Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A new curriculum-based pipeline effectively reduces overfitting and stabilizes the training of ViT models for semantic segmentation with very few labeled remote sensing images.

- A progressive augmentation strategy combining geometric and intensity adaptations further improves the model’s generalization ability.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- This approach allows for the training of ViT-based segmentation models with minimal annotation effort, facilitating more data-efficient remote sensing analysis.

- The cross-domain version of the pipeline successfully uses labeled data from a source domain to boost performance on a target domain with limited labels.

Abstract

Semantic segmentation of remote sensing images is crucial for geospatial applications but is severely hampered by the prohibitive cost of pixel-level annotations. Although semi-supervised learning (SSL) offers a solution by leveraging unlabeled data, its application to Vision Transformers (ViTs) often encounters overfitting and even training instability under extreme label scarcity. To tackle these challenges, we propose a Curriculum-based Self-supervised and Semi-supervised Pipeline (CSSP). The pipeline adopts a staged, easy-to-hard training strategy, commencing with in-domain pretraining for robust feature representation, followed by a carefully designed finetuning stage to prevent overfitting. The pipeline further integrates a novel Difficulty-Adaptive ClassMix (DA-ClassMix) augmentation that dynamically reinforces underperforming categories and a Progressive Intensity Adaptation (PIA) strategy that systematically escalates augmentation strength to maximize model generalization. Extensive evaluations on the Potsdam, Vaihingen, and Inria datasets demonstrate state-of-the-art performance. Notably, with only 1/32 of the labeled data on the Potsdam dataset, the CSSP reaches 82.16% mIoU, nearly matching the fully supervised result (82.24%). Furthermore, we extend the CSSP to a semi-supervised domain adaptation (SSDA) scenario, termed Cross-Domain CSSP (CDCSSP), which outperforms existing SSDA and unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA) methods. This work establishes a stable and highly effective framework for training ViT-based segmentation models with minimal annotation overhead.

1. Introduction

Remote sensing image (RSI) semantic segmentation is pivotal for numerous applications, including land cover classification, farmland segmentation, building extraction, and urban planning. Deep learning has become the dominant approach in this field. Recently, Vision Transformers (ViTs) [1,2] have demonstrated superior generalization capabilities over Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), owing to their global modeling capacity and high scalability. However, the supervised training of such models typically requires large amounts of labeled data, the acquisition of which is often costly and time-consuming. Semi-supervised learning (SSL) [3] presents a promising alternative by leveraging both limited labeled data and abundant unlabeled data, thereby reducing reliance on extensive manual annotations. Nevertheless, effectively applying large-scale ViT-based segmentation models to RSI semi-supervised semantic segmentation (SSSS) remains challenging. This work identifies three intertwined core challenges:

The first issue is model optimization and training stability under extreme label scarcity. ViTs, characterized by their large parameter counts and weaker inductive biases towards image data, generally demand more labeled samples than CNNs. When labels are scarce, the supervised teacher model is prone to overfitting in the early phase of training, which subsequently degrades the quality of pseudo-labels generated for unlabeled data in later training iterations. The resulting error propagation of pseudo-labels can even lead to training instability for some classical SSL frameworks. For instance, we observe that directly applying Cross Pseudo Supervision (CPS) [4] and Mean Teacher (MT) [5]—originally designed for CNNs or lightweight models—to train a swinV2-based [6] UPerNet [7] results in training divergence (see Section 4.4.1).

The second issue is the difficulty of regulating data augmentation complexity. While data augmentation is essential for enhancing model robustness and generalization in SSL, its complexity is a double-edged sword. Appropriately tuned augmentations expand the effective data domain [8], but excessively strong perturbations can degrade performance [9]. Most existing works employ fixed, empirically tuned augmentation policies throughout training. This static configuration fails to adapt to the model’s evolving learning state, preventing the systematic maximization of the model’s generalization potential. Moreover, current methods often apply uniform augmentation across all semantic categories, neglecting inherent variations in learning difficulty, which can cause the overall performance to be bottlenecked by underperforming categories.

The third issue is the underexplored but highly practical scenario of semi-supervised domain adaptation (SSDA). In practice, fully annotated source domain images sharing the same label space with the target domain task are often accessible. Most research focuses on unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA) [10], which assumes no target domain labels—an extreme setting that limits performance. A more realistic and promising scenario is SSDA, where a small number of target domain annotations are available alongside the labeled source data. This setting not only mitigates the source–target distribution mismatch of the same category (a common issue in UDA due to the lack of target-side guidance) but also provides additional supervisory signals compared with standard SSL. Despite its potential, SSDA for RSI semantic segmentation remains underexplored.

These challenges are not isolated but exacerbate each other. For example, the instability of large-scale ViTs in SSL can be intensified by inappropriate data augmentation, a problem that becomes more acute in complex cross-domain (SSDA) scenarios. Collectively, they point to a fundamental bottleneck: the lack of a dedicated training paradigm that can systematically coordinate model capacity, data complexity, and optimization stability for large ViTs in low-data regimes.

To address these challenges, we propose a Curriculum-based Self-supervised and Semi-supervised Pipeline (CSSP) for swin transformer-based segmentation models. The core philosophy of the CSSP is to guide the training of large ViTs through a structured, stage-wise pipeline where model capacity and data complexity are collaboratively and progressively increased in a coordinated manner. This “easy-to-hard” curriculum is crucial for ensuring training stability while steadily boosting performance. From a model-level curriculum, we first pretrain the encoder in a self-supervised manner on RSI data to learn in-domain representations, enhancing subsequent SSL stability. We then strategically transition from a lightweight decoder to a heavyweight decoder, with the former providing a stable start and the latter offering greater robustness to pseudo-label noise in advanced stages. From a data-level curriculum, training begins with in-domain samples and gradually incorporates more complex data variations via two novel strategies: (1) our proposed Difficulty-Adaptive ClassMix (DA-ClassMix) augmentation, which enhances the model’s geometric-semantic robustness and emphasizes underperforming categories based on performance feedback from the previous stage and (2) a Progressive Intensity Adaptation (PIA) strategy, which systematically increases photometric augmentation intensity along a predefined schedule to explore the model’s maximal invariance to appearance changes. Finally, as a direct extension of the CSSP philosophy to address the third challenge, we propose a Cross-Domain CSSP (CDCSSP), a novel framework tailored for the SSDA task.

The main contributions of this work are three-fold:

- (1)

- We propose a CSSP, a stable, curriculum-based training paradigm for large ViT-based models for RSI SSSS. Through a structured four-stage pipeline, the CSSP systematically addresses the critical issues of overfitting and training instability under limited annotations.

- (2)

- Within the CSSP framework, we design and validate two key innovative components, the DA-ClassMix augmentation and the PIA strategy, which regulate data complexity progression from geometric-semantic and photometric perspectives, respectively.

- (3)

- By extending the CSSP’s core design, we propose a CDCSSP for the SSDA task. Experiments demonstrate that the CDCSSP achieves significant performance improvements over state-of-the-art (SoTA) UDA and SSDA methods, confirming the effectiveness and generalizability of our proposed training paradigm.

2. Related Works

2.1. Methods for RSI SSSS

Existing works in RSI SSSS have largely adapted SSL methods, which are predominantly categorized into self-training and consistency regularization approaches.

Self-training methods leverage a model’s own predictions on unlabeled data as pseudo-labels to augment the training set. A core challenge is managing noise in these pseudo-labels. Common strategies involve designing flexible filtering schemes to select reliable regions based on confidence scores [11,12] or prediction entropy [13]. Some works introduce auxiliary networks to assess pseudo-label reliability [14,15] or utilize low-level image cues for refinement [16,17,18]. Other approaches mitigate labeling errors by re-weighting pseudo-labeled pixels in the loss function [19,20].

Consistency regularization methods enforce prediction consistency by applying perturbations to a student network while using an unperturbed teacher network’s output as targets. As summarized in Table 1, dominant methods for RSI SSSS are adaptations of classical SSL frameworks like MT, FixMatch, CPS, and Cross-Consistency Training (CCT), leading to numerous derived works. Recent improvements to these frameworks include adding independent decoders [21], injecting feature-level perturbations [22], and employing multi-way input augmentations [23] to strengthen consistency constraints. Some efforts have also explored extending the teacher–student setup to multiple teachers or students [24,25,26,27,28].

Table 1.

Several classical SSL frameworks and their derived works for RSI semantic segmentation.

Data augmentation serves as the primary source of perturbation in consistency regularization. Techniques like CutMix [8] and ClassMix [45] have proven highly effective [30,33,39,40]. Some works have also constructed new intensity-based augmentation strategies [46] or hierarchical augmentation schemes [47] to expand the perturbation space. However, a prevalent limitation is the use of a static augmentation policy fixed throughout training, which fails to adapt to the model’s evolving learning state and cannot systematically maximize generalization.

Beyond these two dominant methods, representation learning has been integrated into SSL to enhance the encoder’s feature representation capability, thereby indirectly reducing dependency on annotations. Methods in this line often apply contrastive learning on either labeled [48] or unlabeled data [27,34,35,36,37,47,49,50,51]. However, the joint optimization of representation learning and SSL objectives is sub-optimal. The effectiveness of contrastive learning can be compromised by noisy pseudo-labels, while an under-trained feature representation can, in turn, corrupt pseudo-label generation, creating a detrimental cycle that hinders performance. The method in [52] attempts to decouple this process by first conducting self-supervised learning to enhance representation, followed by a separate SSL stage, which can avoid mutual interference. However, it lacks methodological guidance on how to configure data augmentation across the two stages. Our proposed CSSP extends the idea of stage-wise separation between self-supervised representation learning and SSL. We introduce a more refined four-stage pipeline that systematically regulates the type and timing of introduced data augmentations, enabling a structured and effective learning progression that leads to breakthrough performance.

2.2. ViT-Based Methods for RSI SSSS

Previous research on RSI SSSS predominantly employed CNN-based models like the Deeplab series [53,54] with ResNet backbones [55]. We find that classical SSL methods exhibit significant training instability when directly applied to large-scale ViT-based segmentation models (see Section 4.4.1).

A growing number of studies have employed ViTs as the backbone network. It is important to note that the primary contribution of these works lies in advancing the semi-supervised methodology itself, with ViT serving as a powerful feature extractor for validation, rather than explicitly aiming to solve ViT-specific training challenges. For instance, DWL [56] and MUCA [57] employ small-scale SegFormer-B2 (approximately 27M parameters), whose capacity is comparable to CNNs, thereby circumventing core optimization challenges.

Studies using a swin transformer [58,59,60] train the model in a conservative way, generating high-quality offline pseudo-labels from a teacher model first trained on limited labels. This avoids the online, noisy teacher–student dynamics that can cause collapse in frameworks like CPS or MT. However, the distribution matching module in DAST [58] inherently limits its suitability for advanced geometric augmentations, as such augmentations can significantly alter class ratio distributions. Notably, a study in [60] observes that the training stability of large ViTs is acutely sensitive to data augmentation configurations, which remains an unresolved issue. Consequently, these methods often fail to leverage advanced augmentations in later stages to push generalization boundaries.

In summary, there is a lack of a systematic training paradigm specifically designed for RSI SSSS with large ViTs. Such a paradigm would enhance training stability by reducing sensitivity to model capacity and data augmentation, thereby making the optimization process more controllable and robust. In contrast to prior works that circumvent or mitigate the instability, our CSSP provides a dedicated paradigm to systematically resolve it.

2.3. Curriculum Learning for RSI SSSS

The core idea of curriculum learning [61]—progressing from easy to hard—has been implicitly incorporated into self-training methods. This integration primarily manifests in two ways:

The first is a curriculum at the data-selection level, where the criteria for utilizing pseudo-labels are progressively relaxed. For instance, some studies [23,46,57,62] start by utilizing high-confidence pseudo-labels and use a predefined threshold decay schedule to incorporate more challenging samples as training proceeds. Methods in [51,63,64] dynamically and adaptively adjust the confidence threshold per category based on its current learning difficulty, enabling class-wise curriculum control. Furthermore, iterative self-training pipelines [11,65,66,67] that generate reliable offline pseudo-labels for a subsequent training stage inherently embody a multi-stage curriculum.

