Highlights

What are the main findings?

- InSAR shows a deforming area in La Palma Island coinciding with the direction of the rising magma of the Cumbre Vieja volcano.

- This area first experiences subsidence (the effect of the volcano’s weight on lower density sediments), then, 9 months before the eruption, uplift (effect of the magma upwelling from a depth of 15–25 km to 5 km).

What are the implications of the main findings?

- This unprecedented uplift is a precursor revealing shallower magmatic activity.

- The uplift can be a newly discovered precursor signal of future eruptions of the Cumbre Vieja volcano.

Abstract

In the last decades, satellite remote sensing has played a key role in Earth Observation, as an effective monitoring tool applied to geo-hazard identification and mitigation. In particular, the differential synthetic aperture radar interferometry technique provides incomparable information on ground movements related to volcanic unrest, co-eruptive deformation, and volcano flank motion. In this work, ground deformation data derived from Sentinel-1 satellites were analyzed over the Cumbre Vieja volcano, located in the southern part of La Palma Island, Canary archipelago. The volcano started to erupt on 19 September 2021, after a seismic swarm. The eruption buried hundreds of buildings and properties, causing severe economic losses. Analyzing the vertical ground displacement of the volcano in the year preceding the eruption, the results show that ground deformation can be considered a precursor of the eruption, which allows us to identify the phases of the magmatic ascent up to the opening of the eruptive vent. Interestingly, after a subsidence phase lasting 4 months, the ground displacement rate reverted and an uplift was observed, lasting 9 months, marking an uplift on the Cumbre Vieja volcano related to volcanic activity. This can be interpreted as the effect of the magma rising from the deeper chamber (15–25 km) to an intermediate stagnation zone (5 km) that provided a measurable anticipation of the eruption by 9 months. In the future, regular monitoring of Cumbre Vieja could adopt uplift detection as an indicator for shallow magma activity and as a possible eruption precursor.

1. Introduction

La Palma is the northwesternmost island belonging to the Canary Islands, a volcanic archipelago located at the passive NW margin of the African plate (Figure 1). It is the second youngest island, and during its history it experienced N to S migration of its volcanic activity [1,2] up to the current Cumbre Vieja volcano; the Cumbre Vieja volcano constitutes the southernmost part of the island, and during its 125 ka of eruptive activity has been the most active volcano in the Canary Islands [2,3,4,5].

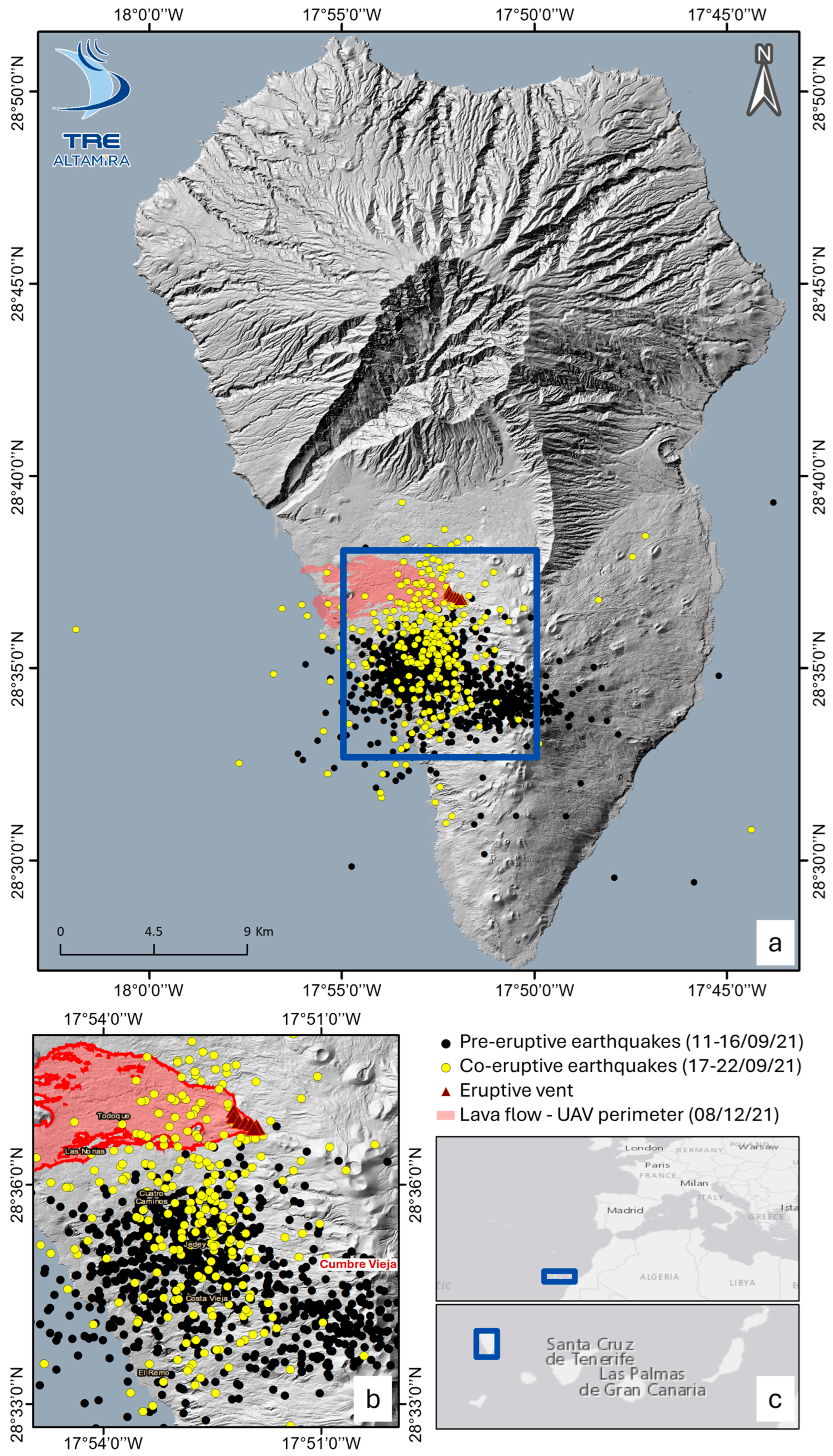

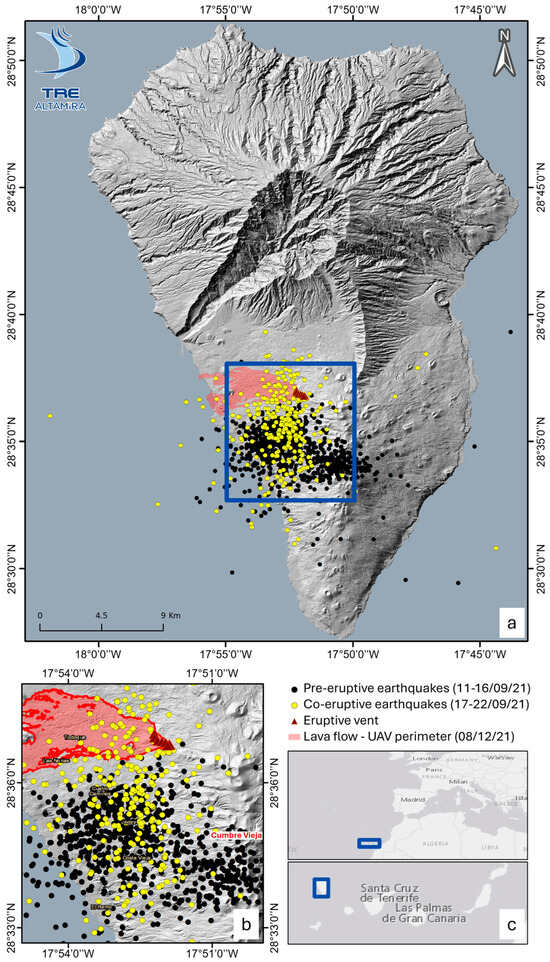

Figure 1.

(a,b): La Palma Island with indication of the epicenters of the earthquakes in the period 11–16 September 2021 (black dots) and 17–22 September 2021 (yellow dots), of the eruptive vents (red triangles) and of the lava flow (red area); (b): Enlarged view of the blue box in (a); (c): location of the Canary Islands (blue box; top) and of La Palma Island (blue box) in the Canary Islands (bottom).

The western flank of Cumbre Vieja is considered unstable, plausibly due to the presence of a sliding surface at depth, and is potentially tsunamigenic [3]. The scarp/headwall of the deep-seated sliding surface coincided with the site of the 1949 [3,6] and 2021 eruptions [7]. The W flank showed subsidence deformations in both GNSS (with data covering a time span from 1994 to 2007; [8]) and InSAR data (with data covering a time span from 1992 to 2000 and from 2003 to 2008; [9]), and the subsidence was related to the presence at depth of volcanoclastic material with lower density compared to the high-density material that makes up the volcano edifice [9,10,11].

In 1949 three eruptive centers formed in the Cumbre Vieja ridge during the so-called San Juan eruption [6,12], which was preceded by more than two years of seismic activity [6,13]. In 1971 the Teneguía eruption, that began by opening a several-hundred-meter-long fissure, was preceded by strong seismicity [14].

