Highlights

What are the main findings?

- MODIS data enabled the first continuous, pixel-based assessment of long-term snow cover dynamics across the Romanian Carpathians (2000–2025).

- Observations revealed a clear shift in the regional snow regime, with later accumulation and earlier melt leading to reduced seasonal snow persistence.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Shifts in snow timing modify ground thermal regimes and hydrological processes, altering freeze–thaw cycles, runoff patterns, and seasonal water availability, thereby increasing the vulnerability of Carpathian periglacial and hydrological systems under ongoing climate warming.

- Earlier snowmelt modifies snow–soil–atmosphere coupling, favoring competitive generalist species over snow-adapted cold species and contributing to biodiversity loss and progressive ecosystem homogenization.

Abstract

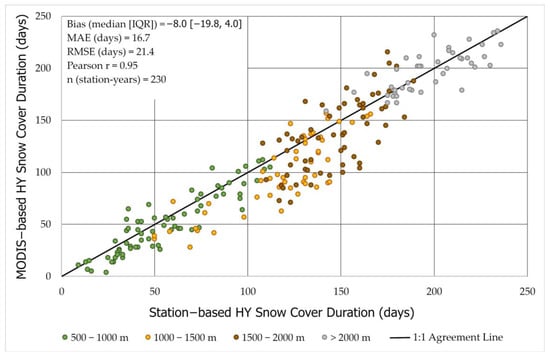

Understanding long-term snow cover dynamics is essential in mountain regions with limited meteorological or in situ observations. This study examines seasonal snow cover evolution across the Romanian Carpathians (2000–2025) using daily MODIS/Terra MOD10A1 Cloud-Gap-Filled data at 500 m resolution. Snow-covered pixels were identified using an NDSI ≥ 40 threshold, and snow cover duration (SCD), snow onset date (SOD), and snow end date (SED) were analyzed in relation to elevation and aspect from the FABDEM, complemented by snow-covered area (SCA) and snowline elevation (SLE) metrics. Across the entire range, the snow season shortens mainly due to later onset (+0.28 days/year) and earlier melt (−0.78 days/year), resulting in an SCD decrease of −1.14 days/year. High-elevation (>2000 m) areas show only small changes (SCD: −0.13 days/year; SOD: +0.46 days/year; SED: +0.32 days/year), while the strongest reductions occur at low and mid elevations, where snow persistence is most sensitive to warming; consistent declines in seasonal SCA and a pronounced monthly SLE cycle further document the spatial expression of this variability. Uncertainty was assessed by comparison with station-based snow cover duration (n = 230 station-years), indicating strong agreement (r = 0.95) with a modest negative bias (median: −8 days) and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 16.7 days. Climate correlations highlight air temperature as the dominant covariate of interannual snow-phenology variability, whereas precipitation associations are weaker. Overall, these shifts in snow phenology highlight increasing instability of the Carpathian snow regime and emphasize the value of long-term MODIS observations for tracking cryospheric change in a warming southeastern European mountain system.

1. Introduction

Snow cover is a key component of the Earth’s climate system, seasonally blanketing nearly half of the Northern Hemisphere during winter [1]. Its high albedo strongly affects the surface energy balance by reflecting incoming solar radiation, thereby producing a cooling effect at regional and global scales [2]. Beyond its radiative influence, snow plays a central role in hydrological processes, acting as a temporary water reservoir that regulates both timing and magnitude of runoff [3], while also supporting ecological functioning across diverse environments [4]. In mountainous regions, persistent snow cover contributes to glacier mass balance and provides thermal insulation for soils, affecting permafrost occurrence and stability [5].

The seasonal dynamics of snow cover, commonly referred to as snow cover phenology, govern the timing of accumulation and melt, with important consequences for both natural and human systems. Shifts in snow onset, persistence, or melt timing can alter habitat conditions, disrupt ecosystem processes, and impact species adapted to specific seasonal cycles [6]. From a socio-economic perspective, snow cover is vital for maintaining freshwater resources, supporting agricultural irrigation, industrial activities, hydropower production, and winter tourism, particularly in alpine regions where meltwater represents a key water supply during warmer months [7,8].

Ongoing climate warming has increasingly altered snow regimes worldwide [9]. Rising air temperatures have shifted precipitation from snow to rain and accelerated spring melt, resulting in widespread reductions in snow cover duration and extent [8,10]. At the hemispheric scale, snow cover across large areas of the Northern Hemisphere is now approximately one month shorter than it was four decades ago [11]. Such changes have been widely documented in mountain regions, where declining snow persistence and depth influence runoff dynamics, increase hydrological variability, and may enhance the likelihood of hazards such as floods or snowmelt-driven mass movements [12,13,14].

Although long-term snow observations have traditionally relied on ground-based meteorological stations, such records are often spatially sparse and unevenly distributed, particularly in high-elevation areas. Consequently, satellite remote sensing has become an essential tool for monitoring snow cover at regional to continental scales [15]. Since 2000, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) has provided consistent, near-daily observations of snow cover, enabling detailed analyses of its spatial distribution and temporal variability [16]. MODIS snow products, particularly cloud-gap-filled (CGF) datasets, have been extensively validated and applied in mountainous environments, offering a valuable balance between spatial resolution and temporal continuity [17,18,19,20].

Importantly, satellite products not only extend spatial coverage, but also enable analyses that are difficult to achieve with station networks alone [21]. While weather station records provide high-quality point measurements, sparse and uneven distribution in complex mountain terrain limits the ability to resolve sharp spatial gradients and within-elevation heterogeneity in snow persistence and timing. By contrast, pixel-level MODIS CGF time series provide spatially continuous snow phenology fields, allowing consistent stratification of snow cover duration (SCD), snow onset date (SOD) and snow end date (SED) across elevation and exposure classes, the detection of localized anomalies driven by terrain effects, and the derivation of region-wide diagnostics such as snow-covered area (SCA) and snowline elevation (SLE) [22,23]. This spatially explicit framework enhances the interpretation of long-term changes by linking trends to topographic controls and quantifying variability that cannot be captured by a limited set of weather stations.

Recent studies based on MODIS data have revealed complex patterns of snow cover change across different mountain systems. While many regions exhibit a clear decline in snow cover duration linked to rising temperatures, other areas display more heterogeneous responses depending on elevation, exposure, and regional climate conditions [24,25]. These results underscore the need for region-specific analyses that explicitly account for topographic and climatic controls.

Although snow is a fundamental component of the cryosphere, the response of the Eastern European cryosphere to climate change remains poorly studied, highlighting the urgent need for long-term observations to better understand and predict its dynamics [26]. Within Europe, the Romanian Carpathians represent a key climatic region due to a more pronounced continentality than in Central and Western Europe, with larger annual temperature ranges and moderately lower precipitation. While westerly air masses dominate, local topography strongly modulates precipitation patterns [27], influencing snow persistence and periglacial processes. Despite this significance, research on snow cover dynamics in the Romanian Carpathians remains limited in both spatial and temporal scope. The scarcity of high-elevation monitoring infrastructure, restricted winter accessibility, and limited integration of modern geospatial techniques have resulted in significant data gaps. Existing studies have largely relied on isolated, point-based meteorological records, providing only a partial view of regional variability in snow accumulation, persistence, and melt [28,29]. Moreover, systematic validation of satellite-derived snow products and their integration with topographic parameters remain underdeveloped, particularly in alpine and periglacial environments where snow exerts a critical control on ground thermal conditions.

In this context, the present study provides the first comprehensive, multi-decadal assessment of snow cover phenology across the entire Romanian Carpathians for the period 2000–2025 using MODIS Terra CGF. We quantify key metrics—SCD, SOD, SED—and assess their spatial distribution, interannual variability, and long-term trends in relation to topography. To complement pixel-based phenology, we also characterize regional snow-regime expression using SCA and SLE diagnostics, and examine climatic co-variability using temperature and precipitation indicators. By addressing these objectives, the study closes a longstanding gap in the quantitative understanding of Carpathian snow dynamics and provides a robust baseline for future climate and cryospheric research including investigations of snow–ground thermal coupling and the sensitivity of periglacial processes to snow variations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

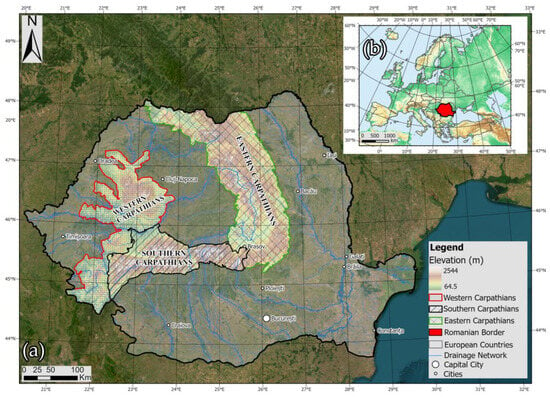

Between 45 and 48°N latitude, the Romanian sector of the Carpathians defines a mid-latitude mountain system within the temperate climatic belt of Europe. As they lie between the oceanic climates of Western Europe and the arid continental regions of interior Asia, the Carpathians can be regarded as an important sector of the Eurasian climate system. For climatic studies, this intermediary setting makes the range a key region for documenting changes in large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns and their expression in spatial gradients of precipitation [30].

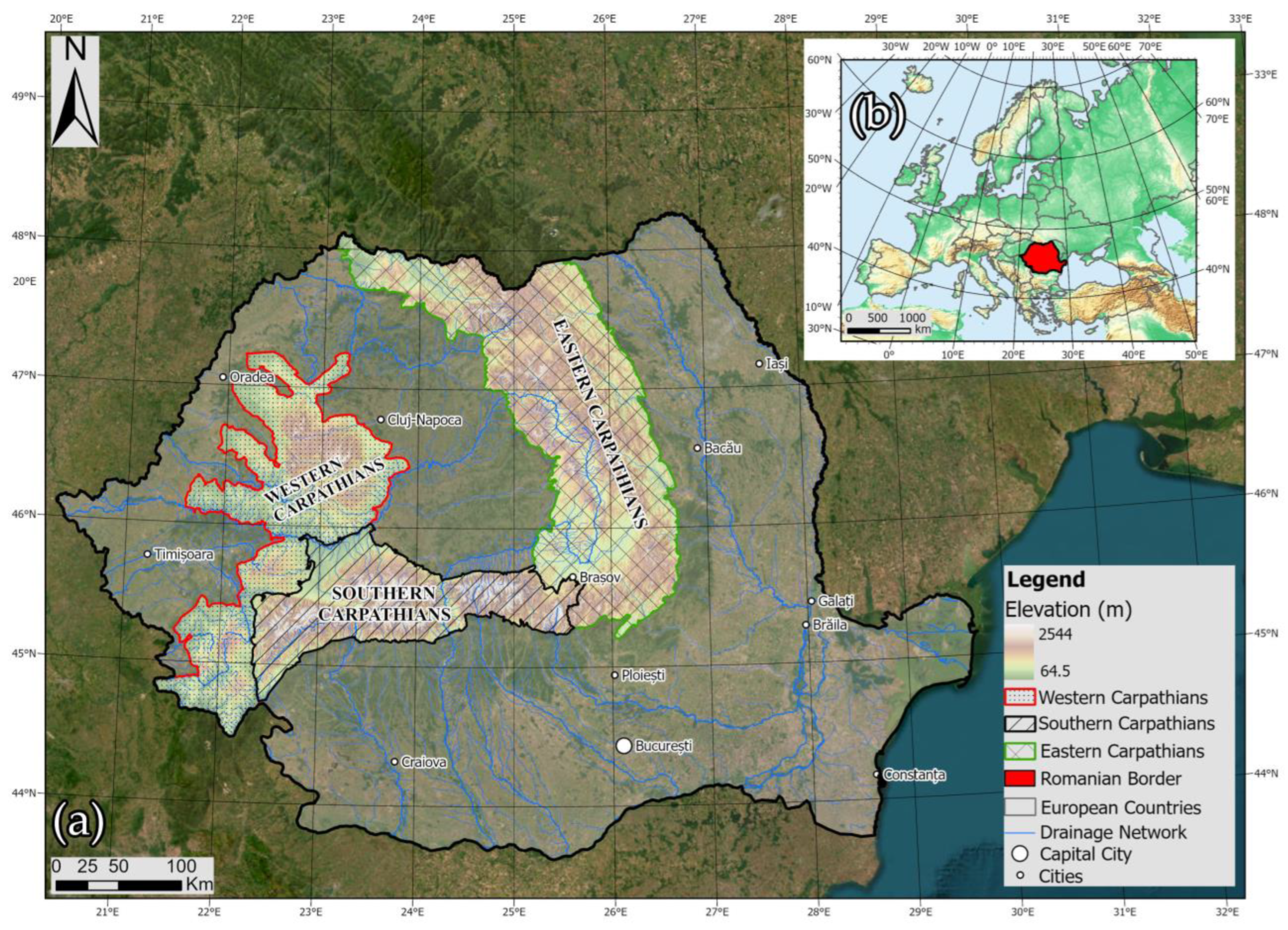

The Romanian Carpathians represent the most extensive sector of the Carpathian orogenic system, extending for approximately 910 km, about 54% of the range’s total length and encompassing 66,303 km2, accounting for 40.9% of the total Carpathian area and 27.8% of Romania’s national territory [27]. The Romanian Carpathians are conventionally subdivided into three major units, each characterized by distinct physical–geographical conditions: the Eastern Carpathians (33,584 km2), the Southern Carpathians (15,000 km2), and the Western Carpathians (17,714 km2) [27].

Within the Romanian sector of the Carpathians, the maximum elevation is represented by Moldoveanu Peak (2544 m) in the Southern Carpathians. Based on the Forests and Buildings Removed Digital Terrain Model (FABDEM), the Carpathians have an average elevation of 871 m a.s.l. (Figure 1). Approximately 80% of the Romanian Carpathians lie below 1200 m, while elevations above 2500 m are limited to four isolated high-mountain ranges all located in the Southern Carpathians. At the summits of the highest peaks, the mean annual temperature averages −2 °C, with annual precipitation near 1000 mm. Currently, the Southern Carpathians no longer host glaciers or perennial snow patches; however, isolated permafrost remains above 2000 m at topographically and climatically suitable locations [31].

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the study area within Romania and (b) its geographical context at the European continental scale.

Across the Romanian sector, the Carpathians are characterized by one of the most intricate lithological and structural configurations along the range. In this area, the mountain system exceeds 130 km in width and forms a pronounced curvature, with the orientation of the main crests changing abruptly from NNW–SSE in the Eastern Carpathians to an E–W direction in the Southern Carpathians, and then from south to north in the Western Carpathians [27].

2.2. MODIS Snow Cover Data and Elevation Input

Snow cover dynamics were analyzed using data from MODIS onboard NASA’s Terra satellite (launched 18 December 1999). Terra overpasses Romania daily at ~12:20–12:30 local time, generally providing more favorable illumination in complex mountain terrain than Aqua (launched 4 May 2002), whose afternoon overpass (~15:30) can increase terrain shadowing, particularly on north-facing slopes. The MODIS instruments acquire daily global observations in 36 spectral bands spanning 0.4–14.4 μm [32,33]. Snow detection is primarily based on the Normalized Difference Snow Index (NDSI), computed from green (G) (0.545–0.565 μm) and near-infrared (NIR) (1.628–1.652 μm) reflectance, according to the formula [34]

We used the MOD10A1F product (MODIS/Terra Cloud-Gap-Filled Snow Cover Daily L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid, Version 6.1), which provides daily global snow cover maps at 500 m spatial resolution in the global sinusoidal projection [35]. MOD10A1F spans from 24 February 2000 to present and is distributed in HDF-EOS2 format. All tiles covering the Romanian Carpathians were obtained from NASA EarthData via the National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (NSIDC-DAAC—https://nsidc.org/data/mod10a1f/versions/61, last accessed on 1 November 2025). From each file, we extracted exclusively the CGF_NDSI_Snow_Cover layer, which underpins all subsequent snow metrics.

Given the optical nature of MODIS observations, cloud contamination is a major source of uncertainty in snow-detection accuracy. MOD10A1F mitigates this limitation using a cloud-gap-filled (CGF) procedure implemented as temporal carry-forward (retention): when a pixel is classified as cloud on a given day, the product replaces it by retaining the most recent prior clear-sky observation for the same pixel from preceding days [36]. The product includes a companion quality layer reporting the cloud persistence (or the number of days since the last clear-sky retrieval), allowing the observation age of the retained value to be assessed. In this study, we used the CGF snow classification as provided to maximize spatial completeness and did not apply additional filtering based on the persistence/age information; accordingly, during prolonged cloudy periods, the carry-forward mechanism may introduce temporal lag in the day-of-year assigned to snow transitions, which is most relevant for SOD/SED during rapid onset and melt phases. By contrast, seasonal aggregates and long-term trend patterns are expected to be less sensitive to short persistence intervals, while the CGF approach substantially reduces missing data in MODIS snow time series and supports robust multiannual analyses [21].

