Abstract

Omega-3 fatty acids, specifically eicosapentanoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and docosahexanoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) are receiving increasing attention in sports nutrition. While the usual focus is that of athletes, questions remain if the different training status between athletes and amateurs influences the response to EPA/DHA, and as to whether amateurs would benefit from EPA/DHA supplementation. We critically examine the efficacy of EPA/DHA on performance, recovery and injury/reduced risk of illness in athletes as well as amateurs. Relevant studies conducted in amateurs will not only broaden the body of evidence but shed more light on the effects of EPA/DHA in professionally trained vs. amateur populations. Overall, studies of EPA/DHA supplementation in sport performance are few and research designs rather diverse. Several studies suggest a potentially beneficial effect of EPA/DHA on performance by improved endurance capacity and delayed onset of muscle soreness, as well as on markers related to enhanced recovery and immune modulation. The majority of these studies are conducted in amateurs. While the evidence seems to broadly support beneficial effects of EPA/DHA supplementation for athletes and more so in amateurs, strong conclusions and clear recommendations about the use of EPA/DHA supplementation are currently hampered by inconsistent translation into clinical endpoints.

1. Introduction

The main purpose of nutrition for athletes is to compensate for increased energy and nutrient needs. In recent years, the role of omega-3 fatty acids in sport has received increasing research attention []. Omega-3 fatty acids are perceived as a potential supplement that may beneficially affect performance, recovery and the risk for illness/injury []. Omega-3 fatty acids belong to the family of polyunsaturated fatty acids []. While there are fatty acids of varying length, the most important ones are considered to be the very long-chain fatty acids eicosapentanoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and docosahexanoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) []. The predominant source for EPA/DHA is seafood, particularly fatty fish, such as mackerel and herring. Although food items such as linseed oil and walnut oil have high amounts of the plant-derived omega-3 fatty acid α-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3n-3) they are not routinely consumed in large quantities. Other food products, such as soybeans, squash and wheat germ cereals contain less ALA but are often consumed in higher amounts and therefore contribute significantly to ALA intake. While EPA can be synthesized from ALA, the conversion of ALA to EPA and further to DHA is characterized by a low conversion rate [], therefore the consumption of EPA/DHA via seafood is generally recommended. Although the current recommendations stand, it should be noted that there is a substantial genetic variation in the fatty acid metabolism [].

In the European Union (EU), across all populations, EPA and DHA intake is not adequate; in 74% of the EU countries the intake was found to be lower than the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) recommendation of 250 mg for EPA and DHA as adequate intake for adults based on cardiovascular considerations [,]. The current dietary guidelines for Americans suggest the same value []. EPA/DHA are considered safe up to 5 g per day []. Although EFSA’s recommendation is for the normal, healthy population, it is reasonable to assume that neither athletes nor amateurs consume adequate amounts either considering their higher energy turnover and metabolic flux. In fact, analyses of dietary habits in various athletes found that substantial proportions of the studied populations did not reach the dietary goals for macro- and micronutrients, including EPA/DHA [,]. Furthermore, a recent multi-center, cross-sectional study in 404 National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I football athletes revealed that no athlete had an Omega-3 Index associated with low risk [].

While there are some data that EPA/DHA may improve endurance capacity and promote recovery in athletic populations [], current evidence lacks consensus []. Given the fact that a lot of studies with omega-3 fatty acids were conducted in non-professionals, we also include studies conducted in amateurs (defined as people pursuing an activity for pleasure without payment and not as a job). Broadening the data base may shed more light on the effects of EPA/DHA supplementation on performance parameters. Furthermore, this large section of the population is also of interest as it can potentially benefit from an optimized diet as well. Studies were included when parameters relevant for performance, recovery and risk of illness/injury were reported. Hence, this narrative review identifies relevant human intervention studies and evaluates the overall impact of EPA/DHA in sport nutrition for athletes as well as amateurs. The scope of this review is to provide a simplified and exploratory, yet relevant approach to assess the role of EPA/DHA on outcomes related to performance, recovery and illness/injury in two different populations, athletic as well as amateurs, by using dichotomous splits to describe the study outcomes focusing on study duration and dose. The differentiation between athletes and amateurs is important, because the metabolic state, i.e., training status may well influence the response to a given stimulus or supplementation. In general, varying designs particularly in the dose of EPA/DHA as well as the duration of supplementation contribute substantially to the partly inconsistent outcomes. Our approach enabled us to identify differences in outcomes related to dose and duration between athletes and amateurs, which may translate not only into tailored intake recommendations but into design considerations for future clinical trials to assess the efficacy of EPA/DHA supplementation in performance.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a narrative literature review and search using the PubMed database with predefined keywords, as well as MeSH terms. The literature search was finalized in March 2020. The search strategy included the terms: (omega-3 fatty acids OR n-3 fatty acids OR fish oil) AND (sport OR sports OR performance). The selection criteria were randomized controlled clinical trials that were published between January 2010 and February 2020. The search was limited to humans, and the English language. Initially, 310 articles were retrieved. After screening of titles and abstracts, 52 papers were selected for further examination. In addition, 1 article was identified by subsequent hand search, so that 53 articles reporting on randomized controlled trials over the last decade in both athletes as well as amateurs were included in this narrative review. We wanted to explore whether the dose or duration of the supplementation was influencing the findings. However, these factors were not normally distributed across the studies so we decided to adopt a simple dichotomized approach to enable us to compare the highest against the lowest for both dose and duration [].

3. Results

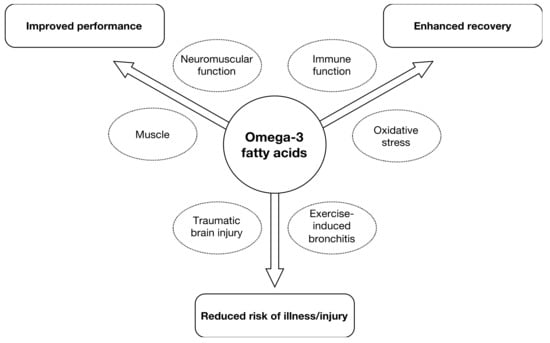

EPA and DHA can affect many aspects of human physiology/metabolism and these can subsequently impact outcomes related to sporting performance, recovery and illness/injury is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Areas of interest for supplementation with eicosapentanoic acid/docosahexanoic acid (EPA/DHA) in sport nutrition in athletes as well as amateurs.

Of all the studies that were identified for this review, multiple outcomes were often reported within each study, which in some cases made allocation to only one of the main topics a challenge (performance, recovery or illness/injury). Hence the allocation of studies to performance, recovery or illness was based on evaluation of the main outcome reported. Overall, of the 53 articles, 21 articles reported on athletes and 32 in amateurs.