Similarly, the latest eruption, the Tajogaite eruption, which occurred on the 19 September 2021 and lasted for 85 days [15], was long anticipated by seismic activity [5,16]; in fact, in October 2017 and February 2018 two seismic swarms were recorded in the Cumbre Vieja area [5,16,17,18,19], concomitant with anomalous gas emission, likely associated with a magmatic intrusion at 15–25 km depth [16,20], in correspondence with a sub-horizontal volume aligned along a E–W direction that is known to store pre-eruptive magma [21,22,23,24,25,26,27] and from where these swarms are originated. A third swarm started on the 8 September 2021, anticipating the onset of the Tajogaite eruption by 11 days [20,28]. It consisted of two phases: a pre-eruptive phase, lasting from 8 to 16 September, and a co-eruptive phase, from 17 to 22 September (Figure 1).

Short-term ground deformation measured during the pre-eruptive phase suggested an initial magma source at ca. 5 km depth b.s.l., with a volume change of 5.62 × 106 m3 [28]. On the other hand, the deformation during the co-eruptive phase was associated with two dikes at two different depths (950 and 1419 a.s.l.), characterized by a variation in strike (deeper: strike 116°; shallower: strike 144°) and a little variation in dip (deeper: dip 62°; shallower: dip 64°), thus showing an upward shift in seismicity from the pre-eruptive phase (ca. 5 km) to the co-eruptive phase (ca. 1 km), which enabled linking the source of the pre-eruptive deformation to the surface [28].

Precursor events such as these are also associated with ground deformation; ground displacement and/or its rate of change (displacement rate) have been identified as reliable precursors of volcanic eruptions [29,30,31,32,33]. In particular, space-borne interferometric techniques are largely employed to measure ground displacement, given the wide areas over which volcanic phenomena occur [34,35,36,37].

Here we demonstrate that the variation of the displacement rate (acceleration), measured by interferometric techniques with synthetic aperture radar data of the Sentinel-1 constellation, allows us to anticipate the eruption of Cumbre Vieja (La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain) by about nine months.

2. Materials and Methods

InSAR is a technique that analyzes radar signals emitted from satellites to detect and measure changes on the Earth’s surface. In fact, by comparing phase shifts between a series of radar images acquired over time, often, after the necessary data processing to address issues like phase wrapping, the displacement of targets can be measured in the range of a few millimeters to tens of centimeters per year. It is widely used to detect ground movements caused by natural and anthropic factors, such as earthquakes [38,39], subsidence [40,41], landslides [42,43], and volcanoes [35,44].

Its first application to volcanoes was in 1995 [45], when this technique was utilized to measure the apparent deflation of Mount Etna (Italy). After this seminal work, many other studies followed [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] that underlined the potential and limits of this technique. The inherent difficulties include the effect of atmospheric noise, which can affect measurement accuracy, the days-long revisit time, which makes it difficult to monitor areas experiencing fast pace changes, the presence of snow, ice, and vegetation cover, which often limit the size of the study area, line of sight, which reduces the sensitivity to N–S oriented movements.

Despite this, InSAR has proved a game-changer in volcanology [56] as it allows for worldwide deformation measurements over large areas covering entire volcanic edifices.

The same technique has also been exported to ground-based platforms: to measure conduit pressurization pulses and crater rim sliding in a Stromboli volcano (Italy) [57,58], to set-up early warning frameworks [59], to use radar amplitude maps instead of interferograms [60], to study the geomorphological characteristics of volcanic flanks and deposits, and to map magmatic intrusions [61].

Over the years, numerous InSAR techniques have been developed to process satellite radar data, such as Permanent Scatterer Interferometry (PSI) [62,63], Small BAseline Subset (SBAS) [64], and SqueeSAR [65].

The PSI methodology [35,63] represents a cornerstone in the evolution of radar interferometry. It provided the first robust framework capable of mitigating temporal and geometric decorrelation by selecting stable scatterers. This approach allowed for the precise separation of the atmospheric phase screen from deformation and residual topographic errors, laying the foundation for modern time-series analysis [66].

It exploits multiple SAR images acquired over the same area and appropriate data processing to separate the displacement phase component from atmospheric, topographic, and orbital errors. This approach relies on identifying pixels, known as Permanent Scatterers (PS), where the response to the radar is dominated by a strong reflecting object and remains constant over time. PSI allows for the estimation of deformation time series and deformation velocity with high precision, but its major constraint is that it is limited to scatterers exhibiting sufficiently high coherence (e.g., buildings, exposed rocks, or metal structures), which typically leads to low PS density in non-urban or vegetated areas.

Following the initial PSI developments, Berardino et al. [64] introduced the Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) technique. This method mitigates spatial decorrelation by selecting interferometric pairs with short baselines and reduces phase noise through multi-looking, relying on coherence thresholds for pixel selection. By linking independent small baseline subsets, SBAS significantly enhances both spatial and temporal sampling compared to the original PSI framework. Although the initial algorithm operated on multi-looked data, limiting the detection of local deformation, a full-resolution extension was later developed by Lanari et al. [67]. Furthermore, Hooper et al. [68] advanced the field by proposing a selection method based on phase characteristics, enabling the identification of stable natural targets with low amplitude that are typically overlooked by amplitude-based algorithms [66].

In this work, to maximize the density of measurement points over the variable terrain of La Palma, the SqueeSAR algorithm [65] was used and applied to data retrieved by Sentinel-1, belonging to the European Space Agency. SqueeSAR™ represents a major advancement in multi-interferogram processing as it overcomes the distinction between deterministic and stochastic radar targets by jointly processing PS and Distributed Scatterers (DS). While PS are deterministic point-wise targets dominating the resolution cell (e.g., man-made structures), DS correspond to areas exhibiting moderate coherence, such as debris flows, scattered outcrops, or homogeneous ground, which are typical of volcanic environments.

Unlike PS, which are coherent over long time intervals, DS are stochastic targets characterized by a multitude of individual scattering centers. Under the Gaussian scattering assumption based on the central limit theorem [69], the multi-temporal SAR data vector z relative to a DS pixel can be described by a zero-mean, complex, multivariate Gaussian distribution:

where H denotes complex conjugate transposition and C is the covariance matrix defined as E = Since the true covariance matrix is unknown, SqueeSAR estimates the coherence matrix by identifying a set of statistically homogeneous pixels (SHP) in the neighborhood of each target, applying a space-adaptive filter (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) to select pixels with similar amplitude distributions [65]. The estimated coherence matrix terms are given by:

where represents the estimated coherence and the spatially filtered interferometric phase between image k and image n.

Unlike PS, DS do not necessarily satisfy the phase triangularity property (i.e., ). Therefore, the SqueeSAR algorithm implements a Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) to “squeeze” the information contained in the coherence matrix and retrieve the optimal vector of N phase values that best fits the observations [65].

This rigorous statistical approach allows for the extraction of signals from DS that would otherwise be discarded by standard PSI techniques due to low coherence in single interferograms. The result is a substantial improvement in the spatial density of measurement points, particularly in rural and volcanic areas, and a significant noise reduction in the displacement time series.