To analyze morphometric controls and quantify topographic influences on snow cover characteristics, we used the FABDEM at 30 m spatial resolution [37]. The digital elevation model served as the reference surface from which we derived elevation and aspect, and it also underpinned the terrain descriptors used to stratify and interpret snow metrics. Prior to integration with MODIS, the DEM and its derivative layers were resampled to the 500 m grid of the MODIS snow products (ensuring common projection, alignment, and pixel size), so that each MODIS pixel could be consistently associated with corresponding topographic attributes. These variables were then used to (i) stratify snow cover duration and phenology metrics (SCD, SOD, SED) across elevation and exposure classes, (ii) support correlation and statistical analyses of snow–topography relationships, and (iii) provide the topographic basis for spatial diagnostics derived from the MODIS time series, including snow-covered area (SCA) summaries and snowline elevation (SLE) characterization.

2.3. Data Processing and Derived Snow Cover Indices

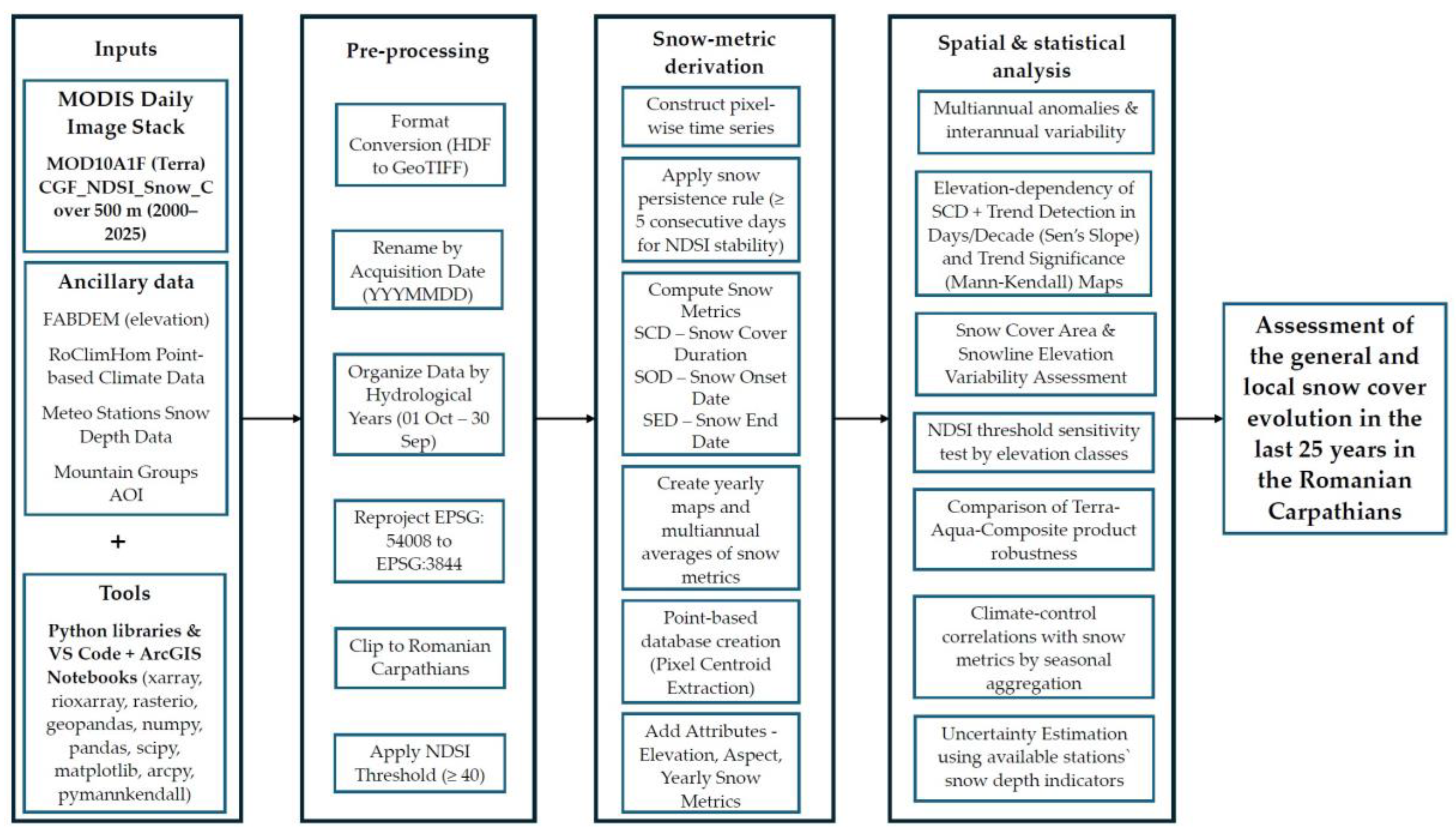

Pre-processing of the MODIS/Terra CGF snow cover dataset was designed to standardize the daily time series and prepare a consistent raster stack for the derivation of snow metrics and subsequent spatial analyses. Processing covered the 2000–2025 period and produced a harmonized, Python-readable (version 3.10.) raster database. Input files were automatically renamed using the acquisition date (YYYYMMDD) to ensure chronological consistency and to support fully automated time-series operations.

All scenes were converted from HDF-EOS2 to GeoTIFF format by extracting the CGF_NDSI_Snow_Cover layer. The resulting rasters were reprojected from the MODIS sinusoidal grid (EPSG: 54008) to the Romanian national projection Stereo 70 (Pulkovo 1942(58), EPSG:3844) and clipped to the Romanian Carpathians using a mountain-relief mask (https://geo-spatial.org/vechi/download/harta-unitati-relief-romania, last accessed on 10 November 2025), ensuring compatibility with ancillary datasets. The masked daily rasters formed the basis for computing all snow indicators and their spatial summaries.

Snow presence was identified using the widely applied threshold of NDSI ≥ 0.4 [38], which is generally appropriate for 500 m MODIS snow products [39,40]. In the MOD10A1F dataset, the CGF_NDSI_Snow_Cover layer is provided as a scaled integer (0–100) [20]; therefore, the snow criterion was applied to the product’s scaled values as NDSI ≥ 40 (equivalent to NDSI ≥ 0.4 in the conventional −1 to 1 range) [36]. Based on this classification scheme, pixel-wise daily series were assembled for each hydrological year (1 October–30 September) and used to compute three phenology metrics: (i) snow cover duration (SCD), defined as the number of snow days per hydrological year [41]; (ii) snow onset date (SOD), defined as the first day of the snow season; and (iii) snow end date (SED), defined as the last day of the snow season [42].

Although optimal thresholds can vary with land cover, elevation, terrain shading, and season—often tending toward lower values in forested/mixed pixels [43]—a fixed threshold ensures methodological consistency and comparability across the full multi-decadal record. To quantify sensitivity to threshold choice, we repeated the full workflow using scaled thresholds of 30 (T30), 35 (T35), 40 (T40) and 45 (T45), and evaluated differences in SCD, SOD and SED (offsets and trend robustness) relative to the T40 baseline across five elevation classes (≤500, 500–1000, 1000–1500, 1500–2000, >2000 m).

To reduce sensitivity to short snowfall events in autumn and brief melt interruptions or late-season return snow in spring, we applied a 5-day persistence criterion [44,45]. Specifically, SOD was assigned as the first day of the first sequence of ≥5 consecutive snow days (NDSI ≥ 40), and SED as the last day preceding a sequence of ≥5 consecutive non-snow days (NDSI < 40); SCD was computed as the annual count of snow days, with persistence filtering applied for transition-date stability. This approach ensured that all metrics reflected stable and meaningful snowpack dynamics [24,25].

All steps—format conversion, reprojection, clipping, file organization, and metric computation—were automated in a Python 3.10 environment (Visual Studio Code v. 1.107), using GDAL, rasterio, rioxarray, xarray, numpy, pandas, geopandas, scipy and matplotlib [46]. In total, 9291 rasters were processed. Final visual quality checks were performed in ArcGIS Pro 3.3.0 to ensure temporal coherence and data integrity (Figure 2).

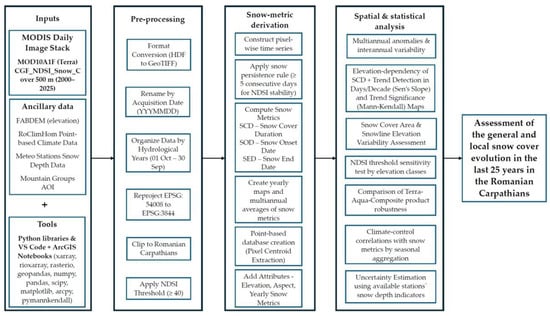

Figure 2.

Methodological workflow for MODIS-based mapping and analysis of snow cover evolution in the Romanian Carpathians.

2.4. Spatial and Statistical Analysis

To support spatially explicit analyses, each 500 m MODIS pixel within the Carpathian mask was represented by its centroid, yielding a point-based geodatabase. For each point, we stored multiannual mean values of SCD, SOD, and SED, as well as annual values for each hydrological year. Each point was linked to topographic attributes derived from FABDEM (elevation, slope, aspect) and assigned to its corresponding mountain group, enabling regional comparisons and physiographic stratification.

This structure allowed analyses across multiple physiographic dimensions. Snow metrics were summarized by elevation bands, mountain units, and aspect classes to quantify spatial contrasts and to examine morphometric controls on snow persistence and timing. Terrain–snow relationships were evaluated using correlation-based statistics, providing a quantitative basis for interpreting topographic influences on snow variability.

Temporal trends were assessed on hydrological-year series using non-parametric methods appropriate for non-normal, heteroscedastic, and outlier-prone environmental data. Monotonic trends were tested with the Mann–Kendall statistic, and trend magnitudes were estimated using the Theil–Sen slope. Statistical significance was evaluated at p < 0.05, and spatial patterns of trend direction and magnitude were mapped to identify areas of decreasing, stable, or increasing snow persistence and shifts in phenology timing.

To examine fine-scale elevation dependence, all points were additionally aggregated into 5 m elevation bands. For each band, we computed percentile statistics (1st, 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 95th, 99th) for each snow metric, as well as deviations from the band mean, to characterize within-band heterogeneity and identify altitudinal breakpoints in snow persistence.

To complement pixel-wise phenology metrics with domain-level diagnostics, we derived snow-covered area (SCA) and a snowline elevation (SLE) indicator for the three major Carpathian units (Western, Eastern, Southern). SCA was computed for each hydrological year as the fraction of the analyzed area classified as snow (NDSI ≥ 40) and aggregated to seasonal windows aligned to the regional snow regime: winter (December–February), spring (March–April), and the full snow season (November–May). For each unit and seasonal window, we constructed interannual SCA series and evaluated linear trends using ordinary least squares regression, reporting slope (% yr−1) and associated fit statistics. To characterize the seasonal migration of the snowline, we combined the snow classification with FABDEM elevations and, for each month of the snow season (November–May) and hydrological year, extracted the elevations of snow-covered pixels within each unit to derive a representative SLE indicator for that month–year. Monthly SLE variability across the study period was summarized using box-and-whisker statistics (median, interquartile range, 1.5 × IQR whiskers, and outliers), enabling comparison of the typical mid-winter lowering and spring rise of the snowline among units.

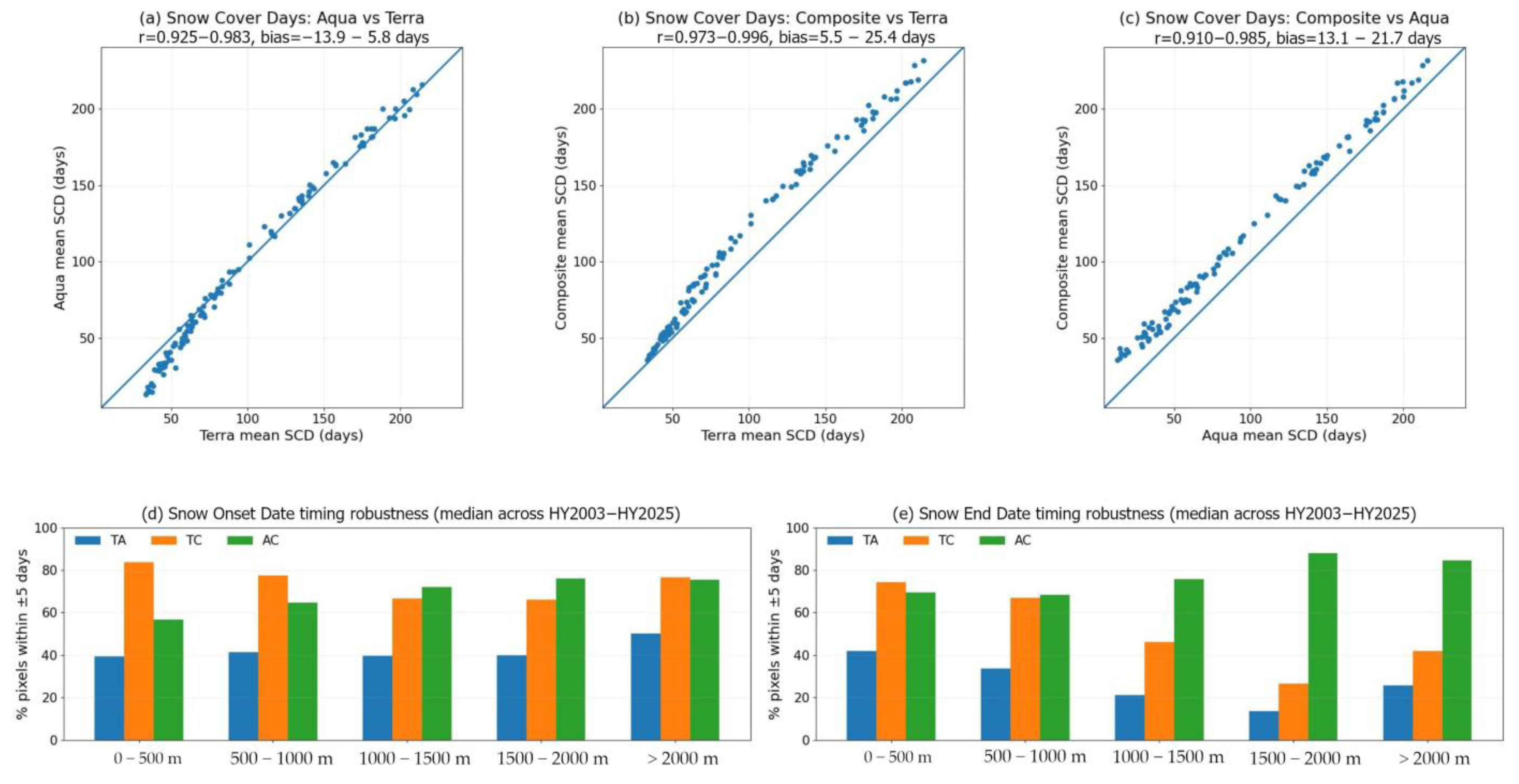

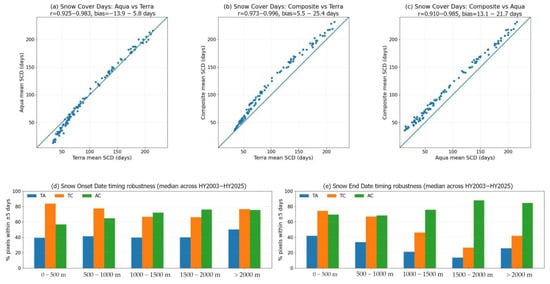

To evaluate the potential influence of platform sampling and illumination differences on derived snow metrics, we extended the workflow to include the MODIS/Aqua CGF snow product and a Terra–Aqua daily composite over the common Aqua availability period (1 October 2002–30 September 2025). Daily, study-area-clipped GeoTIFF time series were generated for Aqua using the same preprocessing steps as for Terra, and a corresponding Terra–Aqua composite was produced for each overlapping date. Using each of the three daily inputs (Terra-only, Aqua-only, composite), we recomputed SCD, SOD, and SED using identical thresholds and persistence rules. Agreement among approaches was assessed through pairwise comparisons of the resulting metric fields (e.g., correlation- and bias-based summaries) and by evaluating the consistency of SOD/SED timing across elevation classes, providing a robustness check on the Terra-only configuration used for the main analyses.

To quantify uncertainty in MODIS-derived snow metrics, we validated satellite-based estimates against several climatic parameters available for Romania during July 2014–September 2025. Daily snow depth data were extracted from MeteoManz (https://www.meteomanz.com/index?l=1, last accessed 24 January 2026), which compiles land SYNOP alphanumeric messages and BUFR observations (WMO standard formats). Using 26 stations spanning 586–2504 m a.s.l. (Table S1), each station was paired with the nearest MODIS 500 m pixel, and both datasets were aggregated to hydrological years. For each station–year, SCD was computed consistently from daily snow presence, and station–MODIS agreement was quantified using Pearson correlation, MAE, RMSE, and bias summarized as the median with interquartile range (IQR). Performance was reported overall and stratified by elevation class. In addition, day-to-day snow occurrence agreement over the snow season (October–May) was evaluated using the F1 score, defined as the harmonic mean of precision (the fraction of MODIS snow days that are also snow at the station) and recall (the fraction of station snow days correctly detected by MODIS) and summarized by elevation class. For phenology timing, station-based SOD and SED were derived using the same 5-day persistence rule applied to MODIS to ensure comparability; timing differences were summarized using bias and MAE by elevation class.

