Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This paper presents an efficient end-to-end network architecture, termed TriadFlow-Net, which endows remote sensing building extraction with three core capabilities: global semantic understanding (via GCMM), local detail restoration through LDEM, and multi-scale contextual awareness enabled by the Multi-scale Adaptive Feature Enhancement Module (MAFEM).

- Experimental results on three benchmark datasets—the WHU Building Dataset, the Massachusetts Buildings Dataset, and the Inria Aerial Image Labeling Dataset—demonstrate that the proposed TriadFlow-Net consistently outperforms state-of-the-art methods across multiple evaluation metrics while maintaining computational efficiency, thereby offering a novel and effective solution for high-resolution remote sensing building extraction.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Through the design of three major modules, our method jointly optimizes global semantic understanding, local detail recovery, and multi-scale context awareness within a unified framework. This not only overcomes the performance bottlenecks of conventional CNNs or Transformers in remote sensing building segmentation but also provides an efficient and transferable general paradigm for other high-resolution ground object segmentation tasks.

- TriadFlow-Net achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple public benchmarks while maintaining low computational overhead, demonstrating its strong deployability and practical viability. This advancement facilitates the transition of high-precision building extraction techniques from laboratory research to large-scale operational applications—such as national land surveys and urban renewal monitoring.

Abstract

Building extraction from remote sensing imagery plays a pivotal role in applications such as smart cities, urban planning, and disaster assessment. Although deep learning has significantly advanced this task, existing methods still struggle to strike an effective balance among global semantic understanding, local detail recovery, and multi-scale contextual awareness—particularly when confronted with challenges including extreme scale variations, complex spatial distributions, occlusions, and ambiguous boundaries. To address these issues, we propose TriadFlow-Net, an efficient end-to-end network architecture. First, we introduce the Multi-scale Attention Feature Enhancement Module (MAFEM), which employs parallel attention branches with varying neighborhood radii to adaptively capture multi-scale contextual information, thereby alleviating the problem of imbalanced receptive field coverage. Second, to enhance robustness under severe occlusion scenarios, we innovatively integrate a Non-Causal State Space Model (NC-SSD) with a Densely Connected Dynamic Fusion (DCDF) mechanism, enabling linear-complexity modeling of global long-range dependencies. Finally, we incorporate a Multi-scale High-Frequency Detail Extractor (MHFE) along with a channel–spatial attention mechanism to precisely refine boundary details while suppressing noise. Extensive experiments conducted on three publicly available building segmentation benchmarks demonstrate that the proposed TriadFlow-Net achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple evaluation metrics, while maintaining computational efficiency—offering a novel and effective solution for high-resolution remote sensing building extraction.

1. Introduction

Buildings are among the most critical infrastructures in urban areas, and accurately acquiring building information is of significant importance for applications such as smart city construction [1], urban planning [2], and disaster assessment [3]. With the rapid advancement of Earth observation technologies, high-resolution remote sensing imagery has become a vital data source for building information extraction, owing to its clear textural details [4] and rich spatial information [5]. Nevertheless, accurate building segmentation in such imagery remains challenging due to complex urban backgrounds, diverse building morphologies, occlusion and interferences (e.g., trees and shadows), and the substantial computational demands associated with processing high-resolution data.

Traditional building extraction methods primarily rely on handcrafted features, such as geometry, texture [6], and shadow cues [7] for pixel-wise identification, or employ machine learning algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) with image objects as processing units for labeling. Although these conventional approaches offer good interpretability for specific features, they heavily depend on manual expertise and prior knowledge, making it difficult to effectively distinguish buildings from complex backgrounds across diverse sensors and heterogeneous building types. Moreover, these methods typically fail to exploit contextual information inherent in remote sensing imagery, leading to suboptimal performance in extracting large or densely clustered buildings and limiting their ability to capture the intricate spatial patterns present in modern high-resolution remote sensing data.

Thus, the advent of deep learning has brought revolutionary advancements to building segmentation in remote sensing imagery. The Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) [8] was the first to achieve end-to-end pixel-wise segmentation, laying the groundwork for this field. Subsequently, encoder-decoder architectures like U-Net [9] have become widely adopted for remote sensing building extraction tasks. Early approaches commonly integrated dilated convolutions or pyramid pooling modules [10] into U-shaped architectures to enhance scale-awareness. However, these strategies often rely on deep stacking of layers, leading to substantial computational redundancy and efficiency bottlenecks. More critically, the dilation rates and pooling scales must be manually predefined. When confronted with ultra-large industrial facilities or miniature ancillary structures, fixed receptive fields often result in insufficient or redundant contextual coverage, thereby leading to missed detections or over-segmentation [11]. To overcome these limitations, attention mechanisms with global modeling capacity have been introduced. Some works adopt Transformer architectures [12,13] or embed attention modules within decoders [14,15,16]. For instance, BuildFormer (Building Extraction with Vision Transformer) [17] and UANet (Uncertainty-Aware Network) [18] leverage self-attention to strengthen long-range dependency modeling. Nevertheless, their computational and memory costs grow quadratically with image resolution, making them impractical for high-resolution remote sensing imagery. Recently, linear attention [19] and State Space Models (SSMs) [20,21,22] have emerged as efficient alternatives. However, linear attention suffers from limited representational power, while causal SSMs such as Mamba [23] inherently disrupt 2D spatial structures due to their unidirectional processing. Multi-directional scanning schemes (e.g., VMamba [24,25]) have been proposed to compensate, yet they neglect the isotropic neighborhood relationships among pixels, impairing the modeling of global spatial coherence—particularly under extreme scale variations. Concurrently, existing methodologies generally overlook spatially rich shallow features and local details, resulting in the loss of small objects and boundary information. To mitigate this issue, several studies have attempted to incorporate edge priors as auxiliary supervision. For instance, some integrate the Sobel edge detector and fuse the resulting features with deep semantic features for edge-guided learning in the decoder module [26], while others optimize boundaries via a coarse-to-fine strategy based on an edge classification branch [27]. However, these strategies typically treat edge detection as an independent task, failing to achieve deep fusion between high-frequency detail information and the backbone features. In summary, current mainstream architectures face several critical limitations: (1) multi-scale strategies with fixed receptive fields often result in unbalanced contextual coverage; (2) although focusing on multi-scale fusion, they fail to explicitly model long-range robustness against occlusions; (3) reliance on computationally expensive global attention mechanisms hinders their adaptation to high-resolution imagery; and (4) while incorporating edge priors, these methods do not integrate them into the backbone for joint optimization, necessitating additional edge annotations and incurring high computational overhead; (5) More fundamentally, existing methods often focus on optimizing only one aspect, either global semantic understanding, multi-scale representation, or local detail restoration—while overlooking the inherent tensions and synergistic relationships among these three dimensions, making it difficult to achieve a balance between accuracy and efficiency in complex remote sensing scenarios.

A fundamental challenge remains: there exists an inherent tension among global semantic understanding, multi-scale representation, and local detail restoration. Global semantic understanding often comes at the expense of fine-grained details; multi-scale feature representation, while capable of capturing objects across varying scales, frequently leads to misalignment in both spatial and semantic domains and may introduce redundant or even erroneous information; and although local details aid in recovering high-frequency structures, they can also bring noise and interference that undermine global semantic consistency. To address this, we propose TriadFlow-Net, which achieves dynamic balance and mutual enhancement among these three aspects through carefully designed modules—MAFEM, GCMM, and LDEM. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- To address the challenge of large-scale variations in buildings, we construct the Multi-scale Attention Feature Enhancement Module (MAFEM). By deploying parallel attention modules with varying neighborhood radii, MAFEM adaptively captures multi-scale contextual information, thereby significantly enhancing the perceptual robustness of the model towards buildings with drastic scale changes.

- (2)

- To capture cross-building semantic consistency and mitigate the impact of occlusions and disconnections, we innovatively propose the Global Context Mixing Module (GCMM). This module efficiently captures long-range dependencies, substantially strengthening the model’s recognition capability in scenes with complex distributions and occlusion interference.