3.1. The Influence of Dose and Study Duration in Athletes and Amateurs on Performance

Thirty studies were identified that assessed the effects of EPA/DHA supplementation with a focus on performance-related outcomes in athletes and amateurs (Table 1). One study was used twice because of 2 sets of data (low dose and high dose groups). Ten of those studies were conducted in athletes, with 21 in amateurs. The amounts used in the studies reviewed here vary for EPA from 0.06 g to 4.9 g per day and for DHA from 0.04 to 4.7 g DHA per day. The duration of supplementation ranged from acute to 24 weeks.

Table 1.

Effects of EPA/DHA supplementation with a focus on performance-related outcomes in athletes and amateurs.

A recent study in 26 competitive soccer players supplemented with 4.9 g EPA and 1.4 g DHA per day over 4 weeks found that the increases in leg strength, sprint speed, explosive power and anaerobic endurance were not different between groups []. No benefits of supplementation with 0.56 g EPA and 0.14 g DHA over 8 weeks were found on power output and MVC in a group of trained males []. In contrast, explosive power, fatigue and muscle soreness were improved in athletes consuming 1.1 g of each EPA and DHA over 5 weeks []. Similarly, in a study with trained males, squat jump performance was improved after a single acute supplementation with 0.75 g EPA and 0.05 g DHA []. A greater number of studies have been conducted in amateurs. Muscle strength was increased in long-term supplementation studies with 0.4 g EPA and 0.3 g DHA over 21 weeks, or 1.86 g EPA and 1.5 g DHA over 24 weeks [,]. Mixed results were reported from studies in amateur males with 0.375 g EPA and 0.51 g DHA [,] where the latter reported no benefits on strength but improved fatigue. A short-term supplementation with 2 g EPA and 1 g DHA over one week did not demonstrate any effects on arm circumference or volume []. No improvement in strength was found in amateur males and females after 4 weeks of 2.7 g fish oil []. Muscle protein synthesis, was unchanged after 3.5 g EPA and 0.9 g DHA over 8 weeks [].

Anaerobic endurance improved after supplementation with 4.9 g EPA and 1.4 g DHA over 4 weeks in a group of soccer players []. Others reported beneficial results in male athletes in various parameters relevant for endurance such as submaximal exercise HR and O2 consumption VO2max and relative O2 consumption [,] (Table 1). Others found diastolic blood pressure and HR during submaximal exercise decreased in athletes, supplemented with 1.9 g EPA/DHA, but these changes did not translate in delayed time to exhaustion during a run, nor to enhanced recovery []. While the above changes could result in enhanced performance, the time to voluntary fatigue was not different between groups in a comparable study []. Nor did athletes exercising during a 1-h time trial [] or a 10-km time trial [] show a beneficial effect of supplementation with EPA/DHA. In amateur males, no effects on cardiac output at rest or during an exercise stress test were found after acute supplementation with either 4.7 g EPA or 4.7 g DHA, but systemic vascular resistance was reduced following DHA supplementation only []. An earlier study found neither substrate oxidation, energy expenditure nor energy efficiency to be affected by 2-week supplementation with 1.1 g EPA and 0.7 g DHA in amateurs []. However, a study in amateurs in which EPA/DHA were administered in doses of 0.6 g and 0.3 over 8 weeks, led to a significant increased VO2max []. An improved O2 uptake during submaximal exercise in amateurs after supplementation with 0.9 g EPA and 0.4 g DHA was confirmed by others [,]. The latter study was based on cardiovascular parameters in response to submaximal exercise with amateur overweight adults []. Similarly, amateurs who had received 0.8 g EPA and 2.4 g DHA over 8 weeks showed significantly lower heart rates during incremental work load up to exhaustion, lowered steady-state submaximal exercise heart rates and increased whole body O2 consumption []. Also smaller amounts (0.56 g DHA and 0.14 g EPA) tended to reduce mean exercise HR and improved HR recovery in amateurs []. The influence of study duration on performance-related outcomes is depicted in Figure 2.

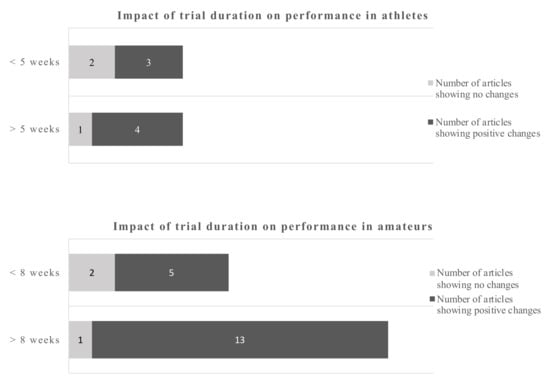

Figure 2.

Impact of trial duration on performance-related outcomes in athletes and amateurs by dichotomous split.

Using a cut-off of 5 weeks for athletes and 8 weeks for amateurs gives a dichotomous split. The evidence favors longer trials which is more pronounced in amateurs.

Using a dichotomous split for each, athletes and amateurs, the cut-off points were 5 weeks and 8 weeks respectively. For athletes, 4 out of 5 studies and 13 out of 14 studies in amateurs, favored the longer duration studies in terms of providing positive performance outcomes (Figure 3).

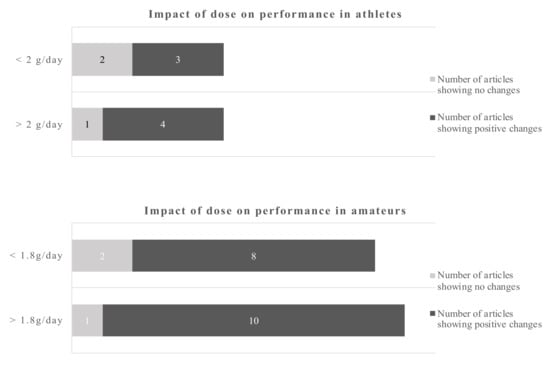

Figure 3.

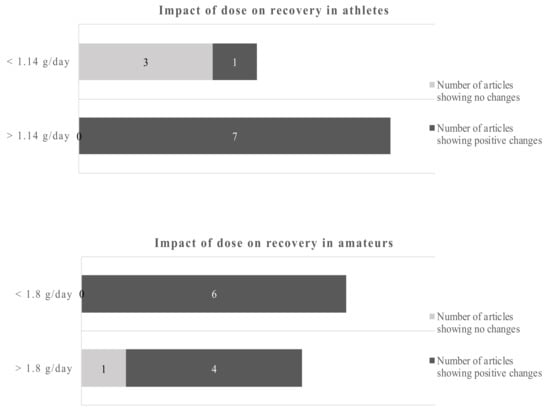

Impact of dose on recovery-related outcomes in athletes and amateurs by dichotomous split.