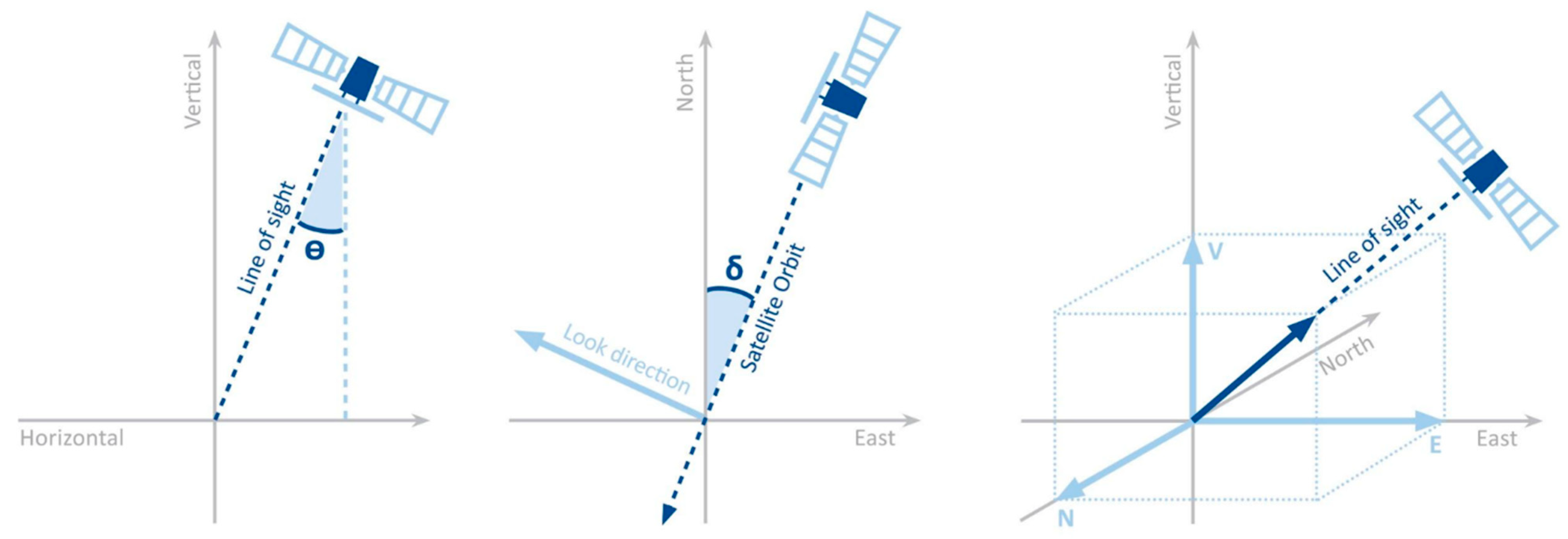

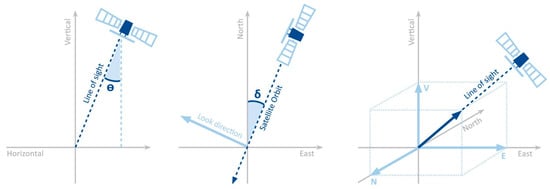

Nowadays there is a large availability of satellite platforms equipped with microwave radar sensors in the C-band (5–6 GHz, 5.6 cm wavelength), X-band (8–12 GHz, 3.1 cm wavelength), and L-band (1–2 GHz, 23.6 cm wavelength). One of the limitations of this technique is that only the component of a displacement parallel to the sensor’s line of sight (LOS) can be measured. The LOS angle varies depending on the satellite and imaging mode and on its orbit (whether the satellite is in its ascending or descending phase). Ascending and descending vectors therefore measure the displacement along different LOS and can be combined to obtain the vertical (Vv) and horizontal eastward components (Vh). This procedure [70] consists in resampling the dataset into a grid where for each cell the average ascending and descending velocities (Va, Vd) are combined according to the following equations:

where θa is the line-of-sight incidence angle in ascending orbit and θd the line-of-sight incidence angle in descending orbit.

Va = Vv cos(−θa) + Vh sin(−θa)

Vd = Vv cosθd + Vh sinθd

To measure the surface deformation over La Palma Island, the SqueeSAR algorithm [65] was used and applied to Sentinel-1 data in the C-band (5.55 cm wavelength). Images were acquired in the Interferometric Wide (IW) swath mode with a 5 × 14 m spatial resolution. Both ascending and descending geometries have been analyzed to enable the calculation of the vertical and horizontal components. The images span from 3 September 2019 to 16 September 2021 (123 scenes) for the descending track 169 and from 1 September 2019 to 14 September 2021 (124 scenes) for the ascending track 60 (Figure 2; Table 1).

Figure 2.

Schematics of the acquisition geometry of the satellite.

Table 1.

Line of sight geometrical acquisition parameters.

3. Results

The data analysis focused on the area where co-eruptive earthquakes were recorded, including the area of the vents of the eruption (Figure 1a,b). The Sentinel-1 data acquired along the ascending and descending orbits have been reprojected to obtain vertical displacement values.

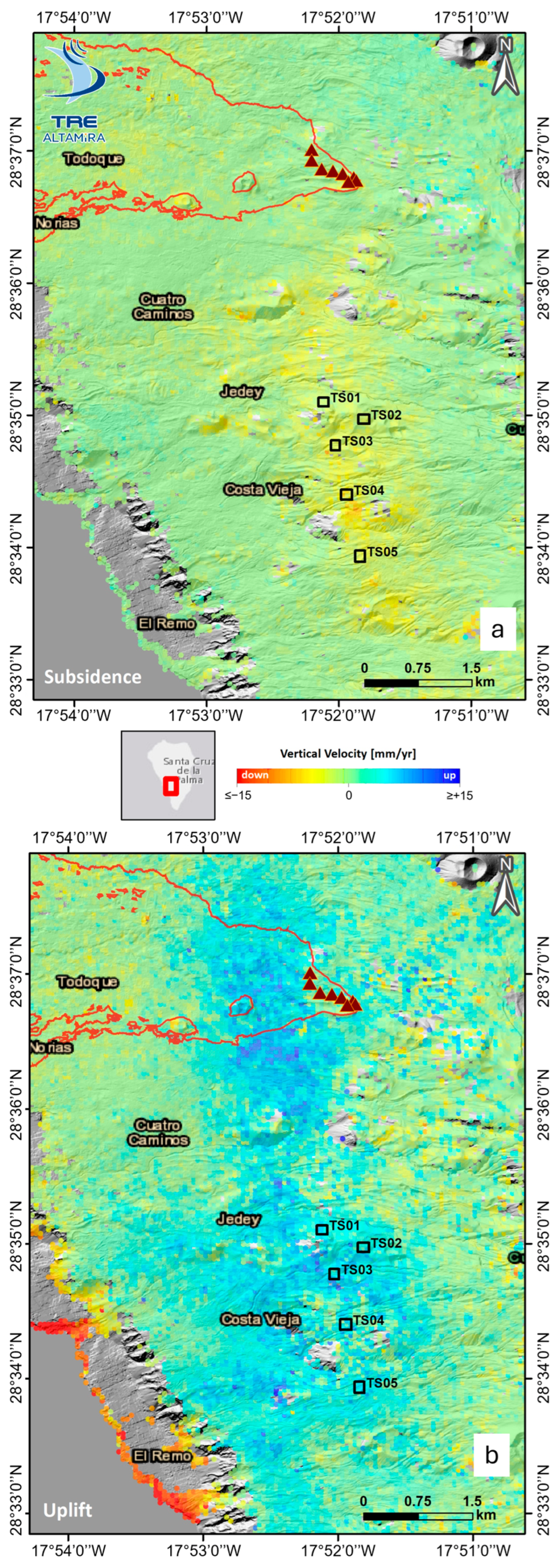

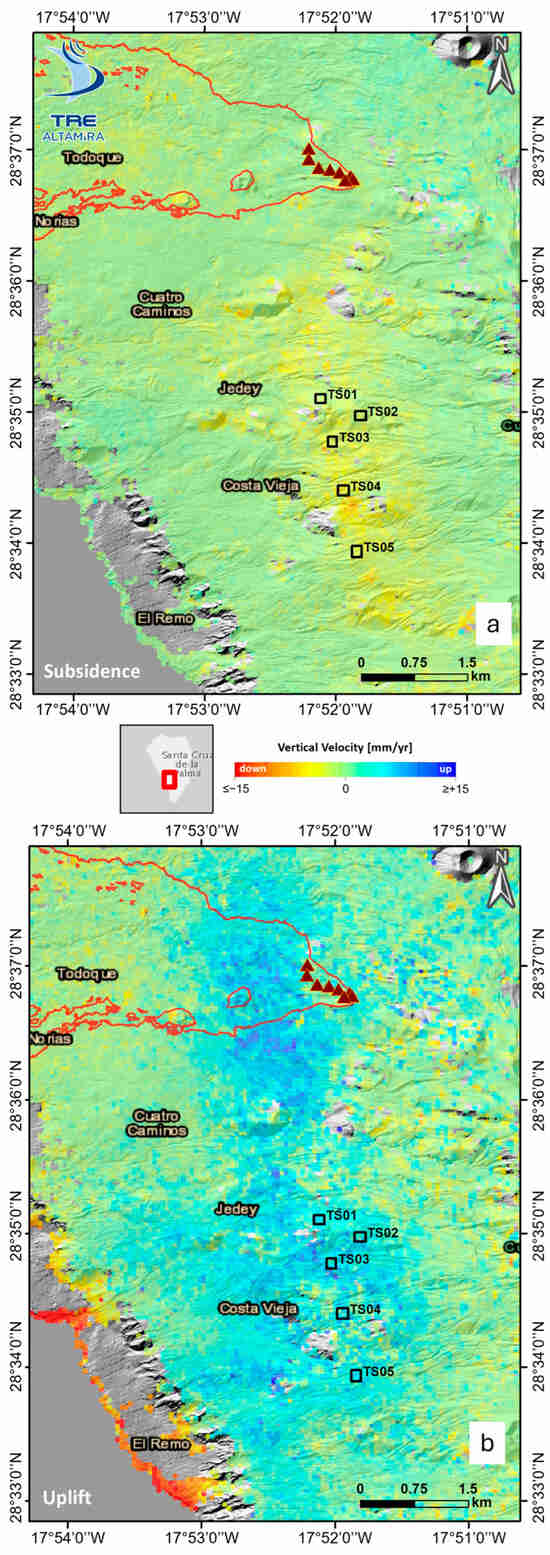

Two maps have been produced, one covering the period spanning from the 3 September 2019 to the 30 December 2020 (Figure 3a) and another one from the 1 January 2021 to the 14 September 2021 (Figure 3b). The cut-off between these two periods has been selected to mark the trend change, as the first period is dominated by subsidence and the second one by uplift. From these maps, five representative pixels have been selected and for each one a displacement time series has been extracted, spanning the whole time range from 3 September 2019 to 14 September 2021 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Displacement maps showing the vertical components during: (a) a period dominated by subsidence (3 September 2020–30 December 2020); (b) a period dominated by uplift (1 January 2021–14 September 2021). Created using SqueeSAR algorithm [65]. The red triangles represent the eruptive vents and the area contoured in red the lava flow.