- (3)

- To achieve self-supervised boundary enhancement without requiring additional annotations, we fuse the original imagery with shallow decoder features. By integrating a Multi-scale High-frequency Extractor (MHFE) and a Channel-Spatial Collaborative Attention mechanism, we precisely locate and enhance high-frequency boundary information. This strategy effectively suppresses noise while significantly improving the integrity and localization accuracy of building edges.

- (4)

- In contrast to existing methods that focus solely on improving a single dimension, we systematically construct a collaborative optimization framework that integrates three core capabilities: global semantic understanding, multi-scale feature representation, and local detail restoration. Specifically, MAFEM generates an initial multi-scale representation, GCMM achieves fine-grained semantic alignment, and LDEM accurately recovers high-frequency boundary structures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of theproposed model, this paper selects three widely recognized and authoritative datasets in the field of building semantic segmentation: the WHU Building Dataset, the Massachusetts Buildings Dataset, and the Inria Aerial Image Labeling Dataset.

WHU Building Dataset [28]: Owing to its extensive coverage, high spatial resolution, and large data volume, this dataset has become a mainstream benchmark in building extraction. It comprises two subsets of imagery, aerial and satellite, and this work adopts the more commonly used aerial subset. This subset covers approximately 450 km2 in New Zealand, containing around 220,000 individual buildings and 8189 images of size 512 × 512 (4736 for training, 1036 for validation, and 2416 for testing). The spatial resolution ranges from 0.075 m to 2.7 m, and the dataset exhibits significant diversity in geographic regions and architectural styles.

Massachusetts Building Dataset [29]: Constructed by a team from China University of Geosciences, this dataset consists of 151 aerial images of size 1500 × 1500 pixels (137 for training, 10 for validation, and 4 for testing), covering approximately 340 km2 of the Boston metropolitan area and its surroundings, with a spatial resolution of 1 m. It includes over 10,000 building instances, characterized by high building density, complex urban environments, and substantial variation in building scale and architectural style. This presents a rich and challenging testbed that imposes stringent demands on model generalization.

Inria Aerial Image Labeling Dataset [30]: This dataset comprises 360 aerial images of size 5000 × 5000 pixels collected from multiple regions, including Austria and the United States, with a high spatial resolution of 0.3 m. It encompasses both urban cores and suburban residential areas, exhibiting extreme diversity in building density and typology. The official dataset provides 180 labeled training images, while the test images’ labels remain undisclosed. To obtain final performance metrics, prediction results must be submitted through their official evaluation platform. The first five images of each city are set as test images according to official guidelines. All images were resized to 512 pixels, resulting in a dataset comprising 9737 training images and 1942 validation images.

2.2. Experimental Detail

All experiments in this paper were conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB of memory. TriadFlow-Net and all comparative methods were implemented using the PyTorch 2.7.1 (CUDA 12.8) framework. The hyperparameters for the baseline methods were kept consistent with those reported in their original publications, and all models shared identical training settings. During data preprocessing, we applied random hue/saturation adjustments, random scaling, horizontal/vertical flipping, and 90-degree rotations for data augmentation. All input images were uniformly cropped to 512 × 512 pixels, and a batch size of 8 was used throughout training. In the training phase, we selected the AdamW [31] optimizer and employed the cosine strategy to adjust the learning rate. We trained all models for 100 epochs on each of the three datasets. The loss function consisted of an equally weighted (1:1) combination of Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) and Dice loss.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of TriadFlow-Net and its competing methods on the task of semantic segmentation of high-resolution remote sensing imagery, we adopt the following four standard evaluation metrics: Intersection over Union (IoU), F1-Score, Precision, and Recall. Let TP, FP, and FN denote the number of true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively (note that true negatives, TN, are not involved in the computation of these metrics). The metrics are formally defined as follows:

All metrics take values in the range [0, 1], with higher values indicating better segmentation performance.

2.4. Overall Methodological Framework

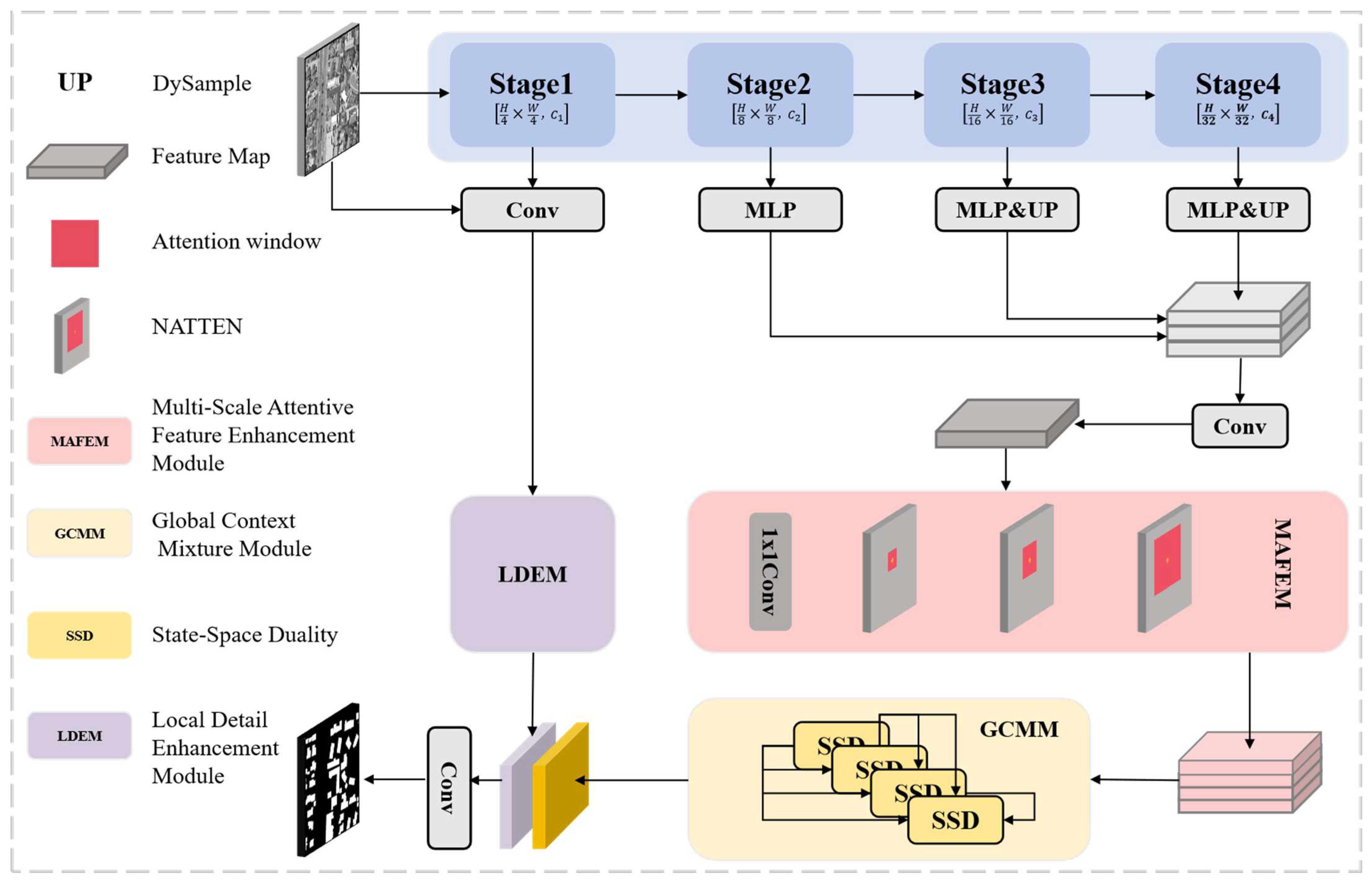

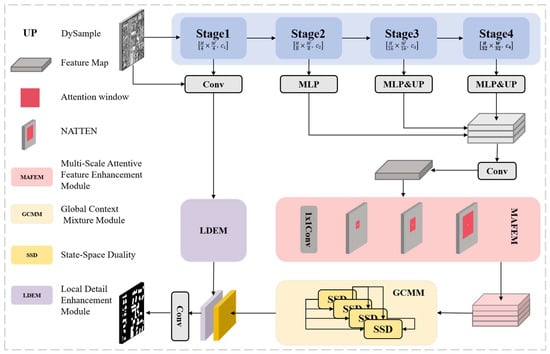

This paper proposes TriadFlow-Net, an efficient end-to-end semantic segmentation network designed for high-resolution remote sensing imagery. The network employs ResNet-50 as its backbone to extract multi-level features from the input image, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of the TriadFlow-Net, which is composed of a general encoder-decoder, a MAFEM, a GCMM, and a LDEM.