The second is a curriculum at the training-objective level. The training focus is gradually shifted from labeled to unlabeled data. This is achieved by increasing the weight of the unsupervised loss component throughout training [68,69] or by dynamically adjusting the weight of each pseudo-labeled pixel in the loss function [19,56].

However, these existing methods typically implement only a unidimensional curriculum, focusing on either sample difficulty or loss re-weighting. In contrast, our proposed CSSP implements a stage-wise, dual-dimensional curriculum that regulates the co-evolution of model capacity and data complexity. This holistic design allows for finer control over the training dynamics and leads to a more interpretable and robust learning process.

2.4. Domain Adaptive Semantic Segmentation

Numerous studies have been conducted on semantic segmentation for RSIs using UDA. These studies primarily adopt adaptation methods at the input level, feature level, or output level. For instance, CycleGAN [70] is a widely used input-level method that translates source images into target-style appearances. Feature-level [71] and output-level [72,73] methods typically employ adversarial training to indirectly align the feature distributions or output space distributions between the two domains. FLDA-Net [17] further integrates multiple adaptation strategies to form a full-level adaptation approach. However, distribution alignment at the feature or output level often lacks guidance from target domain labels, leading to distribution mismatch within the same category, which severely limits the performance of UDA methods.

SSDA has emerged as a promising setting to overcome the limitations of UDA by incorporating a small number of labeled samples in the target domain. Several attempts [74,75,76,77] have demonstrated significant improvements over UDA methods. For example, TCM [74] proposes a two-stage SSDA framework, where the first stage finetunes a source-pretrained model on the labeled target data, and the second stage adopts MT exclusively on target domain data. PCLMB [78] extends its proposed SSL method to the SSDA setting and proves its effectiveness.

However, SSDA for RSI segmentation remains significantly underexplored compared to UDA. This is not because of its inherent difficulty but likely because the field’s focus has been predominantly captured by the more challenging goal of purely unsupervised adaptation, coupled with a lack of standardized benchmarks for the SSDA setting. The method in [79] proposes cross-domain multi-prototypes to handle large inter-domain discrepancies and intra-domain variations common in RSIs, yet the joint optimization of six loss functions leads to training difficulties in weight balancing, and multiple losses are susceptible to errors in pseudo-labels. ABSNet [80] incorporates active learning to maximize the annotation informativeness of the selected target domain super-pixels and trains a model biased towards target domain by re-weighting source samples in the loss function. However, neither approach is compatible with strong data augmentation strategies, as introducing complex augmentations risks disrupting the stability of category prototypes or the reliability of source sample weighting. In contrast, our CDCSSP framework enables more flexible incorporation of strong augmentations while ensuring controllable training stability.

3. Method

This section first introduces the proposed CSSP method for the SSSS task. Then we describe its extension, the CDCSSP method, designed for the SSDA setting.

3.1. CSSP for RSI SSSS

3.1.1. Overall Framework

A dataset is considered in SSSS, where denotes the labeled subset and represents the unlabeled subset. Each labeled image is a tensor of spatial dimensions with three color channels, and its corresponding ground truth is a semantic map with classes. The i-th image in the unlabeled dataset is denoted as . and represent the number of labeled and unlabeled samples, respectively. Most SSL methods train the model in an end-to-end manner with the loss function formulated as

where denotes the supervised loss—typically implemented as the standard cross-entropy loss—and represents the unsupervised loss, weighted by hyper-parameter . However, when several classical SSL methods are applied in an end-to-end manner to train large ViT-based segmentation networks with limited annotations, they often suffer from performance degradation or training instability (see Section 4.4.1). This instability stems from multiple interacting factors, including the initialization of the ViT backbone, the capacity of each component in a segmentation model, the type and intensity of data augmentation perturbations, and the parameter coupling relationship in a teacher–student framework. Given the number of factors that influence training stability, we propose to decompose the learning process into a staged pipeline. By introducing and calibrating these factors progressively, our pipeline aims to ensure a more controllable and stable training trajectory, while also enhancing the interpretability of the optimization process.

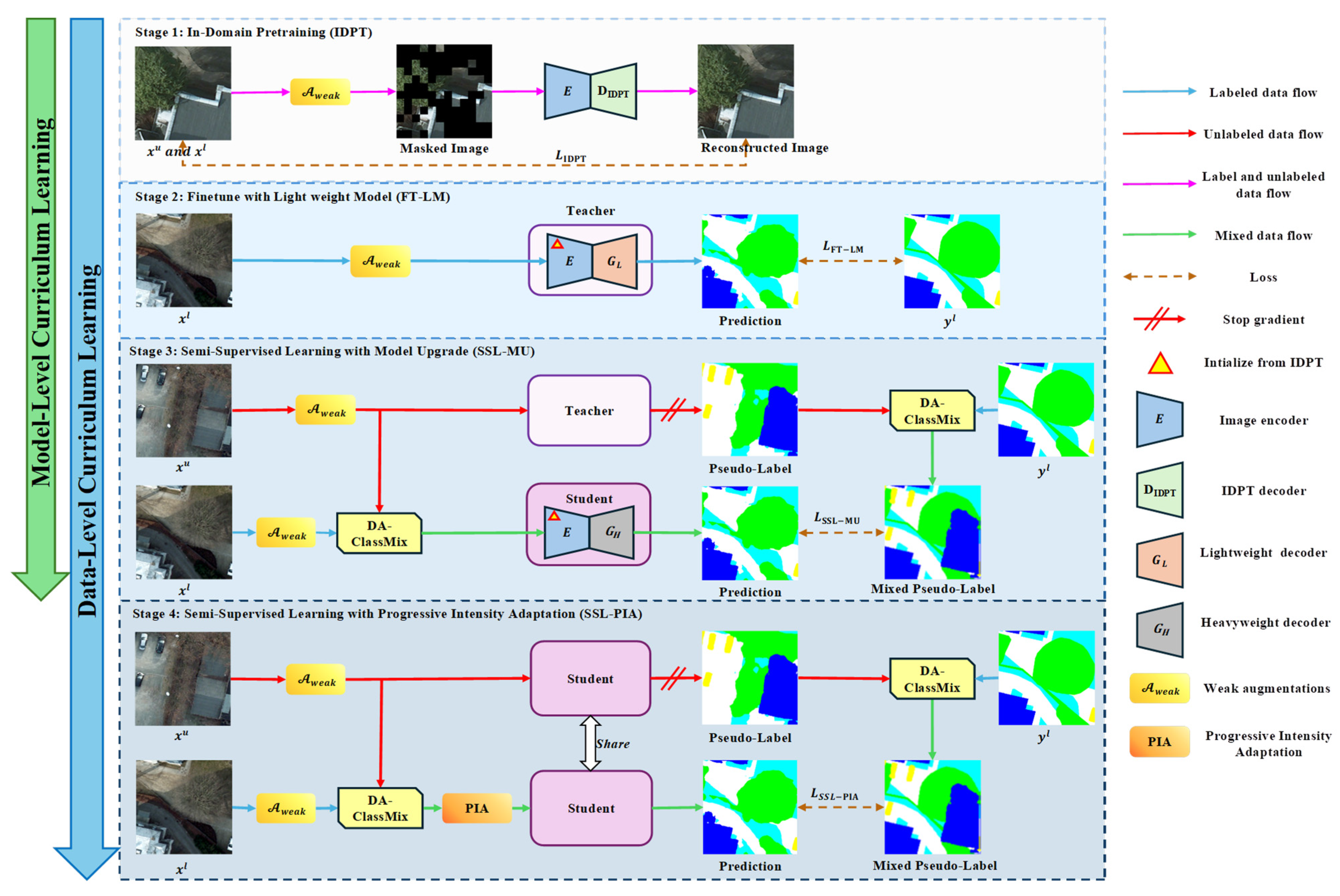

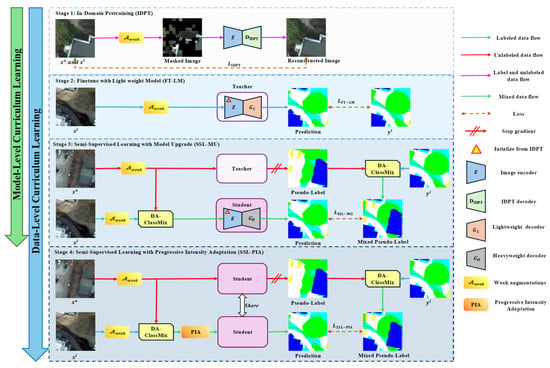

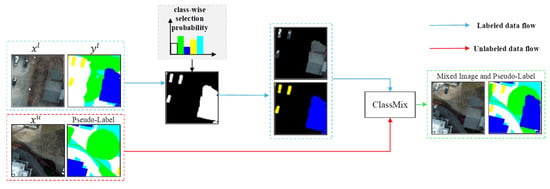

Inspired by curriculum learning principles, we decompose the optimization process into a series of more manageable sub-tasks, where earlier stages facilitate the training of subsequent ones. An overview of the proposed CSSP is illustrated in Figure 1. The overall training pipeline comprises four sequential stages, with the first two dedicated to constructing a high-quality initial teacher network using labeled data and the latter two focused on semi-supervised training of the final segmentation model. Our pipeline incorporates both a model-level curriculum that spans across the supervised and semi-supervised phases and a complementary data-level curriculum that progressively increases augmentation complexity.

Figure 1.

An overview of the CSSP. The framework comprises four sequential stages: (1) In-Domain Pretraining (IDPT) of the backbone encoder; (2) Supervised finetuning of a teacher network with a lightweight decoder (FT-LM); (3) Semi-supervised Learning with a Model Upgrade (SSL-MU), featuring the proposed DA-ClassMix augmentation; (4) Semi-supervised Learning with Progressive Intensity Adaptation (SSL-PIA) to systematically enhance model robustness.

A critical motivation is to establish a robust teacher model capable of generating accurate pseudo-labels before commencing SSL, thereby mitigating error propagation. The process begins with self-supervised pretraining of the ViT backbone (stage 1), followed by supervised finetuning to obtain the initial teacher. Our model-level curriculum starts from stage 2: we intentionally employ a lightweight decoder for the teacher network, using only in-domain data and weak augmentations. This constrained design prevents overfitting under extreme label scarcity and yields a stable, high-quality pseudo-label generator.

The core semi-supervised curriculum then unfolds across stage 3 and stage 4, advancing both the model and data complexities. In stage 3, the model-level curriculum progresses: the student network is upgraded to a heavyweight decoder, representing a deliberate capacity upgrade from the teacher. Concurrently, the data-level curriculum introduces its primary geometric-compositional challenge via the proposed DA-ClassMix. This operation not only blends semantic regions across images—forcing geometric-semantic invariance—but also prioritizes underperforming categories during mixing, thereby balancing the model’s learning progress across classes. The student is trained on these perturbed samples using pseudo-labels from the lightweight teacher.

Following the establishment of geometric robustness in stage 3, the data-level curriculum is enhanced in stage 4 by introducing a complementary challenge through PIA. While stage 3 focused on high-level geometric-semantic invariance, PIA is designed to systematically and progressively intensify low-level photometric perturbations (e.g., color jitter, and blur). This design is deliberate: intensity perturbations can be viewed as introducing continuous, directional noise in the feature space. The goal of PIA is thus to specifically tackle feature-level invariance to low-level photometric changes. By progressively intensifying this challenge after geometric robustness is acquired, the model is forced to discard superficial appearance cues and rely on more essential semantic features. This sequential design—first confronting geometric-semantic invariance (stage 3), then tackling extreme photometric invariance (stage 4)—ensures clear and separate learning objectives. It allows the model to first stably grasp “what and where” objects are, before learning “how they appear” under increasingly challenging appearance variations. This structured progression systematically expands the model’s robustness from the in-domain distribution to out-of-domain scenarios, thereby training a more generalizable final model.

3.1.2. In-Domain Pretraining and Finetuning

ViT-based models are characterized by a large number of parameters and a weak inherent inductive bias for RSIs. When labeled samples are scarce, the initial supervised training of the teacher model is highly susceptible to overfitting, which in turn compromises the quality of pseudo-labels produced for unlabeled data. In many practical scenarios, the scale of the target dataset is insufficient to enable ViT-based models to overcome their weak inductive bias for RSIs.