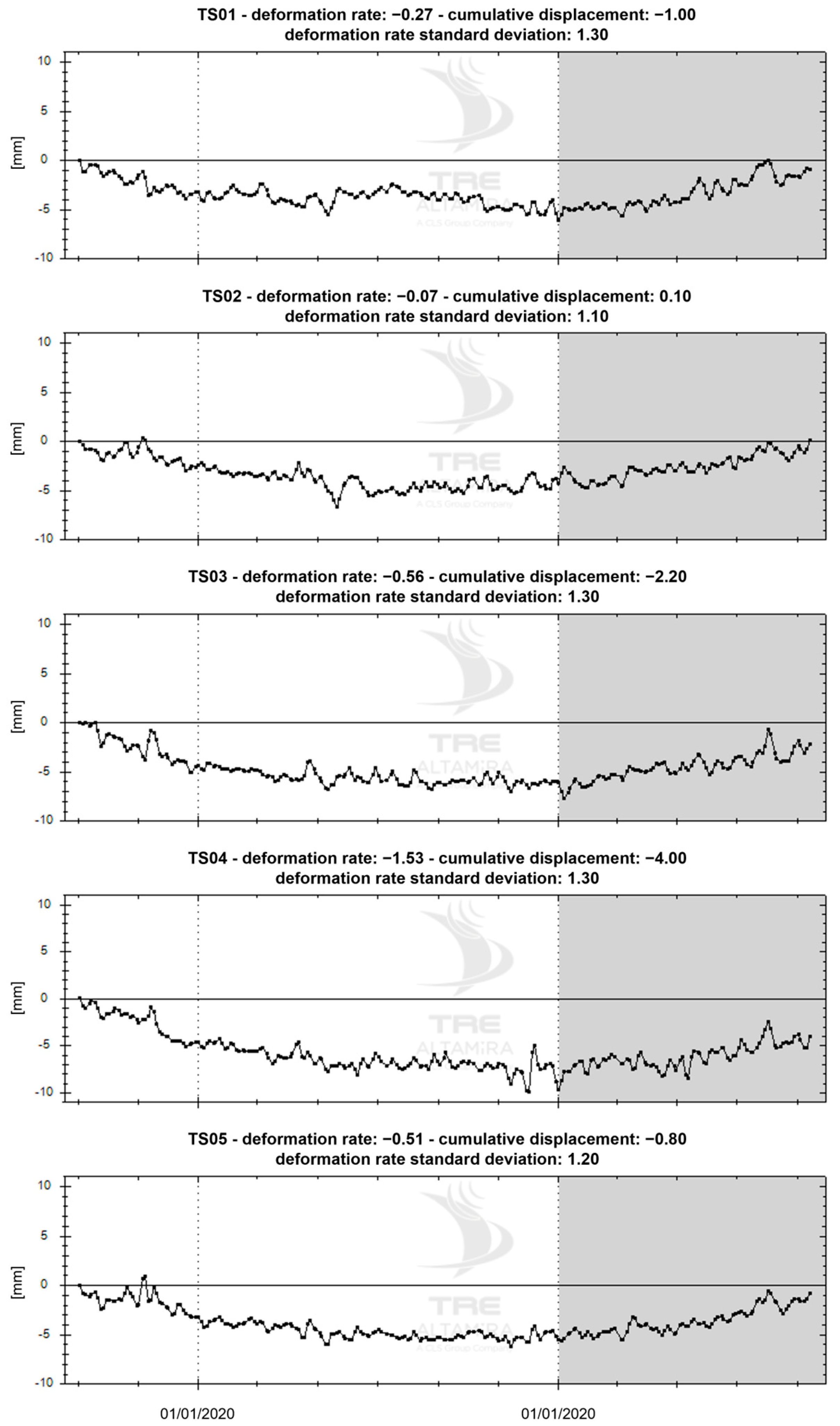

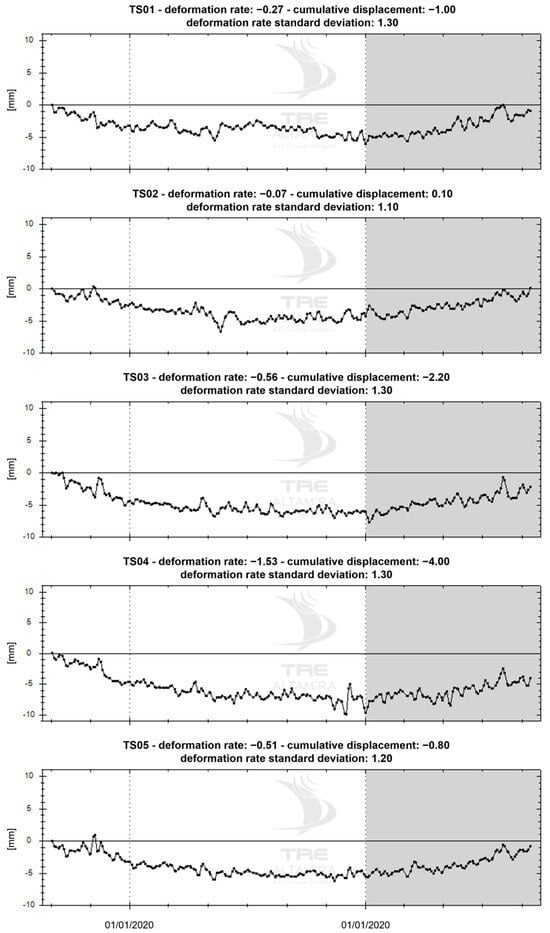

Figure 4.

Displacement time series spanning from the 3 September 2019 to the 14 September 2021 relative to five pixels selected from the deforming area (Figure 3). The shaded parts of the graphs highlight the uplift phase.

The displacement maps clearly highlight a N–S-oriented area affected by deformation, coinciding with the main direction of the uprising magma, as confirmed by the epicenters of the co-eruptive earthquakes (Figure 1). The two maps show opposite behaviors; the period from the 3 September 2019 to the 30 December 2020 denotes a spatially homogeneous subsidence, while the period from the 1 January 2021 to the 14 September 2021 shows a clear uplift.

The five time-series extracted from the maps show the transition between these two behaviors and confirm the overall spatial similarity. At the beginning of the monitoring period, all these points experience subsidence, near to 5 mm in 4 months.

Since January 2020 the subsidence rate starts to gradually decrease until May 2020, when the ground is stable, and no subsidence is recorded in the area. Subsequently, a trend change occurs in January 2021, with an uplift up to 5–7 mm in 9 months (Figure 4). After two years since the first measurement, the uplift has roughly compensated for the previous subsidence.

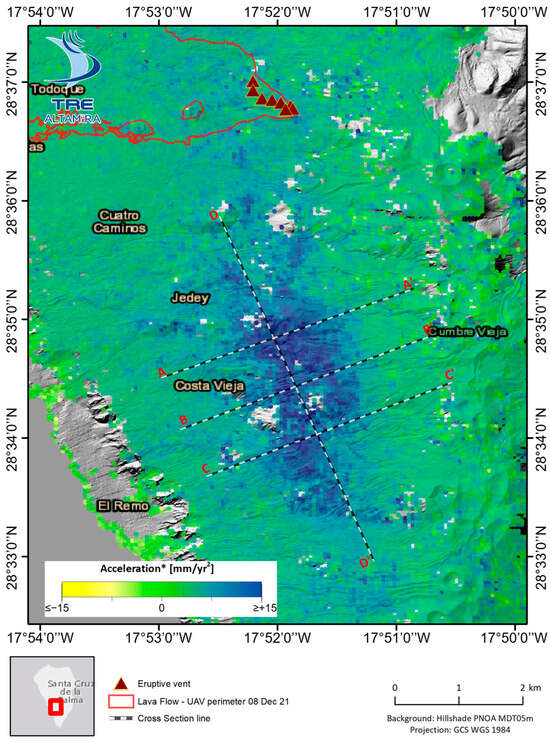

Another interesting result derives from the variation over time of the vertical displacement rate (i.e., the vertical ground acceleration measured by satellite InSAR data over several days, not to be confused with the ground acceleration measured by seismic sensors). In this case, it is possible to observe the strong acceleration of the soil that was localized in the area since January 2021 by producing an acceleration map (Figure 5).