First, high-level features are spatially aligned and concatenated to generate a coarse multi-scale feature representation, which is further enhanced by a Multi-scale Attention Feature Enhancement Module (MAFEM).

Next, the enhanced features from MAFEM are fed into a Global Context Mixing Module (GCMM) to model long-range semantic dependencies, producing a globally consistent semantic representation.

Finally, to recover high-frequency details lost due to downsampling, a Local Detail Enhancement Module (LDEM) fuses the low-level feature F1 with the original input image to extract edge and fine-grained information. The final high-precision segmentation result is obtained by upsampling and fusing the semantic features from GCMM with the detail-enhanced features from LDEM.

In conclusion, MAFEM, GCMM and LDEM work in concert to optimize three key aspects: multi-scale contextual modeling, global semantic aggregation, and local detail restoration, achieving efficient and robust semantic segmentation of remote sensing images.

2.4.1. Multi-Scale Attentive Feature Enhancement Module

Multi-scale feature learning represents a pivotal challenge in semantic segmentation. VWformer investigates this issue through Effective Receptive Field (ERF) visualization analysis, which validates the widespread issues of insufficient scale coverage and receptive field degradation in deep networks for traditional multi-scale methods. This finding provides significant theoretical guidance for multi-scale feature learning. Based on this, we propose the Multi-scale Attention Feature Enhancement Module (MAFEM), which addresses the uneven coverage of multi-scale receptive fields and strengthens cross-scale representational capacity while maintaining computational efficiency.

Given the last three feature maps from the backbone network, we first align them to the spatial resolution of using learnable linear projections, followed by dynamic upsampling (DySample) [32]. This operator predicts sub-pixel offsets via a lightweight sub-network and achieves differentiable, content-adaptive upsampling based on bilinear interpolation:

where denotes the channel projection matrix and is the upsampling factor. The aligned features are then concatenated along the channel dimension and fused via a convolution:

To achieve a uniform distribution of multi-scale receptive fields, is fed into a context enhancement structure composed of four parallel branches: one convolutional branch preserves the original local information and serves as the fusion baseline, while three Neighborhood Attention (NA) branches model multi-scale context using distinct window sizes. Let the input feature be ; the outputs of the branches are:

where denotes a neighborhood attention operation with kernel size , number of attention heads , and stride . The configurations of the three NA branches are:

Considering that the fused feature processed by this module originates from the high-level output of the backbone network, it typically has a spatial resolution of 64 × 64 pixels. At this scale, window sizes of 7, 15, and 31 cover approximately 11%, 23%, and 48% of the feature map’s spatial extent, respectively. This enables effective correspondence with the characteristic scale spectrum in remote sensing scenes, ranging from fine building contours and medium-sized individual structures to large industrial facilities or building complexes. Based on the above considerations, we set the window sizes to 7, 15, and 31 to achieve a good balance between performance and computational cost.

Finally, the outputs of all four branches are concatenated along the channel dimension and fused via a convolution to produce the enhanced feature representation:

This module explicitly models cross-scale feature dependencies, achieving efficient and balanced multi-scale perception.

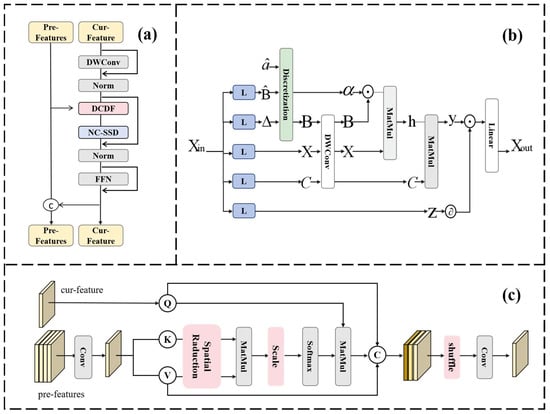

2.4.2. Global Context Mixture Module

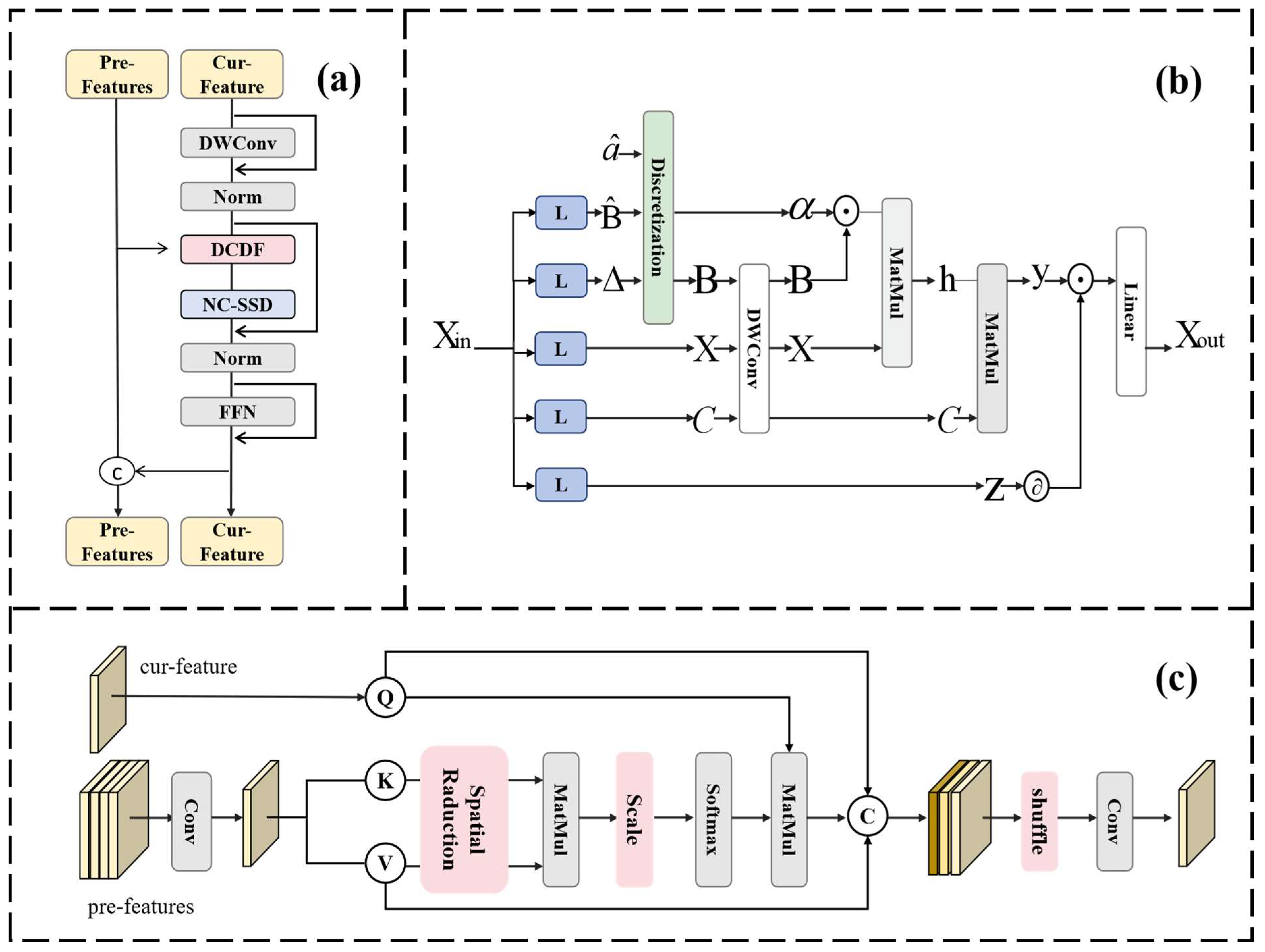

To efficiently model global context in high-resolution remote sensing imagery and alleviate representation collapse in deep networks, we propose the Global Context Mixture Module (GCMM), as illustrated in Figure 2. This module is collaboratively composed of a Non-Causal State Space Duality (NC-SSD) [33,34,35,36] and a Dense-Connection Dynamic Fusion (DCDF): NC-SSD captures intra-layer global long-range dependencies with linear complexity, while DCDF maintains representational diversity through dynamic cross-layer feature fusion, effectively mitigating feature homogenization in deep networks.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the proposed (a) GCMM, (b) NC-SSD, (c) DCDF.