To address this limitation, we can introduce external RSI data at a significantly larger scale than , allowing the ViT-based backbone to first acquire general knowledge of RSIs. The backbone can then be adapted to learn domain-specific features from the target dataset, i.e., In-Domain Pretraining (IDPT). In this way, the ViT-based backbone learns robust feature representations from , and the overfitting problem of the teacher model is no longer simultaneously affected by its backbone and segmentation decoder. To this end, we employ a self-supervised pretraining strategy with two steps. Specifically, we pretrained the swinV2-B [6] backbone using the SimMIM algorithm [81] on a large-scale corpus of 2.3 million high-resolution RSIs. Then we perform IDPT on with the same algorithm and denote the pretrained backbone as *. It is worth noting that only weak data augmentations are applied during the IDPT stage. The overall loss function for this process is formulated as follows:

where denotes the L1 loss, represents the masked region of SimMIM for image , and is the number of pixels in that region. The transformation refers to weak data augmentations listed in Table 2, and denotes the image reconstruction decoder.

Table 2.

List of data augmentation methods used in our approach.

Following IDPT for the backbone, a teacher network is finetuned using the limited labeled data. While our final goal is to use a heavyweight segmentation decoder in the segmentation network for its stronger discriminative power, large number of parameters in the heavyweight decoder increase the risk of overfitting under limited labeled data. We therefore employ a lightweight network as the teacher’s decoder. The teacher network is denoted as . This finetuning stage with a lightweight teacher model is termed FT-LM.

When labeled data is too scarce for a lightweight decoder to suppress overfitting, we further incorporate label smoothing [82] to enhance training stability. Label smoothing replaces conventional one-hot labels with smoothed targets, where the ground-truth class is assigned a confidence value of 0.9, while the remaining classes uniformly share 0.1. The loss function for finetuning the teacher model is formulated as

where denotes cross-entropy loss and represents the label-smoothed version of . Unlike methods [27,34,35,36,47,49,50,59] that integrate representation learning as an auxiliary task within the semi-supervised training process, we decouple self-supervised representation learning into an independent stage. The key advantage of this decoupled design is that the representations acquired through self-supervised learning facilitate the generation of more accurate initial pseudo-labels, thereby effectively mitigating the risk of error propagation in the early stage of SSL training.

3.1.3. SSL with Model Upgrade

We employ a self-training strategy at this stage: the teacher network from the FT-LM stage (with its parameters frozen) generates pseudo-labels to supervise the training of a student network. As illustrated by the studies in Noisy Student [83] and CSST [84], when abundant pseudo-labels are available, segmentation decoders of different architectures show varying performance—reflecting their differing robustness to label noise. Motivated by this finding, we initialize the student’s encoder with the IDPT-trained backbone * and upgrade its decoder to a heavyweight and discriminative architecture . The student is denoted as . This model upgrade stage of the training is denoted as SSL-MU.

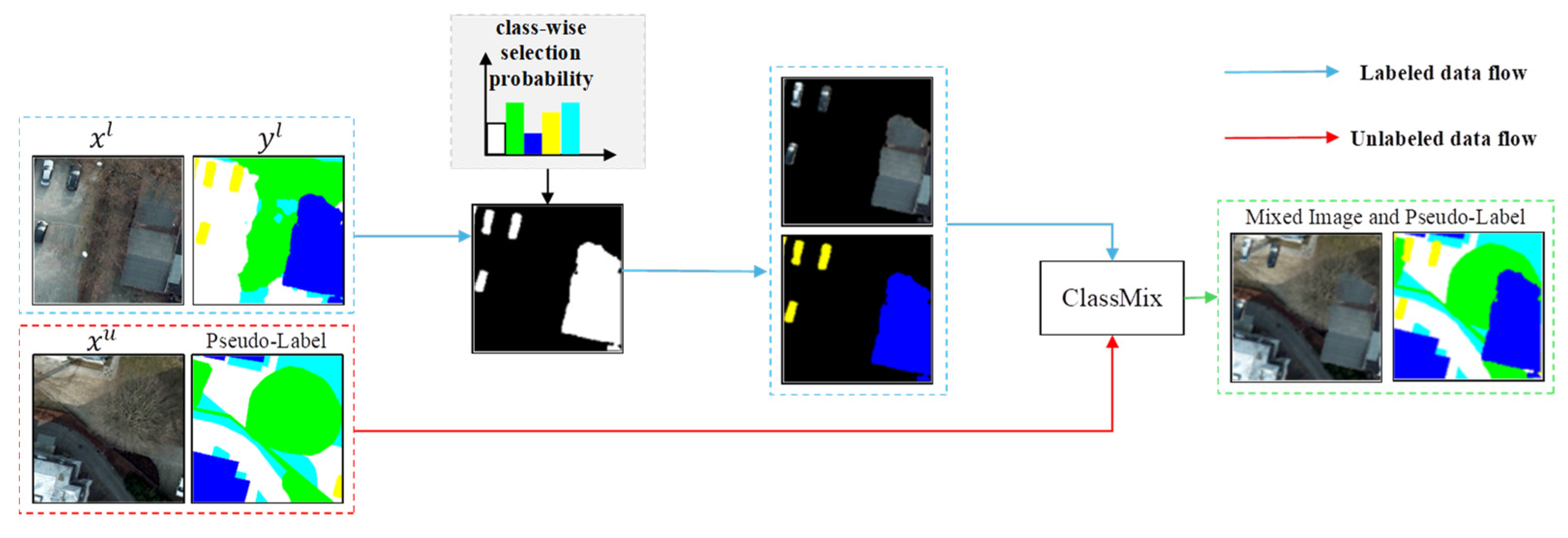

We now advance to the complementary data-level curriculum in stage 3. Its primary goal is to enforce geometric-semantic invariance, a fundamental robustness measure for semantic segmentation. To this end, we propose the DA-ClassMix—a novel augmentation strategy designed to address a key issue in SSL. Since the teacher model’s performance varies across different categories, the pseudo-labels it generates for underperforming classes are less reliable. DA-ClassMix mitigates this by prioritizing these difficult categories during the mixing process, thereby balancing the learning progress. As illustrated in Figure 2, DA-ClassMix incorporates two key design elements:

Figure 2.

Illustration of the proposed DA-ClassMix with adaptive probability sampling.

First, considering the inherent unreliability of pseudo-labels from unlabeled data, mixing two unlabeled samples via ClassMix may still yield unreliable mixed pseudo-labels. In contrast, labeled data offers trustworthy annotations. Therefore, DA-ClassMix performs mixing between labeled and unlabeled samples. This strategy not only enhances data diversity and learning difficulty but also yields more reliable mixed pseudo-labels, as the ground-truth annotations from the labeled data can cover a portion of the erroneous pseudo-labels from the unlabeled samples. The mixed image and pseudo-label of DA-ClassMix are generated as follows:

where is the pseudo-label of teacher model’s prediction, denotes the element-wise multiplication operator, and is a binary mask indicating DA-ClassMix that is modulated by class-wise difficulty. is described below as the second design element.

Second, in the standard ClassMix method, half of the classes (a fixed 50%) are randomly selected from the pseudo-labels of one image and copied to the pseudo-labels of another image. We modify this random selection strategy by sampling each category individually from a labeled image and pasting to an unlabeled image. This strategy increases the sampling probability for underperforming categories, thereby enhancing the learning accuracy for these challenging categories. The sample probability for each category is determined by its learning difficulty, which is characterized by the teacher model’s performance on the validation set in the FT-LM stage. Specifically, the learning difficulty for category is defined as , where denotes the F1-score of the -th category. The selection probability for class is then formulated as

This formula constrains the selection probability to the range [0.2, 0.5], where the class with the highest difficulty is assigned the maximum probability of 0.5, while the lowest selection probability remains above the 0.2 threshold.

In addition to improving pseudo-label reliability, the proposed DA-ClassMix method significantly reduces computational overhead compared to the standard ClassMix approach. This is particularly advantageous when training computationally expensive ViT networks. Specifically, while standard ClassMix requires four forward passes per batch (one for labeled data, two for unlabeled data, and one for mixed unlabeled data), DA-ClassMix reduces this to only two forward computations (one for unlabeled data and one for mixed data). During training, each batch contains an equal number of labeled and unlabeled images (batch size ) for DA-ClassMix, and the loss function for the SSL-MU stage is formulated as

In summary, DA-ClassMix serves as the cornerstone of the geometric challenge in our curriculum. By synthetically creating complex, out-of-context scenes, it compels the student model to develop a robust understanding of object semantics independent of their geometric surroundings. This establishes the essential foundation upon which the subsequent photometric challenge (PIA in stage 4) can be effectively built.

3.1.4. SSL with Progressive Intensity Adaptation

An appropriate intensity of data augmentation is beneficial for improving model performance in both supervised and semi-supervised training. When augmentation intensity is moderately increased, the resulting out-of-distribution samples effectively resemble images from distinct domains. Forcing the model to simultaneously adapt to the original data domain and these augmented domains strengthens its overall robustness. However, excessively strong augmentation can degrade performance [9]. Therefore, the optimal intensity of augmentation is difficult to preset, as it depends on the model architecture, dataset, specific task, and especially the learning state of the model.

To address this issue, we adopt a data-level curriculum training strategy termed PIA, which systematically increases the data augmentation intensity throughout the training process. We construct a data augmentation pool (see Table 2) comprising three categories: (1) weak augmentations based on simple geometric transformations, (2) strong geometric augmentations implemented using the proposed DA-ClassMix method, (3) strong intensity-based augmentations consisting of various transformations that alter image magnitude. We define a sequence of randomly selected strong intensity-based augmentations as representing augmentation intensity at Level , denoted as . Therefore, corresponds to the -fold composition of the base strong augmentation transformation , i.e.,

where denotes the function composition operator. It should be noted that we intentionally put an identity transformation in the augmentation pool, which allows the model to adapt to both the expanded and the original data domain during training.

In this stage, we maintain the teacher–student framework. Both the teacher and student network share the same architecture ( network mentioned before) and are initialized from the student model trained in the SSL-MU stage, thereby providing a strong starting point for training.

Building upon the geometric robustness established through the persistent use of DA-ClassMix in the previous stage, this stage introduces a secondary, progressive curriculum focused on photometric invariance. Within this dual-aspect design, DA-ClassMix serves as a constant, primary challenge for geometric-semantic robustness. On this stable foundation, the PIA strategy systematically intensifies a suite of low-level photometric augmentations. This compels the model to continuously learn invariance to complex scene compositions while simultaneously adapting to progressively more severe appearance variations.