To support interpretation of snow-phenology variability and trends, seasonal air temperature and precipitation were extracted from observations at 43 meteorological stations compiled in a homogenized Romanian climate dataset for 2000–2023 [47]. For each hydrological year, station observations were aggregated into seasonal windows selected to match the primary climatic sensitivity of each metric: November–May for SCD, September–November for SOD, and March–May for SED. Interannual climate variability was summarized as the median across stations and compared to the median snow metric across all snow-metric points; associations were quantified using Spearman rank correlation. To examine relationships beyond the regional-median signal, we also performed station–year pairing by linking each station’s seasonal climate values with the snow-metric value sampled at the station location for the same year, enabling correlation analysis across the full station–year sample. Finally, to provide spatial context for regional climate change, gridded E-OBS temperature and precipitation fields (9 km; reprojected to EPSG:3844 and clipped to the study mask) were used to compute Sen’s slope (per decade) for the cold-season window (November–May) over 2000–2023 [48].

2.5. Usage of AI

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) was used in this study to assist with several technical and editorial tasks. Specifically, AI tools were employed to generate and refine Python scripts for automating data processing workflows, including data preparation, organization, and the computation of spatio-temporal statistics for snow cover regime indices following the generation of snow-phenology metrics in GIS format. In addition, GenAI was used to edit and rephrase portions of the manuscript to improve clarity and coherence. No GenAI tools were used to generate research data, perform scientific interpretation, or design the study.

3. Results

3.1. Multiannual Snow Cover Metrics of the Romanian Carpathians

Based on the full centroid-extracted dataset of 398,248 grid points covering the Romanian Carpathians, the 25-year multiannual statistics indicate an average SCD of 48.2 days, with a median of 39.9 days and a standard deviation of 34.8 days. The multiannual mean SOD is 82.8 ± 15.8 days of the hydrological year, while the mean SED occurs on day 151.9 ± 8.3. Elevation-class statistics summarizing the multiannual means, medians, and standard deviations for SCD, SOD, and SED are reported in Table 1, with the corresponding spatial patterns illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Multiannual mean, median, and standard deviation of SCD, SOD, and SED for the Romanian Carpathians (2000–2025), summarized by 500 m elevation thresholds.

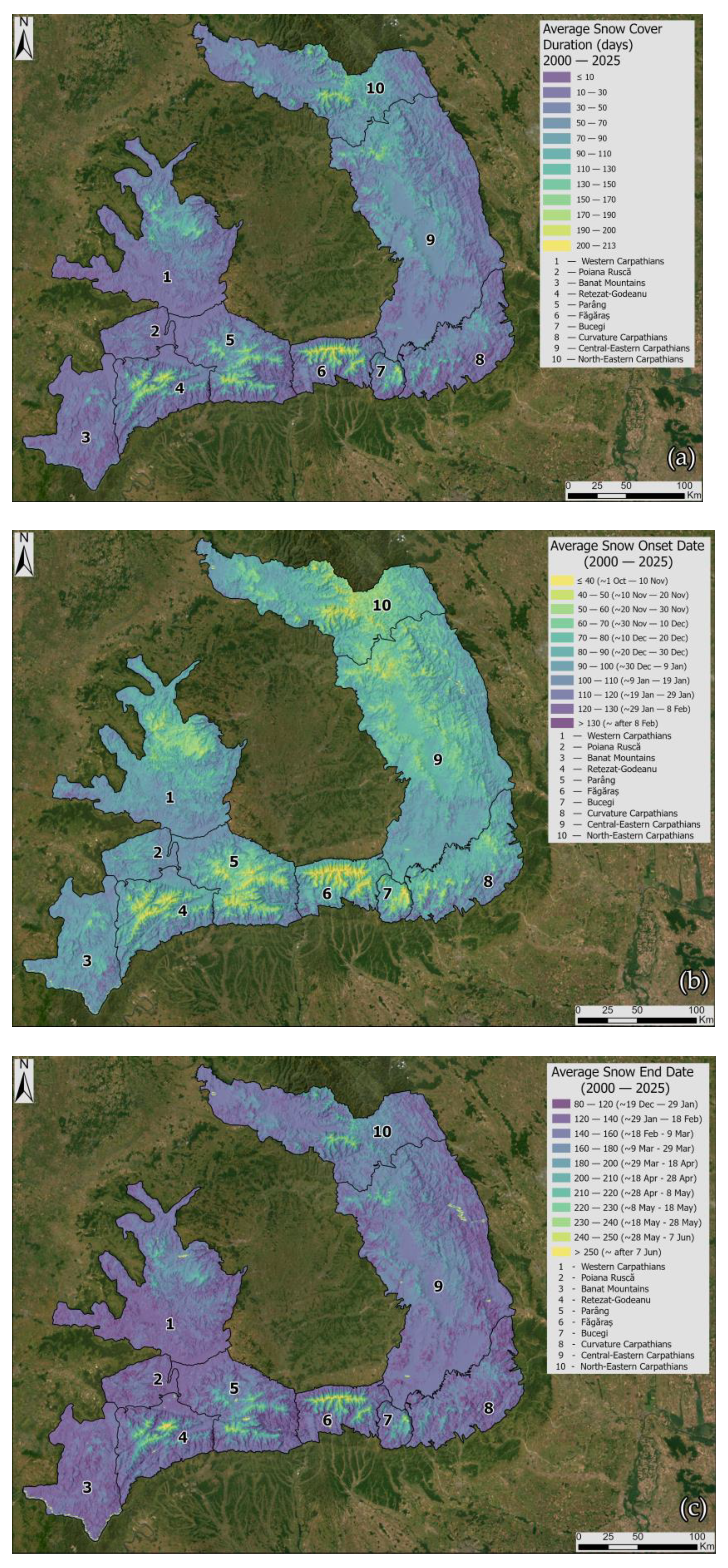

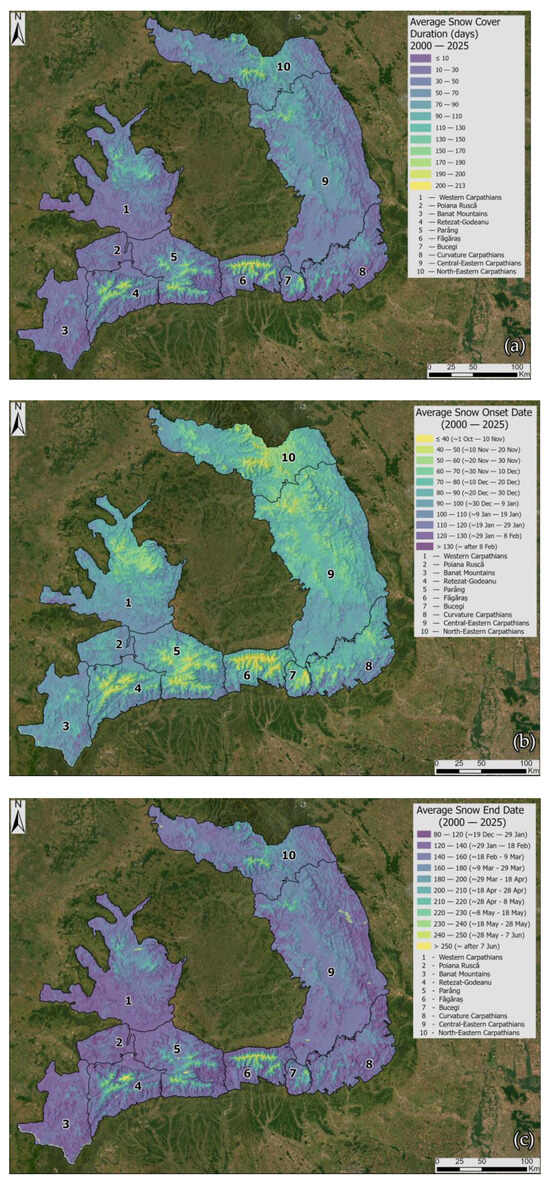

Figure 3.

(a) Average snow cover days map (SCD); (b) average snow onset date map (SOD); (c) average snow end date map (SED). The whole period is summed up and averaged in these maps (2000–2025).

Across the Romanian Carpathians, SCD clearly increases with altitude over the 2000–2025 period. At elevations below 500 m, the mean SCD is 22 ± 11 days, rising to 38 ± 20 days between 500 and 1000 m. In the 1000–1500 m class, the multiannual mean reaches ≈62 ± 31 days, increasing further to ≈129 ± 35 days between 1500 and 2000 m. Above 2000 m, SCD stabilizes at 183 ± 14 days, with local maxima around ≈197 ± 12 days in the highest mountain sectors.

The SOD, shown in Figure 3b, exhibits a clear altitudinal progression. At elevations below 500 m, persistent snow cover typically forms around day 97 ± 8 of the hydrological year (late December–early January). Between 500 and 1000 m, onset occurs earlier, at approximately 87 ± 11 days, advancing to ≈73 ± 13 days in the 1000–1500 m band. In the 1500–2000 m elevation class, SOD occurs around day 54 ± 8, while above 2000 m snow cover establishes near day 40 ± 6. The highest ridges (>2400 m) experience the earliest onset, at approximately day 34 ± 5, corresponding to late October–early November.

The SED, shown in Figure 3c, shifts progressively later with increasing elevation. Below 500 m, snow disappears around day 137 ± 8 (mid-February), while in the 500–1000 m band melt-out occurs at ≈146 ± 13 days. Between 1000 and 1500 m, SED is recorded around 160 ± 19 days, increasing to ≈202 ± 20 days in the 1500–2000 m interval (mid-April). Above 2000 m, SED reaches 236 ± 10 days (late May), with the highest peaks reaching ≈248 ± 9 days, corresponding to early June.

Beyond the elevation-based patterns, multiannual snow metrics also vary across the major mountain groups of the Romanian Carpathians. Table 2 summarizes the mean SCD, SOD, and SED values for each group. The lowest multiannual SCD values are recorded in the low-elevation Poiana Ruscă (22.2 ± 12.8 days) and Banat Mountains (22.3 ± 12.6 days), followed by the Western Carpathians (37.2 ± 28.1 days). Higher-elevation ranges exhibit substantially longer snow persistence, with the Făgăraș Mountains reaching 67.5 ± 58.9 days, the North-Eastern Carpathians 65.5 ± 32.7 days, and the Bucegi Mountains 60.7 ± 46.3 days. Intermediate SCD values characterize ranges such as Retezat–Godeanu (53.6 ± 46.3 days), Parâng (51.9 ± 44.3 days), the Central-Eastern Carpathians (53 ± 25.1 days), and the Curvature Carpathians (36.3 ± 25.6 days).

Table 2.

Multiannual mean values of SCD, SOD, and SED for the Romanian Carpathian mountain groups (2000–2025), reported together with their mean elevation.

Snow onset dates also vary among groups. The latest SOD values are observed in the Banat Mountains (96.5 ± 9 days) and Poiana Ruscă (95.3 ± 9.1 days), followed by the Western Carpathians (88.3 ± 14.2 days). Earlier onsets occur in the Făgăraș Mountains (74.4 ± 21.2 days), the North-Eastern Carpathians (74.5 ± 13.8 days), and Parâng (82 ± 18.9 days), while intermediate values are found in Retezat–Godeanu (84.1 ± 18.3 days), Bucegi (76.7 ± 19.8 days), and the Central-Eastern Carpathians (79.1 ± 11.7 days).

Similarly, SED varies among the Carpathian groups, ranging from earlier melt-out in Poiana Ruscă (136 ± 11.9 days) and the Banat Mountains (137 ± 9.8 days) to later melt in the Făgăraș (164.7 ± 36.7 days), Bucegi (163.4 ± 27.9 days), and North-Eastern Carpathians (161.3 ± 19.7 days). Intermediate SED values are observed in Retezat–Godeanu (157.3 ± 28.8 days), Parâng (155.8 ± 27.5 days), and the Central-Eastern Carpathians (153.3 ± 16.4 days), while the Western and Curvature Carpathians record melt around days 145–146.

3.2. Interannual Variability of Snow Phenology and Its Trend

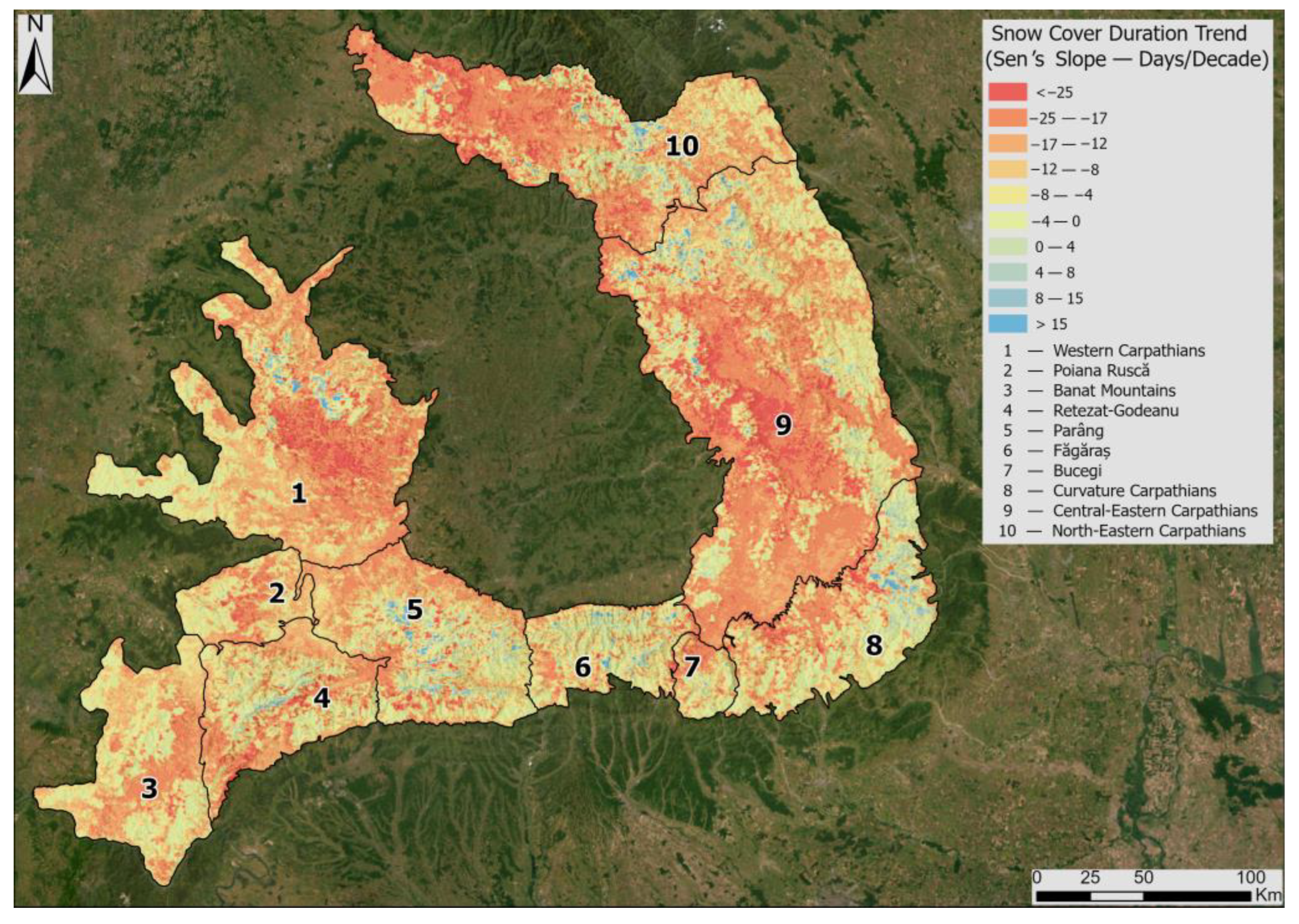

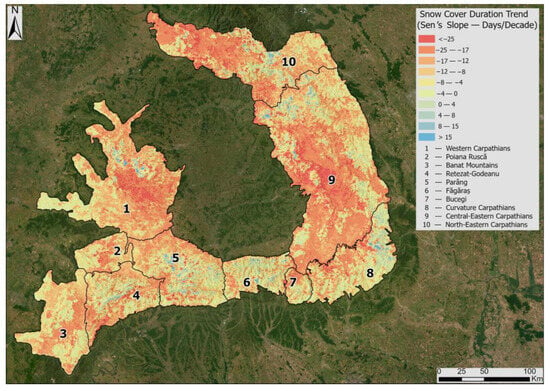

Analysis of multiannual SCD trend for 2000–2025, estimated using the Theil–Sen estimator (Figure 4), reveals a predominantly negative evolution across the Romanian Carpathians. The strongest declines, ranging from approximately −17 to −25 days per decade, are concentrated in the low- and mid-elevation sectors of the Western and Eastern Carpathians, where reductions in average snow persistence form spatially continuous zones. Moderately negative trends (−8 to −12 days per decade) extend throughout much of the areas situated around ~1000 m, while values between −4 and −8 days per decade dominate most areas below ~1500 m.