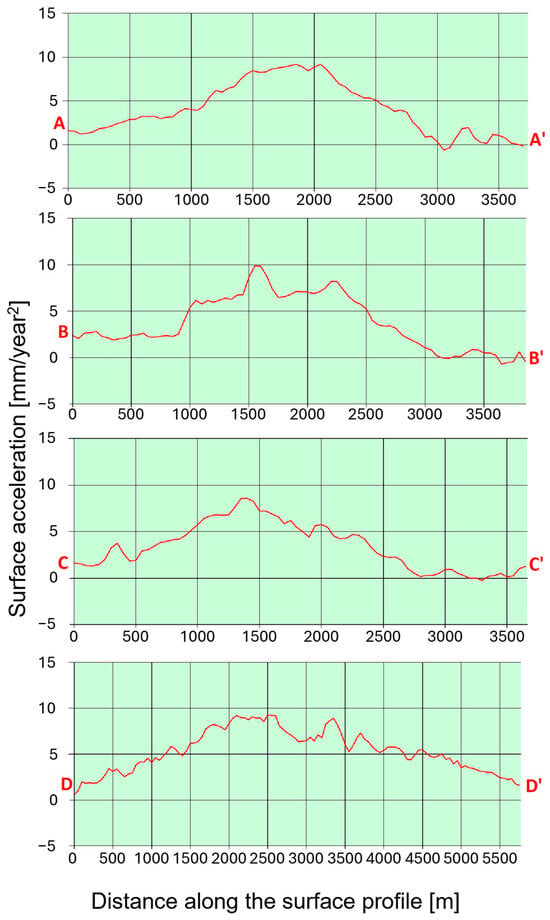

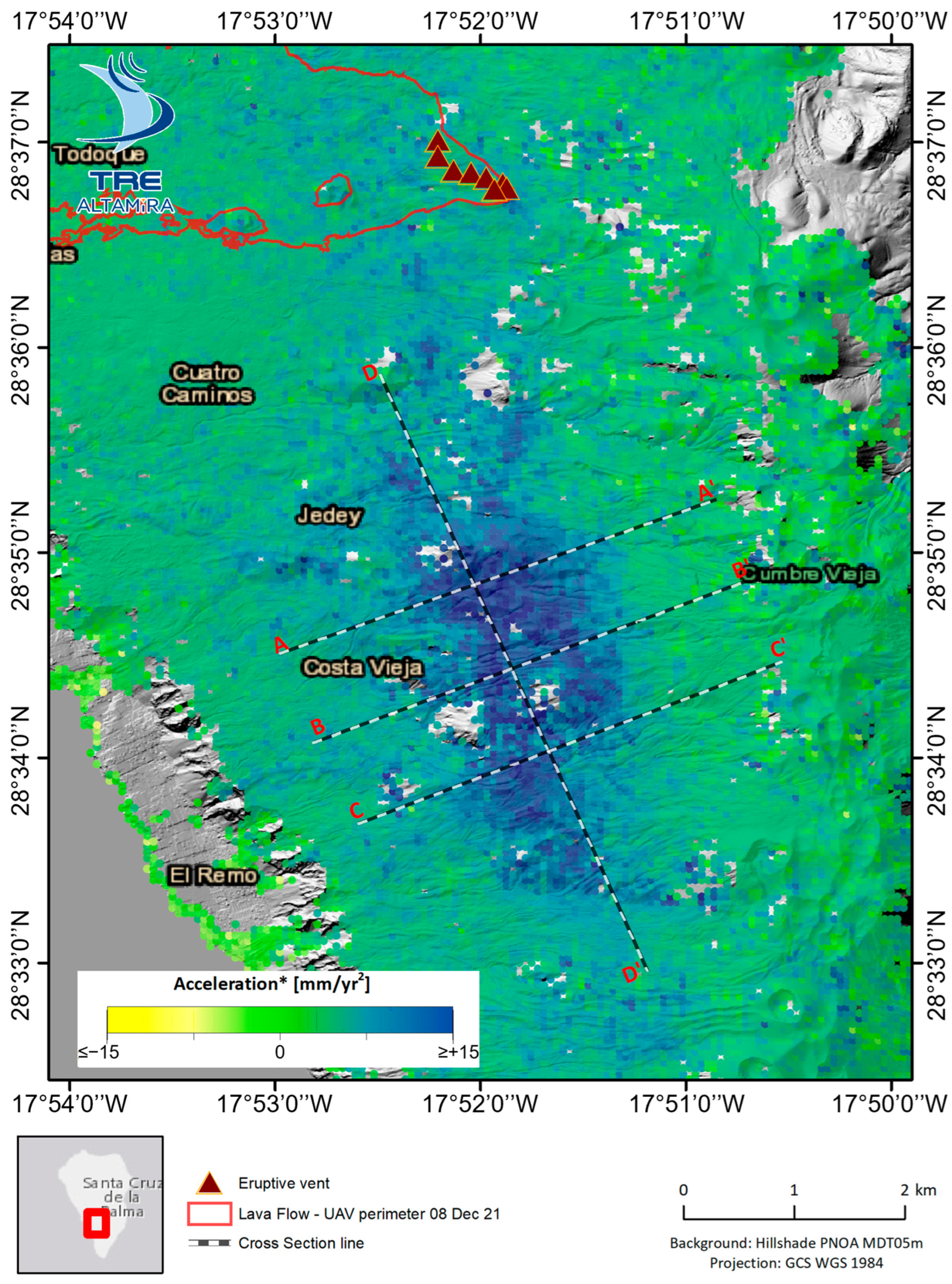

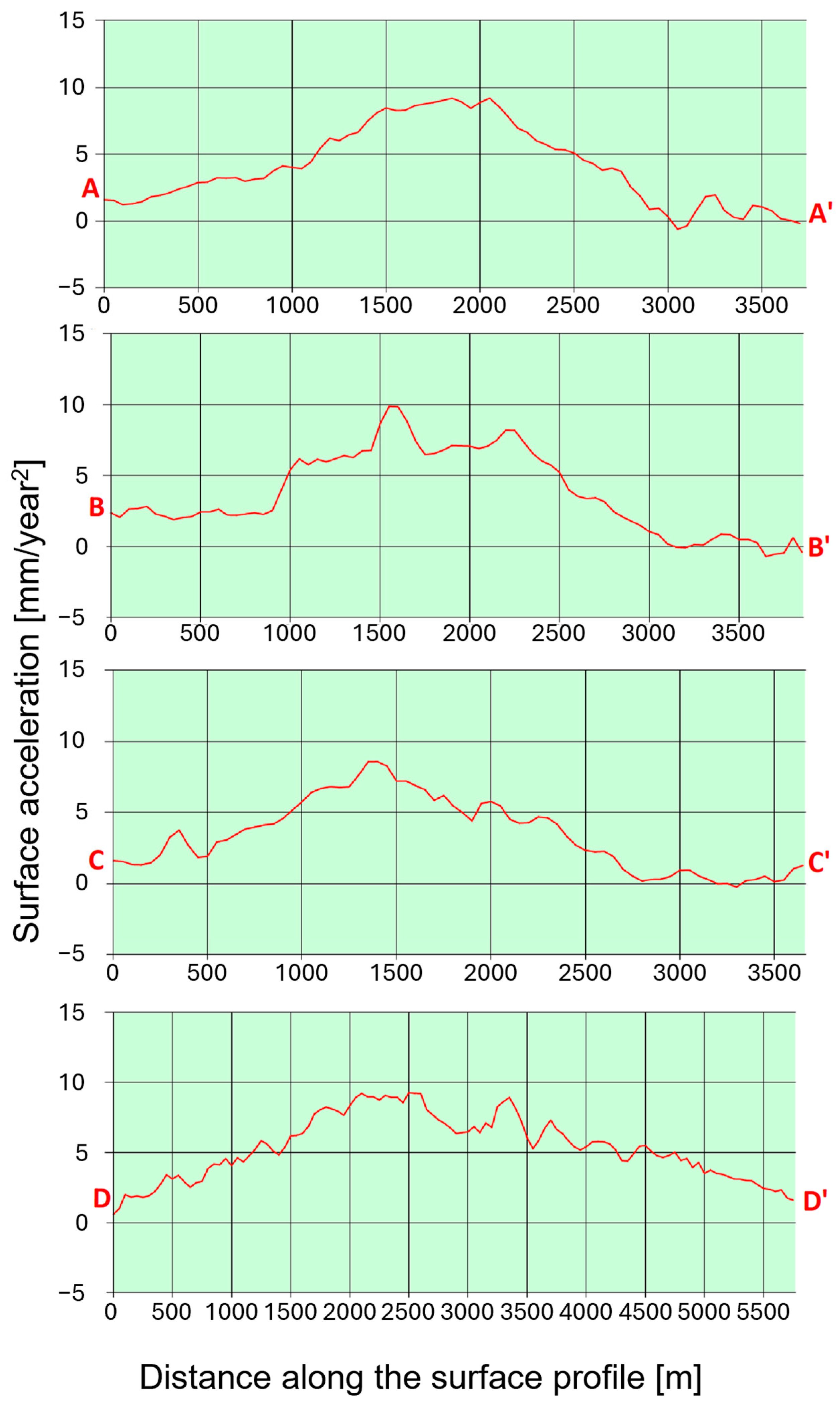

Figure 5.

Vertical ground acceleration measured by Sentinel-1 from 3 September 2019 to 14 September 2021. Created using SqueeSAR algorithm [65]. The red triangles represent the eruptive vents and the area contoured in red the lava flow. The letters indicate the ending and starting points (e.g., AA’) of acceleration cross-sections shown in Figure 6.

By calculating some acceleration cross-sections, it appears that the vertical acceleration is concentrated in a reduced NE–SW shaped area, coinciding with the area of maximum occurrence of co-eruptive earthquakes (Figure 6). The external areas, meanwhile, even if involved in the pre-eruptive seismic crisis, do not show ground accelerations measurable with InSAR techniques.