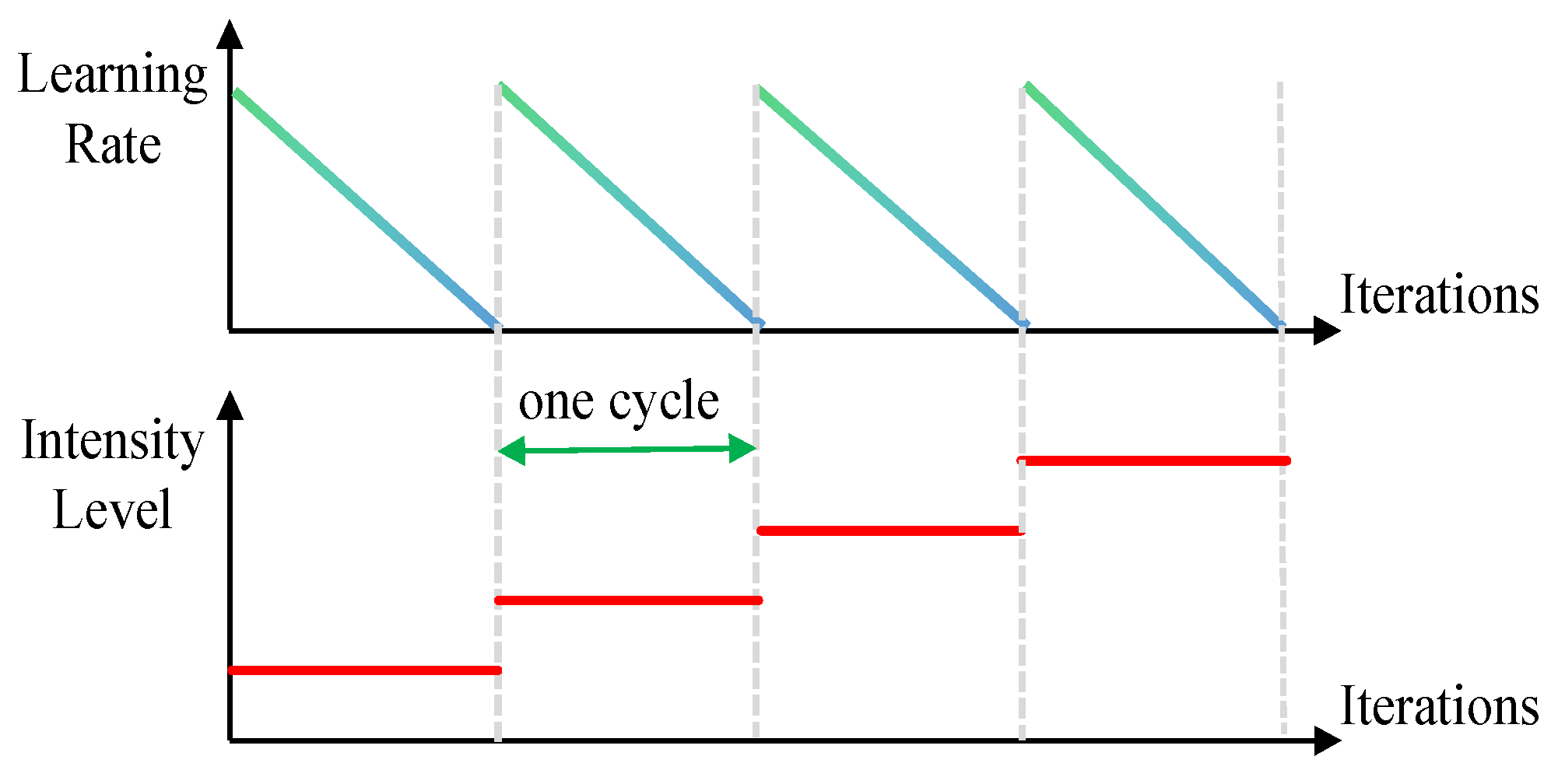

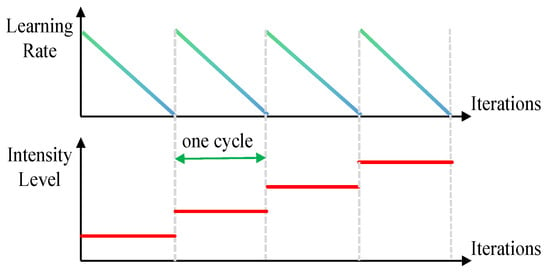

As is shown in Figure 3, the PIA strategy for the student network is organized into consecutive cycles, each spanning a fixed number of iterations. Within each cycle, the learning rate follows the same decay schedule, starting from a relatively high value and gradually decreasing. More importantly, the intensity of data augmentation is progressively raised across cycles: the -th cycle employs an intensity-based augmentation at Level , i.e., . This curriculum-style design allows the model to first adapt quickly to a new augmentation intensity while the learning rate is high, then consolidate its performance as the learning rate decays, before moving to a higher augmentation intensity in the next cycle. The process continues until the best validation performance begins to decline across cycles, which signals the optimal stopping point for training. Because this stage systematically integrates PIA into semi-supervised learning, we name it SSL-PIA.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the PIA strategy.

To determine the optimal teacher–student framework for the SSL-PIA stage, we evaluated three classical parameter coupling relations between the teacher and student network. Among them, a weight-sharing mechanism between the teacher and student achieved superior accuracy compared to the preceding stage and was therefore selected as the default configuration. A detailed comparative analysis of these frameworks is provided in Section 4.4.6. The loss function for the SSL-PIA stage is formulated as

where is the mixed pseudo-label, is the prediction of the student model, and the augmentation intensity increases progressively according to the proposed PIA strategy during training.

3.2. Extension to SSDA: The CDCSSP Pipeline

In this section, we can naturally extend the proposed CSSP method to the SSDA scenario, resulting in the CDCSSP.

In the SSDA setting, we assume access to a fully labeled source domain dataset, denoted as , along with a target domain dataset . The target dataset consists of a small labeled subset and a large unlabeled subset . This study focuses on a common setting where the label spaces of the source domain and the target domains are identical, i.e., . The following section briefly describes how our CSSP is adapted to the SSDA task.

We commence the training pipeline with a pretraining phase (stage 1). Leveraging a high-capacity ViT-based backbone, our method extends beyond conventional source-to-target domain adaptation. Instead, the backbone is designed to handle cross-domain features concurrently—that is, to learn representations that remain robust across both source and target domains. To achieve this, we adopt a joint training strategy on data from both domains, a stage referred to as Cross-Domain Pretraining (CDPT). The corresponding objective function is defined as follows:

where denotes the combined cross-domain dataset. All other symbols retain the same meanings as in Equation (2).

Following the CDPT stage, we proceed to stage 2: Cross-Domain Finetuning with a Lightweight Model (CDFT-LM). In this stage, a teacher model equipped with a lightweight decoder is finetuned in a cross-domain manner. Given the significant data imbalance between the labeled target domain dataset and the labeled source domain dataset (where ), we adopt a balanced training strategy. Each training batch contains an equal number of labeled samples from both domains, promoting balanced cross-domain learning and preventing the model from biasing toward the more abundantly annotated source domain. The corresponding loss function is defined as

where hard labels are used for the source domain data and label-smoothed soft labels are applied to the target domain to accommodate its limited annotation volume.

In stage 3, termed SSDA-MU, the fixed teacher network trained in the previous stage is employed to generate pseudo-labels for the student network. We perform DA-ClassMix using labeled source domain images and unlabeled target domain images , which effectively blends features across domains through geometric transformations. This inter-domain mixing encourages the student network to learn not only domain-specific features but also transitional representations in the feature space. The mixed samples are formulated as

where represents the pseudo-label generated by the teacher network. To maintain the cross-domain learning property in the student network, each training batch is constructed to contain an equal number of samples from both domains. The overall loss function for this stage is defined as

The proposed CDCSSP framework concludes with stage 3. We deliberately omit the PIA stage from the final cross-domain curriculum. While PIA proves effective for enhancing the model’s generalization capability, its integration into the cross-domain setting was found to compromise training stability. An empirical ablation study (see Appendix A) demonstrates that adding PIA as a final stage introduces significant performance fluctuation without reliable convergence gain. Therefore, to prioritize robustness in cross-domain adaptation, we maintain the presented three-stage CDCSSP as the finalized pipeline.

It should be noted that our CDCSSP does not incorporate an explicit domain knowledge transfer design, as the domain adaptation process and the cross-domain intra-class feature alignment are implicitly learned during stage 1 and stage 2, respectively.

4. Experiments and Analysis

Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4 focus on evaluating and analyzing our proposed CSSP core framework. In Section 4.5, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the CDCSSP framework under the SSDA scenario.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets

We selected three remote sensing datasets to verify the effectiveness of our method. Details for each dataset are listed below:

- (1)

- ISPRS Potsdam Dataset [85]: This benchmark comprises 38 high-resolution aerial images with a ground sampling distance (GSD) of 5 cm. We use 24 images for training and 14 for validation, utilizing only the RGB bands. The annotations follow a six-category scheme (impervious surfaces, buildings, low vegetation, trees, cars, and clutter), though the clutter category is excluded in both training and evaluation. All images are cropped into non-overlapping 512 × 512 patches, yielding 2904 training and 1694 validation patches.

- (2)

- ISPRS Vaihingen Dataset [85]: This dataset includes 16 training and 17 validation images with a GSD of 9 cm. Each image contains three spectral bands: near-infrared, red, and green. It uses the same six-class labeling scheme as Potsdam, and similarly, the clutter category is omitted in our experiments. Images are divided into non-overlapping 512 × 512 patches, resulting in 210 training and 249 validation samples.

- (3)

- Inria Aerial Image Labeling Dataset [86]: This dataset addresses a binary segmentation task, distinguishing between “building” and “not building” classes. A labeled subset of 180 images is used in our experiments. Each image has a size of 5000 × 5000 pixels and a GSD of 0.3 m. The subset covers five geographic regions: Austin, Chicago, Kitsap County, western Tyrol, and Vienna. Following the data partition in [44], we use images with IDs 1–5 from each region for validation and the remaining images for training, resulting in 155 training and 25 validation images. All images are cropped into non-overlapping 512 × 512 patches, yielding 12,555 training and 2025 validation samples.

4.1.2. Implementation Details

We employed swinV2-B as the ViT-based encoder. For the teacher model, a lightweight two-layer fully convolutional network (FCN) served as the decoder. For the student model, we adopted UPerNet [7] as the decoder. All experiments were conducted on NVIDIA Tesla V100 32GB GPUs (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), using four GPUs during the IDPT stage and one GPU for all subsequent stages. The software environment was configured with CUDA 11.3 and PyTorch 1.12.1.

During the IDPT stage, we used a batch size of 512 and optimized the model with AdamW, setting the learning rate to 0.0001, , , momentum = 0.9, and a weight decay equal to 0.05. To ensure sufficient pretraining, we applied different numbers of epochs for each dataset: 200 for Potsdam, 800 for Vaihingen, and 30 for Inria.

In the FT-LM and SSL-MU stage, we trained for 80 k iterations in each stage with a batch size of 2. The SwinV2-B backbone was optimized using AdamW with a learning rate of 1.95 × 10−5, a weight decay of 0.05, and a cosine annealing learning rate schedule. The segmentation decoder was trained with SGD, using a momentum of 0.9, a weight decay of 5 × 10−4, and a linear learning rate scheduler that decays from 0.01 to 0.

In the SSL-PIA stage, we trained the final 80 k iterations with a batch size of 2. The same optimizer configurations were applied as in the FT-LM and SSL-MU stages. The main difference was that the learning rate was adjusted according to the PIA strategy, and the max learning rate in each cycle was set the same as the previous stage.

4.1.3. Metrics

We evaluated the Intersection over Union (IoU) and F1-score (F1) of each category for semantic segmentation prediction. And the mean IoU (mIoU) and mean F1 (mF1) for all the categories were used for the overall performance of each method. The mIoU and mF1 are formulated as

where , , and denote the number of true positive, false positive, and false negative samples for the -th category, respectively. And and represent the precision and recall of segmentation models for the -th category.

4.2. Comprehensive Evaluation of CSSP

(1) Results on the Potsdam dataset: To evaluate the performance of our method under extreme label-scarcity conditions, we trained the swinV2-UPerNet model using only 1/32 of the annotated data from the Potsdam dataset. As shown in Table 3, the proposed CSSP achieved an mIoU of 82.16%, significantly outperforming the supervised baseline trained on the same 1/32 of labeled data by 4.82% and narrowing the performance gap with the fully supervised upper bound to just 0.08%. Furthermore, it surpassed the supervised model trained on half of the labeled data by 0.90% in the mIoU. To our knowledge, this result represents a pioneering achievement in RSI SSSS, demonstrating near-full-supervision performance with an exceptionally small fraction of labeled data. Moreover, our method slightly outperformed the fully supervised DeeplabV3+ [54] with a ResNet-50 backbone by 0.09% mIoU.

Table 3.

Performances on the Potsdam validation set. “Sup” stands for the supervised learning method. All values are reported in percentage (%).

(2) Results on the Vaihingen dataset: Due to the limited size of the Vaihingen dataset, we used one-quarter of the annotated data for training. As shown in Table 4, the CSSP achieved a remarkable mIoU of 75.56%. This result not only significantly surpasses the supervised baseline by 6.85% but also exceeds the performance of the fully supervised counterpart by 0.99%. Moreover, our method slightly outperforms the fully supervised DeeplabV3+ model by 0.06%. This demonstrates, for the first time, that a semi-supervised approach with only 1/4 of the annotated labels can achieve a performance superior to that of fully supervised methods on the Vaihingen dataset.

Table 4.

Performances on the Vaihingen validation set.

(3) Results on the Inria dataset: Following the experimental setup of prior studies [30,33], we trained our model using 1/10 of the labeled data from the Inria training dataset. As shown in Table 5, the final model attained an IoU of 76.03%. This result significantly surpasses the supervised baseline by 2.63% and narrows the gap to the fully supervised model (76.15% IoU) to merely 0.12%. Furthermore, it exceeds the fully supervised DeeplabV3+ by 0.56%.

