Estimation of Dietary Capsaicinoid Exposure in Korea and Assessment of Its Health Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Estimation of Capsaicinoid Intake

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

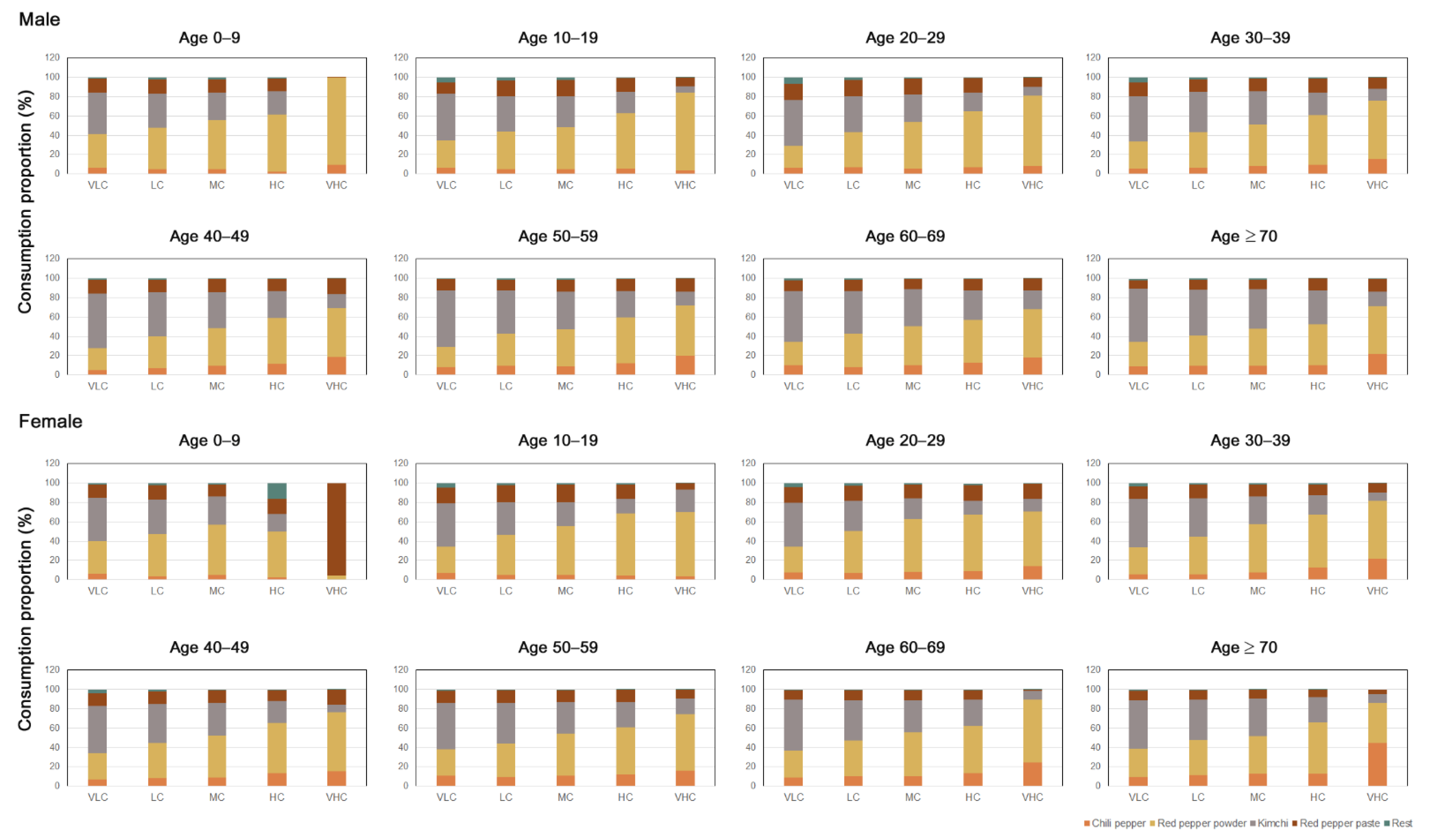

3.1. Estimation of Capsaicinoid Intake in the Korean Diet

3.2. Characteristics of the High Capsaicinoid Intake Subgroup

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbero, G.F.; Liazid, A.; Azaroual, L.; Palma, M.; Barroso, C.G. Capsaicinoid Contents in Peppers and Pepper-Related Spicy Foods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Alvarez, A.; Ramirez-Maya, E.; Alvarado-Suarez, L.A. Analysis of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin in peppers and pepper sauces by solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 2843–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zheng, J. Understand spiciness: Mechanism of TRPV1 channel activation by capsaicin. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.T.; Yi, C.H.; Lei, W.Y.; Hung, X.S.; Yu, H.C.; Chen, C.L. Influence of repeated infusion of capsaicin-contained red pepper sauce on esophageal secondary peristalsis in humans. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Kawada, T.; Iwai, K. Effect of capsaicin pretreatment on capsaicin-induced catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla in rats. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1988, 187, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujak, J.K.; Kosmala, D.; Szopa, I.M.; Majchrzak, K.; Bednarczyk, P. Inflammation, Cancer and Immunity-Implication of TRPV1 Channel. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga Ferreira, L.G.; Faria, J.V.; Dos Santos, J.P.S.; Faria, R.X. Capsaicin: TRPV1-independent mechanisms and novel therapeutic possibilities. Eur. J. Pharm. 2020, 887, 173356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Jung, D.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Patel, P.R.; Hu, X.D.; Lee, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Wang, H.F.; Tsitsilianos, N.; Shafiq, U.; et al. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 channel regulates diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance, and leptin resistance. Faseb. J. 2015, 29, 3182–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S.K.; Bliss, E.; Brown, L. Capsaicin in Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2018, 10, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, K.D.; Robertson, I.K.; Geraghty, D.P.; Ball, M.J. Effects of chili consumption on postprandial glucose, insulin, and energy metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, M.P.; Kovacs, E.M.