4. Discussion

From the displacement data measured with the Sentinel-1 radar constellation, processed using the SqueeSAR technique, it was possible to highlight how the area involved in the pre-eruptive and co-eruptive phases was characterized by an inversion of the shift data from subsidence to uplift during 2020. Before January 2020, the trend showed a subsidence (nearly 5 mm in 4 months), while during all of 2020 no evident shifts were recorded. While the subsidence of that sector of the island of La Palma was a known fact and had been interpreted as the effect of the volcano’s weight on lower density volcaniclastic sediments [9,10,11], until that point the uplift was only partially associated with magma upwelling (in its last uplift phases; [28]). The location of the deformation sources and the hypocenters are linked to a rapid rise of the magma from the deepest area (hypocenters 2017–2018, 15–25 km) to a short-term accumulation (about 5 km) and, eventually, to a final ascent towards the surface that led to the eruption [28].

Moreover, the uplift began in January 2021, 9 months before the pre-eruptive and co-eruptive seismic crises, and it had never been analyzed before [15]; plausibly, it is to be considered connected with the ascent and stagnation of magma in an area between 15–25 km (seismic swarms of 2017 and 2018) [16], and the source area of pre-eruptive deformation identified at approximately 5 km [28].

This switch from subsidence to uplift caused by magma rising from depth and injecting in a shallower reservoir with subsequent pressurization of the chamber and upward deformation of the ground above it is a well-recognized phenomenon that has been observed at several volcanic systems worldwide and is sometimes called resurgence [71] or reinflation [72].

The most famous case is probably Campi Flegrei (Italy) where this phenomenon is called bradyseism. The Campi Flegrei caldera is a volcanic field hosting a nested caldera complex that historically experiences periods of subsidence (around 1–2 cm per year) occasionally interrupted by rapid uplifts [73], as occurred in 1950–1952 (74 cm uplift), 1970–1972 (159 cm uplift), and 1982–1984 (178 cm uplift) [74,75]. The latest event, in particular, was associated with 16,000 earthquakes up to 4.0 magnitude [76]. The subsidence resumed following this event and was again interrupted in 2005 with a new uplift phase that was again associated with seismic activity that intensified since 2018 [77].

Among basaltic calderas that displayed uplift and seismicity prior to eruptions (such as Kilauea in 2018 and Bárðarbunga in 2014), the Sierra Negra volcano (Galápagos Islands) has shown one of the highest vertical deformations. Sierra Negra presents a flat-topped sill-like magma reservoir at around 2 km depth below the caldera [78,79,80]; before the 2018 eruption, magma supply and accumulation to this shallow reservoir drove 6.5 m of pre-eruptive uplift and seismicity over thirteen years [81].

Another example is Piton de La Fournaise, a shield hot-spot volcano on Réunion Island. The pre-eruptive inflations preceding two eruptions (one in November and another in December 2005) have been linked to the pressure caused by a dyke and/or a shallow source located at a depth around 500–2300 m [82].

Within the same Canary Archipelago as La Palma, the El Hierro volcano also experienced a similar phenomenon. Before the 2011 submarine eruption, around 10,000 earthquakes occurred [83]. The strongest seismic event before the eruption reached a magnitude of ML = 4.3 and was recorded at 12 km depth [83], corresponding to the locations of magma pockets below El Hierro [84]. The pre-eruptive phase was also associated with an uplift of more than 5 cm [83].

When dealing with volcanic risk management, great attention is paid to eruption early warning methods based, among others, on monitoring pre-eruptive seismicity [81], gas flux tracking magma movement at depth [85], and product composition that can alter lava viscosity and mobility [86,87,88]. Ground deformation is already a well-known indicator for eruptions and volcanic unrest [89,90], although a specific correlation with the Cumbra Vieja eruptions and a volcanological explanation linking the ground uplift to magma storages at intermediate depth was lacking so far. The periodic monitoring of La Palma Island using the InSAR technique could be useful in the future to further enhance the early warning system but also to provide more cross-validation data for other studies concerning magma ascent beneath Cumbra Vieja.

5. Conclusions

The island of La Palma represents one of the greatest potential risks within the whole volcanic Canary archipelago. Though no loss of human life occurred thanks to the early warning system set in place by the authorities which enabled the timely evacuation of the area, the eruption formed a complex cinder cone produced by fire fountain activity, and fed several lava flows causing severe direct and indirect damage; in the end more than 2800 buildings and almost 1000 hectares of land were hit by lava and pyroclastic material.

The latest eruptive phase of the Cumbre Vieja volcano started on 19 September 2021 and lasted for 85 days, long anticipated by seismic activity, making it the first eruption on La Palma Island since the advent of InSAR.

The temporal evolution of ground motion, combined with seismic swarm data, allowed us to correlate surface deformation with magma migration from approximately 25 km to approximately 1 km in depth. Specifically, the pre-eruptive phase which took place from 8 to 16 September 2021, that is, at the end of the uplift and few days before the eruption, has been associated with a magma intrusion at around 5 km b.s.l.

The analysis was conducted on Sentinel-1 data created using the SqueeSAR algorithm; it highlights the important role of satellite remote sensing in the early warning and monitoring of volcanic activity. The results reveal that vertical ground motions anticipated the 2021 Cumbre Vieja eruption in the same N–S-oriented area affected by co-eruptive earthquakes. This area can be outlined with higher precision by mapping the ground acceleration instead of the ground displacement. However, the deformation that occurred in this area was not monotonous. Observations revealed an initial phase of spatially homogeneous subsidence between September 2019 and December 2020 followed by a phase of uplift that started in January 2021, nine months before the eruption. This uplift measured up to 5–7 mm in 9 months and compensated for the previous subsidence.

The subsidence-to-uplift inversion was identified as a crucial indicator of the magmatic ascent phases, plausibly linked to the ascent and stagnation of magma from a deep zone (15–25 km, associated with the 2017 and 2018 seismic swarms) to an intermediate accumulation zone (about 5 km during the pre-eruptive phase), and finally to the ascent towards the surface that led to the eruption (in the co-eruptive phase from 17 to 22 September 2021, with seismic crisis and opening of the eruptive fracture on the surface).

The pre-eruptive uplift, that, to the best of our knowledge, has never been described before in Cumbre Vieja, anticipated the eruption by 9 months. These results underline the fundamental role of ground deformation monitoring by satellite interferometry, a technique that was not available during the previous eruptions on La Palma. The ground uplift can be considered a proxy for the magma migration during the final phases of its ascent.

These results confirm that variations in deformation rate and acceleration, detected by InSAR, can act as quantitative and spatially resolved precursors to volcanic eruptions. The ability to detect these signals months in advance underscores the importance of continuous satellite monitoring to improve forecasting capabilities and risk mitigation strategies in volcanic regions and particularly in Cumbra Vieja, where InSAR data relative to previous eruptions were not available. Furthermore, the integration of InSAR-derived displacement data with seismic and geochemical observations improves our understanding of pre-eruptive dynamics and supports the development of comprehensive early warning systems.

This experience emphasizes the importance of conducting a thorough investigation to characterize the state of unrest of Cumbra Vieja and to better understand possible precursors and pinpoint the time of eruption.

Since the 2021 eruption has been the first one for which InSAR data were available, possible future eruptions are needed to verify that vertical ground displacement can be used as an eruptive precursor and that the association with seismic activity and magma ascent is consistent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.I., R.M. and J.G.R.; software, R.M. and J.G.R.; data curation, R.M. and J.G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.I.; writing—review and editing, E.I.; visualization, E.I., R.M. and J.G.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Roberto Montalti and Javier Garcia Robles were employed by the company RE-ALTAMIRA and Open Cosmos Europe. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ancochea, E.; Hernán, F.; Cendrero, A.; Cantagrel, J.M.; Fúster, J.; Ibarrola, E.; Coello, J. Constructive and destructive episodes in the building of a young oceanic island, La Palma, Canary Islands, and genesis of the Caldera de Taburiente. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1994, 60, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, J.C.; Day, S.J.; Guillou, H.; Torrado, F.J.P. Giant quaternary landslides in the evolution of La Palma and El Hierro, Canary Islands. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1999, 94, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.N.; Day, S. Cumbre Vieja volcano-potential collapse and tsunami at La Palma, Canary Islands. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 3397–3400. [Google Scholar]