Table 5.

Performances on the Inria validation set.

In all cases, the CSSP achieved a performance that approaches or even surpasses fully supervised results, despite using only a small fraction of annotated data. It is noteworthy that the fully supervised swinV2-UPerNet model outperforms DeeplabV3+ on the Potsdam and Inria datasets but underperforms on the Vaihingen dataset. This discrepancy may be explained by the larger volume of annotations available in the Potsdam and Inria datasets, which helps alleviate inherent limitations of ViT-based models—such as their large parameter count and weaker inductive bias for images. These results reinforce the observation that ViTs for segmentation tasks require substantial annotated data to reach their full potential under supervised training.

The above results demonstrate the effectiveness of our CSSP framework across multiple datasets and under extreme label scarcity. In the following section, we further evaluate its competitiveness by comparing it with existing SoTA methods.

4.3. Comparison with SoTA Methods

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed CSSP method, we conducted comparisons on the Potsdam and Inria datasets against leading SSL methods from two key perspectives: ViT-based methods and CNN-based methods. For ViT-based comparison, we benchmarked against DAST [58]—which utilizes the same large SwinV2-UPerNet backbone—as well as DWL [56] and MUCA [57], two methods implemented on the small SegFormer-B2 architecture (with a parameter count comparable to ResNet-50). We also compared against several established CNN-based benchmarks (ClassMix, MT, CPS, ST++ [62], and LPCR [34]) built upon the DeeplabV3+ with a ResNet-50 backbone.

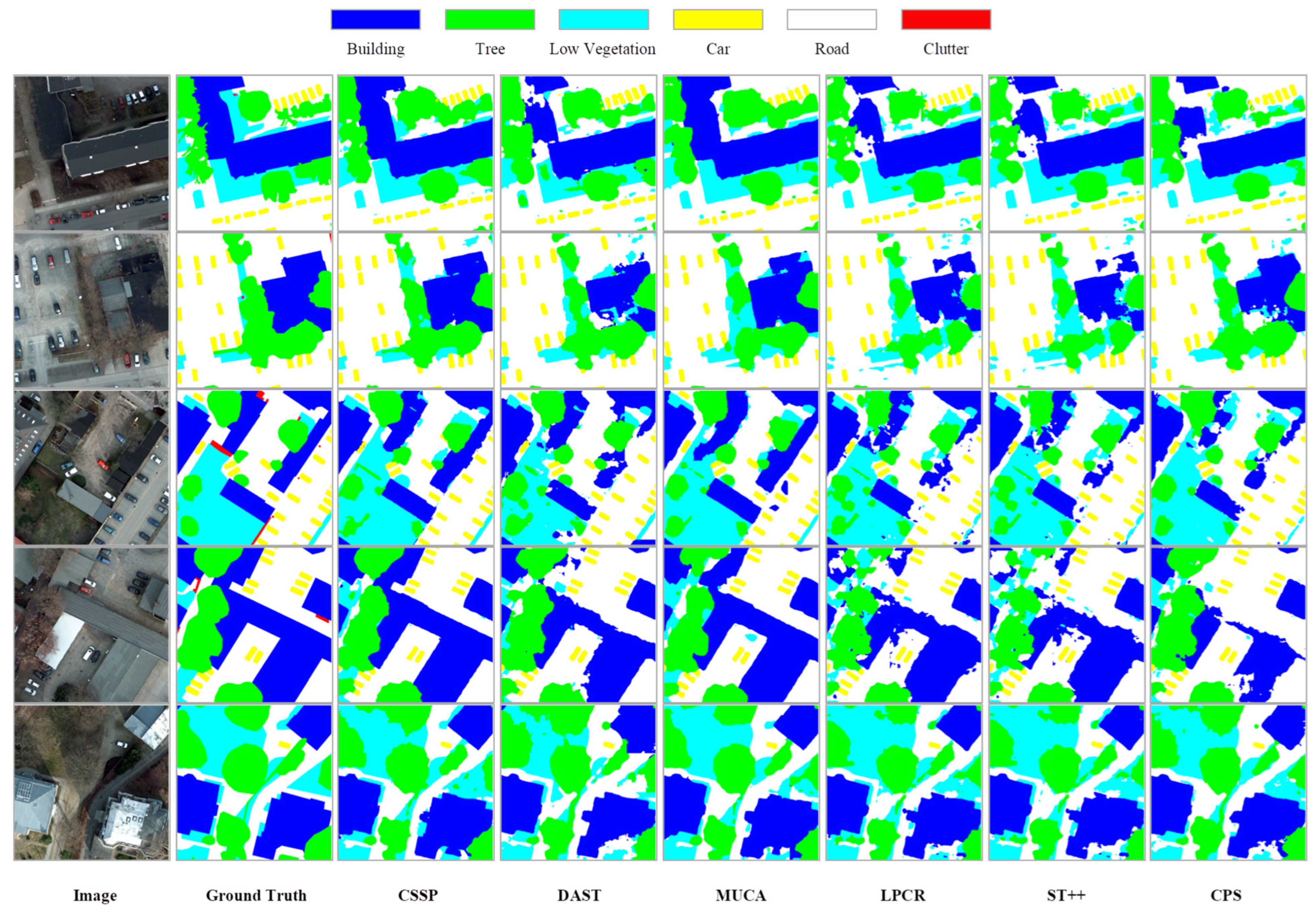

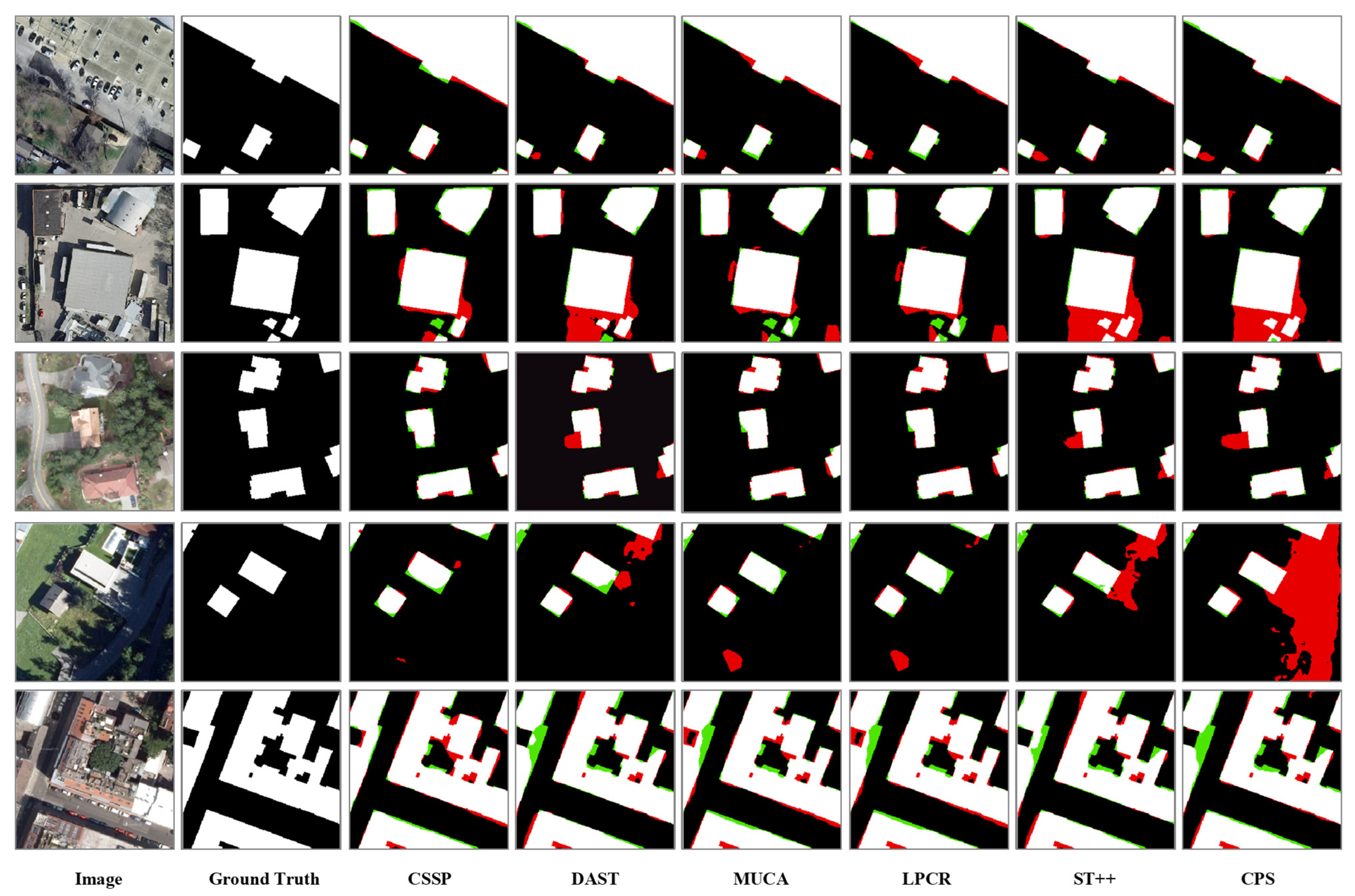

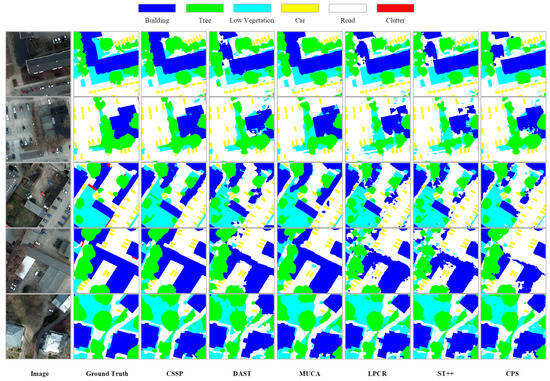

(1) Results on the Potsdam dataset with 1/32 label ratio: As shown in Table 6, our CSSP achieves a leading mIoU of 82.16%, demonstrating clear advantages. It significantly outperforms all CNN-based benchmarks, confirming the superior potential of a properly trained large ViT. Moreover, the CSSP also surpasses DWL and MUCA using SegFormer-B2. Notably, in comparison with DAST—the only method using identical SwinV2-UPerNet architecture—the CSSP achieves an improvement of 1.58% in mIoU, which validates the unique effectiveness of our proposed curriculum learning strategy in stabilizing training and fully unleashing the potential of large ViTs under extreme label scarcity. Qualitative results in Figure 4 further illustrate that predictions from our CSSP are visually closest to the ground truth, exhibiting finer details and more accurate boundaries.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of SoTA SSSS methods on Potsdam validation set under 1/32 label ratio. The best results are highlighted in bold.

Figure 4.

Quantitative results of different SSSS methods on Potsdam validation set.

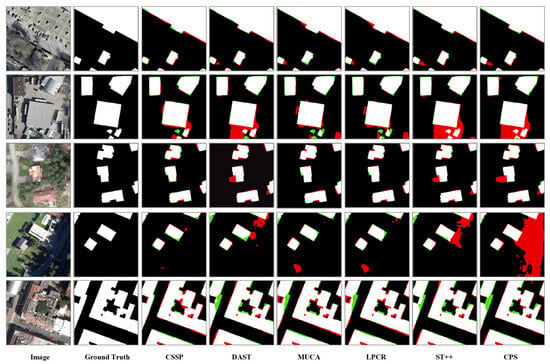

(2) Results on the Inria dataset with 1/10 labeled data: The quantitative results are summarized in Table 7. The proposed CSSP method achieves the highest performance, a finding consistent with the observations on the Potsdam dataset. Qualitative comparisons are provided in Figure 5. The CSSP generates segmentation masks with significantly fewer false positive errors (marked in red), especially around building boundaries and adjacent complex areas such as shadows and roads. This indicates the CSSP’s superior robustness against typical visual distractions in remote sensing imagery, which stems from the effective integration of the DA-ClassMix for geometric-semantic robustness and the PIA strategy for photometric robustness.

Table 7.

Performance comparison of SoTA SSSS methods on Inria dataset under 1/10 label ratio. The best results are highlighted in bold.

Figure 5.