Specifically, the discrete-time state-space model (SSM) is expressed as:

where . In Mamba2 [21], the state transition matrix is simplified to a scalar, yielding the output formulation:

where is a scalar state decay parameter, and are input and output projection vectors, with denoting the hidden state.

This recursive model is inherently characterized by unidirectional temporal dependency—meaning the current state is entirely determined by past states and cannot access future information. This causal nature fundamentally restricts the free flow of information across spatial dimensions, rendering information propagation essentially unidirectional and thus ill-suited for effectively modeling the non-causal, omnidirectional contextual relationships prevalent in remote sensing imagery. Moreover, in practice, traditional approaches often flatten 2D feature maps into 1D sequences to accommodate the recursive architecture, which disrupts the intrinsic 2D spatial structure and local geometric relationships among image patches, further degrading the model’s ability to capture global spatial dependencies. Consequently, conventional recursive-based spatial context models struggle to effectively represent the bidirectional or even omnidirectional complex spatial dependencies inherent in high-resolution remote sensing images.

To overcome this limitation, NC-SSD addresses these issues by reformulating the state update rule from a recursive to an accumulative form, allowing the contribution of each token to the current hidden state to be directly determined by its own term scaled by , rather than through cumulative products of multiple coefficients:

Furthermore, NC-SSD integrates both forward and backward scans, enabling every position to access global input:

where . Ignoring the bias term , the global hidden state can be expressed as a weighted sum:

The results from forward and backward scans are seamlessly combined to establish global context. This is effectively equivalent to removing the causal mask and converting the model into a non-causal form. Consequently, the contribution of different tokens to the current hidden state is no longer dependent on their spatial distance. Thus, processing flattened 2D feature maps as 1D sequences no longer compromises their original structural relationships.

DCDF is dedicated to mitigating representation collapse. Building upon the core concept of dense connectivity, DCDF enables the current layer to directly access all output features from preceding layers, thereby expanding the inter-layer information transfer bandwidth. Unlike static fusion strategies, DCDF employs a position-adaptive dynamic weight allocation mechanism. Specifically, let the input to the current layer be , and concatenate the features from all preceding layers along the channel dimension to form , where denotes the accumulated number of channels. After projection via a convolution, is split into key and value .

To balance computational efficiency and contextual fidelity, spatial reduction is applied to both the key and value: with a reduction ratio , onvolutions with stride are applied to and , downsampling them to , followed by linear projection to obtain:

The query is derived from via a convolution, preserving the original resolution. An asymmetric-resolution cross-attention is then constructed:

where and denotes the number of attention heads. This operation reduces the attention complexity from to , while allowing the current layer to adaptively aggregate global historical context.

The final output is produced through three-branch feature fusion:

where denotes channel-wise concatenation, is a channel shuffle operation, and is a convolution that unifies the output channel dimension to .

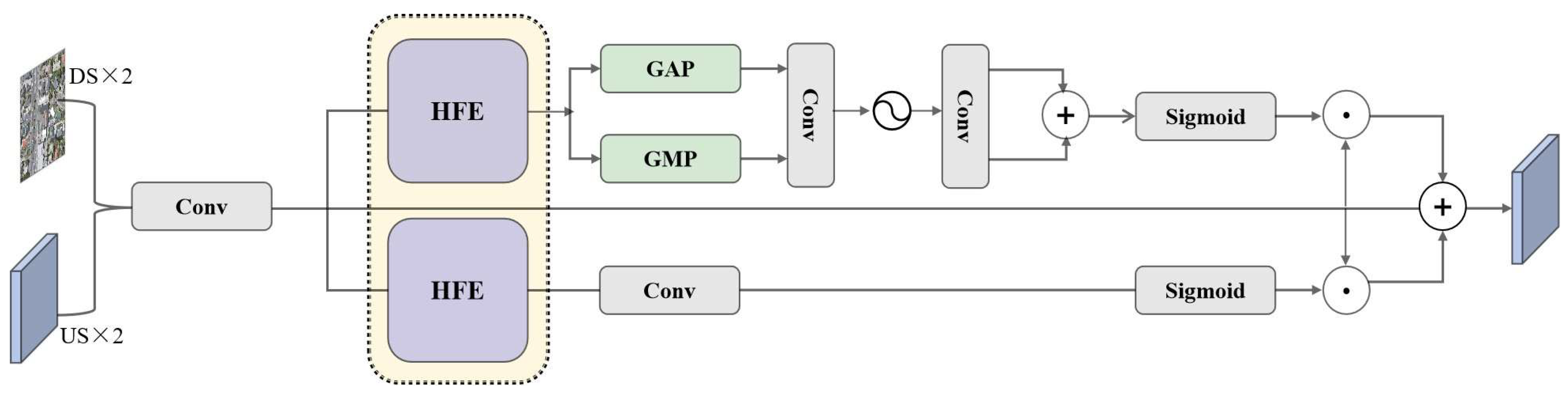

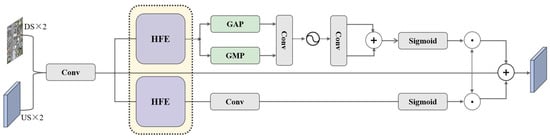

2.4.3. Local Detail Enhancement Module (LDEM)

Precise boundary delineation in semantic segmentation necessitates the model’s capability to simultaneously perceive spatial position sensitivity and channel-wise semantic dependencies [37]. Conventional feature enhancement methods often overlook the intrinsic disparities between spatial and channel domain feature correlations, resulting in insufficient fine-grained representation capability within boundary regions. To this end, we propose the Local Detail Enhancement Module (LDEM), as illustrated in Figure 3. Given an input feature map , LDEM enhances high-frequency detail information through the following steps.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the proposed LDEM.