- Klügel, A.; Galipp, K.; Hoernle, K.; Hauff, F.; Groom, S. Geochemical and volcanological evolution of La Palma, Canary Islands. J. Petrol. 2017, 58, 1227–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Escayo, J.; Hu, Z.; Camacho, A.G.; Samsonov, S.V.; Prieto, J.F.; Tiampo, K.F.; Palano, M.; Mallorquí, J.J.; Ancochea, E. Detection of volcanic unrest onset in La Palma, Canary Islands, evolution and implications. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klügel, A.; Schmincke, H.U.; White, J.D.L.; Hoernle, K.A. Chronology and volcanology of the 1949 multi-vent rift-zone eruption on La Palma (Canary Islands). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1999, 94, 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- González, P.J. Volcano-tectonic control of Cumbre Vieja. Science 2022, 375, 1348–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, J.F.; Gonzalez, P.J.; Seco, A.; Rodríguez-Velasco, G.; Tunini, L.; Perlock, P.A.; Arjona, A.; Aparicio, A.; Camacho, A.G.; Rundle, J.B.; et al. Geodetic and Structural Research in La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain: 1992–2007 Results. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2009, 166, 1461–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.J.; Tiampo, K.F.; Camacho, A.G.; Fernández, J. Shallow flank deformation at Cumbre Vieja volcano (Canary Islands): Implications on the stability of steep-sided volcano flanks at oceanic islands. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 297, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, X.; Jones, A.G. Internal structure of the western flank of the Cumbre Vieja volcano, La Palma, Canary Islands, from land magnetotelluric imaging. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, F.; Ledo, J.; Ślęzak, K.; Martínez van Dorth, D.; Cabrera-Pérez, I.; Pérez, N.M. La Palma island (Spain) geothermal system revealed by 3D magnetotelluric data inversion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.M.B. Contribución al Estudio de la Erupción del Volcán del Nambroque o San Juan (Isla de La Palma): 24 de Junio–4 de Agosto de 1949; Instituto Geográfico y Catastral: Chetumal, Mexico, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, H.; Costa, F.; Martí, J. Years to weeks of seismic unrest and magmatic intrusions precede monogenetic eruptions. Geology 2016, 44, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.K.; Troll, V.R.; Carracedo, J.C.; Nicholls, P.A. The magma plumbing system for the 1971 Teneguía eruption on La Palma, Canary Islands. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2015, 170, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, J.C.; Troll, V.R.; Day, J.M.; Geiger, H.; Aulinas, M.; Soler, V.; Deegan, F.M.; Perez-Torrado, F.J.; Gisbert, G.; Gazel, E.; et al. The 2021 eruption of the Cumbre Vieja volcanic ridge on La Palma, Canary Islands. Geol. Today 2022, 38, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-González, P.A.; Luengo-Oroz, N.; Lamolda, H.; D’Alessandro, W.; Albert, H.; Iribarren, I.; Moure-García, D.; Soler, V. Unrest signals after 46 years of quiescence at Cumbre Vieja, La Palma, Canary Islands. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2020, 392, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, J.; Pinel, V.; López, C.; Geyer, A.; Abella, R.; Tárraga, M.; Blanco, M.J.; Castro, A.; Rodríguez, C. Causes and mechanisms of the 2011–2012 El Hierro (Canary Islands) submarine eruption. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, J.; Ortiz, R.; Gottsmann, J.; Garcia, A.; De La Cruz-Reyna, S. Characterising unrest during the reawakening of the central volcanic complex on Tenerife, Canary Islands, 2004–2005, and implications for assessing hazards and risk mitigation. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2009, 182, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Fresno, C.; Cesca, S.; Klügel, A.; Domínguez Cerdeña, I.; Díaz-Suárez, E.A.; Dahm, T.; García-Cañada, L.; Meletlidis, S.; Milkereit CValenzuela-Malebrán, C.; López-Díaz, R.; et al. Magmatic plumbing and dynamic evolution of the 2021 La Palma eruption. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longpré, M.A. Reactivation of Cumbre Vieja volcano. Science 2021, 374, 1197–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayton, K.; Gazel, E.; Wieser, P.; Troll, V.R.; Carracedo, J.C.; La Madrid, H.; Roman, D.C.; Ward, J.; Aulinas, M.; Geiger, H.; et al. Deep magma storage during the 2021 La Palma eruption. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezzotti, M.L.; Touret, J.L.; Lustenhouwer, W.J.; Neumann, E.R. Melt and fluid inclusions in dunite xenoliths from La Gomera, Canary Islands: Tracking the mantle metasomatic fluids. Eur. J. Mineral. Ohne Beih. 1994, 6, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezzotti, M.L.; Andersen, T.; Neumann, E.R.; Simonsen, S.L. Carbonatite melt–CO2 fluid inclusions in mantle xenoliths from Tenerife, Canary Islands: A story of trapping, immiscibility and fluid–rock interaction in the upper mantle. Lithos 2002, 64, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Klügel, A.; Hansteen, T.H.; Galipp, K. Magma storage and underplating beneath Cumbre Vieja Volcano, La Palma (Canary Islands). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 236, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klügel, A.; Longpré, M.A.; García-Cañada, L.; Stix, J. Deep intrusions, lateral magma transport and related uplift at ocean island volcanoes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2015, 431, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klügel, A.; Albers, E.; Hansteen, T.H. Mantle and crustal xenoliths in a tephriphonolite From La Palma (Canary Islands): Implications for phonolite formation at oceanic island volcanoes. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 761902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, E.R.; Wulff-Pedersen, E.; Johnsen, K.; Andersen, T.; Krogh, E. Petrogenesis of spinel harzburgite and dunite suite xenoliths from Lanzarote, eastern Canary Islands: Implications for the upper mantle. Lithos 1995, 35, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.; Valerio, E.; Giudicepietro, F.; Macedonio, G.; Casu, F.; Lanari, R. Pre-and Co-Eruptive Analysis of the September 2021 Eruption at Cumbre Vieja Volcano (La Palma, Canary Islands) Through DInSAR Measurements and Analytical Modeling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL097293. [Google Scholar]

- Voight, B. A method for prediction of volcanic eruptions. Nature 1988, 332, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Jones, G.; Rymer, H. Detecting volcanic eruption precursors: A new method using gravity and deformation measurements. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2002, 113, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlà, T.; Intrieri, E.; Di Traglia, F.; Casagli, N. A statistical-based approach for determining the intensity of unrest phases at Stromboli volcano (Southern Italy) using one-step-ahead forecasts of displacement time series. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 669–683. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, E.P.; Camejo-Harry, M.; Christopher, T.; Contreras-Arratia, R.; Edwards, S.; Graham, O.; Johnson, M.; Juman, A.; Latchman, J.L.; Lynch, L.; et al. Responding to eruptive transitions during the 2020–2021 eruption of La Soufrière volcano, St. Vincent. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronico, D.; Del Bello, E.; D’Oriano, C.; Landi, P.; Pardini, F.; Scarlato, P.; de’ Michieli Vitturi, M.; Taddeucci, J.; Cristaldi, A.; Ciancitto, F.; et al. Uncovering the eruptive patterns of the 2019 double paroxysm eruption crisis of Stromboli volcano. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, M.E.; Simons, M. An InSAR-based survey of volcanic deformation in the central Andes. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2004, 5, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, T.J.; Pritchard, M.E.; Riddick, S.N. Duration, magnitude, and frequency of subaerial volcano deformation events: New results from Latin America using InSAR and a global synthesis. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, I.; Papanikolaou, X.; Floyd, M.; Ji, K.H.; Kontoes, C.; Paradissis, D.; Zacharis, V. Mapping inflation at Santorini volcano, Greece, using GPS and InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Nolesini, T.; Solari, L.; Ciampalini, A.; Frodella, W.; Steri, D.; Allotta, B.; Rindi, A.; Marini, L.; Monni, N.; et al. Lava delta deformation as a proxy for submarine slope instability. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018, 488, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sandwell, D.T.; Smith-Konter, B. Coseismic displacements and surface fractures from Sentinel-1 InSAR: 2019 Ridgecrest earthquakes. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2020, 91, 1979–1985. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, J.; Ferreira, A.M.; Funning, G.J. Systematic comparisons of earthquake source models determined using InSAR and seismic data. Tectonophysics 2012, 532, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.H.M.; Liu, Z.; Du, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Ge, L. A novel framework for combining polarimetric Sentinel-1 InSAR time series in subsidence monitoring-A case study of Sydney. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113694. [Google Scholar]

- Solari, L.; Del Soldato, M.; Bianchini, S.; Ciampalini, A.; Ezquerro, P.; Montalti, R.; Raspini, F.; Moretti, S. From ERS 1/2 to Sentinel-1: Subsidence monitoring in Italy in the last two decades. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, F.; Nardini, O.; Fiaschi, S.; Montalti, R.; Intrieri, E.; Raspini, F. Multi-Sensor Satellite Analysis for Landslide Characterization: A Case of Study from Baipaza, Tajikistan. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Montalti, R.; Solari, L.; Bianchini, S.; Del Soldato, M.; Raspini, F.; Casagli, N. A Sentinel-1-based clustering analysis for geo-hazards mitigation at regional scale: A case study in Central Italy. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2019, 10, 2257–2275. [Google Scholar]

- Di Traglia, F.; De Luca, C.; Manzo, M.; Nolesini, T.; Casagli, N.; Lanari, R.; Casu, F. Joint exploitation of space-borne and ground-based multitemporal InSAR measurements for volcano monitoring: The Stromboli volcano case study. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 260, 112441. [Google Scholar]

- Massonnet, D.; Briole, P.; Arnaud, A. Deflation of Mount Etna monitored by spaceborne radar interferometry. Nature 1995, 375, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacourt, C.; Briole, P.; Achache, J.A. Tropospheric corrections of SAR interferograms with strong topography. Application to Etna. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 2849–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massonnet, D.; Feigl, K.L. Radar interferometry and its application to changes in the Earth’s surface. Rev. Geophys. 1998, 36, 441–500. [Google Scholar]