Quantitative comparison of different SSSS methods on the Inria validation set (1/10 labeling ratio). Pixels are color-coded as follows: white, True Positives; black, True Negatives; red, False Positives; green, False Negatives.

4.4. Ablation Studies on CSSP

To evaluate the individual contribution of each proposed component, we conducted an ablation study on the Potsdam dataset. All experiments in this section are based on the swinV2-UPerNet architecture, where 1/32 of the training set is used as labeled data and the remaining portion as unlabeled data.

4.4.1. Revealing the Spectrum of Stability Needs

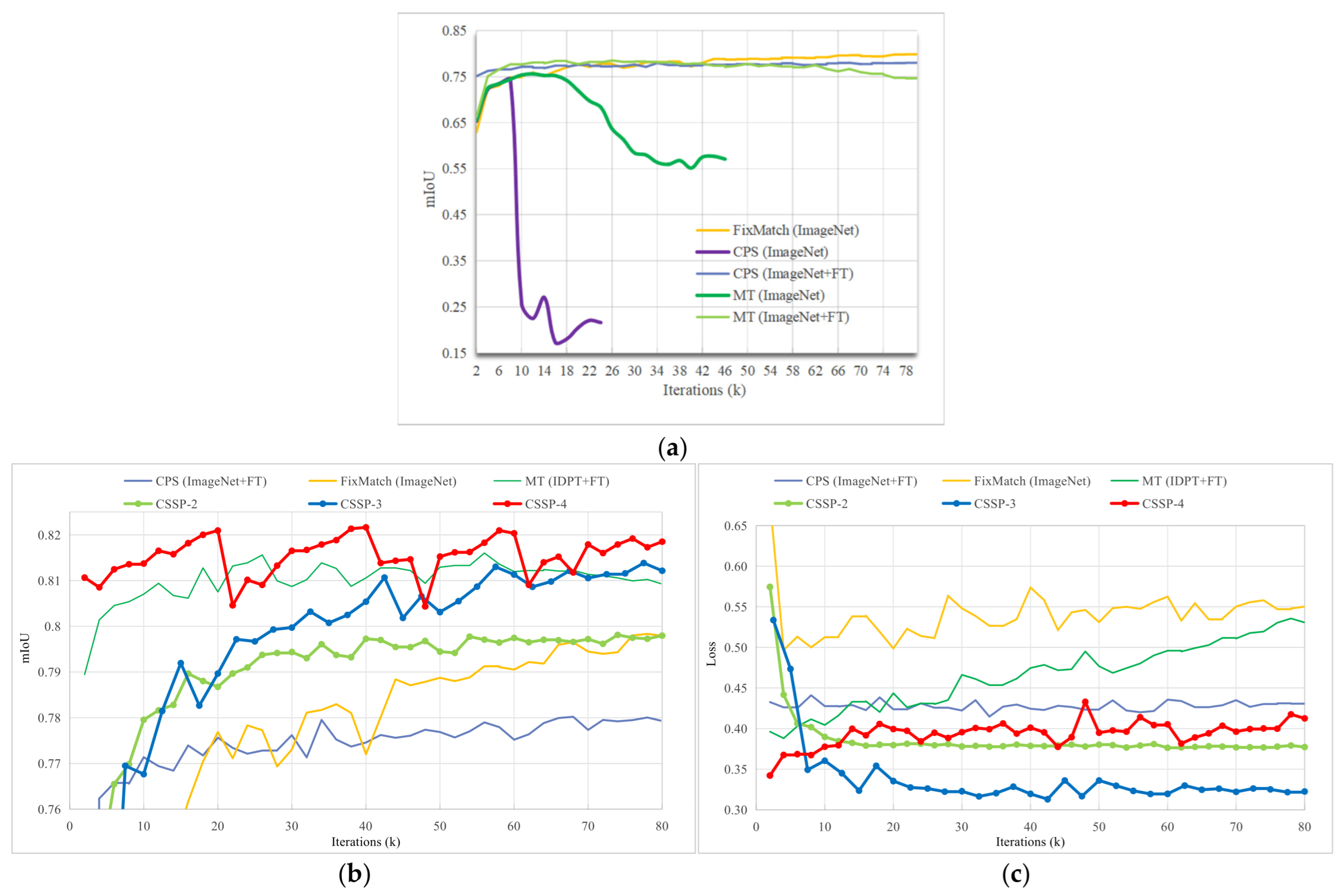

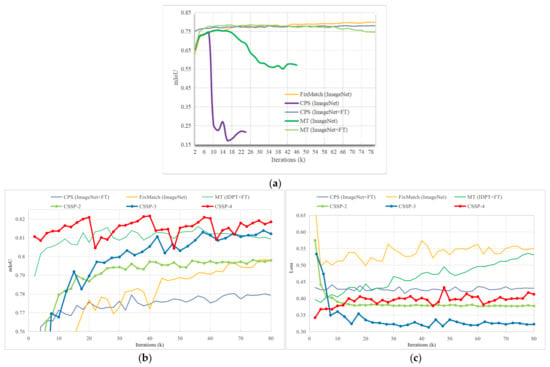

We evaluated several classical SSL methods—including FixMatch, CPS, and MT—on the swinV2-UPerNet model initialized with ImageNet [87] weights. The results, illustrated by the mIoU trajectories in Figure 6a, reveal a distinct spectrum of stability requirements when applying these frameworks to large ViT-based segmentation models. Specifically, FixMatch demonstrated stable training behavior and reliable convergence, representing a low demand for specialized stabilization. In contrast, the CPS method required a more stringent initialization condition: it necessitated a carefully finetuned model (e.g., after 80 k iterations of supervised finetuning) for both branches of networks to ensure convergence, otherwise it led to complete training failure. Most notably, the MT framework exhibited the highest stability demand, suffering from performance degradation even with carefully finetuned initialization.

Figure 6.

Comparison of training dynamics for different SSL methods on the Potsdam validation set using SwinV2-UPerNet with 1/32 labeled data. (a) mIoU curves of classic SSL methods; (b) mIoU curves of the proposed CSSP method, with other methods shown as references; (c) validation loss curves of the proposed CSSP method, with other methods shown as references.

As shown in Table 8, compared to the supervised baseline (mIoU: 77.34%), FixMatch and CPS with finetuning achieved mIoU gains of 2.49% and 0.68%, respectively, whereas MT resulted in a drastic performance drop to 74.53% mIoU. This spectrum clearly indicates that directly transplanting classical SSL frameworks to large ViTs carries inherent risks, with the severity contingent on the specific method. Consequently, for high-stability-demand methods like MT, a stabilization strategy more robust than traditional finetuning is critically needed.

Table 8.

Performance comparison between different classical SSL methods under different initial weights on Potsdam validation set.

4.4.2. The Role of IDPT

A comparative experiment demonstrates that IDPT fulfills two critical roles. First, it acts as an essential stabilizer for classical SSL methods with high-stability demands, such as MT, directly addressing the problem outlined in Section 4.4.1. Applying IDPT to the MT method effectively stabilized its otherwise unstable training process (see Figure 6b,c), resulting in a remarkable mIoU of 81.60%. This represents a substantial improvement of 7.07% over the MT model initialized with ImageNet weights (see Table 8). The stark contrast confirms that IDPT provides a robust, in-domain feature prior that is lacking in generic ImageNet pretraining, thereby solving the high-stability-demand problem.

Second, IDPT serves as a superior foundation that elevates overall learning performance. In a purely supervised setting, the model with IDPT achieved an mIoU of 78.58%. This performance not only surpassed the ImageNet-initialized supervised baseline by 1.24% but also exceeded that of the CPS method by 0.56%. Therefore, IDPT serves as the cornerstone of our CSSP. It ensures the model begins learning from a high, stable plateau of domain-specific representation, thereby creating a reliable foundation for addressing a more complex semi-supervised curriculum.

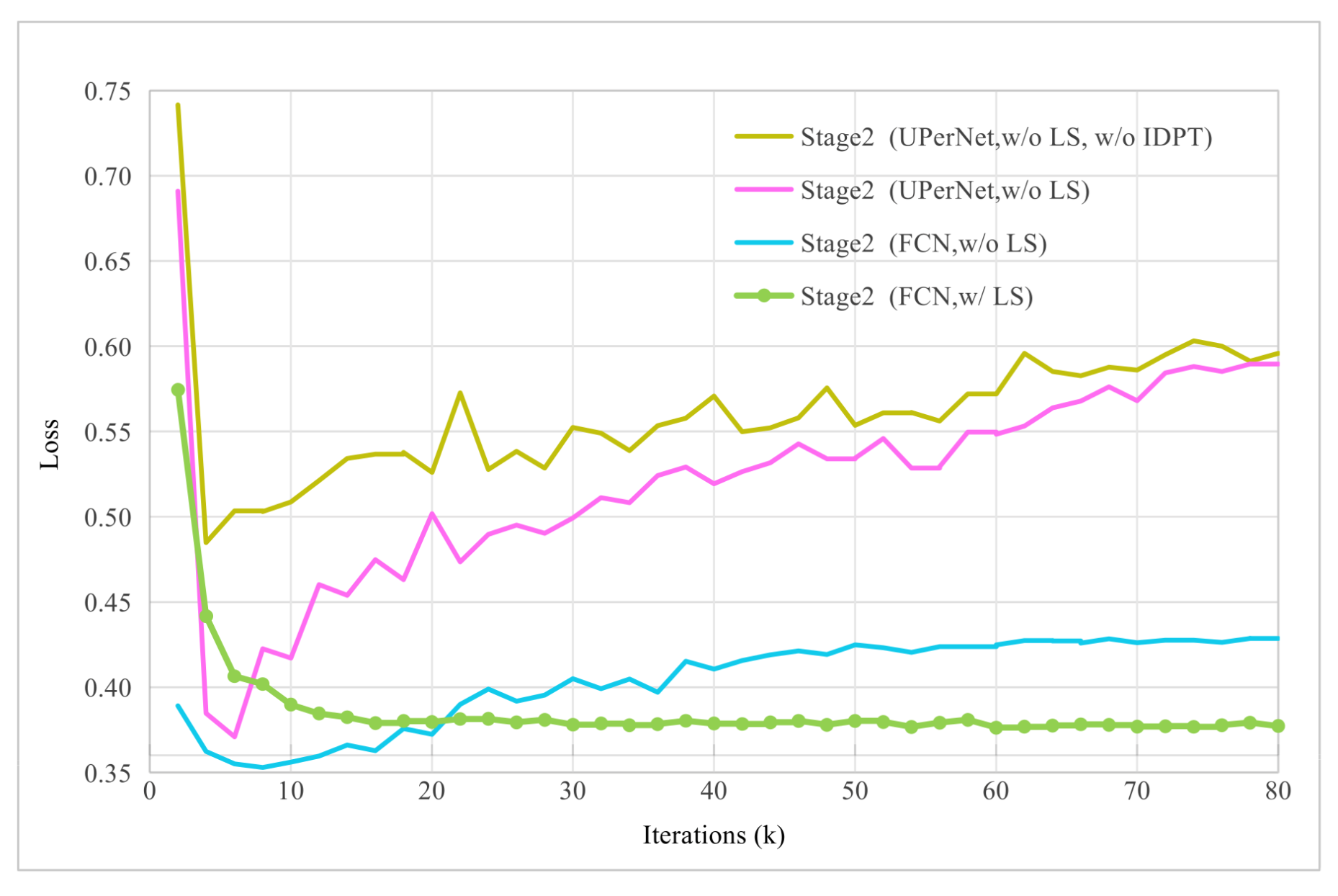

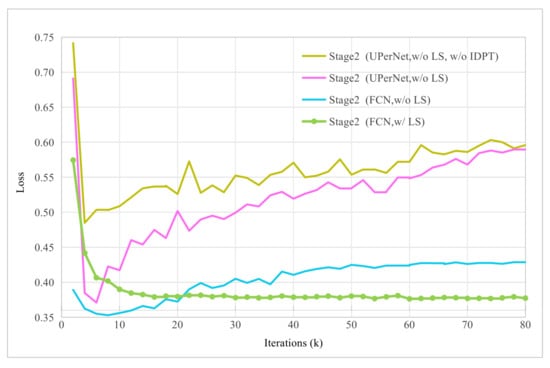

4.4.3. The Role of the Lightweight Decoder and Label Smoothing in FT-LM

Based on the findings from Section 4.4.2, all models in this experiment were initialized with IDPT-pretrained weights. We compared a heavyweight UPerNet decoder with a lightweight FCN decoder during the FT-LM stage and further evaluated the effect of using one-hot labels versus smooth labels. The results are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Performance comparison of different decoders and label smoothing strategies.