Using a cut-off of 2 d/day for athletes and 1.8 g/day for amateurs gives a dichotomous split. The evidence favors the higher doses which is more pronounced in amateurs. However, even the lower dose gives more positive changes as opposite to the low dose in athletes.

The data in amateurs were more pronounced. The cut-off points for the dose were 2 g/day for athletes and 1.8 g/day for amateurs. The data suggest that doses below 2 g/day in athletes sometimes induce a beneficial outcome, while above that cut-off point 4 out of 5 studies showed beneficial outcomes. The dose in amateurs appear to be of less influence, as 18 out of 21 studies reported a beneficial outcome regardless whether above or below the cut-off point.

3.2. The Influence of Dose and Study Duration in Athletes and Amateurs on Recovery

Twenty-two studies were identified that assessed the effects of EPA/DHA supplementation with a focus on recovery-related outcomes in athletes and amateurs Table 2.

Table 2.

Effects of EPA/DHA supplementation with a focus on recovery-related outcomes in athletes and amateurs.

Eleven of those studies were conducted in athletes, 11 in amateurs. The amounts used in the studies reviewed here varied for EPA from 0.06 g to 2.4 g per day and for DHA from 0.04 to 1.2 g DHA per day. The duration of supplementation ranged from acute to 24 weeks (Table 2).

A recent study in 30 male athletes found that 6 weeks of supplementation with 0.55 g EPA and 0.55 g DHA reduced muscle soreness after eccentric exercise, without an effect on muscle function []. Reduced soreness in amateurs due to supplementation with EPA/DHA has been consistently reported [,,]. Soreness following eccentric exercise was also reported less in amateurs who received 3 g of DHA for a little more than a week []. Furthermore, delayed onset of muscle soreness was also reported after 8 weeks of 0.6 g EPA and 0.26 g DHA [], or 4 weeks of 2.7 g of fish oil []. An intervention study in 27 amateur males showed no effect of 1.8 g/d omega-3 fatty acids on knee ROM, perceived pain, and thigh circumference when measured immediately, and after 24 h of eccentric exercise []. However, perceived pain and ROM were improved at 48 h post-exercise. In contrast, participants who were able to achieve full elbow extension improved after 1 week of supplementation with 3 g DHA, while passive extension or arm swelling were not []. Others found a trend for reduced soreness after eccentric exercise in amateur females [].

In young, but not older athletes, pro-inflammatory gene expression in response to exercise were increased following 5 weeks supplementation with 0.83 g DHA, in combination with alpha-tocopherol []. In contrast, decreased inflammatory responses following intense exercise were reported in a group of athletes that received doses of 1.2 g EPA and 2.4 g DHA []. Partially beneficial results were reported after 1.16 g DHA for 8 weeks by exerting anti-inflammatory effects via increasing plasma PGE2 []. Furthermore, exercise-induced increases in various cytokines, including interleukin 6 and 8, were decreased following supplementation with 1.16 g DHA for 8 weeks [], while one study found interleukin 4 and 6 remained unaffected in amateurs that received 1.3 g EPA and 0.3 g DHA for 6 weeks [].

In athletes, improved antioxidant capabilities in response to acute exercise were reported after supplementation with 1.14 g of DHA over 8 weeks []. A slightly higher dose of DHA over a longer period of time decreased exercise-induced peroxidative damage []. However, using the same supplementation protocol, the authors showed increased markers of oxidative damage during training []. Potentially aggravating effects were also reported in athletes with increased oxidative stress at rest and after training following the consumption of 0.6 g EPA and 0.4 g DHA []. In a further study, 0.82 g of DHA in combination with 0.33 g alpha-tocopherol showed neither an effect on oxidative damage following a maximal exercise test nor changes in the antioxidant gene expression []. In amateurs, 1.3 g EPA and 0.3 g DHA reduced certain markers of oxidative stress after a single bout of exercise, while other parameters, including endogenous DNA damage and muscle soreness, were unaffected []. Regarding study duration the cut-off points were 8 weeks for athletes and 6 weeks for amateurs (Figure 4).

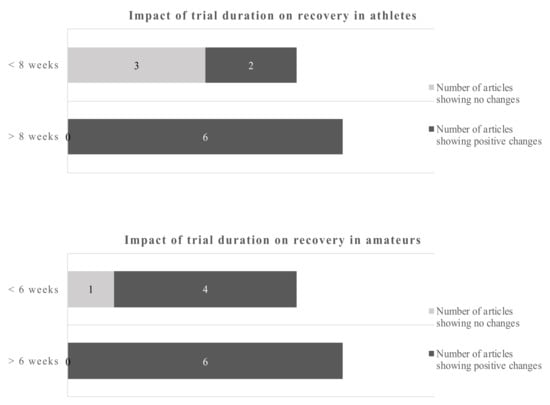

Figure 4.

Impact of trial duration on recovery in athletes and amateurs by dichotomous split.

Using a cut-off of 8 weeks for athletes and 6 weeks for amateurs gives a dichotomous split. The evidence favors longer trials in athletes and amateurs.

Studies of less than 8 weeks duration in athletes showed no clear picture of the benefits of omega-3 fatty acids, only 2 out of 5 studies reported beneficial outcomes. However, 6 out of 6 studies with more than 8 weeks reported positive changes due to the EPA/DHA supplementations. Studies in amateurs showed positive changes of the omega-3 fatty acids in 4 out of 5 studies below 6 weeks of duration and 6 out of 6 studies of more than 6 weeks duration. Applying the dichotomous approach on the dose, the observed cut-off points for athletes and amateurs were 1.14 g/day and 1.8 g/day, respectively. One out of 4 studies reported beneficial effects of the EPA/DHA supplementation in athletes when the supplementation was lower than 1.14 g/day. However, all studies with a dose above 1.14 g/day showed beneficial effects. In amateurs, 10 out of 11 studies showed beneficial effects of EPA/DHA supplementation on recovery-related outcomes (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Impact of dose on recovery in athletes and amateurs by dichotomous split.

Using a cut-off of 1.14 g/day for athletes and 1.8 g/day for amateurs gives a dichotomous split. Overall, the data are clearer for amateurs. The evidence favors higher doses in athletes and amateurs.