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Effect of capsaicin on substrate oxidation and weight maintenance after modest body-weight loss in human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 90, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludy, M.J.; Moore, G.E.; Mattes, R.D. The effects of capsaicin and capsiate on energy balance: Critical review and meta-analyses of studies in humans. Chem. Senses. 2012, 37, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, S.L.; Roberts, M.D.; Kephart, W.C.; Villa, K.B.; Santos, E.N.; Olivencia, A.M.; Bennett, H.M.; Lara, M.D.; Foster, C.A.; Purpura, M.; et al. Effects of twelve weeks of capsaicinoid supplementation on body composition, appetite and self-reported caloric intake in overweight individuals. Appetite 2017, 113, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feketa, V.V.; Balasubramanian, A.; Flores, C.M.; Player, M.R.; Marrelli, S.P. Shivering and tachycardic responses to external cooling in mice are substantially suppressed by TRPV1 activation but not by TRPM8 inhibition. Am. J. Physiol. Reg. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 305, R1040–R1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ahuja, K.D.; Kunde, D.A.; Ball, M.J.; Geraghty, D.P. Effects of capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin, and curcumin on copper-induced oxidation of human serum lipids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6436–6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negulesco, J.A.; Noel, S.A.; Newman, H.A.; Naber, E.C.; Bhat, H.B.; Witiak, D.T. Effects of pure capsaicinoids (capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin) on plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations of turkey poults. Atherosclerosis 1987, 64, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, S.; Wittert, G.A.; Li, H.; Page, A.J. Involvement of TRPV1 Channels in Energy Homeostasis. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Xiong, S.; Zhu, Z. Dietary Capsaicin Protects Cardiometabolic Organs from Dysfunction. Nutrients 2016, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; St-Pierre, S.; Suzuki, M.; Tremblay, A. Effects of red pepper added to high-fat and high-carbohydrate meals on energy metabolism and substrate utilization in Japanese women. Br. J. Nutr. 1998, 80, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Kawada, T.; Kurosawa, M.; Sato, A.; Iwai, K. Adrenal sympathetic efferent nerve and catecholamine secretion excitation caused by capsaicin in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1988, 255, E23–E27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, T.; Miyawaki, C.; Ue, H.; Yuasa, T.; Miyatsuji, A.; Moritani, T. Effects of capsaicin-containing yellow curry sauce on sympathetic nervous system activity and diet-induced thermogenesis in lean and obese young women. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitam. 2000, 46, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, M.N. Capsaicin and gastric ulcers. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 275–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sareban, M.; Zugel, D.; Koehler, K.; Hartveg, P.; Zugel, M.; Schumann, U.; Steinacker, J.M.; Treff, G. Carbohydrate Intake in Form of Gel Is Associated With Increased Gastrointestinal Distress but Not With Performance Differences Compared With Liquid Carbohydrate Ingestion During Simulated Long-Distance Triathlon. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. 2016, 26, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lopez-Carrillo, L.; Hernandez Avila, M.; Dubrow, R. Chili pepper consumption and gastric cancer in Mexico: A case-control study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1994, 139, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, S.R.; Sarbu, M.I.; Matei, C.; Ilie, M.A.; Caruntu, C.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M.; Tampa, M. Capsaicin: Friend or Foe in Skin Cancer and Other Related Malignancies? Nutrients 2017, 9, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabalan, N.; Jarjanazi, H.; Ozcelik, H. The impact of capsaicin intake on risk of developing gastric cancers: A meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2014, 45, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Kwon, Y. Development of a database of capsaicinoid contents in foods commonly consumed in Korea. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4611–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kweon, S.; Kim, Y.; Jang, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Choi, S.; Chun, C.; Khang, Y.H.; Oh, K. Data resource profile: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. Estimation of curcumin intake in Korea based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2008–2012). Nutr. Res. Pract. 2014, 8, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science Major Horticulture Statistics. Available online: https://www.nihhs.go.kr/farmer/statistics/statistics.do?t_cd = 0202 (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, G.M. Relationship between red pepper intake, capsaicin threshold, nutrient intake, and anthropometric measurements in young korean women. Korean J. Nutr. 2005, 38, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, Y.S.; Kwon, H.J. Capsaicin intake estimated by urinary metabolites as biomarkers. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 66, 784–788. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Committee on Food Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on Capsaicin; European Commission Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General: Brussel, Belgium, 2002.