Replacing UPerNet with the lightweight FCN led to a notable improvement, increasing the mIoU by 0.73% (from 78.58% to 79.31%) and reducing validation loss from 0.5018 to 0.4106. These results indicate a significant suppression of overfitting. Furthermore, when label smoothing was applied in conjunction with the FCN decoder, overfitting was further alleviated, enabling more stable model convergence. This combination yielded an additional mIoU gain of 0.50%, achieving a final mIoU of 79.81% along with a further reduction in validation loss (0.3768). These experimental results demonstrate that combining a lightweight decoder with label smoothing effectively mitigates overfitting and substantially enhances the performance of the teacher model. The effectiveness of this combination is further illustrated in Figure 7, which plots the validation loss curves throughout the FT-LM stage. As shown, the configuration employing both the lightweight FCN decoder and label smoothing (green curve) achieves the lowest and most stable loss, confirming its role in establishing a robust foundation for the subsequent semi-supervised curriculum.

Figure 7.

Validation loss curves of different configurations during the FT-LM stage (stage 2), comparing FCN vs. UPerNet decoders with/without label smoothing (LS). The curves demonstrate that employing a lightweight FCN decoder significantly reduces and stabilizes the validation loss compared to a heavyweight UPerNet, indicating effective overfitting suppression. The addition of Label Smoothing further lowers and stabilizes the loss, providing the most robust and optimal starting point for the subsequent curriculum stages.

4.4.4. Effects of Decoder Upgrade and DA-ClassMix in SSL-MU

The SSL-MU stage in our pipeline introduces two key designs: upgrading the student model’s decoder from FCN to UPerNet and incorporating the proposed DA-ClassMix geometric augmentation. The corresponding ablation results are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

The effects of decoder upgrade and DA-ClassMix in SSL-MU.

Simply upgrading the decoder to UPerNet yields a substantial performance gain, improving the mIoU by 0.68% (from 80.44% to 81.12%). This indicates that the more complex UPerNet decoder possesses stronger inherent robustness against noise in pseudo-labels generated from unlabeled data, compared to the lightweight FCN decoder. Introducing DA-ClassMix on this basis further raises the mIoU by 0.29% (to 81.41%), with clear improvements for the previously underperforming categories: trees (+0.16%), low vegetation (+0.44%), and car (+0.94%). These results confirm that DA-ClassMix effectively strengthens the model’s ability to segment underperforming categories.

4.4.5. Evaluation of Pseudo-Label Error Mitigation Strategies

The pseudo-labels generated during the SSL-MU stage inevitably contain noise. We evaluated two common strategies to mitigate the impact of these errors. The first strategy, confidence-based filtering (ConfFilt), discards pseudo-labels with confidence scores below a fixed threshold; we tested thresholds of 0.6 and 0.8. The second strategy, confidence-based weighting (ConfWeight), retains all pseudo-labels but weights their contribution to the loss function according to their confidence scores [20].

Contrary to conventional intuition, the results in Table 11 indicate that none of these mitigation strategies led to a significant performance improvement. The mF1 for all configurations remained closely clustered (mF1 ranging from 89.48% to 89.60%). Moreover, the baseline approach of skipping pseudo-label error mitigation achieved the lowest validation loss (0.3379), which offers a more reliable foundation for subsequent training. Therefore, we adopted all the pseudo-label pixels in the SSL-MU and SSL-PIA stages.

Table 11.

Comparisons of different pseudo-label error mitigation strategies in SSL-MU stage.

4.4.6. Impact of Teacher–Student Coupling in SSL-PIA

This section examines the effect of different teacher–student parameter coupling strategies during the SSL-PIA stage. Both teacher and student models are initialized using the student model trained in the SSL-MU stage, ensuring strong initial performance at the beginning of this stage. The validation results under each coupling strategy are listed in Table 12.

Table 12.

Performance comparison of different teacher–student parameter coupling strategies in the SSL-PIA stage.

The results indicate that the exponential moving average (EMA) updating strategy leads to performance degradation compared to the previous step (81.41% → 80.55%, −0.86%). In contrast, fixing the teacher parameters while training the student model yields a significant improvement (81.41% → 82.02%, +0.61%), and sharing parameters between both models increases the mIoU by 0.72% (81.41% → 82.13%). These findings suggest that the latter two strategies are more compatible with the PIA strategy. We hypothesize that these two approaches allow both the teacher and student model to produce higher quality pseudo-labels, but the model exhibits high sensitivity to parameter variations in this stage. The EMA strategy—which generates parameters interpolated between the teacher and student—may destabilize the teacher’s performance, reduce pseudo-label quality, and ultimately lead to performance degradation.

4.4.7. The Effect of the Curriculum-Based Pipeline

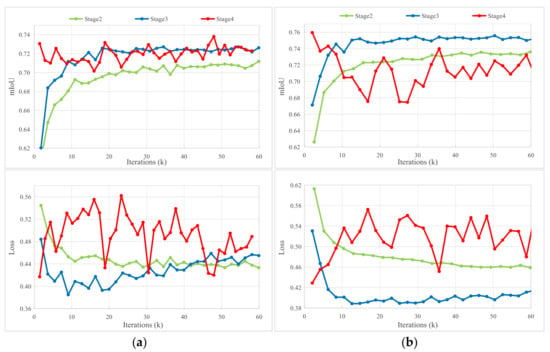

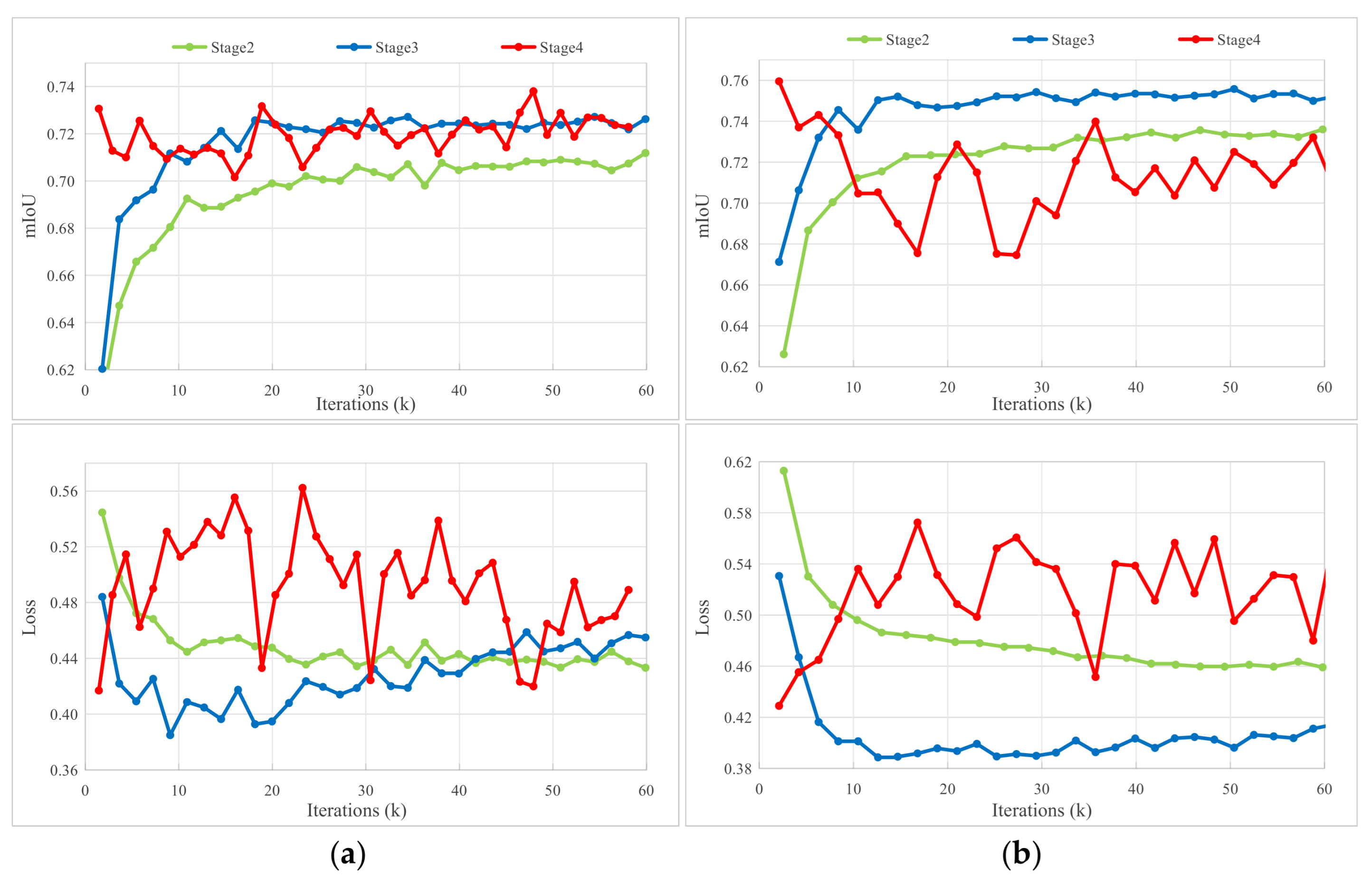

The performance of the proposed CSSP method at different training stages, denoted as CSSP-X (where X = 2, 3, and 4), is summarized in Table 13. Experimental results across the three datasets consistently demonstrate progressive performance improvements as the training proceeds from CSSP-2 to CSSP-4. This trend validates the effectiveness of the curriculum learning design, which successfully guides the model to learn from increasingly challenging tasks and ultimately enhances overall segmentation accuracy.

Table 13.

Performances of the proposed CSSP method at different training stages.

The training dynamics of PIA: Figure 6b illustrates the performance progression of the proposed CSSP method across different training stages, with the gain from CSSP-3 to CSSP-4 attributed to the PIA strategy. The validation accuracy of CSSP-4 exhibits characteristic periodic fluctuations, which are directly correlated with the cyclic learning rate adjustments governed by PIA. Peak performance is attained in the third training cycle, corresponding to optimal augmentation intensity Level 3. A slight accuracy decline observed in the fourth cycle suggests that the further increase in intensity may have exceeded the model’s adaptation capacity, leading to over-perturbation and a subsequent degradation in generalization. This pattern demonstrates that the PIA strategy effectively implements a form of data-level curriculum learning, wherein augmentation intensity is progressively increased to systematically raise sample difficulty, thereby continually challenging the model to adapt—until a drop in validation performance signals the optimal stopping point. The consistent observation of this fluctuation pattern and the identification of intensity Level 3 as the optimal point across the Vaihingen and Inria datasets confirm the robustness and generalizability of this curriculum mechanism.

Optimization stability of CSSP: Figure 6c depicts the validation loss dynamics across the core curriculum stages, providing complementary insights into the optimization stability. CSSP-2, utilizing a lightweight model, establishes a stable but lower performance baseline. Upon introducing the upgraded UPerNet decoder and DA-ClassMix in CSSP-3, we observe a significant and stable performance leap, accompanied by a corresponding drop in validation loss. This indicates that the model, now robustly initialized, can successfully leverage increased capacity and pseudo-labels. In CSSP-4, the integration of PIA—which progressively intensifies photometric perturbations—introduces stronger oscillations and a moderate increase in the validation loss relative to stage 2 and stage 3. Crucially, despite this increased exploration activity, the loss remains well-controlled at a low absolute level (<0.45) and the model maintains training stability. This evidences that the “hard” perturbations introduced by PIA are built upon the robustness foundation established in the prior stages. The framework thus allows the model to safely explore the boundaries of its generalization capability, striking a balance between challenging the model and maintaining optimization control. This pattern—stable baseline, improved performance with added complexity, and controlled exploration at the boundary—provides empirical evidence that our curriculum learning framework effectively guides the optimization through the loss landscape by first finding a flat minimum (stage 2) and then expanding the region of robustness (stages 3 and stage 4) without losing optimization stability.