Figure 4.

Multiannual trend of snow cover duration (2000–2025), expressed in days per decade and estimated using Sen’s slope.

In higher mountain areas—including the highest mountain ranges of the Southern Carpathians (Retezat–Godeanu, Parâng, Făgăraș and Bucegi) and northern Eastern Carpathians—the decline in SCD is weaker, generally within the −3 to −4 days per decade range. Localized clusters of near-zero or slightly positive trends (+4 to +8 days per decade) occur on isolated ridges or plateaus exceeding 1800–2000 m, indicating areas where SCD has remained relatively stable over the study period.

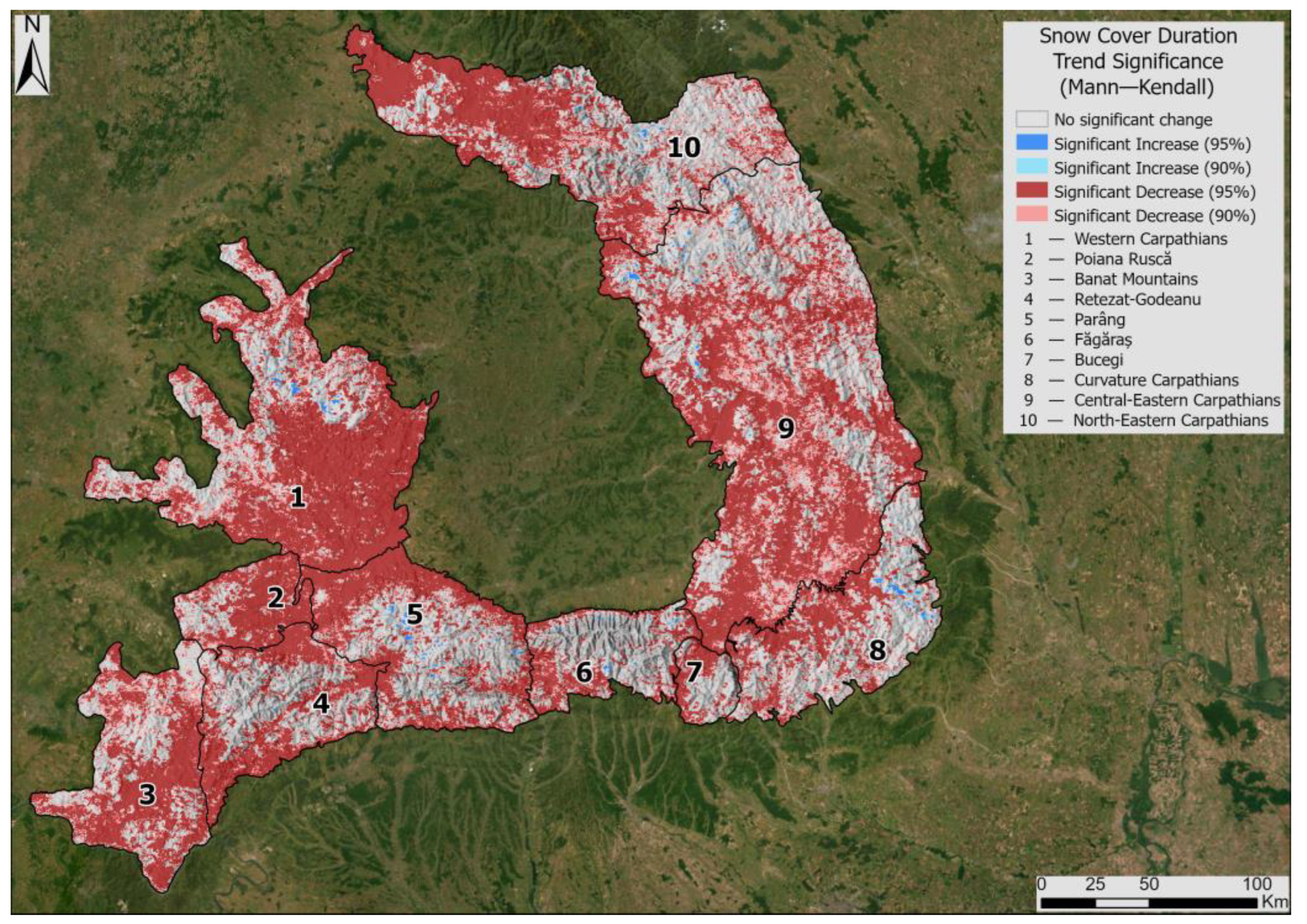

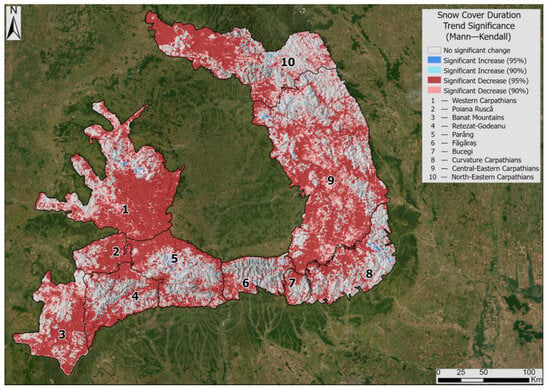

The Mann–Kendall test (Figure 5) indicates that statistically significant decreases (p < 0.05) prevail across large parts of the lowland and intramontane areas of the Western and Eastern Carpathians, coinciding with regions of the most pronounced negative slopes. By contrast, high-elevation areas are largely characterized by non-significant trends, suggesting limited systematic changes in SCD above ~1500–1800 m. Significant positive trends are uncommon and confined to small, spatially isolated high-altitude patches.

Figure 5.

Statistical significance (Mann–Kendall test) of the multiannual snow cover duration trend (2000–2025).

Overall, the spatial pattern of Sen’s slope estimates and their statistical significance points to a pervasive shortening of snow cover duration at low and mid elevations, in contrast to the relative stability observed at higher altitudes and the occurrence of only sporadic positive trends limited to ridge-top areas.

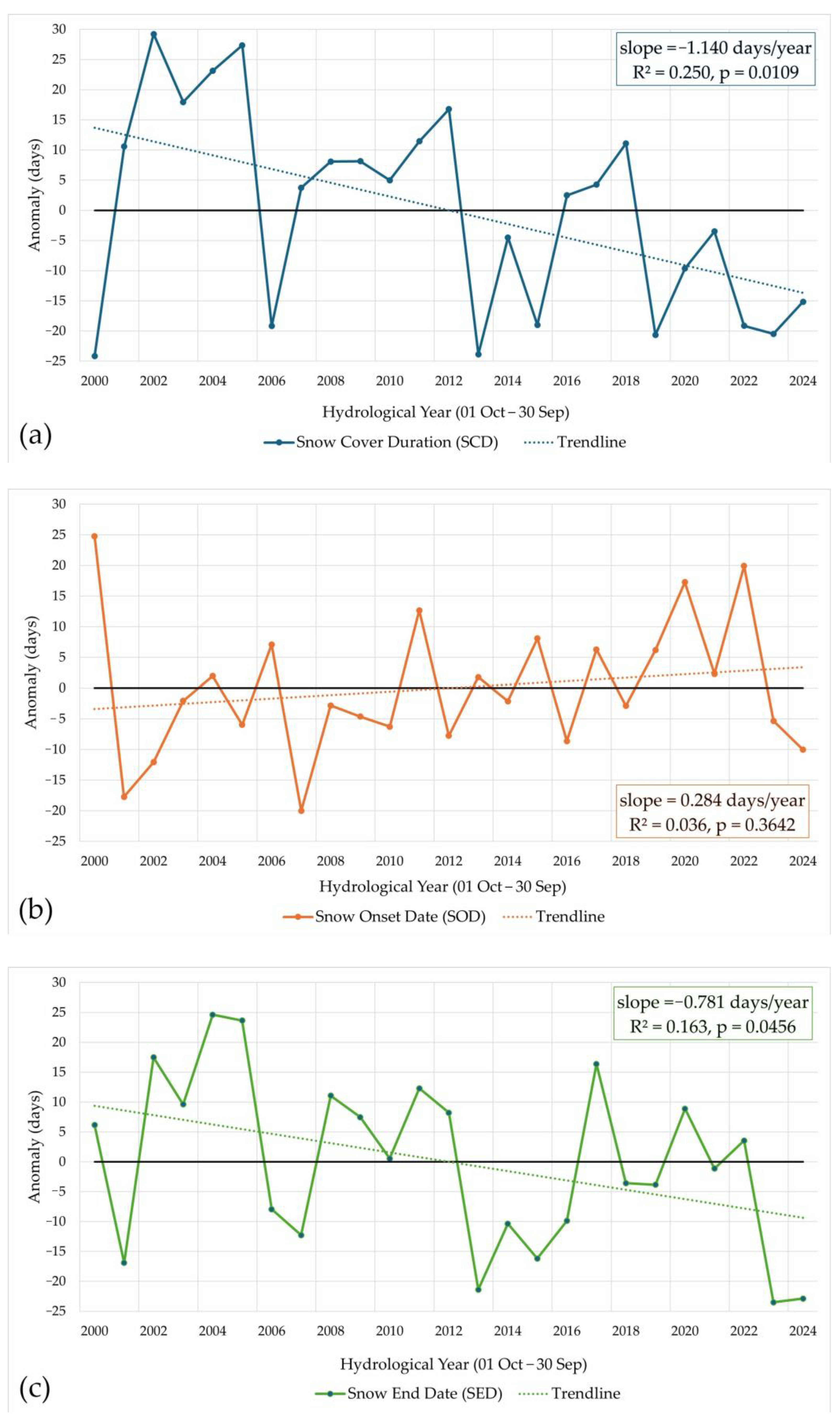

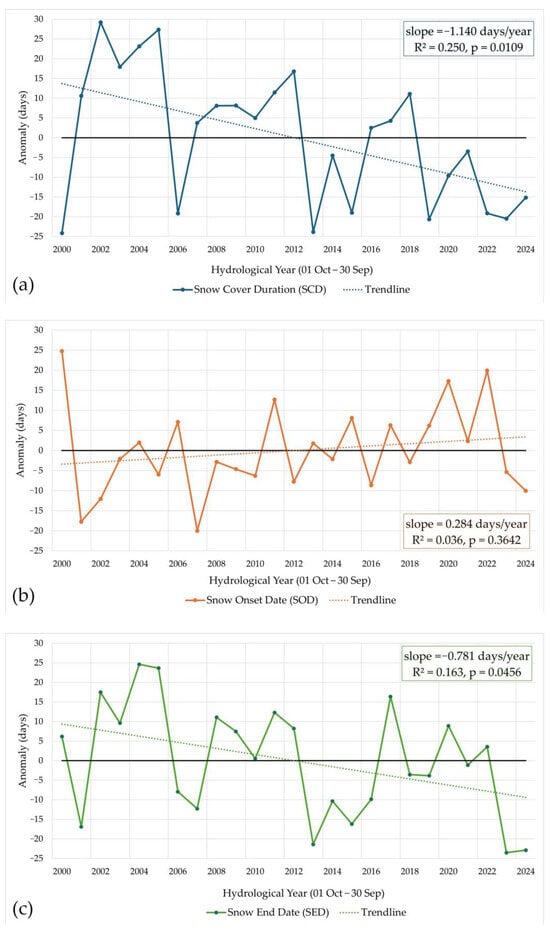

Interannual SCD anomalies for 2000–2025 across the entire mountain range (Figure 6a) reveal pronounced year-to-year variability throughout the Romanian Carpathians. The linear trend indicates a statistically significant decrease of −1.14 days per year (≈−11 days per decade; R2 = 0.25, p = 0.0109). The early part of the record (2000–2010) is dominated by predominantly positive anomalies, peaking during 2002–2005 when SCD exceeded the multiannual mean by approximately 20 to 30 days. After 2010, anomalies shift to largely negative values, frequently reaching −10 to −20 days, in agreement with the widespread negative Theil–Sen trends observed spatially. Overall, these results point to a persistent shortening of SCD over the study period.

Figure 6.

Interannual anomalies relative to the multiannual mean and associated linear trends for the snow metrics SCD (a), SOD (b), and SED (c) across the Romanian Carpathians during 2000–2025. The solid black horizontal line marks the multiannual mean of each metric, serving as the zero-anomaly reference.

SOD anomalies (Figure 6b) exhibit pronounced interannual variability, alternating between early- and late-onset years. The linear trend suggests a slight, statistically non-significant delay of +0.28 days per year (R2 = 0.036, p = 0.364). Positive anomalies, reflecting earlier onset, occur in 2000, 2010, 2020, and 2022, whereas negative anomalies—indicating delayed onset—characterize periods such as 2001–2002, 2007–2008, and 2018–2019. Overall, the fluctuation amplitude, generally within ±10 days, highlights irregular snow onset timing without evidence of a systematic shift in the start of the snow season.

Interannual SED variability (Figure 6c) shows a clearer downward tendency, with a statistically significant decrease of −0.78 days per year (≈−8 days per decade; R2 = 0.163, p = 0.0456), reflecting progressively earlier snow disappearance. Positive anomalies characterize the early years of the record (2002–2005), when melt occurred +15 to +25 days later than average, whereas negative anomalies prevail after 2010, reaching −10 to −20 days in 2013, 2016, 2019, and 2024. These sustained negative deviations correspond with the observed SCD decline, confirming a progressive advancement of the snow season’s end across the Carpathians.

Overall, the interannual patterns of SCD, SOD, and SED across the entire study area indicate a clear shortening of the snow season, driven mainly by earlier melt and reduced snowpack persistence, while snow onset remains highly variable without exhibiting a significant long-term trend.

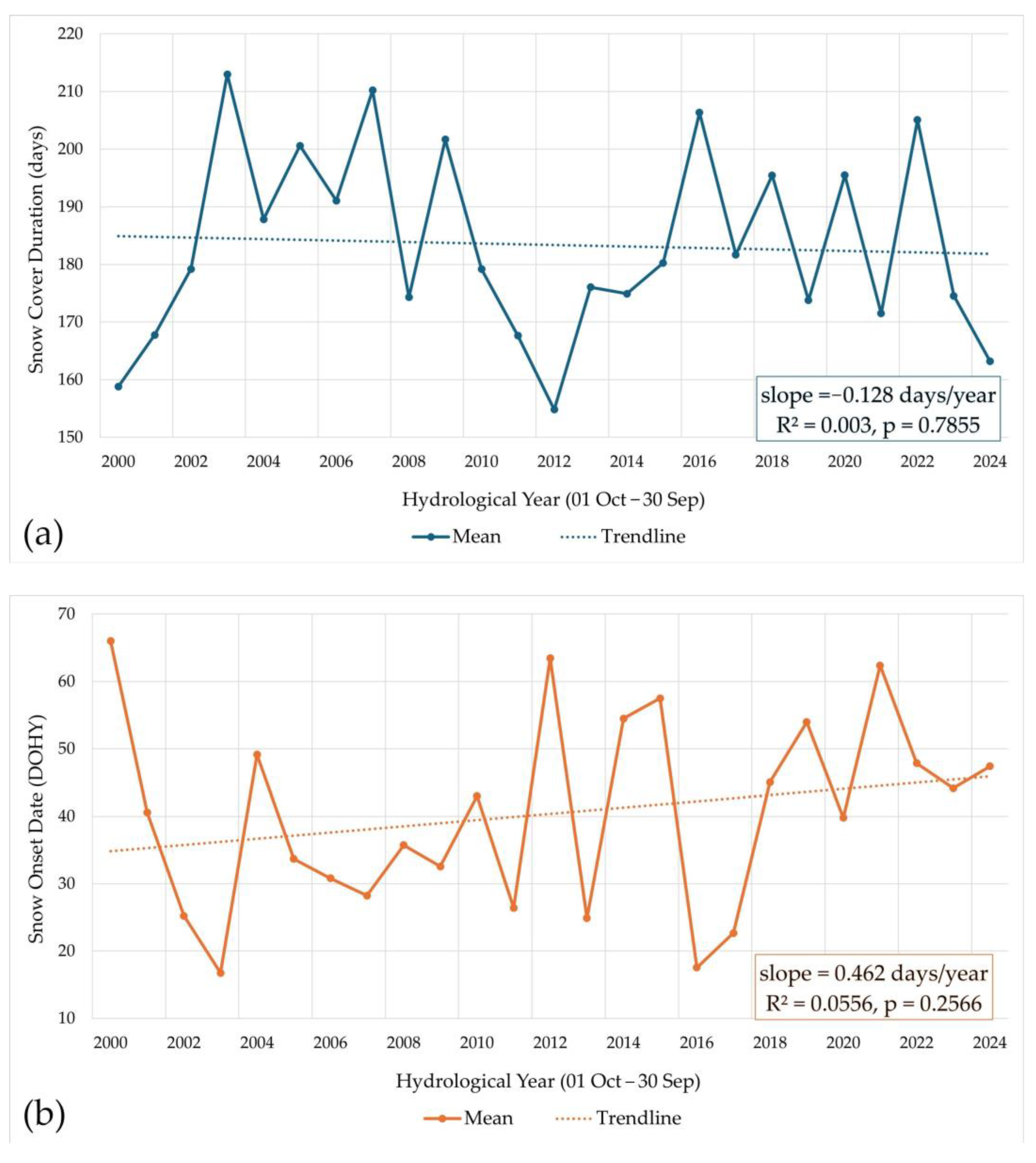

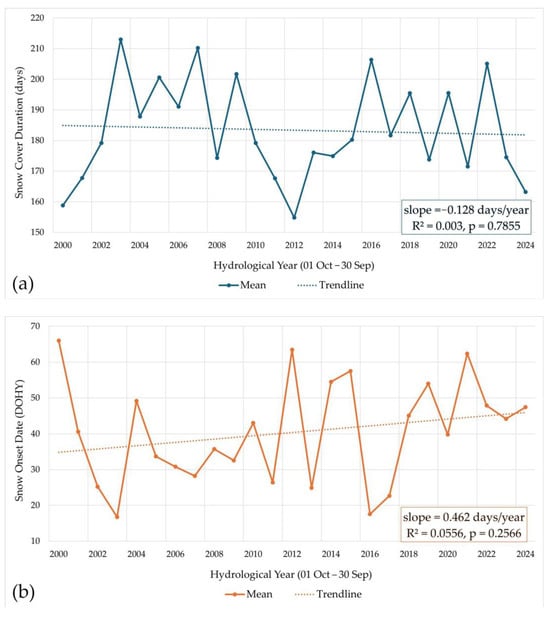

The interannual evolution of snow metrics at elevations ≥ 2000 m (Figure 7) reveals a considerably more stable nival regime than observed across the Carpathians as a whole, characterized by lower year-to-year variability and statistically non-significant long-term trends. For SCD, annual mean values fluctuate mainly between 160 and 210 days, with the linear trend indicating only a minor decrease (–0.13 days yr−1; R2 = 0.003; p = 0.785). This negligible change highlights the persistence of long snow seasons in the alpine zone over the past 25 years.