- Tremblay, A.; Arguin, H.; Panahi, S. Capsaicinoids: A spicy solution to the management of obesity? Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; Doucet, E.; Drapeau, V.; Dionne, I.; Tremblay, A. Combined effects of red pepper and caffeine consumption on 24 h energy balance in subjects given free access to foods. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 85, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludy, M.J.; Mattes, R.D. The effects of hedonically acceptable red pepper doses on thermogenesis and appetite. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 102, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.J.Y.; Lv, J.; Chen, W.; Li, S.X.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Yu, C.Q.; Zhou, H.Y.; Tan, Y.L.; Chen, J.S.; et al. Spicy food consumption is associated with adiposity measures among half a million Chinese people: The China Kadoorie Biobank study. Bmc. Public Health 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; Lim, K.; Kikuzato, S.; Kiyonaga, A.; Tanaka, H.; Shindo, M.; Suzuki, M. Effects of red-pepper diet on the energy metabolism in men. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitam. 1995, 41, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, P.L.; Hursel, R.; Martens, E.A.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Acute effects of capsaicin on energy expenditure and fat oxidation in negative energy balance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.A.; Spillane, M.; La Bounty, P.; Grandjean, P.W.; Leutholtz, B.; Willoughby, D.S. Capsaicin and evodiamine ingestion does not augment energy expenditure and fat oxidation at rest or after moderately-intense exercise. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeets, A.J.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. The acute effects of a lunch containing capsaicin on energy and substrate utilisation, hormones, and satiety. Eur. J. Nutr. 2009, 48, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, K.D.; Robertson, I.K.; Geraghty, D.P.; Ball, M.J. The effect of 4-week chilli supplementation on metabolic and arterial function in humans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Urbina, S.L.; Taylor, L.W.; Wilborn, C.D.; Purpura, M.; Jager, R.; Juturu, V. Capsaicinoids supplementation decreases percent body fat and fat mass: Adjustment using covariates in a post hoc analysis. BMC Obes. 2018, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroff, J.; Hume, D.J.; Pienaar, P.; Tucker, R.; Lambert, E.V.; Rae, D.E. The metabolic effects of a commercially available chicken peri-peri (African bird’s eye chilli) meal in overweight individuals. Brit. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.H.; Ma, S.T.; Wang, D.H. TRPV1 Mediates Glucose-induced Insulin Secretion Through Releasing Neuropeptides. Vivo 2019, 33, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, D.Y.; Smith, J.L.; Opekun, A.R. Spicy food and the stomach. Evaluation by videoendoscopy. JAMA 1988, 260, 3473–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Stanley, S.; Collings, K.L.; Robinson, M.; Owen, W.; Miner, P.B., Jr. The effects of capsaicin on reflux, gastric emptying and dyspepsia. Aliment. Pharm. 2000, 14, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.H.; Lei, W.Y.; Hung, J.S.; Liu, T.T.; Chen, C.L.; Pace, F. Influence of capsaicin infusion on secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10045–10052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.L.; Liu, T.T.; Yi, C.H.; Orr, W.C. Effects of capsaicin-containing red pepper sauce suspension on esophageal secondary peristalsis in humans. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 1177-e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patcharatrakul, T.; Kriengkirakul, C.; Chaiwatanarat, T.; Gonlachanvit, S. Acute Effects of Red Chili, a Natural Capsaicin Receptor Agonist, on Gastric Accommodation and Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Healthy Volunteers and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Patients. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milke, P.; Diaz, A.; Valdovinos, M.A.; Moran, S. Gastroesophageal reflux in healthy subjects induced by two different species of chilli (Capsicum annum). Dig. Dis. 2006, 24, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (BfR), G.F.I.f.R.A. Too Hot Isn’t Healthy-Foods with Very High Capsaicin Concentrations Can Damage Health; German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Carrillo, L.; Lopez-Cervantes, M.; Robles-Diaz, G.; Ramirez-Espitia, A.; Mohar-Betancourt, A.; Meneses-Garcia, A.; Lopez-Vidal, Y.; Blair, A. Capsaicin consumption, Helicobacter pylori positivity and gastric cancer in Mexico. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 106, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiatti, E.; Palli, D.; Decarli, A.; Amadori, D.; Avellini, C.; Bianchi, S.; Biserni, R.; Cipriani, F.; Cocco, P.; Giacosa, A.; et al. A case-control study of gastric cancer and diet in Italy. Int. J. Cancer 1989, 44, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buiatti, E.; Palli, D.; Bianchi, S.; Decarli, A.; Amadori, D.; Avellini, C.; Cipriani, F.; Cocco, P.; Giacosa, A.; Lorenzini, L.; et al. A case-control study of gastric cancer and diet in Italy. III. Risk patterns by histologic type. Int. J. Cancer 1991, 48, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Chang, W.K.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, S.S.; Choi, B.Y. Dietary factors and gastric cancer in Korea: A case-control study. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 97, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intake (mg/day) (1) | Intake Per Body Weight (mg/kg/day) (1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age Group | Mean ± SE | Max | Mean ± SE | Max | ||||