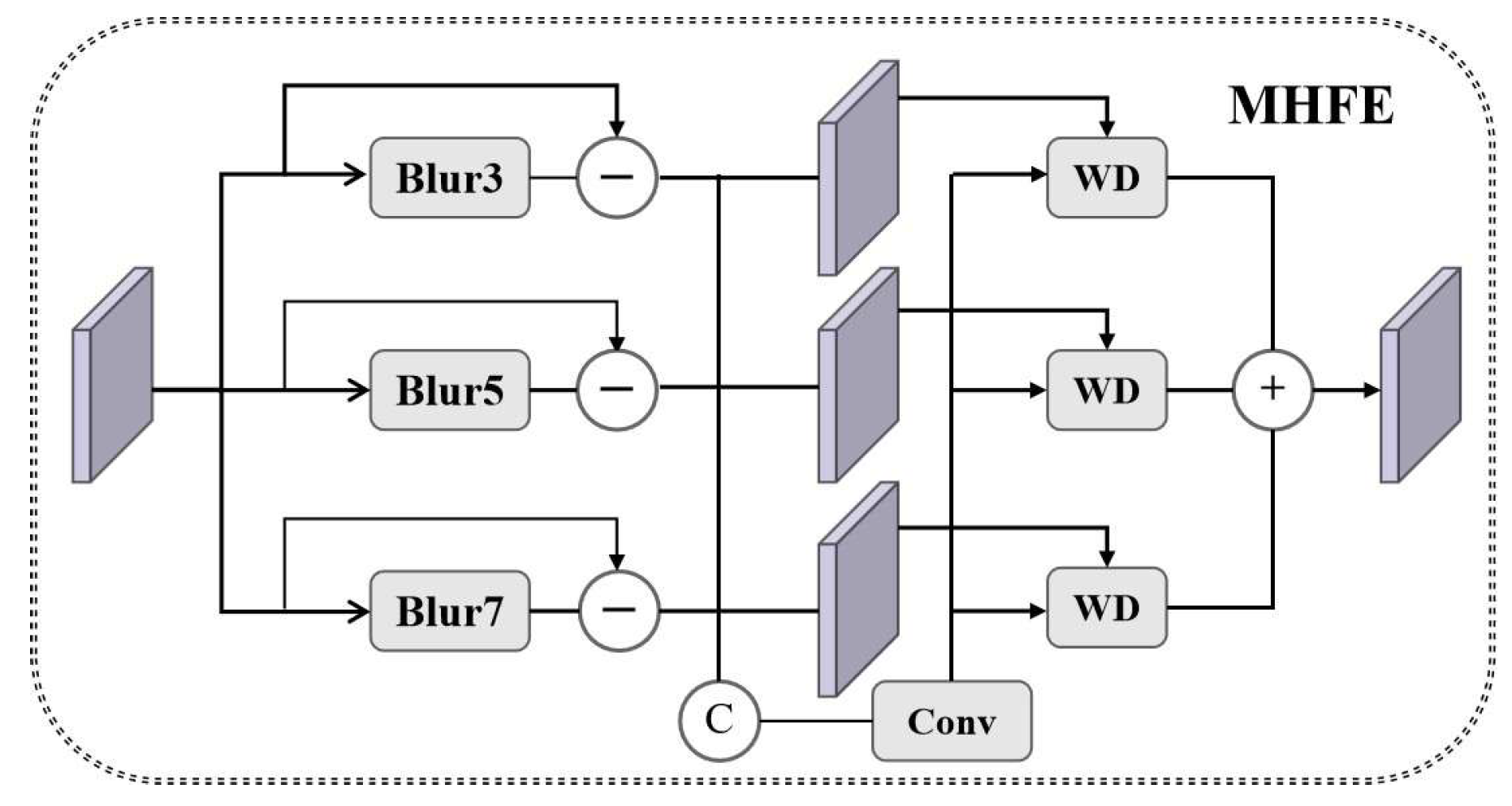

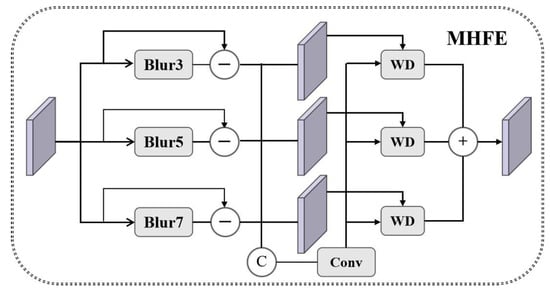

First, multi-scale high-frequency features are extracted, as illustrated in Figure 4. We define three isotropic Gaussian kernels:

Figure 4.

Illustration of the proposed MHFE.

With corresponding kernel sizes and standard deviations . Its parameter selection is strictly based on the typical spatial scale characteristics of remote sensing imagery and the physical constraints of high-frequency feature extraction. First, to avoid frequency-domain aliasing and ensure the completeness of high-frequency feature extraction, it must satisfy , while the kernel size must meet to cover the 99.7% energy within the Gaussian distribution ( interval). The second is that high-frequency features like building edges exhibit stable physical scale distributions (2–5 pixels) in remote sensing imagery. This scale range aligns perfectly with , the specific correspondence is (covers pixels, capturing sub-pixel textures); (covers pixels); (covers pixels, extracting large-scale structures like block boundaries). Its fixed design leverages the global physical consistency inherent in remote sensing tasks, eliminating the need for task-specific adaptation and thereby avoiding the risk of overfitting associated with learnable mechanisms in small-sample scenarios.

For the input feature , we independently apply the aforementioned Gaussian kernel to each channel via channel-preserving 2D convolutional smoothing, obtaining low-frequency approximations at three scales. Subsequently, multi-scale high-frequency details are extracted by computing the residuals between the original feature and the smoothed results at each scale.

where denotes the channel of the input feature map , and denotes 2D spatial convolution with a fixed isotropic Gaussian kernel . This operation is applied independently per channel, preserving spectral information while enhancing multi-scale spatial details.

Next, a gated adaptive fusion mechanism integrates the multi-scale high-frequency features, as illustrated in Figure 4. The set is concatenated along the channel dimension to form , and a convolutional layer is applied to generate spatially adaptive weights:

These weights are then used to compute a weighted fusion of the high-frequency features:

where denotes the -th channel of , and represents element-wise multiplication.

3. Result

To validate the effectiveness of TriadFlow-Net, this section conducts comparative experiments with multiple representative semantic segmentation methods. The selected approaches include: CNN-based models, U-Net [9] and DeepLab V3+ [38], Transformer-based systems SegFormer [39] and Swin-UNet [40], Vision Mamba (State Space Model, SSM)-based RSMamba [41] and VM-UNetV2 [16], as well as specialized building extraction methods BuildFormer [17], UANet [18], and EGAFNet [42]. To ensure experimental fairness, all comparison methods employ encoders with comparable parameter sizes and computational costs, including ResNet50, SwinV2-T, and VMamba-T. In the results, the best performance metrics are highlighted in bold, while suboptimal outcomes are indicated by underlining.

3.1. Results on WHU Building Dataset

Quantitative Comparative Analysis: Table 1 presents the comprehensive quantitative evaluation results of various methods on the WHU building dataset. The proposed TriadFlow-Net method achieves 90.69% in Intersection-Union Ratio (IoU), 95.12% in F1 value, 95.20% in Precision, and 95.03% in Recall, outperforming all comparison methods, including U-Net, DeepLabV3+, SegFormer, Swin-UNet, RSMamba, VM-UNetV2, BuildFormer, UANet, and EGAFNet. Notably, compared to the current best-performing UANet, our method demonstrates improvements of 0.46% in IoU, 0.28% in F1 value, 0.38% in Precision, and 0.02% in Recall, highlighting the effectiveness and superiority of our proposed approach.

Table 1.

Performance comparison with baseline models on the test datasets. The best score for each metric is bolded, and the second-best score is underlined.

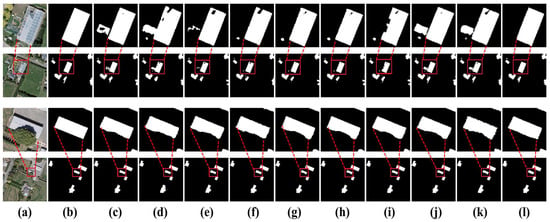

Qualitative Comparative Analysis: Figure 5. presents visual comparisons of various methods on the WHU building dataset. In the first image, the greenhouse roof marked by red boxes shows significant image damage, resulting in severe color inconsistency that substantially increases the difficulty of accurate building extraction. Except for TriadFlow-Net, all other comparison methods exhibited misjudgments, with extracted building outlines showing noticeable gaps or fractures. This demonstrates that TriadFlow-Net exhibits superior robustness in addressing local texture distortion, effectively validating the GCMM module’s enhanced capability to capture global contextual semantic information. Additionally, the ground insulation film area in the upper-right corner of the red box was misidentified as a building target due to spectral similarity with buildings. Only SwinUNet, RSMamba, VM-UNetV2, BuildFormer, and TriadFlow-Net avoid this error. Notably, while most methods employ globally receptive Transformers or Mamba encoders, TriadFlow-Net achieves excellent global feature modeling using only a CNN encoder, thanks to its efficient decoder design. In the second image, the building within the red box is severely obscured by dense trees, making accurate recognition challenging for most methods. Specifically, U-Net, DeepLabV3+, SegFormer, Swin-UNet, RSMamba, VM-UNetV2, BuildFormer, UANet and EGAFNet all showed detection leakage, while only TriadFlow-Net could extract the occluded buildings relatively completely, which further verified its robustness in complex occlusion scenarios.