Figure 7.

Interannual variability and associated linear trends of the absolute yearly means of snow metrics at elevations ≥ 2000 m: SCD expressed in days (a); SOD (b) and SED (c) expressed as day of the hydrological year (DOY).

SOD exhibits similarly limited variability, with most years occurring between day 20 and day 65 of the hydrological year (late October to early November). The linear trend suggests a slight shift toward later onset (+0.46 days yr−1; R2 = 0.056; p = 0.256), though this change is not statistically significant.

For SED, interannual values typically range from day 220 to day 270, indicating that snowpacks often persist into late May or June. The fitted trendline suggests a slight delay in melt-out (+0.32 days yr−1; R2 = 0.028; p = 0.422), which is not statistically meaningful.

Overall, the lack of significant trends across all three metrics underscores the temporal stability and climatic resilience of high-elevation snow conditions in the Romanian Carpathians. In contrast to the pronounced reductions observed at lower altitudes, the alpine zone has maintained a relatively consistent snow season in terms of duration, onset, and melt-out of throughout the 2000–2025 period.

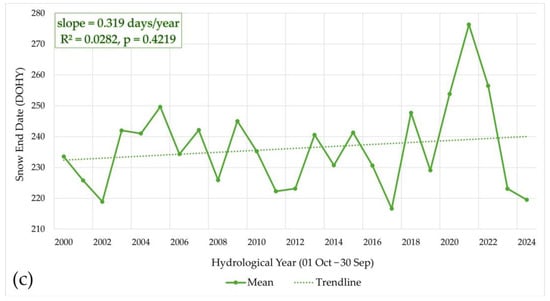

3.3. Topographic and Regional Controls on Snow Metrics

To quantify how snow persistence varies with elevation across the Romanian Carpathians, the full SCD dataset was stratified using a fine-resolution hypsometric binning approach. The elevation range was divided into contiguous 5 m intervals, and all MODIS grid cells whose elevations fell within each interval were aggregated. For each 5 m band, the distribution of SCD values for the 2000–2025 period was summarized using the 1st, 5th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, 95th, and 99th percentiles (Figure 8). This approach provides a consistent and statistically robust representation of both the central tendency of snow duration (median) and the magnitude of interannual variability (lower and upper percentiles) along the hypsometric gradient.

Figure 8.

Quantile statistics of SCD for the 2000–2025 period, computed for each 5 m elevation band across the Romanian Carpathians.

At elevations below 800 m, snow cover duration remains short, typically under 50 days, and the wide separation between percentile curves reflects substantial year-to-year variability driven by the sensitivity of low-altitude snow to temperature fluctuations. Between roughly 1000 and 1500 m, the widening inter-percentile range highlights increasingly pronounced contrasts between low-snow and high-snow years, indicative of enhanced climatic variability in this transitional elevation zone. Above ~1500 m, the median SCD shows a marked upward inflection, signaling the onset of a more persistent seasonal snow regime. Beyond 2000 m, the percentile curves converge, reflecting considerably reduced interannual variability and consistently prolonged snow durations (>180–200 days), characteristic of the stable thermal conditions in high-altitude environments.

Overall, the 5 m elevation-band analysis reveals a nonlinear relationship between elevation and SCD, characterized by a rapid increase in snow persistence with altitude and a pronounced reduction in interannual variability at higher elevations. This fine-scale stratification highlights the dominant role of elevation in controlling the spatial and temporal patterns of snow cover across the Romanian Carpathians.

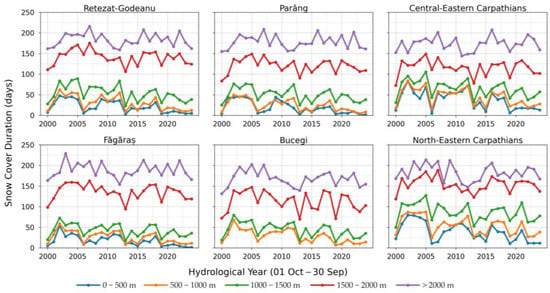

Regarding regional variations in snow cover duration, Figure 9 presents SCD time series for 500 m elevation intervals across the highest mountain groups of the Romanian Carpathians. The Southern Carpathians (Retezat–Godeanu, Parâng, Făgăraș, Bucegi) show highly consistent SCD trajectories across corresponding elevation bands, whereas the North-Eastern and Central-Eastern Carpathians systematically display higher values at equivalent altitudes. These differences are most pronounced in the 1000–1500 m interval and, to a lesser but still noticeable extent, in the 1500–2000 m band.

Figure 9.

SCD time series for the six main high-mountain groups of the Romanian Carpathians, aggregated into 500 m elevation bands (2000–2025). The plots highlight marked contrasts between the Southern and Eastern Carpathians.

At 1000–1500 m, the Southern Carpathian groups exhibit tightly clustered mean SCD values—54.23 ± 19.38 days in Retezat–Godeanu, 50.17 ± 16.30 days in Parâng, 43.12 ± 14.71 days in Făgăraș, and 44.35 ± 17.49 days in Bucegi. In comparison, the North-Eastern Carpathians reach 87.05 ± 20.60 days and the Central-Eastern Carpathians 65.44 ± 19.94 days, reflecting substantially longer and more persistent snow cover at mid elevations in the eastern sector. A similar pattern is evident between 1500 and 2000 m, where mean SCD values are 140.98 ± 17.57 days in Retezat–Godeanu, 120.46 ± 17.02 days in Parâng, 136.12 ± 18.41 days in Făgăraș, 113.62 ± 24.13 days in Bucegi, and 116.13 ± 18.22 days in the Central-Eastern Carpathians, while the North-Eastern Carpathians maintain relatively higher values at 153.63 ± 17.48 days.

Above 2000 m, SCD generally exceeds 170–200 days across all mountain groups, although interregional differences remain noticeable. The Southern Carpathians show comparable values—183.27 ± 15.84 days in Retezat–Godeanu, 177.96 ± 16.09 days in Parâng, and 188.44 ± 17.93 days in Făgăraș—while the North-Eastern Carpathians reach 182.75 ± 19.36 days and the Central-Eastern Carpathians 173.06 ± 16.72 days. Across all elevation bands, the Southern Carpathians exhibit internally coherent behavior, whereas the Eastern Carpathians consistently maintain longer snow cover durations, particularly at mid-to-high elevations. These contrasts are clearly reflected in the temporal evolution shown in Figure 9, highlighting the pronounced regional structuring of SCD regimes within the Romanian Carpathians.

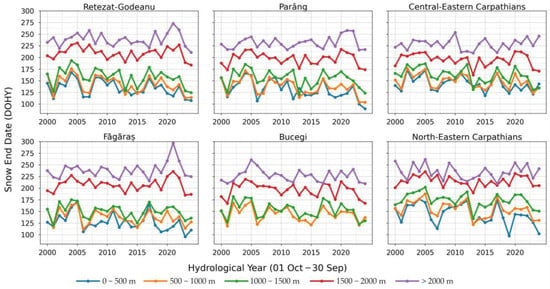

SED patterns largely reflect regional contrasts observed in SCD, with pronounced differences in melt timing at mid–to–high elevations. At 1000–1500 m, the Southern Carpathian groups show relatively similar mean snow end dates, with multiannual averages of 158.31 ± 18.78 days for Retezat–Godeanu, 155.10 ± 17.46 days for Parâng, 149.99 ± 14.87 days for Făgăraș, and 152.94 ± 17.27 days for Bucegi. In comparison, the North-Eastern Carpathians reached 174.01 ± 15.45 days and the Central-Eastern Carpathians 161.83 ± 16.69 days, indicating later melt for the eastern sector at the same elevation.

The contrast becomes even more pronounced in the 1500–2000 m band. In the Southern Carpathians, mean SED ranges from 209.18 ± 12.80 days in Retezat–Godeanu and 197.07 ± 13.27 days in Parâng to 207.23 ± 13.40 days in Făgăraș and 196.09 ± 14.92 days in Bucegi. In comparison, the North-Eastern Carpathians exhibit distinctly later snow disappearance at 215.05 ± 11.43 days, while the Central-Eastern Carpathians record 195.11 ± 13.51 days. These patterns, illustrated in Figure 10, indicate that at equivalent elevation thresholds, snow generally persists longer into the hydrological year in the Eastern Carpathians, particularly in the 1000–1500 m and 1500–2000 m bands.

Figure 10.

SED time series for the six main high-mountain groups of the Romanian Carpathians, aggregated into 500 m elevation bands (2000–2025).

To further examine terrain controls on snow distribution, we quantified aspect-related differences in SCD across 500 m elevation classes (Table 3). North-facing slopes consistently exhibit the longest snow cover duration, exceeding south-facing slopes by 10–12 days at most elevation bands. This difference amounts to 11.1 days at 1000–1500 m (N = 132.21 ± 18.53 days, S = 121.07 ± 18.44 days) and approximately 9.3 days above 2000 m (N = 188.75 ± 16.05 days, S = 179.48 ± 16.41 days). At lower elevations, the gap narrows but remains evident, with north-facing slopes exceeding south-facing ones by ~4.5 days below 500 m and ~10.7 days between 500 and 1000 m.

Table 3.

Aspect control on SCD in the Romanian Carpathians. Values represent multiannual mean SCD (±sd) and long-term trends (days/decade) for each aspect (N, S, W, E) across 500 m elevation classes (2000–2025).

East- and west-facing slopes exhibit intermediate snow cover durations between those of north- and south-facing slopes. At mid elevations, north-facing slopes retain 5–7 days more snow than west-facing slopes (6.2 days at 1000–1500 m—W = 126.01 ± 17.74 days), and 4–6 days more than east-facing slopes (5.1 days at 1000–1500 m—E = 127.12 ± 18.06 days). Above 2000 m, inter-aspect differences decrease but remain measurable, with north-facing slopes exceeding east- and west-facing ones by around 6–7 days.

Long-term SCD trends are negative for all aspects across most elevation bands. The strongest declines occur below 1000 m (−11.47 to −13.19 days/decade), whereas above 2000 m, trends weaken substantially (between −0.82 and −1.81 days/decade). Across all elevation classes, north-facing slopes maintain the highest SCD, followed by west and east orientations, with south-facing slopes consistently exhibiting the shortest snow cover duration.

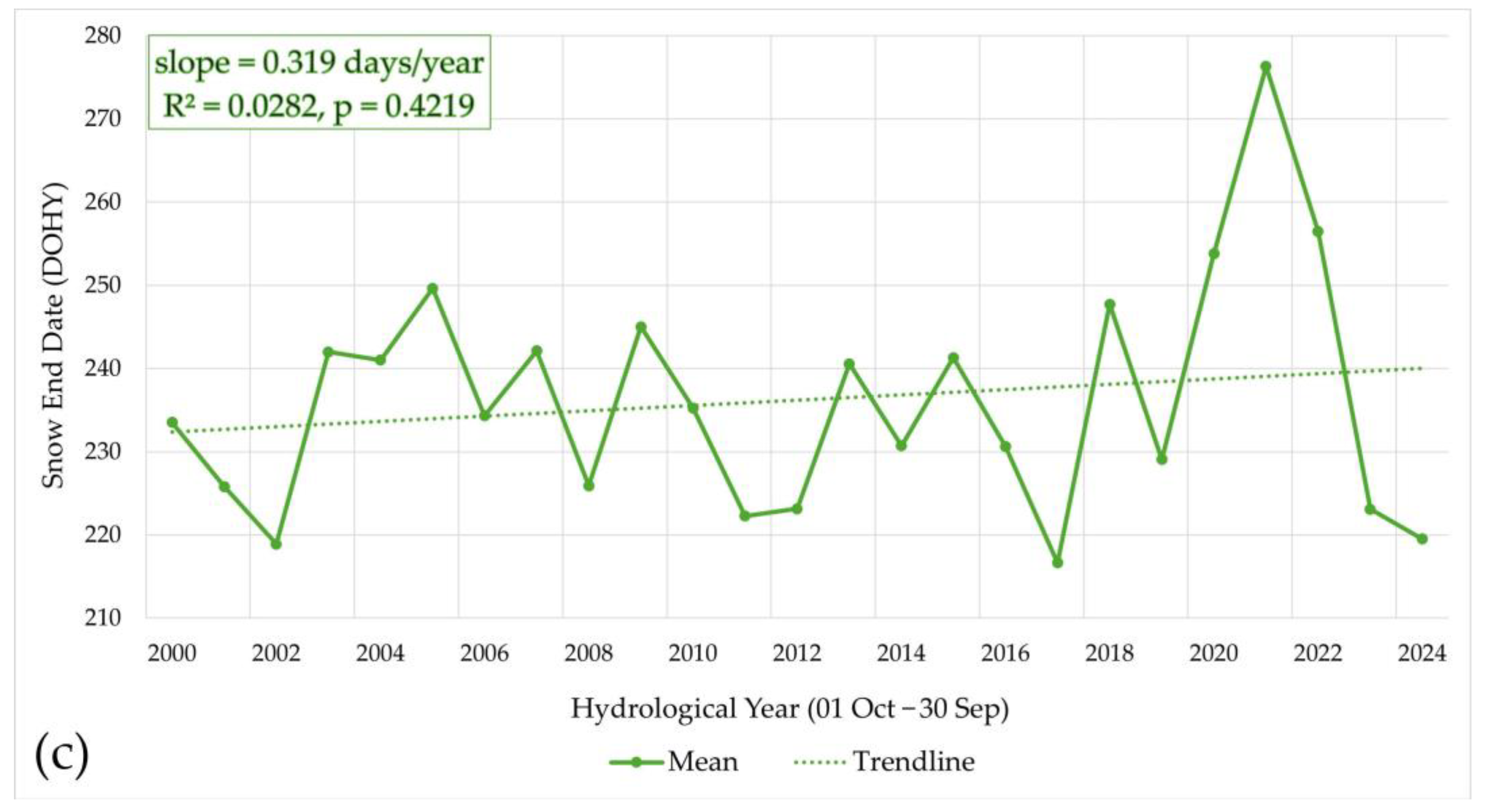

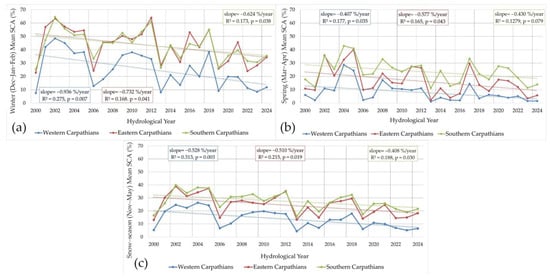

Mean snow-covered area exhibits declining trends across 2000–2025 in all three Carpathian units and across each seasonal window (Figure 11). In winter (December–February), SCA decreases at −0.936% yr−1 in the Western Carpathians (p = 0.007), −0.732% yr−1 in the Eastern (p = 0.041), and −0.624% yr−1 in the Southern Carpathians (p = 0.038). Winter mean SCA is ~40–50% in the early 2000s (peaking above ~60% in some years for Eastern/Southern) and declined to roughly ~10–20% in the Western and ~30–35% in the Eastern/Southern Carpathians in the most recent years (≈2022–2024).