| Male | 0–9 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 16.19 | 3.94 ± 0.05 | 3.25 ± 0.03 (7.91 ± 0.07, 118.01) (2) | 0.036 ± 0.001 | 0.578 | 0.058 ± 0.001 | 0.052 ± 0.000 (0.127 ± 0.001, 1.933) (2) |

| 10–19 | 2.95 ± 0.14 | 47.19 | 0.050 ± 0.002 | 0.682 | |||||

| 20–29 | 3.75 ± 0.17 | 48.30 | 0.052 ± 0.003 | 0.759 | |||||

| 30–39 | 4.55 ± 0.12 | 28.56 | 0.061 ± 0.002 | 0.473 | |||||

| 40–49 | 4.80 ± 0.12 | 48.17 | 0.065 ± 0.002 | 0.641 | |||||

| 50–59 | 4.73 ± 0.12 | 44.12 | 0.069 ± 0.002 | 0.748 | |||||

| 60–69 | 4.02 ± 0.08 | 39.28 | 0.060 ± 0.001 | 0.600 | |||||

| ≥70 | 3.19 ± 0.10 | 37.21 | 0.050 ± 0.002 | 0.770 | |||||

| Female | 0–9 | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 14.24 | 2.49 ± 0.03 | 0.033 ± 0.001 | 0.412 | 0.046 ± 0.000 | ||

| 10–19 | 1.91 ± 0.06 | 14.19 | 0.039 ± 0.001 | 0.378 | |||||

| 20–29 | 2.50 ± 0.08 | 28.48 | 0.045 ± 0.001 | 0.483 | |||||

| 30–39 | 2.73 ± 0.06 | 30.58 | 0.048 ± 0.001 | 0.499 | |||||

| 40–49 | 3.09 ± 0.07 | 31.00 | 0.054 ± 0.001 | 0.454 | |||||

| 50–59 | 2.95 ± 0.06 | 36.53 | 0.052 ± 0.001 | 0.473 | |||||

| 60–69 | 2.71 ± 0.06 | 46.41 | 0.047 ± 0.001 | 0.802 | |||||

| ≥70 | 2.06 ± 0.08 | 24.71 | 0.037 ± 0.002 | 0.472 | |||||

| Capsaicinoid Intake Subgroup (1) | VLC | LC | MC | HC | VHC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption level (mg/day) | <1 | 1–3 | 3–5 | 5–12 | >12 |

| Mean ± SE (mg/day) | 0.47 ± 0.00 | 1.93 ± 0.01 | 3.87 ± 0.01 | 7.06 ± 0.03 | 17.32 ± 0.43 |

| Weighted number of participants (percentage, %) | 808,218,532 (22.1) | 1,334,884,679 (36.5) | 785,864,767 (21.5) | 652,230,874 (17.8) | 74,075,078 (2.0) |

| Male (%) | 16.3 | 32.4 | 23.6 | 24.6 | 3.0 |

| Age 0–9 | 72.3 | 22.8 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Age 10–19 | 25.1 | 40.5 | 19.4 | 13.1 | 1.9 |

| Age 20–29 | 16.7 | 35.7 | 21.5 | 23.6 | 2.5 |

| Age 30–39 | 10.3 | 31.1 | 24.0 | 30.6 | 4.0 |

| Age 40–49 | 7.0 | 28.4 | 28.9 | 31.3 | 4.4 |

| Age 50–59 | 6.4 | 30.1 | 27.5 | 31.5 | 4.5 |

| Age 60–69 | 9.6 | 33.9 | 27.9 | 26.9 | 1.7 |

| Age ≥ 70 | 14.8 | 43.5 | 25.0 | 15.2 | 1.4 |

| Female (%) | 28.6 | 41.1 | 19.1 | 10.3 | 0.9 |

| Age 0–9 | 74.2 | 22.9 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Age 10–19 | 35.6 | 44.8 | 13.9 | 5.6 | 0.2 |

| Age 20–29 | 29.4 | 39.5 | 20.3 | 9.9 | 0.8 |

| Age 30–39 | 23.2 | 41.4 | 22.3 | 12.4 | 0.7 |

| Age 40–49 | 16.8 | 43.7 | 23.0 | 14.9 | 1.6 |

| Age 50–59 | 18.2 | 43.4 | 24.5 | 12.5 | 1.3 |

| Age 60–69 | 22.9 | 43.4 | 21.3 | 11.7 | 0.8 |

| Age ≥ 70 | 35.7 | 43.7 | 12.8 | 7.1 | 0.6 |

| Probable Intake Level (1) | Upper Intake Level (2) | Maximum Intake (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicinoid consumption level (mg/day/person) | 1–5 | 12.15–29.16 | 118.01 |