Figure 5.

Visual comparison of the WHU building dataset. (a) Image. (b) Mask. (c) U-Net. (d) DeepLabV3+. (e) SegFormer. (f) Swin-UNet. (g) RSMamba. (h) VM-UNetV2. (i) BuildFormer. (j) UANet. (k) EGAFNet. (l) ours.

3.2. Results on the Massachusetts Building Dataset

Quantitative Analysis: Table 1 presents the comprehensive quantitative evaluation results of various methods on the Massachusetts building dataset. TriadFlow-Net demonstrated the best performance in IoU, F1, and Recall metrics, while ranking second with only a slight margin of difference in Precision compared to the current best method. Compared to existing state-of-the-art approaches, TriadFlow-Net achieved improvements of 1.24%, 0.86%, and 0.21% in these three metrics, respectively. These enhanced performance indicators fully validate the proposed method’s effectiveness and robustness in extreme scenarios featuring dense distributions of small targets and relatively scarce training samples.

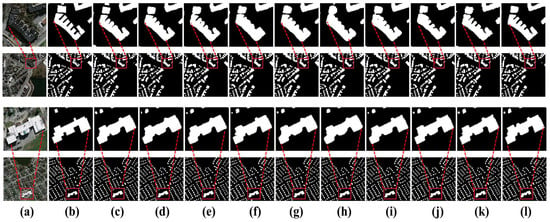

Visual Analysis: By comparing the prediction results of various methods on the Massachusetts building dataset shown in Figure 6, significant differences can be observed in their capabilities for building boundary extraction and segmentation of tiny objects. This dataset contains multiple extreme scenarios, including highly complex boundary structures, severe occlusions, and coexisting clusters of numerous small-scale buildings. In the red-boxed region of the first image, building boundaries exhibit a jagged morphology with rich hierarchical details, representing a typical high-complexity boundary scenario. Under such challenging conditions, only TriadFlow-Net is able to fully and accurately reconstruct the building contours and effectively capture the geometric features of tiny structures. In contrast, all other methods suffer from varying degrees of edge fragmentation or structural loss, which validates the critical role of the LDEM module in enhancing building boundary completeness. In the extreme scenario of densely packed buildings (as highlighted by the red box in Figure 6), most existing methods—due to insufficient fine-grained contextual modeling—tend to erroneously merge adjacent buildings into a single region, resulting in severe structural adhesion. In comparison, TriadFlow-Net effectively disentangles the semantic ambiguity among high-density buildings through the multi-scale feature enhancement mechanism of MAFEM and the boundary modulation strategy of LDEM. This result demonstrates TriadFlow-Net’s robust structural awareness in ultra-high-density building scenarios. In the second image, UNet, DeepLabV3+, and SegFormer all fail to detect buildings partially occluded by trees, misclassifying them as non-building regions and thereby significantly degrading segmentation accuracy. In contrast, TriadFlow-Net leverages its GCMM module to associate occluded regions with unoccluded parts via global contextual information, successfully recovering the obscured building contours and achieving higher recall and segmentation accuracy.

Figure 6.

Visual comparison of the Massachusetts building dataset. (a) Image. (b) Mask. (c) U-Net. (d) DeepLabV3+. (e) SegFormer. (f) Swin-UNet. (g) RSMamba. (h) VM-UNetV2. (i) BuildFormer. (j) UANet. (k) EGAFNet. (l) ours.

Collectively, these results indicate that TriadFlow-Net maintains superior segmentation accuracy and enhanced detail preservation even under challenging conditions involving complex boundaries, severe occlusions, and tiny-scale buildings.

3.3. Results on Inria Aerial Image Labeling Dataset

Quantitative Analysis: Table 1 presents the comprehensive quantitative evaluation results on the Inria Aerial Image Labeling dataset. TriadFlow-Net achieves the optimal performance across all metrics. Compared to the current state-of-the-art method, it demonstrates significant improvements of 1.59%, 0.95%, 1.12%, and 0.79% in terms of IoU, F1-score, Precision, and Recall. These substantial gains fully validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

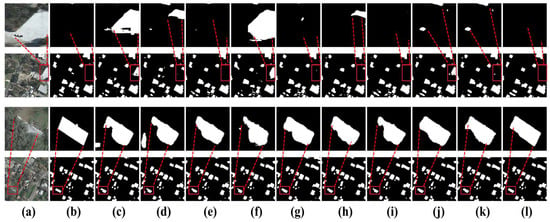

Visual Analysis: Figure 7 presents the segmentation results on the Inria Aerial Image Labeling dataset. This dataset encompasses various extreme interference scenarios: on one hand, non-building regions such as roads and parking lots exhibit spectral responses and geometric shapes highly similar to buildings, leading to frequent false positives; on the other hand, dense vegetation occlusion, strong shadows, and extremely narrow gaps between adjacent buildings further exacerbate segmentation difficulty. Specifically, in the red-boxed region of the first image, there exists a square patch of hard-surfaced ground whose shape closely resembles a building footprint and whose reflectance characteristics are nearly identical to those of rooftops. Under this high-confusion background, U-Net, DeepLabV3+, Swin-UNet, RSMamba, VM-UNetV2, UANet, and EGAFNet all misclassify this area as a building, resulting in significant false detections. In contrast, TriadFlow-Net achieves precise discrimination thanks to the MAFEM module’s adaptive fusion capability for multi-scale contextual information, substantially improving building extraction accuracy. In the second image, the scene simultaneously presents two highly challenging extreme cases: near-complete occlusion of buildings and ultra-narrow inter-building gaps. Despite these difficulties, TriadFlow-Net demonstrates remarkable robustness. By leveraging the GCMM module to model long-range dependencies, it successfully associates visible rooftop regions and fully reconstructs the contours of severely occluded buildings. Notably, the narrow gap between the building highlighted in the red box and its neighboring structures is accurately delineated by TriadFlow-Net—a fine detail that all other compared methods fail to capture correctly, typically exhibiting structural adhesion or blurred boundaries.

Figure 7.

Visual comparison on the Inria Aerial Image Labeling dataset. (a) Image. (b) Mask. (c) U-Net. (d) DeepLabV3+. (e) SegFormer. (f) Swin-UNet. (g) RSMamba. (h) VM-UNetV2. (i) BuildFormer. (j) UANet. (k) EGAFNet. (l) ours.

Overall, TriadFlow-Net’s predictions align closely with the ground-truth annotations. It not only maintains excellent segmentation accuracy under extreme conditions such as high-confusion backgrounds and severe occlusions but also exhibits exceptional capability in finely resolving minute structures (e.g., narrow gaps and small-scale buildings). This further validates the practicality of the proposed architecture for remote sensing building extraction tasks.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ablation Study

This section conducts a systematic ablation study to validate the effectiveness of TriadFlow-Net’s design strategies and the key components of its modules. The experiments were conducted on the WHU, Massachusetts, and Inria datasets to ensure stable and statistically reliable results. The baseline model adopts ResNet50 as the backbone encoder and includes a complete decoder structure, but excludes the MAFEM, GCMM, and LDEM modules. All the experimental conditions were consistent with those in Section 2.2.

As shown in Table 2, the progressive integration of each module consistently yields measurable and consistent performance improvements, with the observed gains closely aligned with the intended functionality of each component, and it can clearly distinguish the contribution of each module and its interaction gain.

Table 2.

Ablation results on the test dataset.