Figure 11.

Spatiotemporal variability and trends in snow-covered area (SCA) across the three main units of the Romanian Carpathians (2000–2025). Interannual time series of hydrological-year mean SCA (%) for the Western, Eastern, and Southern Carpathians aggregated for (a) winter (December–February), (b) spring (March–April), and (c) the full snow season (November–May). Dotted lines show fitted linear trends; inset boxes report the corresponding slope (% yr−1), coefficient of determination (R2), and p-value.

In spring (March–April), SCA also exhibits declining trends (Western: −0.407% yr−1, p = 0.035; Eastern: −0.577% yr−1, p = 0.043; Southern: −0.430% yr−1, p = 0.079), with early-2000s values commonly around ~10–25% (occasionally higher in individual years) dropping to about ~2–6% in the Western/Eastern and ~10–15% in the Southern Carpathians by ≈2022–2024.

For the full snow-season window (November–May), declining trends are evident across all Carpathian units (Western: −0.528% yr−1, p = 0.003; Eastern: −0.510% yr−1, p = 0.019; Southern: −0.408% yr−1, p = 0.030). Mean SCA during November–May was approximately 20–30% in the early 2000s decreasing to roughly 5–10% in the Western, 15–20% in the Eastern, and 20–25% in the Southern Carpathians by ≈2022–2024.

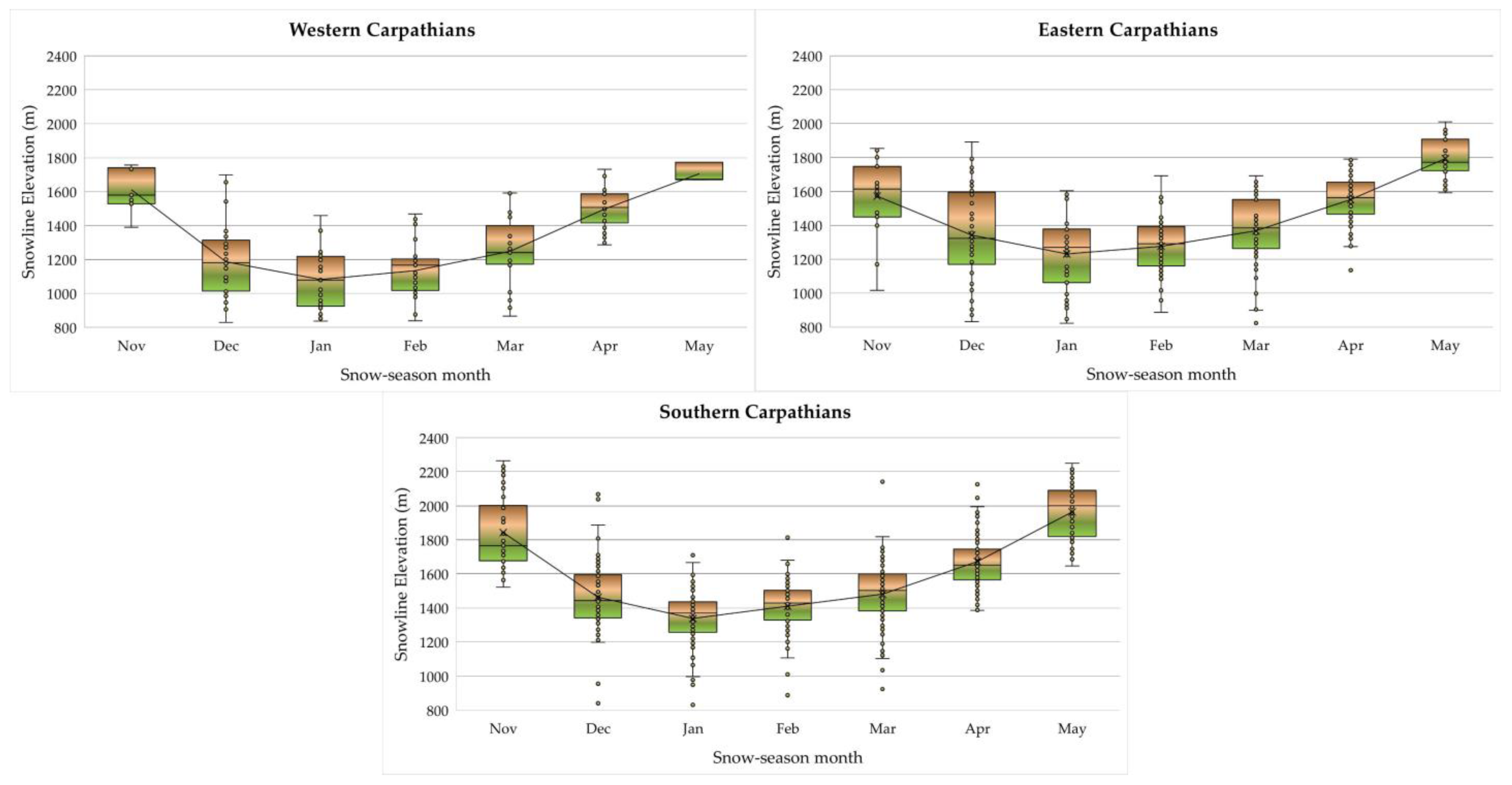

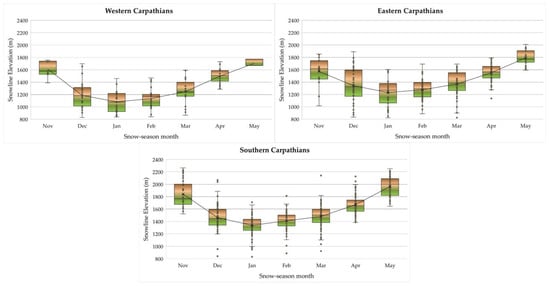

Snowline elevation (SLE) exhibits a pronounced seasonal cycle across all three Carpathian units, with substantial interannual dispersion that varies by month and region (Figure 12). Variability is lowest during the shoulder months when the snowline remains consistently high (particularly in November and May), as reflected by narrow interquartile ranges (IQRs) and shorter whiskers. In contrast, dispersion increases markedly during the core winter and early spring months (December–March), as box widths and whisker lengths expand and outliers become more frequent, indicating strong year-to-year shifts in the elevation of persistent snow cover.

Figure 12.

Monthly variability of snowline elevation (SLE) across the three main units of the Romanian Carpathians (2000–2025). Box-and-whisker plots show the distribution of SLE (m) for snow-season months (November–May) aggregated by hydrological year for the Western, Eastern, and Southern Carpathians. Color shading of the plots reflects the SLE elevation gradient (lower–to–higher elevations).

Among the Carpathian units, the Western Carpathians exhibit the greatest relative spread during mid-winter (December–February), with wide IQRs and numerous low-elevation outliers, reflecting the high sensitivity of snowline position to interannual variability in accumulation and melt conditions at these elevations. The Eastern Carpathians also display elevated dispersion in December–March, with frequent low outliers and extended lower whiskers, indicating recurrent winters in which snowline elevations fall substantially below the monthly median. The Southern Carpathians maintain systematically higher median SLE values through the season, but still display pronounced winter and early-spring variability (December–March), including occasional extreme outliers, demonstrating that even the highest Carpathian sector experiences substantial interannual fluctuations in snowline elevation. Overall, Figure 12 shows that while the median SLE follows a consistent U-shaped seasonal trajectory, the spread (IQR and outliers) peaks during December–March, emphasizing that the timing and magnitude of winter snowline lowering and subsequent spring rise are highly variable between years and differ across the three major mountain units.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Snow Cover in the Romanian Carpathians and Its Environmental Implications

While the combination of MODIS snow products combined with Mann–Kendall/Theil–Sen trend analysis is well established, the key contribution of this work is the provision of a Carpathians-wide, spatially continuous 25-year baseline of snow-season persistence and timing derived from daily 500 m MODIS/Terra cloud-gap-filled observations. By translating pixel-level time series into a structured snow-regime framework—through consistent stratification by elevation, aspect and mountain units, complemented by diagnostics of snow-covered area and snowline elevation—this analysis captures within-belt heterogeneity and elevational transition zones that are challenging to resolve using sparse station networks or coarse regional summaries.

The MODIS CGF record (2000–2025) reveals a highly variable and progressively unstable snow cover regime across the Romanian Carpathians, with the strongest changes concentrated below 2000 m elevation. Pronounced interannual variability in snow cover duration and transition timing reflects frequent alternations between winters with sustained accumulation and seasons characterized by intermittent or short-lived snow cover. This instability reduces the persistence of the seasonal snow insulation layer and increases exposure of the ground surface to cold-season and spring temperature fluctuations, which is particularly significant in marginal periglacial environments where snow cover exerts a first-order control on ground thermal conditions and active-layer dynamics [49]. Consistent with this sensitivity, recent work using the nival offset parameter in the Southern Carpathians indicates that the insulating effect of snow on ground-surface temperature (GST) is comparatively low relative to high-latitude settings [50]. Because snow cover duration strongly affects permafrost persistence in marginal mountain regions [51], the earlier melt-out documented here implies an increased susceptibility to permafrost degradation in this vulnerable setting.

Clear altitudinal contrasts emerge from the results. Low- and mid-elevation belts exhibit marked reductions in snow persistence and earlier melt, whereas the highest massifs—particularly in the Southern Carpathians—maintain comparatively stable snow regimes commonly exceeding ~180–200 days per year. This divergence points to an increasing differentiation between alpine and forested mountain belts in snow–ground coupling. While delayed onset can locally promote deeper early-winter cooling, the consistent advance of snowmelt lengthens the snow-free period during spring and early summer, when radiative forcing is strong, thereby favoring active-layer warming and increasing the vulnerability of marginal periglacial landforms [52,53].

In addition, increased variability in snow accumulation and a tendency toward earlier and more rapid melt may affect avalanche conditions during transitional phases of the snow season. Under warming, climate-driven changes in snowpack temperature and wetness increasingly favor wet-snow processes and spring avalanche activity, particularly during periods of strong radiation or short-duration, high-intensity snowfall events [54,55].

A shorter snow season modifies near-surface energy balance and thermal conditions at high elevations, promoting an earlier start-of-season (SOS) and accelerated spring green-up. This pattern aligns with satellite-based evidence of advancing spring phenology reported for Carpathian forest types in the Western Carpathians and across the Carpathian arc [56]. In alpine environments, snowmelt timing is a key ecological control on snowbed systems, influencing plant phenology and growth and, under persistent shifts, potentially affecting community composition and the persistence of late-lying snow habitats. Multi-decadal dynamics observed at the forest–alpine ecotone and treeline [57], as well as remotely sensed alpine–subalpine–forest cover transitions in the Southern Carpathians, are broadly consistent with warming-driven vegetation adjustments in the region, although species-range responses are not quantified here [58,59].

A decline in snow cover duration generally reduces seasonal snow storage and advances melt-out, shifting the timing of the nival runoff toward earlier spring and increasing the relative contribution of winter and early-spring discharge. This promotes a more mixed nival–pluvial regime in snow-influenced catchments [7,60]. In Romania, hydroclimatic analyses report trends consistent with increased winter-skewed runoff under warming [61,62] alongside documented declines in snow cover duration and earlier melt timing, supporting the interpretation that the ~11 days decade−1 reduction in Carpathian SCD inferred here would favor earlier spring snowmelt contributions and higher winter/early-spring runoff fractions; nevertheless, peak-flow responses remain catchment- and event-dependent, particularly under rain-on-snow conditions [62,63].