4.4.8. Training Efficiency and Cost Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the practicality of the proposed method, this section presents a comparative analysis of the classical SSL methods involved in the experiments of Section 4.4.1, focusing on three dimensions: training time, GPU memory consumption, and inference speed. All experiments were conducted under identical hardware and software environments to ensure comparability. As mentioned in Section 4.4.1, methods like CPS and MT suffered from training degradation or even collapse when directly applied to the SwinV2-UPerNet network in an end-to-end manner. We successfully stabilized their training by incorporating adequate supervised finetuning stages or adjusting their pretraining weight (see Table 8 for specific performance). With all methods stabilized, we further analyzed their computational costs, with detailed data provided in Table 14.

Table 14.

Computational cost comparison of different SSL methods. “Time” represents hours, and “Mem” represents peak GPU memory in GB. The SSL stage for CSSP lists costs for stage 3 (SSL-MU) and stage 4 (SSL-PIA) separately.

The IDPT stage required only 5 h (using 4 GPUs), as the backbone network was initialized with weights from large-scale pretraining on 2.3 million public RSIs. Prior to IDPT, the initialization can alternatively leverage existing open-source, pretrained remote sensing vision foundation models [88,89] to reduce the duration of the IDPT stage.

For the finetuning stage, we used the standard finetuning of SwinV2-UPerNet (10 h, 11.5 GB) as the baseline. Our CSSP method, employing a lightweight FCN decoder in this stage, shows advantages in both training time and memory footprint (6 h, 7.7 GB).

In the SSL stage, CPS maintains two independent models requiring back-propagation, leading to nearly double the baseline’s training time and memory consumption. MT’s teacher model, updated via EMA, does not require gradient computation graphs, thus incurring lower cost. FixMatch, a single-network framework, avoids gradient computation for its weakly augmented branch, keeping memory usage similar to the baseline while training time nearly doubles due to dual forward passes. For CSSP, the lightweight teacher network in stage 3 requires no gradient updates, keeping training time close to the baseline while memory usage increases moderately to 15.6 GB. Stage 4 of CSSP reverts to single-network training, with costs similar to FixMatch.

Regarding inference speed, since the final model architecture for all methods is swinV2-UPerNet, their per-image inference latency on identical hardware is exactly the same (~52 ms for a 512 × 512 image).

To summarize, the proposed CSSP systematically addresses the training instability of large ViT models in semi-supervised settings, achieving significant performance gains with a moderately increased total training time and comparable peak memory usage relative to mainstream methods. Considering the substantial cost of large-scale manual annotation required for comparable accuracy gains, the additional computational expense of CSSP is justified, making it an efficient and practical solution.

4.4.9. Model Generalizability Experiments

To further validate the generalizability of the proposed CSSP framework beyond the specific architectural choices in our core experiments, we conducted additional experiments. The goal was to demonstrate that the effectiveness of our curriculum learning pipeline is robust and not contingent upon a particular backbone–decoder combination. In these experiments, the primary SwinV2-B backbone was replaced with a standard ViT-B architecture (approximately 86M parameters, which is comparable to SwinV2-B). Prior to the IDPT stage, the ViT-B backbone was initialized with parameters pretrained on large-scale remote sensing imagery via SelectiveMAE [89]. Furthermore, to evaluate the “light-to-heavy” decoder transition strategy, we tested two alternative decoder pairs: a simple linear classifier serving as the lightweight decoder and the more complex DeepLabV3+ decoder head as the heavyweight component. The performance of these configurations across successive stages of the CSSP is summarized in Table 15.

Table 15.

Generalization performance (mIoU, %) of the CSSP framework across different backbone and decoder combinations on the Potsdam dataset with 1/32 labeled data.

The results demonstrate a consistent and crucial trend: despite the changes in architectural components, the CSSP framework maintains its ability to deliver progressive performance improvement through each successive stage. While the absolute performance metrics understandably vary depending on the capacity of the backbone and decoder, the relative gain achieved by the staged curriculum is evident in both cases. This consistent behavior strongly indicates that the core advantage of CSSP—stabilizing the training of high-capacity models under label scarcity through a staged, easy-to-hard curriculum—constitutes a general-purpose strategy. Its effectiveness is therefore architecture-agnostic, significantly reinforcing the robustness and practical applicability of our method.

An interesting observation is the different optimal PIA intensities (3 for swinV2-B vs. 1 for ViT-B), which suggests that the tolerance to data augmentation strength may be architecture-dependent. This potentially indicates that models with different inductive biases (e.g., swinV2-B’s local window-based attention vs. ViT-B’s global attention) interact differently with the same augmentation policy. This nuance further underscores the importance of adaptive training strategies like PIA within a generalizable framework.

4.5. Experiments on SSDA

We conducted two groups of domain adaptation experiments using the Potsdam and Vaihingen datasets: Potsdam → Vaihingen (Pot2Vai) and Vaihingen → Potsdam (Vai2Pot). Our proposed SSDA method was first evaluated against several supervised baselines and then compared with SoTA UDA and SSDA methods originally developed for CNN architectures. The supervised baselines were evaluated using a segmentation model based on a swinV2-B backbone and an FCN decoder, the same as our method. All SoTA UDA and SSDA methods were implemented using a DeeplabV3+ model with a ResNet-50 backbone. The experimental configurations are summarized in Table 16, with the target domain limited to only 10 annotated samples. As shown in the table, Pot2Vai represents a scenario with abundant source domain data, while Vai2Pot corresponds to a source-scarce setting. This configuration allowed us to analyze the applicability of each method under distinct data availability conditions.

Table 16.

Data configuration for different settings of semantic segmentation experiments. represents the number of images in the target domain validation set.

4.5.1. Results onPot2Vai Experiment

Table 17 presents the performance of different domain adaptation methods for the Pot2Vai experiment. The results from different stages of the proposed CDCSSP method are denoted as CDCSSP-X (where X = 2 and 3). We compared the results from the following perspectives:

Table 17.

The performance of different types of methods for the Pot2Vai experiment.

- (1)

- Baseline comparison: First, although the SSDA baseline uses only 10 annotated target domain images in addition to the UDA setup, it achieves a significant performance gain of 16.90% mIoU (44.26% → 61.16%) compared with the UDA baseline. Second, the supervised baseline attains an mIoU of only 69.73%, indicating that when the RSI dataset is small (Vaihingen contains only 210 images), using ImageNet pretrained weights alone as initialization for swinV2-B is insufficient to achieve satisfactory supervised training performance. After incorporating the proposed CDPT, the supervised baseline performance increases significantly to 73.55% (a gain of 3.82%), demonstrating the importance of CDPT for enhancing feature representation capability of RSI.

- (2)

- Effectiveness of the proposed method: The proposed method CDCSSP-2 achieves an mIoU of 71.01%, already surpassing all compared methods. CDCSSP-3 further improves the result to 72.72% mIoU, a gain of 1.71% over stage 2, validating the efficacy of our curriculum learning pipeline in the SSDA setting. The final performance exceeds the supervised baseline by 2.99%, indicating that our approach effectively leverages the large amount of labeled data from the source domain and unlabeled data from the target domain.

- (3)

- Comparison between different types of methods: First, the selected SoTA UDA method, FLDA-Net, achieves 55.97% mIoU, showing a considerable 5.19% gap compared to the SSDA baseline with only 10 target domain annotations. This substantial performance gap indicates fundamental limitations in UDA methodologies, whereas SSDA approaches with few-shot supervision present a more practical alternative to complex UDA methods. Second, existing SSDA methods perform similarly to the SSDA baseline, around 61% mIoU, which is considerably lower than the proposed CDCSSP-3. We attribute this to their reliance on ResNet-based backbones, which struggle to simultaneously learn and adapt to the significantly different band configurations of RGB and IRRG imagery, thus limiting effective knowledge transfer from the source to the target domain. Third, although our SSL method, the CSSP, outperforms the supervised baseline, it remains 2.28% mIoU behind CDCSSP-3. This confirms the CDCSSP’s ability to utilize source domain annotations effectively, leading to further improvement over the CSSP.

4.5.2. Results on Vai2Pot Experiment

Table 18 presents the performance of different domain adaptation methods for the Vai2Pot experiment. We compared the results from the following perspectives:

Table 18.

The performance of different types of methods for the Vai2Pot experiment.

- (1)

- Baseline comparison: First, the UDA baseline achieves only 32.31% mIoU, which is considerably lower than the corresponding baseline in the Pot2Vai setting (44.26%). This suggests that a larger source domain dataset contributes positively to the model’s generalization capability in the target domain. Second, the SSDA baseline significantly outperforms the UDA baseline by 34.1% in mIoU (reaching 66.41%), demonstrating that even a small number of target domain annotations can substantially enhance model performance. Third, unlike the Pot2Vai scenario, the fully supervised baseline achieves a high mIoU of 80.06%, which can be attributed to the large scale of the Potsdam dataset (2904 images).

- (2)

- Effectiveness of the proposed method: Our CDCSSP method improves the mIoU from 73.63% at stage 2 to 75.63% at stage 3, validating the continuous optimization capability of the curriculum learning strategy. The final performance exceeds the SSDA baseline by 9.22%, although a gap of 4.43% remains compared to the supervised baseline.

- (3)

- Comparison between different types of methods: First, similarly to the Pot2Vai case, UDA methods perform significantly worse than SSDA methods, further confirming that SSDA has greater research potential and practical value than UDA. Second, existing SoTA SSDA methods fail to surpass even the SSDA baseline. This can be attributed to the superior cross-domain feature representation capacity of the ViT-based backbone—a capability that is typically lacking in CNN-based architectures. Third, our proposed CSSP method significantly outperforms all existing SoTA SSDA methods, even though it cannot see labeled data in the source domain compared with SSDA methods. However, CDCSSP-3 only slightly surpasses the CSSP by a margin of 0.12% in mIoU. A plausible explanation for this marginal gain is the limited volume of source domain data (only 210 images in Vaihingen), which may restrict the additional performance contribution that domain adaptation can provide over the SSL approach.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a curriculum learning-based pipeline (CSSP) designed to overcome overfitting and performance limitations in RSI SSSS using ViT-based models. The method employs a structured four-stage workflow that progressively guides the model from easier to more challenging tasks. This is achieved through self-supervised pretraining, a strategic transition from lightweight to heavyweight decoders, and adaptive data augmentation strategies. Specifically, the proposed DA-ClassMix enhances learning for underperforming categories, while the PIA strategy systematically increases augmentation intensity to explore the model’s robustness limits in a controlled manner. Experimental results across multiple datasets confirm that the CSSP delivers superior performance under limited annotation budgets, often matching or even surpassing fully supervised counterparts. Furthermore, the extension of the CSSP to SSDA, creating the CDCSSP, demonstrates its robust cross-domain generalization capability.

This work establishes a stable and efficient foundation for training ViT-based segmentation models with minimal supervision, paving the way for more data-efficient remote sensing analysis. In future work, we will focus on exploring more advanced backbone networks for multi-modal segmentation models and applying the CSSP framework to enhance the SSL of such models, which often face data-scarcity challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L. and X.M.; methodology, P.L.; software, P.L. and H.Z. (Hongbo Zhu); validation, P.L. and Y.M.; formal analysis, P.L.; investigation, P.L.; resources, X.M.; data curation, X.M. and Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L.; writing—review and editing, X.G. and H.Z. (Huijie Zhao); visualization, P.L. and H.Z. (Hongbo Zhu); supervision, X.M.; project administration, X.G.; funding acquisition, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: L2424330) and the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Grant Number: 2025A03J3171).

Data Availability Statement

All datasets used in this study are publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Ablation Study on PIA in the SSDA

As stated in Section 3.2, we provide empirical evidence and analysis supporting the design choice to omit the PIA stage from our CDCSSP.

Appendix A.1. Experiment and Results

To validate the aforementioned design, we extended the CDCSSP pipeline by adding PIA as an optional fourth stage and compared its training dynamics with previous stages. The validation mIoU and loss curves of two experiments (depicted in Section 4.5) are shown in Figure A1.

Figure A1.

Training dynamics of the CDCSSP pipeline across stage 2, 3, and 4. (a) Pot2Vai; (b) Vai2Pot.

Figure A1.

Training dynamics of the CDCSSP pipeline across stage 2, 3, and 4. (a) Pot2Vai; (b) Vai2Pot.