On the WHU building dataset, the introduction of MAFEM improved IoU by 0.81%. On the Massachusetts building dataset with high building density, IoU improved by 1.18%, and even on the more diverse and complex Inria Aerial Image Labeling dataset, the improvement reached 3.10%. This result demonstrates the design merit of MAFEM, validating its adaptive multi-scale perception capability’s enhanced robustness in addressing challenges, including architectural morphological diversity, large-scale span, and strong background interference. When GCMM is incorporated alone, it achieves an IoU improvement of 4.11% on Inria, substantially higher than that of MAFEM, highlighting the critical role of global semantic consistency for discrimination in complex backgrounds. The improvement in Precision is particularly pronounced, demonstrating that global contextual modeling effectively suppresses false detections from background regions. In contrast, when LDEM is introduced alone, the performance gain is marginal. However, upon further integrating GCMM, the F1 score significantly improves to 95.03%, demonstrating a strong synergistic effect between LDEM and GCMM. This indicates that their combination can help the network to use the boundary information more efficiently in the spatial modeling. Similarly, the combination of MAFEM and GCMM achieves an IoU of 83.02% on the Inria Aerial Image Labeling dataset, which represents a further improvement over either module used alone. This result validates the necessity of jointly modeling local and global contextual information. Finally, the addition of LDEM leads to a significant increase in Recall while leaving Precision nearly unchanged. This is because it effectively recovers fine architectural details or boundary pixels lost due to downsampling, without introducing additional false alarms. After these modules are integrated into the backbone, the network’s metrics like IoU and F1 score gradually improve, with the enhancement significantly exceeding the sum of individual module gains. This nonlinear gain phenomenon indicates that the three modules do not contribute independently but rather produce synergistic effects through feature interactions.

4.2. Effectiveness Analysis of MAFEM

To validate the contribution of each component within MAFEM, we design four controlled experiments on the WHU building dataset:

Case 1: Directly feed the fused feature into the decoder as the baseline;

Case 2: Add multi-scale Neighborhood Attention (NA) branches without the identity branch;

Case 3:Add the identity branch on top of Case 2;

Case 4: Full MAFEM (complete module).

As shown in Table 3, the IoU increases by 0.26% from Case 1 to Case 2, demonstrating that multi-scale non-local modeling enhances contextual representation. Upon introducing the identity branch (Case 3), IoU further increases to 90.46%, accompanied by a notable gain in Recall. This indicates that the identity branch effectively mitigates potential detail suppression caused by attention mechanisms. Case 4 achieves the optimal performance among the four configurations, validating the necessity of the synergistic design between multi-scale attention and the identity branch: the former captures long-range dependencies and cross-scale semantics, while the latter preserves the integrity of local details. This combination collectively enhances segmentation boundary precision and the recall capability for small objects.

Table 3.

Ablation results about MAFEM on the WHU building dataset.

4.3. Effectiveness Analysis of GCMM

To validate the effectiveness of the GCMM design, we conduct seven ablation experiments on the WHU dataset:

Case 1: Baseline model without any NC-SSD module;

Case 2: Stack 1 layer of NC-SSD;

Case 3: Stack 2 layers of NC-SSD;

Case 4: Stack 3 layers of NC-SSD;

Case 5: Stack 4 layers of NC-SSD;

Case 6: Embed DCDF between NC-SSD layers based on Case 4;

Case 7: Embed DCDF between NC-SSD layers based on Case 5.

As shown in Table 4, introducing a single NC-SSD layer (Case 2) yields almost no performance gain, indicating that shallow global modeling is insufficient to capture the complex contextual structures in remote sensing imagery. As the number of NC-SSD layers increases to three (Case 4), IoU rises to 90.01%, and Recall improves by 0.18%, demonstrating that deeper non-causal state-space modeling progressively enhances long-range dependency modeling. However, further stacking to four layers (Case 5) leads to a slight drop in IoU, suggesting that performance saturates—and may even degrade slightly—with excessive depth.

Table 4.

Ablation results about GCMM on the WHU building dataset.

The integration of DCDF significantly improves performance, confirming that DCDF effectively alleviates representation collapse through dense cross-layer connections. Notably, Precision remains stable after introducing DCDF, indicating that the multi-layer fusion mechanism does not introduce additional false positives from background regions. This validates the efficacy of DCDF’s dynamic fusion strategy in preserving discriminative feature diversity without compromising prediction reliability.

4.4. Effectiveness Analysis of LDEM

To validate the effectiveness of LDEM, we design three controlled experiments on the WHU dataset:

Case 1: Baseline model without any LDEM module;

Case 2: Incorporate Multi-scale High-Frequency Extraction (MHFE) with gated adaptive fusion, but without channel–spatial collaborative attention;

Case 3: Full LDEM (complete module).

As shown in Table 5, introducing only MHFE and gated fusion (Case 2) already improves Recall, demonstrating that multi-scale high-frequency residuals effectively compensate for local details lost during downsampling. However, Precision slightly decreases, suggesting that directly injecting high-frequency components may introduce minor noise or non-discriminative responses.

Table 5.

Ablation results about LDEM on the WHU building dataset.

When the channel–spatial collaborative attention mechanism is further integrated (Case 3), Recall further increases to 95.03%, while Precision rebounds to 95.20%, yielding an IoU of 90.69%. This trend confirms that the attention mechanism selectively enhances boundary and small-building regions while suppressing spurious or irrelevant activations, thereby enabling precise and robust detail recovery.

4.5. Analysis of Different Encoders

TriadFlow-Net is highly versatile and can be adapted to various encoder-decoder architectures to further enhance performance. To validate its effectiveness, we conducted ablation experiments using ResNet50, ConvNeXt-B, and SwinV2-B as the backbone networks of the encoder-decoder framework. As shown in Table 6, TriadFlow-Net demonstrates excellent segmentation performance across different backbone configurations. Considering that most existing remote sensing building segmentation methods adopt ResNet50 as the baseline backbone, we also use ResNet50 as our baseline to ensure a fair comparison with current approaches.

Table 6.

Ablation results of different encoders on the WHU building dataset.

4.6. Model Complexity Analysis

To comprehensively assess the practical performance of TriadFlow-Net, we conducted a systematic comparison of all baseline methods under a unified experimental setting, taking into account multiple metrics, including the number of parameters, computational complexity, segmentation accuracy, and inference speed as shown in Table 7. Inference speed was measured on a laptop equipped with an RTX 3070 GPU. Input images were fixed at a resolution of 512 × 512 with a batch size of 1. After performing 10 warm-up iterations, we averaged the latency over 100 inference runs and computed the frames per second (FPS) using the formula: FPS = 1/average inference time.

Table 7.

Comparison of the model complexity of different methods.

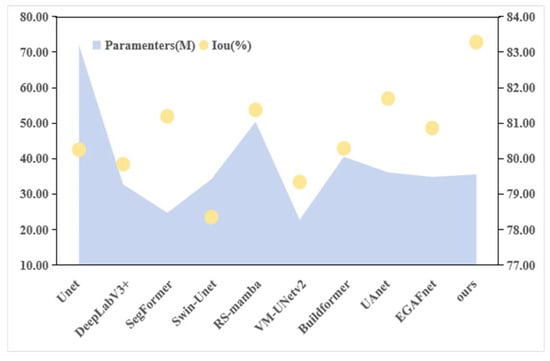

Figure 8 plots the Intersection over Union (IoU) on the Inria Aerial Image Labeling dataset—used as the accuracy metric—against the number of model parameters for each method. The results show that although VM-UNetV2 and SegFormer rank first and second in terms of parameter count, their segmentation accuracies (IoU) are relatively low. In contrast, the proposed model achieves state-of-the-art segmentation performance while maintaining a low number of parameters and moderate computational complexity. Although its inference speed is slightly lower than that of some lightweight models, its overall efficiency remains within a practically acceptable range, demonstrating an effective balance between performance and resource consumption. Overall, TriadFlow-Net adopts a rational computational resource allocation strategy: computationally intensive semantic feature extraction is primarily concentrated in the lower layers of the network, while the upper decoding stages focus on high-frequency detail recovery and boundary refinement. This design maximizes segmentation accuracy under constrained model size and effectively avoids redundant computation, thereby enhancing both overall efficiency and practical applicability.