Overall, the evidence shows that EPA/DHA have the potential to decrease the production of inflammatory eicosanoids, cytokines, and ROS. Amateurs appear to benefit more; particularly soreness is beneficially affected by supplementation with EPA/DHA (Table 2).

3.3. Reduced Risk of Injury/Illness

Four studies were identified that assessed the effects of EPA/DHA on injury/illness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of EPA/DHA supplementation with a focus on injury/illness-related outcomes in athletes and amateurs.

Two of those studies report on athletes and two on amateurs. A study in trained males showed similar improvements in markers of pulmonary function, albeit with a much higher dose of up to 3.7 g EPA and 2.5 g DHA over 3 weeks []. Improved markers for pulmonary function, including hyperpnea-induced bronchoconstriction, a surrogate for exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB), were also observed after 3 weeks of a low daily dose of 0.07 g EPA and 0.05 g DHA during an eucapnic hyperventilation challenge in amateurs [], with EPA/DHA possibly acting as an inflammatory antagonist. In contrast, no changes in inflammatory markers were found in a study in amateur males and females with a high dose of 4 g EPA and 2 g DHA over 3 weeks [].

Evidence from observational and intervention studies suggests a beneficial effect of EPA/DHA in asthma in the general population [,,]. An early intervention study in athletes showed that fish oil supplementation reduced exercised-induced bronchoconstriction []. In professional football players, a small to moderate neuroprotective effect of 2 g DHA per day over the course of an American football season was reported [].

4. Discussion

The evidence presented in the studies reviewed here show that EPA/DHA may have the potential to influence not only the metabolic response of muscle to nutrition, but also the physiological functional response to exercise and post-exercise conditions. However, these physiological and metabolic adaptations do not always translate into improved performance.

Based on the review of the literature presented here, there seem to be bigger gains for amateurs. It is possible that there is a genuine difference, that amateurs have more to gain from EPA/DHA supplementation, but it could be due to the higher metabolic flux in athletes meaning they require more EPA/DHA to see the benefits (either in terms of dosage or supplementation duration). Alternatively, it could be the case that studies tend to be longer in the amateur groups (from experience, amateurs are more willing to keep training constantly for longer than athletes), so the positive performance gains are more likely to develop in the longer studies more often seen in amateurs. It should also be acknowledged that the potential for performance gains is narrower in athletes due to the law of diminishing returns.

4.1. Increased Performance

It is known that the response of skeletal muscle to exercise can be influenced by the nutritional status of the muscle []. This effect is not confined to macronutrients, but EPA/DHA can also potentially influence the exercise and nutritional response of skeletal muscle [], this in turn can partly explain the observed decrease in soreness. Although the potential for EPA/DHA supplementation to improve muscle mass or function, is supported by mechanistic explanations including structural changes of the muscle cell membranes [,] this review found no consistent effect on strength in amateurs. Muscle protein synthesis, a fundamental process in muscle growth, was unchanged after 3.5 g EPA and 0.9 g DHA over 8 weeks, although muscle biopsies revealed that kinase signaling in response to resistance training was altered []. However, it has been shown that incorporation of EPA/DHA in muscle cells stimulates foal adhesion kinase, which regulates MPS [], and may actually have a beneficial effect on muscle protein synthesis. This was shown in amateur females and males in response to anabolic stimuli, in two 8-week intervention studies with 1.86 g EPA and 1.5 g DHA [,]. Interestingly, selective improvement in muscle torque and muscle quality after, but not during, exercise was reported in females only []. EPA and DHA seemed to optimize the effects of resistance training in amateur elderly females, including dynamic and explosive strength, however these effects did not result in an overall improvement of isometric strength performance []. These data corroborate other reports that possibly older adult populations may benefit from EPA/DHA supplementation in the context of preserving muscle mass in an older population [].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator (PGC-1a) is a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. In obese participants, EPA has been shown to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis [], which could result in improved endurance regulated via the PGC-1a pathway. It can be hypothesized that lower heart rates and improved O2 uptake may lead to better O2 delivery to contracting muscles, thereby enhancing endurance performance []. Another mechanism for improved endurance could be that EPA/DHA increase the deformability of RBC, which in turn could increase oxygen delivery to the muscles []. It has also been shown that exposure of human myotubes to EPA upregulated specific genes that regulate beta-oxidation []. Moreover, clinical evidence suggests that EPA/DHA increase fatty acid oxidation via the carnitine palmitoyltransferase-II [,]. These mechanisms may well have contributed to the increased fat oxidation during rest by 19% and during exercise by 27% following supplementation of 3 g/day EPA/DHA over 12 weeks in female adults [].

4.2. Enhanced Recovery

The concept of muscle damage following intense eccentric exercise is accepted []. The acute exercise recovery period is defined as the initial 96 h following exercise []. EPA and DHA have been described to increase the structural integrity of muscle cell membranes [], which in turn may explain the protective effect of EPA/DHA. This has recently been demonstrated in soccer players where 1.1 g/day EPA/DHA combined with 30 g/day whey protein resulted in reduced levels of muscle soreness along with a reduction of plasma CK concentration []. Furthermore, exercise-induced muscle damage causes responses that include DOMS and muscle fatigue. It also leads to increased circulating neutrophils and interleukin-1 peaking within 24 h after the exercise, with skeletal muscle levels remaining elevated for 48 h and longer []. Inflammation is a key process in muscular repair and regeneration, the potential of EPA/DHA to accelerate the recovery process via immune modulation come into play. EPA/DHA influence immune modulation via increasing interleukin 2 (IL2) [,], where an acute dose of fish oil improved markers of inflammation after eccentric exercise in amateur males []. The authors found that in 45 amateur males an acute dose of 1.8 g fish oil before a single eccentric exercise bout lead to a smaller exercise-induced elevation in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and prostaglandin (PG)E2 immediately, 24 h, and 48 h after exercise, as well as significantly lower elevation in the concentrations of interleukin 6 (IL-6), CK, and myoglobin (Mb) at 24 and 48 h after exercise.

