, J.W., Adams, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A.P.; Li, K.J.; Shi, H.Y.; He, J.J.; Li, H. Habitual dietary calcium intakes and calcium metabolism in healthy adults Chinese: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 25, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchowski, M.S.; Aslam, M.; Dossett, C.; Dorminy, C.; Choi, L.; Acra, S. Effect of dairy and non-dairy calcium on fecal fat excretion in lactose digester and maldigester obese adults. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjølbæk, L.; Lorenzen, J.K.; Larsen, L.H.; Astrup, A. Calcium intake and the associations with faecal fat and energy excretion, and lipid profile in a free-living population. J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 6, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M. Mechanism of Bone Mineralization. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, S.A.; Griffin, I.J.; Hawthorne, K.M.; Chen, Z.; Gunn, S.K.; Wilde, M.; Darlington, G.; Shypailo, R.J.; Ellis, K.J. Vitamin D receptor Fok1 polymorphisms affect calcium absorption, kinetics, and bone mineralization rates during puberty. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005, 20, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).