4.2. Uncertainty Assessment and Validation

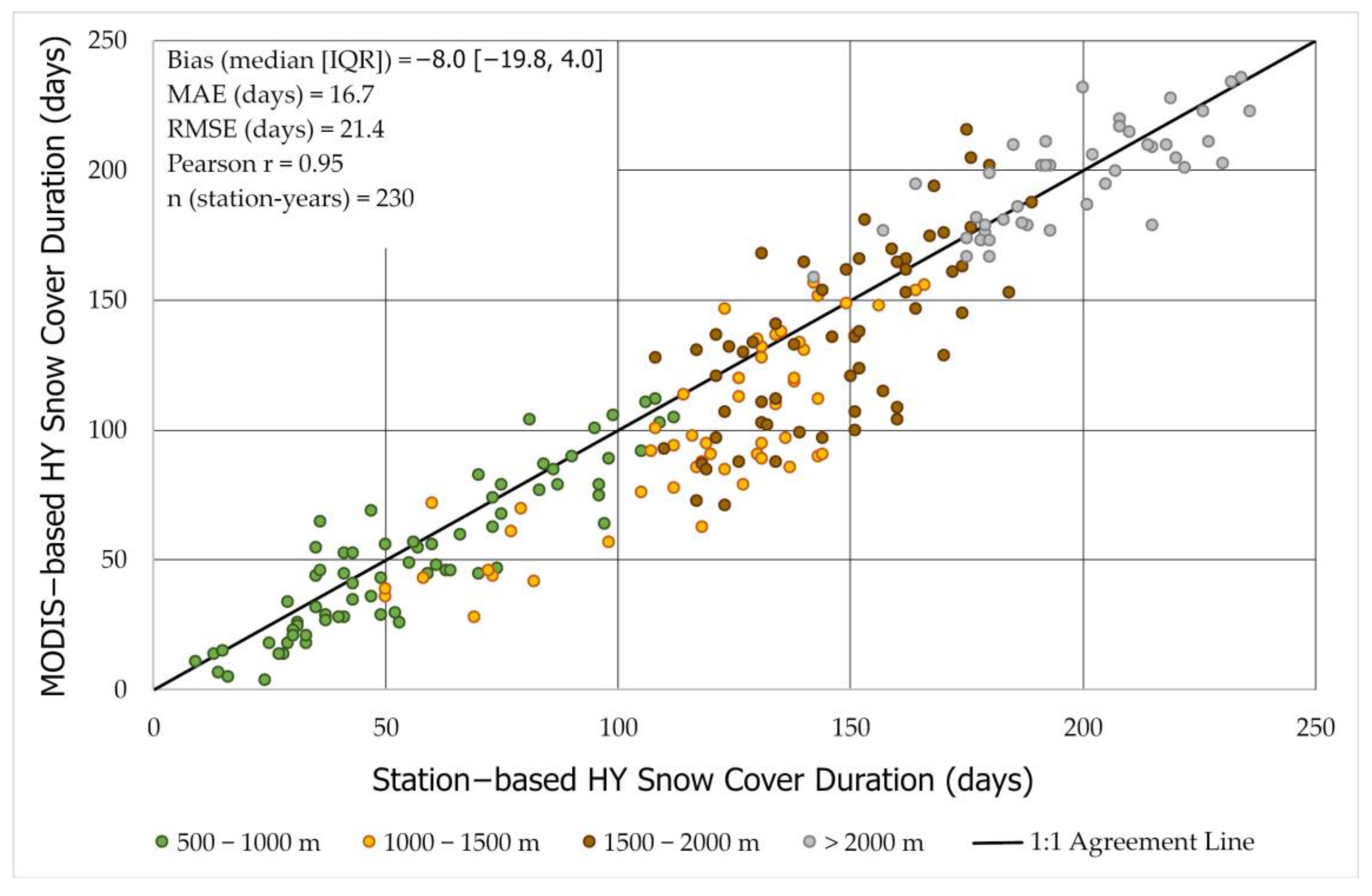

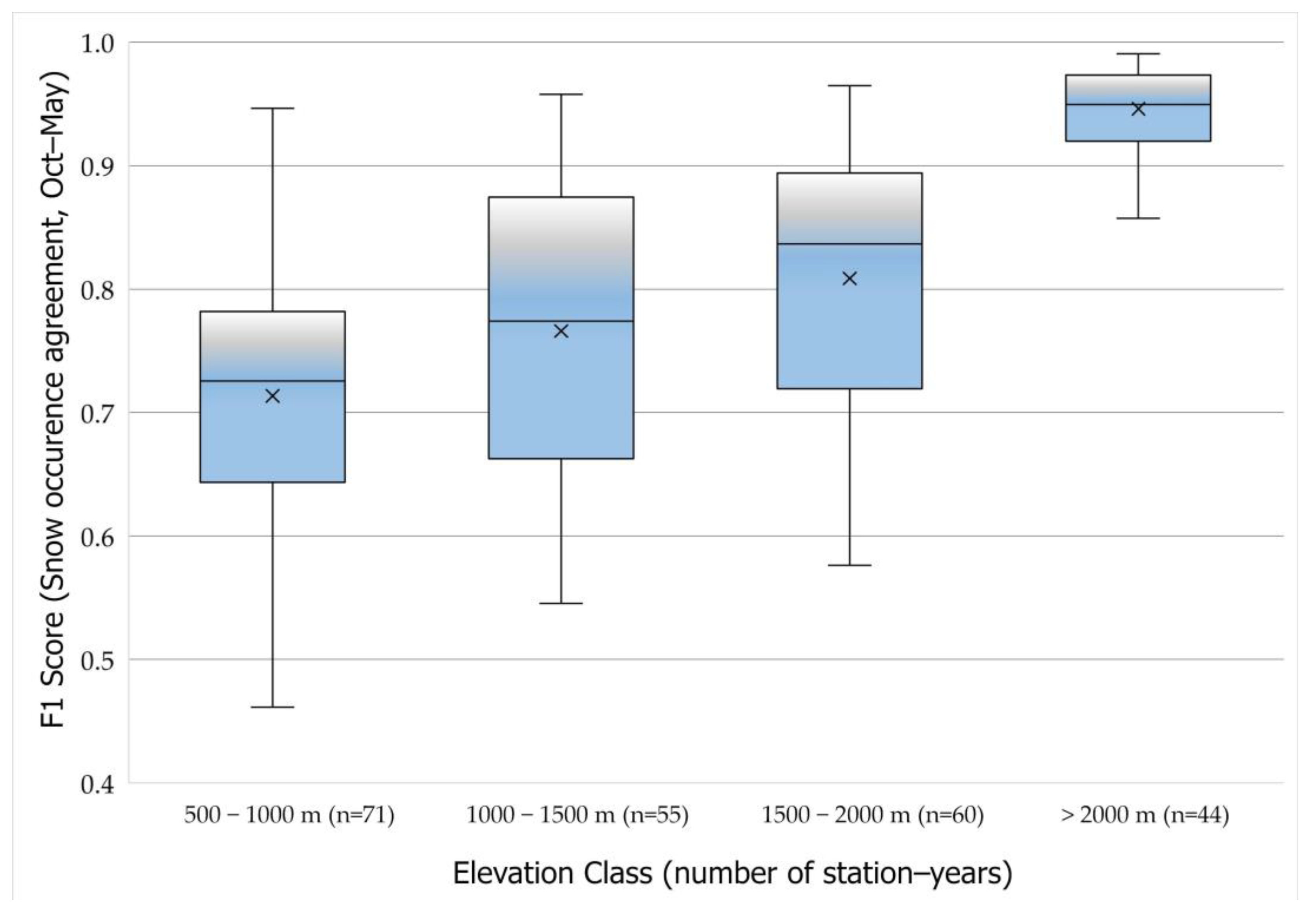

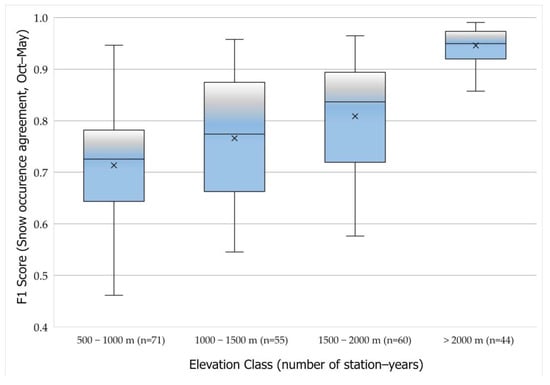

Overall, the MODIS/Terra CGF snow metrics show strong agreement with weather-station observations over the available validation period, demonstrating that the dataset provides a robust basis for Carpathian-scale snow-phenology analysis. For hydrological-year snow cover duration (SCD), the station–MODIS relationship is very strong (Pearson r = 0.95; MAE = 16.7 days; RMSE = 21.4 days), with a small median bias of −8.0 days (IQR: −19.8 to 4.0) and a modest tendency toward underestimation (Figure 13). Performance is particularly good at the elevation extremes: agreement is highest at 500–1000 m (r = 0.91; MAE = 10.7 days; bias = −7.0 days) and remains strong at >2000 m, where the bias is near-zero (−1.5 days) and MAE is low (11.7 days) (Table 4). Day-to-day snow occurrence agreement during October–May is also consistently high and improves with elevation, with median F1 score rising from ~0.73 (500–1000 m) to ~0.95 (>2000 m) (Figure 14). For phenology timing, SOD differences are small across all elevation classes (median bias ~3–5 days; MAE ~10–14 days), supporting the reliability of onset timing at the scale of this study. Uncertainty is larger for SED, with the highest MAE in the 1500–2000 m band (28.3 days), and overall correlations for SCD weaken somewhat at mid elevations (minimum r = 0.70 at 1500–2000 m) (Table 4).

Figure 13.

Agreement between MODIS/Terra MOD10A1F cloud-gap-filled (CGF) and station-based hydrological-year snow cover duration (SCD) for the Romanian Carpathians over the validation period July 2014–September 2025 (n = 230 station-years). Each point represents one station–year pair, colored by station elevation class (500–1000, 1000–1500, 1500–2000, and >2000 m a.s.l.; station metadata in Table S1).

Table 4.

Station-based accuracy assessment of MODIS Terra CGF snow metrics by elevation class (2014–2025). Statistics are computed across station-years (N). Bias is the median difference (MODIS—station) [IQR] in days (negative = MODIS underestimation). MAE is the mean absolute error in days. SOD/SED are reported as day-of-hydrological-year (DOHY; 1 October–30 September).

Figure 14.

Elevation dependence of daily snow-occurrence agreement between MODIS/Terra MOD10A1F CGF and station observations over the snow season (October–May) for the validation period July 2014–September 2025. Agreement is summarized by elevation class using the F1 score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) computed for each station–year, and displayed as box-and-whisker plots (median, interquartile range; whiskers represent 1.5 × IQR; “×” marks the mean). Sample sizes (n) indicate the number of station-years in each elevation class (station list in Table S1).

4.3. Climate–Snow Interactions

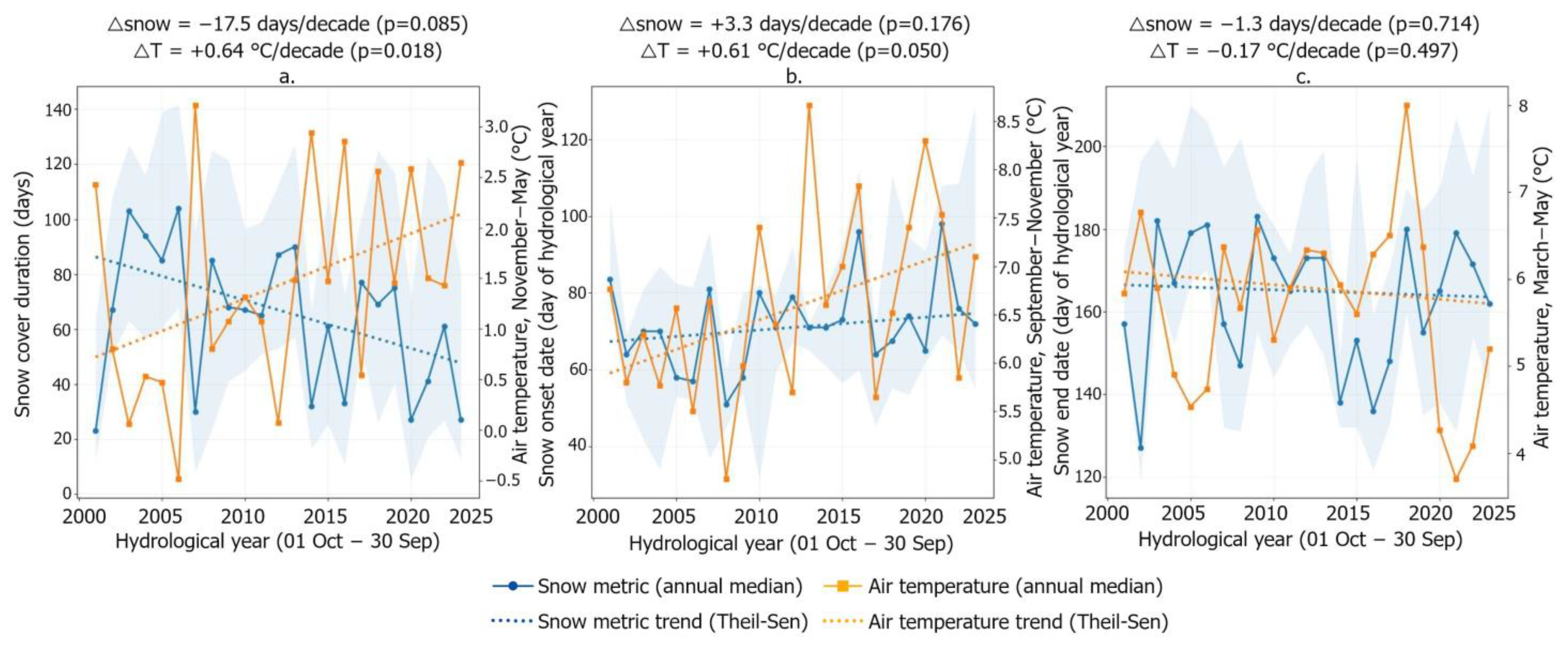

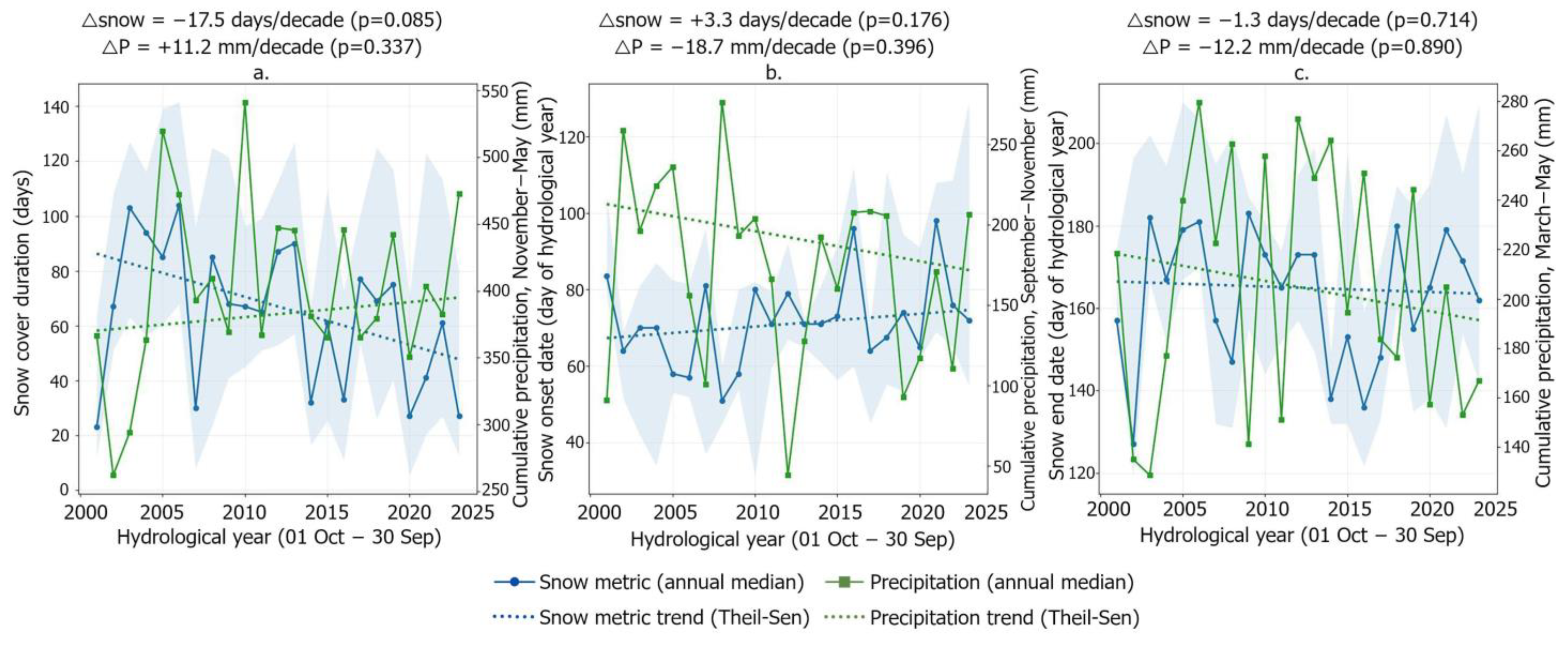

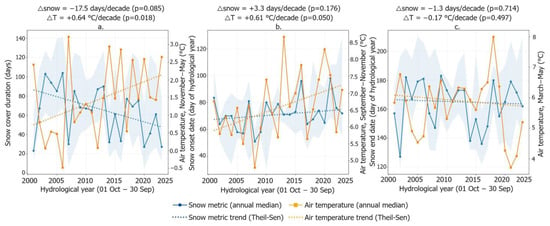

Across 2000–2023, seasonal air temperature emerges as the most consistent climatic covariate of regional snow-phenology variability, whereas precipitation exhibits weaker and less coherent associations. At the regional (station–median) scale, cold-season (November–May) air temperature increased by +0.64 °C decade−1 (Spearman p = 0.018) accompanied by a decline in snow cover duration (ΔSCD = −17.5 days decade−1; p = 0.085) (Figure 15). Although the SCD trend is marginal at p < 0.05, the statistically significant warming and the coherent co-variability support temperature as a primary driver of reduced seasonal snow persistence at the domain scale.

Figure 15.

Regional (station–median) snow phenology metrics (SCD, SOD, SED; blue) plotted with corresponding seasonal air temperature medians (orange) for 2000–2023, showing interannual variability and Theil–Sen trend lines for each series (shaded band denotes snow-metric variability).

For snow onset, early-season conditions show the expected relationship: September–November temperature increases by +0.61 °C decade−1 (p = 0.050) while SOD shifts later by +3.3 days decade−1 (p = 0.176) (Figure 15). In contrast, snow end timing exhibits a weaker association at the regional–median scale: March–May temperature shows no significant trend (ΔT = −0.17 °C decade−1; p = 0.497), and SED changes are small (ΔSED = −1.3 days decade−1; p = 0.714) (Figure 15), indicating that melt timing is less tightly captured by a single regional spring-temperature series.

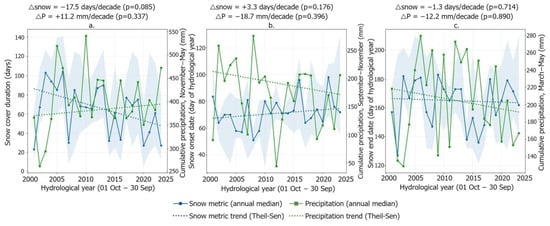

The precipitation signal is comparatively ambiguous. Seasonal precipitation trends are not significant in any of the three windows (November–May: +11.2 mm decade−1, p = 0.337; September–November: −18.7 mm decade−1, p = 0.396; March–May: −12.2 mm decade−1, p = 0.890), and their co-evolution with snow metrics is weak (Figure 16). Year–median scatterplots further reinforce this pattern, showing no detectable association with SCD (p = 0.941), weak relationship with SED (p = 0.600), and only a modest signal for SOD (p = 0.016) (Figure S2). By contrast, analogous year–median temperature relationships are consistently stronger (SCD: p = 1.1 × 10−4; SOD: p = 0.010; SED: p = 0.205) (Figure S1).

Figure 16.

Regional (station–median) snow phenology metrics (SCD, SOD, SED; blue) plotted with corresponding seasonal precipitation medians (green) for 2000–2023, showing interannual variability and Theil–Sen trend lines for each series (shaded band denotes snow-metric variability).

E-OBS maps provide spatial context, showing domain-wide warming during November–May, but spatially mixed precipitation trends over the same period (Figures S3 and S4). Taken together, these results indicate that interannual snow variability in this dataset is primarily temperature-limited than precipitation-limited at the regional scale, particularly for snow duration and onset.

4.4. Comparison with Previous Studies

Results from the Romanian Carpathians closely mirror patterns reported across mountain regions worldwide, where snow seasons are shortening, melt-out is advancing, and interannual variability is increasing under warming. In the European Alps, ref. [24] reported SCD decreases of ~5 days decade−1 below 2000 m, consistent with the Carpathians, where SCD commonly drops to ~50–80 days in the 1000–1500 m belt and decreases sharply toward lower elevations. Similar elevation controls are widely documented; studies from the Himalaya and Karakoram [25] emphasize strong altitudinal gradients in snow persistence and comparatively higher stability at high elevations, analogous to conditions in the Southern Carpathians above 2000 m where mean SCD typically exceeds ~180–200 days yr−1. Comparable low-elevation losses and high-elevation resilience have also been reported in the Western Alps [64], reflecting the same regime differentiation identified here between forested/mid-mountain belts and the alpine zone. Beyond Europe, snow-season declines primarily driven by temperature increases have been reported in northern China [19] and the Andes [65], with particularly strong sensitivity at mid elevations where snow cover is intermittent and close to the rain–snow transition. Taken together, these studies indicate that the Romanian Carpathians function as a marginal, temperature-limited mountain snow regime: the largest reductions occur in low–mid elevation belts, while the highest alpine areas show smaller changes. The observed shortening is driven primarily by earlier melt rather than uniformly delayed onset—reflecting the dominant influence of warming on seasonal snow persistence. This pattern places the Romanian Carpathians within the broader global tendency toward increasing differentiation between elevation belts, with important implications for snow–ground thermal coupling and downstream hydrological seasonality in low- to mid-elevation mountain terrain.