Furthermore, in theory EPA/DHA may contribute to insulin-sensitizing effects because EPA and DHA are natural ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ); following activation of PPARγ, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activity is suppressed, reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines []. At a cellular level, fatty acids have an important function in regulating the activity of certain enzymes and by acting as signaling molecules []. It has been shown that 1.3 g fish oil consumption over 6 weeks has the potential to ameliorate the exercise-induced decrease in superoxide dismutase activity in sedentary control participants []. In the same study, fish oil tended to increase the catalase activity after 1 h of recovery. Together, these findings suggest that EPA/DHA may activate the superoxide dismutase and catalase pathways. Oxidative stress is usually defined by an increased formation of prooxidants and decrease of antioxidants. This disturbance can lead to oxidative damage to cellular components such as lipids, protein and DNA. However, oxidative stress and inflammation are interdependent. Inflammation can develop following oxidative stress, on the other hand inflammation can induce oxidative stress which further enhances inflammation []. Exercise mode, intensity, and duration, as well as the subject population tested, can impact the extent of oxidative stress. Furthermore, the use of antioxidant supplements such as EPA/DHA can impact the outcomes. EPA and DHA have been shown to improve muscle function in older adults [,]. A recent paper supports the view that EPA/DHA could bring benefits by attenuating the generation of oxidative stress []. In this review, preliminary evidence is provided that EPA/DHA may be beneficial in counteracting exercise-induced inflammation. However, current data are inconclusive as to whether EPA/DHA supplementation at the reported dosages is effective in attenuating the immune-modulatory response to exercise and ultimately improve recovery.

4.3. Reduced Risk of Injury/Illness

Optimal sports performance requires optimal health. EIB is a prominent asthma phenotype affecting an estimated 90% of asthma patients and up to 50% of elite athletes []. Reduced inflammation ameliorates the severity of asthma and exerts a bronchodilatory effect. The anti-inflammatory effects of EPA/DHA may be linked to a change in cell membrane composition and lipid mediators such as resolvins []. Alternatively, the effect may also be mediated by the decreased production of bronchoconstrictive leukotrienes [].

Certain sports like soccer or rugby can lead to traumatic brain injuries (TBI). As outlined by others, the number of sport-related concussions are increasing globally []. Although DHA and EPA have shown promising in vitro and animal evidence of neuronal repair capacities in TBI [], there has been only one large, controlled intervention study conducted in American football players. The underlying mechanisms for this observation have not been completely elucidated but it is suggested that saturation of brain cells with DHA in particular may facilitate healing after brain trauma, thereby counteracting negative long-term results []. Other mechanisms by which specifically DHA could convey neuroprotection include preservation of myelin, alleviation of glutamate cytotoxicity, suppression of mitochondrial dysfunction and down-regulation of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5- methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor sub- units. Details are discussed elsewhere [].

This review provides a new angle on the evidence linking EPA/DHA with performance and recovery-related outcomes by analyzing basics in study designs in the context of the training status. The limitations of this analysis include its exploratory nature. The background diet is hardly considered in the studies that were analyzed; therefore, a fundamental confounder cannot be included in this analysis. Other aspects like the sex of study participants were not considered, due to the limited number of studies. Also, the questions of responders vs. non-responders remains unanswered, and all of these aspects need to be addressed in future clinical trials. It cannot be highlighted enough to pay utmost attention to the actual dose and duration when designing clinical trials. Dichotomization is often used in statistical applications to identify thresholds of continuous variables. A recent simulation study suggests that common methods of dichotomization theoretically discover the true threshold [] albeit with higher numbers of subjects than we had in our review. For the purpose of this review we did not apply subsequent statistical tests but confined ourselves to a descriptive use of dichotomization.

5. Conclusions

This review identified evidence to support a role of EPA/DHA in improved performance such as enhanced endurance, markers of functional response to exercise, enhanced recovery or neuroprotection. The majority of evidence stems from studies in amateurs rather than athletes, although most recommendations for EPA/DHA supplementation for improved performance are made for athletes. In practical terms, athletes, and likely more so, amateurs may benefit from the consumption/supplementation of EPA/DHA. The extent to which the different metabolic state, i.e., training status influences the response to the supplementations warrants further research. In general terms there seems to be an effect of supplementation duration, with favorable outcomes appearing more consistently after approximately 6–8 weeks. The same is true for EPA/DHA dosage, with better responses from doses above approximately 1.5–2.0 g/day. Finally, it appears the beneficial outcomes are more consistently seen in amateurs, so broadly speaking the amateurs might require lower doses for a shorter period to experience gains.

It remains to be investigated why the changes in markers do not always lead to measurable improvements in clinical outcomes of performance, recovery and the reduced risk of illness/injury. In a given, well-characterized population the quantity of EPA/DHA and the duration of the supplementation play crucial roles and need to be well defined in order to clearly identify the effects of EPA/DHA on performance. Also, certain questions remain to be investigated such as sex, responders vs. non-responders, or if the habitual intake of EPA/DHA play a role in the efficacy of EPA/DHA for sports nutrition. This exploratory analysis may, therefore, serve as guidance for the basic design of clinical trials that investigate effects of EPA and DHA and avoid pitfalls of study durations that are too short, optimal dose and most importantly the appropriate study population, as training status seems to be a substantial aspect in determining the effects of EPA/DHA supplementation in sports nutrition.

Given that EPA/DHA are considered safe up to 5 g per day there seems little harm in recommending EPA/DHA, even when further larger studies with optimal design are needed to confirm these initial results.

Author Contributions

F.T. conceived the idea for the paper. F.T. and A.B. collected and analyzed the data. F.T. and A.B. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received unconditional funding from Doetsch Grether AG for conducting the literature search and writing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