| Capsaicin consumption level (4) (mg/day/person) | 0.67–3.33 | 8.10–19.44 | 78.67 |

| Percentage (%) | 58 | 18 |

| Capsaicinoid Intake Subgroup (1) | VLC | LC | MC | HC | VHC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy Intake (kcal,Mean ± SE) | ||||||

| Male | Age 0–9 | 1482 ± 17.7 a(2) | 1910 ± 40.3 b | 2654 ± 167.7 c | 2800 ± 117.1 c | 1890 ± 205.4 ab |

| Age 10–19 | 2246 ± 42.7 a | 2367 ± 47.6 a | 3016 ± 142.2 b | 3318 ± 101.2 b | 4402 ± 474.1 b | |

| Age 20–29 | 2120 ± 73.4 a | 2567 ± 66.1 b | 2785 ± 111.1 b | 3278 ± 105.7 c | 4192 ± 247.5 d | |

| Age 30–39 | 2400 ± 96.3 a | 2408 ± 47.8 a | 2853 ± 80.1 b | 3193 ± 68.6 c | 4179 ± 235.2 d | |

| Age 40–49 | 2267 ± 92.4 a | 2272 ± 40.4 a | 2597 ± 48.8 b | 2948 ± 55.4 c | 4297 ± 293.3 d | |

| Age 50–59 | 2198 ± 85.6 ab | 2175 ± 43.9 a | 2428 ± 40.7 b | 2806 ± 46.7 c | 3381 ± 131.9 d | |

| Age 60–69 | 1863 ± 49.5 a | 2050 ± 32.5 b | 2258 ± 40.1 c | 2631 ± 51.3 d | 3237 ± 219.5 d | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 1685 ± 39.0 a | 1878 ± 30.6 b | 2112 ± 35.2 c | 2368 ± 70.9 d | 2740 ± 369.9 bcd | |

| Female | Age 0–9 | 1333 ± 15.7 a | 1713 ± 38.8 b | 1982 ± 87.0 c | 2196 ± 403.1 abc | 2060 ± 0.0 c |

| Age 10–19 | 1824 ± 36.2 a | 1950 ± 33.7 a | 2257 ± 78.6 b | 2658 ± 165.2 b | 3646 ± 565.8 b | |

| Age 20–29 | 1688 ± 37.9 a | 1966 ± 53.9 b | 2399 ± 125.5 c | 2623 ± 130.4 c | 3819 ± 597.2 c | |

| Age 30–39 | 1692 ± 32.8 a | 1854 ± 26.6 b | 2046 ± 36.9 c | 2236 ± 53.6 d | 2641 ± 222.7 cd | |

| Age 40–49 | 1550 ± 38.9 a | 1749 ± 24.3 b | 1987 ± 40.5 c | 2252 ± 45.5 d | 2626 ± 172.5 d | |

| Age 50–59 | 1581 ± 48.7 a | 1699 ± 20.3 a | 1929 ± 38.8 b | 2232 ± 55.9 c | 2364 ± 204.6 bc | |

| Age 60–69 | 1495 ± 29.3 a | 1666 ± 21.9 b | 1945 ± 45.6 c | 2254 ± 67.3 d | 2097 ± 188.4 bcd | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 1326 ± 24.4 a | 1493 ± 24.0 b | 1745 ± 41.6 c | 2047 ± 119.1 cd | 2467 ± 168.0 d | |

| BMI (kg/m2, Mean ± SE) | ||||||

| Male | Age 0–9 | 16.1 ± 0.07 a* | 16.9 ± 0.16 a* | 18.0 ± 0.53 a* | 18.8 ± 1.60 a* | 16.2 ± 0.58 a* |

| Age 10–19 | 20.9 ± 0.19 a* | 21.3 ± 0.19 a* | 21.2 ± 0.30 a* | 22.5 ± 0.31 a* | 22.1 ± 0.78 a* | |

| Age 20–29 | 24.2 ± 0.26 a | 24.2 ± 0.27 a | 24.0 ± 0.28 a | 24.9 ± 0.37 a | 23.2 ± 0.78 a | |