Figure 8.

Complexity and accuracy comparison of TriadFlow-Net and the comparison methods.

5. Conclusions

The proposed TriadFlow-Net framework achieves significant performance gains in building extraction from high-resolution remote sensing imagery by jointly modeling multi-scale context, global dependencies, and local details. In contrast to existing approaches that often trade off between contextual understanding and fine-grained boundary preservation, TriadFlow-Net establishes an information-complementary and computationally efficient feature refinement pipeline through three core modules. Specifically, MAFEM strengthens semantic consistency across hierarchical feature levels; GCMM captures long-range spatial dependencies with linear complexity while mitigating feature homogenization in deep layers; and LDEM precisely recovers structural boundaries through multi-head feature enhancement combined with a channel-spatial attention mechanism. Extensive experiments on three public benchmarks demonstrate that this design not only outperforms state-of-the-art methods but also strikes an effective balance between model complexity and segmentation accuracy. More importantly, this work reveals that in high-resolution remote sensing semantic segmentation, contextual modeling, global dependency learning, and local detail preservation are not isolated optimization objectives; rather, they can be jointly enhanced through a structured collaborative mechanism. This insight provides a new paradigm for the design of future high-precision building extraction models in remote sensing.

Although TriadFlow-Net demonstrates strong performance, this study still has several avenues for future extension. First, in the Inria Aerial Image Labeling dataset, TriadFlow-Net occasionally misclassifies certain road regions as buildings, particularly in areas where roads and buildings are adjacent. This issue primarily stems from the inherent spectral ambiguity in remote sensing imagery. Despite the boundary-detail enhancement capability of TriadFlow-Net’s LDEM module, it cannot fully resolve the confusion caused by highly similar spectral signatures between roads and rooftops. To address this, future work will explore multispectral or hyperspectral data fusion strategies to leverage richer spectral information for better discrimination between roads and roofs. And this study is based solely on optical remote sensing imagery, whereas multi-modal data such as SAR and LiDAR can provide complementary geometric and physical information. Consequently, our next step will involve designing cross-modal feature fusion mechanisms to fully leverage the complementary information from different sensors, thereby enhancing the robustness and accuracy of building extraction. Moreover, for buildings smaller than 10 × 10 pixels, the model either completely ignores them or merges them into the background. This reflects a fundamental contradiction in high-resolution remote sensing imagery between “pixel-level accuracy” and “object scale.” Future work will explore sub-pixel-level feature extraction methods combined with super-resolution techniques to enhance the visibility of such tiny targets.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Z.Z. and Y.Z.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Z.Z., Y.Z. and R.Y.; formal analysis, D.Y.; data curation, Z.Z. and D.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z., Y.Z. and R.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.Y.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, D.Y.; project administration, Z.Z.; funding acquisition, D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52174160) and priority projects for the “Science and Technology for the Development of Mongolia” initiative in 2023 (ZD20232304).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author, Mr. Renxu Yang, is from PipeChina Engineering Technology Innovation Co., Ltd., Tianjin 300450, China. There is no conflict of interest between the affiliation and the manuscript.

References

- Wang, Z.Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.X.; Wang, F.; Xu, Z. House building extraction from high-resolution remote sensing images based on IEUN. J. Remote. Sens. 2021, 25, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.M.; Ahmad, A.; Paul, A.; Rho, S. Urban planning and building smart cities based on the Internet of Things using big data analytics. Comput. Netw. 2016, 101, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, A.; Zhang, L. Building damage assessment for rapid disaster response with a deep object-based semantic change detection framework: From natural disasters to man-made disasters. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sun, K.; Zhao, H.; Li, W.; Wei, J.; Gao, S. Extracting buildings from high-resolution remote sensing images by deep ConvNets equipped with structural-cue-guided feature alignment. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 113, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wu, F.; Qian, H.; Zhai, R.; Gong, X.; Yin, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, A. AFL-net: Attentional feature learning network for building extraction from remote sensing images. Remote. Sens. 2022, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awrangjeb, M.; Zhang, C.; Fraser, C.S. Improved building detection using texture information. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, XXXVIII-3/W22, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Luo, J.; Shen, Z.; Zhu, Z. Building extraction from high resolution remote sensing imagery based on spatial–spectral method. Geomatics Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2012, 37, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelhamer, E.; Long, J.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 9351, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, Atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.Y.; Ming, W.; Chuang, Z. Multi-Scale Representations by Varying Window Attention for Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.16573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.-P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liao, Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, L. A local–global dual-stream network for building extraction from very-high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 33, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, G.; He, G.; Long, T.; Yin, R.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Luo, B. Robust building extraction for high spatial resolution remote sensing images with self-attention network. Sensors 2020, 20, 7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yu, Y.; Gu, L.; Lin, T.; Tao, X. VM-UNET-V2: Rethinking Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.09157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fang, S.; Meng, X.; Li, R. Building extraction with vision transformer. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2022, 60, 3186634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, W.; Cao, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H. UANet: An uncertainty-aware network for building extraction from remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2024, 62, 5608513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2111.00396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharopoulos, A.; Vyas, A.; Pappas, N.; Fleuret, F. Transformers are RNNs: Fast Autoregressive Transformers with Linear Attention. arXiv 2006, arXiv:2006.16236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.; Gu, A. Transformers are SSMs: Generalized models and efficient algorithms through structured state space duality. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.21060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.Y.; Dao, T.; Saab, K.K.; Thomas, A.W.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. Hungry hungry hippos: Towards language modeling with state space models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2212.14052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, L.; Ye, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y. VMamba: Visual State Space Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.H.; Liao, B.C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision mamba: Efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Liu, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, D.; Zheng, H.; Jiang, F. Context–content collaborative network for building extraction from high-resolution imagery. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 263, 110283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Du, B.; Zhang, L.; Su, X. A coarse-to-fine boundary refinement network for building footprint extraction from remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2022, 183, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wei, S.; Lu, M. Fully convolutional networks for multisource building extraction from an open aerial and satellite imagery dataset. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2018, 57, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V. Machine Learning for Aerial Image Labeling. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori, E.; Tarabalka, Y.; Charpiat, G.; Alliez, P. Can semantic labeling methods generalize to any city? The Inria aerial image labeling benchmark. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3226–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Fixing Weight Decay Regularization in Adam. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Z.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z.G. Learning to Upsample by Learning to Sample. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 6004–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Steven, W.; Jiachen, L.; Shen, L.; Humphrey, S. Neighborhood Attention Transformer. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2204.07143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Humphrey, S. Dilated Neighborhood Attention Transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.15001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Hwu, W.-M.; Humphrey, S. Faster Neighborhood Attention: Reducing the O(n^2) Cost of Self Attention at the Threadblock Level. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.04690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Zhou, F.; Kane, A.; Huang, J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Shi, M.; Walton, S.; Hoehnerbach, M.; Thakkar, V.; Isaev, M.; et al. Generalized Neighborhood Attention: Multi-dimensional Sparse Attention at the Speed of Light. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.16922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Chen, W.; Xiong, W.; Xu, X.; Shi, X.; Li, C. SiMultiF: A Remote Sensing Multimodal Semantic Seg-mentation Network with Adaptive Allocation of Modal Weights for Siamese Structures in Multiscene. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2025, 63, 4406817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with Atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In 15th European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Munich, Germany, 2018; pp. 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.15203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet:Unet-likepuretransformerfor medicalimagesegmenta-tion. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2105.05537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Remote Sensing Image Classification with State Space Model. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 8002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.W.; Zhao, L.; Ye, L.; Jia, W.; Jiang, H.; Yang, Z. An Edge Guidance and Scale-Aware Adaptive Fusion Network for Building Extraction from Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2025, 63, 4700513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.