F.T. works as lecturer at the Swiss Distance University of Applied Sciences and as independent science consultant. A.B. is employed at the School of Sports at the University of Birmingham, UK. The authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to the context of this review. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Da Boit, M.; Hunter, A.M.; Gray, S.R. Fit with good fat? The role of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on exercise performance. Metabolism 2017, 66, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simopoulos, A.P. Omega-3 fatty acids and athletics. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2007, 6, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burdge, G.C.; Calder, P.C. Introduction to fatty acids and lipids. World Rev. Nutr. Diet 2015, 112, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Very long-chain n-3 fatty acids and human health: Fact, fiction and the future. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arterburn, L.M.; Hall, E.B.; Oken, H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1467S–1476S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, A.; Enroth, S.; Johansson, A.; Zaboli, G.; Igl, W.; Johansson, A.C.; Rivas, M.A.; Daly, M.J.; Schmitz, G.; Hicks, A.A.; et al. Genetic adaptation of fatty-acid metabolism: A human-specific haplotype increasing the biosynthesis of long-chain omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioen, I.; van Lieshout, L.; Eilander, A.; Fleith, M.; Lohner, S.; Szommer, A.; Petisca, C.; Eussen, S.; Forsyth, S.; Calder, P.C.; et al. Systematic Review on N-3 and N-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intake in European Countries in Light of the Current Recommendations - Focus on Specific Population Groups. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 70, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture U.D.o.H.a.H.S.a.U.D.o. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Tolerable Upper Intake Level of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA). EFSA J. 2012, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskas, M.; Stukas, R.; Tubelis, L.; Zagminas, K.; Surkiene, G.; Svedas, E.; Giedraitis, V.R.; Dobrovolskij, V.; Abaravicius, J.A. Nutritional habits among high-performance endurance athletes. Medicina (Kaunas) 2015, 51, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schacky, C.; Kemper, M.; Haslbauer, R.; Halle, M. Low Omega-3 Index in 106 German elite winter endurance athletes: A pilot study. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.; Carbuhn, A.; Jones, L.; Gallop, A.; Smith, A.; Johnson, P.; Swearingen, L.; Moore, C.; Rimer, E.; McBeth, J.; et al. The Omega-3 Index in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Collegiate Football Athletes. J. Athletic Train. 2019, 54, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpott, J.D.; Witard, O.C.; Galloway, S.D.R. Applications of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for sport performance. Res. Sports Med. 2019, 27, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. The cost of dichotomization. Appl. Psychol.l Measur. 1983, 7, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, G.E.; McLennan, P.L.; Howe, P.R.; Groeller, H. Fish oil reduces heart rate and oxygen consumption during exercise. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2008, 52, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieman, D.C.; Henson, D.A.; McAnulty, S.R.; Jin, F.; Maxwell, K.R. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids do not alter immune and inflammation measures in endurance athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2009, 19, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K.E.; Witard, O.C.; Baker, D.; Healey, P.; Lewis, V.; Tavares, F.; Christensen, S.; Pease, T.; Smith, B. Adding omega-3 fatty acids to a protein-based supplement during pre-season training results in reduced muscle soreness and the better maintenance of explosive power in professional Rugby Union players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 18, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.D.; Burgess, S.; Murphy, K.J.; Howe, P.R. DHA-rich fish oil lowers heart rate during submaximal exercise in elite Australian Rules footballers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, L.; Brown, F.F.; Alexander, L.; Dick, J.; Bell, G.; Witard, O.C.; Galloway, S.D.R. n-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation During 4 Weeks of Training Leads to Improved Anaerobic Endurance Capacity, but not Maximal Strength, Speed, or Power in Soccer Players. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2017, 27, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zebrowska, A.; Mizia-Stec, K.; Mizia, M.; Gasior, Z.; Poprzecki, S. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation improves endothelial function and maximal oxygen uptake in endurance-trained athletes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 15, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostenbrug, G.S.; Mensink, R.P.; Hardeman, M.R.; De Vries, T.; Brouns, F.; Hornstra, G. Exercise performance, red blood cell deformability, and lipid peroxidation: Effects of fish oil and vitamin E. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 83, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingley, L.; Macartney, M.J.; Brown, M.A.; McLennan, P.L.; Peoples, G.E. DHA-rich Fish Oil Increases the Omega-3 Index and Lowers the Oxygen Cost of Physiologically Stressful Cycling in Trained Individuals. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2017, 27, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakeman, J.R.; Lambrick, D.M.; Wooley, B.; Babraj, J.A.; Faulkner, J.A. Effect of an acute dose of omega-3 fish oil following exercise-induced muscle damage. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 117, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edholm, P.; Strandberg, E.; Kadi, F. Lower limb explosive strength capacity in elderly women: Effects of resistance training and healthy diet. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 123, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.I.; Julliand, S.; Reeds, D.N.; Sinacore, D.R.; Klein, S.; Mittendorfer, B. Fish oil-derived n-3 PUFA therapy increases muscle mass and function in healthy older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodacki, C.L.; Rodacki, A.L.; Pereira, G.; Naliwaiko, K.; Coelho, I.; Pequito, D.; Fernandes, L.C. Fish-oil supplementation enhances the effects of strength training in elderly women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Boit, M.; Sibson, R.; Sivasubramaniam, S.; Meakin, J.R.; Greig, C.A.; Aspden, R.M.; Thies, F.; Jeromson, S.; Hamilton, D.L.; Speakman, J.R.; et al. Sex differences in the effect of fish-oil supplementation on the adaptive response to resistance exercise training in older people: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyminska-Siemaszko, R.; Czepulis, N.; Lewandowicz, M.; Zasadzka, E.; Suwalska, A.; Witowski, J.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. The Effect of a 12-Week Omega-3 Supplementation on Body Composition, Muscle Strength and Physical Performance in Elderly Individuals with Decreased Muscle Mass. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10558–10574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninio, D.M.; Hill, A.M.; Howe, P.R.; Buckley, J.D.; Saint, D.A. Docosahexaenoic acid-rich fish oil improves heart rate variability and heart rate responses to exercise in overweight adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlory, C.; Wardle, S.L.; Macnaughton, L.S.; Witard, O.C.; Scott, F.; Dick, J.; Bell, J.G.; Phillips, S.M.; Galloway, S.D.; Hamilton, D.L.; et al. Fish oil supplementation suppresses resistance exercise and feeding-induced increases in anabolic signaling without affecting myofibrillar protein synthesis in young men. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, F.; Neya, M.; Hamazaki, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Tsuji, T. Supplementation with eicosapentaenoic acid-rich fish oil improves exercise economy and reduces perceived exertion during submaximal steady-state exercise in normal healthy untrained men. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, E.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Yanagimoto, K. Effect of eicosapentaenoic acids-rich fish oil supplementation on motor nerve function after eccentric contractions. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Yanagimoto, K.; Nakazato, K.; Hayamizu, K.; Ochi, E. Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids-rich fish oil supplementation attenuates strength loss and limited joint range of motion after eccentric contractions: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macartney, M.J.; Hingley, L.; Brown, M.A.; Peoples, G.E.; McLennan, P.L. Intrinsic heart rate recovery after dynamic exercise is improved with an increased omega-3 index in healthy males. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.I.; Atherton, P.; Reeds, D.N.; Mohammed, B.S.; Rankin, D.; Rennie, M.J.; Mittendorfer, B. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation increases the rate of muscle protein synthesis in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.I.; Atherton, P.; Reeds, D.N.; Mohammed, B.S.; Rankin, D.; Rennie, M.J.; Mittendorfer, B. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids augment the muscle protein anabolic response to hyperinsulinaemia-hyperaminoacidaemia in healthy young and middle-aged men and women. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2011, 121, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghravan, S.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Mazaheri, R.; Alizadeh, Z.; Mansournia, M.A. Effect of Omega-3 PUFAs Supplementation with Lifestyle Modification on Anthropometric Indices and Vo2 max in Overweight Women. Arch. Iran Med. 2016, 19, 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Lembke, P.; Capodice, J.; Hebert, K.; Swenson, T. Influence of omega-3 (n3) index on performance and wellbeing in young adults after heavy eccentric exercise. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2014, 13, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mickleborough, T.D.; Sinex, J.A.; Platt, D.; Chapman, R.F.; Hirt, M. The effects PCSO-524(R), a patented marine oil lipid and omega-3 PUFA blend derived from the New Zealand green lipped mussel (Perna canaliculus), on indirect markers of muscle damage and inflammation after muscle damaging exercise in untrained men: A randomized, placebo controlled trial. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J.; Radonic, P.W.; Wolever, T.M.; Wells, G.D. 21 days of mammalian omega-3 fatty acid supplementation improves aspects of neuromuscular function and performance in male athletes compared to olive oil placebo. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J.H.; Stucky, F.; Radonic, P.W.; Metherel, A.H.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Wells, G.D. Neuromuscular adaptations to sprint interval training and the effect of mammalian omega-3 fatty acid supplementation. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 117, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolotti, M.; Tappy, L.; Schneiter, P. Fish oil supplementation does not alter energy efficiency in healthy males. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 26, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinsley, G.M.; Gann, J.J.; Huber, S.R.; Andre, T.L.; La Bounty, P.M.; Bowden, R.G.; Gordon, P.M.; Grandjean, P.W. Effects of Fish Oil Supplementation on Postresistance Exercise Muscle Soreness. J. Diet Suppl. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rontoyanni, V.G.; Hall, W.L.; Pombo-Rodrigues, S.; Appleton, A.; Chung, R.; Sanders, T.A. A comparison of the changes in cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance during exercise following high-fat meals containing DHA or EPA. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouris, K.B.; McDaniel, J.L.; Weiss, E.P. The Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation on the Inflammatory Response to eccentric strength exercise. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2011, 10, 432–438. [Google Scholar]