| Age 30–39 | 25.0 ± 0.24 a | 25.2 ± 0.20 a | 25.0 ± 0.20 a | 25.1 ± 0.18 a | 25.4 ± 0.52 a | |

| Age 40–49 | 24.7 ± 0.31 a | 24.6 ± 0.15 a | 24.5 ± 0.17 a | 25.1 ± 0.17 a | 24.9 ± 0.41 a | |

| Age 50–59 | 24.0 ± 0.28 a | 24.3 ± 0.13 a | 24.7 ± 0.17 a | 24.7 ± 0.15 a | 25.0 ± 0.37 a | |

| Age 60–69 | 24.1 ± 0.22 a | 24.2 ± 0.15 a | 24.1 ± 0.14 a | 24.4 ± 0.15 a | 24.8 ± 0.45 a | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 23.4 ± 0.20 a | 23.7 ± 0.14 a | 23.6 ± 0.21 a | 23.9 ± 0.23 a | 23.9 ± 0.46 a | |

| Female | Age 0–9 | 16.6 ± 0.15 a | 17.3 ± 0.24 a | 17.6 ± 0.45 a | 15.8 ± 0.57 a | 21.3 ± 0.00 a |

| Age 10–19 | 20.2 ± 0.16 a* | 20.3 ± 0.18 a* | 21.2 ± 0.44 a* | 21.0 ± 0.53 a* | 16.9 ± 0.55 a* | |

| Age 20–29 | 21.6 ± 0.19 a | 21.8 ± 0.17 a | 21.6 ± 0.30 a | 21.7 ± 0.40 a | 21.1 ± 0.83 a | |

| Age 30–39 | 22.4 ± 0.21 a | 22.5 ± 0.15 a | 22.6 ± 0.27 a | 22.5 ± 0.27 a | 24.6 ± 1.53 a | |

| Age 40–49 | 23.0 ± 0.16 a | 23.0 ± 0.12 a | 23.3 ± 0.23 ab | 23.3 ± 0.23 ab | 25.4 ± 0.75 b | |

| Age 50–59 | 23.6 ± 0.16 a | 23.6 ± 0.16 a | 23.8 ± 0.14 a | 23.8 ± 0.21 a | 24.0 ± 0.59 a | |

| Age 60–69 | 24.3 ± 0.14 a | 24.2 ± 0.11 a | 24.1 ± 0.19 a | 25.0 ± 0.28 a | 24.1 ± 0.90 a | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 24.4 ± 0.14 a | 24.6 ± 0.15 a | 24.7 ± 0.25 a | 25.0 ± 0.36 a | 24.2 ± 0.89 a | |

| Capsaicinoid Intake Subgroup (1) | VLC | LC | MC | HC | VHC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat Intake (g, Mean ± SE) | ||||||

| Male | Age 20–29 | 59.4 ± 2.6 *(2) | 68.9 ± 2.9 * | 76.0 ± 4.5 * | 92.4 ± 6.3 * | 135.9 ± 14.3 |

| Age 30–39 | 66.1 ± 3.8 * | 61.6 ± 1.9 * | 71.7 ± 2.7 * | 80.6 ± 3.1 * | 111.4 ± 11.4 | |

| Age 40–49 | 51.1 ± 2.4 * | 52.1 ± 1.8 * | 60.9 ± 2.0 * | 66.4 ± 2.2 * | 79.6 ± 5.7 | |

| Age 50–59 | 48.2 ± 3.1 * | 45.3 ± 1.9 * | 48.6 ± 1.4 * | 59.2 ± 1.9 * | 81.8 ± 7.7 | |

| Age 60–69 | 33.8 ± 2.6 * | 36.2 ± 1.0 * | 40.2 ± 1.4 * | 46.7 ± 1.6 | 72.0 ± 14.7 | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 26.9 ± 1.3 | 30.2 ± 1.0 | 34.2 ± 1.5 | 38.7 ± 2.3 | 62.7 ± 21.6 | |

| Female | Age 20–29 | 49.2 ± 1.8 * | 55.7 ± 2.3 * | 67.8 ± 5.0 * | 72.4 ± 5.9 * | 143.7 ± 31.5 |