4.5. Limitations, Sensitivity Analyses and Future Directions

MODIS CGF daily snow products remain subject to well-known optical remote-sensing constraints in mountain terrain, including residual cloud/shadow effects, mixed pixels, and higher uncertainty during onset and melt transitions when snow is spatially patchy. The CGF procedure substantially improves temporal continuity through spatio-temporal gap filling; however, rapid snow-transition events may still be temporarily smoothed. A second limitation is the 500 m spatial resolution, which cannot resolve micro-topographic controls (wind redistribution, local shading, avalanche deposition) operating below the pixel scale. Consequently, the results are most robust for mountain-range-scale patterns, elevation and aspect contrasts, and long-term variability rather than for local snow processes.

In situ validation is further constrained by the sparse and uneven distribution of weather stations at high elevations in the Romanian Carpathians. To provide a quantitative uncertainty context, we conducted a station-based validation for 2014–2025 (Table 4; Figure 13 and Figure 14). Nevertheless, representativeness limitations—include site exposure, wind effects, and elevation gaps—prevent full characterization of snow conditions across all terrain settings.

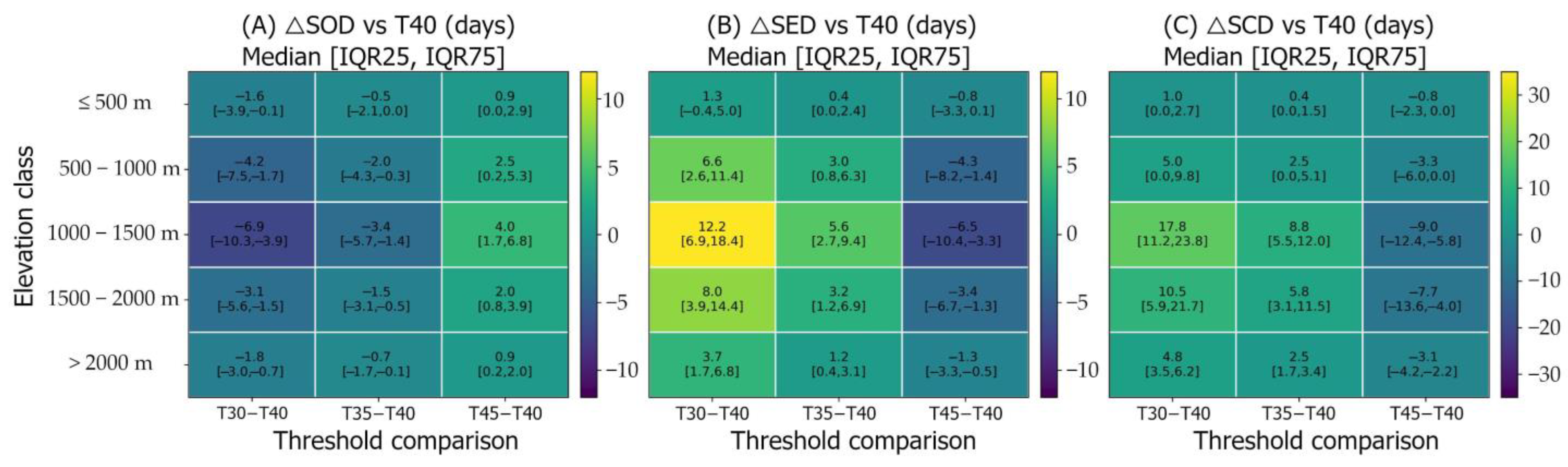

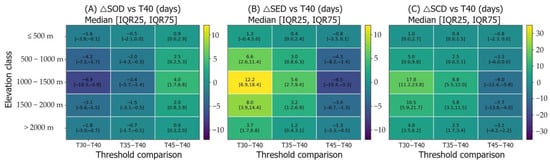

To assess the robustness of the snow/no-snow decision, the full workflow was repeated using alternative-scaled NDSI thresholds (T30, T35, T45), and deviations were evaluated relative to the T40 baseline across elevation classes. Threshold perturbations mainly affect day-level transition timing (SOD/SED) in mid-elevation belts where snow intermittency and mixed pixels are common, while SCD was comparatively less sensitive to modest changes (Figure 17). Tolerance diagnostics quantify the fraction of pixels remaining within small absolute deviations from T40 (Figure S5), and trend-robustness summaries show high correspondence of interannual variability and long-term trend signals across thresholds (Table S2a–c), supporting NDSI ≥ 40 as a consistent baseline for Carpathians-wide comparisons.

Figure 17.

Sensitivity of snow phenology metrics to the MOD10A1F-scaled NDSI threshold across elevation classes. Heatmaps show median differences (relative to the baseline T40) in (A) snow onset date (ΔSOD), (B) snow end date (ΔSED), and (C) snow cover duration (ΔSCD) for alternative thresholds T30, T35, and T45.

Figure 18 indicates that the choice of MODIS platform has a limited influence on elevation-band mean SCD, with consistently strong Terra–Aqua–composite correspondence over the overlap period (October 2003–September 2025). The largest platform-related differences occur for day-level transition timing, where agreement is lower than for SCD, particularly for SED (late-season patchiness) and for the Terra–Aqua pairing, while the same-day composite generally yields more consistent timing. These results suggest that Terra-only processing captures the dominant Carpathian-scale patterns in snow persistence and timing used in this study, while Aqua or composite processing would mainly influence a subset of pixel-level onset and melt dates during transitional periods rather than altering the regional signals.

Figure 18.

Terra–Aqua–composite sensitivity test for MODIS CGF snow metrics (October 2003–September 2025). Panels (a–c) show elevation-band annual mean SCD comparisons (Terra vs. Aqua, composite vs. Terra, composite vs. Aqua; 1:1 line shown; r and mean bias reported). Panels (d,e) show the median fraction of pixels within ±5 days agreement for SOD and SED across elevation bands for the TA, TC, and AC pairings.

Phenology dates are sensitive to how transient snow events are treated. To stabilize SOD and SED against brief autumn snowfalls, short melt interruptions, and late-season return snow, a 5-day persistence criterion was applied, ensuring that reported dates represent the seasonal snowpack rather than episodic events. Conceptually, shorter windows would increase sensitivity (earlier SOD, later SED, higher scatter), whereas longer windows would emphasize only the most persistent phases, particularly at lower elevations where patchiness is common.

At elevations ≥ 2000 m, trend inference is constrained by the small spatial footprint of this elevation belt, which limits statistical power for pixel-wise Mann–Kendall testing. In the MODIS 500 m grid, the ≥2000 m class comprises 1943 pixels (~395 km2), representing only ~0.59% of the study domain (Table S3a); thus, non-significant trends cannot be interpreted as “no change” without considering sample-size effects. To distinguish limited statistical power from true climatic stability, an area-aggregated hydrological-year series was computed for the ≥2000 m class (Table S3b), reducing pixel-level noise and enabling an effect-size interpretation via Theil–Sen slopes with 95% CIs. Aggregated slopes are close to zero for SCD, SOD, and SED (−0.303, +0.012, +0.079 days yr−1) with confidence intervals spanning zero (Table S3b), indicating small trend magnitudes at the class scale, while acknowledging that subtle changes may remain difficult to detect given the limited areal coverage.

Overall, despite well-known limitations related to cloud cover, spatial resolution, and validation constraints, the MODIS CGF dataset remains highly suitable for detecting multi-decadal changes in snow cover duration and phenology at regional scales. Future efforts integrating higher-resolution satellite imagery (e.g., Sentinel-2, PlanetScope, Landsat), targeted field measurements, and improved meteorological datasets would further reduce uncertainty and refine interpretations. Nevertheless, the present analysis already provides a robust and coherent picture of snow cover dynamics across the Romanian Carpathians.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a Carpathians-wide, spatially continuous assessment of seasonal snow cover over 2000–2025 using daily 500 m MODIS/Terra cloud-gap-filled (CGF) products. Across the Romanian Carpathians, snow cover duration (SCD), snow onset date (SOD), and snow end date (SED) show pronounced interannual variability and a clear tendency toward a shorter snow season over large areas, with the strongest changes concentrated at low and mid elevations.

Snow persistence is strongly controlled by elevation, increasing systematically with altitude and forming a distinct high-elevation regime above ~2000 m, where multiannual SCD commonly exceeds ~180–200 days. Below ~1500–1800 m, snow seasons are substantially shorter and exhibit greater interannual variability. Aspect further modulates snow persistence: north-facing slopes consistently retain the longest SCD across elevation bands, with mid-elevation differences of ~10–15 days relative to south-facing slopes, while east- and west-facing slopes show intermediate behavior.

Trend analyses indicate that the widespread decline in SCD is driven mainly by earlier snowmelt rather than a uniform delay in onset. Negative SCD trends are strongest below ~1800 m, whereas trends at ≥2000 m are weaker and often not statistically significant. Given the limited spatial extent of the ≥2000 m belt within the domain, these high-elevation results are best interpreted as indicating small trend magnitudes rather than definitive evidence of complete climatic invariance.

Methodological robustness was assessed through complementary sensitivity and validation analyses. Station-based validation for 2014–2025 shows strong agreement between MODIS-derived and observed SCD (r ≈ 0.95), with reliable performance at both elevation extremes and consistently improving day-to-day snow-occurrence agreement with altitude (median F1 rising from ~0.7 at 500–1000 m to ~0.95 above 2000 m). Threshold sensitivity tests show that modest perturbations around the baseline NDSI ≥ 40 primarily affect day-level timing metrics near the snowline, while the multi-decadal spatial patterns and trend signals remain largely unchanged. A Terra–Aqua–composite comparison over the Aqua overlap period demonstrates high SCD consistency among platforms, whereas larger differences occur for SOD/SED under transitional, spatially heterogeneous conditions; importantly, these differences do not alter the main regional and elevational conclusions derived from Terra-only analyses.

Overall, the results document a shift toward a shorter and more variable snow regime in the Romanian Carpathians, particularly below the alpine zone. By providing the first coherent, 25-year, Carpathians-wide baseline of snow persistence and timing—together with uncertainty estimates and robustness checks—this study establishes a reproducible reference for future cryospheric, ecological, hydrological, and periglacial research in a climatically distinct and comparatively under-instrumented mountain region of South-Eastern Europe.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rs18030468/s1, Table S1: Meteorological station list used for accuracy assessment; Figure S1: Scatterplot of station-year relationship between seasonal air temperature and snow-phenology metrics; Figure S2: Scatterplot of station-year relationship between seasonal precipitation and snow-phenology metrics; Figure S3: Map of air temperature trend distribution; Figure S4: Map of precipitation trend distribution; Figure S5: Robustness of snow phenology metrics to NDSI threshold tests as percentage of pixels within a tolerance window of 7 and 10 days; Table S2a: Trend robustness of SCD relative to NDSI thresholds by elevation class; Table S2b: Trend robustness of SOD relative to NDSI thresholds by elevation class; Table S2c: Trend robustness of SED relative to NDSI thresholds by elevation class; Table S3a: Spatial coverage of >2000 m band on the MODIS 500 m grid; Table S3b: Trend statistics of snow metrics in the >2000 m elevation band derived from an area-aggregated HY time series.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.I., A.O. and F.A.; methodology: A.I.; formal analysis: A.I., I.L., F.S. and A.O.; data curation: A.I.; writing—original draft preparation: A.I., I.L., F.A. and A.O.; writing—review and editing: A.I., I.L. and A.O.; visualization: A.I. and F.S.; supervision: A.O. and P.U.; project administration: A.O.; funding acquisition: A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization through CNCS–UEFISCDI, under project PN-IV-P2-2.1-TE-2023-0603, within the PNCDI IV framework, and project PN-IV-P6-6.3-SOL-2024-0248, financed through UEFISCDI under contract no. 17SOL (T17).

Data Availability Statement

All snow-related datasets used in this study are freely available through the NSIDC DAAC. The MOD10A1F product can be obtained via the NASA EarthData Search Tool at https://nsidc.org/data/mod10a1f/versions/61 (last accessed on 15 October 2025). The FABDEM dataset is openly accessible from the University of Bristol at https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/s5hqmjcdj8yo2ibzi9b4ew3sn (last accessed on 10 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCD | Snow Cover Duration |

| SOD | Snow Onset Date |

| SED | Snow End Date |

| SCA | Snow Cover Area |

| SLE | Snowline Elevation |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| FABDEM | Forests and Buildings Removed DTM |

| CGF | Cloud-Gap-Filled |

| NDSI | Normalized Difference Snow Index |

| DOHY | Day of Hydrological Year (01 Oct–30 Sep) |

References

- Déry, S.J.; Brown, R.D. Recent Northern Hemisphere Snow Cover Extent Trends and Implications for the Snow-albedo Feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 2007GL031474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanner, M.G.; Shell, K.M.; Barlage, M.; Perovich, D.K.; Tschudi, M.A. Radiative Forcing and Albedo Feedback from the Northern Hemisphere Cryosphere between 1979 and 2008. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliainen, J.; Luojus, K.; Derksen, C.; Mudryk, L.; Lemmetyinen, J.; Salminen, M.; Ikonen, J.; Takala, M.; Cohen, J.; Smolander, T.; et al. Patterns and Trends of Northern Hemisphere Snow Mass from 1980 to 2018. Nature 2020, 581, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, W.R.; Kennedy, D.; Lehner, F.; Musselman, K.N.; Rodgers, K.B.; Rosenbloom, N.; Simpson, I.R.; Yamaguchi, R. Pervasive Alterations to Snow-Dominated Ecosystem Functions under Climate Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2202393119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T. Influence of the Seasonal Snow Cover on the Ground Thermal Regime: An Overview. Rev. Geophys. 2005, 43, RG4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, Z.; Chen, S. Assessing Snow Phenology and Its Environmental Driving Factors in Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, T.P.; Adam, J.C.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Potential Impacts of a Warming Climate on Water Availability in Snow-Dominated Regions. Nature 2005, 438, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapnick, S.; Hall, A. Causes of Recent Changes in Western North American Snowpack. Clim. Dyn. 2012, 38, 1885–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Wei, W.; Li, Z.; Che, T. Increased Sensitivity of Snow Phenology to Temperature in Unstable Snow Regions since 1990. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resano-Mayor, J.; Korner-Nievergelt, F.; Vignali, S.; Horrenberger, N.; Barras, A.G.; Braunisch, V.; Pernollet, C.A.; Arlettaz, R. Snow Cover Phenology Is the Main Driver of Foraging Habitat Selection for a High-Alpine Passerine during Breeding: Implications for Species Persistence in the Face of Climate Change. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 2669–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, K.J.; Brown, R.D.; Derksen, C.; Painter, T.H. Estimating Snow-Cover Trends from Space. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraś, P.K.; Weiler, M.; Alila, Y. The Spatiotemporal Variability of Runoff Generation and Groundwater Dynamics in a Snow-Dominated Catchment. J. Hydrol. 2008, 352, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiphang, N.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bhadra, A. Assessing the Effects of Snowmelt Dynamics on Streamflow and Water Balance Components in an Eastern Himalayan River Basin Using SWAT Model. Environ. Model. Assess. 2020, 25, 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyffe, C.L.; Potter, E.; Miles, E.; Shaw, T.E.; McCarthy, M.; Orr, A.; Loarte, E.; Medina, K.; Fatichi, S.; Hellström, R.; et al. Thin and Ephemeral Snow Shapes Melt and Runoff Dynamics in the Peruvian Andes. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revuelto, J.; Alonso-González, E.; Deschamps-Berger, C.; Gutmann, E.D.; López-Moreno, J.I. Recent Advances in Snow Monitoring from Local to Global Scales. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2025, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, G.A.; Hall, D.K.; Román, M.O. Overview of NASA’s MODIS and Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Snow-Cover Earth System Data Records. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lu, N.; Yao, T. Evaluation of a Cloud-Gap-Filled MODIS Daily Snow Cover Product over the Pacific Northwest USA. J. Hydrol. 2011, 404, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascoin, S.; Hagolle, O.; Huc, M.; Jarlan, L.; Dejoux, J.-F.; Szczypta, C.; Marti, R.; Sánchez, R. A Snow Cover Climatology for the Pyrenees from MODIS Snow Products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 2337–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Han, P.; Zhang, C. Investigating Spatial-Temporal Trend of Snow Cover over the Three Provinces of Northeast China Based on a Cloud-Free MODIS Snow Cover Product. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Tang, Z.; Dong, C.; Shao, D.; Wang, X. Development and Evaluation of a Cloud-Gap-Filled MODIS Normalized Difference Snow Index Product over High Mountain Asia. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]