- Busquets-Cortes, C.; Capo, X.; Martorell, M.; Tur, J.A.; Sureda, A.; Pons, A. Training Enhances Immune Cells Mitochondrial Biosynthesis, Fission, Fusion, and Their Antioxidant Capabilities Synergistically with Dietary Docosahexaenoic Supplementation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 8950384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capo, X.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Llompart, I.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Diet supplementation with DHA-enriched food in football players during training season enhances the mitochondrial antioxidant capabilities in blood mononuclear cells. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capo, X.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effects of dietary Docosahexaenoic, training and acute exercise on lipid mediators. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2016, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capo, X.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Batle, J.M.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Docosahexaenoic diet supplementation, exercise and temperature affect cytokine production by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mononuclear cells. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 72, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, M.; Capo, X.; Sureda, A.; Batle, J.M.; Llompart, I.; Argelich, E.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effect of DHA on plasma fatty acid availability and oxidative stress during training season and football exercise. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, M.; Capo, X.; Bibiloni, M.M.; Sureda, A.; Mestre-Alfaro, A.; Batle, J.M.; Llompart, I.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation promotes erythrocyte antioxidant defense and reduces protein nitrosative damage in male athletes. Lipids 2015, 50, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filaire, E.; Massart, A.; Rouveix, M.; Portier, H.; Rosado, F.; Durand, D. Effects of 6 weeks of n-3 fatty acids and antioxidant mixture on lipid peroxidation at rest and postexercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpott, J.D.; Donnelly, C.; Walshe, I.H.; MacKinley, E.E.; Dick, J.; Galloway, S.D.R.; Tipton, K.D.; Witard, O.C. Adding Fish Oil to Whey Protein, Leucine, and Carbohydrate Over a Six-Week Supplementation Period Attenuates Muscle Soreness Following Eccentric Exercise in Competitive Soccer Players. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capo, X.; Martorell, M.; Busquets-Cortes, C.; Sureda, A.; Riera, J.; Drobnic, F.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effects of dietary almond- and olive oil-based docosahexaenoic acid- and vitamin E-enriched beverage supplementation on athletic performance and oxidative stress markers. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4920–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capo, X.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Riera, J.; Drobnic, F.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effects of Almond- and Olive Oil-Based Docosahexaenoic- and Vitamin E-Enriched Beverage Dietary Supplementation on Inflammation Associated to Exercise and Age. Nutrients 2016, 8, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfan, M.; Ebrahim, K.; Baesi, F.; Mirakhori, Z.; Ghalamfarsa, G.; Bakhshaei, P.; Saboor-Yaraghi, A.A.; Razavi, A.; Setayesh, M.; Yousefi, M.; et al. The immunomodulatory effects of fish-oil supplementation in elite paddlers: A pilot randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2015, 99, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartibian, B.; Maleki, B.H.; Abbasi, A. The effects of ingestion of omega-3 fatty acids on perceived pain and external symptoms of delayed onset muscle soreness in untrained men. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2009, 19, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poprzecki, S.; Zajac, A.; Chalimoniuk, M.; Waskiewicz, Z.; Langfort, J. Modification of blood antioxidant status and lipid profile in response to high-intensity endurance exercise after low doses of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in healthy volunteers. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60 Suppl. 2, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P.; Gabriel, B.; Thies, F.; Gray, S.R. Fish oil supplementation augments post-exercise immune function in young males. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P.; Chappell, A.; Jenkinson, A.M.; Thies, F.; Gray, S.R. Fish oil supplementation reduces markers of oxidative stress but not muscle soreness after eccentric exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Boit, M.; Mastalurova, I.; Brazaite, G.; McGovern, N.; Thompson, K.; Gray, S.R. The Effect of Krill Oil Supplementation on Exercise Performance and Markers of Immune Function. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0139174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, K.E.; Newsham, K.R.; McDaniel, J.L.; Ezekiel, U.R.; Weiss, E.P. Effects of Short-Term Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation on Markers of Inflammation after Eccentric Strength Exercise in Women. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tartibian, B.; Maleki, B.H.; Abbasi, A. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation attenuates inflammatory markers after eccentric exercise in untrained men. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2011, 21, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filaire, E.; Massart, A.; Portier, H.; Rouveix, M.; Rosado, F.; Bage, A.S.; Gobert, M.; Durand, D. Effect of 6 Weeks of n-3 fatty-acid supplementation on oxidative stress in Judo athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2010, 20, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.M.; Jones, M.T.; Kirk, K.M.; Gable, D.A.; Repshas, J.T.; Johnson, T.A.; Andreasson, U.; Norgren, N.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H. Effect of Docosahexaenoic Acid on a Biomarker of Head Trauma in American Football. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.C.; Hunter, K.A.; Shaw, D.E.; Jackson, K.G.; Sharpe, G.R.; Johnson, M.A. Comparable reductions in hyperpnoea-induced bronchoconstriction and markers of airway inflammation after supplementation with 6.2 and 3.1 g/d of long-chain n-3 PUFA in adults with asthma. Br J Nutr 2017, 117, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickleborough, T.D.; Vaughn, C.L.; Shei, R.J.; Davis, E.M.; Wilhite, D.P. Marine lipid fraction PCSO-524 (lyprinol/omega XL) of the New Zealand green lipped mussel attenuates hyperpnea-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. Respir. Med. 2013, 107, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannan, J.D.; Bood, J.; Alkhabaz, A.; Balgoma, D.; Otis, J.; Delin, I.; Dahlen, B.; Wheelock, C.E.; Nair, P.; Dahlen, S.E.; et al. The effect of omega-3 fatty acids on bronchial hyperresponsiveness, sputum eosinophilia, and mast cell mediators in asthma. Chest 2015, 147, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Lopata, A.L.; Smuts, C.M.; Baatjies, R.; Jeebhay, M.F. Relationship between Serum Omega-3 Fatty Acid and Asthma Endpoints. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.; Moreira, A.; Fonseca, J.; Delgado, L.; Castel-Branco, M.G.; Haahtela, T.; Lopes, C.; Moreira, P. Dietary intake of alpha-linolenic acid and low ratio of n-6:n-3 PUFA are associated with decreased exhaled NO and improved asthma control. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompauer, I.; Demmelmair, H.; Koletzko, B.; Bolte, G.; Linseisen, J.; Heinrich, J. Association of fatty acids in serum phospholipids with lung function and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in adults. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 23, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickleborough, T.D.; Murray, R.L.; Ionescu, A.A.; Lindley, M.R. Fish oil supplementation reduces severity of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in elite athletes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, K.L.; Thomson, J.S.; Swift, R.J.; von Hurst, P.R. Role of nutrition in performance enhancement and postexercise recovery. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2015, 6, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeromson, S.; Gallagher, I.J.; Galloway, S.D.; Hamilton, D.L. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Skeletal Muscle Health. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 6977–7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Yaqoob, P.; Harvey, D.J.; Watts, A.; Newsholme, E.A. Incorporation of fatty acids by concanavalin A-stimulated lymphocytes and the effect on fatty acid composition and membrane fluidity. Biochem. J. 1994, 300 ( Pt 2), 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.G. Dietary fatty acids and membrane protein function. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1990, 1, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlory, C.; Galloway, S.D.; Hamilton, D.L.; McClintock, C.; Breen, L.; Dick, J.R.; Bell, J.G.; Tipton, K.D. Temporal changes in human skeletal muscle and blood lipid composition with fish oil supplementation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2014, 90, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiglesia, L.M.; Lorente-Cebrian, S.; Prieto-Hontoria, P.L.; Fernandez-Galilea, M.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Sainz, N.; Martinez, J.A.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J. Eicosapentaenoic acid promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and beige-like features in subcutaneous adipocytes from overweight subjects. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 37, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaluso, F.; Barone, R.; Catanese, P.; Carini, F.; Rizzuto, L.; Farina, F.; Di Felice, V. Do fat supplements increase physical performance? Nutrients 2013, 5, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryaki-Sönmez, G.S.B.; Vatansever-Ozen, S. Omega-3 fatty acids and exercise: A review of their combined effects on body composition and physical performance. Biomed. Human Kinetics 2011, 3, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hessvik, N.P.; Bakke, S.S.; Fredriksson, K.; Boekschoten, M.V.; Fjorkenstad, A.; Koster, G.; Hesselink, M.K.; Kersten, S.; Kase, E.T.; Rustan, A.C.; et al. Metabolic switching of human myotubes is improved by n-3 fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2090–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokling-Andersen, M.H.; Rustan, A.C.; Wensaas, A.J.; Kaalhus, O.; Wergedahl, H.; Rost, T.H.; Jensen, J.; Graff, B.A.; Caesar, R.; Drevon, C.A. Marine n-3 fatty acids promote size reduction of visceral adipose depots, without altering body weight and composition, in male Wistar rats fed a high-fat diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S.L.; Spriet, L.L. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation for 12 Weeks Increases Resting and Exercise Metabolic Rate in Healthy Community-Dwelling Older Females. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0144828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelec, M.; McCall, A.; Carling, C.; Legall, F.; Berthoin, S.; Dupont, G. Recovery in soccer: Part I - post-match fatigue and time course of recovery. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira Panza, V.S.; Diefenthaeler, F.; da Silva, E.L. Benefits of dietary phytochemical supplementation on eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage: Is including antioxidants enough? Nutrition 2015, 31, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.J. Muscle damage: Nutritional considerations. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1991, 1, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, P.; Pearson, S.; Whittingham-Dowd, J.; Allen, J. PPARgamma as a molecular target of EPA anti-inflammatory activity during TNF-alpha-impaired skeletal muscle cell differentiation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K. Does the Interdependence between Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Explain the Antioxidant Paradox? Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 5698931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammone, M.A.; Riccioni, G.; Parrinello, G.; D’Orazio, N. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Benefits and Endpoints in Sport. Nutrients 2018, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, K.H.; Anderson, S.D.; Bjermer, L.; Bonini, S.; Brusasco, V.; Canonica, W.; Cummiskey, J.; Delgado, L.; Del Giacco, S.R.; Drobnic, F.; et al. Exercise-induced asthma, respiratory and allergic disorders in elite athletes: Epidemiology, mechanisms and diagnosis: Part I of the report from the Joint Task Force of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) in cooperation with GA2LEN. Allergy 2008, 63, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mastana, S.S.; Lindley, M.R. n-3 Fatty acids and asthma. Nutr Res Rev 2016, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendell, S.G.; Baffi, C.; Holguin, F. Fatty acids, inflammation, and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.M.; Anzalone, A.J.; Turner, S.M. Protection Before Impact: The Potential Neuroprotective Role of Nutritional Supplementation in Sports-Related Head Trauma. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasadsri, L.; Wang, B.H.; Lee, J.V.; Erdman, J.W.; Llano, D.A.; Barbey, A.K.; Wszalek, T.; Sharrock, M.F.; Wang, H.J. Omega-3 fatty acids as a putative treatment for traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryhn, M. Prevention of Sports Injuries by Marine Omega-3 Fatty Acids. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34 Suppl. 1, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince Nelson, S.L.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Nietert, P.J.; Kamen, D.L.; Ramos, P.S.; Wolf, B.J. An evaluation of common methods for dichotomization of continuous variables to discriminate disease status. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2017, 46, 10823–10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).