| Age 30–39 | 45.5 ± 1.4 * | 47.1 ± 1.1 * | 50.4 ± 1.6 * | 56.3 ± 1.8 | 85.4 ± 15.5 | |

| Age 40–49 | 38.2 ± 1.5 * | 41.0 ± 0.9 * | 46.6 ± 1.6 * | 58.2 ± 2.4 * | 82.3 ± 11.3 | |

| Age 50–59 | 36.0 ± 2.0 | 35.7 ± 0.8 | 38.1 ± 1.0 | 45.4 ± 1.6 | 49.7 ± 8.6 | |

| Age 60–69 | 27.5 ± 0.9 | 30.4 ± 0.8 | 35.3 ± 1.2 | 44.0 ± 2.3 | 44.2 ± 9.1 | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 19.6 ± 0.7 | 23.3 ± 1.0 | 28.4 ± 1.4 | 32.7 ± 3.1 | 35.1 ± 9.1 | |

| Sugar intake (g, Mean ± SE) | ||||||

| Male | Age 20–29 | 67.5 ± 5.4 * | 72.8 ± 3.8 * | 83.6 ± 8.6 | 88.5 ± 4.9 | 117.1 ± 17.6 |

| Age 30–39 | 81.5 ± 5.9 | 69.2 ± 3.0 * | 72.6 ± 3.6 * | 83.6 ± 3.9 | 114.6 ± 21.1 | |

| Age 40–49 | 60.5 ± 3.9 * | 64.0 ± 2.7 * | 67.1 ± 2.9 * | 71.7 ± 2.7 * | 124.9 ± 15.0 | |

| Age 50–59 | 70.1 ± 6.5 | 62.1 ± 2.5 * | 65.7 ± 2.7 * | 70.6 ± 2.6 * | 88.3 ± 7.2 | |

| Age 60–69 | 56.4 ± 3.9 * | 58.0 ± 2.1 * | 63.3 ± 2.4 * | 76.1 ± 4.0 | 117.2 ± 26.5 | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 44.6 ± 3.1 * | 47.1 ± 2.1 * | 63.3 ± 3.6 | 63.9 ± 4.1 | 79.8 ± 14.5 | |

| Female | Age 20–29 | 59.6 ± 3.1 | 61.3 ± 2.8 | 79.1 ± 5.9 | 80.2 ± 8.1 | 94.1 ± 17.6 |

| Age 30–39 | 57.1 ± 2.0 | 59.4 ± 2.0 | 61.5 ± 2.8 | 67.2 ± 3.4 | 73.1 ± 10.9 | |

| Age 40–49 | 58.3 ± 3.0 * | 57.6 ± 1.7 * | 62.0 ± 2.4 * | 72.5 ± 3.8 | 81.3 ± 6.3 | |

| Age 50–59 | 60.5 ± 2.2 | 64.3 ± 2.0 | 69.1 ± 2.6 | 81.5 ± 5.1 | 57.0 ± 8.2 | |

| Age 60–69 | 54.7 ± 2.4 | 56.3 ± 1.9 | 73.0 ± 5.7 | 70.5 ± 4.0 | 107.1 ± 44.8 | |

| Age ≥ 70 | 45.6 ± 2.3 * | 46.8 ± 2.3 * | 49.0 ± 3.7 * | 79.8 ± 15.1 | 76.6 ± 7.4 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, Y. Estimation of Dietary Capsaicinoid Exposure in Korea and Assessment of Its Health Effects. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072461

Kwon Y. Estimation of Dietary Capsaicinoid Exposure in Korea and Assessment of Its Health Effects. Nutrients. 2021; 13(7):2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072461

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Youngjoo. 2021. "Estimation of Dietary Capsaicinoid Exposure in Korea and Assessment of Its Health Effects" Nutrients 13, no. 7: 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072461

APA StyleKwon, Y. (2021). Estimation of Dietary Capsaicinoid Exposure in Korea and Assessment of Its Health Effects. Nutrients, 13(7), 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072461