- Beauducel, F.; Briole, P.; Froger, J.L. Volcano-wide fringes in ERS synthetic aperture radar interferograms of Etna (1992–1998): Deformation or tropospheric effect? J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2000, 105, 16391–16402. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, S.T.; Pritchard, M.E. Decadal volcanic deformation in the Central Andes Volcanic Zone revealed by InSAR time series. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2013, 14, 1358–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmundsson, F.; Hooper, A.; Hreinsdóttir, S.; Vogfjörd, K.S.; Ófeigsson, B.G.; Heimisson, E.R.; Dumont, S.; Parks, M.; Spaans, K.; Gudmundsson, G.B.; et al. Segmented lateral dyke growth in a rifting event at Bárðarbunga volcanic system, Iceland. Nature 2015, 517, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albino, F.; Biggs, J.; Lazecký, M.; Maghsoudi, Y. Routine processing and automatic detection of volcanic ground deformation using Sentinel-1 InSAR data: Insights from African volcanoes. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5703. [Google Scholar]

- Chaussard, E.; Amelung, F.; Aoki, Y. Characterization of open and closed volcanic systems in Indonesia and Mexico using InSAR time series. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 3957–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, M.T.; Jónsdóttir, K.; Hooper, A.; Holohan, E.P.; Halldórsson, S.A.; Ófeigsson, B.G.; Cesca, S.; Vogfjörd, K.S.; Sigmundsson, F.; Högnadóttir, T.; et al. Gradual caldera collapse at Bárdarbunga volcano, Iceland, regulated by lateral magma outflow. Science 2016, 353, aaf8988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, H.İ.; Yılmaztürk, F.; Orhan, O. An investigation of volcanic ground deformation using InSAR observations at Tendürek Volcano (Turkey). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, C.A.; Brantley, S.R.; Antolik, L.; Babb, J.L.; Burgess, M.; Calles, K.; Cappos, M.; Chang, J.C.; Conway, S.; Desmither, L.; et al. The 2018 rift eruption and summit collapse of Kīlauea Volcano. Science 2019, 363, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, M.P.; Zebker, H.A. Volcano geodesy using InSAR in 2020: The past and next decades. Bull. Volcanol. 2022, 84, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Del Ventisette, C.; Rosi, M.; Mugnai, F.; Intrieri, E.; Moretti, S.; Casagli, N. Ground-based InSAR reveals conduit pressurization pulses at Stromboli volcano. Terra Nova 2013, 25, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Berardino, P.; Borselli, L.; Calabria, P.; Calvari, S.; Casalbore, D.; Casagli, N.; Casu, F.; Chiocci, F.L.; Civico, R.; et al. Generation of deposit-derived pyroclastic density currents by repeated crater rim failures at Stromboli Volcano (Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 2024, 86, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagli, N.; Catani, F.; Del Ventisette, C.; Luzi, G. Monitoring, prediction, and early warning using ground-based radar interferometry. Landslides 2010, 7, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrieri, E.; Di Traglia, F.; Del Ventisette, C.; Gigli, G.; Mugnai, F.; Luzi, G.; Casagli, N. Flank instability of Stromboli volcano (Aeolian Islands, Southern Italy): Integration of GB-InSAR and geomorphological observations. Geomorphology 2013, 201, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, G.; Reitano, D.; Spampinato, L.; Vogfjörd, K.S.; Barsotti, S.; Cacciola, L.; Geyer, A.; Guðjónsson, D.S.; Guehenneux, Y.; Komorowski, J.-C.; et al. The integrated multidisciplinary European volcano infrastructure: From the conception to the implementation. Ann. Geophys. 2022, 65, DM320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Analysis of permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2000. IEEE 2000 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. Taking the Pulse of the Planet: The Role of Remote Sensing in Managing the Environment. Proceedings (Cat. No. 00CH37120), Honolulu, HI, USA, 24–28 July 2000; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 761–763. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardino, P.; Fornaro, G.; Lanari, R.; Sansosti, E. A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Fumagalli, A.; Novali, F.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F.; Rucci, A. A new algorithm for processing interferometric data-stacks: SqueeSAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 3460–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, M.; Monserrat, O.; Cuevas-González, M.; Devanthéry, N.; Crippa, B. Persistent scatterer interferometry: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanari, R.; Mora, O.; Manunta, M.; Mallorquí, J.J.; Berardino, P.; Sansosti, E. A small-baseline approach for investigating deformations on full-resolution differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, A.; Zebker, H.; Segall, P.; Kampes, B. A new method for measuring deformation on volcanoes and other natural terrains using InSAR persistent scatterers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamler, R.; Hartl, P. Synthetic aperture radar interferometry. Inverse Probl. 1998, 14, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofani, V.; Raspini, F.; Catani, F.; Casagli, N. Persistent Scatterer Interferometry (PSI) technique for landslide characterization and monitoring. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 1045–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F.; Acocella, V.; Caricchi, L. Caldera resurgence driven by magma viscosity contrasts. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, F.; Pritchard, M.E.; Basualto, D.; Lazo, J.; Córdova, L.; Lara, L.E. Rapid reinflation following the 2011–2012 rhyodacite eruption at Cordón Caulle volcano (Southern Andes) imaged by InSAR: Evidence for magma reservoir refill. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 9552–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vivo, B.; Rolandi, G. Volcanological risk associated with Vesuvius and Campi Flegrei. In Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei, and Campanian Volcanism; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 471–493. [Google Scholar]

- Del Gaudio, C.; Aquino, I.; Ricciardi, G.P.; Ricco, C.; Scandone, R. Unrest episodes at Campi Flegrei: A reconstruction of vertical ground movements during 1905–2009. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2010, 195, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.Y.; Kilburn, C.R. Intrusion and deformation at Campi Flegrei, southern Italy: Sills, dikes, and regional extension. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, D.; Kilburn, C.; Edwards, S. Volcanic unrest scenarios and impact assessment at Campi Flegrei caldera, Southern Italy. J. Appl. Volcanol. 2020, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, D.; Barberi, G.; Martino, C. Seismic Images of Pressurized Sources and Fluid Migration Driving Uplift at the Campi Flegrei Caldera During 2020–2024. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelung, F.; Jónsson, S.; Zebker, H.; Segall, P. Widespread uplift and ‘trapdoor’faulting on Galapagos volcanoes observed with radar interferometry. Nature 2000, 407, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwick, W.W., Jr.; Geist, D.J.; Jonsson, S.; Poland, M.; Johnson, D.J.; Meertens, C.M. A volcano bursting at the seams: Inflation, faulting, and eruption at Sierra Negra volcano, Galápagos. Geology 2006, 34, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Segall, P.; Zebker, H. Constraints on magma chamber geometry at Sierra Negra Volcano, Galápagos Islands, based on InSAR observations. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2006, 150, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.F.; La Femina, P.C.; Ruiz, M.; Amelung, F.; Bagnardi, M.; Bean, C.J.; Bernard, B.; Ebinger, C.; Gleeson, M.; Grannell, J.; et al. Caldera resurgence during the 2018 eruption of Sierra Negra volcano, Galápagos Islands. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, A.; Famin, V.; Bachèlery, P.; Cayol, V.; Fukushima, Y.; Staudacher, T. Cyclic magma storages and transfers at Piton de La Fournaise volcano (La Réunion hotspot) inferred from deformation and geochemical data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 270, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Blanco, M.J.; Abella, R.; Brenes, B.; Cabrera Rodríguez, V.M.; Casas, B.; Domínguez Cerdeña, I.; Felpeto, A.; Fernández de Villalta, M.; del Fresno, C.; et al. Monitoring the volcanic unrest of El Hierro (Canary Islands) before the onset of the 2011–2012 submarine eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroncik, N.A.; Klügel, A.; Hansteen, T.H. The magmatic plumbing system beneath El Hierro (Canary Islands): Constraints from phenocrysts and naturally quenched basaltic glasses in submarine rocks. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2009, 157, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazahaya, R.; Shinohara, H.; Mori, T.; Iguchi, M.; Yokoo, A. Pre-eruptive inflation caused by gas accumulation: Insight from detailed gas flux variation at Sakurajima volcano, Japan. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 11–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansecki, C.; Lee, R.L.; Shea, T.; Lundblad, S.P.; Hon, K.; Parcheta, C. The tangled tale of Kīlauea’s 2018 eruption as told by geochemical monitoring. Science 2019, 366, eaaz0147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, G.; Corsaro, R.A.; D’Oriano, C.; Pompilio, M. Petrological monitoring of active volcanoes: A review of existing procedures to achieve best practices and operative protocols during eruptions. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2021, 419, 107365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubide, T.; Márquez, Á.; Ancochea, E.; Huertas, M.J.; Herrera, R.; Coello-Bravo, J.J.; Sanz-Manga, D.; Mulder, J.; MacDonald, A.; Galindo, I. Discrete magma injections drive the 2021 La Palma eruption. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Intrieri, E.; Nolesini, T.; Bardi, F.; Del Ventisette, C.; Ferrigno, F.; Frangioni, S.; Frodella, W.; Gigli, G.; Lotti, A.; et al. The ground-based InSAR monitoring system at Stromboli volcano: Linking changes in displacement rate and intensity of persistent volcanic activity. Bull. Volcanol. 2014, 76, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Calvari, S.; D’Auria, L.; Nolesini, T.; Bonaccorso, A.; Fornaciai, A.; Esposito, A.; Cristaldi, A.; Favalli, M.; Casagli, N. The 2014 effusive eruption at Stromboli: New insights from in situ and remote-sensing measurements. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).